#Gøhrilgabrielsen

Text

Book Review: Gøhril Gabrielsen’s Ankomst

by Dr. Sorcha Fogarty

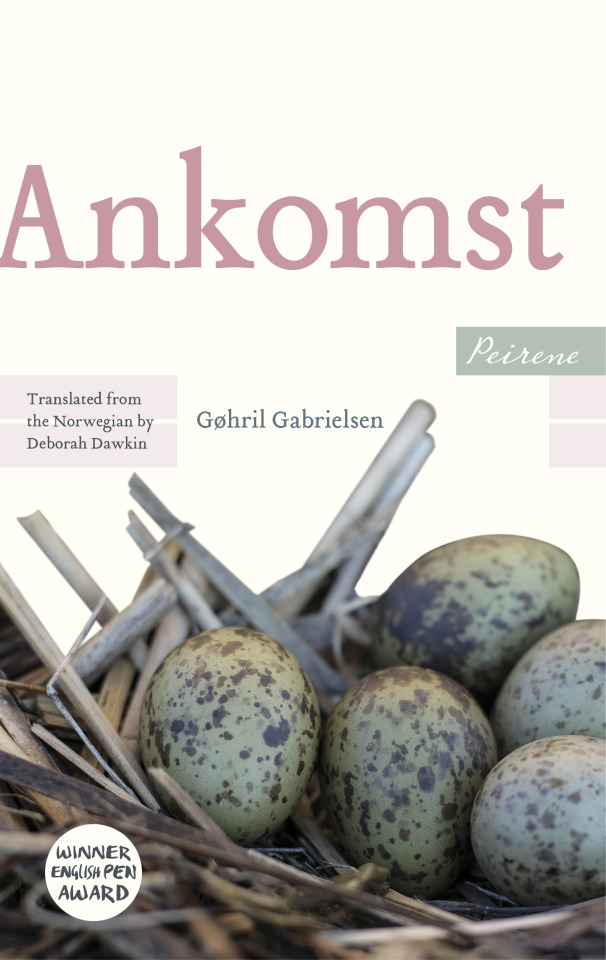

Gabrielsen’s debut novel Unevnelige hendelser (Unspeakable Events) came out in 2006 winning Aschehoug’s First Book Award. She won the Tanum Women Writer’s Prize in 2010, and the Amalie Skram Prize for her oeuvre in 2016. Published by Peirene Press as part of their aptly titled Closed Universe series of books in 2020, Ankomst is Gabrielsen’s fifth novel and was awarded the 2017 Havmann Prize for Northern Norway Literature. It also was selected as one of the winners of the English PEN’s flagship translation awards of 2020.

The first line of any novel should be a seduction, drawing the reader in, and Gabrielsen doesn’t disappoint, beginning Ankomst with “This is where the world ends”. The protagonist, who remains unnamed, is a Biologist and Environmental Scientist wintering on a remote Norwegian peninsula to collect data on the link between climate change and the decline in numbers of various species in order to complete her doctoral thesis. She has left behind her young daughter, her ex-husband, and her lover – whom she is convinced will be joining her imminently. We spend the entire 180 pages in the company of a woman whose name we do not even know, and the success of this book hinges entirely on Gabrielsen’s ability to create a fascinating protagonist out of this nameless, faceless woman.

There is a kind of cyclical rhythm to the events of the novel – in a book just 180 pages long, we have 50 chapters, and each chapter is anywhere between one and five pages long. The short chapters are like bursts of information, a kind of pseudo-diary, narrated in the first person, and this narrative technique serves to build tension and an impending sense of doom aided by the detailed descriptions of the surroundings, the relentlessly foreboding seas and skies. Throughout Ankomst, the rational is juxtaposed with the emotional, as our scientifically-minded narrator attempts to suppress her growing emotional turmoil through her daily chores and her commitment to completing her thesis. She painstakingly measures environmental conditions and takes data readings, stating “Emotions should be like that. Measurable. Predictable.” But, as we all know, they’re not. And, as the story progresses, her emotions defy such neat containment as the pressure of her isolation becomes all the more apparent. There is a sense of remoteness and drifting towards madness as she endeavours to plow on with her work while she reflects on the collapse of her personal life. Furthermore, the lover she is waiting for never seems to arrive.

The Norwegian word “ankomst” translates as “arrival/coming/entrance (the act of entering)”. However, paradoxically, the book is less about where the protagonist has come to than about what she’s running away from. Having left so much behind, she hopes she can move on with her life. Her longing for “clear and measurable phenomena” and a “language of indisputable realities, rather than dumb, undefinable feelings” gives way to a declining mental state, as she spends much of her time alone pondering a story found in a pamphlet she discovers, regarding a house that burned down 140 years ago close to the site of her hut. Using the few details given, she conjures up an elaborate story of what might have happened, imagining the life of the family and their hardship. However, this is all merely a projection of her own past, and as the story progresses we are drip fed more information about what came before the trip, and the end of her marriage to a man simply referred to as S.

The rational thinker becomes drawn towards the irrational, and the remoteness she has sought starts to feel less like a refuge and more like a threat, “And now I can hear it again, the sound of moaning [...]. Is it coming from me or the stove? Is it just the embers dying? The logs collapsing and turning to ash?” Is it her imagination or is there someone else around? We’re never really sure if this is a manifestation of her paranoia or something more. As the narrator begins to suspect that her lover is not so keen on joining her, and as the constant solitude begins to wear her down, her mind begins to play tricks on her, with occasional blackouts and suspicions of objects moving of their own accord. Is she starting to lose her mind? Or, as suggested above, more disturbingly, is she not as alone as she thinks? While the brilliant 20th century philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre famously ended his play No Exit with the line, “Hell is Other People”, and we have all experienced some sort of “social overload” at times, needing solitude in order to recharge ourselves, prolonged isolation is widely recognised as a precursor to many serious mental health problems. Like it or not, we are social animals, and fundamentally, we need other people. Limited social engagements have deleterious emotional effects including a rise in fear and paranoia and a decrease in self-esteem.

There are a lot of common horror elements in the book – the setting of The Thing, and the isolation and supernatural elements of The Shining. One critic has noted that it also has a lot in common thematically with space thrillers, like Gravity, The Martian or Moon, a comparison which Gabrielsen herself has noted – “It strikes me that fieldwork has many similarities to a stay on a space station. Like an astronaut I find myself in a desolate place, lonely and infinitely far from people, utterly dependent on technology as my sole link to the world beyond”. Ankomst is essentially a story of slow-burning dread, a tale which highlights the effects of isolation with only the primal forces of nature for company. Ultimately, this strange yet captivating work illustrates that sometimes, the things we may be trying to flee from aren’t so easy to escape, especially when most of them are in our own minds.

2 notes

·

View notes