#alexander hamilton x john hancock

Text

The old intro was shit, so I'm updating it ^_^

Name?—Rayne

Age?—4teen

Birthday?—25/11

Siblings?—none

Pronouns?—He/Him/They/Them

Gender?—Non-binary

Sexuality?—aroace (aromantic and asexual)

Socials—

- Tiktoks: no1edwardrutledgehater (Rayne 📜🪶) and r4yne.c0s (Rayne|📜🪶|🆓️🇵🇸)

- Instagram: no1teamgalacticstan (Rayne 📜🪶)

- Twitter (x): helplifeismess (Stephen Hopkins 🍉)

- Bluesky: helplifeismess.bsky.social (Rayne (TEAM PAST 🩷💚))

Hobbies—

- Cosplaying

- Drawing

- Reading

Interests—

- History (more specifically Mr and Mrs Madison, the Adams family, King George III of Great Britain and Ireland, the Second Continental Congress, just the Georgian era overall)

- Musicals (1776, and Hamilton)

- Games (Splatoon, Pokémon (Pokémon Masters, Black, White, Black2, White2, Scarlet, Violet, Sword, Shield, Legends Arceus, Diamond, Pearl, Brilliant Diamond, and Shining Pearl), hsr, r:1999)

- Shows (Doctor Who, Ghosts (UK), Horrible Histories, The Owl House, Liberty's Kids, and Amphibia)

Favourite characters—

- 1776: John Adams, Abigail Adams, John Hancock, Stephen Hopkins, Richard Henry Lee, Benjamin Franklin, Leather Apron, and John Dickinson

- Hamilton: James Madison, and King George III

- Splatoon: Callie, Pearl, Marina, Big Man, Judd, and Lil Judd

- Pokémon: Colress, Arezu, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, Cyrus, and Mimikyu

- The Owl House: Lilith and Kikimora

- Amphibia: Marcy and Darcy

- Honkai Star Rail: March 7

- Doctor Who: 8th, 13th, and 15th Doctors, the Master (all), Ruby Sunday, Donna Noble, Jackie Tyler, and Rogue

- Reverse:1999: Mr. APPLe, Regulus, Winnifred, Eagle, Schneider, and зима (Winter)

Neutral characters (love and hate them)—

- 1776: Thomas Jefferson

- Pokémon: N

- Honkai Star Rail: Dr Ratio

Hated characters (mods crush their skulls)—

- 1776: Edward Rutledge

- The Owl House: Hunter (I have no excuse other than that I can't stand him)

- Hamilton: Alexander Hamilton (again, I just can't stand him)

Favourite music artists—

- Mitski (🤩🤩🤩)

- Ado

- Queen

- Mother Mother

- The Northern Boys

- They Might Be Giants

Kin list—

- 1776: John Adams, John Hancock, and James Wilson

- The Owl House: Lilith and Kikimora

More will be added later ^_^

#1776 musical#1776 movie#1776#hamilton#hamilton musical#artists on tumblr#james madison#benjamin franklin#john adams#alexander hamilton#thomas jefferson#abigail adams#john hancock#john dickinson

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

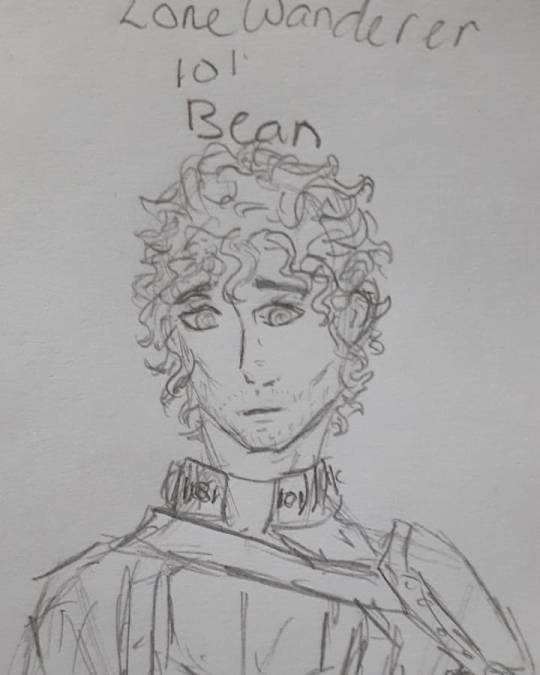

Here's my main 4 fallout charcaters since I've done a re draw of them so I hope you enjoy

~~~~~~

Tibyan Coven

Bean the lone wanderer

Game: fallout 3, but makes an appearance in both NV and 4

Age: 19, 23 and 29

Alliance: brotherhood of steel before once again becoming the lone wanderer.

Sexuality: Gay

Romance: Charon

weapon of choice: is Anti-materiel rifle

Quick history: Bean had a lot of medical skill due to his father teaching him. Due to his father leaving the vault he decided he needed to find him, he meets charon while in the underworld and in turn pays 2000 caps for his contract to free him. All tho it doesnt all go according to plan. along the way he find himself in the company of his childhood bully, a dog he saved from raiders and a 200 year old ghoul who he gains feeling for.

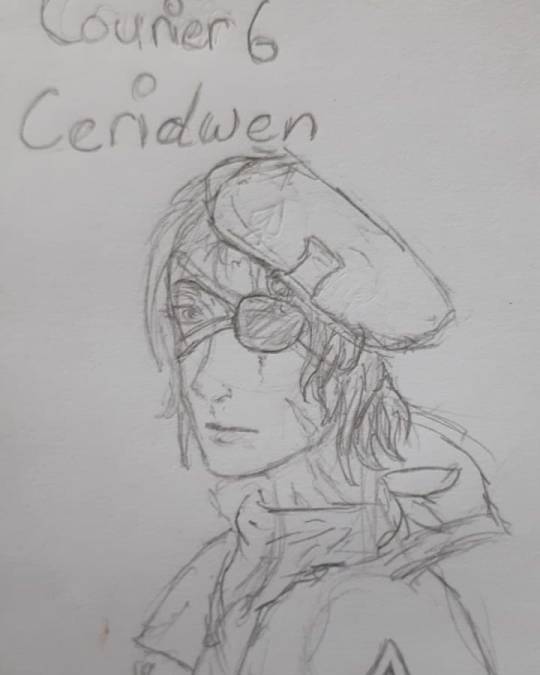

Ceridwen Doks

Courier Six

Game: fallout New Vegas, makes an appearance in fallout 4

Age: 26, 32

Alliance: NCR turned wild card

Sexuality: pansexual

Romance: Craig Boone, Joshua Graham

Wrapon of choice: ak 47, mine's and bombs

Quick history: six after taking a bullet to the head is now on a revenge mission for the man who has taken everything from them. Six meets Boone along the way and gains a close bond with him until the legion kill the sniper. After this event Six is left with a heavy heart and revenge that has left them hollow, Six eventually goes with the happy trials caravan when they meet Joshua, Six forms a bond with him.

Tika Watson

Sole survivor

Game: fallout 4

Age: 30, 240

Sexuality: Bisexual

Alliance: Rail road/ minutemen

Romance: Nate Watson, Nick Valentine

Weapon of choice: shot gun, pistols and plasma rifle.

Quick history: Tika is celebrity akin to Marilyn Monroe, she has played in Grognak the Barbarian,the silver shroud and is the original face of Nuka cola. From audio plays, movies and adds for company's she eventually has time off from the big screen to have her son.

After the bombs hit she loses everything and the only thing she is striving for is to find her son and get revenge on the man who killed her husband. Tika meets Nick by accident while snooping around abandoned vaults with dogmeat, Nick Valentine become a permanent residency in her life as she becomes his partner in helping stop crime and he helps her find her son, both of them pass around jokes and references that only each other get.

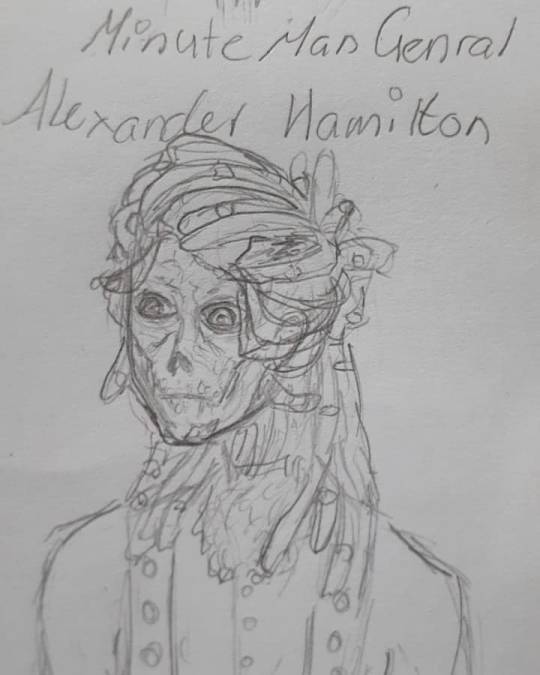

Alexander Hamilton

General of the Minutemen

Game:fallout 4 but has an appearance in fallout 3.

Age: 33, 43

Sexuality: pansexual

Alliance: Minutemen

Romance: John hancock

Weapon of choice: laser Weapons of all kinds

Quick history: Alexander is first seen in fallout 3 when he was still human he is trying to make his way from Megaton to Diamond City. He had a quick convosation with the lone wanderer before he isn't seen until 10 years later. In fallout 4 he has transformed into a glowing Ghoul after getting lost at the glowing sea. When the sole survivor meets him, Alexander has found his way to Nuka cola world where he mornes the death of Oswald. He goes with Tika back to Sanctuary where he helps around as much as possible before being appointed General of the Minutemen by both Tika and Preston. This is how he eventually ends up meeting hancock.

#fallout#fallout 4#Fallout 3#falloutnewvegas#fallout sole survivor#fallout lone wanderer#fallout nick valentine#nick valentine#fallout charon#joshua graham#courier 6#alexander hamilton x john hancock#ocs#fallout new vegas

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

What’s in a name?

Over the past 393 years, Daniel has gone by a good handful of names. The one constant that has stuck from the time he was first named at 8 days old until this very day has been his first name: Daniel.

This name comes from the Hebrew name דָּנִיֵּאל (Daniyyel) meaning "G-d is my judge". Unlike some Personifications who had the chance to choose their own name upon reaching the point of conciousness or sentience, his was given to him by his mother and from it he has taken the advice it gives over his life. There is an odd comfort in that constant reminder that regardless of what people think of him on Earth, there really is only one Being to whom he will have to eventually answer. Because of its meaning’s significance, he has never felt the need to change it as he has of his middle and surnames.

Until he was adopted into the colonyship of England, Daniel bore a Dutch surname: Koenig, which simply meant king in that language. The true source of that surname is unknown to Daniel, and he never really got a chance to ask his parents, as his father died a month prior to his being born, and his mother passed away when he was still a small child. The name Koenig was later given to his wife, Anna Wilbore, and for a time after her death in 1641 Daniel considered keeping her surname in lieu of the one his mother passed to him, but that consideration was done for him in 1665 when he for the first time stepped foot in England into the court of King Charles II. Due to the lack of resistance against English acquisition of the New Netherland colonial territories, and Daniel’s own expresséd pleasure of being free of the Dutch rule, he was granted royal favour and adopted into the king’s own family as a member of English governance. Legally, he was to be considered an illegitimate son of the king, and thus was given the surname Fitzroy, and by his own choice took on Charles as a middle name.

Daniel Charles Fitzroy stuck as his name for quite a long time, and did not change again until January 14, 1784 during the ratification of the Treaty of Paris which saw the formal ending of the American War for Independence. Shortly after the signing, Daniel gave a speech to those present, which included key figures such as George Washington, John Hancock, Alexander Hamilton, Thomas Jefferson, etc. The conclusion of said speech included an affirmation of his intent to uphold the right of the newly independent United States, would not take an active role in any further loyalist movements, would cede submission to the joined voices of Congress, the President, and Judiciary offices, and to prove his commitment to this pledge of allegiance, chose to take on a new name, shedding the most visible relic of his ties to England.

Charles was traded for Aleksander, both to give honour to one of the political minds that Daniel found himself agreeing with more often than most others among the nation’s Founding Fathers, Alexander Hamilton, and to give a small nod to the Dutch blood that ran in him, thus favouring the ks- infix over the more modern x- spelling of the name. Fitzroy was exchanged for Hill, a common surname, a simple name that did not assume any major role in society - no claiming of rank or occupation, yet added a second reminder to the scar on Daniel’s cheek of the personal significant of the Battle of Bunker Hill.

Daniel Aleksander Hill stood as his name for more than a century thereafter until the Spanish-American War’s end result saw America now in possession of colonies - Guam, Puerto Rico, the Virgin Islands, and several minor island holdings wrested from Spanish grasp. This, along with the past century in gaining confidence as a Nation, strides in domestic and international solidification of America as a powerhouse of diplomatic relations and economic significance which would be proven double over in the coming decades, cemented the United States of America into the technical definition of an Empire, which Daniel saw fit to pay some homage to that and adjust his name yet again, affirm that he was a powerful player on the world stage.

Surely one deserving to call himself King.

#headcanon#about dan#turns out making yourself sit down and fuckin WRITE gets the muse flowing#who would have thought#anyway its about damn time i actually wrote this one out#im proud of dans name damn it

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

The 230th Anniversary of the Ratification of the Constitution

Post by Sebastian van Bastelaer, ConSource Research Fellow

On June 21, 1788, New Hampshire became the ninth state to ratify the United States Constitution, reaching the threshold for activation of the new government laid out in Article VII. Four more states signed on in the following two years, completing the union of the original thirteen colonies. Each state had different considerations and motivations to take into account, and some conventions were fiercely contested, but in the end the pro-ratification forces known as Federalists triumphed, cohering to lay the groundwork for the nation we know today.

Delaware became the first state to sign on to the pact on December 7, 1787. Despite internal tensions in the state dating back to the American Revolution, all 30 delegates immediately voted for ratification—in fact, the deliberations might have taken only a few hours. The representatives were concerned with economic issues stemming from high duties paid to import goods from Pennsylvania and eager to establish more stable footing under the new Constitution, making the decision an easy one. Delawareans have been proud to call themselves “The First State” ever since.[i]

Pennsylvania ratified the Constitution on December 12, a mere five days after their neighbors to the south had done the same. As was the case in many states, antipathy towards the new set of laws was strongest in rural counties, while the coastal cities were a Federalist stronghold. The ratifying convention, held over the span of three weeks in Philadelphia, was far more bitterly fought than those in the other states that ratified in the winter of 1787-1788. Unlike at the national meeting several months prior, the Pennsylvania ratification convention was open to the public, allowing for many pro-Constitution citizens to sit in the gallery and heckle opponents, which may have impacted the vote. To many, this reaffirmed the state’s reputation for being perhaps too democratic—in the words of physician Benjamin Rush, politics in the state were run by a “mob government”.[ii] After a series of drawn-out debates, the convention voted to ratify the Constitution by a final tally of 46-23.[iii]

New Jersey was next to join the new government after meeting for ten days at the Blazing Star Tavern in Trenton in December 1787. Like their counterparts in Delaware, the representatives were concerned with the economic wellbeing of their state under the Articles of Confederation. Traders in New Jersey had to pay duties for goods imported from both Pennsylvania and New York, and a large number of public debt holders lived in the state. These factors made it appealing to establish a stronger central government that had the power to tax and establish solid credit. As a result, the delegates swiftly acceded to the compact by a 38-0 margin on December 18.[iv]

Georgia was the first southern state to ratify, doing so on December 31st by a 26-0 vote after only one day of discussion. The state had had an unreliable attendance record in previous congresses, and had rarely contributed adequate resources to the central government, but the promises of a strong unified nation were desirable for several reasons. Attendees were satisfied with the compromises made at the Constitutional Convention, which had helped to sustain the institution of slavery. Furthermore, the threat of incursions by Creek Indians on Georgian settlers made the idea of a stronger national military and provisions for the common defense an appealing concept.[v]

Connecticut expected a more divisive convention when its representatives met just after New Year’s Day 1788. In fact, the state had at first elected not to send any delegates to Philadelphia the previous summer, reflecting the antipathy that many of its citizens felt toward altering the Articles of Confederation. Furthermore, rancorous internal divisions between wealthy merchants and agrarians persisted. In the end, however, ratification passed by a wide margin on January 9—though some observers argued that the stifling of Anti-Federalist voices in the press prior to the convention tipped the scales.[vi]

Massachusetts, a hotbed for patriotic fervor during the Revolution, held a particularly contentious meeting in Boston that lasted nearly a month from January 9 to February 7, 1788. The state had recently witnessed the regulation movement known as Shays’ Rebellion from 1786-1887, which had been a reaffirmation to many of the necessity of reforming and strengthening the national government. Yet staunch opposition to the Constitution came as a result of the document’s lack of an explicit bill of rights, as well as the perceived surrender by anti-slavery forces in Philadelphia. Numerous famous patriots numbered among the delegates. Samuel Adams argued in favor of ratification, while his cousin John offered his support for the new system from across the Atlantic. John Hancock endorsed the ratification and recommended a bill of rights be attached. This support made the key difference, and Federalist forces triumphed by a final tally of 187-168.[vii]

Maryland followed suit in late April 1888, becoming the seventh state to ratify in a 63-11 vote at the State House in Annapolis. Representatives from the eastern shore and large cities such as Annapolis and Baltimore proper favored joining the new union due to their interest in promoting widespread regional and interregional economic activity. Baltimore County and Anne Arundel County were strongly against ratification. At the convention, future member of the Supreme Court Samuel Chase was an Anti-Federalist and debated against Daniel Carroll, one of only two Catholics to have signed the Constitution.[viii]

Three weeks later, the South Carolina convention met in Charleston and signed on by a margin of over 2 to 1 while also submitting several recommended amendments to be considered. As had happened in Georgia, delegates approved of the Constitution’s compromises on slavery, an issue that delegate John Rutledge had warned in 1787 would determine “whether the Southn. States shall or shall not be parties to the Union.”[ix] Some people complained that a disproportionate number of representatives had been assigned to coastal areas such as Charleston, which were more vociferously in favor of ratification. This convention would be the last one to be lightly contested; Anti-Federalists in the last five states had much stronger and better organized support.[x]

New Hampshire had convened in February, but disdain for the implicit acceptance of slavery and concerns over non-Protestants serving in government were enough to scuttle the first attempt at ratification. Though there was no vote specifically rejecting the Constitution, there was enough resistance to convince representatives to adjourn. Not until June was another convention held, when eight other states had already ratified. On June 21, a determining vote finally took place, with 57 in favor of joining against 47 opposed.[xi]

The victory for Federalists in New Hampshire gave new life to struggling pro-ratification forces in other states, who had to face the specter of disunion and strife with neighbors as well as within their own borders. These fears had a tangible impact on other conventions, starting with Virginia, which met from June 2-27, 1788. The debates featured Federalists James Madison and John Marshall battling George Mason and Patrick Henry. Future President James Monroe was also present. Virginia’s geographic divisions were very similar to Maryland’s: counties on the shores of the Chesapeake, as well as those containing larger cities, favored union, while the more rural Piedmont region opposed it. Despite the best efforts of Henry, the news of New Hampshire’s vote and the rhetorical skill of Madison helped ensure a narrow victory for ratification.[xii]

The New York convention, held from June 17-July 26, also featured hotly contested arguments between preeminent political figures. With the support of longtime populist governor (and future Vice President) George Clinton, Anti-Federalists Melancton Smith and John Lansing forcefully argued on behalf of their constituents to stay out of the union. Their opposition, led by Alexander Hamilton and John Jay, were well prepared for the debate, however, as both men had been principal authors in the widely read The Federalist essays. The news of New Hampshire’s ratification, and the possibility of New York City seceding from the state to join the union, bolstered the Federalist cause and convinced Smith to switch sides and endorse the new government, which helped effect a 30-27 vote.[xiii]

North Carolina, like New Hampshire, held two conventions, with the first in July 1788 failing to produce a consensus. The second didn’t take place until November 1789, seven months after George Washington had been inaugurated. The demonstrable success of the new nation was enough to finally convince representatives to support the pact.[xiv]

The last of the original thirteen states to ratify was Rhode Island, a state known for its independence and obduracy—in fact, it hadn’t even sent anyone to Philadelphia in 1787. Federalists made nearly a dozen attempts to bring about the complete reunification of the former colonies, all of which failed—one effort was voted down with over 90% of the vote. It was not until late May 1790, when the United States Congress had imposed sanctions and trade restrictions on the tiny republic, that Rhode Island ratified the Constitution, and even then by a mere two-vote margin. Only then, after three years of debate and disagreement, could the new republic continue to evolve and take its shape.[xv]

Sources:

Brooks, Robin. “Alexander Hamilton, Melancton Smith, and the Ratification of the Constitution in New York.” The William and Mary Quarterly Vol. 24, No. 3 (July 1967), pp. 339-358. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1920872?seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents

Hawke, David Freeman. Benjamin Rush: Revolutionary Gadfly. Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill, 1971.

Maggs, Gregory E. “A Concise Guide to the Records of the State Ratifying Conventions as a Source of the Original Meaning of the U.S. Constitution.” University of Illinois Law Review 457 (2009), pp. 458-496. Accessed online. https://scholarship.law.gwu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1839&context=faculty_publications

Maier, Pauline. Ratification: The People Debate the Constitution, 1787-1788. New York: Simon and Schuster, 2010. Ebook: https://books.google.com/books?id=-DvolFMBVRgC&printsec=frontcover&dq=ratification&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjQrJXgka7bAhWPylMKHRxeCH0Q6AEIJzAA#v=onepage&q=ratification&f=false

“Observing Constitution Day.” National Archives. Accessed online. https://www.archives.gov/education/lessons/constitution-day/ratification.html

“The States and the Ratification Process.” Madison, WI: Center for the Study of the American Constitution. Accessed online. https://archive.csac.history.wisc.edu/states_and_ratification.htm

Taylor, Alan. American Revolutions: A Continental History, 1750-1804. New York: W.W. Norton and Co., 2016.

Tunnell, James M. “Ratification of the Federal Constitution by the State of Delaware.” Dover: Public Archives Commission, 1944. Accessed online. http://www.heinonline.org.ezproxy.library.wisc.edu/HOL/Page?collection=cow&handle=hein.cow/ratfcdel0001&id=1

[i] Maggs, “A Concise Guide to the Records of the State Ratifying Conventions as a Source of the Original Meaning of the U.S. Constitution,” https://scholarship.law.gwu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1839&context=faculty_publications; Maier, Ratification, Tunnell, “Ratification of the Federal Constitution by the State of Delaware,” http://www.heinonline.org.ezproxy.library.wisc.edu/HOL/Page?collection=cow&handle=hein.cow/ratfcdel0001&id=1

[ii] Hawke, Revolutionary Gadfly, p. 197.

[iii] Maier, Ratification; Pennsylvania, Center for the American Constitution, https://archive.csac.history.wisc.edu/Pennsylvania.pdf; Taylor, American Revolutions

[iv] Maier, Ratification; New Jersey, Center for the American Constitution, https://archive.csac.history.wisc.edu/New%20Jersey.pdf

[v] Georgia, Center for the Study of the American Constitution, https://archive.csac.history.wisc.edu/Georgia.pdf; Maier, Ratification

[vi] Connecticut, Center for the Study of the American Constitution, https://archive.csac.history.wisc.edu/Connecticut.pdf

[vii] Massachusetts, Center for the Study of the American Constitution, https://archive.csac.history.wisc.edu/2.%20Massachusetts.pdf

[viii] Maryland, Center for the Study of the American Constitution, https://archive.csac.history.wisc.edu/Maryland%20essay.pdf; Maryland map, Center for the Study of the American Constitution, https://archive.csac.history.wisc.edu/Maryland.pdf

[ix] South Carolina, Center for the Study of the American Constitution, https://archive.csac.history.wisc.edu/South%20Carolina.pdf

[x] Maggs, “A Concise Guide to the Records of the State Ratifying Conventions as a Source of the Original Meaning of the U.S. Constitution”

[xi] Ibid.

[xii] Ibid.; Virginia map, Center for the Study of the American Constitution, https://archive.csac.history.wisc.edu/Virginia(1).pdf

[xiii] Brooks, “Alexander Hamilton, Melancton Smith, and the Ratification of the Constitution in New York”; Maggs, “A Concise Guide to the Records of the State Ratifying Conventions as a Source of the Original Meaning of the U.S. Constitution”

[xiv] Maggs, “A Concise Guide to the Records of the State Ratifying Conventions as a Source of the Original Meaning of the U.S. Constitution”

[xv] Ibid.; Taylor, American Revolutions

0 notes