#Indigenous policy & reconciliation in Australia

Text

For some in Indigenous Australia, reconciliation can never be revived.

(ABC News: Emma Machan)

Is reconciliation really dead after the Voice to Parliament was voted down?

By Indigenous Affairs Editor, Bridget Brennan

ABC News Australia - 22 October 2023

•

•

Indigenous leaders who campaigned for Yes have released a statement pledging to fight for justice.

(Supplied)

‘Shameful victory’: Indigenous leaders’ bitter lesson from Voice campaign.

By Mike Foley

The Age - October 22, 2023

•

•

Indigenous leaders have written an open letter to Australia’s Prime Minister Anthony Albanese after the Voice referendum was defeated.

(ABC News: Michael Franchi)

Indigenous leaders break their silence, call referendum defeat 'appalling and mean-spirited'.

By Indigenous Affairs Editor, Bridget Brennan

ABC News Australia - 22 October 2023

•

#Australian Indigenous (Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander) peoples#Race relations in Australia#Indigenous policy & reconciliation in Australia#Democracy & social justice in Australia#Australian Indigenous Voice to Parliament referendum 2023

1 note

·

View note

Text

For Australia, 26th January is invasion day, and that's literally it.

Today is a horrifically sad day in Australian history. Invasion day.

That's literally all it is.

Please please please do not join in the chorus of racism wishing anyone a "Happy Australia day" on the 26th of January

We can, have and are moving forward together as a country,

But we cannot truly do so if a celebration of our country and identity is held on the literal anniversary of the brutal and long-standing invasion, massacre and occupation of Australian aboriginals, the first peoples of Australia.

This invasion and subsequent violent Colonisation was full of many horrors that lasted well into the late twentieth century, and the long-standing repercussions of which have lasted to this day.

The stolen generations , in which generations - multiple generations of young aboriginal children were literally stolen by white colonists from their families, sent to missions, (detention boarding "schools ") , in which they were converted to Christianity and prepared for menial jobs, punished if they ever spoke their own languages, and subsequently put into the service of white families, with the intention to be bred out, never to see their families again. Never to be educated about their home, their families, their land, their culture, their languages, their history; they are the oldest continuing culture on earth. The last of these missions were in effect until 1969. By 1969, all states had repealed the legislation that allowed the removal of Aboriginal children under the policy and guise of "protection".

The indigenous health, longevity and poverty gaps still exist. Access to medicine, medical care, healthcare, a western education, all things we deem human rights by law, are not accessible to many rural communities still. They are provided, but in western ways, on western terms, with a gap of understanding how best to implement those services for an entirely different culture , that we do not have a thorough understanding of - that was what the referendum was about: , how best to implement the funds that are already designated to provide those services, because it's not currently working or usable by those communities. Our aboriginal communities are still not treated equally, nor do they have the same access we all enjoy to things like healthcare services, medicines and western education.

It is horrific and insensitive to therefore celebrate that day as our country's day of identity, because it's literally celebrating the first day and all subsequent days of the invasion, the massacres, the stolen generations, the subjugation and mistreatment, the inequalities that still persist today. It celebrates that day, that act committed on that day, of invasion , violent brutal massacres of Aboriginal people, as a positive, 'good' thing. As something that defines Australia's identity and should define an identity to be proud of.

That's nothing to be proud of.

Our true history is barely taught in our school curriculum, in both primary and secondary school. Not even acknowledged.

It needs to be.

We cannot properly move forward as a country until that truth is understood by every Australian, with compulsory education.

January 26th is Not 'Australia day'. It's Invasion day. It's a sorrowful day of mourning.

Please do not wish anyone a "happy Australia day " today.

It's not happy and it's not Australia day.

Australia day should be at the end of Reconciliation week that is held from the 23rd May to 3rd June.

A sentiment that is about all of us coming together as a shared identity within many identities, accepting and valuing each other as equal, a day that actually acknowledges Australian aboriginal peoples as the first Australians - because they are.

This is literally about acknowledging fact - that is the truth of Australian history. Aboriginal cultures should be celebrated and embraced, learnt from, not ignored, treated as invisible and especially not desecrated by holding celebrations of national identity on anniversaries of their violent destruction.

Australian aboriginal peoples, cultures and histories, should be held up as Australia's proud identity of origins, because it literally is Australia's origins.

That's a huge, foundational integral part of our shared identity that must be celebrated and acknowledged.

Inclusivity, not offensive exclusivity. Australia day used to be on 30th July, also 28th July, among others. Australia Day on the 26th January only officially became a public holiday for all states and territories 24 years ago, in 1994. It's been changed a lot before. It can certainly be changed so it can be a nonoffensive , happy celebration of our shared Australian national identity for everyone, that respectfully acknowledges and includes the full truth of our whole shared history, not just the convenient parts.

There is literally no reason it can't be changed, and every reason to change it.

#Always Was Always Will Be

#Australia#26th January#Invasion day#Important#Morality#Ethics#Australian aboriginal peoples#Always was always will be#Truth#Psa#Indigenous Australians#Indigenous Australia#Aboriginal Australians#Aboriginal children#Aboriginal people#Australian history#Australia day#Australian national identity#Inclusivity#Shared#Auspol

99 notes

·

View notes

Text

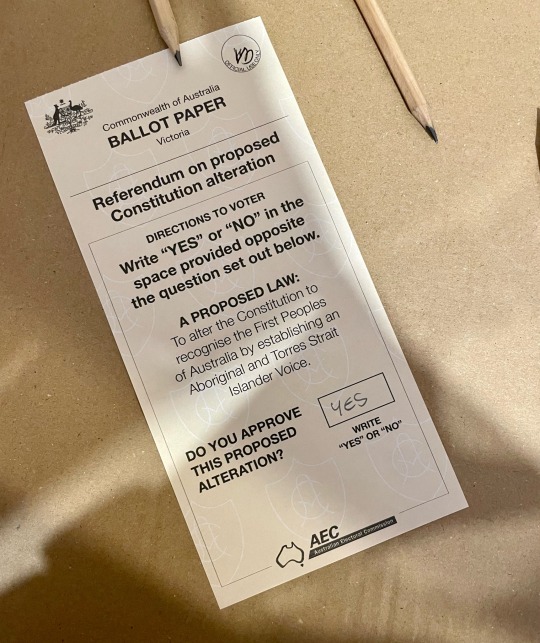

Today, Australia is voting in a referendum on the Voice to Parliament: an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander advisory body, enshrined in our constitution, that will give our First Nations peoples a say on policy that affects them. A Voice would be the first step in Australia reckoning with its history: a history which has so far ignored and silenced — often violently — the voices of the oldest living culture on the planet.

It is not lost on me that I am a non-indigenous person being asked —again — to weigh in on the future of indigenous Australians. I don’t take that lightly, nor am I sure whether a referendum is right for this. I would have felt perfectly comfortable with a Voice being enshrined without my input. Maybe that would have spared my indigenous friends the emotional toll of begging for political recognition.

But it is the way it is, so I’m voting Yes. I’m voting Yes on Wurundjeri land. Stolen land. Land where I live the kind of comfortable life out of reach for many indigenous Australians.

I’m voting Yes because it’s time for real reconciliation.

And I’m voting Yes because here hasn’t been a single argument from the No camp that I could square with doing the right thing. They say the Voice will divide Australia, but Australia is already divided. They say it will give indigenous Australians an unfair advantage. It won’t, but it will hopefully start undoing the years of unfair privilege white Australians have had in deciding their fate. The No camp has told us, “If you don’t know, vote no,” as if that’s an acceptable thing for our country’s civic discourse. As if the answer to not knowing is not to find out, not to ask questions, not to make an informed decision weighed by evidence.

They say indigenous Australians don’t want it. The polls say eighty percent of them do.

In all areas related to quality of life, non-indigenous Australians are leaps and bounds ahead of the people that lived on this land first. Indigenous Australians aren’t living as long as non-indigenous Australians. They are being incarcerated in disproportionate numbers. They don’t have the same access to high quality education. Domestic violence and sexual abuse rates are disproportionately higher in indigenous communities. The economy, housing, employment…the list goes on and on and on and the stats remain dire.

We are already living in a No world. It isn’t working.

It’s time for a change. I don’t know if we’ll get it. I’m fearful that we are too conservative and too selfish a nation to take this one small step, but I hope desperately when I wake up tomorrow we will have said, “Yes. Have a seat at the table. It’s long overdue.”

#bear with me on this#I know there’s a lot going on in the world but I had to get this out#the voice to parliament#long post#auspol

89 notes

·

View notes

Text

@titleknown recently recommended this paper on decolonization after reading my posts on Decolonization is not a metaphor, and I finally got around to reading it.

First things first - this is a lot better. This feels more like an academic paper than a screed and it makes more of an effort to be cohesive and coherent.

It's still not great. Lately on here I've been very critical of political theory, and I think this replicates many of the same writing tendencies that I hate. There are two really big ones that stood out to me.

The first is a failure to properly contextualize your writing. This consists of a number of things like defining your terms (I am still not entirely sure what the author means by decolonization) but also stating and justifying your assumptions. The author makes several, most of which I think are perfectly defensible, like arguing that there are sufficient commonalities between the experience of all of the Native American tribes and the Australian aboriginal tribes to lump them all together under a single label of indigeneity.

This is not actually that much of a sin - academic writing situates itself within an academic context that outsiders like myself are not privy to, so I think a charitable (and probably correct) interpretation is that this framework is actually pretty consistent if you're a member of this field. I still find it frustrating.

The second is much less forgivable. Texts like this drive me crazy because of their lack of interest in specifics; they are far more interested in painting abstracted narratives than trying to equip their readers with a better understanding of the situation on the ground. Whenever I read a text that spends more time playing with academic language than examining the real world I want to tear my hair out.

But there are some specifics, and they are by far the most intriguing aspects of this paper.

One example we might look at is the emerging treaty negotiations in several Australian jurisdictions. While the federal government remains resolute in its opposition to negotiating treaties with First Nations, several sub-national jurisdictions (Victoria, Queensland and the Northern Territory) have committed to this work, which, it is envisaged, will take place over several decades to come.

This is fucking wild. Several Australian states have gone against the policy of the federal Australian government and committed to negotiation with First Nations. This is the most clear-cut example of decolonization in action that I've ever heard of, and I have a thousand questions.

Which First Nations? What are their negotiating goals? How are these nations governed, and how many people do they represent? What political circumstances have caused these Australian states to negotiate with them? How do indigenous Australians feel about this? How much political support is there from non-indigenous Australians? Is this "commitment to negotiate" codified in any meaningful way? Who are the public figures behind this?

How did this happen, and what will it mean?

Let's go ahead and read the rest of this paragraph.

Treaty negotiations will inevitably be agonistic; there will be considerable, irresolvable conflict over the settler state’s continuing occupation of Indigenous territories. Were this agonistic engagement to remain at the level of discourse – through, for example, the intended processes of ‘truth-telling’ that will accompany treaty negotiations – without leading to significant structural transformation in the relationships between First Nations and the state, we would have to assess the process as being one of agonistic inclusion. If, however, these agonistic engagements produce material change in the relationships between First Nations and the state (in the form of the return of land, substantial reparations, and a commitment to supporting First Nations governance and self-determination) then we might assess this engagement as edging towards agonistic decolonisation. Treaty negotiations that result in these kinds of material changes would, by definition, be a form of radical innovation in Australian democracy.

There isn't even a fucking citation for me to learn more about this. I'm gonna have to google it on my own time.

We get a fascinating window into a real-life example of potential decolonization, and as soon as it's opened, it's shoehorned right into the theoretical framework being advanced by the paper and buried.

This is everything! "How do we achieve results" is literally the only question that matters. How do the descendants of the victims of a series of horrible genocides who remain isolated from and oppressed by societies that do not care about them achieve good lives for themselves? Everything else is noise.

And there's a lot of noise. This paper is very concerned with this concept of agonism (basically conflict theory) and mentions some variation of the word agonism somewhere in the neighborhood of 100 times. There's also a lot of the standard cliches that are common in decolonization writing:

What Tuck and Yang make clear is that while related movements – such as those for equality-based citizenship, human rights, anti-racism and social justice – are important to anti-colonial struggles, they are not the same as justice in the context of settler colonialism and indigeneity, and they do not necessarily respond to Indigenous peoples’ relationships with the land.

Bolding mine. You don't have to respond to anyone's "special relationship with the land." This is a nonsense phrase people made up to do the noble savage thing without making it obvious.

Then we have the political systems question:

This view assumes that the institutions of democracy are appropriate for governing Indigenous lives, rather than understanding these institutions as colonial – as being in an ongoing colonial relationship that fails to acknowledge the sovereignties of the Indigenous peoples whose lands they occupy.

Decolonization writing often does this funny little dance with democracy - it could easily critique the way liberal democracy fails to live up to its own promises and point out the bad outcomes it has delivered for indigenous people, but it often goes a step beyond that - it questions whether democratic institutions are "appropriate for governing Indigenous lives."

Which isn't inherently wrong to question, given the flaws in modern democratic institutions, but it does kind of beg the question of what you are proposing as your ideal system (something that all of these writings are extremely cagey about). Are the Australian First Nations run in a democratic manner? I would assume so, but the language used here is sufficiently tortured that it concerns me - my concerns are entirely with indigenous people, and if the organizations negotiating on their behalf do not represent them, that's kind of a problem.

But again, since we're allergic to specifics, I'll have to research that on my own time.

And then there is the omnipresent question of land back.

The discursive focus of agonistic inclusion does not adequately disrupt the status quo in any material sense, nor does it question the dominance of liberal political institutions, and nor does it return Indigenous lands to Indigenous control.

This paper really only talks about land back when quoting from Decolonization is not a metaphor and then in asides like this one, which is fair, but I think that blithely accepting the assumptions behind statements like this one makes it very hard for me to take this writer seriously.

There are a lot of potential answers to the question of why land should be put under indigenous control - there's the aforementioned noble savage nonsense, there's the blood and soil ethnonationalist stuff, there's the really long form capitalist property rights approach where you send it back to the last known owner who wasn't murdered for it and then search for a descendant, and so on and so forth. And none of it really holds together, and yet it finds itself in all of these writings without a scrap of justification.

I think more land should be put under indigenous control because the societies these people live in have marginalized and impoverished them and I favor anything that works to undo that - this is the only reason that makes any sense to me.

All of which is to say - definitely more sane, still disappointing.

47 notes

·

View notes

Text

Australians have resoundingly rejected a proposal to recognise Aboriginal people in its constitution and establish a body to advise parliament on Indigenous issues.

Saturday’s voice to parliament referendum failed, with the defeat clear shortly after polls closed.

To succeed, the yes campaign – advocating for the voice – needed to secure a double majority, meaning it needed both a majority of the national vote, as well majorities in four of Australia’s six states.

The defeat will be seen by Indigenous advocates as a blow to what has been a hard fought struggle to progress reconciliation and recognition in modern Australia, with First Nations people continuing to suffer discrimination, poorer health and economic outcomes.

More than 17 million Australians were enrolled for the compulsory vote, with many expats visiting embassies around the world in the weeks leading up to Saturday’s poll.

The vote occurred 235 years on from British settlement, 61 years after Aboriginal Australians were granted the right to vote, and 15 years since a landmark prime ministerial apology for harm caused by decades of government policies including the forced removal of children from Indigenous families.

The referendum had been a key promise that Labor party took to the federal election in 2022, when it returned to power after years of conservative rule.

Support for the voice to parliament had been strong in the early months of 2023, polling showed, but subsequently began a slow and steady decline.

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

An overwhelming no vote for providing a voice that recognises the indigenous inhabitants of this country who have been around for approximately 65,000 years.

An overwhelming vote for disinformation and bad faith actors, like one particular former star of Neighbours (the Australian soap opera) who’s turned out to be a conspiracy theorist and thought that a ‘yes’ vote would end up with the UN invading the country.

The White Australia policy may be officially over but it’s legacy runs deep.

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Also fuck Albanese. Like I wasn't expecting to hear anything different from an Imperial Core Left Lib (especially the one in charge of a pathetically loyal vassal state of the US) but still it was so fucking infuriating hearing him go on and on about how awful and terrible Hamas was and how we stand with Israel with not even a single mention (not even in an offhanded or downplaying way) of the fucking hideous Israeli atrocities that led to this situation. I'd say that this is a classic case of how Settler states have gotta stick together but as soon as he was done talking about Israel he went on to talk about the importance of this referendum for the Indigenous Voice to Parliament.

And like obviously recognising Indigenous Australians in the constitution and granting them some level of political representation is a good thing. It's not going to change all that much (definitely not undoing the violence at the very core of a settler state like Australia, nor will it make up for the long and ongoing history of both physically, culturally and environmentally genocidal policies or end their terrible poverty and discrimination overnight) but it's not a terrible half-step towards restoring some level of dignity and respect to Australian Aboriginals and possibly easing the path towards future improvements in their material conditions. At the very least it'll force people to recognise the immeasurable rift between the indigenous and the settler populations of this nation which appears to be where so much of the opposition to it is coming from; people from the "Vote No" campaign won't shut up about how this will divide the country but what they really mean is that they don't want to think about the divide that's existed for as long as European settlement.

And like there's something so infuriating to me about a politician calling for tepid reconciliation (although at this point it's arguably just appeasement and concession) with one group of indigenous peoples while essentially condoning the ongoing violence and impoverishment of another. I guess the difference here is that the Australian Aboriginals have to resist colonialism from a much weaker position then the Palestinians do; Australia's policies of dispossession and genocide have been going on for much longer and been much more "successful" than those of Israel. They're currently not a credible threat to state security and so don't have to be taken all that seriously, so certain concessions can be considered and even given without real risk of weakening the settler establishment. The sort of unrelenting violence as displayed by Israel just isn't all that necessary. Not to say that it isn't happening over here, but it's at a lower intensity and scale and many participants in mainstream politics are willing to condemn it and pursue measures to lessen it. Like if this referendum does pass then I'm sure various Left Lib* Aussies will go on and on about how it's a sign of how progressive we all are and how we can all come together and close "old wounds" together. But like I know for sure the Australian political establishment wouldn't be feeling so conciliatory if there was a real risk of Aboriginals mounting their own Intifada

(*as in Liberalism the ideology, which essentially describes all the major parties in Australian and really the rest of the Imperial core)

7 notes

·

View notes

Note

good morning maam, can I please ask why Canadians aren't as notorious as Americans? you did the same things we did to Indians.

I'm not sure how you identify, but unless you're indigenous, 'indians' isn't the term you want to use for indigenous peoples. It's a dated, highly loaded and racist term in most contexts. Not to mention Indian is a nationality outside of North America. It's probably best to be as specific as you can in a local context but even in a broader way, that word is not what you should be using.

Moving on, to preface this, I am a white dual Canadian/American, so this is open to correction, and I will only be giving a very broad overview of my specialty as a librarian and archivist, media bias and information and research accessibility.

So to begin: notorious to who? The rest of the world outside of North America? That's because the US projects more soft power than Canada ever will. It is much the same for Australia, New Zealand or any other settler colony. We're all as fucked up, but it's American media that sets the narrative. And Americans and American politicians get to mouth off. There is a power difference that, for some reason, people like to equate to some uwu-esque quality to Canada, but it's not a reality so much as 'watch your mouth the Americans are twitchy' is. And Canada did its external imperialism in the form of the usual economic leverage in the north or otherwise under a British flag. So there's a certain difference in politeness but not kindness. Add that to the entire world seeing the fucked up things the US does. And you get a country that looks better. Plus, there's this weird thing where American liberals just, give Canadians the weirdest reputation of some sort of northern paradise, and there are key differences Canada does better on, but yeah, most of that 'reputation' has very little to do with Canadian reality as it does American perception.

In Canada, the history of the subjugation and genocide of First Nations peoples is just as well known to Canadians as that against Native Americans in the US, if not more so. As for why other human beings think it was 'better' in Canada or that the US is more 'notorious,' it comes down to rhetoric. Canada much more freely admits to these things, makes a big deal about apologizing and reconciliation, and there's generally more cultural and official acknowledgement. Indigenous issues are more visible in politics in Canada than they are in the US in many ways, but Canada, for the most part, isn't any better in policy. There's a lot of talk about the 'legacy' of imperialism in Canada and not much acknowledgement of the continuing policies in either country. So there might be something to be said about optics being more front-facing, but racism, deprivation, inequality, land theft and all the other facets of genocide are still very much in play in both countries.

If you want further reading, I'm happy to provide it.

#the ask box || probis pateo#research || sauntering through the stacks#history || that which makes us what we are

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

New announcement from OECD

Everyone's like, in wrong path, but not Australia?!

0 notes

Text

Disability Services Provider Ballina

Disability services provider Ballina has opened a new office on River Street in the city. CEO Liz Forsyth was joined by local staff and customers to officially launch the organisation’s Stretch Reconciliation Action Plan to regional staff and customers.

COVID-19 has impacted the way services manage disability residential care and support workers. This has included testing, deploying PPE and quarantine procedures. To know more about Disability Services Provider Ballina, visit the Dabba Mallangyirren website or call 0403856995.

Dabba Mallangyirren is a community based not-for-profit organisation that works for people with disability in the Ballina area. It provides care staff and in-home nurses, as well as advocacy training and support. It also offers a range of workshops and events. In addition, it has strong collaborative networks with Indigenous communities and focuses on improving the lives of Aboriginal Australians.

It also supports local initiatives, including the Little Beach Disabled Access Wharf project. Its Disability Action Plan is aligned with existing Council plans and policies. This ensures efficiency and consistency in service delivery. A survey of Council staff was conducted, and many of the suggestions from this were incorporated into the Disability Action Plan.

Invisible disabilities include a spectrum of hidden challenges that are neurological in nature, such as fetal alcohol syndrome, attention deficit disorders, and pervasive developmental disorders. These conditions are often misdiagnosed or overlooked. Invisible disabilities affect more than 10 percent of the population. Invisible disabilities can also affect the quality of life of individuals and their families.

Dabba Mallangyirren provides world-class services for people living with cerebral palsy and similar conditions. These include family-centred therapies, life skills programs, equipment and accommodation. The organisation also funds important research into prevention, treatment and cure. It is the largest charity of its kind in Australia. It operates from a number of sites across the state and the ACT.

Newcastle Permanent Charitable Foundation supports CPA because of its innovative approach to disability services. Its centres allow families to access leading concepts in therapy that would otherwise only be available in large cities. This means children can maintain or increase their development in the vital early years.

CPA has been helping babies, children, teenagers and adults with cerebral palsy and other disabilities for over 75 years. Its aim is to help them lead comfortable, independent and inclusive lives. The organisation also funds global research into the prevention, treatment and cure of cerebral palsy through its CPA Research Foundation and Disability Technology Accelerator, Remarkable.

Dabba Mallangyirren is a not-for-profit disability service provider that works with customers to realise their potential. Its services are provided from metropolitan and regional locations across NSW and the ACT. It is a registered NDIS provider and employs more than 2000 staff. It provides empowering, personalised services to more than 13,500 people with disabilities and their families each year.

Its origins date back to 1929, when it was known as the New South Wales Society for Crippled Children. It was the founder of Rehabilitation International, which later became Cerebral Palsy Alliance and Muscular Dystrophy Association NSW. It also established the National Rehabilitation Hospital at Killara in 1946.

The organisational structure of Dabba Mallangyirren includes all entities that are wholly owned subsidiaries of the Northcott Society. These subsidiaries share the same corporate functions such as learning and development, finance, HR, payroll, contracts and procurement, fleet, facilities, and IT. To know more about Disability Services Provider Ballina, visit the Dabba Mallangyirren website or call 0403856995.

#aboriginal lismore#disability services lismore#disability lismore#ndis lismore#ndis services#ndis services ballina#disability services#disability services provider ballina#disability services ballina#disability services provider#Disability services#Disability services Ballina#Disability services provider#Disability services provider Ballina

0 notes

Text

This body (voice) already exists. Why a third one and why enshrined in constitution ??

Prime Minister’s Indigenous Advisory Council

The Prime Minister’s Indigenous Advisory Council (the ‘Council’) will provide advice to the Government on Indigenous affairs, and will focus on practical changes to improve the lives of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

– The Council will provide ongoing advice to the Government on emerging policy and implementation issues related to Indigenous affairs including, but not limited to:

– improving school attendance and educational attainment;

– creating lasting employment opportunities in the real economy;

– reviewing land ownership and other drivers of economic development;

– preserving Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultures;

– building reconciliation and creating a new partnership between black and white Australians;

– empowering Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities;

– building the capacity of communities, service providers and governments;

– promoting better evaluation to inform government decision-making;

– supporting greater shared responsibility and reducing dependence on government within indigenous communities; and

– achieving constitutional recognition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

– The Council will engage with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities, including existing Indigenous advocacy bodies, to ensure that the Government has access to a diversity of views. The Council will also engage with other individuals and organisations, as relevant to the Government’s agenda.

– The Government may request the Council to provide advice on specific policy and programme effectiveness, to help ensure that Indigenous programmes achieve real, positive change in the lives of Aboriginal people.

– The Council will report annually to the Government on its activities, via letter to the Prime Minister.

The Council will have up to 12 members, including a Chair and Deputy Chair. Members will be both Indigenous and non-Indigenous. Members will have a strong understanding of Indigenous culture and bring a diversity of expertise in economic development and business acumen, employment, education, youth participation, service delivery and health. The membership will include representation from both the private, public and civil society sectors and be drawn from across Australia, with at least one representative from a remote area.

The Council will meet three times annually with the Prime Minister and relevant senior ministers. The Council will report annually to the Government on its activities, via letter to the Prime Minister.

Secretariat support will be provided by the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet.

Read more articles at:

https://veritywarner90.wordpress.com

0 notes

Photo

New Post has been published on https://www.knewtoday.net/resilience-and-revival-five-stories-of-aboriginal-life-in-australia-after-european-invasion/

Resilience and Revival: Five Stories of Aboriginal Life in Australia After European Invasion

The European invasion of Australia in the late 18th century had a profound and lasting impact on the Aboriginal people, the continent’s original inhabitants. The arrival of European settlers brought significant changes to the social, cultural, and political landscape, leading to a complex and often painful history for Aboriginal communities. However, amidst the challenges and injustices, stories of resilience, cultural revival, and a quest for justice have emerged, painting a picture of a people determined to preserve their heritage and create a better future.

In this collection of stories, we delve into five significant narratives that shed light on the experiences of Aboriginal Australians after the European invasion. These stories highlight both the struggles and the triumphs, offering a glimpse into the diverse ways in which Aboriginal communities have navigated the post-invasion era.

From the heart-wrenching tale of the Stolen Generation, where Aboriginal children were forcibly separated from their families to the inspiring fight for land rights and self-determination, these stories encapsulate the profound impact of European colonization on the Aboriginal people and their ongoing efforts to reclaim their cultural identity.

We will also explore the pivotal moment of reconciliation and apology, as the Australian government acknowledged the injustices of the past, offering hope for healing and unity. Additionally, we will delve into the resurgence of Aboriginal art and cultural expression, as Indigenous artists reclaim their narratives and share their rich heritage with the world.

Lastly, we will uncover the remarkable stories of Aboriginal land and sea management practices, where traditional ecological knowledge blends with modern conservation principles, creating sustainable ecosystems and economic opportunities for Aboriginal communities.

These stories weave together a narrative of strength, resilience, and determination among Aboriginal Australians. They provide a deeper understanding of the ongoing journey toward justice, reconciliation, and the revitalization of Aboriginal culture. Through these tales, we are reminded of the importance of acknowledging and respecting the legacy of the Aboriginal people and working towards a more inclusive and harmonious future.

The Stolen Generation

The Stolen Generation refers to a dark chapter in Australian history when Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children were forcibly removed from their families by the Australian government and placed into institutions or with non-Indigenous foster families. This policy, which spanned from the late 1800s to the 1970s, aimed to assimilate Indigenous children into Western culture, severing their ties to their families, culture, and land.

The impact of the Stolen Generation on individuals and communities was profound and long-lasting. Children were taken away without consent or understanding, often experiencing trauma, loss of cultural identity, and a sense of displacement. Families were torn apart, and the bonds of kinship and community were shattered. The effects of this policy continue to be felt today, with intergenerational trauma and ongoing struggles for healing and reconciliation.

One example that highlights the experiences of the Stolen Generation is the story of Doris Pilkington Garimara, as depicted in her book “Follow the Rabbit-Proof Fence” (later adapted into a film). Doris, along with her sister and cousin, was forcibly taken from her mother in 1931 when she was just four years old. They were transported to Moore River Native Settlement, hundreds of miles away from their home.

Determined to return to their family and their traditional lands, the three girls embarked on a remarkable journey, following the Rabbit-Proof Fence that stretched across the Western Australian outback. Despite the challenging conditions and the constant threat of capture, they relied on their knowledge of the land and their resilience to navigate their way home.

Doris Pilkington Garimara’s story, along with countless others, sheds light on the courage, strength, and resilience of the Stolen Generation. It serves as a testament to their enduring connection to their culture and their unyielding spirit in the face of adversity.

The recognition of the Stolen Generation and the injustices they suffered led to a national apology by then Prime Minister Kevin Rudd in 2008. The apology aimed to acknowledge the pain and suffering caused by the forced removals and to begin the process of healing and reconciliation between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians.

The stories of individuals like Doris Pilkington Garimara and the countless others impacted by the Stolen Generation serve as a reminder of the ongoing need for understanding, compassion, and support for healing the wounds inflicted upon Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities. It is through listening, acknowledging, and learning from these stories that a path toward reconciliation and justice can be forged.

Land Rights Movement

The Land Rights Movement in Australia emerged as a response to the dispossession and marginalization of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples from their traditional lands following the European invasion. It sought to address the historical injustices, assert Indigenous rights to land, and regain control over their ancestral territories. The movement gained momentum in the 1960s and 1970s, and its efforts have resulted in significant legal and social changes.

One prominent example of the Land Rights Movement is the Gurindji strike and the subsequent Wave Hill Walk-Off in 1966. Led by Vincent Lingiari, the Gurindji people, were working as cattle station laborers in Wave Hill, Northern Territory, demanding better working conditions and the return of their traditional lands.

The Wave Hill Walk-Off was a groundbreaking event that captured national attention. More than 200 Aboriginal workers, together with their families, left the Wave Hill cattle station, camping at Daguragu (formerly known as Wattie Creek) and refusing to work until their demands were met. Their actions sparked a larger movement for land rights and provided a rallying point for Aboriginal activism across the country.

The Gurindji strike and the Wave Hill Walk-Off led to the establishment of the Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act 1976. This legislation recognized Aboriginal land rights in the Northern Territory and paved the way for the return of land to Indigenous ownership. It was a significant milestone in the Land Rights Movement, empowering Aboriginal communities and enabling them to reclaim their ancestral lands.

Another significant example is the Native Title Act of 1993. This legislation recognized the existence of native title, the recognition of Indigenous land rights based on traditional connections to the land, and established a legal framework for Indigenous communities to make native title claims. The Native Title Act aimed to address the historical injustices and provide a pathway for land rights reconciliation.

The Mabo v Queensland (No 2) case, a landmark High Court decision in 1992, played a pivotal role in the recognition of native title. Eddie Mabo, along with other Torres Strait Islander and Aboriginal plaintiffs, challenged the doctrine of terra nullius (the notion that Australia was unoccupied prior to European settlement) and successfully argued for the recognition of native title rights.

These examples highlight the activism, perseverance, and collective efforts of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in their fight for land rights. The Land Rights Movement has led to the return of significant areas of land to Indigenous ownership, enabling communities to reconnect with their traditional lands, practice cultural traditions, and exercise self-determination.

The struggle for land rights is ongoing, and Indigenous communities continue to assert their rights and negotiate for recognition and control over their lands. The Land Rights Movement remains a critical aspect of the broader movement for Indigenous rights, self-determination, and reconciliation in Australia.

Reconciliation and the Apology

Reconciliation and the Apology refer to significant steps taken in Australia to acknowledge and address the historical injustices and mistreatment of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples following the European invasion. These initiatives aim to foster healing, understanding, and a path toward unity between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians.

Reconciliation: Reconciliation in Australia involves acknowledging the past injustices, promoting understanding, and working towards a more respectful and equitable future for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. The concept emphasizes the importance of building positive relationships, respecting Indigenous cultures and heritage, and addressing the ongoing issues faced by Indigenous communities.

The journey toward reconciliation encompasses various aspects, including education, awareness, community engagement, and policy changes. It involves acknowledging and respecting the diverse cultures, languages, and histories of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, as well as supporting self-determination and empowering Indigenous communities.

Apology: The Apology refers to the formal apology delivered by then Prime Minister Kevin Rudd on behalf of the Australian government to the Stolen Generations on February 13, 2008. The Stolen Generations were the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children who were forcibly removed from their families and communities under government policies of assimilation.

In his speech, Rudd acknowledged the pain, trauma, and injustices suffered by the Stolen Generations and their families. The Apology sought to provide recognition, validation, and healing, aiming to restore dignity and respect to those who had endured the devastating impacts of forced removal.

The Apology represented a significant moment in Australian history, symbolizing a national commitment to acknowledging past wrongs and working towards reconciliation. It sparked hope for a renewed relationship between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians, promoting understanding, healing, and a shared future.

Following the Apology, various initiatives and programs have been implemented to support reconciliation efforts, including increased funding for Indigenous education, health services, and community development. National Reconciliation Week, held annually from May 27 to June 3, provides an opportunity for Australians to reflect on the importance of reconciliation and to participate in events that promote understanding and unity.

Reconciliation and the Apology are ongoing processes, requiring continued commitment, understanding, and meaningful actions from all Australians. The goal is to create a more inclusive, just, and equitable society where Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples can thrive, celebrate their cultures, and contribute to the nation as equal partners.

These initiatives mark important milestones in Australia’s journey towards healing, recognition, and forging stronger relationships between Indigenous and non-Indigenous communities. They represent a commitment to learning from the past, acknowledging the ongoing impacts of colonization, and working towards a shared future of reconciliation and justice.

Land and Sea Management

Land and Sea Management in Australia refers to the Indigenous-led practices and initiatives aimed at preserving and sustainably managing the natural environment, including land, waterways, and marine ecosystems. These practices combine traditional ecological knowledge with modern conservation principles to ensure the long-term sustainability of ecosystems while supporting Indigenous cultural connections to the land and sea.

Indigenous land and sea management initiatives recognize the deep understanding and stewardship of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, who have maintained sustainable relationships with the environment for thousands of years. These initiatives encompass various activities, such as fire management, cultural mapping, species monitoring, habitat restoration, and sustainable fishing practices.

One notable example of Indigenous land and sea management is the work of the Yolngu people in Arnhem Land, Northern Territory. Through their organization, the Dhimurru Aboriginal Corporation, the Yolngu people have been actively involved in caring for their ancestral lands and coastal areas.

Dhimurru’s initiatives include fire management practices, where controlled burning is utilized to maintain healthy ecosystems, reduce the risk of wildfires, and promote the regeneration of native plants and animals. The Yolngu people also engage in sea management, monitoring and protecting marine species, and implementing sustainable fishing practices to ensure the preservation of coastal resources.

Another example is the Djelk Rangers program in West Arnhem Land. The program, established by the traditional owners of the region, involves Indigenous rangers working to conserve and manage the land, rivers, and coastal areas. The Djelk Rangers are involved in activities such as weed and pest management, cultural site protection, and land and waterway monitoring. They also collaborate with scientists and researchers to combine traditional knowledge with scientific approaches, fostering a holistic approach to land and sea management.

Indigenous land and sea management practices not only contribute to biodiversity conservation but also support cultural preservation, economic development, and community empowerment. These initiatives provide employment and training opportunities for Indigenous communities, enabling them to reconnect with their cultural heritage, pass on traditional knowledge to future generations, and assert their rights and responsibilities as custodians of the land and sea.

The success of Indigenous land and sea management programs has led to increased recognition and support from government, non-governmental organizations, and the broader community. Collaborative partnerships have been formed, enabling Indigenous communities to have a greater say in land management decisions and policies.

Overall, Indigenous land and sea management initiatives exemplify the intersection of environmental conservation, cultural preservation, and community development. These practices demonstrate the importance of traditional ecological knowledge and the role of Indigenous communities as custodians of the land and sea, leading to more sustainable and inclusive approaches to environmental stewardship.

Aboriginal Art and Cultural Revival

Aboriginal Art and Cultural Revival in Australia has played a vital role in preserving and celebrating Indigenous traditions, stories, and cultural heritage. Aboriginal art encompasses a wide range of artistic expressions, including paintings, sculptures, carvings, weaving, and more. It is deeply rooted in the spiritual and cultural beliefs of Aboriginal communities and serves as a powerful medium for storytelling and connection to the land.

Aboriginal art has gained international recognition for its unique styles, vibrant colors, and intricate designs. It provides a visual representation of the rich cultural diversity and deep connection to Country held by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

One example of Aboriginal art and cultural revival is the Western Desert Art Movement. It emerged in the 1970s in remote communities of Central Australia, such as Papunya, and is often credited as the catalyst for the contemporary Aboriginal art movement. Artists like Clifford Possum Tjapaltjarri and Emily Kame Kngwarreye played significant roles in popularizing Aboriginal art and introducing it to a broader audience.

The Western Desert Art Movement revitalized traditional art practices and storytelling techniques, leading to the establishment of art centers in Aboriginal communities. These art centers provide a space for artists to create and share their work, ensuring cultural knowledge is passed down to future generations.

Contemporary Aboriginal artists draw inspiration from Dreamtime stories, ancestral connections, and the natural environment. They employ a diverse range of styles and techniques, ranging from dot paintings to intricate cross-hatching and more abstract forms. Each artwork holds deep cultural significance and often carries messages related to identity, land rights, spirituality, and social issues.

The success and recognition of Aboriginal art have also brought economic opportunities to Indigenous communities. Art sales, exhibitions, and licensing agreements provide a sustainable income source for artists and their communities, fostering self-determination and empowering Aboriginal individuals and art centers.

In recent years, Aboriginal art has been increasingly incorporated into public spaces, galleries, and museums, both in Australia and internationally. It serves as a means of education, raising awareness about Aboriginal culture and history, and challenging stereotypes and misconceptions.

The cultural revival facilitated by Aboriginal art extends beyond visual representations. It has influenced other creative disciplines, including music, dance, storytelling, and film, contributing to a broader renaissance of Indigenous cultural practices and expressions.

Aboriginal art and cultural revival not only provide a platform for Indigenous voices and narratives but also contribute to a deeper understanding and appreciation of Australia’s rich cultural tapestry. They serve as a testament to the resilience and ongoing presence of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, and their commitment to preserving and sharing their cultural heritage with the world.

#Aboriginal Art#Aboriginal History#Cultural Revival#European Invasion#Indigenous Knowledge#Land Rights Movement#Reconciliation#Stolen Generation

0 notes

Text

The European invasion of Australia in the late 18th century had a profound and lasting impact on the Aboriginal people, the continent's original inhabitants. The arrival of European settlers brought significant changes to the social, cultural, and political landscape, leading to a complex and often painful history for Aboriginal communities. However, amidst the challenges and injustices, stories of resilience, cultural revival, and a quest for justice have emerged, painting a picture of a people determined to preserve their heritage and create a better future.

In this collection of stories, we delve into five significant narratives that shed light on the experiences of Aboriginal Australians after the European invasion. These stories highlight both the struggles and the triumphs, offering a glimpse into the diverse ways in which Aboriginal communities have navigated the post-invasion era.

From the heart-wrenching tale of the Stolen Generation, where Aboriginal children were forcibly separated from their families to the inspiring fight for land rights and self-determination, these stories encapsulate the profound impact of European colonization on the Aboriginal people and their ongoing efforts to reclaim their cultural identity.

We will also explore the pivotal moment of reconciliation and apology, as the Australian government acknowledged the injustices of the past, offering hope for healing and unity. Additionally, we will delve into the resurgence of Aboriginal art and cultural expression, as Indigenous artists reclaim their narratives and share their rich heritage with the world.

Lastly, we will uncover the remarkable stories of Aboriginal land and sea management practices, where traditional ecological knowledge blends with modern conservation principles, creating sustainable ecosystems and economic opportunities for Aboriginal communities.

These stories weave together a narrative of strength, resilience, and determination among Aboriginal Australians. They provide a deeper understanding of the ongoing journey toward justice, reconciliation, and the revitalization of Aboriginal culture. Through these tales, we are reminded of the importance of acknowledging and respecting the legacy of the Aboriginal people and working towards a more inclusive and harmonious future.

The Stolen Generation

The Stolen Generation refers to a dark chapter in Australian history when Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children were forcibly removed from their families by the Australian government and placed into institutions or with non-Indigenous foster families. This policy, which spanned from the late 1800s to the 1970s, aimed to assimilate Indigenous children into Western culture, severing their ties to their families, culture, and land.

The impact of the Stolen Generation on individuals and communities was profound and long-lasting. Children were taken away without consent or understanding, often experiencing trauma, loss of cultural identity, and a sense of displacement. Families were torn apart, and the bonds of kinship and community were shattered. The effects of this policy continue to be felt today, with intergenerational trauma and ongoing struggles for healing and reconciliation.

One example that highlights the experiences of the Stolen Generation is the story of Doris Pilkington Garimara, as depicted in her book "Follow the Rabbit-Proof Fence" (later adapted into a film). Doris, along with her sister and cousin, was forcibly taken from her mother in 1931 when she was just four years old. They were transported to Moore River Native Settlement, hundreds of miles away from their home.

Determined to return to their family and their traditional lands, the three girls embarked on a remarkable journey, following the Rabbit-Proof Fence that stretched across the Western Australian outback. Despite the challenging conditions and the constant threat of capture, they relied on their knowledge of the land and their resilience to navigate their way home.

Doris Pilkington Garimara's story, along with countless others, sheds light on the courage, strength, and resilience of the Stolen Generation. It serves as a testament to their enduring connection to their culture and their unyielding spirit in the face of adversity.

The recognition of the Stolen Generation and the injustices they suffered led to a national apology by then Prime Minister Kevin Rudd in 2008. The apology aimed to acknowledge the pain and suffering caused by the forced removals and to begin the process of healing and reconciliation between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians.

The stories of individuals like Doris Pilkington Garimara and the countless others impacted by the Stolen Generation serve as a reminder of the ongoing need for understanding, compassion, and support for healing the wounds inflicted upon Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities. It is through listening, acknowledging, and learning from these stories that a path toward reconciliation and justice can be forged.

Land Rights Movement

The Land Rights Movement in Australia emerged as a response to the dispossession and marginalization of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples from their traditional lands following the European invasion. It sought to address the historical injustices, assert Indigenous rights to land, and regain control over their ancestral territories. The movement gained momentum in the 1960s and 1970s, and its efforts have resulted in significant legal and social changes.

One prominent example of the Land Rights Movement is the Gurindji strike and the subsequent Wave Hill Walk-Off in 1966. Led by Vincent Lingiari, the Gurindji people, were working as cattle station laborers in Wave Hill, Northern Territory, demanding better working conditions and the return of their traditional lands.

The Wave Hill Walk-Off was a groundbreaking event that captured national attention. More than 200 Aboriginal workers, together with their families, left the Wave Hill cattle station, camping at Daguragu (formerly known as Wattie Creek) and refusing to work until their demands were met. Their actions sparked a larger movement for land rights and provided a rallying point for Aboriginal activism across the country.

The Gurindji strike and the Wave Hill Walk-Off led to the establishment of the Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act 1976. This legislation recognized Aboriginal land rights in the Northern Territory and paved the way for the return of land to Indigenous ownership. It was a significant milestone in the Land Rights Movement, empowering Aboriginal communities and enabling them to reclaim their ancestral lands.

Another significant example is the Native Title Act of 1993. This legislation recognized the existence of native title, the recognition of Indigenous land rights based on traditional connections to the land, and established a legal framework for Indigenous communities to make native title claims. The Native Title Act aimed to address the historical injustices and provide a pathway for land rights reconciliation.

The Mabo v Queensland (No 2) case, a landmark High Court decision in 1992, played a pivotal role in the recognition of native title. Eddie Mabo, along with other Torres Strait Islander and Aboriginal plaintiffs, challenged the doctrine of terra nullius (the notion that Australia was unoccupied prior to European settlement) and successfully argued for the recognition of native title rights.

These examples highlight the activism, perseverance, and collective efforts of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in their fight for land rights. The Land Rights Movement has led to the return of significant areas of land to Indigenous ownership, enabling communities to reconnect with their traditional lands, practice cultural traditions, and exercise self-determination.

The struggle for land rights is ongoing, and Indigenous communities continue to assert their rights and negotiate for recognition and control over their lands.

The Land Rights Movement remains a critical aspect of the broader movement for Indigenous rights, self-determination, and reconciliation in Australia.

Reconciliation and the Apology

Reconciliation and the Apology refer to significant steps taken in Australia to acknowledge and address the historical injustices and mistreatment of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples following the European invasion. These initiatives aim to foster healing, understanding, and a path toward unity between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians.

Reconciliation: Reconciliation in Australia involves acknowledging the past injustices, promoting understanding, and working towards a more respectful and equitable future for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. The concept emphasizes the importance of building positive relationships, respecting Indigenous cultures and heritage, and addressing the ongoing issues faced by Indigenous communities.

The journey toward reconciliation encompasses various aspects, including education, awareness, community engagement, and policy changes. It involves acknowledging and respecting the diverse cultures, languages, and histories of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, as well as supporting self-determination and empowering Indigenous communities.

Apology: The Apology refers to the formal apology delivered by then Prime Minister Kevin Rudd on behalf of the Australian government to the Stolen Generations on February 13, 2008. The Stolen Generations were the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children who were forcibly removed from their families and communities under government policies of assimilation.

In his speech, Rudd acknowledged the pain, trauma, and injustices suffered by the Stolen Generations and their families. The Apology sought to provide recognition, validation, and healing, aiming to restore dignity and respect to those who had endured the devastating impacts of forced removal.

The Apology represented a significant moment in Australian history, symbolizing a national commitment to acknowledging past wrongs and working towards reconciliation. It sparked hope for a renewed relationship between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians, promoting understanding, healing, and a shared future.

Following the Apology, various initiatives and programs have been implemented to support reconciliation efforts, including increased funding for Indigenous education, health services, and community development. National Reconciliation Week, held annually from May 27 to June 3, provides an opportunity for Australians to reflect on the importance of reconciliation and to participate in events that promote understanding and unity.

Reconciliation and the Apology are ongoing processes, requiring continued commitment, understanding, and meaningful actions from all Australians. The goal is to create a more inclusive, just, and equitable society where Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples can thrive, celebrate their cultures, and contribute to the nation as equal partners.

These initiatives mark important milestones in Australia's journey towards healing, recognition, and forging stronger relationships between Indigenous and non-Indigenous communities. They represent a commitment to learning from the past, acknowledging the ongoing impacts of colonization, and working towards a shared future of reconciliation and justice.

Land and Sea Management

Land and Sea Management in Australia refers to the Indigenous-led practices and initiatives aimed at preserving and sustainably managing the natural environment, including land, waterways, and marine ecosystems. These practices combine traditional ecological knowledge with modern conservation principles to ensure the long-term sustainability of ecosystems while supporting Indigenous cultural connections to the land and sea.

Indigenous land and sea management initiatives recognize the deep understanding and stewardship

of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, who have maintained sustainable relationships with the environment for thousands of years. These initiatives encompass various activities, such as fire management, cultural mapping, species monitoring, habitat restoration, and sustainable fishing practices.

One notable example of Indigenous land and sea management is the work of the Yolngu people in Arnhem Land, Northern Territory. Through their organization, the Dhimurru Aboriginal Corporation, the Yolngu people have been actively involved in caring for their ancestral lands and coastal areas.

Dhimurru's initiatives include fire management practices, where controlled burning is utilized to maintain healthy ecosystems, reduce the risk of wildfires, and promote the regeneration of native plants and animals. The Yolngu people also engage in sea management, monitoring and protecting marine species, and implementing sustainable fishing practices to ensure the preservation of coastal resources.

Another example is the Djelk Rangers program in West Arnhem Land. The program, established by the traditional owners of the region, involves Indigenous rangers working to conserve and manage the land, rivers, and coastal areas. The Djelk Rangers are involved in activities such as weed and pest management, cultural site protection, and land and waterway monitoring. They also collaborate with scientists and researchers to combine traditional knowledge with scientific approaches, fostering a holistic approach to land and sea management.

Indigenous land and sea management practices not only contribute to biodiversity conservation but also support cultural preservation, economic development, and community empowerment. These initiatives provide employment and training opportunities for Indigenous communities, enabling them to reconnect with their cultural heritage, pass on traditional knowledge to future generations, and assert their rights and responsibilities as custodians of the land and sea.

The success of Indigenous land and sea management programs has led to increased recognition and support from government, non-governmental organizations, and the broader community. Collaborative partnerships have been formed, enabling Indigenous communities to have a greater say in land management decisions and policies.

Overall, Indigenous land and sea management initiatives exemplify the intersection of environmental conservation, cultural preservation, and community development. These practices demonstrate the importance of traditional ecological knowledge and the role of Indigenous communities as custodians of the land and sea, leading to more sustainable and inclusive approaches to environmental stewardship.

Aboriginal Art and Cultural Revival

Aboriginal Art and Cultural Revival in Australia has played a vital role in preserving and celebrating Indigenous traditions, stories, and cultural heritage. Aboriginal art encompasses a wide range of artistic expressions, including paintings, sculptures, carvings, weaving, and more. It is deeply rooted in the spiritual and cultural beliefs of Aboriginal communities and serves as a powerful medium for storytelling and connection to the land.

Aboriginal art has gained international recognition for its unique styles, vibrant colors, and intricate designs. It provides a visual representation of the rich cultural diversity and deep connection to Country held by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

One example of Aboriginal art and cultural revival is the Western Desert Art Movement. It emerged in the 1970s in remote communities of Central Australia, such as Papunya, and is often credited as the catalyst for the contemporary Aboriginal art movement. Artists like Clifford Possum Tjapaltjarri and Emily Kame Kngwarreye played significant roles in popularizing Aboriginal art and introducing it to a broader audience.

The Western Desert Art Movement revitalized traditional art practices

and storytelling techniques, leading to the establishment of art centers in Aboriginal communities. These art centers provide a space for artists to create and share their work, ensuring cultural knowledge is passed down to future generations.

Contemporary Aboriginal artists draw inspiration from Dreamtime stories, ancestral connections, and the natural environment. They employ a diverse range of styles and techniques, ranging from dot paintings to intricate cross-hatching and more abstract forms. Each artwork holds deep cultural significance and often carries messages related to identity, land rights, spirituality, and social issues.

The success and recognition of Aboriginal art have also brought economic opportunities to Indigenous communities. Art sales, exhibitions, and licensing agreements provide a sustainable income source for artists and their communities, fostering self-determination and empowering Aboriginal individuals and art centers.

In recent years, Aboriginal art has been increasingly incorporated into public spaces, galleries, and museums, both in Australia and internationally. It serves as a means of education, raising awareness about Aboriginal culture and history, and challenging stereotypes and misconceptions.

The cultural revival facilitated by Aboriginal art extends beyond visual representations. It has influenced other creative disciplines, including music, dance, storytelling, and film, contributing to a broader renaissance of Indigenous cultural practices and expressions.

Aboriginal art and cultural revival not only provide a platform for Indigenous voices and narratives but also contribute to a deeper understanding and appreciation of Australia's rich cultural tapestry. They serve as a testament to the resilience and ongoing presence of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, and their commitment to preserving and sharing their cultural heritage with the world.

0 notes

Text

Xeros D&I commitment and support of the Indigenous Voice to Parliament in Australia

Xero’s D&I commitment and support of the Indigenous Voice to Parliament in Australia

https://www.xero.com/blog/2023/07/xeros-support-of-indigenous-voice-to-parliament/

Xero’s commitment to diversity and inclusion (D&I) across our global business extends to championing D&I in the communities in which we operate, including Indigenous communities globally. We believe driving better D&I outcomes can help amplify our positive impact on the world. This commitment aligns with our values and our purpose to make life better for people in small business, their advisors and communities around the world.

Listening and understanding is the first step to enabling meaningful change and positive community outcomes. There are already many ways in which Xero supports Indigenous communities globally such as appointing our first Global Indigenous Affairs Officer, introducing a Social Procurement Plan to preference spend on businesses majority owned or managed by under-represented groups, including First Nations people, and a scholarship for Indigenous students with the Southern Alberta Institute of Technology in Canada.

In Australia, Xero’s soon to be released Reconciliation Action Plan (RAP) will reflect our commitment to reconciliation with First Nations peoples, and the passion and efforts of our employees to foster a structured approach to reconciliation. In line with this, Xero supports the establishment of a Voice to Parliament in Australia to enable First Nations peoples to have a say in policies and decisions that affect them and their communities, and to help close the gap. This position aligns with Xero’s D&I strategy, our values and our purpose, and our reconciliation commitment, as outlined in our RAP.

While this is Xero’s position, we recognise some stakeholders will hold alternate views. We encourage our people, partners and communities to have respectful and inclusive conversations as they seek to help inform their own personal decisions. Additionally, we are committed to playing a role in providing our people with access to education and resources to help inform their own personal decisions on how they choose to vote at the referendum.

The post Xero’s D&I commitment and support of the Indigenous Voice to Parliament in Australia appeared first on Xero Blog.

via Xero Blog https://www.xero.com/blog

July 19, 2023 at 11:00PM

0 notes

Text

when did the peak of reconciliation Between First Nations People and non-indigenous Australians occur?

The 1910-1970 Australian policy not only discriminated against but also destroyed First Nations people’s families and culture, while this policy is no longer valid, there is still a deep disconnection between first nations people and non-indigenous Australians (Bretherton, & Mellor, D. 2006). While the trust between First Nations People and Non-Indigenous Australians is still not 100% it has certainly become stronger, for example, in the upcoming 2023 referendum on ‘the voice’, (Mark Moore, Australian Broadcasting Corporation, 2023, March 23) a bill introduced based on if there should be an Aboriginal spokesperson in parliament to speak on behalf of most or all First Nations people. This will be a crucial point in the reconciliation of First Nations People and Non-indigenous Australians as it will show whether Non-indigenous Australians feel as though First Nations People should be a part of the constitution and have a right to a voice when it is concerning their land and their communities (Mark Moore, Australian Broadcasting Corporation, 2023, March 23). While in 2023 were heading toward an incredible mile stoner 23 years ago in 2000, the Olympic Games were held in Sydney, Australia, (Bretherton, & Mellor, D. 2006), in the opening ceremony there was a moment where First Nations people and Non-indigenous Australians found a place of reconciliation. A white woman, acknowledging and respecting an elder during the ceremony and dreamtime being a major part of this ceremony, was shown to be an incredibly connecting moment for non-indigenous and Indigenous Australians (Bretherton, & Mellor, D. 2006).

0 notes

Text

Liberal Party Plays Politics With Aboriginal Voice & Reconciliation

The Liberal Party under the leadership of Peter Dutton has moved further right into irrelevance in Australia. This is the party that has played politics over climate change for the last 15 years and bogged Australia into the slow lane on this existential crisis facing humanity. Now, the Liberal Party plays politics with Aboriginal Voice and reconciliation. It is a dreadful shame that our nation cannot move forward on something so important united on the political front. The Coalition parties, Nationals and Liberals, were never going to get on board this momentous recognition of our Indigenous brothers and sisters, as they represent the hard right racist minority within Australia.

Peter Dutton & Liberals Play Politics At The Expense Of Our Unified Voice

Peter Dutton has sought to deflect and create confusion over the wording of the question put to the Australian people in the referendum about an Aboriginal voice to parliament. If he and the Liberal Party had a real desire to see a constitutional voice to our federal government by our Indigenous Australians they would have got on board with what has broad support in our national population. The Liberals would rather play politics, despite having had the previous 10 years in government to have done something about this.

vectors icon at Pexels

Coalition In Opposition Throws Away Any Moral Leadership

The Coalition parties could have shown leadership on such an important national shift toward recognition and reconciliation. They could have said, we had a decade in power and were clearly voted out of office on issues like the Voice and climate change, so let us get on board in a spirit of national coming together on a moral question. Aboriginal people have been disenfranchised over centuries from empowerment and the economic wealth of the nation. They suffer from neglect and injustice on virtually every determinant of health, wealth and wellbeing within Australia.

The Voice is about giving Indigenous Australians a say over their own futures and pathways. It is not going to threaten the decision making process at its core, rather it is going to enhance its effectiveness when it comes to designing and enacting the policies for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders. It will ultimately improve things because local Aboriginal people will have a voice about what happens for their people in their towns and regions. Australia needs to stop looking for problems and open up to sharing some modicum of power for our Indigenous Australians in regard to their own fates.

The Liberal Party would rather play politics than put their shoulder to the wheel moving forward to a better and more united Australia. Liberal Party plays politics with Aboriginal Voice and reconciliation to dance with the hard right, racist minority within Australia.

©WordsForWeb

Read the full article

#Aboriginal#Australia#IndigenousAustralians#moralfailure#politics#referendum#Voice#voicetoparliament

0 notes