#I do know the context for this because I have musicologist friends

Text

spotify discover weekly providing some bangers this week! never knew I needed Hieronymus Bosch Butt Music

#I do know the context for this because I have musicologist friends#it's the sheet music from the butt guy in garden of earthly delights#but truly quite the eye-catching title in my discover weekly playlist!#Spotify

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

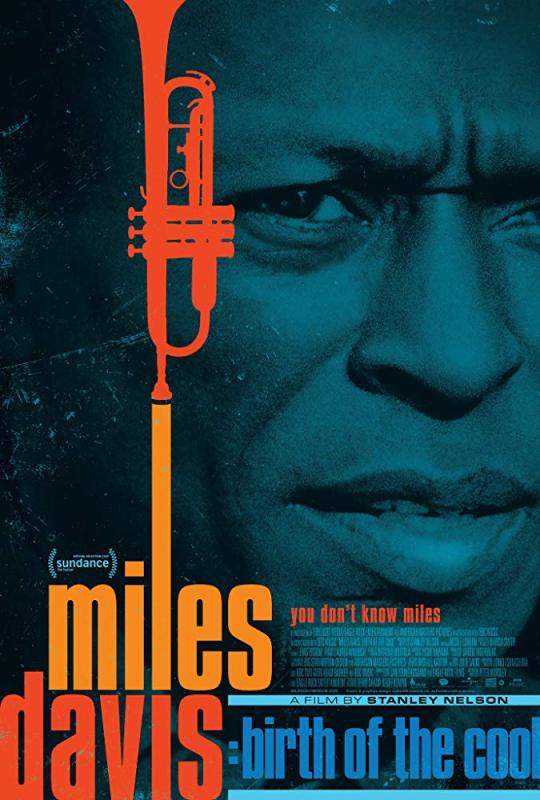

A detailed look at Stanley Nelson’s Miles Davis documentary: “Birth Of The Cool” (2019)

The following is an in depth review of the New York premiere weekend of Stanley Nelson's Birth of the Cool which I attended on Sunday August 25th, 2019. Where applicable I have added some additional information about Miles' history and career to give context for new fans in the Davis orbit.

Introduction

Miles Davis. All you need to do is say the name and many adjectives are conjured-- restless innovator, genius, temperamental, swagger, fashion icon, tenderness, mentor. All of these themes and then some are explored in famed director Stanley Nelson's fantastic new documentary Birth Of The Cool. For casual music lovers and devotees of Davis' extensive genre breaking career, there is a lot on offer. Initially when the film was announced, following Don Cheadle's creative vision of the trumpeter's retirement period with Miles Ahead in 2015 the thought in my mind as a lifelong Davis fan was what could possibly be covered that I don't already know? The answer is quite a bit. Through combinations of interviews with those who knew him best, musicologists, fellow musicians such as Jimmy Cobb, Herbie Hancock, Ron Carter, Wayne Shorter, Lenny White, Carlos Santana, family friends, and ex wife Frances Taylor Davis, it creates quite an intimate portrait.

By far the most impressive feature of the two hour documentary is the coverage of Miles the man, not as an mythical superhero figure as some documentaries or biopics are wont to do with their subjects. Nelson covers virtually the entire spectrum of his career and life: personal reflections from Davis' joys following Dizzy and Bird to 52nd street, meeting ex wife Frances Taylor, the unbearable suffering of his heroin habit quitting cold turkey, the relapse into drug use to deal with intense physical pain, his thoughts on creation, the freedom of being a black man in Paris, and the disappointment of coming home and seeing the racism again, among other topics. Davis is approachable and endearing to the audiences voiced by actor Carl Lumbly reading portions from both Miles: The Autobiography and interviews from his later years.

The Music and Film Production

Nelson's interspersion of decade specific footage to track the trajectory of the trumpeter's varied career is incredibly clever featuring stock footage, fast cuts of classic films, and significant political events. The use of Wayne's Shorter's “Paraphernalia” from Miles In The Sky (Columbia, 1968) as the director announces the decades through slick headers is striking. It is striking in part because it drives home the point of how the trumpeter was always moving forward. Though he always went forward musically seeking to change with the times and grow, Miles' previous musical breakthroughs from Birth of the Cool (Capitol, 1957 rec. 1949/50) Round Midnight (Columbia, 1956) Kind of Blue (Columbia, 1959) Sketches of Spain (Columbia, 1959) Miles Smiles (Columbia, 1966) On the Corner (Columbia, 1972) The Man With the Horn (Columbia, 1981) and Tutu (Warner Bros, 1986) just to name a few, informed EVERYTHING he did; and that's important to realize for newcomers should they wish to make the deep dive to access his entire catalog. The use of “Agitation” from E.S.P. (Columbia, 1965) as Frances Davis was discussing the domestic violence she experienced, as well as during the recounting of the brutal beating by a drunk police officer outside Birdland shortly after Kind of Blue was issued made the viewer almost feel those incidents. A wonderfully smart choice by Nelson to use selections from Round Midnight, Workin' (Prestige, 1956) Kind of Blue, Sketches of Spain, Bitches Brew and On the Corner at the appropriate moments was masterful and lead a gentleman to remark at the post film Q&A that the film's totality was a composition and the director was on par with a musician.

The reasons for having an actor voice Davis was due to the fact that although Nelson had access to 40 tapes of Davis in conversation with Quincy Troupe for Miles: The Autobiography, the director explained at the post film Q&A that the interviews were recorded on a cheap tape recorder, with quite a lot of background noise, so the tapes were unusable. It was decided to use portions of the autobiography and later interviews to tell Miles' story. His actual voice is heard in the documentary via session reels from Freedom Jazz Dance: The Bootleg Series, Vol. 5 (Columbia/Legacy, 2015) the 50th Anniversary edition of Kind of Blue and there is some gold there. The archival photos and footage are stunning. Davis' friend Corky McCoy had brought two reels of film, and had a 16mm camera for which he took a class at UCLA and provided a lot of source material. The scenes of Miles boxing are phenomenal, and one sees that he had as much passion for the sweet science as he did for music, and cooking. He had a terrific left jab! There were many previously unseen non performance photos that were obtained through photographer estates, and friends that add another deeply personal dimension to things. Also essential to the narrative arc is that contrasting views are presented. Stanley Crouch's frank admission of not getting, liking or understanding the 70's period met by a harsh, but true rebuttal by Carlos Santana is just part and parcel of the documentary's mission to feature everything.

Miles' Humor, Stance as a Civil Rights Activist

Over the course of the film's two hours, there are some hilarious bits of the trumpeter's blunt commentary on life experience, and thoughts on other musicians. For those with a deep knowledge of him, there are no new revelations, but they are quite funny just the same. Miles is heard in session reel audio “I can't play that shit, man!” and even more uproarious in a story relayed by Wayne Shorter of a well known episode, the trumpeter's response to black folk playing the blues out of suffering is classic: “you're a GODDAMN liar!!!” Finally, tenor legend Archie Shepp discussed wanting to sit in with Davis to which he was met with a stone cold “fuck you!!” which brought a unison chuckle from the Film Forum audience.

As funny as his remark was regarding his teacher's naive comment, it boldly demonstrated Miles' commitment to exercising the civil rights of black people, and the pride of being black. In 1957 when Miles Ahead was first issued, Columbia chose a white woman sailing on the cover because they felt that it would show that the trumpeter crossed over to a mainstream (read: white) audience. When Davis saw the cover, he incredulously asked “who is this white bitch on the cover?” The album was promptly reissued with an image of him instead. In 1961, he demanded that Frances Davis be photographed on the cover-- the first in a series of covers featuring black women on the trumpeter's records which for the time period, an incredibly progressive move. Cicely Tyson was featured on the cover of Sorcerer in 1967, another emphatic statement on the beauty of black women. As the film discussed early on, Miles saw his dark complexion symbolic of power, and that is something he exhibited time and time again. Although not covered in the film, the famous February 12, 1964 concert that produced My Funny Valentine and the companion Four and More brought forth a rare passion from the players involved because they had learned Davis had waved the fee for the show as it was an NAACP benefit. Also he had felt strongly about the apartheid in South Africa during the 80's and refused to play there. He was committed to the civil rights of African Americans up until the day he died.

Transition to Superstar in the 80's

As Miles started back on the road to health in the early 80's after the 1972 car wreck that caused him considerable physical pain and causing him to dive back into substance abuse, he emerged a new man in the 80's. He cut Man With The Horn with a new band, diving into the new decade's vision of funk. Along the way he tapped into Caribbean flavored grooves, synth pop, and hip hop. He did interviews (most memorable, his appearances with Bill Boggs and on the Arsenio Hall Show) television shows like Miami Vice, and played a leading role in the film Dingo. Nelson's choice of footage and commentary from musicians during this period show him as positively ebullient, Davis was healthier, painting and cooking, his passions with increased zeal. The footage of the Tutu session, showing the trumpeter's investment in current pop music of the day, and with Prince is quite jubilant.

Touching Moments

There are several touching moments scattered throughout the film that Nelson uses to truly allow the audience to identify with Davis and those who loved and cared about him. Three particularly stood out. The star of the film was without a doubt Frances Davis who had detailed a few stories previously unbeknownst to me. When Miles fell in love with her after seeing her in a production, she was heavily courted by top Hollywood and Broadway actors of the day, with unshakable confidence, and wry humor she professed in the film that as a dancer, her legs were her best asset and that was like with everyone else, won Miles over. Though he had many romantic partners, he and Frances clearly had something that was beyond special. He admitted due to his drug use that he was a bit jealous of the attention she received after being cast in West Side Story and made her quit the show. The emotion she felt when retelling the regret she had when leaving the show, and her career behind was palpable and heartbreaking. She would frequently disappear upstairs in their apartment and gaze longingly at her ballet slippers between bouts of cooking. Lumbly, as Miles intones in his signature rasp how he wished he knew years later that Frances was the best thing to ever happen to him-- a fact he was unaware of when they were together.

The second really touching moment of the film occurs towards the end of Miles' career during the famous 1991 Montreux concert conducted by Quincy Jones where he revisited classic Gil Evans arrangements. There was no musician closer to Davis from 1983-1991 than Wallace Roney. In the film, Roney explains his feelings at Miles indicating he wanted to get the quintet with Wayne Shorter, Herbie Hancock, Ron Carter and Tony Williams back together but also revisit the Gil Evans material, he had the sudden realization Miles had little time left. The rehearsals for the July, 1991 Montreux concert were vigorous, and Davis showed up for only a few. One of the most challenging pieces was “Pan Piper”. Roney, sensing what his mentor and dear friend was feeling physically jumped in to assist. The piece was not rehearsed but called at the concert, and Davis, summoning the strength of his youth plays a remarkable solo, sharing phrases with Roney. At one particularly difficult passage, Roney jumps in, but Miles is also playing the same phrase. Like Muhammad Ali winning the title a third time in the 1978 rematch with Leon Spinks, Davis managed to reach back and heroically play through the tune, as he did the rest of the concert, providing a memorable late career moment.

The third deeply emotional moment is shared by Miles' last partner, friend Jo Gelbard. As the trumpeter was rushed to the hospital, she detailed some of their last moments as Miles was in his bed prior to having a stroke. The moment has a gut wrenching, aching beauty similar to a great solo like on “Blue in Green” or “Time After Time”. She tells of a conversation that she and Miles had where he said “God doesn't punish you, you get everything you want. You just have limited time.” Indeed, a provocative thought on mortality.

Closing Thoughts

Attending the Birth of the Cool New York City premiere weekend was a marvelous experience. While fans can quibble about what was not included, what albums were glossed over, the lack of bands represented, etc the documentary set out what it was supposed to do; present a balanced, comprehensive portrait of Miles Davis the musician, and human being. While it would have been nice to hear from band mates like George Coleman, Keith Jarrett, Airto, Kenny Garrett, Foley, Marilyn Mazur, Benny Rietveld, Jack DeJohnette, Chick Corea or Dave Holland, many of them are featured in the Miles Davis Story (2001) and those interviews can be used as a supplement to this new film. Stanley Nelson treats Davis with respect, and veneration detailing the human experience at each point. The wealth of unseen photos and film footage are a nice bonus for diehard fans, and the well known stories that they all know, will be enlightening to casual and new fans of Davis. The Q&A on the Sunday, August 25th matinee was incredibly insightful, with probing detailed audience questions, with an added treat: The ageless 95 year old drumming pioneer Roy Haynes in the audience! One of the few surviving titans to have played with Charlie Parker. The documentary is on a par with Jaco, Chasing Trane and Bill Frisell: A Portrait.

Rating: 8.5/10

(c)2019 CJ Shearn

#miles davis#legend#change#blackness#herbie hancock#wayne shorter#john coltrane#tony williams#jazz#music#documentary

13 notes

·

View notes