#TTTE Spamcan

Text

Spamcan/D199 Headcanons & Analysis

While writing this fic and replying to folks’ lovely comments, I thought a lot about Spamcan and what makes him distinct to me. I feel like he’s different from the other rude diesel antagonists.

In my opinion, what sets him apart is that he has a companion. Bowler and Old Stuck Up arrive alone while Spamcan shares his trial with Bear. He also says “we” and “our controller” to Bear. There’s familiarity between them; he thinks of themselves as a package deal.

Bear validates this: “Shush! It’s their railway.” He doesn’t agree with Spamcan’s bigotry, but he still calls the NWR “their” railway. He’s aligning himself along lines of “us and them,” suggesting he and Spamcan are on the same “side” to some degree. He also considers themselves a package deal, even if he’s frustrated with it.

So how did these two become acquainted?

Well, Bear is a diesel-hydraulic engine — a type BR declares non-standard. Spamcan is a diesel-electric, safe for now from the cutter’s torch, but Bear’s position is much more fragile.

Considering what we see of Spamcan, he doesn’t seem like he’d befriend Bear for altruistic reasons. Yet he still refers to himself and Bear as a “we.” He even worries about what Bear thinks of him after he breaks down with his oil tankers.

And that’s what I think is at the root of this. Spamcan doesn’t care about Bear, but about what Bear thinks of him. He cares about maintaining a self-image that convinces Bear to stay with him, to keep following him.

Spamcan wants Bear to be dependent upon him.

I imagine their dynamic on BR was Spamcan demanding Bear’s loyalty in exchange for protection. And by protection, I mean dumping his work on Bear with the excuse of keeping him “out of sight, out of mind” from their controller. Bear didn’t have any better options, so he went along with it. Now he’s at the end of his rope.

But my pre-canon musings aside, do you see what I’m getting at? Spamcan’s one manipulative son of a gun!

He utilizes Bear’s threatened status to keep him close, to have someone who backs up what he says. His use of chummy plural pronouns is a strategy to wear down Bear’s sense of individuality. He tries to create camaraderie while also diminishing him, reducing him to a satellite in his orbit.

Spamcan is arrogant and boastful, but he has a degree of subtlety, too. That’s something that Bowler and Old Stuck Up never managed. The fact they came alone on their trials suggests they don’t have any followers or “friends” of their own, any of Spamcan’s finesse.

But you know who does manage some of that finesse? Diesel.

I like to think that Spamcan hears the story of Diesel’s trial. To him, it’s clear that Diesel worked the best when he flattered other engines and made himself indispensable to them. Messing with the trucks backfired in the end, but Spamcan would never do such a foolish thing. He can do one better than Diesel.

It’s not Spamcan’s plan to go to Sodor — he would rather stay on a “modernized” railway — but he figures it’s his duty to spread modernization. Like a “good diesel,” he volunteers himself with Bear for the trial. The Sodor engines will be on guard now, so who better to go with him than the fellow diesel to which he made himself invaluable? It’ll ensure someone has his back in hostile territory.

Spamcan’s miscalculation is in assuming that Bear will be grateful for recommending him to go on trial, winning him more points with him. But on BR, Bear was vulnerable. Now that he’s on Sodor, he has a chance of getting to safety. He doesn’t need Spamcan’s protection.

And every time Spamcan tries to appeal to him, he’s showing himself at his nastiest. Bear’s personal morals aside, if Spamcan hates “outdated” steam engines, how long will it be before he turns on “non-standard” diesels? How long will it be before Bear stops being useful to BR and to Spamcan?

When Bear tells Spamcan to shut up, he loses his only support right as he makes enemies out of every steam engine on this island. He’s alone and it’s all his own fault, all because he assumed he could manipulate his way out of any situation.

In that way, Spamcan isn’t too different from the other rude diesel antagonists. He fails because he’s arrogant and discriminatory. He fails because our protagonists resist swollen egos and prejudice where they see it.

But I like to think I’ve made a decent case for the ways he is different. I think he’s a bit subtler, a bit more manipulative than the others, even if he’s no more successful. What do you guys think? :)

#ttte#rws#the railway series#ttte headcanon#rws headcanon#my headcanons#ttte character analysis#rws character analysis#my analysis#ttte d199#ttte spamcan#ttte bear#ttte diesel#long post#I hope this makes sense#going to collapse into bed now okay good night

62 notes

·

View notes

Text

It's interesting to note that ERTL was the only Thomas & Friends merchandise line to do both 7101 and 199 from the untelevised RWS story Super Rescue. Hornby did 7101, while Wooden Railway and Take Along both did 199, but only ERTL did both diesels.

#thomas the tank engine#the railway series#ttte bear#TTTE Spamcan#Super Rescue#ERTL#hornby#wooden railway#take along#toy train

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Arthur got a bit hungry, so he grabbed a bite to eat lol

(And yea, i gave him a tuff of hair on him, I think it looks neat on him)

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

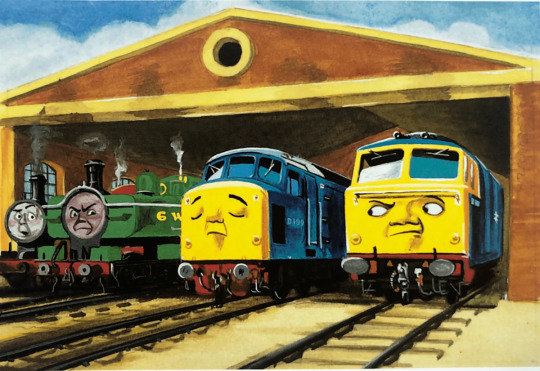

"So with 7101 growling in front, and Henry gamely puffing in the middle, the long cavalcade set out to the next big station."

From book 23: Enterprising Engines, based off of probably the most beloved Railway Series story to never get adapted for TV - Super Rescue!

#thomas the tank engine#ttte#ttte fanart#ttte thomas#thomas#thomas and friends#the railway series#henry the green engine#7101#d199#spamcan#super rescue#RWS

51 notes

·

View notes

Text

Percy: I say, you engines remember old “Spamcan”?

Gordon: Of course.

James: He was the worst.

Bear: I wonder where he ever wound up.

Henry: Who cares? Good riddance.

Duck: Scrapped by now, I imagine.

Percy: Yes, but apparently they first crashed him into a nuclear waste flask. On purpose.

Everyone: *horrified silence*

#... man#whaddaya gotta do to get THAT punishment#ttte#ttte spamcan#ttte bear#ttte script#the railway series#real true railway stuff#operation smash hit#goddammit British Railways why did you fucking HATE your early diesels#like your steam engines you just mass-murdered#but you reeeeeally dragged out the misery with their replacements#DIDN'T you#good grief

74 notes

·

View notes

Text

been a while since i made trainz stuff

cuz ya know, wanted to try out the new Bear model from Ashford Works

#they be angrey#thomas and friends#duck the great western engine#james the splendid engine#d199#spamcan#bear ttte

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Operation Smash Hit

Hahaha - this is gonna be dark

From Wikipedia. The Free Encyclopedia

Operation Smash Hit was an intentional train crash that occurred on 17 July, 1984 at the Old Dalby Test Track in Old Dalby, Leicestershire, United Kingdom.

The crash, organized by The Central Electricity Generating Board (CEGB) and undertaken by British Rail Engineering Limited (BREL), involved a high speed collision between a 4 vehicle test train and stationary flatbed wagon.

The test, conducted to showcase the structural stability of a nuclear fuel rod flask in the event of a catastrophic collision, was notable for the forced participation and death of the five vehicles involved and for the international backlash that followed.

This article is part of a series on Locomotive Rights in The United Kingdom:

Locomotive Rights Movements in The United Kingdom

Pre-British Rail Locomotive Scrapping in The United Kingdom

Sentient Non-Locomotive Rolling Stock in The United Kingdom

Beeching Cuts

British Rail Modernization Plan

Mass Scrapping of British Rail Steam Locomotives (1955-1970)

British Locomotive Civil War

Woodham Brothers Ltd

John Cashmore Ltd

British Locomotive Exodus (1960-1999)

The British Locomotive Diaspora

Non-Standard Diesel Locomotive Purge

First Generation Diesel Locomotive Purge

Operation Smash Hit

Second Generation Diesel Locomotive Purge

Third Generation Diesel Locomotive Purge

DC Electric Traction in the United Kingdom

Withdrawal of First Generation Electric Traction in The United Kingdom

Rail Preservation in The United Kingdom

Heritage Railways in The United Kingdom

The North Western Railway

Skarloey Railway

Arlesdale Railway

Romney, Hythe and Dymchurch Railway

British Rail Departmental Rolling Stock

Locomotive Experimentation in The United Kingdom

International Reactions to the British Rail Modernization Plans (1955-Present)

United Nations General Assembly Resolution 44/227

United Nations General Assembly Resolution 46/102

Locomotive Rights Censorship in The United Kingdom (1991-present)

New Build Steam Locomotives in The United Kingdom

Background

During the late 1970s and early 1980′s, significant public outcry against the use of nuclear power began. These complaints were wide-ranging, and extended to military nuclear weapons as well as civilian nuclear generating plants. Of particular concern to the British public was the safety of nuclear fuel rod flasks. These flasks, which carry spent nuclear fuel rods from power plants to the Sellafield nuclear fuel reclamation plant, are transported by train, usually through urban areas. This practice, while safe, (as of 2020, Operation Smash Hit has been the only recorded incident with a fuel rod train) raised significant concerns about the efficacy of a flask in the event of a derailment or collision. [1]

For more information:

Anti-Nuclear Movement

Anti-Nuclear Movement in The United Kingdom

First Generation Diesel Locomotive Purge

In order to turn public opinion in its favor, CEGB in 1980 organized a series of tests in which a “Magnox” flask pulled at random from the production line would be subjected to a series of impacts in order to determine its strength. [2]

Following a 4 year long series of tests in which flasks (which was filled with water to simulate the nuclear fuel) were set on fire, damaged, or dropped from increasingly higher heights onto its edge - the weakest point of the flask - the CEGB coordinated with British Rail to stage a final destructive test of the flask in a simulated train crash. The test track at BREL’s Old Dalby site was deemed suitable, and the crash was scheduled for 17 July 1984.

In order to maximize the publicity of the event, CEGB invited an estimated 1500 attendees from local media and international scientific organizations, including the BBC, The Daily Mail, The Times, Nature, and members of the nuclear regulatory organizations from the United States, Japan, France, and Canada. Observers from the IAEA were also in attendance. [2]

Rolling Stock

British Rail was in the process of reclassifying many of its first generation diesel locomotives as non-standard. This classification would allow BR to withdraw these classes of locomotive, which included the class 44, 45, and 46, colloquially known as “Peaks”. [3] [4]

For More Information:

British Rail Class 46

British Rail Mark 1

Locomotive

46 009 | 97 401 - built D199/46 062, December 1963. Known informally as “Spamcan”[3] [4], 46 062 willingly and surreptitiously exchanged numbers and identities with withdrawn sibling 46 009 in October 1983 and transferred to BR’s Research Department.[3] It is believed that neither locomotive was aware of the test or its anticipated outcome at the time of the swap.[3][4][ᴺᵒᵗᵉ¹] It is unknown whether 009/062 was transferred specifically for Operation Smash Hit, or if CEGB requested an engine and 009/062 was chosen at random. In either event, the 90MPH top speed of the class 46 and its 138 Long Ton weight was considered ideal by BREL, which wished to simulate a “worst case” scenario, in which the flask was impacted by a fully loaded high speed express train. The locomotive was purchased by CEGB for £16,750[1], and had his speed governor removed to allow a 100mph top speed.

46 023 | 97 402 was also present for the collision as a reserve engine should 009 fail. The locomotive’s services were not needed, and he remained as a source of spares until 1994, when he was purchased and expatriated to the United States by the US Peak Association, a consortium of escaped class 44, 45, and 46 locomotives in Texas. [4][5]

Rolling Stock

The rolling stock included 3 Mark 1 Coaches and a “Flatrol” depressed-center flat car. [4] Most documentation regarding the history of these vehicles was lost or destroyed following the crash. The coaches were purchased by the CEGB for £2,190[4]. It is unknown if the Flatrol wagon as purchased by the CEGB, and if so, at what cost.

Flatrol DB550019 [4]

SK E25154 - Wolverton, June 1955. Lead coach.

TSO M4514 - York, July 1956. Center Coach.

SK E25564 - Wolverton, August 1957. Trailing Coach

Crash

Preparations for the crash began on July 1-5, when 46 009 and 46 023′s speed limiters were removed to allow the train to reach 100 miles per hour at the moment of the collision. [5] Additional modifications included the removal of the locomotives’ batteries and fire extinguisher systems, and the inclusion of a remote control switch on the locomotives' exterior. The Mark 1 Coaches were unmodified. On 16 July, the Flatrol wagon was lifted from their axles and laid sideways at the end of the siding on which the accident was to take place. According to all contemporary accounts, the wagon was oriented so that their face was facing away from the observers. [6]

On 17 July, the accident train - consisting of 46 009, E25154, M4514, and E25564 - was towed to the Old Dalby test track on the rear of the CEGB charter train. The consist of this train is unknown, however it is believed that 46 023 was part of this consist in an unpowered condition. After disembarking passengers, the train continued 8.75 miles up the line to Edwalton. There, the accident train was uncoupled and made ready for the crash. [5] [6]

The crash was timed to coincide with afternoon news broadcasts, and was scheduled for 1:12 PM GMT, however the impact did not occur until 30 minutes later at 1:42, after a short delay caused by anti-nuclear protestors was further exacerbated by 46 023, who had begun screaming unbroadcastable profanities at the CEGB and BR staff, necessitating his removal so to allow the television news recording to go forward. [7]

At 1:39, the train was throttled up to full power via the external controls, and was set off down the line towards Old Dalby. The train was followed by a trio of camera helicopters and a light aircraft, while numerous ground-based cameras from BREL, CEGB, and local rail enthusiasts captured the train as it accelerated to speeds in excess of 90 miles per hour. Radar tracking of the train, as well as high speed footage taken from the test site and analysis of footage taken from stationary cameras estimates that 46 009 reached a maximum speed of 102.4 miles per hour shortly before impact. [5] [7]

At 1:42:19 PM GMT, the train rounded the final bend leading into Old Dalby. According to many accounts from non-UK-based observers, the train was audible long before it was visible, as 46 009 had at some point begun screaming for help [4] at a volume loud enough to be heard over the helicopter rotors. Some unconfirmed reports also state that Flatrol wagon DB550019 also began calling for help at this point - as they may have been previously unaware of the nature of the test. [4]

At 1:42:30, 46 009 impacted the lid of the flask. The locomotive was killed instantly as the flask destroyed his “A” side cab. The “B” side cab of 46 009 was also significantly damaged from being impacted by E25154. An explosion followed as 009′s fuel tank was crushed between the front and rear bogies, which detached from the locomotive’s frame as it buckled from contacting the flask. [4] [8] This frame buckling is believed to have thrown some amount of mechanical debris out of 46 009′s engine compartment, which would later draw conspiracy theories that the engine’s motor mounts had been loosened prior to the test in order to throw the motor free of the collision. This is false, as post-mortem photographs of 46 009′s engine room show the motor still in place. [9]

E25154 was either killed or mortally wounded in the impact as she was compressed between 46 009 and M4514 - over 30% of her superstructure was smashed inwards, while “catastrophic” frame damage was reported during scrapping. [8]

M4514 and E25564 were seriously injured in the collision - M4514 suffered severe crush damage on both ends, while E25564 was the least injured, suffering only damage to her leading end and side following the post-crash derailment. [8]

Improbably, DB550019 survived the crash. Despite being at the focal point of the collision, most of the energy of the crash was transferred into 46 009 and the Magnox flask. During the accident, DB550019 was driven over by 46 009 and began to roll on their axis. While obscured by the dust thrown up by the crash, the wagon began to cartwheel, eventually coming to rest in a vertical position, braced against E25154 and M4514. The railcar was not undamaged however, and suffered significant bowing and cracking of their steel frame. [4][8]

Immediate Aftermath

From the CEGB’s position, the test was a success - despite being impacted by 46 009 in the lid (the weakest point) - the flask maintained a proper seal, losing a minimal amount of water, which would correspond to a miniscule spillage of nuclear materials. [2]

All 5 vehicles involved in the crash were written off by the CEGB, and had already been sold to Vic Berry Ltd of Leicester for scrapping at the time of the accident, with an effective sale date of July 18. Following the accident, scrapping was meant to take place several weeks later, however international protests (see below) meant that Vic Berry work crews were unable to access the site until October, at which point 46 009, E25154, and the still living M4514, E25564, and DB550019 were cut up and recycled. [9]

International Reactions

International reactions to Operation Smash Hit were universally negative. Reactions ranged from censure at the governmental level to violence against individual members of BREL and CEGB staff.

Immediate

Numerous members of the international scientific community were present at the crash. As many would later state, they believed that the CEGB would perform the test in a manner similar to that of equivalent exercises in the United States and West Germany. [10] Those tests involved either locomotive analogues made of concrete and steel, or non-sentient locomotive shells. (Approximately 2% of locomotives built each year are non-sentient. These units are typically reserved for destructive testing.)

Concerns among the observers began before the test occurred, as members of the Canadian delegation noted that the test train was composed of sentient locomotives. They raised these concerns to BREL workers, who misunderstood their questions and assured them that no “useful” trains were to be destroyed. [10] [11]

The Canadians remained unconvinced, and their concerns grew when anti-nuclear demonstrators entered the test track. DB550019, apparently unaware of their role in test, began yelling at the protestors to leave the site, unintentionally informing many of the observers that sentient vehicles were being used in the test. [10]

As 46 009 became visible, the observers were immediately presented with the fact that not only was the test being carried out by sentient machines, but also was done without their consent, as 46 009 was visibly and audibly terrified up to the moment of impact. [4][5][10][11][12]

Following the impact, observers from the United States Nuclear Regulatory Commission immediately began a physical assault on their counterparts from the CEGB and BREL. [11] The NRC had primarily sent members of their fuel rod transport committee. This committee primarily consisted of transport industry veterans, most of whom had previously expressed strong dislikes for the inaction of the United States government towards British Rail, with some members going so far as to author a white paper in 1972 which stated that the United Kingdom could not be trusted with Trident missiles as a result of their poor sentient rights record in regard to locomotives. [13]

As the scuffle between BREL, CEGB, and NRC personnel increased, members of the Canadian and French delegations returned from inspecting the wreckage of the train. They had done so almost before the wreckage had come to a stop, and were reportedly horrified at the damage, especially the remains of 46 009. Realizing that BREL and CEGB were to blame, they joined the fight between the NRC and BREL workers. [11][12]

The fight was brought to a halt only through police intervention, and many of the BREL managers on hand for the crash were severely injured, some permanently. [11][14]

Following the brawl, CEGB officials - with significant police protection - gave a press conference in front of the wreckage before boarding their charter train to return to London along with observers from the IAEA and the Japanese Atomic Energy Commission. [14] A second incident occurred on board the train in which the CEGB delegation, including chairman Sir Walter Marshall, were attacked by unknown assailants while the train was stopped at Flitwick. [11][15] The assailants left the train after making their attack, but due to many of the international observers either being arrested or unintentionally left behind in Old Dalby, an accurate headcount had not been made before the train set off, meaning that the identity of the attackers remains unknown. Unsubstantiated reports claim that the primary attackers may have been two members of the Soviet Nuclear Agency, who had attended as part of the IAEA delegation, and were known body builders. [16] These rumors are contested by members of the CEGB, who claimed that their attackers were speaking Japanese, however these claims are disputed by the JAEC. [14][16][17]

Following the Crash

In the days after the crash, numerous governments and non-governmental organizations condemned the crash.

United States

President Ronald Reagan was publicly silent on the crash, but privately excoriated Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher in a phone call on 27 July. [18]

Vice President George H.W. Bush issued a public statement of “sympathy and support for all locomotives in the United Kingdom”. [19]

William Stanley, head of The International Brotherhood of Railway Locomotives, harshly criticized the actions of British Rail and the CEGB, and called for a boycott of all British-made products by his union’s members. [20]

The Brotherhood of Locomotive Engineers and Trainmen, speaking on behalf of the Teamsters Union, issued a “scathing” 3 page statement in which it called upon the United States government and the United Nations to formally intervene in the United Kingdom “with military action if required”. [21]

The Association of American Railways condemned the crash in “the strongest possible terms”. [22]

The Southern Pacific Railway released a statement in which they condemned the crash and pledged to redouble their funding of expatriation programs for British Locomotives. [23]

The Smithsonian Institution, whose board of directors at the time included 9 locomotives, officially ended any and all affiliation programs with museums in the United Kingdom, including The British Museum, The Science Museum, and The National Museum of Science and Industry. [24] This cutting of ties lasted until 2014, when Flying Scotsman was repatriated to the United States. [24]

Belgium

King Baudouin issued a statement of sympathy for 46 009 and the “Peak” class as a whole, and reiterated his country’s stance on offering asylum to any British Locomotive who should make it to Belgium’s shores. He also extended this offer to coaches and freight cars after learning of the fate of the other vehicles in the crash. [25]

On 31 July, Baudouin, French President Mitterand and Queen Beatrix of the Netherlands made a joint address in Brussels in which they pledged to continue their efforts to accept locomotive refugees from the United Kingdom. [26]

France

President François Mitterrand spoke at length about the crash at a press conference on 19 July. Citing initial reports from scientific observers and footage provided to Agence France-Presse, he claimed that the crash was a "travesty". On a state visit to Belgium on 31 July, he and Queen Beatrix of The Netherlands stood with King Baudouin in a joint address in which they pledged to continue their efforts to accept locomotive refugees from the United Kingdom. [26][27]

The Netherlands

Queen Beatrix gave a rare public address to the media late on 17 July, in which she expressed her shock and horror at the events of the crash. She stated that the perpetrators of the event would be brought to justice should they ever set foot on Dutch soil, and announced that 21 July would be a national day of mourning. Beatrix also sent a private correspondence to Queen Elizabeth, stating her feelings on the crash. [28] On 31 July, Beatrix, French President Mitterrand, and Belgian King Baudouin made a joint address in Brussels in which they pledged to continue their efforts to accept locomotive refugees from the United Kingdom. [26]

Canada

Prime Minister John Turner “vehemently” condemned the crash, and made a formal protest to Queen Elizabeth via Governor General Suavé. Turner also ordered the National Energy Board to cease all cooperation with the United Kingdom until those responsible at the CEGB were brought to justice. [29] This governmental boycott remained in effect until 2001, when the CEGB was fully privatized. [30]

The Canadian Labour Congress, on behalf of its locomotive members, attacked the CEGB and British Rail, and called upon trade unions in the United Kingdom to commit to industrial action in retaliation. [31]

West Germany

Chancellor Helmut Kohl, who had famously remained silent on the issue of locomotive rights in the United Kingdom, broke his silence to issue a lengthy statement in which he decried the United Kingdom and British Rail for their “monstrous acts” against locomotives. [32]

East Germany

General Secretary Erich Honecker issued a brief statement in which he decried the capitalist regime of the United Kingdom, and claimed that such an event would never be allowed to happen in East Germany. [33]

USSR

General Secretary Konstantin Chernenko offered his sympathies to 46 009′s surviving classmates and assured his citizens that events like this would never be tolerated in the Soviet Union. [34]

Japan

Minister of Foreign Affairs Shintaro Abe released a statement strongly condemning the United Kingdom for its actions. [35]

In a rare move, the Atomic Energy Commission of Japan released a separate statement that strongly condemned the CEGB, British Rail and the government of the United Kingdom, and recommended that the Japanese government bring charges against the United Kingdom in the UNCHR. [36]

Minister of Transportation Hiro Igawa released a statement expressing his “sadness and shock on behalf of all of Japan’s locomotives.” [35]

Australia

Prime Minister Bob Hawke stated that the crash was a “horrible, evil act, committed by utter bastards”. [37] He pledged to bring his concerns to Queen Elizabeth, however it is unknown whether the Monarch ever replied. [Citation Needed]

Multiple Railway Unions, including the AFULE, ATOF, and the NUR, all issued statements strongly condemning the crash, and began pushes for legislation to ban the repatriation of locomotives to the United Kingdom. [38]

United Nations

Secretary-General Javier Pérez de Cuéllar publicly and privately condemned the crash, and seriously considered requests to expel the United Kingdom from the UN Security Council after their veto of UN Resolution 44/227, which would have declared the crash a violation of international human rights law. [2][39][40]

Domestic Reactions

In the Media

As it became apparent that the international outcry was not going to go away on its own, Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher ordered a D-Notice placed on all coverage of the international outcry beginning on 18 July. [41] A further D-Notice was placed on coverage of the crash itself beginning on 21 July[42], and a historic “triple D-Notice” was placed on 29 July, after The Sun began coverage of the D-Notices themselves. [2][43][44][45]

Outside of the railroading community, reactions to the crash were muted - at the time, locomotives in the United Kingdom were viewed in much the same way as domesticated animals, and most Britons were unphased by the destruction of a locomotive. [46][47]

Following the D-Notice, the crash quickly faded into non-existence by the end of 18 July, and was quickly forgotten following the Llŷn Peninsula earthquake on 19 July.

Within British Rail

Within the railroading community, reactions were mixed. The actions of the Class 45 locomotives had caused all three “Peak” classes of locomotives to be labeled as “diesel supremacists” - a terminology used to describe locomotives who had taken exceptional pleasure in eliminating steam traction during British Rail’s modernization plan.[48] As such, many surviving steam locomotives - and newer diesels whose only interactions with the Peaks had been during their end-of-life years - viewed the crash as “just desserts”. [Citation Needed]

Many of BR’s first and second-generation diesels viewed the test in a strongly negative light, and untold amounts of financial and physical damage was done in the months and years following as locomotives refused to work or intentionally caused accidents out of protest. [48][49][50]

Domestic Protest Groups

Locomotive rights groups within the United Kingdom reacted within hours of the crash, and a sit-in protest/candlelight vigil was held outside of the gates of Old Dalby test ground from 18 July to 3 October.[51] Protestors were supported by international protestors beginning on 21 July, with significant material and financial aid given from a variety of sources, including the Austrian Red Cross[52], the Provisional Irish Republican Army[53], and American singer John Oates[54].

The influx of protestors grew the sit-in to such a size that it was impossible for crews from Vic Berry’s to access the site until October, when the entrance road was cleared by riot police using water cannons and tear gas in the early morning hours of 3 October. [55][56]

Broadcast

Initial reactions to the test were calmly negative, but were quickly turned into furious condemnations after the BBC world service broadcast the crash as part of their normal news broadcast on 17 July. [57] The nonchalant matter in which newsreader Moira Stuart delivered the piece to camera has been referenced in numerous reports and official statements as the primary source of aggression by international audiences, who had not previously realized the extent of the crash. [58] In 2006, Time Magazine listed the footage as the 13th most important piece of documentary footage in the world. [51][59]

Lawsuit

Immediately following the test, multiple expatriated Class 46,45 and 44 locomotives living in the United States sued the CEGB and British Rail in US federal court for Intentional Infliction of Emotional Distress. [60] The suit was settled out of court for an undisclosed sum. [61]

The Legacy of My Brother’s Murder

In 2017, the documentary film The Legacy of My Brother’s Murder revealed that 46 009 and 46 062 had exchanged numbers in October 1983.[3][62] 46 062, who had risen to infamy after his appearance in the Railway Series book Enterprising Engines [62], had swapped numbers in an attempt to “change his destiny” by swapping numbers, and therefore identities, with less controversial sibling 46 009, who was being transferred into departmental service. Both engines believed that this duty would allow the bearer of 46 009′s number to survive long after the class was fully withdrawn, while the bearer of 46 062′s number would be preserved due to the “Awdry Phenomenon” - a railfan preservation movement that had saved locomotives who had previously appeared in the Railway Series, including D3160[63], D261/40 061[64], and 40 125.[65]

See Also:

Murder of M/V Rainbow Warrior

The Legacy of My Brother’s Murder (Film)

Dawson’s Field Hijackings

American Association of Expatriate Locomotives

Transport of Nuclear Materials by Rail

Germanwings Flight 9525

#dark#no seriously#I'm not joking#worldbuilding#operation smash hit#ttte#background info#sentient vehicles#sentient vehicle headcanon#sentient trains#spamcan#rws spamcan#in-universe Wikipedia article#if you really stop and think about the rws universe it just gets more and more fucked up

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

For Traintober 2023, Day 31: “Lights Out”

————

While awaiting their repairs in the works, Henry reassures D7101. He doesn’t expect D7101 to repay the favor so soon.

#ttte#rws#the railway series#ttte fic#rws fic#my fic#traintober#traintober 2023#ttte henry#ttte bear#ttte d199#ttte spamcan#ttte james#ttte sir topham hatt#ttte the fat controller#ttte sir charles topham hatt ii#i hope you all enjoy!

19 notes

·

View notes

Note

Also I imagine that the nuke flask test was much less popular in universe, because the international scientific observers didn't know that there was a 'live' engine on the front of the train (plus the 3 coaches!!) and basically tried to murder the BR people afterwards. (Because if locomotives are considered people elsewhere, I'd imagine that this would make int'l observers very mad to watch someone be murdered in the name of a test/publicity stunt)

Not sure how this would play into your universe of a hoppin’ mad UN with some awareness that sentient vehicles ought to have political rights...

... but I will just throw out there that my immediate ‘take’/headcanon on the nuke flask test was:

Research Departmental engines are a special bunch. Just like elite military units, these engines are recruited due to having a particular outlook and adrenaline-chasing personality.

Therefore, even the bloody B.R. doesn’t force unwilling engines to participate. They want the ones who want to be there, doing crazy shit.

So that’s a little better.

Still, I am imagining ‘Spamcan’ (scare quotes because we know the real life engine wasn’t D199... but also in my mind the engine involved was totally Spamcan... substitute in ‘the engine’ if you prefer) volunteered at least partly thinking that his brave service would be rewarded.

Like, the flask held up, the Research Department believed all along it would hold up, Spamcan believed it would hold up. So he’s not expecting nuclear fallout! If anything, he’s expecting an ‘attaboy’ and, at minimum, to extend his Research Department career significantly.

The bit that I imagine he didn’t expect was to be cut up on site after being left alone for several days. (And that’s the part I think would generate the moral outrage. ‘Hol’ up. He definitely didn’t volunteer for that!’ ‘Well... you don’t know that he didn’t.’ ‘!!!!!’ Huh. Maybe this does start UN sanctions and an eventual war. Also, Brexit several decades early, anyone? I feel like in this alternate history Thatcher has an important role to play...)

#chatter#ttte analysis#ttte spamcan#united nations#british railways research department#... also margaret thatcher for some reason?#because my brain is the worst that's wny#wonder what happened to the coaches IRL

9 notes

·

View notes

Note

One of the more persistent questions I've had about TTTE and the RWS is - exactly what kind of world is Sodor in? Like, trains - living, sentient, thinking beings - were mass murdered, sometimes violently. (Your post about the nuclear flask tests made me think about this) Is the UK sort of like North Korea, where trains are murdered and the rest of the world watches in horror? Or is the entire world just some awful dystopia where only humans are allowed to survive?

I dunno. I think I reject the idea of the RWS/TTTE-verse being a dystopia for the vehicles… at least, when it comes to this issue.

Let’s put aside, for a moment, British Railway’s Modernization Plan… as well as British Railway’s Research Department (RIP Spamcan)… okay, let’s put aside the British Railway completely. Like, let’s look at the history of steam up until 1948.

Doesn’t seem fair to say “only humans are allowed to survive” as if there’s a wildly different standard for humans than for engines. Sadly, it's not as though we live in a utopia where we adequately support the old, disabled, and other marginalized people, either! (I speak as an American. But even in, say, U.K., life was a lot cheaper in the era of the original RWS stories, you know?) For people as well as engines, our “usefulness”—which is very subjectively evaluated—determines a good bit of our quality of life. I don’t think engines, when you average it all out, were leading a more unhappy life than people.

I think death is a part of the cycle of life for engines just as it is for people. Yes, machines can be immortal, but only if you pour massive resources of time and money into them. Realistically, the engines are also mortal. More mortal, in many ways, behind they are dependent on humans. It’s not as though the humans are preventing them from living their best lives. It’s not as though engines could band together in solidarity and autonomously arrange their own affairs, if they were just left alone. Hell, cutting an engine up is kinder than leaving them strictly alone to rust and become part of the elements over decades. Engines don’t want to be left alone! Humans find engines useful, but engines need humans.

In general, I think that (again, let’s stick, like, pre-1948) human and engine death is pretty similar. It’s seldom pretty in either case. (Medicine and health care weren’t exactly fantastic for humans either! Much higher chance for, say, British humans to die through war, violence, workplace accident, illness, or just plain hunger in this period.) It’s seldom wanted, but it comes inevitably.

And, for both kinds of beings, sometimes a full life is lived, they are old, they are tired, they are content, and they are ready for death. It’s not all that common a way to end. But it does happen. Let’s face it, death is mostly horrifying for all of us because of the ways sentient beings are treated (and mistreated, and restricted) during life.

Yeah, I know, I’m getting a bit philosophical here. But it’s a philosophical subject, death.

I’m inclined to think that engines can lose consciousness, if they are allowed to exist long enough to die naturally. But, either way, I’m still not sure scrapping is a worse fate for engines than most kinds of death are for humans. I’m not convinced blowtorches hurt, physically. I suspect that it’s more emotional—if you don’t know, or don’t want, or don’t understand what’s being done to you. But a clean cut, applied with heat? I’m just not convinced “intense heat” alone hurts, if you literally run on fire and boiling water. Also, again—if an engine can no longer be afforded, scrapping is at least a quicker and overall less painful end than abandonment to rust, so I’m not sure I see it as “murder” so much as “death with dignity.” At least this way is swift, and you are still useful even in death!

And, given that “being useful” seems so legit important in engine psyche, I can see an acceptance of scrapping as “the end”—if one is resigned to the end. (Just like people in the prime of life can’t imagine being okay with dying. But sometimes old people are. Usually the mentally healthiest old people!)

--

All this said? Just as humans accept death, but not murder (and especially not mass murder!) I think engines accept scrapping as the end… but good old British Railways DID turn the thing into a quasi-genocidal horror show that scarred everyone, even survivors.

The B.R. decided to scrap thousands upon thousands of useful engines, many with plenty of life left in them (some of the last had been in service less than 10 years!) They were withdrawing so many that they couldn’t scrap them fast enough. They would be piled up, still perfectly serviceable but left to wait for months and years on end in queues to be cut up. The B.R. had to outsource the job to scrap merchants… who then also had too many to handle, so even in those yards engines waited for years and years and years. Some can still be found waiting now, rusted and solitary and beyond all hope, six decades later!

That’s where I think the real WTF-ness comes in.

The B.R. also developed a Research Department and all the most, er… interesting… experiments that I’ve come across date from here.

RWS depicts a sort of divergence between Sodor’s railways + heritage railways vs. the “Other Railway.” As far as their machines go, the “Other Railway”’s standards of care fall. Sodor (and the heritage movement, generally) instead extend to engines the advances in rights and dignity that are being simultaneously afforded to humans.

The series has often been blasted for just “rejecting modernity.” But I think there’s a deeper critique going on here than “new-fangled nonsense.” RWS shows a real love for all technology, old and new! What it rejects—by its premise of making engines sentient—is the idea of a sort of waste culture. It promotes investing in, caring for, and loving our tech, instead of mass-production, designing new technology with deliberately short working lives, and upgrading for the sake of upgrading. (*cough* Apple *cough*)

Similarly, on a political level it supports greater autonomy and subsidiarity, by featuring engines who flourish under a sort of “small community” rule, but who are treated as disposable under nationalization. (Or “corporate takeover” events! 1948 “Other Railway” nationalization is the Big One, of course. But the books also originally draw heavily on the 1923 “Big Four Grouping” as a sort of pre-run. In real life, “standardization” also led to withdrawal and scrapping of engines, some still plenty serviceable—on a lesser but still very substantial scale. And most of RWS’s early characters are on Sodor as refugees from that event. If the N.W.R. had been absorbed by the L.M.S. in 1923, Thomas and Toby would have survived the following ten years and of the original pre-nationalization 7 engines, that’s it. Once again, the same theme emerges: death is natural and inevitable, but that doesn’t mean pushing through a ton of destruction for the sake of modernization is OK.)

That everything the books criticized the “Other Railway” for really did happen (and then some!) I think makes the RWS critique all the more scathing.

Sorry, nonny. This… has been a post. Thank you v. much for such a thought-provoking comment, though. I’d love to hear from you again if this sparks anything from you (even massive disagreement, lol).

22 notes

·

View notes