#Lovely illustration of young Napoleon Bonaparte

Text

Happy Closing NPGC1812/SJPlayhouse

“Natasha, Pierre, and the Great Comet of 1812”

"The Great Comet of 1812," also known as "Natasha, Pierre & The Great Comet of 1812," is a musical based on a section of Leo Tolstoy's novel "War and Peace." It premiered off-Broadway in 2012 and later moved to Broadway in 2016. The musical, written by Dave Malloy, tells a story set in Moscow during 1812, focusing on the intertwining lives of several characters.

The protagonist, Natasha, is a young, vibrant woman engaged to Andrey, who is away at war. While Andrey is absent, Natasha falls into a passionate affair with Anatole, a dashing rogue. Meanwhile, Pierre, Andrey's close friend, is going through a personal crisis, searching for meaning and purpose in his life. As the comet approaches, the characters' lives become increasingly entangled, leading to dramatic and emotional consequences.

“The Great Comet of 1812" is known for its innovative staging, which includes immersive theater elements, audience interaction, and a unique blend of musical genres ranging from classical to folk and rock. The show incorporates a diverse cast and showcases a fusion of Russian and contemporary influences in its music and storytelling.

The musical explores themes of love, fate, and the human condition, capturing the spirit of Tolstoy's epic novel within a condensed and stylized narrative. It features memorable songs such as "No One Else," "Sonya Alone," and "Dust and Ashes," which delve into the characters' inner struggles and desires.

Overall, "The Great Comet of 1812" offers a theatrical experience that combines spectacle, intimate storytelling, and a vibrant score to create a unique and immersive journey through 19th-century Russia, highlighting the emotional complexities and conflicts of its characters.

Based on a portion of “War and Peace”

"War and Peace" is a sprawling novel that tells the story of several interconnected characters against the backdrop of the Napoleonic Wars. The narrative revolves around the lives of five aristocratic families: the Bezukhovs, the Bolkonskys, the Rostovs, the Kuragins, and the Drubetskoys.

The protagonist, Pierre Bezukhov, is a young, illegitimate man who unexpectedly inherits a vast fortune. He struggles to find meaning in his life and gets involved in the intellectual and freethinking circles of Moscow. Pierre's journey leads him to question his beliefs, seek enlightenment, and eventually find love.

Prince Andrei Bolkonsky, a close friend of Pierre's, is initially filled with ambition and seeks glory on the battlefield. However, his experiences in war, including his capture and injury, change him profoundly, leading him to reassess his values and find solace in family life.

Natasha Rostova, a young and vivacious girl, becomes the center of attention for many suitors, including Prince Andrei. Her journey involves youthful exuberance, romantic entanglements, and personal growth as she navigates the complexities of love, society, and her own desires.

The novel also explores the impact of war on individuals and society as a whole, highlighting the chaos, suffering, and destruction that accompanies armed conflicts. Tolstoy provides a panoramic view of the battlefield, illustrating the human cost of war through vivid and harrowing descriptions.

Amidst the war and tumult, Tolstoy delves into philosophical and existential questions, examining the nature of freedom, fate, and the pursuit of happiness. Through its extensive character development, intricate relationships, and historical context, "War and Peace" offers a profound exploration of human existence and the complexities of life.

Napoleonic Wars

The Napoleonic Wars were a series of conflicts that took place from 1803 to 1815, primarily involving the French Empire under the leadership of Napoleon Bonaparte and various coalitions of European powers. The wars had far-reaching consequences and significantly reshaped the political landscape of Europe.

Napoleon, a skilled military strategist and charismatic leader, rose to power in France following the French Revolution. He sought to expand French influence and control across Europe, ultimately aiming for continental dominance. The Napoleonic Wars can be divided into several distinct phases:

1. War of the Third Coalition (1803-1806): This phase saw France facing a coalition of Austria, Russia, and Britain. Napoleon achieved significant victories, including the decisive Battle of Austerlitz in 1805, leading to the dissolution of the Third Coalition.

2. War of the Fourth Coalition (1806-1807): Napoleon's forces defeated Prussia and other German states in the Battle of Jena-Auerstedt. He also successfully campaigned against Russia, culminating in the Treaty of Tilsit, which established French influence over continental Europe.

3. Peninsular War (1808-1814): This conflict began when Napoleon's forces invaded Spain and Portugal, triggering a guerrilla resistance. The British, led by the Duke of Wellington, supported the Spanish and Portuguese against French occupation, ultimately resulting in Napoleon's costly defeat in the Iberian Peninsula.

4. War of the Fifth Coalition (1809): Austria, seeking to regain lost territories, launched a campaign against France. Although the Austrians initially achieved some successes, Napoleon emerged victorious in the Battle of Wagram, leading to the Treaty of Schönbrunn and French control over most of Central Europe.

5. Invasion of Russia (1812): Napoleon's ill-fated attempt to invade Russia resulted in a disastrous retreat due to harsh winter conditions, Russian guerrilla warfare, and strategic withdrawals. The Russian campaign significantly weakened the French Empire and boosted the morale of other European powers.

6. War of the Sixth Coalition (1813-1814): Prussia, Russia, Sweden, Austria, and Britain formed a coalition against Napoleon. The coalition achieved victories at the Battles of Leipzig and Waterloo, leading to Napoleon's abdication and his exile to the island of Elba.

7. Hundred Days (1815): Napoleon briefly returned to power in France but was defeated by the British and Prussian forces at the Battle of Waterloo. He was subsequently captured and exiled to the remote island of Saint Helena, where he died in 1821.

The Napoleonic Wars marked a significant era of conflict, territorial changes, and power struggles in Europe. They had profound political, social, and military implications, ultimately contributing to the downfall of Napoleon and the restoration of a more conservative balance of power in Europe.

Russia and Ukraine

The Napoleonic Wars, as mentioned earlier, took place from 1803 to 1815 and involved Napoleon Bonaparte's French Empire and various coalitions of European powers. These wars were driven by Napoleon's ambition for French expansion and control over Europe, as well as the resistance and geopolitical interests of other European nations. The conflict had broad implications for the balance of power in Europe and resulted in significant territorial changes.

On the other hand, the current conflict between Russia and Ukraine began in 2014 with Russia's annexation of Crimea and the subsequent unrest in eastern Ukraine. The roots of this conflict can be traced back to political, ethnic, and historical factors, including issues of national identity, governance, and geopolitical tensions between Russia and Western-leaning Ukraine. The conflict has involved military confrontations, separatist movements, economic sanctions, and diplomatic efforts to resolve the situation.

While both conflicts involve warfare and geopolitical maneuvering, it is essential to note the differences in their contexts, motivations, and historical circumstances. The Napoleonic Wars were part of a broader struggle for dominance in Europe during the 19th century, while the Russia-Ukraine conflict is a contemporary issue rooted in complex regional dynamics and modern geopolitical considerations.

“Natasha, Pierre, and the Great Comet of 1812” is currently playing at San Jose Playhouse and must close on June 4. For tickets go to https://sanjoseplayhouse.org/great-comet/

https://sanjoseplayhouse.org/great-comet/

The cast of “Great Comet” are:

Paloma Maia Aisenberg as Natasha

Corey Bryant as Balaga

Osher Fine is Princess Mary

Stephen Guggenheim as Pierre

Susan Gundunas as Marya D

Juanita Harris as Helene

Annie Hunt as Sonya

Jared Lee as Anatole

F. James Raasch as Old Prince Bolkonsky/Prince Andrey

Nicholas Rodrigues as Dolokhov

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Vivant, il a manqué le monde ; mort, il le possède.

- François René de Chateaubriand (1768-1848), Vie de Napoléon, livres XIX à XXIV des Mémoires d’outre-tombe (posthume)

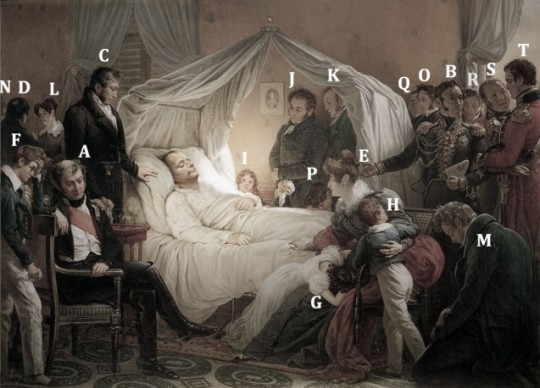

Of course we don’t have any photograph or film of Napoleon’s death on 5 May 1821 on Saint Hélène. But we do have the next best thing: a painting. Charles de Steuben depiction of Napoleon's deathbed and his faithful entourage that served as witnesses to his dying moments became the one of the most important paintings of the post-Napoleonic era but then faded from modern memory.

I first came across it by accident when I was in my teens at my Swiss boarding school. There were times I found myself with school friends going away on hiking trips around the high Alpine chain of the Allgäu Alps and we would drive through Lake Constance to get there, or we would hike around the Lake itself through the Bodensee-Rundwanderweg.

Perched high above Lake Constance and nestled in large parklands, stood Schloss Arenenberg which overlooks the lower part of Lake Constance. At first, it appears a relatively modest country house. But this was no usual pretty looking house. Arenenberg was owned by well-heeled families before it was sold to Hortense de Beauharnais, the adopted daughter and sister-in-law of the French Emperor himself, Napoleon Bonaparte. She had it rebuilt in the French Empire style and lived there from 1817 with her son Louis Napoleon, later Emperor Napoleon III, who is said to have spoken the Thurgau dialect in addition to French. This elegantly furnished castle then was once the residence of the last emperor of France.

The alterations made first by Queen Hortense and later by Empress Eugénie have been carefully preserved and the house still bears the marks of both women. Queen Hortense's drawing room is perfectly preserved and visitors can still admire her magnificent library (all marked with the Empress' cipher) containing over one thousand books. Likewise, in the room where the queen died, every object has been maintained in its original condition: pieces of furniture and personal belongings are gathered here to evoke her memory in a very touching manner. As for Empress Eugénie's rooms, they too have been very carefully preserved. Her private drawing room is a perfect illustration of the Second Empire style with sculptures by Carpeaux and portraits of the imperial family by Winterhalter.

After 1873, the Empress and the Imperial Prince brought the palace back to life by making regular summer visits, which they continued until 1878. However, on the tragic death of her son in 1879, Eugénie found it difficult to return to a place so full of painful memories. And so in 1906 she donated the estate to the canton of Thurgovie as a testimony of her gratitude for the region's faithful hospitality towards the Napoleon family. And in accordance with the Empress' wishes, the residence was turned into a museum devoted to Napoleon.

In what is now the Napoleonic Museum, the original furnishings have been preserved, and the palace gardens had been fully restored. This in itself might be worth a visit for the view over Lake Constance which is stunning. For Napoleonic era buffs though its the incredible art collection which is its real treasure. It houses an important art collection including works by the First-Empire artists Chinard Canova, Gros, Robert Lefèvre, Gérard, Isabey and Girodet-Trioson, and by the Second-Empire painters and sculptors Alfred de Dreux, Winterhalter, Carpeaux, Meissonier, Hébert, Flandrin, Detaille, Nieuwerkerke and Giraud.

But what caught my eye was this painting, ‘La Mort de Napoléon’ by Charles de Steuben. I didn’t know anything about it or the artist for that matter, but one of my more erudite school friends who, being French, was into Napoleonic stuff in a huge way, and she explained it all to me. Of course I knew a fair bit about Napoleon growing up because my grandfather and father, being military men themselves, were Napoleonic warfare buffs and it rubbed off onto me. I just knew about Napoleon the military genius. I never thought about him once he was beaten at Waterloo in 1815. So I never really engaged with Napoleon the man. And yet here I was staring at his last breath of mortality caught forever in time through art. Not for the first time I had mixed feelings about Napoleon Bonaparte, both the man and the myth (built up around him since his death).

On 5 May, 1821, at 5.49pm in Longwood House on the remote island of St Helena, in the words of the famed French man of letters, François-René de Chateaubriand, ‘the mightiest breath of life which ever animated human clay’ came no more. To the British, Dutch, and Prussian coalition who had exiled Naopleon Bonaparte there in 1815, he was a despot, but to France, he was seen as a devotee of the Enlightenment.

In the decade following his demise, Napoleon’s image underwent a transformation in France. The monarchy had been restored, but by the late 1820s, it was growing unpopular. King Charles X was seen as a threat to the civil liberties established during the Napoleonic era. This mistrust revived Napoleon’s reputation and put him in a more heroic light.

Fascination with the French leader’s death led Charles de Steuben, a German-born Romantic painter living in Paris, to immortalise the momentous event. Steuben’s painting depicts the moment of Napoleon’s death and seeks to capture the sense of awe in the room at the death of a man whose legendary career had begun in the French Revolution. It was this, ultimate moment that Steuben wished to immortalise in a painting which has since become what could almost be described as the official version of the scene.

There is no question that Steuben’s painting became the most famous and most iconic depiction of Napoleon’s death in art history. In another painting, executed during the years 1825-1830, Steuben was to give a realistic view of the emperor dictating his memoirs to general Gourgaud. This same realism also pervades his version of Napoleon’s death, and it is totally unlike Horace Vernet’s, Le songe de Bertrand ou L’Apothéose de Napoléon (Bertrand’s Dream or the apotheosis of Napoleon) which, although painted in the same year, is an allegorical celebration of the emperor’s martyrdom and as such the first stone in the edifice of the Napoleonic legend.

And what a legend Napoleon’s life was turned into for time immemorial. Napoleon declared himself France’s First Consul in 1799 and then emperor in 1804. For the next decade, he led France against a series of European coalitions during the Napoleonic Wars and expanded his empire throughout much of continental Europe before his defeat in 1814. He was exiled to the Mediterranean island of Elba, but he escaped and briefly reasserted control over France before a crushing final defeat at the Battle of Waterloo in 1815.

Napoleon’s military prowess earned him the fear of his enemies, but his civil reforms in France brought him the respect of his people. The Napoleonic Code, introduced in 1804, replaced the existing patchwork of French laws with a unified national system built on the principles of the Enlightenment: universal male suffrage, property rights, equality (for men), and religious freedom. Even in his final exile on St. Helena, Napoleon proved a magnetic presence. Passengers of ships docked to resupply would hurry to meet the great general. He developed strong personal bonds with the coterie who had accompanied him into exile. Although some speculate that he was murdered, most agree that Napoleon’s death in 1821, at the age of 51, was the result of stomach cancer.

By contrast, Charles de Steuben was born in 1788, his youth and artistic training coinciding with Napoleon’s rise to power. He was the son of the Duke of Württemberg officer Carl Hans Ernst von Steuben. At the age of twelve he moved with his father, who entered Russian service as a captain, to Saint Petersburg, where he studied drawing at the Art Academy classes as a guest student. Thanks his father's social contacts in the court of the Tsar, in the summer of 1802 he accompanied the young Grand Duchess Maria Pavlovna of Russia (1786–1859) and granddaughter of Frederick II Eugene, Duke of Württemberg, to the Thuringian cultural city of Weimar, where the Tsar's daughter two years later married Charles Frederick, Grand Duke of Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach (1783–1853). Steuben, then fourteen years old, was a Page at the ducal court, a position for which the career prospects would be in the military or administration. The poet Friedrich Schiller was a family friend who at once recognised De Steuben's artistic talent and instilled in him his political ideal of free self-determination regardless of courtly constraints.

At the behest of Pierre Fontaine in 1828 de Steuben painted La Clémence de Henri IV après la Bataille d'Ivry, depicting a victorious Henry IV of France at the Battle of Ivry. De Steuben's Bataille de Poitiers, en octobre 732, painted between 1834 and 1837, shows the triumphant Charles Martel at the Battle of Tours, also known as the Battle of Poitiers. He painted Jeanne la folle around the same time and he was commissioned by Louis Philippe to paint a series of portraits of past Kings of France.

Life in the French capital was a repeated source of internal conflict for Steuben. The allure of bohemian Paris and his military-dominated upbringing made him a wanderer between worlds. As an official commitment to his adopted country he became a French citizen in 1823. However, the irregularity of his income as a freelance artist was in contrast to his sense of duty and social responsibility. To secure his family financially, he took a job as an art teacher at École Polytechnique, where he briefly trained Gustave Courbet. In 1840 he was awarded a gold medal at the Salon de Paris for his highly acclaimed paintings.

The love of classical painting was a lifelong passion of Steuben. He was a close friend to Eugène Delacroix, the leader of the French Romantic school of painting, whom he portrayed several times. Steuben was also part of this artistic movement, which replaced classicism in French painting. "The painter of the Revolution," as Jacques-Louis David was called by his students, joined art with politics in his works. The subjects of his historical paintings supported historical change. He painted mainly in sharp colour contrasts, heavy solid contours and clear outlines. The severity of this style led many contemporary artists - including Prud'hon - to a romanticised counter movement. They preferred the shadowy softness and gentle colour gradations of Italian Renaissance painters such as Leonardo da Vinci and Antonio da Correggio, whose works they studied intensively. Steuben, who had begun his training with David, felt the school was becoming increasingly rigid and dogmatic. Critics praised his deliberate compositions, excellent brush stroke and impressive colour effects. But some of his critics felt that his pursuit of dramatic design of rich people also showed, at times, a pronounced tendency toward the histrionic.

The portrayal of key moments in Napoleon’s dramatic military career would feature among some of Steuben’s best known works. But it is this death scene that Steuben is most remembered for.

Using his high-level contacts among figures in Napoleon’s circle, Steuben interviewed and sketched many of the people who had been present when Napoleon died at Longwood House on St. Helena. He wanted to attempt o give the most accurate representation of the scene possible. Indeed, the painter interviewed the companions of Napoleon’s captivity on their return to France and had them pose for their portraits. Only the Abbé Vignali, captain Crokat and the doctor Arnott were painted from memory. The Grand maréchal Bertrand made sketches of the plan of the room, noting the positions of the different pieces of furniture and people in the room. All the protagonists within the painting brought together some of their souvenirs and in posing for the painter, each person can be seen contributing to a work of collective memory, very much with posterity in mind.

Painstakingly researched, Steuben painted a carefully composed scene of hushed grief. Notable among the figures are Gen. Henri Bertrand, who loyally followed Napoleon into exile; Bertrand’s wife, Fanny; and their children, of whom Napoleon had become very fond.

The best known version of “La Mort de Napoléon” was completed in 1828. French writer Stendhal considered it “a masterpiece of expression.” In 1830 the installation of a more liberal monarchy in France further boosted admiration of Napoleon, who suddenly became a wildly popular figure in theatre, art, and music. This fervour led to the diffusion of Steuben’s deathbed scene in the form of engravings throughout Europe in the 1830s. As Napoleon’s stock arose within French culture and arts, so did Steuben’s depiction of Napoleon’s death. It became a grandeur of vision that permeated Steuben’s masterpiece of historical reconstruction.

Initially forming part of the collection of the Colonel de Chambrure, the painting was put up for auction in Paris, on 9 March 1830, with other Napoleonic works, notably Horace Vernet’s Les Adieux de Fontainebleau (The Fontainebleau adieux) and Steuben’s Retour de l’île d’Elbe (The return from the island of Elba). The catalogue noted that the painting had already been viewed in the colonel’s collection by “three thousand connoisseurs” – which alone would have made it a success -, but its renown was to be further amplified by the production of the famous engraving. The diffusion of this engraving by Jean-Pierre-Marie Jazet (1830-1831, held at the Musée de Malmaison), reprinted and copied countless times throughout the 19th century, made the scene a classic in popular imagery, on a level of popularity with paintings such as Millet’s Angelus.

A / Grand Marshal Henri-Gatien Bertrand. Utterly loyal servant of Napoleon’s to the last. His memoirs of the exile on St Helena were not published until 1849. Only the year 1821 has ever been translated into English.

B / General Charles Tristan de Montholon. Courtier and companion of Napoleon’s exile. Montholon managed to ease Bertrand out and become Napoleon’s closest companion at the end, highly rewarded in Napoleon’s will, which Montholon helped write. Montholon’s untrustworthy memoirs were published in 1846/47.

C / Doctor Francesco Antommarchi. Corsican anatomy specialist. Sent by Napoleon’s mother from Rome to St Helena to be Napoleon’s personal physician on the expulsion of Barry O’Meara. Napoleon disliked and distrusted Antommarchi. Antommarchi’s untrustworthy memoirs were very influential and published in 1825.

D / Angelo Paolo Vignali, Abbé. Corsican assistant-chaplain, sent by Madame Mère from Rome to St Helena in 1819.

E / Countess Françoise Elisabeth “Fanny” Bertrand and her children: Napoléon (F), who carried the censer at Napoleon’s funeral; Hortense (G); Henry (H); and Arthur (I), youngest by six years of all the Bertrand children and born on the island. She was wife of the Grand Marshal, very unwilling participant in the exile on St Helena. Her relations with Napoleon were difficult since she refused to live at Longwood. She spoke fluent English. Was however very loyal to Napoleon.

J / Louis Marchand. Napoleon’s valet from 1814 on and one of his closest servants. As Napoleon noted in his will, “The service he [Marchand] rendered were those of a friend”.

K / “Ali”, Louis Étienne Saint-Denis. Known as “the Mamluk Ali”, one of Napoleon’s longest-serving and intimate servants; He became Librarian at Longwood and was an indefatigable copyist of imperial manuscripts.

L / Ali’s English (Catholic) wife, Mary ‘Betsy’ Hall. She was sent out from England by UK relatives of the Countess Bertrand to be governess/nursemaid to the Bertrand children. Married Ali aged 23 in October 1819.

M / Jean Abra(ha)m Noverraz. From the Vaud region in Switzerland. Very tall and imposing figure that Napoleon called his “Helvetic bear”. He was himself ill during Napoleon’s illness.

N / Noverraz’s wife, Joséphine née Brulé. They married in married in July 1819, and she was the Countess Montholon’s lady’s maid. Noverraz and Saint-Denis had a fist fight for the hand of Joséphine.

O / Jean Baptiste Alexandre Pierron. The cook, dessert specialist, long in Napoleon’s service and who had accompanied Napoleon to Elba.

P /Jacques Chandelier. Iincorrectly identified on the picture as Santini who had left the island in 1817. A cook, from the service of Pauline Bonaparte, Napoleon’s sister, who arrived on St Helena with the group from Rome in 1819.

Q /Jacques Coursot. Butler, from the service of Madame Mère, Napoleon’s mother, he arrived on St Helena with the group from Rome in 1819.

R / Doctor Francis Burton. Irish surgeon in the 66th regiment who had arrived on St Helena only on 31st March 1821. He is renowned for having made Napoleon’s death mask (with ensign John Ward and Antommarchi).

S/ Doctor Archibald Arnott. Surgeon in the 20th regiment. Brought in to tend to Napoleon in extremis on 1 April 1821.

T/ Captain William Crokat. A Scot, orderly officer at Longwood for less than a month, having replaced Engelbert Lutyens on 15 April. He received the honour of carrying the news of Napoleon’s death back to London and also the reward, namely, a promotion and £500, privileges of which Lutyens was deliberately deprived by the governor.

#charles de steuben#art#painting#napoleon#bonaparte#st helena#life#death#chateaubriand#french#france#emperor#artist#aesthetics#war#politics#society#culture#arts#personal

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

Day 5-Stilts

Characters: Napoleon, Jean, Isaac, and Yukari (MC)

Pairings : Jean x Napoleon, Isaac x MC

Ao3 Link : Here

All was quiet, save for the soft pitter-patter of rain on the attic window. If it wasn't for his superior hearing, Jean might've missed the heavy sigh that escaped his companion's lips.

Napoleon was leaning on the sill with his cheek propped by the back of his hand. He looked neither sleepy nor deep in thought, gazing absent-mindedly towards the city down below.

They had been sitting this way for half an hour. Jean recalled how the emperor gently took his hand and urged him to come with him after sparring.

"I haven't spent enough time with you," Napoleon spoke sternly. "Can I borrow you for today?"

Jean was correct to let Napoleon lead him up the stairs, thinking that it was loneliness he saw in his eyes. This strange relationship between them, toeing the lines between amour and camaraderie, allowed Jean to see Napoleon's colors which he seldom revealed to anyone.

That 'anyone' apparently included Isaac, the subject of today's woes.

Jean was by no means unobservant. His newfound courage to come downstairs more often in daylight (which Sebastian applauded) meant he could observe the other mansions' residents more closely. Though he still had to dodge the troublemakers Arthur and Dazai whenever possible.

But that also meant he was able to discover new facts about his fellow residents, both directly or from other sources, namely Sebastian. Sometimes, when he entered the kitchen to ask for Rouge (at Napoleon's urging), he'd get roped into the butler's early morning gossip with the mysterious young woman whom he'd learned came from the future through that despicable count's door.

The girl, Yukari, was Isaac's paramour.

Jean supposed her arrival was instrumental in making Napoleon seek his company. What little time Isaac had when not teaching the children, he'd spend more of it with his lover, and less with Napoleon.

It must be boring being a reincarnated emperor, seeing as Napoleon latched onto Jean and his weapons shop. He even made Jean a new tutor in his makeshift school where he, Isaac, and Yukari, taught.

(Jean himself thought it was sweet seeing Napoleon interact with children).

Recently, he'd been sensing something amiss between the two original teachers. Isaac was more awkward with him than usual (and that was saying something), while Yukari's expression changed to a troubled one at any mention of Napoleon. But the woman always skilfully dodged Jean's questions when he asked if his partner had done something towards her.

( Not a very good liar, Jean concluded.)

Everything fell in place when one of the younger children casually asked if "Napoleone" was fighting with Isaac since they were now rarely seen together. " I don't know about that" was his answer, the same one he used when Sebastian suddenly spilled all his speculations on the physicist and former emperor's state of affairs and egged Jean for details.

"They're almost brothers, the two of them." Sebastian sighed. "To think they'd drift apart like this was unthinkable."

It's because of the girl Jean was tempted to say. But he decided to keep his peace instead. Napoleon would come to him in due time. That led Jean to where he was now, spending the gloomy rainy afternoon with a similarly gloomy man.

The taciturn soldier came to attention when the man before him sucked in a deep breath.

"Relax, Jean. I wasn't going to whip you." Napoleon snickered. It sounded hollow.

"Forgive me," Jean apologized for nothing in particular. Time seemed to halt at that very moment, emerald eyes locking with his.

"Isaac is afraid of getting hurt," Napoleon began. "So much so that Yukari even refrains from being frank with him, even when she needs to be. When they need to be with one another."

The eyepatched soldier gazed at him intently, waiting for him to finish.

"Handling people like Isaac, well, it requires you to be cautious both ways," He combed his bangs back with his hand. "If he wants to be comfortable with you, you will have to assure him that you don't feel burdened with his presence, that having him come to you is gratifying enough."

Napoleon paused, seemingly in conflict over what he was about to deliver next.

"In hindsight, maybe this was an error on my part." he sighed, for what was the umpteenth time this afternoon. "I told him, once..."

Jean closed his eye and nodded.

"'At this point, there is nothing that you can say or do to hurt me'" Napoleon repeated his promise he gave Isaac long ago." And trust me that no circumstance will ever cause us to part."

Jean's eye flew open. Yet he remained silent. His eyed one of Napoleon's hands, clenching and unclenching the fabric of his cape. Then, with the same trembling hand, the emperor reached out to graze his cheek. He leaned into the touch, thinking that it might offer Napoleon some respite.

It was true. The softness of Jean's skin was soothing. Warm despite the frigid air outside.

After some time, Napoleon withdrew and looked at Jean expectantly, allowing him to speak.

"But you hurt him instead," Jean stated, matter-of-factly. "And he is now avoiding you."

"Sure did," Napoleon mumbled, gazing out into the drenched city below. "Too many times over the course of their relationship, of course."

"You're worried."

"Well, why shouldn't I?" he barked. "I can't say this out loud. Won't say this out loud. Not even to my real brothers. I dote on him the same way I did them. I was stern, which I'm not with Isaac. I took responsibility for them as their guardian. Still, I need to respect my distance and believe that they'll make the best decisions for themselves even without my input."

"I've heard of historians and even courtiers of my time accusing me of steering my family to further my goals. Well," Napoleon paused to catch his breath. "They can say whatever they wish to say, but bold of them to assume that I waste my nights thinking about what my brothers do or don't do to keep their marriage afloat."

Jean took Napoleon's tirade in a sedated manner, mollifying the emperor's burst of anger to some extent.

Shame soon took over Napoleon's conscience as the lone dark eye regarded him calmly.

"In the end, I have to admit," Napoleon exhaled. "I do care too much about him. And Yukari too."

"I noticed little things that didn't sit well with me about their relationship. In good faith, I tried relaying my thoughts to Isaac, but he didn't take it well." He admitted. "I was a fool. It was a matter of Isaac's pride as a man. Who wouldn't feel wounded if an outsider came up to him and pointed out the faults in his intimate relationship with a woman?"

"I failed to think of him as a man," his lament continued. "I saw him as a brother and failed to acknowledge his worth as his own, mature man with responsibilities." Napoleon finished, burying his face into the crook of his arm.

Outside, the rain was ceasing. Jean could discern the arc of a rainbow in the far-off distance.

Gingerly, he covered Napoleon's hand with his own. He has long removed his gloves, eliminating the barrier between flesh.

"That wasn't a brother you were describing," Jean whispered. "You spoke of him as a son."

Once, they too had walked on eggshells with this particular subject.

Sebastian spoke to Jean once —in meticulous detail —about the King of Rome and Napoleon's distraught at being torn apart from his son. Jean pretended not to know about it afterward, only for Napoleon to bring up the topic himself one day when they were out in the fields letting their horses graze.

He allowed —nay, invited Jean to indulge in his nostalgia of lost family and friends, even his previous loves.

(Jean felt a tinge of irritation whenever Napoleon mentioned Josephine, though he supposed there was no point envying a woman long dead and buried.)

Jean understood Isaac by a fraction. The man saw relationships as walking on stilts, carefully balancing yourself lest you tip and crash.

And bring the other person down with you.

Jean had numerous other parables to illustrate his connections, but he'd rather not dwell upon them now. Not when the man who helped complicated them were here to seek comfort

(In him).

Napoleon's snicker brought Jean out of his reverie.

"I suppose I do play the role sometimes," he contemplated Jean bemusedly. "That would make you his mother, then."

"But I'm not —" Jean flushed upon realizing what he meant. " Napoleon Bonaparte. " He mock-threatened.

Napoleon laughed, a sound Jean had been yearning to hear.

"But I do like to picture us with children," Napoleon leaned back. "I bet they'd be just as beautiful as you."

Jean's blush grew redder at the moment, provoking the other man to tease him further.

"Knowing you, I hope you don't scare them too much," Napoleon cooed. "You frown too much. It breaks my heart to see that delicate face contort into a scowl."

"Stop it already," Jean was burning scarlet right up to his ears. "You're embarrassing me."

"But I know you'd spoil those tykes to no end," the Nightmare of Europe continued. "I wonder what they'd grow up to be, under our nurture."

Jean furiously wiped his face. "That's impossible. You know that."

"True," Napoleon smiled wistfully. "But what an entertaining thought."

The exquisite soldier peeked warily at Napoleon behind his sleeve.

"What?" the smirking man chuckled. "Was that a bit too sappy?"

Jean pouted at him impishly. "For an allegedly terrifying conqueror such as you? Definitely."

"But now that I've known you, nothing about you is ever surprising anymore, Napoleon." Jean lied. He knew there were still many layers of Napoleon that he had yet to uncover.

In that familiar attic, the two men beamed at each other in comfortable stillness, the problem of Isaac and Yukari temporarily forgotten.

They could hear Jupiter's cry in the open, a sure sign that the rain had ended.

Made for @kissmetwicekissmedeadly‘s Napoleon Birthday Prompt 2020. The prompt was “was that too sappy for you?”.

@kisara-16, @thedollarstoresatan @delicateikemenmemes, @ikesensrandomninjagirl, @ashavazesa, @hokkaido-fox, @nuclearwinterexe, @lulu-the-hedgehog, @longingkisses, @weird-profiterole, @napoleonstan, @scummy-writes, @an-otome-cally-correct, @nafeary, @orangenji

#ikemen vampire#ikevam napoleon bonaparte#ikevam jeanne d'arc#ikevam fic#jeanpoleon#riri tries ikevam

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Expression of Culture and Identity Through Art

Introduction

Culture is what unites groups of people. Think back to high school, where students were separated by grade, academic level, and social status. Niche upon niche spread among an entire student body, where everyone had their place. Although some could argue that the clique-like nature of high school is a toxic social construct; I argue that those spaces that I found myself categorized into, made my high school experience feel safe.

The customs and interests I fostered among those social circles gave me room to develop a sense of identity. A sense of control. That for angsty high school me, was everything.

That is why for my final project I want to highlight the idea of cultural identity and how my chosen artists have expressed this concept through their artwork. The subject matter ahead will deal with themes such as race, sexuality, and geographical customs.

The Procuress, Dirck van Baburen, 1622, Oil on Canvas

Sex work is an undeniable staple of Amsterdam. Tourists come from around the world to explore Amsterdam’s red-light district in all it’s glory. It is a location that although salacious to some, holds significant history for the people of Netherlands.

This history dates back as far as 17th century Holland which is the time and location in which our first work, The Procuress by Dirck van Baburen was created. The Procuress is a piece that highlights this cultural aspect of Dutch history by illustrating a prostitution exchange. In the painting we see the procuress, who oversees the prostitutes, soliciting her services to the male client. The male client is showing signs of interest; wrapping his arm around the prostitute, and waving his payment owed towards the procuress. An intriguing detail about the painting is the fact that Baburen displays the prostitute playing a lute identifying, the message he is intending to send regarding the subject matter of the painting. Another notable feature I noticed about the painting is the difference in appearance of the Procuress in comparison to the prostitute. The prostitute’s looks are exaggerated to create a more “desirable” female. Her chest is exposed, and she is young, while in comparison the procuress is conservative and old, almost concealing any signs of femininity.

The era in which this painting was made was known as the Dutch Golden Age, which was filled with genre paintings of brothels. In 17th century Holland there was loose laws pertaining to prostitution that did not protect sex workers, but also did not outlaw their profession. Overall, the public view of prostitution was negative; prostitutes were seen as indecent and conniving. Though, that did not stop many Dutch men from frolicking in the pleasure of sexual promiscuity. Overtime, the tides have shifted for and against sex workers in the Netherlands and it was not until 2000, that prostitution was officially legalized, hundreds of years after this painting was created. Although the tides have been inconsistent, there is no denying the impact this class of people had on developing Dutch culture.

The Emperor Napoleon in His Study at the Tuileries, Jacques-Louis David, 1812, Oil on Canvas

Napoleon Bonaparte, chances are that name ignites some kind of reaction in you, it sure did for those living in 19th century Europe. Napoleon Bonaparte was a French military leader who played an instrumental role in the republicans winning the French Revolution. He rose to power after the coup of 1799, where he was titled as First Consul, which established him as the new leader of France. His ruling style has been studied for years, making some view him as a dictator and some view him as a hero. He was a brilliant military leader, so once he began ruling France he started aggressively expanding into neighboring European countries. He had a “ends justify the means” approach, whether that was a good thing or not depended on if you were on Bonaparte’s good side or not. Someone who was unquestionably on Bonaparte’s good side? Jacques-Louis David.

Napoleon Bonaparte fell in love with Jacques-Louis David’s work after viewing his piece The Intervention of the Sabine Women. He wanted his grandeur to be admired on a large-scale, so he began commissioning portraits from Louis-David, one of those portraits being The Emperor Napoleon in His Study at the Tuileries by Jacques Louis-David. This piece perfectly captures the neoclassical style Jacques Louis-David was famous for. The painting emits a sophisticated level of grandeur, a grandeur that I believe is reminiscent of the French monarchy. Napoleon is posed standing among his successes. Jacques Louis-David composed the painting to allude to the idea of Napoleon staying up late in his study to finish the Napoleonic Code, which is why there is scattered pieces of paper on his desk. Near the desk, you can also see a sword hinting at Napoleon’s success as a military general. Napoleon can also be seen posing with one hand in his vest, an iconic pose commonly associated with the emperor, which stands for nobility.

The idea of the republican regime and the French Revolution was to extinguish the French monarchy, but it seems as though Bonaparte as a leader revels in it’s values. Culturally, France was supposed to move away from nobility and tighten the gap between rich and poor, but that is contrary to what we see in this painting. Napoleon relishes his riches and power and uses Jacques Louis-David’s talent to amplify that message across Europe. Although Napoleon was never crowned as a king, he breathes life into what would turn back into the monarchy later in French history.

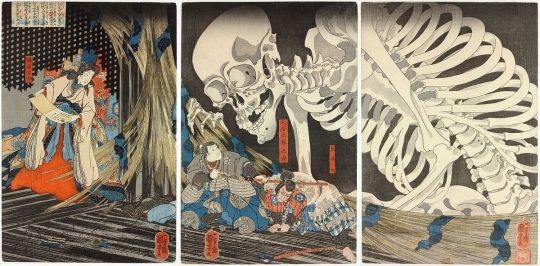

Takiyasha the Witch and the Skeleton Specter, Utagawa Kuniyoshi, 1843 to 1847, Woodblock Print

As the Greeks are famously known for their mythological gods, the Japanese have a set of their own mythological creatures and tales. One novel that makes these themes evident is from the novel Story of Utö Yasutaka written by Santö Kyöden. It is 939CE, and a Samurai by the name of Taira no Masakado is marching to Kyoto with an army to revolt against Japan’s central government. Once at Kyoto, Taira no Masakado’s army holds off against central forces for fifty-nine days before Taira no Masakado’s cousin leads an enemy battalion that demolishes his forces. Seeking revenge Masakado’s daughter, Princess Takiyasha, studies dark magic and summons a Gashadokuro, a gigantic skeleton fabricated from the bones of the fallen, to eat her uncle.

This tale is what Utagawa Kuniyoshi illustrates in his piece Takiyasha the Witch and the Skeleton Specter. Kuniyoshi’s artwork is a woodcut triptych that displays Princess Takiyasha summoning her monster by reading a spell from a scroll. Nearby, Ōya Taro Mitsukuni and a Samurai sent by the Japanese central government to arrest the princes are crouching in fear by the great giant. The most substantial accomplishment of this painting is the anatomical accuracy of the skeleton beast. In Edo Japan anatomical studies and research was far and few between in comparison to Europe at time, making this piece a spectacle.

Fables are common tradition among many cultures and have been used not only as a source of entertainment, but as a method of teaching moral lessons. This idea is no different during the time of Edo Japan, same ideas, different stories. In Ancient Greece while they were warning of Narcissus and his cursed reflection, the Edo Japanese were telling tales of Gashadokuro, beasts that bite off people’s heads.

Four-faced Hamat'sa Mask, George Walkus, 1938, wood, paint, cedar bark, and string

The Four-faced Hamat'sa Mask pictured was hand carved by George Walkus. Hamat’sa, refers to a sacred dance performed by the highest-ranking members of the Kwakwaka’wakw tribe, the tribe in which Walkus is from. Ritual dances are a practical form of story telling and culture preserving among indigenous peoples. The Hamat’sa tells the story of how the Kwakwaka’wakw tribe ancestors killing the beaked, cannibal beast. In turn, for defeating the beast the Kwakwaka’wakw were given his dances, songs, masks, and privileges to bestow upon future generations.

These dances primarily take place in the winter during holiday celebrations such as potlatch. Due to the important nature of such spiritual events for the Kwakwaka’wakw peoples, the masks need to be of the utmost quality. Walkus created his mask with dramatics in mind. The bold blocks of red along the beaks and nostrils bring attention to it’s most daunting features. The mask has cedar-bark fringe attached to the bottom of the mask to camouflage the wearer’s body. The beaks are also built within them, a mechanism that opens and closes the mouth making jarring noises throughout the dance. Everything about the mask is created to enhance the experience and storytelling for the viewer.

American People Series #20: Die, Faith Ringgold, 1967, Oil on Canvas

The 1950s through the 1960s marks the civil rights movement in America. The civil rights movement was a social justice movement where black Americans pushed for the same rights their white neighbors had enjoyed for centuries. Although a turning point in American history, the turn did not follow through without it’s fair share of sacrifices. During this period, black Americans faced huge amounts of backlash from white citizens, politicians, police officers, and so many more. This fallout resulted in the deaths of many black Americans who chose to fight and speak out regardless of the consequences. The civil rights movement came to an end officially on April 4, 1968 when Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated. The outcomes of the movement, although a step in the right direction were only the beginning of the U.S accomplishing racial equality. The civil rights movement gave black Americans the right to vote, lifted public segregation, and created The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAAP), among other achievements.

I believe the most powerful thing an artist can do is tell their truth, and this is precisely what Faith Ringgold does in her The American People Series #20: Die. Through the ongoing racial tension in the 1960s Faith Ringgold creates her American People Series which is a collection of 20 paintings that progressively display the relations between black and white Americans becoming more and more strained. The final piece, Die becomes the outcome of this strife. The painting unveils a bloody massacre between black and white Americans, men and women, the young and old, stating that the issues happening during the civil rights violence is not biased to any singular group of people. If we fall, we all fall together, I can imagine Ringgold saying while creating the piece.

Ringgold believed in the importance of documenting such a chaotic period because of the idea of preserving cultural identity, “How could I, as an African American woman artist, document what was happening around me?” Ringgold states about the painting, which to me says it all, as to why I chose this piece.

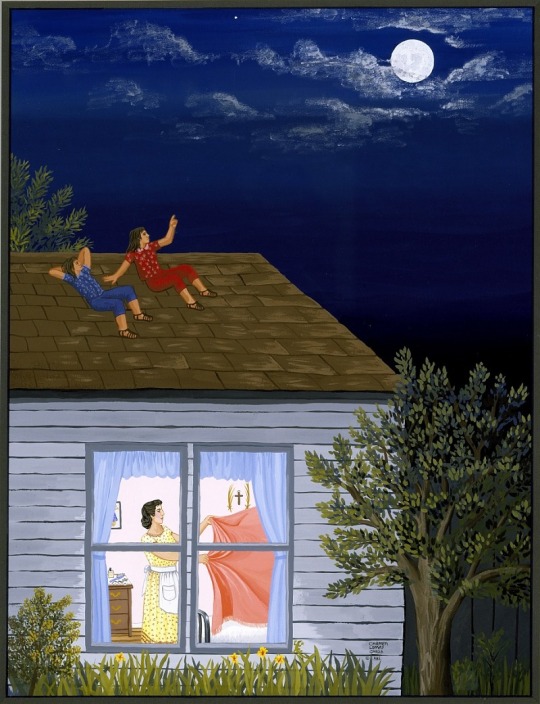

Camas para Sueños, Carmen Lomas Garza, 1985, Gouache on Paper

“Hope” is the first word that comes to mind when I view the piece, Camas para Sueños by Carmen Lomas Garza. The painting brings us into Garza’s childhood growing up as a Mexican female in America. Garza and her sister sit on the rooftop to her childhood home in South Texas, looking at the stars and dreaming of becoming artists. Below the children we see a window to the home, upon closer examination Garza’s mom can be seen tending to the household. What I find interesting about this glimpse into Garza’s childhood home is the symbolism she displays. Her mom seems to be wearing a dress along with an apron while doing chores, reminding me of the classic American housewife. In the house you can also see a cross hanging on the wall, suggesting her home upholds religious values. These two parallels create a tension in the painting, almost like Garza is being pulled into two different directions. Her wonder and exploration outside the household versus her conservative and traditional inside the household. I feel as though this artwork gives me a sense of hope, because of the reminder it gives of the power of children’s dreams, coupled with the fact that Garza’s artwork is being shown in museums today. Meaning, that the child’s dream does end up coming to fruition.

Aside from the painting, Garza credits her drive to create art to the Chicano Movement. The Chicano Movement was an effort led by Mexican Americans between the 1950s to 1970s, to gain equal rights as citizens of America. It was a radicalized movement meant to reclaim and liberate Mexican heritage and identity. It was largely focused on empowering the community, and in the case of Garza I would say it worked.

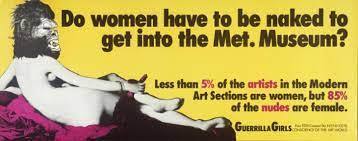

Do Women Have To Be Naked To Get Into the Met. Museum?, Guerilla Girls, 1989, Screenprint on Paper

We had First Wave feminism, where the primary goal on the female agenda was to gain voting rights. In school we learn about activists such as Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and the first women’s rights convention held in Seneca Falls. Next, we had Second Wave feminism, which took place around the 1960s, so I could imagine why it gets overlooked in the curriculum due to the civil rights movement. Second Wave feminism was mainly focused on the wage gap and overall discrimination of females in comparison to males politically. Then we get to Third Wave feminism, which is brushed off in many textbooks, and is generally looked down upon due to it’s radical nature. I would define the Third Wave feminist agenda as honing in on the social constructs of being a women, completely burning the concept down, and rebuilding it from the ground up. The new identities they were creating for themselves and the means in which they were creating them, put many off at the time.

This is the ideology that gave space for artists such as the Guerrilla Girls to voice their discontent with male superiority. In their piece Do Women Have To Be Naked To Get Into the Met. Museum?, they speak out against the Met Museum’s insistence on putting females bodies on display over putting females artist’s artwork on display. They are making a call to action against the male gaze. The poster shows a classic reclining female nude and put a guerrilla mask on her head (alluding to their name), next to a quote in bold letters “Do Women Have To Be Naked To Get Into the Met. Museum?”. Below the bold lettered quote is a caption that articulates the percentage of female nudes in the Met. Versus the percentage of female artists work in the met. The poster is one of 30 apart of a magazine collection titled ‘Guerrilla Girls Talk Back’. The posters are a call to action to females around the U.S to fight the norms of womanhood and stand for equality.

Bar Boy, Salman Toor, 2019, Oil on Wood

Salman Toor is a Pakistani-born, queer artist, who painted the piece Bar Boy. In this painting Toor illustrates a crowded bar scene, with the focal point being a slender male visibly in his own bubble in comparison to the rest of the bar patrons. The male is illuminated by the light of his phone screen, seemingly discontented from those around him. The painting could suggest the discontent the youth feel about dating in the modern era, with online dating, and hookups. Though it seems like the male is unphased by this realization, or maybe he is a part of the problem, taking an interest in his phone rather than in those around him. Maybe, Toor himself is discontent with modern American culture.

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

Re: Louis: Wow, I knew his marriage to Hortense was unhappy and it was mostly his fault, but I didn't know he abused her like that. And now I'm trying to understand why I used to have a soft spot for him, out of all the siblings... I also didn't know about the theory that he was Marbeuf's son! Hard to tell if there's a resemblance given the lack of portraits of Marbeuf, but it's certainly interesting! (ps: thank you so much for taking the time to make such detailed replies, it's really great!)

Louis has always been the least favorite of mine. He’s so gross to me :).

Here is the excerpt from Patrice Gueniffey’s book, Bonaparte, addressing Letizia’s affair with Marbeuf :

(Patrice Gueniffey, Bonaparte, pages 45-47)

“Did the favor the governor showered on the family have other motives? “Through his kindness, he had won the esteem and friendship of the patriots,” Napoleon was to say, “and my father had positioned himself in the first rank of his partisans. It was to this that we owed his protection, and not, as some have falsely said, to his alleged love for my mother.” Although on this point most historians have agreed with Napoleon (who was in his heart of hearts convinced of the contrary), the objections made to the hypothesis of a love affair between Letizia and the governor are not very convincing: adultery, it is said, was impossible in a country where honor, and that of women in particular, was the supreme value, and affronts led to bloodshed. And it was no less impossible, they add, in a country where people lived, so to speak, on their doorsteps, with the result that it was difficult to hide anything. Thus the Buonaparte home is represented as open on all sides, with its gaggle of kids and swarms of aunts, servants, and gossiping women sitting on the sidewalk to enjoy the cool of the evening, watching and commenting on everyone’s acts while they waited for the men to finish talking politics in the cafe, all the rest of their time being taken up by household tasks and childcare: the very image of Mediterranean life in an illustrated magazine. Where would Letizia have found the time to have a lover? How could she have had an affair without bringing ruin on the whole family? To make this image more plausible, Letizia has been presented as “Corsica personified”. The evidence? Several of her ancestors on her mother’s side were from Sartene, the most Corsican part of Corsica. Letizia was a wife, it is said, not a mistress. She is depicted as austere, having experienceced nothing but the yoke, having neither dreams nor feelings, intransigent regarding morals, superstitious and ignorant, obedient to her husband no matter what he said or did, seeking to make up for the latter’s prodigality by an excessive sense of thrift. A Corsican Letizia, but also a Roman Letizia, simultaneously a matron and the “mother of the Gracchi,” refusing to abandon Paoli after he had been betrayed by everyone, and replying to those who begged her not to persist in pursuing a hopeless path: “I won’t go to a country that is the enemy of the fatherland; our general is still alive and all hope is not dead.”

All this is part of the legend. It was in 1770 that Letizia made the acquaintance of the Count of Marbeuf. No historian has denied the governor’s assiduous attentions, the long periods he spent with her, the trips from Bastia to Ajaccio and back that he made more often than necessary for the sole purpose of seeing her. As early as the summer of 1771, they walked the passegiata before the eyes of all Ajaccio. Friendship, one-sided love, or a shared passion? Even the most determined defenders of Letizia’s virtue have been forced to admit that it was neither her wit nor her conversation that attracted the governor and kept him at her side for so many years. Of wit she had none, and still less a gift for conversation. She spoke, Napoleon said, only her “Corsican gibberish”. Marbeuf, for his part, was used to the manner and customs of the court, and anyone who knows the role played in that world by the art of conversation will understand that he could not have been dazzled by anything but the beauty of this woman who was forty years younger than he.

Altough the supervision exercised by the rather difficult Mme de Varese forced him to be relatively discreet, the affair became publicly known around 1775, when Marbeuf broke with his inconvenient mistress. Letizia resided at the governor’s home and rode in his carriage, Charles following with the children in another carriage. Thus toward the end of 1778 a whole cortege, with Marbeuf and Letizia in the lead, accompanied Charles to Bastia, where he was to leave for the continent with Joseph and Napoleon. The latter, despite being only nine, was “extremely struck” by this scene. When the ship had disappeared over the horizon, Letizia did not go back to Ajaccio; she went to Marbeuf’s home in Bastia, and remained there for five months. The Buonapartes spent the end of each year and every summer in Cargese, where Marbeuf owned a property. Everyone in Ajaccio was aware of this, and the memory of it did not fade away: a reference to the love affair between Letizia and the governor appeared in the indictment drawn up by the Paolists in May 29, 1793, in which the Buonapartes were accused of having been “born in the mire of despotism” and of having been “nourished and brought up under the supervision and at the expense of the luxury-loving pasha who was in command on the island.” Was Charles the only one who didn’t know about the affair? That would be surprising. Cuckolds are often the last to discover that they have been deceived, but Charles might have seen some advantage in turning a blind eye to what was going on. Wasn’t Letizia contributing in this way to the family’s advancement? Hadn’t she begun to respond to the governor’s attentions at a time–August 1771–when Charles needed his support to have his nobility recognized? Besides, what would have been scandalous or extraordinary about such an affair, in the eighteenth century and in a city that was Corsican only by its geographical location, and that had passed from a not very prudish Italy to an even less prudish France? The French, while deploring the island’s backwardness, were delighted by the ease with which the women of its cities, and those of Ajaccio in particular, adjusted to the continent’s manners: it was almost enough to make them think that Corsica might not be hopeless. The Buonapartes were people of their time, and the public affair between Letizia and Marbeuf proves only that their assimilation into the society of the end of the Old Regime was rather successful. Finally, we may note that Letizia, who was prompt to reproach her daughters for their prodigality, never reproached them for taking lovers. She cared little for conventions regarding love affairs. Charles seems to have been no less indifferent to these conventions.

Letizia and Marbeuf’s love affair came to an end in the early 1780s. After his wife finally died in 1783, Marbeuf remarried. He was seventy-one years old and his new wife was eighteen; Letizia was twenty-nine and had seven children. The young woman of 1770 had changed, and acquired the severe features we see in depictions of her. The governor founded a family–he had no children, unless he was, as we have suggested, the father of Louis Buonaparte–and he distanced himself from Letizia. He died in 1786. In the Buonaparte home in Malerba Street, the Count of Marbeuf’s portrait long hung in a place of honor, alongside that of Letizia.”

#napoleon#bonaparte#Napoleon Bonaparte#Emperor Napoleon#Emperor Napoleon Ier#Emperor Napoleon I#Patrice Gueniffey#book exerpt#Napoleon books#Napoleon I#Napoleon Ier#Bonaparte Family#Bonaparte Clan#Corsica#Ajaccio#Bastia#Letizia Bonaparte#Letizia Ramolino#Charles Bonaparte#Carlos Bonaparte#Comte de Marbeuf#Letizia affair#love affair#Louis Bonaparte#Napoleon did That tumblr#napoleondidthat#NDT#Napoleon question#question#Napoleon mail

8 notes

·

View notes