#Mikhail Gromov

Photo

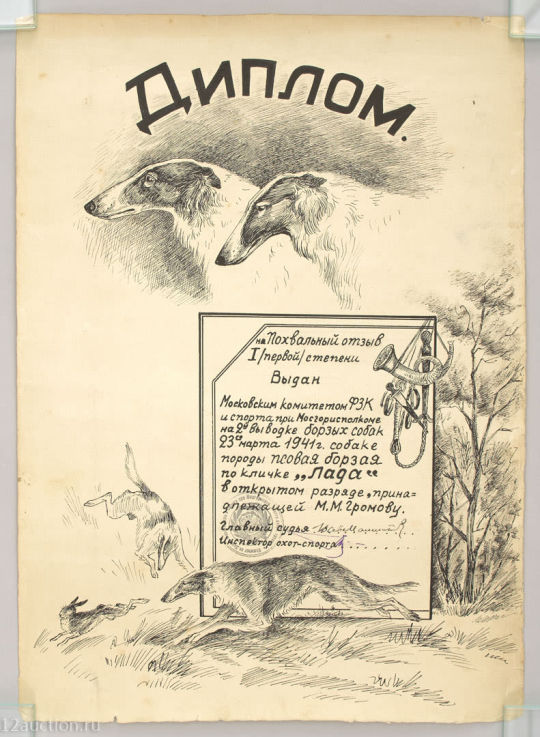

Pilot Gromov’s Borzoi Diploma for “Lada” (1941)

“Excerpt from the Judges’ Report” The Borzoi belonged to the pilot and military commander, General of Aviation of the Soviet Union Mikhail Mikhailovich Gromov (1899-1985)

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

TheIcebreaker (Russian: Ледокол, romanized: Ledokol) is a 2016 Russian disaster film directed by Nikolay Khomeriki.

youtube

The plot of the film is based in part on the real events that occurred in 1985 with the icebreaker Mikhail Somov [ru], which was trapped by Antarctic ice and spent 133 days in forced drift. The film premiered in Russia on October 20, 2016.

Toward the icebreaker "Mikhail Gromov" is moving a huge iceberg. Leaving from collision, the ship falls into the ice trap, and is forced to drift near the coast of Antarctica

0 notes

Text

Gromov's Theorem

Introduction

Gromov’s Theorem, proposed by mathematician Mikhail Gromov, is a fundamental result in the field of geometric group theory, which studies the algebraic properties of groups through their actions on geometric spaces. There are several theorems attributed to Gromov, but in geometric group theory, the most renowned one is perhaps the Gromov’s Theorem on groups of polynomial…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Encounter with a geometer: Marcel Berger on Mikhail Gromov

Marcel Berger on Mikhail Gromov, 2000

part 1, 2

"I believe the work of Gromov is very underrated. His books should be read until the pages fall off."

#h-principle#Marcel Berger#∞#Mikhail Gromov#geometry#mathematics#maths#math#jets#jet bundles#sheaves#sheaf theory#transversality#PDE's#differential equations#groups#group theory#analysis#zooming out#Samuel Eilenberg#Henri Cartan#negative curvature#curvature#hyperbolic#hyperbolic groups#Riemannian metric#Bernhard Riemann#Anthony Knapp#Riemannian geometry#inner product

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

Soviet test pilot Mikhail Mihaylovich Gromov spent his entire career testing Russian aircraft.

24 notes

·

View notes

Photo

(via What is the Russian party of war like? – Riddle Russia)

What is the Russian party of war like?

Andrey Pertsev on the key characteristics and goals of Russian public policy hawks

By

Andrey Pertsev

25 April 2022

Since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the Russian elite has been divided into three major groups manifesting different attitudes to the war. The largest of them is the ‘party of silence’, which represents the majority of top federal officials, heads of state corporations and state-related businesses. They are aware of the disastrous economic consequences of the invasion but are unable to stand up to President Vladimir Putin. A small ‘peace party’ is represented by the oligarchs who rose to prominence under Boris Yeltsin. Roman Abramovich, Oleg Deripaska, Mikhail Fridman and Vladimir Lisin go as far as to voice abstract calls for putting an end to the war. The ‘war party’, advocating an escalation of the conflict, is the loudest and most noticeable among them.

The war party is represented by the head of the Chechen Republic, Ramzan Kadyrov; the Deputy Chairman of the Security Council, Dmitry Medvedev; the Chairman of the State Duma, Vyacheslav Volodin; the Director General of Roscosmos, Dmitry Rogozin; the Secretary of the General Council of United Russia, Andrey Turchak; and the businessman Yevgeny Prigozhin. Alexey Gromov, the First Deputy Chief of Staff of the Presidential Executive Office, is also part of the flock. Gromov is not a public figure, but one can get an insight into his beliefs by looking at those close to him, such as RT’s editor-in-chief, Margarita Simonyan, and her subordinates, who take an ultra-hawkish stance. The war party has no hierarchy, and its members are either unrelated or at odds with each other, like Volodin and Turchak. Nevertheless, all of its representatives occupy similar positions in Russia’s pyramid of power, and they are pursuing the same goal hand in hand, with one addressee in mind — Putin. It is worth taking a closer look at this party also because its members clearly aspire to and can achieve career advancement, irrespective of whether Putin’s regime survives or not.

The active and aggressive

The war party proves its militancy in word and deed. Its most radical representatives in the public arena are Kadyrov and Turchak. Both politicians have visited Ukraine: Kadyrov met with the Chechen fighters taking part in the invasion, while Turchak put up Russian flags and victory banners in Ukrainian towns and villages. Neither has shied away from commenting on the war, and both have criticised presidential spokesman Dmitry Peskov for being too indecisive. Both Kadyrov and Turchak can be described as the vanguard of the war party, men who do not hesitate to attack members of the peace party or the party of silence, irrespective of their status or rank. In addition to Peskov, Vladimir Medinsky, an assistant to the President of the Russian Federation and a member of the Russian delegation in negotiations with Ukraine, has also suffered from the attacks of party militants.

The party’s media presence is ensured by Medvedev, Volodin and Rogozin. They regularly make public statements and, in a sense, set the tone for the Russian elite’s new style of self-presentation, which implies the transformation of its representatives into voluntary propagandists, jesters of the presidential court. The speeches by Rogozin, Volodin and Medvedev incite anti-Western sentiments in society. They serve as an additional reinforcement of Putin’s position. Therefore, he feels he can up the ante. Gromov, the Kremlin’s media gatekeeper, acts in a similar manner, but he doesn’t act on his own. Calls for an escalation of the war are voiced by TV hosts and participants as well as RT’s editor-in-chief, Simonyan.

Low prospects and high ambitions

Members of the war party have several traits in common that largely predetermine their behaviour. First and foremost, they have all reached the ceiling in their careers; they stopped climbing the ladder at some point and moved only horizontally. In the pre-war era, they could only slip to laudable but insignificant positions deprived of decision-making powers.

One of the members of the war party, Medvedev, the Deputy Chairman of the Security Council, exemplifies this pattern. In 2012, he was downgraded from the president’s chair to that of prime minister. In 2020, the second-highest official in the country at the time, Medvedev was dismissed and appointed to a hitherto unspecified position as Deputy Chairman of the Security Council. During the 2021 Duma campaign, Medvedev failed to move into the speaker’s chair, a move that was blocked by Putin himself. Now, the Deputy Chairman of the Security Council, who is sailing close to the wind by pre-war standards, may once again become a presidential favourite, the kind of hawk Putin might leave Russia to.

Kadyrov is trapped in the administrative hierarchy. On the one hand, he is afraid to leave his post as the leader of the Chechen Republic, since he is given free rein there. On the other hand, he would obviously not mind getting a decent job in one of the federal law enforcement agencies. He has been prevented real career advancement at the federal level by the siloviki, many of whom were directly involved in the wars in Chechnya. In Putin’s eyes, Kadyrov acquired a new status, that of a warrior who went to the front line and performed his role beautifully. Against this backdrop, the intentions of the siloviki may pale into insignificance.

Before the war, the career outlook for Turchak, the Secretary of the General Council of United Russia and First Deputy Speaker of the Federation Council, was dim. There were rumours that he might become the Governor of St Petersburg, and this seemed to be the pinnacle of his possible career. After the invasion, he equipped himself with aggressive rhetoric and went literally to the front line. Judging by his demeanour, Turchak clearly expects to be promoted, perhaps to the post of First Deputy Chief of Staff — or even Chief of Staff — of the Presidential Executive Office.

Before the war, the position of Chairman of the State Duma was seen as the peak of Volodin’s career. He felt comfortable in that chair; he adjusted the Duma apparatus to his needs and kept United Russia under control. Last spring, however, other candidates for the post of State Duma Chairman emerged, namely Alexey Gordeyev, a former Deputy Prime Minister, and Medvedev himself. Volodin kept his position due to a freeze on promotions, but his role was weakened significantly, and there was no outlook for him to move up the ladder before the war.

The Director General of Roscosmos, Rogozin, had also seen his career stall. He was Deputy Prime Minister before his appointment to the state corporation. Before that, he had been Russia’s permanent representative to NATO. Rogozin has been caught in perpetual horizontal motion, the wheel of life.

Other individuals, such as the businessman Prigozhin, also known as ‘Putin’s chef’, have also been drawn to the front line. Despite myths about his near omnipotence, Prigozhin’s influence is rather limited; he has a range of contracts with state institutions and state-owned corporations for cleaning services, and he provides food supplies to schools. Private military companies allegedly supervised by the businessman (Prigozhin himself denies this) have taken part in conflicts in Africa and Syria, and in 2014−2015 they fought in Donbas. In addition, Prigozhin controls a number of media outlets. He is quite influential but not so influential as businessmen from Putin’s immediate entourage. He is now going to Donbas in the hope of bolstering his gravitas.

Gromov, the First Deputy Chief of Staff of the Presidential Executive Office, media curator and former presidential Press Attaché has also reached his ceiling within the hierarchy.

Moreover, members of the war party seem to have nothing to lose in terms of property either. Their assets are not very impressive, although they are obviously very well off, as proved by the investigations conducted by the Anti-Corruption Foundation with regard to Medvedev, Rogozin and Volodin.

Another important trait manifested by the representatives of the war party is their ambition. All of the above-mentioned politicians and officials long to be promoted or reverse the downward trend. This key trait is closely related to the fact that they have nothing to lose. Unlike members of the party of silence, representatives of the war party are actively pursuing their interests and speaking out, since they have nothing to fear.

Finally, public exposure is also typical of them. Volodin and Rogozin were at one time quite successful public figures and politicians. And they made their careers largely due to publicity. Medvedev enjoyed public exposure during his presidency and premiership. Prigozhin was quite skilful in building his public image as a ‘grey cardinal’ and an ultra-patriot who never has to search for words. Turchak also strives to be a publicly recognised politician. This is what makes the voice of the war party sound so loud.

New figures gradually begin to join the war party: those who previously kept the silence mode. For example, last week the first deputy head of the Presidential Administration, the curator of the political bloc, Sergei Kiriyenko, spoke extensively about «Nazism» and visited the Donbass. Yet another member joins the war party and this is not the end of it.

Win-win game

The members of the war party are playing a win-win game. Regardless of the future political situation in Russia, they will either keep their positions (they would have kept their seats or been downgraded if it were not for the war) or be promoted.

The first and best-case scenario for the war party is the further escalation of hostilities, the snatching of some part of Ukraine by Russia or its proxies (i.e. the Donetsk People’s Republic or Luhansk People’s Republic), and the announcement of ‘victory’ and recognition of those who contributed to this ‘victory’. After the war, the system will inevitably be restructured, the staff promotion process will be restored, and the politicians and officials who have come to the (military or propaganda) forefront will be offered new opportunities. Putin is clearly in a belligerent mood, and most probably those who resonate with his sentiments will win the prize.

In the case of the second scenario, namely a ceasefire and the withdrawal of Russian troops to de facto pre-war positions, members of the war party will not lose their chance of being promoted. Putin’s views will not change anyway — i.e. Ukraine is anti-Russia, and NATO is threatening and encircling us. Politicians who publicly adhere to these views will still enjoy the president’s favours. In addition, warmongering characters have always made Putin look like the ‘only European’ in the Russian government and in Russia as a whole. The head of state and his entourage used to always distance themselves from the radical statements of individual Russian officials and MPs. Creating a militant backdrop against which Putin would look like a peacemaker could also be rewarding.

The third scenario, which so far does not look very likely, involves Putin stepping down as president, peace being made with Ukraine and the Russian regime gradually being democratised. As strange as it may sound, this scenario also opens a window of opportunity for members of the war party in the event that members of the top leadership are not put on trial and lustrated (if they are held accountable, the party of silence will not be spared either). The opposition-minded part of society is inclined to forgive other people’s sins. Some opinion writers, political analysts and journalists have managed to change camps over the years, but their opinions still matter for the audience disloyal to the authorities. Russians vote for former United Russia politicians if they publicly break with the ruling party and run as opposition candidates (for example, the former United Russia politician Yevgeny Urlashov won the 2012 mayoral election in Yaroslavl). It is likely that the members of the war party who publicly renounce their own words (provided that society still remembers those words) will be forgiven and granted an opportunity to continue their political careers. Since the war party consists of experienced politicians, most of them stand a good chance of staying in politics. It is easy to imagine Volodin leading a moderate-conservative party, Rogozin leading a right-wing nationalist project, and Medvedev recalling his former liberal aspirations. The issue of Western sanctions could also be resolved. Members of both the party of silence and the peace party are on sanctions lists. If these restrictions are lifted, they will most likely be lifted for all those who were not directly involved in the war and in giving orders. If sanctions are not lifted, then again, everyone will remain on the lists whether they have spoken in favour of escalation of the conflict or not.

Accordingly, being part of the war party is very beneficial for some Russian officials and politicians. But it must be kept in mind that the path towards escalation is one of personal gain, and not for the benefit of the entire Putin regime, and much less so for the country. While the careers of Volodin and Medvedev in pre-war Russia were in decline, and Turchak had reached the ceiling in his career, further conflict escalation flips the rules and gives them room for growth. Of course, if each of them had been promoted within the old pre-war system, they would have had far greater resources at their disposal, but members of the war party were not given that opportunity. In that sense, escalation is a bird in the hand of warmongering politicians. They have cornered Putin: as long as Russians support the war or are indifferent to it, the president cannot show any weakness. If the war party ups the ante, he must raise the stakes too.

In a sense, the war party increases the chances of the third scenario materialising. The worse the economic situation resulting from the continuation of hostilities, the higher the level of dissatisfaction. For Russia, an escalation of the conflict does not bode well; the more protracted the war, the longer it will take to rebuild the sanctions-stricken economy. The war party appears to be a party of personal gain for its members, but their personal interests are at odds with the interests of the country. From a strategic perspective, the ultra-patriots who are advocating conflict escalation turn out to be anti-patriots.

TOP READS

Back in the USSR

The poor against the war?

Serbia trapped in the Kremlin’s special operation

Why continue polling in Russia?

Europe’s Gamble and the End of Russia’s Oil Power

A mad printer: An updated version

2 notes

·

View notes

Video

Replica Tupolev ANT-25 'URSS N025' by Alan Wilson

Via Flickr:

The Tupolev ANT-25 was a record breaking long distance aeroplane, two of which were built in the mid 1930's. Pilotted by either Mikhail Gromov or Valery Chkalov, the two aircraft achieved several world records for long distance flights, both closed circuit and straight line. These eventually including flights from Moscow to the USA. In 1989 this full size replica was built for the museum by the Tupolev Design Bureau. It is on display in the original display hangar of the Russian Air Force Museum. Monino, Russia. 13-8-2012

1 note

·

View note

Quote

The ideal scientist does science and cares about nothing else. He wants to live this ideal. Now, I don’t think he really lives on this ideal plane. But he wants to.

Mikhail Gromov

1 note

·

View note

Text

Is the U.S. Withdrawal From Afghanistan the End of the American Empire?

Only time will tell whether the old adage about Afghanistan’s being the graveyard of empires proves as true for the United States as it did for the Soviet Union.

—By Jon Lee Anderson | The New Yorker | September 1, 2021

For two decades now, the U.S. has seemed increasingly unable to effectively harness its military prowess and economic strength to its advantage.Photograph by Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times / AFP / Getty

How does an empire die? Often, it seems, there is a growing sense of decay, and then something happens, a single event that provides the tipping point. After the Second World War, Great Britain was all but bankrupt and its Empire was in shreds, but it soldiered on thanks to a U.S. government loan and the new Cold War exigencies that allowed it to maintain the outward appearance of a global player. It wasn’t until the 1956 Suez debacle, when Britain was pressured by the U.S., the Soviet Union, and the United Nations to withdraw its forces from Egypt—which it had invaded along with Israel and France following Gamal Abdel Nasser’s seizure of the Suez Canal—that it became clear that its imperial days were over. The floodgates to decolonization soon opened.

In February, 1989, when the Soviet Union withdrew its military from Afghanistan after a failed nine-year attempt to pacify the country, it did so in a carefully choreographed ceremony that telegraphed solemnity and dignity. An orderly procession of tanks moved north across the Friendship Bridge, which spans the Amu Darya river, between Afghanistan and Uzbekistan—then a Soviet republic. The Soviet commander, Lieutenant-General Boris Gromov, walked across with his teen-age son, carrying a bouquet of flowers and smiling for the cameras. Behind him, he declared, no Soviet soldiers remained in the country. “The day that millions of Soviet people have waited for has come,” he said at a military rally later that day. “In spite of our sacrifices and losses, we have totally fulfilled our internationalist duty.”

Gromov’s triumphal speech was not quite the equivalent of George W. Bush’s “Mission Accomplished” following the 2003 Iraq invasion, but it came close, and the message that it was intended to relay, at least to people inside the Soviet Union, was a reassuring one: the Red Army was leaving Afghanistan because it wanted to, not because it had been defeated. The Kremlin had installed an ironfisted Afghan loyalist who was left to run things in its absence, a former secret-police chief named Najibullah; there was also a combat-tested Afghan Army, equipped and trained by the Soviets.

Meanwhile, the mujahideen guerrilla armies that had been subsidized and armed by the United States and its partners Saudi Arabia and Pakistan were in a celebratory mood. Their combat units were massed outside Afghanistan’s regime-held cities, and there was an expectation that it would not be long before Najibullah succumbed, too, and Kabul would be theirs. In the end, he held out for another three years, with his downfall merely leading to a new civil war.

For all the talk of internationalist duty, the Afghanistan that the Soviets left behind was a charnel ground. Out of its population of twelve million people, as many as two million civilians had been killed in the war, more than five million had fled the country, and another two million were internally displaced. Many of the country’s towns and cities lay in ruins, and half of Afghanistan’s rural villages and hamlets had been destroyed.

Officially, only fifteen thousand or so Soviet troops had been killed—although the real figure may be much higher—and fifty thousand more soldiers were wounded. But hundreds of aircraft, tanks, and artillery pieces were destroyed or lost, and countless billions of dollars diverted from the hard-pressed Soviet economy to pay for it all. However much the Kremlin tried to gloss it over, the average Soviet citizen understood that the Afghanistan intervention had been a costly fiasco.

It was only eighteen months after the Soviet withdrawal from Afghanistan that a group of hard-liners tried to launch a coup against the reformist premier Mikhail Gorbachev. But they had miscalculated their power, and popular support. In the face of public demonstrations against them, their putsch soon failed, followed by the collapse of the Soviet Union itself. Of course, by then, much beyond the Soviet Union’s Afghan quagmire had conspired to fatally weaken the once powerful Empire from within.

While the two events are humiliatingly comparable, only time will tell whether the old adage about Afghanistan’s being the graveyard of empires proves as true for the United States as it did for the Soviet Union. My colleague Robin Wright thinks so, writing, on August 15th, “America’s Great Retreat [from Afghanistan] is at least as humiliating as the Soviet Union’s withdrawal in 1989, an event that contributed to the end of its empire and Communist rule. . . . Both of the big powers withdrew as losers, with their tails between their legs, leaving behind chaos.” When I asked James Clad, a former U.S. Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense, for his thoughts on the matter, he e-mailed me, “It’s a damaging blow, but the ‘end’ of Empire? Not yet, and probably not for a long time. The egregious defeat has hammered American prestige, however, delivering the geopolitical equivalent of egg on our face. Is that a fatal blow? In the wider world, America still retains its offshore power-balancing function. And despite some overheated journalism, no irreversible advantage has passed to our primary geopolitical opponent—China.”

It is true that, for the time being, America retains its military prowess and its economic strength. But, for two decades now, it has seemed increasingly unable to effectively harness either of them to its advantage. Instead of enhancing its hegemony by deploying its strengths wisely, it has repeatedly squandered its efforts, diminishing both its aura of invincibility and its standing in the eyes of other nations. The vaunted global war on terror—which included Bush’s invasion of Iraq for the purpose of finding weapons of mass destruction that did not exist, Barack Obama’s decision to intervene in Libya and his indecisiveness about a “red line” in Syria, and Donald Trump’s betrayal of the Kurds in the same country and his 2020 deal with the Taliban to withdraw U.S. troops from Afghanistan—has effectively caused terrorism to metastasize across the planet. Al Qaeda may no longer be as prominent as it was on 9/11, but it still exists and has a branch in North Africa; isis has affiliates there, too, and in Mozambique, and, of course, as the horrific attacks last Thursday at Kabul airport underscored, in Afghanistan. And the Taliban have returned to power, right where it all began twenty years ago.

Rory Stewart, a former British government minister who served on Prime Minister Theresa May’s National Security Council, told me that he has observed the events in Afghanistan with “horror”:

Throughout the Cold War, the United States had a consistent world view. Administrations came and went, but the world view didn’t change that much. And then, following 9/11, we—America’s allies—went along with the new theories it came up with to explain its response to the terrorist threat in Afghanistan and elsewhere. But there’s been a total lack of continuity since then; the way the United States viewed the world in 2006 is night and day to how it views it today. Afghanistan has gone from being the center of the world to one in which we are told that such places pose no threat at all. What that suggests is that all of the former theorizing now means nothing. To see this lurch to isolationism that is so sudden that it practically destroys everything we’ve fought for together for twenty years is deeply disturbing.

Stewart, who co-founded the Turquoise Mountain Foundation—which has supported cultural heritage projects, health, and education in Afghanistan for fifteen years years—and is now a senior fellow at Yale’s Jackson Institute for Global Affairs, was skeptical of Joe Biden’s assertion that the strategic priorities of the United States no longer lie in places like Afghanistan, but in countering China’s expansion. “If this were true,” he said, “then clearly part of the logic of the American confrontation with China would be to say, ‘We’re going to demonstrate our values with our presence across the world,’ just as it did in the Cold War with the U.S.S.R. And one way you’d do that is to continue your presence in the Middle East and other places, because removing yourself is counterproductive. In the end, I think all of this talk about a China pivot is really just an excuse for American isolationism.”

Back to the nagging question: Does the return of the Taliban in Afghanistan represent the end of the American era? On the heels of what appears to have been a disastrous decision by Biden to adhere to a U.S. troop drawdown that was set in motion by his feckless predecessor, it can certainly be said that the international image of the United States has been damaged. It seems a valid question to ask whether the United States can claim much moral authority internationally after handing Afghanistan, and its millions of hapless citizens, back to the custody of the Taliban. But it remains unclear whether, as Stewart suggests, the U.S. retreat from Afghanistan represents part of a larger inward turn, or whether, as Clad believes, the U.S. may soon reassert itself somewhere else to show the world that it still has muscle. Right now, it feels as if the American era isn’t quite over, but it isn’t what it once was, either.

— Jon Lee Anderson, a staff writer, began contributing to The New Yorker in 1998. He is the author of several books, including “Che Guevara: A Revolutionary Life.”

0 notes

Text

Phi công Liên Xô mất một tay vẫn lái tiêm kích

Dù mất một cánh tay sau trận không chiến, Ivan Leonov vẫn khao khát được bay và tìm ra cách điều khiển tiêm kích bằng một thiết bị đặc biệt.

Với phi công tiêm kích trong Thế chiến II, việc bị thương và mất tay hoặc chân trong chiến đấu sẽ chấm dứt sự nghiệp tung hoành trên bầu trời. Tuy nhiên, một số ít phi công Liên Xô đã không chấp nhận số phận nghiệt ngã đó. Khoảng 10 người quay lại bầu trời dù mất chân và vài người vẫn bay dù mất tay, trong đó có phi công tiêm kích Ivan Leonov.

5/7/1943 trở thành ngày định mệnh với Leonov, phi công thuộc sư đoàn đổ bộ đường không 192 không quân Liên Xô. Khi trở về sau chuyến bay trinh sát khu vực diễn ra trận Kursk, phi đội của Leonov bị máy bay Đức tấn công. Gặp bất lợi về quân số, các phi công Liên Xô nhanh chóng thất thế, chiếc tiêm kích La-5 của Leonov lỗ chỗ vết đạn.

"Tôi thấy cánh tay trái của mình nóng rát, sau đó không còn cảm gi��c gì nữa. Tôi không thể cử động cánh tay trái, không thể làm bất cứ điều gì. Tôi ngất đi một lúc", Leonov nói và cho biết bằng cách nào đó ông vẫn bật được dù thoát khỏi chiếc La-5 đang bốc cháy.

Phi công Liên Xô Ivan Leonov. Ảnh: RBTH.

Các đồng đội sau đó tìm thấy Leonov và đưa ông tới bệnh viện. Tuy nhiên, các bác sĩ không thể cứu được cánh tay trái của Leonov và phải cắt bỏ đến gần vai. Leonov khi đó dường như chỉ còn cách giải ngũ hoặc xin làm công việc bàn giấy tại bộ tổng tham mưu quân đội Liên Xô.

Tuy nhiên, Leonov không chấp nhận số phận. Sau khi xuất viện vào tháng 3/1944, ông gõ cửa khắp nơi để xin được tiếp tục lái máy bay. Các tướng lĩnh Liên Xô ái ngại nhìn Leonov, ông không chỉ mất cánh tay trái mà còn bị thương ở chân trong vụ không chiến gần một năm trước đó.

Trung tướng Mikhail Gromov, chỉ huy tập đoàn quân đổ bộ đường không số 1, chấp thuận cho Leonov tiếp tục ngồi vào buồng lái "nếu tìm ra cách điều khiển máy bay". "Tôi hỏi Leonov rằng cậu ấy định thao tác với cần điều khiển trên máy bay sau khi mất một bên cánh tay thế nào?", Gromov kể lại.

"Leonov giải thích cặn kẽ về một thiết bị làm bằng hợp kim nhôm gắn vào vai trái, cho phép thao tác với cần điều khiển chỉ bằng chuyển động nhẹ. Leonov đã giải quyết được vấn đề làm thế nào để lái máy bay chỉ với một tay", tướng Gromov cho biết.

Ivan Leonov tại nhà riêng ở thủ đô Moskva của Nga tháng 4/2018. Ảnh: Kommersant.

Leonov chỉ mất vài tuần để quay lại buồng lái tiêm kích, song ông không thể tiếp tục tham gia các cuộc không chiến được nữa. Leonov sau đó gia nhập phi đội liên lạc 33 và điều khiển máy bay đa dụng U-2 (Po-2).

Ông nhận nhiệm vụ chuyển thông tin liên lạc bí mật cho sở chỉ huy, thư từ và các loại ấn phẩm khác nhau cho tiền tuyến, thậm chí chuyển thương binh và trinh sát hậu phương hoặc vị trí quân Đức. Trong một chuyến bay trên chiếc U-2, Leonov bị thương ở chân khi máy bay của ông trúng đạn đại liên.

Leonov thực hiện tổng cộng 52 nhiệm vụ bay chiến đấu sau khi mất cánh tay bên trái, trước khi chuyển sang làm kiểm soát không lưu trên mặt đất. Ông được trao ba Huân chương Sao đỏ vì cống hiến trên mặt trận. Sau khi Liên Xô đánh bại phát xít Đức, Leonov giải ngũ và mất tháng 6/2018, hưởng thọ 95 tuổi.

Nguyễn Tiến (Theo RBTH)

from Tin mới nhất - VnExpress RSS https://ift.tt/3lMcvib

via IFTTT

0 notes

Text

Logic is the most unrigorous subject. It's completely based on intuition and what we think should be right and wrong. There is no experiment that can check 'if A implies B and B implies C then A implies C'.

-- Mikhail Gromov

56 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cleaning soap-Bubble Pioneer Is First Lady to Win Prestigious Math Prize

U.S. mathematician Karen Keskulla Uhlenbeck has gained the 2019 Abel Prize--one of the sector's most prestigious awardscfor her wide-ranging work in evaluation, geometry and mathematical physics. Uhlenbeck is the primary girl to win the 6-million-kroner (U.S.$702,500) prize, which is given out by the Norwegian Academy of Science and Letters, because it was first awarded in 2003.

Uhlenbeck learnt that she had gained on 17 March, after a pal referred to as and advised her that the academy was making an attempt to contact her. "I was completely amazed," she advised Nature. "It was totally out of the blue." The academy introduced the award on 19 March.

Uhlenbeck is known for her ability with partial differential equations, which hyperlink variable portions and their charges of change, and are on the coronary heart of most bodily legal guidelines. However her lengthy profession has stretched throughout many fields, and she or he has used the equations to resolve issues in geometry and topology.

One among her most influential results--and the one which she says she's most proud of--is the invention of a phenomenon referred to as effervescent, as a part of seminal work she did with mathematician Jonathan Sacks. Sacks and Uhlenbeck have been learning 'minimal surfaces', the mathematical principle of how cleaning soap movies prepare themselves into shapes that reduce their power. However the principle had been marred by the looks of factors at which power appeared to grow to be infinitely concentrated. Uhlenbeck's perception was to 'zoom in' on these factors to that this have been brought on by a brand new bubble splitting off the floor.

She utilized related strategies to do foundational work within the mathematical principle of gauge fields, a generalization of the speculation of classical electromagnetic fields, which underlies the usual mannequin of particle physics.

Disparate fields

Uhlenbeck did a lot of her work within the early 1980s, when analysis communities that had grown aside have been beginning to discuss to one another once more, she recollects. "There was a real flowering of this relationship between mathematics and physics," she says. Mathematicians proved that they'd data helpful to physicists, who "had great ideas of objects to study that mathematicians couldn't come up with by themselves".

The work of different prizewinning mathematicians has been rooted in strategies launched by Uhlenbeck, says Mark Haskins, a mathematician on the College of Bathtub, UK, who was considered one of Uhlenbeck's doctoral college students. These embrace 1986 Fields Medal winner Simon Donaldson--who utilized gauge principle to the topology of four-dimensional spaces--and 2009 Abel laureate Mikhail Gromov, who studied a mathematical analogue of the 'strings' of string principle, wherein he discovered the effervescent concept to be essential.

Haskins says Uhlenbeck is a kind of mathematicians who've "an innate sense of what should be true", even when they can't at all times clarify why. As a scholar, he recollects generally being baffled by her solutions to his questions. "Your immediate reaction was that Karen had misheard you, because she had answered a different question," Haskins says. However "maybe weeks later, you would realize that you had not asked the correct question".

'Legit insurrection'

Karen Keskulla was born in Cleveland, Ohio, in 1942, and grew up partially in New Jersey, intensely excited about studying. "I read all of the books on science in the library and was frustrated when there was nothing left to read," she wrote in a 1996 autobiographical essay.

After an preliminary curiosity in physics, she earned her Ph.D. in arithmetic in 1968 from Brandeis College in Waltham, Massachusetts. She was one of the few ladies in her division; some teachers there acknowledged her uncommon expertise and inspired her, however others didn't. "We were told that we couldn't do math because we were women," she wrote within the 1996 essay. "I liked doing what I wasn't supposed to do, it was a sort of legitimate rebellion."

Uhlenbeck held positions at a number of universities--initially ignored or marginalized by male colleagues, she says--before settling on the College of Texas at Austin in 1987, the place she stayed till she retired in 2014.

Relentless advocate

Uhlenbeck has been a relentless advocate for girls in arithmetic, and based the Girls and Arithmetic programme on the Institute for Superior Research in Princeton, New Jersey. "She has been an enormous role model and mentor for many generations of women," says Caroline Collection, a mathematician on the College of Warwick in Coventry UK, and the president of the London Mathematical Society.

In 1990, she gave a plenary speech on the Worldwide Congress of Mathematicians--the solely girl to have accomplished so other than Emmy Noether, the founder of recent algebra, who spoke on the 1932 assembly. Uhlenbeck has earned a number of different prime recognitions, together with the U.S. Nationwide Medal of Science in 2000.

Uhlenbeck was at first a reluctant function mannequin. However after just a few successes by feminine mathematicians of her technology, she realized that the trail in the direction of honest illustration could be more durable than anticipated. "We all thought that once the legal barriers were down, women and minorities would walk through the doors of academia and take their rightful place." However fixing universities was simpler than fixing the tradition wherein individuals develop up, says Uhlenbeck. She hopes that her prize will encourage new generations of ladies to enter maths, simply as Noether and different impressed her.

This text is reproduced with permission and was first revealed on March 19, 2019.

Read the full article

0 notes

Text

Remembering the Soviet Withdrawal from Afghanistan

The final and complete withdrawal of Soviet combatant forces from Afghanistan began on 15 May 1988 and ended on 15 February 1989 under the leadership of Colonel-General Boris Gromov. Planning for the withdrawal of the Soviet Union (USSR) from the Afghanistan War began soon after Mikhail Gorbachev became the General Secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. Under the leadership of Gorbachev, the Soviet Union attempted to consolidate the PDPA's hold over power in the country, first in a genuine effort to stabilize the country, and then as a measure to save face while withdrawing troops. During this period, the military and intelligence organizations of the USSR worked with the government of Mohammad Najibullah to improve relations between the government in Kabul and the leaders of rebel factions.

The diplomatic relationship between the USSR and the United States improved at the same time as it became clear to the Soviet Union that this policy of consolidating power around Najibullah's government in Kabul would not produce sufficient results to maintain the power of the PDPA in the long run. The Geneva Accords, signed by representatives of the USSR, the US, the Islamic Republic of Pakistan and the Republic of Afghanistan (thus renamed in 1987) on 14 April 1988, provided a framework for the departure of Soviet forces, and established a multilateral understanding between the signatories regarding the future of international involvement in Afghanistan. The military withdrawal commenced soon after, with all Soviet forces leaving Afghanistan by 15 February 1989.

Events leading up to military withdrawal

Understanding that the Soviet Union's troublesome economic and international situation was complicated by its involvement in the Afghan War, Gorbachev "had decided to seek a withdrawal from Afghanistan and had won the support of the Politburo to do so [by October 1985]". He later strengthened his support base at the top level of Soviet government further by expanding the Politburo with his allies. To fulfill domestic and foreign expectations, Gorbachev aimed to withdraw having achieved some degree of success. At home, Gorbachev was forced to satisfy the hawkish military-industrial complex, military leadership, and intelligence agencies (later, Gorbachev would tell UN Envoy Diego Cordovez that the impact of the war lobby should not be overestimated; Cordovez recalls that Gorbachev's advisors were not unanimous in this pronouncement, but all agreed that disagreements with the US, Pakistan, and realities in Kabul played a bigger role in delaying withdrawal). Abroad, Gorbachev aimed to retain prestige in the eyes of third-world allies. He, like Soviet leaders before him, considered only a dignified withdrawal to be acceptable. This necessitated the creation of stability within Afghanistan, which the Soviet Union would attempt to accomplish until its eventual withdrawal in 1988-9. Three objectives were viewed by Gorbachev as conditions needed for withdrawal: internal stability, limited foreign intervention, and international recognition of the Democratic Republic of Afghanistan's Communist government.

Policy of national reconciliation

After the death of Leonid Brezhnev, the political will for Soviet involvement in Afghanistan dwindled. The level of Soviet forces in the country was not adequate to achieve exhaustive military victory, and could only prevent the allied DRA from losing ground. The Soviet Union began the gradual process of withdrawal from Afghanistan by instating Muhammed Najibullah Ahmadzai as the General Secretary of the Afghan Communist Party, seeing him to be capable of ruling without serious involvement from the Soviet Union. Babrak Karmal, Najibullah's predecessor, was deemed by the Soviet leadership to be an obstacle to both military withdrawal and the diplomatic process. Although Soviet military, diplomatic and intelligence agencies were not singleminded about his appointment, Najibullah was seen as a leader that could work with the Soviet Union in order to find a negotiated settlement. Mirroring shifts within the USSR itself, the Soviet effort in Afghanistan placed "a much greater emphasis on pacification through winning over rebel commanders" rather than transforming "Afghanistan along Marxist lines winning over the population through economic incentives and establishing a party and government influence in the cities and countryside". As a whole, the policies the Soviet Union and their allies powers in Afghanistan pursued after the transition of power from Babrak to Najibullah were referred to as the Policy of National Reconciliation

The Soviet-led attempts to encourage reconciliation were also complicated by mid-level military commanders, both Soviet and Afghan. While the military and political leadership of the USSR worked with the Najibullah government on raising the level of cooperation with rebel and tribal leaders, Soviet "mid-ranking officers sometimes failed to grasp the political significance of their operations" and the Afghan army had to be convinced "to stop calling the opposition "a band of killers," "mercenaries of imperialism," "skull-bashers,"'. Nevertheless, some progress was achieved by Soviet intelligence agencies, military and diplomats in improving relations with rebel factions. The canonical example is the establishment of tentative collaboration with noted rebel commander and Afghan National Hero (posthumously) Ahmad Shah Massoud. Here too, however, relations were complicated by mid-level military realities, and even by Najibullah himself. Although the Soviet military leadership and diplomats had been in contact with Massoud since the early 80's, military operations against his troops, the DRA's insistence on his disarmament, and information leaks about his relations with the Soviets derailed progress towards achieving a formal ceasefire with him. Conversely, Najibullah was in ostensibly regular contact with unnamed rebel leaders "through certain channels", as Cordovez found out during his first meeting with the Afghan leader.

Negotiations about non-interference of foreign actors

Faced by the failure of the Policy of National Reconciliation to stabilise the country by itself, and hoping to benefit from the gradually thawing relationship with the United States, the Soviet Union pushed forward with its effort to attain a diplomatic solution that would limit Pakistani and American interference in Afghanistan. Throughout 1987, Soviet diplomats attempted to convince the United States to stop supplying the mujahideen with weaponry as soon as Soviet forces withdrew, and to reach an agreement on a power-sharing proposal that would permit the PDPA to remain a key actor in Afghan politics. Najibullah was receptive to the prior, but the Soviet Union did not manage to come to this agreement with the United States. From statements made by Secretary of State Shultz, the Soviet leadership came under the impression that the US would cease military shipments to the mujahideen immediately after Soviet withdrawal, with the condition that the USSR "front-loaded" its withdrawal (i.e. withdrew the majority of its troops in the beginning of the process, thereby complicating redeployment). This was conveyed to the Najibullah government, managing to convince him that the Soviet-American diplomatic effort would benefit the Kabul government.

Process of military withdrawal

The withdrawal of Soviet military forces began on May 15, 1988, under the leadership of General of the Army Valentin Varennikov (with General Gromov commanding the 40th Army directly). As agreed, the withdrawal was "front-loaded", with half of the Soviet force leaving by August. The withdrawal was complicated, however, by the rapid deterioration of the situation in Afghanistan. While the US was not bound to stop arms shipments, and continued to supply the mujahideen in Pakistan, Pakistan did not deliver on its commitment to prevent weaponry and troops from flowing into Afghanistan. The mujahideen also continued their attacks on withdrawing Soviet forces. The Soviet Union repeatedly reported these violations of the Geneva Accords to UN monitoring bodies, and even pleaded with the US to influence the factions they supplied. The desire of the Soviet Union to withdraw, however, coupled with the United States' inability to control the behaviour of the mujahideen, meant that the Soviet objections did not bring any results.

As the Soviet withdrawal and rebel attacks continued, the deteriorating security of the Najibullah government caused policy disagreements between the different services of the Soviet Union. For example: while the Soviet military had succeeded in establishing a de facto cease-fire with Ahmad Shah Massoud's forces as Soviet troops withdrew through territories under his control, the KGB and Shevarnadze attempted to convince Gorbachev that an attack on Massoud was necessary to guarantee Najibullah's survival. In the words of Soviet military commanders, Najibullah himself also aimed to retain the Soviet military in Afghanistan – Generals Varennikov (in charge of the withdrawal operation), Gromov (commander of the 40th Army), and Sotskov (chief Soviet military advisor in Afghanistan) all pleaded with top Soviet military and political leadership to control Najibullah's attempts to use Soviet troops to achieve his own security, and to convey to him that the Soviet military would not stay in Afghanistan. After the departure of Yakovlev from the Politburo in the fall of 1988, Gorbachev adopted the Shevarnadze-KGB line of policy regarding supporting Najibullah at the cost of antagonising rebel factions, and a halt of the withdrawal was ordered on November 5, 1988. In December, Gorbachev decided to resume the withdrawal, but also to carry out an operation against Massoud, ignoring arguments from his advisors and military commanders on the ground. In January 1989, the Soviet withdrawal continued, and on January 23 Operation Typhoon began against the forces of Ahmad Shah Massoud. Up until the end of the military withdrawal, Shevarnadze and the head of the KGB unsuccessfully attempted to convince Gorbachev to retain a contingent of Soviet military volunteers in Afghanistan to defend land routes to Kabul. On February 15, the 40th Army finished their withdrawal from Afghanistan. General Gromov walked across the "Bridge of Friendship" between Afghanistan and the USSR last. When Gromov was met by Soviet TV crews while crossing the bridge, he swore at them profusely when they tried to interview him. Recalling the events in an interview with a Russian newspaper in 2014, Gromov said that his words were directed at "the leadership of the country, at those who start wars while others have to clean up the mess.

Aftermath

Soviet support for the Najibullah government did not end with the withdrawal of the regular troops. Aid totalling several billion dollars was sent by the Soviet Union to Afghanistan, including military aircraft (MiG-27s) and Scud missiles. Due primarily to this aid, the Najibullah government held onto power for much longer than the CIA and State Department expected. The mujahideen made considerable advances following the withdrawal of the Soviet contingent, and were even able to take and control several cities; nevertheless, they failed to unseat Najibullah until the spring of 1992. Following the coup of August 1991, the Soviet Union (and later the Russian Federation under Boris Yeltsin) cut aid to their Afghan allies. This had a severe impact on the Hizb-i Watan (formerly known as the PDPA), and on the armed forces, already weakened by their fight against the mujahideen and internal struggles – following an abortive coup attempt in March 1990, the Army (already encountering a critical lack of resources and critical rates of desertion) was purged. Ultimately, the cessation of Soviet aid and the instability that it caused allowed to the mujahideen to storm Kabul. Najibullah was removed from power by his own party, after which the mujahideen futilely attempted to form a stable coalition government. Disagreements and infighting between the likes of Massoud and Hekmatyar set the stage for the eventual rise of the Taliban.

Courtesy : Wikipedia

0 notes

Text

On This Day...

On this day in 1988, the Soviet 40th Army began a staged withdrawal from Afghanistan, which it had occupied since the 1979 invasion. The withdrawal was based on a timeline agreed up in Geneva one month earlier. The last Soviet troops left Afghanistan just under a year later, on February 15, 1989. Soviet-supported Afghan President Mohammad Najibullah managed to stay in power until he was ousted in 1992, with the nation plunging further into civil war as no one power controlled a majority of Afghan territory or loyalty. Into this vacuum stepped the Taliban, who successfully seized the capital of Kabul in 1996. The dire effects of this sequence of events continue to reverberate around the world today.

In 1978, the People’s Democratic Party of Afghanistan (PDPA) overthrew the self-proclaimed President Mohammed Daoud Khan, who had in turn ousted the nation’s last king, Mohammed Zahir Shah in 1973. The PDPA oriented the nation towards a Marxist, centrally planned economy and instituted large-scale modernization programs, many of which upset the conservative, rural citizens, many of whom took up arms against the new government. The government in Kabul responded with vigorous suppression of this dissent, jailing over 27,000 political prisoners. By spring 1979, large portions of the countryside were in open revolt and the stability of the PDPA in Kabul was questionable. In response to this chaotic environment on the Soviet frontier, Premier Leonid Brezhnev ordered the Red Army to intervene. The 40th Army deployed from its bases in Uzbekistan on Christmas Eve 1979 and entered Afghanistan at three border points, quickly securing control of Kabul. A new government was installed at Soviet instigation and Babrak Karmal became the new president.

Karmal represented a faction of the PDPA the Soviets preferred, and the occupation of Afghanistan represented a policy of transforming Afghanistan, a previously pro-Western state, into a Communist controlled satellite of the Soviet Union on the doorstep of south Asia. From airbases in Afghanistan, the Soviet military gained the ability to project air power and a strategic presence into the Indian Ocean, where the U.S. Navy maintained a near constant presence in the form of aircraft carrier battle groups. It also put the Soviet Union closer to Pakistan and India, two nations it sought to gain influence with.

As the 40th Army built up a vast military infrastructure across Afghanistan’s major population centers and propped up the Afghan military, the rural opposition forces formed up into formal militia factions, broadly termed the Mujahideen. These factions attacked Soviet and Afghan troops, ambushed convoys, raided towns and military installations, and even fought each other. Some were supplied with weapons and aid by the United States and Pakistan; the complex circumstances of which were covered in great detail in both the book and later movie Charlie Wilson’s War.

After the death of Brezhnev in 1982, the Soviet Union went through a quick exchange of new leaders. Yuri Andropov served only 15 months before dying in February 1984. His successor, Konstantin Chernenko, lasted only 13 months, passing away while in office March 1985. Brezhnev, Andropov, and Chernenko were all elderly men with serious health issues and who represented a previous generation of Soviet policy. A clamor within the party led to the appointment of the relatively youthful Mikhail Gorbachev to succeed Chernenko in 1985. Gorbachev promised reforms and pursued policies which opened Soviet society for the first time in decades. He also sought to find a reasonable resolution to the continued Soviet occupation of Afghanistan, which was beginning to take a serious toll on the Soviet economy.

Though the government in Moscow continued to spend substantial sums on maintaining the 40th Army in Afghanistan, the size of the force was not sufficient to force back the various rebel groups, but instead was only enough to prevent the Afghan Army from losing more ground. Sending in further units was out of the question due to the added economic hardship it was likely to cause. In order to reform Soviet society, he needed a healthy economy. In order to achieve this goal, Gorbachev reasoned that ridding itself of the Afghanistan problem, the so-called “Bear Trap” or “Soviet Union’s Vietnam,” was a necessary first step. Gorbachev received approval from the Politburo, the supreme governing council of the Soviet Union, in fall 1985 to pursue this path, but Soviet withdrawal had to be predicated on leaving a stable, self-sustaining government in Kabul.

Negotiations between the Soviet Union, United States, Pakistan, and Afghanistan began in Geneva. The U.S. and Pakistan insisted on a “front-loaded” withdrawal; meaning that the majority of Soviet forces in country would be removed right away, with a phased timetable for the remaining forces. The Soviet Union countered that they would only agree to such a provision if the United States stopped supplying weapons to the Mujahideen and Pakistan closed the border to weapons transfers. None of the factions of the Mujahideen were represented at Geneva and none recognized as valid the subsequent agreement between Afghanistan and Pakistan, with the U.S. and U.S.S.R. as guarantors. A United Nations observer office was installed in Afghanistan in May 1988 to report on adherence to the agreement by all parties.

Despite the wishes of Afghan President Najibullah, who wanted the Soviet military to retain a large presence in Afghanistan for as long as possible, the Soviets did agree to a front-loaded withdrawal and the United States did agree to halt weapons shipments to the Mujahideen. Pakistan, however, failed to prevent weapons from other sources entering Afghanistan and the Mujahideen, who cared little about the Geneva agreement, attacked withdrawing Soviet columns at will. Complaints to the UN observer office in Kabul and to the United States accomplished little as neither party had any leverage with the Mujahideen groups. Moreover, American knowledge that the Soviet Union greatly desired to get out of Afghanistan rendered as impotent any threats by Soviet diplomats that they might halt the withdrawal.

The economic damage caused by the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan was one of many factors that fatally undermined the Soviet economy, which lead to the upheaval against the one-party state in 1991. General Valentin Varennikov, the commander who oversaw the Soviet withdrawal 1988-1989, was one of the key figures in the attempted coup against Gorbachev in August 1991, an event which, though unsuccessful, sounded the death knell of the Soviet government. One of Varennikov’s senior officers in 1988-1989, Boris Gromov, remains prominent in Russian politics today.

After he was ousted in 1992, Mohammed Najibullah resided in the safety of the United Nations compound in Kabul. In 1996, the Taliban, one of the strongest groups to emerge from the Mujahideen, marched on Kabul and seized power. In the chaos that followed, Najibullah and his brother were captured by Taliban soldiers and publicly executed on the streets of Kabul for alleged crimes he committed while in office. The Taliban regime allowed Afghanistan to become a refuge for certain terror groups to train and organize attacks around the world. We continue to live today with the effects of this outcome, and are left to ponder whether, after 16 years in Afghanistan--or 6 years longer than the Soviet Union--whether the United States has failed to learn the lessons of its former Cold War foe.

#On This Day#RTARLAD#history#Soviet Union#United States#Cold War#Afghanistan#occupation#geopolitics#foreign policy#military#war#Taliban#mujahideen#communism#coups#politics#United Nations

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Icebreaker (2016)

Cerita ini didasarkan pada peristiwa nyata tahun 1985. Tim pemecah kutub kutub Rusia "Mikhail Gromov" menemukan gunung es raksasa. Kapal itu menjadi tabrakan ketika mencoba untuk berlindung dari cuaca dan terpaksa hanyut dengan es di sepanjang pantai Laut Amundsen. Awak "Gromov" menghabiskan 133 hari malam kutub mencoba menemukan jalan keluar dari perangkap es mereka. Mereka tidak memiliki ruang untuk kesalahan; satu gerakan salah dan kapal hancur oleh es.

Read the full article

0 notes