#King Gudea

Text

The monumental royal cone of Gudea

Official or display cone excavated in Girsu (mod. Tello), dated to the Lagash II (ca. 2200-2100 BC) period and now kept in Manchester Museum, University of Manchester, Manchester, UK.

Sumerian Text

(d)nin-gir2-su ur-sag kal-ga (d)en-lil2-la2 lugal-a-ni gu3-de2-a ensi2 lagasz(ki)-ke4 nig2-du7-e pa mu-na-e3 e2-ninnu anzu2(muszen)-babbar2-ra-ni mu-na-du3 ki-be2 mu-na-gi4

Source: CDLI

Translated text

For Ningirsu, the mighty warrior of Enlil, his master, Gudea, ruler of Lagash, made a fitting thing resplendent for him, and his Eninnu with the White Thunderbird he built for him and restored for him.

Source: P234000: royal-monumental cone

I see six names in the text, the names of two gods, the name of Gudea and the name of a temple [E+ninnu] (cuneiform e2 meaning temple), the name of the city of Lagasz (lagash(ki)) and the title ensi2 meaning governor and ruler.

Ninurta or Ninĝirsu (meaning Lord of Girsu) is the name of an ancient Mesopotamian god associated with agriculture, healing, hunting, law, scribes and war. He was the son of Enlil. In the text, Enlil is introduced as the lord of Ninĝirsu. (lugal-a-ni)

Ninĝirsu was honored by Gudea, who was the ruler of the city of Lagash (ensi2 lagasz(ki)-ke4).

Gudea mentions in the text that he built the Eninnu Temple (e2 ninnu 𒂍𒐐) with White Thunderbird for Ninĝirsu.

#history of mesopotamian kings#mesopotamia#ancient mesopotamia#archaeology#ancient history#akkadian#sumerian city#sumerian#sumerian language#city of girsu#gudea#sumerian kings

0 notes

Text

While drawing the Manager after MotR and comparing to my earlier pre-MotR attempts, I thought maybe I can also try to combine the canon version with what-have-been-in-my-head-for-years-of-text-descriptions – different eye colour (dark or brassy), a bit older, not as spotlessly smooth-faced...

Then I wondered if I’m too influenced by "Mesopotamian = beard" stereotype (in fact there are plenty of beardless kings in Sumerian and Akkadian art, such as Gudea or Ibbi-Sin, off the top of my head). Hmm, I thought, actually I can imagine him shaving while whistling nursery rhymes and casually ignoring that the mirror can’t properly reflect him without bleeding nightmares...

Then I remembered that in cultures where beards have significance, shaving it off is also usually a sign of mourning, self-shame or grief. And in MotR a whole city was destroyed just a few months ago, and a new one fell similarly catastrophically:

...so at that time May does have a reason to be in mourning (at least formally/ritualistically, if he wasn’t close to those he knew in the Fourth City). Even more, he might have been grieving since the First City, judging by how he always speaks of his story with no ability to let go.

Oh well. 5 years in Fallen London, and I still can’t think about him without this risk of unscheduled emotions. Even over visual design, forgodssake. (Though these cheekbones ARE heart-wrenchingly gorgeous, by the way.)

32 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Sumerian stone bust of the priest-king Guedea of Lagash, dating back to 2150 BCE. It is one of twenty-seven statues of Gudea that have been found in southern Mesopotamia. Chrysler Museum of Art, Norfolk, VA.

Photo by Babylon Chronicle

272 notes

·

View notes

Text

Herodotus and the Babylonian "Sacred Marriage"

"The metaphorical substance of the “sacred marriage” expressions was appreciated by all who shared the ANE lore including the Greek historian Herodotus of Halicarnassus (484–425 BCE) as evident by his description of the ziggurat at Babylon. I here argue that although the text has been often quoted as corroborating evidence for the practice of actual “sacred marriages” in the ANE (and the overall disapproval of the Greeks for the practice), a closer reading can reveal that Herodotus does not refer explicitly to sex between a priestess and the god. Once we establish that the “love” of the goddess is metaphorical, then the shift between the millennia becomes primarily an aesthetic one. The text (Hdt.1.181.5–182.1–2) reads:145

ἐν δὲ τῷ τελευταίῳ πύργῳ 146 νηὸς ἔπεστι μέγας· ἐν δὲ τῷ νηῷ κλίνη μεγάλη κέεται εὖ ἐστρωμένη, καὶ οἱ τράπεζα παρακέεται χρυσέη. ἄγαλμα δὲ οὐκ ἔνι οὐδὲν αὐτόθι ἐνιδρυμένον, οὐδὲ νύκτα οὐδεὶς ἐναυλίζεται ἀνθρώπων ὅτι μὴ γυνὴ μούνη τῶν ἐπιχωρίων, τὴν ἂν ὁ θεὸς ἕληται ἐκ πασέων, ὡς λέγουσι οἱ Χαλδαῖοι ἐόντες ἱρέες τούτου τοῦ θεοῦ. φασὶ δὲ οἱ αὐτοὶ οὗτοι, ἐμοὶ μὲν οὐ πιστὰ λέγοντες, τὸν θεὸν αὐτὸν φοιτᾶν τε ἐς τὸν νηὸν καὶ ἀμπαύεσθαι ἐπὶ τῆς κλίνης, κατά περ ἐν Θήβῃσι τῇσι Αἰγυπτίῃσι κατὰ τὸν αὐτὸν τρόπον, ὡς λέγουσι οἱ Αἰγύπτιοι· καὶ γὰρ δὴ ἐκεῖθι κοιμᾶται ἐν τῷ τοῦ Διὸς τοῦ Θηβαιέος γυνή, ἀμφότεραι δὲ αὗται λέγονται ἀνδρῶν οὐδαμῶν ἐς ὁμιλίην φοιτᾶν· καὶ κατά περ ἐν Πατάροισι τῆς Λυκίης ἡ πρόμαντις τοῦ θεοῦ, ἐπεὰν γένηται· οὐ γὰρ ὦν αἰεί ἐστι χρηστήριον αὐτόθι· ἐπεὰν δὲ γένηται τότε ὦν συγκατακληίεται τὰς νύκτας ἔσω ἐν τῷ νηῷ.

And in the last tower there is a large cell and in that cell there is a large bed, well covered, and a golden table is placed near it. And there is no image set up there nor does any human being spend the night there except only one woman of the natives of the place, whomsoever the god shall choose from all the women, as the Chaldaeans say who are the priests of this god. These same men also say, but I do not believe them, that the god himself comes often to the cell and rests upon the bed, just as it happens in the Egyptian Thebes according to the report of the Egyptians, for there also a woman sleeps in the temple of the Theban Zeus (and both these women are said to abstain from interacting with men), and as happens also with the prophetess of the god in Patara in Lycia, whenever there is one, for there is not always an oracle there, but whenever there is one, then she is shut up during the nights in the temple within the cell.

Although Herodotus concedes that the god “chooses” the woman (ἕληται) and that he “rests” upon the bed (ἀμπαύεσθαι ἐπὶ τῆς κλίνης) – implying sleeping with the priestess, in fact, what the priests say, using their usual figurative language,147 is that the god visits the woman and inspires her during her sleep with one of his oracles. The phenomenon was apparently known, as Herodotus stresses, in Egyptian Thebes and Lycia. Therefore, it could be argued that the practice may well refer to cases of incubation148 in search for the divine will which was popular throughout the ANE; in fact, it was generally believed that divine dreams could be precipitated by sleeping at the temple of the god,149 a notion familiar to the Greeks

of the Hellenistic period, who believed in therapeutic incubation, especially in connection with the cult of Asclepius.150 In ANE tradition, the dreams often had to do with legitimizing the king’s rule 151 and were attested from the earliest times: therefore, Edzard cited the early example of Gudea of Lagash (ca. 2144–2124 BCE), inscribed on a cylinder (E3/1.1.7 CylA); according to the text, Gudea seeks a dream from the god Ningiršu which he then aims to relate to his mother, a dream interpreter, for further analysis.152 As discussed in Chapter 1, from the time of Gudea 153 to the time of Tukulti-Ninurta I (1244–1208 BCE) building temples became a sign of divine favour and at the same time a way of securing the immortality of the king.154 In one message dream from Ištar, the message is for Aššurbanipal, but the goddess has sent it through a professional dream interpreter, to pass on to the king. The dream occurs during the war against Elam presumably in the temple; while Aššurbanipal prays, and indeed receives comforting words from the goddess himself, apparently while awake, the goddess sends a dream to a šabrû (a male dream interpreter) with further instructions concerning what Aššurbanipal should do.

Since message dreams can be used to justify political actions, Butler interprets the dreams as “propaganda.” For example, the dream of Gudea explains the motivation behind building a temple (Gudea Cylinder A). Having received an unsolicited dream from the god Ningiršu, Gudea, seeking further help, offers bread and water to the goddess Gatumdug, then sets up a bed next to her statue and sleeps

there, having prayed to Gatumdug for a sign, and calling on the goddess Nanše, the interpreter of dreams, to interpret it for him. All the dreams relate to the building of the temple. The Hittites had a similar practice in which the receiver of the dream could be either the king himself or a prophet or a priestess.155 It is also worth examining here the case of Nabonidus (556–539 BCE), whom Herodotus

refers to as Labynetus (Hdt.1.77, 188) and who interpreted a lunar eclipse on the 13th of the month Elul as a celestial sign from the Moon-god who “desired” a priestess, understood to be the god’s “mistress” (īrišu enta).156

Obviously, the question to be asked here is whether any member of the ancient audiences, including Herodotus, understood these reports to imply actual sexual activity between the god and the priestess. The metaphorical understanding of “sacred marriage” ceremonies could ease a number of unresolved debates such as whether a “sacred marriage” was included in the akītu festival and whether it was ever found “distasteful” by the Hellenistic kings. Herodotus’ rendering seems to be quite close to the figurative speech found in cuneiform sources, such as the clay cylinder of Nabonidus reportedly from Ur.157 In addition, Herodotus does not seem to comment specifically on the nature of the relationship between the god and his chosen priestess, probably because he appreciated the allegorical language of the priests.158 What he doubts, though, is that any actual epiphany took place in this instance or even whether divine epiphanies could be thus achieved.159 Hence, Herodotus’ objection does not relate to the “sacred marriage” ceremony at all but to the rite’s effectiveness as a means of communicating with the divine. Such reading is compatible with recent evaluations of Herodotus and his employment of religion as a way of explaining the downfall of powerful rulers; it is not the god who is at fault, of course, but the mortal worshippers who fail to interpret the signs correctly.160 Interestingly a number of texts accuse Nabonidus of cultic innovations that had not been demanded by the gods at all.161 Nabonidus’ religious piety had already been systematically exaggerated in the autobiography of his mother,

Adad-guppi, as a way of legitimizing her son’s claim to power, and hence, the god’s “desire” for Nabonidus’ daughter should be understood in the same light.162"

Eva Anagnostou-Laoutides In the Garden of the Gods. Models of kingship from the Sumerians to the Seleucids, Routledge 2017 (pp 84-86)

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Sumerian Mythology - The earliest deities of ancient Mesopotamia (59)

Superhuman monsters vanquished by the god Ninurta – Anzu

In Sumerian and Akkadian mythology, Anzu is a divine storm-bird and the personification of the southern wind and the thunder clouds. This demon—half man and half bird, Anzu was depicted as a massive bird who can breathe fire and water, although Anzu is alternately depicted as a lion-headed eagle.

Along with the "Lugal-e", there is the "Anzu Myth", a detailed account in Akkadian of how Ninurta killed the monster bird Andu.

Both stories were written in the early second millennium BCE. It is a story of Ninurta's struggle to conquer the Anzu, which had stolen the "Tablet of Destinies". The extermination of the Anzu was a proud achievement for Ninurta, as it was considered a symbol of the destruction of the cosmic order.

In those myths, the Anzu is vanquished as a villain, but this is a later story, and the original Anzu was not a monster bird, but a sacred bird. It is obvious, as a royal inscription from the reign of King Gudea describes the temple of Eninu in Lagash as "the temple of Eninu, the white Andu bird".

The sacred bird Anzu is represented as a symmetrical figure with its wings spread wide, and in the city of Lagash it is often accompanied by a lion at its feet. Presumably the lions symbolised the god Ninurta and the Anzu bird the supreme Sumerian god Enlil.

Anzu also appears in the story of "Inanna and the Huluppu Tree [Ref2]", which is recorded in the preamble to the Sumerian epic poem Gilgamesh, Enkidu, and the Netherworld [Ref]. Anzu appears in the Sumerian Lugalbanda and the Anzu Birds (Ref3, also called: The Return of Lugalbanda ).

シュメール神話~古代メソポタミア最古の神々(59)

ニヌルタ神が退治した超人的怪物たち〜アンズー鳥

シュメールやアッカドの神話では、アンズーは南風と雷雲を擬人化した神の嵐鳥である。この半人半鳥の悪魔アンズーは火と水を吐く巨大な鳥として描かれていたが、アンズーは獅子頭の鷲として描かれていることもある。

『ルガル・エ』と並び、ニヌルタ神が怪鳥アンズーを退治する次第を詳細にアッカド語で書いた『アンズー鳥神話』がある。どちらも前���千年初期にはすでに書かれていて、「天命の粘土板」を盗んだアンズー鳥をニヌルタ神が苦心の末に征伐する物語である。アンズー鳥は宇宙の秩序を破壊する象徴として考えられていたので、アンズー鳥退治はニヌルタの誇るべき功業であった。どちらも前二千年初期にはすでに書かれていて、「天命の粘土板」を盗んだアンズー鳥をニヌルタ神が苦心の末に征伐する物語である。

それらの神話では、アンズー鳥は悪役として退治されるが、それは後代の話であり、本来のアンズーは怪鳥ではなく、霊鳥であった。グデア王時代の王碑文では、ニヌルタ神のラガシュのエニンヌ神殿を「白いアンズー鳥であるエニンヌ神殿」と形容しており、明らかにアンズー鳥は霊鳥であり、ニヌルタ神の象徴であった。

霊鳥アンズーは翼を大きく広げた左右対称の姿で表され、ラガシュ市ではしばしば獅子を足元に従えている。獅子はニヌルタ神をアンズー鳥はシュメールの最高神エンリル神を象徴していたと考えられる。

また、アンズー鳥はシュメールの叙事詩「ギルガメシュとエンキドゥと冥界(参照)」の前文に記されている「イナンナとフループの木(参照2)」の話にも登場する。アンズー鳥はシュメールの「ルガルバンダとアンズー鳥(参照3)」(別名:ルガルバンダの帰還)にも登場する。

#anzu#lugal e#anzu myth#sumerian mythology#sumerian gods#ninurta#lagash#tablet of destinies#enlil#king gudea#mythology#legend#folklore#hybrid creatures#nature#art#ancient mesopotamia

89 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ninshubur, Inanna’s Sukkal: Just a Servant or Something More?

Special thanks to my girlfriend for providing the vintage shoujo parody above, feat. Inanna, Ninshubur and Eblaite artifacts

Due to its unique character this post requires a special preface.

Most of my “serious” coverage of mythology is meant to be presented as rigorously as possible for a layperson doing this mostly for entertainment, which is who I ultimately am. This post represents a departure from this standard - it’s basically entirely unfounded speculation, personal feelings and wishful thinking. Similar posts often get passed around accompanied by grandiose claims from commenters, so I will stress that I wrote this for personal reasons and only discuss personal feelings. I do not claim this is some sort of suppressed truth, as I am particularly not fond of cases where personal interpretations - which I view as valid if they are acknowledged as just that - are used to claim modern, rigorous research is in fact phony or a nefarious conspiracy.

With that out of the way - as stated in the title, I’m going to discuss a case which as many of the regular readers are aware of is close to my heart - that of how Mesopotamian literature depicts the relationship between Inanna and Ninshubur (a deity I like so much that she now has a longer and better sourced wikipedia page than many more major Sumerian deities). I plan to show why I personally think that regardless of the intent of the original authors, there is enough subtext in known sources - presumably not necessarily intentional - to interpret them as a couple. I will also try to highlight Ninshubur’s rarely discussed prominence, both in myths and elsewhere.

Parts of the article simply discuss vaguely relevant historical background and primary sources. As usual, I am also providing a bibliography. Therefore, I hope that even if you are not really interested in ultimately pretty silly speculation, you will find something interesting under the cut. Meanwhile, if you are interested in relationships between women more than scholarship, I hope that this post will serve as a fun example why the study of mythology can lead one to find unintended subtext.

The basics - Inanna, Ninshubur and the descent myth

Impression of a cylinder seal from the Old Akkadian period depicting Inanna (Wikimedia Commons)

Inanna was one of the major deities worshiped by the Sumerians, the ancient inhabitants of the southern part of modern Iraq. She was also adopted into the beliefs of other cultures of ancient Mesopotamia. In hierarchical listings of deities she is usually placed somewhere right behind the pantheon heads. She was responsible for, among other things, kingship, love, war and assorted celestial matters. She is also one of the most recurring deities in literary compositions written in Sumerian, with a considerable number being available as part of the Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature.

Inanna’s love life was regarded as rather complex. Her most recurring lover was the shepherd god Dumuzi, who is a classic specimen of the clade of periodically dying deities, a category which also included the likes of medicine godling Damu, king Gudea’s personal deity Ningishzida and the elusive underworld god Alla. Multiple narratives about the courtship and love of Inanna and Dumuzi were in circulation in antiquity, most of them joyful. However, some also deal with Dumuzi’s untimely death (which,it should be noted, was also a subject of works unrelated to his relationship with Inanna). The degree of Inanna’s involvement varied from composition to composition, from cause to passive onlooker to vengeful avenger. Arguably, however, the most famous is Inanna’s Descent, in which Dumuzi’s death is attributed to his unwillingness to mourn Inanna during *her own* temporary death.

A prominent aspect of this myth is also Inanna’s reliance on Ninshubur, a goddess of slightly lesser caliber serving as her sukkal. Sukkal is a term which can refer to a deity’s “ second in “command” - in other words, a sidekick. The word was also used to describe a rank of human court officials, in which context authors variously translated it as “vizier” or “envoy”. Despite the nature of her position, Ninshubur’s status was hardly a minor deity, judging from her popularity in the sphere of personal worship and from a number of theological texts. She was arguably the archetypal example of a sukkal, and her functions - those of a divine messenger, diplomat and mediator - largely stem from this status.

Dumuzi’s and Ninshubur’s roles in the story differ greatly. Prior to the reveal that he was not partaking in the customary mourning rites, Dumuzi has minimal presence in the narrative. Ninshubur, by contrast, is an active participant, entrusted with enacting an emergency plan in case of Inanna’s prolonged stay in the underworld, equivalent to death. A long section is dedicated to her grief and to the journey she undertakes to attempt to convince major gods to resurrect Inanna. Ninshubur’s adventure culminates in the creation of two artificial genderless beings who manage to revive Inanna, at the command of the god Enki.

Subsequently, Ninshubur reunites with the resurrected Inanna, who praises her for her devotion and protects her from the galla, demonic underworld constables. The term also denoted mundane policemen, or at least people who could be roughly considered their equivalent in ancient Mesopotamia. In the discussed myth, they are meant to deliver a replacement for the resurrected Inanna to the underworld at the orders of its ruler, Ereshkigal.

In this myth - but surprisingly not anywhere else - Ereshkigal is regarded as Inanna’s older sister. Much of the popular perception of the story appears to be centered on this relation but it is ultimately Ninshubur whose connection with Inanna is particularly close, as seen in the quote below (all quotes from Inanna’s Descent in the article are sourced from ETCSL):

This is my minister of fair words, my escort of trustworthy words. She did not forget my instructions. She did not neglect the orders I gave her. She made a lament for me on the ruin mounds. She beat the drum for me in the sanctuaries. She made the rounds of the gods' houses for me. She lacerated her eyes for me, lacerated her nose for me. She lacerated her ears for me in public. In private, she lacerated her buttocks for me. Like a pauper, she clothed herself in a single garment.

All alone she directed her steps to the Ekur, to the house of Enlil, and to Urim, to the house of Nanna, and to Eridug, to the house of Enki. She wept before Enki. She brought me back to life. How could I turn her over to you?

Afterwards, Ninshubur, who apparently spent the rest of her Inanna-free time weeping at the entrance to the underworld, accompanies Inanna during visits to various lesser underlings’ houses (well, temples); as it turns out, they too mourned properly, and after brief words of praise are left to their own devices. However, that is not the case when it comes to Dumuzi:

They followed her to the great apple tree in the plain of Kulaba. There was Dumuzid clothed in a magnificent garment and seated magnificently on a throne. The demons seized him there by his thighs. (...) They would not let the shepherd play the pipe and flute before her

She looked at him, it was the look of death. She spoke to him, it was the speech of anger. She shouted at him, it was the shout of heavy guilt: "How much longer? Take him away." Holy Inanna gave Dumuzid the shepherd into their hands.

The rest of the myth is poorly preserved, but seemingly Inanna eventually has a change of heart and the well-known system in which Dumuzi and his sister switch places in the underworld every 6 months is established.

The ending doesn’t address why it was Ninshubur, rather than Dumuzi, who received the instructions pertaining to the mourning of Inanna’s death and her subsequent resurrection. It doesn’t also explain why Ninshubur stood by the entrance of the underworld, waiting for Inanna, something not even the other mourners did.

The goal of this article is to find out if there are any grounds to assume that there is a romantic component to this issue, at least from a modern point of view. I’ve noticed that there are few, if any, academic publications dealing with related matters, and that generally potential lesbian subtext - intended or not - in myths generally is hardly discussed, therefore I hope it will be an interesting curiosity to you, if nothing else.

Gay relationships in Mesopotamian mythology

Naturally, the first question which needs to be addressed is whether any form of love between people of the same gender occurs in relevant literature in the first place. The answer is a cautiously optimistic “yes.”

Of course, almost everyone is aware of the speculation about the nature of the relationship between Gilgamesh and Enkidu, the most famous heroes of Mesopotamian literature. Therefore it probably comes as no surprise to any readers that many modern authors seek evidence that at least in some portrayals they were in love. The problem is arguably less whether anyone did interpret them as in love, and more how common it was and which sources show it best. Authors who present this view include the world’s arguably greatest Gilgamesh expert, Andrew R. George, as well as hittitologist Gary Beckman.

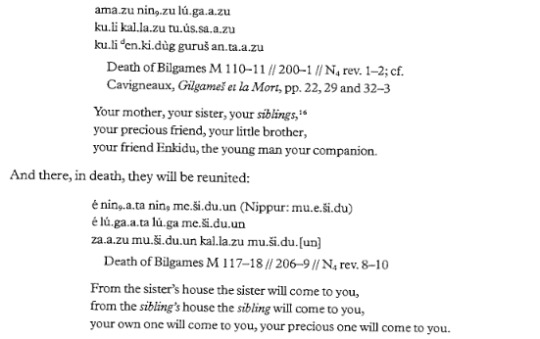

According to George, the notion that Gilgamesh and Enkidu loved each other is present first and foremost in a version of the poem Death of Gilgamesh, known from Tell as-Sib excavations in Iraq’s Diyala region (ancient Me-Turan). The poem is Sumerian in origin and predates the famous standard Epic of Gilgamesh, which only developed after the Old Babylonian period.

The passage in mention is apparently not actually present in many of the known copies. It features the head god, Enlil, informing elderly, sick (the illness seems to be the doing of Namtar, known as both a disease of death and as an envoy of the netherworld) Gilgamesh that in the afterlife he’ll be reunited with Enkidu. Due to the emotional value of this passage I will simply let you read it yourself:

The Babylonian Gilgamesh Epic: Introduction, Critical Edition and Cuneiform Texts vol 1 by A. R. George, p. 142

The belief that loved ones might be reunited in the afterlife appears in texts from various periods of Mesopotamian history, so it can be safely assumed it was not an uncommon idea, even if the most famous myths present the afterlife as incredibly unpleasant. Additionally, Enkidu is evidently treated as a member of Gilgamesh’s family but not a sibling here.

My first thought after reading George’s description of the Me-Turan version of the tale of Gilgamesh and Enkidu was to wonder if it is possible that versions which seemingly stresses the view of them as a couple might reflect the needs of a specific audience.

Thanks to George’s own studies, as well as those of other authors, we do know that the stories of Gilgamesh were often adapted to fit the tastes of one audience or another. For example, in Hurrian and Hittite translations locally popular deities, such as Shaushka (known as “Queen of Nineveh” or “Ishtar of Subartu”), Hittite Sun God of Heaven, or personified Sea known in both these cultures factored into the story (both as replacements of familiar characters and as stars of brand new “story arcs”), while the descriptions of distant Uruk are often shortened as they were of comparatively little interest to inhabitants of Syria and Anatolia.

Could therefore the Me-Turan version represent an adaptation written by and/or for people who were invested in the view of Gilgamesh and Enkidu as a couple more than the average aficionado of similar poetry in ancient Mesopotamia? That would be my assumption, but you should bear in mind it is nothing more than that I am not an actual authority.

I am not aware of any examples of mythical figures other than Gilgamesh and Enkidu engaging in similar endeavors. The other potentially relevant evidence comes from different genres of texts, such as omens, magical formulas and (middle Assyrian) laws. Sadly, there isn’t much evidence for gay relationships and what there is doesn’t necessarily match the sphere of myth, to put it lightly (the aforementioned legal texts, in particular, are not exactly pleasant to read). For what it’s worth, there are sporadic references to love magic meant to guarantee the love of a man for another man, alongside the much more common straight variations (both with men and women as targets of the ritual).

I will not address the issue of the galla (not to be confused with the homonymous underworld constables!) and similar priestly classes here as the matter is not settled, and many researchers involved are hardly rigorous (this article in particular is a nightmare but it’s not much better elsewhere). All that can be said about the galla with certainty is that they were lamentation singers. It has been argued that they were possibly regarded as possessing a distinct, unique identity, but what that entailed is hard to tell. It does appear that their mythical counterparts in Inanna’s Descent, the two entities created by Enki, are genderless, at the very least.

Galla priests performed songs in a “dialect” of Sumerian, emesal, popularly understood as “women’s speech” - however, it’s not really an accurate translation. While the precise meaning is unclear, something like “high pitched speech” might be more appropriate. Emesal is sometimes regarded as a “sociolect” spoken by a specific group (ie. women) but it’s actually more likely to be first and foremost a “genrelect” reserved for specific liturgical purposes according to recent research. As summed up by Piotr Michalowski in a very brief encyclopedic summary, it appears to be “restricted to direct speech of goddesses and women in certain types of literary texts, in particular lamentations.”

Bear in mind even this use is not universal: Dumuzi speaks emesal in some texts, Inanna does not in others. Enheduanna, arguably the most famous woman in Mesopotamian history, did not write in emesal, even when it came to direct speech; meanwhile, there are references to purification specialists - who were not galla - reciting emesal texts.

Emesal aside - no primary sources actually discuss the sexuality of the galla to any meaningful degree and it’s not even certain if all galla were assigned male at birth, to put it in modern terms. Therefore, any such assumptions pertaining to them are just speculation, often with a dash of vintage orientalism thrown in for good measure.

That’s it for men. How about women?

As noted by Frans Wiggermann in his brief and somewhat flawed overview of references to sexuality in Sumerian and Akkadian texts there are no known direct references to women attracted to women and to relevant activity in any primary sources (I think there is a passage in a late hymn to Nanaya which might be an exception, I wrote about it a few months ago). He provides no clear explanation for this, though he notes that most scribes were obviously men aligned with the dominant power structures. This state of affairs largely shapes the character and contents of many sources.

I personally think it’s safe to say that the fact the literacy rate among men was much higher than among women is at least partially to blame.

Female literacy, religiosity and relationships between women in myths

Generally speaking, the level of literacy even in cultures with a rich scribal tradition was naturally pretty low in the bronze and iron ages, with the only estimate I found (pretty old, I should note) being 2-5% for “western Asia and Egypt” collectively. These are therefore presumably the figures we can apply to ancient Mesopotamia for example in the Ur III and early Old Babylonian periods, when many of the famous myths developed in their presently known textual forms.

While it was not entirely impossible for a woman to become a scribe, or to learn how to write through other means (ex. as part of a noblewoman’s preparation for courtly life), it was much less common for them than for men. For instance, only between 4 and 6 (2 cases are uncertain) scribes or scholars identified by name in colophons of known texts were women.

Of course, not every text has a colophon with such information, so it’s not impossible that we in fact know more texts written or copied by women, but whose authorship will never be possible to prove. It’s also worth noting these few examples indicate the presence of women (not many, but still) on most stages of scribal education. Nameless female scribes also at times appear in economic documents. Nevertheless, references to women in other similar professions are somewhat infrequent. The exception to this was female physicians, who were generally expected to be literate. I’ve gathered some more detailed information here.

This perhaps is somewhat of a reach, but I personally assume both the lack of references to romantic relations between women and the relatively small number of compositions dealing with bonds between female deities seemingly not based on blood relation (and even the latter are hardly common!) can be attributed to the comparatively small number of female scribes, outlined above. A similar argument has been advanced by Alhena Gadotti, though in reference to mortal women as characters in texts copied in scribal schools: women “were generally not part of the cultural, political, and economic elite that the Old Babylonian scribal schools produced and therefore did not play a particularly prominent part in the corpus.”

As remarked by Joan G. Westenholz and Julia M. Asher-Greve, interest in female deities was somewhat higher among women than men - “numerous women chose the temple of a goddess for their votive gifts (...), or preferred the cult of a goddess (...), or have names composed with that of a goddess, or are depicted worshiping a goddess” [on cylinder seals - clarification mine]. It’s of course impossible to deal in absolutes, though - there’s ample evidence for personal devotion to gods like Shamash, Zababa, Dagan or Marduk among women, and to goddesses such as Inanna, Ninisina or Namma among men; kings were almost always men but there is a fair share of areas where the source of kingship was at least in certain time periods held to be a female deity - Ninisina in Isin in the Isin-Larsa period, Ishara in Ebla c. 1700 BCE, Belet Nagar, nomen omen, in Nagar in the Old Babylonian period, Inanna in Uruk at various points in time, etc. Still, I think the point might be valid.

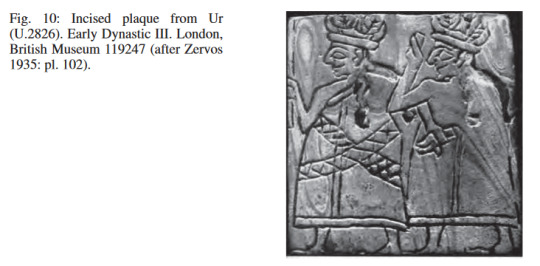

A possible depiction of Geshtinanna and Geshtindudu (Goddesses in Context by J. M. Asher-Greve and W. G. Westenholz, p. 387; identified as such on p. 168)

Other than Inanna and Ninshubur in Inanna’s Descent and a number of other sources, the only two goddesses I am aware of who appear to share a close bond in myths and aren’t a mother-daughter pair (like Nisaba and Sud/Ninlil or Ninhursag and Ninkasi) are Dumuzi’s sister Geshtinanna and a certain Geshtindudu, who are to my knowledge not attested outside of a small handful of mythical fragments. Julia M. Asher-Greve outright describes these two as “divine girlfriends' ' - I presume not in the romantic sense, though. This is probably just a paraphrase of the ETCSL translation of Dumuzid’s Dream which indeed introduces Geshtindudu as “Her [Geshtinanna’s] girl friend.” Asher-Greve also speaks of it as “one of the few relationships between goddesses based on friendship.”

As for other relations based on friendship: I’ve seen references to a myth(?) about Ninisina and Nintinugga - the medicine goddess par excellence and her small time “ersatz” from Nippur - visiting each other (source; it’s on p. 5), but I have not been able to locate it so I can’t tell if it should count as another example.

Additionally, while the myth Enlil and Sud deals first and foremost with the relationship between Sud and her mother Ninlil and with her tumultuous romance with Enlil, it seems a poorly preserved section also had Sud interact with Enlil’s sister Aruru (who you may know as the creator of Enkidu in the Epic of Gilgamesh). Given how Enlil and Sud generally seems to have notably more “Ninlil-centric” outlook than its “rival” myth Enlil and Ninlil (which treats Ninlil, a popular and high-ranking deity, oddly poorly), perhaps this should be counted as an example too, though it has been argued the passage might simply indicate that the bridegroom’s sibling played some role in traditional marriage rites.

While each of these myths surely could be an interesting topic, I sadly won’t discuss them in detail here (do expect a post on Enlil and Sud at some point, though), as the this article is ultimately about Inanna’s Descent and other sources pertaining to Ninshubur.

Inanna’s Descent once more

While I already provided a brief overview of Inanna’s Descent earlier, the fact that its contents are frequently misinterpreted - often by authors with no knowledge but a large audience - means that some more context is needed. From Jungian nonsense (with all due respect for Olga Tokarczuk, whose works I generally enjoy, her Anna In w grobowcach świata falls into this category) and weird attempts at elevating Ereshkigal well beyond the rank attributed to her in antiquity to a baffling attempt at understanding the myth in Nietzschean terms, Inanna’s Descent is arguably among the most tormented Mesopotamian literary texts, both online and offline.

To begin with, it’s important to place it in the context of Sumerian beliefs regarding proper care for the dead. As we can learn from a variety of sources, from myths to prayers to personal letters, the Sumerians viewed mourning and other related matters as incredibly important. Mourning was expressed in many forms, though particularly notable were funerary libations - you can find a reference to this even in the discussed myth: she offers generous libations at his wake, proclaims Inanna about the purported funeral of Ereshkigal’s supposed late husband. Elsewhere, the city of Enegi, associated particularly closely with the cult of the dead, is itself called the “libation pipe of the earth.”

Known texts stress that close family, such as spouses, siblings, or children, should be involved in funerary rites. As a matter of fact, from some texts we learn that the status of the dead in the underworld depends entirely on their close ones’ proper adherence to funerary customs.

The important role of family in mourning rites creates a problem for the narrative of Inanna’s Descent: Ninshubur is not exactly a family member. She is a courtier. While the “public figures” of ancient Mesopotamia were often mourned publicly by a large number of people, here the mourning seems to be private. As far as I understand - Ninshubur is essentially instructed to act as a family member would.

Following the usual genealogy of Inanna, there is no real place for Ninshubur on her family tree, as it is generally safe to assume Inanna’s parents are Nanna and Ningal, while she is herself childless. In fact, there is no strong indication Ninshubur was even conceptualized as part of a family tree in the first place. As noted by Frans Wiggermann, texts are largely silent about her parentage. To be fair this is not uncommon for servant deities, divine spouses (even the most prominent ones like Aya and Shala have no established genealogy!) and the like.

Curiously, Ninshubur’s mourning is described in very similar terms as that of Ningishzida’s wife Ninazimua in a composition possibly dealing with the former’s death, as Jeremy Black and Judith Pfitzner remarked in their respective articles about the composition Ningishzida and Ninazimua. Of course, this alone is not exactly a strong argument, as parallels can be drawn between these and the figures of mourning sisters and mothers in other texts dealing with deaths of gods. Still, it does appear to be somewhat of an outlier to have a servant, rather than a relative, express grief in such a composition.

It’s worth noting that while the only example we have is Inanna’s Descent, we know from preserved Sumerian catalogs of hymns and other similar compositions that there were a considerable number of currently lost texts which dealt with Ninshubur’s grief over something that happened to Inanna. Whether this was a different version of the story or some other, presently unknown, sorrowful event (perhaps banishment only known from an incredibly fragmentary text?) is impossible to tell.

A number of researchers, most recently Dina Katz, have proposed that Inanna’s Descent as we know it was in reality the result of combining multiple older narratives, as it only dates back to the Old Babylonian period. I speculate that the aforementioned unknown Ninshubur texts could perhaps have been predecessors to the version of the myth we see today.

Such a process of development was not uncommon for Mesopotamian myths. Both Epic of Gilgamesh and Enuma Elish are well known examples. Additionally, this theory explains the dissonance between the usual character of Dumuzi and his relationship with Inanna, known from countless love songs, and that presented in Inanna’s Descent.

Katz argues that this presently purely theoretical “original” did not feature Dumuzi - Inanna was saved by Ninshubur’s intervention and Enki’s trick alone, and the addition of a replacement for her seems superficial given the presence of “water of life” in the myth.

Inanna’s Descent wasn’t the only myth in which she appears which also served as explanation of Dumuzi’s death, as I already mentioned much earlier - in Inanna and Bilulu, for instance, she tracks down the killer instead (given the extreme level of violence, it would perhaps be fair to call the author a Sumerian Tarantino). At the same time, is somewhat unique in portraying Dumuzi’s death as being the result of his own shortcomings - something which probably indicates the compilers were more invested in Inanna than him, and that perhaps the goal was to merge as many different elements as possible into a coherent tale.

As a small digression I should note this is not the most negative portrayal of Dumuzi in known sources: late enigmatic lists of so-called “Seven Conquered Enlils” (in which the name is used just as a title, something like “lord”) place Dumuzi in the company of various well known mythical antagonists, like Tiamat, Asag or Mummu, not to mention the mysterious cosmogonic figure Enmesharra, whose disposition is generally villainous too, as seen for example in the text Enlil and Namzitara.

The change in focus from Inanna (or rather than equivalent of her) to Dumuzi only occurs in a very vague adaptation of Inanna’s Descent - the 1st millennium BCE Ishtar’s Descent. While Inanna’s Descent is known from nearly 50 copies, found anywhere from the major cities of Mesopotamia like Ur and Nippur to scribal schools located on the western periphery of the “cuneiform world,” the other myth has only a handful of them, all of exclusively Assyrian provenance. The myths are often conflated online, which leads to horrific misconceptions.

Katz argues that the latter myth represents an attempt at state revival of Dumuzi’s (or, to be more accurate, Tammuz’s, as the name was rendered in Akkadian) cult undertaken by the Neo-Assyrian Empire, which strikes me as a convincing argument. The change in focus is rather surprising, as the dying god par excellence, as noted by Berndt Alster, “did not belong to the leading deities in any period of Mesopotamian history” (unlike Ninshubur!).

A huge difference between Inanna’s Descent and Ishtar’s Descent is the absence of Ninshubur. In the latter myth, Papsukkal, a male messenger deity associated with Anu (and, at an early stage, with the war god Zababa, at home in Kish, modern Tell al-Uhaymir in central Iraq), makes an appearance instead, introduced not as a personal attendant of the heroine, but simply as a servant of the “great gods” collectively. What’s also missing are any references to the instructions regarding mourning and petitioning other gods on her behalf. Evidently, whatever factors resulted in the portrayal of Ninshubur in Inanna’s Descent did not apply to Papsukkal.

However, it’s important to stress that the very focus of Inanna’s Descent is different from that of Ishtar’s Descent. Dina Katz noted that while Ishtar’s Descent as a whole seems to be focused on the matter of very broadly understood fertility, “we cannot associate Inanna’s death and revival with procreation in nature nor with fertility in general,” contrary to what one can often read online. After all, fertility is a matter an agricultural deity would be much more concerned with, and Inanna’s Descent is ultimately not focused on Dumuzi and Geshtinanna, the only figures associated with agriculture in the original myth.

At the time when the new myth had most likely been composed, Ninshubur was hardly a relevant figure, having seemingly lost her relevance at some point during the Kassite period, in the mid to late second millennium BCE. However, it’s not like the first millennium Ishtar (the myth does not associate her with a specific location like Assur, Nineveh or Arbela) didn’t have a variety of female courtiers who could’ve made an appearance in the myth in her stead. A particularly notable example is the well-attested incorporation of Hurrian Ninatta and Kulitta, a duo of goddesses sharing a rather close relation in myths with Shaushka, the “Ishtar of Subartu” as she was sometimes called, into Assyrian Ishtar cults.

Coincidentally, there is no evidence for female scribes in the first millennium BCE, the time of the “translation’s” composition (I put that in quotation marks because while the text is often incorrectly labeled as such, it was actually, as outlined above, pretty much a new myth). Was this a factor in the evident change in sensibilities between Inanna’s Descent and Ishtar’s Descent? Hard to tell, but I personally would not rule it out.

To sum up: ultimately, what is important for the subject of the article are two facts about Inanna’s Descent:

1. Ninshubur acts as one would expect a family member

2. Her bond with Inanna is uniquely close

The evidence for the two points above does not start or end with Inanna’s Descent alone.

Beyond Inanna’s Descent: Ninshubur, sukkals and “wife goddesses”

Probably the strongest argument in favor of viewing Inanna and Ninshubur as uniquely close is the use of an uncommon synonym of the word sukkal, SAL.ḪUB2 (reading uncertain; the 2 should be subscript but tumblr doesn’t allow that, it seems), to refer to the latter. This term is very sparsely attested and only ever used to a handful of deities, exclusively sukkals, in all cases to indicate they are very closely associated with their divine “employers.” In addition to Ninshubur, it occurs for example in relation to Enlil’s sukkal Nuska, envisioned at times as a son of Enlil’s distant ancestors Enul and Ninul and a senior deity in his own right, and to Nabu, Marduk’s sukkal turned son turned pantheon head.

I sadly have no access to an article which apparently decisively established its meaning - Vizir, concubine, entonnoir... Comment lire et comprendre le signe SAL.ḪUB2? by Antoine Cavigneaux and Frans Wiggermann - but thanks to the help of a friend I was able to learn a few months ago that, in their words, the authors conclude that it denotes a sukkal “who is dear or intimate.”

This interpretation is presumably supported by the fact that in one of the few texts using this term (seemingly the one which is actually largely responsible for scholarly interest in establishing its meaning), Ninshubur is referred to as Inanna’s “beloved SAL.ḪUB2“ and appears among her family members - while her parents, brother, etc. are listed first, Ninshubur’s relation is seemingly more significant than that of in-laws in it, for what it’s worth. Other courtiers, like Nanaya, do not make an appearance.

One more possible source is a curiosity from the Hittite capital from Hattusa (located near modern village Boğazkale in central Turkey), specifically a ritual related to the goddess Pinikir. This is (tragically) not the time and place to discuss Pinikir in detail, but it will suffice to say that she was understood as reasonably Inanna- or Ishtar-like. While the text in mention comes from a Hurro-Hittite milieu (Hittites, relatively “young” by the standards of Ancient Near East, viewed Hurrian culture as prestigious), it was written in Akkadian, and it’s primarily concerned with an Elamite goddess, making it uniquely cosmopolitan.

Pinikir, whose name is spelled logographically as ISHTAR there, is invited to come alongside her family to receive offerings. She is described as the daughter of Nanna and Ningal and twin sister of Utu/Shamash; the other two figures invoked, Ea/Enki (addressed as “your [ie. Pinikir’s] creator”) and the goddess’ sukkal, instantly bring a variety of myths to mind (Descent, of course, but also Inanna and Enki and the less known Agushaya texts). The name of the sukkal, however, is Ilabrat, spelled syllabically. As far as I am aware, such a pairing is not attested anywhere else, and Ilabrat is generally speaking only Anu’s sukkal, unlike Ninshubur and even Papsukkal, who have multiple roles. While the researcher most involved in the study of this text, Gary Beckman, makes no such connection, I personally think it’s possible that a hypothetical forerunner to this late text featured Ninshubur.

Beckman on linguistic grounds concludes Hurrians likely adopted Pinikir, and a variety of rituals connected to her and her usual associate, the enigmatic deity DINGIR.GE6 (“Goddess of the Night”; reading of the name remains unknown; once again, the numer should be subscript, once again), from a Mesopotamian intermediary and not directly from Elam. He proposes that the transfer happened during the period of well-attested intense Sumero-Hurrian contacts in the late third or early second millennium BCE (the text in mention, meanwhile, is no older than the 14th century BCE, I believe). This, coincidentally, was also a time of immense interest in Ninshubur, including theological texts presenting her as one of the “great gods,” side by side with Enlil, Ninlil, Inanna, Ninurta and the like.

Perhaps much later on a Hittite scribe, not necessarily fully aware of Ninshubur’s existence (she was, after all, not really a deity of any relevance anymore in the late Bronze Age), worked with older Hurrian material which originally had Ninshubur in this role, but assumed the name is merely a logographic spelling of Ilabrat’s, a phenomenon attested in many locations in the Old Babylonian period? This is only my own, not necessarily valid, speculation, though.

Another curiosity is a text in which Inanna calls Ninshubur “mother” - this, however, is not a statement of actual kinship, but rather of respect. Senior gods of the pantheon are often called “father” or “mother” by other deities regardless of actual parentage. Such statements aren’t even necessarily reflections of alternate genealogies or anything of that sort. A good example can be found even just in Inanna’s Descent: Ninshubur addresses Enlil, Nanna and Enki this way, even though none of them are attested as her actual father (and only Nanna was regarded as Inanna’s father between these 3). Presumably Ninshubur’s recurring participation in Inanna’s adventures, and her capability to appease her or to “soothe her heart” was worthy of such reverence.

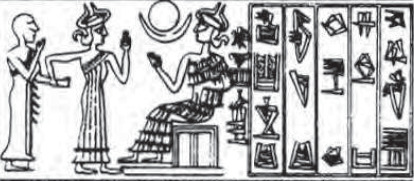

Impression of a cylinder seal depicting a mediating goddess, possibly Ninshubur as indicated by accompanying inscription (Goddesses in Context by J. M. Asher-Greve and W. G. Westenholz, p. 406; identified as such on p. 207)

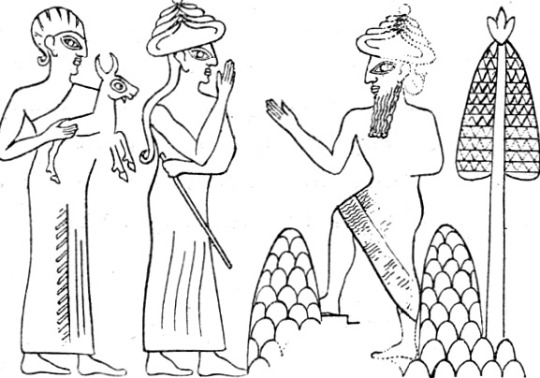

Impression of a cylinder seal possibly depicting Ninshubur (middle) interceding between governor of Lagash, Lugal-ushumgal, and the Akkadian king Shar-Kali-Sharri (wikimedia commons; goddess identified as Ninshubur in Goddesses in Context by J. M. Asher-Greve and W. G. Westenholz, p. 180)

The closeness between Inanna and Ninshubur wasn’t limited to texts of mythical nature, and had a very real religious dimension too. Ninshubur was a common object of popular devotion, appearing in personal names, in seal inscriptions, and in other similar sources because she was believed to be capable of mediating with Inanna (and with other deities as well, on the account of being a divine messenger and diplomat).

While a sukkal could act as a mediator in the cult of their master, most sukkals are deities with no personality, no individual role in myths and limited, if any popularity: for instance, Ishkur’s sukkal is simply the deified lightning, Nimgir. The difference between Ninshubur and Inanna and that which existed between most sukkals and their masters has been described by Frans Wiggermann as that between “command and execution” and “cause and effect.”

To my knowledge very few other sukkals maintained the degree of popularity Ninshubur enjoyed, a notable exception being Nuska. Both of them were listed among the “great gods” every now and then: for example, in a text from the reign of the Third Dynasty of Ur (as I already noted, seemingly a period of prosperity for Ninshubur) both appear side by side with Enlil, Ninlil, Nanna, Inanna, Ninurta, Nergal and Utu - the creme de la creme of the pantheon.

Ninshubur is also the only sukkal whose role I’ve seen compared to that of the “wife goddesses” (this is not a genuine scholarly term, I use it for simplicity’s sake). Julia M. Asher-Greve and Joan G. Westenholz specifically draw parallels between her role in Inanna’s cult with that played by Aya, the type specimen of the “wife goddesses” (her to-go epithet is quite literally “the bride,” kallatum) in the cult of Inanna’s solar twin. Of course, this does not indicate that she was ever seen as Inanna’s spouse - but it does at the very least show that it wouldn’t be entirely impossible to claim she was close to that status.

While there is no known evidence for Ninshubur status actually moving between that of wife and sukkal when it comes to Inanna, it should be noted that she, as a matter of fact, does move between these two roles in one very specific case. In the area of Lagash and Girsu (modern Al-Hiba and Telloh in Iraq), especially in the third millennium BCE, Ninshubur was associated with Nergal (well, Meslamtaea, as he was typically called in the south early on in Mesopotamian history). As remarked by Wilfred G. Lambert, Ninshubur in this context appears to show up both as sukkal and, unexpectedly, as Nergal’s wife (Nergal’s love life seems to be a rather complex matter). This is rather unique as Ninshubur was generally viewed as unmarried.

I don’t think Nergal is exactly similar to Inanna - though both deities share a warlike character - but this association, especially coupled with the modern observations regarding Ninshubur and Aya - does appear to support the idea that you could see Ninshubur likewise moving between status of sukkal and wife when it comes to Inanna. Especially taking into account that, as far as I am aware, it is only Inanna in relation to whom she gets to be a SAL.ḪUB2.

Ninshubur as the lesbian Enkidu?

One final point I’d like to make is that it is possible to make a number of comparisions between Ninshubur’s status to that of the only unambiguously attested gay love interest in Mesopotamian mythology, Enkidu.

A little discussed (outside scholarly circles, that is) aspect of the relationship between Gilgamesh and Enkidu which I’ve already mentioned early in the article is the fact that in the oldest sources do not yet present the latter as the “wild man” created to serve as a foil to Gilgamesh by the gods. Instead, he is the king’s courtier or servant, though a very close one - a status not too dissimilar from Ninshubur’s connection to Inanna in mythical context.

Obviously, the development from servant to cherished companion to lover was gradual, and presumably how the relationship was perceived varied too. Still, it’s worth stressing that while integral to Enkidu as a character in our modern perception, his origin story was actually a novelty compared to his position as Gilgamesh’s beloved, which predates the composition of a singular Epic of Gilgamesh. According to Andrew R. George, it’s possible that his newer “backstory” was meant to stress that to develop as a character Gilgamesh had to interact with a challenger completely from the outside of own sphere.

As a linguistic curiosity it’s worth mentioning that in the old standalone poems Enkidu’s position has been described in a few cases (for example in Gilgamesh and Akka or in Gilgamesh, Enkidu and the Netherworld) with the poetic term shubur-a-ni, which shares its etymology with Ninshubur’s name. “Shubur” is a term referring to the land also known as Subartu - the areas north of Mesopotamia, inhabited chiefly by Hurrians, or “Subarians,” as Mespotamians called them. However, it also acquired the meaning of “servant.”

You may therefore ask if Ninshubur was the “Lady of Subartu” in origin, perhaps a “Subarian” equivalent of the god Martu/Amurru who embodied traits associated with “Westerners” (that is, Amorites from Syria) or was she always just “Lady of Servants” as Frans Wiggermann interprets her name? That’s hard to tell. Nothing prevents her from being both at once, as acknowledged even by the aforementioned author, especially taking into account that Hurrians were present in Mesopotamia on all levels of society in the 3rd millennium BCE already. Speculating about her origin, fascinating as it is, ultimately is not the concern here.

Another prominent similarity between Enkidu and Ninshubur is that based on a variety of texts the latter fulfilled an important, rather specific role in Inanna’s life, serving as a source of good advice, a characteristic also well attested for Enkidu. In Gilgamesh, Enkidu and the Netherworld it is the loss of this advice that Gilgamesh laments after it turns out his friend cannot come back to life (a passage which George interprets as one of the early examples of the tradition according to which the two of them were in love). It should be noted that in Ninshubur’s case whether her advice was followed or not is a complicated matter - as we learn from one composition, one of Inanna’s abilities is knowing when to disregard both bad and good advice.

Finally, there is a less direct similarity. It is undeniable that Inanna and Gilgamesh both have heterosexual relationships with other characters, but Enkidu actually doesn’t in sources predating the development of his backstory, and I’ve already outlined Ninshubur’s marital status before. However, Inanna’s and Gilgamesh’s heterosexual relationships are not necessarily emphasized in compositions dealing with their adventures. It is instead their relationships with their respective “sidekicks” that commonly come to the forefront.

In Gilgamesh’s and Enkidu’s case, this requires no examples, as various episodes from the Epic are well known. Similarly, in addition to her role in Inanna’s Descent, Ninshubur also appears in the myth Inanna and Enki, where she likewise defends the eponymous heroine from any harm which may befall her - in this case at the hands of Enki’s guards, rather than underworld demons. Ninshubur also praises Inanna after the daring scheme appears to work, leading to the transfer of me (divine powers) to Uruk.

Finally, there is the myth known as Agushaya or, in older literature, Ea and Saltu. While the relations between specific deities in it generally speaking reflects the Sumerian texts which formed the base of the scribal curriculum in the Old Babylonian period, it is presently only known from Akkadian versions. What makes it somewhat of a curiosity is the presence of Ninshubur, otherwise almost exclusively present in literary texts written in Sumerian - perhaps a lost Sumerian original awaits us somewhere out there. While the text uses the name Ishtar to refer to the protagonist, her relation with Ninshubur mirrors Inanna’s in the two texts above.

Saltu (“Strife”), mentioned in the title, is essentially a hostile copy of the heroine, formed by Ea out of dirt from underneath his fingers (note the similarity to Enki’s preferred mode of creation in Inanna’s Descent). Ninshubur apparently provides her mistress with information about this new adversary, whose very appearance fills her with fear. It has been argued by Benjamin R. Foster that a set of odd scribal errors which recur in the passage is meant to be a unique way to render agitated stuttering. Sadly, the middle of the text is not preserved, making it impossible to tell if Ninshubur played any other role in it beyond that.

Closing remarks

The examples above do not show that anyone actually viewed Inanna and Ninshubur as a couple, and it is not my goal to prove decisively that anyone did at the time of the discussed texts’ composition. While obviously there definitely were women attracted to other women in every time and place (how was it expressed and whether modern labels could be easily applied to them is a different matter), it is ultimately not really possible to determine whether they left behind any indirect traces in Mesopotamian textual sources, and how to locate them.

The only point which I believe I’ve been able to prove above is that Ninshubur’s relationship with Inanna is uniquely close. As such, both this connection and Ninshubur’s character and broader role in Mesopotamian religion deserve more scholarly attention (can you believe there is no monograph on the concept of sukkal yet?) and more presence in the public perception of Mesopotamian mythology, and more specifically Inanna’s Descent

I do personally think there are grounds to debate whether there is subtext in the discussed myths. Even if it was not intended by their authors nearly 4000 years ago, it is hard to deny that from a modern perspective the implications are certainly there. If nothing else, discussing this topic could possibly make the study of relationships between women in ancient texts - not necessarily romantic ones, mind you - more prominent than it is now, both among academics and laypeople.

Additionally I think the discussed topic deserves exploration in fiction. As I’ve pointed out above, using the example of Gilgamesh and the reinterpretation of stories about him, certain aspects of myths could be emphasized or de-emphasized to match the expectations of new audiences, without the core of the story being lost. I think this still holds true.

Ultimately what I want to say is not “Ninshubur is clearly gay in Inanna’s Descent,” it’s “wouldn’t it be interesting to consider if she was, and whether the ancient sources make it viable?”

And that is the question I would like to leave you, the reader, with.

Bibliography

J. M. Asher-Greve, J. G. Westenholz, Goddesses in Context: On Divine Powers, Roles, Relationships and Gender in Mesopotamian Textual and Visual Sources

B. Alster, Inanna Repenting: The Conclusion of Inanna’s Descent - can’t vouch for the site this is hosted on, but it was originally published in a credible journal

B. Alster, Tammuz(/Dumuzi) (Reallexikon der Assyriologie entry)

G. Beckman, Babyloniaca Hethitica: The "babilili-Ritual" from Bogazköy (CTH 718)

G. Beckman, Gilgamesh in Hatti

G. Beckman, The Goddess Pirinkir and Her Ritual from Ḫattuša (CTH 644)

G. Beckman, When Heroes Love: The Ambiguity of Eros in the Stories of Gilgamesh and David (review)

J. Black, Ning̃išzida and Ninazimua

A. Cavigneaux, F. A. M. Wiggermann, Vizir, concubine, entonnoir... Comment lire et comprendre le signe SAL.ḪUB2?

M. Civil, Enlil and Ninlil: The Marriage of Sud

B. Dedovic, "Inanna's Descent to the Netherworld": A centennial survey of scholarship, artifacts, and translations

B. R. Foster, Ea and Saltu

A. Gadotti, Portraits of the Feminine in Sumerian Literature

A. George, The Babylonian Gilgamesh Epic: Introduction, Critical Edition and Cuneiform Texts

D. Katz, How Dumuzi Became Inanna's Victim: On the Formation of "Inanna's Descent"

D. Katz, Inanna's Descent and Undressing the Dead as a divine law

D. Katz, Myth and Ritual through Tradition and Innovation

D. Katz, Sumerian Funerary Rituals in Context

S. N. Kramer, Two British Museum iršemma "Catalogues"

W. G. Lambert, Babylonian Creation Myths - sadly not open access

W. G. Lambert, Introductory Considerations

A. Löhnert, Scribes and singers of Emesal lamentations in ancient Mesopotamia in the second millennium BCE

N. N. May, Female Scholars in Mesopotamia?

P. Michalowski, Emesal (Sumerian dialect) (The Encyclopedia of Ancient History entry)

P. Michalowski, Literacy in Early States: A Mesopotamianist Perspective

S. Nowicki, Women and References to Women in Mesopotamian Royal Inscriptions. An Overview from the Early Dynastic to the End of Ur III Period

J. Peterson, The Banishment of Inana

J. Peterson, UET 6/1, 74, the Hymnic Introduction of a Sumerian Letter-Prayer to Ninšubur (ZA 106)

J. Pfitzner, Ninĝišzida and Ninazimua, Nippur version l. 104 (=Ur version l. 40)

P. Pongratz-Leisten, Comments on the Translatability of Divinity: Cultic and Theological Responses to the Presence of the Other in the Ancient near East

E. Robson, Gendered literacy and numeracy in the Sumerian literary corpus

G. J. Selz, Female Sages in the Sumerian Tradition of Mesopotamia - careful with the final few paragraphs: the author is a bit too enthusiastic about the so-called “Helsinki school” which sees Mesopotamia as little more than source of dubious evidence for greater than in reality antiquity of specific currents in early Christianity and in broader gnostic tradition; for a criticism of the core ideas of the Helsinki school see this review by J. Cooper

T. Sharlach, Foreign Influences on the Religion of the Ur III Court

M. P. Streck, Nusku (Reallexikon der Assyriologie entry)

A. G. Ventura, Review of "Women's Writing in Ancient Mesopotamia. An Anthology of the Earliest Female Authors" (Charles Halton & Saana Svärd, 2018)

M. Viano, The Reception of Sumerian Literature in the Western Periphery

G. Whittaker, Linguistic Anthropology and the Study of Emesal as (a) Women's Language - note that some of Whittaker’s other writing on Sumerian language is dubious at best (especially his quest for an “Indo-European substrate” in it; for overview of theories about substrates in Sumerian and explanation why they are faulty see On the Alleged "Pre-Sumerian Substratum" by G. Rubio); I am merely using this article as a point of reference for information about Enheduanna’s writing

F. A. M. Wiggermann, An Unrecognized Synonym of Sumerian Sukkal

F. A. M. Wiggermann, Nergal A. Philological (Reallexikon der Assyriologie entry)

F. A. M. Wiggermann, Nin-šubur (Reallexikon der Assyriologie entry)

F. A. M. Wiggermann, Sexuality A. In Mesopotamia (Reallexikon der Assyriologie entry) - do not take it at face value though, at least one of the sources is pretty much a nightmare, make sure to read a critical review by A. R. George

114 notes

·

View notes

Text

mhm

And not just monkeys.

A favorite refrain of mine is to acknowledge how the stereotypical image of Southwest Asia as a place “of deserts” is, really, a recent historical thing. The region’s “Fertile Crescent” label was well-deserved. The region was a meeting-place, where animals typically associated with both Africa and Asia mingled.

Before the first millennium, hippopotamus and sacred crocodile (Crocodylus suchus) would’ve still lived in lower Egypt near the eastern Mediterranean. There was a now-extinct subspecies of ostrich which lived in the eastern Mediterranean and Arabian peninsula. It’s possible/probable that Asian elephants (Elephas maximus) historically lived along the northern coast of the Persian Gulf westward towards Media. In the medieval era, the Caspian tiger still lived in Anatolia and the shores of the Black Sea near Crimea and the Ukrainian steppes.

As recently as the early 20th century, Anatolia, the eastern Mediterranean, and Mesopotamia were still home to cheetah, leopard, caracal, lions, and tigers all living, basically, alongside or very near each other.

This excerpt -- about the cedar, forests, and biomass of the Fertile Crescent, and the massive impact of human devegetation and empire-building -- left a big impression on me:

-------

Alexander von Humboldt noted that while one “might easily be led to adopt the erroneous inference that the absence of trees is a characteristic of hot climates ... civilization sets bounds to the increase of forests and the youthfulness of a civilization is proved by the existence of the woods.” [...]

While some texts simply allude to environmental degradation, such as the Sumerian gardener Shukallituda’s experimentation with agroforestry in the wake of deforestation ... others contain explicit description of forest clearance, including the claim of Gudea of Lagash (2141-2122 BC), who “made a path” into the forest, “cut its cedars,” and sent cedar rafts floating “like giant snakes:” down the Euphrates” [...].

Despite declining biological diversity and productivity, the annals of Ashurnasirpal II [king of Assyria from 883 to 859 BC] describe abundant wildlife and a substantial inventory of domesticated livestock. He claimed to have slain 450 lions, killed 390 wild bulls, decapitated 200 ostriches; caught thirty elephants in pitfalls; and captured alive fifty wild bulls, 140 ostriches, and twenty adult lions. In addition, he received five live elephants as tribute, and “organized herds of wild bulls, lions, ostriches, and male and female monkeys.” At a banquet on the occasion of the inauguration of the palace at Kalhu (biblical Calah), his 69,574 guests dined on 1200 head of cattle and 1000 calves; 11,000 sheep and 16,000 lambs; 500 stags; 500 gazelles; 1000 ducks; 1000 geese; 1000 mesuku birds, 1000 qaribu birds, 20,000 doves, and 10,000 other assorted small birds; 10,000 assorted fish; and 10,000 jerboas - along with enormous quanitites of beer and wine, milk, cheese, eggs, bread, fruit and vegetables, and a vast number of other offerings. [...]

By the dawn of the first millennium AD, much of the wildlife of the steppes had been displaced by herds of livestock. The numbers were impressive. For example, in AD 222 the Xianbei (Hsien-pi) sold 70,000 horses to the Kingdom of Wei. In 1241, across the continent, Hungarians (Keler) are said to have opposed the Mongols under Batu Khan with a force of 400,000 horsemen. [...]

The pattern is familiar: An invasive plant, perhaps Ageratina adenophora, enters an environmental system in dynamic equilibrium. It brings with it novel chemical weapons that disrupt the equilibrium of the native community, allowing it to dominate the disturbed community. [...] Hence, many Indigenous societies were disrupted, reconfigured, and dominated prior to formal colonial annexation. The costs of declining biological and cultural diversity are well documented, as are the costs of disturbance and domination in natural and social systems.

A Sumerian epic tale, ‘Emmerkar and the Land of Aratta,’ describes an earlier state of peace and security, ending with man’s fall from grace. Descent into chaos is described in the epic, ‘Lamentation over the Destruction of Sumer and Ur.’ In Western Asia, patterns of [ecological] disturbance and [social] domination emerge with the complex interplay of ascendant Egyptian, Caucasian, Semitic, Indo-European, and Dravidian aristocracies in the fifth millennium BC – patterns that cascade through history.

Owing in part to the Western idea of ‘progress,’ sequential changes, even if non-adaptive, are often viewed as markers on an evolutionary journey from a primitive past to an eventual state of perfection. In retrospect, it is clear that many ‘advances’ were simply measures that compensated for altered social relationships or [environmental] maladaptation, or conferred strategic advantage.

-------

Source: Jeffrey A. Gritzner. “Environment, Culture, and the American Presence in Western Asia: An Exploratory Essay.” 2010.

336 notes

·

View notes

Text

Statue of King Gudea; dolerite; Tello, Iraq; 2130BC

Courtesy Alain Truong

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ningishzida

Mesopotamian god of the tree of wisdom

Ningishzida’s name means "Lord of the Good Tree", which is also known as “The Tree of Death”. It is this sacred tree that grants wisdom once eaten from, causing a “death” to one’s ignorance and a rebirth through knowledge. This tree is also an entrance to the Underworld, since wisdom comes from allowing one’s current self to die. Its sister-tree is the “Tree of Life” which is equivalent to Yggdrasil.

In depictions, Ningishzida is shown as either a large serpent, a serpent with the head of a man, a crowned man with snakes coming from his shoulders, or as a double-headed serpent that is coiled into a double helix. This last representation makes him the first appearance of the caduceus symbol, predating the one shown with Hermes and Asclepius in Greece. In another depiction, Ningishzida is shown beside the Tree of Death (a unique tree that is shown bearing some sort of fruit), along with two griffins, which are divine protectors. Ningishzida is also associated with dragons, the mušhuššu and balm. He is also referred to as a snake, (muš-mah, meaning “exalted serpent”). Due to these, he is moreso a serpentine-dragon, rather than just a serpent.

Myths: In mythology, Ningishzida is one of the deities thought to travel to the Underworld (Kur) during the dead seasons (mid-summer to mid-winter); the other deity being Dumuzi. These two gods are also featured in the myth of Adapa, one of the first humans. When Adapa is commanded to arrive before Anu, god of the heavens, after speaking a curse to break the south wind, he sees both Ningishzida and Dumuzi placed as guards for Anu’s celestial palace. As for Ningishzida's chthonic connections, a title of his is “gu-za-lá-kur-ra” (the chair-bearer of the netherworld). He is also the overseer for the twin-gods who guard the gates of the Underworld: Lugal-irra and Meslamta-ea. An additional role of his is being involved with divine law in both the Underworld and on Earth, making him a guardian/overseer of many things.

The Tree of Death had also been linked with the serpent or dragon (winged serpent) for over 1,000 years before Genesis was written. In 2025 BC, the cup of the Sumerian King Gudea of Lagash showed two winged dragons holding back a pair of opening doors to reveal a caduceus of uniting snakes, the incarnation of the god Ningishzida, to whom the cup is inscribed: “Lord of the Tree of Truth”. In northern Babylonia the goddess who embodied the Tree of Wisdom was called the “Divine Lady of Eden” or “Edin”, and in the south she was called the “Lady of the Vine”, an understandable change of name given that the Sumerian sign for ‘life’ was originally a vine leaf.

Appearance: Ningishzida is an enormous serpent with yellow eyes and a body that is over 30 meters in length. His body is made out of black Sumerian syllables that shift all around his form, due to his power of words. He also has shimmering black plumes on his head and around his neck. While his form is that of a great serpent, he is a species of dragon and has similar abilities to them.

Personality: Ningishzida is reserved, serious, highly intelligent and wise, honest, diligent, intuitive, and deeply loyal. He is a highly respectable being and seeks to teach promising humans of true wisdom and knowledge. He has said that the path to true wisdom is a painful one and very few make it; yet those who do are fully reborn. Just like a serpent, they must shed themselves and become anew. Although the majority of humans do not impress him anymore; he wishes to work only with those who fully love truth and are willing to achieve spiritual evolution despite the strife it costs. He dislikes laziness, pretentiousness, cruelty, stubbornness, and those who prefer to believe lies in order to be comfortable. Ningishzida has also stated that he is neither Lucifer nor Satan, or any other demon; he teaches very similar things as Lucifer and is on good terms with him, but they are not the same. Overall, Ningishzida is a god of vast knowledge and wisdom who seeks to bring enlightenment to those who prove themselves worthy to him.

The Story of the Tree of Death: Ningishzida has described that the tree mentioned in Biblical texts is indeed his own tree, but the actual event was much different than described. He tells that when humans were being created, it was done so through guided evolution. The birth-place of the final result for humanity took place within several gardens full of life upon Earth, such as Dilmun and Eden (e-din: “the land between two rivers”; i.e. a location within Mesopotamia). When the humans were created within these sacred gardens, they were not actually created in pairs, but as large groups. This is because there is no possible way that two humans alone could populate the Earth. Once these humans were created, they were often visited by certain deities (such as Enki, their creator), as well as some dragons. The dragons are a race of beings who possess advanced intelligence and wisdom, many of them are also deities. These beings all came to the humans in order to teach them and show them how to become independent. One such mentor to the humans was the serpentine-dragon himself, Ningishzida, who guarded the Tree of Wisdom.

These gardens of paradise were select areas upon Earth that were enhanced with magickal fields due to divine pillars the deities had placed within. This caused the gardens to be otherworldly in their beauty, with plenty of food, water, and even luminescent architectures where the humans could live. The Tree of Death is a divine tree of otherworldly beauty that was projected into each of these sacred gardens, each one being protected by Ningishzida. These gardens were to serve as temporary dwelling places for the new humans, allowing them to be closely mentored until they were fully ready to become independent. Once a human made it far enough in their training, Ningishzida would allow them to eat from his tree and become truly wise.

However, the tyrant Aeon god, Jehovah, sought to take Earth as his own by manipulating mankind. He managed to convince many humans that they were being held captive in these gardens and that eating from the Tree of Death meant literal death, in order to prevent them from becoming wise. Due to this, very few humans got to eat from the fruits of wisdom. Thinking that their mentors had been corrupting them all along, the humans prematurely left from the gardens and convinced others to do the same. Once many had left, the humans gradually began to realize how difficult surviving on Earth actually was and tried to enter one of the remaining gardens. But in order to keep the humans inside this garden safe, the deities prevented them from entering and guarded the entrances with flaming swords. In a rage, the humans attacked the divine pillars of all the gardens, causing them to lose their magick essences. The gardens of paradise thus lost their power and became nothing but regular places of nature, eventually being absorbed into the rest of the landscape.

Believing the lies of Jehovah that the fruits had condemned them all to a painful fate, the humans placed the blame on Ningishzida and the rest of the dragons. They raged at their old mentors and cursed their names. It did not take long until the humans began hunting down the dragons in order to kill them, though only succeeding a few times. This act of treachery greatly angered the draconic beings and eventually, they abandoned the humans to completely fend for themselves on Earth. All because of the coaxing of Jehovah, a long history began of humans portraying the dragons as evil and selfish, whereas humans are their victims. However, the humans who had remained in the gardens did not end up following Jehovah, which allowed them to pass down an actual record of the divinities and how Ningishzida represents truth. Unfortunately, a lot of the records were eventually destroyed by zealots and this act of giving wisdom was twisted into meaning something “evil” for many people. Overtime, this account was reformed and simplified into the Abrahamic texts (along with plenty of other Mesopotamian myths). The humans “Adam and Eve” are representations of humanity overall, and the giver of wisdom, Ningishzida, is portrayed as a devil.

Devotional actions: Ningishzida mainly prefers offerings of action over physical offerings. He can be honoured through actions such as gaining knowledge, overcoming your Ego so wisdom can develop, making mystical pilgrimages for enlightenment, seeking deeper meaning of yourself, and allowing the struggles of life to transform you for the better.