#Marginocephalia Ceratopsian

Photo

In the late 1990s a partial skeleton of a ceratopsian was discovered in New Mexico, USA. These remains were initially thought to belong to Torosaurus, but after more of the specimen was recovered in the mid-2010s it became clear the bones actually represented an entirely new species of horned dinosaur – officially named in 2022 as Sierraceratops turneri.

Sierraceratops lived during the Late Cretaceous, around 72 million years ago, in what at the time was the southern region of the island continent of Laramidia. About 4.6m long (~15'), it had fairly short chunky brow horns, long pointed cheek horns, and a relatively large frill.

It was part of a unique lineage of ceratopsians that were endemic to southern Laramidia, with its closest known relatives being Bravoceratops from western Texas and Coahuilaceratops from northern Mexico.

———

Nix Illustration | Tumblr | Twitter | Patreon

#science illustration#paleontology#paleoart#palaeoblr#sierraceratops#chasmosaur#ceratopsid#ceratopsian#marginocephalia#ornithischia#dinosaur#art

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Day 7 of the week 2: A modern dinosaur (bird/birb)

A psittacosaurus and a blue macaw.

#my art#dinosaur#dinosaurs#paleoart#dinosauria#myart#psittacosaurus#ceratopsian#cerapoda#marginocephalia#ceratopsia#parrots#birds#blue macaw#macaw#dinocember2021#dinocember#artists on tumblr#sketchbookapp

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Triopticus primus

By Tyler Young/ @cry-olophosaurus

Etymology: Three eyes

First Described By: Stocker et al. 2016

Classification: Biota, Archaea, Proteoarchaeota, Asgardarchaeota, Eukaryota, Neokaryota, Scotokaryota Opimoda, Podiata, Amorphea, Obazoa, Opisthokonta, Holozoa, Filozoa, Choanozoa, Animalia, Eumetazoa, Parahoxozoa, Bilateria, Nephrozoa, Deuterostomia, Chordata, Olfactores, Vertebrata, Craniata, Gnathostomata, Eugnathostomata, Osteichthyes, Sarcopterygii, Rhipidistia, Tetrapodomorpha, Eotetrapodiformes, Elpistostegalia, Stegocephalia, Tetrapoda, Reptiliomorpha, Amniota, Sauropsida, Eureptilia, Romeriida, Diapsida, Neodiapsida, Sauria, Archosauromorpha, Crocopoda, Archosauriformes incertae sedis

Referred Species: T. primus

Status: Extinct

Time and Place: 227 to 226 million years ago, in the Norian of the Late Triassic

Triopticus is known only from the Otis Chalk in Texas, the United States

Physical Description: Triopticus is a very puzzling and frustratingly enigmatic reptile, primarily because it is only known from the back portion of its skull and nothing else, leaving the shape of its body and even the size and shape of its snout a complete and utter mystery. We can’t even rely on phylogenetic bracketing to give us a guide of how it may have looked because its relationships cannot be pinned down beyond Archosauriformes. Even its body size is unclear, but it wasn’t a very big animal at least—the back of its skull could fit in the palm of your hand, so maybe around a metre long.

Nonetheless, the piece of skull that is known is very odd indeed. The back of its skull is remarkably similar to those of pachycephalosaurid dinosaurs, in that Triopticus was also a “bone head” with a thick bony “dome” over its head—it even flares out over the back and sides of the head like in pachycephalosaurs. Unlike pachycephalosaurs, however, the “dome” of Triopticus was not a single smooth structure, but was actually made up of five fused bosses on the bones of the skull that have clumped together to form a single bony dome-like structure. But, of course, the dome of Triopticus is even stranger than that of the pachycephalosaurs’. Right in the centre of the dome, between the bosses, there is a hole that drops right down to the roof of the skull. Like a doughnut. Why? No one knows. The hole happens to sit over right where the pineal gland could have been, and so the hole may have opened for a “third eye” on the top of its head, like many modern lizards and the tuatara have (this is where it gets its name!). And yet, the opening for the third eye was lost in the ancestor of Archosauriformes, so we shouldn’t expect Triopticus to have one in the first place. For that matter, the texture of the bone inside the hole is exactly the same as it is on the inside, implying it was covered in hard, opaque keratin like the rest of the dome. So Triopticus probably really did just have a hole in its head, you have to wonder how it kept that thing clean, or stop it from collecting rainwater.

As for the rest of the body, as frustratingly unclear as its relationships are, we can at least make an educated guess based on other archosauriforms. It was probably quadrupedal, with not very long sprawled to semi-erect legs, a long tail, and maybe some osteoderms running down its back. Of course, considering how weird just the back of its head is, and how other Triassic Weirdos have surprised us, I wouldn’t be surprised if Triopticus turned out to be weird all over. Maybe it was a biped with tiny forelimbs to really take the mickey out of the pachycephalosaur-convergance, who knows. (As it happens, the shape of its inner ear might suggest it really was bipedal, but the evidence is tenuous.)

Diet: Without any jaws and teeth, the diet of Triopticus is a mystery. All other known non-archosaur archosauriforms were carnivores, so it’s quite possible Triopticus was too. But there’s a first time for everything, and maybe the rest of its skull was just as abberant as its dome.

Behavior: Any and all speculations on the behaviour of Triopticus has to revolve around its dome. Fortunately, domes are interesting structures in animals, so there’s a decent amount to say. The obvious interpretation is that the dome convergently evolved for the same purposes suggested for pachycephalosaurs: head-butting. The utility of pachycephalosaur domes has been hotly debated, and presumably the same arguments apply here. Alternatively, the dome could have been just used for display. Either case implies Triopticus were social animals, either using the dome for visual communication or in confrontations between them. Triopticus had particularly big eyes and optic nerves for an archosauriform, so good vision must have been important for whatever it was doing. As before, any other behaviours are a mystery, although as an archosauriform we can reasonably speculate that it laid eggs and probably cared for its young to an extent.

Ecosystem: In the Otis Chalk, Triopticus co-existed with various other stem-archosaurs, including the herbivorous allokotosaur Trilophosaurus, the heavily armoured and boxy Doswellia, the phytosaurs Parasuchus and Angistorhinus, and three species of aetosaur. It also coexisted with at least four dinosaurmorphs, including the lagerpetid Dromomeron, a silesaurid, and the predatory theropods Chindesaurus and Lepidus. There was also the large predator Poposaurus, and even an ornithomimid-like shuvosaurid here too. This ecosystem in some ways was almost like a premonition of the later Cretaceous ecosystems, with phytosaur-like crocodiles, aetosaur-like ankylosaurs, poposaurid-like theropods, shuvosaurid-like ornithomimids, and even the Triopticus-like pachycephalosaurs. Whether Triopticus filled a similar ecological role to the pachycephalosaurs, and not just visual, is up for debate, and its lifestyle remains unknowable.

Other: The discovery of Triopticus and its uncanny similarity to pachycephalosaurs prompted a statistical analysis comparing the body types of various Triassic archosaurs and stem-archosaurs to those of Cretaceous dinosaurs. What they found was substantial overlap, so the eerie similarity between certain Triassic reptiles and dinosaurs wasn’t just people seeing things. The fact simply seems to be that Triassic stem- and crown-archosaurs had already evolved many of the distinctive body-types first known in—and thought to be characteristic of—dinosaurs. Triopticus now adds pachycephalosaurs into the “Triassic did it” roster, which at the time of discovery left only the giant sauropodomorphs, maniraptorans, and ceratopsians as the only ones not represented in the Triassic. Then Shringasaurus rolled around...

~ By Scott Reid

Sources under the cut

Georgi, J.A., Sipla, J.S., Forster, C.A. (2013). "Turning Semicircular Canal Function on Its Head: Dinosaurs and a Novel Vestibular Analysis". PLoS ONE. 8 (3): e58517.

Goodwin, M.B., Horner, J.R. (2004). "Cranial histology of pachycephalosaurs (Ornithischia: Marginocephalia) reveals transitory structures inconsistent with head-butting behavior". Paleobiology. 30 (2): 253–267.

Hieronymous, T.L., Witmer, L.M., Tanke, D.H., Currie, P.J. (2009). "The Facial Integument of Centrosaurine Ceratopsids: Morphological and Histological Correlates of Novel Skin Structures". Anatomical Record. 292 (9): 1370–1396.

Hullar, T.E. (2006). "Semicircular canal geometry, afferent sensitivity, and animal behavior". The Anatomical Record Part A: Discoveries in Molecular, Cellular, and Evolutionary Biology. 288A (4): 466–472.

Nesbitt, S.J. (2011). "The Early Evolution of Archosaurs: Relationships and the Origin of Major Clades". Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History. 352: 1–292.

Stocker, M.R., Nesbitt, S.J., Criswell, K.E., Parker, W.G., Witmer, L.M., Rowe, T.B., Ridgely, R., Brown, M.A. (2016). "A Dome-Headed Stem Archosaur Exemplifies Convergence among Dinosaurs and Their Distant Relatives". Current Biology. 26 (19): 2674–2680.

Voogd, J., Wylie, D.R.W. (2004). "Functional and anatomical organization of floccular zones: A preserved feature in vertebrates". Journal of Comparative Neurology. 470 (2): 107–112.

#Triopticus#Triopticus primus#archosauriform#diapsid#archosauromorph#palaeoblr#triassic madness#triassic march madness#Triassic#reptile#prehistoric life#prehistory#paleontology

191 notes

·

View notes

Text

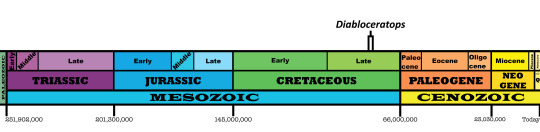

Diabloceratops eatoni

By Jack Wood

Etymology: Devil Horned Face

First Described By: Kirkland et al., 2010

Classification: Dinosauromorpha, Dinosauriformes, Dracohors, Dinosauria, Ornithischia, Genasauria, Neornithischia, Cerapoda, Marginocephalia, Ceratopsia, Neoceratopsia, Coronosauria, Ceratopsoidea, Ceratopsidae, Centrosaurinae?

Status: Extinct

Time and Place: Between 81 and 79 million years ago, in the Campanian of the Late Cretaceous

Diabloceratops is known from the lower and middle members of the Wahweap Formation of Utah

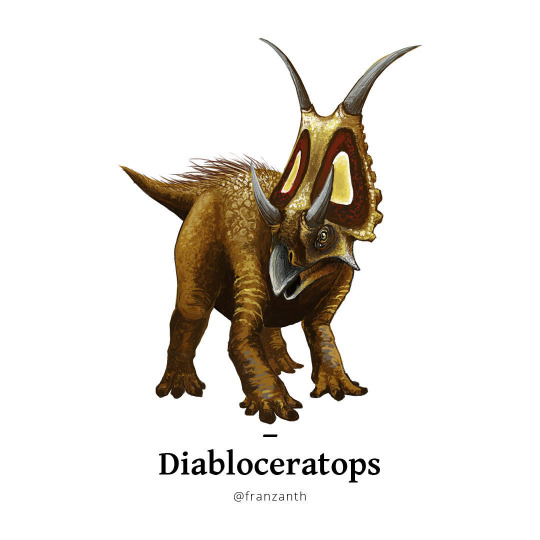

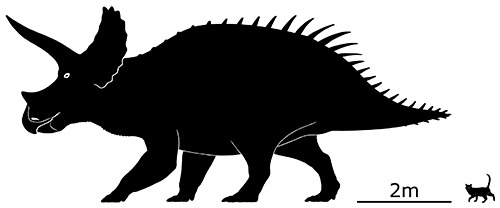

Physical Description: Diabloceratops is one of the most completely visually distinctive Ceratopsids - like all members of this very samey group, its body was the same as the rest of them, but its head was distinctive enough to give it a famous name. Like other Ceratopsids, Diabloceratops had four squat legs, a thick torso, and a short tail. It had a long head, with a large crest and a giant beak in the front of its snout, as well as teeth well built for chewing. The interesting thing about this Ceratopsid is that, while it has small brow horns like most early members of this group, it also had two very noticeable horns coming out of its frills - curving away from each other, the left one curving out to the left and the right one curving out to the right. This gave Diabloceratops the very distinctive look of… well, the Christian depiction of Satan. Hence its name, Devil Horned Face! It had a lightly built skull, with a hole seen in earlier Ceratopsians than the later Ceratopsids, and its head was shorter and deeper than later members. The frill of Diabloceratops was kind of weird too - very tall and narrow, rather than wider as in later Ceratopsians. Diabloceratops was primarily scaly all over, though it is possible (especially given how early derived it was) that it had quills or feathery fluff on its tail like earlier Ceratopsians. It was probably about 5.5 meters long from head to tail.

By Nix, CC BY-NC 4.0

Diet: As a Ceratopsid, Diabloceratops probably fed primarily on plants, though it is possible that it supplemented its diet with meat from time to time for protein. It would focus on low-lying and medium-level plant material, less than a meter in height.

By Franz Anthony

Behavior: The frill and fancy spikes of Diabloceratops would have been primarily used in sexual display and other types of communication between members of the herd, especially since they were rather small all things considered. That being said, other Ceratopsians would use these features for defense, and it is thus likely that Diabloceratops did too, even though they didn’t evolve for such a purpose. Diabloceratops, like other Ceratopsians, would have been a very social animal, spending most of its life in herds with socially complex behavior. These herds would have aided Diabloceratops in defending itself from the local predator Lythronax, and any other predatory animals that may have attempted to attack it. Like other dinosaurs, Diabloceratops probably would have taken care of its young, and the social group would have aided it in doing so. Being a large herbivore with deadly weapons on its face, Diabloceratops would have been a very aggressive animal, not trusting anything that got too close to it or its family. It is possible that Diabloceratops herds also migrated too and from the Western Interior Seaway, based on the seasonal rainfall.

By Sam Stanton

Ecosystem: The Wahweap Formation is one of the earliest environments we know of from the charismatic and iconic Late Cretaceous North American faunas - those ecosystems from the Campanian and Maastrichtian which featured Ceratopsians, Hadrosaurs, and Ankylosaurs a plenty, all being preyed upon by terrifying Tyrannosaurs. Weirdly enough, this unique makeup of these ecosystems is unique to North America - while Hadrosaurs could be found elsewhere somewhat, both Tyrannosaurs and Ceratopsids were very rare elsewhere, Ceratopsids especially so. Instead, the world was frequented with many other kinds of large predatory dinosaurs (especially Abelisaurids), and Titanosaurs were some of the most common large herbivores. But I am getting off track - the Wahweap Formation is one of the earliest of these charismatic locations, and as expected, it has some of the earliest members of these groups to branch off, including Diabloceratops. The Wahweap Formation began as a very dry ecosystem, filled with sand and very brief wet seasons; over time, it became a pond ecosystem and - by the time Diabloceratops disappeared - a very fertile system of rivers running in from the Western Interior Seaway.

By Nathan E. Rogers, used with permission from Studio 252Mya

So, in the time of the earliest part of the formation, Diabloceratops was a living in an extremely seasonally varied environment, as it began to transition to more freshwater being present in later millenia from its earlier dry beginnings. The diversity of the later environments, however, was lacking in the earliest one. Here, Diabloceratops was preyed upon by Lythronax, and while some mammals, turtles, and crocodylomorphs were present, it is entirely possible that the great diversity of mammals and other animals to be found later wasn’t present quite yet. In the middle environment, when the ponds were coming in and things were getting more lush, Lythronax was gone - but now Diabloceratops was accompanied by the Hadrosaur Acristavus, similar to the later Maiasaura. There were many non-dinosaurs too, like turtles, though it is uncertain if the many mammals found in Wahweap are from the middle, lower, or upper parts of this environment.

By Nix, CC BY-NC 4.0

Interestingly enough, one of Diabloceratops’ closest relatives, Machairoceratops, is known from the upper unit of this formation - indicating that it is possible that Diabloceratops evolved into Machairoceratops, and never really disappeared from the environment at all.

By José Carlos Cortés

Other: Diabloceratops is usually found to be a Centrosaurine, the group of Ceratopsids with prominent nose horns and frill ornamentation, and usually little to no brow horns. However, a very recent analysis of Ceratopsian relationships found Diabloceratops to be neither a Centrosaurine nor a Chasmosarine (the other group of Ceratopsians, which includes Triceratops and its closest relatives), but rather outside both. Either way, Diabloceratops was a very early Ceratopsids, showing characteristics that are often found in common between both of the major groups of these dinosaurs - and showing how weird their headgear got even early on in their evolution.

~ By Meig Dickson

Sources Under the Cut

Chiba, K.; Michael J. Ryan; Federico Fanti; Mark A. Loewen; David C. Evans (2018). "New material and systematic re-evaluation of Medusaceratops lokii (Dinosauria, Ceratopsidae) from the Judith River Formation (Campanian, Montana)". Journal of Paleontology. in press (2): 272–288.

Dalman, Sebastian G.; Hodnett, John-Paul M.; Lichtig, Asher J.; Lucas, Spencer G. (2018). "A new ceratopsid dinosaur (Centrosaurinae: Nasutoceratopsini) from the Fort Crittenden Formation, Upper Cretaceous (Campanian) of Arizona". New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin. 79: 141–164.

De Blieux, Donald D. 2007. Analysis of Jim's hadrosaur site; a dinosaur site in the middle Campanian (Cretaceous) Wahweap Formation of Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument (GSENM), southern Utah. Abstracts with Programs – Geological Society of America 39 (5): 6.

Eaton, J. G., R. L. Cifelli. 2005. Review of Cretaceous mammalian paleontology; Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument, Utah. Abstracts with Programs - Geological Society of America 37 (7): 115.

Evans, D. C., and M. J. Ryan. 2015. Cranial anatomy of Wendiceratops pinhornensis gen. et sp. nov., a centrosaurine ceratopsid (Dinosauria: Ornithischia) from the Oldman Formation (Campanian), Alberta, Canada, and the evolution of ceratopsid nasal ornamentation. PLoS ONE 10(7):e0130007

Farke, A. A. 2011. Anatomy and taxonomic status of the chasmosaurine ceratopsid Nedoceratops hatcheri from the Upper Cretaceous Lance Formation of Wyoming, U.S.A. PLoS One 6(1(e16196)):1-9

Farke, A. A., M. J. Ryan, P. M. Barrett, D. H. Tanke, D. R. Braman, M. A. Loewen, and M. R. Graham. 2011. A new centrosaurine from the Late Cretaceous of Alberta, Canada, and the evolution of parietal ornamentation in horned dinosaurs. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 56(4):691-702

Fiorillo, A. R., and R. S. Tykoski. 2012. A new Maastrichtian species of the centrosaurine ceratopsid Pachyrhinosaurus from the North Slope of Alaska. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 57(3):561-573

Fowler, D. W. 2017. Revised geochronology, correlation, and dinosaur stratigraphic ranges of the Santonian-Maastrichtian (Late Cretaceous) formations of the Western Interior of North America. PLoS ONE 12 (11): e0188426.

Gates, T.A.; Horner, J.R.; Hanna, R.R.; Nelson, C.R. (2011). "New unadorned hadrosaurine hadrosaurid (Dinosauria, Ornithopoda) from the Campanian of North America". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 31 (4): 798–811.

Gates, Jinnah, Levitt, and Getty, 2014. New hadrosaurid specimens from the lower-middle Campanian Wahweap Formation of southern Utah. pp. 156–173. In The Hadrosaurs: Proceedings of the International Hadrosaur Symposium (D. A. Eberth and D. C. Evans, eds), Indiana University Press, Bloomington.

Getty, M. A., M. A. Loewen, E. M. Roberts, A. L. Titus, and S. D. Sampson. 2010. Taphonomy of horned dinosaurs (Ornithischia: Ceratopsidae) from the late Campanian Kaiparowits Formation, Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument, Utah. In M. J. Ryan, B. J. Chinnery-Allgeier, D. A. Eberth (eds.), New Perspectives on Horned Dinosaurs: The Royal Tyrrell Museum Ceratopsian Symposium. Indiana University Press, Bloomington 478-494

Hone, D.W.E.; Naish, D.; Cuthill, I.C. (2011). “Does mutual sexual selection explain the evolution of head crests in pterosaurs and dinosaurs?” (PDF). Lethaia. 45 (2): 139–156.

Glut, D. F., 2012, Dinosaurs, the Encyclopedia, Supplement 7: McFarland & Company, Inc, 866pp.

Kentaro Chiba; Michael J. Ryan; Federico Fanti; Mark A. Loewen; David C. Evans (2018). "New material and systematic re-evaluation of Medusaceratops lokii (Dinosauria, Ceratopsidae) from the Judith River Formation (Campanian, Montana)". Journal of Paleontology. in press (2): 272–288.

Kirkland, J. I. 2005. An inventory of paleontological resources in the lower Wahweap Formation (lower Campanian), southern Kaiparowits Plateau, Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument, Utah. Abstracts with Programs - Geological Society of America 37 (7): 114.

Kirkland, J. I., and D. D. DeBlieux. 2007. New horned dinosaurs from the Wahweap Formation, Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument, southern Utah. Utah Geological Survey Notes 39(3):4-5

Kirkland, J. I., and D. D. Deblieux. 2010. New basal centrosaurine ceratopsian skulls from the Wahweap Formation (middle Campanian), Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument, southern Utah. New Perspectives on Horned Dinosaurs: The Royal Tyrrell Museum Ceratopsian Symposium. Indiana University Press, Bloomington 117-140

Loewen, M. A., R. B. Irmis, J. J. W. Sertich, P. J. Currie, and S. D. Sampson. 2013. Tyrant dinosaur evolution tracks the rise and fall of Late Cretaceous oceans. PLoS ONE 8(11):e79420

Lund, E. K., P. M. O'Connor, M. A. Loewen and Z. A. Jinnah. 2016. A new centrosaurine ceratopsid, Machairoceratops cronusi gen et sp. nov., from the Upper Sand Member of the Wahweap Formation (Middle Campanian), southern Utah. PLoS ONE 11(5):e0154403:1-21

Mallon, Jordan C; David C Evans; Michael J Ryan; Jason S Anderson (2013). [tp://link.springer.com/article/10.1186/1472-6785-13-14 “Feeding height stratification among the herbivorous dinosaurs from the Dinosaur Park Formation (upper Campanian) of Alberta, Canada”]. BMC Ecology. 13: 14.

Orsulak, M. 2007. A lungfish burrow in late Cretaceous upper capping sandstone member of the Wahweap Formation Cockscomb area, Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument, Utah. Abstracts with Programs - Geological Society of America 39 (5): 43.

Sampson, S. D., 2001, Speculations on the socioecology of Ceratopsid dinosaurs (Orinthischia: Neoceratopsia): In: Mesozoic Vertebrate Life, edited by Tanke, D. H., and Carpenter, K., Indiana University Press, pp. 263–276.

Simpson, Edward L.; Hilbert-Wolf, Hannah L.; Wizevich, Michael C.; Tindall, Sarah E.; Fasinski, Ben R.; Storm, Lauren P.; Needle, Mattathias D. (2010). "Predatory digging behavior by dinosaurs". Geology. 38 (8): 699–702.

Tester, E. 2007. Isolated vertebrate tracks from the Upper Cretaceous capping sandstone member of the Wahweap Formation; Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument, Utah. Abstracts with Programs - Geological Society of America 39 (5): 42.

Thompson, C. R. 2004. A preliminary report on biostratigraphy of Cretaceous freshwater rays, Wahweap Formation and John Henry Member of the Straight Cliffs Formation, southern Utah. Abstracts with Programs - Geological Society of America 36 (4): 91.

Weishampel, David B; et al. (2004). "Dinosaur distribution (Late Cretaceous, North America)." In: Weishampel, David B.; Dodson, Peter; and Osmólska, Halszka (eds.): The Dinosauria, 2nd, Berkeley: University of California Press. Pp. 574–588.

Williams, J. A. J., C. F. Lohrengel. 2007. Preliminary study of freshwater gastropods in the Wahweap Formation, Bryce Canyon National Park, Utah. Abstracts with Programs - Geological Society of America 39 (5): 43.

Zubair A. Jinnah, #30088 (2009)Sequence Stratigraphic Control from Alluvial Architecture of Upper Cretaceous Fluvial System - Wahweap Formation, Southern Utah, U.S.A. Search and Discovery Article #30088. Posted June 16, 2009.

#Diabloceratops eatoni#Diabloceratops#Dinosaur#Ceratopsian#Palaeoblr#Factfile#Ceratopsid#Mesozoic Monday#Herbivore#Cretaceous#North America#paleontology#prehistory#prehistoric life#dinosaurs#biology#a dinosaur a day#a-dinosaur-a-day#dinosaur of the day#dinosaur-of-the-day#science#nature

412 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hey! LOVE your blog and evolutionary / anatomical musings. What do you think the deal with the brothers 'Blos is (That is to say, Mono and Diablo)? Theropods that have weirdly ceratopsian faces? EXTREMELY derived ceratopsians? Or wyverns with just a strong case of convergent evolution?

Well, thanks to the Hermitaurs, we know that Monoblos and Diablos possess frills of solid bone and forward facing nares that are basically nonexistent, so I’d say that takes them out of the running to be derived ceratopsians. The rest of their skulls lack any and all fenestrae, which means it’s unlikely that they’re theropods.

If they are dinosaurs at all, my guess would be that they are extremely derived Pachycephalosaurids, since they also have very thick, horned skulls that lack fenestrae. Given that pachycephalosaurs and ceratopsians are in the same clade (Marginocephalia), Monoblos and Diablos convergently evolving eerily ceratopsian headwear wouldn’t be too crazy.

24 notes

·

View notes

Photo

A genus of pachycephalosaurid (dome-headed) dinosaur that lived in what is now North America during the Late Cretaceous period, about 77.5 to 74 million years ago (mya). The first specimens from Alberta, Canada, were described in 1902, and the type species Stegoceras validum was based on these remains. The generic name means "horn roof", and the specific name means "strong". Several other species have been placed in the genus over the years, but these have since been moved to other genera or deemed junior synonyms. Currently only S. validum and S. novomexicanum, named in 2011 from fossils found in New Mexico, remain. The validity of the latter species has also been debated. Stegoceras was a small, bipedal dinosaur about 2 to 2.5 metres (6.6 to 8.2 ft) long, and weighed around 10 to 40 kilograms (22 to 88 lb). The skull was roughly triangular with a short snout, and had a thick, broad, and relatively smooth dome on the top. The back of the skull had a thick "shelf" over the occiput, and it had a thick ridge over the eyes. Much of the skull was ornamented by tubercles (or round "outgrowths") and nodes (or "knobs"), many in rows, and the largest formed small horns on the shelf. The teeth were small and serrated. The skull is thought to have been flat in juvenile animals and to have grown into a dome with age. It had a rigid vertebral column, and a stiffened tail. The pelvic region was broad, perhaps due to an extended gut. Originally known only from skull domes, Stegoceras was one of the first known pachycephalosaurs, and the incompleteness of these initial remains led to many theories about the affinities of this group. A complete Stegoceras skull with associated parts of the skeleton was described in 1924, which shed more light on these animals. Pachycephalosaurs are today grouped with the horned ceratopsians in the group Marginocephalia. Stegoceras itself has been considered basal (or "primitive") compared to other pachycephalosaurs. Stegoceras was most likely herbivorous, and it probably had a good sense of smell. The function of the dome has been debated, and competing theories include use in intra-specific combat (head or flank-butting), sexual display, or species recognition. S. validum is known from the Dinosaur Park Formation and the Oldman Formation, whereas S. novomexicanum is from the Fruitland and Kirtland Formation.

Herbivore

Art (c) reneg661

1 note

·

View note

Text

Chapter 9 Homework

1. Pachycephalosaurs and ceratopsians are united in a group called _____.

a. Thyreophora

b. Marginocephalia

c. Ornithopoda

d. Ornithischia

2. Ceratopsians comprise two groups, _____.

a. Psittacosauridae and Neoceratopsia

b. Protoceratopsidae and Ceratopsidae

c. Homalocephalidae and Pachycephalosauridae

d. Neoceratopsia and Pachycephalosauria

3. _____ well represents the…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Photo

Although much less famous than their larger horned and frilled relatives, the leptoceratopsids were a widespread and successful group of ceratopsian dinosaurs during the Late Cretaceous, with fossils known from North America, Asia, and Europe (and, dubiously, Australia).

They were fairly small stocky quadrupedal dinosaurs, sort of pig-like, with short deep jaws and powerful beaks adapted for eating fibrous low-level plants like ferns and cycads — and to process such tough food they even evolved a chewing style similar to mammals like rodents.

Prenoceratops pieganensis here is known from the Two Medicine Formation bone beds in Montana, USA, dating to about 74 million years ago. Around 1.5-2m long (~5'-6'6"), it was very similar to its later relative Leptoceratops, but had a slightly lower, more sloping shape to its skull.

———

Nix Illustration | Tumblr | Pillowfort | Twitter | Patreon

#science illustration#paleontology#paleoart#palaeoblr#prenoceratops#leptoceratopsidae#neoceratopsia#ceratopsian#marginocephalia#neornithischia#ornithischia#dinosaur#art#pigrodent dinos

279 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Weird Heads Month #14: Horns and Frills

We can't go through this month without having an appearance from the most famous group of weird-headed dinosaurs: the ceratopsids!

Their distinctive-looking skulls were highly modified from those of their ancestors, with large bony frills extending from the back of their heads, various elaborate horns and spikes, enormous nasal cavities, large hooked beaks at the front of their snouts, and rows of slicing teeth further back.

And while typically depicted as purely herbivorous, ceratopsids' powerful parrot-like beaks and lack of grinding teeth suggest they may actually have been somewhat more omnivorous – the Cretaceous equivalent of pigs – still feeding mainly on plant matter but also munching on carrion and opportunistically eating smaller animals when they got the chance.

Machairoceratops cronusi here lived during the late Cretaceous of Utah, USA, about 77 million years ago. Only one partial skull has ever been found belonging to an individual about 4.5m long (14'9"), but it wasn't fully grown and so probably reached slightly larger sizes.

It had two long spikes at the top of its frill, similar to its close relative Diabloceratops but curving dramatically forward and downwards above its face. Whether they were purely for display or used in horn-locking shoving matches is unknown, but either way it was a unique arrangement compared to all other known ceratopsids.

———

Nix Illustration | Tumblr | Pillowfort | Twitter | Patreon

#weird heads 2020#science illustration#paleontology#paleoart#palaeoblr#machairoceratops#centrosaurinae#ceratopsidae#neoceratopsia#ceratopsian#marginocephalia#neornithischia#ornithischia#dinosaur#art#flamboyant spiky piglizards

190 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Medusaceratops lokii, a ceratopsid from the Late Cretaceous of Montana, USA (~77.5 mya).

About 6m long (19′8″), it had long brow horns and large curved spikes on its frill -- an arrangement very similar in appearance to the centrosaur Albertaceratops, and initially its fossils were misidentified as belonging to that particular ceratopsid. But in 2010 it was recognized as a different genus, and based on some partial frill remains it was classified as a very early chasmosaur (a different branch of the ceratopsids which includes Triceratops), related to other early forms like Mercuriceratops.

Its genus name was based on the snake-haired Medusa from Greek mythology, while its species name comes from the Norse trickster god Loki -- both in reference to the years of confusion about the identity of Medusaceratops’ fossils, and the distinctive curved horns on the helmet of Marvel’s Loki.

And, true to its name, the confusion wasn’t over yet.

Recently more fossil material and a new study have shown it was still being misclassified. Now it seems like Medusaceratops was actually part of the centrosaur lineage all along, and was indeed a very close relative of Albertaceratops.

It also turns out that what were thought to be numerous Albertaceratops fossils found in the same location were all just even more Medusaceratops. Instead of a mixture of two different ceratopsids there’s a single big bonebed representing some sort of mass-mortality event of only this one animal.

Similar mass bonebeds have been found for other centrosaurs in the same area and around the same age. Perhaps there were frequent flash floods at the time, or they were attempting to migrate across fast-flowing rivers like some modern animals, but we still don’t actually know for certain why they died en masse so frequently.

#science illustration#paleontology#paleoart#palaeoblr#medusaceratops#dinosaur#centrosaurinae#ceratopsidae#neoceratopsia#ceratopsian#marginocephalia#neornithischia#ornithischia#albertaceratops#art

190 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Ceratopsian Month #20 -- Styracosaurus albertensis

The last centrosaur for this month is one of the most distinctive and recognizable of all ceratopsians -- the elaborate Styracosaurus (“spiked lizard”).

Known from Alberta, Canada, about 75 million years ago, it was part of the Centrosaurini branch of the centrosaur evolutionary tree, closely related to both Centrosaurus and Coronosaurus. Many fossils have been found in several different bonebeds, including some nearly complete skeletons with body lengths of around 5.5m (18′).

There was a lot of variation in the frill ornamentaion between different Styracosaurus individuals. They could have either two or three pairs of very long spikes at least 50cm long (19″), along with various smaller hooks, knobs, or tab-shaped projections.

The long nose horn was also very variable between specimens, with some pointing slightly backwards, some being straight, and others pointing forwards. Juveniles are known to have had small pointed brow horns which became even more reduced in adults.

Tomorrow we’re moving on to the chasmosaurs, so here’s the centrosaur evolutionary tree:

#science illustration#paleontology#paleoart#palaeoblr#ceratopsian month 2017#styracosaurus#centrosaurini#centrosaurinae#ceratopsidae#neoceratopsia#ceratopsian#marginocephalia#neornithischia#ornithischia#dinosaur#archosaur#art#speculative fluffiness#feather ALL the dinosaurs#who wanted manes beards and mustaches? because here you go :D#also All The Quills#maximum spikiness

497 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Ceratopsian Month #31 -- Triceratops horridus

Of course we’re ending this month with the most famous of the ceratopsians, the dinosaur superstar Triceratops (“three-horned face”).

Dating to the very end of the Cretaceous, between 68 and 66 million years ago, it was the most common ceratopsid in North America at the time, ranging from Alberta, Canada down to Colorado, USA. Two different species are currently recognized within the genus -- T. horridus in the older part of that time range, and T. prorsus in the younger rock layers.

It was one of the very largest ceratopsians, with the biggest individuals reaching sizes of about 7.9-9m (26’-29’6”). Many fossil remains have been found, representing growth stages from juveniles to adults (with Torosaurus speculated to represent the most fully mature individuals), and a lot of variation in exact horn and frill shape is seen between different skulls. One specimen nicknamed “Yoshi’s trike” had some of the longest brow horns of any ceratopsid, with the bony cores alone measuring 1.15m long (3′9″).

Unusually for a chasmosaur, it had a very short and solid frill with no weight-reducing holes, suggesting the structure served a much more defensive role than in other ceratopsids. Damage to the frill bones in some specimens appears to have been caused by other Triceratops, giving support to the popular depiction of these dinosaurs locking horns in fights.

Tooth-marks from the equally-famous Tyrannosaurus have also been found on Triceratops bones. Not all of these predator-prey encounters were fatal, however, with some specimens showing evidence of healing around the damaged areas.

Fossilized skin impressions show that Triceratops was scaly -- but with scales unlike those of any other known dinosaur, showing large polygonal scales interspersed with even bigger knobbly scales with odd “nipple-shaped” conical projections in their centers. It’s possible that the “nipples” may have supported larger structures (as I’ve illustrated above), but unfortunately no official scientific description of this skin has been published yet and details about it are vague.

And with this final entry, here’s the chasmosaur evolutionary tree:

#science illustration#paleontology#paleoart#palaeoblr#ceratopsian month 2017#triceratops#triceratopsini#chasmosaurinae#ceratopsidae#neoceratopsia#ceratopsian#marginocephalia#neornithischia#ornithischia#dinosaur#archosaur#the 'toromorph' debate#art#have some actually scaly dinosaurs#triceratops' weird nipple-scales#go home evolution you're drunk

226 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Ceratopsian Month #25 -- Pentaceratops sternbergii

Despite its name, Pentaceratops (“five-horned face”) only had three main facial horns just like most other ceratopsids. The extra two “horns” actually refer to the cheek spikes which protruded out sideways from its face -- a feature seen in all ceratopsids to some degree, but especially long and sharply pointed in Pentaceratops.

Living about 76-73 million years ago, its fossils are known from New Mexico and Colorado, USA. A possible second species, P. aquilonius, was discovered much farther north in Alberta, Canada, but this identification is somewhat dubious due to the remains being highly fragmentary.

Multiple specimens have been found, with a full body length of around 5-6m (16’4"-19’8”). One especially large specimen previously identified as Pentaceratops was nearly 7m long (23′), but has since been moved into its own separate genus Titanoceratops.

Pentaceratops’ frill was one of the largest of all known ceratopsids, similar in size and shape to that of its close relative Utahceratops, with a U-shaped top edge and a pair of forward-curving spikes.

#science illustration#paleontology#paleoart#palaeoblr#ceratopsian month 2017#pentaceratops#chasmosaurini#chasmosaurinae#ceratopsidae#neoceratopsia#ceratopsian#marginocephalia#neornithischia#ornithischia#dinosaur#archosaur#art

228 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Ceratopsian Month #14 -- Wendiceratops pinhornensis

Wendiceratops (“Wendy’s horned face”) was one of the older known centrosaurs, living about 79 million years ago in Alberta, Canada -- but it had a slightly higher position in the evolutionary tree than more basal forms like Xenoceratops, indicating just how incredibly quickly the early ceratopsids diversified.

Partial remains of several individuals have been found, representing both adults and juveniles, with an estimated full size of around 6m long (19′8″).

It had forward-curving frill spikes, similar to those of its close relative Sinoceratops, and a large nose horn. The size of its brow horns are unknown, so the ones seen in this reconstruction are based on the fairly well-developed horns of other similarly-aged centrosaurs.

#science illustration#paleontology#paleoart#palaeoblr#ceratopsian month 2017#wendiceratops#centrosaurinae#ceratopsidae#neoceratopsia#ceratopsian#marginocephalia#neornithischia#ornithischia#dinosaur#archosaur#art

259 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Ceratopsian Month #13 -- Sinoceratops zhuchengensis

Sinoceratops (“Chinese horned face”) was the first and only ceratopsid known from China, and possibly also the only one known from the entirety of Asia -- depending on whether Turanoceratops counts as a true ceratopsid or not.

Discovered in the Shandong province, it dates to about 73 million years ago and was one of the larger centrosaurs at an estimated length of at least 6m (19′8″).

It had a well-developed nose horn and highly reduced brow horns, and forward-curving spikes around the edge of its frill that gave it a crown-like appearance. Uniquely for a ceratopsid, it also had some protruding bumps just below the spikes, creating a second row of ornamentation.

The presence of Sinoceratops in China shows that at least one lineage of centrosaurs dispersed across to Asia in the Late Cretaceous, but they seem to have been quite rare animals on that side of Beringia. While other dinosaur groups such as hadrosaurs and tyrannosaurs seemed to do just fine on both continents, something prevented the ceratopsids from being nearly as prolific as their North American relatives.

#science illustration#paleontology#paleoart#palaeoblr#ceratopsian month 2017#sinoceratops#centrosaurinae#ceratopsidae#neoceratopsia#ceratopsian#marginocephalia#neornithischia#ornithischia#dinosaur#archosaur#art

245 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Ceratopsian Month #30 -- Torosaurus latus

Torosaurus (“perforated lizard”) was a particularly widespread member of the Triceratopsini, found across western North America. Fossils are known from Canada all the way down to New Mexico and Texas in the southern regions of the USA, although the southernmost specimens represent a second species within the genus, T. utahensis.

Living about 68-66 million years ago, it was one of the largest ceratopsids, reaching body lengths of around 7.5m (24’7"). The size and shape of its three horns varied between individuals, from short and straight to much longer and curving forwards.

It had one of the longest skulls of any known land animal, with some specimens’ heads measuring at least 2.5m long (8′2″). Around half of that length consisted solely of its frill, the shape of which was also quite variable -- some were very flat while others curved upwards, and the top edge could be either rounded, straight, or have a “heart-shaped” notch.

In 2010 a study was published by John Scannella and Jack Horner, hypothesizing that Torosaurus wasn’t a unique genus and was actually the fully mature form of Triceratops. While poor media reporting briefly sent the internet into a panic about Triceratops “never existing”, further studies by other paleontologists have failed to come up with the same results, and the debate doesn’t seem to have come to any overall consensus yet.

#science illustration#paleontology#paleoart#palaeoblr#ceratopsian month 2017#torosaurus#triceratopsini#chasmosaurinae#ceratopsidae#neoceratopsia#ceratopsian#marginocephalia#neornithischia#ornithischia#dinosaur#archosaur#art#the 'toromorph' debate

143 notes

·

View notes