#Place de St. André des Arts

Text

ALEXANDRA STRÉLISKI

"UMBRA"

Hoy, XXIM Records/Sony Masterworks se complace en anunciar el lanzamiento de otro nuevo sencillo, 'Umbra', así como la versión ampliada de Néo-Romance, el disco aclamado por la crítica de la pianista francocanadiense y compositora ALEXANDRA STRÉLISKI.

Mira el vídeo AQUÍ

Consigue la versión ampliada del álbum AQUÍ

La pieza inédita viene acompañada de un videoclip rodado por Nick Helderman en La Marbrerie de Montreuil, Francia, con Julia Kotarba, Natalia Kotarba y Maxime Navert, miembros de la banda de gira de STRÉLISKI.

"Umbra" fue la última pieza que compuso para el proyecto y se terminó cuando ya se había grabado la mayor parte de Néo-Romance. "Umbra" hace referencia a la parte más oscura de la sombra, pero esta pieza se creó para intentar poner algo de luz en ella", dice STRÉLISKI. Convertida en el cierre habitual de sus conciertos, la pieza es ahora una de las favoritas de los fans, cosechando una calurosa acogida allá donde ha tocado.

"Es ahora una de mis piezas favoritas para tocar en directo", añade STRÉLISKI."Empezó siendo el final de mi espectáculo, con piano solo, y se convirtió en una celebración colectiva, basada en la improvisación. Me encanta interpretarla junto a mis maravillosas instrumentistas Julia y Natalia Kotarba, y con mi compañero de siempre Maxime Navert al sintetizador".

Un álbum centrado en la importancia del Romanticismo en el mundo moderno, y en lo que la relación de los románticos con la naturaleza puede enseñarnos en tiempos tan difíciles, Néo-Romance se ha convertido en un éxito comercial y de crítica. El disco alcanzó el nº 1 en la lista de álbumes de Québec -por delante de Taylor Swift- y ha sido nominado para el Premio Polaris de la Música 2023. STRÉLISKI estambién la artista femenina más nominada de este año en L'ADISQ - una ceremonia que recompensa la excelencia en la industria musical quebequense - con seis nominaciones en total.

Empezando con tres actuaciones en Múnich, Carouge y Zúrich, STRÉLISKI continuará su gira Néo-Romance con 30 nuevas fechas por Canadá, Estados Unidos y Europa durante el resto de 2023 y hasta 2024. A continuación, todas las fechas de la gira:

Ya se puede escuchar la versión ampliada de Néo-Romance aquí:

“NÉO-ROMANCE ON TOUR” 2023/2024:

2023

NOVIEMBRE

19/11 - MÚNICH (DE) - Milla

20/11 - CAROUGE (CH) - Le Chat Noir

21/11 - ZURICH (CH) - Kaufleuten

2024

ENERO

11/01 – QUÉBEC (CA) – Grand Théâtre de Québec

13/01 - TORONTO (CA) - Trinity-St. Paul's United Church and Centre for Faith, Justice and the Arts

17/01 - MONTRÉAL (CA) - Salle Wilfrid Pelletier de la Place des Arts

18/01 - MONTRÉAL (CA) - Salle Wilfrid Pelletier de la Place des Arts

FEBRERO

23/02 - BERLÍN (DE) - Colosseum

25/02 - HAMBURGO (DE) - Resonanzraum (Acoustic show)

26/02 – PARIS (FR) – Église Saint-Eustache

MARZO

05/03 - LONDRES (UK) - The Elgar Room Brasserie at the Royal Albert Hall

07/03 - EINDHOVEN (NL) - Muziekgebouw Eindhoven

08/03 - ROTTERDAM (NL) - LantarenVenster

27/03 - SHERBROOKE (CA) - Salle Maurice O’Bready

28/03 - SHERBROOKE (CA) - Salle Maurice O’Bready

30/03 - BROSSARD (CA) - Théâtre Manuvie

31/03 - BROSSARD (CA) - Théâtre Manuvie

ABRIL

01/04 - BROSSARD (CA) - Théâtre Manuvie

05/04 - L'ASSOMPTION (CA) - Théatre Hector-Charland

06/04 - L'ASSOMPTION (CA) - Théatre Hector-Charland

13/04 - SHAWINIGAN (CA) - Centre des Arts de Shawinigan

14/04 - SHAWINIGAN (CA) - Centre des Arts de Shawinigan

18/04 - SAINTE-THÉRÈSE (CA) - Théatre Lionel-Groulx

19/04 - SAINTE-THÉRÈSE (CA) - Théatre Lionel-Groulx

20/04 - TERREBONNE (CA) - Théatre du Vieux-Terrebonne

21/04 - TERREBONNE (CA) - Théatre du Vieux-Terrebonne

26/04 - LAVAL (CA) - Salle André-Mathieu

27/04 - LAVAL (CA) - Salle André-Mathieu

MAYO

02/05 - VANCOUVER (CA) - St. James Community Square

07/05 – SEATTLE (USA) – Fremont Abbey Arts Center

08/05 – SAN FRANCISCO (USA) – The Chapel

11/05 – CHICAGO (USA) - Constellation

12/05 – NEW YORK (USA) – Le Poisson Rouge

24/05 - SALABERRY-DE-VALLEYFIELD (CA) - Valspec - Salle Albert-Dumouchel

25/05 - SALABERRY-DE-VALLEYFIELD (CA) - Valspec - Salle Albert-Dumouchel

27/05 - GATINEAU (CA) - Salle Odyssée

28/05 - GATINEAU (CA) - Salle Odyssée

30/05 - AMOS (CA) - Théâtre des Eskers

JUNIO

12/06 - SAINT-JEAN-SUR-RICHELIEU (CA) - Théâtre des Deux Rives

13/06 - SAINT-JEAN-SUR-RICHELIEU (CA) - Théâtre des Deux Rives

SEPTIEMBRE

12/09 - SAINT-HYACINTHE (CA) - Centre des arts Juliette-Lassonde

13/09 - SAINT-HYACINTHE (CA) – Centre des arts Juliette-Lassonde

SIGUE A ALEXANDRA STRÉLISKI

Página web: alexandrastreliski.com

Facebook: @alexstreliski

Instagram: @alexstreliski

Twitter: @alexstreliski

TikTok: @alexstreliski

YouTube: @alexstreliski

0 notes

Text

Letreros, anuncios, avisos, rótulos ...

En la Place St. André des Arts (al lado de la Isla de la Cité), para ver esta maravilla hecha con cacerolas de cobre.

#Letreros anuncios avisos rótulos ...#¿Esta es la imagen y algunos datos (O no) la “Historia” la pones tú? ¡La tuya! ¿Lo harás...?

0 notes

Photo

I’m rereading a favorite book about Paris “Parisians”by Graham Robb. There’s a chapter called Marville. This begins by talking about this photographer but ends leaving you feeling very nostalgic about what changes have happened and will happen through time in Paris. This is the Place St. André des Arts where the chapter begins. The square was built around 1800 after the destruction of the church that stood here and was sold and demolished during the French Revolution. Some houses would be demolished in 1898 in favor of the construction of the rue Danton. More demolition was intended but the somewhat quirky architecture remains as testimony to the architecture before the restructuring of Paris in the 19th century. The second old photo goes back to Charles Marville (1813-1879), a successful, innovative French photographer of the 19th century. Today he is best known for his photos of the old quarters in central Paris. He was commissioned by the government of Napoleon III to document the city before the radical transformations by the prefect Haussmann. When I finished the chapter I had to run out myself to photograph the square. . . . #paris #marville #parisjetaime #parislife #parisart #parismonamour #parismaville #parislove #pariscity #villedeparis #iloveparis #parisfind (at Place Saint-André-des-Arts) https://www.instagram.com/p/CXs3sQttAis/?utm_medium=tumblr

#paris#marville#parisjetaime#parislife#parisart#parismonamour#parismaville#parislove#pariscity#villedeparis#iloveparis#parisfind

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Place St André des Arts, Paris, 1898 (photogravure) Photographer: Eugène Atget, Paris

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

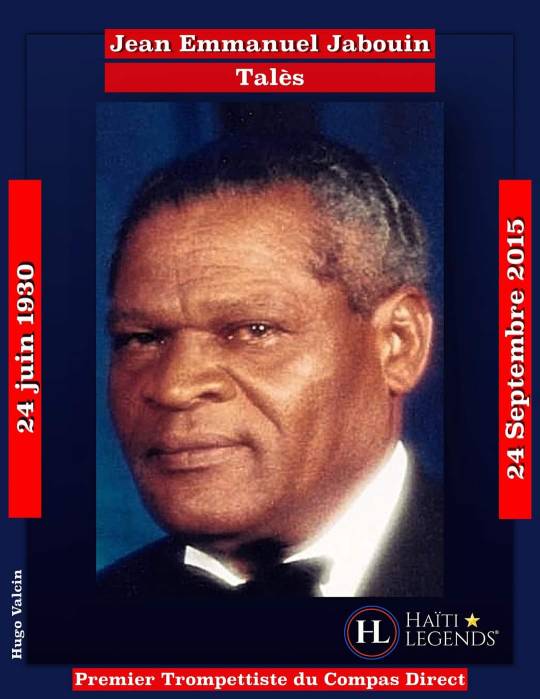

Haïti Legends ''Sa Nou Dwe Konnen''

Jean Emmanuel Jabouin '' Premier Trompettiste du Compas Direct''

Biographie

Louis Carl St-Jean.

De son vrai nom Jean Emmanuel Jabouin, Talès a vu le jour à la Croix-des Bouquets le 24 juin 1930. Il est le fils du Cayen Emmanuel Jabouin, ancien fonctionnaire de l’administration publique, et d’Indiana Victor, originaire de la Croix-des-Bouquets. À l’âge de 3 ans, Talès est frappé par la fièvre typhoïde, qui le laisse avec une légère paralysie des jambes. Peu après sa guérison (vers quatre ou cinq ans), il commence à manifester un intérêt pour la musique. Non sans rire, il raconte: « Je prenais plaisir à m’asseoir sur la « manoumba » lorsque les troubadours qui venaient se produire presque toutes les fins de semaine dans la cour de la maison de mes parents prenaient leur pause… Ces exécutants eux-mêmes prenaient plaisir à me regarder pincer les lames de cet instrument qui était plus grand que moi. »

En 1937, la mère de Talès déménage et s’installe avec son fils à la rue du Champ-de-Mars, presque au coin de la rue de l’Enterrement, au cœur du Morne-à-Tuf. La maison voisine est celle des époux Augustin Baron où se produit souvent le légendaire pianiste et musicien François Alexis Guignard (dit Père Guignard). En cours de semaine, il fabrique, avec des tiges de papaye, des saxophones qu’il joue, assure-t-il, avec la plus grande joie pour les voisins. En octobre 1941, Talès est admis à l’Ecole Centrale des Arts et Métiers où il apprend la musique et la trompette sous la direction du maestro Augustin Bruno.

En juillet 1947, Talès, frais émoulu de la Centrale, fait ses débuts avec l’Ensemble Anilus Cadet, dont le QG se trouve à la rue de l’Enterrement, en face de l’Hospice Saint François de Sales. Il joue alors à côté de Fritz Ferrier, d’Issalem « Sonson » Bastien et d’autres exécutants qu’Anilus recrutait au besoin. En septembre 1949, Talès occupe l’un des dix pupitres du Jazz des Caraïbes. C’est cet orchestre, monté par Issa El Saieh, qui, en février 1950, accompagne Daniel Santos, Estela « Tete » Martinez et d’autres stars latinoaméricaines de passage au « Simbie Night Club », au « Vodou Night Club » et dans d’autres boîtes de nuit port-au-princiennes. Nous tenons de lui cette confidence pour le moins étonnante: « C’est au sein de l’Orchestre des Caraïbes que je peux retracer mes meilleurs souvenirs sur la scène musicale… » Après la dislocation de ce dixtuor, Talès s’associe de nouveau au groupe d’Anilus Cadet, qui obtient le deuxième prix du carnaval de 1951 pour la méringue « Bèl carnaval ». (Le premier prix a été décerné à TI-TA-TO.)

À la même époque, Talès, Emmanuel Duroseau fils (piano), Montfort Jean-Baptiste (contrebasse), Louis Denis (batterie) et Marcel Jean (tambour) vont prêter leurs talents à Guy Durosier, qui, sur la recommandation d’Issa El Saieh, dirige l’Ensemble Tabou, le sextette de l’Hôtel Rivoli (Pétionville). Au cours de la même période, Talès accompagne dans les quatre coins du pays le troubadour Nicolas « Candio » Duverseau, grand chantre du magloirisme. Il joue aussi dans d’autres groupements d’occasion qui animent des pique-niques dominicaux et des soirées dansantes organisées le plus souvent par Stanislas Henry et Antoine Dextra à Carrefour Marin, commune de la Croix des Bouquets.

À la fin de 1951, Talès adhère à l’Orchestre Atomique Junior, monté par Nemours Jean-Baptiste après sa séparation de l’Orchestre Atomique. Au cours de l’année 1952, le groupe de Nemours est dissous. Immédiatement le bouillant maestro est appelé à diriger l’Orchestre Citadelle. Lorsqu’Hector Lominy se sépare de cet orchestre, Talès y est engagé pour seconder Jean Moïse. Véritable bûcheur, Nemours met sur pied parallèlement un petit groupement pour « faire la côte », selon l’expression de l’époque. Avec Dérico (chanteur), Webert Sicot (saxophone alto), Gérard Dupervil (trompette), son frère Montfort Jean-Baptiste ou parfois Augustin Fontaine (contrebasse), Hilaire ou parfois « Bibiche » (batterie) et d’autres musiciens, il sillonne par monts et par vaux les coins et recoins de la République, spécialement pour animer des fêtes champêtres.

En novembre 1953, Talès prend le chemin du Casino International et s’associe au Conjunto Panamerican dirigé par le trompettiste Emile D. Dugué. Il évolue alors aux côtés d’Ulysse Cabral (chanteur), Julien Paul (contrebasse), Charles Dessalines (saxophone alto), Gabriel Dasque (tambour), etc. Environ six mois plus tard, Talès s’écarte de ce groupe pour aller remplacer Kesnel Hall dans l’Orchestre Atomique, placé alors sous la baguette du pianiste Robert Camille. Il y passe moins de six mois et regagne l’Orchestre Citadelle pour succéder à Gesner Domingue.

Vers la fin de 1954, Nemours Jean-Baptiste, toujours maestro de l’Orchestre Citadelle, fonde le Conjunto International. Pour l’aider à égayer les clients des restaurants dansants de Jean Lumarque, dont l’un à Kenscoff, l’autre à Carrefour, il invite plusieurs musiciens, dont Talès à la trompette, à participer dans cette merveilleuse aventure : Dérico (chanteur), Mozart Duroseau (accordéon), Montfort Jean-Baptiste (contrebasse), Webert Sicot (saxophone alto), parfois Gary Labidou (saxophone alto) et Kreutzer Duroseau (tambour). Le 22 mars 1955, après les travaux d’agrandissement et d’aménagement du night club « Aux Calebasses » à Carrefour, « Le Conjunto » devient officiellement « Ensemble Aux Calebasses ». Il convient de rappeler que la date du 26 juillet 1955 a été symboliquement retenue comme celle de la fondation de la formation musicale de Nemours Jean-Baptiste, ancêtre, donc, du compas direct. Talès en sera le premier et unique trompettiste jusqu’à l’arrivée de Walter Tadal en 1956.

Lorsque, en septembre 1958, Nemours quitte « Aux Calebasses » pour aller se produire au « Palladium Night Club », de Sénatus Lafleur, il baptise son groupe de son nom: Super Ensemble Nemours Jean-Baptiste. « Alors, affirme Talès, prendra naissance le compas direct », genre musical dont il a été l’un des grands artisans, de concert avec Walter Tadal, Raymond Gaspard, Julien Paul, Louis Lahens, André Boston et de bien d’autres musiciens. Là-dessus, il sied d’entendre la voix de Talès pour mieux nous renseigner: « Quand on parle de compas direct, il faut avouer que Kreutzer Duroseau a été le véritable catalyseur de ce mouvement … Richard Duroseau représente l’âme même du compas direct… » (Entrevue avec Louis Carl Saint Jean, 22 octobre 2005.)

Le 5 juillet 1964, le Super Ensemble Nemours Jean-Baptiste entame une tournée aux Etats-Unis. Le 22 septembre, date du retour du groupe en Haïti, notre trompettiste, en parfait accord avec Nemours, fait ses adieux au compas direct. Il est remplacé par le brillant trompettiste jérémien Emilio Gay. Dès le début de l’année 1965, Talès entame sa carrière aux Etats-Unis. Sur la recommandation de l’excellent saxophoniste Charles Dessalines, il intègre « Los Ases del Sesenta » qui jouent à Broadway Cafe, Myrtle Avenue, Brooklyn. Il y restera jusqu’en mars – avril 1977. Moins d’un mois plus tard, il entre au Conjuto du chanteur cubain Monguito Guillan (dit « El Unico ») où évolue également le contrebassiste Fritz Grand-Pierre. Par la suite, Talès et Raymond Marcel jouent tantôt avec ''Enrique Rosa y La Sabrosa'' tantôt avec Johnny Dupre y su Orquesta Internacional. En 1980, Talès met fin à sa carrière musicale après avoir passé deux merveilleuses années au sein du groupe du chanteur dominicain Rafael Batista.

À part d’avoir été un talentueux trompettiste, Talès a également été un analyste fin et lucide de la question musicale haïtienne. S’il reconnaît en Nemours Jean-Baptiste « un maestro extraordinaire et un grand visionnaire », ses musiciens préférés ont toujours été : Antalcidas O. Murat, Guy Durosier, Murat Pierre, Michel Desgrottes, Raoul Guillaume, Richard Duroseau et Webert Sicot. D’ailleurs, comme Nemours Jean-Baptiste lui-même, Talès a toujours vu en Antalcidas Murat « un maître ». En outre, il n’a jamais passé par quatre chemins pour affirmer : « Je suis Haïtien avant d’être musicien […] C’était un honneur pour moi d’avoir joué dans le groupe de Nemours pendant près de quinze ans. Cependant, je dois avouer que le Jazz des Jeunes était, de loin, le plus grand ensemble musical du pays… C’est le Jazz des Jeunes qui jouait la vraie musique du pays... » (Entrevue avec LCSJ, 25 octobre 2005). Hubert François, Jean Moïse, Alphonse Simon, Raymond Sicot et André Déjean ont été ses idoles parmi nos trompettistes.

Si Talès était connu comme un très bon musicien, il jouissait aussi de la réputation d’un excellent père de famille. Tandis qu’il menait sa carrière de musicien, il a travaillé comme barbier pendant plus de deux décennies dans un salon de coiffure situé à Sterling Place, à Brooklyn. Il a ainsi assuré l’éducation de quatre merveilleux enfants que lui a donnés sa femme Denise Frédéric Jabouin qu’il a épousé en 1953: Reynald Jabouin, docteur en médecine (décédé à New York en janvier 2015); Patrick Jabouin, agent immobilier et docteur en Théologie; Fanya Jabouin Monnay, docteur en thérapie conjugale et familiale et Jean Emmanuel Jabouin, Jr., MBA en Marketing.

Après avoir parcouru sans naufrage notre espace immense, Talès se repose de ses œuvres merveilleuses depuis le 3 octobre 2015 au Forest Lawn Cemetery, à Fort Lauderdale, en Floride. Pour son émule Raymond Marcel: « Talès repésentait le modèle de l’ami fidèle... La sonorité suave de son jeu avait fait de lui l’un de nos meilleurs trompettistes. » De son côté, son ancien camarade Serge Simpson, deuxième accordéoniste et premier et unique vibraphoniste du Super Ensemble Nemours Jean-Baptiste, a salué en lui: « Un homme d’un comportement exemplaire. Le jeu de Talès à la trompette, poursuit Simpson, reflétait deux qualités rarement réunis chez une seule personne: la discipline et la bonne humeur. J'ai toujours gardé un grand respect pour ce musicien... » Puisse le nom de Jean Emmanuel Jabouin rester gravé à jamais dans la mémoire de tous ceux qui ont aimé la musique haïtienne en général, le compas direct en particulier. Ce n’est qu’un au revoir, Talès! Ce n’est qu’un au revoir!

Auteur:

Louis Carl Saint Jean

4 octobre 2015

#JeanEmmanuelJabouin

#Talès

#TompettisteCompasDirect

#Biographie

#LouisCarlStJean

#HugoValcin

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

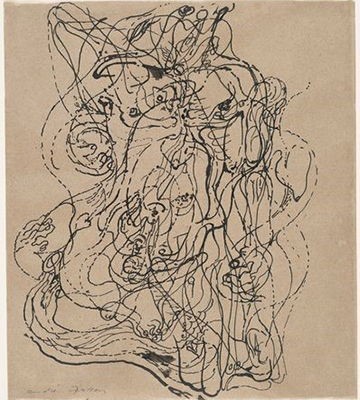

ANDRE MASSON

Andre Masson, Automatic Drawing, 1924

https://www.moma.org/collection/works/38201?artist_id=3821&page=1&sov_referrer=artist

Andre Masson, In the Tower of Sleep, 1938

https://art5308.files.wordpress.com/2016/11/magritte-book.pdf

Andre Masson, The Metamorphosis of the Lovers, 1938

https://robdigitalimage.wordpress.com/2015/06/11/concepts/

Andre Masson, The Metamorphosis of the Lovers, 1938

https://utopiadystopiawwi.wordpress.com/surrealism/andre-masson/gradiva/masson-gradiva-1939/

Childhood

André-Aimé-René Masson was born on January 4, 1896, in the small town of Balagny (Oise), north of Paris. He was the eldest of three children in a family of modest means. Growing up in the country, he felt a former connection with nature and the world.

Masson's childhood encouraged unconventional thought. In particular, his mother was a French teacher who promoted unusual texts that would later become important to the Surrealists and were considered scandalous. While his father was more conservative in his beliefs, he did not interfere with Masson's artistic ambitions.

Early Training and Work

Through the efforts of his mother and the quality of his drawings, Masson was admitted to the Brussels Académie des Beaux-Arts at age eleven, which was much younger than usual. He studied under the Belgian painter and sculptor Constant Montald, whose method of mixing glue with water and pigment proved very influential for Masson's later technique. He also took a side job making embroidery designs, which meant his days were filled with study and work.

In his limited free time, Masson read insatiably. He was fascinated by the Quattrocento and the work of the Renaissance masters, along with fin-de-siècle artists like Paul Gauguin, Vincent van Gogh, and Paul Cézanne. He saw a continuum between the two, remarking when he first James Ensor's Christ in the Midst of the Storm, that "contemporary painting could be as extraordinary as the old masters!"

His interests continued to include the modern (he was shocked by Cubism when he first encountered the works of Picasso and Braque) and the traditional (he traveled to northern Italy in 1914 to study fresco painting). Masson also traveled to Switzerland and became fascinated with the philosophical writings of Frederich Nietzsche, which profoundly affected his personal life.

He returned to Paris in 1915 and joined the French army, enduring the violence, trauma and death of World War I trench warfare. He was discharged in 1917 after suffering a severe chest injury; he spent months recovering in military hospitals and spent time in a psychiatric facility. While the experience of being at war was not something Masson often explicitly spoke about, it was the root of the very violent imagery in his work and remained with him for his entire life. After his discharge, he met his wife, Odette Cabalé, and the two relocated to Paris.

Mature Period

In Paris, Masson began making pottery at a studio center for veterans with disabilities. He also took up work with the Journal Officiel. His work from these postwar years featured erotic, sometimes pornographic content that varied widely in style and technique. The founder of the Surrealist movement, André Breton, would later call this Masson's 'erotic period' and believed it to be key to understanding his entire oeuvre.

According to the writer Malcolm Haslam, Masson hosted regular gatherings in his Paris studio at 45 rue Blomet. Here, along with Antonin Artaud, Michel Leiris, Joan Miró, Georges Bataille, Jean Dubuffet, and Georges Malkine, the group experimented with altered states of consciousness, smoking hashish and opium added to wine and music, discussing writers central to the developing Surrealist movement: Nietzsche, Arthur Rimbaud, Comte de Lautréamont, and even the Marquis de Sade.

While vast and divergent in many ways, this group of works shared themes of deep uncertainty and humanity's coexistence with nothingness, ideas drawn from Nietzsche. This philosophy also featured themes of metamorphosis and argued for the changeable nature of organic existence, ideas that would become increasingly important to Masson's art.

In 1921, Masson met fellow artist Joan Miró through their mutual friend, Max Jacobs. Masson and Miró immediately began a friendship that would be influential to both of their careers. The group of artists often met at a studio on the rue Blomet that became a place of intellectual and artistic knowledge, discussion and exploration. Visitors included Ernest Hemingway, Gertrude Stein and the playwright Armand Salacrou, who were some of the first buyers of Masson's work.

In 1923, Masson was offered a contract by Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler, a notable art dealer. Although it was not (yet) highly paid, this opportunity allowed Masson to focus solely on his art career. The following years, which encompassed both the Dada movement and the birth of Surrealism, proved some of the most exciting and successful of Masson's career. His style was changeable, and he began to experiment with automatic methods of working, often incorporating motifs from ancient Greek and Roman mythology.

During the 1930s, Masson's work grew increasingly violent and disturbing. His 1930s series of slaughterhouse paintings, built on the art historical legacy of Chaim Soutine's Carcass of Beef (early 1920s) and Rembrandt's Slaughtered Ox (1655), but brought new brutality and sexual associations to the depictions of flesh and meat. It is speculated that this may have been due to his turbulent personal life at the time. Following a 1929 divorce, he met his second wife, Rose, broke with the Surrealist group and moved out of Paris to establish a more solitary life in St-Jean-de-Grasse. He then relocated to Spain, only returning to France in 1936 after witnessing atrocities in the years prior to the Spanish Civil War. Once back in France, he reconciled with Breton and the Surrealists.

In 1941, Masson and his family sought and secured political asylum in the United States, as did many of the Surrealists. Masson's time in America transformed and revitalized his work, introducing new variety in subject matter, style and motifs. He began to focus more on abstractions from nature, alongside his fascination with metamorphosis and cosmic unity. In 1943, Masson underwent his final split from Breton, however he continued to experiment with Surrealism as a style.

Late Period

At the end of World War II, Masson and his family were able to return to France in 1945. During a trip to the south of France, Masson became highly interested in southeastern Asian art and Taoism. His work became increasingly existential, conveying a sense of universal fusion through abstractions of natural landscapes. He remained based in Paris but traveled back and forth to a country house in Aix. In 1965, he was commissioned to paint the ceiling of the Odéon-Théâtre de France and although he was thrilled to complete the project; it proved to be taxing for the aging artist and it was his last major work. This large circular installation, featuring classical figures like Agamemnon and Shakespearean characters like Falstaff, was celebrated as a triumph. The actor Jean-Louis Barrault was said to have declared, "At last we have a sun over our heads." His later career included a series of landscape themes and non-objective paintings. Masson died at his home in Paris in 1987.

The Legacy of André Masson

Masson tackled many of the concepts central to Surrealism and established new ways of representing traditional themes trauma, angst, violence, sex, and death with modern imagery. The philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre credited him with "retracing a whole mythology of metamorphoses: (transforming) the domain of the mineral, the domain of the vegetable and the domain of the animal into the domain of the human."

Masson's work influenced numerous 20th-century artists, the most prolific being Jackson Pollock and Mark Rothko. Pollock's Action Painting in particular drew on Masson's experimental use of the automatic technique. Additionally, his use of block coloration and abstraction of form also strongly influenced other artists within the New York School. The practice of automatism has continued to resurface and remains an influence on contemporary art.

Masson's work was also of importance because of its eclectic and multifaceted nature. He experimented with different styles and techniques, so that although he is primarily associated with Surrealism, his work advanced perspectival elements found in Cubism and popularized the use of automatic methods of mark-making that channeled unconscious impulses into visual images. His long career included tremendous range, but featured deeply emotional transparency that allowed viewers to understand the emotional effects of war trauma.

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Place St. André des Arts, Paris 1948, Izis (1911 - 1900)

53 notes

·

View notes

Text

13 Coolest International Destinations You Can Visit Without a Passport

YOU DON'T NEED A STAMP TO EXPLORE THESE SURPRISING GETAWAYS.

When it involves traveling overseas, there's one essential thing you usually got to bring: a passport. But did you recognize that you simply can attend areas outside of the mainland us without a blue book? (And we're not talking Hawaii or Alaska!) From a tropical paradise in Central America to family-friendly islands across the Caribbean, there are a couple of secret places you'll visit without a passport—and we're here to inform you exactly the way to get there. So, read on, and determine where you'll skip the stamp on your next international vacation.

1 Montego Bay, Jamaica

Montego Bay is possibly the foremost popular tourist destination in Jamaica and a serious cruise liner port. Hit the "Hip Strip," formally referred to as Gloucester Avenue, for shops, art galleries, and colorful cafés. But, of course, you're in Jamaica, so do not forget the beach! Doctor's Cave Beach is that the hottest choice because of its turquoise water perfect for snorkeling. and every one these wonderful Jamaican attractions are often visited without a passport if you're traveling by water. If you're on a cruise that begins and ends within the states, all you would like maybe an occident Travel Initiative-approved document, sort of a certificate and government-issued ID, or an enhanced driver's license.

2 Cabo San Lucas, Mexico

Cabo San Lucas is found below the state of California, down on the southern tip of the Lower California peninsula in Mexico. This beautiful beach resort destination is understood as a favorite amongst the celebs for its proximity to Hollywood. you'll go there year-round and possibly see celebrities like George Clooney, Jennifer Aniston, or maybe Justin Bieber himself. Hit The Spa at Las Ventanas if you would like to urge a Jennifer Lopez-approved glow, and eat fresh at Flora Farms like Adam Levine. and fortunately, consistent with the Los Cabos Airport Immigration regulations, Americans don't need a passport to go to this beautiful destination. Instead, you'll use a certificate, voter registration card, citizenship card, or certificate of naturalization alongside a legitimate photo ID.

3 Puerto Limon, Costa Rica

You may think there is no way you're stepping into Costa Rica without a passport, seeing as it is a country in Central America—but re-evaluate. Many Miami- or San Diego-based cruises sail bent Puerto Limon, one among the most important cities on the coast of Costa Rica. Here, you'll explore the city's untouched nature by taking an open-air tram ride through the Veragua Rainforest or taking a pontoon boat through the Tortuguero Canal. And as a crop-heavy area, don't leave on faith out an area Costa Rican plantation, where you'll see how items like bananas, chocolates, or cacao beans are selected, harvested, and packed for export.

4 Belize City, Belize

You better believe you'll love Belize, even without a passport. This city in Belize (just like its Costa Rican cousin Puerto Limon) is accessible through cruises out of the states, from cities like New Orleans and Miami. And while Belize isn't known for its beaches, per se, here you'll explore the Belize coral reef, which hosts diverse, exotic marine life. But what you absolutely cannot afford to miss in Belize is that the Mayan ruins. the foremost popular is Altun Ha, located just 3o miles northwest of Belize City. For thousands of years, the Mayans occupied this space, and core structures were restored so that today, tours could take visitors to the present historic landmark.

5 Roatán, Honduras

Located off the coast of Honduras, Roatán is an island called in the Caribbean. But unlike other Caribbean destinations, this one offers paradise without the high tag. Around 30 miles long, this small island may be a popular retirement destination thanks to its exotic, yet laid-back tropical nature. And its best secret? it is a hot spot for skin diving. The island is surrounded by the Mesoamerican Reef, a subculture of coral reefs, mangroves, and magnificently unique marine life. While you will need a passport to urge there by plane, countries like Honduras are "waiving the need for cruise passengers unless those passengers start or end their voyage there." So as long as you're on a closed-loop cruise that starts and ends within the states, you're liberal to explore paradise sans passport.

6 Saipan, Northern Mariana Islands

The Northern Mariana Islands have the simplest of both worlds: Scenic oceans and mountainous landscapes. As a commonwealth of the U.S., the 14 islands that structure the Northern Mariana Islands are located within the northwestern Pacific on the brink of Guam, another unincorporated territory. Most of the population lives on Saipan, the most important island. you'll either visit one among its breathtaking beaches like Micro Beach or experience an off-road adventure to the rocky Forbidden Island. But the pièce de résistance is that the Banzai Cliff, a historic war II area on the northern tip of the island. As an area for both reflection and paying respects, the scenery off this cliff is breathtakingly beautiful. And a bit like Guam, per the U.S. Customs and Border Protection's Carrier Information Guide, U.S. citizens who travel directly between the states and one among the territories "without touching a far off port or place," aren't required to present a passport.

7 Hamilton, Bermuda

Nestled within the middle of Bermuda is Hamilton, the island's capital. the town is understood for its pastel-colored buildings that line the harbor and house beach-chic boutiques and native restaurants. Visit the town Hall and humanities Centre for a few fascinating 17th- and 18th-century European paintings or the Bermuda Underwater Exploration Institute if you are looking for marine exhibits and ocean artifacts. But if you would like to travel to the simplest a part of Bermuda, you will have to travel across the town to Horseshoe Bay Beach—one of the world's most Instagrammable beaches, with blush pink sand and crystalline water. to urge here without a passport, take a closed-loop Royal Caribbean cruise from Cape Liberty, New Jersey.

8 Tumon, Guam

As an unincorporated U.S. territory, Guam is probably the furthest American-based place you'll visit, nestled within the Philippine Sea near Australia and South Asia. Tumon is found on the northwest coast of the territory, referred to as the middle of Guam tourism. There you'll visit UnderWater World, one among the most important tunnel aquariums within the world. or maybe take a visit to Punta Dos Amantes, a clifftop destination with scenic ocean views. And while having a passport is suggested for anyone traveling to Guam, there are some loopholes for U.S. citizens where they'll be ready to get out of it. Videos say Americans can visit the world passport-free if traveling directly from the mainland, Alaska, or Hawaii, and that they have any proof of citizenship sort of a certificate or certificate of naturalization.

9St. John, U.S. Virgin Islands

Located within the Caribbean, St. John is that the smallest of the U.S. Virgin Islands, but it is the perfect destination for anyone who loves natural beauty. Nearly two-thirds of the island is haunted by Mary Islands park, which shelters forests filled with many colorful birds from cuckoos to warblers and hummingbirds. But when you are not getting your forest fill, visit the gorgeous Trunk Bay beach, which has sugar soft sand and a treasured underwater snorkeling trail. Like most U.S. territories, you do not need a passport to travel here, but the U.S. Virgin Islands tourist center recommends carrying a raised-seal certificate or government-issued photo ID as you would possibly get to "show evidence of citizenship."

10 Montreal, Canada

Contrary to popular belief, as long as you're traveling by land or sea—so as an example, in your car—you aren't required to point out a U.S. passport thanks to the occident Travel Initiative. Instead, you ought to carry along proof of your citizenship and a legitimate photo ID. But if that creates you nervous, there are closed-loop cruises that begin from various New England cities and sail to Montreal. This French-speaking Canadian city is as close as you'll get to Europe without a passport. Here, you'll enjoy French pastries like macarons or visit historic landmarks that rival those in Paris, just like the Notre-Dame Basilica of Montreal.

11 Nassau, Bahamas

The Bahamas is one of the foremost popular cruise destinations from the states, and like many who've gone known, you do not need a passport. because the capital of the Bahamas, Nassau is found off the shore of the mainland on its island. One feature that draws tourists is the pastel-colored Colonial buildings, just like the Government House which may be a bright shade of pink. But Nassau, of course, is not just about the buildings—it's about the beach retreats. Within the past few years, a mega-resorts opened in Nassau called Baha Mar. The 1,000-acre, $4.2 billion property is comprised of three hotels: the Grand Hyatt, SLS Baha Mar, and Rosewood Baha Mar. And when hunger strikes, breeze by The Cove at Atlantis for fresh seafood at Fish by chef José Andrés.

12 Vieques, Puerto Rico

Puerto Rico is perhaps the foremost well-known U.S. territory, so there is no got to stress over getting a passport before visiting. As long as you're directly traveling from the states or another territory, it isn't necessary. So while you're there, you ought to visit Vieques, a little Caribbean Island off the territory's eastern coast. This area offers secluded beaches, beautiful blue-green waters, and therefore the best part? Wild horses that just roam the countryside. But if that does not roll in the hay for you, visit Mosquito Bay, a bioluminescent bay that gives other-worldly views that can't be missed.

13 San Juan, Puerto Rico

Don't recoil from the mainland of Puerto Rico, however. San Juan, the capital and largest city, sits beautifully on its northern coast. If you are looking for a wild tropical trip, visit the Isla Verde resort strip, filled with buzzing bars, nightclubs, and casinos. need a more calm, historic vacation? Take a visit to Old San Juan, the center of colorful Spanish colonial buildings and historic landmarks like La Fortaleza, where the governor resides, or El Morro, a Spanish fort that dates back to the 1500s.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

site preview

hi all! we’re back with our second preview. we’ll have another couple coming to you soon as well. below the cut you’ll find some general information about paris as well as arrondissement descriptions that’ll be part of our site encyclopedia. it’ll be presented a little differently on the site, but the information below will remain the same.

GENERAL OVERVIEW

as the capital of france, paris boasts a population and counting of over two million residents. the city of paris is often described as two-fold. there is paris “proper” which designates the historical city and its 20 arrondissesments, and then the paris metropolitan area that includes the suburbs surrounding paris.

paris-proper does not include skyscrapers, the notable exception is the tour montparnasse and it’s the only skyscraper built in the middle of the city. the building height in paris-proper is limited to the height of 19th century buildings, roughly 10 floors, and most apartment buildings, built by haussmann during the napoleonic era, are six stories tall and tend to be either reserved as luxury homes in the 1st and 6th arrondissement, or are divided in miserly studio apartments.

these building restrictions are to preserve the historical cahcet of the city but also has been the reason the city cannot accommodate the growing population. the housing crisis in paris has been going on for over a century and has not improved since. it is the second most expensive city to live in in the world and anyone living on middle-class wages would either be doing so within the city walls by sharing an apartment or living in substandard conditions. it is not uncommon for students, struggling artists, or performers to occupy shared rooms and small apartments through illegal subletting to cut living costs.

outside paris-proper lies the outer metropolitan parisian suburbs. these range from the chic saint-gratien and sanois, where one can enjoy the tranquility of a nice house and space galore, to the lower-socioeconomic areas like argenteuil, saint-denis and cour-neuve. poverty piles up in the french version of subsidized housing units known as les cités, these are tower complexes where families share the life of an impoverished community leading to any and all excesses such pressures can induce. the outer suburbs are linked to paris-proper by train system, the RER.

THE ARRONDISSEMENT SYSTEM

the twenty arrondissements refer to the twenty subdivisions of paris-proper. they are arranged in the form of a clockwise spiral (often likened to a snail shell), starting from the middle of the city, with the first on the right bank (north bank) of the seine. the smaller the number of the arrondissement, the older and more historical the area is.

first - also known as the ‘premier’ arrondissement. the heart of the city carries some parts of the right bank such as les halles, which has been there since the middle ages. in addition, a large part of this arrondissement is occupied by the louvre and tuileries garden. the central arrondissement is one of the smaller and least populated of all paris. however, what the area lacks in full-time population it certainly makes up for in sheer tourist numbers.

second - known as ‘bourse’ the second arrondissement of the city is the financial one and as such, is home to the parisian stock exchange as well as a myriad of banks and financial institutions. bourse is also the smallest of all arrondissements. bourse is also home to the textile district, sentier and has the highest concentration of covered passages that the city has to offer. these 19th-century built commercial lanes are often covered in beautiful art nouveau façades.

third - the old jewish quarter or ‘temple’ as it is also known is a lively and trendy district, with many faces. you will find lots of high-end art galleries close to beaubourg (which is in the fourth arrondissement). while its winding old streets are full of vintage shops and beautiful hôtel particuliers. temple is also home to the first chinese community in the city as well as museums such as the picasso museum, carnavalet museum, and musée des arts et métiers.

fourth - home to the lively part of le marais; an area filled with bars, clubs, and restaurants which remain open into the early hours of the morning. with a plethora of beautiful and historic architecture throughout this arrondissement it also has top tourist attractions like notre dame, and centre georges pompidou. the fourth arrondissement has a growing lgbtqi+ population living in the area with many spaces for the community.

fifth - a district known worldwide for its history and culture, with sights like the panthéon, the roman arenas (les arènes de lutèce) and the cluny museum. it is also known as the latin quarter of the city, the fifth arrondissement of paris is well-known for its vintage cinema screenings and as a hub of student nightlife. this area is home to some of paris’ most prestigious universities (sorbonne), colleges and high schools.

sixth - known for its famous quartier saint-germain-des-prés, a meeting place for students, artists, and intellectuals during the twenties. visitors come here looking for this long since disappeared atmosphere and are ready to pay ridiculous prices in places like cafe de flore or cafe les deux magots. six is home to luxembourg gardens, saint sulpice church, and nice winding streets. it is also a great district for foodies in paris, as well as luxury boutiques and art galleries, with plenty of tourists ready to empty their wallets here.

seventh - home to the upper-class since the seventeenth century when it became the new residence of french highest nobility. this bourgeois district has the eiffel tower, invalides, and lagerfeld; as well as big avenues with beautiful hôtels particuliers transformed into embassies. the only lively part which deserves a mention are the streets around rue de bac, at quartier sèvres-babylone, full of nice haute-couture and prêt-à-porter shops.

eighth - this is the district of fashion and luxury symbolized by the famous “golden triangle” formed by rue montaigne, rue george v and avenue des champs-élysées. the eighth arrondissement is ultra luxe and undeniably elegant. it is one of paris’ main business quartiers, the current executive branch of french government is based here as well as the élysée palace, where the french president resides.

ninth - from the red-light district of pigalle to opéra garnier, this is a trendy and historic area with its old cafes, offices and haussmannian architecture where you can still can find a true neighborhood life and culture. the streets around st. lazare were parisian central for impressionists. today, the early 19th-century architecture and lovely courtyards have been discreetly preserved. but, watch your safety on rue saint denis.

tenth - one of the trendiest districts in paris, linked to canal saint-martin waterway and iron footbridges. this is a district of bobos (bohemian-bourgeois parisians), with agreeable cafes and vintage shops. it is also the district of two major train stations: gare du nord and gare de l’est. it boasts an always busy and popular atmosphere with a lot of bars at rue de faubourg saint-denis.

eleventh - this arrondissement is one of the most densely populated and urban. with neighborhoods like bastille and oberkampf filled with expats, “hipsters” and young parisians. nightlife is booming, but in a street alley kind of way (don’t expect red carpets). you want to fit in with the urban crowd, explore little wine bars and tiny bistrots on avenue ledru rollin and rue de charonne.

twelfth - the park district of paris. home of parc floral, bois de vincennes, and parc de bercy. it is one of the more residential areas and has more affordable housing than a lot of other arrondissements. a very sleepy district, this quartier went through a major transformation in recent years, and now has modern shops and arena in bercy. you’ll also see opéra de la bastille – the second largest opera house in paris is also a much more modern architecture compared to opera garnier.

thirteenth - a kind of no man’s land with a very popular character and a strong chinese population. this district of paris has some cool things to see and do like the arty butte-aux-cailles neighborhood, some quintessential paris bistros or its incredible street art. the mural program in thirteen has invited the most renowned street artists in the world to give some color to this district of paris.

fourteenth - a predominantly residential quartier that carries a sleepy charm. home to many artists around the world and “the breton” (northwesterners of france) community, this area may be residential but also has many vibrant cafes on boulevard du montparnasse and the rue daguerre. it is also home to parc montsouris, one of the most beautiful parks in paris, as well as the catacombs.

fifteenth - another residential area where locals aren’t too keen on its 1970s high-rises, hence they’ve coined the term moche grenelle (ugly grenelle) to describe parts of the area. located on the left bank of the seine, this arrondissement is home to the likes of the pont bir-hakeim, as well as several parks, notably that of andré-citroën. definitely a family district, very quiet, with no special character, and a long way from everything.

sixteenth - locals call it le seizième, due to the affluent population in the french pop culture. it is the parisian version of new york’s upper east side or london’s kensington. here, you’ll see the most prestigious residential areas in paris and the most luxurious hotels, like the peninsula hotel, and hotel raphael. sixteen also welcomes the french open tennis grand slam every spring. don’t be surprised if you run into an expat family in which the parents have been relocated to work in france.

seventeenth - this district is formed by three very different neighborhoods: merchant quartier de ternes, bourgeois quartier monceau, and arty quartier de batignolles. the 17th is known for batignolles district that was originally outside of paris until napoleon iii included it as part of the city in 1860. a group of artists such as édouard manet based in this area to make a name for themselves by painting scenes of cafes. much like the 15th arrondissement, this area is slightly less touristy than many of the others.

eighteenth - this is the most paradoxical of arrondissements in paris. it is home to montmartre, the quintessential neighborhood in paris, but there are also popular zones long forgotten by everybody like little india, africa, and the infamous goutte d’or neighborhood. with strong bohemian roots it was a gathering place for composers, writers and artists to live in a commune and draw inspiration from the area. many have made their mark here, including: salvador dalí, amedeo modigliani,claude monet, piet mondrian, pablo picasso and vincent van gogh.

nineteenth - a former industrial area developed along canal de l’ourcq. today it is a very popular district with a strong mix of immigrants and a very parisian soul at the same time. it is home to two wonderful parks, parc buttes-chaumont, and parc de la villette. a primarily residential district also known for its world renowned music schools, conservatoire de paris and the philharmonie de paris, both part of the cité de la musique.

twentieth - a few years ago, this was the cheapest district in paris, that’s why so many young parisian couples with lower budgets came here to live. today it is one of the trendiest and most authentic districts of paris and all this without tourists! best known for being home to père lachaise cemetery, there are not many other tourist sites here. however, it has cool cafes, bars, some street art and parc de belleville offers some of the best views of the city of light.

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Jun 29 1918 La fontaine Saint-Michel, place St-André-des-Arts et boulevard Saint-Michel, Paris (VIe arr.), France, A 14 395 S 29 juin 1918 Source: Albert-Kahn Museum / Department of Hauts-de-Seine https://t.co/r14uG5aBdK http://twitter.com/ThisDayInWWI/status/1145021611109523457

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

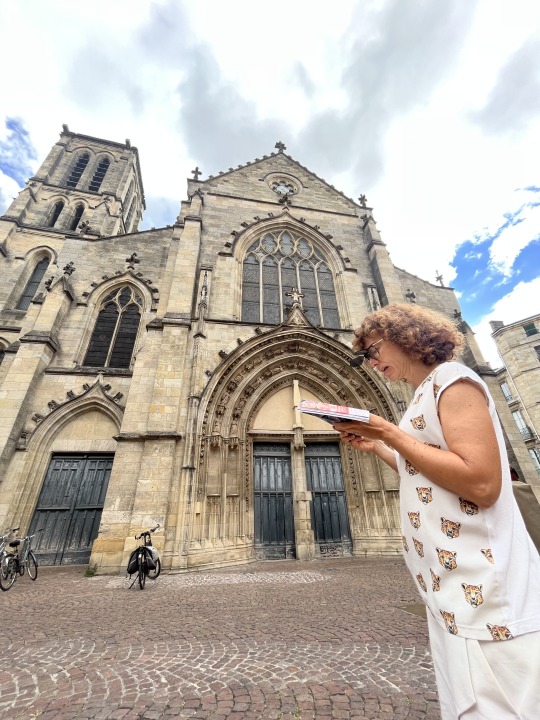

18 de Agosto: Bordeaux

Nos gusta Bordeaux? La tierra es redonda? El CGPJ sigue sin renovarse? Hay realidades indiscutibles. Hoy hemos dedicado el día a repasar los lugares más relevantes de la ciudad, empezando con el Marché des Capucins.

Siguiendo con la Iglesia de la Sainte Croix (cerrada, como siempre).

Es cita inevitable la Basílica de St-Michel, con su correspondiente campanario.

Siguiendo la ruta en paralelo al río, hemos pasado por la Porte Cailhau.

Como no se puede dejar pasar una iglesia, había que figurar frente a St. Pierre antes de llegar a la Place de la Bourse frente al río Garonne. Como ayer sacamos fotos de la Aduana y la Bolsa, hoy hacemos la foto girada hacia la Quai de la Douane.

Y por fin llegamos a uno de los puntos álgidos del día: nuestro paso por Aux marveilleux de Fred para comernos una cramique aux raisins!! La felicidad!

Hemos seguido junto al río en dirección al barrio de Chartrons (en mi opinión, el mejor barrio de la ciudad), pasando por la Bolsa y el Templo - para llegar a la iglesia de Saint-Louis de Chartrons. No hay foto que capture la calidad de vida que se respira en Chartrons.

Y si consideramos que el Jardin Public forma parte de este barrio, ya es como un chuletón al punto: imbatible.

Por tener, tiene hasta los restos de un anfiteatro romano, el Palais Gallien.

Y, de remate, hemos pasado por la basílica (y cementerio paleocristiano) de Saint-Seurin, que ya es otro barrio. Lo que más nos ha llamado la atención es su cripta, con los túmulos de varios santos.

Tras el regreso a casa para apretarnos un buen couscous de merguez, hemos ido a visitar el Museo de Bellas Artes. Nos han dejado pasar gratis porque la cajera era de padres portugueses. Aparte de esa frivolidad, hemos disfrutado de los comentarios en audio, disponibles gratuitamente en su web, a la que he accedido a través de la red wifi gratuita del ayuntamiento. En Francia saben qué es el estado del bienestar y para qué sirven los impuestos.

Mientras visitábamos el museo ha caído un pequeño chaparrón que, a pesar del susto, no ha impedido disfrutar de la visita y del paseo posterior por la ciudad.

Después de eso hemos vuelto a casa a tomarnos un café y acabarnos el bollo de la mañana y coger fuerzas para el último arreón. Empezando por la catedral de San Andrés.

Bajando por Victor Hugo se ve la Grosse Cloche:

Y bastante más tarde ya hemos pasado (tras la FNAC) por la plaza de la Ópera.

Y hemos presentado nuestros respetos como siempre a don Francisco de Goya (insigne exiliado víctima de la ola reaccionaria que siguió al regreso del infausto Fernando VII) a las puertas de Nôtre-Dame, la iglesia donde se celebraron sus responsos cuando falleció.

En Francia se vive bien. Incluso una sardinada tiene una categoría... qué sé yo... une outre chose.

Y ya está! Se acabó lo que se daba. Comienza la recta final de las vacaciones. Mañana salimos hacia Anglet y nos bañaremos en la playa por última vez antes de tomar rumbo hacia Salamanca el domingo.

Buenas noches!

1 note

·

View note

Text

LES POLISSONS DE LA CHANSON : HOMMAGE À GEORGES BRASSENS

Ce spectacle-événement tournant autour de l’œuvre de Georges Brassens verra le jour dès la semaine prochaine, la tournée débutant à la Salle Pauline-Julien de Sainte-Geneviève le mercredi 20 avril. Pour fêter l’œuvre de ce monument de la chanson française, La maison fauve a réuni de grands artistes d’ici au sein d’un spectacle collectif mis en scène par nulle autre qu’Alice Ronfard, dans une conception d’éclairage signée Julie Basse. Ainsi, Valérie Blais, Luc De Larochellière, Michel Rivard, Saratoga et Ingrid St-Pierre voyageront dans l’immense corpus mélodique de l’auteur-compositeur-interprète pour en faire résonner son timbre chaleureux, son verbe libre, poétique et irrévérencieux, sous la direction musicale d’Yves Desrosiers.

Récemment, Michel Rivard s’entretenait avec le Téléjournal de Radio-Canada : « Si on aime la langue, si on aime le plaisir des mots, si on aime la subtilité, la nuisance, la poésie dans sa forme la plus pure, on ne peut pas ne pas aimer Brassens ». Lors de cette même rencontre, Alice Ronfard qui signe la mise en scène du spectacle, parlait de l’importance de l’autre chez Brassens : « Il parle beaucoup d’amitié, il parle beaucoup des copains… de cette chose qu’on a perdu depuis deux ans, c’est-à-dire, d’être ensemble… pour moi, c’est ça le lègue (de Brassens »). Le duo Saratoga parle quant à lui soulignait l’audace de cet artiste qui encore aujourd’hui résonne : « Il a touché à tout ce qui dérangeait, tout ce qui était un peu en marge, mais ça a terriblement bien vieilli ». La plume de Sylvain Cormier pour Le devoir ne pourrait mieux conclure : « Valérie Blais a vu Brassens sur scène, et Michel Rivard lui a serré la main. Un seul degré de séparation. Pour nombre de spectateurs, ce sera presque y toucher. Pour ceux qui découvriront Brassens — oui, ça se peut ! —, l’occasion est à chérir ». C’est à ne pas manquer! Tout ce beau monde à un plaisir manifeste à partager la scène, clin d’oeil et sourires en coin. La camaraderie de Luc, Valérie, Ingrid, Michel, Michel-Olivier et Chantal saura convaincre. Ce sont les plus sympathiques polissons de la chanson!

ÉQUIPE ARTISTIQUE :Mise en scène : Alice Ronfard

Interprètes : Valérie Blais, Luc De Larochellière, Michel Rivard, Saratoga et Ingrid St-Pierre

Musiciens : Yves Desrosiers (direction musicale et arrangements), François Lalonde et Mario Légaré

Conception des éclairages : Julie Basse

DATES ET LIEUX DES REPRÉSENTATIONS :

20 avril : Sainte-Geneviève – Salle Pauline-Julien

21 avril : Joliette – Centre culturel Desjardins

23 avril : Rimouski – Salle Desjardins-Telus

26 avril : Québec – Grand Théâtre de Québec

27 avril : Saguenay – Théâtre Banque Nationale

28 avril : Drummondville – Maison des arts Desjardins Drummondville

29 avril : Terrebonne – Théâtre du Vieux-Terrebonne

30 avril : Longueuil – Théâtre de la Ville

4 mai : Saint-Eustache – Le Zénith Promutuel Assurance

5 mai : Sherbrooke – Centre culturel de l’Université de Sherbrooke

6 mai : L’Assomption – Théâtre Hector-Charland8 mai : Saint-Jean-sur-Richelieu – Théâtre des Deux-Rives

11 mai : Brossard – L’Étoile

12 mai : Victoriaville – Le Carré 150

13 mai : Saint-Jérôme – Théâtre Gilles-Vigneault

14 mai : Sainte-Agathe-des-Monts – Théâtre Le Patriote

19 mai : Laval – Salle André-Mathieu

20 mai : Saint-Hyacinthe – Centre des arts Juliette-Lassonde

21 mai : Gatineau – Salle Odyssée

18 juin : Francos de Montréal – Théâtre Maisonneuve de la Place des arts

0 notes

Text

Becoming Machine: Surrealist Automatism and Some Contemporary Instances

Involuntary Drawing

DAVID LOMAS

Examining the idea of being ‘machine-like’ and its impact on the practice of automatic writing, this article charts a history of automatism from the late nineteenth century to the present day, exploring the intersections between physiology, psychology, poetry and art.

Philippe Parreno’s The Writer 2007 (fig.1) is a video, played on a screen the size of a painted miniature, of the famous eighteenth-century Jaquet-Droz automaton recorded in the act of writing with a goose quill pen. Zooming in on the automaton’s hand and face, Parreno contrives to produce a sense of uncertainty as to the human or robotic nature of the doll. It is an example of a contemporary fascination with cyborgs and with the increasingly blurred dividing line between machine and organism. In a manner worthy of surrealist artist René Magritte, Parreno plays on the viewer’s sense of astonishment. As the camera rolls, the android deliberates before slowly writing: ‘What do you believe, your eyes or my words?’ The ‘Écrivain’ is one of the most celebrated automata that enjoyed a huge vogue in Enlightenment Europe. In a lavish two-volume book, Le Monde des automates (1928), Edouard Gélis and Alfred Chapuis define the android as ‘an automaton with a human face’.1 A chapter of this book, which supplied the illustrations for an article in the surrealist journal Minotaure, is devoted to drawing and writing automata.2 The oldest example Gélis and Chapuis cite was fabricated by the German inventor Friedrich von Knauss whom, they state, laboured at the problem of ‘automatic writing’ for twenty years before presenting his first apparatus in 1753.3

Fig.1

Philippe Parreno

The Writer 2007

Photographic still from DVD

3:58 minutes

Courtesy the artist and Haunch of Venison, London © Philippe Parreno

The graphic trace

From the mid-nineteenth century onwards, recording instruments became vital tools in the production of scientific knowledge in a range of disciplines that were of direct relevance to surrealism. Such mechanical apparatuses, synonymous with the values of precision and objectivity, quickly became the benchmark of an experimental method. The inexorable rise of the graphic method has been intensively studied by historians of science and visual culture, but surrealism has not yet been considered as partaking of this transformation in the field of visual representation. In what follows, recording instruments are shown to have helped to underwrite surrealism’s scientific aspects and bolster its credentials as an experimental avant-garde.

The graphic method inaugurated a novel paradigm of visual representation, one geared towards capturing dynamic phenomena in their essence. It was the product of a radically new scientific conception of the physical universe in terms of dynamic forces, a world view that is doubtless at some level a naturalisation of the energies, both destructive and creative, unleashed by industrial capitalism.5The proliferation of mechanical inscription devices in the life sciences coincided with the displacement of anatomy, as a static principle of localisation, by physiology, which analysed and studied forces and functions. Étienne-Jules Marey, known today as an inventor of chronophotography, was one of the main exponents of the graphic method in France, and he personally devised a number of instruments whose aid, he wrote, made it possible to ‘penetrate the intimate functions of organs where life seems to translate itself by an incessant mobility’.6 As an apparatus for visualisation, the graphic method carries implications for how to construe figures of the visible and invisible. It was not simply a technology for making visible something that lay beneath the human perceptual threshold (like a microscope), but rather a technology for producing a visual analogue – a translation – of forces and phenomena that do not themselves belong to a visual order of things.7

At its simplest, a frog’s leg muscle is hooked directly to a pointed stylus that rests on a drum whose surface is blackened with particles of soot from a candle flame (fig.2). An electrical stimulus causes the muscle to contract, deflecting the stylus and thus producing on the revolving drum a typical white on black curvilinear trace. Fatigue of the muscle produces an increased duration and diminished amplitude of successive contractions, as shown in the figure at the bottom. A more sophisticated device pictured by Marey consisted of a flexible diaphragm, a sort of primitive transducer, connected by a hollow rubber tube to a stylus, which inscribed onto a continuous strip of paper. At the heart of the graphic method is the production of a visible trace.8 A stylus roving back and forth on a rotating cylinder or a moving band of paper translates forces into a universal script that Marey regarded as ‘the language of the phenomena themselves’ and which he proclaimed is superior to the written word.9 In an era where quantitative data gradually became the common currency of scientific discourse, Marey considered written language, ‘born before science and not being made for it’, as inadequate to express ‘exact measures and well-defined relations’.10 The incorporation of a time axis owing to the continuous regular movement of the drum lends a distinctive property to the graphic trace. The historian Robert Brain remarks that ‘the graphic representation is not an object or field like that of linear perspective, but a spatial product of a temporal process, whose order is serial or syntagmatic’.11 Units of time are marked off at the bottom of the myographic trace as regular blips on a horizontal axis; additionally, the passage of time is registered in the palimpsest-like layering of successive traces.12

Fig.2

Simple myograph (top) and trace of repeated muscular contractions (bottom)

From Etienne-Jules Marey, La Méthode graphique dans les sciences expérimentales et principalement en physiologie et en médecine, Paris 1875, p.194

From its initial applications in physiology, the graphic method soon made inroads into areas such as medicine and psychology, eager to prove their scientific legitimacy. The familiar chart of a patient’s temperature, pulse, and respiration had become standard fare in hospital wards by the mid-nineteenth century.13 Marey went so far as to predict that the visual tableau comprised of such ‘medical curves’ would replace altogether the written record. The growth of medical specialties saw doctors attempting to justify their status and claims to authoritative knowledge by adopting the tools-in-trade of an experimental science. The Salpêtrière Hospital in Paris, under neurologist Jean-Martin Charcot, was at the forefront of these developments, and graphic traces are liberally interspersed among the better-known photographs, engravings, and fine art reproductions of Charcot’s book Iconographie de la Salpêtrière (1878). Employed first for the investigation of muscular and nervous disorders, the myograph was subsequently applied by Charcot to the study of hysteria. By enabling the hysterical attack to be objectively recorded in the form of a linear visual narrative, the graphic trace performed an invaluable service in conferring a semblance of reality upon a condition that was widely dismissed as mere playacting or simulation (fig.3).

Fig.3

Epileptic phase of an hysterical attack

From Paul Richer, Études cliniques sur l’hystéro-épilepsie ou grande hystérie, Paris 1885, p.40.

Nearer in time to the surrealists, the hysteria problem was revived with particular urgency in the guise of shellshock, and there again physicians placed their faith in the graphic method as a means of reliably excluding simulation where clinical observation alone was of no avail. Evidence of the surrealist André Breton’s first-hand acquaintance with such devices is not hard to find. Soon after his arrival at the neuro-psychiatric centre at St Dizier in August 1916 he writes excitedly to Théodore Fraenkel, a fellow medical student, saying that all his time is devoted to examining patients. He details his technique for interrogating his charges and in the same breath adds ‘and I manipulate the sphygmometric oscillometer’.14 The instrument to which Breton refers gives a measure of the peripheral pulses and would have been used by him to detect an exaggerated vascular response to cold that was held to be a diagnostic feature of reflex nervous disorders. There is a reasonable likelihood that Breton also came in contact with the use of a myograph for the same purpose, either at St Dizier or the following year when he was attached as a trainee to neurologist Joseph Babinski’s unit at the Pitié Hospital in Paris. Breton possessed a copy, with a personal dedication from the authors, of Babinski and Jules Froment’s Hystérie-pithiatisme et troubles nerveux d’ordre réflexe en neurologie de guerre (1917), a textbook profusely illustrated with myographic traces.

As a newly formed discipline, psychology was also quick to integrate the paraphernalia of experimental physiology.15 Alfred Binet, one of the pioneers of psychology in France, employed the graphic trace as an instrument more sensitive in his opinion than automatic writing for revealing a dissociation of the personality in cases of hysteria. ‘In following our study of the methods that enable us to reveal this hidden personality’, Binet writes, ‘we are now to have recourse to the so-called graphic method, the employment of which, at first restricted to the work-rooms of physiology, seems, at the present time, destined to find its way into the current practice of medicine’.16 The definition of psychology as experimental is seen to be closely tied with the use of a measuring instrument. Binet’s goal appears to be an almost paradoxical exclusion of the subject, with its nigh infinite capacity for dissimulation, from the scientific investigation of that subject’s own subjectivity. Coinciding with the introduction of quantitative forms of measurement, introspection rapidly fell into disrepute as a method of inquiry. Robert Brain’s observation that in the field of psychology ‘the graphic method served both as a research tool and a source of analogies for investigating mental activities’ is certainly to be borne in mind with regard to surrealism.17

Alongside mainstream science, recording devices also made incursions into psychical research. The use of such apparatuses to restrict the latitude for fraud contributed to the general air of scientific enquiry. The historian Richard Noakes has shown that the intractable problems of researching mediums, their notoriously capricious and untrustworthy nature, led some experimenters to suggest that sensitive instruments alone could replace the human subject as a means of accessing the spirit world.18 In the 1870s, William Crookes, a respected chemist and a pioneer in the application of measuring instruments to spiritualist research, devised an apparatus for recording emanations from the body of the medium Daniel Dunglas Home, as a result of which he claimed to have discovered a mysterious new form of energy, which he termed ‘Psychic Force’ (fig.4).19 A Marey drum was used to make physiological recordings of the medium Eusapia Palladino, who had been often exposed for cheating in the past, during a highly publicised series of séances conducted under controlled experimental conditions at the laboratories of the Institut général de psychologie in Paris.20

Fig.4

Apparatus for recording the emanation of psychic force from a medium.

From William Crookes, Researches in the Phenomena of Spiritualism, London 1874.

Modest recording instruments

It would appear that surrealism was not indifferent to the lure of the graphic method. The particular aspect to foreground here is the promise of objectivity. The graphic method offered the prospect of bypassing altogether the human observer who was increasingly liable to be viewed as a source of error in scientific experiment. With precision and objectivity the yardsticks of science by the latter part of the nineteenth century, the historian Peter Galison remarks that ‘the machine as a neutral and transparent operator … would serve as instrument of registration without intervention and as an ideal for the moral discipline of the scientists themselves’.21 Addressing the graphic trace in these terms, Marey strikingly adumbrates the language of surrealism in remarking that ‘one endeavoured to write automatically certain phenomena’.22 The surrealists spoke of their art and literary productions as objective documents and advocated an objective stance that sidelines the authorial subject who was meant to be as near as possible a passive onlooker at the birth of the work. Or, in Breton’s words, a modest recording device: ‘we, who have made no effort whatsoever to filter, who in our works have made ourselves into simple receptacles of so many echoes, modest recording instruments not mesmerised by the drawings we are making.’23 Closely allied with this imperative to become akin to a machine is a metaphorics of the trace and tracing: ‘here again it is not a matter of drawing, but simply of tracing’, Breton insisted in the 1924 ‘Manifesto of Surrealism’.24

The accent on objectivity is consonant with surrealism’s avant-gardist ethos of experiment, stemming ultimately from science. In fact, Breton contended that by the time the manifesto had been published, five years of uninterrupted experimental activity already lay behind it.25 Around the time of the manifesto, the surrealists set about creating a research centre of sorts, the short-lived Bureau of Surrealist Research, testifying to the earnestness of their experimental impulse. However, it was no ordinary laboratory that opened to the public at 15 Rue de Grenelle, Paris, in October 1924. The surrealist playwright and poet Antonin Artaud recalls that a mannequin hung from the ceiling and, reputedly, copies of the crime fiction volume Fantômas and Sigmund Freud’s The Interpretations of Dreams framed with spoons were enthroned on a makeshift altarpiece. The second issue of the house journal La Révolution surréaliste, the cover of which was modeled on the popular science magazine La Nature, carried an announcement of its purpose:

The Bureau of Surrealist Research is applying itself to collecting by all appropriate means communications concerning the diverse forms taken by the mind’s unconscious activity. No specific field has been defined for this project and surrealism plans to assemble as much experimental data as possible, without knowing yet what the end result might be.26

Asserting a parallel with science, as Breton was fond of doing, was a way of implying that surrealism was dedicated to finding practical solutions to vital problems of human existence, and of distancing it as far as possible from a posture of aesthetic detachment. The statement above identifies the unconscious as the privileged object of surrealist research. Automatism, from this point of view, could be understood as a research method, a set of investigative procedures that organise and govern practice but do not determine outcomes. The openness of scientific inquiry is something that may have been especially attractive to surrealism; the final clause above insists upon their refusal to define goals – a programme – which would have run the risks of a reductive instrumentalism or empty utopianism. At the same time, however, bearing in mind the extreme animosity towards positivism that Breton notoriously gives vent to in the 1924 manifesto, the dangers for surrealism of too close a proximity to science should not be overlooked. Perhaps for this reason, Artaud, in a report on the bureau carried in the third issue of the journal, argues warily for the necessity of a certain surrealist mysticism. A survey of the terms ‘research’ and ‘experiment’ in the period would reveal that much the same vocabulary was utilised in the marginal, pseudo-scientific world of spiritualism and parapsychology as by mainstream science, and it is notable that surrealist experimentation happily straddles these seemingly contradictory currents. The hypnotic trance sessions, one of the main experimental activities engaged in by the nascent surrealist group, are illustrative of this cross-over between science and the occult. 543 pages of notes and drawings obsessively documenting the sessions, which took place nightly between September and October 1922, were preserved by Breton and included among a list of artworks, books and other objects housed in the bureau.

While Salvador Dalí did not partake of the ‘birth pangs’ of surrealism, as Breton ruefully observed, his overheated imagination provides a vivid if fanciful evocation of this first phase of surrealist experiment. In an essay written in 1932, Dalí conjures up an improbable scenario of hypnotic subjects wired to recording devices like the unfortunate frog in Marey’s illustration, though in this case it is the trace of poetic inspiration that is expectantly awaited:

All night long a few surrealists would gather round the big table used for experiments, their eyes protected and masked by thin though opaque mechanical slats on which the blinding curve of the convulsive graphs would appear intermittently in fleeting luminous signals, a delicate nickel apparatus like an astrolabe being fixed to their necks and fitted with animal membranes to record by interpenetration the apparition of each fresh poetic streak, their bodies being bound to their chairs by an ingenious system of straps, so that they could only move a hand in a certain way and the sinuous line was allowed to inscribe the appropriate white cylinders. Meanwhile their friends, holding their breath and biting their lower lips in concentrated attention, would lean over the recording apparatus and with dilated pupils await the expected but unknown movement, sentence, or image.27

Dalí clearly took to heart Breton’s exhortation to his fellow surrealists that they should make themselves into ‘modest recording instruments’. Inspired by extant photographs that afford a rare glimpse of the legendary bureau, Dalí conjures up a fantastical laboratory with pliant subjects hooked to a plethora of arcane recording devices.

Beyond a serviceable metaphor employed by Breton, what evidence is there for the graphic method as having any bearing on the actual practice of automatic drawing? While scattered instances of direct citation of graphic traces can be demonstrated, what is more significant is that this novel regime of visuality, beginning as a style of scientific imaging and becoming by the time of surrealism a widely circulated and understood visual idiom, was a necessary historical antecedent in order that the automatist line might be imbued with meaning as the authentic trace of unconscious instinctual forces and energies (in its absence, they would have been literally unreadable in these terms). With the precedent of the graphic trace available to them, it was possible for surrealist artists to imagine how they might square the circle by integrating temporal duration within a static visual medium.

‘Could it be that Marcel Duchamp reaches the critical point of ideas faster than anyone else?’, wondered Breton. It is a question that can profitably be asked in examining the impact on avant-garde artists of an avowedly scientific visual idiom. Duchamp, and his artistic collaborator Francis Picabia, around 1912 to 1913 rejected traditional painterly techniques, along with extreme subjectivism that had reached a zenith in the neo-symbolist circles both artists had been involved with up until that point, and turned instead to technical drawing and scientific illustrations as alternative, non-artistic sources of inspiration. Duchamp’s 3 Standard Stoppages 1913–14 (fig.5) is evidence of his search for what art historian Linda Dalrymple Henderson calls ‘the beauty of indifference, the counterpart to his painting of precision’.28 For this work, one-metre lengths of thread were allowed to fall from a height of one metre, and the random configurations formed as they came to rest on the ground were fixed and recorded. Displaying the resultant shapes as curved white lines on a long horizontal black strip of canvas would have rung bells with viewers familiar with the then standard repertoire of scientific imaging practices. The typical format of the graphic trace served as a convenient shorthand by means of which Duchamp encoded the desired values of precise measurement and objectivity. Not for the first (or last) time did Duchamp appeal to forms of visual competency that had begun to creep into the common culture, as art historian Molly Nesbitt’s pioneering study relating his use of technical drawing to reforms in the French school curriculum shows.29 The creation of wooden templates or stencils based on the resultant curves is also significant: these were utilised to transfer the curves to other works, notably Network of Stoppages 1914 (Museum of Modern Art, New York) and the capillary tubes in the Large Glass 1915–23 (Tate T02011), but in addition they provide a measure of the area beneath the curve which, as every student of basic calculus knows, is equal to the integral of the curve.

Marcel Duchamp

3 stoppages étalon (3 Standard Stoppages) 1913–14, replica 1964

Tate

© Succession Marcel Duchamp/ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2018

Of the surrealist artists, links between art and science run deepest in the work of Max Ernst, who attended lecture courses on psychology while he was a student at university in Bonn.30 Scientific illustrations and tables are frequent source materials for Ernst’s collage, among which are examples of graphic traces, most notably the illustrations to the book Les Malheurs des immortels (1922), a collection of collages and automatic poems produced collaboratively with the surrealist poet Paul Éluard. Between the Two Poles of Politeness is one of at least two collages in the book to utilise a graphic trace, which functions as a ground for the image and a springboard for the artist’s imagination. The typical white-on-black format is exploited by Ernst to evoke a night sky against which the solid white line of the trace stands out starkly. He embellishes the horizontal x-axis marked on the graph by a dotted line with a distant polar landscape that appears to echo the peaks and troughs of the graphic trace. At the left-hand edge of the image, the lines of the graph are extended so they appear to converge towards a vanishing point; the net effect of these hand-drawn additions is to produce incongruities of scale as well as an ambiguous play between the flat space of the diagram and an illusory perspectival space. Accentuating the horizon serves to foreground the idea of a horizon of vision, beyond which normally one cannot see, and thus implies the existence of an invisible realm to which surrealism affords access.