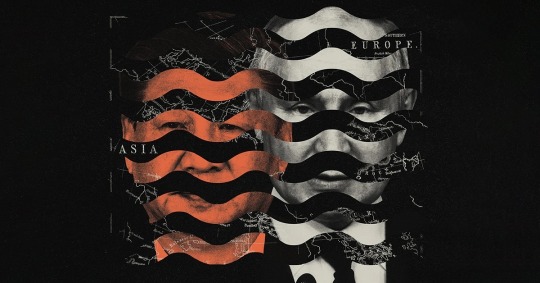

#Turkey into an autocratic state

Quote

The notion that the United States is “polarized” into two conflicting, equally stubborn and extreme camps infects much of the mainstream news coverage and everyday chatter about politics. Washington is “broken.” “Gridlock” is a problem. “No one goes out to dinner with someone on the other side.” Such mealy-mouthed language masks a stark dichotomy: Democrats have to move to the center to get bipartisan support; Republicans have become radicalized and unmovable.

This is not “polarization.” It is the authoritarian capture of much of the GOP by a right-wing movement bent on sowing chaos. Turkey, Hungary and other countries with autocratic strongmen are not polarized; democratic forces try their best to prevent their country’s ruin and collapse into total dictatorship. Our political scene, sadly, has come to resemble the global authoritarian assault on democracy.

[...]

The bipartisan border compromise ... was sunk by Republicans. Republicans in the House overwhelmingly opposed the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, commonly known as the “Bipartisan” Infrastructure Bill (which President Biden modified to get bipartisan support); almost every Republican voted against the Chips Act, they all voted against the Inflation Reduction Act, and some even voted against the Pact Act, which would have helped veterans. House Republicans have launched phony, baseless impeachment hearings. Senate Republicans filibustered reenactment of a key part of the Voting Rights Act, blocked a bipartisan Jan. 6, 2021, commission and overwhelmingly refused to convict four-times-indicted former president Donald Trump. The assertion that hyper-partisanship, chaos and nihilism (e.g., threatening to shut down the government, egging on a default and refusing to even vote on Ukraine aide) is equally divided amounts to an outright fabrication — or utter cluelessness.

The radicalization of the Republican Party is not ‘polarization’

5K notes

·

View notes

Text

by Robert Williams

To assess correctly the damage that Qatari influence in the US is causing, it is essential to understand what Qatar stands for and promotes. Qatar has for decades cultivated a close relationship with the Islamist Muslim Brotherhood, whose motto is: “‘Allah is our objective; the Prophet is our leader; the Quran is our law; Jihad is our way; dying in the way of Allah is our highest hope.” It aims to ensure that Islamic law, Sharia, governs all countries and all matters.

Hamas, an offshoot of the Muslim Brotherhood, has enjoyed Qatar as its main sponsor, to the tune of up to $360 million a year, and was until recently the home of Hamas’ leadership. In 2012, Ismail Haniyeh, head of the terrorist group’s political bureau, Mousa Abu Marzook, and Khaled Mashaal, among others, moved to Qatar for a life of luxury. This month, likely because of Israel’s announcement that it will hunt down and eliminate Hamas leaders in Qatar and Turkey, the Qatar-based Hamas officials reportedly fled to other countries.

Qatar was also home to Sheikh Yusuf al-Qaradawi, the spiritual leader of the Muslim Brotherhood, who was exiled from Egypt until his death in September 2022. According to the Meir Amit Intelligence and Terrorism Information Center:

💬 “Qaradawi is mainly known as the key figure in shaping the concept of violent jihad and the one who allowed carrying out terror attacks, including suicide bombing attacks, against Israeli citizens, the US forces in Iraq, and some of the Arab regimes. Because of that, he was banned from entering Western countries and some Arab countries…. In 1999, he was banned from entering the USA. In 2009, he was banned from entering Britain…”

Qaradawi also founded many radical Islamist organizations which are funded by Qatar. These include the International Union of Muslim Scholars, which released a statement that called the October 7 massacre perpetrated by Hamas against communities in southern Israel an “effective” and “mandatory development of legitimate resistance” and said that Muslims have a religious duty to support their brothers and sisters “throughout all of Palestine, especially in Al-Aqsa, Jerusalem, and Gaza.”

Qatar is still home to the lavishly-funded television network Al Jazeera, founded in 1996 by Qatar’s Emir, Sheikh Hamad ibn Khalifa Al Thani. Called the “mouthpiece of the Muslim Brotherhood,” Al Jazeera began the violent “Arab Spring,” which “brought the return of autocratic rulers.”

In 2017, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Bahrain, and Egypt made 13 demands of Qatar: “to cut off relations with Iran, shutter Al Jazeera, and stop granting Qatari citizenship to other countries’ exiled oppositionists.” They subsequently cut ties with Qatar over its failure to agree to any of the demands, including ending its support for terrorism, the Muslim Brotherhood, and Al Jazeera.

The Saudi state-run news agency SPA said at the time:

💬 “[Qatar] embraces multiple terrorist and sectarian groups aimed at disturbing stability in the region, including the Muslim Brotherhood, ISIS [Islamic State] and al-Qaeda, and promotes the message and schemes of these groups through their media constantly,”

US universities and colleges are happy to see this kind of influence on their campuses in exchange for billions of dollars in Qatari donations. According to ISGAP:

💬 “[F]oreign donations from Qatar, especially, have had a substantial impact on fomenting growing levels of antisemitic discourse and campus politics at US universities, as well as growing support for anti-democratic values within these institutions of higher education.”

#qatar#american universities#ivy league#ivy league schools#foreign influence#muslim brotherhood#yusef qaradawi

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

National broadcast and cable networks are barely covering Trump’s recent gaffes and incoherent statements

Trump: “Viktor Orban... he's the leader of Turkey.”

Fact: Viktor Orban is Hungary's authoritarian leader.

Yet Trump’s gaffe received less than three minutes of total coverage across all three major cable news networks.

National broadcast and cable networks are failing to cover a series of verbal gaffes and incoherent statements recently made by disgraced former President Donald Trump, the front-runner to win the Republican nomination again in 2024.

As Media Matters has already extensively documented, media outlets have repeatedly obsessed over President Joe Biden's age since he announced his campaign for reelection. The same attention has not been given to his likely challenger, former President Donald Trump, even though the two men are nearly the same age. In fact, in just the last two months, Trump has made a number of nonsensical statements: He has mixed up the authoritarian leaders of Hungary and Turkey; confused his former Republican opponent Jeb Bush and Jeb’s brother, the former president George W. Bush; mixed up a number of his Democratic opponents with former President Barack Obama; and made a garbled statement accusing President Joe Biden of leading the country into “World War II.”

On Monday, a New York Times article finally brought some much-needed attention to the dichotomy between Trump’s own attacks on Biden, compared to Trump’s actual behavior:

But as the 2024 race for the White House heats up, Mr. Trump’s increased verbal blunders threaten to undermine one of Republicans’ most potent avenues of attack, and the entire point of his onstage pantomime: the argument that Mr. Biden is too old to be president. Mr. Biden, a grandfather of seven, is 80. Mr. Trump, who has 10 grandchildren, is 77.

An analysis by Media Matters found that TV broadcast news has given no coverage to these false and incoherent statements from Trump, and cable news has barely covered them. Overall, MSNBC has covered the four recent Trump gaffes the most, still just 35 minutes, and the majority of this coverage has come from just one program, Morning Joe. CNN has covered the gaffes a mere 9 minutes. Fox News, meanwhile, mentioned the gaffes just twice for less than a minute total in the periods studied.

Mixing up Hungarian, Turkish strongmen

Trump commented on October 23 during a campaign speech in New Hampshire: “You know, I was very honored — there’s a man, Viktor Orbán. Did anyone ever hear of him? He’s probably, like, one of the strongest leaders anywhere in the world. He’s the leader of Turkey.”

Orbán is the authoritarian prime minister of Hungary; autocrat Recep Tayyip Erdoğan is president of Turkey. This remark also could have brought renewed attention to Trump’s long-established affection for dictators.

Media Matters reviewed transcripts from October 23 thorough 29 and found that the comment received less than 2 minutes of TV news coverage, mostly spread across MSNBC’s The Rachel Maddow Show and Deadline: White House, plus a single comment on Fox News’ The Five lasting 6 seconds. Broadcast news didn’t cover it at all.

Warning that Biden might start “World War II”

During a September 15 speech at a right-wing event in Washington, D.C., Trump claimed that Biden was “cognitively impaired” and “in no condition to lead,” while warning that his leadership could imperil the United States in “dealing with Russia and possible nuclear war.” Trump then added: “Just think of it. We would be in World War II very quickly if we’re going to be relying on this man.”

World War II happened 80 years ago, a detail Trump missed while he was calling Biden “cognitively impaired.” During the same speech, Trump also seemed confused about whom he is running against in 2024, and whom he ran against in 2016.

(continue reading)

#politics#donald trump#viktor orban#journalism fail#media bias#i s2g msm wants trump to have a 2nd term

23 notes

·

View notes

Note

Why is it impossible that fascism as a system can be used for good?

One enlightened leader who can do what needs to be good for the people - environmental protection, jobs and dismantling countries’ interdependence on globalism and the assets of corporations stripped and handed to the state for the benefit of the collective?

One wise leader who can end corruption and none of the squabbling scraps of progress..

Democracy isn’t worth fighting for.

An interesting question you pose here. So first off, let us point out that some of what you’re proposing isn’t about fascism per se but rather about authoritarian dictatorships in general. You’re making a claim that a “benevolent dictator” might be the best system of governance. There have been a few historical figures described as “benevolent dictators” - leaders who wielded autocratic power to (arguably) benefit their people. Think Atatürk in Turkey; Tito in Yugoslavia; and Yew in Singapore as three examples.

None of those, however, were fascists. Atatürk, in fact, expanded voting rights in Turkey and Tito led some of the most effective anti-fascist partisan forces that resisted Nazi occupation in WW2.

Aside from those three examples there aren’t many others to point to, but there are a LOT more authoritarian dictators that very plainly did not use their power to improve conditions for the people. Dictators are far more likely to brutally suppress their own people to the benefit of themselves and their cronies. Also: in what world does it make sense for any people to give up their autonomy and control over their own lives and turn all powers over to a single person? What person in the world is so “enlightened” that they have the capacity to make reasoned and wise decisions about literally all aspects of society? Seems to be the stuff of fantasy if we’re being honest.

But you don’t want just any run-of-the-mill authoritarian dictatorship, Anon. You’re advocating for a fascist dictatorship. So let’s examine some of the issues you’ve pegged as best being resolved by a fascist dictatorship:

-Environmental Protection: we’re unaware of any fascist regime in the past that’s made progress on that front and the countries currently heading into fascism (Brazil, Russia, the United States) have been taking massive strides backwards in the direction of environmental degradation at the behest of their quasi-fascist leaders (Bolsonaro, Putin, Trump & his Supreme Court appointees). Could a fascist leader instead be a champion for the environment? Possibly. But it’s more likely that such a leader would use the environment as an excuse to invade other countries to secure environmental resources “for their people.” Hitler called this lebensraum.

-Jobs: historically, fascists have created jobs by starting wars. Wars are always good for job creation - at least at first. But perhaps that’s not the most desirable way to create employment.

-Dismantling Countries’ Interdependence on Globalism: We don’t think you’ve thought this through or really understand what “globalism” means. We think you think globalism = international economic/geopolitical/military interconnections between nations, which is called “globalization.” But the term “globalism” originates from the Nazis’ anti-semitic propaganda, which portrayed Jews as “globalists” who were naturally disloyal to the nations they lived in and part of an evil conspiracy to control the world.

So, assuming you mean “globalization,” we need to point out some a priori assumptions you’re making that:

a) nation states are natural and desirable ways for societies to be structured;

b) cooperation or reliance between nation states is the thing that is undesirable, and;

c) the best way to cease international cooperation/interdependence is via a fascist dictatorship.

We see more evidence to argue that nation states are bad; that international cooperation & integration is good; and that there are a multitude of other ways to stop globalization other than fascists taking power than what you’re trying to postulate, so good luck putting your argument together.

(We would also remind you, Anon, that the fascists of WW2 were in a “globalist” alliance called the Axis.)

-Stripping Corporations of Assets Which Are Then Handed to the State to Benefit the Collective: That, Anon, is called a communist or socialist revolution, not a fascist revolution. In fascist takeovers (at least in every fascist takeover we’ve seen so far), corporations work alongside the fascists, helping them to secure power precisely in order to prevent communists/socialists from gaining power and stripping corporations of their resources. What happens after a fascist takeover is that the economy is transformed into what’s called “crony capitalism” - where corporations continue to thrive and even make real gains through things like access to slave labour & seized resources from whatever ethnic group the fascists have been scapegoating.

In The Anatomy of Fascism, historian Robert O. Paxton notes that “even at its most radical, however, fascists’ anticapitalist rhetoric was selective. While they denounced speculative international finance (along with all other forms of internationalism, cosmopolitanism, or globalization - capitalist as well as socialist), they respected the property of national producers, who were to form the social base of the reinvigorated nation…Once in power, fascist regimes confiscated property only from political opponents, foreigners, or Jews…none altered the social hierarchy, except to catapult a few adventurers into high places.”(pg. 10-11)

So if you’re in favour of seizing the means of production for nationalization & turning them over to the people, best put down Mein Kampf and pick up a copy of Das Kapital!

-One Wise Leader Who Can End Corruption: Many have tried; all have failed, Anon. We can’t think of any examples of One Great Man single-handedly rooting out corruption in governance but we can think of many, many examples of One Corrupt Man (or One Man Corrupted By Power) that increased corruption or merely turned it to the advantage of himself & his inner circle. This study found that the longer a dictator is in power, the greater the extent of corruption in the country, not the reverse.

This seems to happen in any kind of dictatorship, but fascist dictatorships are particularly vulnerable to corruption because of the cult of personality that is endemic in fascism, which produces a leader unaccountable to anyone who will also use violence without any hesitation to eliminate any opponents. Fascist regimes reinforce existing hierarchies and corrupt systems because they rely on key players high up in the existing hierarchy to help them rise to power, rewarding those who help them with assets seized from the outgroups they demonize. It was no accident that Donald Trump replaced key senior diplomats with his completely inexperienced and unqualified daughter and son-in-law, for example.

Finally Anon, your assertion that fascism > democracy underlies your willingness to surrender what little power you have presently to a charismatic leader who would operate with zero accountability and no real incentive to rule to anyone's benefit but their own. We’re going to suggest that you would be much unhappier in that situation and that your real dissatisfaction with the present “democratic” system is that it isn’t very democratic at all. What we think would be preferable is not less freedom and more violence but rather more opportunities to increase your autonomy by participating directly in the decisions that affect your life - whether you’d call that direct democracy, democratic confederalism, anarchism, or something else. You’re right that getting to choose between a minute handful of viable leaders/parties every four years who are in lockstep agreement on 90% of things anyway doesn’t feel like democracy at all. There are certainly better alternatives to how we are ruled now. Fascism is certainly not one of those alternatives.

243 notes

·

View notes

Text

As NATO prepares to celebrate its 75th anniversary next year, the bloc’s original architects would have been stunned by its broad membership and growing agenda today. In helping design the new alliance for the purpose of containing the Soviet Union in Europe after World War II, the U.S. diplomat George Kennan argued that NATO should take its name literally and include only North Atlantic countries—excluding Mediterranean states such as Greece, Italy, and Turkey. His rationale was that only countries on the Atlantic seaboard could be effectively supplied by ship in the event of war with the Soviets, whereas including others would remove all limits to the bloc’s commitments and be unworkable. To ensure that Article 5 of its founding treaty—the collective defense clause—was ironclad, NATO kept a laser-sharp focus on military preparedness for much of its history.

Today, NATO has 31 members (though when Sweden joins, it will be 32) and more than 30 partner countries across the world. Its agenda has expanded to issues beyond territorial defense, such as cybersecurity and counterterrorism. Last year, the bloc established the Defense Innovation Accelerator for the North Atlantic, a 1-billion-euro (about $1.1-billion) fund for emerging and disruptive technologies.

Yet as the toolbox of statecraft has expanded in response to security challenges, NATO has retained a narrow focus on military objectives. And even in this area, it has been constrained in delivering on its goals. Defense ministers, for example, can make commitments at NATO meetings, but finance ministers may not find the required resources at home. For European countries, dual membership in NATO and the European Union has diffused responsibility and led to significant underinvestment in military preparedness. Too many European leaders still hope that Washington or Brussels will take care of it.

With the return of war to Europe and the Middle East, as well as great-power competition to the world, NATO’s vision and scope need to be broader. The alliance faces not only Russian aggression, but also the challenge from China and other autocratic, revisionist actors seeking to upend the global order. Security today involves a comprehensive toolbox, including economic sanctions and industrial policy, and needs to bring the relevant actors into the fold.

Consider the current state of play. Last month, 31 foreign ministers met at NATO headquarters in Brussels to discuss a range of security issues, from Russia’s war against Ukraine to the long-term challenge of China. Yet the only major decision achieved at the two-day gathering was a brief three-paragraph statement on Ukraine that echoed previously agreed-on language. The Israel-Hamas war and its effects across the Middle East, which was top of mind for many of the participants, was barely addressed at all, even though many European NATO members will be directly affected.

The allies’ ambition should therefore be to make NATO the premier forum not only for trans-Atlantic military cooperation, but also for better coordination among the world’s democracies. Europe and the United States should leverage NATO to buttress international order alongside their Indo-Pacific partners. To that end, the institution should globalize its agenda and find ways to work more closely with its partners outside the Euro-Atlantic region.

Currently, too many issues that are central to the security of NATO allies are dispersed across multiple forums, contact groups, and bilateral channels. NATO is charged with collective security for Europe and North America. The EU also has a mutual defense clause for its members and has moved forward on defense cooperation and funding. Both blocs have intensified their security outreach to countries in the Indo-Pacific. That, in turn, overlaps with the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue—comprising Australia, India, Japan, and the United States—as well as the Australia-United Kingdom-United States pact. Also involved is the G-7, which has evolved from a talking shop to a forum where the leading democracies deliberate on economic sanctions and technology policy. The U.S.-EU Trade and Technology Council has a similar remit—but neither it nor the G-7 can make binding decisions. All this overlap produces confusion and lack of focus, restricting the ability of NATO members to develop an effective strategy, let alone make efficient decisions in times of conflict.

To remove these political detours and bureaucratic obstacles, it would make sense for many of these discussions and decisions to take place in a single forum—or at least, for the various strings to come together in one place. And that would be NATO, which has the strongest record on addressing collective security. Issues to be integrated with military defense would include economic sanctions, export controls, industrial policy, technology policy, foreign investment screening, outbound investment controls, secure supply chains, and trade measures.

For a start, there should not just be regular meetings of NATO defense and foreign ministers. Ministers responsible for finance, trade, commerce, and technology should convene within NATO as well. All these areas are vital for national security.

In addition to globalizing its agenda, NATO should also expand the participants in these discussions to include Indo-Pacific partners, such as Australia, Japan, New Zealand, and South Korea. Leaders of these four countries attended NATO’s annual summits in 2022 and 2023, but instead of cooperating on an ad hoc basis, it would be better to establish standing open invitations to NATO summits and ministerial meetings.

The bloc could also establish a council of NATO members and Indo-Pacific states—akin to the NATO-Ukraine Council—where those partners could convene meetings and be on equal footing with the NATO allies. Over time, additional partners could also be invited.

These changes require a shift in mindset within NATO. The bloc is rightly regarded by many as the most successful military alliance in history, but it could also be the most effective international institution for foreign-policy coordination and implementation. However, its primary focus on the Article 5 collective defense guarantee has developed into inherent institutional caution and constraint.

Yet not all security challenges trigger Article 5—and even then, the defense clause does not set off an automatic response. Article 5 states only that if armed attack occurs against a NATO member, each ally commits to assist the attacked country with “such action as it deems necessary.”

On the one hand, NATO’s focus on Article 5 has made the alliance an undisputed success, with every square inch of territory backed by the full weight of the alliance, which includes potential nuclear retaliation. In all of NATO’s long history, the bloc invoked Article 5 only once: after the 9/11 terrorist attacks on the United States. On the other hand, the emphasis on Article 5 has also constrained the bloc’s potential for more nimble political action.

NATO would benefit from greater strategic flexibility to address security policy issues. A useful historical analogy is the shift in U.S. foreign policy during the Cold War, when Washington moved from the doctrine of massive retaliation to so-called flexible response. In the 1950s, the Eisenhower administration defined its deterrence and containment policy in terms of overwhelming response to any encroachment by the Soviet Union or the communist bloc. But this outsized commitment made foreign policy too rigid and limited: After all, not every nail around the world required a nuclear hammer. Thus, the Kennedy administration devised a more agile approach, including military and nonmilitary options for a particular crisis in proportion to the specific situation.

NATO already has the institutional mechanism for a broader approach to security. Article 4, for example, provides for political consultations whenever a member considers its “territorial integrity, political independence or security” threatened. This is both a broader remit and a lower threshold, allowing security threats short of a military attack to be addressed. It would be the institutional basis for the alliance to incorporate key tools of security policy, such as economic sanctions and export controls.

NATO also has a basis for addressing issues such as industrial and technology policy as means to develop defense and security capabilities. Under Article 3, allies have committed to “maintain and develop their individual and collective capacity to resist armed attack” through “self-help and mutual aid.” NATO should facilitate better coordination on defense investment and ensure that the allies maintain a long-term technological competitive edge over their adversaries.

A broader and more global NATO would help overcome the hobbled, overly complex decision-making processes among the Euro-Atlantic allies and their partners in the Indo-Pacific. That said, there should be no illusion that an institutional setup alone can escape the primacy of politics.

Organizations such as NATO are what their members make of them. Blaming them for failure or inaction is like blaming Madison Square Garden when the New York Knicks play badly, as the late U.S. diplomat Richard Holbrooke once quipped.

But a simplified and better-designed institutional setup would go a long way in facilitating sounder, more efficient decision-making during unavoidably turbulent times.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lemkin Institute Statement on Azerbaijan's breach of the established ceasefire agreement and its unprovoked attack on Armenia

The Lemkin Institute strongly condemns Azerbaijan's ongoing war of aggression against Armenia and its people. Despite the ceasefire agreements, Azerbaijan's overall genocidal rhetoric by its state authorities demonstrates an enduring determination to eliminate the Armenian national identity and its territory.

[...] Azerbaijan’s recent provocations date back to the Nagorno-Karabakh war for independence from Azerbaijan in the 1990s. Since then, the Azeri government has been known to attempt to spark renewed fighting with Armenia, notably by moving troops into ceasefire territory and unlawfully bombing Armenian soil, as in the recent provocation. This new aggression, which broke out overnight on September 13th, illustrates how volatile and strained the situation remains.

[...] The presidents of Azerbaijan and Turkey have threatened to erase Armenia from the world’s map on multiple occasions. The Republic of Armenia has estimated that it has lost 135 soldiers in this recent attack. Azerbaijan has also taken new prisoners of war which add to the ones illegally detained by Azerbaijan since the 2020 war. There are also indications that Azerbaijan deliberately targeted the civilian population in the above-mentioned cities.

[...] Once again, we urge the international community to explicitly condemn this attack on the Republic of Armenia and to take measures against the autocratic government of Azerbaijan and its ally Turkey.

International bodies and states cannot continue to ignore Azerbaijan's aggressive behavior towards the Republic of Armenia. If its actions remain ignored and unpunished as they have been so far, the world will soon witness an escalation of the violence and another genocide against the Armenians.

#when even the genocide prevention institute says it's the second genocide in the making and people still try to 'both side' this#armenia#read the full statement please and reblog#the worst thing is to stay silent#q#article

73 notes

·

View notes

Text

I had a discussion with a friend of mine in the (US) military recently and it reminded me that most people in the US and, in fact, in the world, are almost entirely unaware that there is a new Cold War taking shape. I think more people should be aware of it, knowledge is power after all, and knowing about something gives you the opportunity to help shape it, particularly if you're a citizen of a country where your voice has an impact in government. I hope this LONG RANT (TM) helps someone better understand.

INTRODUCTION

As I said, there's a new Cold War beginning, and, like the previous Cold War, there's a strong component of ideology to it. Specifically, the world is beginning to fracture between liberal democracy and autocracy.

What makes this conflict particularly complex is that we're at the early stages. When thinking about the Cold War, capitalism vs communism, it wasn't until the 1950s, 1960s, or even the 1970s in some cases that it was really clear which side most consequential nations would end up on. It was pretty obvious that the Soviet Union and the United States would be the major communist and capitalist powers, respectively, but the status of many other nations didn't become clear until long internal political debates and outside interventions had a chance to play out.

So, without further ado, let's get into it.

WHY IS THERE A CONFLICT AT ALL?

This is one of the key questions and, honestly, it all comes down to the interconnectedness of the modern world. You see, modern autocracies that don't rely on the divine right of kings to justify their rule generally justify it by results. In order to make sure the results come out correctly, they control the information available to their people to ensure that their people are told that the autocratic rulers are giving them the best results, whether that's in terms of economics, culture, religion, or whatever else they want to focus on.

As my old boss used to tell me a decade and a half ago, "North Korea can't afford to allow YouTube to get to the average person even if the average person just watches stupid videos because it's going to become really obvious that, yes, this person is an idiot, but that idiot has a fridge, a TV, a car, and has obviously never missed a meal in their life; they can't possibly be poorer than us."

In the olden days that would be fairly easy. Radio signals only travel so far, so as long as you control the TV and radio stations and limit the ability of printed media to spread too widely, you could completely control what information your population receives.

Nowadays, however? Well, that's very different. The internet allows people from all over the world to talk to each other in an instant and it can even go a long way to easing language barriers. The advent of satellite internet means that even efforts to control internet traffic such as the so-called "Great Firewall of China" will be increasingly limited in their effectiveness.

Today, in order for an autocracy to control the information their people receive, they not only have to control the information environment in their own country, they have to control the information available in other countries as well. That's the reason you're seeing things like the Saudi Arabia's murder of dissident Jamal Khashoggi, Russia's poisoning of Alexander Litvinenko and Sergei and Yulia Skripal, a Chinese attempt to kidnap dissidents in the US, India's alleged killing of Hardeep Singh Nijjar, and it's attempt to kill Gurpatwant Singh Pannun.

All of these were killings or other physical violence that took place in liberal democratic countries (except for Khashoggi who, though American, was lured to the Saudi embassy in Turkey where was killed) where what the individuals were doing was perfectly legal. This is the driver of conflict today, authoritarian nations attempting to maintain their monopoly on the information their citizens receive in a global information environment.

THE EARLY DAYS

We're currently in the early days of this autocracy vs liberal democracy competition and there are numerous nations currently in conflict over which side they're going to be on including, unfortunately, our own. In order to explain that, I need to get a bit technical over the difference between "democracy" and "liberal democracy".

Democracy, basically, can describe any situation where leaders are elected by some kind of popular vote. If you look closely at that for a second, you'll realize that it's such a broad category that even the autocratic Soviet Union technically qualified. Obviously, a category broad enough to include actual autocracies isn't really in opposition to them.

Liberal Democracy, on the other hand, is a Democracy, but with a whole bunch of other things as well. In general, a Liberal Democracy will feature multiple distinct candidates and/or parties in their elections, some sort of separation of powers between branches of government, the rule of law (law that applies equally to all), an open society (one in which individuals make choices rather than being controlled by tribes or other type of collectivism), a market economy with private property, universal suffrage, and the protection of human rights, civil rights, civil liberties, and political freedoms for all people.

(That definition borrowed almost entirely from the Wikipedia article on Liberal Democracy, check it out if you're interested.)

In other words, Liberal Democracy is more than just "do people vote for leaders?", but encompasses just about everything we'd associate with individual rights and liberties and the structure of institutions to ensure them. People in an Illiberal Democracy may technically vote for their leaders but, without all of these other rights and protections, they can hardly be said to have truly chosen them. And, when you define it clearly, you can see that there's a bit of a disagreement about that in American politics right now.

The Republican Party, and particularly its MAGA wing, is increasingly of the mind that not everyone's vote is legitimate and has been putting in place barriers to voting that disproportionately affect disfavored groups. In addition, they're pushing to end much of the separation of powers, putting more unchecked power in the hands of the president at the expense of checks, balances, and sometimes guarantees of individual liberty. Democracy would continue, but Liberal Democracy would end.

To be clear, this isn't just an American problem, but one that is faced by nearly every Liberal Democracy today. As part of autocrat's efforts to control information outside of their own borders, they've been attempting to influence politics within Liberal Democracies and promote internal autocratic movements; usually right-wing nationalists. From the Republican Party's MAGA wing to France's National Front to Germany's Alternativ Fur Deutschland, just about every Liberal Democracy in the world now has a fundamentally autocratic right-wing party that is doing much better than it did just ten or twenty years ago and, if you scratch the surface, you will find support for them, both financial and otherwise, from autocrats around the world.

Of course, it's not just the far-right either, autocrats have been promoting the far-left in Liberal Democratic countries as well. While the far-right has had much more electoral success and is much more politically organized in the west and, thus, has received more attention, we can't ignore the fact that autocracy is largely neutral on the political scale and operates anywhere that conspiratorial thinking can take hold and distract people from the removal of their freedoms or even convince them that those freedoms hold no value in the first place.

WHERE WE GO FROM HERE

Well, that's the trillion dollar question, isn't it?

Conflict will likely continue between autocratic and liberal democratic states, but the complexities are growing. Much like communism vs capitalism, autocracy vs liberal democracy is more of a spectrum than a hard binary and many states are actively sloshing around along that spectrum.

There's also the uncertainty of how different countries react to incidents like the ones we're seeing. Technically, killing a person on the soil of another country is an act of war, but not many people in the modern world are willing to go to war for the killing of one person. Most likely what we'll see is a gradual hardening of blocs as liberal democracies react to provocations by slowly pulling back from cooperation and connection with autocratic nations.

We're also likely to see countries switch sides. Unlike the rapid shift in allegiances that we saw during the Cold War, however, these are likely to be more gradual shifts like what we've seen in Hungary and Turkey where individual rights are stripped away gradually and a governing autocrat is slowly ensconced in power rather than a hard and fast coup. We could, of course, see countries go the other way as well, as in the case of Ukraine which has slowly strengthened individual rights and overthrown its autocrats.

All of this, the solidification of blocs and the shifting of countries within this spectrum, is going to create the opening situations for this particular conflict. Whether it becomes a conflict of more rigidly defined blocs or even sparks proxy wars remains to be seen.

CONCLUSION (TL;DR)

The days of a fairly open world, both in physical travel, the movement of goods, and in communication, is starting to come to an end as that openness begins to threaten the hold of autocrats on power. Those autocrats are attempting to keep both the openness and power by working to control the information available in countries that practice Liberal Democracy and generally guarantee individual liberties.

Over the next several decades, it is likely that we will see increasing separation between a bloc of autocratic nations and a bloc of liberal democracies, much as the Cold War saw separation between pro-capitalist and pro-communist countries. Some of that separation will likely not go smoothly and we will likely see at least some military tension and possibly even armed conflict as leaders react to changes or even try to distract from them with military force.

Just as importantly, we are likely to see tension within countries all over the world as autocratic political parties attempt to take control of liberal democracies and pro-democracy movements attempt to overthrow autocrats.

I'll admit this isn't the most hopeful vision of the future that we'd like to see, but I think it's fairly realistic given the current realities we see. I hope that this gives you some insight into what's going on and allows you to plan accordingly.

As always, let me know if you think I missed something or got something wrong, I'm always up for adjusting my thoughts, and I hope you enjoyed the read.

#politics#international politics#liberal democracy#democracy#individual rights#autocracy#cold war#new cold war#long rant (tm)

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

2024 / 13

Aperçu of the Week:

"Peace is never made with weapons, but by stretching out our hands and opening our hearts."

(Pope Francis at this year's Easter blessing "Urbi et Orbi" in Rome)

Bad News of the Week:

Turkey has voted. "Only" local elections, but an important test of sentiment in view of the severe economic problems facing the country of two continents, such as inflation of almost 70%. The winner was not the conservative AKP (Adalet ve Kalkınma Partisi / Justice and Development Party) of ruling President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, but the largest opposition party CHP (Cumhuriyet Halk Partisi / Republican People's Party), a social democratic party founded by none other than the father of the country, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk.

The CHP now holds the office of mayor in the country's five largest cities, including Ankara and Istanbul. The latter in particular will hurt Erdogan, as he himself was once mayor of the metropolis on the Bosporus. A 75% voter turnout proves that the voice of the people has indeed spoken here. This is remarkable in that Erdogan has become more and more of an autocrat in recent years - among other things by restricting freedom of expression and the press, curtailing the independent judiciary, persecuting critics of the regime and transforming the state into a presidential republic.

The election result is therefore much more than just a yellow card to those currently in power, a "midterm effect" so to speak. It is a clearly articulated, unmistakable rejection of an authoritarian style of leadership in general and of wannabe despot Erdogan in particular. This rejection is all the more pleasing as the opposite direction has become increasingly established worldwide in recent years, especially in patriarchal societies. Freedom, pluralism, peace, equality and democracy are finding it increasingly difficult to be seen as fundamental foundations of nation building.

Many states such as Libya, Iraq and Yemen have been unable to emerge from the maelstrom of a failed state for years and decades. And beacons of hope such as Tunisia, which adopted a constitution following the Arab Spring revolution and held the status of the only democratic country in the Arab world from 2014 to 2020, have reverted to autocracies. Others, such as Myanmar, which tried to establish democratic elements from 2011 to 2021, are now even under the rule of military dictatorships. Which makes this actually good news into bad news after all.

Good News of the Week:

I have never understood many things that happen in Israel. For example, why the ultra-Orthodox - 13% of the population - enjoy so many exceptions in a theoretically secular state, such as not being called up for compulsory military service. Or why a people that has suffered so much from radicalism in its history is increasingly voting for far-right parties. Or why anyone who criticizes Israeli policy is immediately and reflexively vilified as an anti-Semite.

Israel could always be sure of one thing, no matter what it was about: the support of the USA. Although the protection of Israel is the official reason of state in Germany, it is primarily the Americans who see themselves as the unwavering protector of the Israeli state. Automatically and unfortunately often without reflection. For example, in all previous military conflicts in the Middle East, in which Israel has violated international law on more than one occasion, or in the oppression of the Palestinian people, which can safely be described as apartheid, the US veto has always ensured that Israel has not been subject to a UN Security Council resolution. Until now.

An abstention by the USA was the first time that a (theoretically legally binding) UN resolution called for a ceasefire, serious peace efforts and protection of the civilian population in Gaza - 14 votes for, 1 abstention, 0 votes against. Side note: historically, most UN resolutions were not prevented by the Soviet Union/Russia or China, but by the USA. And Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu reacted like an offended child. Among other things, by canceling the US visit of an Israeli delegation. Which was actually on a mission to ask for more weapons. In soccer, this is called an own goal. The media response was corresponding - even in Israel, whose enlightened population continues to take to the streets in their tens of thousands against the wannabe despot.

You can take whatever view you like on the proportionality of Israel's military response to the Hamas attack. But this behavior proves once again that Netanyahu is not a sovereign politician who serves the interests of his people without thinking of himself. He is a selfish, consultation-resistant, undemocratic power politician who pushes an autocratic agenda regardless of the consequences. In this respect, any behavior that reveals this character is fine with me. Because that makes his re-election less likely. Which would be good for peace in the Middle East. And for the world. Which makes this actually bad news into good news after all.

Personal happy moment of the week:

We rarely treat ourselves with dining out. And there's a work colleague whose company I really appreciate, but rarely see, as he works from the north of Germany. Last week, he was a guest in our little town, of all places, for a three-day training course. And as this is a very beautiful area, he brought the whole family with him. And we met them with our whole family in a long-established inn to spend an evening feasting and exchanging anecdotes. Lovely.

I couldn't care less...

...that once again - and once again completely unnecessarily - summertime has begun. The basic idea dates back to 1784, when Benjamin Franklin (of all people) saw it as a way of saving energy by using less electric lighting. Its complete uselessness has long been proven, and the impact on wildlife is enormous. Which in this case includes me.

It's fine with me...

...that "crypto king" Sam Bankman-Fried was sentenced to 25 years in prison for fraud in the collapse of his cryptocurrency stock exchange FTX. First, because he commited fraud. Secondly, because I reject all forms of speculation and (trading) derivatives in principle. Maybe I'm old-fashioned, but the real economy is probably called that because it's real.

As I write this...

...I listen to the typically melancholy piano music of Frederik Chopin. It goes perfectly with the cold and wet April weather, which started right on time today.

Post Scriptum

Hardly anyone outside Germany has ever heard of the Fraunhofer-Gesellschaft (Fraunhofer Society for the Advancement of Applied Research) from Munich. It is named after Joseph von Fraunhofer, a leading inventor in the field of optics, e.g. telescope construction - hence the inscription on his tombstone "Approximavit Sidera" (He brought us closer to the stars). The purpose of the association is applied research for the direct benefit and advantage of society. In other words, less theoretical basic research than concrete usability.

The results of the 30,000 or so people working there are certainly noticeable in everyday life: The MP3 audio format, white LEDs, High Definition Television (HDTV), airbags or RFID technology are just examples of the inventions we are all familiar with. The institution comes up with over 600 inventions every year. These are not - as is the case with an industrial patent - exclusively available to one manufacturer, but to everyone. The Fraunhofer-Gesellschaft is now celebrating its 75th anniversary. Congratulations. And thank you.

#thoughts#aperçu#good news#bad news#news of the week#happy moments#politics#pope francis#turkey#recep tayyip erdogan#akparti#chp#istanbul#israel#benjamin netanyahu#usa#un security council#resolutions#dining out#summertime#benjamin franklin#sam bankman fried#frederic chopin#april#Fraunhofer#democracy#nation building#freedom#middle east#gaza

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

BBC: Jordan's free speech boundaries tested with satire

By Yolande Knell, BBC News Middle East correspondent, 5 August 2023

One of the most popular satirical websites in the Arab world has hit back after being banned in Jordan by poking fun at the country's new planned censorship laws.

AlHudood, meaning "the limits" or "the borders", publishes articles and social media posts highlighting the absurdities of Middle Eastern politics and everyday life in a deadpan style. It is in effect the region's answer to the US parody website The Onion or the UK's Private Eye.

Its mocking commentary of the lavish wedding of Jordan's crown prince apparently led to AlHudood being blocked by the authorities last month - just ahead of tighter restrictions on the media being introduced.

Legislation currently going through parliament has been denounced by journalists and human rights groups, who say it will further restrict freedom of expression.

In its response, AlHudood - which was started in Jordan a decade ago - has offered a sardonic guide to publishing content in the country "without being fined, imprisoned, crucified".

Another mock article in a series of reports focuses on a "terrorist" who just started to pose a question on Facebook and was arrested for an "electronic crime".

"I think this will probably create a bigger clash [with officials in Amman] than before, but we feel we have no choice because if we don't do this, the longer-term effect for us and everyone else is going to be so much worse," an AlHudood source tells me from London.

In a region of autocratic leaders where state-run media dominates, AlHudood has thrived against the odds over the past decade and is seen as a breath of fresh air by many of its young followers. It says it reaches a million readers on its website and some 30 million a year on social media, which has become the main forum for voicing criticism of Arab authorities.

"We sort of do the journalism and then repackage it with satire," the London source says. "Satire is really great at working with hypocrisy and corruption."

Dark humour is deployed even on the toughest topics such as civil war, sectarian fighting, immigration and terrorism.

"A lot of the news is so overwhelming and it's difficult to find an angle on it," the AlHudood source adds. "Our approach at least gets people curious about what's happening. It helps create a question in people's heads like: 'What should I think about that?'"

Among the online publication's recent satirical reports was one about the Tunisian president condemning sub-Saharan Africans for stealing places on migrant boats from his own people.

Others drily introduce the two latest candidates "who will not end" Lebanon's long-running presidential vacuum and tell of an agreement between Turkey and Syria "to repatriate 50% of every refugee".

One headline: "Saudi government signs Hajj promotion deal with Cristiano Ronaldo" mocks how widely the superstar footballer has been used in marketing since his lucrative transfer to a Riyadh club.

For AlHudood's writers the opulent celebrations for the Jordanian royal wedding in June seemed ripe for ridicule. While Jordanian law has long criminalised speech deemed critical of the king, from experience its team did not think it was crossing red lines.

A satirical Instagram post depicted Jordanian riot police arresting a man for throwing a party for his baby son on the day of the crown prince's nuptials. There was also a joke threatening fines for citizens who were found not smiling sufficiently. Another gag asked how the costs of the wedding were being covered in the country struggling with rising living costs.

Human rights activists say that in Jordan and the broader Middle East, there has been a recent trend for increased state censorship. There have been many prosecutions of social media influencers and bans on TikTok.

A coalition of civic rights groups led by US-based Human Rights Watch (HRW) has urged Jordan's parliament to scrap its new cybercrimes law, saying it could jeopardise free speech and lead to greater online censorship. They criticise how some offences are described in vague terms which could leave them open for the interpretation of prosecutors.

"It makes very clear that the intention of this is to scare people and make them think twice about posting anything online that could be remotely critical or controversial, or something some official won't like. It's deeply concerning," says Adam Coogle from HRW in Amman.

"When you pair it with the real shrinking space for civil discussion that has taken place in this country otherwise in the last few years, we're looking at a clear slide into more authoritarian governance."

The cybercrime bill - which has just been sent back to Jordan's lower house of parliament by the Senate after it drafted small revisions - is also expected to give greater powers to the authorities to block websites and social media platforms.

Jordan's government maintains that the draft law is not meant to limit freedoms but tackle fake news, online defamation and hate speech. It denies trying to stifle dissent but says it wants to protect people from internet abuse or blackmail.

Nevertheless, there has been criticism from Washington, the country's main donor.

In order to work around regional restrictions, AlHudood has now been formally based in the UK for several years. It does not name its contributors from across the Arab world, reducing the chance of direct conflict with officials.

Despite the Jordan ban - which follows on from one in the United Arab Emirates - its writers say that they will continue touching the sensitive nerves of Middle Eastern powers.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

....it's very unfortunate that Israel is a model for world governments, and you can see its influence in places like Hungary, Russia, the Brexit UK, the United States, or any other country that has descended into mafia state autocracy, often directly in conjunction with Netanyahu, who's largely been in control of Israel since 2009, with occasional departures.

But also, with the backing of a lot of the same donors and plutocrats and supporters. And Israel has, in this time, become a far-right autocratic state. It was always an apartheid state. It was never a true democracy. You cannot be a true democracy when you are colonizing and abusing a population that is living in subjugation, right beside you – which has historically been the case with Palestinians. But even for Israelis themselves, it has become an autocratic state with protests suppressed, with journalists, as you mentioned, threatened. And also, major outlets, like Haaretz, that have done a lot of brave investigative reporting. They are being threatened and the situation is dire. And I think that Israel should be listed when people put together lists of authoritarian states. It should be there. People will mention Russia, China, Turkey, and others, but they'll neglect to list Israel because Americans have always been taught that Israel is the lone democracy in the Middle East. And that is simply not the case.

Authoritarianism, Dehumanization, and the Fight Ahead

"It's so important that folks stick together and recognize each other's struggles as a unified struggle," says author Sarah Kendzior.

Kelly Hayes

Dec 5, 2023

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Feast Days: St. Bartholomew

Saint Bartholomew, workshop of Simone Martini (c.1317-1319)

Happy St. Bartholomew's Day!

Today marks the feast day of St. Bartholomew the Apostle -- that's right, one of the OG followers of Jesus! Although he has a pretty miniscule role in Biblical narratives, he is one of the twelve apostles, and so has a heavy load when it comes to patronage. He is the patron saint of butchers, Florentine salt and cheese merchants, house painters, book binders, leather workers, neurological diseases, skin diseases, dermatology, shoemakers, glove makers, farmers, curriers, tanners, trappers, and twitching.

A fair warning: this one isnt' so cheerful. Bart's demise, like many of the saints, is pretty gnarly, and it does have something to do with all this skin/leather stuff going on in his patronage. This day is also associated with an infamous example of religious violence, Catholic vs. Protestant. Read on at your own peril.

His Life

Not a lot is known about Bartholomew's life within Biblical canon. He is believed to be same person as the apostle Nathaniel, who appears in John 1:45-51 and 21:2. He is also mentioned in the Book of Acts.

Much of the tradition around Bartholomew details his trips to spread Christianity. This man sure got around! Two ancient texts cite a trip to India, specifically the Bombay region, where he left a copy of the Gospel of Matthew. However, many scholars doubt that this actually happened, and say that he actually went to Ethiopia or modern-day Yemen. Still other traditions hold that he was a missionary in Mesopotamia, northeastern Iran, and/or central Turkey.

Arguably his most eventful missions trip was to the Armenia/Azerbaijan area in the 1st century CE. Along with his fellow apostle Jude (also called Thaddeus), he is credited with bringing Christianity to the region; and as such, both are venerated as the patron saints of the Apostolic Church of Armenia. His luck ran out here, however, and he was martyred in the region in horrific fashion. Legend holds that he converted the king of Albania, Polymius, to Christianity. Polymius's brother was not a fan of this, and fearing a Roman backlash, and ordered Bartholomew's torture and execution. There are three main stories about his manner of death. The most popular says that he was executed in Albonopolis in Armenia by being flayed (skinned) alive and beheaded. The second account says he was crucified upside-down, and the third that he was beaten unconscious and thrown into the sea to drown. The first legend captures the imagination much more vividly, and as such Bartholomew is most frequently depicted holding his skin -- sometimes he has grown a new skin, other times he is still a skin-less meat man. Many times the old skin still has his face. Woof.

Bartholomew has also come to be associated with the field of medicine, for two main reasons. Firstly, artists past and present have taken advantage of Bartholomew's flayed state to execute detailed anatomical studies of the human body. Secondly, a portion of his relics are stored at the basilica of San Bartolomeo all'Isola in Rome. This was the old site of a temple to Asclepius, which was an important Roman medical site (Asclepius is the Greek god of medicine). Thus, over time, Bartholomew and medicine came to be connected.

The St. Bartholomew's Day Massacre

A depiction by Huguenot painter François Dubois, who was possibly an eyewitness (c.1572-1584)

This series mainly focuses on saints' days in the UK, but one does not simply discuss St. Bartholomew's Day without discussing the massacre. This outbreak of bloodletting was part of the decades-long French Wars of Religion, which was fought on and off between Catholics and Huguenots (French Calvinist Protestants). As religion held such an essential role in society and in the machinations of power, the 'type' of Christianity embraced by the state was literally and frequently a matter of life and death. With autocratic governments, unity of church and state, and much less effective means of communication and law enforcement, it was only too easy for hate and violence to take over, and for those in power to turn a blind eye or even participate. There are many contemporary examples we can look to as parallels to this event, and I think with the same conditions, it could happen a lot more often.

The massacre took place in Paris on the night of August 23rd-24th, 1572. Although the causes for the riots are complex and deep-rooted, the main inciting factor was the marriage of Henry III of Navarre, a Catholic, to Margaret of Valois, a Huguenot. They were married on August 18th, and many rich and famous Huguenots gathered in largely-Catholic Paris to attend the wedding. Tensions erupted in scenes of horrific violence, with Catholic mobs attacking, trapping, and hunting down Huguenots in the streets. The violence lasted for several weeks, spreading out through the provinces and other urban areas. Sir Francis Walsingham, Elizabeth I's ambassador to France at the time, was in Paris during the violence and barely managed to escape with his life. Modern estimates cite the casualties from anywhere between 5,000 and 30,000 people. Although the Catholic reaction to the slaughter ranged from outward glee to sickened horror, Protestant countries obviously panicked, and the massacre was used as anti-Catholic propaganda for centuries, 'justifying' Protestant reprisals against uninvolved Catholics. It was yet another terrible event in the brutal European Wars of Religion.

St. Bartholomew's Day and its Traditions

On to more cheerful things!

This day is also called Bartlemas or Bartelmytide.

Emma, the wife of King Canute, supposedly brought one of Bartholomew's arms to England in the 11th century, and it was venerated in Canterbury Cathedral for many years. Most of the information on this is in the past tense, so I assume it is no longer there.

Depiction of Bartholomew Fair, Rowlandson et. al., c.1808

August and the time around St. Bartholomew's Day is the traditional time for markets and fairs. One of the most famous was Bartholomew Fair in West Smithfield, London. A massive spectacle, it served as a place for serious trade, becoming the main cloth trading event in the country; but it also offered entertainment like dances, tournaments, musicians, international curiosities, food vendors, conjurers, wild animals, circus acts, and an all-around good time. It began in 1133 by a charter from Henry I, and originally lasted three days, but during the 1600s it could go for two full weeks! With the change in the calendar in 1753, the fair was moved to September 3rd, and in 1791 they decided four days was quite enough time. It was ended in 1855 for causing public disturbance and the criminal activity it attracted. A less rowdy street fair is still held in Crewkerne, Somerset, at the beginning of September. It dates back to Saxon times and is even recorded in the Doomesday Book of 1086!

There is also some delightful weather wisdom about St. Bartholomew's Day. One rhyme says, "If St. Bartholomew's be fair and clear / Then a prosperous autumn comes that year". Another is connected to St. Swithin's Day (July 15th), and claims "All the tears St. Swithin can cry / St Bartelmy's mantle wipes them dry". Traditional wisdom holds that rain on St. Swithin's Day means rain for the next 40 days, or until August 24th.

Many areas have their own unique ways of celebrating the holiday, such as blessing mead or baking special bread. It's nice to know that a holiday associated with such terrible things can be made into a nice occasion!

If You're Still Interested

There are a few famous depictions of the saint, including Michelangelo's rendering in "The Last Judgement". However, the whole flayed skin thing makes it pretty gruesome, and I didn't want to spring that on y'all without warning. If you'd like to see it, feel free to Google!

History Today's article that details some specific exhibitions from Bartholomew's Fair, including ventriloquists and a pig that could tell time!

Sources

Please forgive the excess of Wikipedia! It's hard to find info on the internet about this holiday, and Wikipedia has been the most forthcoming. It really can be helpful sometimes.

Wikipedia (Bartholomew the Apostle)

Wikipedia (Bartholomew Fair)

Wikipedia (St. Bartholomew's Day Massacre)

My AP European History class (woot)

aclerkofoxford

The Country Diary of an Edwardian Lady by Edith Holden

The Encyclopedia of Saints by Rosemary Ellen Guiley

#feast day series#st bartholomew#history#english history#british history#folk history#cultural history#feast day#saints day

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

As Turkey approaches presidential and parliamentary elections on May 14, President Recep Tayyip Erdogan is fighting an uphill battle for survival. He is behind in the polls, which can be attributed to three main reasons.

First, Erdogan can no longer rely on his autocratic bargain predicated on delivering economic growth and upward mobility in return for political support or quiescence. This served him well during most of his 20 years in power but now is irreparably broken.

His stubborn and uninformed monetary policy has left the economy fragile and suffering from high inflation. A major erosion of purchasing power generating growing poverty and income disparity ensued in the last couple of years. But the bad news for Erdogan does not end with the economy.

Second, and perhaps most important, a traditionally weak and divided opposition is now united against him. An eclectic coalition of six parties, boosted with the support of a kingmaker Kurdish political movement, stands firmly behind Kemal Kilicdaroglu, the leader of the social-democratic Republican People’s Party and the candidate of what is known as the Nation Alliance.

Kilicdaroglu is ahead of Erdogan in the polls, but his margin is slim.

Finally, a third factor also works against Erdogan: the massive earthquake that shook Turkey on February 6 and killed more than 50,000 people. The disaster blatantly exposed the inefficiency and institutional decay under Erdogan’s one-man rule.

To the massive frustration of millions affected, the state was quasi-absent in the immediate aftermath of the disaster. Under the corrupt management of incompetent cronies, governmental agencies not only failed in search and rescue efforts but also mismanaged post-disaster relief.

Under normal circumstances these factors should translate into a major defeat for the ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP). Yet elections are no longer free and fair in Erdogan’s Turkey. The government controls most of the media and the judicial system.

In the absence of a strong margin of victory for the opposition, Erdogan may refuse to concede and take the result to the courts or worse – to the streets.

Lacking charisma and oratory skills but with a strong reputation for integrity, Kilicdaroglu, 74, is the architect of the opposition’s newly acquired unity. But he has a losing streak against Erdogan.

In a two-round presidential election system that is bound to be tightly contested, whether Kilicdaroglu can win in the first round with more than 50% of the vote will end up depending on an unknown: the resurgent candidacy of Muharrem Ince, who has emerged as a populist disrupter, to the delight of Erdogan. Ince, who polls between 5% and 7%, attracts younger voters unhappy with both the AKP and the opposition.

Given the stakes, the whole country is on edge. A large part of the population is ready for change. But the same societal segment is anxious and incredulous about the prospect of Erdogan losing power.

Aura of invincibility

Like many observers in the West who lack confidence in Turkey’s democratic maturity, many in Turkey find it hard to believe that Erdogan will quietly disappear after losing an election. This brings us to a critically important yet often misunderstood dimension of the drama about to unfold in Turkey: Erdogan’s biggest advantage is his aura of political invincibility.

There seems to be a fatalistic resignation that Erdogan will find a way to stay in power and that a peaceful transition will prove elusive. The same alarmism sees this election as the last chance before Turkey slides into dictatorship.

Such apprehension may serve to galvanize the opposition. But it is misplaced and ignores reality. Erdogan is not as strong as he seems and Turkey is not an autocracy like Russia or China where polls are cosmetic.

Despite the illiberal nature of strongman rule, elections will continue to matter if Turkish people are not intimidated by Erdogan. Even if he manages to win, the people and the opposition should remain vigilant, make sure the result is not manipulated before conceding, and prepare for the next fight instead of losing hope and faith in elections.

Turkish democracy will outlast Erdogan even if he scores a pyrrhic short-term victory. He is bound to lose even if he wins.

Finally, let’s not forget that Erdogan lost local elections in all major cities in 2019 when the opposition was united and received Kurdish support. In Istanbul, a 16-million-strong megapolis and a microcosm of Turkey, Erdogan refused the result after a very narrow loss and bullied his way to a rerun.

He lost in a landslide.

And all this was before the economic meltdown and the hyperinflation of the last two years. Behind the facade of his massive presidential palace, Erdogan is a lonely man, detached from reality, and surrounded by sycophants.

Yes, he has gained a well-deserved reputation as a Machiavellian survivor after 20 years in power. But centralization of decision-making, personalization of authority, and the hollowing out of state institutions have not made him stronger.

Instead, Turkey’s strongman is now at his weakest. If Erdogan wins on May 14, it will not be because of his capacity to govern or his populist policies raising the minimum wage or lowering the retirement age. It will be because too many Turks still believe he is invincible.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Why Political Strongmen?...Why Now?

It’s hard to look around, read an article or watch the news and not be struck by what is going on politically in the United States and in many countries around the world today. So much of what is disturbing to me has to do with so-called “strongman” regimes, autocrats who were once elected and have since consolidated their power by weakening the institutions that might have once held them in check. As I’ve watched this process unfold, a number of questions come to mind. One is, “Why is this happening? The second is, “Why is it happening now? From an historical perspective it would be helpful to know when and under what conditions this has occurred before. As a therapist, I would like to better understand the psychological underpinnings of this global trend and examine the ways that fear and the search for safety may contribute to a rise in authoritarianism.

If this were just an American phenomenon we could examine Donald Trump’s continued popularity and front-runner status in the Republican Party and try to analyze the currents in our society that have contributed to his rise to prominence and power. But Vladmir Putin has also consolidated dictatorial power with early popular support along with Xi Jinping in China, Victor Orban in Hungary, Recep Erdogan in Turkey and Narendra Modi, in India. The people of Brazil, defying that trend, voted out Jair Bolsinaro, a Trump clone, and voted in a left-leaning progressive and former president, Lula DeSilva. But recent elections in Italy, Argentina and even Holland have empowered illiberal parties and right wing leaders, each of them fiercely nationalistic, conservative regarding women’s and LGBTQ rights, favoring one dominant religion and hostile toward immigration and those who are ethnically different from the majority population. When the political right makes gains over the years even in traditionally liberal bastions such as Israel, England, Germany, France and Scandinavia, it raises questions for me about what is going on in the “global mind.”

Even as I refer to “the political right,” I realize that it cannot be reduced to one monolithic world-wide movement. In the United States during the Reagan era, Republican Party constituents were mainly social conservatives, anti-communists (later “War on Terror” hawks) and free marketeers. What is different today is that many former conservatives seem ready to use the state to advance a radical agenda and are willing to concentrate enormous power in a strongman like Donald Trump.

But why? Why are people who not that long ago sanctified individual freedom, were in favor of “small government” and supported a muscular foreign policy designed to challenge international violators of human rights now lining up behind a “strongman?” Why is the Republican Party unwilling to fully support a war of liberation against a dictatorial Putin and instead deify a demagogue who has professed an admiration for dictators, made it clear that if elected again he would use the levers of government to reduce press freedom and other forms of dissent and openly stated that he would use “his” Justice Department to exact revenge on those who refuse to do his bidding? Why have there been similar shifts in ideology and popular sentiment in other countries?

If the proposition that fear and the manipulation of people’s fears play a role in “strongmen” coming to power, then destabilizing global trends may also be important to consider in trying to understand why this is occurring now. During the past twenty five years and more the world has experienced greater than ever displacement of people from the global south to the global north. Much of this mass migration is happening as a result of the climate crisis along with political and economic instability in countries in Africa, Latin America and in Syria. The September 11th attacks on the United States along with Jihadi terrorism in Europe, India and in majority Muslim countries has been the backdrop for right wing political parties to rail against the new immigrants while millions of desperate refugees try to find safe havens in Europe and the United States. This is not to say that the political Left has never used fear to manipulate public opinion or tried to impose its thinking on others through control. It is more that the contemporary move toward more autocratic, strongman regimes at this time is comprised of almost exclusively nationalistic and even Neo-fascist rhetoric.

The broad, destabilizing trends that I have been describing along with the ways that the news about them is being disseminated may be impacting our core psychology. The twenty four hour news cycle can magnify and intensify whatever is going on in what Marshall McLuhan has called our “global village,” and the dissemination of mis-information and inflammatory rhetoric on social media has served as an organizing platform and recruitment tool for violence in ways that were not possible before. In short, it may be our easy access to information that is contributing to our fears and to varying degrees, making us feel unsafe. I also propose that this is occurring in ways that did not happen as much when what was once packaged as “the news” came to us in a few major newspapers and on three or four T.V channels with news “anchors” who, for better and for worse, we came to know and trust.

I not only believe that a proliferation of information and mis-information can make us feel less safe, it also lays bare how vulnerable our nervous systems are to signals that indicate danger. Although most of us like to think of ourselves as the masters of our fates - and in some ways I believe we are - our search for safety may be the underlying factor governing many of our choices. The “fight or flight” response is now commonly understood to be part of our hard wiring, but recent studies having to do with the autonomic nervous system and more specifically the vagal nerve have increased our understanding of just how tied we are to underlying responses that are part of our biology: The Following quotes are from “Our Polyvagal World” by Steven Porges, a long time researcher on how our nervous system processes and produces feelings of safety and fear:

“ …the search for safety can be viewed as the primary organizing principle behind human evolution and human society. The need for safety is so central to our survival that virtually everything we are drawn to or enjoy is, in some way, a reflection of this need.”

We have to remember that this is still a theory, but the more I learn about our automatic and often subliminal reactions to what we experience as either threatening or safe, the more I can understand how easily we can be manipulated by political actors with malevolent intent. This theory also poses the following idea:

“the more threatened our nervous system feels, the more primitive the response. As we get more defensive and fearful, the higher thinking that is unique to humans is bypassed in favor of reactionary gut instincts.”

So how might this theory at least partially explain the rise of autocracy in the world today?

“For an authoritarian or would-be strongman, convincing a large number of people that they are under threat is basically required to maintain power. We see this when political actors don’t just civilly disagree with their opponents or with entire groups of people but cast them as outsiders and subhuman bogeymen. If your constituents are made to fear that somebody or some group is an existential threat to their way of life or might replace them then these constituents may let you get away with nearly anything. It becomes “us versus them.” It is through this playbook that tyranny, extreme nationalism and political violence thrive.”

If this scenario is beginning to sound familiar it is probably because it has both historical implications and present day manifestations. When a politician like Donald Trump takes the stage, feelings of danger, anger and outrage are what he evokes in his base. The feared others - “Mexican rapists," and immigrants from "shit-hole countries," are merely props designed to unsettle the nervous systems of his followers which he can then refocus as hatred toward the “enemies” whom “only he can protect you from.”

Each would-be “strongman” has his own list of enemies, usually disempowered groups or “outsiders” whom he characterizes as victimizers and as a threat to the nation.