#John Comyn I of Badenoch

Text

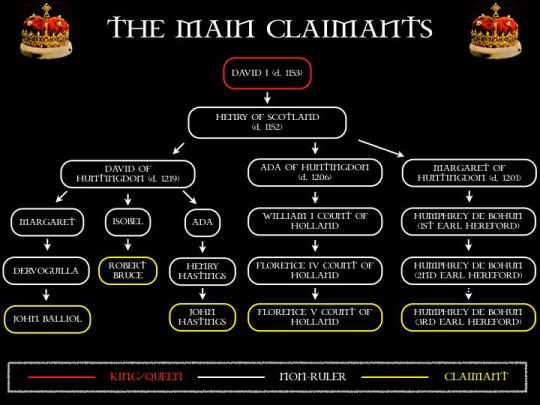

May 30th 1291 saw claimants to the Scottish throne meet King Edward I of England at Norham on Tweed to resolve succession, this became known as The Great Cause.

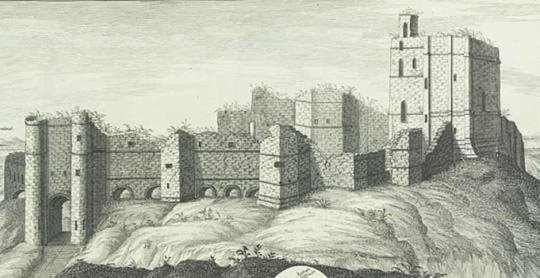

Bishop Anthony Beck entertained Edward I and his advisers at the castle while the king arbitrated between 13 competitors for the Scottish throne. Judgment was made in favour of John Baliol in 1292 at Berwick Castle, and three days later Baliol paid homage to Edward in the hall at Norham.

Following a period of prosperity for the Scottish Kingdom, tragedy struck when,in 1286, Alexander III died and left no heir. The nobles of Scotland agreed to oversee the coronation of Alexander’s granddaughter Margaret, Maid of Norway, as well as selecting a regent to rule and a husband for her to marry.

In the meantime, in order for the kingdom to function properly, ‘Guardians of the Realm’ had to be appointed.

The men chosen were: the Bishops Fraser of St Andrews and Wishart of Glasgow, the barons John Comyn of Badenoch and James Steward, and the Earls of Buchan and Fife. It was agreed amongst the Guardians that the nobility of the realm would swear an oath of loyalty of the young queen, but in the meantime they would rule in the name of the Scottish crown.

Tragedy struck when Margaret died travelling from Norway to Scotland. This left the future of the Scottish Kingdom in jeopardy as without her, the Treaty of Birgham was meaningless.

Edward I was informed, by the Bishop of St. Andrews, that Robert Bruce and the Earls of Athol and Mar were scheming and that war was a distinct possibility. The bishop asked Edward for assistance in order to stop a civil war. Bishop Fraser clearly favoured Balliol, but Bruce and his followers appealed to Edward by writing the ‘Appeal of the Seven Earls.’

At Norham, Edward showed his intentions of being made Overlord of Scotland, demanding that the Scots make him their feudal overlord before he would make any judgement on who would become the new King of Scots.

The Scots were worried because Edward had a large military presence with him. The Guardians replied stating that only a king could deal with such a demand which could only happen after Edward had selected one.

Edward wrote to English monasteries asking them to search for legal evidence in their documents for English overlordship over Scotland. He also threatened to blockade Scottish ports with his navy and summoned men to form an army.

Fourteen claimants petitioned Edward for the throne of Scotland, but two emerged as having serious claims – John Balliol and Robert Bruce. To make sure that he became overlord of Scotland, Edward demanded that all the claimants accept this before he would pass judgement. This agreement is known as the 'Award of Norham’.

The Award of Norham was an important acknowledgement. It gave legal possession of the Kingdom of Scotland to Edward and meant that it was his to give away.

This was not what the Guardians had intended – Edward had totally outmanoeuvred them. They were furious! Edward had moved from being a neutral observer choosing between the two main rivals to being a judge with the right to give away their kingdom!

Technically this made Edward the legal owner of Scotland, the English King was a very clever man and one of the top legal minds of the time

Everyone had agreed to Edward’s demand, although it was understood that their oaths would revert to the new king once he was chosen. This was probably the reason he would take so long to make his decision .It would be easier for him to hold on to the legal position of overlord after a longer period of time.Historians point out that the longer Edward was overlord, the harder it would be for the new king to establish his authority .Once Edward’s authority was agreed, a court was set up and the investigation of the claims to the throne could begin...........

The Photo is a depiction of Norham Castle in medieval times.

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

2nd January 1264: Marriage and Murder in Mediaeval Menteith

(Priory of Inchmahome, founded on one of the islands of Lake of Menteith in the thirteenth century)

On 2nd January 1264, Pope Urban IV despatched a letter to the bishops of St Andrews and Aberdeen, and the Abbot of Dunfermline, commanding them to enquire into a succession dispute in the earldom of Menteith. Situated in the heart of Scotland, this earldom stretched from the graceful mountains and glens of the Trossachs, to the boggy carseland west of Stirling and the low-lying Vale of Menteith between Callander and Dunblane. The earls and countesses of Menteith were members of the highest rank of the nobility, ruling the area from strongholds such as Doune Castle, Inch Talla, and Kilbryde. Perhaps the best-known relic of the mediaeval earldom is the beautiful, ruined Priory of Inchmahome, which was established on an island in Lake of Menteith by Earl Walter Comyn in 1238. Walter Comyn was a powerful, if controversial, figure during the reigns of Kings Alexander II and Alexander III. He controlled the earldom for several decades after his marriage to its Countess, Isabella of Menteith, but following Walter’s death in 1258 his widow was beset on all sides by powerful enemies. These enemies even went so far as to capture Isabella and accuse her of poisoning her husband. The story of this unfortunate countess offers a rare glimpse into the position of great heiresses in High Mediaeval Scotland, revealing the darker side of thirteenth century politics.

Alexander II and Alexander III are generally remembered as powerful monarchs who oversaw the expansion and consolidation of the Scottish realm. During their reigns, dynastic rivals like the MacWilliams were crushed, regions such as Galloway and the Western Isles formally acknowledged Scottish overlordship, and the Scottish Crown held its own in diplomacy and disputes with neighbouring rulers in Norway and England. Both kings furthered their aims by promoting powerful nobles in strategic areas, but it was also vital to harness the ambition and aggression of these men productively. In the absence of an adult monarch, unchecked magnate rivalry risked destabilising the realm, as in the years between 1249 and 1262, when Alexander III was underage.

(A fifteenth century depiction of the coronation of Alexander III. Source: Wikimedia Commons)

Walter Comyn offers a typical picture of the ambitious Scottish magnate. Ultimately loyal to the Crown, his family loyalties and personal aims nonetheless made him a divisive figure. A member of the powerful Comyn kindred, he had received the lordship of Badenoch in the Central Highlands by 1229, probably because of his family’s opposition to the MacWilliams. In early 1231, he was granted the hand of a rich heiress, Isabella of Menteith. In the end, there would be no Comyn dynasty in Menteith: Walter and Isabella had a son named Henry, mentioned in a charter c.1250, but he likely predeceased his father. Nevertheless, Walter Comyn carved out a career at the centre of Scottish politics and besides witnessing many royal charters, he acted as the king’s lieutenant in Galloway in 1235 and became embroiled in the scandalous Bisset affair of 1242.

When Alexander II died in 1249, Walter and the other Comyns sought power during the minority of the boy king Alexander III. They were opposed by the similarly ambitious Alan Durward and in time Henry III of England, the attentive father of Alexander III’s wife Margaret, was also dragged into the squabble as both sides solicited his support in order to undermine their opponents. Possession of the young king’s person offered a swift route to power, and, although nobody challenged Alexander III’s right to the throne, some took drastic measures to seize control of government. Walter Comyn and his allies managed this twice, the second time by kidnapping the young king at Kinross in 1257. They were later forced to make concessions to enemies like Durward but, with Henry III increasingly distracted by the deteriorating political situation in England, the Comyns held onto power for the rest of the minority. However Walter only enjoyed his victory for a short while: by the end of 1258, the Earl of Menteith was dead.

Walter Comyn had dominated Scottish politics for a decade, and even if, as Michael Brown suggests, his death gave the political community some breathing space, this also left Menteith without a lord. As a widow, Countess Isabella theoretically gained more personal freedom, but mediaeval realpolitik was not always consistent with legal ideals. In thirteenth century Scotland, the increased wealth of widows made them vulnerable in new ways (not least to abduction) and, although primogeniture and the indivisibility of earldoms were promoted, in reality these ideals were often subordinated to the Crown’s need to reward its supporters. Isabella of Menteith was soon to find that her position had become very precarious.

At first, things went well. Although one source claims that many noblemen sought her hand, Isabella made her own choice, marrying an English knight named John Russell. Sir John’s background is obscure but, despite assertions that he was low born, he had connections at the English court. Isabella and John obtained royal consent for their marriage c.1260, and the happy couple also took crusading vows soon afterwards.

But whatever his wife thought, in the eyes of the Scottish nobility John Russell cut a much less impressive figure than Walter Comyn. The couple had not been married long before a powerful coterie of nobles descended on Menteith like hoodie-crows. Pope Urban’s list of persecutors includes the earls of Buchan, Fife, Mar, and Strathearn, Alan Durward, Hugh of Abernethy, Reginald le Cheyne, Hugh de Berkeley, David de Graham, and many others. But the ringleader was John ‘the Red’ Comyn, the nephew of Isabella of Menteith’s deceased husband Walter, who had already succeeded to the lordship of Badenoch. Even though Menteith belonged to Isabella in her own right, Comyn coveted his late uncle’s title there. Supported by the other lords, he captured and imprisoned the countess and John Russell, and justified this bold assault by claiming that the newlyweds had conspired together to poison Earl Walter. It is unclear what proof, if any, John Comyn supplied to back up his claim, but the couple were unable to disprove it. They were forced to surrender all claims to Isabella’s dowry, as well as many of her own lands and rents. A surviving charter shows that Hugh de Abernethy was granted property around Aberfoyle about 1260, but it seems that the lion’s share of the spoils went to the Red Comyn, who secured for himself and his heirs the promise of the earldom of Menteith itself.

Isabella and her husband were only released when they promised to pass into exile until they could clear their names before seven peers of the realm. John Russell’s brother Robert was delivered to Comyn as security for their full resignation of the earldom. Having ‘incurred heavy losses and expenses’, which certainly stymied their crusading plans, they fled.

In a letter of 1264, Pope Urban IV described the couple as ‘undefended by the authority of the king, while as yet a minor’. However, though Alexander III was technically underage in 1260, he was now nineteen and could not be ignored entirely. Michael Brown suggests that Isabella and her husband may have been seized when the king was visiting England, and that John Comyn’s unsanctioned bid for the earldom of Menteith may explain why Alexander cut short his stay in November 1260 and hastily returned north, leaving his pregnant queen with her parents at Windsor. Certainly, Comyn was forced to relinquish the earldom before 17th April 1261. But instead of restoring Menteith to its exiled countess, Alexander settled the earldom on another rising star: Walter ‘Bailloch’ Stewart, whose wife Mary had a claim to Menteith.

Mary of Menteith is often described as Isabella’s younger sister, although contemporary sources never say so and some historians argue that they were cousins. Either way, Alexander’s decision to uphold her claim was probably as much influenced by her husband’s identity as her alleged birth right. Like Walter Comyn, Walter Bailloch (‘freckled’), belonged to an influential family as the brother of Alexander, Steward of Scotland. From their origins in the royal household, the Stewarts became major regional magnates, assisting royal expansion in the west. The promising son of a powerful family, Walter Bailloch was sheriff of Ayr by 1264 and likely fought in the Battle of Largs in 1263. In 1260 Alexander III had the opportunity to secure Walter’s loyalty as the royal minority drew to a close. Conversely John Comyn of Badenoch found himself out of favour and was removed as justiciar of Galloway following the Menteith incident. The king would not alienate the Comyns permanently, but for now, the stars of Walter Bailloch and Mary of Menteith were in the ascendant.

(Loch Lubnaig, in the Trossachs, another former possession of the earls of Menteith)

Isabella of Menteith and John Russell had not been idle in the meantime. Travelling to John’s home country of England, they probably appealed to Henry III. In September 1261, the English king inspected documents relating to a previous dispute over the earldom of Menteith. On that occasion, two brothers, both named Maurice, had their differences settled before the future Alexander II at Edinburgh in 1213. The elder Maurice, who held the title Earl of Menteith and was presumed illegitimate by later writers (though this is never stated), resigned the earldom, which was regranted to Maurice junior. In return the elder Maurice received some towns and lands to be held for his lifetime only, and the younger Maurice promised to provide for the marriage of his older brother’s daughters.

It is probable that Isabella was the daughter of the younger Maurice, and that she produced these charters as proof of her right to the earldom. Perhaps Mary was her younger sister, but it seems likelier that Isabella would have wanted to prove the younger Maurice’s right if Mary was a descendant of the elder brother, and therefore her cousin. However despite Henry III’s formal recognition of the settlement, he did not provide Isabella with any real assistance: for whatever reason, the English king was either unable or unwilling to press his son-in-law the King of Scots on this matter. Isabella then turned instead to the spiritual leader of western Europe- Pope Urban IV.

(A depiction of the coronation of Henry III of England, though in fact the English king was only a child when he was crowned. Source: Wikimedia Commons)

A long epistle which the pope sent to several Scottish prelates in January 1264 has survived, revealing much about the case. Thus we learn that Urban was initially moved by Isabella and her husband’s predicament, perhaps especially so since they had taken the cross. Accordingly, he had appointed his chaplain Pontius Nicholas to enquire further and discreetly arrange the couple’s restoration. Pontius was to journey to Menteith, ‘if he could safely do so, otherwise to pass personally to parts adjacent to the said kingdom, and to summon those who should be summoned’. But Pontius’ mission only hindered Isabella’s suit. According to Gesta Annalia I, the papal chaplain got no closer to Scotland than York. From there he summoned many Scottish churchmen and nobles to appear before him, and even the King of Scots himself. This merely antagonised Alexander III and his subjects. Although Alexander maintained good relations with England and the papacy throughout his reign, he had a strong sense of his own prerogative and did not appreciate being summoned to answer for his actions, especially not outwith his realm and least of all in York. Special daughter of the papacy or not, Scotland’s clergy and nobility supported their king and refused to compear. Faced with this intransigence, Pontius Nicholas placed the entire kingdom under interdict, at which point Alexander retaliated by writing directly to the chaplain’s boss, demanding Pontius’ dismissal from the case.

Urban IV swiftly backpedalled. In a conciliatory tone he claimed that Pontius was guilty of ‘exceeding the terms of our mandate’ and causing ‘grievous scandal’. To remedy the situation, and avoid endangering souls, the pope discharged his responsibility over the case to the bishops of St Andrews and Aberdeen, and the Abbot of Dunfermline. Thus the pope washed his hands of a troublesome case, the Scottish king’s nose could be put back in joint, and Isabella’s suit was transferred to men with great experience of Scottish affairs, who should have been capable of satisfactorily resolving the matter. However, there is no indication that Isabella was ever compensated for the loss of her inheritance, and when the dispute over Menteith was raised again ten years later, the countess was not even mentioned (probably she had since died). Possibly her suit was discreetly buried after it was transferred to the Scottish clerics, a solution which, however frustrating for the exiled countess, would have been convenient for the great men whose responsibility it was to ensure justice was done.

(Doune Castle- the earliest parts of this famous stronghold probably date to the days of the thirteenth century earls of Menteith, although much of the work visible today dates from the late fourteenth and early fifteenth centuries)

The Comyns could not be dismissed so easily. Never resigned to losing Menteith, John Comyn of Badenoch claimed the earldom again c.1273, on behalf of his son William Comyn of Kirkintilloch. William had since married Isabella Russell, daughter of Isabella of Menteith by her second husband.* The 1273 suit was unsuccessful but William Comyn and Isabella Russell did not lose hope, and in 1282, William asked Edward I of England to intercede for them with the king of Scots. In 1285, with William’s father John Comyn long dead, Alexander III finally offered a compromise. Walter Bailloch, whose wife Mary may have died, was to keep half the earldom and he and his heirs would bear the title earl of Menteith. William Comyn and Isabella Russell received the other half in free barony, and this eventually passed to the offspring of Isabella’s second marriage to Sir Edward Hastings. Perhaps this could be seen as a posthumous victory for Isabella Russell’s late parents, but their descendants would never regain the whole earldom (except, controversially, when the younger Isabella’s two sons were each granted half after Edward I forfeited the current earl for supporting Robert Bruce).

Conversely, Walter Bailloch’s descendants remained at the forefront of Scottish politics. He and his wife Mary accompanied Alexander III’s daughter to Norway in 1281, and Walter was later a signatory to both the Turnberry Band and the Maid of Norway’s marriage negotiations. He also acted as a commissioner for Robert Bruce (grandfather to the future king) during the Great Cause. He had at least three children by Mary of Menteith and their sons took the surname Menteith rather than Stewart. The descendants of the eldest son, Alexander, held the earldom of Menteith until at least 1425. The younger son, John, became infamous as the much-maligned ‘Fause Menteith’ who betrayed William Wallace, although he later rose high in the service of King Robert I. Walter Bailloch himself died c.1294-5, and was buried next to his wife at the Priory of Inchmahome on Lake of Menteith, which Walter Comyn had founded over fifty years previously. The effigies of Walter Bailloch and Mary of Menteith can still be seen in the chapter house of the ruined priory: the worn faces are turned towards each other and each figure stretches out an arm to embrace their spouse in a lasting symbol of marital affection.

(The effigies of Walter Bailloch and Mary of Menteith at Inchmahome Priory, which was founded by Walter Comyn in 1238 and was perhaps intended as a burial site for himself and his wife Isabella of Menteith. Source: Wikimedia Commons).

The dispute over Menteith saw a prominent noblewoman publicly accused of murder and exiled, and even sparked an international incident when Scotland was placed under interdict. For all this, neither Isabella of Menteith nor John Comyn of Badenoch triumphed in the long term. Even Walter Bailloch eventually had to accept the loss of half the earldom after holding it for over twenty years. In the end the only real winner seems to have been the king. Although at first sight the persecution of Isabella and her husband looks like a classic example of overmighty magnates taking advantage of a breakdown in law and order during a royal minority, Alexander III was not a child and his rebuke of John Comyn did not result in any backlash against the Crown. Most of the Scottish nobility fell back in line once the king came of age, but the king in turn had to ensure that he was able to reward key supporters if he wanted to expand the realm he had inherited. Although it was important to both Alexander III and his father that primogeniture and were accepted by their subjects as the norm, in practice both kings found that they had to bend their own rules to ensure that the system worked to their own advantage. The thirteenth century is often seen an age of legal development and state-building, but these things sometimes came into conflict with each other, and even the most successful kings had to work within a messy system and consider the competing loyalties and customs of their subjects.

Selected Bibliography:

- “Vetera Monumenta Hibernorum et Scotorum”, Augustinus Theiner (a printed version of Urban IV’s original Latin epistle may be found here)

- “John of Fordun’s Chronicle of the Scottish Nation”, vol. 2, ed. W.F. Skene (this is an English translation of the chronicle of John of Fordun, made when Gesta Annalia I was still believed to be his work. It provides an independent thirteenth or fourteenth century Scottish account of the Menteith case

- “The Red Book of Menteith”, volumes 1+2, ed. Sir William Fraser

- “Calendar of Documents Relating to Scotland, Preserved Among the Public Records of England”, volumes 1, 2, 3 & 5, ed. Joseph Bain

- “The Political Role of Walter Comyn, earl of Menteith, during the Minority of Alexander III of Scotland”, A. Young, in the Scottish Historical Review, vol.57 no.164 part 2 (1978).

- “Scotland, England and France After the Loss of Normandy, 1204-1296″, M.A. Pollock

- “The Wars of Scotland, 1214-1371″, Michael Brown

As ever if anyone has a question about a specific detail or source, please let me know! I have a lot of notes for this post, so hopefully I should be able to help!

#Scottish history#Scotland#British history#thirteenth century#women in history#Menteith#earldom of Menteith#Isabella Countess of Menteith#John Russell#John Comyn I of Badenoch#Alexander III#Henry III#Pope Urban IV#Walter Bailloch#the Stewarts#House of Dunkeld#House of Canmore#Mary of Menteith#inchmahome priory

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Q: When did the English start being Imperialist assholes? A: 14th Century

1300 - English invasion of Scotland, undertaken by King Edward I of England, to continue to attempt the conquest from the 1298 invasion and in reaction to the Scots recapture of Stirling Castle in 1299.

1301 - English invasion of Scotland, undertaken by King Edward I of England, aiming to conquer Scotland in a two-pronged attack along the eastern and western coasts.

1303 - English invasion of Scotland, undertaken by King Edward I of England after the failure of the 1301 invasion, another two-pronged attack along the eastern and western coasts to conquer Scotland.

1304 - English invasion of Scotland, undertaken by King Edward I of England who remained at war there for two years with battles across the entire land.

1306 - English invasion of Scotland, undertaken by an English army under the command of Aymer de Valence, Earl of Pembroke in retaliation of the murder of John Comyn, Lord of Badenoch and the crowning of King Robert I of Scotland; remaining in Scotland for the summer and autumn.

1307 - Proposed English invasion of Scotland, undertaken by King Edward I that, however, did not proceed after Edward I died while on his way north.

1310 - English invasion of Scotland, undertaken by King Edward II of England where he remained refurbishing English-held castles until midsummer 1311.

1314 - English invasion of Scotland which ended in English defeat at the Battle of Bannockburn.

1319 - English invasion of Scotland, undertaken by King Edward II of England who laid siege to Berwick but withdrew in response to a Scottish incursion into England.

1322 - English invasion of Scotland that turned back in response to Scottish incursion into England.

1333 - English invasion of Scotland, undertaken by King Edward III of England as part of the Second War of Scottish Independence.

1338 - English invasion of Scotland under William Montagu, 1st Earl of Salisbury.

1356 - English invasion of Scotland, undertaken by King Edward III of England and known as Burnt Candlemas.

1385 - English invasion of Scotland, undertaken by King Richard II of England.

#scotland#england#imperialism#war#scottish history#english history#14th century#found on wiki#edwards#kings

43 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Jacob Jacobsz de Wet II - Robert the Bruce, King of Scotland (1274-1329) - 1684-6

Robert I (11 July 1274 – 7 June 1329), popularly known as Robert the Bruce (Medieval Gaelic: Roibert a Briuis; Modern Scottish Gaelic: Raibeart Brus; Norman French: Robert de Brus or Robert de Bruys; Early Scots: Robert Brus; Latin: Robertus Brussius), was King of Scots from 1306 to his death in 1329. Robert was one of the most famous warriors of his generation and eventually led Scotland during the First War of Scottish Independence against England. He fought successfully during his reign to regain Scotland's place as an independent country and is now revered in Scotland as a national hero.

His paternal fourth great-grandfather was King David I. Robert's grandfather, Robert de Brus, 5th Lord of Annandale, was one of the claimants to the Scottish throne during the "Great Cause". As Earl of Carrick, Robert the Bruce supported his family's claim to the Scottish throne and took part in William Wallace's revolt against Edward I of England. Appointed in 1298 as a Guardian of Scotland alongside his chief rival for the throne, John Comyn of Badenoch, and William Lamberton, Bishop of St Andrews, Robert resigned in 1300 because of his quarrels with Comyn and the apparently imminent restoration of John Balliol to the Scottish throne. After submitting to Edward I in 1302 and returning to "the king's peace," Robert inherited his family's claim to the Scottish throne upon his father's death.

Bruce's involvement in John Comyn's murder in February 1306 led to him being excommunicated by Pope Clement V (although he received absolution from Robert Wishart, Bishop of Glasgow). Bruce moved quickly to seize the throne, and was crowned king of Scots on 25 March 1306. Edward I's forces defeated Robert in the battle of Methven, forcing him to flee into hiding before re-emerging in 1307 to defeat an English army at Loudoun Hill and wage a highly successful guerrilla war against the English. Bruce defeated his othe opponents, destroying their strongholds and devastating their lands, and in 1309 held his first parliament at . A series of military victories between 1310 and 1314 won him control of much of Scotland, and at the Battle of Bannockburn in 1314, Robert defeated a much larger English army under Edward II of England, confirming the re-establishment of an independent Scottish kingdom. The battle marked a significant turning point, with Robert's armies now free to launch devastating raids throughout northern England, while also extending his war against the English to Ireland by sending an army to invade there and by appealing to the Irish to rise against Edward II's rule.

Despite Bannockburn and the capture of the final English stronghold at Berwick in 1318, Edward II refused to renounce his claim to the overlordship of Scotland. In 1320, the Scottish nobility submitted the Declaration of Arbroath to Pope John XXII, declaring Robert as their rightful monarch and asserting Scotland's status as an independent kingdom. In 1324, the Pope recognised Robert I as king of an independent Scotland, and in 1326, the Franco-Scottish alliance was renewed in the Treaty of Corbeil. In 1327, the English deposed Edward II in favour of his son, Edward III, and peace was concluded between Scotland and England with the Treaty of Edinburgh–Northampton in 1328, by which Edward III renounced all claims to sovereignty over Scotland.

Robert died in June 1329. His body is buried in Dunfermline Abbey, while his heart was interred in Melrose Abbey and his internal organs embalmed and placed in St Serf's Chapel, Dumbarton, site of the medieval Cardross Parish church.

Jacob Jacobsz de Wet II (1641, Haarlem – 1697, Amsterdam), also known as James de Witt, was a Dutch Golden Age painter known for a series of 110 portraits of Scottish monarchs, many of them mythical, produced for the Palace of Holyroodhouse, Edinburgh during the reign of Charles II.

20 notes

·

View notes

Video

Statue: King Robert the Bruce - Stirling Castle by FotoFling Scotland

Via Flickr:

Robert I (11 July 1274 – 7 June 1329), popularly known as Robert the Bruce was King of Scots from 1306 until his death in 1329. Robert was one of the most famous warriors of his generation, and eventually led Scotland during the First War of Scottish Independence against England. He fought successfully during his reign to regain Scotland's place as an independent country and is today revered in Scotland as a national hero. Descended from the Anglo-Norman and Gaelic nobilities, his paternal fourth-great grandfather was King David I. Robert's grandfather, Robert de Brus, 5th Lord of Annandale, was one of the claimants to the Scottish throne during the "Great Cause". As Earl of Carrick, Robert the Bruce supported his family's claim to the Scottish throne and took part in William Wallace's revolt against Edward I of England. Appointed in 1298 as a Guardian of Scotland alongside his chief rival for the throne, John Comyn, Lord of Badenoch, and William Lamberton, Bishop of St Andrews, Robert later resigned in 1300 due to his quarrels with Comyn and the apparently imminent restoration of King John Balliol. After submitting to Edward I in 1302 and returning to "the king's peace", Robert inherited his family's claim to the Scottish throne upon his father's death. In February 1306, Robert the Bruce killed Comyn following an argument, and was excommunicated by the Pope (although he received absolution from Robert Wishart, Bishop of Glasgow). Bruce moved quickly to seize the throne and was crowned king of Scots on 25 March 1306. Edward I's forces defeated Robert in battle, forcing him to flee into hiding in the Hebrides and Ireland before returning in 1307 to defeat an English army at Loudoun Hill and wage a highly successful guerrilla war against the English. Bruce defeated his other Scots enemies, destroying their strongholds and devastating their lands, and in 1309 held his first parliament. A series of military victories between 1310 and 1314 won him control of much of Scotland, and at the Battle of Bannockburn in 1314, Robert defeated a much larger English army under Edward II of England, confirming the re-establishment of an independent Scottish kingdom. The battle marked a significant turning point, with Robert's armies now free to launch devastating raids throughout northern England, while also extending his war against the English to Ireland by sending an army to invade there and by appealing to the Irish to rise against Edward II's rule. Despite Bannockburn and the capture of the final English stronghold at Berwick in 1318, Edward II refused to renounce his claim to the overlordship of Scotland. In 1320, the Scottish nobility submitted the Declaration of Arbroath to Pope John XXII, declaring Robert as their rightful monarch and asserting Scotland's status as an independent kingdom. In 1324, the Pope recognised Robert I as king of an independent Scotland, and in 1326, the Franco-Scottish alliance was renewed in the Treaty of Corbeil. In 1327, the English deposed Edward II in favour of his son, Edward III, and peace was concluded between Scotland and England with the Treaty of Edinburgh-Northampton, by which Edward III renounced all claims to sovereignty over Scotland. Robert I died in June 1329. His body is buried in Dunfermline Abbey, while his heart was interred in Melrose Abbey. [Wikipedia]

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Thinking about it, Duns Scotus took the habit at the Dumfries Greyfriars, which just so happens to be the place where, a couple of decades later, Robert Bruce stabbed Comyn of Badenoch in 1306

Duns Scotus is thought to have lived until 1308, and if he had any kind of contacts with his old pals back in Scotland, they might have witnessed the murder, so um John I should like to hear your thoughts on this please

#If you or any other Franciscans witnessed this crime please call me#TBH though he was chilling in Oxford in about 1300 which must also have been interesting given that this was the era of Baldred Bisset#So like our John looked at Scotland c.1291 and went 'Hmmm nope'#Which is fair

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

I'm glad to hear it! 😍 I was wondering if you could help me answer a question: do you know where John III 'the red' Comyn lived? I've managed to find a couple of castles belonging to his family, but I was thinking of him specifically?

Consulting my big ass book of Gaelic History here and it says that he lived in Badenoch/Bàideanach near the Monadhliath Mountains. Never much did like him. When Robert the Bruce killed him I was just like...

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Book: Highland Beast

By Amy Jarecki

Series: The King’s Outlaws, Book #3

Release Date: June 29, 2021

Publisher: Oliver Heber Books

Overall Rating: 5/5 Stars/Saltire Flags

Scottish Highlands, 1308

The Lord of Lorn, grand niece and clan’s healer RhonaMacDougall is broken hearted her Great Uncle Alexander has to escape. Especially since he is elderly and not the hail and healthy leader he once was. He definitely should not be traipsing around the country in or out the country, although he hasn’t shared where exactly he was going. This was to keep Rhona safe and she was also a very bad liar, however if he didn’t escape the clutches of King Robert the Bruce and his men he would be sent to the gallows and most likely executed.

The MacDougall clan had sided with the English thinking their cousin Lord John Comyn III (The Red) of Badenoch whose grandsire John Balliol had been King 1292-1296 would be the next Scottish King. As he had the royal lineage except that cousin is in a cold grave stabbed to death by Robert the Bruce himself, before the altar at the church of the Greyfriars at Dumfries. Of course The MacDougall’s do not realize how Comyn had double crossed Robert and tried to murder him as he was only defending himself! The MacDougall’s have been enemies of the Scottish King and his knights, when all they want is peace and serenity.

What is even worse, Sir Arthur Campbell had lead the attack at Dunstaffnage and was honored the castle, surrounding land and constable and is the man now in charge of Rhona’s people and taking her Gran Uncle’s place. This is the man she previously loved, who once deserted and shattered her heart seven years ago! A former love who once owned her heart! Rhona became a healer after her husband of an arranged marriage was killed in a hunting accident. She herself had a left shoe with a platform of two inches to equalize her shorter leg. She feels this former love is now her enemy and has decided to do a few harmless tricks to put Arthur and Robert the Bruce’s men in their place.

Arthur was thrilled to receive this gift from King Robert the Bruce, mainly because it is where his one true love, Rhona MacDougall resides. He never stopped loving Rhona MacDougall and was even happier that she is no longer married and a widow, so he is determined to win her heart again! Except she sends him mixed messages every time he gets close to her! On top of that someone had put vinegar in the wine, made sure Robert the Bruce’s men only got cold baths and released prisoners who had viscously attacked Arthur and his men. So Arthur is devastated when he finds out his one true love is the culprit and by law he should be burning her at the stake, hanging her or torturing her, but he can’t look weak either. So what choice does this man have to end the life of the woman who owns his heart? How does he punish the woman who betrayed him and made him look like a fool, but he also loves. Can he end her life or is there another solution where he can still hold his head high to the people of Dunstaffnage? Will Rhona and her clan ever side with their new King Robert the Bruce without committing treason?

Amy Jarecki writes her third book in “The

King’s Outlaws” series. This is a

wonderful riveting story that I just couldn’t put down! It’s a second chance romance which are always so much fun to read! Again, it centers around Robert the Bruce’s warriors and the women that claim their hearts. On top of that it was an enemy clan who had sided with the English King! Plus this couple had a past romance that ended abruptly due to miscommunication. I love that the heroine is handicapped, but she does not let that slow her down in the least! Yet the hero has to make the hardest decision of his life after finding out the treachery committed by the woman he loves. Yet he feels like a broken man and ultimately deceived by the woman that owns his heart. A book they will grip historical romance readers, holds on and never lets you go, laced with deception, heartache, forgiveness and love. Plus my favorite ingredients in a story weaved with true Scottish history and a beautiful fictional romance. A book readers definitely don’t want to miss. You can read this as a stand-alone book or in book series order.

The King’s Outlaws series by Amy Jarecki

Highland Warlord

Highland Raider

Highland Beast

Disclaimer: I received an advance reader’s copy from Oliver-Heber publishing. I voluntarily agreed to do an honest, fair review and blog through Booksprout and Netgalley. All thoughts, ideas and words are my own.

“

0 notes

Text

Day 5 - The Highlands

Todd & James: Welcome to the Highlands! Today was a travel day as we headed north to the island of Skye. The day consisted of multiple stops along the way to capture the essence and beauty. The highlight of the day was our stop in Glencoe. Like most of our time here in Scotland, we had beautiful weather. Take notice at the awe-inspiring photos included with today’s entry.

At the town of Glencoe we stopped at their visitor’s center. I found it amusing to see on the wall it was inscribed: “There are two seasons in Scotland: June and winter.” This is similar to Minnesota as we often say “There are two seasons in Minnesota: winter and road construction.

After lunch, we drove into a park called Glencoe Lochan which had a few hiking trails. We took a quick hike and captured some wonderful photographs. (As you’ll see with this posting)

We drove about an hour further north and stopped near Fort William at the ruins of Inverlochy Castle. Mainly the outer walls are what remain of this castle. Inverlochy was built in about 1280 by John Comyn, the lord of Badenoch. Set beside a river, this castle at one time had a moat around it. The moat has been since filled in.

At last, we arrived at our housing for the next few days. The name of the lodge is called Sligachan Lodge. There’s a large kitchen and living room area which is a nice place for us to all hang out.

The lodge is right off the highway and is surrounded by fields and a stream. Below is another hotel with a neighboring pub. We had dinner there tonight. It was very inviting with warm atmosphere! The place was packed as there is a campground across the street. It’s amazing to sit and listen to so many different languages being spoken. Travelers are here from around the world to see the beauty and hike the trails of the isle of Skye.

0 notes

Text

April 27th 1296 saw the Battle of Dunbar.

There has been two Battles at Dunbar, both equally disastrous for the Scots, this one was on Edward I’s campaign to put John Balliol in his place after he signed the first Auld Alliance.

It wasn’t all about the Alliance, Longshanks thought he could use Scotland as a recruiting ground and ordered King John to send men for him to use in his war with the French, many historians believe that we had connections with France before 1296 as allies, this though was the first time anything official was signed so it is 1296 that is defined as the beginning of our “partnership” no matter what, there were good strong ties with the Gallic country before and Scotland did not want to go to war with a nation that it considered a friend.

On 23rd April 1296, as a precursor to advancing on to Edinburgh, Edward sent John de Warenne, Earl of Surrey north to secure Dunbar Castle. Fully aware the defences were inadequate to repel such a significant force, the garrison sent a plea for help to King John Ballil, who was camped at Haddington, some 10 miles away. As Surrey arrived at Dunbar, immediately beginning siege-works against the castle, King John dispatched a force to fight the English. Under the command of John Comyn, Lord of Badenoch (Red Comyn), the mounted elements of the Scottish army advanced on the English position. Longshanks choice of De Warenne was also a ploy to perhaps sway the Scottish King from fighting, as John Balliol was married to Isabella De Warenne, so sending an army to fight his father in law might have played heavy on Balliol’s head, but send it he did.

The Scottish forces arrived on the morning of 27th April and formed up on Spottismuir - a ridge of high ground overlooking Dunbar. Undeterred by the formidable Scottish defensive position, Surrey left his infantry to maintain the siege at the castle but moved his mounted forces to engage the Scots. In order to assault the Scottish position, the English had to cross the Spott Burn. This seemingly disrupted their lines for Comyn, with his forces now on the slopes of Doon Hill, misinterpreted the manoeuvre as one of retreat. Hoping to capitalise on the disruption to the English lines, he ordered the Scots to charge.

The Scottish charge consisted of a disorganised descent down the hill, in other words, your typical “Highland Charge” By contrast the English, having now forded the Spott Burn, reformed and counter charged routing the Scots. Whilst fatalities seem to have been limited - records suggest only one Scottish Knight, Sir Patrick Graham, was killed - significant numbers of Scotland’s best warriors were captured including John Comyn, John de Strathbogie (Earl of Atholl), Alexander (Earl of Menteith), William (Earl of Ross) and perhaps as many as 100 Knights. A handful successfully escaped into the Ettrick forest.

With the arrival of Edward I and the main English army a day later, Dunbar Castle surrendered to the English.

In the weeks that followed most of central and southern Scotland came under Edward’s control with key castles - most notably Roxburgh and Stirling being handed over without a fight. John Balliol was forced to capitulate at Stracathro near Montrose on July 10th Edward humiliated him tearing the arms of Scotland from John’s surcoat, giving him the abiding name of “Toom Tabard” (empty coat).

Edward chose to keep the Scottish throne vacant. The Wars of Scottish Independence had seemingly ended but, just 10 months later, William Wallace would kill William de Heselrig, High Sheriff of Lanark and start an uprising that would later see Surrey humiliated at the Battle of Stirling Brig.

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

On July 11th 1274 Robert the Bruce was born in Turnberry Castle, Ayrshire.

Sorry for the lack of posts yesterday I was out the house all day, I am showing friends round Edinburgh today but will try and get a few posts scheduled, this first one is of course a "biggie"

I don't like repeating the same old story, especially on posts like this, The Bruce turns up so often in my posts that it isn't any wonder he is part of the Scottish Psyche. In 2006 Robert the Bruce came third in a poll of ‘most important Scots’, behind William Wallace and Robert Burns. Leaving aside what that says about the nation that produced, among others, David Hume and Adam Smith, Alexander Fleming and John Logie Baird, there can be no doubt that a king that ruled 700 years ago is still very much remembered by Scots today and, even more pertinently, that his life and achievements are deemed to be profoundly influential. It is hard to imagine Edward III or Henry V of England being similarly admired.

Not a lot is known about Robert's early life so unfortunately I do end up repeating parts of his life.....

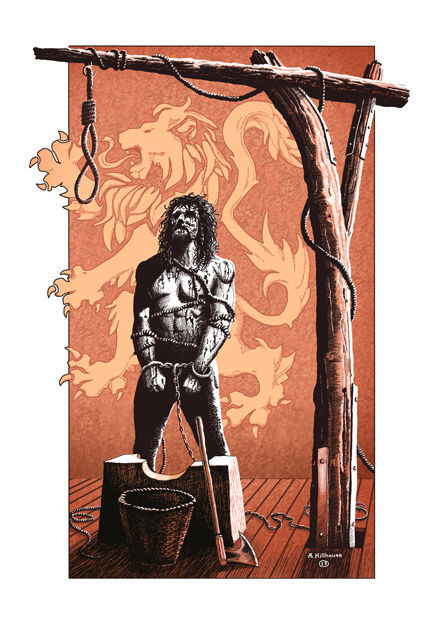

Looking into how he came to be our Monarch, Bruce’s grandfather had come off second best in 1292 to a rival claimant to the Scottish throne, John Balliol, who then reigned for four years until Edward I deprived him of his kingship in 1296. John Comyn of Badenoch, as Balliol’s nephew, had both an arguably better claim by blood and certainly by power, influence and track record than Robert Bruce, for his own ambitions, whether it be just to become King, or for the sake of ridding Scotland of Edwards army Robert had to ‘deal’ with his rival before seeking the throne for himself.

In this fracturing and fevered environment, the would-be king turned to Bishop Robert Wishart of Glasgow, a man who had shown himself consistently motivated since the 1280s by a desire to keep Scotland intact and independent (though he, like most Scots, had on occasions been forced to acknowledge King Edward as ruler of the northern kingdom). We do not know that Bishop Wishart made Bruce ‘swear upon the Holy Gospels and the tomb of St Kentigern’ to pursue the cause of Scottish independence with his life, if necessary. Equally, no chronicler at the time mentions the introduction of elements of sacramental kingship that the Scots had long sought from the pope but been denied thanks to English claims of overlordship on the day that Bruce finally did become king.

If you've seen the new film about The Bruce, you will know it is all about the man himself, rather than the historical facts in his reign, and that's why I liked it, I mean come on, we ALL know the story by now and if you don't what have you been doing for the past few years as you haven't been reading my posts!

Robert Bruce, was a man possessed with the ability to think laterally and effectively on almost every issue but saddled by his own hand with one of the most dodgy starts to a successful reign as any in history. Some say he learned to think this way after observing William Wallace, I also like to think this, but he had enough savvy himself to be his own man.

The problem with looking at Scotland in those heady days is that, unlike England, we hardly wrote anything down, Edward and his constant war waging meant he had to raise money for these attacks on Scotland and Wales beforehand, so the English always had that extra layer of bureaucracy, while historians can look at some of their records to glean information about Scotland, we mainly have to look at Chroniclers, like Lanecrost, or the likes of Blind Harry, the author of "he Actes and Deidis of the Illustre and Vallyeant Campioun Schir William Wallace" And John Barbour who wrote "The Brus". In the first case Harry wrote his epic over 150 years after William Wallace's murder. At least Barbour was living in an age where The Bruce was alive, albeit for nine of the years, but events and stories were still fresh and must have been repeated often about our Kings heroics in unting Scotland and vanquishing the English. But Barbour was never going to write anything negative about Bruce, it was Robert II, the first of the Stewart line, that asked Barbour to write the poem, it was always going to be a great propaganda exercise.

Okay let's go back a wee bit, there has been some debate about where Bruce was born, some mischief makers even suggest he was not born at Turnberry, after all we have no diminutive proof, but at Writtle in deepest Essex. The Bruce family owned swathes of land down south, and there is no doubt the young Robert would have spent time in the depths of the English royal courts, he was not uncouth Scottish brute, he grew up in a world of fluid identities, no doubt speaking a number of languages, and with easy access to both the overtly powerful and impressively formal English court as well as the highly personal and personable style of kingship still preferred in Scotland.

One of the things Robert the Bruce may very well have learned from the English and used most notably was the commandeering of noble seals to be attached to documents of state in order to present a veneer of unity to the outside world, this is most notable in the 1320 Declaration of Arbroath, it has been argued he took this inspiration from King Edwards, Ragman Rolls, Edward I’s large-scale demand for Scottish seals to acknowledge his right to rule Scotland in 1296.

After Bannockburn and the Declaration of Arbroath King Robert’s genius as a lawmaker and diplomat to rival his undoubted skill as a military leader has also been admired, he had a fine line to tread, while he had gained the upper hand against Edward II's army, many Scots fought against him that day, or at very least supported the English. Even after his death some of those families on the losing side that would come back to try and regain lands and titles from the second Bruce monarch, his son King David II.

The pics are King Robert's statue at Bannockburn and two reconstructions of how Turnbery may have looked, by my Twitter friend Andrew Spratt.

#scotland#scottish#king robert#robert the bruce#warrior king#outlaw king#the real braveheart#history

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

17th June 1390 saw Alexander Stewart, the Wolf of Badenoch, burn Elgin Cathedral.

I’ve posted about The Wolf of Badenoch and his torching of the Cathedral before, sometimes called the Celtic Attila, or the vilest man in Scottish history, but who was this man and how did he get his reputation?

The Brother of King Robert III, Alexander Stewart, Alisdair Mor mac an Righ,was a man of many names another was Big Alexander, the times in which he lived were barbarous, but even by their standards he stood out, and was feared over a considerable distance.

Throughout his life he was Lord of Badenoch around 1371, Earl of Buchanan and was also his brother’s royal deputy in the north of Scotland. This is where you might have to remember some of my other posts to piece things together, King Robert III was a weak King, before he became monarch he actually had more power and had basically ruled in favour of his father, at sometime he took a kick from a horse and this left him somewhat disabled, he was crowned King in 1390 but his younger brother brother Robert, Earl of Fife was running Scotland- hold on two Roberts!? I hear you say? Well King Robert took the name rather than his birth name, John, which was regarded as an unlucky name for a King, after John Balliol, Tomb of Tabard fame.

So to understand Alexander a we bit,, I think we have to rewind a bit to King David II, Uncle to Robert II, the two though were not the best of friends, in 1368 he and his sons were required by David’s parliament to take an oath that they would keep their undisciplined followers in check—later that year, Robert and Alexander were imprisoned in Loch Leven Castle possibly as a result of these oaths having been broken, I’m not sure how long they were held on the Island Castle but I am sure it must have affected Alexander more than his brother, when David died heirless three years later Robert II took the throne and Alex was formally made Lord of Badenoch on 30 March 1371, by the following year Alexander held crown authority from north Perthshire to the Pentland Firth, so controlled half of Scotland. In 1382 he was created Earl of Buchan, the first person to hold the title since John Comyn.

Alexander Stewart was a vicious, bloodthirsty and brutal character, he abused his power and maintained a rule of terror across much of the Highlands by imprisoning and murdering those who offended him. He was said to be huge in stature with a florid complexion and jet black beard, he accompanied his men on missions to rape and pillage within villages in the surrounding countryside, and was merciless in his actions. He was consequently censured by the King’s Council in 1388. His chief residence was Lochindorb Castle which is situated on an island in Lochindorb, north of Grantown-on-Spey, but he was also associated with Drumin Castle near Glenlivet and Ruthven Castle near Kingussie.

Alexander married the heiress Euphemia de Ross, Countess of Ross in July 1382. The marriage produced no children, for which he blamed on his wife. In 1389 Alexander sought the aid of Alexander Bur, Bishop of Mora to annul the marriage. The Bishop, however supported Euphemia, and ordered him to return to his wife, Alexander reacted by angrily expelling his wife to make way for his mistress, Mariota Athyn, who had already provided him with several children, the Bishop excommunicated Alexander, the monk who came to Lochindorb castle to inform him of his excommunication was thrown into the castle’s water pit vault.

Bishop Bur obtained the support Thomas Dunbar, Sheriff of Inverness and son of the Earl of Moray to provide his protection. In May 1390, Alexander rode to Moray with a large force and brutally sacked the town of Forres. He went on to destroy Pluscarden Abbey, from where he continued to Elgin, arriving on 17 June 1390, he burned much of the town and destroyed Elgin Cathedral, as well as the cathedral, the monastery of the Greyfriars, St Giles parish church and the Hospital of Maison Dieu were all engulfed in flames.

Alexander had to appear at the Church of the Friars Preacher, in Perth in the presence of his brothers, King Robert III and Robert Earl of Fife, and the council-general to plead for forgiveness. Robert III ordered his younger brother to do penance for his crimes and make financial reparations, he then pardoned him.

Some records state the The Wolf of Badenoch died in 1394, although others maintain is was in 1406, when it is believed that he played chess with the devil at Ruthven Castle. Legend has it he was visited by a tall man dressed in black and the pair played through the night, with a storm conjured when the visitor called “check” and “checkmate”. In the morning, the Wolf was found dead in the banqueting hall and his men too found lifeless outside the castle walls

There is a relatively new statue of Alexander Stewart in Elgin, and you have to raise an eyebrow as to why it was ever commissioned, I mean by all accounts the guy was a tyrant..........

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

May 30th 1291 saw claimants to the Scottish throne meet King Edward I of England at Norham on Tweed to resolve succession, this became known as The Great Cause.

Following a period of prosperity for the Scottish Kingdom, tragedy struck when Alexander III died and left no heir. The nobles of Scotland agreed to oversee the coronation of Alexander’s granddaughter Margaret, Maid of Norway, as well as selecting a regent to rule and a husband for her to marry.

In the meantime, in order for the kingdom to function properly, ‘Guardians of the Realm’ had to be appointed.

The men chosen were: the Bishops Fraser of St Andrews and Wishart of Glasgow, the barons John Comyn of Badenoch and James Steward, and the Earls of Buchan and Fife. It was agreed amongst the Guardians that the nobility of the realm would swear an oath of loyalty of the young queen, but in the meantime they would rule in the name of the Scottish crown.

Tragedy struck when Margaret died travelling from Norway to Scotland. This left the future of the Scottish Kingdom in jeopardy as without her, the Treaty of Birgham was meaningless.

Edward I was informed, by the Bishop of St. Andrews, that Robert Bruce and the Earls of Athol and Mar were scheming and that war was a distinct possibility. The bishop asked Edward for assistance in order to stop a civil war. Bishop Fraser clearly favoured Balliol, but Bruce and his followers appealed to Edward by writing the 'Appeal of the Seven Earls.’

At Norham, Edward showed his intentions of being made Overlord of Scotland, demanding that the Scots make him their feudal overlord before he would make any judgement on who would become the new King of Scots.

The Scots were worried because Edward had a large military presence with him. The Guardians replied stating that only a king could deal with such a demand which could only happen after Edward had selected one. Edward wrote to English monasteries asking them to search for legal evidence in their documents for English overlordship over Scotland. He also threatened to blockade Scottish ports with his navy and summoned men to form an army.

Fourteen claimants petitioned Edward for the throne of Scotland, but two emerged as having serious claims – John Balliol and Robert Bruce. To make sure that he became overlord of Scotland, Edward demanded that all the claimants accept this before he would pass judgement. This agreement is known as the 'Award of Norham’.

This was an important moment because the claimants acknowledged Edward’s overlordship; by giving him legal possession of the kingdom, Scotland was his to give freely away.

The original contenders for the crown are seen in the image below, the second pic are the ruins of Norham Castle.

#scotland#scottish#medieval history#england#english#King Edward I#Longshanks#The Hammer of the Scots#The Great Cause#john balliol

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

19th March 1286: “A Strong Wind Will Be Heard in Scotland”

(Image source: Wikimedia Commons)

On 19th March 1286, a body was discovered on a Fife beach, not far from the royal burgh of Kinghorn. The corpse was that of a 44-year-old man, and the cause of death was later diversely reported as either a broken neck or some other severe injury consistent with a fall from a horse at some point during the previous night. It is not known exactly when this body was found, nor do we know who discovered it. But we do know that the dead man was soon identified, with much dismay, as the King of Scots himself, Alexander III.

The late king had no surviving children, only a young widow who was not yet known to be pregnant, and an infant granddaughter in the kingdom of Norway. Despite this, Alexander III’s untimely death did not cause any immediate civil strife, although it did set in motion a chain of events which eventually led to the Scottish Wars of Independence. This conflict would forever alter the relationship between the kingdoms of Scotland and England, as well as the wider course of European history.

Although Alexander III was a moderately successful monarch, he had been unfortunate over the last ten years. His first wife, Margaret of England, had died in 1275 and Alexander initially showed no immediate interest in remarriage. At first the succession seemed secure: Margaret had left behind two sons and a daughter. However the death of the couple’s younger son David c.1281, may have prompted the king’s decision to arrange the marriages of his two surviving children over the next few years. In the summer of 1281, the twenty-year-old Princess Margaret set sail for Bergen, where she was to marry King Eirik II of Norway. Her brother Alexander, the eighteen-year-old heir to the throne, married the Count of Flanders’ daughter in November 1282. Neither marriage lasted long. The queen of Norway died in spring 1283, possibly during childbirth, while her younger brother succumbed to illness in January 1284. Within a few years, a series of unforeseen tragedies had destroyed Alexander III’s family and hopes, and the outlook for the kingdom seemed equally bleak...

All was not lost however. The king was in good health and believed he could count on the support of the realm’s leading men. Steps were swiftly taken to ensure their compliance with his plans for the succession. On 5th February 1284, a few weeks after Prince Alexander’s death, an impressive number of Scottish nobles* set their seals to an agreement at Scone. In the event of the king of Scotland’s death without any surviving legitimate children, they obliged themselves and their heirs to accept as monarch the heir at law. This was currently a baby named Margaret, the only surviving child of Alexander III’s daughter the queen of Norway.

(Drawing based on a seal belonging to Yolande of Dreux, Alexander III’s second queen. She later became Countess of Montfort and, by marriage, Duchess of Brittany. Source: Wikimedia Commons)

Although the bishops of Scotland were to censure anyone who broke this oath, the prospect of the crown being inherited by an infant girl on the other side of the North Sea was obviously not ideal. Her grandfather struck an optimistic note in a letter to his brother-in-law Edward I of England, writing that in spite of his recent “intolerable” trials, “the child of his dearest daughter” still lived and hoping that “much good may yet be in store”. But the king would not leave everything up to chance and in October 1285, at the age of 43, he married the French noblewoman Yolande of Dreux. As the year drew to a close, Alexander might have hoped that his misfortunes were behind him. He still had his kingdom and his health, and now, with a new queen, there was every chance that he could father another son.

In fact, the king had less than six months to live. The exact circumstances of Alexander’s death are shrouded in mystery, although most sources agree on the fundamental details. Only the Chronicle of Lanercost gives a detailed account, although much cannot be corroborated, and its author had a habit of providing moral explanations for historical events. He was convinced that the calamities which befell the Scottish royal house in the 1280s were punishment for Alexander III’s personal sins. The chronicler never explicitly names these sins, but he does hint at a conflict between the king and the monks of Durham (allowing Alexander’s death to be attributed to a vengeful St Cuthbert). The chronicler also included salacious stories of Alexander’s private life, claiming:

“he used never to forbear on account of season or storm, nor for perils of flood or rocky cliffs, but would visit, not too creditably, matrons and nuns, virgins and widows, by day or by night as the fancy seized him, sometimes in disguise, often accompanied by a single follower.”

Although this does seem to back up the king’s habit of making reckless journeys, alone and in bad weather, the chronicle’s biases are nonetheless fairly obvious. On the other hand, the man who probably compiled the chronicle up to the year 1297 does appear to have had many contacts in Scotland. These included the confessors of the late Queen Margaret and her son Prince Alexander, as well as the latter’s tutor, the clergy of Haddington and Berwick, and the earl of Dunbar. It is unclear how he acquired information about Alexander III’s death, but the chronicle’s narrative is at least plausible and correct in its essentials. Although some of the anecdotes are a little too detailed and didactic to be entirely truthful, the narrative provides some interesting insights into contemporary behaviour, such as the way medieval Scots felt entitled to address their kings. In the absence of alternative narratives, and without necessarily subscribing to the chronicler’s moral views, it is therefore perhaps worth following Lanercost to begin with, supplementing this with additional information where possible.

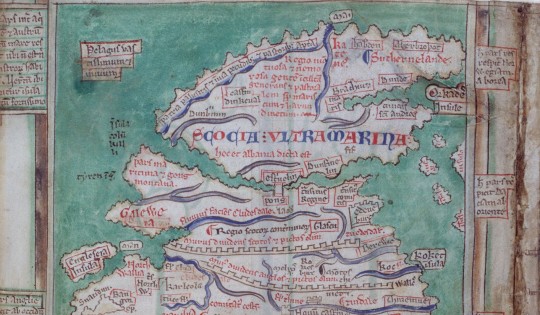

(The northern half of a map of Britain, drawn by the thirteenth century English chronicler Matthew Paris. Matthew Paris was based in the south of England and was not overly familiar with Scottish geography, but his depiction of Scotland as split over two islands and joined only at the bridge of Stirling, is nonetheless enlightening. The map is now in the public domain and has been made available by the British Libary (x))

On the evening of 18th March 1286, Alexander III is reported to have been in good spirits. This was in spite of the weather, which the author of the Chronicle of Lanercost described as being so foul, “that to me and most men, it seemed disagreeable to expose one’s face to the north wind, rain and snow”. The king of Scots was then dining at Edinburgh, attended by many of his nobles, who were preparing a response to the king of England’s ambassadors regarding the aged prisoner Thomas of Galloway. However when the court had finished dinner King Alexander was not at all anxious to retire early. Instead, not in the least deterred by the wind and rain lashing the windows, he announced his intention of spending the night with his new wife. Since Queen Yolande was then staying at Kinghorn in Fife, travelling there from Edinburgh would not only involve riding over twenty miles in the dark, but would also mean crossing the choppy waters of the Firth of Forth. Unsurprisingly, the king’s councillors tried to dissuade him. However Alexander was determined, and eventually he set off with only a few attendants, leaving his courtiers wringing their hands behind him.

The first part of the journey passed without incident and soon the king and his companions arrived at the Queen’s Ferry, by the shores of the Forth. This popular crossing point was named after Alexander’s famous ancestress St Margaret, who had established accommodation and transport for pilgrims there two hundred years earlier. But when the king himself sought passage, the ferryman pointed out that it would be very dangerous to attempt the crossing in such conditions. Alexander, undeterred, asked him if he was scared, to which the ferryman is said to have stoutly replied, “By no means, it would be a great honour to share the fate of your father’s son.” So the king and his attendants boarded the ferry and, notwithstanding the storm, the boat soon reached the shores of Fife in safety. As the king and his squires rode away from the ferry port, intending to complete the last eleven or so miles of their journey that night, they passed through the royal burgh of Inverkeithing. There, despite the evening gloom, the king’s voice was recognised by the manager of his saltpans, who was also one of the baillies of the town.** The burgess called out to the king and reprimanded him for his habit of riding abroad at night, inviting Alexander to stay with him until morning. But, laughing, Alexander dismissed his concerns and, asking only for some local serfs to act as guides, he rode off into the night.

(South Queensferry, as drawn by the eighteenth century artist John Clerk and made available for public use by the National Galleries of Scotland. Obviously the Queen’s Ferry changed a lot between the 1280s and the 1700s, but at least during this period the ferry was still the main mode of transportation across the Forth.)

By now darkness had set in and, despite the local knowledge of their guides, it was not long before every member of the king’s party became completely lost. Although they had become separated, the king’s squires eventually found the road again. However at some point they must have realised that they had a new problem: the king was nowhere to be found.

In the early fifteenth century, local tradition held that Alexander was at least heading in the right direction when he became separated from his companions. Although he too had lost sight of the main road, the king followed the shoreline, his horse carrying him swiftly over the sands towards Kinghorn. It was there, only a couple of miles from his destination, that the king’s luck finally ran out. Since there were no known witnesses to Alexander III’s death, it is unlikely that we will ever know for certain what happened that night. However most sources agree that the king’s horse probably stumbled and threw its rider. Alexander tumbled to the ground and snapped his neck and, at a stroke, the dynasty which had ruled Scotland for over two hundred years came to an end.

It is not known precisely how long the king’s body lay on the beach, alone under the moon while the waves crashed on the shore and confusion reigned among his squires and guides. However his corpse was discovered the next day and was swiftly conveyed to nearby Dunfermline. Ten days later, on 29th March 1286, the kingdom’s ruling elite gathered to see the last King Alexander buried near the high altar of the abbey kirk, in the company of his ancestors. Near the spot where the king’s body was allegedly found, a stone cross was later erected beside the road, which could still be seen by travellers over a hundred years later. The modern belief that Alexander III died when either he or his horse fell from a cliff*** (a tradition which is not supported by any mediaeval sources so far as I am aware) may stem from the position of this old cross, which possibly occupied the same spot as that of the Victorian Alexander III monument. This monument can now be seen at the side of the modern A921 road between Burntisland and Kinghorn, a permanent reminder of the role this seemingly nondescript location once played in the history of Scotland.

(The Alexander III monument near Kinghorn. Source: Wikimedia Commons- the photo was taken by Kim Traynor who has kindly made the image available for reuse under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license).

The impact of Alexander’s death on a small mediaeval kingdom like Scotland, conditioned to look to its monarch for leadership, must have been great. Even the Lanercost chronicler admitted that the general populace was observed “bewailing his sudden death as deeply as the desolation of the realm.” However it is important not to exaggerate the scale of the crisis. Popular views of Alexander III’s death are inescapably informed by the accounts of fourteenth and fifteenth century writers, who depicted it as the root of all of Scotland’s later ills.

Writing in the aftermath of a century dominated by war, plague, famine, and climate change, it is perhaps unsurprising that many late mediaeval chroniclers looked back on Alexander III’s reign as comparatively peaceful. As the author of the fourteenth century “Gesta Annalia II” explained, “How worthy of tears and how hurtful his death was to the kingdom of Scotland is plainly shown forth by the evils of after times.” Meanwhile, in his “Orygynale Cronykil of Scotland” completed c.1420, Andrew Wyntoun portrayed Alexander’s reign as a Golden Age of peace and justice (when, just as importantly, oats only cost fourpence a boll). He incorporated an old song into his chronicle, perhaps written in the years following the king’s accident, which neatly encapsulates later views of the event and its impact:

“Quhen Alysandyr oure Kyng wes dede

That Scotland led in luẅe and lé,

Away wes sons off ale and brede,

Off wyne and wax, off gamyn and glé:

Oure gold wes changyd in to lede.

Cryste borne in to Vyrgynyté,

Succoure Scotland and remede,

That stad [is in] perplexyté.”

Wyntoun’s younger contemporary Walter Bower, author of the “Scotichronicon”, also lamented Alexander’s premature death and even rolled out a legend about Scotland’s famous seer, Thomas the Rhymer, to reinforce his point. On 18th March 1286, he claimed, the earl of Dunbar “half-jesting” asked the Rhymer for the next day’s weather forecast. True Thomas answered gloomily:

“Alas for tomorrow, a day of calamity and misery! Because before the stroke of twelve a strong wind will be heard in Scotland, the like of which has not been known since long ago. Indeed its blast will dumbfound the nations and render senseless those who hear it, it will humble what is lofty and raze what is unbending to the ground.”

The next morning came and went without any gales, so the earl decided that Thomas had gone mad- until a messenger arrived at precisely midday with news of the king’s death. Although Bower may have been attempting to bolster Thomas of Erceldoune’s reputation as a prophet (in response to English propagandic use of Merlin’s prophecies), the anecdote reveals the significance he attached to Alexander III’s death. Similarly for John Barbour, author of the fourteenth century romance “The Bruce”, there was no doubt that the story of his hero’s story began, “Quhen Alexander the king was deid / That Scotland haid to steyr and leid.” Following this, Barbour skips ahead to the selection of John Balliol as king, dismissing the six years in between as a time when the country lay “desolate”. In this way later chroniclers created the impression of an Alexandrian ‘Golden Age’ and that Scotland almost immediately descended into chaos after his death. Though understandable, these late mediaeval interpretations have traditionally hampered analysis of Alexander’s reign and the events of the decade following his death, despite the best efforts of modern historians.

(The coronation of the young Alexander III at Scone, as depicted in a manuscript version of the fifteenth century “Scotichronicon”, compiled by the Abbot of Incholm, Walter Bower. Source: Wikimedia Commons)

In reality, while the king’s death was undoubtedly a deep blow, the Scottish political community rallied in the immediate aftermath. In April 1286, parliament assembled at Scone and promised to keep the peace on behalf of the rightful heir to the kingdom. Six ‘Guardians’ were to govern in the meantime- two bishops (William Fraser of St Andrews and Robert Wishart of Glasgow), two earls (Alexander Comyn, earl of Buchan and Duncan, earl of Fife), and two barons (John Comyn of Badenoch and James the Steward). Despite the oaths sworn to Margaret of Norway two years earlier, there may have been some doubt as to who the “rightful heir” actually was. Certain sources claim that Alexander III’s widow Yolande of Dreux was pregnant and the political community waited anxiously for several months before the queen gave birth in November 1286. However no male heir materialised**** and by the end of the year it seems to have been generally acknowledged that the three-year-old Maid of Norway was the rightful “Lady of Scotland”. She was destined never to set foot in Scotland, but, despite her age, gender, and absence from the realm, the country did not descend into complete anarchy in the four years when she was the accepted heir to the throne. Undoubtedly there were people who had reservations about her reign: the Bruces, for example, seem to have attempted a short-lived rebellion, though the situation was soon defused by the Guardians. By 1289 the cracks were perhaps beginning to show, with the death of the earl of Buchan and the murder of the earl of Fife removing two Guardians, who were not replaced. Nonetheless, the authority of the Guardians was recognised in the absence of an adult ruler and they generally attempted to govern competently in the four years between Alexander III’s accident and the Maid of Norway’s own death in 1290.

Having received news of this second tragedy, the Guardians again acted cautiously, deciding that rival claims for the kingship should be judged in an official court chaired by a respected and powerful arbitrator. Thus they appealed to Scotland’s formidable neighbour, Edward I of England. Despite later allegations of foul play, the English king’s eventual judgement in favour of John Balliol does appear to have been consistent with the law of primogeniture and due process. It would take years of steady deterioration before war finally broke out in 1296. By then Alexander III had been dead for a decade, and though the crisis may have indirectly grown out of his demise, it was not necessarily the immediate cause of Scotland’s late mediaeval woes. Nonetheless the events of that dark night in March 1286 would leave their mark on the popular imagination for centuries, shaping Scottish history down to the present day.

(An imprint of the Great Seal used by the Guardians of Scotland following Alexander III’s death. Reproduced in the “History of Scottish seals from the eleventh to the seventeenth century”, by Walter de Gray Birch, now out of copyright and available on internet archive)

Additional Notes:

*The assembled magnates included the earls of Buchan, Dunbar, Strathearn, Atholl, Lennox, Carrick, Mar, Angus, Menteith, Ross, Sutherland, and two other earls whose titles are illegible but who may have been Caithness and Fife. The barons included Robert de Brus the elder (father of the earl of Carrick and grandfather of the future Robert I), James Stewart, John Balliol (the future king), John Comyn of Badenoch, William de Soules, Enguerrand de Coucy (Alexander III’s maternal cousin), William Murray, Reginald le Cheyne, William de St Clair, Richard Siward, William of Brechin, Nicholas de Hay, Henry de Graham, Ingelram de Balliol, Alan the son of the earl, Reginald Cheyne the younger, (John?) de Lindsay, Simon Fraser, Alexander MacDougall of Argyll, Angus MacDonald, and Alan MacRuairi, among others.

** The historian G.W.S. Barrow identified this figure as Alexander the saucier the master of the royal sauce kitchen and one of the baillies of Inverkeithing.

*** There are some variations on this local tradition too- in 1794, the minister who wrote the entry for Kinghorn parish in the Old Statistical Account claimed that the ‘King’s Wood-end’ near the site of the current Alexander III monument was where the king liked to hunt and that he fell from his horse while on a hunting trip.

****The Guardians and other nobles may have assembled at Clackmannan for the birth. Several modern historians have accepted Walter Bower’s statement that the queen’s baby was stillborn, despite the Chronicle of Lanercost’s somewhat fantastic tale of a fake pregnancy, with Yolande being caught conspiring to smuggle an actor’s son into Stirling Castle.

Selected Bibliography:

- “The Chronicle of Lanercost”, as translated by Sir Herbert Maxwell