Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

155 years ago June 26.1870 Richard Wagner „Die Walküre“ premiered in Munich. Here we see a series of original Postcards from a performance in Berlin 1906. This Opera is still one of the composer most popular operas until today. Also The pic shows Ellen Gulbranson as Brünnhilde, Alois Burgenstaller as Siegmund and Rosa Sucher as Sieglinde. Bayreuth, 1895(?)

#classical music#opera#music history#bel canto#composer#classical composer#aria#classical studies#maestro#chest voice#Richard Wagner#Die Walküre#Postcard#classical musician#classical musicians#classical history#history of music#historian of music#musician#musicians#diva#prima donna#Golden Age of Opera#Golden Days of Opera

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

From From The art of the prima donna and concert singer (1923) by Frederick H. Martens (1874-1932):

Emma Calvé the great dramatic soprano, whose recent book, My Life, offers so fascinating a record of her career, is an artist willing to place some of the rich treasure of her experience at the service of the serious student. During a pleasant morning hour in the Hotel Savoy, before the daily rehearsal for her concert tour, she talked with freedom and vivacity on various phases of her art from the standpoint of those who wish to make a success of singing in opera or concert. Probably the most famous among all the famous Carmens, her supremacy in this role has a tendency to cast in the shade her accomplishment in others. Her superb voice and dramatic interpretation have lent distinction to the parts of the three Marguerites (Berlioz’, Boitos’ and Gounod’s), of Ophelia, Messaline, Hérodiade, Sappho, Lakmé, Pamina and numerous other operatic réles of the dramatic soprano, and her successful concert tours have established her fame in this newer field. One of the very greatest singers of the age, she has drawn upon both her study and her teaching experience for the benefit of the reader.

PLAIN CHANT FOR VOICE PLACING

“When I was a young girl,” said Madame Calvé, “we had an old music master in the convent in which I was brought up, who taught me piano and solfége. There I sang the old religious music of the Church, the canticles, the plain chant, and I do not think there is any better music to make the voice develop in a natural manner than this — old religious music. It seems to place the voice naturally. I-know I never had any difficulties of voice placing; I never had to work for it, and I believe it was because I sang so much of this music when a child. In the Midi, the south of France and Italy, we do not have so much trouble . with voice placing as they do in other countries. —

SINGING TOO MUCH FROM THE THROAT

“The mistake that many—not all—American and English students make, is that of singing too much from the throat. For this the English language with its naturally throaty sounds is partly responsible, I think. The vocal student should remember that the voice must be placed with the lips, and not too much from the throat. And my own experience after I left the convent and studied with the talented tenor, Puget, has firmly convinced me that the foundation of all good singing lies in the study of the bel canto— it is indispensable. Let students sing the music of the old Italian masters of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, Porpora, Palestrina and others, if they wish to gain voice control. The young girl who attempts to sing modern music, for instance, without ever having studied the Italian music of the bel canto will find that her voice is not well poised. I have always insisted that the pupils who study with me sing Mozart, since he is unexcelled for melody singing and the proper placing of the tone. If the young girl who sings modern music knows her song classics, if she have this bel canto foundation, she is far better prepared to overcome the greater difficulties of intonation offered by modern composers.

SELECT A TEACHER WHO ILLUSTRATES HER MEANING WITH HER OWN VOICE

“Select a teacher who illustrates her meaning, when she is teaching you, with her own voice. After the death of my old teacher, Puget, I went to Madame Marchesi. But I remained with her only six months. Why? She had long since lost her voice, and could not give a practical viva voce example of what she wanted me to do. Madame Laborde, on the other hand, with whom I then took up my studies was my teacher for three years. She was a wonderful coloratura singer— her Rosina was famous—and she was not only able to tell me how difficult passages were to be sung and interpreted, but she could show me what she meant as well. To Madame Laborde I owe all my success, and, to a large extent, because she could illustrate her meaning with her own voice. To me there is always something illogical in selecting some one who is vocally mute to teach the beauties of tone production. If I could not show my pupils what I mean with my own voice, I do not think I should feel justified in teaching them.

SYSTEM AND METHOD

“I do not believe in any one ‘system’ for teaching singing. Each student is different, and so each ‘system’ must be different also. But I have a well-defined méthode, in the French sense of the word, of instruction, which I vary and adapt to the individual needs of individual pupils. That I use my own special exercises, scales and vocalises goes without saying, and I insist on my pupils working hard while they work. I try to give them style—that quality of singing which is so hard to acquire—and the perfect legato; and above all you will find no pupil of mine singing in a chevrotante voice, a ‘goaty’ voice, for that is something I will not permit. I insist that the pupil’s voice be well placed, in the masque.

“And I lay the greatest stress on the slow practice of simple exercises. Too many teachers are not exact enough in this respect, in order to please the pupil who lacks patience. I make the girls who study with me in the summer in my home at Cabriéres sing scales very slowly, in long, long time intervals, in all the keys; and never allow them to sing them fast. No, I do not confine my teaching solely to advanced pupils. There are two kinds of pupils whom I enjoy teaching in particular: the talented advanced pupil, with whom I can at once take up the interpretation of the great réles, and the beginner. For in her case I have a chance to develop the voice exactly as it should be developed, before the student picks up bad habits and defects.

PSEUDO PUPILS OF FAMOUS TEACHERS

“One thing has always seemed very unjust to me. A pupil will study from one to three months with some famous teacher, and then leave proudly claiming that she is his pupil. How often Jean de Reske has mentioned the fact to me! You cannot perfect a pianist or a violinist in three months, and certainly not a voice. Aside from the harm they do themselves these pseudo pupils wrong the great artists who may be teaching them. People who hear one of these éléves and are told they are pupils of Mr. X, or Madame Z, hold their teachers responsible for their singing, while the student may have taken only a few lessons from the master in question.

THE “FOURTH VOICE”

“One thing I try to teach them—it cannot be learned by all—is a vocal possession of which I am very proud and jealous, the ‘fourth voice.’ In My Life I have told about the eunuch of the Sistine Chapel in Rome, Mustapha, a Turk, from whom I acquired this strange and lovely register, which he called his ‘fourth voice.’ It is a gamut of tones which are neither masculine nor feminine in character, but have a certain celestial quality of their own, of the greatest softness and charm. I studied with Mustapha—so much was I impressed by the beauty of these tones which I had heard him sing in the solemn services at St. Peter’s—and it cost me three years of unremitting work to perfect my control of this special register. These ‘fourth voice’ tones are located in the frontal sinus, in the bridge of the nose, and might be compared to the harmonics of the violin. But wait a moment,” continued Madame, “why do I tell you about them, when it is much simpler to sing them for you!” She threw back her head and produced ‘an ascending flight of clear, full, beautiful tones and then, in the “fourth voice,” she repeated the notes she had sung. The tones were like and yet unlike an echo, fainter, yet at the same time more colorful, more crystalline. They were very sweet, with a noticeable difference in timbre from the usual tones of the singing voice, and with a distinct bell-like quality—a reflection, delicate and evanescent, rather than an echo of the other voice. “No,” said Madame Calvé, “I have never regretted the time and effort — I gave to learning these tones, and I teach the secret of their production (a secret in which patience is the principal ingredient) to those among my pupils who seem qualified to learn it.

GESTURE IN CONCERT SINGING

“It is one of the means of effect, one of the ways of making the voice rouse emotion in the listener. Each and every effect, whether it be one purely vocal, or purely dramatic, whether it lie in the singer’s tone or in her technic of de

livery, is right and legitimate if it is artistic. I have been criticized for using gestures in my concert singing. Such criticism seems pedantic to me. Every song, especially every dramatic song, presents a story or a mood. Merely because the singer is singing the ‘Bell Song’ from ‘Lakmé’ on the concert, and not on the operatic stage, should she stand there like a wooden image and not lend the charm of movement and impersonation to her singing?

“If the words of a song suggest or describe action, they call for gesture, in most cases. And no singer with a proper sense for dramatic truth will refrain from gesture if it help to give her listeners a clearer, more vivid idea of what she is singing. I must express myself fully and completely. My gestures on the concert stage are a part of my interpretation of the song I am singing. They are spontaneous, they are part of my natural means of self-expression and—incidentally—though they have been criticized, my audiences seem to like them. So I shall continue to use the expressive gesture on the concert stage, and I would advise every young artist to remem

ber that gesture and movement, rightly used, give fire and dramatic vitality to a song-recital program just as they do to an operatic rdle. No student who intends to specialize as a concert singer loses by watching the great singing actresses of the operatic stage, and observing their use of the dramatic gesture to drive home the meaning of the words and music they sing. Of course, the words, as they have inspired the composer to write the song, should also inspire the singer’s interpretation of it; and her presentation must be developed out of the ambience of the song itself.

“Finally, there is one thing every student should remember, whether her objective be the opera or the concert stage—she must remember to be herself. I will say nothing about concentration and hard work. I never learned a réle by sleeping on the score, nor did any one else, and the fact is pretty well established. But to be yourself in your art is sometimes very difficult. It is hard to know where to draw the line between tradition and precept and your own artistic instinct. In such a case, when you are driven to choose, rely upon yourself. For only the artist who radiates a personality of her own, who expresses her own self, her own mind, her own soul, instead of the traditions of others, wins to greater achievement and success.”

#classical music#opera#music history#bel canto#composer#classical composer#aria#classical studies#maestro#chest voice#Emma Calvé#Soprano sfogato#dramatic soprano#soprano#Metropolitan Opera#Met#Royal Opera House#Covent Garden#Belle Époque#La Scala#Teatro alla Scala#Conservatoire de Paris#cigarette girl#classical musician#classical musicians#classical history#historian of music#history of music#musician#musicians

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Here we see very old ScrapBook. Take a look of this very nice Collage with so many great names and the big photo from Feodor Chaliapin.

#classical music#music history#opera#bel canto#composer#classical composer#aria#classical studies#maestro#chest voice#classical musician#classical musicians#classical history#history of music#historian of music#musician#musicians#diva#prima donna#Golden Age of Opera#Golden Days of Opera

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Denis O’Sullivan (1868 – 1908) sings "The Curate's song" from "The Sorcerer" by Gilbert & Sullivan”. Recorded in 1901.

From Pilot, Volume 71, Number 6, 8 February 1908:

DENIS O'SULLIVAN DEAD.

America’s Greatest Irish Actor and Vocalist.:

Columbus, 0., Feb. 1. Denis O’Sullivan, the American-Irish actor and singer, died today in the Grant Hospital after an operation for appendicitis. . Denis O’'Sullivan, though England and Ireland had claimed the greater part of the professional career upon which he entered in 1895, was widely known in New York's musical and dramatic circles. In the American eye his ability as an actor and as a vocalist had been further enhanced by the recitals which he gave in Carnegie Hall, New York, a little more than two months ago. These had prompted predictions that success would attend his American tour. This visit was a return for Mr. O’Sullivan to his native land, for he was born in San Francisco in 1868. His father, Cornelius O’Sullivan, had when a boy been caught in the tide of immigration, and leaving the ancient town of Skibbereen, Ire., came to the United States and settled in the Pacific coast city. The newcomer prospered and his charities in the native town of Ireland, ‘to which he returned after his son had ‘been born, still are related with pride by the residents. The son studied as an amateur under Carl Formes and Ugo Talbe. Then came a course of study under Vannucecini in Florence, followed later by instruction under Shakespeare and Santley in London. His musical education was concluded as a pupil of Sbriglia in Paris. Misfortune was encountered by the family, and it was this cause in great part that led to Denis O'Sullivan’s entry upon a professional career in 1895. His debut in Dublin in that year with the Royal Carl Rosa Opera Company met with an instant individual success, and good fortune attended afterward. He created the title role in the opera of “Shamus O’'Brien.” The part of the Duke in the “Duchess of Dantzig” also was created by him, following shortly after his production of “The Post Bag.” He created also the role of Barry Trevor in “Peggy Machree.” He had been honored eight times by appointment to the post of adjucator and vocalist of the Feis Coil, or Irish Musical Festival. Always interested in Ireland’'s affairs, he sat as a delegate in the Irish national convention held in Dublin in May, 1907. He had appeared in concert throughout Ireland and England. Before his departure for the United States he was ‘the guest at a notable dinner given in ‘the Hotel Cecil, London, at which T. P. O'Connor, M. P., acted as toast‘master. ! Mr, O'Sullivan’s death is a distinct loss to the stage. Personally few men had more friends. He had a magnetism, a quiet, dignified manner and a keen appreciation of the humorous that was refreshing. His father was a banker in San Francisco and his mother a gifted woman, who was an artist and a writer of plays under the nom de plume of Patrick Bidwell. The actor was fairly wealthy, having property interests in San Francisco. At the time of the fire, like others, he suffered financially, but itis understood he died possessed of a comfortable fortune. He studied in St. Ignatius’s College, San Francisco. His wife, who was with him when he died, was a daughter of Oscar Sutro, one of the leading lawyers of San Francisco.

#classical music#opera#music history#bel canto#composer#classical composer#aria#classical studies#maestro#chest voice#Singing Sullivan#intensely Irish#baritone#tenor#The Curate's song#actor#Gilbert & Sullivan#The Sorcerer#classical musician#classical musicians#classical history#history of music#historian of music#musician#musicians#diva#prima donna#Golden Age of Opera#Golden Days of Opera

0 notes

Text

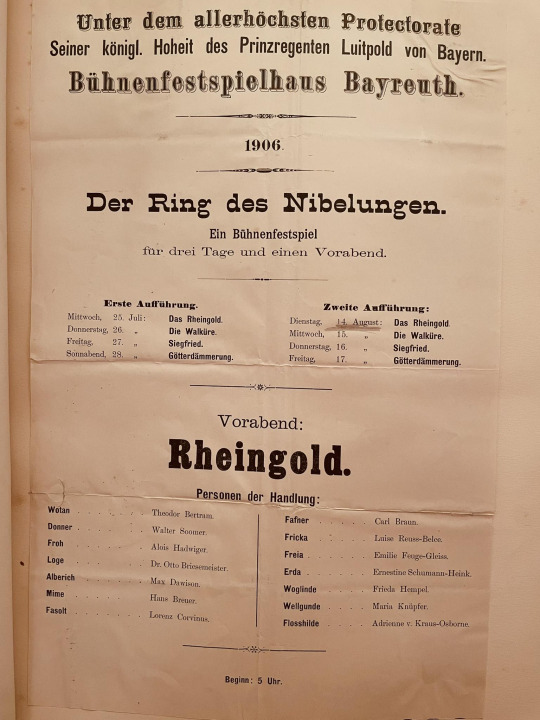

Here we see this original Poster from the Bayreuther Festspiele 1906 this was the last year Cosima Wagner managed the Festival. With a great cast under the Conductor Michael Balling staged by Cosima Wagner.

#classical music#opera#music history#bel canto#composer#classical composer#aria#classical studies#maestro#chest voice#Poster#Bayreuther Festspiele#Bayreuth Festival#Der Ring des Nibelungen#Richard Wagner#Cosima Wagner#cast#classical musician#classical musicians#classical history#history of music#historian of music#musician#musicians#diva#prima donna#Golden Age of Opera#Golden Days of Opera

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Here we see this 100 years old Program from The Metropolitan Opera 1925. Verdi „Requiem“ with a great cast under Tullio Serafin.

#classical music#opera#music history#bel canto#composer#classical composer#aria#classical studies#maestro#chest voice#Metropolitan Opera#Met#Requiem#Messa da Requiem#Giuseppe Verdi#The Metropolitan Opera#The Met#cast#program#poster#classical musician#classical musicians#classical history#history of music#historian of music#musician#musicians#diva#prima donna#Golden Age of Opera

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

From From The art of the prima donna and concert singer (1923) by Frederick H. Martens (1874-1932):

Sophie Braslau is one of the few dramatic contraltos who have proven conclusively that art rather than register is the first factor in achieving wide and justified success on the concert stage and in opera. She is a shining example of the fact that the personality of the singer and the quality of her work establish her fame; that the soprano voice is not necessarily a more “popular” one than the alto; that it is the range of a singer’s art rather than the range of her notes which commands appreciation. Not that this means that Miss Braslau’s range is limited, either, for it covers three octaves and more. In the music room of her New York home Sophie Braslau expressed constructive ideas regarding her art which bear the indorsement of her own great success for students desirous of emulating her example.

POINTS THE AMBITIOUS STUDENT SHOULD CONSIDER

“Success in opera or concert?” said Miss Braslau. “The girl who wants to make a name for herself in opera or recital should bear in mind the fact that, in the long run, her voice, her natural vocal equipment, represents only about fifty per cent of the sum total of essentials needed. An individuality which compels, a mentality capable of absorbing the inwardness of the thought she has to project, plus great musical intelligence are as important as the voice itself. It is true that some who have reached the heights in opera or concert are more proficient vocally than mentally; yet analysis would show that in such cases some outstanding individual characteristic was the corner stone of their success. And this, after all, proves that individuality and not voice alone must be taken into account.

“Every young singer should know herself. But she should not look into the mirror of introspection from the angle which will reflect her as she wishes to be, but face to face, to realize what

she really is. And if honest self-examination shows her that she is unjustified in cherishing operatic or recital ambitions, then she had better give them up before she enters on a long road of disappointment and disillusionment. Quite aside from her voice, the young girl who wants to become a prima donna must have an inborn sense of the dramatic, a feeling for theatrical values. Besides what may be taught by way of acting, she must have a natural feeling for appropriate gesture, how to walk and move about the stage, how to project her personality instinctively.

“And a sense for the dramatic is just as necessary on the concert platform; more so, perhaps. There the sense of dramatic values must be keyed up to a higher pitch; it demands finer quality, because the gesture and movement which is natural in opera would seem exaggerated in concert. The singer stands alone, on the bare stage, and she must create her dramatic effects through sheer power of mind in presenting her music, through absolute artistic concentration. Too many singers on the concert stage merely sing.

Fate in casting the die has given them a voice lovely enough to hide otherwise obvious defects, and accidental circumstances may have helped to establish their fame. But such singers might be called freaks of chance. The really great singer must have the finer and more distinctive personality which dominates the concert stage, and whose vivid and compelling art makes the lack of action, costume and theatrical decoration seem negligible.

HINTS DRAWN FROM A DUAL CAREER

“I grew up vocally, so to speak, in opera. I began with parts no more than two or three measures long and, like most young opera aspirants, was very impatient to sing the big roles at once. Yet, as I grew gradually into star roles, I saw that Mr. Gatti-Casazza, who had held me back in what I sometimes used to think a very overcautious way, had been entirely right. He had my very best interests at heart, and did not want me ‘to start something I could not finish,’ to use a slang expression. I am glad now that at a time when I was very eager to be tried out in the role of Amneris, Gatti-Casazza would not allow it—I was not ready.

“And I am glad I turned my attention largely to my concert work when I did, because I have grown to love it, and at the same time know that I shall return to opera—yes, I may do so next year—all the better equipped when I do.

“The dramatic soprano and coloratura? Well, the contralto’s position as regards coloratura is much the same as that of the dramatic soprano. I can see no reason why the dramatic contralto, if her voice be properly trained, should not sing coloratura passages with flexibility. Brilliancy is another matter, of course. But even the lyric soprano, as a rule, sings soprano coloratura passages—if called upon to do so—with flexibility rather than brilliancy, for brilliant coloratura is distinctly a soprano possession.

THE CONTRALTO ROLES IN OPERA

“Tt cannot be denied that some of the contralto characters in opera are unpleasant types. But I do not think that they are unsympathetic to an opera audience. I believe that what an opera audience wants is not sympathetic characters so much as real vocal and dramatic art, powerfully projected. If a contralto has a glorious voice, and her tones ring out through a crowded house; if the emotions of hatred, revenge or despair which she expresses thrill, the audience will respond and she will make a lasting impression. I remember when I was a little girl I heard Schumann Heink as Ortrud. She was dressed in black, her acting was superb, and the hatred in her voice so true, she so completely dominated | the scene that she held me spellbound. I was actually so frightened that I hid my face in my mother’s skirt. But her glorious tones, her vivid art, are something I have never forgotten. To me she has always been an ideal singer. Recently when a critic called me the Schumann Heink of my generation I felt I had been paid the greatest possible compliment. Her voice has the dramatic quality comparatively rare in the contralto, and to think I shared such a possession with her was pleasant to learn.

“A good range, of course, is quite as necessary for concert singing as for opera; more, in fact, for in opera the orchestra often helps out the voice. I have three octaves, from A below the F of the bass clef to the high C.. In “Trovatore’ I can sing Azucena’s cadenza in Act Two with ease. The development of my register is really entirely due to Sibella, whom I consider a wonderful singing teacher. He has coached and taught me on the theory that my voice was one of a peculiar, older type—the Alboni type of voice, with its equalized register—now practically extinct, Schumann Heink being, perhaps, the only one of the school remaining.

THE DRAMATICS OF THE CONCERT STAGE

“On the concert stage each song may be said to have its own dramatic scheme, musically and in projection. Unwavering sincerity and a knowledge of what you are doing every minute you sing are essential to project your song properly. At the same time you must be able to convey and establish an impression of absolute abandon, if necessary. For the moment you must become wholly and entirely that which you sing —the mood, the emotion, the character.

“In a strict sense I do not consider gesture legitimate on the concert stage, save, perhaps, in the case of the diseuse, like Yvette Guilbert, where gesture forms an integral part of a definite art type, and has to be used. Chaliapin, to my mind, is the outstanding example of correct gesture on the concert platform. He can run the gamut of expression with a minimum of bodily movement, and display the greatest art in facial inflection. The real Lieder singer should give her audience drama, not in movements of the body and arms, but in the inflections of her voice and changes of facial expression. ‘The entire body may express feeling and mood with but slight movement. A relaxed pose, codrdinated with voice and features, may convey a strong impression of languor or resignation. Passion and ardor speak in a tensing of the body muscles. A proud and confident raising and throwing back of the head makes a mood of triumph and ecstasy unmistakable. By the slightest expenditure of natural movement many moods may be established, and this simplicity of motion is the keynote of them all. In opera even, excess of movement often tends to weaken the impression the singer wishes to make. I think John Barrymore is one of the best models for the opera singer, whether professional or student, as regards the dramatic factor. To see him in Hamlet, for instance, is an object lesson in the art of listening without movement, yet always making you feel that his whole attention is concentrated, that he is drinking in every word he hears, that his attitude is not a quiescent but a dynamic one.

TRADITION AND TEMPO

“I am no great believer in tradition. Every true artist, I think, establishes her own tradition; she does things in the manner best suited to her own artistic character and personality. In music the absolute values of time and tempo, expressed as the composer wished them to be expressed, are my bases of interpretation. Why imitate a conception, even if artistic, because it is ‘traditional,’ because some other artist may have expressed it in that way? ‘The poem originally inspired the song; the composer has set down the exact time values of his notes which interpret it. I use the metronome when I am studying a song, and it might be well if it were more largely used by the student. It enables you to establish what should be the first interpretative consideration, the tempo, the time of the musical mood. After that, the melodic line or design may be given the individual color you wish to give it, without doing violence to the composer’s thought.

“T never realized the importance of the absolute time value of notes until I sang with Toscanini at the Metropolitan. He was very meticulous, and with him a dotted quarter was a dotted quarter, neither more nor less. He might, if music and situation justified it, allow a singer to rest on a high note; but he never broke the rhythm, never did violence to the rhythmic values of a vocal phrase. I learned to sing in time from him.

“No artist should have to shift and change her tempos to carry out her interpretation. And the singer should be able to play the piano. I began to study it at six and continued for years. Ability to play the piano is far more than an accomplishment for the singer.

“As for tradition, take the ‘Erlking,’ for instance! How can there be such a thing as a ‘traditional’ interpretation? The singer either has her own individual conception of the poem and projects its music accordingly, or she has not. Clinging to tradition often means an artistic tragedy for the artist. The artist should be allowed to follow her own instinct in interpreting. She should never pause here or there, ritard or accelerate, sing forte or piano at certain measures, because some one else in the past has done so. If she is an artist, she will have her own individual way of expressing the music she sings. In opera, also, I think too much stress is often laid on tradition; Aida must cross the stage at a certain given moment, presumably because all the Aidas since the Suez Canal was opened have done so. Carmen must go through certain conventional movements at certain times, because other Carmens have done so, and so on.

VOCAL STUDY

“These things cannot be taught. They must come from out yourself. I should say, speaking from eight years of hard work, that you learn all the details of the stage (opera or concert) only through your own experience. There is no other way. For the professional artist the hardest study years begin when she first faces the public. And she must honestly love that public, love to sing for it, if she wants to be loved in return. Only a few artists on the concert stage have conquered this entire, loyal affection, and among them I think Alma Gluck is one of the foremost.

“I always do a certain amount of technical work while on tour, about half an hour a day, to keep ‘tuned up’ so to say. I usually begin with exercises combining two notes, then three, four, five and six, going on to scales in sustained tones. Each day I use exercises of a different type and kind, and work them out. It is to Sibella that I am indebted for the realization of what positive vocal technic and true vocal flexibility really

mean. Before I went to him I used to read about old Italian bel canto singing; he showed me what it actually should be.

“In general, I believe the vocal student spends too little time in preparation. The desire to ‘rush into’ things, to sing before one can sing is too prevalent. It prevents concentration. So much may be done with the mind. I concentrate on my songs and study them mentally to a great extent, thus saving my voice for actual concert work. I do not indulge largely in vacations. This summer past I took two lessons a day, week in, week out, because I am interested in my work. When I am not on tour I practice from one to two hours a day, with pauses for rest between times.

THE CONCERT PROGRAM

“As a result of feeling the pulse of my audiences, I have adopted an elastic program framework of four groups. And I sing whatever pleases me—if I like a song I sing it. As regards music I am an absolute eclectic, and program whatever seems to me worth while. But I never classify audiences and try to make up programs for people of certain sections or parts of the country. I regard this as a great mistake. The people who form my audience in Coffeeville, Kansas, do not want to feel that the artist who sings Moussorgsky in New York will pick out something gentler, sweeter or more obvious, thinking ‘they would understand it better.” Audiences do not want to be sung down to. They are entitled to the best I have to give.

“My first group includes old classic arias, such as the Bassani ‘Cantata,’ but never an opera aria. I do not think the opera aria belongs on the concert program. As an encore? Yes: I always sing something from ‘Carmen,’ my “Eli, Elil,’_ and Stultz’ old ballad, “The Sweetest Story | Ever — Told.’ But I never program the opera air or the ballad.

“Though my second group usually consists of Russian songs, I have a wide choice and can vary it considerably. I sing Moussorgsky, Rachmaninoff—he accompanied me at a concert in New York once, the only singer he has aceompanied in the United States, an honor of which I am proud, for he is a great artist—Arensky, Gretchaninoff and others. Then I sing the old Hebrew temple melodies. I sometimes drop this group and substitute German Lieder: Schubert, Schumann or Wolf.

“My third group contains modern French or Italian songs, together with English songs. There is such a thing as giving an audience too many songs in foreign languages, and I like to sing as many songs as possible in English. Two foreign groups and two almost English groups offer a fair balance. Some of the Wolf and Mahler songs I always do in English; people prefer them in that language. Yet I would not dream of doing the ‘Erlking’ in any language save German.

THE ACCOMPANIMENT IN THE SONG RECITAL

“I think critics are all too apt to dismiss the work of the accompanist at the song recital with a stereotyped line at the end of their review; something to the effect that the accompanist was ‘competent.’ Of course, the accompanist is not supposed to project personality. The accompanist is a background. A musical background, however, is very important in making a song stand out. It is like the scenery in a dramatic production. The accompanist’s technic and touch supply color, and no fine accompanist should be summarily dismissed with a brief mention. This is another tradition which should be broken. I need sing a song only once for Mrs. Ethel Cave Cole, who is my accompanist, for her to grasp my interpretation. She is, in my opinion, one of the best accompanists to be found, and her musical | intelligence and grasp of ensemble is quite beyond praise.

EXTERNAL AIDS TO THE VOICE

“No, I never use anything for my voice. In fact, I never give it a thought except when I am singing. As for catching cold, I never worry about it. I never eat lozenges, never use the atomizer, never gargle. I try not to overtire myself, and believe that a care-free mind is one of the best practical means of voice preservation.

“I do devote considerable attention to my face and to bodily exercise—daily dozens, massage, etc. But this is merely part of a balanced physical routine. I never let little things worry me. ‘Though an only child I was brought up with a rod of iron, with the result that I have a hardy constitution and am not as spoiled as only children often are. I am a ‘fresh air fiend,’ and like to walk miles at a time. And I must have my hot bath, followed by an ice-cold shower; every morning. Cleanliness and fresh air, keeping in good physical condition, I find, does away with all need of using palliatives and tonics.”

WHAT UNDERLIES ART IN SONG

At this juncture, to console the writer for the fact that she was not going to say much more, Miss Braslau offered him a cigarette and then, with an air of finality, brought a very interesting interview to an end. Said she: “I think that perhaps the most important thing for every ambitious vocal student to remember is that underlying all great art in song is the widest possible knowledge of other things besides music. The broader her cultural outlook, the greater her mental development, the wider her circle of human and intellectual interests, the better she will sing, for she will not sing as a specialist.���

It might be added that Miss Braslau herself is one of the most striking instances now before the public of the exemplification of this theory.

#classical music#opera#music history#bel canto#composer#classical composer#aria#classical studies#maestro#chest voice#Sophie Braslau#dramatic contralto#contralto#Metropolitan Opera#Met#classical musician#classical musicians#classical history#history of music#historian of music#musician#musicians#diva#prima donna#Golden Age of Opera#Golden Days of Opera

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

William Paull (baritone, 1872 – 1901) sings "The Mikado's song" from “The Mikado” by Gilbert & Sullivan. Recorded in 1901.

From nla.gov.au:

MR. WILLIAM. PAULL.

LONDON, Feb. 9

Mr. William Paull, the baritone, was killed at St. Louis, United States, through falling from a window on the sixth floor of an Hotel.

[It is not often that os fire a voice us that of the late William Paull is heard in musical comedy although he was chiefly identified with it in Australia. This favourite singer, who was probably not more than 13 years of age at the time of his death, sang many important parts in England with the Royal Carl Rosa Company at the London herrick Theatre and elsewhere during an engagement which terminated at the end of 1897. He made his Australian debut under engagement to Messrs Williamsonand Musgrove at the Sydney Town Hall on February 23, 1898, when he supported Madame Albani. In the same was as three months later he sang the baritone and bass parts in the "Elijah. and " Messiah " under Signor Hazon's direction during the festival of Philharmonic Society. The quartet consisted of Madame Albani, Miss Sarah Burg, Mr Orlando Harley, and Mr Paull At the close of the Album tour Mr Paull joined the Royal Comic Opera Company, with which be played clearly the part of Reggio i Fairfax, making an especial hit by the ten domes and charm with which he rendered " star of My Soul ". In November, 1899, Mr Paul appeared as King Henry V in " Ma Mie Rosette," and again held his owner by the soft beauty of his voice, though he followed Mr Wallace Bray allow, deservedly famous in the role Mr Paull, Hill also appeared as Strephon in " Iolanthe," and as Maximilian in "La. Pouple," bade farewell to Australia at the Adelaide Town Hall on May 15, 1900, when he was supported chiefly by the Misses Jessie King and Nora Kyffin Thomas In November of the same year the erstwhile musical comedy baritone was in grand opera under Maurice armies management of the Metropolitan Opera House, New York. He sang in " I Pagliacci " with Zélie de Lussan as Neda and Philip Brozel as Carrie, and he was also in the cast of "Cavalleria rusticana", with Febea Strakosch as Santuzza. In 1901 Mr Paull joined the Castles Square Opera Company, and at the Planter's Hotel, St Louis, the city where he met his death, he married Miss Ethel Vonciu Gordon (February 19), who had travelled from Sydney for the purpose Miss Gordon, who studied under Signor Riccardi, belongs to this city, and was much a Joined for her good looks during the time she sung with the chorus of Mr J C Willi union's company. As regards the voice of the singer whose death in hot regretted, it was of the purest and most charming quality throughout, and faultlessly produced As rub a little more power it would have, been a " star voice " for grand opera, but lacking the larger volume it still moved drape)sufficient for all the demands of the lighter works for the theatre].

#classical music#opera#music history#bel canto#composer#classical composer#aria#classical studies#maestro#chest voice#William Paull#baritone#Carl Rosa Opera Company#Royal Comic Opera Company#Metropolitan English Opera Company#The Mikado's Song#The Mikado#comic opera#Arthur Sullivan#W. S. Gilbert#Gilbert & Sullivan#classical musician#classical musicians#classical history#history of music#historian of music#musician#musicians#diva#prima donna

1 note

·

View note

Text

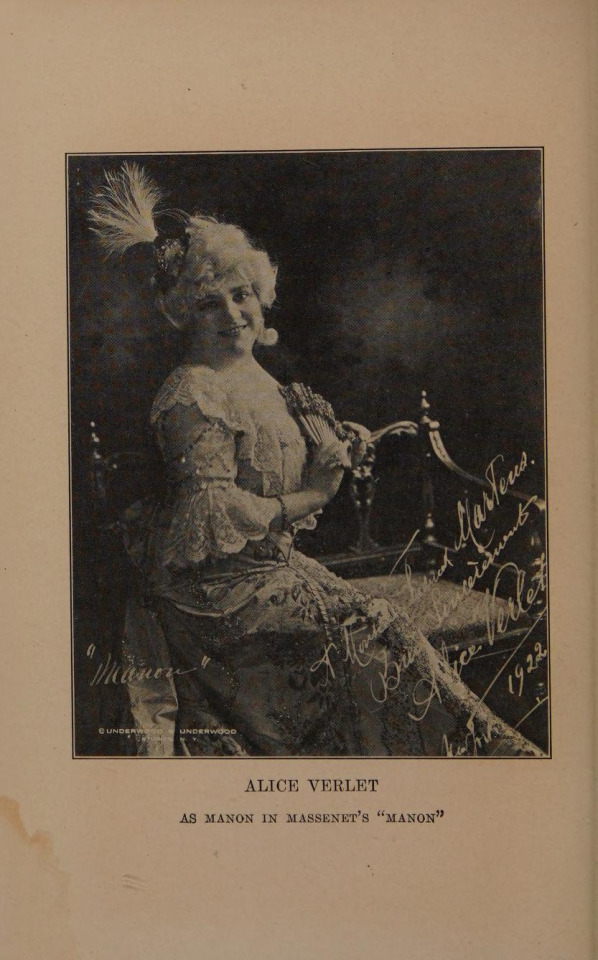

From The art of the prima donna and concert singer (1923) by Frederick H. Martens:

Mille. Alice VERLET, the distinguished lyric coloratura soprano of the Paris Grand Opéra, whom Massenet mentions among the interpreters of his roles in his Souvenirs, talked to the writer in - her comfortable New York studio of how to sing and what to sing, in opera and recital. She spoke from the standpoint of the French prima donna and concert singer, whose art has been developed along classic French and Italian traditions and in the course of her conversation stressed many points of practical value to the American student of song.

“Perhaps my experience has been different from that of many other singers in that I had but one teacher,” said Mlle. Verlet. “I began to study seriously when I was no more than fourteen, in Brussels, and my teacher was Mme. Moriani, who combined in her teaching methods _ the traditions of the French school and the older Italian one of Garcia, which produced Grisi and Malibran; and I made my operatic début four years later, at the Paris Opéra-Comique, in ‘Les Noces de Jeanette.’ Mme. Moriani had one great virtue as a teacher—she developed the voice naturally and without forcing. She was opposed to all driving, said that every vocal student must use nine tenths brain power and only one tenth voice power in her work, and laid stress on letting the voice grow and develop without straining.

A NATURAL VOCAL DEVELOPMENT

“There is, as a rule, far too much crowding and ‘driving in vocal teaching to-day. I am speaking out of my own experience, as a vocal student, and as a teacher and as an artist, when I say that practicing too long at a time is a most dangerous error. One should begin by singing five minutes at a time and making a pause; then, always ten minutes, pausing, then twenty, and, finally half an hour. At the most the student should not sing, all told, more than an hour or an hour and a half a day with three or four pauses. And the operatic student in particular, must not be ambitious at the expense of her voice. And, aside from strain there is the matter of vocal endurance. At eighteen I could have sung one or two of the big arias in Massenet’s ‘Manon,’ with orchestra, but not the entire opera score, the same evening. The standard Italian vocalises, especially those of Garcia—Mme. Moriani was accustomed to make changes in them to suit the individual qualities of voice of her pupils—if properly used, probably answer every purpose of natural voice placing and development. Initiative in the vocal student is all very well, later on, but in the formative period of voice training the teacher is allimportant. And a good teacher should have no hard and fixed rules of procedure. Every student has a different larynx, a different diaphragm, different vocal cords. Every individual voice has a different quality and different possibilities, and the only good vocal teacher is the one who tries to bring out the individuality of the individual voice.

SINGING AND STUDYING HEAVY ROLES TOO SOON

“One common fault of the operatic student is that she sings and studies réles which are too heavy for her voice too soon, thus injuring her vocal cords by putting an unwarranted strain on them. When I first made my début I sang the’ lighter coloratura réles; I knew the more difficult ones would come in time. But putting ~ a girl of eighteen or twenty through the heavy Wagnerian roles, for instance, as is often done, sometimes” paralyzes the vocal cords and ruins her voice. The gradual development of vocal strength is the only safe and sure way to. attain it. And ‘gradual’ does not mean two hours’ work , a day without stopping—that is, unless the student is as strong as an ox, and even then there is the danger of her voice becoming hard and losing charm, and charm is, perhaps, the greatest of all vocal qualities, both in opera and in recital.

DAILY EXERCISES

“And whether the advanced student is singing in opera or in recital, or preparing to sing in — either, daily exercises in mechanism should never be neglected. Every morning I have kept up the habit of going over my exercises. Even on days when I was singing in opera I always ran over a few before the performance. The voice must be kept flexible, especially if one has to sing big roles. I have inherited some simple mechanical exercises from Mme. Moriani which, in my opinion, cannot be improved upon—scales, three, four, and six-note passages, gruppetos, trills, staccati and arpeggios, and so on—which are purely technical, and which I always use. If daily exercise is consistently followed out, flexibility becomes a vocal habit.

NOISE VERSUS TONE

“One curious present-day feature of singing in public is the confusing of noise and tone. The use of a full, rounded, yet soft and charming piano or mezza voce tone, so necessary for shadaing and contrast, is discouraged in favor of a big, noisy one, even though it be harsh, metallic or wooden.

I tried to explain to one student who came to me, a girl with a wooden voice, how essentially the development of a beautiful piano tone really was. And what do you suppose she said? ‘Why, no manager would think of engaging me if I sang so softly!’ I think one reason this mistaken idea is propagated in owing to the various small Italian opera companies who tour the country and who, rightly or wrongly, and probably the latter, imagine that out-of-town audiences insist, as your American slang says, on ‘an earful’ of music for their money.

SOME GRAND OPERA ROLES

“Like Lilli Lehmann (and all the great singers of the past), I first sang opéra comique roles, light coloratura roles, with plenty of high notes in the upper register, but in no wise as difficult as the heavier coloratura roles of grand opera. Such roles as Marguerite in ‘Faust,’ Juliet in ‘Romeo and Juliet,’ and Lakmé in Delibes’ opera, came later. And there was the greatest of the Mozart roles—the Queen of the Night! At the Paris Grand Opéra the Italian tradition of presenting the Mozart coloratura parts is observed, and I do not think it can be improved upon. ‘They should be sung with the purest legato, and studied slowly without any forcing of the voice. And no student should imagine that she can study them without a teacher, if she wishes to sing them with all their beauty. Singing a Rossini role is quite a different matter from singing Mozart. Rossini’s Italian buffo style, as in his ‘Barbiere,’ is never quite so pure, so honest, so noble as Mozart’s. In singing Rossini one may be able to slur over this or that vocal difficulty and yet produce an effect; but in Mozart, whose music is as clear as crystal, every single tone must be perfect, and must be sung in perfect style.

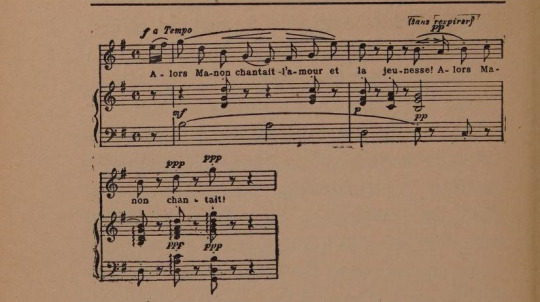

STUDYING MASSENET ROLES WITH THE COMPOSER

“I have often studied operatic roles with their composers, but I do not know of any who was more truly inspiring as a coach in his own works than Massenet. He was alive to every shade of meaning in a role, and sitting at the piano would make it clear to the singer with a patience, a kindness and a forgetfulness of self in the music which is hard to describe. I studied the réles of Manon, Grisélidis—which I created in Bordeaux —and Thais with him. For Manon I remember I went to his studio, Menestrel, where his grand piano was heaped with printed music and manuscripts—I recall that some of the latter were written with violet ink—and as for Thais, originally created by Sybil Sanderson, and in which I sang the title réle at the revival, I studied with him in his Paris apartments, where he had a wonderful music room. Wherever possible, the singer who is going to present a role by some living composer should try to make an opportunity of rehearsing it with him. There are delicacies of nuance and expression which he alone can give her; there are vocal effects which— though he may not be able to sing them for her—he can make so clear that they cannot fail to be grasped. Massenet, for instance, when he illustrated the part of the tenor, Des Grieux, in the Church Scene in ‘Manon’ at the piano, made the instrument sing his part with such dramatism, such conviction, that when, as Manon, I recalled our departed days of happiness, asked his forgiveness, and insisted that I loved him, in my singing, I was lifted to the highest pitch of musical and emotional expression in order to do justice to the situation and Massenet’s conception of it.

“He laid the greatest stress on ae of detail. In the scene of the Promenade de la Cours de la Reine, where Manon, as Bretigny’s mistress, is promenading under the trees, she sings the ‘Fabliau’—a beautiful and difficult coloratura aria which is sung at the Paris Opéra Comique, but not at the Metropolitan. In this air Massenet, who paid the keenest attention to characterization, was especially anxious to show how Manon, with all her charm and all her appeal, was, after all, tainted with the vulgarity of the courtesan, that she could not altogether get away from her basic lack of conscience and morals. He wanted this to be brought out in a natural, fleeting way and not emphasized too strongly. So he said: ‘Here, in these two measures—they are enough—where the music lends itself to the characterization, you must sing with a touch of the music hall, a suggestion of the coarse and common!

After that, you must revert again to the better style.’ And it was by such details that he revealed all sorts of delicacies of expression to the singer who coached with him. Thais is a delightful réle, it seems ideally written for a young, fresh voice with a very high range, and such a, voice is best able to produce the proper effect in the vocal _ laughter on the high C’s and D’s and E flats. — Massenet was an excellent judge of singing and of individual singing quality. When I was rehearsing Manon he once said to me: ‘You have the ideal singer’s mouth; it opens naturally!’ And in Grisélidis, which he really wrote for a dramatic soprano, he told me not to try for dramatic effects, but to base my interpretation of the part on lyric singing, and concentrate all the brilliance and purity of my voice in the high register. There are a number of soprano rdéles which may be sung in a lighter or a heavier vocal style, and the individual singer should always choose the manner in which she can make the most natural effect. Aida is a réle of this kind, and so is the réle of Marguerite in ‘Faust.’ In the selfsame notes the dramatic soprano will get more effect out of the lower register, and the lyric soprano out of the higher one.

“I know that Massenet was supposed to pay court to every singer who ever studied his rdles with him. But he was always the gentleman, and I can say from my own experience that he did not persist in an attempt to flirter when he was not encouraged. Once, when I first was rehearsing Manon with him, I happened to drop my handkerchief. He immediately picked it up, pressed it to his face, and began paying me some delightfully extravagant compliments on the perfume I used. I merely took it from him and replied: ‘Yes, cher maitre, that is the perfume I use, and how did you say you wished this passage sung? He realized at once that I was not interested in flirting with him, but in grasping my role, and after that he never tried to obtrude a more personal note in our musical work. Of course, in many cases, he was encouraged. I know of one famous singer who when she first came to him, and he did not seem to react to her personal charm, stopped singing and said: ‘Mon cher maitre, I must be very homely!’ “What makes you say that?’ asked Massenet. ‘Well, you do not pay me the compliment of trying to flirt with me,’ she answered.

HINTS ON RECITAL SINGING AND OPERATIC SONG IN RECITAL

“The better a singer can sing opera, the better she will be able to sing in concert; though for both opera and concert, contrary to the idea some ~ have, a couple of years of study are not enough to supply areal foundation. And the recital singer — needs strength and temperament just as the opera singer does. If she is cold, if she cannot lose herself in the interpretation of an operatic role, she will also bore her audiences on the recital stage, for temperament and dramatic feeling are all the more needed there. Dresses and wigs will not ‘put over’ a réle in opera, nor ‘singing in costume’ in a recital. A beautiful voice, properly handled, is a beautiful voice, and remains such, both on the dramatic and the concert stage. I cannot see why fine distinctions should be drawn. Yes, I believe the operatic aria has a legitimate place on the recital program. Too often, however, one or two hackneyed arias are sung. There is the ‘Mad Scene’ with flute obbligato from . ‘Lucia’ for instance. It is a fine coloratura aria but done to death. Why not use some of the effective coloratura arias from Bellini’s ‘I Puritani, Rossini’s ‘La Gazza Larda,’ or both Rossini’s and Verdi’s ‘Otello’? Some big arias are sure to fall flat. In the ‘Mad Scene,’ when used in recital, the flute is somewhat commonplace, and even the brilliant “Jewel Song’ from ‘Faust’ usually loses by being taken out of the operatic frame. Almost anything by Mozart, on the other hand, is appropriate. The Massenet ‘Fabilau’ from ‘Manon,’ which I have already mentioned, is, perhaps, an almost ideal concert number, and makes a fine big introductory aria for a recital program. Each singer should choose her opera songs for concert use ~ herself, for no one knows as well as she does what is best suited for her voice. I think it a great mistake to sing the Puccini opera airs in concert, because ‘La Bohéme,’ ‘Madame Butterfly,’ and other scores are so frequently given, and their melodies so often heard on the stage that audiences do not care for them on the concert platform.

“Concert singing in one sense strains the singer more than opera singing. In opera the singer has various opportunities to rest and conserve her strength during the performance; she is not singing all the time. The concert singer, however, must sing steadily through her program and cannot pause long between her groups. The real art in recital singing is to use the voice conservatively, in a proper choice of songs, so that the climaxing group and the climaxing songs reveal it at its best—but it is unfortunate that the critics leave after the second or third number as they do not hear the singers at their best.

MAKING ONE’S OWN CADENZAS

“Even to-day, when the operatic coloratura aria is merely an incident of the recital program, the singer should be able, in a florid aria of the older type, to develop her own cadenza. When I was a girl I studied all those other subjects which do so much to round out the singer’s art. Every week I had lessons in walking on the stage, acting — Moliere and Racine — and in gesture. I studied piano and harmony, with the result that I can sit down at any time and get a clear idea of a new song without calling upon an accompanist. And—as a rule—I have written my own cadenzas. In the Italian operatic aria by Bellini, Rossini or Donizetti, the cadenza is usually left to the individual singer’s discretion. The custom is to introduce it after the repetition of the first vocal theme. I know that when Patti sang ‘Una voce poco fa’ for Rossini, she did not take the trouble to even sing the first theme completely, but introduced the cadenza then and there, and Rossini said: ‘Very lovely, but what aria did you sing. . . .? Every really trained singer should be able to improvise or write her own cadenzas. Sometimes a distinguished composer writes one for a singer and such a one is usually worth treasuring. I have a wonderfully effective cadenza written in the modern style, through a series of keys, with the flute, for the ‘Lucia’ aria, which Paul Vidal wrote for me, and it is the original manuscript which I have transferred to my copy of the score. I value it highly. Reynaldo Hahn, by the way, has written melodies for recital use which are very intimate and appealing, if sung with the voix blanche, the soft, relaxed mezza voce tone. Paul Vidal, too, has written lovely songs for recital, though they demand a good deal of the artist. An ideal coloratura song for the recital stage, when a chorus is available, is Saint-Saéns’ ‘Le Rossignol’ from his cantata ‘La Nuit.’

WHAT MAKES A GOOD SINGER

“I think that not one quality alone, but a number are required to make a good singer. The voice has to be there, no one can ‘make’ it. Then health, strength, temperament, love for singing, and—patience! American parents, it seems to me, and American students only too often lack this essential. Girls want to make a début at the Metropolitan after six months of study. I know that it cost me four years of strenuous work before I could venture to appear in the lighter roles of the soprano repertory. And I believe in the national conservatory idea subventioned by the State, as it is carried out in France and other European countries—not that the really qualified private teacher should be diseounted— where the student can follow systematic and complete courses in singing, and all the necessary subjects connected with singing, under the greatest masters of the art, native and foreign.”

#classical music#opera#music history#bel canto#composer#classical composer#aria#classical studies#maestro#chest voice#Alice Verlet#lyric coloratura soprano#lyric soprano#coloratura soprano#coloratura#soprano#His Majesty's Theatre#Her Majesty's Theatre#Paris Opéra#Opéra-Comique#Carnegie Hall#classical musician#classical musicians#classical history#history of music#historian of music#musician#musicians#diva#prima donna

1 note

·

View note

Text

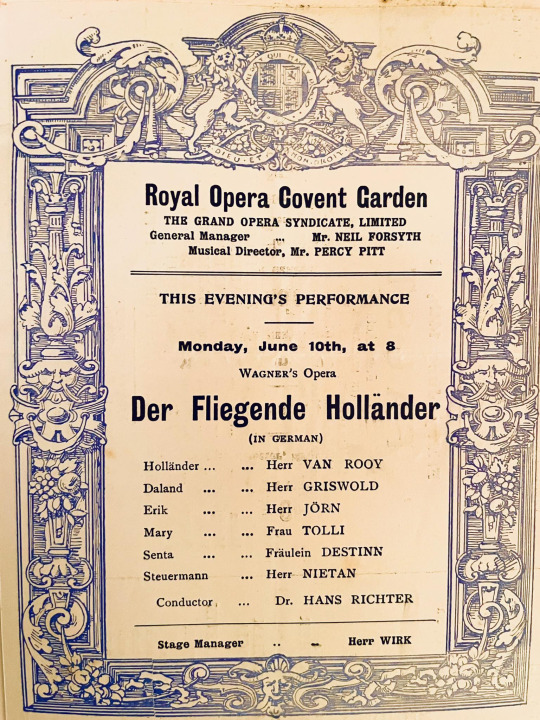

Today a original castlist from June 1907. Wagner's „Der fliegende Holländer“ at the Royal Opera Covent Garden.

#classical music#opera#music history#bel canto#composer#classical composer#aria#classical studies#maestro#chest voice#Der fliegende Holländer#Richard Wagner#Royal Opera House#Covent Garden#Cast#poster#classical musician#classical musicians#classical history#history of music#historian of music#musician#musicians#diva#prima donna#Golden Age of Opera#Golden Days of Opera#Golden Age

1 note

·

View note

Text

Alice Verlet sings "O beau pays de la Touraine" from "Les Huguenots", recorded c. 1915.

From Men and Matters A Magazine of Fact, Fancy & Fiction (1897):

The concert of Mademoiselle Alice was certainly a rare musical Mlle Verlet is gifted with a voice tar above the ordinary and almost indescribable in its mingled of richness and delicacy. Her low notes suggest passion and and seem to awaken some dead memory in the heart of the while her higher notes are the sublime thrill of a mocker peeps from out his leafy nest in quiet hush of a morning in spring. Verlet does not sing two bars a morceau before she wins the heart the entire audience. The notes to flow right from her heart so sympathetic does she seem to be with nature of the selection she may to sing Mlle Verlet's support of piano players violinists and cel lists are all to be desired in their thorough training and culture in con nection with the instrument of their adoptiou while their technique caused no little appreciation.

#classical music#opera#music history#bel canto#composer#aria#classical composer#classical studies#maestro#chest voice#Alice Verlet#coloratura soprano#coloratura#soprano#O beau pays de la Touraine#Les Huguenots#Giacomo Meyerbeer#His Majesty's Theatere#Her Majesty's Theatere#Paris Opéra#Opéra-Comique#Carnegie Hall#classical musician#classical musicians#classical history#historian of music#history of music#musician#musicians#diva

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Today a rare program from 1877 Wagner „Lohengrin“ in New Orleans.

#classical music#opera#music history#bel canto#composer#classical composer#aria#classical studies#maestro#chest voice#Lohengrin#Richard Wagner#cast#program#classical musician#classical musicians#classical history#history of music#historian of music#musician#musicians#diva#prima donna#Golden Age#Golden Age of Opera#Golden Days of Opera#poster

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

From Vocal mastery; talks with master singers and teachers, comprising interviews with Caruso, Farrar, Maurel, Lehmann, and others by Brower, Harriette, 1869-1928:

ANTONIO SCOTTI

TRAINING AMERICAN SINGERS FOR OPERA

A SINGER of finished art and ripe experience is Antonio Scotti. His operatic career has been rich in development, and he stands today at the top of the ladder, as one of the most admired dramatic baritones of our time.

One of Naples' sons, he made a first appearance on the stage at Malta, in 1889. Successful engagements in Milan, Rome, Madrid, Russia and Buenos Aires followed. In 1899 he came to London, singing Don Giovanni at Covent Garden. A few months thereafter, he came to New York and began his first season at the Metropolitan. His vocal and histrionic gifts won instant recognition here and for the past twenty years he has been one of the most dependable artists of each regular season.

CHARACTERIZATION

With all his varied endowments, it seldom or never falls to the lot of a baritone to impersonate the lover; on the contrary it seems to be his metier to portray the villain. Scotti has been forced t^ hide his true personality behind the mask . a Scarpia, a Tonio, an lago, and last bu* .ot least, the most repulsive yet subtle o^ all his villains — Chim-Fang, in L'Oracoio. Perhaps the most famous of them all is Scarpia. But what a Scarpia, the quintessence of the polished, elegant knave! The refinement of Mr. Scotti's art gives to each role distinct characteristics which separate it from all the others.

OPPORTUNITY FOR THE AMERICAN SINGER

Mr. Scotti has done and is doing much for the young American singer, by not only drilling the inexperienced ones, but also by giving them opportunity to appear in opera on tour. To begin this enterprise, the great baritone turned impresario, engaged a company of young singers, most of them Americans, and, when his season at the Metropolitan was at an end, took this company, at his own expense, on a southern trip, giving opera in many cities.

Discussing his venture on one occasion, Mr. Scotti said:

"It was an experiment in several ways. First, I had an all- American company, which was indeed an experiment. I had some fine artists in the principal roles, with lesser known ones in smaller parts. With these I worked personally, teaching them how to act, thus preparing them for further career in the field of opera. I like to work with the younger and less experienced ones, for it gives me real pleasure to watch how they improve, when they have the opportunity.

"Of course I am obliged to choose my material carefully, for many more apply for places than I can ever accept.

ITALIAN OPERA IN AMERICA

"So closely is Italy identified with all that pertains to opera," he continued, "that the question of the future of Italian opera in America interests me immensely. It has been my privilege to devote some of the best years of my life to singing in Italian opera in this wonderful country of yours. One is continually impressed with the great advance America has made and is making along all musical lines. It is marvelous, though you who live here may not be awake to the fact. Musicians in Europe and other parts of the world, who have never been here, can form no conception of the musical activities here.

"It is very gratifying to me, as an Italian, to realize that the operatic compositions of my country must play an important part in the future of American musical art. It seems to me there is more intrinsic value — more variety in the works of modern Italian composers than in those of other nations. We know the operas of Mozart are largely founded on Italian models.

"Of the great modern Italian composers, I feel that Puccini is the most important, because he has a more intimate appreciation of theatrical values. He seems to know just what kind of music will fit a series of words or a scene, which will best bring out the dramatic sense. Montemezzi is also very great in this respect. This in no way detracts from what Mascagni, Leoncavallo and others have accomplished. It is only my personal estimate of Puccini as a composer. The two most popular operas today are A'ida and Madame Butterfly, and they will always draw large audiences, although American people are prone to attend the opera for the purpose of hearing some particular singer and not for the sake of the work of the composer. In other countries this is not so often the case. We must hope this condition will be overcome in due time, for the reason that it now often happens that good performances are missed by the public who are only attracted when some much heralded celebrity sings."

AMERICAN COMPOSERS

Asked for his views regarding American operatic composers, Mr. Scotti said:

"American composers often spoil their chances of success by selecting uninteresting and uninspired stories, which either describe some doleful historic incident or illustrate some Indian legend, in which no one of to-day is interested, and which is so far removed from actual life that it becomes at once artificial, academic and preposterous. Puccini spends years searching for suitable librettos, as great composers have always done. When he finds a story that is worthy he turns it into an opera. But he will wait till he discovers the right kind of a plot. No wonder he has success. In writing modern music dramas, as all young Americans endeavor to do, they will never be successful unless they are careful to pick out really dramatic stories to set to music."

OPERATIC TRAINING

On a certain occasion I had an opportunity to confer with this popular baritone, and learn

more in regard to his experiences as impresario. This meeting was held in the little back office of the Metropolitan, a tiny spot, which should be — and doubtless is — dear to every member of the company. Those four walls, if they would speak, could tell many interesting stories of singers and musicians, famed in the world of art and letters, who daily pass through its doors, or sit chatting on its worn leathercovered benches, exchanging views on this performance or that, or on the desirability or difficulty of certain roles. Even while we were in earnest conference, Director Gatti-Casazza passed through the room, stopping long enough to say a pleasant word and offer a clasp of the hand. Mr. Guard, too, flitted by in haste, but had time to give a friendly greeting.

Mr. Scotti was in genial mood and spoke with enthusiasm of his activities with a favorite project— his own opera company. To the question as to whether he found young American singers in too great haste to come before the public, before they were sufficiently prepared, thus proving they were superficial in their studies, he replied:

"No, I do not find this to be the case. As a general rule, young American singers have a good foundation to build upon. They have

good voices to start with; they are eager to learn and they study carefully. What they lack most — those who go in for opera I mean — is stage routine and a knowledge of acting. This, as I have said before, I try to give them. I do not give lessons in singing to these young aspirants, as I might in this way gain the enmity of vocal teachers; but I help the untried singers to act their parts. Of course all depends on the mentality — how long a process of training the singer needs. The coloratura requires more time to perfect this manner of singing than others need; but some are much quicker at it than others.

"It is well I am blessed with good health, as my task is extremely arduous. When on tour, I sing every night, besides constantly rehearsing my company. We are ninety in all, including our orchestra. It is indeed a great undertaking. I do not do it for money, for I make nothing personally out of it, and you can imagine how heavy the expenses are; four thousand dollars a week, merely for transportation. But I do it for the sake of art, and to spread the love of modern Italian opera over this great, wonderful country, the greatest country for music that exists to-day. And the plan succeeds far beyond my hopes; for where we gave one performance in a place, we now, on our second visit, can give three — four. Next year we shall go to California.

"So we are doing our part, both to aid the young singer who sorely needs experience and to educate the masses and general public to love what is best in modern Italian opera!"

#classical music#opera#music history#bel canto#composer#classical composer#aria#classical studies#maestro#chest voice#Antonio Scotti#baritone#Metropolitan Opera#Met#Royal Opera House#Covent Garden#La Scala#Naples' son#classical musician#classical musicians#classical history#history of music#historian of music#muscian#musicians#diva#prima donna#Vocal mastery#Golden Days of Opera#Golden Age of Opera

0 notes

Text

This is a very rare original Program exactly 150 years ago June 12. 1875 Giuseppe Verdi conducted himself his Messa da Requiem at the K.& K. Hofoperntheater, Vienna.

#classical music#opera#music history#bel canto#composer#classical composer#aria#classical studies#maestro#chest voice#Giuseppe Verdi#Messa da Requiem#program#poster#classical musician#classical musicians#classical history#history of music#historian of music#musician#musicians#diva#prima donna#Golden Age#Golden Age of Opera#Golden Days of Opera

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Viking Song--Emilio de Gogorza, Baritone, 1918

The great Samuel Coleridge-Taylor song, superbly performed by Emilio de Gogorza, Recorded on June 6, 1918. Orchestra under the direction of Josef Pasternack.

From New York Times May 11, 1949:

Emilio de Gogorza, noted baritone and head of the vocal department of the Curtis Institute of Music in Philadelphia from 1926 to 1940, died yesterday of a heart attack in his studio at 110 West Fifty-fifth Street. He was 76 years old.

Born in Brooklyn of Spanish parents, he was taken to Europe as an infant. After studying in France and England, he returned to the United States at 21 to assist Mme. Marcella Sembrich, Metropolitan Opera soprano, in recitals throughout the country.

He was the first artistic director of the Victor Talking Machine Company. After retiring from a brilliant singing career, he devoted his time to coaching vocalists. Among his students were Conrad Thibault, John Brownlee, Benjamin DeLoche, Miss Margaret Speaks and Miss Leslie Frick. He also was associated with the American Theatre Wing.

Mr. Gogorza leaves his widow, former Mme. Emma Eames, who for seventeen years was a leading soprano of the Metropolitan Opera Company.

Mr. de Gogorza possessed a light lyric baritone voice in which their duets were warmly received. Emma was careful not to choose any difficult duets with him because he had a light voice with no top to speak of. Later he resigned the concert hall to work with Victor Record Company, in Camden, New Jersey, and he was most successful.

#classical music#opera#music history#bel canto#composer#classical composer#aria#classical studies#maestro#chest voice#Emilio de Gogorza#baritone#Victor Talking Machine Company#Samuel Coleridge-Taylor#Viking Song#song#classical musician#classical musicians#classical history#history of music#historian of music#musician#musicians#diva#prima donna#Golden Age#Golden Age of the Opera#Golden Days of the Opera#poem#poetry

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

161 years ago Richard Strauss was born in Munich June 11.1864. Here you see a original Concert program 1915 conducted by him and a Papercut from 1933.

#classical music#opera#music history#bel canto#composer#classical composer#aria#classical studies#maestro#chest voice#Richard Strauss#Concert#program#conductor#classical musician#classical musicians#classical history#historian of music#history of music#musician#musicians#diva#prima donna#Golden Age#Golden Age of Opera#Golden Days of Opera

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

160 years ago June 10.1865 Richard Wagner „Tristan und Isolde“ premiered in Munich at Nationaltheater München. 21 years later 1886 the first performances presented at the Bayreuther Festspiele - Bayreuth Festival. Here you see original Poster from 1886.

#classical music#opera#music history#bel canto#composer#classical composer#aria#classical studies#maestro#chest voice#Tristan und Isolde#Richard Wagner#classical musician#classical musicians#classical history#history of music#historian of music#musician#muscians#diva#prima donna#program#poster#cast#Golden Age#Golden Age of Opera#Golden Days of Opera#Bayreuth Festival

2 notes

·

View notes