#Palazzo Loredan

Text

Davide Battistin - Genesis - Palazzo Loredan, Venezia 27-01-20234

Pagina Mostra

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

ITALICO BRASS. Pittore di Venezia

Prima grande mostra veneziana dedicata a Italico Brass, nonno del regista Tinto Brass, e alla sua visione di Venezia

0 notes

Text

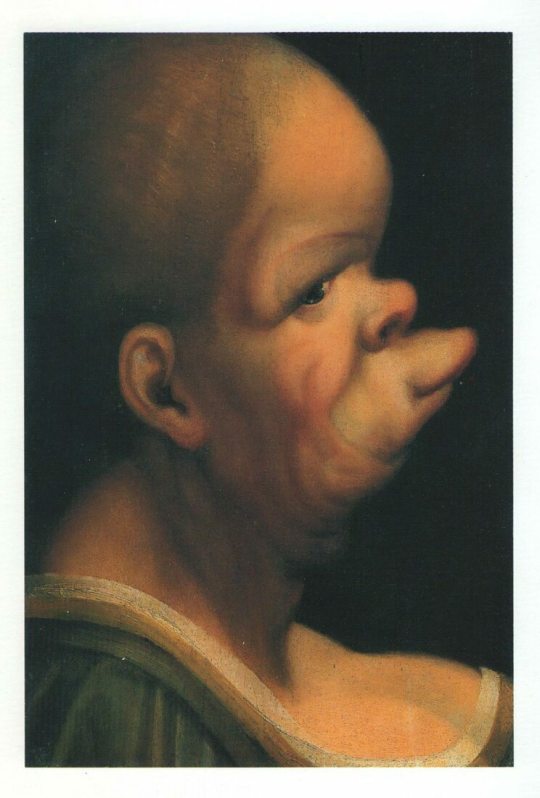

Two monstrous exhibitions!

As DISØRDINARY BEAUTY 🥀 is a collection series mainly focusing on “ugliness”, what I like to call “The Thorn Sense of Beauty”, I am glad to see that two shows are happening to focus on those “imperfect” human facial features.

The two exhibitions I am referring to are “De’ Visi Mostruosi e Caricature. Da Leonardo da Vinci a Bacon” happening in Venice at Palazzo Loredan, and the second one is “The Ugly Duchess: Beauty and Satire in the Renaissance” now on show in London at The National Gallery.

Both shows aim to present the way “extreme” facial features were depicted by artists. Mostly grotesque caricatures, what Karl Rosenkranz calls the “comic” side of ugliness in his book “Aesthetic of Ugliness” (Aesthetik des Hässlichen), 1853.

The semantic evolution of ugliness is well described by Umberto Eco in his work “On Ugliness”, 2007, where the semiologist draws a very well-detailed and complete history of the ugly in art, literature, religions, States, and society, very often also quoting the work by Rosenkranz.

Ugliness has always been associated with the evil side of human nature, such of thieves, murderers, and criminals of all sorts. But also with the Devil and Death, and also diseases, the deformed, the mutilations, everything that would contrast and be the opposite of universal beauty, harmony, perfection, and peace.

But, there is also a comic side of ugliness, that finds its best representation in the art of caricatures, where physical and facial expressions were exaggerated to the point of becoming ridiculous, the above called the comic side of ugliness.

The caricature works were used often to mock the wealthy and powerful, but also as studies of human anatomy. But, it often also represents the dark side of human psychology as often facial features considered imperfect were also associated with unhealthy minds, crazy people, the mad ones.

Image 01: Francis Bacon, Three Studies for a Portrait of Isabel Rawsthorne, 1965, Sainsbury Center for Visual Arts, Norwich, UK © The Estate of Francis Bacon.

Image 02: Quinten Massys, “The Ugly Duchess (An Old Woman)” (1513) (image via Wikimedia Commons).

Image 03: Giovan Paolo Lomazzo (1538-1592), Grotesque head of a woman facing right, about 1560, oil and tempera on wood, 26 x 18 cm Private collection, Milan ©Vivi Papi

Image 04: Seven Grotesque Profiles After Leonardo da Vinci about 1560. © The Trustees of the British Museum

#exhibition#museum exhibit#leonardo da vinci#venice#londo#art show#show#caricature#grottesco#painting#fine art#The National Gallery#Palazzo Loredan#art exhibition#portrait#portraits#art#artwork

1 note

·

View note

Text

Manuel Santelices (Chilean, b. 1961)

Palazzo Loredan, 2020

Watercolors and inkjet on archival paper

178 notes

·

View notes

Text

Le mostre del weekend, dal Modernismo francese a Dadamaino

(di Marzia Apice)

Il Modernismo francese e

Dadamaino, fino ad Antonio Ligabue e Giuseppe Pende: sono alcune

delle mostre di questa settimana.

VENEZIA – È una Venezia onirica, surreale e fuori dall’ordinario

quella proposta da Davide Battistin nella mostra “Genesis”, dal

15 dicembre al 18 febbraio a Palazzo Loredan – Istituto Veneto

di Scienze Lettere ed Arti. Esposta una nuova serie di…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

John Ruskin- Southern front of the Basilica of San Marco, from the Loggia of Palazzo Ducale, 1851, Study of the Marble Inlaying on the Front of the Casa Loredan, 1845, A Window in The Foscari Palace, Venice, 1845

0 notes

Photo

Capo di Stato Loredan Gasparini Venegazzu Superiore Montello dei Colli Asolani Doc 2003-2018 , emozione verticale 🍇🍷🔥 • • • • • Dalla famiglia che ha inventato il taglio bordolese all’Italiana, uno dei vini che mette la zona dei @ivinidelmontello come riferimento per i vini da Cabernet e Merlot nel nostro paese. • • • Questa Riserva nasce nel 1964 ed è frutto di una selezione di uve delle nostre vigne vecchie, dove cloni ormai introvabili creano un vino rosso dal carattere unico ed originale. • • Nel 1967 Tono Zancanaro (1906-1985) dedica a questo vino Del Conte Loredan due sensuali opere che esprimono la duplice anima maschile e femminile della “uva” (femminile) che diventa “vino” (maschile). Una “Lei” ed un “Lui” fusi nella medesima essenza. Da quel momento “Des Roses pour Madame” e “…pour Monsieur la Bombe” diventano l’immagine in etichetta. Poi, nel corso degli anni, il vino ha continuato ad essere prodotto con la sola etichetta del “Lui” riservando la “Lei” a particolari occasioni. • • • #venegazzu #rossobordo #wine #vino #bordolese #capodistato #montello #wine #vino #andreagori (presso Palazzo Giacomelli - Spazio Assindustria Venetocentro) https://www.instagram.com/p/CjyZKNHt6EY/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

0 notes

Photo

Ca 'Vendramin Calergi , Venice, Italy

#art#interior design#design#Architecture#palace#palazzo#italy#venice#luxury homes#luxury lifestyle#palazzo loredan vendramin calergi#history#style#doors#ca' vendramin

438 notes

·

View notes

Text

Palazzo Loredan, Venezia

17 notes

·

View notes

Photo

View up the Grand Canal toward the Rialto, Francesco Guardi, c. 1785, Minneapolis Institute of Art: Paintings

Cityscape of Venice Venezia This is exactly the kind of painting a British aristocrat would purchase as a memento of his Grand Tour of the major cities of Italy. In the 1700s, the Grand Tour was a way for elite young men to learn about art and history and improve their taste. The Grand Canal, the principal waterway of Venice, winds through the city from the railway station to the Piazza San Marco, where it meets the Adriatic Sea. In this late afternoon view, Francesco Guardi portrayed a section of the canal from a vantage point looking northeast toward the Rialto bridge. Many of the buildings seen here still exist and are identifiable due to Guardi’s exacting detail. The first two palaces at the far right, the Ca’ Farsetti and the adjacent Palazzo Loredan, today function together as the city hall.

Size: 25 3/4 x 35 7/16 in. (65.41 x 90.01 cm) (canvas) 33 1/8 x 42 5/8 x 2 3/4 in. (84.14 x 108.27 x 6.99 cm) (outer frame)

Medium: Oil on canvas

https://collections.artsmia.org/art/1317/

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Italico Brass - Palazzo Loredan, Venezia 04-11-2023

Pagina ufficiale

View On WordPress

1 note

·

View note

Text

Venezia e la scienza, due secoli di sostenibilità

Il progresso scientifico e tecnologico si è posto a servizio della città, perché non rimanesse esclusa dal processo di modernizzazione, senza perdere al tempo stesso le sue caratteristiche e le sue peculiarità

0 notes

Photo

Today's #ManuscriptOfTheDay is LJS 59, a dogale issued by Doge Leonardo Loredan to Paolo Nani, podestà and capitaneus of Treviso. Issued from the Palazzo Ducale (Doge's Palace), Venice, dated 25 May 1517 #medieval #manuscript #venice #dogale https://instagr.am/p/COVsomGgFYz/

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Balkanising Bellini – part one

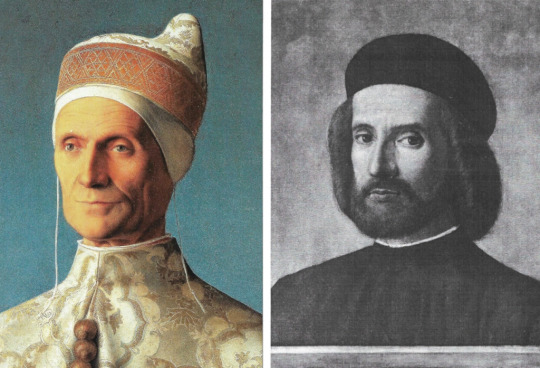

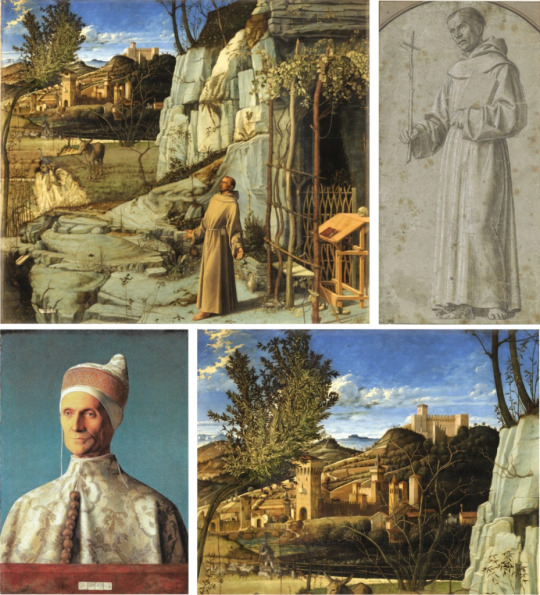

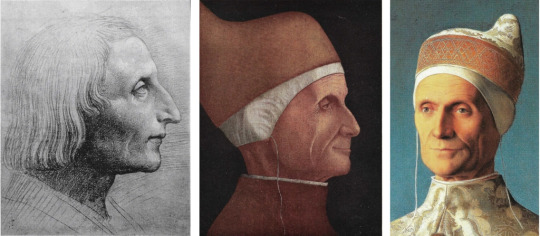

Quests in connoisseurship begin most usefully with the juxtaposition of a painting and a drawing. Here is such a juxtaposition: the famous portrait, labelled IOANNES BELLINUS, Giovanni Bellini, depicting the Doge of Venice, Leonardo Loredano, in the London National Gallery; and next to it, a portrait drawing of an Unknown Man, ascribed to the Venetian School, in the museum at Besançon.

Portrait of Doge Loredano (National Gallery London) ; Unknown Man (Musée des Beaux-Arts Besançon)

To my eye it is a certainty that the same artist was responsible for these two items. What the above pairing establishes is that he was an artist with characteristics equally visible in his painting and his drawing. In either case we can observe the long sealed mouth with a thin upper lip, noticing how it ends on each side with a bracket-like crease. We can consider the modelling of the upper, bonier part of the nose, shadowed on its right flank, and move on to the eyes, each with an upper and lower lid forming two parts of a convex cover that has opened so far and could close and seal up the eye itself. This convex form, the eye and its lids, is set deep within the concave socket described by the eyebrow above, the embankment of the nose, the cheekbone, and the bone where the temple comes down at the eye’s edge and the ‘crow’s feet’ lines appear in sitters of this age.

What is most apparent, and most to be emphasised, is the manner in which the skin, modelled in light and dark, is drawn tightly over a fine bone structure. In the painting there is particularly strong lighting round the cheekbone and temple, but in both the drawing and the painting we apprehend immediately where the hard bone is; we feel that we could tap, and hear, the chin, the cheekbones, the top of the nose and the temple of each man. A bonus of such modelling is the beautiful profile to the edge of the face: the taut line from the forehead in towards the eye, out to the cheekbone, in again at the level of the mouth, and out again for the last time before shelving in towards the chin.

With all this tight clothing of flesh over bone goes a distinctive expression: a calm, steady appraisal by someone who holds himself erect and still, whose lips are sealed but whose eyes are open, surveying us and the world with a judicious gaze reflecting, one infers, a mind not swayed by recklessness or sudden passion. In both cases the line that runs down the middle of the face, through nose, philtrum and chin, continues to descend, below the neck, in the line of the dogal toggles and in the stronger edge of the Besancon man’s lapel. These men are anchored.

The man in the drawing appears to be the same as the subject of a portrait once in the Marchwood collection at Ashford in Kent, that Bernard Berenson ascribed to Lotto.

Unknown Man ; Portrait of a Venetian Dignitary (Marchwood poss Charnwood Collection, Kent)

What, if anything, could we now add to this pair, and be similarly sure of the same hand being at work?

Doge Loredano (National Gallery London ; Portrait of a Man in a Beret (Goudstikker Collection Rotterdam)

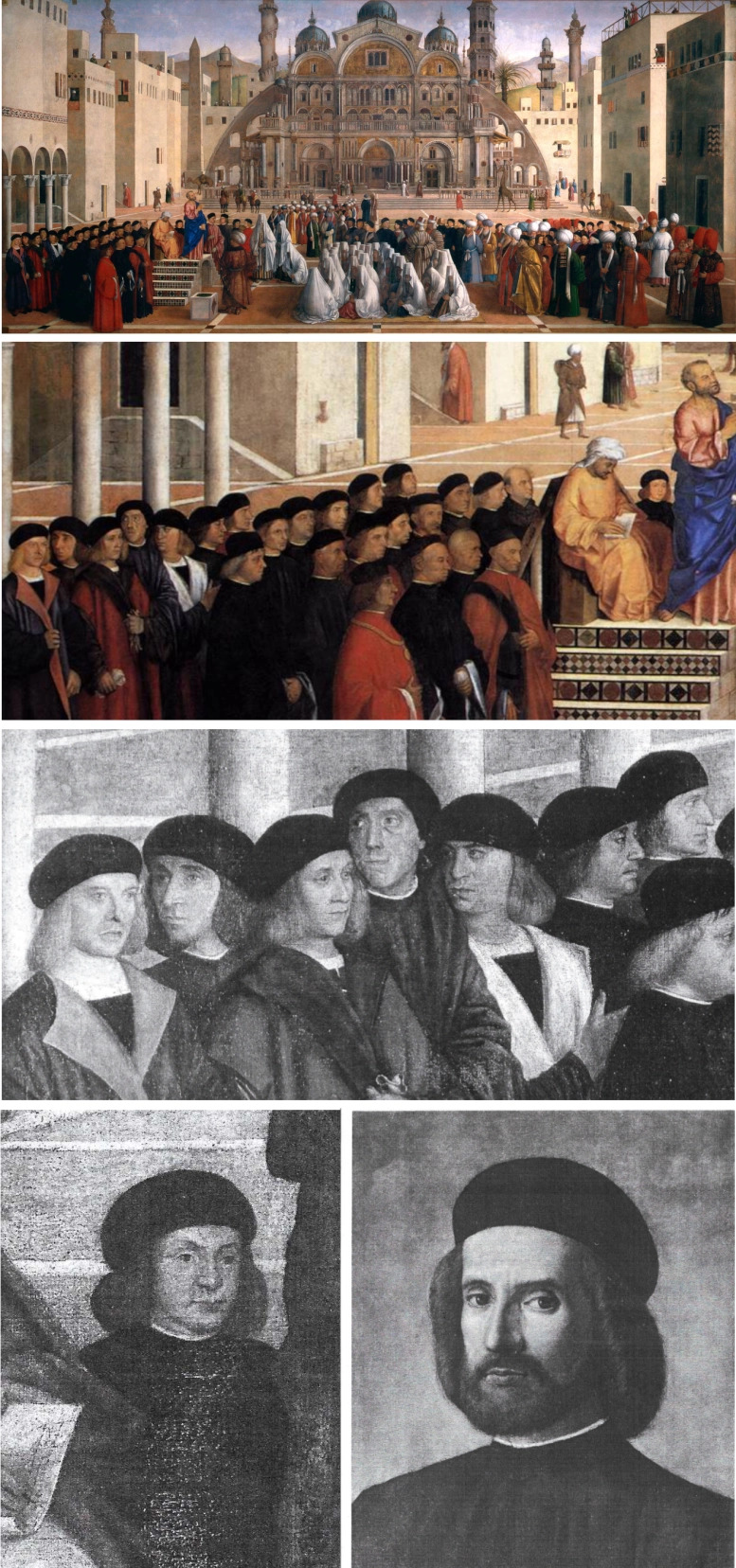

At Rotterdam, from the Goudstikker collection, comes a fine portrait of a younger-looking man wearing a beret. He has a lot of hair on and around a face that bears an expression similar to that of the Doge and the man in the Besancon drawing. As he looks at me with that calm, appraising eye, I feel no doubt that he was the product of the same hand. Particularly interesting, however, is the resemblance of this face to that of another man in a beret, the one whose head we see behind the standing figure of Saint Mark Preaching in the painting of that title in the Brera Gallery at Milan. This is an extremely helpful connection because it leads us away from single heads, painted and drawn, to a big crowd scene that is full of heads, and therefore a valuable source of comparisons as we proceed.

Top – St Mark Preaching ‘Predica di San Marco’ (Breara Milan) ; Centre and Bottom Left – Details from St Mark Preaching ; Bottom Right – Portrait of a Man in a Beret (Goudstikker Collection)

If we turn to the far left of the Brera picture, we find among the ranks of men in berets some who might have sat for the artist singly. In Berlin there is a drawing of a man looking three-quarters to our right. His nose is similar to that of a monk, in a painting from the Houston-Boswell collection in London, and formerly at San Diego, California (since sold), is a painted portrait of a man seen above a parapet with a background of sky and clouds.

Clockwise from Top: Detail from St Mark Preaching ; Portrait of Paolo Morisini (ex-San DIego) ; Portrait of a Monk (Private Collection) ; Portrait of a Man (Kupferstichkabinett Berlin)

Over on the right of the Saint Mark Preaching we see bearded Turkish elders in tall ‘busby’ hats, one of them wearing a robe with a pattern broadly comparable with what we see in the Loredano portrait. These conversing men call to mind a drawing, Three Turks, at Windsor. That drawing is related to a group at the left of another ceremonial scene, the Reception of the Venetian Ambassadors at Cairo. The character of the drawing and the structure of the faces are all of a piece with what we have already discussed.

Top Left: Three Mamluk Dignitaries (Royal Collection Windsor) ; Top Right, Centre Right: Details from St Mark Preaching ; Bottom: Detail from The Reception of the Ventian Ambassadors at Damascus or Cairo (Louvre)

We are starting to see connections between the Loredan portrait, various individual male portraits and portrait drawings, and at least one large crowd scene containing numerous other male portraits. The Saint Mark Preaching is said to have been finished by Giovanni at the request of his brother, Gentile Bellini. Are we entitled to conclude that Gentile, having painted (with or without help all the architecture at the back and sides of the Square, and thus set the stage, left his brother to put in the crowds that form such a distinct and stylistically coherent band across the lowest third of the picture? This is what our links with figures in that band begins to suggest. An oeuvre is building here that seems to connect with Giovanni Bellini, yet not at all with many famous pictures that bear his name in books and on gallery walls. Nothing, so far, indicates that we are looking at the work of the painter of The Madonna of the Meadows, for example, or the (different) painter of The Agony in the Garden; both of those paintings hang near the Loredan portrait, and both are assigned, like it, to Giovanni Bellini.

Clockwise from Top Left: Doge Loredano ; Madonna del Prato (National Gallery London) ; Agony in the Garden (National Gallery London)

Looking again at the Loredan portrait, at the modelling around the eyes, the lined temple, the general structure of the face, I think of a Madonna and Child with Saint Jerome in the Castelvecchio Museum in Verona, in particular the head of Saint Jerome, but also in the face of the Virgin: the same strongly hooded eyes of the Doge either side of a straight, narrow nose, and a definite chin. I see, in the naked body of the Christchild, that tight covering of flesh over bone; and in the brocade backdrop the large pattern now familiar from the Loredan portrait and certain robes in Saint Mark Preaching.

Juxtaposition from Top – Madonna and Child with St Jerome (Castelvecchio Verona) ; Centre – Pencil Drawing of the Madonna (Mueller Sale Amsterdam 1929) and Detail of the Madonna and St Jerome ; Bottom – Doge Loredano and Detail of St Jerome

Portrait of Doge Loredano with Venetian Lagoon (possibly since restored)

I detect our master’s hand, not Mansueti’s, in this picture, and I see no ‘Florentine master’s hand, but his Venetian one in a drawing for a Madonna’s head – so like the Verona one – sold by Mueller in Amsterdam (21 Nov. 1929, Lot18) which has a sketch for a Christchild’s leg, lower left, all in a style compatible with the other drawings we have considered.

From that drawing and that Verona painting we can move to another painting – again, alas, only known from a Sale catalogue – a Portrait of a Lady in a Rich Dress. The facial type in this portrait (Medlycott Sale, Sotheby, London 3 July 1929, Lot 27) is that of the Madonna, but note should be taken also of the pattern across her bust which is closely paralleled in the horned cap of both Doge Loredano and Doge Mocenigo, the latter as seen in profile in a portrait from the Howard Young Galleries in New York and another Loredan (now definitely an old man) in a painting sadly destroyed by fire at Dresden in 1945. Set beside the latter a drawing in the Uffizi, and one can see what time does to a face. Compare at this point the nose of Mocenigo and that of an Unknown man in a drawing at the Uffizi. Compare also the head of Saint Peter in a panel ascribed to Giovanni da Udine at a Berlin sale (Kaufmann, 4 Dec 1917) with that of London’s Loredano; and thirdly, the head behind St Peter with the head of the Lady in a Rich Dress.

Clockwise from Top Left: Portrait of a Lady in a Rich Dress (Sothebys 1929) ; Head of a Man (Uffizi) ; Saint Peter with John the Evangelist and St Paul (last sold Berlin 1917) ; Doge Giovanni Mocenigo (Frick Collection New York) ; Doge Mocenigo (last sold Howard Young Galleries New York)

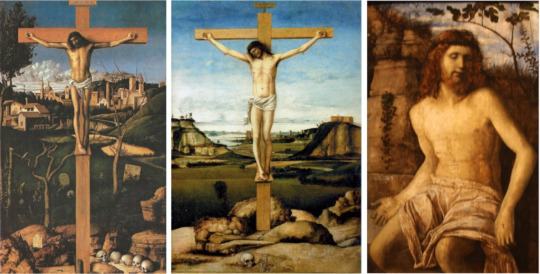

Returning to the Verona painting, but with a focus on the Child I see a connection with a Crucifixion panel from a Florentine collection (Count Niccolini da Canugliano). This work has the blue-white-bronze palette characteristic of the artist; but in the figure of Christ there is the same spare physique as the Child has, considerably elongated but with no fat on it, the flesh stretched over the skeleton in that rather Ghiberti-like manner of modelling. Something of this recurs in another Crucifixion in the Corsini gallery at Florence and in a Christ in the Tomb at Stockholm.

Crucifixion (Palazzo degli Alberti Prato) ; Crucifixion (Corsini Collection Florence) ; Christ Crowned with Thorns (National Museum Stockholm)

A drawing that I have omitted, in the Louvre, is relevant at this point. It shows a Saint in the habit of a monk, holding a tall slender cross in his right hand. Comparison should be made with the Windsor drawing of the three men conferring: the strong black-to-white transition from one side of the cheek-bone to the other, and from the lit to the shadowed side of a fold, links these and other drawings and paintings by this artist. Note also how he favours a tall figure – here emphasised by being seen sotto in su – and the tall stem of the cross, tall as the cross, and the figure on it in his Crucifixions. The Louvre Saint is – and here comes the climax of our investigations – the type of St Francis in what is perhaps the artist’s surviving masterpiece, the great Saint Francis in Ecstasy in the Frick Collection in New York.

Clockwise from Top Left: St Francis in the Desert (Frick Collection) ; St Francis (Louvre) ; Background detail from St Francis in the Desert ; Doge Loredano

The Frick Saint Francis returns us to London in the sense that, for all its complicated organisation, it is built in the same chromatic range (present also in the Niccolini Crucifixion), the colour-scheme of a golden autumnal landscape of brown earth and pale rock, that has not seen rain for many days but been baked under a blue sky. Here it is the flesh of the Earth itself that is stretched tight over rock, and the rock, showing through it, is as hard as the cheekbone or temple or chin of the Doge. Here ecstasy is not ecstatic in any outward show; a vision of the world is seen out of an eye deep-set in its cavern, a socket in the rock and bone of the earth. It is a vision, but one of creatures like the Saint living at the base of a far taller world, tall as the sky.

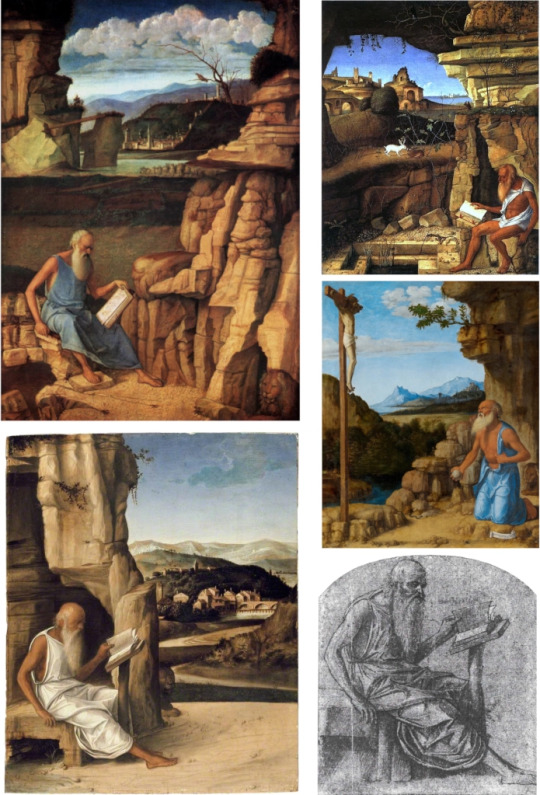

Clockwise from Top Left: St Jerome Reading in the Countryside (National Gallery London) ; St Jerome Reading in the Countryside (National Gallery Washington) ; St Jerome with Stone and Crucifix also attrib Cima da Conegliano (Kress Washington) ; St Jerome Reading (Berlin Print Rooms) ; St Jerome Reading (Ashmolean Museum Oxford)

The colour-scheme and the bare-rock landscape that we see in the Frick Saint Francis are evident in several versions of Saint Jerome Reading, notably the one in Washington’s National Gallery and another in London’s. The consistent adoption of this blue-bronze palette does seem to be a defining factor in distinguishing this artist from others labelled as ‘Bellini’.

Left to Right: Head of a Man (Uffizi) ; Doge Loredano (M.H. de Young Museum San Francisco) ; Doge Loredano (National Gallery London)

Our artist would appear to be the official painter of the Doge, and Leonardo Loredano is portrayed again, much older, more gaunt, in a panel at the M. H. de Young Memorial Museum in San Francisco. The burnt brown colouring, relieved only by a creamy white, is expressively autumnal and sad.

We can begin to imagine that for the artist as well as for us Leonardo Loredano was more than an individual with unique facial features. In London his head, chest and shoulders rest on a parapet, like a bust on a marble shelf; as such he is an icon (much as a Madonna is), – yes a, not the – but an icon, I suggest, of Good Government. In reality the Doge of Venice did not have much power, but what is historically true seems of little relevance in front of this image. I could be told that he was a weak and ineffectual head of state, I could even be told that he was a cruel tyrant, and my reaction to the portrait would not change, because the effect of it is to remind us that, for all the evidence of misgovernance in so many parts of our own world, the possibility of good governance is still with us, as it was in the time of the artist. And there is the face of it: shrewd, wise, calm, just. Ambrogio Lorenzetti had found his own, allegorical, way to depict Good Government for the city of Siena. Giovanni Bellini did it another way for his, by portraying a ruler who just looks as if he would act wisely.

The above remarks prompt an interesting question: what difference would it make to our response if we were presented with Loredano’s head only? The answer must surely be that in this special case – a portrait of a ruler – we would lose a sense of the head ruling over the body, not just personally but politically. A bust gives us convergence from two sides as we follow the majestic line of the shoulders going upwards to the neck and the head. This is the Venetians looking upwards to their Head of State, a fount of authority that flows back down again, as down the neck of a flask, except that the flow is cut off by the barrier of the parapet; the people are kept at a distance, the very dignity of his position removes him from them – as indeed it did. A pictorial convention much favoured in the Bellini workshop for Virgin and Child pictures and portraits of lesser mortals has, in this case, a particular expressive connotation.

We are left with the cartellino, the same lettering on the Frick Saint Francis as on the Doge Loredano in London.

Cartellino details from Saint Francis in the Desert (Left) and Doge Loredano (Right)

If we are to believe that Gentile got his brother to finish the Saint Mark Preaching, then it follows from my connoisseurship argument and its trail of comparisons that the Doge Loredano in the National Gallery is an authentic work by Giovanni Bellini. The point that I wanted to make in calling this essay Balkanising Bellini – Part One was to suggest that not all the works with ‘Bellini’ labels, whether painted into the images or affixed beside them on gallery walls, are by Giovanni. It will need future Studies to demonstrate this, but if we agree to say that Giovanni is the author of the Loredan portrait, we have to question, and sooner or later deny, his authorship of many other paintings and drawings attributed to him, including most, if not all, the ‘Bellini’s in the London National Gallery. The corpus of all attributions to Giovanni Bellini (as to Rogier van der Weyden) is in reality no corpus, no coherent body of work, at all; it is a very unsatisfactory miscellany, a territory, as it were, that needs to be split up into separate states, each with the sort of identity that unites, I now think, this Loredan Master’s output.

Scholars accept that there was a workshop system, and they know a lot more about it than I do; but when they come to the task of attributing works, they are often affected by the ‘famous name syndrome’ that is rife among curators. The label ‘Giovanni Bellini’ becomes as prestigious for the modern museum as it was for the original Venetian clientele. It is known intellectually, but forgotten in practice, that ‘Giovanni Bellini’ means a firm named after the head of it, an individual called Giovanni Bellini, of the Bellini family, who worked in the shop alongside an unknown number of other artists. The commissions came in, work was allocated, in whole or in part, to this artist or that artist, and when the work was finished, it went out, duly labelled with the name of the firm.

The connoisseur – this one anyway – is understandably daunted by the huge task of sorting out the different hands responsible for these ‘Bellini’ products, but it needs to be undertaken if we are not to live with confusion and misapprehension. Pictures labelled with a name will have to be replaced with no name, an anonymous master of extant work that nevertheless has some stylistic coherence. I chose the Loredan portrait as a starting point because I admire it. Perhaps it really was painted by Giovanni Bellini and the label tells the truth; but if so, I have only begun a ‘balkanising’, distributive process that must go on and do justice to all the other excellent artists who worked in Bellini’s shop and whose artistic identity has been so long subsumed under his name.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Venezia e il 'poema' pittorico di Italico Brass

Il ‘poema pittorico’ di Italico

Brass (Gorizia 1870-Venezia 1943) riemerge in una mostra

dedicata all’impressionista veneziano, che si aprirà il 29

settembre a Palazzo Loredan. Nome rimasto a lungo nel silenzio,

Brass è stato protagonista del panorama artistico internazionale

nei primi decenni del Novecento e nella fascinosa Venezia del

temp. La sua è una pittura in piena sintonia con una società…

View On WordPress

0 notes