#Lundgaard & Tranberg Arkitekter

Photo

Natural History Museum of Denmark, Copenhagen

Lundgaard & Tranberg Arkitekter, Claus Pryds Arkitekter

2022

53 notes

·

View notes

Photo

PIER 47 - LUNDGAARD & TRANBERG ARKITEKTER - COPENHAGEN - DENMARK @lundgaardtranberg #copenhagen #københavn #denmark #architecturephotography #architecturelovers #archdaily #secretkobenhavn #arkitektur #instagood #photooftheday #nikon #architectureporn #architecturehunter #art #city #building #europe #travel #danishdesign #skyscraper #instacity #instaarchitecture #luxury #arquitectura #DJI #mavic #dronephotography #drone #uncity (en Langelinie Allé 21) https://www.instagram.com/p/CQuKxxErd9p/?utm_medium=tumblr

#copenhagen#københavn#denmark#architecturephotography#architecturelovers#archdaily#secretkobenhavn#arkitektur#instagood#photooftheday#nikon#architectureporn#architecturehunter#art#city#building#europe#travel#danishdesign#skyscraper#instacity#instaarchitecture#luxury#arquitectura#dji#mavic#dronephotography#drone#uncity

0 notes

Text

Lynetteholm, New Copenhagen harbour island

Lynetteholm Copenhagen harbour island, Danish Waterfront Buildings Project, Docklands Design News, Images

Lynetteholm, New Island in Copenhagen Harbour

5 May 2021

Lynetteholm København – New Copenhagen harbour island

Design: COWI, Arkitema and TREDJE NATUR

New island in the Copenhagen harbour starts with nature

The new island will be established east of the city and in 2070 have a size of 275 acres.

In Copenhagen, the Danish government and the City of Copenhagen have agreed to establish a new island that will eventually develop into a new, attractive district with room for more than 35.000 inhabitants as well as new infrastructure. Furthermore, Lynetteholm, as it is called, will become a vital part of the climate- and flood protection of Copenhagen, which will be designed as a nature-based climate-proofing solution.

A team of engineers and architects from COWI, Arkitema and THIRD NATURE has been given the task to develop the new 275 acres island. The preliminary work has begun, and the goal is to create an island that will deal with several challenges that the Danish capital is facing. Thus, the island will integrate urban development, urban life, functions, time, economy, and nature in a multi-disciplinary approach.

Lynetteholm is part of the long-standing tradition of urban development and land reclamation that has characterised Copenhagen since it was first founded. Lynetteholm is to come across as a natural expansion and plot a new course for climate-proofing that contributes to the blue and green attractions in the city. Rather than considering the need for climate-proofing and flood protection a stand-alone project, Lynetteholm combines climate-proofing with urban development and presents a unique opportunity to help protect the city against climate change and storm surges by taking a nature-based approach which also adds new urban qualities. In order to realise the above potentials for the island, the UN sustainable development goals (SDGs) are used to identify and specify ambitions and objectives for the new Copenhagen district.

As a consequence the development of the island, will become an example of “Nature first” – meaning the plan is to start out by establishing the island and the 60 acres of coastal landscape created on top of surplus soil from building and infrastructure projects on Copenhagen. The used and unfertile soil will, in the coastal areas be soil improved by adding sand to make the soil less compact and calcium to change the Ph value. The landscape architects see this as an opportunity to create unseen floral landscapes and at the same time make room for new and rare species in the area.

The continuous landscape belt is varying in width which creates a ‘waving’ stretch of the coast containing varying types of nature. This will provide the condition for a biodiverse and species-rich nature area. The area will bring a great nature experience with a specific local character, both above and below water. These features will make Lynetteholm a unique biological setting easily accessible to more than one million people living in greater Copenhagen.

By founding most of the island’s natural habitats before beginning to build infrastructure and buildings, nature will be able to settle and grow up undisturbed along with the establishment of the new Copenhagen city district.

One of the main reasons Lynetteholm is being established is to create a large-scale climate-proofing of the Danish capital. Rising sea levels and increased risk of flooding is becoming an increased threat to Copenhagen and by creating Lynetteholm it will be possible to protect the harbour and city against storm surges from the north. Thus, the island will become a nature-based climate-proofing solution as the coastline is geared to handle both temporary high water levels and permanent rises of the sea levels.

To the north of Lynetteholm ships will have passage to the Copenhagen Harbour. The passage will hold lock gates between Lynetteholm and Nordhavn that will be shut in case of storm floods, which has been seen more and more often in recent years in Danish waters.

The project is developed in close dialogue with the many stakeholders dedicated to urban development in Copenhagen and involves experts in a range of disciplines. The team consisting of COWI, Arkitema and THIRD NATURE, are preparing the overall plans and the layout of Lynetteholm, which will be fully developed in 2070.

Lynetteholm Copenhagen Harbour Island – Building Information

Location: Copenhagen Harbour

Year: 2020 – 2070

Size: 275 ha

Main advisor: COWI

Architecture and landscaping: COWI, Arkitema and THIRD NATURE

Client: By & Havn

Arkitema er grundlagt i Aarhus i 1969 og er i dag en af Skandinaviens største arkitektvirksomheder med over 600 medarbejdere fordelt på kontorer i København, Aarhus, Oslo, Stockholm og Malmø. Arkitema ejes af COWI A/S.

Arkitema

Lynetteholm, New Copenhagen harbour island images / information from Arkitema architects

Location: Copenhagen, Denmark, northern Europe

Copenhagen Harbour Buildings

New Architecture in the Danish Capital’s Harbour – selection below:

Northern Harbour Copenhagen

image : COBE, SLETH MODERNISM, Polyform and Rambøll

Northern Harbour Copenhagen

Nordhavn Islands Copenhagen

Design: C.F. Møller Landscape

image from architect

Nordhavn Islands Project Copenhagen

Steven Holl Copenhagen Harbour Gateway

Copenhagen Harbour Architecture

Copenhagen Harbour Bridge

Inner Harbour Bridge Copenhagen

Harbour Isle Apartments

Copenhagen Architecture

Contemporary Architecture in the Danish Capital – architectural selection below:

Copenhagen Architecture Designs – chronological list

Copenhagen Architecture Tours

Copenhagen Building News – Selection

Copenhagen Architect

AIRE Ancient Baths, Hotel Ottilia, Ny Carlsberg Vej 101

Design: Arkitema

image fro m architecture office

AIRE Ancient Baths

Royal Playhouse : Lundgaard & Tranberg Arkitekter

Tuborg Waves, Denmark : Vilhelm Lauritzen Architects

University Gardens Copenhagen, Ørestad North : Arkitema

Copenhagen Buildings

Comments / photos for the Lynetteholm, New Copenhagen harbour island page welcome

Website: Copenhagen, Denmark

The post Lynetteholm, New Copenhagen harbour island appeared first on e-architect.

0 notes

Photo

Precedent for the culinary function

A perforated metal facade screens a round school in Denmark designed by Lundgaard & Tranberg Arkitekter around a central triple-height gym.

Rings of classrooms sit around the perimeter of Kalvebod Fælled School, which takes its name from the nearby Kalvebod Fælled nature reserve.

Kalvebod Fælled School in Ørestad Syd neighbourhood of Copenhagen is used by children during the day, and doubles as a community in the evening for night-classes, sports and performances.

Lundgaard & Tranberg Arkitekter designed the a series of open and flexible spaces that can facilitate all these uses.

0 notes

Photo

Brick Facade. Axel Towers Designed by Lene Tranberg from the award winning Danish architect firm Lundgaard & Tranberg Arkitekter. : : : #sokarieu #architecturephotography #architecturalphotography #brussels #blackandwhite #fineartphotography #bruse #axeltowers #lenetranberg #archilovers (at Brussels, Belgium) https://www.instagram.com/p/B43PGTJFXVh/?igshid=18ufavk2lgyh8

#sokarieu#architecturephotography#architecturalphotography#brussels#blackandwhite#fineartphotography#bruse#axeltowers#lenetranberg#archilovers

0 notes

Text

A Brief History of Scandinavian Architecture

What makes Scandinavian architecture unique? Scandinavia, using the broader cultural definition to include Finland and Iceland, punches well above its weight architecturally.

This was not always the case. Until the late nineteenth century, Scandinavia was considered an architectural lightweight, as its castles, cathedrals, and other major buildings were usually built in historical styles borrowed from abroad. Most other buildings were vernacular wooden, stone, and brick structures constructed by those without formal architectural training. Although unheralded, they offered practical solutions to problems specific to the far north, including maximizing natural light and heat during the dark, cold winter days.

Scandinavia’s architectural standing began to change in the early twentieth century as architects rejected historicism and instead blended new international styles and technological advances with elements from the vernacular traditions.

This set the stage for what became the defining traits of Scandi buildings: designs that are functional, attractive in a minimalist way, and in balance with nature. At the same time, architects played a role in the emergence of the region’s social welfare model, which required quality housing for all and public buildings for the common good.

Architecture of Sweden

Much of the international acclaim for Scandinavian architecture in the early decades of the twentieth century can be attributed to Swedish Grace, a style mixing Neoclassicism with traditional local elements. Prominent buildings from this period include Stockholm City Hall, Stockholms stadshus, completed in 1923 by Ragnar Östberg, which London’s Observer newspaper praised as “perhaps the finest public building erected in Europe since the eighteenth century,” and the Stockholm Public Library, Stockholms stadsbibliotek, with its circular central reading room, of 1928 by Gunnar Asplund.

Stockholm Public Library, 1928 by Gunnar Asplund

Stockholm City Hall, 1923 by Ragnar Östberg

Asplund pivoted to a new direction at the Stockholm Exhibition in 1930, which he designed in an assertively Functionalist style influenced by the work of the Bauhaus and Le Corbusier. Over the next several decades, Functionalism, or Funkis for short, was Sweden’s dominant style and in the early years it yielded a number of highly regarded works combining a minimalist aesthetic with a humanistic quality often lacking outside Scandinavia. These included the Woodland Cemetery, Skogskyrkogården, of 1940 by Gunnar Asplund and Sigurd Lewerentz and Lewerentz’s St. Mark’s Church, Markuskyrkan, of 1960, both on the outskirts of Stockholm.

Woodland Cemetery, 1940 by Asplund and Sigurd Lewerentz

St. Mark’s Church, 1960 by Sigurd Lewerentz

Over time, design quality often became subordinated to economic and political priorities. “Swedish buildings usually work well, but they are rarely particularly innovative or fun,” architect Per Kraft noted in 2007.

More positively, there have been a number of notable projects of late, including the site-sensitive Artipelag art gallery of 2012 by Nyréns Arkitektkontor and Marge Arkitekter’s Strömkajen Ferry Terminal buildings of 2013; contemporary structures faced with tombac (a copper-zinc -alloy) that fit well with a historic waterfront area.

Artipelag art gallery, 2012 by Nyréns Arkitektkontor

Strömkajen Ferry Terminal, 2013 by Marge Arkitekter. Photo by Johan Fowelin

In northern Sweden, you’ll find one of the more publicly-known modern architectural feats: the Tree Hotel. This multi-structure hotel embedded into the Swedish forest features The Mirrorcube from 2010 by Tham & Videgård and The Cabin from 2010 by Cyrén & Cyrén. Both firms are well-known for their innovative and visually stunning work.

The Mirrorcube, 2010 by Tham & Videgård; The Cabin, 2010 by Cyrén & Cyrén

Architecture of Finland

“Our national identity,” the Finnish government declared in 1998, “has often found its most durable expressions through architecture.” This is attributable in large measure to Eliel Saarinen and Alvar Aalto, innovators who elevated Finnish architecture to elite status.

Blazing a path that many young rising stars of Scandinavian architecture have followed, Saarinen shot to fame by winning a number of architectural competitions while still in his twenties. Initially working with two classmates from school (receiving their first commision before graduating) and later on his own, Saarinen became the leading practitioner of a new national style fusing traditional Finnish building forms with Art Nouveau. This was a cultural triumph with political overtones at a time when Finland was part of the Russian Empire (independence came in 1917) and Swedish was the country’s primary language of government, business, and academics.

Helsinki Central Railway Station, 1919 by Eliel Saarinen

Saarinen’s masterpiece is the Helsinki Central Railway Station, built 1909 to 1919. He moved to the United States in 1923 but his absence was soon filled by Alvar Aalto, who proved to be an even bigger national hero. Aalto, influenced by Gunnar Asplund, softened the hard edges of Functionalism with organic and humanistic touches.

His pioneering works included the Paimio Sanatorium of 1933, celebrated for both maximizing light and air for tuberculosis patients and for his bentwood Paimio chair, exemplifying the connection between Scandinavian architecture and design. Much later, after designing hundreds of buildings in Finland and abroad, the capstone to his career was Finlandia Hall, a concert and conference venue in Helsinki completed in 1975.

Paimio Sanatorium, 1933 by Alvar Aalto

Finlandia Hall, 1975 by Alvar Aalto

Other notable Finnish buildings include the Temppeliaukio Rock Church of 1969 in Helsinki by brothers Timo and Tuomo Suomalainen, which placed most of the structure underground to preserve a popular hilltop park.

Temppeliaukio Rock Church, 1969 by Timo and Tuomo Suomalainen

Since then, significant projects have included the Tampere Main Library of 1986 by Reima and Raili Pietilä, with its sculptural form, and the Helsinki Central Library Oodi of 2018 by ALA Architects that uses glass and wood to create a permeable transition between its interior spaces and an adjoining public square. The Kamppi Chapel or Kampin Kappeli from 2012 designed by K2S Architects, stands as a refuge of calm and quiet within the bustling city of Helsinki.

Tampere Main Library, 1986 by Reima and Raili Pietilä

Kamppi Chapel, 1912 by K2S Architects

Architecture of Denmark

Danish architecture made a big impression locally and across Europe with the Copenhagen City Hall, Københavns Rådhus, of 1905 by Martin Nyrup, which synthesized various influences to forge a striking landmark, but it was not until 1930s that Denmark could be considered the equal of Finland and Sweden on the international scene.

Copenhagen City Hall, 1905 by Martin Nyrup

Several Danes embraced Functionalism and one in particular, Arne Jacobsen, emerged as an architect of the caliber of Aalto and Asplund. Jacobsen’s notable projects included an elegantly designed Functionalist beachfront community in the 1930s comprised of Bellavista Apartments, Bellevue Theater, and beach structures, including sleek lifeguard stands, on the outskirts of Copenhagen and his SAS House of 1960, his most accomplished gesamtkunstwerk (total work of art) which spawned the best-selling Egg and Swan chairs.

SAS House, 1960 by Arne Jacobsen

Another important twentieth century Danish architect was Jørn Utzon, whose most famous work is the iconic Sydney Opera House of 1973, one of many beloved Scandinavian architectural exports.

Sydney Opera House, 1973 by Jørn Utzon

Currently, Danish architecture is enjoying a new golden era. At the forefront and arguably the hottest firm on the planet at the moment is Bjarke Ingels Group. Its buildings in Denmark, such as Instagram-favorite 8 House, 8-Tallet, of 2010 in Copenhagen (in the header image) and the National Maritime Museum of 2013 in Elsinore, are known for unconventional design solutions that maximize light and air and public space.

National Maritime Museum, 2013 by Bjarke Ingels Group

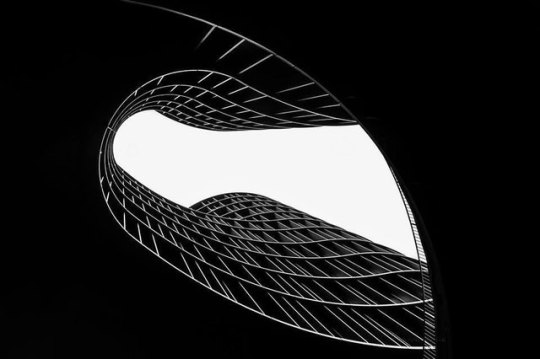

Another popular recent building is Axel Towers, completed in 2017, a commercial complex of five rounded sections of varying heights with a tombac and glass facades, by Lundgaard & Tranberg Arkitekter.

Axel Towers, 2017 by Lundgaard & Tranberg Arkitekter

Architecture of Norway

Norway has followed the same architectural trajectory as her Nordic neighbors, but with certain distinguishing characteristics. First, Norwegian wood (the Beatles were on to something) plays an especially defining role in the nation’s architecture.

Similar to Finland, with the country receiving full independence from Sweden only in 1905, there was a patriotic desire to develop a national architectural style but this did not come as readily in Norway as it did for the Finns. No Saarinen or Aalto figure emerged to lead Norwegian architecture onto the world stage.

Oslo City Hall, 1950 by Arnstein Arneberg and Magnus Poulsson

Instead, several architects contributed to the national portfolio. These include Arnstein Arneberg and Magnus Poulsson, most famous for Oslo City Hall (designed early 1930s but not completed until 1950) with its Funkis architecture and Norwegian-themed applied art; Arne Korsmo whose highlights included the glass and concrete Villa Stenersen of 1939, later used as the prime minister’s residence; and Sverre Fehn, winner of the Pritzker Prize in 1997, whose works, such as his Glacier Museum, were noted for balancing contemporary forms with careful consideration of context.

Villa Stenersen, 1939 by Arne Korsmo

Glacier Museum, 1997 by Sverre Fehn

Following in these footsteps, the current generation has raised Norway’s architectural profile even higher, led by the internationally prominent firm Snøhetta, whose most acclaimed domestic project is the Oslo Opera House of 2008. The waterfront building with its sloped pedestrian-accessible roof and public lobby enclosed by glass and wood is credited with invigorating the capital’s cultural and design scenes.

Oslo Opera House, 2008 by Snøhetta

With this and other projects, such as Helen & Hard’s Vennesla Library and Cultural Centre of 2011, with its wood framed main hall, the long quest for a national style celebrated at home and recognized internationally has been realized.

Vennesla Library and Cultural Centre, 2011 by Helen & Hard

Architecture of Iceland

Icelandic architecture draws heavily on the island’s breathtaking natural landscapes. The country, which only became fully independent from Denmark in 1944, did not have its own native-born trained architects until the twentieth century.

The first one of note, who is credited with single-handedly defining a national style, was state architect Guðjón Samúelsson. Both his National Theater, completed 1950 though designed in the 1920s, and Hallgrímskirkja, the country’s largest church constructed in phases from the 1930s through 1980s, were built in concrete but mimic the basalt lava rock cliff columns that are a national treasure.

Modern notable buildings include Reykjavik City Hall (1992) and the Supreme Court (1996), both by married team Margrét Harðardóttir and Steve Christer of Studio Granda, which feature an assortment of facade materials including basalt.

Reykjavik City Hall, 1992 by Studio Granda

Of more recent vintage, the Harpa concert and conference hall of 2011, with its colored glass and metal frame exterior inspired by the crystalline texture of basalt formations, was a collaboration between Henning Larsen Architects of Copenhagen and Danish-Icelandic artist Ólafur Elíasson. Such Scandinavian architectural cross-fertilizations are common, other examples include a pedestrian bridge in Bergen, Norway by Studio Granda and a Norwegian engineering firm that opened last year.

Harpa concert and conference hall, 2011 by Henning Larsen Architects & Ólafur Elíasson

The Future of Scandinavian Architecture

Scandinavian architecture continues to respond to the challenges and opportunities of the day with creativity and innovation. Added to the longstanding priorities of functionality and balance with nature is an increasing urgency for environmental sustainability.

Snøhetta, for example, is engaged with a consortium including Swedish construction firm Skanska to produce buildings generating more energy than they consume, such as the Powerhouse Drøbak Montessori Secondary School completed in 2018 in Norway, which features solar power, geothermal wells, and energy-efficient design.

In Copenhagen, BIG’s Amager Bakke waste-to-energy plant, being completed in 2019, is reducing the city’s carbon emissions and showing that being green can also be fun by providing a rooftop ski slope.

Other problems persist, notably creating quality housing for all in an age where good design is a highly valued commodity. These issues likely will feature in the next chapters in the history of Scandinavian architecture.

A Brief History of Scandinavian Architecture published first on https://medium.com/@OCEANDREAMCHARTERS

0 notes

Photo

Look up! ✈️ Incredible shot by @sebastianbusck Axel Towers Architects: Lundgaard & Tranberg Arkitekter Location: #Copenhagen #Denmark Photographer: @sebastianbusck https://www.instagram.com/p/BpSIE3HBYra/?utm_source=ig_tumblr_share&igshid=1bg3gm1fcscxa

0 notes

Photo

Kannikegarden, Ribe, Denmark - Lundgaard & Tranberg Arkitekter

https://www.ltarkitekter.dk/

#Lundgaard & Tranberg Arkitekter#architecture#building#design#modern architecture#modern#simple#elegant#contemporary architecture#minimalist#old and new#historical#renovation#archaeology#ruins#burial#culture#cultural space#museum#museum architecture#masonry#tiles#clay#traditional#church#light and shadow#scandi#scandinaviendesign#denmark#danish design

116 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Natural History Museum of Denmark, Copenhagen

Lundgaard & Tranberg Arkitekter, Claus Pryds Arkitekter

2021

37 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Axel Towers By Lundgaard & Tranberg Arkitekter

Photography Via @sebastianbusck

0 notes

Photo

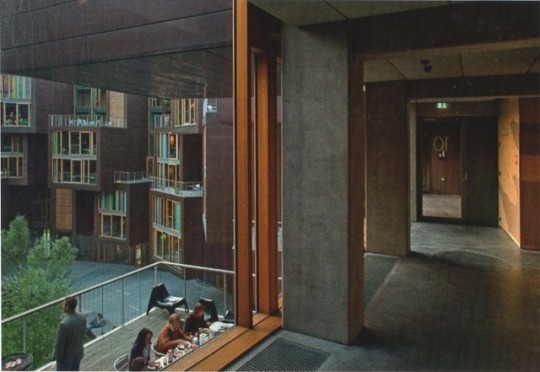

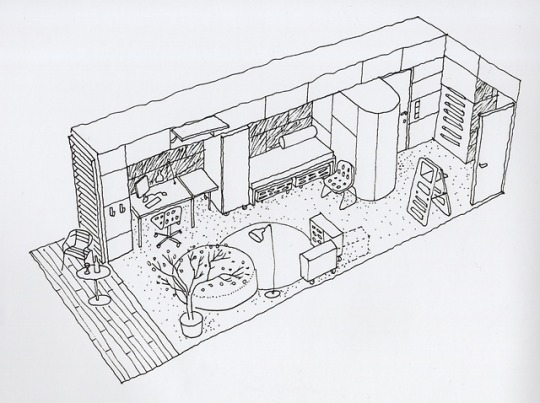

Tietgen Student Hall, Copenhagen. Lundgaard & Tranberg Arkitekter 2002-06

(cluster housing)

Built as a model for the student dormitory of the future. Whole scheme radiates transparency and openness. The core concept is to get people out of their individual rooms and into group activities. Student rooms (1 and 2 person rooms between 12m2 and 27m2) are located above ground floor communal activities (post room, event space, meeting and study rooms, assembly hall, bike storage, laundry) and connected to a central public space. Groups of 12 rooms are accessed from a staircase and share one generously sized kitchen and a balcony for outdoor eating.

0 notes

Text

RIBA reveals 62 projects vying to be named world's best new building

A forest chapel in Japan, an oyster-shell-inspired ferry terminal in Italy and a grain silo converted into an art museum in South Africa are among the projects shortlisted for the second edition of the RIBA International Prize.

The Royal Institute of British Architects has released a longlist of 62 projects vying for the RIBA International Prize 2018, a biennial architecture award that aims to set a global standard for architecture.

Covering everything from small housing projects, to major new museums and office buildings, the list includes projects from 28 countries, by firms including BIG, Zaha Hadid Architects, Foster + Partners and Heatherwick Studio.

Zeitz MOCAA, Cape Town, South Africa, by Heatherwick Studio

Dezeen is media partner for the RIBA International Prize 2018.

Other projects in the running for the award include Dorte Mandrup's sculptural extension to the Wadden Sea visitor centre, along with Ensamble Studio's large-scale contemporary sculptures set in the Montana wilderness.

Also longlisted is a library in Istanbul by Tabanlıoğlu Architects, and a nearby mosque set into terraced steps by Emre Arolat Architects.

Salerno Maritime Terminal, Salerno, Italy, by Zaha Hadid Architects

Rogers Stirck Harbour + Partners has two buildings on the list: a 34-storey office tower in Sydney with criss-crossed red braces, and a 50-storey tower block for a bank headquarters in Mexico City.

Japanese architect Hiroshi Nakamura is behind the forest chapel on the list, while Stefano Boeri is recognised for his tree-covered tower in Milan.

The project that was named World Building of the Year at the World Architecture Festival last month is also among the nominees. The structure, created by a team from the Chinese University of Hong Kong, is a prototype for an affordable, earthquake-proof house built from rammed earth.

BBVA Bancomer Tower, Mexico City, Mexico, by Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners with Legorreta + Legorreta

"The RIBA International List 2018 shines a light on the world's best new buildings and most impressive architectural talent," said RIBA president Ben Derbyshire.

"Most importantly, this significant selection of 62 projects illustrates the meaningful impact and transformative quality that well-designed buildings can have on communities, wherever they are in the world."

Vertical forest, Milan, Italy, by Boeri Studio with Studio Emanuela Borio and Laura Gatti

The RIBA International Prize was open to any registered architect in the world – not just RIBA members. All projects were eligible, regardless of size, type or budget, provided they demonstrated "visionary and innovative thinking".

A jury – including Diller Scofidio + Renfro co-founder Liz Diller and Joshua Bolchover of Rural Urban Framework – will select a shortlist from these 62 projects.

They will then visit each of these projects in person and name four finalists, before an overall winner is announced in November 2018.

Wadden Sea Centre, Ribe, Denmark, by Dorte Mandrup

The first edition of the prize was won by Grafton Architects, with their vertical campus for a Peruvian University.

Described by judges as a "modern-day Machu Picchu", the Universidad de Ingeniería y Tecnología (UTEC) was praised as an exceptional example of civil architecture.

Explore the entire longlist here:

› 8 Chifley Square, Sydney, Australia, by Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners with Lippmann Partnership

› AP House Urbino, Pieve di Cagna, Italy, by Gardini Gibertini Architects

› Audain Art Museum, Whistler, British Columbia, Canada, by Patkau Architects

› Baan Huay Sarn Yaw - Post Disaster School, Chiang Rai, Thailand, by Vin Varavarn Architects

› Baitasi House of the Future, Beijing, China, by Dot Architects

› BBVA Bancomer Tower, Mexico City, Mexico, by Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners with Legorreta + Legorreta

› Beyazıt State Library, Istanbul, Turkey, by Tabanlıoğlu Architects

› Bremer Landesbank Headquarters, Bremen, Germany, by Caruso St John Architects

› Bundner Kunstmuseum Chur, Chur, Switzerland, by Barozzi Veiga

› Cabbage Tree House, Bayview, Australia, by Peter Stutchbury Architecture

Beyazıt State Library, Istanbul, Turkey, by Tabanlıoğlu Architects

› Captain Kelly's Cottage, Tasmania, Australia, by John Wardle Architects

› Central European University - Phase 1, Budapest, Hungary, by O'Donnell + Tuomey with M-Teampannon Kft

› Children Village, Formoso do Araguaia, Brazil, Alephzero with Rosenbaum

› City Hall Deventer, Deventer, Netherlands, by Neutelings Riedijk Architecten

› Cluny Park Residences, Singapore, by SCDA

› Cuernavaca House, Mexico City, Mexico, by Tapia McMahon

› Empower, Khayelitsha, South Africa, by Urban-Think Tank, ETHZ

› EY Centre, Sydney, Australia, by Francis-Jones Morehen Thorp

› Factory In The Forest, Penang, Malaysia, by Design Unit Sdn Bhd with Chin Kuen Cheng Architect

› Garden Tower, Wabern, Switzerland, by Buchner Bründler Architekten

Structures of Landscape, Fishtail, Montana, United States of America, by Ensamble Studio

› GS1 Portugal, Lisbon, Portugal, by PROMONTORIO

› Joolz, Amsterdam, Netherlands, by Space Encounters Office for Architecture

› Kannikegaarden, Ribe, Denmark, by Lundgaard & Tranberg Arkitekter

› Kericho Cathedral, Kericho, Kenya, by John McAslan + Partners with Triad Architects

› King Fahad National Library, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, by Gerber Architekten

› Kunstmuseum Basel, Basel, Switzerland, by Christ & Gantenbein

› Lanka Learning Center, Eastern Province, Sri Lanka, by Feat Collective

› M4 Metro Line Budapest, Budapest, Hungary, by Palatium Studio, with Budapesti Építőművészeti Műhely, Gelesz és Lenzsér Építészeti, Puhl és Dajka Építész Iroda, sporaarchitects, VPI Építész Studio and Palatium M4 Projekt

› MAAT, Lisbon, Portugal, by AL_A

› Maersk Tower, extension of the Panum complex at the University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Denmark, by CF Møller Architects

› Mount Herzl Memorial Hall, Jerusalem, Israel, by Kimmel Eshkolot Architects in collaboration with Kalush Chechick Architects

Sayama Forest Chapel, Tokorozawa, Saitama, Japan, by Hiroshi Nakamura & NAP

› Msheireb Museums, Doha, Qatar, by John McAslan + Partners

› Mulan Weichang Visitor Centre, Weichang, China, by HDD

› Musee d'arts de Nantes, Nantes, France, by Stanton Williams

› Museum Voorlinden, Wassenaar, The Netherlands, by Kraaijvanger Architects

› National Design Centre, Singapore, by SCDA

› Oasia Hotel Downtown, Singapore, by WOHA Architects

› Post-earthquake reconstruction demonstration project of Guangming Village, Zhaotong City, China, by One University One Village Programme, The Chinese University of Hong Kong

› Queen Elisabeth Hall, Antwerp, Belgium, by SimpsonHaugh, with Bureau Bouwtechniek

› ROGIC ROKI Global Innovation Centre, Hamamatsu, Shizuoka, Japan, by Tetsuo Kobori Architects

› Salerno Maritime Terminal, Salerno, Italy, by Zaha Hadid Architects with Interplan Seconda

The Palestinian Museum, Birzeit, Palestine, by Heneghan Peng Architects with Arabtech Jardaneh

› Sancaklar Mosque, Istanbul, Turkey, by EAA-Emre Arolat Architecture

› Sayama Forest Chapel, Tokorozawa, Saitama, Japan, by Hiroshi Nakamura & NAP

› Social Housing in Bairro Padre Cruz, Lisbon, Portugal, by Orange - Arquitectura e Gestão de Projecto with Bruno Silvestre Architecture and D Sul

› Stavros Niarchos Foundation Cultural Center, Athens, Greece, by Renzo Piano Building Worskhop with BETAPLAN

› Structures of Landscape, Fishtail, Montana, United States of America, by Ensamble Studio

› Studio Dwelling at Rajagiriya, Colombo, Sri Lanka, Palinda Kannangara Architects

› Suzhou Chapel, China, by Neri&Hu Design and Research Office

› Tatsumi Apartment House, Tokyo, Japan, Hiroyuki Ito Architects

› The Ancient Church of Vilanova de la Barca, Spain, by AleaOlea architecture&landscape

› The Palestinian Museum, Birzeit, Palestine, by Heneghan Peng Architects with Arabtech Jardaneh

Kericho Cathedral, Kericho, Kenya, by John McAslan + Partners with Triad Architects

› Three Metro Stations L9, Barcelona, Spain, by Garcés-de Seta-Bonet Arquitectes with TEC 4 Ingenieros Consultores

› Tirpitz, Blåvand, Denmark, by BIG

› Toho Gakuen School of Music, Tokyo, Japan, by Nikken Sekkei

› Tolsa 61, Mexico City, Mexico, by MOCAA Arquitectos

› University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, Netherlands, by Allford Hall Monaghan Morris

› Vertical forest, Milan, Italy, by Boeri Studio with Studio Emanuela Borio and Laura Gatti

› Wadden Sea Centre, Ribe, Denmark, by Dorte Mandrup

› Welcome Centre and office building, Shanghai, China, by Sergison Bates Architects

› Xiao Jing Wan University, Shenzhen, China, by Foster + Partners with GDI

› YKK80 Building, Tokyo, Japan, by Nikken Sekkei

› Zeitz MOCAA, Cape Town, South Africa, by Heatherwick Studio with Van Der Merwe Miszewski Architects, Rick Brown Associates and Jacobs Parker

The post RIBA reveals 62 projects vying to be named world's best new building appeared first on Dezeen.

from ifttt-furniture https://www.dezeen.com/2017/12/12/riba-international-prize-2018-longlist-worlds-best-building-hadid-heatherwick-rogers-foster/

0 notes

Photo

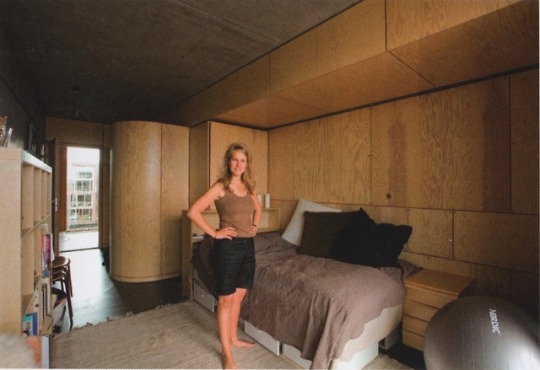

Пример современного общежития из Капенгагена

Университетское общежитие Tietgenkollegiet, спроектированное студией Lundgaard & Tranberg Arkitekter, находится в Эрестаде — самом современном и быстро развивающемся районе Копенгагена, Дания.

0 notes

Photo

Axel Towers Designed by Lene Tranberg from the award winning Danish architect firm Lundgaard & Tranberg Arkitekter. : : : #sokarieu #architecturephotography #architecturalphotography #copenhagen #denmark #blackandwhite #fineartphotography #cityofcopenhagen #axeltowers #lenetranberg #archilovers (at Nyhavn, Copenhagen, Denmark.) https://www.instagram.com/p/BysCcKhF5c5/?igshid=10em4syh086k5

#sokarieu#architecturephotography#architecturalphotography#copenhagen#denmark#blackandwhite#fineartphotography#cityofcopenhagen#axeltowers#lenetranberg#archilovers

0 notes

Text

Пример современного общежития из Капенгагена

Пример современного общежития из Капенгагена

Университетское общежитие Tietgenkollegiet, спроектированное студией Lundgaard & Tranberg Arkitekter, находится в Эрестаде — самом современном и быстро развивающемся районе Копенгагена, Дания.

Рассчитанное приблизительно на 400 студентов, здание претендует на то, чтобы быть знаковым проектом международного формата, реализуя идею «общежития будущего».

Круглое в плане сооружение составлено из…

View On WordPress

0 notes