#JimmyDeSanaBkM

Photo

That Sunday feeling. 😶🌫️🧼

Many of the photographs in Jimmy DeSana’s “Suburban” series explore themes of domestic confinement and social conformity through consumer goods and rituals.

In “Sink (1979)”, shown here, an anonymous figure wearing a corset and heels leans over, head dunked in a kitchen sink filled with soap suds. DeSana allows contradictions—between agency and conformity, critique and complicity, punishment and pleasure—to remain open-ended in his work, enabling them to identify and “disidentify” with dominant culture.

📷 Jimmy DeSana (American, 1949–1990). Sink, 1979. Silver dye bleach print, 19 × 12 5/8 in. (48.3 × 32.1 cm). Courtesy of the Jimmy DeSana Trust and P·P·O·W Gallery, New York. © Estate of Jimmy DeSana. (Photo: Courtesy of the Jimmy DeSana Trust and P·P·O·W Gallery, New York)

#Brooklyn Museum#brooklyn#museum#photography#exhibition#art#photograph#Jimmy DeSana#JimmyDeSanaBkM#New York City#nyc

84 notes

·

View notes

Photo

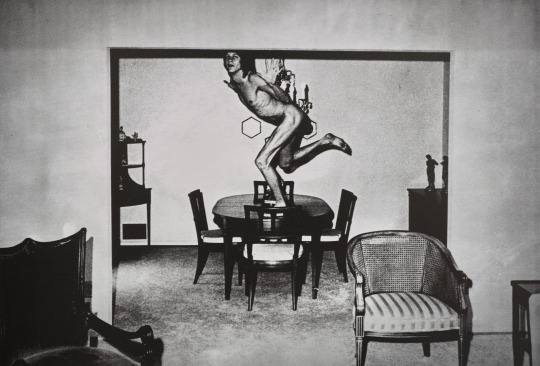

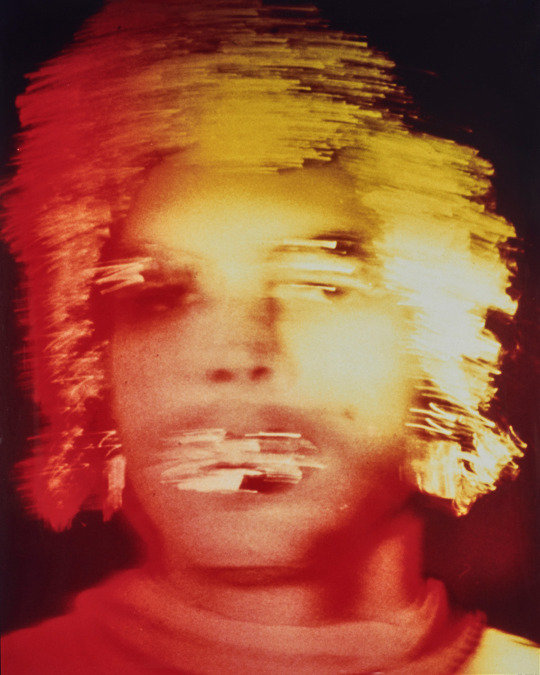

Jimmy DeSana indulged in tongue-in-cheek humor and riffed on historical avant-gardes.

In 1984, DeSana’s spleen ruptured, resulting in a life-changing surgery and his diagnosis with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). While his health deteriorated over the next six years living with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), this period was one of his most productive.

His movement into abstraction—in works that nonetheless address his experience living with HIV/AIDS—countered the objectification of queer bodies in voyeuristic epidemic-related art and news campaigns. It also resisted polarized debates over sexuality and its representations. DeSana embraced opacity and ambiguity in response to binary thinking, and infused mainstream and historic content with a queer perspective.

View the nearly 200 works from this prolific artist in Jimmy DeSana: Submission during the final weekend of the exhibition.

📷 Jimmy DeSana (American, 1949–1990). Aluminum Foil #4 (Self-Portrait), 1985. Silver dye bleach print, 10 × 8 in. (25.4 × 20.3 cm). Courtesy of the Jimmy DeSana Trust and P·P·O·W Gallery, New York. © Estate of Jimmy DeSana. (Photo: Courtesy of the Jimmy DeSana Trust and P·P·O·W Gallery, New York)

#Brooklyn Museum#JimmyDeSanaBkM#Jimmy DeSana#exhibition#art#museum#photography#photographer#artist#HIV#hiv/aids#aids epidemic#lgbtq+#New York City#nyc#sexuality

48 notes

·

View notes

Photo

In his series of photographs titled Suburban, Jimmy DeSana continued to photograph anonymous nude figures while making a more explicit connection between S-M and everyday life.

Many of the photographs comically equate attachments to the objects and ideals of postwar suburban life in the U.S. (washing dishes, taking a shower, driving a car) with forms of bondage and discipline. In Cardboard, from 1985 (shown here), a nude figure is intersected by sheets of cardboard.

Lit with tungsten lights and candy-colored gels, his collaborators often turned their backs to the camera or buried their heads in purses, sinks, toilets, etc. rather than wearing leather masks. This not only protected the identity of his nude models, many of whom were friends, but also contrasted with his better-known portrait work during this period. Perhaps most important, these images continued his subversion of subjectivity. While all the photographs in the Suburban series feature nude figures, DeSana did not intend for the work to be erotic.

📷 Jimmy DeSana (American, 1949–1990). Cardboard, 1985. Silver dye bleach print, 19 × 12 3/4 in. (48.3 × 32.4 cm). Courtesy of the Jimmy DeSana Trust and P·P·O·W Gallery, New York. © Estate of Jimmy DeSana. (Photo: Courtesy of the Jimmy DeSana Trust and P·P·O·W Gallery, New York)

#Brooklyn Museum#brooklyn#museum#art#exhibition#photography#Jimmy DeSana#JimmyDeSanaBkM#artist#New York City#nyc

116 notes

·

View notes

Photo

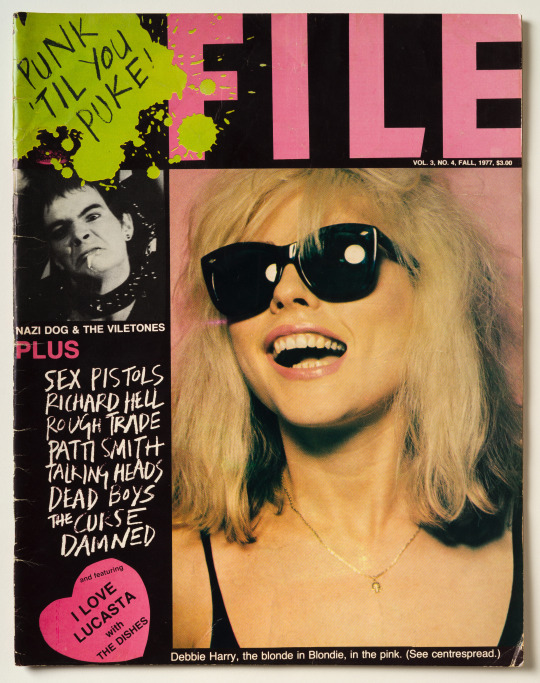

In the second half of the 1970s, Jimmy DeSana chronicled and helped canonize early aspects of what would become known as the New Wave and No Wave scenes in New York and beyond.

He coedited the Fall 1977 issue of File magazine with his friends Diego Cortez and Anya Phillips. Together with the Toronto-based collective General Idea, who published the artist magazine, they evoked and poked fun at the do-it-yourself aesthetic of punk through their writing, photographs, and graphic design.

DeSana produced many of the photographs that appear in the issue, including portraits of musical acts Blondie, Richard Hell, Mars, the Talking Heads, and Teenage Jesus and the Jerks. Rather than attempting to capture likenesses, DeSana intentionally obscured or transformed his sitters’ appearances through lighting and exaggerated posing. Like emerging cultural theories at the time, DeSana’s photographs called attention to the artificiality of the image and the performance of identity. #JimmyDeSanaBkM

📷 General Idea, FILE Megazine, Vol. 3 No. 4, Fall 1977. Courtesy of Philip Aarons and Shelley Fox Aarons. © Reprinted with permission of General Idea. (Photo: David Vu)

#Brooklyn Museum#brooklyn#museum#art#exhibition#Jimmy DeSana#Blondie#magazine#Debbie Harry#JimmyDeSanaBkM#photography#nyc#punk#New York City#File Magazine#new wave#no wave

118 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Throughout the 1970s, Jimmy DeSana created campy portraits of his extended circle of friends and collaborators in New York, which included musicians, filmmakers, writers, artists, critics, and curators.

Performance artist and fixture of New York City’s downtown scene Stephen Varble, shown here, was one of DeSana’s repeat subjects. DeSana captured many of the performances staged by Varble whose guerilla practices served as commentary on gender identity, class, and capitalism. These performance-based and ephemeral events would continue to inform DeSana’s work in photography throughout the 1970s and 1980s.

📷 Jimmy DeSana (American, 1949–1990). Stephen Varble, 1975. Gelatin silver print, printed later. Courtesy of the Jimmy DeSana Trust and P·P·O·W Gallery, New York. © Estate of Jimmy DeSana. (Photo: Allen Phillips)

#Brooklyn Museum#brooklyn#museum#art#exhibition#photography#JimmyDeSanaBkM#Jimmy DeSana#Stephen Varble#New York City#nyc#1970s#artist#photographer#lgbtq+#gender#identity#class#capitalism

60 notes

·

View notes

Photo

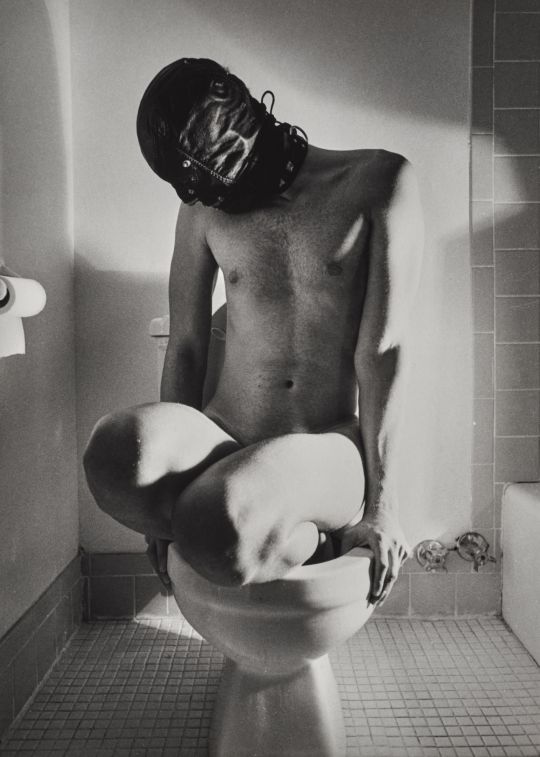

“The very word ‘submission’ contains the paradox of wanting and not wanting,” William S. Burroughs wrote in the introduction of Jimmy DeSana’s 1980 book Submission.

For the photogragraphic series featured in the publication, made between 1977 and 1978, DeSana built on 101 Nudes (1972) and his work for File Megazine by creating theatrical and often comic photographs that push the limits of respectability and explore domestic confinement, consumer affluence, and social conformity. He was also mocking the recent trend of S-M scenarios in fashion photography and advertisements.

He titled many of the images after the objects depicted in them—Toilet, Coffee Table, Television, Shoes, Shower—rather than sex acts or the names of the individuals shown, who are always anonymous and often wearing masks. This strategy not only protected the identity of his models, many of whom were friends, but also contrasted with his better-known portrait work during this period, which he did to make money. Many of the photographs comically equate practices of everyday life and consumerism (washing dishes, taking a shower, driving a car) with forms of bondage and discipline.

In exploring S-M through an aesthetic and performative lens, DeSana joined a long history of twentieth-century avant-gardes that engaged with these practices in order to compel debate on freedom of expression and power.

📷 Jimmy DeSana (American, 1949–1990). Toilet, 1977–78. Gelatin silver print, 9 9/16 × 6 3/4 in. (24.3 × 17.1 cm). Courtesy of the Jimmy DeSana Trust and P·P·O·W Gallery, New York. © Estate of Jimmy DeSana. (Photo: Allen Phillips)

#Brooklyn Museum#brooklyn#museum#art#exhibition#photography#Jimmy DeSana#JimmyDeSanaBkM#artist#lgbtq+#FILE Megazine#photographer#New York City#nyc#things to do#things to see

67 notes

·

View notes

Photo

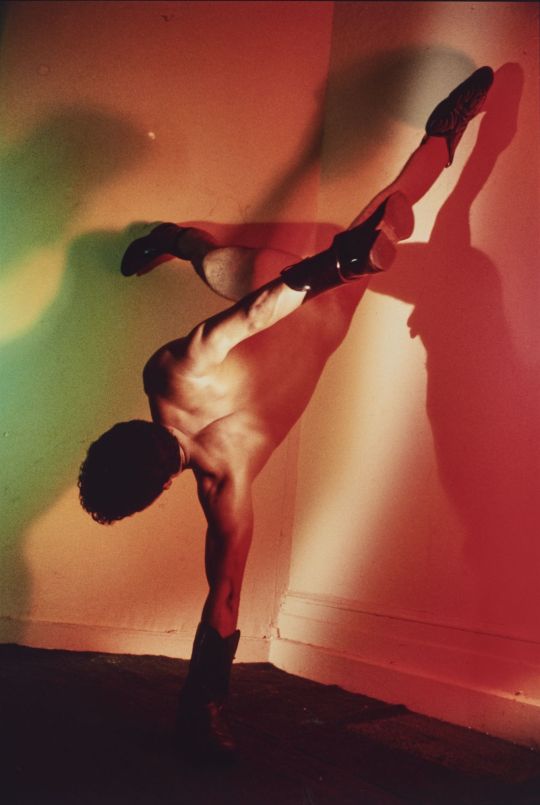

Head over heels as we head into the final week of Jimmy DeSana: Submission.

Around the time that Jimmy DeSana was starting his Suburban series, his friend Laurie Simmons also began making staged color photographs—drawing, like him, from the visual styles and iconographies of fashion photography and advertising. The two artists had a common interest in creating psychologically and emotionally complex images that ambiguously dramatize gender and sexuality, particularly in the context of postwar white suburban culture.

“We shared an obsession with the contradiction between the images of American suburbia that had been spoon-fed to us in magazines and on early television and what we were coming to understand might be the more real, more emotionally lethal story,” Laurie Simmons says.

Discover #JimmyDeSanaBkM through April 16.

📷 Jimmy DeSana (American, 1949–1990). Cowboy Boots, 1984. Silver dye bleach print, 20 × 16 in. (50.8 × 40.6 cm). Courtesy of the Jimmy DeSana Trust and P·P·O·W Gallery, New York. © Estate of Jimmy DeSana. (Photo: Courtesy of the Jimmy DeSana Trust and P·P·O·W Gallery, New York)

#Brooklyn Museum#JimmyDeSanaBkM#Jimmy DeSana#brooklyn#museum#art#exhibition#photography#artist#photographer#New York City#Laurie Simmons#lgbtq+

37 notes

·

View notes

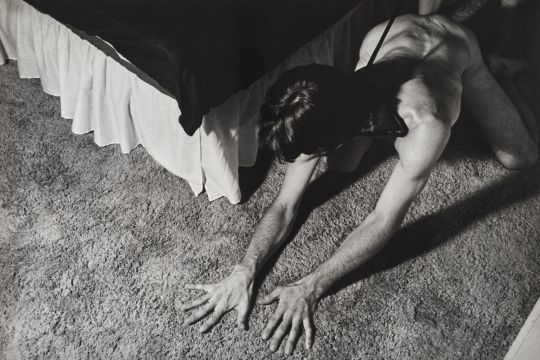

Photo

Post-punk. New Wave. No Wave.

Each of these banners refer to the informal artist groups associated with New York City’s downtown nightlife scene, experimental music and film, and alternative publications in the 1970s and 80s.

After moving to New York, Jimmy DeSana joined and helped cultivate these subcultures by photographing his friends and fellow creatives. Each of them used punk methods of production that were emphatically DIY: making do with what was immediately on hand and combining objects that repositioned and recontextualized commodities. The photograph shown here was created as part of The Dungeon Series—a collaboration between DeSana and author and dominatrix, Terrence Sellers.

The photographs from their collaboration are mostly set in Sellers’s workspace—a condominium on East 51st Street dubbed the “Dungeon”—and they have an impromptu quality.

📷 Untitled, from The Dungeon Series, 1978. Courtesy of the Jimmy DeSana Trust and P·P·O·W Gallery, New York. © Estate of Jimmy DeSana. (Photo: Allen Phillips)

#Brooklyn Museum#JimmyDeSanaBkM#Jimmy DeSana#artist#photography#photographer#New York City#nyc#exhibition#new wave#no wave#post punk#subculture#Terrence Sellers#nyc history

35 notes

·

View notes

Photo

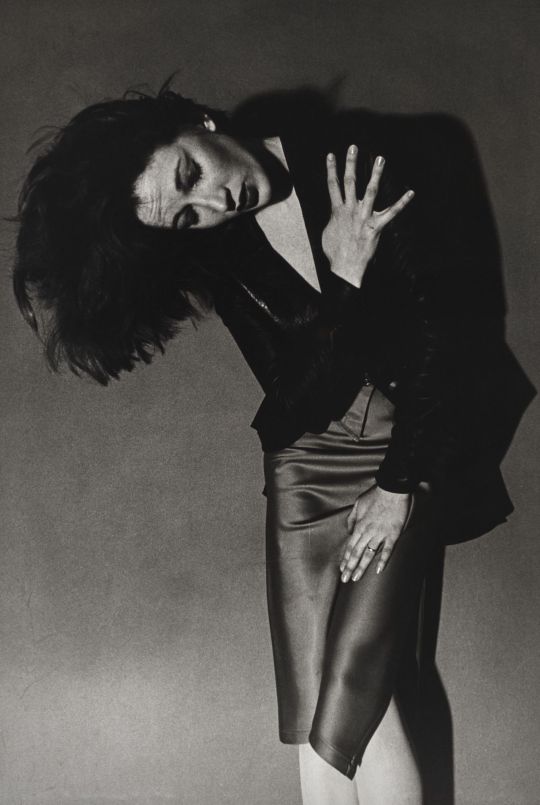

In the second half of the 1970s, Jimmy DeSana became an important portraitist of figures associated with downtown New York’s No Wave scene, such as the writer and dominatrix Terence Sellers.

DeSana often riffed on classic publicity photography from the so-called golden age of Hollywood, with dramatic poses and theatrical lighting. This celebrity-making mode dovetailed with the “ironic aesthetic strategies” of this group of artists, which the music critic Robert Christgau identified, in his 1977 article “Avant-Punk: A Cult Explodes—and a Movement Is Born,” identified as “formal rigidity, role-playing, and humor.”

The year they made this portrait, DeSana and Sellers began collaborating on a series of photographs, which documented the dominatrix with her clients and were intended to illustrate her book The Correct Sadist: The Memoirs of Angel Stern—a kind of etiquette manual for sadomasochistic practices, as told in the voice of Sellers’s alter ego.

📷 Jimmy DeSana (American, 1949–1990). Terence Sellers, 1978. Gelatin silver print, 9 5/8 × 6 1/2 in. (24.4 × 16.5 cm). Courtesy of the Jimmy DeSana Trust and P·P·O·W Gallery, New York. © Estate of Jimmy DeSana. (Photo: Allen Phillips)

#Brooklyn Museum#art#photography#Jimmy DeSana#Terrence Sellers#New York City#nyc history#nyc#no wave#JimmyDeSanaBkM

41 notes

·

View notes

Photo

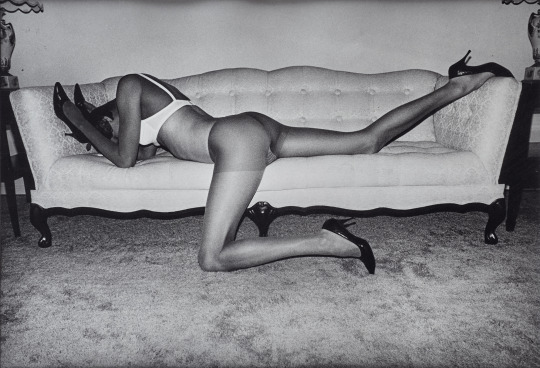

Throughout the 1970s, Jimmy DeSana created theatrical, often comic photographs related to his sexual S-M experiences.

Like other artists in his circle, such as Laurie Simmons and AA Bronson, he parodied advertising and fashion photography, as well as the disciplinary nature of heteronormativity and consumerism in the United States. He eventually published some of these photographs in his first book, Submission (1980), which included an introduction by the punk icon William Burroughs.

The photographs in this series typically feature nude, masked individuals eccentrically interacting with domestic interiors and objects. DeSana staged most images in his studio or the homes of friends and family. He used his signature lighting to create a heightened sense of drama and horror, calling attention to the images’ artifice. DeSana later observed: “I was trying to push sexuality to the limit. As long as I could come up with an idea that related to bizarre sexuality and still make an interesting statement about a product, the photo was successful for me.”

📷 Jimmy DeSana (American, 1949–1990). Sofa, 1977–78. Gelatin silver print, 6 1/2 × 9 1/2 in. (16.5 × 24.1 cm). Courtesy of the Jimmy DeSana Trust and P·P·O·W Gallery, New York. © Estate of Jimmy DeSana. (Photo: Allen Phillips)

#Brooklyn Museum#brooklyn#museum#art#artist#photography#Jimmy DeSana#JimmyDeSanaBkM#exhibition#Laurie Simmons#AA Bronson#William Burroughs

61 notes

·

View notes

Photo

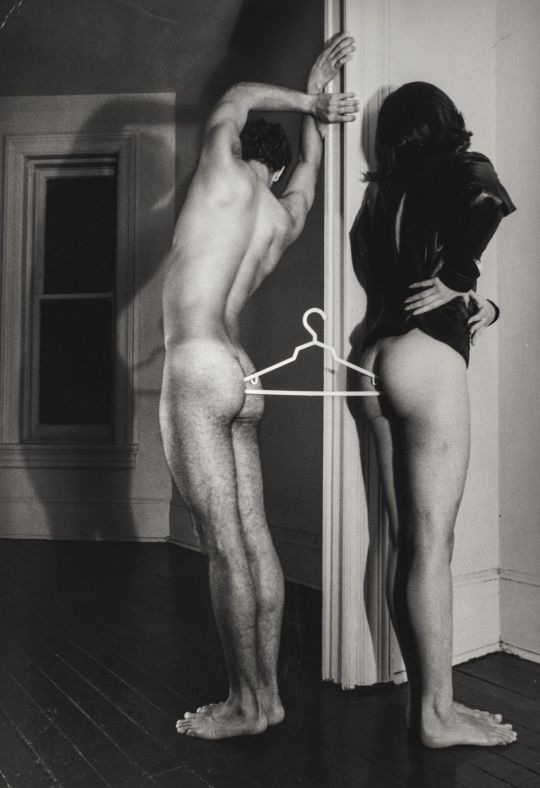

Now Open… Jimmy DeSana: Submission. 📸

On the eve of what would have been his 73rd birthday, we are honored to share with you the first retrospective of a pioneering, yet underrecognized figure—Jimmy DeSana.

Through this exhibition, you’ll come to know the facets of DeSana—the punk rebel, the queer visionary, the wry interpreter of consumerism and media cultures, and the sometime transgressor of “good taste” in photography. The project’s subtitle, Submission, is derived from DeSana’s 1980 book of often absurd photographs of S-M performances in domestic settings. In his introduction to that book, the author and punk icon William S. Burroughs wrote: “The very word ‘submission’ contains the paradox of wanting and not wanting.” DeSana’s photographic work investigates this paradox, along with the tensions between liberation and conformity, between being a subject and being an object.

Discover #JimmyDeSanaBkM and plan your visit: https://bit.ly/JimmyDeSanaBkM

📷 Jimmy DeSana (American, 1949–1990). Coat Hanger, 1979. Gelatin silver print, 9 9/16 × 6 5/8 in. (24.3 × 16.8 cm). Courtesy of the Jimmy DeSana Trust and P·P·O·W Gallery, New York. © Estate of Jimmy DeSana. (Photo: Allen Phillips)

#Brooklyn Museum#brooklyn#museum#art#exhibition#Jimmy DeSana#JimmyDeSanaBkM#photography#New York City#nyc#queer artist#photographer

102 notes

·

View notes

Photo

During the golden age of downtown performance art in the 1970s, Jimmy DeSana documented the work of numerous artists, sometimes for income.

In 1975, he photographed public interventions by Stephen Varble, an artist who performed his “Gutter Art” in the streets of Soho and Midtown, while wearing his signature gender-bending ensembles. As the critic Gregory Battcock put it, Varble came to be “considered by some the embarrassment of SoHo, and by others the only touch of real genius south of Houston Street.” DeSana’s photographs of Varble appeared in publications during this time, including General Idea’s FILE Megazine.

DeSana’s photographs are invaluable records of an ephemeral practice, which has only recently been given its proper due thanks in part to the work of art historian David Getsy. #JimmyDeSanaBkM

📷 Jimmy DeSana (American, 1949–1990). Stephen Varble, 1975. Gelatin silver print. Courtesy of the Jimmy DeSana Trust and P·P·O·W Gallery, New York. © Estate of Jimmy DeSana. (Photo: Allen Phillips)

#Brooklyn Museum#brooklyn#museum#art#Jimmy DeSana#JimmyDeSanaBkM#exhibition#photography#nyc#New York City#Stephen Varble#SoHo#nyc history

39 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Against a backdrop of policing, censorship, and gay liberation in early 1970s Atlanta, DeSana staged photographs of his mostly queer friends, including the notorious drag performer Diamond Lil, nude in suburban environments. While other Conceptual artists using photography like Dan Graham were focused on the architectural homogeneity of suburbia, in “101 Nudes,” a portfolio of 56 photolithographic prints, DeSana penetrated the veneer of seriality and conformity.

Both his subjects’ poses and his halftone reproduction techniques mimicked images from mass-market, soft-core pornographic magazines that emerged during the artist’s youth. The title sends up that of the wholesome 1961 Disney animated film 101 Dalmatians, which was rereleased in 1972.

DeSana eventually sent copies of the portfolio through the mail, which served as an alternative channel for sharing Conceptual art and challenging the privileged spaces of museums and commercial galleries during these years. He embraced “correspondence art” in part to connect with other gay artists and construct identities that defied mainstream standards of “respectability” for gay people.

📷 Jimmy DeSana (American, 1949-1990). Untitled, from the series 101 Nudes, 1972. Offset print, 12 3/4 × 8 1/2 in. (32.4 × 21.6 cm). Courtesy of the Jimmy DeSana Trust and P·P·O·W Gallery, New York. © Estate of Jimmy DeSana. (Photo: Allen Phillips)

#Brooklyn Museum#brooklyn#museum#art#exhibition#Jimmy DeSana#JimmyDeSanaBkM#photographs#photography#lgbtq+ artists

59 notes

·

View notes

Photo

“An analogue for experience.”

This is how one critic described Jimmy DeSana’s approach, which blurred otherwise rigid distinctions between “commercial” and “fine art” photography.

On April 4, in the spirit of DeSana, we are making way for modes of expression during a poetry-writing workshop. We will take a close look at how DeSana used photography, mail art, zines, and more to convey the radical spirit of the 1970s and 80s and critique the American dream.

All experience levels are welcome! Get your ticket: http://bit.ly/3yYhzHH

📷 Jimmy DeSana (American, 1949–1990). Aluminium Foil #4 (Self-Portrait), 1985. Cibachrome print, 14 × 11 in. (35.5 × 27.9 cm). Courtesy of the Estate of Jimmy DeSana. © Estate of Jimmy DeSana. (Photo: Allen Phillips)

#Brooklyn Museum#brooklyn#museum#photography#artist#JimmyDeSanaBkM#Jimmy DeSana#exhibition#New York City#nyc#nyc events#event#poetry#national poetry month

29 notes

·

View notes

Photo

What title would you give this photograph?

For his 1980 book of S-M-themed photographs titled “Submission,” Jimmy DeSana named the images after the objects depicted in them. Take this performative picture, Coffee Table, for example.

In the book comprised of 29 black-and-white photographs, DeSana created theatrical and often comic photographs that relate to his own personal experiences of sex, and also affectionately parody themes of suburbia and consumer affluence.

Join us on March 23 for Art History Happy Hour dedicated to Jimmy DeSana. We'll discuss the artist's subversive aesthetic and participation in avant-garde movements, ranging from queer mail art networks to punk music and cinema with Drew Sawyer, Laurie Simmons, and Carlos Alejandro Motta.

🎟 http://bit.ly/3LaSb8M

📷 Jimmy DeSana (American, 1949–1990). Coffee Table, 1977–78. Gelatin silver print, 9 1/2 × 6 1/2 in. (24.1 × 16.5 cm). Courtesy of the Jimmy DeSana Trust and P·P·O·W Gallery, New York. © Estate of Jimmy DeSana. (Photo: Allen Phillips)

#Brooklyn Museum#brooklyn#museum#JimmyDeSanaBkM#Jimmy DeSana#photography#photographer#artist#lgbtq+#Suburban#exhibition#sexuality#art history happy hour

35 notes

·

View notes

Photo

In a 1986 interview with Diego Cortez, Jimmy DeSana remarked on the mutability and transgressive potential of photography: “A photograph is how much you want to lie, how far you want to stretch the truth about the object. And, as photography is always based on real objects, it lends itself, by means of technique or manipulation, to explorations of what may appear to be an absence of reality, balancing on an ambiguous line between concrete and abstract space, between reality and illusion, in a way that no other medium is able to do.“

In a series of “portraits” from the mid 1980s, DeSana played with this tension by obscuring and transforming faces through collage and darkroom techniques. His movement into abstraction—in works that nonetheless address his experience living with HIV/AIDS—was in part a reaction to dilemmas over representations of sexuality and queer bodies during the first decade of the AIDS epidemic, from media bias to conservative censorship to activist demands. Critics recognized DeSana’s masquerades and darkroom experiments in color as tributes to Surrealist photography of the 1920s and 1930s, which still had the power to confound expectations around photography and realism.

📷 Jimmy DeSana (American, 1949–1990). Untitled (Man with Antler), 1985. Silver dye bleach print, 13 1/4 × 10 1/4 in. (33.7 × 26 cm). Courtesy of the Jimmy DeSana Trust and P·P·O·W Gallery, New York. © Estate of Jimmy DeSana. (Photo: Allen Phillips)

#Brooklyn Museum#brooklyn#museum#art#photography#Jimmy DeSana#JimmyDeSanaBkM#lgbtq+#portraits#surrealist#darkroom

31 notes

·

View notes