#I AM NOT SAYING SYNCRETISM OR HERESY

Text

'fran can you stop being Like That for 5 seconds?'

Unfortunately not. I am a non-person underneath all the masks and personas and the only thing left is an empty void obsessed with depressed christian existentialists, theodicy and the existence of evil, and the nature of suffering

#the duality of fran#be normal be normal be normal#i am. so well. alas#thinking my silly little thinky thoughts#which everyone maybe hates but thats ok#m still thinking#also thinking abt how obvs the early church was like nooo Greco roman paganism bad#but also if u look at the conception of divinity and theodicy in the tragedians and philosophers (and less so in populsr religion)#u see a lot. not the same. but a lot of ideas about like. evil. the nature of the gods as both terrifying and good. both horrible& beautiful#the both/and nature. the awe inspiring in the traditional sense of the word#like obvs it's the influence of platonism and neo Platonism on the church fathers#but also ive given yall my dionysios and jesus ramble before. smthn smthn smthn human and divine#I AM NOT SAYING SYNCRETISM OR HERESY#I AM SAYING. PREFIGURING. I AM SAYING. THE HUMAN SOUL IS ALWAYS SEEKING THIS THING#I AM SAYING THE PHILOSOPHICAL DISCUSSIONS AND DIALOGUE OF THE PERIOD#anyway. im normal. im sooooo normal about the problem of evil

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Submitted via Google Form:

How do I write a world where non-earth religions (I’m creating them) are both diverse, and also common place to see people participate in multiple religions’ festivities or rituals. One, because there’s distance to actual religion and entering common lifestyle. Example like on earth plenty of non Christians are holding Christmas parties, it’s a common thing and not overtly religious. Two, or why not because of the diversity, religions simply mix together. Like on earth why not have fasting like Muslims do simply become a common lifestyle custom alongside Buddhist meditations also being common lifestyle customs. Three. Like two, but why can’t someone on earth be both Muslim and Buddhist?? Does that even make sense?

I only gave you real life religions as example only, for ease of explaining, not at all what I’ll use.

Also in this kind of world, how would you see religious tolerance? Can it honestly really be in harmony? How about the bigots? There’s still got to be some won’t there? Especially when daily lifestyles, or simply in the architecture and design throw all sorts of religion in their faces they can’t avoid unless they live under a rock.

Feral:

I’m not sure what the question is here. Should some people in your world participate in religious festivals that do not align with their beliefs? It’s certainly possible, and it depends on the religion in question. Christianity is inherently an evangelical religion; “witnessing” is the call of every Christian, so Christian religious activities tend to be geared towards welcoming non-believers with the intent on making them believers. Not to mention nearly all Christian festivals were the festivals of other religions that Christians reshaped into their own. And not to mention the commercialization of Christmas specifically has fundamentally changed how Christmas is viewed by Christians and non-Christians alike; I’ve heard it said, and am inclined to believe more or less, that even Christians in Victorian England really didn’t celebrate Christmas until Charles Dickens wrote “A Christmas Carol.” So, Christmas, for example, is of such mixed ancestry and exists in such a way as to be welcome for outsiders to “celebrate” without already believing in the underlying religion. It’s very important to keep in mind that this happens in culturally Christian regions or where Christmas has been so commercialized that people couldn’t even tell you its religious significance; and a lot of people of minority religions really fucking hate it - it’s insulting to be told that displaying a hanukiah at work is against company policy because you can’t have anything overtly religious on display when you’re surrounded by Christmas trees and listening to Christmas carols like “Oh Holy Night” piped in over the sound system. So you’ll want to keep in mind that some people will view a religious festival that’s “ubiquitously” celebrated as a dominant religion being forced on them at the expense of their own religious identity. You’ll also likely have religions that don’t proselytize and have absolutely no interest whatsoever in non-believers participating in their holy days - they’re holy! They’re meant for the people who already believe.

I’ve already briefly touched on why some religions would have a problem with non-believers crowding in on their holidays, but it’s worth repeating - not all religions are like Christianity. I’d go so far as to say that no other religions are like Christianity in this particular way. As for your examples regarding “Muslim fasting” and “Buddhist meditation”? People do fast. People do meditate. And it has nothing to do with religion. A lot of what makes “Muslim fasting” Muslim is prayer and dedication to Allah; if you’re removing that religious aspect of it, then you’re just fasting. And fasting is part of a number of religions, so it’s really hard to say which religion it comes from once the religion has been stripped away. As for meditation, meditation gained a lot of traction in the West because of the explosion of yoga. Which is a religious practice in Hinduism and Buddhism (and Jainism). It’s just been stripped of the religion, and like with fasting, meditation is found in many religions around the world; it’s just not that unique.

So, Buddhism is quite famous for being adoptable into other religious practices. Like if you had asked “why can’t someone be Muslim and Hindu?” my answer would have to be a run-down of the many fundamental theological reasons why those two religions are incapable of coinciding in a single person’s beliefs; however, Buddhism or Buddhist practices can be practiced alongside most religions. It’s non-theist, so there’s no creator deity that could contradict the beliefs of monotheists, polytheists, and atheists. Buddhism and Christianity have this whole huge long history, and Buddhism and Catholicism specifically dovetail really nicely together. What you’re talking about is syncretic religion, and it’s pretty common worldwide and throughout history.

The answers to all of those questions depend so intimately on how you build your religions and what their specific beliefs are. Some religions are naturally exclusivist, or you might have soft polytheism. It’s your world and your religions; we cannot make these decisions for you. If you want fundamentalism and bigotry to be a part of your world, then you can build your religions in such a way that those things would naturally occur. If you want harmony across religions to be a part of your world, then you can build your religions in such a way that that would naturally occur. You can even have it both ways! A world is a big place, and how people interact with their religion and the religions of others depends largely on where in the world they are and who else is there with them. A cosmopolitan culture where you have everyone brushing elbows with everyone else will have people developing a tolerance and softening their hardline views that would not occur in a more homogenous society where one religion is dominant.

Delta: A note about bigotry and prejudice: In geopolitics on earth, religious intolerance tends to be about one of two things: first, the majority religion (in the western world, Christianity) feeling compelled to force itself on other populations who do not share their beliefs. Examples of this include the Spanish Inquisition and, to some extent, “evangelical aid.” In Christianity, evangelicalism is a very important concept; sharing the religion is almost as important as a person’s personal faith. Off the top of my head, as Feral discussed, I can’t think of another religion with quite the same focus; so, by eliminating this element of religion, a huge amount of conflict could be eliminated if practitioners weren’t compelled to make all their acquaintances agree with them all the time. (Which is not to say all Christians just walk around proselytizing all the time, but it is fairly common in America; though I understand it to be somewhat less common in Europe, which through both culture and law has become more secular; more on this later.)

Second, it’s also about not wanting to concede power or control. A huge motivating factor behind all the Medieval Inquisitions, including the Spanish Inquisition, was the effort to curb what people in power considered religious heresy or just straight-up religious differences. They thought it was their place to dictate a group’s religious beliefs. Spain in particular was trying to stop the spread of Islam through the growing Ottoman Empire, which comes down to Medieval geopolitics as much as it does the religious differences between Islam and Christianity. Modern Islamophobia and religious conflict falls in this category a lot, too. But if your religions weren’t tied to more extensive geopolitical conflicts, you won’t have politicians using them as leverage to take and keep power like we do, so you could reduce religious tolerance that way, too.

Finally, secularism, which doesn’t directly address your question, but I wanted to mention it. In China, the official Communist Party has been somewhat infamously aggressively secular because religion was seen as a potentially rebellious force. Soviet Russia had similar experiences, both particularly with Muslim populations with whom they have political differences with besides, religion in this instance becoming a motivating factor for rebellion.

This is different from someplace like France, which aims to simply be neutral. Europe, overall, does not share the same public religious zeal that places like Israel, America, and Saudi Arabia have, but that doesn’t mean the conflict isn’t there.

Utuabzu: Something worth considering is are these gods real in the world you’re building? If the gods are demonstrably real, religiousness will be a lot more common and people are probably going to be more accepting of those that worship different deities given that any claims about them being false are easily refuted. Another thing to consider is the difference between philosophy and religion. In the West, Christianity fills both slots for many people (Judaism and Islam also do for some). In much of Asia, however, philosophies like Buddhism, Taoism, Confucianism, Yoga (the Hindu philosophical school, one of six major Hindu schools), etc. are practiced in addition to a more localised traditional religion, often comprised of a local pantheon of gods and some degree of ancestor worship. To some degree, even Christianity is sometimes treated like this, see the Chinese Rites controversy for example. It is entirely possible to have people simultaneously believing in local animistic deities (local forest/mountain/river gods), regional major deities (Sun god, moon god, justice god etc.) and one or more universalist philosophies. Add in the possibility of mystery religions (closed faiths that do not publicise their theologies and often don’t accept converts, see Mithraism, the Orphic Mysteries, or for a modern example, Yazidiism) and ethnic religions that don’t seek or don’t accept converts (see Judaism, Sikhism, Zoroastrianism), and it is very possible to have a wide variety of beliefs coexisting in a society. If they’ve been coexisting over a long period, one would generally expect most people to be aware of the major festivals, ceremonies, etc. of each, and while some may be open to all and treated by non-believers as more of a cultural festival (probably the animist ones), others may be believers-only, or invitation-only. Some festivals might be shared by several religions, because they either come from the same root, or both revere the same prophet/saint/whatever, or both worship the same deity, or maybe just had similar festivals happening at roughly the same time and though mutual influence ended up doing them at the same time. It really depends how you’ve built these religions and what their stances on non-believers are, how long they’ve been coexisting and how orthodox/orthopraxic (emphasis on believing the right things vs. emphasis on performing rituals correctly) they are.

17 notes

·

View notes

Note

hey sorry if this is annoying but i’m kind of dumb but i wanna know what you’re saying about pedophilia and hollywood and the church. and if its not too much trouble could you explain in a way that’s easier? i’m sorry this is anon im just embarrassed

I mean, “easier” I don’t know about, my difficulty settings are not very well scaled and I mean that both in an ironic sense and in an earnest one: I joke, I am humorous about my own style of writing, talking, being, but at the same time I am effectively forced to recognize that I talk in a way that betrays my leanings before too long: I talk too much about sports, I jam postmodernism in at every turn, and the text is everything and nothing is outside the text. All of this is to say that “easier” is, for me, likely going to require “longer” as well, so you’ll have to bear with me. First, to address the Church. It is rife with pedophiles, the Catholic Church has been in one way or another defensive of pedophiles within it as far back as I can think: if there is a meaningful way to use “pedophile” as a contemporary label in a historic context, then anyone who fits that and also is in some way part of the Church hierarchy is going to be protected. This is especially emphasized in the past half-century or so, in no small part due to the way that reports from places like the Boston Globe or the realization of the ubiquity of pedophilia in the Catholic Church in Ireland has allowed for a sufficiently sensational, sufficiently colonial subject of abuse to come to light.

This does not mean that the Church did not do anything wrong before these cases were exposed, has “fixed” anything, because it specifically took decades upon decades of “scandals” to realize that a structural inclination toward allowing (and even, through this process of allowing, encouraging) pedophilia in the Church exists, and in turn it has only resulted in occasional, superficial changes that do not go terribly far past rearranging deck chairs on a ship with no sign of sinking. For decades there have been documented cases where pedophiles were shuffled around in the Church from diocese to diocese, always before the revelation of their abuse could go past whisper, could unfurl into an event, a condemnation. Even in cases where accusations were made, and accepted, there was a superficial act of separation that in fact was merely the same act of transfer, itself disguised, as if an act of transfiguration. And this is merely what has been documented and admitted in order to prevent greater scrutiny. The problem of sex abuse in the Church is systemic.

Žižek has discussed this both in a metaphorical and in a literal sense, the way in which the aesthetics of the Church, the ideology of the priesthood, allow abusers to create a flock of victims, how the ideology around the church specifically feeds into the eventual violence, violence that is not realized or named as violence and thus is understood as something else, as an act of piety, as part of sustaining the priesthood and thus the Church. The Church cannot admit its problems, specifically because doing such would involve forsaking its very nature.

Now, the ways in which the Catholic Church has blood on its hands barely begin here, and its role in colonizing places such as Ireland or the Philippines still persists within the cultures in place to this day. However, even in naming the Catholic Church as part of this violence, one must accept that the structure which allowed them to reach out as they did was in fact one of colonial power, a colonial structure that is maintained even today. Any discussion of the Pope as part of a “global elite” that relies upon theories about secret societies and ideation of groups such as the Jesuits as dark forces of collusion misses the forest for the trees: the Church is almost unfathomably fucking depraved on its face. Imagining a deeper structure to it is denying the materially-demonstrated violence that is immediately apparent.

The Jesuits, in particular, are a sort of “occultic” or dark figure because indeed they have a history of taking part in some of the Church’s most reprehensible actions, but have also developed into one of the more important forces for liberation within frameworks of Catholic teachings on Social Justice. I am biased, I confess, for having gone to a Jesuit high school, but Jesuits are often open to some wild shit as far as theology goes. Catholicism, as a site of resistance, is additionally able to do as much: the globalizing impetus realized in Catholicism as part of colonial violence was in many ways reversed by the syncretic traditions found within the wide tent of Catholicism: the many ways in which it was largely up to relatively limited groups of missionaries to pass on the doctrine of the Church lead to numerous opportunities for doctrines just a hair away from heresy to develop as the predominant belief in any given area. And this is part of where I find the Catholic Church to be an incredibly interesting, even positive force: the way that the Catholic Church provides a site of decolonization, of creating the idea of syncretic tradition that can be meaningfully developed out of colonial legacy, the possibility of a postcolonial Catholicism is truly invigorating.

But, anyway, that is a lot of words about a short point: when a more specific entity is needed than just the Church as far as “occult” and “new world order” goes, the Jesuits are often invoked. More generally, Catholics are often seen as odd by conventional American beliefs because of how developed the idea of Protestant Christianity as “truer” than Catholicism is in America. So, you get a soft invocation of the way that people like Jack Chick see Catholicism as occultic, satanic, evil in a sense far separate from its contemptibility as a colonial artifact.

This is, in turn, transferred onto the idea of an “elite” and “pedophile rings” in politics, entertainment, so on: the idea that rather than many manifestations of the same tendency, there must be a conspiracy going on. This is a way to refuse to recognize how similar conditions enable similar patterns of abuse, to ascribe a sort of supernatural power to the events going on, to place them outside of the “Real” and thus as part of something that can be exorcised. That it echoes the Satanic Panic of the 90s is hardly a coincidence.

And of course, as history so often has done, it is realized through an implied antisemitism that conveniently ignores any meaningful analysis of the structural factors at hand in favor of various derivations of blood libel and related reactionary ideological structures. Whenever imagery of a concealed elite is present, rather than an acknowledgement of the violence allowed by the ideology openly endorsed in the process of globalization, one conducts a sleight of hand that would make Machiavelli blush. Without naming a single person, there is a very clear way in which one lays out the acceptable victims, the assumed subjectivity of the perpetrator, and those who enable it.

Anything about a “Hollywood elite” is either implying antisemitism, relying on antisemitic notions about “Hollywood” as a hyperobject (a collection of people, places, organizations, cultural products) or is just openly antisemitic. Allusions to the Occult allow for a certain lurid aestheticization that separates the understanding of the violence from any actual analysis. There are many, many pedophiles who work with child actors and who are allowed to get away with years upon years of abuse because it would damage their reputation but moreover the reputation of those who would have been able to stop such abuse but chose not to. This extends to all kinds of violence, all sorts of sexual abuse, abuse in general. It is a tendency present in police, in the military, in politicians, in youth sports, in any organization of sufficient size. But the focusing upon the idea of a “Hollywood occult elite” is very specifically relying on certain notions that a reactionary audience already holds in order to stoke certain flows of libidinal energy, to create an enemy lurid enough to fight.

tl;dr - it relies on antisemitism and other related ideas in order to ignore that the problem is not “pedophile rings” but in fact is an attitude toward abuse present throughout American culture

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Why Christian Witchcraft

Sometimes I find the word “child” funny. Here is a growing being that is allowed to do fewer things because they are growing and not “adult.” Navigating the waters of what a child is and is not capable of can be daunting. You don’t want to take away too much of their power, their autonomy, but at the same time you want to ensure their safety. Too many parents go too far. They encroach upon a child’s autonomy to ensure their own comfort. They want to know the child still needs them. They want a successful child and a child who is happy and so they take away the opportunities that child has to experience the world. They do so by saving their child. Bringing the forgotten homework assignment to school. Dealing with the schoolyard bully themselves. This all stunts a child’s emotional growth.

In so many ways, the church has done the same. Church leaders have saved congregations who have too much on their plate, insisting that they would do the hard analysis. Church leaders would say the prayers. Church leaders would perform the spiritual rites for those who were not “ready.” They made church a mystifying art that was beyond most people.

Some went as far as to limit the spiritual growth of individuals based on their gender or sexual orientation. They balked at those from other cultures who had vital information to share with the masses, and branded it as heresy.

Witches know no limits. They insist on taking charge of their spiritual growth. They let nothing about their body, mind, or spirit be used against them in their journey towards spiritual peace. The witch allows themselves to grow and flourish on their own.

The witch’s reliance on self and on small groups of likeminded witches is what allows them to grow spiritually. The connection to nature and to others is organic. The autonomy of the individual paired with the intentionality of community is what the church is lacking. They have tried to recreate it with small group experiences. This works so well when people are willing to participate. However, for those who have been taught to be dependent, they are no longer interested in the church. They don’t want to see the church change. They don’t want to see it die. They just want to see it. Once a month of course.

Christian witchcraft and syncretic faith is the future of the mainstream protestant church. Of that I am sure. All that will be left are those pushing boundaries, and those providing services. If you are not in one of those categories, then your church will not survive.

120 notes

·

View notes

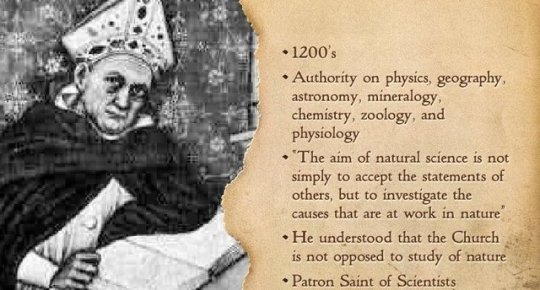

Photo

Catholic Physics - Reflections of a Catholic Scientist - Part 40

Free Will and God's Providence - Part III. The Problem of God's Grace

"Do not say 'It is the Lord's doing that I fell away', for he does not do what he hates.

Do not say 'It was he who led me astray', for he has no need of the sinful........

It was he who created mankind in the beginning, and he left them in the power of their own free choice." - Sirach 15:11-15

The objections to Free Will stated in Part II of this series were

Physics gives only one future for the Universe;

Our brains are pre-wired, so moral choices are not possible;

Our environment determines what our moral choices will be;

God's grace determines our actions.

I countered the first three objections in Part II, and in Part III (here) will examine the most difficult, #4, using in part propositions set forth by Fr. Luis de Molina, a 16th century Jesuit theologian and philosopher. Before giving these arguments, I should summarize the Church's position on free will and God's foreknowledge. Please note that as a theological novice, I would be grateful for corrections and emendations where I err or am wanting. The term "grace" in what follows is used without definition or exegesis (that would need a book), but my meaning is that of "Actual Grace" (God's gift undeserved by us), the push the Holy Spirit gives us to do moral deeds and salvific acts.

THE CATHOLIC CHURCH ON FREE WILL AND GOD'S GRACE

"To God, all moments of time are present in their immediacy. When therefore he establishes his eternal plan of "predestination", he includes in it each person's free response to his grace..."For the sake of accomplishing his plan of salvation, God permitted the acts (The Passion of Jesus Christ) that flowed from their blindness." - CCC, 600

A brief account of the history of the teaching of Catholic theologians on free will and God's grace is given below. For a more extended explanation see the references below.* In the Old and New Testaments are many references to the tension between God's Will and man's free will (including the most excellent one from Sirach, given above). See On Grace and Free Will for a compendium of these.

ST. AUGUSTINE ON GRACE AND FREE WILL

St. Augustine of Hippo laid the foundations for the Church's teaching on God's grace and man's free will in his treatise against the Pelagian heresy, "On Grace and Free Will". His arguments, based on Scripture, can be summed up in the following quote:

".. not only men's good wills, which God Himself converts from bad ones, and, when converted by Him, directs to good actions and to eternal life, but also those which follow the world are so entirely at the disposal of God, that He turns them wherever He wills, and whenever He wills [emphasis added]— to bestow kindness on some, and to heap punishment on others, as He Himself judges right by a counsel most secret to Himself, indeed, but beyond all doubt most righteous." St. Augustine, On Grace and Free Will, Ch. 41

THEOLOGIC ARGUMENTS ON GRACE AND FREE WILL

If it is by grace given by the Holy Spirit that God affects men's will, and if, as St. Augustine says, this is done "wherever He wills, and whenever He wills", where is man's free moral choice? In order to unravel this theological knot, we have to think about how God bestows grace, given His omnipotence, His omniscience, and His will to create good.

To give in detail the theological arguments on this question would require a chapter, not a blog post, so I'll summarize the extreme points of view by an example. (For fuller accounts refer to the references below, particularly Controversies on Grace.) Consider St. Maximilian Kolbe, who took the place of another prisoner at the Nazi concentration camp, Auschwitz, to die by starvation and carbolic acid injection. We can think about this salvific act in two ways:

Scenario 1--God wills that St. Maximilian Kolbe acts as he does and knows by His "Free Knowledge" that St. Kolbe will perform this salvific act. He knows that because he wills to give him grace ("efficacious" grace) to perform the act.

Scenario 2--God knows by his "Middle Knowledge" that St. Maximilian Kolbe, given God's grace, would perform this salvific act, but the performance of the act is dependent on St. Kolbe's free will assent to that grace. This grace is "neutral", that is to say it is neither "efficacious" nor "sufficient". ("Sufficient grace" is that which would be given by God even though He knows it will not be used.)

Scenario 1 reflects the Thomistic interpretation of Grace and Free Will, emphasizing the supreme sovereignty of God, His omnipotence and omniscience. The Thomists add an extra impetus, Divine Premotion or Predetermination such that good moral actions will "infallibly result", but since these actions are not necessarily invoked, free moral choice is still available to the agent. Both Boedder and I are puzzled by this:

"If we object to this that it is exceedingly difficult to understand how a creature thus predetermined can possibly have the actual use of its freedom, our opponents do not deny that there is some mystery in this. But they refer us to the incomprehensibility of Divine causation at once most sweet and most efficacious." Physical Premotion and Predetermination, Bernard Boedder, SJ.

The philosopher Robert Koons has attempted to explain this apparent "incomprehensibility" by symbolic logic, legerdemain that establishes the identity of the propositions below, such that free will is still operative:

The character of X is such that he freely wills to do the morally correct action in circumstance C;

God predetermines the moral choices of X by efficacious grace.

(I have to confess I don't understand the symbolic logic manipulations or the final conclusion.)

Scenario 2 gives a Molinist interpretation, emphasizing the importance of man's free will. There are variations of this position--Congruism, Syncretism--that vary the importance of God's sovereignty in relation to man's free will. Thomists object to the Molinist position because it apparently sets limits to God's authority. I don't agree with this objection. God gave Adam and Eve freedom to commit Original Sin, as a necessary consequence of free will. If He did not, if all we do--sinful and good--is by His will, not ours, then we are puppets on a stage; the whole notion of moral responsibility fails.

THOUGHTS ON PRAYER AND FORGIVENESS.

As a Catholic I pray privately and in public for the Holy Spirit to give me the grace to do the right thing and for those I love to do also. If our actions are pre-ordained by God then these prayers are futile, and that I cannot believe. Thomists object that active praying, absent God's pre-ordained outcome for the desired event, smacks of the Pelagian heresy that man can save himself without the grace of God. The theologian Thomas Flint counters this argument: praying for the Holy Spirit to make you better, for example to rid yourself of an addiction, is praying for God to do something TO you, not FOR you and is certainly dependent on God's grace.

Now we come to what the initial thrust of this series of posts was all about: can we hold those who commit sins morally responsible for their actions and can we forgive them for their sinful deeds. Given the Thomist view, that God predetermines our moral behavior, I don't see how one can hold sinners responsible for their actions and so forgiveness is automatic. Given the Molinist view, that we are freely responsible for our actions, then we can be held responsible for sins. But as Christians, we can forgive the sinner, but not the sin.

Finally I'll say that I'm not entirely satisfied with the Molinist interpretation. It seem to me that if God knows what we will do--even if he does not determine that we do it--we are not totally free in our moral choices. There need to be options, different possibilities for what we can do, in order that freedom of choice--free will--be exercised. In the fourth post of this series I'll explore what quantum theory might offer to give this freedom, with God's complete knowledge of the future and will for what occurs to hold.

*REFERENCES

Controversies on Grace, The Catholic Encyclopedia

Divine Providence, the Molinist Account, Thomas Flint.

Dual Agency: A Thomistic Account of Providence and Human Freedom, Robert Koons.

Molina / Molinism, Alfred Freddoso.

On Grace and Free Will, St. Augustine of Hippo.

Physical Premotion and Predetermination, Bernard Boedder, S.J.

From a series of articles written by: Bob Kurland - a Catholic Scientist

0 notes