#Pierre Dumayet

Text

“ Se dovessimo tener conto delle letture importanti che dobbiamo alla Scuola, ai Critici, a tutte le forme di pubblicità e, viceversa, di quelle che dobbiamo all'amico, all'amante, al compagno di scuola, vuoi anche alla famiglia - quando non mette i libri nello scaffale dell'educazione - il risultato sarebbe chiaro: quel che abbiamo letto di più bello lo dobbiamo quasi sempre a una persona cara. Ed è a una persona cara che subito ne parleremo. Forse proprio perché la peculiarità del sentimento, come del desiderio di leggere, è il fatto di preferire. Amare vuol dire, in ultima analisi, far dono delle nostre preferenze a coloro che preferiamo. E queste preferenze condivise popolano l'invisibile cittadella della nostra libertà. Noi siamo abitati da libri e da amici.

Quando una persona cara ci dà un libro da leggere, la prima cosa che facciamo è cercarla fra le righe, cercare i suoi gusti, i motivi che l'hanno spinta a piazzarci quel libro in mano, i segni di una fraternità. Poi il testo ci prende e dimentichiamo chi in esso ci ha immersi: tutta la forza di un'opera consiste proprio nel saper spazzar via anche questa contingenza!

Eppure, con il passare degli anni, accade che l'evocazione del testo faccia tornare alla mente il ricordo dell'altro: alcuni titoli sono allora di nuovo dei volti.

E, siamo giusti, non sempre il volto di una persona amata, ma anche quello (oh! raramente) del tal critico o del tal professore.

È il caso di Pierre Dumayet, del suo sguardo, della sua voce, dei suoi silenzi, che nelle Letture per tutti della mia infanzia dicevano tutto il suo rispetto per il lettore che grazie a lui sarei diventato. E il caso di quel professore la cui passione per i libri sapeva dotarlo di un'infinita pazienza e regalarci perfino l'illusione dell'amore. Doveva proprio preferirci - o stimarci - noialtri allievi, per darci da leggere quel che gli era più caro. “

Daniel Pennac, Come un romanzo, traduzione di Yasmina Mélaouah, Feltrinelli (collana Idee), 1998²⁶, pp. 70-71. (Corsivi dell’autore)

[1ª edizione originale: Comme un roman, éditions Gallimard, 1992]

#Daniel Pennac#leggere#letture#citazioni#saggistica#libri#Come un romanzo#scuola#pubblicità#amicizia#educazione#critica letteraria#amici#famiglia#amanti#preferire#amare#letteratura francese contemporanea#preferenze#libertà#vita#Yasmina Mélaouah#anni '90#fraternità#professori#saggi#formazione culturale#cultura#Pierre Dumayet#silenzi

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

AVRIL 23

Yukio Mishima, Confessions d’un masque.

Geoffroy de Lagasnerie, 3. Une aspiration au dehors.

Léon Bloy, Histoires désobligeantes.

Jean Azarel, Vous direz que je suis tombé. Vies et morts de Jack-Alain Léger.

Claire Marin, Être à sa place. Habiter sa vie, habiter son corps.

Marion Muller-Colard, Bouche cousue.

Mariette Navarro, Alors Carcasse.

Annie Saumont, Noir, comme d’habitude.

Lydie Salvayre, Famille.

Séverine Chevalier, Chronique judiciaire.

Pierre Dumayet, Autobiographie d’un lecteur.

0 notes

Quote

J'ai horreur des débats. Si le format télé pouvait réellement ruiner les débats, quel soulagement ! A la télé, l'obsession du débat est une histoire qui a une vingtaine d'années, pas plus. Depuis Giscard, depuis 1974, rien n'est digne d'être montré à la télévision si ça ne ressemble pas à un match de foot. Il faut qu'il y ait un ballon. Le ballon politique, par exemple, c'est ce qu'on appelle la vérité. Alors il faut qu'on nous les montre tous ensemble en train de se faucher le ballon... Si on veut parler de Proust, il faudrait encore qu'il y ait un débat ? Proust en ballon de foot ? Et puis, quand on a bien débattu, on jette tout par dessus bord ? Non, les débats devraient être enregistrés pour être diffusés cinquante ans plus tard. Là, ça pourrait avoir un certain intérêt. Mais si tu me dis que le formatage télé ruine vraiment le débat, tant mieux, ça s'arrose !

(Pierre Dumayet, Pierre-Marc de Biasi, entretien) (Les cahiers de médiologie 1, 1996)

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

“I think that in literature we can see the human perspective in its entirety, because literature doesn’t let us, doesn’t permit us to live without seeing human nature under its most violent aspect. You only have to think of the tragedies, Shakespeare, there are lot of examples of the same genre. And, finally, it’s literature that makes it possible for us to perceive the worst and learn how to confront it, how to overcome it. In short, a man who plays finds in the game the force to overcome what the game contains of horror.“

TV interview with Georges Bataille about his book Literature and Evil, 1985. Interviewer: Pierre Dumayet. Translator: Vidar Vikingsson.

542 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bonjour!

Bonjour et soyez les bienvenus à notre petit coin lecture! Cette année nous allons prendre le plaisir de lire, l'idée est de créer un espace de partage commun où chacun d'entre nous pourra s'exprimer en participant aux activités proposées. Bien que vous le soyez, je vous prie d'être toujours polis et respectueux avec vos camarades; ici le but c'est de faire des échanges pour nous enrichir mutuellement et pas de voir qui a raison! je vous invite donc à participer activement aux activités, ne soyez pas timides! Il ne faut pas non plus avoir peur de faire des erreurs orthographiques parce qu'elles font partie de notre apprentissage.

Je vous laisse une citation sur la lecture de Pierre Dumayet "Lire est le seul moyen de vivire plusieurs fois" ¿qu'est-ce que vous en pensez que Pierre Dumayet veut nous dire avec cette phrase?

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Lire est le seul moyen de vivre plusieurs fois. Pierre Dumayet (Beatrice Offor) #bibliobibuli #leitura #livros #leitores #frases #citações #pensamentos #books #reading #readers #libri #lettura #lettori #livres #lecteurs #lecture https://www.instagram.com/p/CgUKh-0LKnu/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

#bibliobibuli#leitura#livros#leitores#frases#citações#pensamentos#books#reading#readers#libri#lettura#lettori#livres#lecteurs#lecture

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Germán Alonso (*1984)

Song of L. H. N. & C. (2015)

for violin, cello & electronics

Camille Guilpain, violin

Esther Lefebvre, cello

Germán Alonso, electronics

Festival Archipel 2015

Théâtre Pitoëff, Geneva

"Et maintenant que l’homme est en train de disparaître, on nous pose la même question que l’on posait autrefois à ceux qui proclamaient que Dieu était mort.

On nous dit : si l’homme est mort, alors tout est possible, ou, plus exactement, tout est nécessaire.

Ce que découvrait la mort de Dieu, ce que découvrait cette grande absence de l’Être suprême, c’était l’espace de la liberté.

Ce que découvre maintenant la disparition de l’homme dans cette immense lacune laissée par l’homme maintenant effacé, ce qu’on voit surgir, c’est la trame d’une sorte de nécessité ; c’est le grand réseau de systèmes auquel nous appartenons. Et on nous dit alors : tout est nécessaire."

[Interview de Michel Foucault par Pierre Dumayet pour son livre “Les

Mots et Les Choses”]

11 notes

·

View notes

Quote

And I think that in literature we can see the human perspective in its entirety. Because literature doesn’t let us, doesn’t permit us to live without seeing human nature under its most violent aspect.

Georges Bataille interviewed by Pierre Dumayet in 1958

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

-- The only TV interview that exists with Georges Bataille (1958). About his book “Literature And Evil”. Interviewer: Pierre Dumayet.

89 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

“If Man is dead, everything is possible!” – an early interview with Michel Foucault

Roughly a decade before publishing his two most famous treatises on power – Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison (1975) and The History of Sexuality, Volume One (1976) – the French philosopher Michel Foucault rose to prominence with The Order of Things: An Archaeology of the Human Sciences (1966). Written as existentialism fell out of favour among French intellectuals, the ambitious work sought to define a new philosophical epoch in which knowledge could be best understood as arising from ‘large formal systems’ that change over time. In this 1966 interview with the French television broadcaster Pierre Dumayet, Foucault discusses ideas from The Order of Things, including why he believed that Jean-Paul Sartre’s emphasis on the individual made him ‘a man of the 19th century’, and why ‘the disappearance of Man’ presented an exciting opportunity for new moral and political systems to arise.

1 note

·

View note

Link

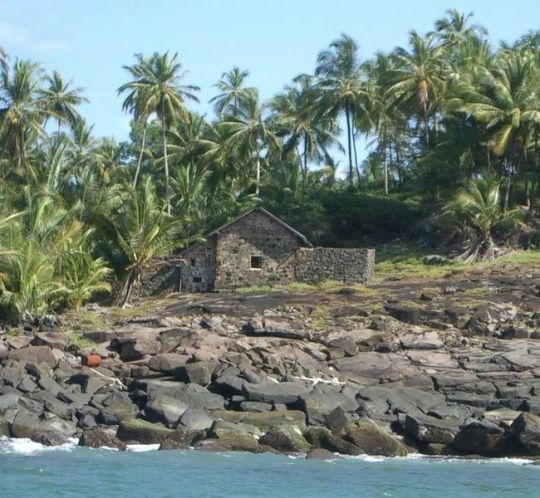

Il est très facile de trouver sur Internet un film extraordinaire qui s'appelle ReLectures pour tous . Robert Bober filme Pierre Dumayet en train de visionner d'anciens épisodes de l'émission. Jules Supervielle mime l'Homme de la pampa, Henry Miller raconte comment il s'est installé à Big Sur, François Mauriac prétend savoir pourquoi il n'écrit pas ses mémoires : «Parler de soi, c'est parler de tous les siens, qui n'ont rien demandé.» Roger Vailland, le communiste libertin, est invité six fois, un record que personne ne s'explique. Pierre Dumayet dit : «Je me sens un peu tout bête d'être tout seul à regarder ces images, parce qu'on devrait être au moins cinq. Il devrait y avoir Desgraupes, il devrait y avoir Nicole Vedrès, il devrait y avoir Max-Pol Fouchet, il devrait y avoir Jean Prat qui a réalisé pour la première fois Lectures pour tous, et je suis tout seul là… bête comme un vivant.»

De livre en livre, Robert Bober s'arrange toujours pour citer les premières phrases de la Ronde, le film de Max Ophüls, quand le meneur de jeu, sur son manège, dit : «Les hommes ne voient qu'un seul aspect des choses, moi je les vois tous, parce que je vois en rond et cela me permet d'être partout à la fois.» Cinq vers de Reverdy leur font écho dans Par instants, la vie n'est pas sûre : «Ils sont assis / La table est ronde / Et ma mémoire aussi / Je me souviens de tout le monde / Même de ceux qui sont partis.»

0 notes

Text

The story of the French producer Eliane Victor and her programme “Les femmes aussi”

Eliane Victor was born in 1918 in Paris. She became a French journalist and television pioneer, insofar as she produced numerous programmes devoted to women's lives. In 1958, she became secretary general of Cinq colonne à la une, where she worked with Pierre Lazareff, Pierre Dumayet, Pierre Desgraupes and Igor Barrère. She was then producer of Les femmes aussi, which was launched in 1964. This programme was broadcast for nine years on television and included sixty-five programmes. I propose today to look at her career, and particularly this extremely modern programme in several aspects.

The aim of this programme is to show what we didn’t show regularly, and particularly the story of forgotten women, who are not wanted to be seen, and who are not shown on television. Thus she uses television as an open medium, a window on the world, and tries to make viewers aware of the stories of single mothers, divorcees, widows, and women living in poverty. The later confide in the camera and talk about their hopes, regrets, fears, loves, friendships...

As a producer, she chooses her subjects, as she said in a magazine: "In general, it's my desires; I find the central idea for the programme. I work with a pool of directors. I submit my idea to the director I know will be best suited to it. But sometimes a director will come to me with an idea. The opening is a two-way street.” However, Eliane Victor was repeatedly censored in the 1960s and 1970s. She recounts that she was forbidden to deal with three subjects: female homosexuality, abortion and contraception.

The programme was a great success when it was first broadcast in the afternoon, as it was aimed more at women at home. I invite you to watch this programme available on the INA's platform, called “Madelen”. Also, don't hesitate to read her books, rich in anecdotes and stories related to French television from the 1960s to the 1980s.

[1] Eliane Victor, Les femmes… aussi, Paris, Essais, Mercure de France, 1973, p. 9-10.

0 notes

Text

Interviewer: Could you name one or two writers that felt guilty of writing, who thought they were criminals because they were writers?

Bataille: There are two that I wrote about in my book that are exemplary in that regard. They are Baudelaire and Kafka. Both of them knew that they were on the side of evil. And, consequently, that they were guilty. With Baudelaire it’s clear by the fact that he chose the title “Flowers of Evil” for his most intimate writings, and with Kafka it’s even more clear. He thought that when writing he went against the wishes of his family and therefore he put himself in a guilty position. It’s a fact that his family let him know that it was evil to spend his life writing, that the right thing to do in life was to devote himself to commercial activities, and if you did something else, you were doing something evil.

TV interview with Georges Bataille about his book Literature and Evil, 1985. Interviewer: Pierre Dumayet. Translator: Vidar Vikingsson.

243 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

Abonnez-vous http://bit.ly/inaculture Lecture Pour Tous | RTF | 03/06/1959 Nicole Védrès et Pierre Dumayet présentent "Cent ans de souvenirs ou presque" de Raoul Gunsbourg. Dans ce livre, l'auteur, qui a connu beaucoup de monde, livre des anecdotes sur Wagner, Tolstoï, Sarah Berhardt.... ****** info sur les commentaires ****** Sur les chaînes YouTube, vous êtes libre de donner votre opinion, fût-elle critique. Pour assurer la qualité du débat, nous vous demandons toutefois de toujours rester calme, poli et respectueux des autres commentateurs. Le prosélytisme, les propos grossiers, agressifs, irrévérencieux envers une personne ou un groupe de personnes sont proscrits. Tout commentaire insultant ou diffamant sera supprimé. Nous nous réservons le droit de bannir tout utilisateur qui ne respecterait pas les règles de la communauté. ******************************************************************* Images d'archive INA Institut National de l'Audiovisuel http://www.ina.fr #ina #archive #lecture

0 notes

Photo

“Lire est le seul moyen de vivre plusieurs fois.” Pierre Dumayet (Charles Courtney Curran) #bibliobibuli #leitura #livros #leitores #frases #citações #pensamentos https://www.instagram.com/p/CcctW2cOdO3/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

0 notes

Photo

Joseph Schildkraut mit der Opernsängerin Maria Olszewska, 1932

Joseph Schildkraut erhielt für seine Darstellung von Alfred Dreyfus einen Oscar als Bester Nebendarsteller.

Joseph Schildkraut (* 22. März 1896 in Wien, Österreich; † 21. Jänner 1964 in New York, USA) war ein österreichisch-US-amerikanischer Film- und Theaterschauspieler. Er gewann 1937 den Oscar als Bester Nebendarsteller für seinen Auftritt als Alfred Dreyfus in Das Leben des Emile Zola.

Maria Olszewska, auch Maria Olczewska (* 12. August 1892 in Ludwigsschwaige; † 17. Mai 1969 in Klagenfurt) war eine deutsche Opernsängerin (Alt/Mezzosopran).

Leben

Die Künstlerin wurde am 12. August 1892 in Ludwigsschwaige, einer Einöde zwischen Wertingen und Donauwörth (Pfaffenhofener Flur) als Marie Berchtenbreiter geboren. Schon früh zeigte sich ihre musikalische Begabung, die von den Eltern gefördert wurde. Sie studierte Gesang im Privatstudium bei Karl Erler in München. Anschließend betätigte sie sich als Konzert- und Operettensängerin. Der Dirigent Artur Nikisch riet der jungen Frau, sich der Oper zu widmen, und vermittelte ihr ein Engagement am Stadttheater in Krefeld. Dort debütierte die Sängerin als Page in Richard Wagners Tannhäuser. Hierauf war sie kurze Zeit am Stadttheater in Leipzig engagiert, wo sie Wagner-Rollen sang. Sie sang dort u. a. die Brangäne, Fricka, Erda und Waltraude. 1920 ging Maria Olszewska an die Staatsoper Hamburg, an der sie bis 1923 blieb. Hier sang sie u. a. die Carmen in der gleichnamigen Oper, die Mutter des jungen Bauern Turiddu in der Cavalleria rusticana und die Brigitte in der Uraufführung der Oper Die tote Stadt.

Von 1924 bis 1930 wirkte die Künstlerin an der Staatsoper in Wien. Dort begeisterte sie das Publikum als schönster und elegantester Rosenkavalier (Ludwig 2000, S. 212). In Wien gehörte sie, wie Robert Stolz und seine Frau Einzi in einem Interview sagten, zu den Superstars. Genannte berichteten weiter über die Sängerin:

Sogar ihre zahlreichen Fehden sorgten für Schlagzeilen... Vielleicht die berüchtigste dieser Szenen trug sich während einer Wiener Vorstellung der 'Walküre' in den zwanziger Jahren zu: Mizzi (=Maria Jeritza) sang die Sieglinde und brachte die Fricka, Maria Olszewska, derart in Rage, dass diese tatsächlich auf sie spuckte (Stolz 1986, S. 122).

Zusätzlich zu ihrem festen Engagement in Wien hatte sie weitere Verpflichtungen an der Städtischen Oper Berlin und an der Bayerischen Staatsoper in München. Für ihre langjährige Mitarbeit an den Münchener Festspielen erhielt die Künstlerin den Titel einer bayerischen Kammersängerin verliehen.

Anfang 1930 unternahm Maria Olszewska eine Gastspielreise durch die USA, die von Chicago aus, wo sie bis zum Spielzeitende gesungen hatte, begann. Die Tournee führte die Künstlerin und das hierfür verpflichtete Ensemble durch alle großen Städte des Landes: Philadelphia, Pittsburg, Louisville, Memphis, Dallas, Tulsa, San Antonio, El Paso, Los Angeles, San Francisco, Seattle und Portland. Dabei begeisterte insbesondere der Rosenkavalier, mit Maria Olszewska als Octavian, das amerikanische Publikum.

Maria Olszewska gastierte auf den großen Opernbühnen dieser Welt. Sie sang in Spanien, in der Schweiz, in Belgien und Italien, in den USA, wo sie 1933 als Brangäne auf der Bühne der Metropolitan Oper in New York debütierte, in Argentinien etc. In Paris und London sang sie 1930 und 1935 in München den Prinzen Orlofsky in der Operette Die Fledermaus. Neben den Partien in Richard Wagners Musikdramen zählten die Klytämestra in Elektra, die Amneris in Aida, die Ulrica in Ein Maskenball, die Dalila in Samson und Dalila, die Frau Fluth in Die lustigen Weiber von Windsor und der Octavian in Der Rosenkavalier zu ihren Glanzrollen.

Die Künstlerin wirkte auch in mehreren Filmen mit. Zu Ihren Filmpartner und -partnerinnen gehörten u. a.: Irene von Meyendorff, die blutjunge Maria Schell, Oskar Sima, Otto Tressler und Attila Hörbiger.

Von 1947 bis 1949 unterrichtete Maria Olszewska als Professorin für Gesang an der Akademie für Musik in Wien und wurde 1948 Lektorin an der Staatsoper Wien. Von 1951 bis 1955 trat sie an der Wiener Volksoper auf. Dort spielte sie u. a. in Operetten von Johann Strauß wie Eine Nacht in Venedig, Der Zigeunerbaron und Wiener Blut.

Die Künstlerin heiratete 1925 den Heldenbariton Emil Schipper (1882–1957). Die Ehe wurde bald geschieden.

Ihre letzte Ruhe fand sie im Park von Schloss Rottenstein in Kärnten, Österreich.

Alfred Dreyfus (9. Oktober 1859 in Mülhausen – 12. Juli 1935 in Paris) war ein französischer Offizier. Seine ungerechtfertigte Verurteilung wegen Landesverrats löste 1894 die Dreyfus-Affäre aus, die Frankreich innenpolitisch zutiefst erschütterte.

Dreyfus starb 1935 in Paris an einem Herzinfarkt. Er wurde auf dem Friedhof Montparnasse in Paris beigesetzt.

Seine Enkelin Madeleine Levy wurde später während des Zweiten Weltkriegs als Jüdin nach Auschwitz deportiert und dort ermordet. Seine Ehefrau Lucie überlebte den Holocaust und starb kurz nach der Befreiung in Paris.

Theodor Herzl, der 1895 als Korrespondent der Neuen Freien Presse Dreyfus’ Degradierung miterlebt hatte, schrieb unter dem Eindruck des Prozesses sein Buch Der Judenstaat. Das Werk erschien am 14. Februar 1896, noch bevor vom 29. bis 31. August 1896 der erste Zionistenkongress in Basel stattfand.

Nach dem Zweiten Weltkrieg wurde Dreyfus nach und nach zu einer Art Ikone der Republik stilisiert. Seit 1988 hat er ein Denkmal im Jardin des Tuileries. An seinem Wohnhaus ist eine Gedenkplakette angebracht. Auch in Berlin befindet sich eine Gedenktafel in der Blücher-Kaserne in Kladow.

Am 12. Juli 2006, dem 100. Jahrestag seiner Rehabilitierung, fand eine Gedenkzeremonie in der Pariser Militärschule statt, bei der Staatspräsident Jacques Chirac als Hauptredner auftrat und in Begleitung des Premierministers und vierer weiterer Minister Dreyfus „die feierliche Huldigung der Nation“ (frz. l’hommage solennel de la Nation) darbrachte.

Zu der verschiedentlich vorgeschlagenen Überführung von Dreyfus’ sterblichen Überresten in das Panthéon kam es bisher nicht.

Dreyfus in Literatur und Film

Bereits 1913 griff Roger Martin du Gard, der spätere Literaturnobelpreisträger von 1937, die Dreyfus-Affäre auf. In seinem Roman Jean Barois beschreibt er u. a., wie Dreyfus seine Sympathisanten während des zweiten Prozesses durch seine „unheroische“ Apathie enttäuschte. In Deutschland verarbeitete Rolf Schneider den Fall in seinem Roman Süß und Dreyfus von 1991. Der Israelische Dichter Joshua Sobol schrieb 2008 das Theaterstück "Am Not Dreyfus, Or-Am [Ani Lo Dreyfus]. Der britische Schriftsteller Robert Harris schilderte die Affäre in seinen 2013 erschienenen Roman An Officer and Spy (deutscher Titel: Intrige) aus der Sicht des Geheimdienstoffiziers Picquart.

Die Dreyfus-Affäre lieferte auch die Vorlage für zahlreiche Verfilmungen, u. a.:

1930: Dreyfus – Regie: Richard Oswald

1991: Der Gefangene der Teufelsinsel (Prisoners of Honor) – Regie: Ken Russell

1994: Affäre Dreyfus (L’affaire Dreyfus) – Regie: Yves Boisset – zweiteilige Fernseh-Dramatisierung

1998: J’accuse – Ich klage an (J’accuse) – Regie: Robert Bober, Pierre Dumayet

2019: Intrige (J'accuse) – Regie: Roman Polanski, nach dem Roman von Robert Harris

Im Jahr 1937 entstand unter der Regie von Wilhelm Dieterle zudem die Filmbiografie The Life of Emile Zola mit Paul Muni in der Titelrolle. In ihr nimmt die Affäre breiten Raum ein, allerdings klammert der Film deren antisemitische Aspekte weitgehend aus.

0 notes