#Mary of Menteith

Text

On March 26th 1402, heir to the Scottish throne, David Stewart, 1st Duke of Rothesay, died in mysterious circumstances at Falkland Palace.

This event in Scottish history ties in with James I being sent to France and falling into English hands, I covered that part in a post a few days ago.

David Stewart was the oldest son of Robert III of Scotland and Anabella Drummond and was born on 24 October 1378. At the time of his birth, his grandfather, Robert II still occupied the Scottish throne. His father became King of Scotland in November 1384, when his earldom of Carrick passed to David.

In 1398, David was created Duke of Rothesay by his father. In the following year, at the age of 21, due to the infirmity of his father the king, he was appointed “Lieutenant” of Scotland by Parliament, to rule in his father’s place. The arrangement had been urged by his mother, Queen Annabella, to ensure her son succeeded his ailing father. His uncle, Robert Stewart, a ruthless politician with designs on the throne himself, had previously been protector of the kingdom.

In 1395, David married Elizabeth Dunbar, the daughter of George Dunbar, Earl of March, but the Papal dispensation required because they were close relatives was never obtained, and in 1397 the couple separated.

David later married Mary Douglas, daughter of Archibald Douglas, 3rd Earl of Douglas, to form an alliance with the Douglases, which gravely offended George Dunbar. Dunbar accordingly switched his allegiance to Henry IV of England, who then invaded Scotland, briefly capturing Edinburgh before returning to England.

Following the death of his mother in 1401, David failed to consult his council, as he was required to do, before making a series of decisions that were seen to threaten the positions of his nobles, especially his uncle, Robert Stewart, 1st Duke of Albany.

In February 1402, while travelling to St Andrews, David was arrested just outside the city by Sir John Ramornie and Sir William Lindsay of Rossie, agents of his uncle Albany, who at that time was in alliance with Archibald, fourth Earl of Douglas. David’s father-in-law, the third Earl, had died two years previously, in 1400.

He was initially held prisoner in St Andrews Castle, but soon afterwards was taken to Falkland Palace, Albany’s residence in Fife. David spent the journey hooded and mounted backwards on a mule.

David remained a prisoner and shortly after died in the dungeons of Falkland Palace, reputedly of starvation.

A few weeks later, in May 1402, a public enquiry into the circumstances of David’s death, largely controlled by Albany, exonerated him of all blame concluding that David had died “by divine providence and not otherwise” and commanded that no one should ‘murmur against’ Albany and Douglas.

The following is taken from the records of the Scottish Parliament 16 May 1402

Letters: narrating the inquest into the death of David Stewart, duke of Rothesay and the role of Robert Stewart, duke of Albany, and Archibald Douglas, earl of Douglas.

Robert, by the grace of God king of Scots, to all to whose notice the present letters shall come, greeting. Whereas recently, our most beloved Robert [Stewart, 1st] duke of Albany, earl of Fife and Menteith, our brother german, and Archibald [Douglas, 4th] earl of Douglas and lord of Galloway, our son according to law by reason of our daughter who he took as wife, caused our very beloved firstborn son the late David [Stewart, 1st] duke of Rothesay and earl of Fife and Atholl, to be captured and personally arrested, and first to be guarded in St Andrews castle and then to be detained in keeping at Falkland, where, by divine providence and not otherwise, it is discerned that he departed from this life; they, compearing in our presence in our general council begun at Edinburgh on 16 May 1402 and continued for several days, and interrogated or accused upon this by our royal office of the capture, arrest, death as is expressed above etc., in this manner, confessing everything that followed thereafter, they set out in our presence the very causes that moved them to this action, which, as they asserted, constrained them [to act] for the public good, which we considered should not be imputed as a crime to the present persons and [are] outside the case; [then] when diligent enquiry had been made into this, when all and singular matters which should be considered in a case of this kind and which touch on this case had been considered and discussed by prior and mature consideration of our council, we consider as excused the aforementioned Robert, our brother german, and Archibald, our son according to the laws, and anyone who took part in this affair with them, that is any who arrested, detained, guarded, gave them advice, and all others who gave them counsel, help or support, or executed their order or command in any way whatsoever, and in our said council we openly and publicly declared, pronounced and determined definitively and by the tenor of this our present document declare, pronounce, and by this definitive sentence judge them and each of them to be innocent, harmless, blameless, quit, free and immune completely in all respects from the charge of lese majesty against us, or any other crime, misdemeanour, wrongdoing, rancour and offence which could be charged against them on the occasion of the aforesaid. And if we have conceived any indignation, anger, rancour or offence against them or any of then, or any person or people participating with or adhering to them in any way, we now annul, remove and wish those things to be considered as nothing in perpetuity, by our own volition, from a certain knowledge, and from the deliberation of our said council. Wherefore we strictly order and command all and singular our subjects, of whatever standing or condition they be, that they do not slander the said Robert and Archibald and their participants, accomplices or adherents in this deed, as aforesaid, by word or action, nor murmur against them in any way whereby their good reputation is hurt or any prejudice is generated, under all penalty which may be applicable hereafter in any way by law. Given under testimony of our great seal in our monastery of Holyrood at Edinburgh on 20 May 1402 in the thirteenth year of our reign.

Pics are Falkland Palace and Lindores Abbey

I’ve only skimmed the surface of this story, if you want to read more about it, there is an excellent piece by Dr Callum Watson on his excellent blog here

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

MARY II // COUNTESS OF MANTEITH

“She was a Scottish noblewoman. Her father was Alan II, Earl of Menteith, who died c. 1330. She is believed to have agreed with her kinsman Muireadhach III, in 1330, that he should hold the Earldom, but when he was killed in August 1332, Mary assumed the title. She married Sir John Graham, who in her right became Earl of Monteith and assumed the title in May 1346. She died sometime prior to 29 April 1360. She was the mother of Margaret Graham, Countess of Menteith.”

0 notes

Text

2nd January 1264: Marriage and Murder in Mediaeval Menteith

(Priory of Inchmahome, founded on one of the islands of Lake of Menteith in the thirteenth century)

On 2nd January 1264, Pope Urban IV despatched a letter to the bishops of St Andrews and Aberdeen, and the Abbot of Dunfermline, commanding them to enquire into a succession dispute in the earldom of Menteith. Situated in the heart of Scotland, this earldom stretched from the graceful mountains and glens of the Trossachs, to the boggy carseland west of Stirling and the low-lying Vale of Menteith between Callander and Dunblane. The earls and countesses of Menteith were members of the highest rank of the nobility, ruling the area from strongholds such as Doune Castle, Inch Talla, and Kilbryde. Perhaps the best-known relic of the mediaeval earldom is the beautiful, ruined Priory of Inchmahome, which was established on an island in Lake of Menteith by Earl Walter Comyn in 1238. Walter Comyn was a powerful, if controversial, figure during the reigns of Kings Alexander II and Alexander III. He controlled the earldom for several decades after his marriage to its Countess, Isabella of Menteith, but following Walter’s death in 1258 his widow was beset on all sides by powerful enemies. These enemies even went so far as to capture Isabella and accuse her of poisoning her husband. The story of this unfortunate countess offers a rare glimpse into the position of great heiresses in High Mediaeval Scotland, revealing the darker side of thirteenth century politics.

Alexander II and Alexander III are generally remembered as powerful monarchs who oversaw the expansion and consolidation of the Scottish realm. During their reigns, dynastic rivals like the MacWilliams were crushed, regions such as Galloway and the Western Isles formally acknowledged Scottish overlordship, and the Scottish Crown held its own in diplomacy and disputes with neighbouring rulers in Norway and England. Both kings furthered their aims by promoting powerful nobles in strategic areas, but it was also vital to harness the ambition and aggression of these men productively. In the absence of an adult monarch, unchecked magnate rivalry risked destabilising the realm, as in the years between 1249 and 1262, when Alexander III was underage.

(A fifteenth century depiction of the coronation of Alexander III. Source: Wikimedia Commons)

Walter Comyn offers a typical picture of the ambitious Scottish magnate. Ultimately loyal to the Crown, his family loyalties and personal aims nonetheless made him a divisive figure. A member of the powerful Comyn kindred, he had received the lordship of Badenoch in the Central Highlands by 1229, probably because of his family’s opposition to the MacWilliams. In early 1231, he was granted the hand of a rich heiress, Isabella of Menteith. In the end, there would be no Comyn dynasty in Menteith: Walter and Isabella had a son named Henry, mentioned in a charter c.1250, but he likely predeceased his father. Nevertheless, Walter Comyn carved out a career at the centre of Scottish politics and besides witnessing many royal charters, he acted as the king’s lieutenant in Galloway in 1235 and became embroiled in the scandalous Bisset affair of 1242.

When Alexander II died in 1249, Walter and the other Comyns sought power during the minority of the boy king Alexander III. They were opposed by the similarly ambitious Alan Durward and in time Henry III of England, the attentive father of Alexander III’s wife Margaret, was also dragged into the squabble as both sides solicited his support in order to undermine their opponents. Possession of the young king’s person offered a swift route to power, and, although nobody challenged Alexander III’s right to the throne, some took drastic measures to seize control of government. Walter Comyn and his allies managed this twice, the second time by kidnapping the young king at Kinross in 1257. They were later forced to make concessions to enemies like Durward but, with Henry III increasingly distracted by the deteriorating political situation in England, the Comyns held onto power for the rest of the minority. However Walter only enjoyed his victory for a short while: by the end of 1258, the Earl of Menteith was dead.

Walter Comyn had dominated Scottish politics for a decade, and even if, as Michael Brown suggests, his death gave the political community some breathing space, this also left Menteith without a lord. As a widow, Countess Isabella theoretically gained more personal freedom, but mediaeval realpolitik was not always consistent with legal ideals. In thirteenth century Scotland, the increased wealth of widows made them vulnerable in new ways (not least to abduction) and, although primogeniture and the indivisibility of earldoms were promoted, in reality these ideals were often subordinated to the Crown’s need to reward its supporters. Isabella of Menteith was soon to find that her position had become very precarious.

At first, things went well. Although one source claims that many noblemen sought her hand, Isabella made her own choice, marrying an English knight named John Russell. Sir John’s background is obscure but, despite assertions that he was low born, he had connections at the English court. Isabella and John obtained royal consent for their marriage c.1260, and the happy couple also took crusading vows soon afterwards.

But whatever his wife thought, in the eyes of the Scottish nobility John Russell cut a much less impressive figure than Walter Comyn. The couple had not been married long before a powerful coterie of nobles descended on Menteith like hoodie-crows. Pope Urban’s list of persecutors includes the earls of Buchan, Fife, Mar, and Strathearn, Alan Durward, Hugh of Abernethy, Reginald le Cheyne, Hugh de Berkeley, David de Graham, and many others. But the ringleader was John ‘the Red’ Comyn, the nephew of Isabella of Menteith’s deceased husband Walter, who had already succeeded to the lordship of Badenoch. Even though Menteith belonged to Isabella in her own right, Comyn coveted his late uncle’s title there. Supported by the other lords, he captured and imprisoned the countess and John Russell, and justified this bold assault by claiming that the newlyweds had conspired together to poison Earl Walter. It is unclear what proof, if any, John Comyn supplied to back up his claim, but the couple were unable to disprove it. They were forced to surrender all claims to Isabella’s dowry, as well as many of her own lands and rents. A surviving charter shows that Hugh de Abernethy was granted property around Aberfoyle about 1260, but it seems that the lion’s share of the spoils went to the Red Comyn, who secured for himself and his heirs the promise of the earldom of Menteith itself.

Isabella and her husband were only released when they promised to pass into exile until they could clear their names before seven peers of the realm. John Russell’s brother Robert was delivered to Comyn as security for their full resignation of the earldom. Having ‘incurred heavy losses and expenses’, which certainly stymied their crusading plans, they fled.

In a letter of 1264, Pope Urban IV described the couple as ‘undefended by the authority of the king, while as yet a minor’. However, though Alexander III was technically underage in 1260, he was now nineteen and could not be ignored entirely. Michael Brown suggests that Isabella and her husband may have been seized when the king was visiting England, and that John Comyn’s unsanctioned bid for the earldom of Menteith may explain why Alexander cut short his stay in November 1260 and hastily returned north, leaving his pregnant queen with her parents at Windsor. Certainly, Comyn was forced to relinquish the earldom before 17th April 1261. But instead of restoring Menteith to its exiled countess, Alexander settled the earldom on another rising star: Walter ‘Bailloch’ Stewart, whose wife Mary had a claim to Menteith.

Mary of Menteith is often described as Isabella’s younger sister, although contemporary sources never say so and some historians argue that they were cousins. Either way, Alexander’s decision to uphold her claim was probably as much influenced by her husband’s identity as her alleged birth right. Like Walter Comyn, Walter Bailloch (‘freckled’), belonged to an influential family as the brother of Alexander, Steward of Scotland. From their origins in the royal household, the Stewarts became major regional magnates, assisting royal expansion in the west. The promising son of a powerful family, Walter Bailloch was sheriff of Ayr by 1264 and likely fought in the Battle of Largs in 1263. In 1260 Alexander III had the opportunity to secure Walter’s loyalty as the royal minority drew to a close. Conversely John Comyn of Badenoch found himself out of favour and was removed as justiciar of Galloway following the Menteith incident. The king would not alienate the Comyns permanently, but for now, the stars of Walter Bailloch and Mary of Menteith were in the ascendant.

(Loch Lubnaig, in the Trossachs, another former possession of the earls of Menteith)

Isabella of Menteith and John Russell had not been idle in the meantime. Travelling to John’s home country of England, they probably appealed to Henry III. In September 1261, the English king inspected documents relating to a previous dispute over the earldom of Menteith. On that occasion, two brothers, both named Maurice, had their differences settled before the future Alexander II at Edinburgh in 1213. The elder Maurice, who held the title Earl of Menteith and was presumed illegitimate by later writers (though this is never stated), resigned the earldom, which was regranted to Maurice junior. In return the elder Maurice received some towns and lands to be held for his lifetime only, and the younger Maurice promised to provide for the marriage of his older brother’s daughters.

It is probable that Isabella was the daughter of the younger Maurice, and that she produced these charters as proof of her right to the earldom. Perhaps Mary was her younger sister, but it seems likelier that Isabella would have wanted to prove the younger Maurice’s right if Mary was a descendant of the elder brother, and therefore her cousin. However despite Henry III’s formal recognition of the settlement, he did not provide Isabella with any real assistance: for whatever reason, the English king was either unable or unwilling to press his son-in-law the King of Scots on this matter. Isabella then turned instead to the spiritual leader of western Europe- Pope Urban IV.

(A depiction of the coronation of Henry III of England, though in fact the English king was only a child when he was crowned. Source: Wikimedia Commons)

A long epistle which the pope sent to several Scottish prelates in January 1264 has survived, revealing much about the case. Thus we learn that Urban was initially moved by Isabella and her husband’s predicament, perhaps especially so since they had taken the cross. Accordingly, he had appointed his chaplain Pontius Nicholas to enquire further and discreetly arrange the couple’s restoration. Pontius was to journey to Menteith, ‘if he could safely do so, otherwise to pass personally to parts adjacent to the said kingdom, and to summon those who should be summoned’. But Pontius’ mission only hindered Isabella’s suit. According to Gesta Annalia I, the papal chaplain got no closer to Scotland than York. From there he summoned many Scottish churchmen and nobles to appear before him, and even the King of Scots himself. This merely antagonised Alexander III and his subjects. Although Alexander maintained good relations with England and the papacy throughout his reign, he had a strong sense of his own prerogative and did not appreciate being summoned to answer for his actions, especially not outwith his realm and least of all in York. Special daughter of the papacy or not, Scotland’s clergy and nobility supported their king and refused to compear. Faced with this intransigence, Pontius Nicholas placed the entire kingdom under interdict, at which point Alexander retaliated by writing directly to the chaplain’s boss, demanding Pontius’ dismissal from the case.

Urban IV swiftly backpedalled. In a conciliatory tone he claimed that Pontius was guilty of ‘exceeding the terms of our mandate’ and causing ‘grievous scandal’. To remedy the situation, and avoid endangering souls, the pope discharged his responsibility over the case to the bishops of St Andrews and Aberdeen, and the Abbot of Dunfermline. Thus the pope washed his hands of a troublesome case, the Scottish king’s nose could be put back in joint, and Isabella’s suit was transferred to men with great experience of Scottish affairs, who should have been capable of satisfactorily resolving the matter. However, there is no indication that Isabella was ever compensated for the loss of her inheritance, and when the dispute over Menteith was raised again ten years later, the countess was not even mentioned (probably she had since died). Possibly her suit was discreetly buried after it was transferred to the Scottish clerics, a solution which, however frustrating for the exiled countess, would have been convenient for the great men whose responsibility it was to ensure justice was done.

(Doune Castle- the earliest parts of this famous stronghold probably date to the days of the thirteenth century earls of Menteith, although much of the work visible today dates from the late fourteenth and early fifteenth centuries)

The Comyns could not be dismissed so easily. Never resigned to losing Menteith, John Comyn of Badenoch claimed the earldom again c.1273, on behalf of his son William Comyn of Kirkintilloch. William had since married Isabella Russell, daughter of Isabella of Menteith by her second husband.* The 1273 suit was unsuccessful but William Comyn and Isabella Russell did not lose hope, and in 1282, William asked Edward I of England to intercede for them with the king of Scots. In 1285, with William’s father John Comyn long dead, Alexander III finally offered a compromise. Walter Bailloch, whose wife Mary may have died, was to keep half the earldom and he and his heirs would bear the title earl of Menteith. William Comyn and Isabella Russell received the other half in free barony, and this eventually passed to the offspring of Isabella’s second marriage to Sir Edward Hastings. Perhaps this could be seen as a posthumous victory for Isabella Russell’s late parents, but their descendants would never regain the whole earldom (except, controversially, when the younger Isabella’s two sons were each granted half after Edward I forfeited the current earl for supporting Robert Bruce).

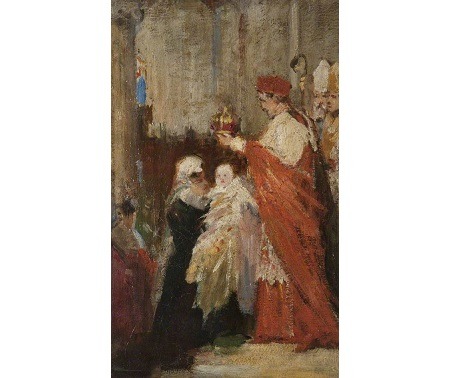

Conversely, Walter Bailloch’s descendants remained at the forefront of Scottish politics. He and his wife Mary accompanied Alexander III’s daughter to Norway in 1281, and Walter was later a signatory to both the Turnberry Band and the Maid of Norway’s marriage negotiations. He also acted as a commissioner for Robert Bruce (grandfather to the future king) during the Great Cause. He had at least three children by Mary of Menteith and their sons took the surname Menteith rather than Stewart. The descendants of the eldest son, Alexander, held the earldom of Menteith until at least 1425. The younger son, John, became infamous as the much-maligned ‘Fause Menteith’ who betrayed William Wallace, although he later rose high in the service of King Robert I. Walter Bailloch himself died c.1294-5, and was buried next to his wife at the Priory of Inchmahome on Lake of Menteith, which Walter Comyn had founded over fifty years previously. The effigies of Walter Bailloch and Mary of Menteith can still be seen in the chapter house of the ruined priory: the worn faces are turned towards each other and each figure stretches out an arm to embrace their spouse in a lasting symbol of marital affection.

(The effigies of Walter Bailloch and Mary of Menteith at Inchmahome Priory, which was founded by Walter Comyn in 1238 and was perhaps intended as a burial site for himself and his wife Isabella of Menteith. Source: Wikimedia Commons).

The dispute over Menteith saw a prominent noblewoman publicly accused of murder and exiled, and even sparked an international incident when Scotland was placed under interdict. For all this, neither Isabella of Menteith nor John Comyn of Badenoch triumphed in the long term. Even Walter Bailloch eventually had to accept the loss of half the earldom after holding it for over twenty years. In the end the only real winner seems to have been the king. Although at first sight the persecution of Isabella and her husband looks like a classic example of overmighty magnates taking advantage of a breakdown in law and order during a royal minority, Alexander III was not a child and his rebuke of John Comyn did not result in any backlash against the Crown. Most of the Scottish nobility fell back in line once the king came of age, but the king in turn had to ensure that he was able to reward key supporters if he wanted to expand the realm he had inherited. Although it was important to both Alexander III and his father that primogeniture and were accepted by their subjects as the norm, in practice both kings found that they had to bend their own rules to ensure that the system worked to their own advantage. The thirteenth century is often seen an age of legal development and state-building, but these things sometimes came into conflict with each other, and even the most successful kings had to work within a messy system and consider the competing loyalties and customs of their subjects.

Selected Bibliography:

- “Vetera Monumenta Hibernorum et Scotorum”, Augustinus Theiner (a printed version of Urban IV’s original Latin epistle may be found here)

- “John of Fordun’s Chronicle of the Scottish Nation”, vol. 2, ed. W.F. Skene (this is an English translation of the chronicle of John of Fordun, made when Gesta Annalia I was still believed to be his work. It provides an independent thirteenth or fourteenth century Scottish account of the Menteith case

- “The Red Book of Menteith”, volumes 1+2, ed. Sir William Fraser

- “Calendar of Documents Relating to Scotland, Preserved Among the Public Records of England”, volumes 1, 2, 3 & 5, ed. Joseph Bain

- “The Political Role of Walter Comyn, earl of Menteith, during the Minority of Alexander III of Scotland”, A. Young, in the Scottish Historical Review, vol.57 no.164 part 2 (1978).

- “Scotland, England and France After the Loss of Normandy, 1204-1296″, M.A. Pollock

- “The Wars of Scotland, 1214-1371″, Michael Brown

As ever if anyone has a question about a specific detail or source, please let me know! I have a lot of notes for this post, so hopefully I should be able to help!

#Scottish history#Scotland#British history#thirteenth century#women in history#Menteith#earldom of Menteith#Isabella Countess of Menteith#John Russell#John Comyn I of Badenoch#Alexander III#Henry III#Pope Urban IV#Walter Bailloch#the Stewarts#House of Dunkeld#House of Canmore#Mary of Menteith#inchmahome priory

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Henry Is Upset At Me

Obviously Mary of Guise didn’t have a Glaswegian accent (being, oddly enough, French) but sometimes I can’t help feeling like some of her interactions with the political community would have had the Same Energy as those Janey Godley voiceovers of an increasingly irked Sturgeon dealing with Covid

“Hi folks, c’est moi Queen Marie, wearing my black hood and kirtle combo the day. It’ll be me subbing in for wee Jamie Hamilton again cos he’s still no figured oot how tae get the microphone tae work, so let’s make this quick. Youse have been telt before aboot taking the English bribes- youse have no tae dae it, ah dinnae care if that Ralph Sadler says it’s no really betrayin’ yer country, it’s no gonnae end well and it’s got tae stop. And anither thing, see thae lads that’ve been playin’ at the fitba in ma chambers when ah’ve got guests roond- ah’ve had enough. How dae youse think it looks when ah’m tryin’ tae get aw the goss frae the French ambassador about whit Big Diane and that lassie that’s Frankie’s sidepiece are gonnae get up tae next and youse are aw runnin’ aboot the place doin’ heiders? Onyweys youse have had yer chance, ah’m taking the baw aff ye, and ah’m bootin’ it up in tae the roof. Right that’s aw the day folks, that’s us oot ae here, me and aw the Janets are away up tae Menteith for the weekend. François ouvre la porte! Je veux un tattie scone...”

#Mary of Guise#Scotland#I'm never sure how to type Scots when it comes to Glasgow- I want to write a' and ba' and o' instead of aw and baw and ae#But it just ends up looking really east coast#But at least it's better than my French which is ah how you say non-existent#Oh well it's not like Mary of Guise would have spoken like that anyway#Obvs I'm just nicking Janey Godley's material now but I had to share it#Creating a wee mythology for the Stirling Smith football

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tomb effigy of Walter Stewart, 1st Earl of Menteith, and his wife Mary, late 13th century. Inchmahome Priory, Lake Menteith, Scotland.

Very unusual effigy showing them side by side gazing towards each other, with her arm around him, and his whole body facing her. I've never seen another like this.

0 notes

Text

Rattray Libbie VA

New Post has been published on https://nerret.com/netmyname/rattray-libbie/rattray-libbie-va/

Rattray Libbie VA

Rattray Libbie VA Top Web Results.

www.tobaccoreviews.com Rattray – All Blends

1724 reviews of Rattray pipe tobacco. … Showing 40 blends for Rattray. … 40

Virginia, 10, 2.6, 0, Virginia/Burley. 7 Reserve, 62, 2.6, 4, English.

www.vliz.be Cumulated Bibliography of Biographies of Ocean Scientists

Nov 24, 1995 … University of Virginia Press. …… Libbie Henrietta Hyman, December 6, 1888-

August 3, 1969. …… Moore, C.R. Frank Rattray Lillie 1870-1947.

longislandgenealogy.com East Hampton

JEANNETTE EDWARDS RATTRAY. EAST HAMPTON, LONG …… Laura Virginia

Candy, she b. Feb. 14, 1842, d. June 2 … 1898 ae 76. Ch. by 1st w.: Libbie M. 9.

www.biodiversitylibrary.org Browse MBLWHOI Library – Biodiversity Heritage Library

Aerial observation of Gulf Stream phenomena Virginia Capes area, October 1968

-May 1969 / …… By: Lillie, Frank Rattray, – Moore, Carl Richard – Redfield, Alfred

C. (Alfred Clarence) – Marine Biological …… By: Hyman, Libbie Henrietta,.

jefferson.nygenweb.net Clayton Marriages: 1886-1888

9 FEB 1886, RATTRAY,EDWARD R. 28, WOLF ISLAND, FARMER, WOLFE

ISLAND, RATTRAY,WILLIAM, FARR,CATHERINE, HORNE,ISADORE, 22,

WOLFE …

www.doig.net The Dogs of Menteith, Perthshire, Scotland – Doig, Doeg, Doigg …

FOWLER in Calif and Martin Fowler – Virginia. 831 F iii. …… (tailoress), son Burtie

(at school), and another tailoress Libbie Bustis, age 28 from. Canada. …… William

Rattray Doig was born in 1885 in Blythswood, Glasgow, Lanark, Scotland.

www.killingly.org PID # ADRSTR OWN1 Prior New 008774 36 SPRING ST 166 …

BARBEE VIRGINIA A. 17,290. 13,510. 000204 …… DEOJAY JASON N & LIBBIE

JO W. 285,250. 214,760 …… RATTRAY JACKIE G & DEBBIE L. 129,990. 98,980.

web.csulb.edu BRENT C. DICKERSON SHEET MUSIC COLLECTION

Morris Co., Philadelphia. Erickson, Libbie. —Topsy. … —Virginia Beauties. March

& Two Step. Published by …… Rattray, Alan M. —Bottle O! Schottische Barn …

www.jic.ac.uk History of Genetics Book Collection held at the John Innes Centre …

Oct 30, 2007 … Morell Virginia Ancestral passions the Leakey family and the Quest for ……

Hyman Libbie Henrietta Comparative Vertebrate Anatomy Chicago The ……

Taylor Gordon Rattray The biological time-bomb London Book Club …

abbygs.ca CHILLIWACK CEMETERY INDEX Surname Given Names Birth …

Wayne Byron. Dec. 25 1980. 091 – 01. Carman United. BRYAN. Libbie. 1867. Apr

. 19 1942. 092 – 01 ….. 2002. A-6-14. St. Mary's. CURRIE. VA Merle. 1898. Sep.

10 1997. 014 – 07. Carman United. CURRY …… RATTRAY. Donald A. 1921. 2000

.

0 notes

Photo

Happy Birthday "Celebrity" Chef Nick Nairn, who turns 62 today.

Born January 12th 1959 in Stirling, Nick grew up in the village of Port of Menteith and attended McLaren High School in Callander before joining the merchant navy at the age of 17 in 1976, serving as a navigator until 1983.

During his travels as a navigator, Nick developed a passion for food and the exotic dishes he'd experienced on his travels, and this proved to be the driving force behind his desire to teach himself to cook. In 1986 he opened his first restaurant, which won him the Scottish Field and Bollinger Newcomer of the Year Award. Four years later he became the youngest chef to earn a Michelin star for his restaurant in Scotland.

After this he went on to open Nairns restaurant in Glasgow in 1998 and a cook school in 2000 at Lake of Menteith. In 2003, he sold his restaurant in Glasgow to concentrate on the cookery school, although he also undertakes a range of corporate work.

Nick was awarded an honorary doctorate by the University of Stirling in 2007 for his contributions to Scottish cooking and healthy eating campaigns. He was awarded a second honorary doctorate from Abertay University in June 2016.

From restaurateur to celebrity chef, Nick Nairn has had a long and pioneering career in the UK food industry. A familiar face due to his many high-profile television appearances, Nick is equally famous for his staunch support of top quality Scottish produce, and passionate advocacy of healthy eating.

Just two weeks before the world shut down last March, Nick had opened his new restaurant in the town of Bridge of Allan, where he now lives. While the venture right now will be losing him a lot of money he has his Tv career to keep the wolf from the door and has been on our screens along with Deacon Blue drummer Dougie Vipond in The Great Food Guys.

While the hospitality business has been one of the industries hardest hit Nick has shown his charitable side by cooking up complimentary grub at his Nick’s on Henderson Street restaurant for those struggling neighbours.

The celebrity chef has also supported Street Soccer Scotland, which helps socially disadvantaged people through football, although I have no idea why they use the US term Soccer!???Nick and Edinburgh born chef Tom Kitchin also support the charity Mary's Meals which helps provide chronically hungry children with one meal every school day.

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

9th September 1543- Coronation of Mary I of Scotland

On 9th September 1543, the coronation of Mary I of Scotland took place in the Chapel Royal of Stirling Castle. An infant of barely nine months, she had been recognised as the kingdom’s next monarch at just six days old, after the premature death of her father King James V, leaving no other legitimate heirs of his body. She had been described as queen of Scotland in most official government documents since, but her official coronation was preceded by nine months of political intrigue and tension, culminating in a double-edged triumph for the faction led by her mother, Mary of Guise, and Cardinal Beaton.

The little queen had been resident in Stirling for just over a month. At the end of July 1543, her mother, the dowager queen Mary of Guise, supported by Cardinal Beaton along with the Earls of Huntly, Argyll, Lennox, Bothwell, Sutherland, Menteith, lords Erskine, Ruthven, Fleming, Crichton, Drummond, Lisle, Hume, the bishops of Moray, Orkney, Galloway, Dunblane, and several thousand others, had finally succeeded in removing her from her birthplace in the palace of Linlithgow. This was achieved in the face of opposition from the Governor of Scotland, James Hamilton, Earl of Arran. Arran was the infant queen’s 27 year old cousin and the official head of the Scottish government as regent and the next in line to the throne. As he was then pursuing a pro-English policy, and also had reason to view both the dowager queen and Cardinal Beaton as rivals, in early 1543 he had had the Cardinal arrested and forbade Mary of Guise to leave Linlithgow for the greater protection of Stirling. However, following the Cardinal’s escape and the return of the Earl of Lennox from France in 1543, the opponents of the Governor (or at least the opponents of his policy in favour of an alliance with England) gathered an army and marched on Linlithgow. After several days of stalemate and negotiation, with the army sitting outside the palace walls, Arran had been forced to climb down and allow the little queen and her mother to leave.

The sudden flitting of the queen was an even greater source of displeasure to Henry VIII of England when he heard of it, as the English king had not only wished to marry her to his son the Prince of Wales, but had also wanted the queen to be kept in England until the marriage could take place. This would have served as a useful means of keeping the Scots in check, and anyway, despite their promises, he certainly did not trust her French mother to follow through with the English marriage, much less the wily pro-French and militantly Catholic Cardinal Beaton. Linlithgow would have suited Henry better as then there was at least a chance that one of the Scottish nobles he had attempted to suborn, or even an English invasion, would have been able to abduct the young queen from the beautiful, yet low-lying and relatively unprotected lochside palace. Stirling Castle was another matter entirely: perched on its high rock with a commanding view of the surrounding country, its Renaissance embellishments had not diminished its status as a formidable fortress, the veteran of many bitter Anglo-Scottish conflicts. Nevertheless, Henry VIII could live in hope. The Treaty of Greenwich might yet be ratified to his satisfaction, and the Scottish nobles who favoured alliance with the English king, whether for political or religious reasons, had managed to bring the Governor Arran round to his point of view, which lent their policy official authority.

(An engraving of the Earl of Arran in his later years, and probably his most famous picture, which tends to obscure the age he was when he became Regent. Not my picture)

But any plan which rested on the consistent cooperation of the chronically indecisive Governor Arran could hardly be called secure. The Governor was already under pressure from his half-brother John Hamilton, Abbot of Paisley, an ardent Catholic who had recently returned from abroad and set about putting the fear of god into his pliable younger sibling over Arran’s recent support of Protestantism. Meanwhile the mood of the country was also shifting, and the English alliance was becoming increasingly unpopular, not least due to the disturbing effects of religious unrest in Scotland and Henry VIII’s not so thinly veiled intimidation tactics. Arran’s allies soon had reason to become wary of his behaviour and watched his movements closely. On 1st September 1543, the English Ambassador Sir Ralph Sadler wrote to his king and said of the Governor that, “he abides not long in one mind, and Sir George Douglas tells me that he much fears the Governor’s revolt, now that things grow to extremity, and that there is a great likelihood that this division will not be ended nor exterminated but by the sword. The Governor is so afraid, of so weak spirit, and faint hearted, that (...) he fears he will never abide the extremity of it, but will rather slip from them and beastly put himself into the hands of his enemies, to his own utter confusion.”

The Earl of Arran’s anxiety was perhaps understandable. He might have feared for his position as governor if the Stirling lords decided to choose a different governor at the coronation, as the event could serve as a major political coup for Cardinal Beaton and the dowager queen. Or perhaps it was the presence of the Earl of Lennox at Stirling which disturbed Arran as Lennox had a rival claim to be next in line to the throne. Perhaps, indeed, as Marcus Merriman argues, Arran was acting with uncharacteristic farsightedness, seeing that the collapse of the English marriage was inevitable almost immediately after the queen’s removal to Stirling, and yet delaying his defection long enough to put off English invasion until the harvest had been brought in and the best time for campaigning had passed. Although Arran ratified the Treaty of Greenwich which promised Queen Mary’s hand to Henry VIII’s son on 25th August 1543, this was to be the high watermark of his active support for the English alliance. Despite the English king’s last-ditch offer of a marriage between his daughter, Princess Elizabeth, and Arran’s son, and despite the careful watch set by his former allies and the blandishments of his own wife Margaret Douglas, Arran changed sides in the first week of September. On Monday 3rd September, he slipped away to Blackness Castle on the Forth, claiming that his wife was in labour there. But the next morning Arran departed from the castle again, leaving Margaret weeping tears of rage at his inconstancy, and he soon covered the ten miles or so to Lord Livingston’s residence at Callendar House, on the edge of Falkirk. There he met with the wily Cardinal Beaton and the Earl of Moray (the infant queen’s uncle), and after long discussion accompanied them back to Stirling that night.

(An eighteenth century copy of a portrait of David Beaton, Archbishop of St Andrews and Cardinal. Not my picture)

With the Governor’s ‘revolt’ accomplished, there was much to be discussed between Arran and his new, if not exactly beloved, allies. Arrangements had to be made for the secure keeping of the queen’s person during her time at Stirling, and also for the bairn’s coronation which was set for the coming Sunday, the 9th of September. Letters were sent to those recalcitrant Scottish nobles who- whether for reasons of religion, sound policy, or personal gain- had favoured the English marriage, asking them to attend the coronation. And there was spiritual work to be done as well: the lords at Stirling having agreed that Arran was “accurst” , it was determined that he should do penance for his previous flirtation with Protestantism. This was performed on Saturday the 8th of September in Stirling Greyfriars, when the earls of Bothwell and Argyll held the ‘towel’ over the humbled Governor’s head as the Cardinal and other bishops solemnly absolved him of his sin.

The coronation was due to take place early the next day, and the inner close of Stirling Castle must have been a hub of activity that September morning. The Chapel Royal, in which the event was to be held, stood on the north side of the close, forming a quadrangle with the King’s Old Buildings to the west, the magnificent Great Hall constructed by James IV to the east, and the mint-new royal palace (begun by Queen Mary’s father James V and to be completed by her mother over the next few years) standing to the south. The Chapel itself stood a little to the south of the current chapel (built by Mary’s son James VI in 1594) which now occupies the spot. It had been founded by James IV in 1501 and would witness several royal christenings and other notable events over the course of its short history. Perhaps most poignantly, it had also been the site of the coronation of Mary’s father James V, almost thirty years earlier in September 1513. This was the so-called ‘Mourning Coronation’ and the king on that occasion had also been little more than an infant. Had anyone called to mind this other coronation thirty years later, they might also have realised that the 9th of September 1543 was itself a significant date, being the thirtieth anniversary of the disastrous Battle of Flodden. This battle had caused the death of the new queen’s grandfather King James IV (also the Earl of Moray’s father and Huntly’s grandfather), her uncle Alexander Stewart who was one of Cardinal Beaton’s predecessors as Archbishop of St Andrews, the grandfathers of the earls of Lennox and Argyll, the father of the Earl of Bothwell, and countless other Scots of all classes. If anyone noticed this singularly inauspicious date however, it does not seem that it was allowed to throw a sombre shadow over proceedings.

(The only view I could find of most of the Inner Close of Stirling Castle- James V’s palace is to the right, James IV’s Great Hall in the centre, and on the left can be seen parts of the current Chapel Royal, built in 1594 by Mary’s son James VI almost on the same site as the Chapel Royal where she was crowned. Not my picture.)

Not much is known about the details of the coronation itself, which took place around ten o’clock in the morning, once the assembled lords and ladies had filed into the Chapel Royal. The Treasurer’s Accounts are unusually silent about the occasion, though it was probably carried out with as much propriety and careful observance of etiquette as was possible given the circumstances. We do know that Cardinal Beaton presided over the ceremony, and that the Earl of Arran bore the Crown, the Earl of Lennox the sceptre, and the Earl of Argyll the sword. These precious royal items- now known as the Honours of Scotland and still to be seen in Edinburgh Castle- each had their own story. The sceptre and sword had been gifted to King James IV by two separate popes, while the crown was of dubious but likely ancient origin (give or take a few meltings) possibly stretching back to the days of Robert Bruce, and it had been refashioned as recently as 1540 on the orders of Mary’s father. A heavy crown for a bairn, it was probably held above her head. There is a tradition that the infant queen cried all through the ceremony but otherwise the coronation went off without a hitch.

In terms of coronation festivities, it must be said that even when taking into account the natural bias of the English ambassador, and the fact that he was not at the coronation himself (being unable to stray far from his house in Edinburgh without fear of the mob), it is hard to disagree with his assertion that Queen Mary was crowned, “with such solemnity as they do use in this country, which is not very costly”. There were to be no ceremonial entries, no elaborate pageantry such as had been planned for the coronations of James V’s consorts in the 1530s. As with most other recent Scottish coronations, which had a funny little knack of coming at the worst possible moment to kings who had hardly reached knee height, simple dignity was probably the order of the day. The late-sixteenth century writer Robert Lindsay of Pitscottie does state that the guests retired after the coronation and occupied themselves in dancing and merry-making however, so possibly there was more cheer than the records indicate.

There was also no escaping from the harsh reality of the political situation. This coronation had been a political triumph for Cardinal Beaton and Mary of Guise and their supporters, but there were notable absences, not least the Earls of Glencairn, Cassilis and Angus, Lord Maxwell and the other lords still considered to be of the ‘English’ party. And there would have to be a reckoning with the king of England as well, especially after the Treaty of Greenwich was finally overturned by the Scottish parliament in December 1543. The events of 1543 would lead to the devastating period of Anglo-Scottish warfare which is nicknamed ‘the Rough Wooing’, and as a result of this, within five years of her coronation, the Queen of Scots was sent away from her kingdom to the safety of France. She would not return for thirteen years.

(Mary I in childhood, as painted by Clouet. Not my picture)

Selected references:

Acts of the Parliaments of Scotland

“Acts of the lords of council in public affairs, 1501-1554: Selections from the Acta dominorum concilii”, ed. R.K. Hannay

“Scottish Correspondence of Mary of Lorraine”, ed. Annie Dunlop

“Letters and Papers, Foreign and Domestic of the Reign of Henry VIII”, Volumes 17 and 18, ed. James Gairdner and R. H Brodie.

“The Hamilton Papers”, Vol. II, ed. Joseph Bain

The various histories of John Leslie, George Buchanan, Robert Lindsay of Pitscottie and John Knox- all of which can be found online but as only Lindsay was really useful, forgive me for not citing them properly here

“Mary of Guise”, by Rosalind Marshall

“Mary Queen of Scots”, by Antonia Fraser

“The Rough Wooing”, by Marcus Merriman

“Glory and Honour”, by Andrea Thomas

“Life of Mary Queen of Scots”, by Agnes Strickland (I hate admitting it but I do have to credit her)

And others

#Scottish history#Mary Queen Of Scots#Scotland#British history#women in history#sixteenth century#Mary of Guise#Cardinal Beaton#Regent Arran#Henry VIII of England#stirling castle#Linlithgow Palace#Blackness Castle#Callendar House#the Stewarts#coronation#today in history

88 notes

·

View notes

Text

I’m supposed to be researching and writing a post on the unfortunate experiences of Isabella, Countess of Menteith and her English husband John Russel, but to my brain it also just seems like a really good opportunity to correct and edit a five year old post on Mary of Guelders for the hundredth time

#In all fairness Maria van Egmond was pretty dope#And I hate that my post isn't 100% perfect#Even though I learn all the time so how could it be#Nope constant editing is the only way forward#Especially since I'm very excited by the history of Guelders right now

2 notes

·

View notes

Link

On March 26th 1402, heir to the Scottish throne, David Stewart, 1st Duke of Rothesay, died in mysterious circumstances at Falkland Palace.

This event in Scottish history ties in with James I being sent to France and falling into English hands, I covered that part in a post a few days ago.

David Stewart was the oldest son of Robert III of Scotland and Anabella Drummond and was born on 24 October 1378. At the time of his birth, his grandfather, Robert II still occupied the Scottish throne. His father became King of Scotland in November 1384, when his earldom of Carrick passed to David.

In 1398, David was created Duke of Rothesay by his father. In the following year, at the age of 21, due to the infirmity of his father the king, he was appointed "Lieutenant" of Scotland by Parliament, to rule in his father's place. The arrangement had been urged by his mother, Queen Annabella, to ensure her son succeeded his ailing father. His uncle, Robert Stewart, a ruthless politician with designs on the throne himself, had previously been protector of the kingdom.

In 1395, David married Elizabeth Dunbar, the daughter of George Dunbar, Earl of March, but the Papal dispensation required because they were close relatives was never obtained, and in 1397 the couple separated.

David later married Mary Douglas, daughter of Archibald Douglas, 3rd Earl of Douglas, to form an alliance with the Douglases, which gravely offended George Dunbar. Dunbar accordingly switched his allegiance to Henry IV of England, who then invaded Scotland, briefly capturing Edinburgh before returning to England.

Following the death of his mother in 1401, David failed to consult his council, as he was required to do, before making a series of decisions that were seen to threaten the positions of his nobles, especially his uncle, Robert Stewart, 1st Duke of Albany.

In February 1402, while travelling to St Andrews, David was arrested just outside the city by Sir John Ramornie and Sir William Lindsay of Rossie, agents of his uncle Albany, who at that time was in alliance with Archibald, fourth Earl of Douglas. David's father-in-law, the third Earl, had died two years previously, in 1400.

He was initially held prisoner in St Andrews Castle, but soon afterwards was taken to Falkland Palace, Albany's residence in Fife. David spent the journey hooded and mounted backwards on a mule.

David remained a prisoner and shortly after died in the dungeons of Falkland Palace, reputedly of starvation.

A few weeks later, in May 1402, a public enquiry into the circumstances of David's death, largely controlled by Albany, exonerated him of all blame concluding that David had died "by divine providence and not otherwise" and commanded that no one should 'murmur against' Albany and Douglas.

The following is taken from the records of the Scottish Parliament 16 May 1402

Letters: narrating the inquest into the death of David Stewart, duke of Rothesay and the role of Robert Stewart, duke of Albany, and Archibald Douglas, earl of Douglas.

Robert, by the grace of God king of Scots, to all to whose notice the present letters shall come, greeting. Whereas recently, our most beloved Robert [Stewart, 1st] duke of Albany, earl of Fife and Menteith, our brother german, and Archibald [Douglas, 4th] earl of Douglas and lord of Galloway, our son according to law by reason of our daughter who he took as wife, caused our very beloved firstborn son the late David [Stewart, 1st] duke of Rothesay and earl of Fife and Atholl, to be captured and personally arrested, and first to be guarded in St Andrews castle and then to be detained in keeping at Falkland, where, by divine providence and not otherwise, it is discerned that he departed from this life; they, compearing in our presence in our general council begun at Edinburgh on 16 May 1402 and continued for several days, and interrogated or accused upon this by our royal office of the capture, arrest, death as is expressed above etc., in this manner, confessing everything that followed thereafter, they set out in our presence the very causes that moved them to this action, which, as they asserted, constrained them [to act] for the public good, which we considered should not be imputed as a crime to the present persons and [are] outside the case; [then] when diligent enquiry had been made into this, when all and singular matters which should be considered in a case of this kind and which touch on this case had been considered and discussed by prior and mature consideration of our council, we consider as excused the aforementioned Robert, our brother german, and Archibald, our son according to the laws, and anyone who took part in this affair with them, that is any who arrested, detained, guarded, gave them advice, and all others who gave them counsel, help or support, or executed their order or command in any way whatsoever, and in our said council we openly and publicly declared, pronounced and determined definitively and by the tenor of this our present document declare, pronounce, and by this definitive sentence judge them and each of them to be innocent, harmless, blameless, quit, free and immune completely in all respects from the charge of lese majesty against us, or any other crime, misdemeanour, wrongdoing, rancour and offence which could be charged against them on the occasion of the aforesaid. And if we have conceived any indignation, anger, rancour or offence against them or any of then, or any person or people participating with or adhering to them in any way, we now annul, remove and wish those things to be considered as nothing in perpetuity, by our own volition, from a certain knowledge, and from the deliberation of our said council. Wherefore we strictly order and command all and singular our subjects, of whatever standing or condition they be, that they do not slander the said Robert and Archibald and their participants, accomplices or adherents in this deed, as aforesaid, by word or action, nor murmur against them in any way whereby their good reputation is hurt or any prejudice is generated, under all penalty which may be applicable hereafter in any way by law. Given under testimony of our great seal in our monastery of Holyrood at Edinburgh on 20 May 1402 in the thirteenth year of our reign.

I've only skimmed the surface of this story, if you want to read more about it, there is an excellent piece by Dr Callum Watson on his blog here

https://drcallumwatson.blogspot.com/2018/05/by-divine-providence-and-not-otherwise.html

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Also also, in other news, the Cutest Thing which is the effigy of Walter Bailloch and Mary, Countess of Menteith, in Inchmahome Priory

#Yes married couples were sometimes depicted in poses of romantic love as a generic pose that doesn't necessarily indicate real affection#But STILL#I see it I go aawwwww#Aggressive thirteenth century magnates and their heiress wives can still be cute#In a warped kind of way#Inchmahome is a beautiful spot already- and much associated with legends of Queen Mary and Robert Bruce#But this effigy I think is underrated as one of its greatest treasures#Arundel tomb who#(For real though the Arundel tomb is much more beautiful artistically but we have so little in Scotland let us have this)

2 notes

·

View notes