#aarne-thompson classification system

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

I am at my most nerdy/pedantic/verbose/unhinged prolix when I'm trying to piece together my thoughts about Cas's overcoat as a metaphorical "animal skin," especially the loss/gain of the coat as it relates to: his amnesia, his reclaiming of celestial power, the subsequent loss of sanity, and finally, staying behind in "Enchanted Woods"/Purgatory. But it doesn't even end there... He gets reclaimed and used by Heaven, and when he falls, he casts the coat away until he decides to return home again. It's... HNNNNGH.

ANYWAY. The coat is Cas’s bridge between Heaven and Earth... duty and free will... divine power and human weakness.

#the overcoat as animal skin#the lost husband archetype#the lost husband#demon dean is the reversal arc where dean gets to be the lost husband whisked away by supernatural forces#cas's coat is so symbolic and losing it is a big deal#keeping it means keeping faith in him#even when he’s gone#but without it cas is lost to forces beyond dean’s control#the one time dean burns the coat#it parallels the legends—and dean is rewarded with cas's returns to earth#aarne-thompson classification system#i mean i can go at this all day and not get tired because even the lavish BEAUTIFUL ROOM kinda fits when dean is kidnapped by heaven#but cas instead of shedding his animal skin / divine nature to stay with dean#cas holds onto it as a shield but not for himself#but to protect the human fam from supernatural forces#chooses to keep his overcoat like a suit of armor a coat of arms#but that choice comes with suffering—he remains a target#a soldier#a tool of heaven#SCREAM#i was thinking about this in relation to cas stitching and repairing his overcoat#because season 9 in particular cas is resolving to GET BACK IN THE WAR#and so he gets ahold of angelic grace he repairs his overcoat#It's SO—#cas's animal skin#dean voice *distressed* - and you're OKAY with that?#ToT

12 notes

·

View notes

Note

how goes the reading of the andersen tales? also, thoughts on the aarne-thompson-uther index?

I am approximately 2/3rds done, I took a break last week to read something else for a book club I’m in.

I’m not knowledgable enough about fairlytales and folklore to have any strong opinions on the ATU index besides it being interesting and helping me find similar and “related” stories. I imagine there is some controversy and messiness with it as is the case with all classification systems, but I haven’t read into it enough to know about that

148 notes

·

View notes

Text

All fairytale fans heard about or know about the ATU, the Aarne-Thompson-Uther classification, this international classification of folktales and fairytales in numbered types.

But do you know that there are other fairytale classifications? Local fairytale classifications? And since I am French let me present you...

The Delarue-Tenèze classification. Also known as "Le Conte populaire français" (The French Folktales), of its complete title "Catalogue raisonné des versions de France et des pays de langue française d'outremer" (Reasoned catalogue of the versions of France and French-speaking oversea countries).

This book/classification, created by Paul Delarue and Marie-Louise Tenèze, and published in five volumes between 1957 and 2000, is a study of folkloric fairytales inspired by the ATU, which it heavily borrows from and frequently references. However, the Delarue-Tenèze classification is an exclusively French system. That is to say all the folktales and fairytales studied there are originating from France, or present in countries that inherited some of French culture. The complete list of countries is: "France, Canada, Louisiana, French islands of the USA, French West Indies, Haïti, Maurice island, La Réunion". By studying, comparing and classifying the French-speaking (or French-written) fairytales of these various areas, Delarue and Tenèze managed to create a complete study of the history and evolution of essentially French fairytales, excluding all the types of stories that are typically not found on French-speaking lands.

It was thanks to the work of Delarue and Tenèze that we notably can reconstruct what the fairytales of Perrault, for example, ORIGINALLY looked like before the author took them back and rerote them. I evoked this during my Little Red Riding Hood posts (I think it was in the one titled "The dark roots"). Delarue and Tenèze, by accumulating all the French variants of the fairytale they could find, separating those that clearly were post-Perrault (they had elements newly introduced by the author) to those prior to Perrault (or at least not "contaminated" by their written cousin), and looking at the geographical repartition of these tales, they could identify which elements exactly Perrault cut out of his tale (the wolf serving meat and wine to the girl, the removing of clothes in the fire, the cat cursing under the table...) and thus re-create what the fairytale would have originally looked like.

In this extent, this work is deeply needed for whoever wants to study fairytales in France or the French folklore. Unfortunately, after two "complete editions" gathering all the volumes in 1997 and 2002, the publishing house of the catalogue fell on hard times, and closed in 2011. Since this date, the catalogue is out of print, and you can only access it by having second-hand copies or borrowing it at libraries.

However - and I just learned of this today upon looking at my references - the work of Delarue and Tenèze (both unfortunately deceased) is still continued today, or rather was taken back by a group of anthropological studies of Toulouse, who are preparing three more volumes to add to the original catalogue.

If you are interested in what each volume contains:

Volume 1 and 2 cover the "contes merveilleux" (marvelous tales/magical tales - aka the fairytales as we understand them today).

Volume 3 is about the "Animal tales", mixing animal-featuring fairytales, Reynard the Fox-type of stories, and other moral and fables inherited by popular culture from La Fontaine, Aesop and more.

Volume 4 is about the "Religious tales", aka all the French folktales, fairytales and local legends that show France's folk-Christianity, mixing the heavily Christian (Catholic-flavored) culture of France, "first daughter of the Church", with the countryside legends and tales of witches, wizards, fairies, giants and other ogres, turned into demons, saints, angels and Virgin Maries.

Volume 5 is the "conte-nouvelle" (the "short story-tales"), basically folktales that are realistic sounding and just sound like non-magical, non-religious life stories or local legends.

#fairytales#fairy tales#french fairytales#delarue-tenèze classification#fairytale classification#fairytale catalogue#atu

14 notes

·

View notes

Note

Curious: what are your favorite type of fairy stories listed in the Aarne-Thompson enciclopedia classification?

First off, it's nice to meet you and thank you for asking! Secondly, I want to preface this: I'm not a student or a scholar of folklore as a genre, and my knowledge of ATU is limited to what I've managed to find online over the years. More often than not, it's either something I've found on JStor in college, something in a Maria Tatar book, or this website.

Still, I love seeing these stories and all their variations across times and places. Without further ado:

306: The Worn-Out Dancing Shoes: I love the mystery element of this story, and I'm forever intrigued by all the variations of the other world the women travel to, whether it's the palace of Indra, the court of Satan, or something else entirely. Many versions attribute their actions to some curse that must be broken to achieve a heterosexual happy ending, but it's in the in-between that this story really sings to me. And a not-quite-variant of it, "Kate Crackernuts", may just be my favorite fairy tale of all time; how often is the ugly (or at least, "less bonny") stepsister the hero of her own story?

310: The Maiden in the Tower: I'm a sucker for a magical chase, and Rapunzel's relatives absolutely provide. My favorites include "Snow-White-Fire-Red", "The Canary Prince", and "Louliyya, Daughter of Morgan".

311: Magic Flight: Stories of magical escapes from dire situations, like "Sweetheart Roland", "The White Dove", "The Fox Sister", and "The Tail of the Princess Elephant".

407: The Flower Girl: Plants who become women or vice versa, often coupled with an escape from an abusive romance. I love these stories purely for the folkloric weirdness factor: "A Riddling Tale" (shout-out to Erstwhile for introducing me to this one), "The Gold-Spinners", "The Girl in the Bay Tree", and "Pretty Maid Ibronka".

451: Brothers as Birds: This one's purely on my love for the Grimms' "Six Swans" and "Seven Ravens". I love a resilient heroine who draws her strength from her family. I admittedly haven't read many others, but these two mean so much to me they get a place here entirely on the strength of these two.

510B: All-Kinds-Of-Fur: The story of a woman's escape from her incestuous father who then gets a Cinderella ending. I admire the heroine's courage in face of an all too real type of monster. Grimms' is a favorite, as is "Florinda" (which could also qualify as 514), "Princess in a Leather Burqa", "The She-Bear", and "Nya-Nya Bulembu".

514: The Shift of Sex: I first came across this story when I stumbled on Psyche Z. Ready's terrific thesis some years ago and I haven't been able to get it out of my mind since. All of these variations from all over the world -- I find it cathartic to know that we've been asking these questions about gender and sexuality forever, and a happy ending is an imaginative possibility.

709: Fairest of Them All: This I owe squarely to Maria Tatar's anthology from a few years ago. Unfortunately, this also means that there are several I can't find online, including "Kohava the Wonder Child" (a rare Jewish heroine in a genre infamous for how it absorbs anti-Semitism) and "King Peacock" (one of the few African American fairy tales I know, also included in Tatar's collaboration with Henry Louis Gates). I love "Princess Aubergine", "Little Toute-Belle", and especially "Gold-Tree and Silver-Tree" - my little bi self was elated to stumble across a princess who lives happily ever after with her kind and gentle limbo husband and her cunning and resourceful wife.

Even as a hobbyist, I love folklore and fairy tales. I love these little glimpses into other cultures, and I love the way these story structures act as magnets for so many nuances of people's lives across history. Still, I hope this answers your question, gives a glimpse into my experience with fairy tales as a genre, or (at the very least) gives you some new and interesting stories to read!

#ariel seagull wings#ask response#fairy tales#the six swans#12 dancing princesses#Kate crackernuts#snow white#rapunzel#the canary prince#the fox sister#sweetheart roland#wild swans#all kinds of fur#donkeyskin#fet fruners#gold tree and silver tree#Aarne Thompson Uther index#the classification system isn't perfect#because nothing is#but it's still a great resource for nerds like me who eat this stuff up like candy#I also have a whole list of fairy tales that don't fit neatly into ATU#but that's beyond the scope of this person's ask#feel free to talk to me about fairy tales any time!#I love this stuff and I love finding people to enjoy it with!

149 notes

·

View notes

Text

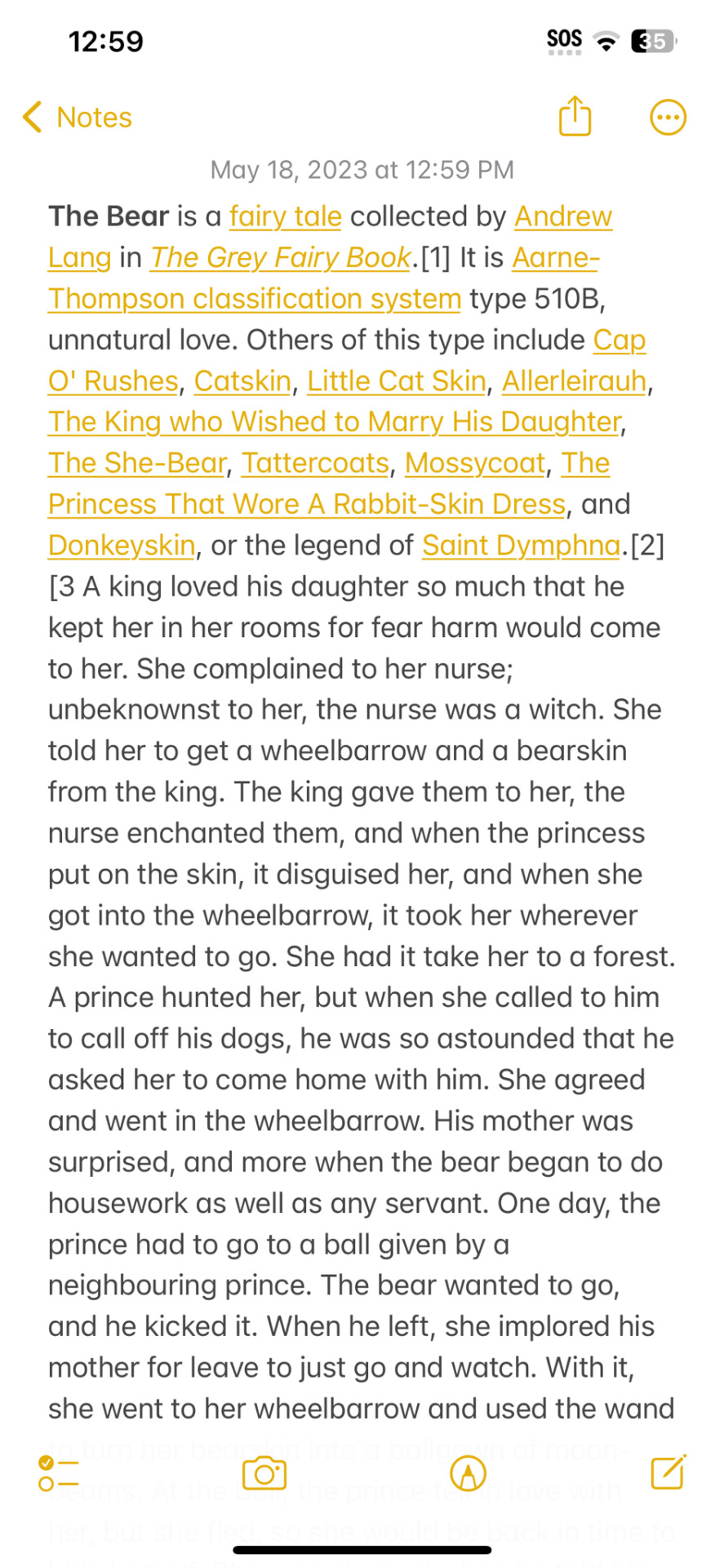

The Bear is a fairy tale collected by Andrew

Lang in The Grey Fairy Book. [1] It is Aarne-Thompson classification system type 510B, unnatural love. Others of this type include Cap O' Rushes, Catskin, Little Cat Skin, Allerleirauh, The King who Wished to Marry His Daughter, The She-Bear, Tattercoats, Mossycoat, The Princess That Wore A Rabbit-Skin Dress, and Donkeyskin, or the legend of Saint Dymphna. [2]

[3 A king loved his daughter so much that he kept her in her rooms for fear harm would come to her. She complained to her nurse; unbeknownst to her, the nurse was a witch. She told her to get a wheelbarrow and a bearskin from the king. The king gave them to her, the nurse enchanted them, and when the princess put on the skin, it disguised her, and when she got into the wheelbarrow, it took her wherever she wanted to go. She had it take her to a forest.

A prince hunted her, but when she called to him to call off his dogs, he was so astounded that he asked her to come home with him. She agreed and went in the wheelbarrow. His mother was surprised, and more when the bear began to do housework as well as any servant. One day, the prince had to go to a ball given by a neighbouring prince. The bear wanted to go, and he kicked it. When he left, she implored his mother for leave to just go and watch. With it, she went to her wheelbarrow and used the wands CLONES

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Androcles

Androcles (Greek: Ἀνδροκλῆς, alternatively spelled Androclus in Latin), is the main character of a common folktale about a man befriending a lion.

Androcles and the Lion

The tale is included in the Aarne–Thompson classification system as type 156. The story reappeared in the Middle Ages as "The Shepherd and the Lion" and was then ascribed to Aesop's Fables. It is numbered 563 in the Perry Index and can be compared to Aesop's The Lion and the Mouse in both its general trend and in its moral of the reciprocal nature of mercy.

Classical tale

The earliest surviving account of the episode is found in Aulus Gellius's 2nd century Attic Nights. The author relates there a story told by Apion in his lost work Aegyptiacorum (Wonders of Egypt), the events of which Apion claimed to have personally witnessed in Rome. In this version, Androclus (going by the Latin variation of the name) is a runaway slave of a former Roman consul administering a part of Africa. He takes shelter in a cave, which turns out to be the den of a wounded lion, from whose paw he removes a large thorn. In gratitude, the lion becomes tame towards him and henceforward shares his catch with the slave.

After three years, Androclus craves a return to civilization but is soon imprisoned as a fugitive slave and sent to Rome. There he is condemned to be devoured by wild animals in the Circus Maximus in the presence of an emperor who is named in the account as Gaius Caesar, presumably Caligula. The most imposing of the beasts turns out to be the same lion, which again displays its affection toward Androclus. After questioning him, the emperor pardons the slave in recognition of this testimony to the power of friendship, and he is left in possession of the lion. Apion, who claimed to have been a spectator on this occasion, is then quoted as relating:

Afterwards we used to see Androclus with the lion attached to a slender leash, making the rounds of the tabernae throughout the city; Androclus was given money, the lion was sprinkled with flowers, and everyone who met them anywhere exclaimed, "This is the lion, a man's friend; this is the man, a lion's doctor".

Later versions of the story, sometimes attributed to Aesop, began to appear from the mid-sixth century under the title "The Shepherd and the Lion". In Chrétien de Troyes' 12th-century romance, "Yvain, the Knight of the Lion", the knightly main character helps a lion that is attacked by a serpent. The lion then becomes his companion and helps him during his adventures. A century later, the story of taking a thorn from a lion's paw was related as an act of Saint Jerome in the Golden Legend of Jacobus de Voragine (c. 1260).[8] Afterwards the lion joins him in the monastery and a different set of stories follows.

The later retelling, "Of the Remembrance of Benefits", in the Gesta Romanorum (Deeds of the Romans) of about 1330 in England, has a mediaeval setting and again makes the protagonist a knight. In the earliest English printed collection of Aesop's Fables by William Caxton, the tale appears as The lyon & the pastour or herdman and reverts to the story of a shepherd who cares for the wounded lion. He is later convicted of a crime and taken to Rome to be thrown to the wild beasts, only to be recognised and defended from the other animals by the one that he tended.

A Latin poem by Vincent Bourne dating from 1716–17 is based on the account of Aulus Gellius. Titled Mutua Benevolentia primaria lex naturae est, it was translated by William Cowper as “Reciprocal kindness: the primary law of nature”.

Picture: Androcles

Aesop's Fables, by Aesop, Androcles, Page 1

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

What is a fairy tale

A fairy tale, fairytale, wonder tale, magic tale, fairy story or Märchen is an instance of a folklore genre that takes the form of a short story. Such stories typically feature entities such as dwarfs, dragons, elves, fairies, giants, gnomes, goblins, griffins, mermaids, talking animals, trolls, unicorns, or witches, and usually magic or enchantments. In most cultures, there is no clear line separating myth from folk or fairy tale; all these together form the literature of preliterate societies. Fairy tales may be distinguished from other folk narratives such as legends (which generally involve belief in the veracity of the events described) and explicit moral tales, including beast fables.

In less technical contexts, the term is also used to describe something blessed with unusual happiness, as in "fairy-tale ending" (a happy ending) or "fairy-tale romance". Colloquially, the term "fairy tale" or "fairy story" can also mean any far-fetched story or tall tale; it is used especially of any story that not only is not true, but could not possibly be true. Legends are perceived[by whom?] as real; fairy tales may merge into legends, where the narrative is perceived both by teller and hearers as being grounded in historical truth. However, unlike legends and epics, fairy tales usually do not contain more than superficial references to religion and to actual places, people, and events; they take place "once upon a time" rather than in actual times.

Fairy tales occur both in oral and in literary form; the name "fairy tale" ("conte de fées" in French) was first ascribed to them by Madame d'Aulnoy in the late 17th century. Many of today's fairy tales have evolved from centuries-old stories that have appeared, with variations, in multiple cultures around the world. The history of the fairy tale is particularly difficult to trace because only the literary forms can survive. Still, according to researchers at universities in Durham and Lisbon, such stories may date back thousands of years, some to the Bronze Age more than 6,500 years ago. Fairy tales, and works derived from fairy tales, are still written today.

Folklorists have classified fairy tales in various ways. The Aarne-Thompson classification system and the morphological analysis of Vladimir Propp are among the most notable. Other folklorists have interpreted the tales' significance, but no school has been definitively established for the meaning of the tales.

History of the genre

Originally, stories that would contemporarily be considered fairy tales were not marked out as a separate genre. The German term "Märchen" stems from the old German word "Mär", which means story or tale. The word "Märchen" is the diminutive of the word "Mär", therefore it means a "little story". Together with the common beginning "once upon a time" it means a fairy tale or a märchen was originally a little story from a long time ago when the world was still magic. (Indeed, one less regular German opening is "In the old times when wishing was still effective".)

The English term "fairy tale" stems from the fact that the French contes often included fairies.

Roots of the genre come from different oral stories passed down in European cultures. The genre was first marked out by writers of the Renaissance, such as Giovanni Francesco Straparola and Giambattista Basile, and stabilized through the works of later collectors such as Charles Perrault, Hans Christian Andersen and the Brothers Grimm. In this evolution, the name was coined when the précieuses took up writing literary stories; Madame d'Aulnoy invented the term Conte de fée, or fairy tale, in the late 17th century.

Before the definition of the genre of fantasy, many works that would now be classified as fantasy were termed "fairy tales", including Tolkien's The Hobbit, George Orwell's Animal Farm, and L. Frank Baum's The Wonderful Wizard of Oz. Indeed, Tolkien's "On Fairy-Stories" includes discussions of world-building and is considered a vital part of fantasy criticism. Although fantasy, particularly the subgenre of fairytale fantasy, draws heavily on fairy tale motifs, the genres are now regarded as distinct.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Folkloristics of Supernatural

So. Something interesting is happening in Season 14. I suspected that it was coming when they revealed in 12 that Jack’s name would be Jack. Jack as in “the Giant Killer” Jack. Jack like “Jack Tales.” Jack from all of the “Jack and the Devil” stories. This Jack. But Dabb is running a long mytharc, so last season was the set-up for this season-- priming the pump, if you will, for what the writers are doing now, and it came to fruition in the first few episodes.

As I said before, we got a hint of this theme in Jack’s name as well as in the way the season wrapped up with grieving Dean and Dead!Cas mirroring the last scene of despairing Cas and Possessed!Dean. Folklore brings with it the other thematic elements we’ve seen so far-- mirrors (oh my god the mirrors,) recursion and repetition, callbacks, sleep, and sleep-like death.

But why folklore *in particular*? And how is “folklore” as a theme in seasons 13 and 14 any different from the fact that this is a show *based* on folk tales?

This season, the writers are not only telling stories drawn from folklore, they are using folklore and folkloristics (the academic discipline) as a theme.

Andrew Dabb wrote a formulaic tale into the premiere, and I flipped my lid. A formula tale is one that relies on a set structure, such as the tale of Henny Penny, The Little Red Hen, or the Fisherman and his Wife, where challenges or episodes are repeated over and over until all the possibilities are exhausted or something breaks the chain. The story of Michael’s quest is a tale that relies on formula as well as on the structure of a “rule of three,” or two challenges that fail and one that succeeds. He asked a human and an angel what they wanted, before finding a monster whose desires he considered purest. Compare that structure to Goldilocks and the Three Bears, or The Three Little Pigs. I have a much more in-depth analysis of the “rule of three” that I will post later. This and other “folklore” elements in the next three episodes established this as an official “Thing on the Show.”

For now and for those of you new to the idea of the study of folklore, I’ll summarize the history of the academic discipline of folkloristics.

More than six hundred years ago, in post-Renaissance Europe, concerned scholars and bored aristocrats started doing something strange.

They started collecting folk stories from the lower classes.

This was strange because the disdain that the “upper class” (which included not just nobility and gentry but clergy and those squirrely scholars as well) felt for the emerging middle class and the peasantry can not be overstated. But perhaps because they were fascinated with that which they looked down upon, many learned men and women during the Age of Enlightenment began to study folkways and oral tales.

In the late seventeenth and early eighteenth century, “fairy tales,” “wonder tales,” “Märchen,” and “Mother Goose” stories lit up courts (and later salons) all over Europe. People recorded them from a handy peasant, wrote them down with a judicious application of upper-class refinements, and later crafted original stories inspired by them. There are works that were preserved from an oral version, like Giambattista Basile’s “Sun, Moon, and Talia” (which is based on a Neapolitan folk tale but is considered a literary work rather than a transcription and if you read a faithful translation you’d get why that is, he very much polished it with literary allusions and asides) as well as those found in Grimms’ first edition (1812) of collected oral stories which included the bloody version of “Little Red Riding Hood,” then there are folk tales that were cleaned up and sanitized for your comfort, like every Grimm edition since that one, ha ha, and at last there are “literary” fairy tales, or stories that are “original content” but were constructed on a folkish scaffolding like, Hans Christian Andersen’s “The Little Mermaid” and Oscar Wilde’s “The Nightingale and the Rose.” Authors still use fairy tales to inform and inspire-- Ellen Datlow and Terri Windling edited several anthologies of contemporary fairy tales or retellings of old tales by modern authors, beginning with Snow White, Rose Red in 1993 and ending in 2000 with Black Heart, Ivory Bones which, if you enjoy trope subversion and walking around for days bearing a lingering sense of disquiet, are seriously worth reading.

While the Grimms’ work in collecting German folk tales is considered the “watershed” moment for European folk studies (the Chinese, in contrast, have been archiving oral poetry and stories for thousands of years and Arab Muslim scholars may have started collecting folk tales as early as the 10th century CE,) it wasn’t until about a hundred years had passed from the Grimms’ first publication that the discipline took a distinctly scientific turn.

In 1910, a Finnish folklorist named Artti Aarne published a work entitled ‘Verzeichnis der Märchentypen,” or “Types of Folktales.” He had analyzed his own extensive collection of Scandinavian folk stories and realized that these tales often shared the same plots and elements—helpful animals, daring rescues, clever wives, and more-- albeit in different configurations. He broke the stories down to their essential components-- decoded their DNA, if you will-- and asserted that these story elements were used like beads on a string to construct a myriad of tales. He called these elements “Motive,” or motifs. In 1960, an American anthropologist named Stith Thompson translated Aarne’s work from the German and expanded upon it to include stories from a broader European sampling as well as Native American traditions. This became known as the Aarne-Thompson Motif Index. It is one cog in a larger academic movement during the 50’s and 60’s wherein researchers of all stripes endeavored to unearth the earliest roots of mankind—from the search for fossils of the earliest hominids, to tracing the very first languages, to reconstituting the ur-myths that shaped human culture. Academics and field researchers were determined to pinpoint the moment in time when we became more than just a bipedal primate (if we ever even have.) The Index revolutionized folkloristics as anthropologists and other scholars realized that they could trace these story motifs through time and across geography the way linguists were already doing with sounds and words to compile Proto-Indo-European, the language of Neolithic humans who settled India and Europe, and how geneticists today can trace human migrations out of Africa by studying human genomes.

The Index is a taxonomic classification system, like meteorology or the Dewey Decimal System. There are twenty-six parent categories, with subcategories and more subcategories. The Motif Index is organized alphabetically from A-Mythological Motifs (like creation myths) to Z-Miscellaneous Motifs (such as “Z210: Brothers as Heroes.”) There is an adjacent Index of Tale Types, as well, which works similarly. In the Tale Types Index, for instance, “Tales of Magic” comprise subcategories 300 to 799; one subcategory in “Tales of Magic�� is “Supernatural or Enchanted Relatives,” which covers tale types 400-459. Tale type number AT 410 is “Sleeping Beauty.” The Basile tale “Sun, Moon, and Talia,” “Sleeping Beauty in the Woods” by Charles Perrault, as well as Grimms’ “Little Briar Rose” fall under this category. The two indices operate in tandem-- for instance, the Basile story and the tale collected by the Grimm brothers are the same kind of story, but they have unique motifs. Both Perrault’s princess and the German Briar Rose are the subjects of a dire prophecy-- motif M340-- and fall into a magic sleep, which is motif D1960. Other motifs are not shared among all three stories, like cannibalism. Yeah, that story is buck wild once you go back a few generations.

Anyway, in 2004, the Aarne-Thompson Tale Type Index was once again revised, this time by German scholar Hans-Jörg Uther, in an attempt to make the index more inclusive of other global folk traditions, and it was renamed the Aarne-Thompson-Uther Classification of Folktales.

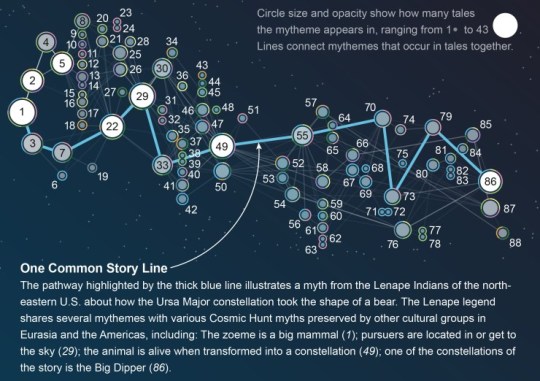

The quest to uncover the proto-stories of our ancestors continues in this very decade in the work of Julien d’Huy, who uses computer modeling to make “phylogenetic maps” of stories from around the globe. He can then create diagrams of a universal story-- for instance the “Cosmic Hunt” (D’Huy 2014).

You can also see the concept of the AT motif index in computer-generated novels and scripts, which are “written” by AIs who have ingested and digested and then assimilated whatever weird-ass shit their creators feed it and from that we get gems like “There is more Italy than necessary” from an AI-scripted Olive-Garden commercial.

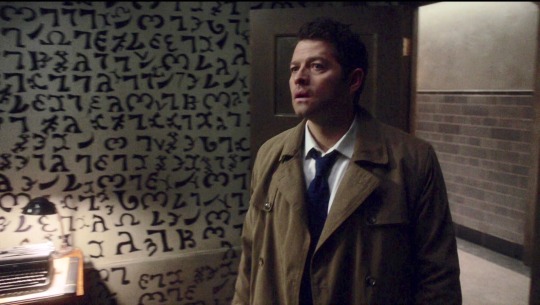

The website TV Tropes works very much like the motif index, although in a much less taxonomic fashion—for instance, one trope they describe is “Room Full of Crazy,” a “motif” if you will that tv writers often use as a way of indicating quickly to the audience that a character is off their rocker (or at least obsessive to the point of near-insanity) by showing them writing or drawing something over and over in a notebook, on their bodies, on walls, etc. Supernatural used this recently to let us know how very messed up Gabriel was after his time with Assmodeus in season 13 “Bring ‘Em Back Alive.”

But it is important to remember that Kripke has used this exact trope before, in “I Know What You Did Last Summer” to let us know that Anna was having visions and hearing what would later be known as “Angel Radio.”

To some extent, Room Full of Crazy was also used all the way back in season one in “Dead in the Water” to represent the little boy’s repressed trauma.

The repetition of tropes (or callbacks) that have already been used earlier in the series is another signal that telegraphed this shift into the realm of folk tales and mythology in a thematic sense.

Yes, Supernatural has always been about folk tales and myth. Native American stories like that of the wendigo, urban folklore like the story of the hook man and other perils of “parking,” shtrigas, skinwalkers, etc, have served as both monsters-of-the-week and Big Bads. The premise of the show draws, pishtaco-like, from world stories to survive. But we’re going to dig down and find not just the fairy tales of season 14, but the tale types and the motifs and discover what this kind of focused close-reading can tell us about this season’s values.

Lots of people point out that the Index is dry and strips away so much that you could literally tell a story just by listing the motifs in order (this comment from my folklore prof many, many years ago when we got into the motif index in class.) But that is not at all how the originators intended the index to be used. If anything, as evidenced by the “phenogenetic” tale typing of d’Huy, the presence of a folktale motif is more powerful than any literary allusion or pop-culture reference. If you realize that you’re watching a story that involves a “beat the Devil” premise, and you’ve read some of those tales, they should all light up like a constellation in your memory. You might even mentally replay the electric guitar riff from Charlie Daniels’ “The Devil Went Down to Georgia.” When we learned that the nephilim was going to be named Jack, and that his mother was hanging all of her hopes on him, you may have subconsciously thought of Jack and the Beanstalk or other Jack tales and made a prediction about the kind of story that we might see Jack feature in*. All the protagonists, all the challenges, all the outcomes of those stories will spread like beacons across a plain-- which is what comparative literature is all about in the first place. It is less about reducing a story to its DNA and more about finding that story’s family tree. And writers like Jane Yolen and the aforementioned Datlow and Windling use these bits of stories to write new ones. Oh and writers like Mr. Andrew Dabb, who used a most familiar formula (to his American audience at least) to start out the season. It’s wild, y’all.

So welcome to the folkloristics of Supernatural. As my favorite professor used to say, are there any thoughts, questions, miscellaneous abuse? My asks are open.

Here’s to a fantastic mideseason.

*allusion is not allegory, meaning you bring in an allusion to another text for depth; if you want to retell the story of Jesus and Christianity you write the Narnia Chronicles. However. Just because Jack was not the one to kill Lucifer does not mean Lucifer’s death was not foretold… the point of retelling these stories in a literary setting is to find the other values that the story can reveal, or to take a trope and twist it to reveal something that had not previously been considered.

Caveat: I’m NOT a prophet. None of us meta writers are. Nothing is stopping anyone involved in the show from making a decision that runs contrary to the story’s architecture, and it’s even been done before. I even have a post about trying to predict from the subtext or even text of a serial publication, like a tv series, that I’ll fit into this series. But anyway, use these posts to “prove” that destiel will be going canon at your own peril. And also I won’t be focusing only on “destiel” subtext. There’s stuff in these episodes for everyone, it’s chock full o’ nuts.

ALSO I have been deliberately staying away from a lot of meta while I compiled this, so if there’s more going on along these lines please feel free to tag me in :)

#the folklore of supernatural#folklore meta series#introductory post#the folkloristics of supernatural#spn meta

114 notes

·

View notes

Note

East of the Sun and West of the Moon sounds a lot like the story of Eros and Psyche.

Friend let me tell you about the wonders of story motifs

So there’s actually a system used by folklorists called the Aarne-Thompson Classification System, which evaluates folktales and categorizes them based on core motifs that appear in them. East of the Sun and West of the Moon falls broadly into the category of Type 425 (Supernatural/Enchanted Husband), and contains elements from subtypes A (Search for the Lost Husband), B (Disenchanted Husband/Witch’s Tasks), and C (Beauty and the Beast). Eros (or Cupid) and Psyche ticks so many of the same boxes that East of the Sun and West of the Moon is listed as a related page in its Wiki article, along with Beauty and the Beast.

It’s actually really impressive how stories from different corners of the world can have such similar elements -- one of my favorite examples is the Type 413 category, which (despite there not being examples listed on that page for whatever reason) includes everything from the Scottish selkie myth to the Japanese Hagoromo. Just one more amazing thing about the stories we tell <3

#answered#anonymous#folklore#east of the sun and west of the moon#eros and psyche#folktales and mythology delight and fascinate me okay#eros and psyche does have a lot of themes in common with east of the sun#but i personally prefer the narrative arc of east of the sun and west of the moon#which is why i cite it rather than eros and psyche as the core narrative

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

mythology aesthetics

ANDROCLES

Androcles is the main character of a common folktale that is included in the Aarne-Thompson classification system as type 156. The earliest surviving account is found in Aulus Gellius's 2nd century Attic Nights. The author relates there a story told by Apion in his lost work Aegyptiacorum, the events of which Apion claimed to have personally witnessed in Rome. The story reappeared in the Middle Ages as "The Shepherd and the Lion" and was then ascribed to Aesop's Fables. Androcles is a runaway slave who takes shelter in a cave, which turns out to be the den of a wounded lion, from whose paw he removes a large thorn. In gratitude, the lion becomes tame towards him and henceforward shares his catch with the slave. After three years, Androcles craves a return to civilization but is soon imprisoned as a fugitive slave and sent to Rome. There he is condemned to be devoured by wild animals in the Circus Maximus in the presence of the emperor. The most imposing of the beasts turns out to be the same lion, which again displays its affection toward Androclus. After questioning him, the emperor pardons the slave in recognition of this testimony to the power of friendship, and he is left in possession of the lion. Androcles is given money, the lion is sprinkled with flowers, and they are set free together.

#mythedit#mythologyedit#THIS WAS ONE OF MY FAVORITE BEDTIME STORIES AS A KID#Androcles#*mine#mythology#my heart is pierced by queuepid

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

Using simple fairy tale motifs to solve Voltron writing issues (2 examples)

People seem to have the thought that all story ideas must be original, and you cannot borrow or reference anything from anywhere else. But what people don’t realize is that most great stories DO borrow ideas and motifs from elsewhere; its just knowing which ones to use, how to use them, and how to make it your own. Lord of the Rings for instance uses Norse, Finnish, and Germanic mythology, as well as Tolkein’s personal experiences with WWI and the industrialization of pastoral areas from his childhood, just to name a few. Star Wars can be described as a samurai cowboy space opera with influences from Arthurian legends all the way up WWII.

One of my favorite fights in VLD itself is the clone-Shiro vs. Keith fight in “Black Paladins”. This fight pulls heavily from both the Obi-Wan vs Anakin fight (Revenge of the Sith) and Steve vs Bucky (Captain America: Winter Soldiers) in fight sequence, location, and even dialogue. I’d also visually argue that one location during the fight looks suspiciously like the drill fight from Star Trek (2009).

I’d like to examine two episodes from VLD’s s7 that might have flowed or worked better using simple fairy tale motifs. I might add more later on. Despite being born in ’91, I was orally raised on Grimm’s fairy tales by my German immigrant grandfather in such a way I wasn’t even aware they weren’t being created for me until I found a book of the tales in the bookstore. Fairy tales contain not only lessons for children to learn, but a way for culture and beliefs to pass on. When you start to compare fairy tales to each other, you’ll find that many have certain elements, or motifs, in common. (The Aarne-Thompson system is just one system that attempts to classify tales based on motifs)

“Supernatural Lapse of Time in Another Land/Dimension” to solve the 3 year time skip

And

“A Supernatural Entity Rewards an Action of the Protagonist” to solve how Voltron gets to Earth AND ease us into/provide better reasoning for “The Feud!” filler episode

“Supernatural Lapse of Time in Another Land/Dimension” to solve the 3 year time skip

Used in stories such as: Urashima Taro (Japanese), Oisin in Tir na nOg (Irish), arguably Rip Van Winkle (American), humans passing into fairy realms

Issue: Voltron believes that only a “few weeks” have passed since sacrificing the Castle of Lions. They find out that actually three decaphoebs (3 years) have passed for everyone else. How the time differences occurred is never explained (or, slightly explained, but where it sits in order of events doesn’t make sense).

VLD Context:

· Voltron fights Lotor/Sincline. Sincline uses its abilities to pop in and out of the quintessence field multiple times.

· Voltron and Sincline enter the quintessence field for an extended fight. They leave Lotor/Sincline behind.

· Appearing back in their normal reality/dimension/field, they realize that to close the rifts they have to cause a massive explosion/black hole type of force to close them. They sacrifice the Castle of Lions.

· A “few weeks” later, the group is captured by Ezor and Zethrid, who demand where they have been all this time.

· Acxa, after rescuing them, clarifies that for everyone else, three decaphoebs (equates roughly to a year) have passed.

Pidge actually offers an explanation in canon: that jumping in and out of the rift/quintessence field has caused the group to experience time slippage. This could work very well, since it follows along an old motif of where time in a different realm (fairy, supernatural, reality) passes at a different rate than the current (mortal, our world, world of origin for protagonist of tale). The problem lies in where Pidge/VLD says the time passage takes place vs. what canonically happens.

Following the Voltron group, they don’t even notice the passage of time. The audience doesn’t even pick up on this fact either until it’s pointed out by Lotor’s generals a few episodes later. However the generals (s7), direct eyewitnesses I’d like to point out, and Commander Mar sent by Honerva (s8) state that Voltron doesn’t disappear until AFTER the explosion caused by the Castle of Lions. Therefore, canonically, Voltron appears to experience the time slippage after the explosion.

Suggestion: Time passes different in the quintessence field. Allura and Lotor didn’t spend that much time in the previous episode, don’t need to change that. The split popping in and out of most of the Voltron vs. Sincline fight doesn’t need to be changed due to its speed. Concentrate on the long fight inside the quintessence field. This is where the 3 years slip. Voltron pops out, have to explode the Castleship to deal with the rifts, the explosion is what drew all the attention to the area. Have the generals’ story that they saw them disappear and never seen again.

OR

The time slippage is due to the Castleship explosion. Have Pidge state this instead.

Additional suggestion: Clarify WHY exactly the three year time needed to happen, because I still don’t understand why. The injury, death, occupations, loss, etc as the result of Voltron’s choice to turn on Lotor/their absence is never brought up/Voltron never faces it. It could happen just as poorly in an instant as it can in three years. Is it supposed to give Sendak time to attack/invade Earth? He can still do that in a single attack. Is it to build the Zaiforge canons? Have them brought with Sendak, etc.

“A Supernatural Entity Rewards an Action of the Protagonist” to solve how Voltron gets to Earth AND ease us into/provide better reasoning for “The Feud!” filler episode

Used in stories such as: So common it has an Aarne-Thompson classification (480: Kind and Unkind Girls to be exact). Essentially the hero/ine shows kindness to someone/thing and shown kindness or a reward in return, while someone who tries to follow after and treats them cruelly receives an equally cruel reward. (The male version is often, especially in Grimm’s, a kind youngest son and two evil older brothers)

Issue(s): “The Feud!” episode comes out of nowhere, and has little-to-no context for it happening, in combination of the creature/storm from “The Journey Within” inexplicably transporting/teleporting Voltron from their original location to Earth’s solar system.

VLD Context:

(The Feud!)

· With no explanation at all, the episode starts out where the five paladins, and ONLY the paladins, thrown into a gameshow

· They have to beat the gameshow to escape

· It is only after the beat the show and wake up back in their lions that:

· (1) apparently only the paladins shared a dream where

· (2) Bob, the host of the show, is revealed by Cora to be an “all-powerful, all-knowing interdimensional being who judges the worthiness of great warriors… Legends say that if you meet Bob and live to tell the tale, you are destined for great things”

(The Journey Within)

· Voltron, while flying through the dark void/space, runs into a type of nebula storm

· The storm strikes the lions, deactivating them, and freezes the non-paladin passengers

· Allura states that their paladin armor must have protected them from the shock

· (Which, correct me if I’m wrong, is a continuity error? Shiro is shown dressed in the Black Paladin armor, yet is not protected/is frozen. And again, I’d also question Allura’s armor, since its armor stylized after the paladin armor and not a part of the original set of paladin armor)

· The paladins fight a space creature, each other, and their own minds

· After defeating the… mind games…? And the creature, the storm returns.

· Instead of escaping the storm/nebula, they go through it

· This decision somehow carries the group “several thousand light years away”, and as deposits them in Earth’s solar system

I mention both of these episodes because I think you could either combine them together or into two connected, although not outright connected episodes. Or move the order so that “The Feud!” comes after “The Journey Within”.

My opinion on the filler episodes in Voltron is pretty clear on this blog: I dislike to outright hate most of them. Filler and recap episodes, though still annoying, serve a purpose in Japanese anime, especially anime that is based on a manga that is still being written. Since several chapters (usually 3) can be covered in one episode, you can catch up quickly and usually filler episodes are to give the manga time to get ahead. And I usually forgive clever recap/filler episodes that work well, disguised, or manage to fit into the plot.

For instance, I like the Monsters and Mana episode because its fun, all the characters who are present have reasons to be there, foreshadows major plot point, and results in small advances for several characters. My only complaint is that Keith and Lotor are not included. Filler episodes, such as “The Voltron Show”, immensely piss me off because we are wasting time in a shower that already doesn’t have a lot of time (repeatedly showing the whole transformation sequence, starting out at half seasons at 13 episodes then cutting it down to quarter seasons etc) or stretches a whole previously done plot point. Also, in every single one of theses filler episodes, at least one major character is missing. Both of the above episodes Shiro is inexplicably excluded.

I don’t enjoy the gameshow episode because most of the episode is trying to figure out what the fuck is going on, and why/how did the paladins get there. Then, why are the rest of the passengers excluded, why is Shiro excluded? THEN we learn that the whole thing is by this essentially god alien who judges great warriors, and if you face him and live you’re destined for great things. WHY is this character needed? This group are literally the paladins, they’ve already been chosen, and they’re the main characters, of COURSE they’re great. Ok, cool, they passed, do we get anything at least? ……. No, nothing, there’s no point. (Also WHERE has this essentially god alien been doing the past 10k years?)

Then, two episodes later, the space creature/teleporting nebula or storm. Any viewer of VLD knows that they love their deus ex machina. We, or at least I my first time viewing, know that this “tension” of being stuck out in space and slow traveling will deus ex machina itself at some point. Yet, when it happens, it still doesn’t make any sense. The nebula is said to be what teleports them, not the storm or the creature, but nebulas are essentially space clouds of dust and ionized gas.

ALSO, again, why are we excluding passengers, especially Shiro? Allura states that the paladin armor protected them, but Shiro is wearing the black paladin armor. And, technically, Allura isn’t in official paladin armor (as in from the original group).

What I think would have flowed or worked better is to move “The Feud!” episode directly after “The Journey Within”, and move the teleportation to “The Feud!” as a reward. There’s a motif that exists where, after proving themselves, the heroes are given a reward. One variation is where the hero receives the reward as a direct result of an action or kindness shown to a person or creature earlier on in the story. The hero puts a fish back into a river, the fish later arrives to retrieve the ring lost in the sea the hero has been sent to find. A powerful being disguises themselves as someone old and/or helpless, and rewards the hero for treating them kindly.

Suggestion: Voltron receives an SOS or sees someone is in trouble. You could even callback or nod to helping Rolo and group from season 1. They decide the help, despite their limited abilities at the moment. The alien is Bob or revealed to be the Bob, snaps a finger, they’re in the gameshow. We’ve now introduced some context of how the group got there, so you can enjoy what goes on. Include Shiro as a game member, include the passengers as your “phone a friend” assist in gameshows. They beat the gameshow, are deemed worthy by Bob (for their earlier stopping, for beating the gameshow, his own rules, ec), and the reward is teleporting closer to Earth.

You could even connect it to “The Journey Within” in that the storm and/or the creature they fight, as well as the inner journey the paladins go through, is the first part to getting to Bob. You could outright say this (Bob tells them), its hinted (creature is seen near Bob) or not pointed out at all (viewer may or may not pick up on it).

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

BA1b Research Narrative week 3

Fairy Tales, what is it?

Encyclopedia Britannica describes a fairy tale as:

‘a wonder tale involving marvelous elements and occurrences, though not necessarily about fairies.’

According to Vladimir Propp ‘A fairy tale may be termed any development proceeding from villainy or a lack through intermediary functions to marriage or to other functions employed as a denouement’ (1968, p. 92).

Fairy Tale doesn’t have to be your classic Disney film, but fairy tales do end ‘happily’.

‘Happily,’ means that justice is served.

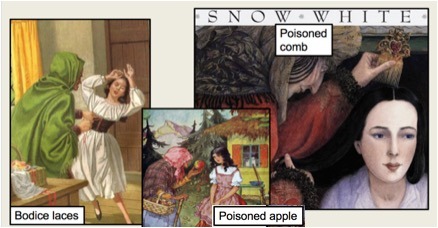

In the Grimms’ Snow White, the stepmother is forced to dance to her death in red-hot iron slippers fresh from the fireÉ This is a ‘happy’ ending.

Fairy tales come to a definite conclusion, an ‘orderly resolution’ (Warner, 1994).

The Origins

Märchen

Popular folktales, oral in origin. These pre-date written records, so it’s difficult to be sure about their exact origins. Many are hundreds, possibly thousands, of years old.

Kunstmärchen

Literary or artistic fairy tales.

Mostly produced in the 19th century, such as The Happy Prince (1888) by Oscar Wilde and The Little Mermaid (1837) by Hans Christian Andersen.

The oldest Fairy tales weren’t intended for children, but evidence suggests that they had serious meanings and contained important ritualistic elements. The clear polarity between good and evil acted as a warning of what might happen if you strayed from the righteous path. We can draw links with myth (and perhaps also religion) although myths are arguably more impossible? Because we can never be that heroic or that perfect in our actual lives.

By contrast, fairy tales, in spite of their ‘wonderful’ – or magical – aspects, are about ‘everyman’ and ‘everywoman’. Characters are rarely named (they could be us). Initiative, endurance, bravery, and patience can help everyone overcome giants, beasts and witches.

Blood and gore!

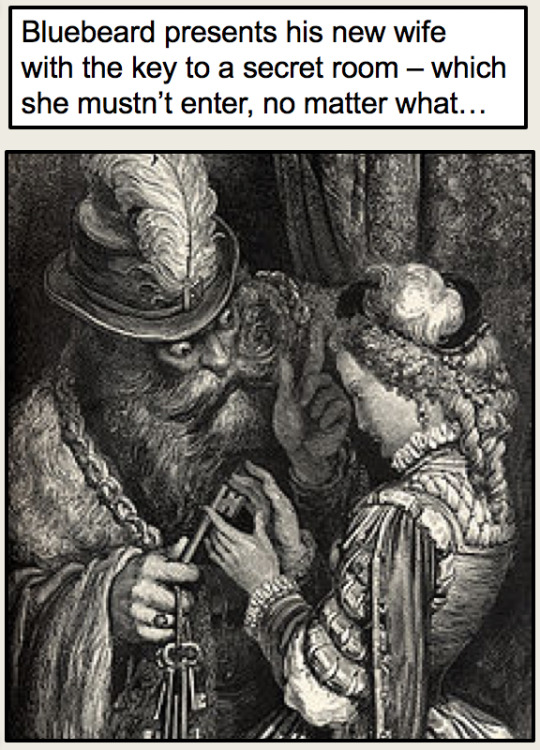

First written down by Charles Perrault (1697) Bluebeard tells the cheerful tale of a woman who marries a serial killer! The indelibly bloody key to his forbidden chamber is the only magic element in the story.

Bluebeard presents his new wife with the key to a secret room which she mustn’t enter, no matter what. Inside the room are all his dead wives (as depicted in Georges Méliès’ 1901 film version)

(In the mediaeval versions of Cinderella her step-sisters slice off their toes to fit the slipper)

The step-sisters (who are physically beautiful but inwardly ugly) are punished by having their eyes pecked out by pigeons.

This dark inversion of the birds who ‘help’ Cinderella offers another warning – suggesting that the natural world can only ever be appeased, not tamed. And the glass slipper was originally made of squirrel fur.

Pan’s Labyrinth (2006) is a great example of a modern Fairy tale done in the same aesthetic as the old medieval fairy tales.

Function 12, ‘The hero is tested, interrogated, attacked, etc., which prepares the way for his receiving either a magical agent or helper.’ (Propp, 1968, p. 39).

Sex!

In ‘The Grandmother’s Tale’ there’s no red hood (or cap). The wolf is a ‘bzou’ (werewolf) and the unnamed girl must choose between 2 paths: the path of pins (virtue) or the path of needles – needles being a symbol of ‘penetration’.

(Unlike Lucy Sprague Mitchell and others) Disney approved of fantasy

He wanted it to come ‘fully alive for those who dream’ (Stone, 1981).

‘As we do it, as we tell the story, we should believe it ourselves. It’s a “once upon a time” story and we shouldn’t be afraid of a thing like that’ (Walt Disney in notes for Cinderella, 15th January 1948, from the Disney archive).

Happy ever after?

The fairy tale scholar Jack Zipes (2011) accuses the ‘Disney versions’ of being so overwhelming that our idea of happiness is now ‘filtered through a Disney lens’. According to Zipes, these films ‘reinforce stereotypes and help maintain the patriarchal order’.

But the Grimms, writing in 1812, weren’t exactly radical gender revolutionaries.

In fact, scholars have noted that the fairy tale format begins with the disintegration of a family unitÉ and ends with the creation of another (through marriage).

Peace, stability, patriarchal order is maintained. This is the very nature of the fairy tale.

Nostalgia: the Disney version

But ironically, as noted by Zipes (1995), Disney used ‘the most up-to-date technological means to maintain the ‘old world’ order.

Animation allowed the believable creation of a fantasy world – and the recreation of a specifically ‘19th century’ patriarchal order. As Dan North (2009) says, in a (good quality!) blog about Lotte Reiniger’s fairy tale films, ‘animation allows the construction of a completely fabricated fantasy space’.

Propp’s ‘functions’ 1 and 31

Function 1

One of the members of a family absents himself from home.

Function 31

The hero is married and ascends the throne.

Before Propp fairy tale were categorised differently e.g. in the Aarne-Thompson Classification System) according to ‘type’ or ‘motif’:

• Animal stories

• Fantastical stories

• Stories of everyday life

• Stories including the appearance of a dragon

•

But many tales belonged in more than one category. The system did nothing to illuminate the underlying structure of the fairy tale. Propp was the first to make a sequential structural analysis of the fairy tale: what happens, in what order.

The Law of Contrast – other people should be antithetical to the hero; therefore, if the hero is generous, other characters should be ‘stingy’ to contradict him.

The Law of Repetition – actions in folk tales are typically repeated 3 times

The Law of Twins: two people can appear together in the same role, and should be similar in nature

The Law of Contrast – other people should be antithetical to the hero; therefore, if the hero is generous, other characters should be ‘stingy’ to contradict him. The same way Cinderella is contrasting to her evil sisters in every way, physically and mentally.

Then along came Propp…

In his 1928 work Morphology of the Folktale the Russian formalist Vladimir Propp analysed 100 Russian fairy tales and found striking similarities between them. Propp was analysing chronological story rather than plot. But please note that the traditional fairy tale – unlike many other forms of narrative, ‘which play with chronology’ (Puckett, 2016, p. 184) – is plotted in chronological order.

Propp stated 4 fundamental principles (1968, pp. 21–23)

1. Functions of characters serve as stable, constant elements in a tale, independent of how and by whom they are fulfilled. They constitute the fundamental components of a tale.

2. The number of functions known to the fairy tale is limited. As we have seen, Propp says there are only 31 (at least, in the Russian tales he analysed).

3. The sequence of functions is always identical.

4. All fairy tales are of one type in regard to their structure.

He found that all 100 of the tales he analysed were built on a pattern drawn from 31 functions, occurring in a set order. In other words, only 31 things can happen in a fairy tale. But, the word ‘morphology’ means the study of forms, and in doing this work Propp was analysing form as separate from content.

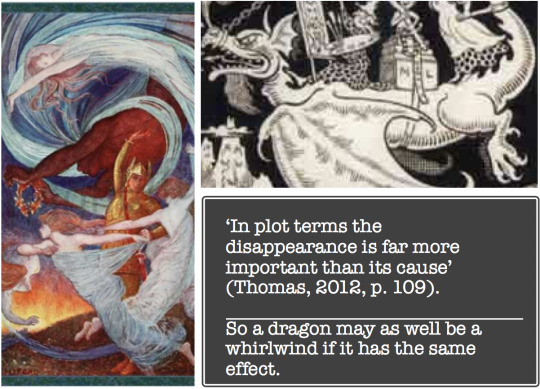

Function 14: the hero acquires the use of a magical agent.

‘It doesn’t matter (on the level of plot) whether someone is given a magic horse or buys some magic beans or steals a magic sword. The key thing is that they [i.e. the hero] have received a magical object’ (Thomas, 2012, p. 107).

Propp identified 7 key characters who each have their own ‘sphere of action’

• The Villain

• The Donor

• The Helper

• The Princess (or ‘sought-for person’) and her Father (who function as a single ‘agent’)

• The Dispatcher

• The Hero

• The False Hero

Characters are not fixed, and a single character may inhabit more than one ‘sphere of action’. If a villain inadvertently gives something important to the hero, then he or she is also at that moment acting as a donor.

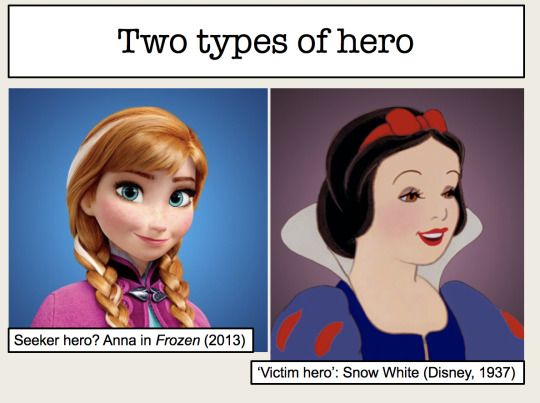

The hero: there are two types in a fairy tale

Directly suffers from the action of the villain in the complication (victim-hero)

Agrees to liquidate the misfortune or lack of another person (seeker hero)

The villain

• The villain appears twice. ‘First, he makes a sudden appearance from outside (flies to the scene, sneaks up on someone)’.

• The ‘second appearance’ is as a person ‘who has been sought out’.

The princess

• She is ‘sought after’ often a ‘reward’ that the hero (eventually) receives.

• Often bound up with her ‘father’

• appears twice, the second time ‘she is introduced as a personage who has been sought out’.

The donor

• ‘The donor is encountered accidentally’.

• The donor provides the hero with a magical object or helper (may do so unwillingly).

• Not necessarily benevolent, e.g. Rumpelstiltskin gives a magical gift to a miller’s daughter (spins straw into gold) but demands her firstborn child in return.

The magical helper is introduced as a gift

Disney’s Fairy Godmother (1950) could be seen as a donor (who presents Cinderella with ‘magical helpers’, i.e. footmen for her carriage) or as the ‘helper’ herself.

In general, the donor tests the hero somehow.

The false hero

Assumes the role of hero but is unable to complete the hero’s task, e.g. Lord Farquaad in Shrek (2001)

The dispatcher

Sends the hero away for some reason – therefore, often plays a pivotal role in inciting the action (similar to Vogler’s ‘herald’ archetype).

Function 8

‘This function is exceptionally important, since by means of it the actual movement of the tale is created’ (Propp, 1968, p. 31).

The first 7 functions ‘prepare the way for this function, create its possibility of occurrence, or simply facilitate its happening.’ (The first 7 functions set up the action.)

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Guide to Folktales in the English Language: Based on the Aarne-Thompson Classification System

A Guide to Folktales in the English Language: Based on the Aarne-Thompson Classification System

A Guide to Folktales in the English Language: Based on the Aarne-Thompson Classification System D. L. Ashliman Students of folklore and storytellers will find this new guide useful. Ashliman has followed the Aarne-Thompson classification system fairly closely in his geographical classification and his tale type headings. . . . Ashliman’s main aim is to `help readers find reliable texts of any…

View On WordPress

1 note

·

View note

Note

do you have any resources for the aarne-thompson tale type classification system? i constantly see it referenced, but i have yet to find a full list or database of them (that isnt incomplete or contradictory to other ones ive seen)

Well it depends what you mean by "finding it"... Given the Aarne-Thompson classification is originally a scholarly it is originally a set of physical books and material catalogues - so you can always try to see if there isn't a copy of it online on Google Books or the Internet Archives. This being said the AT catalogue is still an ongoing and living process currently going on - the Aarne Thompson is the AT catalogue, mixing the 1910s original catalogue by the Finnish Antti Aarne with its translation and expansion by the American Stith Thompson from the 1920s to the 1960s - but this version of the catalogue is different from the most recent one, the ATU, Aarne-Thompson-Uther, yet another revision and expansion in 2004 by German folklorist Hans-Jörg Uther... And who knows what new revision might happen next?

This might already explain the reason you found contradicting lists - there are currenty three main versions of the catalogue, from the oldest and smallest to the most recent and biggest.

That being said, if you can't buy or borrow a physical copy of the catalogues, or find an online copy somewhere, when most people of English-language refer to the catalogue on the Internet they refer to a very interesting website puts together by the University of Pittsburgh: D.L. Ashliman's library of folktexts, an online selection and collection of fairytales and folktales that uses the Aarne-Thompson-Uther classification (or sometimes the AT catalogue, without Uther) - with a few personal additions by Ashliman (for example an "Abducted by alien" category). The full list of the ATU motifs used can be found here (in alphabetical order, through the AT numbers are still kept): https://sites.pitt.edu/~dash/folktexts.html

A lot of people use this website to find a selection of variations of "fairytale" types online. It isn't as complete or thorough as the original catalogues, but it might help if you look for a quick glimpse at the catalogue online and what it can offer!

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Painting of the old Schöllenen Gorge bridge, built in 16th century but collapsed in 19th century - J.M.W Turner (from wiki) On a small bridge on the way to Auerbach, someone heard someone sneeze three times in the water; then a voice said thrice: "God help me!" And the spirit of a boy who had been waiting for thirty years in the same place was released with these words. The small bridge story has another version. It tells that a person heard someone sneezing thrice in the rivulet. Twice the voice said, “God help!” But the third time, it said: “May the devil catch you!” Suddenly the water rose high and created a wall, as if someone was violently turning it. (Stories about supernatural things related to certain type of bridges is quite common in Europe. In some places people didn’t believe that certain type of bridge structure is possible without the help of a devil. In some other places, people believed that only the blessed builders could make those kinds of bridges defeating the devil – in form of adverse geological or weather condition. Hence people’s supernatural experience while crossing the bridge became common and included as special category of folktales in Aarne-Thompson classification system of Folktales 1191. In this version of the tale, the devil probably had a treaty with the builder that he would allow the builder to finish the task and catch the first person crossing the bridge in return. Here the first person was a young boy who was caught by the devil. His soul was released only after other people crossed the bridge. Probably in some cases people still felt the devil’s presence while crossing the bridge and that’s why second version. The story was collected in 19th century but defining the time, exact location and significance of the story is difficult from this). #belief #folktale #supernatural #auerbach #germany #medieval #sagen #grimms #devil #divine https://www.instagram.com/p/CayWLyRLLjX/?utm_medium=tumblr

0 notes

Text

The Bear is a fairy tale collected by Andrew

Lang in The Grey Fairy Book. [1] It is Aarne-Thompson classification system type 510B, unnatural love. Others of this type include Cap O' Rushes, Catskin, Little Cat Skin, Allerleirauh, The King who Wished to Marry His Daughter, The She-Bear, Tattercoats, Mossycoat, The Princess That Wore A Rabbit-Skin Dress, and Donkeyskin, or the legend of Saint Dymphna. [2]

[3 A king loved his daughter so much that he kept her in her rooms for fear harm would come to her. She complained to her nurse; unbeknownst to her, the nurse was a witch. She told her to get a wheelbarrow and a bearskin from the king. The king gave them to her, the nurse enchanted them, and when the princess put on the skin, it disguised her, and when she got into the wheelbarrow, it took her wherever she wanted to go. She had it take her to a forest.

A prince hunted her, but when she called to him to call off his dogs, he was so astounded that he asked her to come home with him. She agreed and went in the wheelbarrow. His mother was surprised, and more when the bear began to do housework as well as any servant. One day, the prince had to go to a ball given by a neighbouring prince. The bear wanted to go, and he kicked it. When he left, she implored his mother for leave to just go and watch. With it, she went to her wheelbarrow and used the wands AND

2 notes

·

View notes