#THE SPECIAL OPERATIONS EXECUTIVE (SOE) IN FRANCE 1941-1944

Text

From Facebook 4/8/23

In May 1944, a 23-year-old British secret agent named Phyllis Latour Doyle parachuted into occupied Normandy to gather intelligence on Nazi positions in preparation for D-Day. As an agent for the British Special Operations Executive (SOE), Doyle – who celebrates her 102nd birthday today – secretly relayed 135 coded messages to the British military before France's liberation in August. She took advantage of the fact that the Nazi occupiers and their French collaborators were generally less suspicious of women, using the knitting she carried as a way to hide her codes. For seventy years, Doyle's contributions to the war effort were largely unheralded, but she was finally given her due in 2014 when she was awarded France's highest honor, the Chevalier of the Legion of Honour.

Doyle first joined the Women's Auxiliary Air Force at age 20 in 1941 to work as a flight mechanic, but SOE recruiters spotted her potential and offered her a job as a spy. A close family friend – her godmother's father who she viewed as her grandfather – had been shot by the Nazis and she was eager to support the war effort however she could. Doyle immediately accepted the SOE's offer and began an intensive training program. In addition to learning about encryption and surveillance, trainees also had to pass grueling physical tests. Doyle described how they were taught by a cat burglar who had been released from jail on "how to get in a high window, and down drain pipes, how to climb over roofs without being caught."

She first deployed to Aquitaine in Vichy France where she worked for a year as a spy using the codename Genevieve. Her most dangerous mission, however, began on May 1, 1944 when she jumped out of a U.S. Air Force bomber and landed behind enemy lines in Nazi-occupied Normandy. Using the codename Paulette, she posed as a poor teenage French girl. Doyle used a bicycle to tour the region, often under the guise of selling soap, and passed information to the British on Nazi positions using coded messages. In an interview with the New Zealand Army News magazine, she described how risky the mission, noting that "The men who had been sent just before me were caught and executed. I was told I was chosen for that area [of France] because I would arouse less suspicion."

She also explained how she concealed her codes: "I always carried knitting because my codes were on a piece of silk – I had about 2,000 I could use. When I used a code I would just pinprick it to indicate it had gone. I wrapped the piece of silk around a knitting needle and put it in a flat shoe lace which I used to tie my hair up." Coded messages took a half an hour to send, and the Germans could identify where a signal was sent from in an hour and a half, so Doyle moved constantly to avoid detection. At times, she stayed with Allied sympathizers, but often she had to sleep in forests and forage for food. During her months in Normandy, Doyle sent 135 secret messages conveying invaluable information on Nazi troop positions, which was used to help Allied forces prepare for the Normandy landings on D-Day and during the subsequent military campaign. Doyle continued her mission until France's liberation in August 1944.

Following the war, Doyle eventually settled in New Zealand where she raised four children. It was only in the past 15 years that she told them about her career as a spy. In presenting the Chevalier of the Legion of Honour to Doyle, French Ambassador Laurent Contini commended her courage during the war, stating: "I have deep admiration for her bravery and it will be with great honor that I will present her with the award of Chevalier de l’Ordre National de la Légion d’Honneur, France’s highest decoration."

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ww2 bomber crew losses

Original Source: Various sources including rolls of honour, IWGC registers etc. The North American B-25 Mitchell heavy bomber with a crew of six was one of 52 air losses with missing personnel in the area during WW 2, mostly during 1943 as the Allies pushed into southeastern. Some records will contain more information than that listed above. Please be aware that due to the way we collate, and cross reference our databases, Records in this collection are likely to include the following: 8 Group controlled the Pathfinder squadrons. The Pathfinders were a group of elite, specially trained and experienced crews who flew ahead and with the main bombing forces, and marked the targets with flares and special marker-bombs. The other was the ‘centimetric’ navigation equipment H2S radar carried in the bombers themselves. One was external radio navigation aids, as exemplified by Gee and the later highly-accurate Oboe systems. The technical aids to navigation took two forms. One was the use of a range of increasingly sophisticated electronic aids to navigation and the other was the use of specialist Pathfinders. Military aircraft losses during WWII 1940-1941 WWII 1942 WWII 1943 WWII 1944-1945 Abbreviations : 138(SOE))sq 138 Special Operation Executive Squadron, FLAK Flugabwerekanone (Antiaircraft Gun), Flt.Off. Bomber Command solved its navigational problems using two methods. Answer (1 of 11): The US 8th Air Force, which flew daylight missions over Europe, had a 19 death rate, if you survived being shot down, you had a 17 chance of become a POW. coecoei liquor substitute the ocean club seaside heights how many ww2 bomber crews completed 25 missions. how many ww2 bomber crews completed 25 missions. It was a critical part of solving the navigational and aiming problems experienced. how many ww2 bomber crews completed 25 missionszones of regulation powerpoint for students. 8 Group, also known as the Pathfinder Force, was activated on 15 August 1942. At its peak strength, 6 Group consisted of 14 operational RCAF bomber squadrons, and 15 different squadrons served with the group. 6 Group, which was activated on 1 January 1943, was unique among Bomber Command groups, in that it was not an RAF unit it was a Canadian unit attached to Bomber Command. A 1942 study determined that relatively low velocity projectiles such as deflected flak fragments or shattered pieces of aircraft. Many squadrons and personnel from Commonwealth and other European countries were distributed throughout Bomber Command. 8 (Pathfinder) Group from existing squadrons. 6 Group and the Pathfinder Force was expanded to form No. Bomber Command also gained two new groups during the war: the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) squadrons were organised into No. 2 Group consisted of light and medium bombers who, although operating both by day and night, remained part of Bomber Command until 1943, when it was removed to the control of Second Tactical Air Force, to form the light bomber component of that command. It was, however, returned to Bomber Command control after the evacuation of France, and reconstituted. Bomber Command comprised a number of Groups. Over 41,000 of the total are presumed lost at sea.Bomber Command Operational Losses in the European Theatre of War covering both Aircraft and Aircrew 1939-1945. military personnel, including 72,350 from World War II, 7,550 from the Korean War and 1,584 from the Vietnam War. Worldwide, there are more than 81,600 missing U.S. The evidence, which includes possible human bones as well as potential remnants of the aircraft, has been transported to a laboratory in the U.S. In the intervening decades, the crash site "like most others in the Mediterranean region, was scavenged for metal, the land restored to its original use,'' Vella said. military officials, but the other five airmen remained missing. One crew member was located immediately and buried in the town's cemetery. aircraft about two kilometers (just over a mile) from the Sciacca airport, Vella said. A German military report documented the crash of a U.S. It was shot down as it targeted a camouflaged German airstrip amid olive groves and pastureland on July 10, 1943. The North American B-25 Mitchell heavy bomber with a crew of six was one of 52 air losses with missing personnel in the area during WWII, mostly during 1943 as the Allies pushed into southeastern Sicily. "We owe (their) families accurate answers,'' Vella told the Associated Press Thursday. This year's dig uncovered wreckage "consistent only to a B-25 aircraft,'' said archaeologist Clive Vella, the scientific director of the expedition, contributing to hopes that any confirmed remains would be linked to the missing crew. The site near Sciacca was identified in 2017 by investigators using historical records and metal detectors. The six-week dig that ended this week was carried out by a team from the Pentagon's Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency, which locates and identifies missing U.S.

0 notes

Photo

THE SPECIAL OPERATIONS EXECUTIVE (SOE) IN FRANCE, 1941-1944

© IWM (HU 47952)

Portrait of Christine Granville (Countess Krystyna Skarbek) in Algiers, 1944.

#Christine Granville#Countess Krystyna Skarbek#Algiers#1944#THE SPECIAL OPERATIONS EXECUTIVE (SOE) IN FRANCE 1941-1944#IWM (HU 47952)#Photographs#Second World War#Unknown#HU 47952

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Virginia Hall was an American woman who served as a clandestine agent in Europe during WW2.

Initially, she worked for the British Special Operations Executive (SOE). In August 1941 she was sent to Vichy France, the French regime that cooperated with Germany.

Once on the ground in Lyon, Hall had to learn quickly. She essentially self-trained in establishing contacts and relationships, identifying threats and bribery candidates, creating lines of communication, managing personnel and developing security protocols.

As it happened, Hall proved to be an excellent undercover agent and she soon became the nexus of a clandestine intelligence gathering network codenamed Heckler.

For 15 months, Hall oversaw Heckler, remaining undetected even as other networks work rooted out and dozens of SOE agents were captured.

In July 1942, Hall orchestrated the escape from prison of a dozen SOE agents captured in October, an incident that earned her the full attention of the Gestapo who sent 500 agents to track the spy known as ‘the limping lady’ (due to her prosthetic leg)

Heckler was finally compromised by a German agent who had infiltrated the a section of the French resistance in August 1942. By November, Hall could sense something was amiss. This, coupled with the German occupation of Vichy France, led her to slip away without telling anyone in Heckler she was leaving.

After returning to England, the SOE would not send her back because she had been compromised. Keen to get back in the game, she instead joined the newly arrived American Office of Strategic Services (OSS), the forerunner of the CIA.

She returned to France in 1944, tasked with making contact with the French resistance groups known as Maquisards. She was responsible for organising, financing, supplying and directing these groups in the Haute-Loire region. So successful at this task was she that by the time a second team arrived in August 1944, the Germans had already been cleared out of the region.

For her service she was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross, the only such award given to a civil woman during the war.

Hall later served in the CIA until 1966, when she retired. She died in 1982, having told virtually no one of her remarkable WW2 career.

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

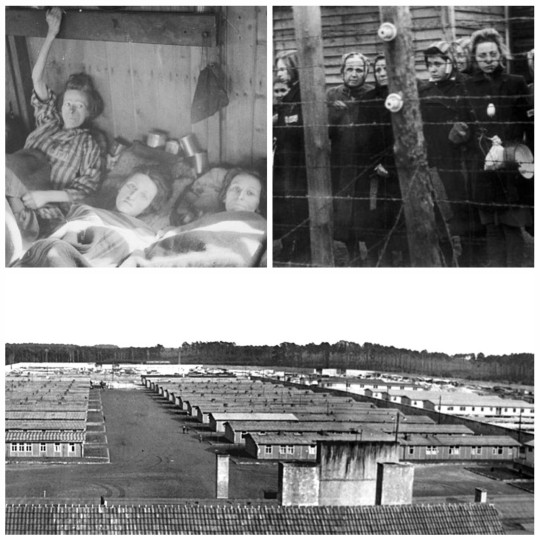

• Ravensbrück Concentration Camp

Ravensbrück was a German concentration camp exclusively for women from 1939 to 1945, located in northern Germany, 90 km (56 mi) north of Berlin at a site near the village of Ravensbrück (part of Fürstenberg/Havel).

Construction of the camp began in November 1938 by the order of the SS leader Heinrich Himmler and was unusual in that it was intended exclusively to hold female inmates. Ravensbrück first housed prisoners in May 1939, when the SS moved 900 women from the Lichtenburg concentration camp in Saxony. Eight months after the start of World War II the camp's maximum capacity was already exceeded. It underwent major expansion following the invasion of Poland. By the summer of 1941 with the launch of Operation Barbarossa an estimated total of 5,000 women were imprisoned, who were fed gradually decreasing hunger rations. By the end of 1942, the inmate population of Ravensbrück had grown to about 10,000. The greatest number of prisoners at one time in Ravensbrück was probably about 45,000. Between 1939 and 1945, some 130,000 to 132,000 female prisoners passed through the Ravensbrück camp system. According to Encyclopædia Britannica, about 50,000 of them perished from disease, starvation, overwork and despair; some 2,200 were killed in the gas chambers. During the first year of their stay in the camp, from August 1940 to August 1941, roughly 47 women died. During the last year of the camp's existence, about 80 inmates died each day from disease or famine-related causes.

Although the inmates came from every country in German-occupied Europe, the largest single national group in the camp were Polish. In the spring of 1941, the SS authorities established a small men's camp adjacent to the main camp. The male inmates built and managed the gas chambers for the camp in 1944. There were children in the camp as well. At first, they arrived with mothers who were Romani or Jews incarcerated in the camp or were born to imprisoned women. There were few children early on, including a few Czech children from Lidice in July 1942. Later the children in the camp represented almost all nations of Europe occupied by Germany. Between April and October 1944 their number increased considerably, consisting of two groups. One group was composed of Romani children with their mothers or sisters brought into the camp after the Romani camp in Auschwitz-Birkenau was closed. The other group included mostly children who were brought with Polish mothers sent to Ravensbrück after the collapse of the Warsaw Uprising of 1944. Most of these children died of starvation.

Ravensbrück had 70 sub-camps used for slave labour that were spread across an area from the Baltic Sea to Bavaria. Among the thousands executed at Ravensbrück were four members of the British World War II organization Special Operations Executive (SOE): Denise Bloch, Cecily Lefort, Lilian Rolfe and Violette Szabo. Other victims included the Roman Catholic nun Élise Rivet, Elisabeth de Rothschild (the only member of the Rothschild family to die in the Holocaust), Russian Orthodox nun St. Maria Skobtsova, the 25-year-old French Princess Anne de Bauffremont-Courtenay, Milena Jesenská, lover of Franz Kafka, and Olga Benário, wife of the Brazilian Communist leader Luís Carlos Prestes. Among the survivors of Ravensbrück was author Corrie ten Boom, arrested with her family for harbouring Jews in their home in Haarlem, the Netherlands. SOE agents who survived were Yvonne Baseden and Eileen Nearne, who was a prisoner in 1944 before being transferred to another work camp and escaping. Englishwoman Mary Lindell and American Virginia d'Albert-Lake, both leaders of escape and evasion lines in France, survived. Ravensbrück survivors who wrote memoirs about their experiences include Gemma La Guardia Gluck, sister of New York Mayor Fiorello La Guardia, as well as Germaine Tillion, a Ravensbrück survivor from France who published her own eyewitness account of the camp in 1975. Approximately 500 women from Ravensbrück were transferred to Dachau, where they were assigned as labourers to the Agfa-Commando; the women assembled ignition timing devices for bombs, artillery ammunition and V-1 and V-2 rockets.

Camp commandants included SS-Standartenführer Günther Tamaschke from May 1939 to August 1939, SS-Hauptsturmführer Max Koegel from January 1940 till August 1942, and SS-Hauptsturmführer Fritz Suhren from August 1942 until the camp's liberation at the end of April 1945. Besides the male Nazi administrators, the camp staff included over 150 female SS guards assigned to oversee the prisoners at some point during the camp's operational period. Ravensbrück also served as a training camp for over 4,000 female overseers. The technical term for a female guard in a Nazi camp was an Aufseherin. The women either stayed in the camp or eventually served in other camps.

When a new prisoner arrived at Ravensbrück she was required to wear a colour-coded triangle (a winkel) that identified her by category, with a letter sewn within the triangle indicating the prisoner's nationality. For example, Polish women wore red triangles, denoting a political prisoner, with a letter "P" (by 1942, Polish women became the largest national component at the camp). Soviet prisoners of war, and German and Austrian Communists wore red triangles; common criminals wore green triangles; and Jehovah's Witnesses were labelled with lavender triangles. Prostitutes, Romani, homosexuals, and women who refused to marry were lumped together, with black triangles. Jewish women wore yellow triangles but sometimes, unlike the other prisoners, they wore a second triangle for the other categories. For example, quite often it was for rassenschande ("racial pollution"). Some detainees had their hair shaved, such as those from Czechoslovakia and Poland, but other transports did not. In 1943, for instance, a group of Norwegian women came to the camp (Norwegians/Scandinavians were ranked by the Nazis as the purest of all Aryans). None of them had their hair shaved. Between 1942 and 1943, almost all Jewish women from the Ravensbrück camp were sent to Auschwitz in several transports, following Nazi policy to make Germany Judenrein (cleansed of Jews). Based on the Nazis' incomplete transport list Zugangsliste, documenting 25,028 names of women sent by Nazis to the camp, it is estimated that the Ravensbrück prisoner population's ethnic structure comprised: Poles 24.9%, Germans 19.9%, Jews 15.1%, Soviets 15.0%, French 7.3%, Romani 5.4%, other 12.4%. The Gestapo further categorised the inmates as: political 83.54%, anti-social 12.35%, criminal 2.02%, Jehovah's Witnesses 1.11%, rassenschande (racial defilement) 0.78%, other 0.20%.

One form of resistance was the secret education programmes organised by prisoners for their fellow inmates. All national groups had some sort of programme. The most extensive were among Polish women, wherein various high school-level classes were taught by experienced teachers. In 1939 and 1940, camp living conditions were acceptable: laundry and bed linen were changed regularly and the food was adequate, although in the first winter of 1939/40, limitations began to be noticeable. Not long after conditions quickly deteriorated. Starting in the summer of 1942, medical experiments were conducted without consent on 86 women; 74 of them were Polish inmates. Two types of experiments were conducted on the Polish political prisoners. The first type tested the efficacy of sulfonamide drugs. These experiments involved deliberate cutting into and infecting of leg bones and muscles with virulent bacteria, cutting nerves, introducing substances like pieces of wood or glass into tissues, and fracturing bones. Out of the 74 Polish victims, called Kaninchen, Króliki, Lapins, or Rabbits by the experimenters, five died as a result of the experiments, six with unhealed wounds were executed, and (with assistance from other inmates) the rest survived with permanent physical damage.

All inmates were required to do heavy labor ranging from strenuous outdoor jobs to building the V-2 rocket parts for Siemens. The SS also built several factories near Ravensbrück for the production of textiles and electrical components. The women forced to work at Ravensbrück concentration camp's industries used their skills in sewing and their access to the factory to make soldiers' socks. They purposely adjusted the machines to make the fabric thin at the heel and the toes, causing the socks to wear prematurely at those places when the German soldiers marched. For the women in the camp, it was important to retain some of their dignity and sense of humanity. Therefore, they made necklaces, bracelets, and other personal items, like small dolls and books, as keepsakes. These personal effects were of great importance to the women and many of them risked their lives to keep these possessions. In January 1945 the SS also transformed a hut near the crematorium into a gas chamber where the Germans gassed several thousand prisoners before the camp's liberation in April 1945; in particular they killed some 3600 prisoners from the Uckermark police camp for "deviant" girls and women, which was taken under the control of the Ravensbrück SS at the start of 1945. In January 1945, prior to the liberation of the remaining camp survivors, an estimated 45,000 female prisoners and over 5,000 male prisoners remained at Ravensbrück, including children and those transported from satellite camps only for gassing, which was being performed in haste.

With the Soviet Red Army's rapid approach in the spring of 1945, the SS leadership decided to remove as many prisoners as they could, in order to avoid leaving live witnesses behind who could testify as to what had occurred in the camp. At the end of March, the SS ordered all physically capable women to form a column and exit the camp in the direction of northern Mecklenburg, forcing over 24,500 prisoners on a death march.Some 2,500 ethnic German prisoners remaining were released, and 500 women were handed over to officials of the Swedish and Danish Red Cross shortly after the evacuation. On April 30th, 1945, fewer than 3,500 malnourished and sickly prisoners were discovered alive at the camp when it was liberated by the Red Army. The survivors of the death march were liberated in the following hours by a Soviet scout unit. The SS guards, female Aufseherinnen guards and former prisoner-functionaries with administrative positions at the camp were arrested at the end of the war by the Allies and tried at the Hamburg Ravensbrück trials from 1946 to 1948. 16 of the accused were found guilty of war crimes and crimes against humanity and sentenced to death.

On the site of the former concentration camp there is a memorial today. In 1954, the sculptor Will Lammert was commissioned to design the memorial site between the crematorium, the camp wall, and Schwedtsee Lake. Up to his death in 1957, the artist created a large number of sculpted models of women. Since 1984, the former SS headquarters have housed the Museum des antifaschistischen Widerstandskampfes (Museum of Anti-fascist Resistance). After the withdrawal from Germany of the Soviet Army, which up to 1993 had been using parts of the former camp for military purposes, it became possible to incorporate more areas of the camp into the memorial site. Today, the former accommodation blocks for the female guards are a youth hostel and youth meeting centre.

#second world war#world war 2#world war ii#history#wwii#german history#holocaust#nazi germany#long post#womens history#women in history

26 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Noorunissa Inayat Khan, Assistant Section Officer , Women's Auxiliary Air Force, was a second world war Allied Special Operations Executive (SOE) agent and the first female radio operator to be infiltrated into enemy occupied France to aid the Resistance.

The eldest of four children she was born on 2nd January 1914 in Moscow. Her musician and teacher father, Hazrat Inayat Khan came from a noble Indian Muslim family, her mother, Ora Ray Baker, was an American from Albuquerque, New Mexico.

On the outbreak of the First World War the family left Russia for London and lived in Bloomsbury. Inayat Khan attended nursery at Notting Hill and in 1920 they moved to France, settling in Sureness near Paris. After the death of her father in 1927, she took on the responsibility for her mother and younger siblings and studied child psychology at the Sorbonne and music at the Paris Conservatory. She began a career writing children's stories and in 1939 her book Twenty Jataka Tales was published in London. At the outbreak of the Second World War, the family fled to Bordeaux and from there by sea to England, landing in Falmouth Cornwall, June 1940.

Although Inayat Khan was influenced by the pacifist teachings of her father, she and her brother Vilayat decided to enlist to defeat Nazi tyranny. On 19th November 1940, she joined the WAAF and as an aircraft woman 2nd class was sent to be trained as a wireless operator. Upon assignment to a bomber training school in June 1941, she applied for a commission to relieve herself of the boring work and was promoted to Assistant Section Officer. Inayat Khan was recruited to join F (France) Section of the SOE in February and was posted to the Directorate of Air Intelligence. During her training she adopted the name "Nora Baker".

Her superiors were unconvinced of her suitability for secret warfare, nevertheless, her fluent French, wireless operation skills and the shortage of agents made her a candidate for service in Nazi-occupied France. On 16/17th June 1943, under the cover identity of ‘Jeanne-Marie Regnier’ code name 'Madeleine'/'Nurse' ASO/Ensign Inayat Khan was flown at night to a clandestine landing ground by Lysander.

She was met by Henri Déricourt and travelled to Paris to join the Prosper network. During the weeks following her arrival, the Gestapo made mass arrests in the Paris Resistance network to which she had been detailed. Although given the opportunity to return to England, she refused to abandon what had become the most dangerous posting in France, because she did not wish to leave her French comrades without communications and set about rebuilding her group. The Gestapo had a full description of her, but knew only her code name "Madeleine". They deployed considerable forces in their effort to catch her and thereby break the last remaining link with London.

As the only remaining wireless operator still at large in Paris, Inayat Khan continued to transmit messages from a network of agents she worked to keep intact. She was now the most wanted British agent in Paris. The Sicherheitsdienst (SD, Security Service, the intelligence agency of the Nazi SS) sent its officers to search for her at subway stations. With wireless detection vans in close pursuit, Inayat Khan could only transmit for 20 minutes at a time, constantly moving from place to place, she managed to escape capture.

After 3 months, she was betrayed to the SD and taken to their HQ in the Avenue Foch. The SD found her codes and attempted to send false messages imitating her, but Inayat Khan refused to co-operate. Her imprisonment and interrogation lasted over a month during which time she gave them no information but made two unsuccessful attempts at escape. She refused to sign a declaration that she would make no further attempts and she was subsequently the first agent to be sent to Germany for ‘safe custody’. She was considered a dangerous prisoner and was kept in solitary confinement, in complete secrecy, for 10 months at Pforzheim where her hands and feet were shackled. Although she remained uncooperative, her despair at her appalling confinement could be heard by other prisoners at night. By scratching ‘Nora Baker’ and her London address on the base of her mess cup, she was able to inform another inmate of her identity.

On 12 September 1944, Khan and three other SOE agents were moved to the Daschau Concentration Camp. In the early morning hours of 13th September 1944, the four women were beaten and executed by a shot to the back of the head by an SS officer. Their bodies were immediately burned in the crematorium. Her last word was "Liberté".

For her heroism and conspicuous courage in the face of extreme danger, over a period of more than 12 months, Assistant Section Officer Inayat-Khan was posthumously awarded the French Croix de Guerre and the British George Cross.

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

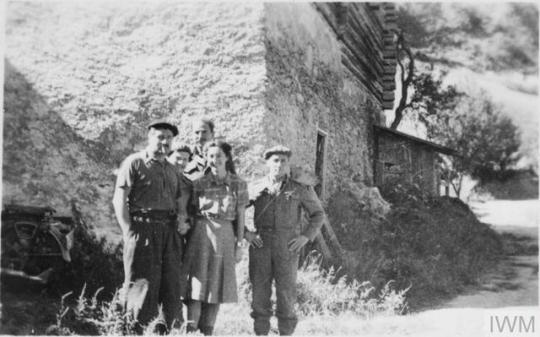

THE SPECIAL OPERATIONS EXECUTIVE (SOE) IN FRANCE, 1941-1944

© HU 57120

Members of the Maquis and British officers in the Queyras Valley, August 1944. Left to right: Gilbert Galletti, Captain Patrick O'Regan, Captain John Roper, Christine Granville (Countess Krystyna Skarbek) and Captain Leonard Hamilton (Blanchaert).

#Gilbert Galletti#Patrick O'Regan#John Roper#Christine Granville#Countess Krystyna Skarbek#Leonard Hamilton#Blanchaert#Maquis#British officers#Queyras Valley#August 1944#THE SPECIAL OPERATIONS EXECUTIVE (SOE) IN FRANCE 1941-1944#HU 57120#Photographs#Second World War#Cammaerts Francis Charles Albert#1944-08#SPECIAL FORCES CLUB COLLECTION

8 notes

·

View notes