#achaemenid empire

Text

Gold earring inlaid with carnelian, turquoise, and lapis lazuli, Achaemenid Iran, 525-330 BC

from The Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

884 notes

·

View notes

Text

Alexander covering the body of Darius with his cloak

by Charles Meynier

#alexander the great#darius#art#charles meynier#antiquity#history#europe#european#asia#persia#persian#ancient greek#ancient greece#macedonian#macedonia#greek#greece#achaemenid empire#macedonian empire#king#persian empire

190 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Achaemenid/First Persian Empire is kind of wild. At the time of its greatest conquests it was the largest empire the world had ever seen, by a significant amount. Like any good empire it's a triumph of logistics, of course, but what's unusual is the character of the logistics in question. The kinds of empire we're used to are generally either basically maritime (Roman, Spanish, British, American) or basically horselord (Xiongnu, Parthian, Mongol, American) or Chinese (special case, the general tendency for there to exist a Chinese Empire is impressive in its own right but relatively familiar).

The Achaemenid Empire touched a lot of seas and bodies of water (Indus, Indian Ocean, Persian Gulf, Tigris and Euphrates, Red Sea, Nile, Mediterranean, Aegean and Bosporus, Black Sea, Caspian Sea) and certainly these would have been used to facilitate logistics to some degree (Persian invasions of Greece relied on naval support, for example), but it certainly seems like the fundamental lifeline of their state was their extensive system of roads. The Romans talk a big game about their road system but ultimately the major logistical corridors of the Roman state were maritime and riverine. The Inca Empire was similarly road-based, likewise a hilly/mountainous region, and is also extremely cool, but didn't last nearly as long and was much smaller.

Herodotus says: "There is nothing mortal that is faster than the system that the Persians have devised for sending messages. Apparently, they have horses and men posted at intervals along the route, the same number in total as the overall length in days of the journey, with a fresh horse and rider for every day of travel. Whatever the conditions—it may be snowing, raining, blazing hot, or dark—they never fail to complete their assigned journey in the fastest possible time. The first man passes his instructions on to the second, the second to the third, and so on." A different translation of a section of this passage is famously associated with the US postal service.

Herodotus may be wrong in the details because the actual intervals between adjacent waystations seem to have been on the order of 16-26km, a distance a rider could reach in an hour (and perhaps most relevantly, a pedestrian or army might reach in a day), and as such it's certainly plausible horses were changed more than daily, as is attested in later relay postal networks, but it's easily possible he was right about their incredible speed. A perhaps somewhat generous estimated speed of government messages along this route is ~230km/day, by analogy of the pirradazish to the Pony Express and barid systems. This would make them faster than Roman communications, though certainly we have to recognize that maritime transport is ultimately faster and more convenient for trade in bulk goods and food. All figures taken from H.P. Colburn, "Connectivity and Communication in the Achaemenid Empire" Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient 56 (2013).

That's so cool! It's several hundred BCE and they have a complex permanent relay system with stations every couple dozen km, on a system of roads running throughout an empire thousands of km from center to edge. Just for one road, like the Sardis-Susa section that the Greeks usually talk about, that's over a hundred stations, each with a stock of supplies, backup mounts and riders, accommodations, anything else they might need, and Sardis-Susa was just one possible road stretch among many. That's incredible! I wish we knew what the people who made it and ran it thought. What was the life of a gas station attendant waystation operator in the reign of Artaxerxes I like?

It's kind of tragic that the Achaemenid Empire has been marginalized historiographically for so long. Generally it was treated as significant for its invasions and meddling in Greece, for ending the Babylonian captivity, or for providing a ready-made empire for Alexander to take over. It's not nothing, other places and time periods end up with much less of an imprint on our contemporary understanding of the past. We know a lot of cool stuff. But I wish we had more reflections on Persia from within. Most of what we seem to have is reports from Greeks, fragmentary letters and steles, and precious few excavation sites.

168 notes

·

View notes

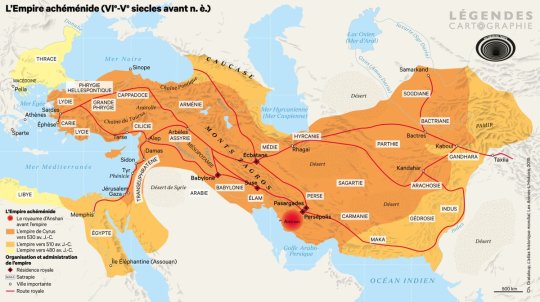

Photo

Achaemenid Empire, 5th century BC.

by LegendesCarto

100 notes

·

View notes

Text

Love, the force that moved even the mightiest of rulers. From the passionate flames of Antony and Cleopatra to the profound love and partnership of Cyrus the Great and Cassandane, these ancient love stories reveal the universal language of the heart.

#love#Cleopatra#Taj Mahal#Nero#Cyrus the great#Achaemenid Empire#Queen Victoria#Napoleon#Nefertiti#Mughal Empire#marriage#rulers#ancient#history#ancient origins

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

~ Relief fragment with the head of a Persian nobleman.

Culture: Persian

Period: Achaemenid period

Date: Time of King Darius, 522-486 B.C.

Place of origin: Persepolis , Iran

Medium: Limestone, grey

#ancient#ancient art#history#museum#archeology#archaeology#fragment#persia#persian#achaemenid empire#relief#persian nobleman#Persepolis#iran#king darius#552 b.c.#486 b.c.

525 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Silver bowl

Persian, Achaemenid Period, 6th to 5th century B.C.

Saint Louis Art Museum

#ancient art#archaeology#Persian#Ancient Persia#Ancient Iran#Achaemenid Period#Achaemenid Empire#Saint Louis Art Museum#SLAM#silver#vessel#bowl#metalwork

173 notes

·

View notes

Text

Macedonia and Achaemenid Persia Gijinka

#ancient history#ancient macedonia#ancient greece#achaemenid empire#achaemenid#ancient iran#gijinka#digital drawing

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

Archer, Achaemenid, 522–486 BC. Glazed brick. Musée du Louvre, Département des Antiquités orientales, Paris, Sb 23875. Image © RMN-Grand Palais / Art Resource, NY

218 notes

·

View notes

Text

And then getting disowned by his mom, and then being chased around all over his former kingdom, and then getting killed by Bessus, and then…

#historical memes#history#history memes#meme#memes#ancient history#historical#Persia#persian empire#achaemenid#Achaemenid empire#Darius#Darius iii#alexander of macedon#alexander the great#macedon

117 notes

·

View notes

Text

Writing in the Achaemenid Empire

“Writing in the Achaemenid Empire

Elspeth Dusinberre

Writing in the Achaemenid Empire was not necessarily used for the same purposes as in contemporary Greece. Herodotus famously mentions “the learned men of the Persians” and implies a rich tradition and practice of oral history, and the similarities in the stories of Cyrus preserved in Herodotus and Xenophon suggest such histories might be widely known even if not written down. Instead, writing in the Empire filled a wide range of particular functions that were at least sometimes distinct from the literatures of contemporary Greece.

Some of the oldest writing of the Achaemenid Empire is found on the Cyrus Cylinder, a fired clay cylinder about the size of a rugby football that was buried at the foundation of a building in Babylon shortly after 539 BCE. This artifact was inscribed in cuneiform and describes Cyrus' actions after conquering the city. The Cylinder conforms to earlier Babylonian chronicles in its shape and presentation, and it describes practices that link the new Achaemenid king Cyrus to time-honored traditions of good kingship.

The public royal inscriptions of the Achaemenid Empire begin with Darius I and fall into two major categories. The first is represented only by the inscription of Darius at Behistun, a trilingual narrative dating ca. 513 that describes Darius' rise to power. It draws on Assyrian historical annals in many ways but departs from those narratives in its presentation of Darius as a king of harmony and balance. It is perhaps the closest representative in the Achaemenid Empire to a Greek notion of “literature.” By far the majority of the royal inscriptions proclaim the kings' connection to the gods, the broad reach of their righteous rule, and the splendor of their reigns' effects. These public proclamations are often multilingual and not infrequently supported by visual representation of the sentiments they express verbally.

Another major extant category of writing in the empire is found in the form of archives. Of these, one of the earliest and largest yet excavated is the Persepolis Fortification Archive, dating to the years around 500, that documents disbursements made in food and beverages to those engaged in imperial business at and around Persepolis. It is but one of the imperial archives found so far, and the presence of family record-keeping in addition to imperial is documented in the Murashu Archive, the records of a fifth-century family agricultural business situated in Nippur. The Elephantine Archive, written on papyrus, documents the life of a Jewish military colony in upper Egypt in the fifth century. These various archives provide extraordinary records of actions, transactions, people, economic and legal systems, religion, language, gender, and much more. The seal impressions found on the clay documents provide opportunity to trace individual users and their actions even beyond what the texts alone can show.

Beyond the royal inscriptions of the Achaemenid kings, other public writings provide insight into additional aspects of life. Within Achaemenid Anatolia alone, inscriptions are used to mark graves, dedicate statues, document religious behaviors and ideas, record financial transactions, and report punishment of transgressors. From these sources we gain rich understanding of the concerns and public identities of the Empire's inhabitants.

This brings us full-circle to Herodotus and the “learned men” — although there was a formal educational context in the Achaemenid Empire, it served practical ends rather than “literary”. The written sources provide us with a notion of “arta,” or “straightness,” that pervaded elite male education even as we can follow evidence for education in accounting, religion, history, and much more. Although “literature” as we think of it may not have been expressed in writing in the Achaemenid Empire, written documents provide fertile sources for understanding human practices and thought across the vast tracts of land bound together under the imperial umbrella.”

Source: https://classicalstudies.org/writing-achaemenid-empire

Elspeth Dusinberre (Ph.D. Michigan 1997) is interested in cultural interactions in Anatolia, particularly in the ways in which the Achaemenid Persian Empire (ca. 550-330 BCE) affected local social structures and in the give-and-take between Achaemenid and other cultures. Her first book, Aspects of Empire in Achaemenid Sardis (Cambridge 2003), examines such issues from the vantage of the Lydian capital. Her second book is a diachronic excavation monograph, Gordion Seals and Sealings: Individuals and Society (Philadelphia 2005). Dusinberre's third book, Empire, Authority, and Autonomy in Achaemenid Anatolia (Cambridge 2013), considers all of Anatolia under Persian rule and proposes a new model for understanding imperialism; it was recognized by the James R. Wiseman Award from the Archaeological Institute of America in 2015. Her numerous articles have appeared in various venues, including the American Journal of Archaeology, Ars Orientalis, the Annals of the American Schools of Oriental Research, and Anatolian Studies. She is currently studying the seal impressions on the Aramaic tablets of the Persepolis Fortification Archive (dating ca. 500 BCE), and the cremation burials from Gordion, in addition to other projects at Gordion and Sardis. She has worked at Sardis, Gordion, and Kerkenes Dağ in Turkey, as well as at sites elsewhere in the eastern Mediterranean.

Prof. Dusinberre teaches primarily Greek and Near Eastern archaeology at CU-Boulder. She is a President's Teaching Scholar and has been awarded twelve University of Colorado teaching awards.

Source: https://www.colorado.edu/classics/elspeth-dusinberre

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Gold lion rhyton, Achaemenid Empire, circa 500 BC

205 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Spartans at the Battle of Plataea by Edward Ollier for Cassell's 1890 "Illustrated Universal History."

#spartans#spartan#plataea#battle of plataea#art#history#ancient greece#greece#ancient greek#greek#phalanx#europe#european#achaemenid empire#persia#persian#invasion#battle#edward ollier#illustration#aristodemus

265 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ršaka: Is there a fucking war on again? I haven't sat down in weeks, just running from exhausted horse to exhausted chapar and back, watering them and wiping off the foam all day every day.

Imaniš: Oh? Maybe there is, I haven't seen much difference here. But if they're in that much of a hurry then I suppose I wouldn't.

Ršaka: It's always the same thing with them. "Knave, hurry up! This tablet must be in Šuš tonight, the fate of the empire depends on it!" It always does somehow, the entire empire balanced precariously on a handful of clay tablets. How do they know? There could be anything written on there.

Imaniš: Imagine you're a commander sent with your troops to garrison an unruly city or something, you've left your favorite concubine or your lord's wife behind at Šuš, and you have a way to send her letters and have them arrive the same day. Two in three of those tablets have to be bad erotic poetry, right?

Ršaka: You think they ever get the erotic poetry mixed up with the military reports and tax excuses?

Imaniš: Yeah, man, it's probab- oh sorry I have a customer hold on

Imaniš walks over to the other side of the room

Imaniš: What will you be having, sir?

Tabnit: A beer, and stew if you have it.

Imaniš: Certainly. You're in luck, today's stew is lamb.

Ršaka: It's good soup! Imaniš here is a magician.

Exit Imaniš.

Tabnit: Oh, you come by often? Traveling artisan or merchant?

Ršaka: Neither, actually. I'm stableboy over at the khaneh next door. You're a traveling artisan, I suppose?

Tabnit: I suppose it was rather obvious?

Ršaka: Men judge others by their own experience.

Tabnit: And a merchant wouldn't spare a thought to us. You've caught me.

Enter Imaniš with a bowl of soup and a mug of beer.

Ršaka: What is it you make, anyway?

Tabnit, in between gulps of beer and soup: So you know swords, right? If you want to be anybody in this world, you need to have a sword. Well, they're darned expensive. So I figured out a way to make basically the same thing but cheaper and easier to make.

Ršaka: What's "basically the same thing" as a sword?

Tabnit: Well, a sword is basically a shaped chunk of metal with a handle built or wrapped around one end. But metal is expensive. So what I've developed is a shaped chunk of plaster with metal wrapped around, in this case, the other end. Lighter, cheaper, and just as good for most purposes.

Imaniš: I'm sorry, how is that just as good? Surely it would break on the first blow?

Tabnit: Well, if you think about it, any time you're actually hitting something with the sword, things have already gone very very badly for you. The point of the sword is to show it off, not to actually use it. And my sword is just as good for that main purpose.

Ršaka: It's a sword. It's for killing people. That's what a sword does.

Tabnit: Hardly! When's the last time you've seen someone pull out a sword?

Ršaka: Why, just last week!

Tabnit: And when's the last time you've seen a sword used to do what "a sword does".

Imaniš: That must have been last spring, right? When the road counters found the guy who kept making those indecent drawings of the satrap.

Ršaka: All right, I see your point. If I needed to carry a sword I might well buy one of yours, so what's got you on the road like this and not in a nice comfortable workshop?

Tabnit: Well, you see, I didn't actually tell the customers what the deal with the swords was. Fortunately none of the people coming after me had a useful weapon, but I still had to skip town quick. Next time I'll register myself as a sculptor. Maybe I should have a scribe write me a disclaimer, too.

#original fiction#for a given value of original#Achaemenid Empire#life of an Ancient Persian gas station attendant

17 notes

·

View notes

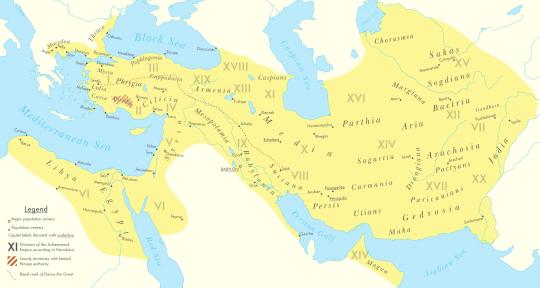

Photo

Achaemenid Empire of Persia at its greatest extent founded by Cyrus The Great in 550 BC.

96 notes

·

View notes

Text

Xerxes I, a formidable historic figure, is the most famous of the Persian Empire’s kings. He’s mainly known as the man who defeated the Spartans at Thermopylae, but who ultimately lost to the Greeks.

22 notes

·

View notes