#Hillendale Farms

Text

youtube

yet they say the impact from the fire was not predicted to raise prices, and we can all see that the egg industry is raking in record profits this year. some are reporting more than 750% increase in profits. This is gouging which is why I wonder why the egg industry is doing this in america.

heres something we bet you never realized ?

Since Emancipation, agriculture has moved its focus from one labor source to another in response to shifting currents of populism, nativism and racism. All three benefit from the exploitation of minority populations, and all three justify policies of exploitation in economic terms.

Arizona prisons partners with one of the countries largest egg farms?

youtube

these folks not only make egg products, but only cost the state $3.00 per hour in labor. America is the shithole of ethics

read this,

Farmers turn to prisons to fill labor needs

With immigration numbers low, the agriculture industry looks to another form of disenfranchised workers.

American agriculture often depends on migrant workers, like the one pictured here harvesting corn in Gilroy, California. But the anti-immigration policies of the Trump administration have farmers turning to prisoners to harvest labor-intensive crops.

Prison inmates are picking fruits and vegetables at a rate not seen since Jim Crow.

Convict leasing for agriculture – a system that allows states to sell prison labor to private farms – became infamous in the late 1800s for the brutal conditions it imposed on captive, mostly black workers.

Federal and state laws prohibited convict leasing for most of the 20th century, but the once-notorious practice is making a comeback.

Under lucrative arrangements, states are increasingly leasing prisoners to private corporations to harvest food for American consumers.

Why now?

The U.S. food system relies on cheap labor. Today, median income for farm workers is $10.66 an hour, with 33% of farm-worker households living below the poverty line.

Historically, agriculture has suppressed wages – and eschewed worker protections – by hiring from vulnerable groups, notably, undocumented migrants. By some estimates, 70% of agriculture’s 1.2 million workers are undocumented.

As current anti-immigrant policies diminish the supply of migrant workers (both documented and undocumented), farmers are not able to find the labor they need. So, in states such as Arizona, Idaho and Washington that grow labor-intensive crops like onions, apples and tomatoes, prison systems have responded by leasing convicts to growers desperate for workers.

The racist roots of convict leasing

Since Reconstruction, states have used prisoners to solve labor supply problems in industries such as road and rail construction, mining and agriculture. But convict leasing has also been a powerful weapon of white supremacy, and now, anti-immigrant sentiment.

After Emancipation, southern economies faced a crisis: how to maintain a racial caste system and a supply of surplus labor now that blacks were free.

Southern states passed vagrancy laws, Black Codes, and other legislation to selectively incarcerate freed slaves. For example, under Mississippi’s vagrancy law, all black men had to provide written proof of a job or face a $50 fine. Those who could not pay were forced to work for any white man willing to pay the fine — an amount that was deducted from the black man’s wage.

During the late 1800s, mass incarceration created an army of cheap labor that could be leased to private businesses for substantial profit. In 1886, state revenues from leasing exceeded the cost of running prisons by nearly 400%. Between 1870 and 1910, 88% of convicts leased in Georgia were black. In this Library of Congress photo from 1903, juvenile convicts are shown at work in the fields, location unknown. Library of Congress/Detroit Publishing Co.

Populist response

But cheap convict labor also suppressed wages for free whites, and by 1900, poor whites began pushing back.

In 1904, James Vardaman was elected governor of Mississippi on a platform of returning whites to work and blacks to confinement. These populist white supremacist sentiments dovetailed with national economic concerns during the Great Depression, when agricultural failures led to widespread unemployment.

In the 1930s, the Ashurst-Sumners Act and accompanying state laws prohibited convict leasing and the sale of prisoner-made goods on the open market. Inmates still worked in agriculture, but the food they produced had to be consumed by other prisoners or state workers.

By the late 1970s, with growing competition from foreign manufacturing, U.S. companies sought out domestic sources of cheap labor.

Under pressure from corporate lobbies like the American Legislative Exchange Council, Congress relaxed restrictions on convict leasing with the Justice System Improvement Act. As the manufacturing and service sectors began hiring prisoners, agriculture expanded its use of migrant workers.

Profit and exploitation

Today, convict leasing offers significant revenues for prisons.

Most wages paid to inmates are garnished by prisons to cover incarceration costs and pay victim restitution programs. In some cases, prisoners see no monetary compensation whatsoever. In 2015 and 2016, the California Prison Industry Authority made over $2 million from its food and agriculture sector.

Growers can reap significant revenues, too. Inmates are excluded from federal minimum wage protections, allowing prison systems to lease convicts at a rate below the going labor rate. In Arizona, inmates leased through Arizona Correctional Industries (ACI) receive a wage of $3-$4 per hour before deductions. Meanwhile, the state’s minimum wage for most non-incarcerated farm workers is $11/hr.

Beyond the unfairness of low wages, inadequate state and federal regulations ensure that agricultural work continues to be onerous. Laborers endure long hours, repetitive motion injuries, temperature and humidity extremes and exposure to caustic and carcinogenic chemicals.

For inmates, these circumstances are unlikely to change. U.S. courts have ruled that prisoners are prohibited from organizing for higher wages and working conditions – though strikes have occurred in recent years.

Furthermore, inmates are not legally considered employees, which means they are excluded from protection under parts of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, the Equal Pay Act, the Fair Labor Standards Act, the National Labor Relations Act and the Federal Tort Claims Act.

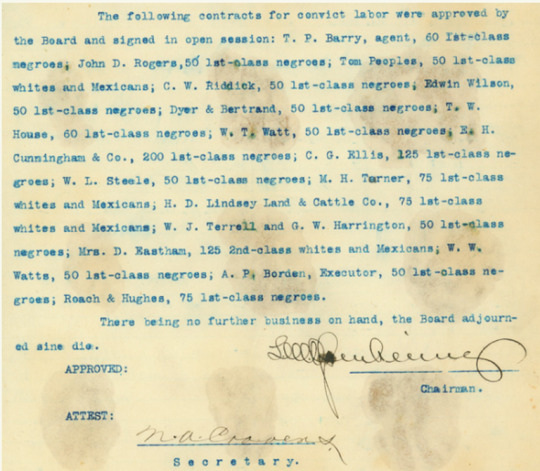

Excerpt from minutes of the regular meeting of the Texas Penitentiary Board, Nov. 12, 1903.

Whose labor is being sold?

The total number – and racial makeup – of leased inmates is difficult to calculate. Not all prison systems report on farming operations or leased labor arrangements. According to one advocacy group, at least 30,000 inmates work within the food system. But to the extent that convict leasing reflects overall inmate demographics, prison agriculture is distinctly racial.

Blacks make up 39% of inmates, but only 12% of the general population, making blacks six times more likely than whites to be incarcerated. Over the last 50 years – the same period that saw the return of convict leasing – the black incarceration rate quadrupled.

Proponents of “prison industries” argue that leasing provides rehabilitative benefits like on-the-job training for reentry. But research shows that within the prison system, whites receive better jobs than blacks, with better pay and more beneficial skills.

Whereas migrant workers often benefit home communities by returning a portion of their wages as remittances, the garnishing or nonpayment of convict wages prevents inmates from contributing to their families and home economies.

Since Emancipation, agriculture has moved its focus from one labor source to another in response to shifting currents of populism, nativism and racism. All three benefit from the exploitation of minority populations, and all three justify policies of exploitation in economic terms.

Convict leasing is the first – and now the latest – strategy.

#eggs#egg farms#chickens#prison industries#arizona#connecticut#Arizona Correctional Industries - Partnership with Hickman's Family Farms#Hillendale Farms#egg prices#egg price increases#record profits in egg business in 2023#Farmers turn to prisons to fill labor needs#Youtube

1 note

·

View note

Text

BREAKING UPDATE: Hillendale Farms in Connecticut, the largest supplier of chicken eggs "caught fire" on Saturday, leaving an estimated 100,000 hens dead.

All coincidentally during an egg shortage, move along now, nothing to see here.🤔

#pay attention#educate yourself#educate yourselves#reeducate yourself#knowledge is power#reeducate yourselves#think for yourself#think for yourselves#think about it#do your homework#do your research#do your own research#question everything#ask yourselves#ask yourself#truthful news#real news#world news#news#national news#supply chain

265 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hillendale Farms in Connecticut, the largest supplier of chicken eggs “caught fire” this weekend, leaving an estimated 100,000 hens dead

https://www.investmentwatchblog.com/hillendale-farms-in-connecticut-the-largest-supplier-of-chicken-eggs-caught-fire-this-weekend-leaving-an-estimated-100000-hens-dead/?utm_source=dlvr.it&utm_medium=tumblr

0 notes

Link

The state of Maine has refused to press charges against Hillendale, a farm using hens for their eggs, despite compelling video from The Humane Society of the United States. See the footage from HSUS here.

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

As they were in 2021, egg prices in the US were exceptionally high in November and December 2022. This was due to several major factors, and there hasn’t been much change in these factors so far in 2023. Poultry World has the latest on the many factors causing huge increases in the retail price of US eggs and looks at what’s ahead.

In November, US consumers started noticing an exceptional increase in the price of table eggs and major media outlets reported that the national average price for a dozen hit US$ 3.59, up from US$ 1.72 a year earlier.

At that point, high prices were being driven up to some extent by holiday festivities and baking demands, but most of the price increase was due to the continued upswings in feed, fuel and labour costs (i.e., inflation). In addition, supply was obviously limited due to the widespread outbreaks of highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) across the US. These outbreaks have so far resulted in over 58 million birds being culled.

The national flock is recovering, and Nathan Jervey, spokesperson at the American Egg Board (AEB) industry association, reports: “The US Department of Agriculture estimates that at the start of February, we were sitting at 303 million. We typically have 320 million laying hens at any given time”. That’s a current difference of about 9%. So although farms are getting back to normal, US egg supplies have also been negatively affected in at least 2 states due to fires.

Forsman Farms in Minnesota, an operation that sold more than 3 million eggs a day to some of the largest retailers in the US, was hit by fire in May 2022. In January 2023, Hillendale Farms, Connecticut’s largest supplier of eggs, went up in flames resulting in the death of about 100,000 hens, with cage-free mandates from California and Massachusetts also adding to the tight supply situation.

A closer look

As indicated, some of the factors causing these high egg prices in the US include rising feed, fuel and labour costs. There are also higher packaging costs and supply chain constraints. But which of these are likely to be most impactful and which could ease for any reason, going forward this year?

“As each farming operation is different and located in different parts of the country, it would be inappropriate for me to hazard a guess as to how each element factors into the cost for consumers,” explains Jervey. “Along those same lines, I can’t speak to them easing but can say that inflation is cooling, as noted by the consumer price index (CPI).”

The CPI is a measure of the average change over time in the prices paid by urban consumers for a market basket of consumer goods and services. In December, the CPI dropped by 0.1% after the seasonal adjustment, while, without seasonal adjustment, it had risen by 6.5% over the last 12 months.

AEB cannot predict the price of eggs this year, but Jervey says: “Demand has remained high, as evidenced by the retail volume of shell eggs remaining constant year-over-year.”

As to whether more HPAI outbreaks will affect prices, Jervey says, “it’s hard to say” and reiterates: “Prices reflect several factors. The good news is that our farms are recovering quickly.”

An agricultural economist’s view

Dr Jada Thompson, an agricultural economist at the University of Arkansas, has been closely following egg price developments. While she noted that egg price relief might come from egg farmers steadily replacing their lost flocks, she also observes that: “Feed, fuel and labour are all still higher than 2021 levels. Feed prices were up by about 13-23% year-over-year for corn and soybeans [in 2022]. That is a substantial part of the cost of producing an egg. These factors will continue to affect egg prices.”

However, at the same time, Thompson expects egg prices in 2023 to drop below the higher prices seen in 2021 and in November-December 2022. “I don’t think we’ll hit the 2021 lower prices with the higher feed, fuel and labour costs,” she says. “The issue is that we will likely have more HPAI outbreaks, but it seems the industry is working on pre-emptive supply planning to try to ease some of the potential supply shocks. Only time will tell how many birds will be impacted or the effect on prices this year.”

Thompson reminds us that this particular HPAI strain is troublesome because of its longevity. “If it affects the poultry industry, and specifically the layer industry, like it did last year, we would likely see shorter supplies which would drive the price up,” she explains.

“The silver lining is that with replenishment efforts working double time to try to get layers back on track, there may be hope that if the layer industry can keep a bit ahead of HPAI this year, this will limit the pricing impact,” she added.

0 notes

Text

Massive fire at Hillendale Farms in Connecticut. largest suppliers of chicken eggs

https://www.investmentwatchblog.com/massive-fire-at-hillendale-farms-in-connecticut-largest-suppliers-of-chicken-eggs/?utm_source=dlvr.it&utm_medium=tumblr

0 notes