#Eureka Brass Band Of New Orleans

Text

Eureka Brass Band, New Orleans, LA, Photo by Ralston Crawford, c. 1960

53 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

EUREKA BRASS BAND AND SECOND LINE DANCING 1960, NEW ORLEANS

0 notes

Text

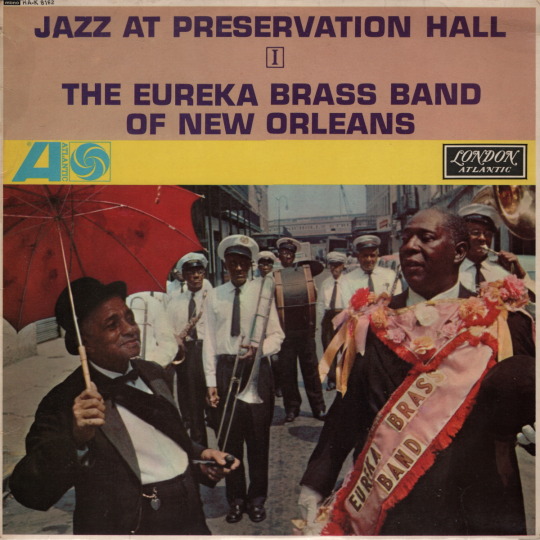

The Eureka Brass Band Of New Orleans - Jazz At Preservation Hall

Vinyl Album (1963)

45Worlds

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

William Etienne Pajaud — New Orleans Jazz - Eureka Brass Band (acrylic on canvas, 2005)

207 notes

·

View notes

Text

New Video: Preservation Hall Jazz Band's Charlie Gabriel to Release Debut Album As Bandleader, Shares Intimate, Behind-The-Scenes Visual for "I'm Confessin'"

New Video: Preservation Hall Jazz Band's Charlie Gabriel to Release Debut Album As Bandleader, Shares Intimate, Behind-The-Scenes Visual for "I'm Confessin'" @preshallband @subpop @subpoplicity

88 year-old Charlie Gabriel is a New Orleans-born and-based saxophonist, clarinetist and vocalist, who has had an incredibly lengthy music career: Gabriel’s first professional gig was back in 1943, sitting in for his father in New Orleans’ Eureka Brass Band. As a teenager, he relocated to Detroit, where he played with Lionel Hampton, whose band at the time included a young Charles Mingus. Gabriel…

View On WordPress

#Alex Hennen Payne#Aretha Franklin#Ben Jaffe#Cab Calloway#Charles Mingus#Charlie Gabriel#Charlie Gabriel 89#covers#Detroit MI#Ella Fitzgerald#Eureka Brass Band#J.C. Heard#jazz#Joshua Starkman#Lionel Hampton#music#music video#New Orleans LA#New Video#Preservation Hall Jazz Band#Sub Pop Records#Tony Bennett#video#Video Review#Video Review: Charlie Gabriel I&039;m Confessin&039;

0 notes

Text

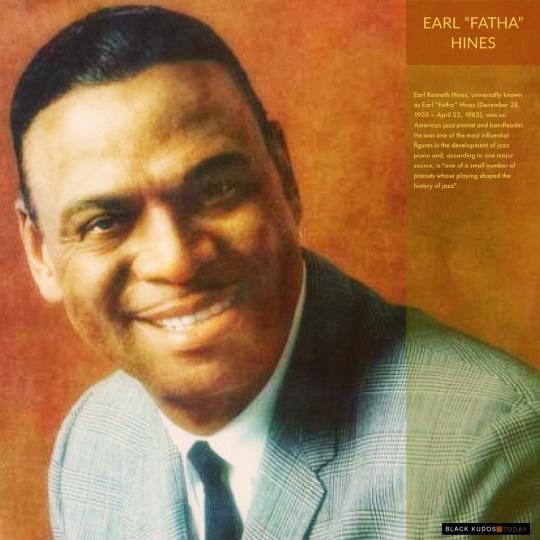

Earl “Fatha” Hines

Earl Kenneth Hines (December 28, 1903 – April 22, 1983), was an American jazz pianist and bandleader. He was one of the most influential figures in the development of jazz piano and, according to one major source, is "one of a small number of pianists whose playing shaped the history of jazz".

The trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie (a member of Hines's big band, along with Charlie Parker) wrote, "The piano is the basis of modern harmony. This little guy came out of Chicago, Earl Hines. He changed the style of the piano. You can find the roots of Bud Powell, Herbie Hancock, all the guys who came after that. If it hadn't been for Earl Hines blazing the path for the next generation to come, it's no telling where or how they would be playing now. There were individual variations but the style of ... the modern piano came from Earl Hines."

The pianist Lennie Tristano said, "Earl Hines is the only one of us capable of creating real jazz and real swing when playing all alone." Horace Silver said, "He has a completely unique style. No one can get that sound, no other pianist". Erroll Garner said, "When you talk about greatness, you talk about Art Tatum and Earl Hines".

Count Basie said that Hines was "the greatest piano player in the world".

Biography

Early life

Hines was born in Duquesne, Pennsylvania, 12 miles from the center of Pittsburgh, in 1903. His father, Joseph Hines, played cornet and was the leader of the Eureka Brass Band in Pittsburgh, and his stepmother was a church organist. Hines intended to follow his father on cornet, but "blowing" hurt him behind the ears, whereas the piano did not. The young Hines took lessons in playing classical piano. By the age of eleven he was playing the organ in his Baptist church. He had a "good ear and a good memory" and could replay songs after hearing them in theaters and park "concerts": "I'd be playing songs from these shows months before the song copies came out. That astonished a lot of people and they'd ask where I heard these numbers and I'd tell them at the theatre where my parents had taken me." Later, Hines said that he was playing piano around Pittsburgh "before the word 'jazz' was even invented".

Early career

With his father's approval, Hines left home at the age of 17 to take a job playing piano with Lois Deppe and Hhis Symphonian Serenaders in the Liederhaus, a Pittsburgh nightclub. He got his board, two meals a day, and $15 a week. Deppe, a well-known baritone concert artist who sang both classical and popular songs, also used the young Hines as his concert accompanist and took him on his concert trips to New York. In 1921 Hines and Deppe became the first African Americans to perform on radio. Hines's first recordings were accompanying Deppe – four sides recorded for Gennett Records in 1923, still in the very early days of sound recording. Only two of these were issued, one of which was a Hines composition, "Congaine", "a keen snappy foxtrot", which also featured a solo by Hines. He entered the studio again with Deppe a month later to record spirituals and popular songs, including "Sometimes I Feel Like a Motherless Child" and "For the Last Time Call Me Sweetheart".

In 1925, after much family debate, Hines moved to Chicago, Illinois, then the world's jazz capital, the home of Jelly Roll Morton and King Oliver. Hines started in Elite No. 2 Club but soon joined Carroll Dickerson's band, with whom he also toured on the Pantages Theatre Circuit to Los Angeles and back.

Hines met Louis Armstrong in the poolroom of the Black Musicians' Union, local 208, on State and 39th in Chicago . Hines was 21, Armstrong 24. They played the union's piano together. Armstrong was astounded by Hines's avant-garde "trumpet-style" piano playing, often using dazzlingly fast octaves so that on none-too-perfect upright pianos (and with no amplification) "they could hear me out front". Richard Cook wrote in Jazz Encyclopedia that

[Hines's] most dramatic departure from what other pianists were then playing was his approach to the underlying pulse: he would charge against the metre of the piece being played, accent off-beats, introduce sudden stops and brief silences. In other hands this might sound clumsy or all over the place but Hines could keep his bearings with uncanny resilience.

Armstrong and Hines became good friends and shared a car. Armstrong joined Hines in Carroll Dickerson's band at the Sunset Cafe. In 1927, this became Armstrong's band under the musical direction of Hines. Later that year, Armstrong revamped his Okeh Records recording-only band, Louis Armstrong's Hot Five, and hired Hines as the pianist, replacing his wife, Lil Hardin Armstrong, on the instrument.

Armstrong and Hines then recorded what are often regarded as some of the most important jazz records ever made.

... with Earl Hines arriving on piano, Armstrong was already approaching the stature of a concerto soloist, a role he would play more or less throughout the next decade, which makes these final small-group sessions something like a reluctant farewell to jazz's first golden age. Since Hines is also magnificent on these discs (and their insouciant exuberance is a marvel on the duet showstopper "Weather Bird") the results seem like eavesdropping on great men speaking almost quietly among themselves. There is nothing in jazz finer or more moving than the playing on "West End Blues", "Tight Like This", "Beau Koo Jack" and "Muggles".

The Sunset Cafe closed in 1927. Hines, Armstrong and the drummer Zutty Singleton agreed that they would become the "Unholy Three" – they would "stick together and not play for anyone unless the three of us were hired". But as Louis Armstrong and His Stompers (with Hines as musical director and the premises rented in Hines's name), they ran into difficulties trying to establish their own venue, the Warwick Hall Club. Hines went briefly to New York and returned to find that Armstrong and Singleton had rejoined the rival Dickerson band at the new Savoy Ballroom in his absence, leaving Hines feeling "warm". When Armstrong and Singleton later asked him to join them with Dickerson at the Savoy Ballroom, Hines said, "No, you guys left me in the rain and broke the little corporation we had".

Hines joined the clarinetist Jimmie Noone at the Apex, an after-hours speakeasy, playing from midnight to 6 a.m., seven nights a week. In 1928, he recorded 14 sides with Noone and again with Armstrong (for a total of 38 sides with Armstrong). His first piano solos were recorded late that year: eight for QRS Records in New York and then seven for Okeh Records in Chicago, all except two his own compositions.

Hines moved in with Kathryn Perry (with whom he had recorded "Sadie Green the Vamp of New Orleans"). Hines said of her, "She'd been at The Sunset too, in a dance act. She was a very charming, pretty girl. She had a good voice and played the violin. I had been divorced and she became my common-law wife. We lived in a big apartment and her parents stayed with us". Perry recorded several times with Hines, including "Body & Soul" in 1935. They stayed together until 1940, when Hines "divorced" her to marry Ann Jones Reed, but that marriage was soon "indefinitely postponed".

Hines married Janie Moses in 1947. They had two daughters, Janear (born 1950) and Tosca. Both daughters died before he did, Tosca in 1976 and Janear in 1981. Janie divorced him on June 14, 1979.

Chicago years

On December 28, 1928 (his 25th birthday and six weeks before the Saint Valentine's Day massacre), the always-immaculate Hines opened at Chicago's Grand Terrace Cafe leading his own big band, the pinnacle of jazz ambition at the time. "All America was dancing", Hines said, and for the next 12 years and through the worst of the Great Depression and Prohibition, Hines's band was the orchestra at the Grand Terrace. The Hines Orchestra – or "Organization", as Hines preferred it – had up to 28 musicians and did three shows a night at the Grand Terrace, four shows every Saturday and sometimes Sundays. According to Stanley Dance, "Earl Hines and The Grand Terrace were to Chicago what Duke Ellington and The Cotton Club were to New York – but fierier."

The Grand Terrace was controlled by the gangster Al Capone, so Hines became Capone's "Mr Piano Man". The Grand Terrace upright piano was soon replaced by a white $3,000 Bechstein grand. Talking about those days Hines later said:

... Al [Capone] came in there one night and called the whole band and show together and said, "Now we want to let you know our position. We just want you people just to attend to your own business. We'll give you all the Protection in the world but we want you to be like the 3 monkeys: you hear nothing and you see nothing and you say nothing". And that's what we did. And I used to hear many of the things that they were going to do but I never did tell anyone. Sometimes the Police used to come in ... looking for a fall guy and say, "Earl what were they talking about?" ... but I said, "I don't know - no, you're not going to pin that on me," because they had a habit of putting the pictures of different people that would bring information in the newspaper and the next day you would find them out there in the lake somewhere swimming around with some chains attached to their feet if you know what I mean.

From the Grand Terrace, Hines and his band broadcast on "open mikes" over many years, sometimes seven nights a week, coast-to-coast across America – Chicago being well placed to deal with live broadcasting across time zones in the United States. The Hines band became the most broadcast band in America. Among the listeners were a young Nat "King" Cole and Jay McShann in Kansas City, who said his "real education came from Earl Hines. When 'Fatha' went off the air, I went to bed." Hines's most significant "student" was Art Tatum.

The Hines band usually comprised 15- to 20 musicians on stage, occasionally up to 28. Among the band's many members were Wallace Bishop, Alvin Burroughs, Scoops Carry, Oliver Coleman, Bob Crowder, Thomas Crump, George Dixon, Julian Draper, Streamline Ewing, Ed Fant, Milton Fletcher, Walter Fuller, Dizzy Gillespie, Leroy Harris, Woogy Harris, Darnell Howard, Cecil Irwin, Harry 'Pee Wee' Jackson, Warren Jefferson, Budd Johnson, Jimmy Mundy, Ray Nance, Charlie Parker, Willie Randall, Omer Simeon, Cliff Smalls, Leon Washington, Freddie Webster, Quinn Wilson and Trummy Young.

Occasionally, Hines allowed another pianist sit in for him, the better to allow him to conduct the whole "Organization". Jess Stacy was one, Nat "King" Cole and Teddy Wilson were others, but Cliff Smalls was his favorite).

Each summer, Hines toured with his whole band for three months, including through the South – the first black big band to do so. He explained, "[when] we traveled by train through the South, they would send a porter back to our car to let us know when the dining room was cleared, and then we would all go in together. We couldn't eat when we wanted to. We had to eat when they were ready for us."

In Duke Ellington's America, Harvey G Cohen writes:

In 1931, Earl Hines and his Orchestra "were the first big Negro band to travel extensively through the South". Hines referred to it as an "invasion" rather than a "tour". Between a bomb exploding under their bandstage in Alabama (" ...we didn't none of us get hurt but we didn't play so well after that either") and numerous threatening encounters with the Police, the experience proved so harrowing that Hines in the 1960s recalled that, "You could call us the first Freedom Riders". For the most part, any contact with whites, even fans, was viewed as dangerous. Finding places to eat or stay overnight entailed a constant struggle. The only non-musical 'victory' that Hines claimed was winning the respect of a clothing-store owner who initially treated Hines with derision until it became clear that Hines planned to spend $85 on shirts, "which changed his whole attitude".

The birth of bebop

Hines provided the saxophonist Charlie Parker with his big break, until Parker was fired for his "time-keeping" – by which Hines meant his inability to show up on time, despite Parker's resorting to sleeping under the band stage in his attempts to be punctual. The Grand Terrace Cafe had closed suddenly in December 1940; its manager, the cigar-puffing Ed Fox, disappeared. The 37-year-old Hines, always famously good to work for, took his band on the road full-time for the next eight years, resisting renewed offers from Benny Goodman to join his band as piano player.

Several members of Hines's band were drafted into the armed forces in World War II – a major problem. Six were drafted in 1943 alone. As a result, on August 19, 1943, Hines had to cancel the rest of his Southern tour. He went to New York and hired a "draft-proof" 12-piece all-woman group, which lasted two months. Next, Hines expanded it into a 28-piece band (17 men, 11 women), including strings and French horn. Despite these wartime difficulties, Hines took his bands on tour from coast to coast. and was still able to take time out from his own band to front the Duke Ellington Orchestra in 1944 when Ellington fell ill.

It was during this time (and especially during the recording ban during the 1942–44 musicians' strike ) that late-night jam sessions with members of Hines's band's lay the seeds for the emerging new style in jazz, bebop. Ellington later said that "the seeds of bop were in Earl Hines's piano style". Charlie Parker's biographer Ross Russell wrote:

... The Earl Hines Orchestra of 1942 had been infiltrated by the jazz revolutionaries. Each section had its cell of insurgents. The band's sonority bristled with flatted fifths, off triplets and other material of the new sound scheme. Fellow bandleaders of a more conservative bent warned Hines that he had recruited much too well and was sitting on a powder keg.

As early as 1940, saxophone player and arranger Budd Johnson had "re-written the book" for the Hines' band in a more modern style. Johnson and Billy Eckstine, Hines vocalist between 1939 and 1943, have been credited with helping to bring modern players into the Hines band in the transition between swing and bebop. Apart from Parker and Gillespie, other Hines 'modernists' included Gene Ammons, Gail Brockman, Scoops Carry, Goon Gardner, Wardell Gray, Bennie Green, Benny Harris, Harry 'Pee-Wee' Jackson, Shorty McConnell, Cliff Smalls, Shadow Wilson and Sarah Vaughan, who replaced Eckstine as the band singer in 1943 and stayed for a year.

Dizzy Gillespie, in the Hines band at the time, said:

... People talk about the Hines band being 'the incubator of bop' and the leading exponents of that music ended up in the Hines band. But people also have the erroneous impression that the music was new. It was not. The music evolved from what went before. It was the same basic music. The difference was in how you got from here to here to here ... naturally each age has got its own shit.

The links to bebop remained close. Parker's discographer, among others, has argued that "Yardbird Suite", which Parker recorded with Miles Davis in March 1946, was in fact based on Hines' "Rosetta", which nightly served as the Hines band theme-tune.

Dizzy Gillespie described the Hines band, saying, "We had a beautiful, beautiful band with Earl Hines. He's a master and you learn a lot from him, self-discipline and organization."

In July 1946, Hines received serious head injuries in a car crash near Houston which, despite an operation, affected his eyesight for the rest of his life. Back on the road again four months later, he continued to lead his big band for two more years. In 1947, Hines bought the biggest nightclub in Chicago, The El Grotto, but it soon foundered with Hines losing $30,000 ($364,659 today). The big-band era was over – Hines had had his for 20 years.

Rediscovery

In early 1948, Hines joined up again with Armstrong in the "Louis Armstrong and His All-Stars" 'small-band'. It was not without its strains for Hines. A year later, Armstrong became the first jazz musician to appear on the cover of Time magazine (on February 21, 1949). Armstrong was by then on his way to becoming an American icon, leaving Hines to feel he was being used only as a sideman in comparison to his old friend. Armstrong said of the difficulties, mainly over billing, "Hines and his ego, ego, ego ...", but after three years and to Armstrong's annoyance, Hines left the All Stars in 1951.

Next, back as leader again, Hines took his own small combos around the United States. He started with a markedly more modern lineup than the aging All Stars: Bennie Green, Art Blakey, Tommy Potter, and Etta Jones. In 1954, he toured his then seven-piece group nationwide with the Harlem Globetrotters, but, at the start of the jazz-lean 1960s and old enough to retire, Hines settled "home" in Oakland, California, with his wife and two young daughters, opened a tobacconist's, and came close to giving up the profession.

Then, in 1964, thanks to Stanley Dance, his determined friend and unofficial manager, Hines was "suddenly rediscovered" following a series of recitals at the Little Theatre in New York, which Dance had cajoled him into. They were the first piano recitals Hines had ever given; they caused a sensation. "What is there left to hear after you've heard Earl Hines?", asked John Wilson of the New York Times . Hines then won the 1966 International Critics Poll for Down Beat magazine's Hall of Fame. Down Beat also elected him the world's "No. 1 Jazz Pianist" in 1966 (and did so again five more times). Jazz Journal awarded his LPs of the year first and second in its overall poll and first, second and third in its piano category. Jazz voted him "Jazzman of the Year" and picked him for its number 1 and number 2 places in the category Piano Recordings. Hines was invited to appear on TV shows hosted by Johnny Carson and Mike Douglas.

From then until his death twenty years later, Hines recorded endlessly both solo and with contemporaries like Cat Anderson, Harold Ashby, Barney Bigard, Lawrence Brown, Dave Brubeck (they recorded duets in 1975), Jaki Byard (duets in 1972), Benny Carter, Buck Clayton, Cozy Cole, Wallace Davenport, Eddie "Lockjaw" Davis, Vic Dickenson, Roy Eldridge, Duke Ellington (duets in 1966), Ella Fitzgerald, Panama Francis, Bud Freeman, Stan Getz, Dizzy Gillespie, Paul Gonsalves, Stephane Grappelli, Sonny Greer, Lionel Hampton, Coleman Hawkins, Johnny Hodges, Peanuts Hucko, Helen Humes, Budd Johnson, Jonah Jones, Max Kaminsky, Gene Krupa, Ellis Larkins, Shelly Manne, Marian McPartland (duets in 1970), Gerry Mulligan, Ray Nance, Oscar Peterson (duets in 1968), Russell Procope, Pee Wee Russell, Jimmy Rushing, Stuff Smith, Rex Stewart, Maxine Sullivan, Buddy Tate, Jack Teagarden, Clark Terry, Sarah Vaughan, Joe Venuti, Earle Warren, Ben Webster, Teddy Wilson (duets in 1965 and 1970), Jimmy Witherspoon, Jimmy Woode and Lester Young. Possibly more surprising were Alvin Batiste, Tony Bennett, Art Blakey, Teresa Brewer, Barbara Dane, Richard Davis, Elvin Jones, Etta Jones, the Ink Spots, Peggy Lee, Helen Merrill, Charles Mingus, Oscar Pettiford, Vi Redd, Betty Roché, Caterina Valente, Dinah Washington, and Ry Cooder (on the song "Ditty Wah Ditty").

But the most highly regarded recordings of this period are his solo performances, "a whole orchestra by himself". Whitney Balliett wrote of his solo recordings and performances of this time:

Hines will be sixty-seven this year and his style has become involuted, rococo, and subtle to the point of elusiveness. It unfolds in orchestral layers and it demands intense listening. Despite the sheer mass of notes he now uses, his playing is never fatty. Hines may go along like this in a medium tempo blues. He will play the first two choruses softly and out of tempo, unreeling placid chords that safely hold the kernel of the melody. By the third chorus, he will have slid into a steady but implied beat and raised his volume. Then, using steady tenths in his left hand, he will stamp out a whole chorus of right-hand chords in between beats. He will vault into the upper register in the next chorus and wind through irregularly placed notes, while his left hand plays descending, on-the-beat, chords that pass through a forest of harmonic changes. (There are so many push-me, pull-you contrasts going on in such a chorus that it is impossible to grasp it one time through.) In the next chorus—bang!—up goes the volume again and Hines breaks into a crazy-legged double-time-and-a-half run that may make several sweeps up and down the keyboard and that are punctuated by offbeat single notes in the left hand. Then he will throw in several fast descending two-fingered glissandos, go abruptly into an arrhythmic swirl of chords and short, broken, runs and, as abruptly as he began it all, ease into an interlude of relaxed chords and poling single notes. But these choruses, which may be followed by eight or ten more before Hines has finished what he has to say, are irresistible in other ways. Each is a complete creation in itself, and yet each is lashed tightly to the next.

Solo tributes to Armstrong, Hoagy Carmichael, Ellington, George Gershwin and Cole Porter were all put on record in the 1970s, sometimes on the 1904 12-legged Steinway given to him in 1969 by Scott Newhall, the managing editor of the San Francisco Chronicle. In 1974, when he was in his seventies, Hines recorded sixteen LPs. "A spate of solo recording meant that, in his old age, Hines was being comprehensively documented at last, and he rose to the challenge with consistent inspirational force". From his 1964 "comeback" until his death, Hines recorded over 100 LPs all over the world. Within the industry, he became legendary for going into a studio and coming out an hour and a half later having recorded an unplanned solo LP. Retakes were almost unheard of except when Hines wanted to try a tune again in some other wat, often completely different.

From 1964 on, Hines often toured Europe, especially France. He toured South America in 1968. He performed in Asia, Australia, Japan and, in 1966, the Soviet Union, in tours funded by the U.S. State Department. During his six-week tour of the Soviet Union, in which he performed 35 concerts, the 10,000-seat Kiev Sports Palace was sold out. As a result, the Kremlin cancelled his Moscow and Leningrad concerts as being "too culturally dangerous".

Final years

Arguably still playing as well as he ever had, Hines displayed individualistic quirks (including grunts) in these performances. He sometimes sang as he played, especially his own "They Didn't Believe I Could Do It ... Neither Did I". In 1975, Hines was the subject of an hour-long television documentary film made by ATV (for Britain's commercial ITV channel), out-of-hours at the Blues Alley nightclub in Washington, DC. The International Herald Tribune described it as "the greatest jazz film ever made". In the film, Hines said, "The way I like to play is that ... I'm an explorer, if I might use that expression, I'm looking for something all the time ... almost like I'm trying to talk." He played solo at Duke Ellington's funeral, played solo twice at the White House, for the President of France and for the Pope. Of this acclaim, Hines said, "Usually they give people credit when they're dead. I got my flowers while I was living".

Hines's last show took place in San Francisco a few days before he died in Oakland. As he had wished, his Steinway was auctioned for the benefit of gifted low-income music students, still bearing its silver plaque:

presented by jazz lovers from all over the world. this piano is the only one of its kind in the world and expresses the great genius of a man who has never played a melancholy note in his lifetime on a planet that has often succumbed to despair.

Hines was buried in Evergreen Cemetery in Oakland, California.

Style

The Oxford Companion to Jazz describes Hines as "the most important pianist in the transition from stride to swing" and continues:

As he matured through the 1920s, he simplified the stride "orchestral piano", eventually arriving at a prototypical swing style. The right hand no longer developed syncopated patterns around pivot notes (as in ragtime) or between-the-hands figuration (as in stride) but instead focused on a more directed melodic line, often doubled at the octave with phrase-ending tremolos. This line was called the "trumpet" right hand because of its markedly hornlike character but in fact the general trend toward a more linear style can be traced back through stride and Jelly Roll Morton to late ragtime from 1915 to 1920.

Hines himself described meeting Armstrong:

Louis looked at me so peculiar. So I said, "Am I making the wrong chords?" And he said, "No, but your style is like mine". So I said, "Well, I wanted to play trumpet but it used to hurt me behind my ears so I played on the piano what I wanted to play on the trumpet". And he said, "No, no, that's my style, that's what I like."

Hines continued:

... I was curious and wanted to know what the chords were made of. I would begin to play like the other instruments. But in those days we didn't have amplification, so the singers used to use megaphones and they didn't have grand-pianos for us to use at the time – it was an upright. So when they gave me a solo, playing single fingers like I was doing, in those great big halls they could hardly hear me. So I had to think of something so I could cut through the big-band. So I started to use what they call 'trumpet-style' – which was octaves. Then they could hear me out front and that's what changed the style of piano playing at that particular time.

In their book Jazz (2009), Gary Giddins and Scott DeVeaux wrote of Hines's style of the time:

To make [himself] audible, [Hines] developed an ability to improvise in tremolos (the speedy alternation of two or more notes, creating a pianistic version of the brass man's vibrato) and octaves or tenths: instead of hitting one note at a time with his right hand, he hit two and with vibrantly percussive force – his reach was so large that jealous competitors spread the ludicrous rumor that he had had the webbing between his fingers surgically removed.

Pianist Teddy Wilson wrote of Hines's style:

Hines was both a great soloist and a great rhythm player. He has a beautiful powerful rhythmic approach to the keyboard and his rhythms are more eccentric than those of Art Tatum or Fats Waller. When I say eccentric, I mean getting away from straight 4/4 rhythm. He would play a lot of what we now call 'accent on the and beat'. ... It was a subtle use of syncopation, playing on the in-between beats or what I might call and beats: one-and-two-and-three-and-four-and. The and between "one-two-three-four" is implied, When counted in music, the and becomes what are called eighth notes. So you get eight notes to a bar instead of four, although they're spaced out in the time of four. Hines would come in on those and beats with the most eccentric patterns that propelled the rhythm forward with such tremendous force that people felt an irresistible urge to dance or tap their feet or otherwise react physically to the rhythm of the music. ... Hines is very intricate in his rhythm patterns: very unusual and original and there is really nobody like him. That makes him a giant of originality. He could produce improvised piano solos which could cut through to perhaps 2,000 dancing people just like a trumpet or a saxophone could.

Oliver Jackson was Hines's frequent drummer (as well as a drummer for Oscar Peterson, Benny Goodman, Lionel Hampton, Duke Ellington, Teddy Wilson and many others):

Jackson says that Earl Hines and Erroll Garner (whose approach to playing piano, he says, came from Hines) were the two musicians he found exceptionally difficult to accompany. Why? “They could play in like two or three different tempos at one time … The left hand would be in one meter and the right hand would be in another meter and then you have to watch their pedal technique because they would hit the sustaining pedal and notes are ringing here and that’s one tempo going on when he puts the sustaining pedal on, and then this hand is moving, his left hand is moving, maybe playing tenths, and this hand is playing like quarter-note triplets or sixteenth notes. So you got this whole conglomeration of all these different tempos going on”.

Of Hines's later style, The Biographical Encyclopedia of Jazz says of Hines' 1965 style:

[Hines] uses his left hand sometimes for accents and figures that would only come from a full trumpet section. Sometimes he will play chords that would have been written and played by five saxophones in harmony. But he is always the virtuoso pianist with his arpeggios, his percussive attack and his fantastic ability to modulate from one song to another as if they were all one song and he just created all those melodies during his own improvisation.

Later still, then in his seventies and after a host of recent solo recordings, Hines himself said:

I'm an explorer if I might use that expression. I'm looking for something all the time. And oft-times I get lost. And people that are around me a lot know that when they see me smiling, they know I'm lost and I'm trying to get back. But it makes it much more interesting because then you do things that surprise yourself. And after you hear the recording, it makes you a little bit happy too because you say, "Oh, I didn't know I could do THAT!

Selected discography

Hines' first-ever recording was, apparently, made on October 3, 1923 at Richmond, Indiana, when he was aged 19. Records commercially available as new, as of February 2016, are shown��emboldened in the lists below: many more usually available second-hand on e-bay

The 1930s, classic jazz and the swing era:

Louis Armstrong & Earl Hines: inc. "Weatherbird", "Muggles", "Tight Like This", "West End Blues": Columbia 1928: reissued many times inc. as The Smithsonian Collection MLP 2012

Jimmie Noone & Earl Hines: "At the Apex Club": Decca Volume 1 1928: reissued 1967 : Decca Jazz Heritage Series

Earl Hines Solo: 14 of his own compositions: QRS & OKeh: 1928/9: reissued many times (see below)

Earl Hines Collection: Piano Solos 1928-40: OKeh/Brunswick/Bluebird: Collectors Classics

That's a Plenty, Quadromania series 1928-1947 Membran, four CDs, 2006, an easily available collection

Deep Forest, ca. 1932-1933: Hep

'Swingin' Down, 1932-1934: Hep

Harlem Lament, 1933-1934, 1937-1938: Columbia

Earl Hines - South Side Swing 1934-1935: Decca

Earl Hines - The Grand Terrace Band: RCA Victor Vintage Series

[Besides the piano solos Hines recorded for QRS (1928) and OKeh (1928), in 1929 Hines signed with Victor and recorded a number of sides in 1929. In 1932, he signed with Brunswick and recorded with them through mid-1934 when he signed with Decca. He recorded 3 sessions for Decca in 1934 and early 1935. He did not record again until February, 1937 when he signed with Vocalion, for whom he recorded 4 sessions through March 1938. After another gap, he signed with Victor's Bluebird label in July 1939 and recorded prolifically right up the recording ban in mid-1942]

Swing to bebop transition years, 1939-1945:

(Big bands were particularly affected by the 1942-1944 American Federation of Musicians recording ban which also severely curtailed the recording of early bebop)

The Indispensable Earl Hines: Vols 1, 2, 1939-1940, Jazz Tribune/BMG

The Indispensable Earl Hines: Vols 3, 4, 1939-1942, 1945, Jazz Tribune/BMG

Earl Hines & The Duke's Men: (with Ellington side-men) (1st 1944): reissued Delmark 1994

Piano man: Earl Hines, his piano and his orchestra: 1939-1942, RCA Bluebird

The Indispensable Earl Hines: Vols. 5, 6, 1944, 1964, 1966, Jazz Tribune/BMG

Earl Fatha Hines and His Orchestra: 1945-1951, Limelight 15 766

Classics, 1947-1949 (includes Eddie South) Classics

After 1948 - and therefore after Big Band era:

Louis Armstrong All Stars: Live in Zurich 18 October 1949: Montreux Jazz Label

Louis Armstrong & The All Stars: Decca 1950 & 1951: reissued

Earl Hines: Paris One Night Stand: Verve/Emarcy France 1957

The Real Earl Hines: (1st "Rediscovery" concert at Little Theatre, NY, 1964) Focus & Collectibles Jazz Classics: reissued

Earl Hines: The Legendary Little Theatre Concert (2nd "Rediscovery" concert): Muse 1964

Earl Hines: Blues in Thirds: solo: Black Lion 1965

Earl Hines: '65 Solo - The Definitive Black & Blue Sessions: Black & Blue 1965

Earl Hines: Fatha's Hands - Americans Swinging in Paris EMI 1965

Earl Hines: Hines' Tune: (live in France with Ben Webster, Don Byas, Roy Eldridge, Stuff Smith, Jimmy Woode & Kenny Clarke): Wotre Music/Esoldun 1965: reissued

Once Upon a Time with Ellington side-men: Verve 1966

Stride Right with Johnny Hodges: Verve 1966

Jazz from a Swinging Era (with All-Star group in Paris): Fontana 1967

Earl Hines & Jimmy Rushing: Blues & Things 1967

Swing's Our Thing with Johnny Hodges: Verve 1967

Earl Hines: At Home: solo (on his own Steinway): Delmark 1969

Earl Hines: My Tribute to Louis: solo: Audiophile 1971 (recorded two weeks after Armstrong's death)

Earl Hines Plays Duke Ellington (New World, 1971-1975 [1988]) reissue of Master Jazz LPs

Earl Hines Plays Duke Ellington Volume Two (New World, 1971-1974 [1997]) reissue of Master Jazz LPs

Earl Hines: Hines plays Hines: The Australian Sessions: solo: Swaggie 1972

Duet!: (with Jaki Byard), Verve/MPS 1972

Earl Hines: Tour de Force & Tour de Force Encore: solo: Black Lion 1972

Earl Hines: Live at the New School: solo: Chiarascuro 1973

Earl Hines: A Monday Date: reissues of Hines' 15 1928/1929 QRS & OKEH solo recordings: Milestone 1973

Earl Hines: The Quintessential Recording Session: solo: Chiaroscuro 1973 (remakes of his eight 1928 solo QRS piano recordings)

Earl Hines: The Quintessential Continued: solo: Chiaroscuro 1973 (remakes of his seven 1928/9 solo OKEH piano recordings)

Earl Hines Plays Cole Porter (New World, 1974 [1996])

West Side Story (Black Lion 1974)

Hines '74 (Black & Blue, 1974)

The Dirty Old Men (Black & Blue, 1974) with Budd Johnson

Earl Hines at Sundown (Black & Blue, 1974)

Earl Hines/Stephane Grappelli duets, The Giants: Black Lion 1974

Earl Hines/Joe Venuti duets: Hot Sonatas: Chiaroscuro 1975

Earl 'Fatha' Hines: The Father of Modern Jazz Piano (five LPs boxed): three LPs solo (on Schiedmeyer grand) and two LPs with Budd Johnson, Bill Pemberton, Oliver Jackson: MF Productions 1977

Earl Hines: In New Orleans: solo: Chiarascuro 1977

An Evening With Earl Hines: with Tiny Grimes, Hank Young, Bert Dahlander and Marva Josie: Disques Vogue VDJ-534 1977

Earl 'Fatha' Hines plays Hits he Missed: (inc Monk, Zawinul, Silver): Direct to Disc M & K RealTime 1978

(It would seem that Hines' last-ever recording was on December 29, 1981.)

On anthologies:

The Complete Master Jazz Piano Series: 13 Hines solo numbers: Mosaic MD4 140 (with Jay McShann, Teddy Wilson, Cliff Smalls, etc.) 1969-1972

Les Musiques de Matisse & Picasso: included Louis Armstrong & Earl Hines: West End Blues: Naive 2002

As sideman:

With Benny Carter: Swingin' the '20s: Contemporary 1958

With Johnny Hodges: 3 Shades of Blue: Flying Dutchman 1970

Wikipedia

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Albert & Donald Ayler: The Nat Hentoff DownBeat Interview

This is a fascinating piece from DownBeat in 1966 by Nat Hentoff interviewing Albert and Don Ayler. Their music stood apart from the rest of the “avant garde” movement of the time. They sounded like no one in musical language and influence. I didn’t really come to understand or feel their music until I discovered the pure New Orleans music of groups like the Eureka Brass Band from whence such emotive collective improvisation began.

-Michael Cuscuna

Read the article…

Follow: Mosaic Records Facebook Tumblr Twitter

21 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Death in Haiti: Funeral Brass Bands & Sounds from Port Au Prince (Discrepant, March 2018) Recorded in Port au Prince by sound artist Félix Blume in early December 2016, Death in Haiti plunges the listener into a world of pain, loss and solemn celebration as each funeral comprises of its own live jazz band as well as a plethora of characters like the joker (le blaguer) who cracks jokes and tales about the recently deceased. A beautiful document of a thriving tradition, a counterpart or updated version of those famous Dirge Jazz records such as the New Orleans’ Eureka Brass Band on Folkways. Here are some of the musicians holding their copies, courtesy of @felix____blume. Only an handful of copies left in out bandcamp and website. #sundayservice #discrepant #haiti #felixblume #vynil (at Port-au-Prince, Haiti) https://www.instagram.com/p/CPygBCqrNQK/?utm_medium=tumblr

0 notes

Text

VHS #370

Food Finds - New Orleans & Cajun Cooking on the Food Channel… Wayne Baquet on gumbo, New Orleans Over Night co, crawfish boil, berl a little water, Crescent City Farmer’s Market, making file’ by hand, The Gumbo Shop, roux, Savoie’s roux.

***

Dancing to New Orleans20032 hrs w/ commercialsBravoaudio has static

https://www.amazon.com/Dancing-Orleans-Dirty-Dozen-Brass/dp/B0000AQS40

Buckwheat Zydeco, Michael Doucet, Gregory Davis (Dirty Dozen BB),My Feet Can’t Fail Me Now, Jazz Fest sights, Louisiana Hayride, the song Jambalaya is based on Grand Texas, Jerry Lee Lewis, You Win Again, Great Balls of Fire, raymond miles at Jazz fest! (gospel), Can’t Nobody Do Me Like Jesus (Ray-Ban stage) William Ferris, blues, Big Jack Johnson, white slide blues guy - John Campbell in a theater, Leadbelly style, texas banjo style, Gatemouth Brown at Jazz fest - Born In Louisiana, tells of his start and his music, teach kids the right way of life, Joe Krown, fiddle tune hoedown, cajun & zydeco, Francis pavy artist, clifton chenier, cj chenier at jazz fest, happy feet music, played sax with his father, froittoir maker, LA is unique, buckwheat zydeco at his farm, on stage at night, on stage at Jazz fest, hard to stop (https://youtu.be/OHlHt7Djcg0) this clip? 2007, talks about his start, didn’t like zydeco then, played with Clifton Chenier, Junior Martin accordion maker (melodeon), beausoleil at Jazz Fest la danse de la vie!, have fun and be who you are, pic w/ Canray, courir de mardi gras, mardi gras in iota, a cappella women, ann savoy, music is the glue that holds the culture together, 12 year-old amanda shaw – little black dog at home, new orleans, zulu social aid and pleasure club, lionel ferbos at 91, palm court jazz band (trad jazz) shake it break it hang it on the wall, tells of his history, Maison Bourbon, brass bands, Louis Armstrong, dirty dozen brass band, gregiry davis, at jazz fest in tent, on main stage, my feet can’t fail me now, inspired by dancers in new orleans, monday night at the glass house, buck dancing, shake something, acura stage, meet de boys on de battle front, mardi gras indians/neville brothers, costumes, bo dollis, Monk Boudreaux, uptown vs downtown indian costumes, neville brothers on stage at jazz fest, voodoo – neville brothers at jazz fest, congo square, charles gillam – wood carver, i learned my lesson the hard way - bleeding, 50s music, allan toussaint on stage, irma thomas – ruler of my heart! (dew drop inn revisted, jazz fest 1992), professor longhair, neville brothers on stage at jazz fest - tipitina (have seen this jazz fest before – same clothes)

***

Mardi Gras Revealed Travel Channel(duplicate – see #369, fewer “and another secret is”) same as Best of the Big Easy/The Secrets of Mardi Gras

***

black

***

Best Of The Big EasyTravel Channel1 hr 2/24

Same as on #369.

***

black

***

5) All On A Mardi Gras Day - black carnival in NO1 hr, WYES2/24, WLIWaudio static at times

https://www.amazon.com/Mardi-Gras-Chief-Tootie-Montana/dp/0615206271

Go To The Mardi Gras - Professor Longhair, mardi Gras indians, baby dolls, skeleton and bone gangs, “Goat" Carson, Indians, Carnival in Parisian style, Kalamu u Salam, Haitian refugees, code noir, congo square, dances in rings/circles, blacks appropriated the holiday and made it their own, indians followed the blacks, Handa Wanda - Bo Dollis & Wild Magnolias, response to rise of hate when Union troops after Emancipation Proclamation left started Mardi Gras Indians and jazz, Buffalo Bill Wild West Show made an impression?, Tootie Montana, bead work is both african and indian, uptown indian style, Tuba Fats, New Suit - Wild Magnolias, Donald Harrison Jr, the weekend before Mardi Gras day - no rest, Monk Boudreaux, spy boy, flag boy, wild man lowest position in the tribe, warrior culture, drink gunpowder and gin, leads to violence, knives and hatchets, rivalry of uptown and downtown, change from violence to beauty, being pretty, my big chief got a golden crown, turn of the century, parading krewes, mock king to rule the day, flambeaux, zulu, from The Tramps, arrive by tugboat, blackened their faces, parody of Mardi Gras, big shot, baby dolls, no schedule, stayed as long as they wanted if they were having a good time, Louis Armstrong as king of zulu, perdido st, gorilla, mocking Rex, politically incorrect, black bourgeoisie embraced it after civll rights, witch doctor was a white guy, rained badly that day, cocoanuts, Street Parade - Earl King, baby dolls started in 1912 by prostitutes, Uncle Lionel, men dressed as baby dolls, cross dressing is as old as Mardi Gras, the dirty dozen, music on pots and pans, claiborne av, skull and bone gangs, Mr Brown - Bob marley, bloody meaty bones, grown people were afraid of them, bruce barnes as a park ranger, Hey Pocky A-Way - Meters, second line, african rhythms from west africa, bamboula rhythm, can’t have mardi gras without the music, Rex can, we can’t, mardi gras indians, indian red, eureka brass band, gallier hall, mardi gras mambo -the hawketts, al johnson - carnival time, our carnival was on clairborne, I-10 impacted clairborne, memphis blues - louis james string band, Big Al Carson - All On A Mardi Gras Day

***

Mardi Gras 2005: 45 min

Pontchatrain parade excerptsfull screen from computer~1/2 hrJeff and red haired girl

jerky video

1/29/05Sparta & Pegasusblond frat guy and brunette woman

1/30/05a little bourbon st interviews

yellow bird woman, flash big (censored), again, Sara, (Then intro to Saturday 1/29/05 bourbon st interviews which gets cut off.)

0 notes

Text

Earl "Fatha" Hines

Earl Kenneth Hines, also known as Earl "Fatha" Hines (December 28, 1903 – April 22, 1983), was an American jazz pianist and bandleader. He was one of the most influential figures in the development of jazz piano and, according to one source, "one of a small number of pianists whose playing shaped the history of jazz".

The trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie (a member of Hines's big band, along with Charlie Parker) wrote, "The piano is the basis of modern harmony. This little guy came out of Chicago, Earl Hines. He changed the style of the piano. You can find the roots of Bud Powell, Herbie Hancock, all the guys who came after that. If it hadn't been for Earl Hines blazing the path for the next generation to come, it's no telling where or how they would be playing now. There were individual variations but the style of ... the modern piano came from Earl Hines."

The pianist Lennie Tristano said, "Earl Hines is the only one of us capable of creating real jazz and real swing when playing all alone." Horace Silver said, "He has a completely unique style. No one can get that sound, no other pianist". Erroll Garner said, "When you talk about greatness, you talk about Art Tatum and Earl Hines".

Count Basie said that Hines was "the greatest piano player in the world".

Biography

Early life

Earl Hines was born in Duquesne, Pennsylvania, 12 miles from the center of Pittsburgh, in 1903. His father, Joseph Hines, played cornet and was the leader of the Eureka Brass Band in Pittsburgh, and his stepmother was a church organist. Hines intended to follow his father on cornet, but "blowing" hurt him behind the ears, whereas the piano did not. The young Hines took lessons in playing classical piano. By the age of eleven he was playing the organ in his Baptist church. He had a "good ear and a good memory" and could replay songs after hearing them in theaters and park concerts: "I'd be playing songs from these shows months before the song copies came out. That astonished a lot of people and they'd ask where I heard these numbers and I'd tell them at the theatre where my parents had taken me." Later, Hines said that he was playing piano around Pittsburgh "before the word 'jazz' was even invented".

Early career

With his father's approval, Hines left home at the age of 17 to take a job playing piano with Lois Deppe and His Symphonian Serenaders in the Liederhaus, a Pittsburgh nightclub. He got his board, two meals a day, and $15 a week. Deppe, a well-known baritone concert artist who sang both classical and popular songs, also used the young Hines as his concert accompanist and took him on his concert trips to New York. In 1921 Hines and Deppe became the first African Americans to perform on radio. Hines's first recordings were accompanying Deppe – four sides recorded for Gennett Records in 1923, still in the very early days of sound recording. Only two of these were issued, one of which was a Hines composition, "Congaine", "a keen snappy foxtrot", which also featured a solo by Hines. He entered the studio again with Deppe a month later to record spirituals and popular songs, including "Sometimes I Feel Like a Motherless Child" and "For the Last Time Call Me Sweetheart".

In 1925, after much family debate, Hines moved to Chicago, Illinois, then the world's jazz capital, the home of Jelly Roll Morton and King Oliver. Hines started in Elite No. 2 Club but soon joined Carroll Dickerson's band, with whom he also toured on the Pantages Theatre Circuit to Los Angeles and back.

Hines met Louis Armstrong in the poolroom of the Black Musicians' Union, local 208, on State and 39th in Chicago. Hines was 21, Armstrong 24. They played the union's piano together. Armstrong was astounded by Hines's avant-garde "trumpet-style" piano playing, often using dazzlingly fast octaves so that on none-too-perfect upright pianos (and with no amplification) "they could hear me out front". Richard Cook wrote in Jazz Encyclopedia that

[Hines's] most dramatic departure from what other pianists were then playing was his approach to the underlying pulse: he would charge against the metre of the piece being played, accent off-beats, introduce sudden stops and brief silences. In other hands this might sound clumsy or all over the place but Hines could keep his bearings with uncanny resilience.

Armstrong and Hines became good friends and shared a car. Armstrong joined Hines in Carroll Dickerson's band at the Sunset Cafe. In 1927, this became Armstrong's band under the musical direction of Hines. Later that year, Armstrong revamped his Okeh Records recording-only band, Louis Armstrong and His Hot Five, and hired Hines as the pianist, replacing his wife, Lil Hardin Armstrong, on the instrument.

Armstrong and Hines then recorded what are often regarded as some of the most important jazz records ever made.

... with Earl Hines arriving on piano, Armstrong was already approaching the stature of a concerto soloist, a role he would play more or less throughout the next decade, which makes these final small-group sessions something like a reluctant farewell to jazz's first golden age. Since Hines is also magnificent on these discs (and their insouciant exuberance is a marvel on the duet showstopper "Weather Bird") the results seem like eavesdropping on great men speaking almost quietly among themselves. There is nothing in jazz finer or more moving than the playing on "West End Blues", "Tight Like This", "Beau Koo Jack" and "Muggles".

The Sunset Cafe closed in 1927. Hines, Armstrong and the drummer Zutty Singleton agreed that they would become the "Unholy Three" – they would "stick together and not play for anyone unless the three of us were hired". But as Louis Armstrong and His Stompers (with Hines as musical director and the premises rented in Hines's name), they ran into difficulties trying to establish their own venue, the Warwick Hall Club. Hines went briefly to New York and returned to find that Armstrong and Singleton had rejoined the rival Dickerson band at the new Savoy Ballroom in his absence, leaving Hines feeling "warm". When Armstrong and Singleton later asked him to join them with Dickerson at the Savoy Ballroom, Hines said, "No, you guys left me in the rain and broke the little corporation we had".

Hines joined the clarinetist Jimmie Noone at the Apex, an after-hours speakeasy, playing from midnight to 6 a.m., seven nights a week. In 1928, he recorded 14 sides with Noone and again with Armstrong (for a total of 38 sides with Armstrong). His first piano solos were recorded late that year: eight for QRS Records in New York and then seven for Okeh Records in Chicago, all except two his own compositions.

Hines moved in with Kathryn Perry (with whom he had recorded "Sadie Green the Vamp of New Orleans"). Hines said of her, "She'd been at The Sunset too, in a dance act. She was a very charming, pretty girl. She had a good voice and played the violin. I had been divorced and she became my common-law wife. We lived in a big apartment and her parents stayed with us". Perry recorded several times with Hines, including "Body & Soul" in 1935. They stayed together until 1940, when Hines "divorced" her to marry Ann Jones Reed, but that marriage was soon "indefinitely postponed".

Hines married singer 'Lady of Song' Janie Moses in 1947. They had two daughters, Janear (born 1950) and Tosca. Both daughters died before he did, Tosca in 1976 and Janear in 1981. Janie divorced him on June 14, 1979.

Chicago years

On December 28, 1928 (his 25th birthday and six weeks before the Saint Valentine's Day Massacre), the always-immaculate Hines opened at Chicago's Grand Terrace Cafe leading his own big band, the pinnacle of jazz ambition at the time. "All America was dancing", Hines said, and for the next 12 years and through the worst of the Great Depression and Prohibition, Hines's band was the orchestra at the Grand Terrace. The Hines Orchestra – or "Organization", as Hines preferred it – had up to 28 musicians and did three shows a night at the Grand Terrace, four shows every Saturday and sometimes Sundays. According to Stanley Dance, "Earl Hines and The Grand Terrace were to Chicago what Duke Ellington and The Cotton Club were to New York – but fierier."

The Grand Terrace was controlled by the gangster Al Capone, so Hines became Capone's "Mr Piano Man". The Grand Terrace upright piano was soon replaced by a white $3,000 Bechstein grand. Talking about those days Hines later said:

... Al [Capone] came in there one night and called the whole band and show together and said, "Now we want to let you know our position. We just want you people just to attend to your own business. We'll give you all the Protection in the world but we want you to be like the 3 monkeys: you hear nothing and you see nothing and you say nothing". And that's what we did. And I used to hear many of the things that they were going to do but I never did tell anyone. Sometimes the Police used to come in ... looking for a fall guy and say, "Earl what were they talking about?" ... but I said, "I don't know - no, you're not going to pin that on me," because they had a habit of putting the pictures of different people that would bring information in the newspaper and the next day you would find them out there in the lake somewhere swimming around with some chains attached to their feet if you know what I mean.

From the Grand Terrace, Hines and his band broadcast on "open mikes" over many years, sometimes seven nights a week, coast-to-coast across America – Chicago being well placed to deal with live broadcasting across time zones in the United States. The Hines band became the most broadcast band in America. Among the listeners were a young Nat King Cole and Jay McShann in Kansas City, who said his "real education came from Earl Hines. When 'Fatha' went off the air, I went to bed." Hines's most significant "student" was Art Tatum.

The Hines band usually comprised 15-20 musicians on stage, occasionally up to 28. Among the band's many members were Wallace Bishop, Alvin Burroughs, Scoops Carry, Oliver Coleman, Bob Crowder, Thomas Crump, George Dixon, Julian Draper, Streamline Ewing, Ed Fant, Milton Fletcher, Walter Fuller, Dizzy Gillespie, Leroy Harris, Woogy Harris, Darnell Howard, Cecil Irwin, Harry 'Pee Wee' Jackson, Warren Jefferson, Budd Johnson, Jimmy Mundy, Ray Nance, Charlie Parker, Willie Randall, Omer Simeon, Cliff Smalls, Leon Washington, Freddie Webster, Quinn Wilson and Trummy Young.

Occasionally, Hines allowed another pianist sit in for him, the better to allow him to conduct the whole "Organization". Jess Stacy was one, Nat "King" Cole and Teddy Wilson were others, but Cliff Smalls was his favorite.

Each summer, Hines toured with his whole band for three months, including through the South – the first black big band to do so. He explained, "[when] we traveled by train through the South, they would send a porter back to our car to let us know when the dining room was cleared, and then we would all go in together. We couldn't eat when we wanted to. We had to eat when they were ready for us."

In Duke Ellington's America, Harvey G Cohen writes:

In 1931, Earl Hines and his Orchestra "were the first big Negro band to travel extensively through the South". Hines referred to it as an "invasion" rather than a "tour". Between a bomb exploding under their bandstage in Alabama (" ...we didn't none of us get hurt but we didn't play so well after that either") and numerous threatening encounters with the Police, the experience proved so harrowing that Hines in the 1960s recalled that, "You could call us the first Freedom Riders". For the most part, any contact with whites, even fans, was viewed as dangerous. Finding places to eat or stay overnight entailed a constant struggle. The only non-musical 'victory' that Hines claimed was winning the respect of a clothing-store owner who initially treated Hines with derision until it became clear that Hines planned to spend $85 on shirts, "which changed his whole attitude".

The birth of bebop

In 1942 Hines provided the saxophonist Charlie Parker with his big break, until Parker was fired for his "time-keeping" – by which Hines meant his inability to show up on time, despite Parker's resorting to sleeping under the band stage in his attempts to be punctual. Dizzie Gillespie joined the same year.

The Grand Terrace Cafe had closed suddenly in December 1940; its manager, the cigar-puffing Ed Fox, disappeared. The 37-year-old Hines, always famously good to work for, took his band on the road full-time for the next eight years, resisting renewed offers from Benny Goodman to join his band as piano player.

Several members of Hines's band were drafted into the armed forces in World War II – a major problem. Six were drafted in 1943 alone. As a result, on August 19, 1943, Hines had to cancel the rest of his Southern tour. He went to New York and hired a "draft-proof" 12-piece all-woman group, which lasted two months. Next, Hines expanded it into a 28-piece band (17 men, 11 women), including strings and French horn. Despite these wartime difficulties, Hines took his bands on tour from coast to coast but was still able to take time out from his own band to front the Duke Ellington Orchestra in 1944 when Ellington fell ill.

It was during this time (and especially during the recording ban during the 1942–44 musicians' strike ) that late-night jam sessions with members of Hines's band's sowed the seeds for the emerging new style in jazz, bebop. Ellington later said that "the seeds of bop were in Earl Hines's piano style". Charlie Parker's biographer Ross Russell wrote:

... The Earl Hines Orchestra of 1942 had been infiltrated by the jazz revolutionaries. Each section had its cell of insurgents. The band's sonority bristled with flatted fifths, off triplets and other material of the new sound scheme. Fellow bandleaders of a more conservative bent warned Hines that he had recruited much too well and was sitting on a powder keg.

As early as 1940, saxophone player and arranger Budd Johnson had "re-written the book" for the Hines' band in a more modern style. Johnson and Billy Eckstine, Hines vocalist between 1939 and 1943, have been credited with helping to bring modern players into the Hines band in the transition between swing and bebop. Apart from Parker and Gillespie, other Hines 'modernists' included Gene Ammons, Gail Brockman, Scoops Carry, Goon Gardner, Wardell Gray, Bennie Green, Benny Harris, Harry 'Pee-Wee' Jackson, Shorty McConnell, Cliff Smalls, Shadow Wilson and Sarah Vaughan, who replaced Eckstine as the band singer in 1943 and stayed for a year.

Dizzy Gillespie said of the music the band evolved:

... People talk about the Hines band being 'the incubator of bop' and the leading exponents of that music ended up in the Hines band. But people also have the erroneous impression that the music was new. It was not. The music evolved from what went before. It was the same basic music. The difference was in how you got from here to here to here ... naturally each age has got its own shit.

The links to bebop remained close. Parker's discographer, among others, has argued that "Yardbird Suite", which Parker recorded with Miles Davis in March 1946, was in fact based on Hines' "Rosetta", which nightly served as the Hines band theme-tune.

Dizzy Gillespie described the Hines band, saying, "We had a beautiful, beautiful band with Earl Hines. He's a master and you learn a lot from him, self-discipline and organization."

In July 1946, Hines suffered serious head injuries in a car crash near Houston which, despite an operation, affected his eyesight for the rest of his life. Back on the road again four months later, he continued to lead his big band for two more years. In 1947, Hines bought the biggest nightclub in Chicago, The El Grotto, but it soon foundered with Hines losing $30,000 ($393,328 today). The big-band era was over – Hines' bands had been at the top for 20 years.

Rediscovery

In early 1948, Hines joined up again with Armstrong in the "Louis Armstrong and His All-Stars" "small-band". It was not without its strains for Hines. A year later, Armstrong became the first jazz musician to appear on the cover of Timemagazine (on February 21, 1949). Armstrong was by then on his way to becoming an American icon, leaving Hines to feel he was being used only as a sideman in comparison to his old friend. Armstrong said of the difficulties, mainly over billing, "Hines and his ego, ego, ego ...", but after three years and to Armstrong's annoyance, Hines left the All Stars in 1951.

Next, back as leader again, Hines took his own small combos around the United States. He started with a markedly more modern lineup than the aging All Stars: Bennie Green, Art Blakey, Tommy Potter, and Etta Jones. In 1954, he toured his then seven-piece group nationwide with the Harlem Globetrotters. In 1958 he broadcast on the American Forces Network but by the start of the jazz-lean 1960s and old enough to retire, Hines settled "home" in Oakland, California, with his wife and two young daughters, opened a tobacconist's, and came close to giving up the profession.

Then, in 1964, thanks to Stanley Dance, his determined friend and unofficial manager, Hines was "suddenly rediscovered" following a series of recitals at the Little Theatre in New York, which Dance had cajoled him into. They were the first piano recitals Hines had ever given; they caused a sensation. "What is there left to hear after you've heard Earl Hines?", asked John Wilson of The New York Times. Hines then won the 1966 International Critics Poll for Down Beat magazine's Hall of Fame. Down Beat also elected him the world's "No. 1 Jazz Pianist" in 1966 (and did so again five more times). Jazz Journal awarded his LPs of the year first and second in its overall poll and first, second and third in its piano category. Jazzvoted him "Jazzman of the Year" and picked him for its number 1 and number 2 places in the category Piano Recordings. Hines was invited to appear on TV shows hosted by Johnny Carson and Mike Douglas.

From then until his death twenty years later, Hines recorded endlessly, both solo and with contemporaries like Cat Anderson, Harold Ashby, Barney Bigard, Lawrence Brown, Dave Brubeck (they recorded duets in 1975), Jaki Byard (duets in 1972), Benny Carter, Buck Clayton, Cozy Cole, Wallace Davenport, Eddie "Lockjaw" Davis, Vic Dickenson, Roy Eldridge, Duke Ellington (duets in 1966), Ella Fitzgerald, Panama Francis, Bud Freeman, Stan Getz, Dizzy Gillespie, Paul Gonsalves, Stephane Grappelli, Sonny Greer, Lionel Hampton, Coleman Hawkins, Milt Hinton, Johnny Hodges, Peanuts Hucko, Helen Humes, Budd Johnson, Jonah Jones, Max Kaminsky, Gene Krupa, Ellis Larkins, Shelly Manne, Marian McPartland (duets in 1970), Gerry Mulligan, Ray Nance, Oscar Peterson (duets in 1968), Russell Procope, Pee Wee Russell, Jimmy Rushing, Stuff Smith, Rex Stewart, Maxine Sullivan, Buddy Tate, Jack Teagarden, Clark Terry, Sarah Vaughan, Joe Venuti, Earle Warren, Ben Webster, Teddy Wilson (duets in 1965 and 1970), Jimmy Witherspoon, Jimmy Woode and Lester Young. Possibly more surprising were Alvin Batiste, Tony Bennett, Art Blakey, Teresa Brewer, Barbara Dane, Richard Davis, Elvin Jones, Etta Jones, the Ink Spots, Peggy Lee, Helen Merrill, Charles Mingus, Oscar Pettiford, Vi Redd, Betty Roché, Caterina Valente, Dinah Washington, and Ry Cooder (on the song "Ditty Wah Ditty").

But the most highly regarded recordings of this period are his solo performances, "a whole orchestra by himself". Whitney Balliett wrote of his solo recordings and performances of this time:

Hines will be sixty-seven this year and his style has become involuted, rococo, and subtle to the point of elusiveness. It unfolds in orchestral layers and it demands intense listening. Despite the sheer mass of notes he now uses, his playing is never fatty. Hines may go along like this in a medium tempo blues. He will play the first two choruses softly and out of tempo, unreeling placid chords that safely hold the kernel of the melody. By the third chorus, he will have slid into a steady but implied beat and raised his volume. Then, using steady tenths in his left hand, he will stamp out a whole chorus of right-hand chords in between beats. He will vault into the upper register in the next chorus and wind through irregularly placed notes, while his left hand plays descending, on-the-beat, chords that pass through a forest of harmonic changes. (There are so many push-me, pull-you contrasts going on in such a chorus that it is impossible to grasp it one time through.) In the next chorus—bang!—up goes the volume again and Hines breaks into a crazy-legged double-time-and-a-half run that may make several sweeps up and down the keyboard and that are punctuated by offbeat single notes in the left hand. Then he will throw in several fast descending two-fingered glissandos, go abruptly into an arrhythmic swirl of chords and short, broken, runs and, as abruptly as he began it all, ease into an interlude of relaxed chords and poling single notes. But these choruses, which may be followed by eight or ten more before Hines has finished what he has to say, are irresistible in other ways. Each is a complete creation in itself, and yet each is lashed tightly to the next.

Solo tributes to Armstrong, Hoagy Carmichael, Ellington, George Gershwin and Cole Porter were all put on record in the 1970s, sometimes on the 1904 12-legged Steinway given to him in 1969 by Scott Newhall, the managing editor of the San Francisco Chronicle. In 1974, when he was in his seventies, Hines recorded sixteen LPs. "A spate of solo recording meant that, in his old age, Hines was being comprehensively documented at last, and he rose to the challenge with consistent inspirational force". From his 1964 "comeback" until his death, Hines recorded over 100 LPs all over the world. Within the industry, he became legendary for going into a studio and coming out an hour and a half later having recorded an unplanned solo LP. Retakes were almost unheard of except when Hines wanted to try a tune again in some other way, often completely different.

From 1964 on, Hines often toured Europe, especially France. He toured South America in 1968. He performed in Asia, Australia, Japan and, in 1966, the Soviet Union, in tours funded by the U.S. State Department. During his six-week tour of the Soviet Union, in which he performed 35 concerts, the 10,000-seat Kiev Sports Palace was sold out. As a result, the Kremlin cancelled his Moscow and Leningrad concerts as being "too culturally dangerous".

Final years

Arguably still playing as well as he ever had, Hines displayed individualistic quirks (including grunts) in these performances. He sometimes sang as he played, especially his own "They Didn't Believe I Could Do It ... Neither Did I". In 1975, Hines was the subject of an hour-long television documentary film made by ATV (for Britain's commercial ITV channel), out-of-hours at the Blues Alley nightclub in Washington, DC. The International Herald Tribune described it as "the greatest jazz film ever made". In the film, Hines said, "The way I like to play is that ... I'm an explorer, if I might use that expression, I'm looking for something all the time ... almost like I'm trying to talk." In 1979, Hines was inducted into the Black Filmmakers Hall of Fame. He played solo at Duke Ellington's funeral, played solo twice at the White House, for the President of France and for the Pope. Of this acclaim, Hines said, "Usually they give people credit when they're dead. I got my flowers while I was living".

Hines's last show took place in San Francisco a few days before he died in Oakland. As he had wished, his Steinway was auctioned for the benefit of gifted low-income music students, still bearing its silver plaque:

presented by jazz lovers from all over the world. this piano is the only one of its kind in the world and expresses the great genius of a man who has never played a melancholy note in his lifetime on a planet that has often succumbed to despair.

Hines was buried in Evergreen Cemetery in Oakland, California.

On June 25, 2019, The New York Times Magazine listed Earl Hines among hundreds of artists whose material was reportedly destroyed in the 2008 Universal fire.

Style

The Oxford Companion to Jazz describes Hines as "the most important pianist in the transition from stride to swing" and continues:

As he matured through the 1920s, he simplified the stride "orchestral piano", eventually arriving at a prototypical swing style. The right hand no longer developed syncopated patterns around pivot notes (as in ragtime) or between-the-hands figuration (as in stride) but instead focused on a more directed melodic line, often doubled at the octave with phrase-ending tremolos. This line was called the "trumpet" right hand because of its markedly hornlike character but in fact the general trend toward a more linear style can be traced back through stride and Jelly Roll Morton to late ragtime from 1915 to 1920.

Hines himself described meeting Armstrong:

Louis looked at me so peculiar. So I said, "Am I making the wrong chords?" And he said, "No, but your style is like mine". So I said, "Well, I wanted to play trumpet but it used to hurt me behind my ears so I played on the piano what I wanted to play on the trumpet". And he said, "No, no, that's my style, that's what I like."

Hines continued:

... I was curious and wanted to know what the chords were made of. I would begin to play like the other instruments. But in those days we didn't have amplification, so the singers used to use megaphones and they didn't have grand-pianos for us to use at the time – it was an upright. So when they gave me a solo, playing single fingers like I was doing, in those great big halls they could hardly hear me. So I had to think of something so I could cut through the big-band. So I started to use what they call 'trumpet-style' – which was octaves. Then they could hear me out front and that's what changed the style of piano playing at that particular time.

In their book Jazz (2009), Gary Giddins and Scott DeVeaux wrote of Hines's style of the time:

To make [himself] audible, [Hines] developed an ability to improvise in tremolos (the speedy alternation of two or more notes, creating a pianistic version of the brass man's vibrato) and octaves or tenths: instead of hitting one note at a time with his right hand, he hit two and with vibrantly percussive force – his reach was so large that jealous competitors spread the ludicrous rumor that he had had the webbing between his fingers surgically removed.

Pianist Teddy Wilson wrote of Hines's style:

Hines was both a great soloist and a great rhythm player. He has a beautiful powerful rhythmic approach to the keyboard and his rhythms are more eccentric than those of Art Tatum or Fats Waller. When I say eccentric, I mean getting away from straight 4/4 rhythm. He would play a lot of what we now call 'accent on the and beat'. ... It was a subtle use of syncopation, playing on the in-between beats or what I might call andbeats: one-and-two-and-three-and-four-and. The and between "one-two-three-four" is implied, When counted in music, the and becomes what are called eighth notes. So you get eight notes to a bar instead of four, although they're spaced out in the time of four. Hines would come in on those and beats with the most eccentric patterns that propelled the rhythm forward with such tremendous force that people felt an irresistible urge to dance or tap their feet or otherwise react physically to the rhythm of the music. ... Hines is very intricate in his rhythm patterns: very unusual and original and there is really nobody like him. That makes him a giant of originality. He could produce improvised piano solos which could cut through to perhaps 2,000 dancing people just like a trumpet or a saxophone could.

Oliver Jackson was Hines's frequent drummer (as well as a drummer for Oscar Peterson, Benny Goodman, Lionel Hampton, Duke Ellington, Teddy Wilson and many others):

Jackson says that Earl Hines and Erroll Garner (whose approach to playing piano, he says, came from Hines) were the two musicians he found exceptionally difficult to accompany. Why? “They could play in like two or three different tempos at one time … The left hand would be in one meter and the right hand would be in another meter and then you have to watch their pedal technique because they would hit the sustaining pedal and notes are ringing here and that’s one tempo going on when he puts the sustaining pedal on, and then this hand is moving, his left hand is moving, maybe playing tenths, and this hand is playing like quarter-note triplets or sixteenth notes. So you got this whole conglomeration of all these different tempos going on”.

Of Hines's later style, The Biographical Encyclopedia of Jazz says of Hines' 1965 style:

[Hines] uses his left hand sometimes for accents and figures that would only come from a full trumpet section. Sometimes he will play chords that would have been written and played by five saxophones in harmony. But he is always the virtuoso pianist with his arpeggios, his percussive attack and his fantastic ability to modulate from one song to another as if they were all one song and he just created all those melodies during his own improvisation.

Later still, then in his seventies and after a host of recent solo recordings, Hines himself said:

I'm an explorer if I might use that expression. I'm looking for something all the time. And oft-times I get lost. And people that are around me a lot know that when they see me smiling, they know I'm lost and I'm trying to get back. But it makes it much more interesting because then you do things that surprise yourself. And after you hear the recording, it makes you a little bit happy too because you say, "Oh, I didn't know I could do THAT!

0 notes

Text

VHS #367

Martin Scorsese - The Blues

simulcast on WBGO

https://www.pbs.org/theblues/index.html

The first 4 episodes. (#4 is partial)

1) Feel Like Going Home by Martin Scorsese1 & 1/2 hrs

You Can’t Lose What You Ain’t Never Had - Muddy Waters, Martin talks about the series, work songs, Leadbelly- Goodnight Irene, Corey Harris, Corey meets Sam Carr, Willie King, Muddy Waters at Stovall place, Son House - ain’t but one kind of blues, Dick Waterman, Taj Mahal, Spoonful, Johnny Shines, Robert Johnson - Hellhound On My Trail, Sweet Home Chicago, Keb Mo, squeeze my lemon, John Lee Hooker, african fife and drum, Bamako, Mali, Salif Keita - Ana Na Ming, Habib Koite, Sankore Mosque, Toumani Diabate, Ali Farka Touré, Otha Turner & The Rising Star Fife & Drum Band - My Babe.

performances:

Ali Farka Touré

Corey Harris

Salif Keita

Son House

Taj Mahal

John Lee Hooker

Keb' Mo'

Willie King

Interviews:

Corey Harris

Sam Carr

Toumani Diabate

Willie King

Dick Waterman

Taj Mahal

Johnny Shines

Otha Turner

Ali Farka Toure

Habib Koité

Salif Keita

Keb' Mo'

(Not in order)

1. Robert Johnson- Traveling Riverside Blues

Recorded Dallas, Texas; June 20, 1937

2. Johnny Shines- Dynaflow Blues

Recorded Chicago, Illinois; December, 1965

3. Robert Johnson- Hell Hound On My Trail

Recorded Dallas, Texas; June 20, 1937

4. Muddy Waters - Country Blues

Recorded Stovall, Mississippi; August 26-31, 1941

5. Taj Mahal - The Celebrated Walking Blues

Recorded Hollywood, California; August 18, 1967

6. Son Simms Four - Rosalie

Recorded Stovall, Mississippi; July 24, 1942

7. Son House - My Black Mama Pt. II

Recorded Grafton, Wisconson; May 28, 1930

8. Son House - Government Fleet Blues

Recorded Klack's Store, Lake Cormorant, Mississippi; August 24-31, 1941

9. Muddy Waters- Gypsy Woman

Recorded Chicago, Illinois; 1947

10. Charley Patton - High Water Everywhere Pt. I

Recorded Grafton, Wisconson; October, 1929

11. Lead Belly - CC Rider

Recorded New York, New York; January 23, 1935

12. Willie King & The Liberators - Terrorized

Recorded Aliceville, Alabama; April 19, 2003

13. Napoleon Strickland & Otha Turner - Oh Baby

Recorded 1967

14. Otha Turner & Corey Harris - Lay My Burden Down

Recorded Senatobia, Mississippi; June 9, 2001

15. Ali Farka Toure - Mali Dje

Recorded Niafunke, Mali; 1999

16. John Lee Hooker - Tupelo Blues

Recorded Detroit, Michigan; April, 1959

17. Ali Farka Toure - Amandrai

Recorded London, England; 1988

18. John Lee Hooker - Hobo Blues

Recorded Detroit, Michigan; 1949

19. Salif Keita - Ana Na Ming

Recorded Mali; August 16, 2001

20. Otha Turner & The Rising Star Fife & Drum Band - My Babe

(Willie Dixon)

Recorded St. Ann's Warehouse, Brooklyn, New York; November 9, 2001

***

credits for one of them. John The Revelator m

Corey Harris and Otha Turner - Sitting on Top Of The World

***

2) The Soul of a Man by Wim Wenders2/29/?simulcast on WBGO

You Can’t Lose What You Ain’t Never Had - Muddy Waters, Martin intro, NASA Voyager disc with blues on it, actor as Blind Willie Johnson, Marc Ribot, Skip James wins talent show, Lucinda Williams, Alvin Youngblood Hart, Bonnie Raitt, …, John Mayall, Roosevelt Sykes had a rent paying party, Skip was there, Bonnie Raitt, Steve and Ronnog Seaberg, Los Lobos, JB Lenoir, Shemekia Copeland, T Bone Burnett, Cassandra Wilson, Dick Waterman, Skip James at Newport, Cream - I’m So Glad, Garland Jeffreys, Eagle-Eye Cherry, Vernon Reid and James "Blood” Ulmer.

Skip James

Blind Willie Johnson

J. B. Lenoir

(not in order)

1. Cassandra Wilson - Vietnam Blues

(J.B. Lenoir)

2. Eagle-Eye Cherry, Vernon Reid and James "Blood" Ulmer - Down In Mississippi

(J.B. Lenoir)

3. Lucinda Williams - Hard Time Killing Floor Blues

(Nehemiah Skip James)

Lucinda Williams (guitar, vocal); , Bo Ramsey (guitar)

Recorded at St. Ann's, Brooklyn, November 9, 2001

4. Lou Reed - Look Down The Road

(Nehemiah Skip James)