#Van Nest Polglase

Link

The Best of the Astaire-Rogers movies. Cinematography: David Abel. Production Design: Carroll Clark/Van Nest Polglase. Songs: Irving Berlin.

#fred astaire#ginger rogers#eric blore#erik rhodes#edward everett horton#mark sandrich#van nest polglase#carroll clark#hermes pan#irving berlin

0 notes

Photo

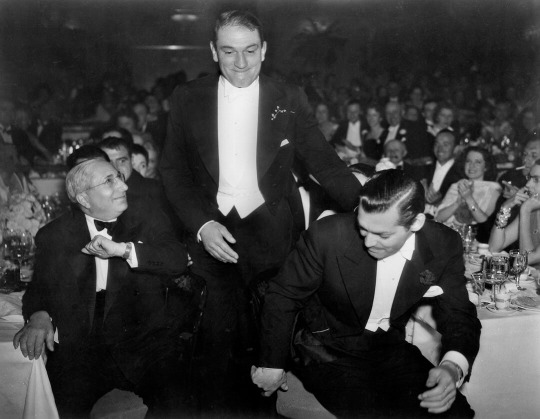

Sam Jeffe and Cary Grant in Gunga Din (George Stevens, 1939)

Cast: Cary Grant, Victor McLaglen, Douglas Fairbanks Jr., Sam Jaffe, Eduardo Ciannelli, Joan Fontaine, Montagu Love, Robert Coote, Abner Biberman, Lumsden Hare. Screenplay: Joel Sayre, Fred Guiol, Ben Hecht, MacArthur, based on a poem by Rudyard Kipling. Cinematography: Joseph H. August. Art direction: Van Nest Polglase. Film editing: Henry Berman, John Lockert. Music: Alfred Newman.

Gunga Din is imperialist and racist, and its title character is an example of the Magical Negro trope, the person of color who saves the white folks' asses. It's embarrassing to see actors like Sam Jaffe (in the title role), Eduardo Ciannelli, and Abner Biberman in brownface. So we have to swallow a lot that's objectionable to still enjoy Gunga Din. We typically evade the issue of a film's content and message by emphasizing style and technique, and Gunga Din is loaded with style and technique, from the comic performances of Cary Grant, Victor McLaglen, and Douglas Fairbanks Jr. to the crisp cinematography of Joseph H. August, convincingly turning the Sierra Nevada into the Khyber Pass. The movie was originally supposed to be directed by Howard Hawks, when Ben Hecht and Charles MacArthur developed a story out of Rudyard Kipling's poem. They did it by plagiarizing their own play The Front Page, which hinges on a man (in this case two men) trying to prevent his friend and co-worker from going off and getting married. Hawks might have made a better movie: He would almost certainly have given Joan Fontaine more to do in her role as the woman who is trying to take Fairbanks away from Grant and McLaglen. But he was fired from the film and replaced with George Stevens. Still Hawks got his chance to work with Hecht and MacArthur's original story when he made the best of all screen versions of The Front Page as His Girl Friday in 1940. The real star of Gunga Din (as well as His Girl Friday) is Grant, playing at peak clown and loving it, while still pulling off the dashing hero. It's interesting to compare Grant's performance in this movie with the one he gave for Hawks in Only Angels Have Wings, which was released the same year, in which Grant is more serious as the troubled boss of a group of pilots flying the mail across the Andes.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

“LITTLE WOMEN” (1933) Review

"LITTLE WOMEN" (1933) Review

There have been many adaptations of Louisa May Alcott's 1868-69 best-selling two-volume novel, "Little Women". And I mean many adaptations - on stage and in movies and television. I have personally seen three television adaptations and four movie adaptations. One of the most famous versions of Alcott's novel is the 1933 movie adaptation, produced by Merian C. Cooper and directed by George Cukor.

Although I have seen at four adaptations more than once, I had just watched this version for the very first time. Judging from the reviews and articles I have read, Cukor's "LITTLE WOMEN" seemed to be the benchmark that all other versions are based upon. So, you could imagine my anticipation about this film before watching it. How did I feel about "LITTLE WOMEN"? That would require a complicated answer.

"LITTLE WOMEN" told the story of the four March sisters of Concord, Massachusetts - Margaret (Meg), Josephine (Jo), Elizabeth (Beth) and Amy - during and after the U.S. Civil War. Since second daughter Jo is the main character, the story focuses on her relationships with her three other sisters, her parents (especially her mother "Marmee"), the sisters' Aunt March, and the family's next-door neighbors, Mr. James Laurence and his grandson Theodore ("Laurie"). Although each sister experiences some kind of coming-of-age throughout the story, the movie focuses on Jo's development through her relationship with Laurie and a German immigrant she meets in New York City after the war, the charming and older Professor Friedrich Bhaer. Jo and her sisters deal with the anxiety of their father's involvement in the Civil War, genteel poverty, scarlet fever, wanted and unwanted romance, and Jo's fear of dealing the family breaking apart as she and her sisters grow older.

I must saw that the production values for "LITTLE WOMEN" were certainly top-notch. One has to credit producer Merian C. Cooper in gathering a team of excellent artists to re-create 1860s Massachusetts and New York for the movie. I was especially impressed by Van Nest Polglase's art direction, Sydney Moore and Ray Moyer's set decorations and art direction team of Hobe Erwin, George Peckham, and Charles Sayers. However, I simply have to single out Walter Plunkett's excellent costume designs for the film. I doubt very much that Plunkett's costumes were an accurate depiction of 1860s fashion, I believe he came close enough. Plunkett's career also included work for 1939's "GONE WITH THE WIND", "RAINTREE COUNTY", from 1957 and the 1949 version of "Little Women". I suspect that this film marked his debut for designing costumes for the mid-19th century. I did have a problem with the hairstyles worn by three of the four leads. A good deal of early 1930s hairstyles seemed to have been used - with the exception of the short bob. At least three of the actresses wore bangs . . . a lot. Bangs were not popular with 19th century women until the late 1870s and the 1880s.

Until the release of the 2019 film, George Cukor's adaptation of Alcott's novel has been considered the best by many film critics. Do I agree with this assessment? Well, I cannot deny that I had enjoyed watching "LITTLE WOMEN". One, producer David Selznick and director George Cukor did an excellent job in their selection of the cast - especially the four actresses who portrayed the March sisters. All four had excellent chemistry. The movie's portrayal of the U.S. Civil War and the years that followed it immediately struck me as pretty solid. And although there were moments when the film threatened to border on saccharine, I must admit that Cukor and the screenplay written by Victor Heerman and Sarah Y. Mason kept both the narrative and the film's pacing very lively. And finally, I enjoyed how the movie depicted Jo's friendship and romance with Professor Friedrich Bhaer. I found it warm, charming, romantic and more importantly . . . not rushed.

However, I do have a few issues with "LITTLE WOMEN". There were times when the movie, especially during its first half hour, seemed in danger of wallowing in saccharine. I get it. Alcott had portrayed the Marches as a warm and close-knit family. But Alcott had included minor conflicts and personality flaws in the family's portrait as well. It seemed as if director George Cukor, along with screenwriters Sarah Y. Mason and Victor Heerman were determined to whitewash this aspect of Alcott's novel as much as possible. This whitewashing led to the erasure of one novel's best sequences - namely Amy March's burning of Jo's manuscript in retaliation for an imagined slight, Amy's conflict with her schoolteacher, the development of Amy and Laurie's relationship in Europe, and Meg's conflict Aunt March over her relationship with tutor John Brooke. These deletions took a lot out of Alcott's story. It amazes me to this day that so many film critics have willingly overlooked this. Do not get me wrong. "LITTLE WOMEN" remained an entertaining film. But in erasing these aspects of Alcott's story, Cukor and the two screenwriters came dangerously close to sucking some of the life out of this film. Ironically, Mason and Heerman repeated their mistake in MGM's 1949 adaption with the same results.

Most critics and movie fans tend to praise Katherine Hepburn's portrayal of Jo March to the sky. In fact, many critics and film historians to this day have claimed Hepburn proved to be the best Jo out of all the actresses who have portrayed the character. Do I agree? No. Although I admired Hepburn's performance in the movie's second half, I found her portrayal of the adolescent Jo in the first half to be a mixed bag. There were times when I admired her spirited performance. There were other times when said performance came off as a bit too strident for my tastes. I honestly do not know what to say about Frances Dee's performance as Meg March. My problem is that I did not find her portrayal that memorable. I barely remember Dee's performance, if I must be honest. I cannot say the same about Joan Benett's portrayal of the youngest March sibling, Amy. Mind you, Bennett never received the chance to touch upon Amy's less pleasant side of her nature. And it is a pity that the screenplay failed to give Bennett the opportunity to portray Amy's growing maturity in the film's second half. But I have to admit that as a woman who was roughly three years younger than Hepburn, she gave a more subtle performance as a pre-teen and adolescent Amy, than Hepburn did as the teenaged Jo. The one performance that really impressed me came from Jean Parker's portrayal of Beth March, the family's shyest member. I thought Parker did an excellent job of conveying Beth's warmth, fear of being in public and the long, slow death the character had suffered following a deadly bout of scarlet fever.

I can honestly say that Mrs. "Marmee" March would never be considered as one of my favorite Spring Byington roles. Mind you, the actress gave a competent performance as the March family's matriarch. However, there were times when she seemed too noble, good or too ideal for me to regard her as a human being. As is the case in most, if not all versions of "LITTLE WOMEN", the Mr. March character barely seemed alive . . . especially after he returned home from the war. I cannot blame actor Samuel S. Hinds, who portrayed. I blame the screenwriters for their failure to do the character any justice. On the other hand, I did enjoy Henry Stephenson's portrayal of the complicated, yet likeable Mr. Laurence. I enjoyed how Stephenson managed to slowly, but surely reveal the warm human being behind the aloof facade. Edna May Oliver gave a very lively performance as the irascible, yet wealthy Aunt March. In fact, I would go as far to say that her performance had breathed a great deal of fresh air into the production. Not many critics were impressed by Douglass Montgomery's portrayal of the March sisters' closes friend, Theodore "Laurie" Laurence. I can honestly say that I do not share their opinion. Frankly, I felt more than impressed by his portrayal of the cheeky, yet emotional Laurie. I thought he gave one of the film's better performances - especially in one scene Laurie reacted to Jo's rejection of his marriage proposal. I thought Montgomery did an excellent job of reacting emotionally to Jo's rejection, without going over the top. I also enjoyed Paul Lukas' interpretation of Professor Bhaer. There were moments when his performance threatened to get a little hammy. But the actor managed to reign in his excesses - probably more so than Hepburn. And he gave a warm and charming performance as the romantic Professor Bhaer.

Yes, I have some issues with this adaptation of "LITTLE WOMEN". If I must be honest, most of my issues are similar to my issues with the 1949 adaptation. This should not be surprising, since both movies were written by the same screenwriters - Sarah Y. Mason and Victor Heerman. However . . . like the 1949 movie, this "LITTLE WOMEN" adaptation proved to be a solid and entertaining adaptation of Louisa May Alcott's novel. One can thank Mason and Heerman, director George Cukor and the fine cast led by the talented Katherine Hepburn.

l

#little women#little women 1933#louisa may alcott#George Cukor#merian c. cooper#jo march#meg march#amy march#beth march#katherine hepburn#frances dee#joan bennett#jean parker#spring byington#douglass montgomery#paul lukas#henry stephenson#edna may oliver#walter plunkett#victor heerman#sarah y. mason#john davis lodge#samuel s. hinds#u.s. civil war#gilded age#old hollywood#period drama#period dramas#costume drama

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

STRANGER ON THE THIRD FLOOR (1940) – Episode 142 – Decades Of Horror: The Classic Era

“The only person who ever was kind to me was a woman. She’s dead now.” Wait. What? Join this episode’s Grue-Crew – Chad Hunt, Daphne Monary-Ernsdorff, Jeff Mohr, and guest host Dirk Rogers – as they witness the brilliance of Peter Lorre highlighted by the dark stylings of cinematographer Nicholas Musuraca in Stranger on the Third Floor (1940).

Decades of Horror: The Classic Era

Episode 142 – Stranger on the Third Floor (1940)

Join the Crew on the Gruesome Magazine YouTube channel!

Subscribe today! And click the alert to get notified of new content!

https://youtube.com/gruesomemagazine

ANNOUNCEMENT

Decades of Horror The Classic Era is partnering with THE CLASSIC SCI-FI MOVIE CHANNEL, THE CLASSIC HORROR MOVIE CHANNEL, and WICKED HORROR TV CHANNEL

Which all now include video episodes of The Classic Era!

Available on Roku, AppleTV, Amazon FireTV, AndroidTV, Online Website.

Across All OTT platforms, as well as mobile, tablet, and desktop.

https://classicscifichannel.com/; https://classichorrorchannel.com/; https://wickedhorrortv.com/

An aspiring reporter is the key witness at the murder trial of a young man accused of cutting a café owner’s throat and is soon accused of a similar crime himself.

Director: Boris Ingster

Writers: Frank Partos (story & screenplay by); Nathanael West (uncredited)

Music by: Roy Webb

Cinematography by: Nicholas Musuraca

Art Direction by: Van Nest Polglase

Wardrobe: Renié

Special Effects by: Vernon L. Walker (special effects)

Selected Cast:

Peter Lorre as The Stranger

John McGuire as Mike Ward

Margaret Tallichet as Jane

Charles Waldron as District Attorney

Elisha Cook Jr. as Joe Briggs

Charles Halton as Albert Meng

Ethel Griffies as Mrs. Kane, Michael’s landlady

Cliff Clark as Martin

Oscar O’Shea as The Judge

Alec Craig as Briggs’ Defense Attorney

Otto Hoffman as Police Surgeon

Emory Parnell as Grilling Detective in Dream Sequence (uncredited)

Herb Vigran as Reporter Who Wins Cardgame (uncredited)

Bobby Barber as Giuseppe (uncredited)

Stranger on the Third Floor inhabits the creepier side of, shall we say horror-adjacent, film noir. In fact, some experts argue that it is the first example of that dark genre, later to be labeled film noir. It’s a nightmare-influenced murder mystery featuring Peter Lorre chewing on all the scenery he can. Boris Ingster directs Stranger on the Third Floor with all the style that feels as if it could have been an early Val Lewton production. Yup, it’s Hollywood expressionism, RKO-style. This film is worth the watch, even if only for two 7-minute scenes: the nightmare sequence and the interaction between The Stranger (Lorre) and Jane (Margaret Tallichet).

If you have the urge to view this early example of noir filmmaking (or is it “proto-noir?”), and decide for yourself if it is truly horror-adjacent, Stranger on the Third Floor is, at the time of this writing, available to stream from archive.org or PPV from iTunes. There is also a Warner Brothers DVD available if physical media is your preference.

For more Peter Lorre goodness, check out these episodes of Decades of Horror: The Classic Era:

M (1931) – Episode 113

MAD LOVE (1935) – Episode 81

TALES OF TERROR (1962) – Episode 92

THE COMEDY OF TERRORS (1963) – Episode 75

Gruesome Magazine’s Decades of Horror: The Classic Era records a new episode every two weeks. Up next in their very flexible schedule, as chosen by Daphne, will be Diabolique (1940, Les Diaboliques), the French classic directed by Henri-Georges Clouzot, based on a novel by Boileau-Narcejac.

Please let them know how they’re doing! They want to hear from you – the coolest, grooviest fans: leave them a message or leave a comment on the Gruesome Magazine YouTube channel, the site, or email the Decades of Horror: The Classic Era podcast hosts at [email protected]

To each of you from each of them, “Thank you so much for listening!”

Check out this episode!

0 notes

Photo

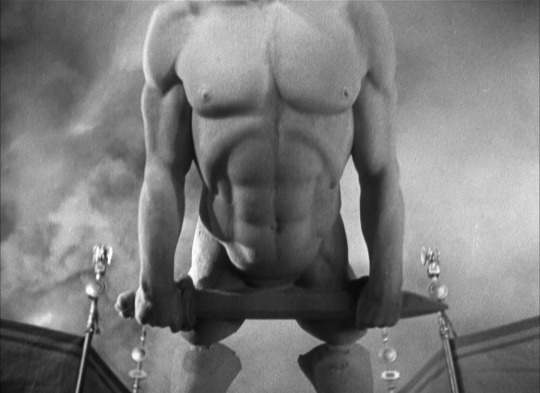

The Last Days of Pompeii (Ernest B. Schoedsack & Merian C. Cooper, 1935).

#ernest b. schoedsack and merian c. cooper#the last days of pompeii#ernest b. schoedsack#merian c. cooper#j. roy hunt#jack cardiff#archie marshek#van nest polglase#aline bernstein#marcel delgado

74 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Song To Remember (1945)

A Song To Remember by #CharlesVidor starring #CornelWilde and #MerleOberon, "even at its most ridiculous it cuts deep and isn't as middlebrow as most films of its kind made in this era were", Now reviewed on MyOldAddiction.com

CHARLES VIDOR

Bil’s rating (out of 5): BBBB

USA, 1945. Columbia Pictures. Story by Ernst Marischka, Screenplay by Sidney Buchman. Cinematography by Allen M. Davey, Tony Gaudio. Produced by Sidney Buchman, Louis F. Edelman. Music by Morris Stoloff. Production Design by Lionel Banks, Van Nest Polglase. Costume Design by Walter Plunkett. Film Editing by Charles Nelson.

Cornel Wilde receives third…

View On WordPress

#Academy Award 1945#Allen M. Davey#Charles Nelson#Charles Vidor#Columbia Pictures#Cornel Wilde#Ernst Marischka#George Coulouris#Howard Freeman#Lionel Banks#Louis F. Edelman#Merle Oberon#Morris Stoloff#Nina Foch#Paul Muni#Sidney Buchman#Stephen Bekassy#Tony Gaudio#Van Nest Polglase#Walter Plunkett

0 notes

Text

The Nitwits (George Stevens, 1935) | Art direction by Van Nest Polglase and Perry Ferguson

1 note

·

View note

Photo

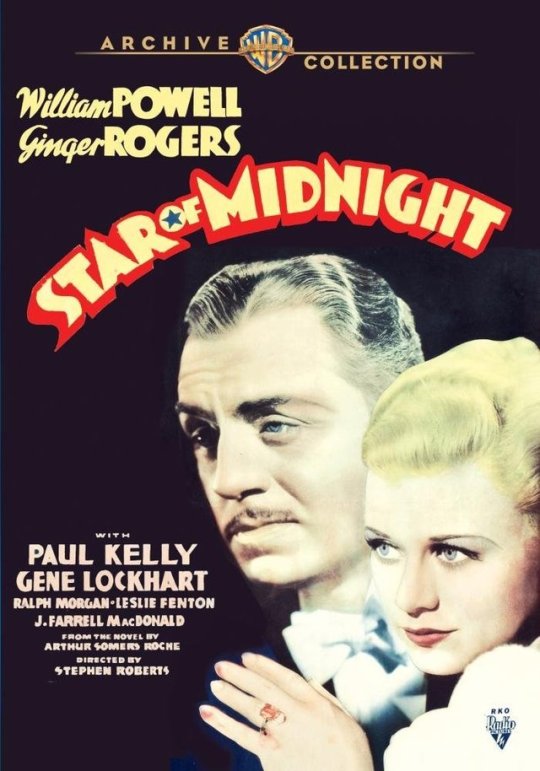

365 Day Movie Challenge (2017) - #136: Star of Midnight (1935) - dir. Stephen Roberts

Evidently attempting to capitalize on the smashing success of William Powell playing a droll and urbane sleuth in The Thin Man the year before, RKO made Star of Midnight with Powell (loaned out from MGM) and a starlet who was fast becoming one of Tinseltown’s most popular actresses, Ginger Rogers. (1935 was the same year as two of her loveliest musicals with Fred Astaire, Roberta and Top Hat.) Disappointingly, Star of Midnight’s efforts to duplicate the magic that Powell had with Myrna Loy when they played Nick and Nora Charles do not pan out.

Powell plays Clay Dalzell, a Manhattan lawyer who gets tangled up in the case of a missing stage actress. Clay and his sort-of-girlfriend, Donna Mantin (Rogers), investigate numerous suspects, including a local gangster (Paul Kelly), one of the victim’s ex-boyfriends (Leslie Fenton) and a wealthy couple (Ralph Morgan and Vivien Oakland). While the film looks beautiful on the surface – the art direction was done by Van Nest Polglase (a Brooklynite with quite possibly my favorite name of all time) and the costumes were designed by Bernard Newman – the story is tired and nonsensical. The revolving door of shady characters can’t make up for a confusing plot, nor does it help that the screenplay by Howard J. Green, Edward Kaufman and Anthony Veiller contains remarkably little wit. Supposedly Powell solves the mystery at the end, but my ability to follow the case had evaporated long before then. Star of Midnight is just as glamorous as you would hope for from a mid-30s Hollywood film, but it is a shimmering façade minus a solid foundation.

#365 day movie challenge 2017#star of midnight#1935#1930s#30s#stephen roberts#old hollywood#rko#rko pictures#william powell#ginger rogers#paul kelly#leslie fenton#ralph morgan#vivien oakland#van nest polglase#bernard newman#howard j. green#edward kaufman#anthony veiller

10 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Citizen Kane - Art Direction

Many think of KANE as the work of Welles, the auteur, which is surprising, given that its most remembered aspects are credited to Welles' crew: Toland developed his deep-focus photography while shooting THE LONG VOYAGE HOME (1940); Mankiewicz had long desired to create a multiple flashback plot (to which he added the Rosebud gimmick); and Perry Ferguson gave Kane's house the sense of infinite depth with clever innovations of muslin ceilings and incomplete sets bordered by black velvet.

Robert Carringer in The Making of Citizen Kane, while insisting on the collaborative nature of this and all films, lauds Welles' role in collecting and collating the contributions of others. Before we reject the idea that KANE is primarily Welles' film, we must remember that it is through his crew that an auteur shapes his work. With the talents of those surrounding him, Welles created the first celluloid version of his world filled with beams of light and pools of darkness. The film also delves into the themes of power, perception, passion and love that pervade his body of work. Though the innovations may not have been his, he encouraged their use and melded them into a cohesive whole. Doubt not--this is Welles' film.

Although credited as an assistant, the film's art direction was done by Perry Ferguson. Welles and Ferguson got along during their collaboration. In the weeks before production began Welles, Toland and Ferguson met regularly to discuss the film and plan every shot, set design and prop. Ferguson would take notes during these discussions and create rough designs of the sets and story boards for individual shots. After Welles approved the rough sketches, Ferguson made miniature models for Welles and Toland to experiment on with a periscope in order to rehearse and perfect each shot. Ferguson then had detailed drawings made for the set design, including the film's lighting design. The set design was an integral part of the film's overall look and Toland's cinematography.

In the original script the Great Hall at Xanadu was modeled after the Great Hall in Hearst Castle and its design included a mixture of Renaissance and Gothic styles. "The Hearstian element is brought out in the almost perverse juxtaposition of incongruous architectural styles and motifs," wrote Carringer. Before RKO cut the film's budget, Ferguson's designs were more elaborate and resembled the production designs of early Cecil B. DeMille films and Intolerance. The budget cuts reduced Ferguson's budget by 33 percent and his work cost $58,775 total, which was below average at that time. To save costs Ferguson and Welles re-wrote scenes in Xanadu's living room and transported them to the Great Hall. A large staircase from another film was found and used at no additional cost. When asked about the limited budget, Ferguson said "Very often--as in that much-discussed 'Xanadu' set in Citizen Kane--we can make a foreground piece, a background piece, and imaginative lighting suggest a great deal more on the screen than actually exists on the stage." According to the film's official budget there were 81 sets built, but Ferguson said there were between 106 and 116.

Still photographs of Oheka Castle in Huntington, New York, were used in the opening montage, representing Kane's Xanadu estate. Ferguson also designed statues from Kane's collection with styles ranging from Greek to German Gothic. The sets were also built to accommodate Toland's camera movements. Walls were built to fold and furniture could quickly be moved. The film's famous ceilings were made out of muslin fabric and camera boxes were built into the floors for low angle shots. Welles later said that he was proud that the film production value looked much more expensive than the film's budget. Although neither worked with Welles again, Toland and Ferguson collaborated in several films in the 1940s.

Peter Cowie in his "Study of a Colossus": "Kane is all things to all men."

Jorge Luis Borges: "CITIZEN KANE is a labyrinth without a center."

Francois Truffaut in his "Citizen Kane": "We [the French cinephiles] loved this film because it was complete: psychological, social, poetic, dramatic, comic, baroque, strict, and demanding. It is a demonstration of the source of power and an attack on the force of power, it is a hymn to youth and a meditation on old age, an essay on the vanity of all material ambition and at the same time a poem on old age and the solitude of human beings, genius or monster or monstrous genius."

“Mr. Kane got everything he wanted then lost it. Perhaps Rosebud was something he couldn’t get or something he lost.” In the final shot, the latter is confirmed.

http://blogs.ffyh.unc.edu.ar/fotografiacinematografica/2012/03/20/orson-welles-tecnica-y-estetica-de-la-pelicula-ciudadano-kane-2/

http://nzpetesmatteshot.blogspot.com/2013/01/citizen-kane-visual-effects-xanadu.html

http://asanziii.blogspot.com/2014_09_01_archive.html?m=0

http://www.bfi.org.uk/news-opinion/news-bfi/features/20-inspired-visual-moments-citizen-kane

http://www.criticalcommons.org/Members/anansi00/clips/film-citizen-kane-xanadu-living-room-matte/view

http://whatofthisfilm.blogspot.com/2013/03/on-citizen-kane_15.html

https://lassothemovies.wordpress.com/2012/08/21/citizen-kane-1941-afi-100-days-100-movies-1/

http://thefilmspectrum.com/?p=6111

https://books.google.com/books?id=WEJDyUCS3S4C&pg=PA38&lpg=PA38&dq=citizen+kane+van+nest+polglase&source=bl&ots=sm691O8gdc&sig=Q8XImlz5khQ58mIz5hFc0LPLeX0&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjvuIauqvjSAhWJjlQKHR5DC5s4ChDoAQgqMAQ#v=onepage&q=citizen%20kane%20van%20nest%20polglase&f=false

http://www.filmreference.com/Writers-and-Production-Artists-Ni-Po/Polglase-Van-Nest.html

http://benguaraldi.com/writings/013.html

http://filmandmusic.org/movie/details/2877/citizen-kane.html

50 notes

·

View notes

Text

OUTSTANDING PRODUCTION

youtube

WINNER

MUTINY ON THE BOUNTY

Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer

NOMINEES

ALICE ADAMS

RKO Radio

BROADWAY MELODY OF 1936

Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer

CAPTAIN BLOOD

Cosmopolitan

DAVID COPPERFIELD

Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer

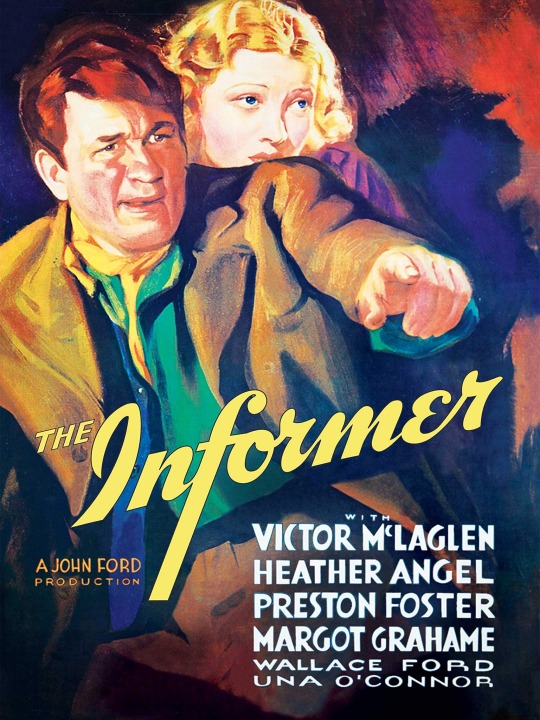

THE INFORMER

RKO Radio

LES MISERABLES

20th Century

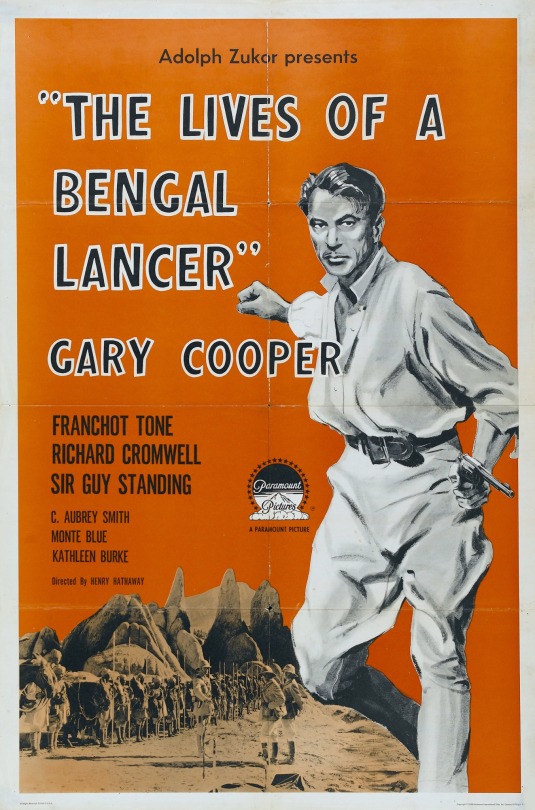

THE LIVES OF A BENGAL LANCER

Paramount

A MIDSUMMER NIGHT'S DREAM

Warner Bros.

NAUGHTY MARIETTA

Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer

RUGGLES OF RED GAP

Paramount

TOP HAT

RKO Radio

SHORT SUBJECT (CARTOON)

youtube

WINNER

THREE ORPHAN KITTENS

Walt Disney, Producer

NOMINEES

THE CALICO DRAGON

Harman-Ising

WHO KILLED COCK ROBIN?

Walt Disney, Producer

SHORT SUBJECT (COMEDY)

WINNER

HOW TO SLEEP

Jack Chertok, Producer

NOMINEES

OH, MY NERVES

Jules White, Producer

TIT FOR TAT

Hal Roach, Producer

DIRECTING

WINNER

THE INFORMER

John Ford

NOMINEES

CAPTAIN BLOOD

Michael Curtiz

THE LIVES OF A BENGAL LANCER

Henry Hathaway

MUTINY ON THE BOUNTY

Frank Lloyd

ASSISTANT DIRECTOR

WINNER

THE LIVES OF A BENGAL LANCER

Clem Beauchamp, Paul Wing

NOMINEES

DAVID COPPERFIELD

Joseph Newman

LES MISERABLES

Eric Stacey

A MIDSUMMER NIGHT'S DREAM

Sherry Shourds

CINEMATOGRAPHY

youtube

WINNER

A MIDSUMMER NIGHT'S DREAM

Hal Mohr

NOMINEES

BARBARY COAST

Ray June

THE CRUSADES

Victor Milner

LES MISERABLES

Gregg Toland

ACTOR

WINNER

VICTOR MCLAGLEN

The Informer

NOMINEES

CLARK GABLE

Mutiny on the Bounty

CHARLES LAUGHTON

Mutiny on the Bounty

PAUL MUNI

Black Fury

FRANCHOT TONE

Mutiny on the Bounty

ACTRESS

WINNER

BETTE DAVIS

Dangerous

NOMINEES

ELISABETH BERGNER

Escape Me Never

CLAUDETTE COLBERT

Private Worlds

KATHARINE HEPBURN

Alice Adams

MIRIAM HOPKINS

Becky Sharp

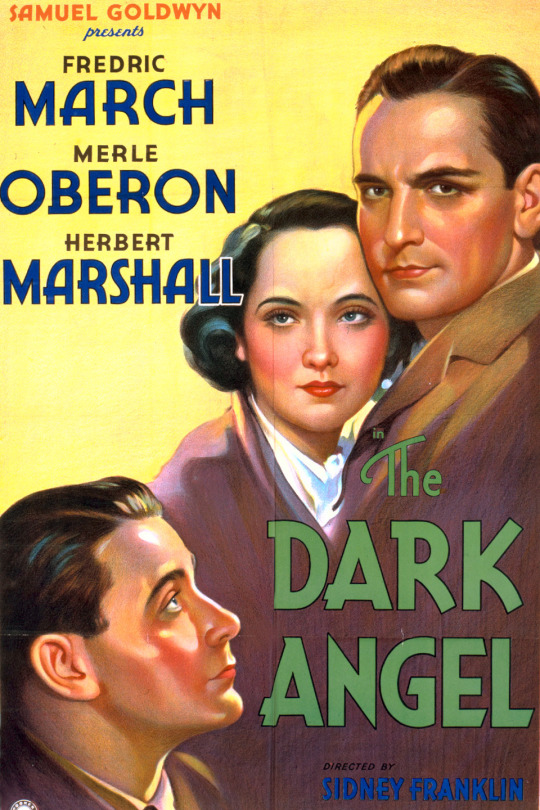

MERLE OBERON

The Dark Angel

ART DIRECTION

WINNER

THE DARK ANGEL

Richard Day

NOMINEES

THE LIVES OF A BENGAL LANCER

Hans Dreier, Roland Anderson

TOP HAT

Van Nest Polglase, Carroll Clark

DANCE DIRECTION

youtube

WINNER

BROADWAY MELODY OF 1936

"I've Got a Feeling You're Fooling" from "Broadway Melody of 1936"

FOLIES BERGERE

"Straw Hat" from "Folies Bergere"

NOMINEES

GOLD DIGGERS OF 1935

"Lullaby of Broadway" from "Gold Diggers of 1935"

GOLD DIGGERS OF 1935

"The Words Are In My Heart" from "Gold Diggers of 1935"

GO INTO YOUR DANCE

"Latin from Manhattan" from "Go into Your Dance"

BROADWAY HOSTESS

"Playboy from Paree" from "Broadway Hostess"

KING OF BURLESQUE

"Lovely Lady" from "King of Burlesque"

KING OF BURLESQUE

"Too Good To Be True" from "King of Burlesque"

TOP HAT

"Piccolino" from "Top Hat"

TOP HAT

"Top Hat, White Tie, and Tails" from "Top Hat"

BIG BROADCAST OF 1936

"It's the Animal in Me" from "Big Broadcast of 1936"

ALL THE KING'S HORSES

"Viennese Waltz" from "All the King's Horses"

SHE

"Hall of Kings" from "She"

WRITING (ORIGINAL STORY)

WINNER

THE SCOUNDREL

Ben Hecht, Charles MacArthur

NOMINEES

BROADWAY MELODY OF 1936

Moss Hart

G-MEN

Gregory Rogers

THE GAY DECEPTION

Don Hartman, Stephen Avery

WRITING (SCREENPLAY)

youtube

WINNER

THE INFORMER

Dudley Nichols

NOMINEES

CAPTAIN BLOOD

Casey Robinson

THE LIVES OF A BENGAL LANCER

Screenplay by Waldemar Young, John L. Balderston, Achmed Abdullah; Adaptation by Grover Jones, William Slavens McNutt

MUTINY ON THE BOUNTY

Talbot Jennings, Jules Furthman, Carey Wilson

MUSIC (SCORING)

WINNER

THE INFORMER

RKO Radio Studio Music Department, Max Steiner, head of department (Score by Max Steiner)

NOMINEES

CAPTAIN BLOOD

Warner Bros.-First National Studio Music Department, Leo Forbstein, head of department (Score by Erich Wolfgang Korngold)

MUTINY ON THE BOUNTY

Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Studio Music Department, Nat W. Finston, head of department (Score by Herbert Stothart)

PETER IBBETSON

Paramount Studio Music Department, Irvin Talbot, head of department (Score by Ernst Toch)

MUSIC (SONG)

youtube

WINNER

GOLD DIGGERS OF 1935

Lullaby Of Broadway in "Gold Diggers of 1935" Music by Harry Warren; Lyrics by Al Dubin

NOMINEES

TOP HAT

Cheek To Cheek in "Top Hat" Music and Lyrics by Irving Berlin

ROBERTA

Lovely To Look At in "Roberta" Music by Jerome Kern; Lyrics by Dorothy Fields and Jimmy McHugh

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Art direction for Top Hat (1935) was credited to Van Nest Polglase Van has four films in the top 133: Bringing Up Baby, The Hunchback of Notre Dame, Citizen Kane and The Devil and Daniel Webster.

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Val Lewton Horror Collection (Cat People / The Curse of the Cat People / I Walked with a Zombie / The Body Snatcher / Isle of the Dead / Bedlam / The Leopard Man / The Ghost Ship / The Seventh Victim / Shadows in the Dark)

Val Lewton Horror Collection, The (DVD) (5-Pack)

Val Lewton, a famous RKO Radio Pictures producer, redefined the horror genre with low-budget, high-box office films. Now available are nine of these horror classics on DVD in the all new Val Lewton Horror Collection. Exclusive to the collection are a new documentary on the producer and 3 of the 9 films.

]]>

Val Lewton’s name is synonymous with the subtlest, most mysterious brand of horror filmmaking in Hollywood’s golden age, and the nine horror classics he produced at RKO between 1942 and 1946 constitute the most remarkable cycle of creativity in B-movie history. (For the record, the Lewton/RKO legacy also includes two non-horror entries, Youth Runs Wild and Mademoiselle Fifi.)

Before becoming a film producer, the Russian-born Lewton was a prolific writer of pulp fiction, nonfiction, and a couple of pornographic novels. He also worked for years as assistant to David O. Selznick, a legendary producer with a distinctive personal signature–and a flair for grandiosity Lewton himself never emulated. It’s ever so revealing that, on Selznick’s Gone With the Wind, it was Lewton who came up with the idea for the famous rising shot of the Atlanta railyard filled with Southern wounded, with the Confederate flag streaming above–only he idly proposed it as a joke, never imagining that anyone would actually film such a spectacularly ambitious scene.

In 1942 Lewton left Selznick to undertake a series of horror films for RKO Radio Pictures. The studio would give him a budget around $200,000 per picture and a title RKO deemed to be grabby; Lewton would have a free hand as long as he stayed on budget, used the title, and gave the studio a salable movie of second-feature length (around 70 minutes). Over time, Lewton would increasingly have trouble with studio supervisors, but RKO was the right place for him. Although low in the pecking order among Hollywood majors, the studio made up for its lack of MGM-style glamour and Warner Bros. grit-and-gusto by working in a finely filigreed, almost miniaturist style. The art department under Van Nest Polglase and Albert S. D’Agostino was capable of exquisite artisanry, and in Nicholas Musuraca, a master of low-key cinematography and supple camerawork, Lewton found an invaluable collaborator in creating moody shadow-worlds where what you couldn’t see was more disquieting than what you could.

He was also fortunate in having Jacques Tourneur to direct his first three efforts (they had teamed years earlier on the Bastille-storming sequence for Selznick’s A Tale of Two Cities). They scored first time out of the gate with both a popular hit and a masterpiece: Cat People (1942). The story involves a pretty young Serbian woman in Manhattan (Simone Simon) convinced that her ancestors had practiced animal worship during the Middle Ages–and that she herself might shape-change into a lithe, ravening panther if her passions were aroused. The film is uncannily successful in keeping the viewer guessing whether this is a phobia borne of morbid obsession and sexual repression, or a genuine, horrific possibility. There are two sequences of matchless artistry and almost unbearable suspense–a lonely, echoing walk through pools of lamplight alongside Central Park, and a late-night swim in a deserted indoor pool–that build to throat-grabbing climaxes and remain milestones in the history of screen horror.

Many critics feel that the second Lewton-Tourneur endeavor, I Walked With a Zombie (1943), is both men’s finest work. The title is so lurid that the heroine-narrator (Frances Dee) must shrug it off with her very first words, yet the movie is an amazingly delicate and poetic piece of spellbinding–nothing less than a reworking of Jane Eyre on a voodoo island in the Caribbean. Other horror aficionados prefer the more mainline ferocity of The Leopard Man (1943), an adaptation of a Cornell Woolrich story about a serial killer strewing corpses along the U.S.-Mexican border. Although on one level this is the Lewton film that veers closest to conventional mystery-suspense, there’s no end of unsettling ambiguity (another black panther on the loose!) and hints of occultism and religious mania.

RKO promoted Tourneur to A-movies after this; Lewton would never again have so masterly a directorial partner. Yet in a weird sense (which is only appropriate), this underscores how much Lewton–with his wealth of arcane historical lore and storytelling archetypes, his quiet, patient attention to detail, and his taste for oblique narrative–was the essential auteur of all his films. Promoting first Mark Robson and then Robert Wise from the editing table, Lewton went on to make the deeply mysterious The Seventh Victim (1943) and The Ghost Ship (1943), two films in which such grotesque elements as Satan worship and murderous psychopathology are folded away inside eerily drifty, almost becalmed sleepwalks into eternal night. The Seventh Victim–a movie populated with more walking dead than Lewton’s out-and-out zombie picture–is one of the cinema’s supreme meditations on the ways lives brush against one another in the spaces of a great, impersonal city. And The Ghost Ship (the rarest of Lewton’s films, owing to a ruinous copyright suit) is like a fever dream from which the viewer never awakens.

That’s enough for a legacy, surely. Yet there remain The Curse of the Cat People (1944), a sequel that is not quite a sequel, a pretend-horror movie that’s really a contemplation of the fragility of childhood; Isle of the Dead (1945), a doomed reverie about travelers who escape the Goya-esque chaos of a 19th-century war only to be beset with plague on a miasma-shrouded island; The Body Snatcher (1945), an atmospheric Robert Louis Stevenson adaptation that invokes the grisly history of graverobbers Burke and Hare, and supplies a together-again-for-the-last-time occasion for Boris Karloff and Bela Lugosi; and Bedlam (1946), the Hogarth painting come to life to portray the real-life horrors of an 18th-century insane asylum. Bedlam‘s critical and box-office failure ended Lewton’s quasi-independent status at RKO; he would live to make only three other, unsuccessful films.

James Agee, the premier American film critic of the 1940s, reckoned that Val Lewton was one of the three foremost creative figures in Hollywood–an assessment yet more impressive when we consider that the other two were Charles Chaplin and Walt Disney. His greatest films–Cat People, I Walked with a Zombie, The Seventh Victim–are towering achievements, and even his half-realized projects are haunting experiences, the products of an utterly distinctive sensibility. This is an extraordinary collection. –Richard T. Jameson

from Products – www.Malls.biz https://malls.biz/product/the-val-lewton-horror-collection-cat-people-the-curse-of-the-cat-people-i-walked-with-a-zombie-the-body-snatcher-isle-of-the-dead-bedlam-the-leopard-man-the-ghost-ship-the-seventh-vic/

0 notes

Text

Posted by Larry Gleeson

Leonard Maltin, one of the world’s most respected film critics and historians, introduced the screening of Rafter Romance, during the 2017 TCM Classic Film Festival at the historic Hollywood Egyptian theater, built in 1922. The film stars Norman Foster and a young Ginger Rogers just before her first film with Fred Astaire, Flying Down to Rio.

Rafter Romance is a pre-code romantic comedy about two roommates sharing an apartment in a multi-level tenement on a shift basis but have actually never met. As each begins to resent the other’s bad habits, they exchange barbed notes and engage in several hilarious pranks orchestrated against each other. Meanwhile, the two meet outside the apartment and fall in love. Both are juggling careers and trying to make ends meet providing several additional, highly comedic scenes.

Rogers displays a remarkable sweetness and delicious lightness as she moves through the set designs. Dutch-born David Abel provides an eye-pleasing cinematography with a plethora of medium shots coupled with luminous tracking shots. Costumer Bernard Newman, provides several, stylish wardrobe accoutrements with full-length skirts, business suits and accompanying hats for both male and female characters.

The film’s art department of John Hughes and Van Nest Polglase created the sets while Kenneth Holmes supplied props. In addition to the apartment sets, a countryside scene with a lake and accompanying rowboat stands out. Seemingly, most of the production design was deftly constructed to showcase the closeness and intimacy of the film’s lead characters, Mary (Rogers) and Jack (Foster).

Austrian composer, Max Steiner, who would go on to win three Oscars for Best Music and achieve legendary Hollywood status, composed and directed the musical score. Interestingly, the supporting characters portrayed by George Sidney, Laura Hope Crews, Robert Benchley and Sidney Miller added an ethnic complexity that sublimely enhanced the film’s setting and narrative structure all but disappeared in post-code films.

While the Rafter Romance does have some risque pieces it wasn’t considered to have code issues, despite the suggestive title, and was remade in 1937 under stricter code enforcement as Living on Love.

Unfortunately, the film has rarely been screened in theaters since it’s initial circulation in 1933. Rafter Romance was one of six films handed over to former RKO studio head, Merian Cooper, to settle a lawsuit and he promptly removed them from circulation until their licensing for television in 1955-56. According to the TCM Classical Film Festival website, TCM acquired the films in 2006 and created restored prints with the help of Brigham University and the Library of Congress.

The print used for the screening was made possible courtesy of the TCM Collection at the UCLA Film and Television Archive. Rafter Romance, directed by William A. Seiter, had a run time of seventy-three minutes and its rather abrupt ending left the audience wanting more. Seeing Rogers’ acting chops coupled with complex characters made this a most unexpected and quite an exceptional viewing treat. I highly recommend Rafter Romance. And, for full effect, I recommend viewing the film on the big screen – the way it was made to be seen!

Capsule review @TCMFilmFest 'RAFTER ROMANCE' #tcmff Posted by Larry Gleeson Leonard Maltin, one of the world's most respected film critics and historians, introduced the screening of…

0 notes

Photo

Citizen Kane (Orson Welles, 1941).

#citizen kane#citizen kane (1941)#orson welles#gregg toland#robert wise#van nest polglase#darrell silvera#edward stevenson

102 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dance Girl Dance (1940)

Dance Girl Dance (1940)

DOROTHY ARZNER

Bil’s rating (out of 5): BBBB

USA, 1940. RKO Radio Pictures. Screenplay by Tess Slesinger, Frank Davis, from a story by Vicki Baum. Cinematography by Russell Metty. Produced by Erich Pommer. Music by Edward Ward. Production Design by Van Nest Polglase. Costume Design by Edward Stevenson. Film Editing by Robert Wise.

For many this is the masterpiece in Dorothy Arzner’s filmography,…

View On WordPress

#Chester Clute#Criterion Collection#Dorothy Arzner#Edward Brophy#Edward Stevenson#Edward Ward#Emma Dunn#Erich Pommer#Ernö Verebes#Ernest Truex#Frank Davis#Harold Huber#Katharine Alexander#Lola Jensen#Lorraine Krueger#Louis Hayward#Lucille Ball#Ludwig Stössel#Maria Ouspenskaya#Mary Carlisle#Maureen O&039;Hara#Ralph Bellamy#RKO Radio Pictures#Robert Wise#Russell Metty#Sidney Blackmer#Tess Slesinger#Van Nest Polglase#Vicki Baum#Virginia Field

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

365 Day Movie Challenge (2019) - #79: The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1939) - dir. William Dieterle

I’m in an Edmond O’Brien phase right now, as I mentioned in my recent reviews of White Heat and A Girl, a Guy, and a Gob, and since the latter film made me realize that there was more to O’Brien’s résumé than just the noir archetypes he personified in the 1940s and 50s, I ventured forth into both the later and earlier stages of his career. First, I watched the 1966 TV production The Doomsday Flight, an absorbing disaster movie written by Rod Serling that plays like Airport meets Speed (a decent copy is available for free on YouTube). O’Brien chews the scenery expertly, portraying a bespectacled bomber with both a subdued, almost elegant menace and, in the third act, an increasing mania. It’s some of the best work I’ve seen from Edmond O’Brien, and it provided an interesting counterbalance to the totally different performance I watched the next night: poet and philosopher Pierre Gringoire in RKO’s 1939 version of The Hunchback of Notre Dame.

As is probably true of everything Victor Hugo wrote, Notre Dame is not exactly a barrel of laughs. Of course, this adaptation made noticeable changes to the source material to fit the demands of Hollywood’s Production Code, resulting in a film far less grim than it might have been, and even in the two-hour running time there were various elements from the novel that were compressed or completely removed, but the aura of tragedy remains. Charles Laughton’s embodiment of Quasimodo, the deformed man who is confined to the bell tower in the Notre-Dame de Paris cathedral, is magnificently rendered in its expression of humanity. The average moviegoer in 1939 may have reacted like so many of the Parisians in the film, either cowering in terror or jeering cruelly, but Laughton shows us that Quasimodo’s disability does not make him a monster. He is a misunderstood, lonely soul who does not fully comprehend the behaviors and laws of the world outside his home.

Although the cast is stuffed with so many actors that many of them do not get adequate time to develop their characters, there are several performers who are able to make their mark. Cedric Hardwicke is perhaps my favorite among them, portraying Paris’s villainous Chief Justice Frollo with a remarkably controlled intensity, his passions always bubbling beneath the surface and threatening to boil over. Meanwhile, Maureen O’Hara and Edmond O’Brien fare quite well in their American film debuts. Prior to arriving in Hollywood, O’Hara had already appeared in a handful of British films, including Alfred Hitchcock’s Jamaica Inn (1939) with Charles Laughton; O’Brien was a New Yorker and a classically trained Shakespearean actor, having had successes on Broadway and with Orson Welles’s Mercury Theatre group. (After Notre Dame, O’Brien returned to New York to star opposite Ruth Chatterton in the John Van Druten play Leave Her to Heaven, followed immediately by the part of Mercutio in the Laurence Olivier-Vivien Leigh production of Romeo and Juliet.) I loved watching these two young actors, still new - or brand new, in O’Brien’s case - to the art of acting for the camera, already totally at ease with this style of performance. O’Hara and O’Brien bring immense warmth, not to mention physical beauty, to their roles as Esmeralda, the persecuted gypsy woman, and Pierre Gringoire, idealistic scholar.

The presence of Thomas Mitchell, Walter Hampden, Harry Davenport, Etienne Girardot, Arthur Hohl (sporting a sweet wig) and George Tobias are additionally welcome sights, regardless of their screen time. Under the direction of William Dieterle, the epic scale of the crowd scenes and the huge sets designed and decorated by Van Nest Polglase (one of all-time favorite names ever) and Darrell Silvera are tributes to their creative skill. Moreover, certain moments in Joseph H. August‘s black-and-white cinematography incorporate shadow and light in ways that recall Dieterle’s acting/directing connections to German Expressionist cinema in films like Waxworks (1924) and Sex in Chains (1928). Many flaws are obvious in this take on The Hunchback of Notre Dame, like the casting of Maureen O’Hara as a Romani character, but given the era when it was produced, it is undeniable that Dieterle and RKO put considerable effort into making the drama a memorable viewing experience.

#365 day movie challenge 2019#the hunchback of notre dame#1939#1930s#30s#william dieterle#old hollywood#victor hugo#rko#rko radio pictures#edmond o'brien#charles laughton#cedric hardwicke#sir cedric hardwicke#maureen o'hara#thomas mitchell#walter hampden#harry davenport#etienne girardot#arthur hohl#george tobias#van nest polglase#darrell silvera#joseph h. august#period piece#period pieces

2 notes

·

View notes