#SARS-CoV-2 is not “just a cold”

Text

It's still not just a cold.

"This study showing that severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus directly infects coronary artery plaques, producing inflammatory substances, really joins the dots and helps our understanding on why we're seeing so much heart disease in COVID patients," Peter Hotez, MD, professor of molecular virology and microbiology at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, told Medscape.

Oh, also?

CDC predicts respiratory disease season will be similar to last year

"The CDC said it expects a similar number of respiratory disease cases this year as last year, with 15 to 25 new weekly hospitalizations per 100,000 people."

"As of Friday, nearly 12 million people have gotten the new Covid-19 vaccine since they were authorized last month, according to HHS. That’s millions more than the week prior, but still less than 4% of the US population."

No one is protecting themselves. And no one else will protect you.

Even if you're not worried for yourself....don't be one of the people that carries it to someone else. We're all responsible for the most vulnerable people in our society. (That could be you, by the way.....)

WEAR. YOUR. MASK.

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Here, I will give you, the reader, clear enumerations where SARS Cov 2 is unlike a common cold.

SARS Cov 2 triggers a unique, long-lived inflammatory overreaction unseen in Sepsis and influenza.

SARS Cov 2 sends T cells into the brain while lethal influenza does not.

SARS Cov 2 directly causes autoimmunity by reprogramming a special type of T cell called the T regulatory cell, which has never been observed before.

The human genetic line has not propagated any sarbecovirus elements therefore never has faced Sarbecovirus infection to the extent to evolutionarily adapt, except in the unlikely theoretical possibility of extremely negative selection (meaning infected humans did not create progeny.)

There are more exceptional facets but these are simple and digestible. There is also more to write about but I must make a confession. The status quo has morphed in such a way as to browbeat scientists into disavowing a harsh reality in order to acquiesce to corporate and business interests. As we see the average life expectancy decline, we have been left intellectually out in the cold. The truth tellers have been assaulted and crushed, and the individuals that comprise the public, in denial, will put off the realization of a below 70s life expectancy until each one approaches retirement in piecemeal, just as all the grains of sand in an hourglass do not fall at once.

93 notes

·

View notes

Text

🎇 NYE COVID-19 RED ALERT - AVOID CROWDS & MASK UP 🎆

You wouldn't know it from our governments, but Turtle Island, aka the US & Canada, are in the worst spike of illness and deaths since 2020's deadly Omicron surge.

That means it's more dangerous to go to a New Years party this weekend than it's been for approximately 96.4% OF THE ENTIRE PANDEMIC. It's bad out there tonight, and your odds of staying healthy after an unmasked gathering are NOT good.

The more people at your party, the higher the chance you'll catch COVID-19. You may think it's worth the risk, since many people appear to have "mild" infections, but that's not the whole story.

The first 2 weeks of COVID-19, aka the "acute phase", are just the beginning. Even if you don't need emergency hospitalization, or even if you never have any symptoms at all, the virus SARS-CoV-2 responsible for COVID-19 silently turns your immune system against you and shreds the lining of your circulatory and nervous systems. This can permanently elevate your risk of heart attacks, strokes, digestive problems, and even life-changing disabling disorders like ME/CFS.

And even if you escape relatively unscathed, you could pass the virus onto loved ones who WILL get hit hard, and survive with new life-long disabilities, or not survive at all.

COVID-19 never left, and our healthcare systems are NOT looking out for us. We have to take care of each other. Please, please rethink going out to that party tonight. If you can't avoid socializing, please protect yourself as much as you can:

Wear WELL-FITTING respiratory masks like N95s & KN94s

Use nasal sprays before & after, & CPC mouthwash after

Gather outdoors whenever possible

Get good air circulation indoors with air filters like CR Boxes, or open windows for outside air (bundle up if it's cold)

More resources on these tips, and how to reduce the damage if you do get sick, can be found on this COVID Safety Roundup list. All graphics courtesy of the Pandemic Mitigation Collection and Dr. Michael Hoebert, from their website. Hoebert further breaks down the data on his twitter too.

You can also ask me any particular questions and I'll do my best to help! We all deserve to survive this, and we'll do it together.

#covid 19#long covid#still masking#mask up#actually disabled#covid isn't over#covid19#new year#happy new year#new years eve

89 notes

·

View notes

Note

What is phage therapy? I heard the word somewhere and now it’s stuck in my head but I don’t know what it is. Thanks 🙌

Phage therapy is the therapeutic use of viruses to kill bacteria.

Viruses are semi-living things that use other cells to reproduce. They do this by injecting DNA or RNA into the cell, letting the cell make copies of the genetic material, manufacture proteins, assemble new viruses, and then those new viruses burst out of the cell. In the process of reproducing, the cell is killed.

We typically think of viruses that replicate in human tissue, like influenza or SARS-CoV-2. But as it turns out, where there is a cell, including a plant cell or a bacterial cell, there is a virus that wants to kill it to make baby viruses.

Theoretically, then, if someone has a bacterial infection, we can find the extremely specific virus that kills only the bacteria that are causing the infection, infect the person with that virus, let that virus replicate and kill a bunch of the bacterial cells without harming the human cells, and voila, no more infection. Once the virus runs out of bacterial cells it can't replicate any more and it dies off.

And when I say "theoretically" I mean we have absolutely, definitely done this. Like a lot. And while phage therapy is extremely difficult to do good clinical trials with, as far as we can tell it's been pretty effective, and has few side effects that we know about.

So why don't we use phage therapy all the time?

Well, probably because of how specific the phages are. The phage that kills one kind of staph probably won't work on another kind of staph. So you need giant libraries of phages in order for them to really be useful to a large number of people.

Also, there's politics:

See, depending on what you consider the start of the antibiotic age, phage therapy and antibiotic therapy kind of came into being around the same time. By the start of WWII we had a couple of each worldwide.

Then the war happened and the Iron Curtain came into being. On the Western side resources were funneled into the mass production of a new antibiotic called penicillin, and on the Eastern side, resources were funneled into further developing phage therapy.

Throughout the Cold War this pattern would continue, with the Soviet Union eventually using both antibiotics and phages, and the West using only antibiotics (honestly, it's probably capitalism's fault- making money from phages is extremely difficult because they can't be mass produced like antibiotics can). When the Soviet Union fell apart, the research on phage therapy largely disappeared with it.

The West, now saddled with the burden of antibiotic resistance after decades of overprescription and use in agriculture, is trying to rebuild some of the knowledge that was lost with the fall of the Soviet Union.

Unfortunately, there have only been a handful of people who have been treated with phage therapy in the West. This is because the way phages work makes them extremely difficult to do high quality studies on, which makes them impossible to get FDA approval for in the US. Another factor standing in the way of approval is that they tend to change over time as the bacteria they replicate in evolve. So there are potential approval problems if we approve one type of phage but not the type it becomes in a few years.

So if something needs to change itself to work, how do you monitor to make sure that the changes aren't something dangerous? Do you have to repeatedly apply for approval? It just has all kinds of legal and policy issues.

If you want more info, there is a book called The Perfect Predator by Steffanie Strathdee. The author ended up saving her husband's life using phage therapy after he ended up with a life-threatening multidrug resistant infection.

If you want something shorter than a book, I highly recommend this video by Patrick Kelly.

43 notes

·

View notes

Text

Highlights

"SARS-CoV-2 strongly inhibits mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) resulting in increased mitochondrial reactive oxygen species (mROS) production."

"The perturbation of mitochondrial bioenergetics and (mROS) lie at the center of COVID-19 pathophysiology and the resulting alterations of mitochondrial metabolites could modify the epigenome to suppress OXPHOS gene expression even after viral genomes had been eliminated."

"The most common manifestations of long-COVID [post-exertional malaise, fatigue, brain fog, dizziness, gastrointestinal symptoms, heart palpitations, hormonal alterations, thirst (blood sugar alterations), chronic cough (inflammation), chest pain, and abnormal movements (cerebellar effects)] are also among the array of manifestations of known mitochondrial diseases."

"Consequently, the post-viral epigenomic suppression of OXPHOS gene expression may be an important factor in the pathophysiology of long-COVID."

"If so, the most effective metabolic therapies to mitigate acute and long-COVID could be to increase OXPHOS and decrease mROS."

Tell me again it's "just a cold"

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

i can never understand all the people going “covid’s just a cold” “it’s just like the flu”. it’s not influenza or a rhinovirus. covid sars-cov-2: severe accute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2. scientifically, it can never be a cold or flu, and it will cause severe accute respiratory syndrome. that’s not posturing or dramatics, it’s science

#also looking at long term symptoms of sars1. i think in 5-10 years we’re going to start seeing a barrage of horrible long term symptoms and#find out a lot of people never fully recovered#that’s what gets me is like. when i talk about covid my backing is from scientific journals and studies and then my own personal experience#watching someone die of covid. meanwhile people are like ‘well i read in an article’ or ‘well the cdc says’. also y’all the cdc is not forth#coming about covid info. they definitely don’t publicise things. but they still have information on their website that’s concerning that i#think if they publicised would make a lot more people concerned about the pandemic again#for example. Covid causes sepsis. this is something you can find on pub med and on the cdc website#if you’re curious: https://www.cdc.gov/sepsis/what-is-sepsis.html#it’s under ‘what causes sepsis’#also once again. all the studies about long term symptoms coming out and the damage covid does to the body are horrifying#coronavirus#imagine if people said ‘yeah I just tested positive for severe accute respiratory syndrome’

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

There is a huge lobby for normalization of SARS Cov 2. Entire industries depend on the public’s return to normal consumer and working behaviors. As such, the rationalizations and reassurances to the public that SARS Cov 2 is a normal seasonal Coronavirus are relentless. These are constructed like homilies and catch-phrases, such as “we must learn to live with it,” and, “it’s endemic,” with the implication of its endemicity referring to the abandonment of efforts which acknowledge its existence, such as testing.

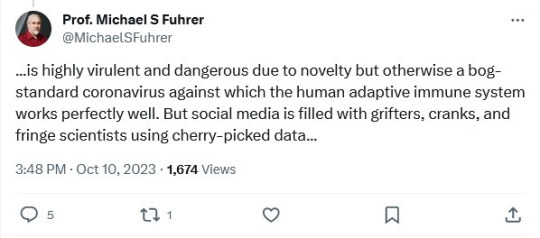

It is a complete misconception that introduction of a virus to the immune system makes subsequent infections like a common cold, and that virulence is due to novelty. If nerves, organs, and immune systems could speak, they would tell a tale of exceptional inflammation, aging, and death, which we must turn to science to hear. Professor Fuhrer would be taken aback to find there are efforts to examine specific mechanisms which tell another tale than his own.

Here, I will give you, the reader, clear enumerations where SARS Cov 2 is unlike a common cold.

SARS Cov 2 triggers a unique, long-lived inflammatory overreaction unseen in Sepsis and influenza. https://genomemedicine.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13073-023-01227-x

It caused cells of the immune system to react in a way to create further inflammation and activation of the immune system for an extended amount of time. For technical facets of this, please see the paper.

SARS Cov 2 sends T cells into the brain while lethal influenza does not.

SARS Cov 2 directly causes autoimmunity by reprogramming a special type of T cell called the T regulatory cell, which has never been observed before. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fimmu.2020.589380/full

The human genetic line has not propagated any sarbecovirus elements therefore never has faced Sarbecovirus infection to the extent to evolutionarily adapt, except in the unlikely theoretical possibility of extremely negative selection (meaning infected humans did not create progeny.)

There are more exceptional facets but these are simple and digestible. There is also more to write about but I must make a confession. The status quo has morphed in such a way as to browbeat scientists into disavowing a harsh reality in order to acquiesce to corporate and business interests. As we see the average life expectancy decline, we have been left intellectually out in the cold. The truth tellers have been assaulted and crushed, and the individuals that comprise the public, in denial, will put off the realization of a below 70s life expectancy until each one approaches retirement in piecemeal, just as all the grains of sand in an hourglass do not fall at once.

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chinese Hospitals Are Housing Another Deadly Outbreak

In Beijing and other megacities in China, hospitals are overflowing with children suffering pneumonia or similar severe ailments. However, the Chinese government claims that no new pathogen has been found and that the surge in chest infections is due simply to the usual winter coughs and colds, aggravated by the lifting of stringent COVID-19 restrictions in December 2022. The World Health Organization (WHO) has dutifully repeated this reassurance, as if it learned nothing from Beijing’s disastrous cover-up of the COVID-19 outbreak.

There is an element of truth in Beijing’s assertion, but it is only part of the story. The general acceptance that China is not covering up a novel pathogen this time appears reassuring. In fact, however, China could be incubating an even greater threat: the cultivation of antibiotic-resistant strains of a common, and potentially deadly, bacteria.

Fears of another novel respiratory pathogen emerging from China are understandable after the SARS and COVID-19 pandemics, both of which Beijing covered up. Concerns are amplified by Beijing’s ongoing obstruction of any independent investigation into the origins of SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19—whether it accidentally leaked from the Wuhan lab performing dangerous gain-of-function research or derived from the illegal trade in racoon dogs and other wildlife at the now-infamous Wuhan wet-market.

Four years ago, during the early weeks of the COVID-19 outbreak, Beijing failed to report the new virus and then denied airborne spread. At pains to maintain their fiction, Chinese authorities punished doctors who raised concerns and prohibited doctors from speaking even to Chinese colleagues, let alone international counterparts. Chinese medical statistics remain deeply unreliable; the country still claims that total COVID-19 deaths sit at just over 120,000, whereas independent estimates suggest the number may have been over 2 million in just the initial outbreak alone. Now, Chinese doctors are once again being silenced and not communicating with their counterparts abroad, which suggests another potentially dangerous cover-up may be underway.

We don’t know exactly what is happening, but we can offer some informed guesses.

The microbe causing the surge in hospitalization of children is Mycoplasma pneumoniae, which causes M. pneumoniae pneumonia, or MPP. First discovered in 1938, the microbe was believed for decades to be a virus because of its lack of a cell membrane and tiny size, although in fact it is an atypical bacterium. These unusual characteristics makes it invulnerable to most antibiotics (which typically work by destroying the cell membrane). The few attempts to make a vaccine in the 1970s failed, and low mortality has provided little incentive for renewed efforts. Although MPP surges are seen every few years around the world, the combination of low mortality and difficult diagnostics has meant there is no routine surveillance.

Although MPP is the most common cause of community-acquired pneumonia in school children and teenagers, pediatricians such as myself refer to it as “walking pneumonia” because symptoms are relatively mild. Respiratory Syncytial Virus (RSV), influenza, adenoviruses, and rhinoviruses (also known as the common cold) all cause severe inflammation of the lungs and are far more common causes of emergency-room visits, hospitalization, and death in infants and young children. Why should MPP be acting differently now?

One contributing factor to the severity of this outbreak may be “immunity debt.” Around the globe, COVID-19 lockdowns and other non-pharmaceutical measures meant that children were less exposed to the usual range of pathogens, including MPP, for several years. Many countries have since seen rebound surges in RSV. Several experts agree with Beijing’s explanation that the combination of winter’s arrival, the end of COVID-19 restrictions, and a lack of prior immunity in children are likely behind the surging infections. Some even speculate that that substantial lockdown may have particularly compromised young children’s immunity, because exposure to germs in infancy is essential for immune systems to develop.

In China, MPP infections began in early summer and accelerated. By mid-October, the National Health Commission had taken the unusual step of adding MPP to its surveillance system. That was just after Golden Week, the biggest tourism week in China.

Infection by two diseases at the same time can make things worse. The usual candidates for coinfection in children—RSV and flu—have not previously caused comparable surges in pneumonia. One difference this time is COVID-19. It is possible that the combination of COVID-19 and MPP is particularly dangerous. Although adults are less susceptible to MPP due to years of exposure, adults hospitalized for COVID-19 who were simultaneously or recently coinfected by MPP had a significantly higher mortality rate, according to a 2020 study.

Infants and toddlers are immunologically naive to MPP, and unlike COVID-19, RSV, and influenza, there is no vaccine against MPP. It seems implausible that no child (or adult) has died from MPP, yet China has not released any data on mortality, or on extrapulmonary complications such as meningitis.

Most disturbing, and a fact being downplayed by Beijing, is that M. pneumoniae in China has mutated to a strain resistant to macrolides, the only class of antibiotics that are safe for children less than eight years of age. Beyond discouraging parents to start ad hoc treatment with azithromycin, the most common macrolide and the usual first-line antibiotic for MPP, Beijing has barely mentioned this fact. Even more worrying is that WHO has assessed the risk of the current outbreak as low on the basis that MPP is readily treated with antibiotics. Broader azithromycin resistance in MPP is common across the world, and China’s resistant strain rates in particular are exceptionally high. Beijing’s Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported macrolide resistance rates for MPP in the Beijing population between 90 and 98.4 percent from 2009 to 2012. This means there is no treatment for MPP in children under age eight.

Fears over a novel pathogen are already abating. After all, MPP is rarely lethal. But antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is. Responsible for 1.3 million deaths a year, AMR kills more people than COVID-19. No country is immune to this growing threat. Since China, where antibiotics are regularly available over the counter, leads the world in AMR, it is inconceivable that this issue hasn’t yet come up, particularly during WHO’s World AMR Awareness week, from Nov. 18 to Nov. 24.

Any infectious disease physician would want to know: Did WHO asked China the obvious question—what is the level of azithromycin resistance of M. pneumonia in the current outbreak—and include the answer in its risk assessment? Or did it ask about resistance to doxycycline and quinolones, antibiotics that can be used to treat MPP in adults? Even if WHO did ask, China isn’t telling, and WHO isn’t talking.

China’s silence isn’t surprising. Its antibiotic consumption per person is ten times that of the United States, and policies for AMR stewardship are predominantly cosmetic. While surveillance is China’s strong point, reporting is not.

Despite Spring Festival, the Chinese celebration of the Lunar New Year and another peak travel period, approaching in February 2024, WHO hasn’t advised any travel restrictions. It should have learned the danger of accepting Beijing’s statements at face value. Four years ago, Beijing’s delay enabled more than 200 million people to travel from and through Wuhan for Spring Festival. That helped COVID-19 go global. Since China’s AMR rates are already so high, importing AMR from other countries isn’t a major concern for China. Export is the issue, and China’s track record in protecting other countries is abysmal.

Rather than repeating the self-serving whitewashing coming from Beijing, WHO should be publicly pressing China about the threat of mutant microbes. Halting AMR is essential. Before antisepsis and antibiotics, surgery was a treatment of last resort. Without antibiotics, we lose 150 years of clinical and surgical advances. Within ten years, we are at risk of few antibiotics being effective. It may not be the novel virus that people were expecting, but the next pandemic is already here.

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Apparently Madeline Miller, of Song of Achilles fame, also still has Long Covid 3 years after catching Covid-19 in early 2020. Her op-ed is copied below (mostly under a Keep Reading link) for those who can't get past WaPo's paywall.

https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/2023/08/09/madeline-miller-long-covid-post-pandemic/

In 2019, I was in high gear. I had two young children, a busy social life, a book tour and a novel in progress. I spent my days racing between airports, juggling to-do lists and child care. Yes, I felt tired, but I come from a family of high-energy women. I was proud to be keeping the sacred flame of Productivity burning.

Then I got covid.

I didn’t know it was covid at the time. This was early February 2020, before the government was acknowledging SARS-CoV-2’s spread in the United States.

In the weeks after infection, my body went haywire. My ears rang. My heart would start galloping at random times. I developed violent new food allergies overnight. When I walked upstairs, I gasped alarmingly.

I reached out to doctors. One told me I was “deconditioned” and needed to exercise more. But my usual jog left me doubled over, and when I tried to lift weights, I ended up in the ER with chest pains and tachycardia. My tests were normal, which alarmed me further. How could they be normal? Every morning, I woke breathless, leaden, utterly depleted.

Worst of all, I couldn’t concentrate enough to compose sentences. Writing had been my haven since I was 6. Now, it was my family’s livelihood. I kept looking through my pre-covid novel drafts, desperately trying to prod my sticky, limp brain forward. But I was too tired to answer email, let alone grapple with my book.

When people asked how I was, I gave an airy answer. Inside, I was in a cold sweat. My whole future was dropping away. Looking at old photos, I was overwhelmed with grief and bitterness. I didn’t recognize myself. On my best days, I was 30 percent of that person.

I turned to the internet and discovered others with similar experiences. In fact, my symptoms were textbook — a textbook being written in real time by “first wavers” like me, comparing notes and giving our condition a name: long covid.

In those communities, everyone had stories like mine — life-altering symptoms, demoralizing doctor visits, loss of jobs, loss of identity. The virus can produce a bewildering buffet of long-term conditions, including cognitive impairment and cardiac failure, tinnitus, loss of taste, immune dysfunction, migraines and stroke, any one of which could tank quality of life.

For me, one of the worst was post-exertional malaise (PEM), a Victorian-sounding name for a very real and debilitating condition in which exertion causes your body to crash. In my new post-covid life, exertion could include washing dishes, carrying my children, even just talking with too much animation. Whenever I exceeded my invisible allowance, I would pay for it with hours, or days, of migraines and misery.

There was no more worshiping productivity. I gave my best hours to my children, but it was crushing to realize just how few hours there were. Nothing was more painful than hearing my kids delightedly laughing and being too sick to join them.

Doctors looked at me askance. They offered me antidepressants and pointed anecdotes about their friends who’d just had covid and were running marathons again.

I didn’t say I’d love to be able to run. I didn’t say what really made me depressed was dragging myself to appointments to be patronized. I didn’t say that post-viral illness was nothing new, nor was PEM — which for decades had been documented by people with myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome — so if they didn’t know what I was talking about, they should stop sneering and get caught up. I was too sick for that, and too worried.

I began scouring medical journals the way I used to close-read ancient Greek poetry. I burned through horrifying amounts of money on vitamins and supplements. At night, my fears chased themselves. Would I ever get relief? Would I ever finish another book? Was long covid progressive?

It was a bad moment when I realized that any answer to that last question would come from my own body. I was in the first cohort of an unwilling experiment.

When vaccines rolled out, many people rushed back to “normal.” My world, already small, constricted further.

Friends who invited me out to eat were surprised when I declined. I couldn’t risk reinfection, I said, and suggested a masked, outdoor stroll. Sure, they said, we’ll be in touch. Zoom events dried up. Masks began disappearing. I tried to warn the people I loved. Covid is airborne. Keep wearing an N95. Vaccines protect you but don’t stop transmission.

Few wanted to listen. During the omicron wave, politicians tweeted about how quickly they’d recovered. I was glad for everyone who was fine, but a nasty implication hovered over those of us who weren’t: What’s your problem?

Friends who did struggle often seemed embarrassed by their symptoms. I’m just tired. My memory’s never been good. I gave them the resources I had, but there were few to give. There is no cure for long covid. Two of my friends went on to have strokes. A third developed diabetes, a fourth dementia. One died.

I’ve watched in horror as our public institutions have turned their back on containment. The virus is still very much with us, but the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has stopped reporting on cases. States have shut down testing. Corporations, rather than improving ventilation in their buildings, have pushed for shield laws indemnifying them against lawsuits.

Despite the crystal-clear science on the damage covid-19 does to our bodies, medical settings have dropped mask requirements, so patients now gamble their health to receive care. Those of us who are high-risk or immunocompromised, or who just don’t want to roll the dice on death and misery, have not only been left behind — we’re being actively mocked and pathologized.

I’ve personally been ridiculed, heckled and coughed on for wearing my N95. Acquaintances who were understanding in the beginning are now irritated, even offended. One demanded: How long are you going to do this? As if trying to avoid covid was an attack on her, rather than an attempt to keep myself from sliding further into an abyss that threatens to swallow my family.

The United States has always been a terrible place to be sick and disabled. Ableism is baked into our myths of bootstrapping and self-reliance, in which health is virtue and illness is degeneracy. It is long past time for a bedrock shift, for all of us.

We desperately need access to informed care, new treatments, fast-tracked research, safe spaces and disability protections. We also need a basic grasp of the facts of long covid. How it can follow anywhere from 10 to 30 percent of infections. How infections accumulate risk. How it’s not anxiety or depression, though its punishing nature can contribute to both those things. How children can get it; a recent review puts it at 12 to 16 percent of cases. How long-haulers who are reinfected usually get worse. How as many as 23 million Americans have post-covid symptoms, with that number increasing daily.

Over three years later, I still have long covid. I still give my best hours to my children, and I still wear my N95. Thanks to relentless experimentation with treatments, I can write again, but my fatigue is worse. I recognize how fortunate I am: to have a caring partner and community, health insurance, good doctors (at last), a job I can do from home, a supportive publishing team, and wonderful readers who recommend my books. I’m grateful to all those who have accepted the new me without making me beg.

Some days, long covid feels manageable. Others, it feels like a crushing mountain on my chest. I yearn for the casual spontaneity and scope of my old life. I miss the friends and family who have moved on. I grieve those lost forever.

So how long am I going to do this? Until indoor air is safe for all, until vaccines prevent transmission, until there’s a cure for long covid. Until I’m not risking my family’s future on a grocery run. Because the truth is that however immortal we feel, we are all just one infection away from a new life.

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

These vaccines are the first that aren't rolled out by the U.S. government, and without funding that was directed to public health programs in the state of emergency, the outreach is nowhere near what it was at the height of the pandemic, said Lori T. Freeman, the CEO of the National Association of County and City Health Officials (NACCHO).

. . .

All insurers are legally required to cover the COVID-19 vaccine, and the federal government is stepping in to pay for vaccines for those who lack insurance through the Bridge Access Program. But insurers have been slow to implement these vaccines into their systems, leading to the stuttered rollout of the vaccine, said Dr. William Schaffner, an infectious disease and health policy professor at Vanderbilt University Medical Center

"There have already been people who have gone to their pharmacies and physician's offices looking for the vaccine and have discovered that they haven't been covered yet, so that means they're going to have to come back again," Schaffner told Salon in a phone interview. "A vaccine deferred is often a vaccine that is never received, unfortunately."

. . .

Nationally, COVID hospitalizations have been steadily increasing since June, along with the rise of Omicron variants like EG.5 (nicknamed "Eris") and FL.1.5.1 (nicknamed Fornax.) The vaccines are predicted to work against these strains of the SARS-CoV-2 virus, which evolves naturally in ways that will sometimes render vaccines next to useless. This is why new shots must be developed with some regularity.

. . .

Meanwhile, approximately 18 million Americans have developed long COVID and data suggests that number will continue to rise with more infections. Although the immunocompromised, elderly and people with other health conditions are the most vulnerable to severe infection, COVID-19 continues to be one of the top 10 leading causes of death for children in the U.S.

This rollout, including mRNA vaccines from Pfizer and Moderna, boosts immunity toward Omicron variants. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommended the shots for everyone 6 months and up and projects that this could prevent 400,000 hospitalizations and 40,000 deaths over the next two years.

. . .

Regardless, the question remains about how many people will take the new vaccines. Only about one in five people got last year's bivalent booster and one in four adults in the U.S. are completely unvaccinated, according to CDC data and the KFF survey. Although it has been improving over time, uptake has been particularly low in Black communities, in part because vaccination sites are disproportionately located in white neighborhoods but also because of decades of mistrust built up in response to prior medical malpractice.

Notably, just 6 million doses have been put aside for the uninsured through the Bridge Access Program, when at least 27 million people in the U.S. are uninsured, Freeman said. The demand for vaccines is a moving target that distributors are trying to balance without losing money, she added, especially because these vaccines have to be kept cold and take resources to store and administer.

-----

Absolutely get the vaccine! I recommend calling your insurance and pharmacy first though.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

from the article:

Key takeaways

There remains no clear explanation for why COVID-19, caused by SARS-CoV-2, can result in severe outcomes or death while other coronaviruses just cause common colds, or why COVID-19 symptoms persist after the coronavirus that causes it has been eliminated.

A UCLA-led research team has shown that fragments of the coronavirus may drive inflammation by mimicking the action of specific immune molecules in the body.

The findings could contribute to not only the understanding and treatment of COVID-19 but also efforts to detect coronaviruses with the potential to cause pandemics before they become widespread.

[...] The scientists found that certain viral protein fragments, generated after the SARS-CoV-2 virus is broken down into pieces, can mimic a key component of the body’s machinery for amplifying immune signals. Their discoveries suggest that some of the most serious COVID-19 outcomes can result from these fragments overstimulating the immune system, thereby causing rampant inflammation in widely different contexts such as cytokine storms and lethal blood coagulation.

[...]

“We saw that the various forms of debris from the destroyed virus can reassemble into these biologically active ‘zombie’ complexes,” Wong said. “It is interesting that the human peptide being imitated by the viral fragments has been implicated in rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis and lupus, and that different aspects of COVID-19 are reminiscent of these autoimmune conditions.”

The scientists also measured the entire set of genes expressed at the cellular level. By performing a comparison with internationally curated databases, the team found that the gene expression profile from cells exposed to SARS-CoV-2 “zombie” complexes closely resembled that from COVID-19 itself.

“What’s astonishing about the gene expression result is there was no active infection used in our experiments,” Wong said. “We did not even use the whole virus — rather only about 0.2% or 0.3% of it — but we found this incredible level of agreement that is highly suggestive.”

1 note

·

View note

Text

https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/2023/08/09/madeline-miller-long-covid-post-pandemic/?pwapi_token=eyJ0eXAiOiJKV1QiLCJhbGciOiJIUzI1NiJ9

Opinion Long covid has derailed my life. Make no mistake: It could yours, too.

August 9, 2023 at 5:45 a.m. EDT

(Scott Bakal for The Washington Post)

Madeline Miller, a novelist, is the author of “The Song of Achilles” and “Circe.”

In 2019, I was in high gear. I had two young children, a busy social life, a book tour and a novel in progress. I spent my days racing between airports, juggling to-do lists and child care. Yes, I felt tired, but I come from a family of high-energy women. I was proud to be keeping the sacred flame of Productivity burning.

Story continues below advertisement

I didn’t know it was covid at the time. This was early February 2020, before the government was acknowledging SARS-CoV-2’s spread in the United States.

In the weeks after infection, my body went haywire. My ears rang. My heart would start galloping at random times. I developed violent new food allergies overnight. When I walked upstairs, I gasped alarmingly.

I reached out to doctors. One told me I was “deconditioned” and needed to exercise more. But my usual jog left me doubled over, and when I tried to lift weights, I ended up in the ER with chest pains and tachycardia. My tests were normal, which alarmed me further. How could they be normal? Every morning, I woke breathless, leaden, utterly depleted.

Worst of all, I couldn’t concentrate enough to compose sentences. Writing had been my haven since I was 6. Now, it was my family’s livelihood. I kept looking through my pre-covid novel drafts, desperately trying to prod my sticky, limp brain forward. But I was too tired to answer email, let alone grapple with my book.

Some long-covid patients have brain struggles for at least two years

When people asked how I was, I gave an airy answer. Inside, I was in a cold sweat. My whole future was dropping away. Looking at old photos, I was overwhelmed with grief and bitterness. I didn’t recognize myself. On my best days, I was 30 percent of that person.

Story continues below advertisement

I turned to the internet and discovered others with similar experiences. In fact, my symptoms were textbook — a textbook being written in real time by “first wavers” like me, comparing notes and giving our condition a name: long covid.

In those communities, everyone had stories like mine: life-altering symptoms, demoralizing doctor visits, loss of jobs, loss of identity. The virus can produce a bewildering buffet of long-term conditions, including cognitive impairment and cardiac failure, tinnitus, loss of taste, immune dysfunction, migraines and stroke, any one of which could tank quality of life.

What is long covid? For the first time, a new study defines it.

For me, one of the worst was post-exertional malaise (PEM), a Victorian-sounding name for a very real and debilitating condition in which exertion causes your body to crash. In my new post-covid life, exertion could include washing dishes, carrying my children, even just talking with too much animation. Whenever I exceeded my invisible allowance, I would pay for it with hours, or days, of migraines and misery.

There was no more worshiping productivity. I gave my best hours to my children, but it was crushing to realize just how few hours there were. Nothing was more painful than hearing my kids delightedly laughing and being too sick to join them.

Story continues below advertisement

Doctors looked at me askance. They offered me antidepressants and pointed anecdotes about their friends who’d just had covid and were running marathons again.

I didn’t say I’d love to be able to run. I didn’t say what really made me depressed was dragging myself to appointments to be patronized. I didn’t say that post-viral illness was nothing new, nor was PEM — which for decades had been documented by people with myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome — so if they didn’t know what I was talking about, they should stop sneering and get caught up. I was too sick for that, and too worried.

I began scouring medical journals the way I used to close-read ancient Greek poetry. I burned through horrifying amounts of money on vitamins and supplements. At night, my fears chased themselves. Would I ever get relief? Would I ever finish another book? Was long covid progressive?

It was a bad moment when I realized that any answer to that last question would come from my own body. I was in the first cohort of an unwilling experiment.

When vaccines rolled out, many people rushed back to “normal.” My world, already small, constricted further.

Story continues below advertisement

Friends who invited me out to eat were surprised when I declined. I couldn’t risk reinfection, I said, and suggested a masked, outdoor stroll. Sure, they said, we’ll be in touch. Zoom events dried up. Masks began disappearing. I tried to warn the people I loved. Covid is airborne. Keep wearing an N95. Vaccines protect you but don’t stop transmission.

Few wanted to listen. During the omicron wave, politicians tweeted about how quickly they’d recovered. I was glad for everyone who was fine, but a nasty implication hovered over those of us who weren’t: What’s your problem?

Friends who did struggle often seemed embarrassed by their symptoms. I’m just tired. My memory’s never been good. I gave them the resources I had, but there were few to give. There is no cure for long covid. Two of my friends went on to have strokes. A third developed diabetes, a fourth dementia. One died.

Pico Iyer: Covid taught me what life might look like after death

I’ve watched in horror as our public institutions have turned their back on containment. The virus is still very much with us, but the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has stopped reporting on cases. States have shut down testing. Corporations, rather than improving ventilation in their buildings, have pushed for shield laws indemnifying them against lawsuits.

Despite the crystal-clear science on the damage covid-19 does to our bodies, medical settings have dropped mask requirements, so patients now gamble their health to receive care. Those of us who are high-risk or immunocompromised, or who just don’t want to roll the dice on death and misery, have not only been left behind — we’re being actively mocked and pathologized.

Story continues below advertisement

I’ve personally been ridiculed, heckled and coughed on for wearing my N95. Acquaintances who were understanding in the beginning are now irritated, even offended. One demanded: How long are you going to do this? As if trying to avoid covid was an attack on her, rather than an attempt to keep myself from sliding further into an abyss that threatens to swallow my family.

The United States has always been a terrible place to be sick and disabled. Ableism is baked into our myths of bootstrapping and self-reliance, in which health is virtue and illness is degeneracy. It is long past time for a bedrock shift, for all of us.

We desperately need access to informed care, new treatments, fast-tracked research, safe spaces and disability protections. We also need a basic grasp of the facts of long covid. How it can follow anywhere from 10 to 30 percent of infections. How infections accumulate risk. How it’s not anxiety or depression, though its punishing nature can contribute to both those things. How children can get it; a recent review puts it at 12 to 16 percent of cases. How long-haulers who are reinfected usually get worse. How as many as 23 million Americans have post-covid symptoms, with that number increasing daily.

More than three years later, I still have long covid. I still give my best hours to my children, and I still wear my N95. Thanks to relentless experimentation with treatments, I can write again, but my fatigue is worse. I recognize how fortunate I am: to have a caring partner and community, health insurance, good doctors (at last), a job I can do from home, a supportive publishing team, and wonderful readers who recommend my books. I’m grateful to all those who have accepted the new me without making me beg.

Story continues below advertisement

Some days, long covid feels manageable. Others, it feels like a crushing mountain on my chest. I yearn for the casual spontaneity and scope of my old life. I miss the friends and family who have moved on. I grieve those lost forever.

So how long am I going to do this? Until indoor air is safe for all, until vaccines prevent transmission, until there’s a cure for long covid. Until I’m not risking my family’s future on a grocery run. Because the truth is that however immortal we feel, we are all just one infection away from a new life.

Expert opinions on covid guidance

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mastani's Guide to Monkeypox

Disclaimer: I'm not an epidemiologist or a physician - I'm just someone well versed with microbiology and diseases. That being said, here is what I know/what I'm doing about monkeypox. A big note beforehand though - this is not a queer disease. We must prevent spread to high risk populations. Even if you are not high risk, you are no more than two steps away from someone who is.

This information was aggregated as of August 28th, 2022. Remember - science is always learning more, so some information may become outdated.

What is it? - a poxvirus. Similar to coxpox or variola/smallpox, monkeypox is a double stranded DNA virus. Double stranded DNA is stable genetic material (especially as compared to SARS-CoV-2, which is an RNA virus).

How does it infect? - Mechanistically, I can't find a consensus. However, this article (warning, it's written for immunologists, not for the general public) suggests poxviruses evades immune responses by modifying recognition proteins.

How does it spread? - Monkeypox is viable in rashes and bodily fluid. It can be spread through skin-to-infected skin contact, contact with mucous membranes (eyes, nose, mouth, and vagina), and contact with bodily fluids, like breathing in/ingesting saliva. It can spread from humans to animals. Since this virus is stable, surfaces (especially soft and porous surfaces - like clothes and couches) can hold viable virus. To summarize, you can get monkeypox by:

- skin to rash contact

- skin to scab contact

- skin to infected cloth contact (i.e. laundering soiled sheets)

- sex with an infected person, regardless of sexuality or gender

- skin to infected surface contact (i.e. frequently touched surfaces)

- 3+ hours, no mask, within 6> feet (droplet spread)

How do you protect yourself?

- Maintain your skin barrier as best you can. This means frequent moisturizing, covering injuries/broken skin (i.e. cuts, eczema). A solid skin barrier is an EXCELLENT defense.

- Try to avoid extensive touching of folks you don't know/wear protective clothes if you must. This includes items that they spend a lot of time with.

- Disinfect surfaces - refer to this list for disinfectants that work and follow instructions. Monkeypox does not survive at high humidity , sunlight, and high temperatures (think near tropic temperatures), but is stable at room temperature for a while (current estimates are at 15 days if undisturbed).

- Wash/Sanitize (70% alcohol or more) your hands often.

- Watch for symptoms and see a provider ASAP for unexplained rashes.

- Get vaccinated if you can. The current guidelines are here (AUG/22/2022), but the next phase opens the vaccine up to anyone. Old smallpox vaccines do work, but talk to your provider about getting this one. If you have a immunocompromising condition (including eczema!), take the JYNNEOS vaccine over the ACAM2000.

- Mask up. If you took off your mask for COVID-19, put it back on.

- Do not touch your eyes, nose, mouth, or broken skin without washing your hands.

What do I do if I'm exposed?

- Get vaccinated ASAP. The vaccine does work as post-exposure prophylaxis.

- Communicate with your local health department. You may have to isolate for 21 days.

- Watch for symptoms (they may be mild!)

- Wear a mask around others and insist that others mask around you.

What are the symptoms? - There are a few stages for symptoms. Here is the most common presentation, but if you're ever unsure, see a physician. Keep in mind, monkeypox rash can range from 1 bump to 100s and last about a month.

1. Incubation (5 days - 3 weeks): Before symptoms starts. It is unclear if people are infective during this time.

2. Prodrome (1 - 2 days if at all): Fever, chills, swollen lymph nodes, sore throat, exhaustion, headache, cough. Think the flu, or a bad cold. People may be infective at this time, but it is unclear.

3. Enanthem (1 day): Sores inside the mouth or on the tongue. People are definitely infective at this time. From here on out, you may experience pain and itching.

4. Macules (1-2 days): Flat lesions (re: abnormal skin) spread across the face and to the limbs/other places.

5. Papules (1-2 days): The rash becomes rasied, easy to individually circle, and feel firm.

6. Vesicles (1-2 days): The bumps fill with clear fluid.

7. Pustules (5-7 days): The bumps become cloudy or pus filled. They may develop a spot or divot.

8. Scabs (~7 days): The bumps become crusty and scabby. They will fall off on their own and may leave scars. After all scabs are gone, people are not infective.

Can I recieve medication? - Yes, there are antivirals that help. However, even without medication, monkeypox usually resolves on its own after a month.

What do I do to clean my place after I/someone I live with gets infected:

- Clean surfaces with the disinfectants from earlier. Pay close attention to the instructions. Bleach also works, but again, adhere to the instructions.

- Launder soiled clothes and linens with extreme care. A wash cycle will render monkeypox dead, but the transfer of items to the washer can put you in contact with infective particles.

Mastani, what are YOU doing? - as someone who is often in the hospital, has to be in public, and lives with someone, this is what we do. Keep in mind, I'm a bit germ-sensitive, so some of this may be overkill.

- Change clothes when we get home. I take a full shower, but my partner just changes since they work in a non-hospital setting and are rarely in contact with a lot of people.

- Clean our home once a week with disinfectants listed in the link above.

- Spray our phones when we get home with 70%+ isopropyl alochol (Note: make sure your phone is off while doing this!!)

- Wipe down our electronics similarly (again, more for me than them)

- Avoid touching folks we don't know well/ask our friends to keep a close eye on symptoms.

- Double mask everywhere. I wear a KN95 + surgical mask, they wear a KN95 + cloth mask.

- Wipe down public surfaces before sitting at them. We keep wipes in our bags.

- Wipe down our groceries/wash the produce as soon as we get home. (we don't know transmission rates of public surfaces yet, so extra precaution)

- Wash our hands as soon as we come in.

- Take extra caution using public bathrooms (try to avoid too much butt to seat without a barrier/wiping it down).

- Take off our shoes when we get home.

- Sanitize/Wash our hands before eating anywhere, including home.

- We have a quarantine room/pack ready to go on the chance one of us has to quarantine.

Underlined phrases are links. If you have questions, I will answer them to the best of my ability. However, I am balancing school, new monkeypox information, and anxiety at all times. I may not have an answer. When in doubt, seek medical advice from an epidemiologist or physician.

Knowledge is power. Be safe, be cautious.

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

For anyone whose brain is stuck in a loop demanding to know why, this may well be the culprit.

When I’d heard that he’d gotten COVID in August, 2022, my fist thought was, Oh god, what if we lose him?

When he came back from his second bout a year later to perform the Izora Finalo, I thought we were in the clear.

SARS-Cov-2 is not, nor has ever been, “just a cold.” Please take care. ❤️🩹

1 note

·

View note

Note

As a fellow biology nerd I can pretty much see why you decided to become a virologist, but I'm curious about how you first came across the fascination from such puzzling beings. Feel free to ramble if ya wish! :) I would love some viruses and viral diseases facts

It was kind of an accident! I was working at a vet clinic with doctors that were great with their patients but not so great with their staff and I kinda just started applying everywhere. After I applied to the lab, they invited me in for an interview and actually asked me to apply for a different position instead…which I didn’t get at that point, but they did call me back the second another position opened up a few weeks later. I didn’t really know anything about viruses (and regularly googled “what even IS a virus” at work…😅) and felt a LOT of imposter’s syndrome when I first started. But I enjoyed the lab work and the more I researched and worked the more I came to love virology and infectious diseases. I started out working mostly with influenza, then I would run standard assays for the NIH to test antivirals against several viruses at different times like Zika, Usutu, Dengue, Japanese encephalitis virus, Enterovirus D68 and 71, RSV, etc. and I did some work with bovine (cow) viruses. And then when COVID hit, we all just pivoted. I don’t think drug sponsors sent in antivirals to test for months at the beginning 😂 I kinda started to miss Zika 😂 but working with human coronaviruses was pretty cool! We started doing testing against 5 human coronaviruses around that time (there are like 7 known ones with more suspected, but 2 don’t grow in cell culture—at least not very easily. So we just did the 5–two “common cold” coronaviruses and then MERS, SARS, and SARS-CoV-2)

I definitely miss lab work. I’ve enjoyed trying to stay on top of the research and I’m excited to eventually move onto more public health centered work (when I can find a job), but I’m constantly trying to find epidemiology teams that work primarily with viruses because I think virology will always have a big chunk of my heart—and it was honestly just kind of an accident that I ended up in the lab at all! I had another professor trying to recruit me to be his lab manager for an animal reproduction lab trying to learn how to prevent early embryonic death and I would have loved that but he took MONTHS to finally get the job figured out to try to offer it to me and by that point I decided I liked viruses so I stayed where I was. When covid hit, I realized I was already doing the work for a thesis anyway, so that’s when I applied for my master’s program. I went master’s of public health instead of master’s of science because the MPH program was mostly online and I knew there was a chance we’d have to move before I finished, but I think it was definitely the right choice!!

1 note

·

View note

Text

Long covid has derailed my life. Make no mistake: It could yours, too.

By Madeline Miller • August 9, 2023

Madeline Miller, a novelist, is the author of “The Song of Achilles” and “Circe.”

In 2019, I was in high gear. I had two young children, a busy social life, a book tour and a novel in progress. I spent my days racing between airports, juggling to-do lists and child care. Yes, I felt tired, but I come from a family of high-energy women. I was proud to be keeping the sacred flame of Productivity burning.

Then I got covid.

I didn’t know it was covid at the time. This was early February 2020, before the government was acknowledging SARS-CoV-2’s spread in the United States.

In the weeks after infection, my body went haywire. My ears rang. My heart would start galloping at random times. I developed violent new food allergies overnight. When I walked upstairs, I gasped alarmingly.

I reached out to doctors. One told me I was “deconditioned” and needed to exercise more. But my usual jog left me doubled over, and when I tried to lift weights, I ended up in the ER with chest pains and tachycardia. My tests were normal, which alarmed me further. How could they be normal? Every morning, I woke breathless, leaden, utterly depleted.

Worst of all, I couldn’t concentrate enough to compose sentences. Writing had been my haven since I was 6. Now, it was my family’s livelihood. I kept looking through my pre-covid novel drafts, desperately trying to prod my sticky, limp brain forward. But I was too tired to answer email, let alone grapple with my book.

When people asked how I was, I gave an airy answer. Inside, I was in a cold sweat. My whole future was dropping away. Looking at old photos, I was overwhelmed with grief and bitterness. I didn’t recognize myself. On my best days, I was 30 percent of that person.

I turned to the internet and discovered others with similar experiences. In fact, my symptoms were textbook — a textbook being written in real time by “first wavers” like me, comparing notes and giving our condition a name: long covid.

In those communities, everyone had stories like mine: life-altering symptoms, demoralizing doctor visits, loss of jobs, loss of identity. The virus can produce a bewildering buffet of long-term conditions, including cognitive impairment and cardiac failure, tinnitus, loss of taste, immune dysfunction, migraines and stroke, any one of which could tank quality of life.

For me, one of the worst was post-exertional malaise (PEM), a Victorian-sounding name for a very real and debilitating condition in which exertion causes your body to crash. In my new post-covid life, exertion could include washing dishes, carrying my children, even just talking with too much animation. Whenever I exceeded my invisible allowance, I would pay for it with hours, or days, of migraines and misery.

There was no more worshiping productivity. I gave my best hours to my children, but it was crushing to realize just how few hours there were. Nothing was more painful than hearing my kids delightedly laughing and being too sick to join them.

Doctors looked at me askance. They offered me antidepressants and pointed anecdotes about their friends who’d just had covid and were running marathons again.

I didn’t say I’d love to be able to run. I didn’t say what really made me depressed was dragging myself to appointments to be patronized. I didn’t say that post-viral illness was nothing new, nor was PEM — which for decades had been documented by people with myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome — so if they didn’t know what I was talking about, they should stop sneering and get caught up. I was too sick for that, and too worried.

I began scouring medical journals the way I used to close-read ancient Greek poetry. I burned through horrifying amounts of money on vitamins and supplements. At night, my fears chased themselves. Would I ever get relief? Would I ever finish another book? Was long covid progressive?

It was a bad moment when I realized that any answer to that last question would come from my own body. I was in the first cohort of an unwilling experiment.

When vaccines rolled out, many people rushed back to “normal.” My world, already small, constricted further.

Friends who invited me out to eat were surprised when I declined. I couldn’t risk reinfection, I said, and suggested a masked, outdoor stroll. Sure, they said, we’ll be in touch. Zoom events dried up. Masks began disappearing. I tried to warn the people I loved. Covid is airborne. Keep wearing an N95. Vaccines protect you but don’t stop transmission.

Few wanted to listen. During the omicron wave, politicians tweeted about how quickly they’d recovered. I was glad for everyone who was fine, but a nasty implication hovered over those of us who weren’t: What’s your problem?

Friends who did struggle often seemed embarrassed by their symptoms. I’m just tired. My memory’s never been good. I gave them the resources I had, but there were few to give. There is no cure for long covid. Two of my friends went on to have strokes. A third developed diabetes, a fourth dementia. One died.

I’ve watched in horror as our public institutions have turned their back on containment. The virus is still very much with us, but the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has stopped reporting on cases. States have shut down testing. Corporations, rather than improving ventilation in their buildings, have pushed for shield laws indemnifying them against lawsuits.

Despite the crystal-clear science on the damage covid-19 does to our bodies, medical settings have dropped mask requirements, so patients now gamble their health to receive care. Those of us who are high-risk or immunocompromised, or who just don’t want to roll the dice on death and misery, have not only been left behind — we’re being actively mocked and pathologized.

I’ve personally been ridiculed, heckled and coughed on for wearing my N95. Acquaintances who were understanding in the beginning are now irritated, even offended. One demanded: How long are you going to do this? As if trying to avoid covid was an attack on her, rather than an attempt to keep myself from sliding further into an abyss that threatens to swallow my family.

The United States has always been a terrible place to be sick and disabled. Ableism is baked into our myths of bootstrapping and self-reliance, in which health is virtue and illness is degeneracy. It is long past time for a bedrock shift, for all of us.

We desperately need access to informed care, new treatments, fast-tracked research, safe spaces and disability protections. We also need a basic grasp of the facts of long covid. How it can follow anywhere from 10 to 30 percent of infections. How infections accumulate risk. How it’s not anxiety or depression, though its punishing nature can contribute to both those things. How children can get it; a recent review puts it at 12 to 16 percent of cases. How long-haulers who are reinfected usually get worse. How as many as 23 million Americans have post-covid symptoms, with that number increasing daily.

More than three years later, I still have long covid. I still give my best hours to my children, and I still wear my N95. Thanks to relentless experimentation with treatments, I can write again, but my fatigue is worse. I recognize how fortunate I am: to have a caring partner and community, health insurance, good doctors (at last), a job I can do from home, a supportive publishing team, and wonderful readers who recommend my books. I’m grateful to all those who have accepted the new me without making me beg.

Some days, long covid feels manageable. Others, it feels like a crushing mountain on my chest. I yearn for the casual spontaneity and scope of my old life. I miss the friends and family who have moved on. I grieve those lost forever.

So how long am I going to do this? Until indoor air is safe for all, until vaccines prevent transmission, until there’s a cure for long covid. Until I’m not risking my family’s future on a grocery run. Because the truth is that however immortal we feel, we are all just one infection away from a new life.

0 notes