#Shanewis

Text

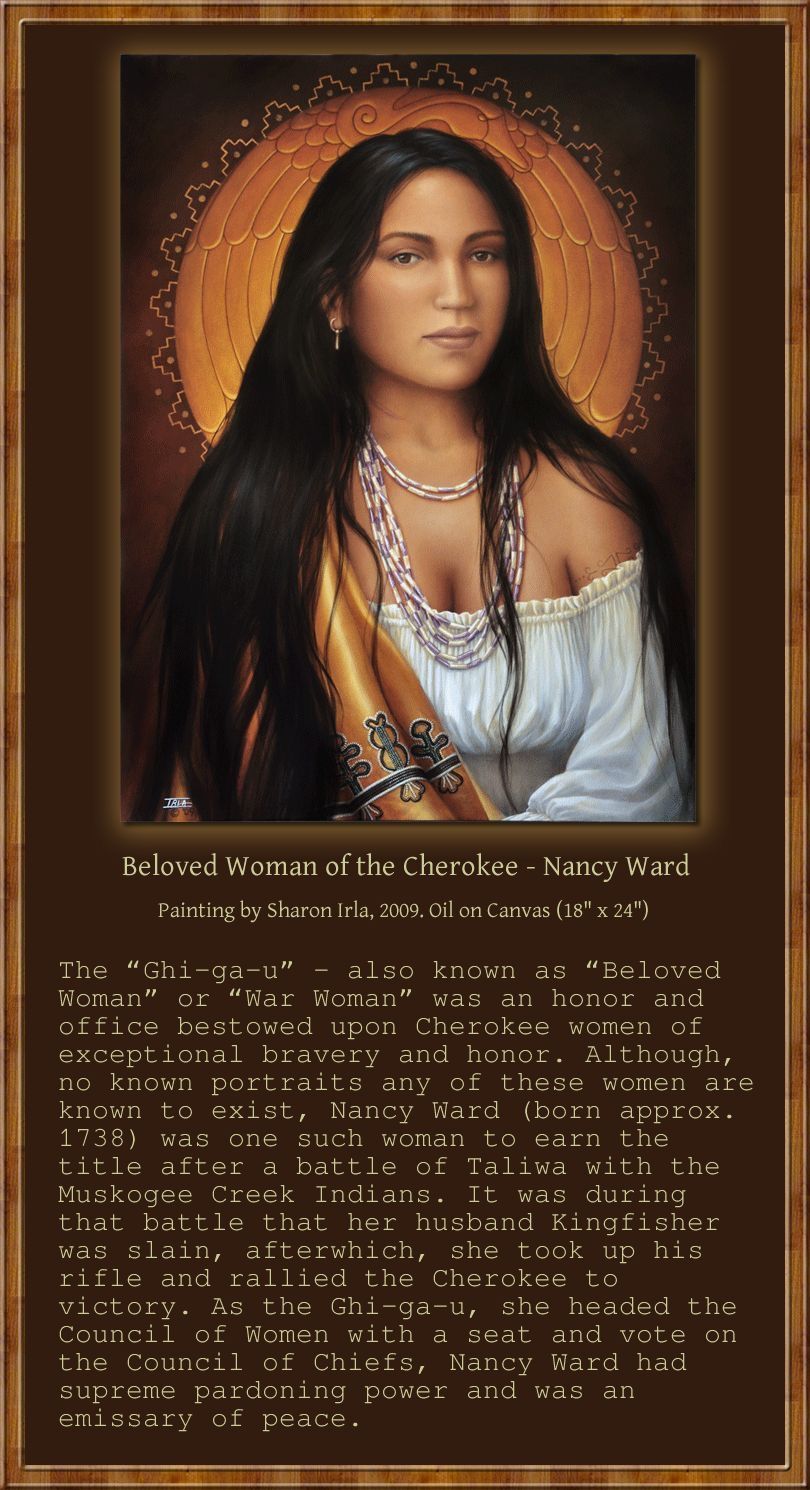

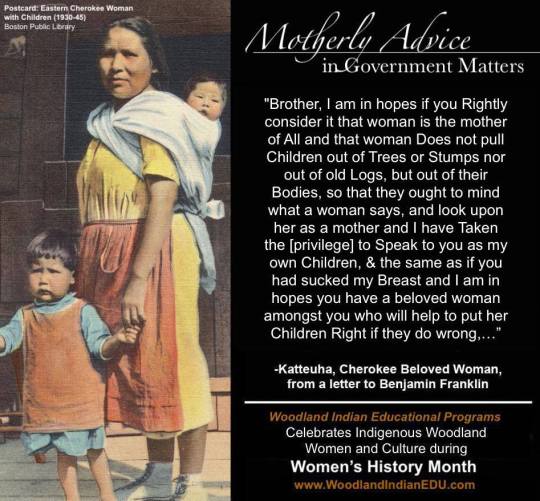

❣️♀️Beloved Woman

Cherokee Beloved Woman Nancy Ward

Nancy Ward, or Nan'yehi (nan yay hee), is the most famous Cherokee Beloved Woman. The role of Beloved Woman, Ghigau (Ghee gah oo), was the highest a Cherokee woman could aspire to. A Ghigau had a voice and vote in General Council, leadership of the Woman's Council, the honor of preparing and serving the ceremonial Black Drink, the duty of ambassador of peace-negotiator, and the right to save the life of a prisoner already condemned to execution.

The Native American Cherokee

The word Cherokee is believed to have evolved from a Choctaw word meaning "Cave People." It was picked up and used by Europeans and eventually accepted and adopted by Cherokees. Traditionally, the people now known as Cherokee refer to themselves as aniyun-wiya, a name usually translated as "the Real People," sometimes "the Original People."

The Role of the Cherokee Woman

The Cherokee were matrilineal with a complex society structure. Clan kinship followed the mother's side of the family. The children grew up in the mother's house, and it was the duty of an uncle on the mother's side to teach the boys how to hunt, fish, and perform certain tribal duties. The women owned the houses and their furnishings. Marriages were carefully negotiated, but if a woman decided to divorce her spouse, she simply placed his belongings outside the house. Cherokee women also worked hard. They cared for the children, cooked, tended the house, tanned skins, wove baskets, and cultivated the fields. Men helped with some household chores like sewing, but they spent most of their time hunting.

Women in the Cherokee society were equal to men. This privilege led an Irishman named Adair who traded with the Cherokee from 1736-1743 to accuse the Cherokee of having a "petticoat government."

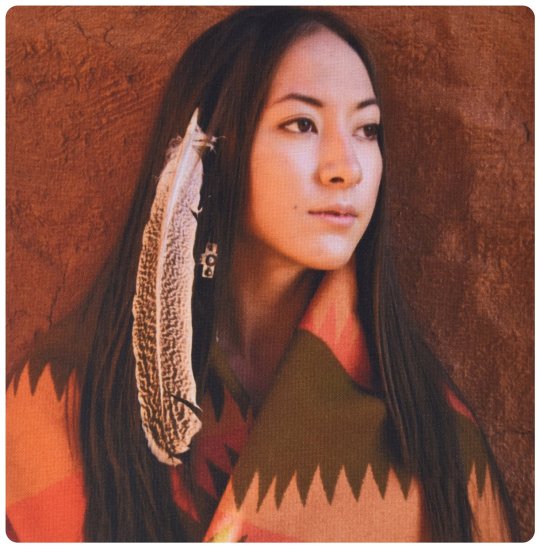

Princess Tsianina Red Feather

Tsianina Red Feather was not a "Princess." The Cherokee never had princesses. This is a concept based on European folktales and has no reality in Cherokee history and culture. Beloved women and high ranking women in a clan were treated with such reverence, that Europeans assumed they were some type of royalty.

Red Feather was born Florence Tsianina Evans on December 13,1882 in Eufallia (Oklahoma Territory) to Creek and Cherokee parents. All her 9 siblings were musical, but she was the one who stood out.

At age 14, she went to Denver to be trained to sing. There, she met the composer Charles Cadman and began touring with him at 16. She became a mezzo soprano virtuoso. While touring the United States, Canada, Paris and London, she wore native dress, braided her hair and wore a headband she beaded herself.

In 1918, she and Cadman debuted "Shanewis" (The Robin Woman) at the Metropolitan Opera; the cast received 22 curtain calls. Cadman based the opera on Native American stories told by Redfeather. Although this opera had many firsts, it became the first contemporary opera to be performed for a 2nd season at the Met.

The Robin Woman: Shanewis, 1918 - an opera in one act and two scenes by American composer Charles Cadman and Tsianina Redfeather Blackstone. Cadman called the work an "American opera."

Photo is Miss Anna Trainor, who later became Mrs. Anna Bennett. She was only Cherokee on her mother's side, but because it was the woman's bloodlines that determined kinship, she was considered Cherokee.

The title Ghigau also translates to "War Woman," and Nan'yehi (Nancy Ward) earned the title by taking up her husband's gun when he was slain in a battle against the Creeks and leading her people to victory. Another War Woman, Cuhtahlatah, won honor during the American Revolutionary period by leading Cherokee warriors to victory after her husband fell. She later joined in a vigorous war dance carrying her tomahawk and gun.

It was important to the Cherokee that their losses be compensated with the same number of prisoners, scalps, or lives. Woman led in the execution of prisoners. It was their right and responsibility as mothers. Women had the right to claim prisoners as slaves, adopt them as kin, or condemn them to death "with the wave of a swan's wing."

In the Cherokee society your Clan was your family. Children belonged to the entire Clan, and when orphaned were simply taken into a different household. Marriage within the clan was strictly forbidden, or pain of death. Marriages were often short term, and there was no punishment for divorce or adultery. Cherokee women were free to marry traders, surveyors, and soldiers, as well as their own tribesmen.

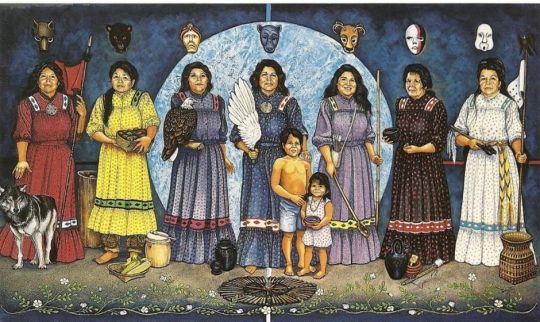

7 Cherokee Clans - L to R: 1.Wolf Clan 2.Long Hair Clan 3.Red Tail Hawk Clan 4.Blue Holly Clan 5.Deer Clan 6.Paint Clan 7.Wild Potato Clan

Cherokee girls learned by example how to be warriors and healers. They learned to weave baskets, tell stories, trade, and dance. They became mothers and wives, and learned their heritage. The Cherokee learned to adapt, and the women were the core of the Cherokee.

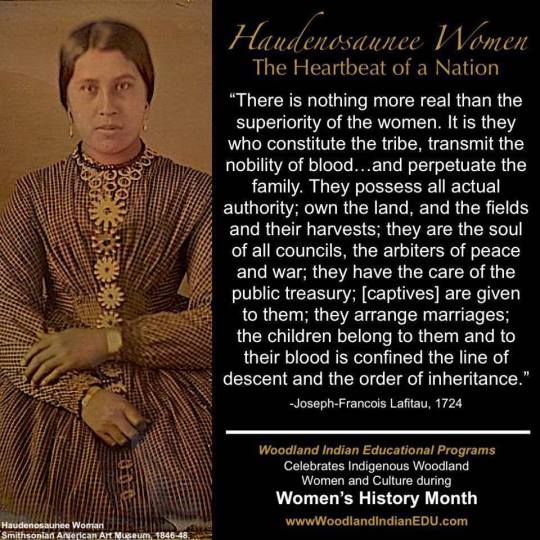

Other indigenous nations were were matrilineal. Women of the six nations Iroquois confederacy (Haudenosaunee) had a political voice on this land for at least 1,000 years.

The male chiefs who are the representatives of their clan in the confederacy of the Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga, Seneca, and Tuscarora Nations are selected, held in office, and removed by women – the clan mothers. Founded on the shores of Onondaga Lake, this oldest continuing democracy in the world is based on a system of gender balance. The position of the chief is vested in the clan mother, who is the eyes and ears of the people, while the chief is her voice. Women were “the great power among the clan, as everywhere else,” Elizabeth Cady Stanton marveled. Lucretia Mott wrote about listening to “speeches of their chiefs, women as well as men” (clan mothers and chiefs) when she visited the Cattaraugus Seneca community during the summer of 1848 before Mott, with Stanton and Quaker friends, organized the Seneca Falls convention.

In other words, the Beloved and Haudenosaunee women influenced the Women's Suffrage Movement.

#original people#cherokee#native american#Beloved Woman#nancy ward#choctaw#Shanewis#clan#indigenous#women#katteuha#haudenosaunee woman#Iroquois confederacy#suffragette#women's suffrage#Elizabeth Cady Stanton#Lucretia Mott#Seneca Falls#clans#society#culture

227 notes

·

View notes

Text

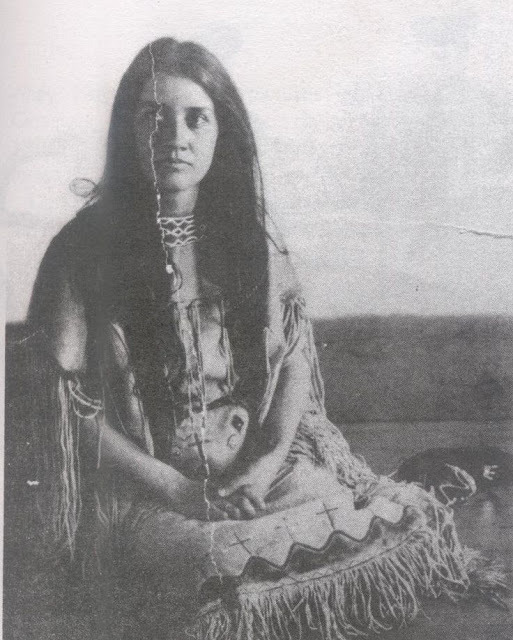

Tsianina Redfeather, a famous Creek/Cherokee singer and performer. Early 1900s. Source - Denver Public Library.

Tsianina Redfeather Blackstone (December 13, 1882 – January 10, 1985) was a Muscogee singer, performer, and Native American activist, born in Eufaula, Oklahoma, then within the Muscogee Nation. She was born to Cherokee and Creek parents and stood out from her 9 siblings musically. From 1908 she toured regularly with Charles Wakefield Cadman, a composer and pianist who gave lectures about Native American music that were accompanied by his compositions and her singing. He composed classically based works associated with the Indianist movement. They toured in the United States and Europe.

She collaborated with him and Nelle Richmond Eberhart on the libretto of the opera Shanewis (or "The Robin Woman," 1918), which was based on her semi-autobiographical stories and contemporary issues for Native Americans. It premiered at the Metropolitan Opera. Redfeather sang the title role when the opera was on tour, making her debut when the work was performed in Denver in 1924, and also performing in it in Los Angeles in 1926.

After her performing career, she worked as an activist on Indian education, co-founding the American Indian Education Foundation. She also supported Native American archeology and ethnology, serving on the Board of Managers for the School of American Research founded in Santa Fe by Alice Cunningham Fletcher.

0 notes

Photo

Paul Shearer Althouse (December 2, 1889 – February 6, 1954) was an American opera singer. He began his career as a lyric tenor with a robust Italianate sound, in roles including Cavaradossi in Tosca, Pinkerton in Madama Butterfly, and Turiddu in Cavalleria rusticana. He later branched out into the dramatic tenor repertoire, finding success in portraying Wagnerian heroes. He sang with the Metropolitan Opera in New York City for 30 years. Althouse sang as a boy soprano in the choir of his hometown's Episcopal Church. He received his first voice lessons at the church from Evelyn Essick. He studied music at Bucknell University and then singing privately with Perley Dunn Aldrich in Philadelphia and Oscar Saenger and Percy Rector Stevens in New York City. He made his professional opera debut with the Philadelphia-Chicago Grand Opera Company as Gounod's Faust in an out of town engagement in New York City. Althouse debuted at the Metropolitan opera in a small role in The Magic Flute on November 23, 1912. His first major assignment with that company came on March 19, 1913 as Grigory in the United States premiere of Mussorgsky's Boris Godunov. Althouse remained at the Met through 1920, during which time he participated in the world premieres of Victor Herbert's Madeleine (François, 1914), Umberto Giordano’s Madame Sans-Gêne (Neipperg, 1915), Reginald de Koven's The Canterbury Pilgrims (Squire, 1917), Charles Wakefield Cadman’s Shanewis (Lionel, 1918) and Joseph Carl Breil’s The Legend (Stephen, 1919). His other roles at the house during these years included: Cavaradossi in Tosca, Froh in Das Rheingold, the Italian Singer in Der Rosenkavalier, Nicias in Thaïs, Pinkerton in Madama Butterfly, Turiddu in Cavalleria Rusticana, Uin-San-Lui in Franco Leoni's L'Oracolo, Walther in Tannhäuser, Vladimir in Prince Igor, and the title role in Oberon. After a five-year absence from opera, he appeared as Faust in San Francisco in 1925. He making his debut with the company as Avito in L'amore dei tre re. He also sang Samson in Samson and Delilah and Don José in Carmen with the company that year. He visited the Bayreuth Festival in the summer of 1925, and decided he wanted to train as a Heldentenor. He made his first foray into that heavier repertoire at the PCOC as Tristan in Tristan und Isolde on March 25, 1926. He continued to perform with the PGOC annually through 1929 in such roles as Canio in Pagliacci, Pinkerton, Radamès in Aida, Siegmund in Die Walküre, and Walther von Stolzing in Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg. In 1929 Althouse made his first appearances at major European opera houses, appearing at the Berlin State Opera, the Staatsoper Stuttgart, and the Royal Swedish Opera, mainly as Turiddu and as Canio. That same year he also performed in concerts with the Eaton Choral Society in Toronto. In 1930 he sang at the Chicago Civic Opera as Tannhauser and Siegmund. In 1931 he sang the title role in Stravinsky's Oedipus rex with the Philadelphia Orchestra under conductor Leopold Stokowski. He sang Tristan and Siegfried in concert with the orchestra the following year. In 1933 he sang Tristan in San Francisco. Returned to the Met on February 26, 1933 for a special concert honoring Giulio Gatti-Casazza. He next appeared on stage as Siegmund in Die Walküre on February 3, 1934 with Frida Leider as Brünnhilde. He appeared annually at Met for the next six years, singing such roles as Aegisth in Elektra, Loge in Das Rheingold, Pinkerton, Tristan, Walther von Stolzing, and the title role in Lohengrin. His last appearance at the Met was in a concert evening on February 18, 1940.

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Sophie Braslau (August 16, 1892 – December 22, 1935) was a contralto prominent in United States opera, starting with her debut in New York City's Metropolitan Opera in 1913 when she was 21. As a child, Braslau studied piano. Her vocal talent was discovered by voice teacher Arturo Buzzi-Peccia, a family friend, who heard the little girl humming while she practiced piano. Braslau herself claimed to be inspired to a singing career after hearing Alma Gluck, another student of Buzzi-Peccia. She studied with Buzzi-Peccia for three years and then with a number of other instructors. She auditioned for New York's Metropolitan Opera in April 1913, was promptly signed to a contract, and debuted in November of that year. Her first leading role was in 1918 as Shanewis. Braslau also sang in concert and toured widely and frequently, first in the United States and Canada, then in Europe in the 1920s, using a repertoire which included works in English, French, German, Italian, Russian, and Yiddish. She retired from her full-time opera career in the late 1920s and performed very little as frail health brought her life to an early close. Sophie Braslau died of cancer on December 22, 1935 in Manhattan. At her funeral Sergei Rachmaninoff was an honorary pallbearer; the eulogy was delivered by Olin Downes, music critic for The New York Times.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Marie Sundelius (4 February 1882 - 27 June 1958) was a Swedish-American classical soprano. She sang for many years with the Metropolitan Opera in New York City and later embarked on a second career as a celebrated voice teacher in Boston. Sundelius began performing professionally in concerts and oratorios in Boston in 1910, making her debut performance under the baton of Karl Muck. In December 1915 she came to New York City for the first time to sing as a soloist in the world premiere of Marco Enrico Bossi's Jeanne d'Arc with the Oratorio Society of New York. The performance was attended by Giulio Gatti-Casazza, the General Manager of the Metropolitan Opera, who immediately approached her afterwards with an offer to join the roster of singers at the Met. She accepted, and made her opera debut at the "Old Met" on November 25, 1916 as the First Priestess in Christoph Willibald Gluck's Iphigénie en Tauride with Melanie Kurt in the title role and Artur Bodanzky conducting. Sundelius remained committed to the Metropolitan Opera up through 1923, although she returned to the house periodically as a guest artist up through 1928. Her roles at the house included Anna in Loreley, the Artichoke Vendor in Louise, the Cat in L'oiseau bleu, the Celestial Voice in Don Carlo, Diane in Iphigénie en Tauride, Elvira in L'italiana in Algeri, a Flower Maiden in Parsifal, Gerhilde, Gutrune, and Helmwige in The Ring Cycle, Inès in L'Africaine, Jemmy in William Tell, the Mermaid in Oberon, Micaela in Carmen, Musetta in La bohème, Nedda in Pagliaci, Pomone in La reine Fiammette, Samaritana in Riccardo Zandonai's Francesca da Rimini, Sophie in Der Rosenkavalier, the Voice of a Priestess in Aida, and the title role in The Golden Cockerel. She also created roles in several world premieres at the Met, including Johanna in Reginald De Koven's The Canterbury Pilgrims (1917), Amy Everton in Charles Wakefield Cadman's Shanewis (1918), the Monitress in Suor Angelica (1918), and Ciesca in Gianni Schicchi (1918). Her last performance in a staged opera at the Met was as Marguerite in Faust on April 1, 1925 with Edward Johnson in the title role. She returned a few more times to the Met for concert performances, making her final and 248th appearance at the house on March 11, 1928.[5] While at the Met, Sundelius occasionally toured the United States in productions with the Scotti Opera Company. After she left New York in 1925, she went to Europe where she was committed to the Royal Swedish Opera in Stockholm through 1927. She also toured Europe, performing in concerts and recitals. In 1929-1930 she sang with the Philadelphia Civic Opera Company and the Chicago Civic Opera.

2 notes

·

View notes