#agwe tawoyo

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Note

What advice would you say to anyone about initiation into vodou? Asking because the loa told me I not only needed to initiate but marry (Agwe tawoyo) urgently and I have noticed an abundance of good changes since my readings but this all came with a lot of unexpected news and I would like advice about how to make sure I have the spoons to make it through the path to initiation without getting so upset.

Hi,

So, I regard having to do anything as huge as kanzo and maryaj lwa urgently as something that needs a lot of push back. There are very, very few reasons things with that much life change and spiritual significance need to hurried, and even then a solid houngan or manbo can help slow the process down. The only real reasons I would entertain hurrying for would be imminent death of the person asked to do those ceremonies or their child, or crippling, life-threatening illness...and there are still stopgaps that can be employed to prolong life and give enough time to plan and mount those ceremonies. There is a lot of time and effort that go in, nevermind money.

So, I would want to know why the need for urgency. Because the lwa want it that way is not a good reason; the lwa must respect their people and negotiate for what they want. If folks allow, the lwa will make immediate demands but it is a houngan/manbo's job to help negotiate that and help you stand your ground. I would also ask what they are seeing as urgent; is that with a year? Within five years? Time for spirits is different than time with us.

I also recommend a lot of slowness before initiation. Before someone even considers going into the djevo, they should be present and active in the community that will support the initiation for honestly years. Go to lots of ceremonies and observe, get your hands in the work, meet the members of the house and see if you vibe with them. Spend a lot of time with the person who would mount the initiation for you and learn who they are. Get to know the spirits. Without all of that, you are being dumped in the deep end without knowing how to swim. The work of initiation can never be undone, so choosing wisely and with a lot of discernment is necessary.

With maryaj, it is very often not just one spirit; it is multiple to hold us in balance, provide the optimal protection, and prevent destructive jealousy. Many houses do all those spirits in one ceremony to reduce the need for more and to conserve money. Marrying only one risks needing to do more ceremony in the future to appease unhappy lwa.

Additionally, you wouldn't marry a person you didn't know quite well so you shouldn't be marrying spirit who you don't have at least passing familiarity with. Forging relationships is important. And, maryaj comes with requirements that affect current or future intimate partners. Maryaj and kanzo also have lifelong obligations that need to be met over time.

Just because spirit lays something down as a need, urgent or otherwise, doesn't mean you should immediately pick it up. They cannot and should not demand immediate answers and need to respect your free will. An ask does not mean you have to do it and, quite honestly, does not mean you should. Spirits ask for lots of things, and sometimes the answer is yet but sometimes the answer is no.

I also would want to know why they want initiation. What do you gain from it? They gain a lot, but what's in it for you? How are they going to help you? How do you and your life benefit from this?

The lwa can definitely pave the way after giving big news but that also doesn't mean you should say yes or that it would be beneficial for what you want for yourself. Running fast into something like initiation or permanent bonds of marriage with spirit is a recipe for disaster. Too often people are in a hurry, and then things go poorly for them. Initiation should not be then first thing done in the religion or the first motion of participation in a community. It should be a natural development of growth.

You can't make sure you have the spoons to make it through these processes. Initiation is a difficult, grueling, uncomfortable process that takes you apart and puts you back together, and the process is longer than the actual ceremonies. There is lead up and there is what happens after and it can take awhile for your life to come back to center. If you don't think you have the spoons to do it without it wrecking you or making you upset, you should not do it or should wait until you feel you are more ready.

You additionally can't plan for preparation in any particular way that preserves you because you don't know what the process will require for you. My road to my kanzo required that I shed almost everything important to me; I gave up a job and career path, my home, my car, most of my belongings, and relationships that I had thought were lifelong. That's not the way for everyone but the path to get to kanzo has sacrifice involved. Maryaj is not dissimilar; it required permanent changes to intimate relationships that have consequences if not met.

So...no easy answers. Don't rush, and don't allow pressure from spirits or people make the decision for you. You need a solid foundation before going into either of these ceremonies, and you should not be asked to do things quickly without really specific reasons and after other interventions happen to measure the impact on the situation. You wouldn't jump into life changing processes in other areas without a lot of discernment, so do the same here.

If there is indeed a life threatening situation involved, ask for what can be done immediately to assist in slowing that down or resolving it in a way that does not involve rushing. There are always options.

I hope this helps! Happy to chat more if that feels helpful.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

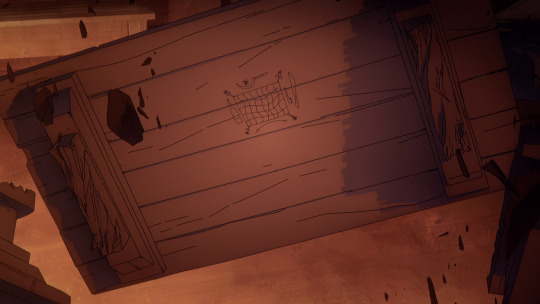

Vodou symbolism in Castlevania Nocturne

Vodou developed among Afro-Haitian communities amid the Atlantic slave trade of the 16th to 19th centuries. Its structure arose from the blending of the traditional religions of those enslaved West and Central Africans, among them Yoruba, Fon, and Kongo, who had been brought to the island of Hispaniola. There, it absorbed influences from the culture of the French colonialists who controlled the colony of Saint-Domingue, most notably Roman Catholicism but also Freemasonry. Many Vodouists were involved in the Haitian Revolution of 1791 to 1801 which overthrew the French colonial government, abolished slavery, and transformed Saint-Domingue into the republic of Haiti.

At the heart of Vodou are the symbols known as vèvè. These cosmograms are intricate drawings made with cornmeal, coffee, or flour, and they serve as the visual representation of the spirits and deities (known as lwa, also called loa or loi) honored in Vodou. Each vèvè corresponds to a specific spirit, and invoking them involves drawing the corresponding symbol on the ground. This is often performed by an initiate who has learned the technique and is an essential part of Vodou rituals and ceremonies.

Let's look at some of the symbolism shown in Nocturne.

1. Agwe Arroyo or Agwe Tawoyo/Agwe 'Woyo - "Agwe of the Streams"

Captain of Immamou, the ship that carries the dead to the afterlife. He cries salt-water tears for the departed. He assisted the souls of those that suffered crimes against humanity during the trans-Atlantic slave trade. Agwe is called to calm the waves of the sea or ensure happy sailing, but mainly he is worshipped by those who fish and whose life depends on the life in the waters. People under his protection will never drown and water will never harm them.

2. Kouzen Zaka, or Azaka

The patron lwa of farmers, but he is also known as a lwa travay, a work lwa. Kouzen Zaka, represented by this vèvè, is the guardian of the fields in Haitian Vodou. The drawing of his symbol showcases elements of agricultural activity, including the earth, machete, sickle, hoe. Zaka is closely tied to work and is revered by farmers and those who rely on agriculture for their livelihood.

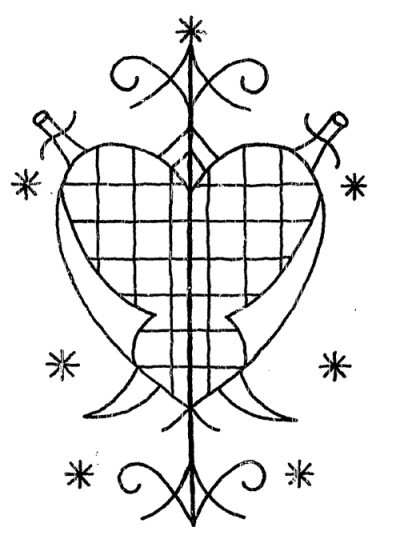

3. Erzulie Dantò or Ezilí Dantor

The main lwa of the Petwo lwa family in Haitian Vodou. She is a powerful and protective mother figure, often depicted holding a knife, symbolizes justice and will forcefully fight to protect her children, who are her loyal followers. She is a single mother, a Haitian peasant who is fiercely independent and takes care of her own, a strong protector of women and children.

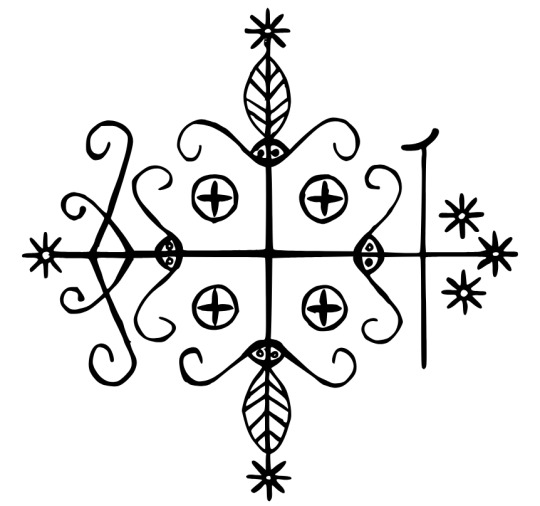

4. Legba: The Guardian of the Gates

Papa Legba, the first spirit to manifest during a Vodou ceremony, holds a special place in the Vodou Pantheon in Haiti. His vèvè symbolizes his role as the barrier between the two worlds, with two perpendicular axes and his cane. Known as a trickster Loa, he usually appears as an old man on a crutch or with a cane, wearing a broad-brimmed straw hat and smoking a pipe, or drinking dark rum. The dog is sacred to him. He carries a sack on a strap across one shoulder from which he dispenses destiny. He is believed to speak all human languages. In Haiti, he is the great elocutioner: Legba facilitates communication, speech, and understanding. During Vodou ceremonies he opens the spiritual gateway that separates the Loas from our physical world.

In addition, Papa Legba is the guardian of portals, doors, and crossroads. His role is critical in any Vodou ritual, as he's the one who grants access to the other Loas and allows them to manifest themselves during the ceremony.

What we hear Annette chant in the series is 'Papa Legba: Ouvè Baryè'a' (Papa Legba: Open the Gate).

There's a lot more to dive into, but this was a summary.

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

Agoé t’Arroyo

Agwe Oyo, Agwe Tawoyo, Move tan bare’m Agwe Oyo, Agwe Tawoyo, Move tan bare’m sou lanmè a mwen ye

0 notes

Text

Koki lanmè m!

.

63K notes

·

View notes

Text

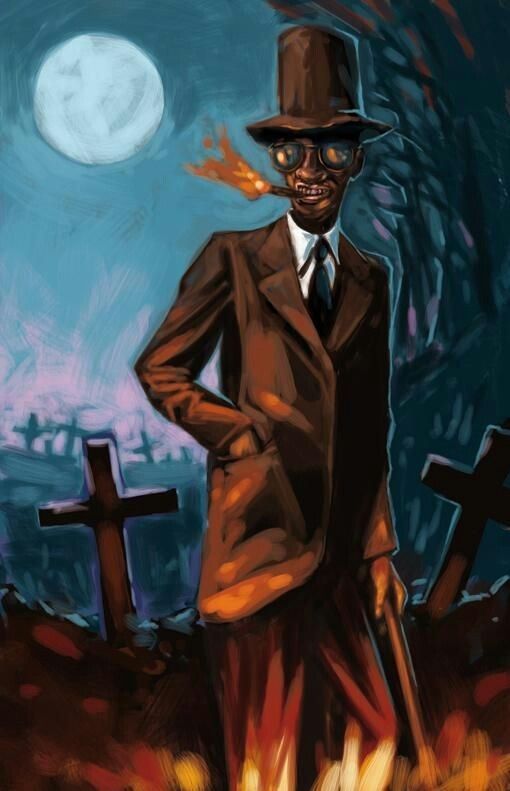

Gede Family (Haitian Vodou)

The Gede (French: Guede) Gede are the dead–spirits who were once human and have since been elevated (by Bawon) to serve as Gede. There are Gede of all genders.

The Gede are souls that never went through the funeral rites and became lost then Baron finds then and elevate them to Gede.

They are the family of spirits not Lwa, that represent the powers of death and fertility. All are known for the drum rhythm and dance called the "banda". Banda is danced at funerals to assist the passage of the dead to the world of the spirits within vodou thinking about death is the notion of rebirth. The dance is a sexual dance with grinding , cussing etc..

The Gedés are spirits and guardians of the dead. The dead reside in the cemetery, but so do liminal spirits who straddle the frontier between life and death.

Gede is born under the water, of souls that are unclaimed by families, usually. Bawon selects souls to serve as Gede and does whatever he does to make that particular Gede, and then the new Gede exists. Even very well known Gede like Gede Nibo or Gede Mazaka vary wildly from lineage to lineage.

The Barons are a family of lwa who are the aspect of life of death. They oversee the Gede.

In possession sometimes they can be the life of the party in most lineages it can be the exact opposite. In possession, he falls to the ground and is arranged as a corpse.

Baron Samedi.: is the leader of the Gede family, he's the lwa that represent death. He's the chief spirit of the dead, the Baron guards the veil between life and death, welcoming new souls into the underworld and deciding who lives and who dies. He is recognized as a man with a high hat on his head, sunglasses with one lens gone who likes to smoke cigars. Papa Gede- is a spirit who guides souls into the afterlife. He is a great healer when it's a life and death situation. can help with fertility and is fine if children.

However, he is also the patron of young children and a great healer, when there is a life or death situation.

Barons Cross in Haiti.

Maman Brigitte ("Mother Bridget") is the wife of Baron Samedi. She is syncretized with St. Brigid, perhaps because she is the protector of crosses and gravestones.

Now some may say that Gran Brigit is not presented as white and she may not be, some consider her to be a light skinned black woman. When you have a lwa spirit who embody death, such as her and her husband Bawon Samdi, sometimes they can often appear pale because they are deceased. They are other spirits that do portray themselves passing for white like Damballah Wedo, Agwe Tawoyo, Ezili Freda, Ogou Sen Jak, and others.

For practitioners of Haitian Vodoun and the New Orleans Voodoo religion, Maman Brigitte is one of the most important loa. Associated with death and cemeteries, she is also a spirit of fertility and motherhood.

She can be called on for a number of different matters. Like healing—particularly of sexually transmitted diseases—and fertility, as well as divine judgement. She's known to be a mighty force when the wicked need to be punished. If someone suffers from long term illness, Maman Brigitte can step in and heal them, or she can ease their suffering by claiming them with death.

"We here in New Orleans call upon Mama Brigitte to clear our path of negativity and evil, to help our memory and to bring us the protection and wisdom of our Ancestors and Spirit Guides."

Brav Gede: is the guardian and watchman of the graveyard. He keeps the dead souls in and the living souls out. He is sometimes considered an aspect of Nibo.

Gede Bábáco: is Papa Guede's lesser known brother and is also a psychopomp. His role is somewhat similar to that of Papa Guede, but he doesn't have the special abilities of his brother.

Gede Nibo (Haitian Creole) is a lwa who is leader of the spirits of the dead in Haitian Vodou. Formerly human, Gede Nibo was a young man who was violently killed.

After death, he was adopted by Baron Samedi and Maman Brigitte. Nibo wears a black riding coat or drag. He is a intermediary between the living and the dead. And is the patron of those who died by unnatural causes (disaster, accident, misadventure, or violence). He can help to give a voice to the dead spirits whose bodies have not been found or that have not been reclaimed from "below the waters".

"Baron Kriminals" is the enforcer of the Gede. He was the first person to kill another (probably Nibo). He's the second man to be buried in the cemetery. As the first murderer, he is master of those who murder or use violence to harm others. He's the guardian of the cemetery and watch over the tombs and what's in them. He has a skull painted face and smokes a cigar and rest under the tallest tree in the cemetery. He call sometimes captain zombi you'll see him in an image wearing a bottle around his neck which contains the zombies spirits in the bottle. He is called apon to help when the matter is serious not when ever you want to. The families murder victims and the abused pray to him to get revenge on those who wronged them. He's know to work with Met Kalfu. You can put a pic of him by the door to protect from criminals.

He is syncretized with St. Martin de Porres, perhaps because his feast day is November 3, the day after Fèt Gede.

Baron LaCroix, says to be Barons brother, but he's the cemetery groundskeeper and maintains the graves. He is one of the Gede, a lwa of the dead and sexuality along with Baron Samedi and Baron Cimetière in Vodou. He is syncretized with Saint Expeditus. Baron La Croix is also known as Azagon Lacroix. He's another aspect of Semedi not the same but similar.

He is generally not invoked unless under certain circumstances but people avoids him do to can try to kill and turn one to a zombi.

Baron Cimetière is one of the Gede, a spirit of the dead, along with Baron Samedi and Baron La Croix in Vodou. He is said to be the guardian of the cemetery, protecting its graves.

Ghede Masaka and Ghede Oussou Known as the twins, these two Loa are Haitian Voudou’s gravediggers gifted with divine insight. Masaka is depicted as an androgynous or transgender male who assists Ghede Nibo, while Oussou is his rum-loving brother dressed in opposite colors.

Baron Del Cementario: Although technically Baron Del Cementario’s name is the Spanish version of the French Baron Cimitière, (they are not the same spirit.) In the Vodou traditions of the Dominican Republic, the first man buried in a cemetery becomes that cemetery’s Baron Del Cementario. To identify or contact him, locate his grave. In Dominican tradition, Baron Del Cementario is the Baron with the closest relations with the living, perhaps because he, unlike most Barons, has had a relatively recent human incarnation.

JustBaron Del Cementario is contacted or invoked in the cemetery at midnight. Enter by one gate; make your offerings and petition, then leave by another gate, not the one by which you entered. Throw nine coins over your left shoulder (have them ready in your pocket) and then go home via a circuitous route without looking back.

#Ghede family#Voodoo#Vodou ghede#Lwa Spirits#Spiritual#Vodou spirts#Subscribe#follow#like and comment#like and/or reblog!#update post

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

Deidades Africanas y Caribeñas por A

Deidades Africanas y Caribeñas por A

Agoué-Taroyo

Agwetawoyo, Agwe Tawoyo, Agoué-Taroyo, Agoué t’Arroyo, Agweta Woyo, Agoué-Woyo, Agoué Arroyo – Caribe – Haïti (vaudou) – denominación de Agoué, que reina sobre el mar; [cf., en el idioma fon, agwé, “orilla” y arroyo, “el mar”].

Agoussou

Monsieur Agoussou, Agoussou Green, Agassou – Norteamérica – Luisiana (vudú) – dios del amor y de la victoria sobre los enemigos; [el apellido…

View On WordPress

0 notes

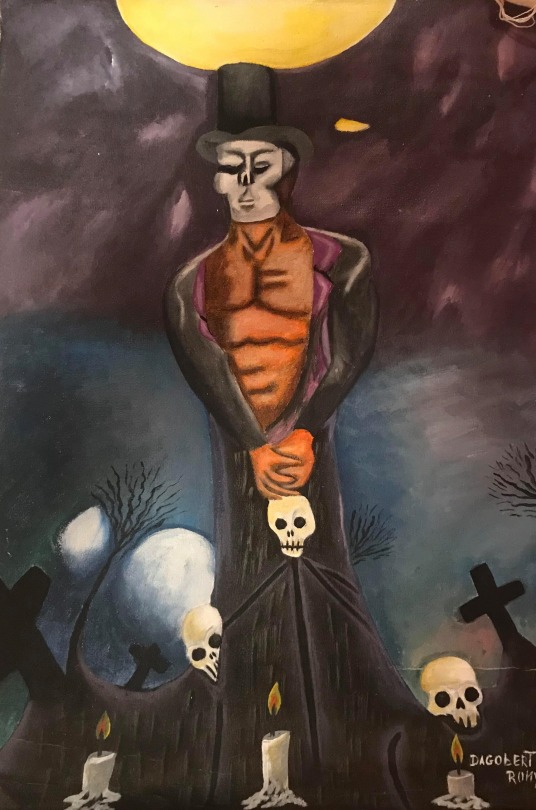

Photo

Haitian Vodou Haitian Vodou, called Sevis Gineh or “African Service”, is the primary culture and religion of the approximately 7 million people of Haiti and the Haitian diaspora. It has its primary roots among the Fon-Ewe peoples of West Africa, in the country now known as Benin, formerly the Kingdom of Dahomey. It also has strong elements from the Ibo and Kongo peoples of Central Africa and the Yoruba of Nigeria, though many different peoples or “nations” of Africa have representation in the liturgy of the Sevis Gineh, as do the Taino Indians, the original peoples of the island we now know as Hispaniola. Haitian Vodou exists in Haiti, the Dominican Republic, parts of Cuba, the United States, France, Montreal, and other places that Haitian immigrants have dispersed to over the years. Other New World traditions it is closely related to or bears resemblance to include Jeje Vodun in Brazil, La Regla Arara in Cuba, and the Black Spiritualist Christian churches of New Orleans. Haitian Vodou also bears superficial resemblances in many ways with the Nigerian Yoruba-derived traditions of Orisha service, represented by La Regla de Ocha or Lukumi, aka “Santeria”, in Cuba, the United States, and Puerto Rico as well as Candomble in Brazil. While popularly thought of as related to Haitian Vodou, what is commonly referred to as “voodoo” in New Orleans and the southern US is a variant of the word “hoodoo”, also called “rootwork” or “root doctoring”. This is a folk magical tradition from Central Africa in the Congo region in which roots, leaves, minerals, and the spirits of the dead are employed to improve the lot of the living, often including the reciting of Psalms and other Biblical prayers. Rootwork also incorporates Native American herb lore and European and Jewish magical traditions. As a folk magic tradition, New Orleans “voodoo” and southern “hoodoo” rootwork are distinct from the RELIGION of Haitian Vodou and its siblings and cousins. Haitian Voodoo History Vodou as we know it in Haiti and the Haitian diaspora today is the result of the pressures of many different cultures and ethnicities of people being uprooted from Africa and imported to Hispaniola during the transatlantic African slave trade. (1) Under slavery, African culture and religion was suppressed, lineages were fragmented, and people pooled their religious knowledge and out of this fragmentation became culturally unified. In addition to combining the spirits of many different African and Indian nations, pieces of Roman Catholic liturgy are incorporated to replace lost prayers or elements; in addition images of Catholic saints are used to represent various spirits or “misteh” [“mysteries”], and many saints themselves are honored in Haitian Vodou in their own right. This syncretism allows Haitian Vodou to encompass the African, the Indian, and the European ancestors in a whole and complete way. It is truly a “Kreyol” or Creole religion. The most historically important Vodou ceremony in Haitian history was the Bwa Kayiman (Bois Caiman) ceremony of August 1791 near the city of Cap Haitien that began the Haitian Revolution, led by the Vodou priest named Boukman. During this ceremony the spirit Ezili Dantor came and received a black pig as an offering, and all those present pledged themselves to the fight for freedom. This ceremony ultimately resulted in the liberation of the Haitian people from their French masters in 1804, and the establishment of the first and only black people’s republic in the Western Hemisphere, the first such republic in the history of the world. (2) Haitian Vodou came to the US to a significant degree beginning in the late 1960s and early 1970s with the waves of Haitian immigrants under the oppressive Duvalier regime, taking root in Miami, New York City, Chicago, and other cities mainly on the two coasts. Core Beliefs of Haitian Vodou Vodouisants believe, in accordance with widespread African tradition, that there is one God who is the creator of all, referred to as “Bondje”, from the French words “Bon Dieu” or “Good God”. Bondje is distant from his/her/its creation though, and so it is the spirits or the “mysteries”, “saints”, or “angels” that the Vodouisant turns to for help, as well as to the ancestors. The Vodouisant worships God, and serves the spirits, who are treated with honor and respect as elder members of a household might be. There are said to be twenty-one nations or “nanchons” of spirits, also sometimes called “lwa-yo”. Some of the more important nations of lwa are the Rada (from Allada in Dahomey), the Nago (from Yorubaland), and the Kongo. The spirits also come in “families” that all share a surname, like Ogou, or Ezili, or Azaka or Gede. For instance, “Ezili” is a family, Ezili Danto and Ezili Freda are two individual spirits in that family. In Vodou, spirits are divided according to their nature in roughly two categories, whether they are hot or cool. Cool spirits fall under the Rada category, and hot spirits fall under the Petwo category. Rada spirits are familial and mostly come from Africa, Petwo spirits are mostly native to Haiti and are more demanding and require more attention to detail than the Rada, but both can be dangerous if angry or upset. Neither is “good” or “evil” in relation to the other. Everyone has spirits, and each person has a special relationship with one particular spirit who is said to “own their head”, however each person may have many lwa, and the one that owns their head, or the “met tet”, may or may not be the most active spirit in a person’s life. The lwa are all said to live in a city beneath the sea called Ile Ife or Vilokan. Except for Agwe and his escort, who live in a different city below the waters. Pantheon in Haitian Vodou All of the lwa of Haiti are initiated manbos and houngans. Many are also Masons. Some of the more important spirits are as follows. RADA Pantheon in Haitian Vodou Papa Legba Atibon – He is imaged as an old man, St. Lazarus is used to represent him in the hounfo or temple. He opens the gate to the spirits, and translates between human languages and the languages of the spirits. Marasa Dosu Dosa – They are twin children, either in twos or threes. Imaged with Sts. Cosmas and Damien, or the Three Virtues. Papa Loko Atisou and Manbo Ayizan Velekete – The prototypical priest and priestess of the tradition. They confer the office of priesthood in initiation. Danbala Wedo and Ayida Wedo – The white snake and the rainbow, together they are the oldest living beings. Danbala brings people into the Vodou. St. Patrick and Moses are used for Danbala. Ogou Feray – He is a fierce general who works hard for his children but can be moody and sullen at times as well. Ogou Badagri – He is a diplomat, and is Ogou Feray’s chief rival. Ezili Freda – She is a mature light-skinned woman who enjoys the finest things, jewelry, expensive perfume, champagne etc. She is said to own all men (or she thinks she does) and can be very jealous. She gives romance and luxury. She is so pure she must never touch the bare ground. Her main rival is her sister Ezili Dantor. Agwe Tawoyo – He rules the sea and those who have crossed the ocean, and is symbolized by his boat named “Imammou”. St. Ulrich is his saint counterpart. PETWO (Petro) Pantheon in Haitian Vodou Gran Bwa Ile – His name means “Great Wood”. He is a spirit of wilderness. He is fierce and unpredictable, and a section of the grounds of a Vodou temple is always left wild for him. St. Sebastian is used to represent Gran Bwa. Ezili Dantor – a Petwo lwa, she is a strong black single mother. She does not speak, but makes a “kay kay kay” sound in possession. She is nurturing and protective but is dangerous when aroused, even to her own children. Her image is the Mater Salvatoris of Czestokowa. She often uses a dagger or bayonet, and her colors are often red and dark blue. A little known fact is that she is actually a hermaphrodite, and takes both men and women in marriage. Ti Jan Petwo – the son and lover of Ezili Dantor. Simbi – the Simbi lwa live in fresh water rivers and are knowledgeable in the areas of magic and sorcery. The Bawons – they rule the cemetary and the grave. There are three – La Kwa, Samdi, and Simitye. The Gedeh – The Gedeh spirits are all dead spirits who rule death and humor and fertility. They drink rum steeped with 21 habanero peppers and bathe their faces and genitals with this mixture also, to prove that they are who they say they are. They are sung for last at a party for the spirits. Chief of the Gedeh is Gedeh Nibo, with his wife Maman Brijit. St. Gerard represents the Gedeh. Role of Clergy in Haitian Vodou In serving the spirits, the Vodouisant seeks to achieve harmony with their own individual nature and the world around them, manifested as personal power and resourcefulness in dealing with life. Part of this harmony is membership in and maintaining relationships within the context of family and community. A Vodou house or society is organized on the metaphor of an extended family, and initiates are the “children” of their initiators, with the sense of hierarchy and mutual obligation that implies. Most Vodouisants are not initiated, referred to as being “bosal”; it is not a requirement to be an initiate in order to serve one’s spirits. There are clergy in Vodou whose responsibility it is to preserve the rituals and songs and maintain the relationship between the spirits and the community as a whole (though some of this is the responsibility of the whole community as well). They are entrusted with leading the service of all of the spirits of their lineage. Priests are referred to as “houngans” and priestesses as “manbos”. Below the houngans and manbos are the hounsis, who are initiates who act as assistants during ceremonies and who are dedicated to their own personal mysteries. One doesn’t serve just any lwa but only the ones they “have”, which is a matter of one’s individual nature and destiny, and sometimes a matter of which spirits one has met and who take a liking to oneself. Since the spirits are individuals, they respond best to those whom they know or have been personally introduced to. Which spirits a person has may be revealed at a ceremony, in a reading, or in dreams. However anyone may and should serve their own blood ancestors. That said, there are a few spirits or groups of spirits that have a particular relationship with humankind such that, it is not unreasonable to say, anyone might approach them with some confidence if a few basic forms and preferences are known, among these being Papa Legba Atibon, the gatekeeper of the spirits, Danbala Wedo, who is said to own all heads and is the oldest ancestor of all life, and Papa Gedeh, who gives voice to the spirits of the dead, and everyone has Dead. I leave it to the reader to investigate the identities of these spirits further from other sources such as the Vodouspirit Yahoo! forum. Also the Catholic saints are all very approachable to anyone who asks for their help, such as St. Anthony or St. Michael. Standards of Conduct in Haitian Vodou The cultural values that Vodou embraces center around ideas of honor and respect – to God, to the spirits, to the family and sosyete, and to oneself. There is a plural idea of proper and improper, in the sense that what is appropriate to someone with a Danbala as their head may be different from someone with an Ogou as their head, for example — one spirit is very cool and the other one is very hot. I would say that coolness overall is valued, and so is the ability and inclination to protect oneself and one’s own if necessary. Love and support within the family of the Vodou sosyete seems to be the most important consideration. Generosity in giving to the community and to the poor is also an important value. Our blessings come to us through our community and we should be willing to give back to it in turn. Since Vodou has such a community orientation, there are no “solitaries” in Vodou, only people separated geographically from their elders and house. It is not a “do it yourself” religion – a person without a relationship of some kind with elders will not be practicing Vodou. You can’t pick the fruit if you don’t start with a root. The Haitian Vodou religion is an ecstatic rather than a fertility-based tradition, and does not discriminate against gay people or other queer people in any way. Unlike in some Wiccan traditions, sexual orientation or gender identity and expression of a practitioner is of no concern in a ritual setting, it is just the way God made a person. The spirits help each person to simply be the person that they are. Way of Worship in Haitian Vodou After a day or two of preparation setting up altars, ritually preparing and cooking fowl and other foods, etc., a Haitian Vodou service begins with a series of Catholic prayers and songs in French, then a litany in Kreyol and African “langaj” that goes through all the European and African saints and lwa honored by the house, and then a series of verses for all the main spirits of the house. This is called the “Priye Gineh” or the African Prayer. After more introductory songs then the songs for all the individual spirits are sung. As the songs are sung spirits will come to visit those present by taking possession of individuals and speaking and acting through them. Each spirit is saluted and greeted by the initiates present and will give readings, advice and cures to those who approach them for help. Many hours later in the wee hours of the morning, the last song is sung, guests leave, and all the exhausted hounsis and houngans and manbos can go to sleep. On the individual’s household level, a Vodouisant or “sevite”/”serviteur” may have one or more tables set out for their ancestors and the spirit or spirits that they serve with pictures or statues of the spirits, perfumes, foods, and other things favored by their spirits. The most basic set up is just a white candle and a clear glass of water and perhaps flowers. On a particular spirit’s day, one lights a candle and says an Our Father and Hail Mary, salutes Papa Legba and asks him to open the gate, and then one salutes and speaks to the particular spirit like an elder family member. Ancestors are approached directly, without the mediating of Papa Legba, since they are in one’s blood. If a person feels like they are being “called” or approached by the spirits of Haiti, the first thing a person should begin to do is to serve their ancestors, perhaps beginning with an ancestor novena (see the links below). Monday is the day of the ancestors in our house, but ideally one speaks to their ancestors daily. If you do not honor your ancestors first, they may get upset and stand between you and other spirits. The second thing is to seek out a competent and trustworthy manbo or houngan for a reading or consultation. It may take some time of prayer, patience and effort to find a suitable person. Travel may even be necessary. They can help determine what spirit(s) if any may be involved and what if anything might need be done. Expect to pay some sort of fee for their time – unlike many Neo-Pagan traditions, in Haitian Vodou “manbo e houngan travay pa pou youn gwan mesi” (“The manbo and the houngan don’t work for a big thank you”) (3). This is true of other African-based traditions as well. Role of Initiation into Haitian Vodou Initiation in Haitian Vodou is a serious matter, and it is advised to not run off to Haiti with the first person you encounter, on the internet or elsewhere, sight unseen or otherwise, who says they will initiate you. Take the time to get to know your prospective Maman or Papa in the Vodou, and the members of their society. Attend ceremonies in person, ask questions, learn, check references. Serve your ancestors, cultivate patience, and wait. Pay attention to dreams or other messages from the spirits. For most people initiation is totally unnecessary. It may be advised to research (as you would anyone else!) and weigh carefully, but perhaps not necessarily discount out of hand, anyone actively promoting initiation into the Haitian Vodou priesthood with marketing slogans and New Age buzzwords. Haitian Vodou does not proselytize and it is not for sale although even valid initiations do cost some money, due to the time, people, materials and travel involved. If you think of the time and care it takes to make the best choice when you invest in a car or a home, or to hire a babysitter for the kids, how much more important are one’s concerns of the Spirit? At the end of the day, reputations and rumors are less important than an honest answer to one question however: “Will I be happy and satisfied having this person/these people in my life? Is this a community where I can learn and grow in a positive way?” Only the seeker can answer that question for themselves, with God’s help. And the help of the Advanced Bonewits Cult Danger Evaluation Frame (see the links below). Also there are other options besides initiation in Haitian Vodou to become closer to the spirits. While the concept of initiation gets a lot of airplay among outsiders, far more common among the Haitian community is the “maryaj mistik”, or the mystical marriage, in which the Vodouisant literally marries one or more lwa, in a ceremony complete with bridal dresses, rings, cakes, and a priest. In return they gain special protection and favor from the spiritual spouse. This is generally in exchange for one day of sexual abstinence per week in which the human spouse receives the spirit in their dreams, and any other terms spelled out in the marriage contract. Initiation for its part creates a reciprocal bond between initiator and the new initiate with obligations every bit as serious as marriage, deeper even since it cannot be undone. Initiator and initiate become family with all the joys and burdens that may entail. It also entails certain promises, responsibilities and commitments with regard to the spirits. With persistence and patience, the spirits will lead a person to the house and elders that are right for them. Vodou is not a race, so every seeker can well afford to take their time. Personal relationships are the very foundation of Vodou and there is no substitute for the time it takes to cultivate them. I knew my houngan for three years prior to my own sevis lave tet (“washing of the head”). We were friends long before I had any interest in or notion of any connection to Haitian Vodou that I might have. Some of my god-brothers waited longer than that. This is how it should be. In Haiti these would all be people you grew up with and you would just know who is who or would know someone who knew someone. In the United States, those of us who are non-Haitian have a few more obstacles to overcome, but by the grace of God and the spirits they are not insurmountable. Regleman Gineh Initiate or not, once you belong to a house and have chosen an elder, it is important to follow the guidance they provide as to the way things are done in their house, called the “Regleman Gineh”. There is a diversity of practice in Vodou across the country of Haiti and the diaspora, for instance in the north of Haiti the sevis tet or kanzwe may be the only initiation (according to my elders from Haiti in three different houses) as it frequently is in Cuba and the Dominican Republic, whereas in Port Au Prince and the south they practice the kanzo rites with three grades of initiation — senp, si pwen, and asogwe — and the latter is the most familiar mode of practice outside of Haiti. Some lineages combine both, as Manbo Katherine Dunham reports from her personal experience in her book “Island Possessed.” Kay Aboudja, my own house, is one of these lineages. Although the general structure of ritual and practice are the same across Haiti, small details of service and the spirits served will vary from house to house, and information in books or on the internet may be contradictory. When in doubt, etiquette dictates that one consult their own Maman or Papa in the Vodou, and practice as they direct according to the regleman of their lineage, since “every manbo and houngan is the head of their own house”, as a common saying in Haiti taught to me by Houngan Aboudja states. While the overall tendency in Haitian Vodou is very conservative in accord with its African roots, there is no singular, definitive, One And Only True Right And Only Haitian Vodou ™, only what is right in a particular house or lineage. In other words, if you read something on a web page or a book, and it contradicts what your manbo or houngan says to do, go with what they say. This may seem restrictive on the surface from a solitary Neo-Pagan perspective, but since you have done your homework and taken the time to build a positive relationship of trust with your elder(s) ahead of time, this will not be the case in practice. A good parallel is the way everyone practices the same way in a Wiccan coven context. Ultimately everything comes from the spirits and the ancestors however. It is not a matter of personal preferences as it often may be in popular Witchcraft or other pagan traditions, and this reality becomes clearer with experience in the Sevis Gineh. This is the most basic overview of the Haitian Vodou religion imaginable; keeping in mind that I am by no means an expert compared to my elders after only a couple of years in the religion as an hounsi, I hope it gives some general idea and understanding of what Haitian Vodou is about, since it summarizes what I have learned from my own elders in a very condensed form. The most important thing I have learned from my elders however is this: Black, red, yellow or white, a person can find beauty and fulfillment serving the spirits in the Haitian religion – the Vodou is not a religion limited by race or ethnicity since ultimately, as science has proven, we are ALL the Children of Africa, and the waters of Gineh join us all

148 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Bon fet Mèt Agwe Tawoyo!

Gerard Valcin

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

From Haitian Vodou article on Wikipedia

“Haitian Vodouisants believe, in accordance with widespread African tradition, that there is one God who is the creator of all, referred to as "Bondyè" (from the French "Bon Dieu" or "Good God", distinguished from the god of the whites in a dramatic speech by the houngan Boukman at Bwa Kayiman, but is often considered the same God the Roman Catholic Church talks about). Bondyè is distant from his/her/its creation though, and so it is the spirits or the "mysteries", "saints", or "angels" that the Vodouisant turns to for help, as well as to the ancestors. The Vodouisant worships God, and serves the spirits, who are treated with honor and respect as elder members of a household might be. There are said to be twenty-one nations or "nanchons" of spirits, also sometimes called "lwa-yo". Some of the more important nations of lwa are the Rada, the Nago, and the Kongo. The spirits also come in "families" that all share a surname, like Ogou, or Ezili, or Azaka or Ghede. For instance, "Ezili" is a family, Ezili Dantor and Ezili Freda are two individual spirits in that family. The Ogou family are soldiers, the Ezili govern the feminine spheres of life, the Azaka govern agriculture, the Ghede govern the sphere of death and fertility. In Dominican Vodou, there is also an Agua Dulce or "Sweet Waters" family, which encompasses all Amerindian spirits. There are literally hundreds of lwa. Well known individual lwa include Danbala Wedo, Papa Legba Atibon, and Agwe Tawoyo.

In Haitian Vodou, spirits are divided according to their nature in roughly two categories, whether they are hot or cool. Cool spirits fall under the Rada category, and hot spirits fall under the Petwo category. Rada spirits are familial and mostly come from Africa, Petwo spirits are mostly native to Haiti and are more demanding and require more attention to detail than the Rada, but both can be dangerous if angry or upset. Neither is "good" or "evil" in relation to the other.

Everyone is said to have spirits, and each person is considered to have a special relationship with one particular spirit who is said to "own their head", however each person may have many lwa, and the one that owns their head, or the "met tet", may or may not be the most active spirit in a person's life in Haitian belief.

In serving the spirits, the Vodouisant seeks to achieve harmony with their own individual nature and the world around them, manifested as personal power and resourcefulness in dealing with life. Part of this harmony is membership in and maintaining relationships within the context of family and community. A Vodou house or society is organized on the metaphor of an extended family, and initiates are the "children" of their initiators, with the sense of hierarchy and mutual obligation that implies.

Most Vodouisants are not initiated, referred to as being "bosal"; it is not a requirement to be an initiate in order to serve one's spirits. There are clergy in Haitian Vodou whose responsibility it is to preserve the rituals and songs and maintain the relationship between the spirits and the community as a whole (though some of this is the responsibility of the whole community as well). They are entrusted with leading the service of all of the spirits of their lineage. Priests are referred to as "Houngans" and priestesses as "Manbos". Below the houngans and manbos are the hounsis, who are initiates who act as assistants during ceremonies and who are dedicated to their own personal mysteries. One doesn't serve just any lwa but only the ones they "have" according to one's destiny or nature. Which spirits a person "has" may be revealed at a ceremony, in a reading, or in dreams. However all Vodouisants also serve the spirits of their own blood ancestors, and this important aspect of Vodou practice is often glossed over or minimized in importance by commentators who do not understand the significance of it. The ancestor cult is in fact the basis of Vodou religion, and many lwa like Agasou (formerly a king of Dahomey) for example are in fact ancestors who are said to have been raised up to divinity.”

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

On other social media you find interesting and beautiful stuff this is one of the them. I do not know who the artist is.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Today, I went and saw my husband and my mother. LaSiren has been on my mind for days, and, after dreaming with her and waking up with her songs in my mouth this week, it was time to go see her. Mèt Agwe gets the first Sunday of each month from me as well, and I try to do something special for him then. So, kismet.

The beach was FREEZING and there was plenty of snow on the ground, but it made me giddy to go. When I got there, a few people were walking the shore but they evaporated. It was just me, Agwe and LaSiren, and the seagulls, who watched me carefully and closely, maybe to bring back messages to Imammou and my husband's ears.

The sea was gray--we are expecting a lot of snow tonight--but the water came up to kiss the flowers and fruit as I set them out and prayed, and the sea drank deeply of the fresh water and champagne poured for the benefit of love.

#vodou#haitian vodou#vodou culture#vodun#vodoun#voodoo#agwe#agwe tawoyo#mèt agwe#lasiren#lasirene#La Siren#real shit gets real blessings#lwa

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

While something popularly written about and, in very few cases enshrined as an almost pop culture reference in some pieces of the Haitian Vodoy community, the theory/rumor the Gran Brigit/Manman Brigit is related to or derived from or really is St Brigid falls from one source that is widely known as deeply problematic and outright fraudulent, and likely made it up as both a religious Mary Sue and a way to draw in folks curious about Vodou who were coming from neopaganism.

There is no history of Irish indentured servants on the island of Hispaniola, at all. The island was colonized by the French and Spanish, back and forth, with some sideline American action in there. The British monarchy was the colonial power dealing in Irish indentured servants, and they had no foothold on Hispaniola. The historical trope of Irish indentured servants gets brought up a lot, likely as a mechanism of trying to create an equality of suffering that historically did not exist. The colonial powers on the island had no need of indentured servants that would have had to be granted land, be paid, and treated reasonably well. They had plenty of enslaved Africans to do all that work for nothing.

Similarly, Gran Brigit is not presented as white. The lwa who embody death, such as Brigit and her husband Bawon Samdi, can often appear pale because they are dead, but they are not white. Some spirits do portray themselves as white or white-passing for many reasons, with many of them being some of the most well-known spirits in the religion; Damballah Wedo, Agwe Tawoyo, Ezili Freda, Ogou Sen Jak, and others. Lwa who often appear with very light or white skin are often lwa who are considered to be or descend from royalty, are largely 'cool', who are concerned with cleanliness and purity. Brigit does not really fit that mold.

Brigit also does not dance or do much of anything in possession. As she is the embodiment of death when she arrives in her chwal, she is laid out as death is; she lays still on the ground wrapped in a shroud with her jaw tied closed, cotton placed in her nostrils, and occasionally her face powdered to give the pallor of death. The family of Gede are the elevated dead who dance; the banda is theirs, as is piman (peppered rum...we joke that it is Haitian tear gas, but it is called piman) and they are who engage in lascivious behavior. Brigit (who prefers sweet drinks) and the family of spirits called Bawon are dead serious (literally). They are the implacability of death, the dug grave, the finality that we all face.

'Tis the season to check your sources on death and the dead in Haitian Vodou!

Maman Brigitte is the only white spirit of the Vodou Lwa. From a folklore perspective she became a part of Vodou through indentured Irish women sharing their stories of St. Brigid who is a very obvious christianization of the Celtic goddess Brigid.

From a metaphysical perspective the goddess Brigid continued to be worshiped as St. Brigid. She then immigrated with the Irish to Haiti & the US. She married Baron Samedi, the chief Lwa of death.

For me as a person of predominantly Celtic decent steeped in the black community I’m very drawn to Maman. Learning more about Maman is helping to learn more about myself, my heritage, & where my place is in the scheme of things.

#vodou#haitan vodou#real vodou#gran brigit#manman brigitte#gede#ghede#fet ghede#fet gede#voodoo#new orleans voodoo

198 notes

·

View notes

Text

Andre Pierre

7 notes

·

View notes

Link

Agwe weeps.

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Met Agwe Tawoyo greets and washes one of the new children of the house during his fete on the beach. Fet Agwe 2017, Kay Manbo Maude/Sosyete Nago nan Jacmel.

9 notes

·

View notes