#also just the whole trope of character whose death colors an entire narrative

Note

What movie or tv show scared you the most?

OH HEEHEEHEEEEEE MY TIME HAS COME

I think this was probably the sign I was meant to be a horror fan, because I'm gonna talk about two movies here and neither one is a standard horror film. Now, I avoided horror films like the plague, but I now realize that's because of my aversion to jumpscares and gore, which have very little to do with actual scary stuff. I feared actual horror imagery as a small child, but basically once I read Coraline it all just turned around because that book gave me nightmares but I actually WANTED those nightmares and kept going back to the book. So what are the movies I just COULD NOT contend with?

First up, I have found that a lot of people have said this one, but really and truly, fuck Chicken Run.

I was...maybe ten when I watched it. Signed up for a goofy claymation adventure. What did I get? First of all, a whole lot of bleak color palette that warned me that this was not going to be a happy story. We are then shown the stakes right away: our entire main cast lives in a dystopian prison and if they do not find a way to escape, they will die. One DOES die. This is where a lot of people say they noped out right away, but actually, the execution of the dinner chicken in the first scene was tame for me compared to what would come next.

The pie machine. It's assembled, it's talked about, and eventually our two leads fall into it in a way that is designed to be fatal. Look, there are a ton of horror tropes in this scene alone. I haven't seen it SINCE THE ONE AIRING and I can still vividly tell you a lot of this. And if I walked into a horror film and asked for this, I'd come out super satisfied, but I was not expecting horror from this. First of all, I remember vividly the shot where you're looking from Ginger's POV falling down the shaft and the divider comes up to shunt her into the "meat" line. It's incredibly claustrophobic and you just get this almost jumpscare reminder that the character through whose eyes you see is regarded as nothing more than meat to be consumed. There is then an array of blades designed for close calls, and dough that essentially glues the lead characters down to a conveyor belt so they have to helplessly watch the death machines that are coming. Sticky stuff that roots you to one spot; that's another thing that just REALLY unnerves me and I love it if I'm reading CreepyPasta but I was not reading CreepyPasta; I was watching a children's film. The leads escape certain death by jamming the gravy system, causing the machine to overload on pressure, and here I feel like I should've been relieved that they escaped but instead I was the most unsettled of all when the pressure meter started climbing. I don't know if this film *gave* me a phobia of industrial accidents or if it just awakened what was already in my OCD little brain, but suffice to say that after this movie, I was hyper-aware of my own fear of things like hissing steam, rising pressure meters, and being in a room where large metal things were clanking. (I'm since over it; I've been exposed to it in enough things.)

Now, I was no quitter. I should have just noped out. But I didn't. I continued to traumatize myself. The next part of the film until the climax I don't remember so well - it wasn't as traumatizing - EXCEPT for the part where Ginger finds and rebuilds Rocky's circus poster. And now, as an adult, I can see how that was kinda supposed to be funny, like, "The goddamn chicken padded his résumé and the way they found this out was a circus poster." But little me was invested in these chickens, I wanted them to be happy, and what I saw was basically their death notice being signed with that scrap of paper with a cannon on it. I FELT that in my bones.

STILL NOT HAVING THE GOOD SENSE TO JUST EJECT THE TAPE ALREADY, I proceeded to the climax, in which what happens to Tweedy might be one of the most fucking awful things I've seen ever? Pinned upside-down in a superheated, confined space with rising liquid from below as the pressure meter starts climbing again. And her husband arrives just in time to see her like this but not in time to actually stop the explosion. Thank God it didn't actually kill her because even though I was already traumatized, that would've absolutely made it worse.

Thing is, ever since this movie scared the absolute shit out of me - and was probably the cause of the weird stomachaches I had for A WEEK after - I've kinda had this thing about reclaiming the scary parts and stomping on them while laughing maniacally. I feel like every time I've done a crossover project, there's been a temptation to write in an arc where the mains go up against THE PIE MACHINE and fucking win. And also there's whump with tons of comfort in my version to mitigate it all. I haven't done any such thing for TBTC...YET. But I know what I must do. I know who must destroy the machine and the Tweedys along with it. Buckle your seatbelts.

My final word before I move on is that as I ascend into adulthood, I think that for the most part, a rewatch of this film wouldn't traumatize me so badly. It'd still be gross and creepy in a way I think shouldn't be sent to children without warning, but I could deal with the imagery, maybe enjoy using it as whump fuel even more, maybe my horror side would really get into the peril this time. But the one thing I've realized is that this premise is fucked EVEN MORE if you're a grown-up, because as a child, you're sympathizing with the chickens. You want them to get free of this death camp environment. But as an adult, you start to realize that all Tweedy wanted to do was be a chicken farmer who sold pie, and her supposedly nonsentient animals ganged up on her in a display of unheard-of intellect among farm stock. This would then lead to her undergoing at least one near-death fate. Think about being a farmer in our world and the animals you keep GANG UP ON YOU LIKE PEOPLE because you're killing them for food. No thank you, no THANK you.

But surely this was a one-of-a-kind phenomenon. Surely, after this...after so many other people agreed with me; "Fuck Chicken Run"...no animation studio would ever pull shit like this again.

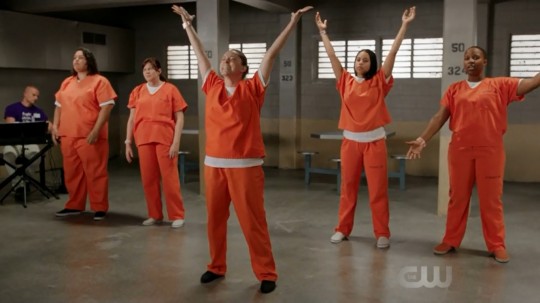

I had hoped that was the case until Cloudy With a Chance of Meatballs.

This is one I don't actually see lambasted as often. Maybe because the Chicken Run trauma crew grew thicker skins before this movie. I only sort of did. Maybe because no one ever actually invested in this film, having already predicted how much it would be garbage from the dumb humor in the trailers. Oh, but not me. I was a fool. Also my family picked it for a movie night so my fate was sealed anyway.

The original book is actually pretty frightening on its own. Food falls from the sky in such great numbers that it starts to destroy the world. Okay, that's terrifying. But kind of in the alluring way. I would keep coming back to the one page about the giant pancake on the school because the way it was drawn unsettled me so, with something huge and immovable blocking off the way to a building that usually has hundreds of innocent children inside. The film built on this and made it a thousand times worse.

Let's start with the goddamn Spray-On Shoe. Our main character is a mad scientist (but the good kind, apparently) whose list of bumbling failed experiments dates back to when he was a child and invented a spray you could put on your feet to coat them in shoes. He then gets laughed at because he didn't engineer a way to get the shoes off, and runs home in humiliation. Guys, the teasing/bullying factor is...not the most worrying thing about this story. There's a throwaway line about how Flint wears THE SAME SHOES into adulthood because to that day they simply cannot be removed. This seems like an incredibly urgent medical problem? Having your feet encased in the same rubber for years? The same rubber as when you're a kid? I just found myself thinking "What if my shoes never came off one day" and that terrifies me, okay? It's stupid and it's silly and it scares me. Even more than that, though, is the canonization of a polymer in this universe that can be sprayed on sticky and will literally never break no matter what you do to it, because that goes back to the pie machine dough principle. Being glued to a surface permanently is inherently terrifying and we'll go over this later because this is not the last fuckin time the glue shoes get brought up.

Flint invents a food-spewing machine. It ends up in the sky. He rides his popularity as it rains larger and larger food down upon the town and also the world. Most of this film up until the climax is unsettling but not AWFUL. Where it starts to go to shit is when Flint realizes his machine is too dangerous and shuts it off, only for the town's local greedy politician to switch it back on into an apocalyptic mode. So can we start with "Local town finds out its elected official is willing to sabotage their well-being in order to capitalize on the fame of a disaster-causing object?". Like, the whole film would've been solved so much sooner if there hadn't been a saboteur in the works - not a fun campy villain, mind you, but a saboteur who exists to drive the plot to the scary place. But I guess we need that narrative tension to justify having a film in the first place, so fine, I'll ride it out.

The main crew saddles up to fly out to the machine, which is now encased in a FLESH LABYRINTH of food, and...I'm just gonna rapid-fire the shit that happens at this part:

-The food turns sentient in order to defend itself. The cute animal sidekick brutally dismembers an army of gummy bears that is fully sentient and rips them apart to devour them.

-We enter the flesh labyrinth and it's exactly as much a horror RPG setting as you think it is.

-Now sentient cooked chickens besiege the party. The comic relief character is consumed by one, only to kill it from the inside and decide to WEAR ITS SKIN in what is seen as his defining character arc's conclusion. Wearing the skin of a dead monster allows him to forge his new identity.

-One of our party has to go back because of a tight passage lined with her deadly allergen, causing her to undergo anaphylaxis after an accidental mild nick. In the flesh labyrinth.

-The entire horrific journey is instantly INVALIDATED when it turns out that instead of the kill code for the machine, all Flint has is a file of a cat video. Which he finds out as the town is about to be obliterated off the face of the earth.

-So he solves it by jamming the works with the spray-on shoe and DID I NOT JUST GO OVER HOW HORRIFIC INDUSTRIAL EXPLOSIONS ARE IN KIDS' MOVIES? DID I NOT? ARE WE REALLY DOING THIS AGAIN? Anyway it's canonical proof that NOTHING can break the shoe glue and I should be happy for the town and happy that there's no more flesh labyrinth of living meat but instead I'm just terrified because of the door we have opened. We have imparted the existence of an indestructible sticky polymer upon the world.

-It's later seen used in a credits sequence to repair damaged houses. Which, first of all, given its flexible nature, is fuckin stupid. It won't serve as an actual wall. Second, that got me thinking about construction accidents involving the fuckin shoe glue. If that stuff gets dripped on a person's face -

-So then cue me sitting awake in bed later thinking wide-eyed about Cloudy with a Chance of Fucking Meatballs and realizing that this compound that is essentially a chemical weapon in the making is now in the hands of the mayor who deliberately caused an apocalyptic event over the town because he wanted the food rain. And THAT'S not going to lead to pretty circumstances.

I think you'll see that a lot of my fears with these two movies is "THINK OF THE IMPLICATIONS!" and I think that just shows how my mind works and why I'm drawn to fanfic so much. I'm all about diving into a universe, exploring its corners, analyzing it to death.

And with the industrial horror stuff, I kinda wanna bring it around to two other films that actually really subverted my expectations and made it fun. 102 Dalmatians was a fave of mine through middle school, but I remember when the climax took us to a big ol' factory and I got plumb nervous. After the usual blades and ovens of horror, the fact that it concludes with Cruella basically wearing a cake and a lengthy montage of the dogs kicking toppings onto her is just one of the most wholesome imageries. She survived the thing and now you get to watch her be decorated Lisa Frank style by her victims who are more interested in humiliation than murder, and I love that.

But maybe more prevalent is that I'm well aware that if certain filmography or plot points had been handled in different ways, The Boxtrolls might've actually frightened the ever-loving fuck out of me what with all the industrial stuff and medical horror, but I just...felt like that film was holding my hand the whole way through going "It's okay." The industrial stuff was framed in a way that was just campy enough and yet also taken seriously. Putting a really charismatic villain - ACTUAL VILLAIN, NOT CHICKEN FARMER OR CORRUPT POLITICIAN SABOTEUR - at the wheel was just such a mitigating factor that it gelled the whole thing together and I ended up LOVING what was done with giant machines and garbage crushers and explosions. And as for the medical body horror, I really appreciate how it was so baked in that Snatcher did that to himself - that everyone, EVERYONE warned him "Do not do this, you will probably die, I'm serious, bad fucking idea" up to the point of Eggs trying to plead him during an anaphylaxis attack, one last time, DO NOT continue down this path, we can find a way to heal you psychologically and get you some self-fulfillment. And Snatcher fully chooses hubris over the many, many opportunities offered him to be able to step down onto a safer path and that removes the fear and pulls it more into a tragedy for the villain. Not at all the same thing as "Sam the reporter is trying to save the world and doing her best until a fixture of the landscape accidentally sends her into anaphylaxis."

(Oh, and by the way, can I just - when I do see CWACOM brought up these days, it's always in the context of "This is the one movie where the guy tells the girl it's okay to look nerdy!". Well, no, not the way I remember it. The way I remember it, Sam basically tells Flint "I used to have really tacky style but have since changed it up of my own volition" and Flint is just like "NOOOOO YOU NEED TO WEAR GLASSES AND A SCRUNCHIE. I WANT A HOT NERD GIRL." This could've been pulled off right with some more introspection into female beauty standards, even in a tongue-in-cheek way, but right now it really looks like Sam just wanted to make herself more glam for a new image and Flint bullied her into regressing her style. Which I've also realized meant he bullied her into dressing more like she did as a teenager and normally I think that kind of shit is just "You're overthinking it" but since it's CWACOM and I spelled it out on paper like that, I'm just now realizing how that can be seen as pretty...icky.)

The one saving grace of CWACOM is that I was older by that time, and so it didn't affect me as hard as Chicken Run. But I still hold it dearly to my heart as one of the MOST DISTURBING movies I know, and by "dearly" I mean "fuck this movie, really and truly." I want to extend my thanks to 102D and Boxtrolls for giving me industrial-horror-based climaxes that were actually really comfortable, and again, probably what drove both of these was the fact that we had a campy diva villain in the lead for the potential scary stuff to surround and radiate off. Not a fuckin...ordinary chicken farmer who is just trying to make bank but is somehow passed as a Nazi allegory for trying to live her life as a farmer? I dunno, maybe if I rewatched that film I'd see she has a thirst for human blood too, and if I could fix fic Chicken Run my first order of business would be to give her a thirst for human blood instead of/in addition to chickens.

Anyway. Fuck both these films, EXCEPT for the fact that traumatizing scenarios can always be recast as whump material, and the next time I wanna do some crossover aftercare from a physically and psychologically damaging mission, I have a pie machine and a flesh labyrinth to exploit. REALLY HEAVY ON THAT AFTERCARE COMFORT THOUGH!

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

11 Diverse Vampire Stories To Read Instead of Midnight Sun

https://ift.tt/eA8V8J

There’s a very good chance we’re going to read Midnight Sun, the companion novel to pop culture juggernaut Twilight that retells the first story in the Stephanie Meyer YA vampire series from Edward Cullen’s perspective. But we can enjoy something while also being critical of it, and the truth is: our culture deserves more, better vampire stories than what the Twilight saga has to offer. With that in mind, we’ve pooled our collective knowledge to recommend the following vampire stories that have more diverse and imaginative takes on the popular genre. From short stories to book series, hopefully there’s something here for you…

Fledgling by Octavia Butler

A good general rule of life to follow is that if Octavia Butler has written something in a particular genre, you should read it. And that’s as true in the world of vampire fiction as anywhere else. Fledging was the final book Butler published before her untimely death in 2006 and, though it’s technically a vampire story, it’s also a whole lot more than that.

Much in the same way that Butler’s Kindred is a time travel story that tackles physical and psychological horrors of slavery, Fledging is a vampire tale that explores issues of racism and sexuality. In it, a 10-year-old girl with amnesia discovers that she’s not actually a girl at all, but a fifty-something hybrid member of the Ina. Ina are basically what we understand as vampires in this universe – they’re a nocturnal, long-lived species who survive by drinking human blood. They’ve formed something of a symbiotic relationship with the humans they live alongside, using them as a food source in exchange for boosting their immune systems and helping them live (much) longer.

As Shori regains her memories of her former life, Fledging uses her unique situation as an avenue to explore timely issues of bigotry and identity. As a human-Ina hybrid, Shuri has been genetically modified to have dark skin, allowing her to go outside for brief periods during the day, but drawing the ire and distrust of others. As the novel further explores complex issues of family and connection – both the Ina and their human symbionts tend to mate in packs – Butler pokes at Shori’s uniquely uncomfortable position of being the master over one particular group, even as she herself is considered part of something like an underclass within Ina culture. And the end result is something that’s much more than a vampire tale, even as it embraces—and outright parodies—some of its most obvious tropes.

– Lacy Baugher

Buy Fledgling by Octavia Butler on Amazon

The Coldest Girl in Coldtown by Holly Black

Twilight’s sin was not in trying to make vampires sexy all over again (it’s OK to make bloodsuckers cool), but rather in amplifying the teenage girl protagonist’s desire while blunting her agency. In doing so, Meyer maintained the dynamic of traditional vampire narratives instead of modernizing it. Five years after Breaking Dawn was released, Holly Black redeemed the YA vampire novel with her standalone tale, set in a world where it’s not just one hormonal teenager who’s dying to be a vampire, but all of society craving that sweet sweet immortality.

In Black’s world, everyone wants to be Cold: infected by a vampire bite but neither killed nor made into a fully-fledged vampire. Not until they drink human blood, at least. But in an effort to control the rising population of vampires and Cold people, the governments created Coldtowns, trapping both in a never-ending party town. The titular Coldest girl is Tana, who wakes up after a (very human, very teenage) rager to find almost everyone slaughtered and herself bitten. Fearing that she has become Cold, she voluntarily turns herself in to the nearest Coldtown along with her also-bitten ex-boyfriend Aidan and Gavriel, a vampire who seeks to take down the uber-vampire who rules the Coldtown.

The Coldest Girl in Coldtown is a sly riff on the vampire obsession that took over pop culture in the early 2000s, yet still its own cautionary tale about chasing after a glamorous, self-destructive afterlife. The cast of characters are fully fleshed-out, from a twin with a fangirl blog to Gavriel as an actually suitable vampire love interest to Tana Bach herself, who gets to be proactive where Bella Swan was always reactive. Best of all, it knows that it doesn’t need to lure readers back to a franchise, like vampires returning again and again to feed, instead telling its entire story in one bloody, chilly gulp.

—Natalie Zutter

Buy The Coldest Girl in Coldtown on Amazon

Carmilla by Joseph Sheridan LeFanu, edited by Carmen Maria Machado

A quarter-century before Bram Stoker’s Dracula, a different vampire seduced young women away from the suffocating constraints of their lives by awakening within their blood a thrilling, oft-considered perverse, desire. That it is a female vampire—the eponymous Carmilla, known also by her aliases Mircalla and Millarca—likely explains why LeFanu’s text is either incredibly well-known among niche circles, or entirely absent from pop cultural canons. Yet the moment you read it, its depiction of the heady attraction between innocent Laura and possessive Carmilla is anything but subtext.

Like Dracula, this Gothic horror novella is presented as a found text, with a frame narrative of occult detective Dr. Hesselius presenting Laura’s bizarre case… but also to some extent controlling her voice. In her new introduction, Machado posits a startling new contextualization: that Hesselius and Laura’s correspondence is not a fictional device, but a fictionalization of real-life letters between a Doctor Peter Fontenot and Veronika Hausle, about the latter’s charged relationship with the alluring Marcia Marén. That their relationship provided the basis for Laura and Carmilla, but that only the tragic parts were transmuted through the vampire metaphor, excising the queer joy of their partnership, further illustrates how these stories fail their subjects. Yet neither is Marén wholly innocent; as with In the Dream House, Machado does not flinch away from imperfect or even violent queer relationships, such as they resemble any other dynamic between two people.

It’s best to read Machado’s Russian nesting doll narrative without knowing much about her motivations. Though it might be useful to consider how she ends the introduction with something of a confession: “The act of interacting with text—that is to say, of reading—is that of inserting one’s self into what is static and unchanging so that it might pump with fresh blood.” Or try running some of these names through anagram filters.

And if that whets your appetite for other adaptations, the 2014 Carmilla web series both wrestles the frame story back into Laura’s hands, in the form of a video-diary journalism project, and makes the Laura/Carmilla romance very much text.

—Natalie Zutter

Buy Carmilla on Amazon

A Phoenix Must First Burn, edited by Patrice Caldwell

A Phoenix Must First Burn is a collection of sixteen short stories about magic, fantasy, and sci-fi that focus on Black women and gender non-conforming individuals. The book features stories about fantasy creatures of all kinds, witches, shape shifters, and vampires alike. What they have in common is that they are stories about and by Black people, and they offer unique takes on familiar lore.

Bella Swan is a great protagonist in the Twilight series because she is whatever the reader needs her to be. Just distinct enough that you can conjure her in your mind, but mostly a blank slate for the reader to step into the story with her, using her as their avatar. That’s a generality specific to White characters. In A Phoenix Must First Burn, the protagonists are Black. This gives them a very particular point of view, and one that isn’t as common in fantasy, and in the vampire tales of yore.

In Stephenie Meyer’s world vampires look like they’re lathered in Fenty body shimmer when they’re in direct sunlight. In “Letting the Right One In,” Patrice Caldwell gives us a vampire who is a Black girl, with dark brown skin, and coiled hair. Sparkling vampires are certainly a unique spin, but the Cullens are still White and don’t challenge any ideas of what it means to be an immortal blood-drinking creature of the night. A Phoenix Must First Burn shifts the lens to focus on the experience of Black folks, and allows them to be magical, enigmatic, and romantic.

– Nicole Hill

Buy A Phoenix First Must Burn on Amazon

Certain Dark Things by Silvia Moreno-Garcia

In the Twilight series, we’re introduced to vampires from other cultures, but they are all very much the same, save for their individual power sets which appear to be unrelated to their ethnicity or nationality. In Certain Dark Things, vampires are a species with several different subspecies and where they come from influences how they look and what kind of powers they have.

Atl is from Mexico and is bird-winged descendent of Blood-drinking Aztecs. The Necros, European vampires, have an entirely different look and set of abilities. Certain Dark Things doesn’t just include vampires from all around the world, it incorporates vampire mythology from all of those places, filling its world with a rich array of distinct vampires with their specific quirks and gifts.

In his four-star review of the book on Goodreads, author Rick Riordan had this to say. “Throwing vampire myths from so many cultures together was right down my alley. If you like vampire books but would appreciate some . . . er, fresh blood . . . this is a fast-paced read that breathes fresh life into the genre.” Riordan, who opened up his literary world to new storytellers and has championed authors of color is certainly a person whose opinion holds weight. Vampires haven’t gone out of style, but the Draculas and Edward Cullens are.

– Nicole Hill

Buy Certain Dark Things on Amazon

Vampires Never Get Old, edited by Zoriada Córdova & Natalie C. Parker

This anthology featuring vampires who lurk on social media just as much as they lurk in the night will hit the bookstore shelves on September 22, just in time to start prepping for Halloween. Edited by Zoriada Córdova and Natalie C. Parker, the collection features eleven new stories and a really fantastic author list, populated with a diverse group of authors from a ton of backgrounds and sexualities. The contributors include V. E. Schwab, known for her “Darker Shade of Magic” series; Nebula, Hugo, and Locus Award-winner, Rebecca Roanhorse; Internment author Samira Ahmed; Dhionelle Clayton, author of The Belles and Tiny Pretty Things; “The Blood Journals” author Tessa Gratton (who also contributed to the super spooky looking Edgar Allan Poe-inspired His Hideous Heart); Heidi Heilig, author of the “Shadow Players” trilogy; Julie Murphy, whose book Dumplin’ was adapted for the Netflix film of the same name; Lammy Award winner Mark Oshiro, whose forthcoming YA fantasy Each of Us a Desert will hit stands just before this anthology; Thirteen Doorways author Laura Ruby; and essayist and short story writer Kayla Whaley.

There are a lot of YA authors on this list, many of whom crossover to adult, so there’s a good chance readers will find some of their favorite kinds of angsty vampires on these pages, as well as body-conscious vampires, and vamps coming out as well as going out into the night, seeking for their perfect victim—or just looking for love.

– Alana Joli Abbott

Buy Vampires Never Get Old on Amazon

Choice of the Vampire by Jason Stevan Hill

Back in 2010, when I was first getting to know interactive fiction, Jason Stevan Hill wrote Choice of the Vampire for the still-relatively new company, Choice of Games. A sequel came out in 2013, and this year, the third interactive novel, in which you, the reader make the choices, releases. Best played from a mobile device (although you can play in your browser as well), the interactive novels from Choice of Games are always fun (disclosure: I have written a few), and they’re dedicated to featuring inclusive options to let players express their personalities, gender identities, and sexualities within the confines of the game. Choice of the Vampire starts players as young vampires in 1815 New Orleans. In The Fall of Memphis, the story moves to 1873, and rather than facing the concerns of learning to survive their unlife adventures, players get embroiled in the politics of Memphis, where vampires are electing a new Senator, and the Klan is on the rise.

With the release of St. Louis, Unreal City, the intention is that the two earlier games will be combined into one larger omnibus, so that players can have an uninterrupted play experience of the full story. St. Louis, Unreal City moves the story forward into 1879, in a St. Louis where the first wave of Chinese immigrants and the dismantling of Reconstruction force the city to face its systemic racism. As workers demand greater rights—and rich financiers attempt to keep control of the nation’s wealth—vampires have to continue to hide, lest they be destroyed. But when one of their own lets loose the beast, causing terror in the streets of America, players have to decide how their character will triumph in a changing world. Stevan Hill pours a ton of historical detail into the scenes he creates, making these vampire stories as much historical fiction as they are fantasy or horror. In advance of the release of the newest installment, the first two games have been updated with new material, so if you’ve played them before, they’re worth a replay before you launch into Night Road!

– Alana Joli Abbott

Moonshine by Alaya Dawn Johnson

Like the first two Choice of the Vampire stories, Moonshine, which came out in 2010, embroils its protagonist in the social struggles of its era: the 1920s of New York City. Zephyr Hollis is an activist, devoted to creating equality for both humans and Others, including vampires, despite her upbringing as the daughter of a demon-hunter. She’s immune to vampire bites, which is helpful when she discovers a newly-turned child vampire; if she turns him in, the authorities will kill him, so soft-hearted Zephyr takes the child in and feeds him her own blood. When she’s approached by a jinn, Amir, to use her cover as a charity worker to undermine a vampire mob boss in exchange for his help with the child, he doesn’t explain what he’s after—but Zephyr’s intrigued enough by the idea (and Amir) that she gets involved. If you already finished Johnson’s newest novel, The Trouble with Saints (also set in historical New York, this one during World War II), returning to this earlier novel and its sequel, Wicked City, will be a fast-paced treat.

Buy Moonshine on Amazon

“A Kiss With Teeth” by Max Gladstone

There are not a ton of stories out there about vampire parenting—and fewer that are more about what it means to be a parent, what it means to give up the person you were before (even it that person was a monster). Max Gladstone’s 2014 short story, published at Tor.com, is absolutely a vampire story in the classic sense: a hunt, a victim, a struggle. But it’s also the tale of a vampire, Vlad, who settles down with a vampire hunter, and the changes that settling down create for both of them. How can a parent be honest with his child when he’s hiding something so core to his identity? Even playing baseball in the park requires Vlad to hide his own strength. And how can he work with the teacher to help his son with struggling grades when that teacher is the ideal prey? The idea of being a vampire blends with the idea of hiding an affair, of planning to do something that shouldn’t be done, and then determining whether or not to do it. The way the story is written, it’s hard to tell where it’s going to go, or how two parents hiding so much about themselves can ever be honest with their child—but when it comes to the end, Gladstone knocks it out of the park.

– Alana Joli Abbott

Queen of Kings by Maria Dahvana Headley

The visual of Cleopatra dying with a poisonous asp clutched to her breast is an iconic, Shakespearean-tinged bit of history that we all learned in our ancient Egypt history units. However, Headley’s debut novel gives the queen a bit more credit, by reimagining that instead of going all Romeo and Juliet after the supposed death of her lover Marc Antony, she strikes a bargain with Sekhmet, goddess of death and destruction who has nonetheless begun fading away due to a dearth of worship. In Shakespearean fashion, things go awry when Sekhmet seizes control of Cleopatra, transforming her into an immortal being and transmuting her revenge into a literal bloodlust.

Unable to die, with her lover still slain and her children in danger, Cleopatra must battle the dark force within her urging her to drain others of their lifeforce and let loose Sekhmet’s seven children (plague, famine, drought, flood, earthquake, violence, and madness) upon the ancient world. What’s more, she also has to contend with the mortal threat of recently-appointed emperor Caesar Augustus and the three sorcerers he has rallied to fight the queen-turned-demigod. Drawing from Egyptian mythology to contextualize various familiar vampire tropes (the aforementioned bloodsucking, aversion to sunlight, and weakness for silver), Queen of Kings reinvigorates the vampire mythos through a historical figure who deserved to exist long beyond her mortal lifetime.

—Natalie Zutter

Buy Queen of Kings on Amazon

Carpe Jugulum by Terry Pratchett

Sir Terry never met a trope he didn’t take the opportunity to parody, but his Discworld take on the vampire mythos is more love bite than going for the jugular. His Magpyrs embody the classic vampires, with all their subgenre trappings, but also are an example of how a supernatural race seeks to evolve beyond its bloody history and try something new. To be clear, these Magpyrs are still in it to drain humans dry, and they’ve developed cunning methods of doing so: a propensity for bright colors over drab blacks, the ability to stay up til noon and survive in direct sunlight, a taste for garlic and wine along with their plasma.

But the clash between the youngest immortals, who seek to overtake the mountain realm of Lancre as their new home, and dutiful servant Igor, who misses “the old wayth” (he’s a traditionalist down to the lisp), reveals a tension familiar to any long-ruling dynasty or established subculture: Change with the times, or adapt but lose what makes you unique? In struggling with this intergenerational dilemma, the Magpyrs find the perfect opponents in Lancre’s coven: Granny Weatherwax, Nanny Ogg, Magrat, and Agnes—four witches who find themselves taking on different roles within the mother/maiden/crone dynamic as life changes force shifts in their identities. Between these relatable personal conflicts and a hall of vampire portraits that pays homage to Ann Rice and Buffy the Vampire Slayer, Carpe Jugulum gently ribs the vampire subgenre rather than put a stake through its heart.

—Natalie Zutter

Buy Carpe Jugulum on Amazon

Do you have any vampire story recommendations that challenge the traditional tropes of the genre in interesting and diverse ways? Let us know in the comments below.

The post 11 Diverse Vampire Stories To Read Instead of Midnight Sun appeared first on Den of Geek.

from Den of Geek https://ift.tt/2DmueuR

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

West Side Story, Twin Peaks, and the Death of the 60s

I poke around at this a lot, but I thought it might be good to get it all down in one place.

I feel like I grew up in an eclipse of West Side Story. Grease had taken over its space as a specific cultural artifact, and it wasn’t pushed on TV that much. When I got around to it, I realized it was not what you might think it was – it was influential way past the direct references like Springsteen’s first 3 albums, theater offshoots, and modern Romeo and Juliet takes. The filmmaking was daring and I noticed may stolen shots (this is about David Lynch, so I’ll use an example of the dissolve to the party being stolen for the jitterbug contest at the beginning of Mulholland Drive) not to mention the way New York City is shot becoming the only way to shoot it in the 70s and 80s.

The color scheme bears notice. The Jets have goldenrod jackets and light blue ensembles, while the Sharks are purple and red (there is that one Orange girl that really pops) with a red background at the dance. The jacket yellow and the red and white of Maria’s dress are the same as those of the high school in Twin Peaks. Here, look:

Tony and Maria

Tony and Maria

But the real connection I want to make is the lead actors in WSS, both of whom were cast in Twin Peaks: Richard Beymer playing yearning Tony then scheming capitalist Ben Horne and Russ Tambyn playing gotta move Biff then try anything burnout, metoo bait Dr. Jacoby.

The characters in Twin Peaks are embedded in a web of reflections and foils and, in many ways this diad is the center of that, even though they shared no scenes in the show (which is why the pic is a rarity). But let’s look for a minute at these two actors and their lives.

Richard Beymer was a child actor that, other than WSS and Twin Peaks, is primarily known for journeyman TV work. His WSS role was that of a guy who wants something specific and peruses it who has a job and generally follows the rules. The actor was, for most of his life, an example of someone in the glass closet, but he dated Sharon Tate before that choice. He was more associated with the mod end of the 60s “split,” though he marched for civil rights. He settled into a typical TV guest starring career playing the straight-man career guy.

Russ Tamblyn wanted to be a circus performer and, other than WSS and Twin Peaks, is primarily known for dance. His WSS role was that of a guy who is all energy and just wants to engage and experience who has no job and generally flaunts the rules. The actor has been married and divorced many times, including to a Vegas showgirl. He was more associated with the hippie end of the 60s “split,” and gave Charles Manson a ride in his VW bus once. His career is wild and diffuse, but he worked predominantly as a choreographer.

There is much cultural myth acceptance of the Joan Didion narrative, that the problems with the 60s were there but the Manson Murders were when the idealism gave way and birthed the harsh 70s: the murders were the moment the 60s died. In a way, it is a story of the dirty hippie 60s leaking into the flashy Hollywood 60s. But then, every male on both sides involved even peripherally with the event was guilty of rape and there was a way that all “sin” was normalized. That’s the story, anyway, but we’re talking about stories. Beymer was Tate adjacent, Tamblyn ran in Manson circles. Beymer and Tamblyn, from a purely superficial narrative lens, lived the two sides of the ideal 60s. But after the 70s came the 80s.

In the 80s, the spirit of the 60s, such as it was, had given way to two archetypes that were fairly legible in entertainment at the time – the sellout and the burnout. The businessman ruled by greed (Gordon Gekko was the apotheosis) and the hippie whose fading cognition struggled to remember the last 10-20 years had happened at all (think the image of Regan era Dennis Hopper, especially his Flashback character Huey Walker). It’s this that Twin Peaks was drawing on for the characters of Ben Horne and Jacoby.

So the threads here are cute and obvious. In casting Twin Peaks, they took WSS’s straight-laced icon of “you want it you take it you pay the price,” played by a lifelong career actor and Sharon Tate dater, and cast him as the rich businessman trope, and took WSS’s delinquent icon of “if it feels good, man,” played by a far out maximum experiencer and Manson valet, and cast him as the fried hippie trope. Great, just regular casting, right? But how does this build a network of associations?

The first most obvious reflections of the pair are Mike as Jacoby and Bob as Ben. These are archetypal characters that represent the rapacious consumption (Bob) and the seeking/experiencing-tendency which has stepped out too far (Mike). Mike also “splits” into the Mike the spirit and Philip Gerard which reflect a kind of addiction to experience that Philip eventually “kicks.” All this is centered around the idea of Garmonbozia, an ambivalent symbol of industrially ground down life essence produced by pain and suffering (sort of too much experience embodied but also a kind of jouissance the bad system depends on) which Bob and Mike sought but Phil has disavowed by cleaning up. This all relates to absent mother Judy but talk about her we won’t.

Ben is also reflected in Jerry, his brother, splitting the avarice of the Wolf of Wall Street type into the power hunger (Ben) and the hedonism (Jerry). He is further diffracted by the generational lens into Gen X Audrey and (in later S2) Bobby. Audrey is the youthful activism trying to reassert itself in the child, and Bobby turns into Alex P Keaton, the young stepper and protégée (that whole plot line reminds me of Family Ties for some reason). The connections to other characters continue on their own wavelengths. Audrey mirrors Laura, who is mirrored by Donna and Maddie, many other businessmen reflect Ben, Bobby bounces off of James and Mike (no relation), Bob’s gender reflected mom Judy is Naido is Diane, etc. There’s even an 11th hour play to connect Doc Hayward to Ben in a good dad/bad dad plot.

Mark Frost has always said that they were cast because they were the best actors for those roles, but Lynch’s casting by feel with no audition process is well known - he’s looking for people to “paint” with. The history here brings up powerful associations that may have made him feel quite a lot. I got through this entire post without using the word Boomer, not sure how, but Tamblyn and Beymer were both Silents who code as late and early Boomers respectively.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Some thoughts on Tokyo Ghoul hair symbolism

I’m sure there’s probably like, 49602693 confirmed theories on Kaneki and other characters’ hair changes, but someone was asking me about this the other day and I had to write down my own thoughts. (This is phrased in a way that’s friendly to anime-onlys who are caught up as well, since that was the person asking me).

In terms of Kaneki’s hair turning white, I think Marie Antoinette syndrome is only a fitting trope for the first time his hair turns white-- after being tortured-- as other situations like his fight with Arima in Cochlea would /not/ cause Marie Antoinette syndrome (his hair changed colors before the fight truly began) and it still wouldn’t explain why his hair suddenly turns to black again and so on. But alas, anime does exaggerate things so who am I to totally out-rule this idea. Also I don’t even know if tg fans still bring up Mary Antoinette Syndrome.... I may just be old..

Anyway, moving on to my personal thoughts on the hair dilemma.

Whenever Kaneki’s hair turns white it represents him accepting the half of himself that’s a ghoul, or acceptance of his place in both worlds/responsibilities towards them. When his hair turns white the first time, the kind boy in denial changed into something more ruthless, and he immersed himself entirely into the ghoul world (in the manga this symbolism makes more sense, because instead of joining Aogiri like the anime, he creates his own band of close friends who are ghouls to work with).

His black hair, conversely, represents his feelings of obligation towards his human half. So, back to the whole in-denial thing at the very beginning of the series: his hair remains black even as a one-eyed ghoul, because he is clinging desperately onto his humanity. His hair turns black again sometime in :Re when his memories return, as we’ve just seen in the anime, because he decides to fully devote himself to acting like a human investigator at the CCG (again, this makes more sense in the manga where we see more scenes of him coldly exterminating ghouls and carrying out his missions, instead of skipping straight to the Black/White Reaper fight scene).

After seeing Touka and getting a mental scolding from Hide in that arc, he is convinced not to throw his life away and live with the people he cares about, as a one-eyed ghoul once more-- and so his hair turns white.

I left an explanation of Haise’s hair for the end so that I could explain the two colors separately first, but now that I have I think it’s pretty straightforward. Haise’s hair is half black and half white because of his identity issues, struggling between living as mainly a human in the CCG and clinging to his past as a ghoul in Anteiku.

Very simply put; Black = humanity. White = ghoulhood. (Those labels are relative to whatever they might mean for Kaneki at the time of him donning them).

To add even further support of this, it happens with Juuzou too. Juuzou has white hair in the beginning while he’s a bit off his rocker/inhuman, and with Sonohara’s guidance (and eventual death) he sets himself on the right path/becomes more human, and by the time we see him again in :re, his hair has been changed to black to represent that humanization. We also see the white hair repeat in other characters like Takizawa and [Minor manga spoilers -->] Tooru when they either get turned into ghouls or start using their ghoul abilities to the fullest. In the end, unlike Juuzou whose hair became black after his redemption, Tooru’s hair remains white like Kaneki’s, because he is able to be himself with his, “family,” while still utilizing his ghoul abilities.

Anyway, these are just my independent thoughts on it all, not having bothered to look up discussions about it in my many years of reading Tokyo Ghoul. What do you guys think? Is there any artistic meaning at all to Ishida’s black/white hair choices? Or am I just a fool because there’s already a confirmed explanation somewhere? Let me know (ノ ´ ◡ ` )ノ*: ・゚

EDIT: to clarify, I’m talking about the possible literary/artistic symbolism in hair colors of tokyo ghoul. There are in-story explanations involving rc counts to rationalize these changes within the narrative, but this post’s theories and the canon “scientific” explanation are not mutually exclusive. Also removed a whole section about marie antoinette stuff because these were just shower thoughts that I didn’t expect to blow up and now I wanna refine them.

#tokyo ghoul#tokyo ghoul:re#tokyo ghoul discourse#tg#tg:re#tg manga#tokyo ghoul manga#marie antoinette syndrome#kaneki's hair#sasaki haise#kaneki ken#black reaper#black reaper kaneki#shironeki#kuroneki#tokyo ghoul symbolism#tokyo ghoul analysis#tokyo ghoul discussion

146 notes

·

View notes

Link

Now that the cast is coming together, Denis Villeneuve’s upcoming adaptation of Dune is getting more attention than ever. And with that attention an interesting question has started cropping up with more frequency, one that bears further examination: Is Dune a “white savior” narrative?

It’s important to note that this is not a new question. Dune has been around for over half a century, and with every adaptation or popular revival, fans and critics take the time to interrogate how it plays into (or rebels against) certain story tropes and popular concepts, the white savior complex being central among them. While there are no blunt answers to that question—in part because Dune rests on a foundation of intense and layered worldbuilding—it is still an important one to engage and reengage with for one simple reason: All works of art, especially ones that we hold in high esteem, should be so carefully considered. Not because we need to tear them down or, conversely, enshrine them, but because we should all want to be more knowledgeable and thoughtful about how the stories we love contribute to our world, and the ways in which they choose to reflect it.

So what happens when we put Dune under this methodical scrutiny? If we peel back the layers, like the Mentats of [Frank] Herbert’s story, what do we find?

Hollywood has a penchant for the white savior trope, and it forms the basis for plenty of big-earning, award-winning films. Looking back on blockbusters like The Last of the Mohicans, Avatar, and The Last Samurai, the list piles up for movies in which a white person can alleviate the suffering of people of color—sometimes disguised as blue aliens for the purpose of sci-fi trappings—by being specially “chosen” somehow to aid in their struggles. Sometimes this story is more personal, between only two or three characters, often rather dubiously labeled as “based on a true story” (The Blind Side, The Help, Dangerous Minds, The Soloist, and recent Academy Award Best Picture-winner Green Book are all a far cry from the true events that inspired them). It’s the same song, regardless—a white person is capable of doing what others cannot, from overcoming racial taboos and inherited prejudices up to and including “saving” an entire race of people from certain doom.

At face value, it’s easy to slot Dune into this category: a pale-skinned protagonist comes to a planet of desert people known as Fremen. These Fremen are known to the rest the rest of the galaxy as a mysterious, barbaric, and highly superstitious people, whose ability to survive on the brutal world of Arrakis provides a source of endless puzzlement for outsiders. The Fremen themselves are a futuristic amalgam of various POC cultures according to Herbert, primarily the Blackfeet Tribe of Montana, the San people, and Bedouins. (Pointedly, all of these cultures have been and continue to be affected by imperialism, colonialism, and slavery, and the Fremen are no different—having suffered horrifically at the hands of the Harkonnens even well before our “heroes” arrive.) Once the protagonist begins to live among the Fremen, he quickly establishes himself as their de facto leader and savior, teaching them how to fight more efficiently and building them into an unstoppable army. This army then throws off the tyranny of the galaxy’s Emperor, cementing the protagonist’s role as their literal messiah.

That sounds pretty cut and dried, no?

But at the heart of this question—Is Dune a white savior narrative?—are many more questions, because Dune is a complicated story that encompasses and connects various concepts, touching on environmentalism, imperialism, history, war, and the superhero complex. The fictional universe of Dune is carefully constructed to examine these issues of power, who benefits from having it, and how they use it. Of course, that doesn’t mean the story is unassailable in its construction or execution, which brings us to the first clarifying question: What qualifies as a white savior narrative? How do we measure that story, or identify it? Many people would define this trope differently, which is reasonable, but you cannot examine how Dune might contribute to a specific narrative without parsing out the ways in which it does and does not fit.

This is the strongest argument against the assertion that Dune is a white savior story: Paul Atreides is not a savior. What he achieves isn’t great or even good—which is vital to the story that Frank Herbert meant to tell.

There are many factors contributing to Paul Atreides’s transformation into Muad’Dib and the Kwisatz Haderach, but from the beginning, Paul thinks of the role he is meant to play as his “terrible purpose.” He thinks that because he knows if he avenges his father, if he becomes the Kwisatz Haderach and sees the flow of time, if he becomes the Mahdi of the Fremen and leads them, the upcoming war will not stop on Arrakis. It will extend and completely reshape the known universe. His actions precipitate a war that that lasts for twelve years, killing millions of people, and that’s only just the beginning.

Can it be argued that Paul Atreides helps the people of Arrakis? Taking the long view of history, the answer would be a resounding no—and the long view of history is precisely what the Dune series works so hard to convey. (The first three books all take place over a relatively condensed period, but the last three books of the initial Dune series jump forward thousands of years at a time.) While Paul does help the Fremen achieve the dream of making Arrakis a green and vibrant world, they become entirely subservient to his cause and their way of life is fundamentally altered. Eventually, the Fremen practically disappear, and a new Imperial army takes their place for Paul’s son, Leto II, the God Emperor. Leto’s journey puts the universe on what he calls the “Golden Path,” the only possible future where humanity does not go extinct. It takes this plan millennia to come to fruition, and though Leto succeeds, it doesn’t stop humans from scheming and murdering and hurting one another; it merely ensures the future of the species.

One could make an argument that the Atreides family is responsible for the saving of all human life due to the Golden Path and its execution. But in terms of Paul’s position on Arrakis, his effect on the Fremen population there, and the amount of death, war, and terror required to bring about humanity’s “salvation,” the Atreides are monstrous people. There is no way around that conclusion—and that’s because the story is designed to critique humanity’s propensity toward saviors. Here’s a quote from Frank Herbert himself on that point:

I am showing you the superhero syndrome and your own participation in it.

And another:

Dune was aimed at this whole idea of the infallible leader because my view of history says that mistakes made by a leader (or made in a leader’s name) are amplified by the numbers who follow without question.

At the center of Dune is a warning to be mistrustful of messiahs, supermen, and leaders who have the ability to sway masses. This is part of the reason why David Lynch’s Dune film missed the mark; the instant that Paul Atreides becomes a veritable god, the whole message of the story is lost. The ending of Frank Herbert’s Dune is not a heroic triumph—it is a giant question mark pointed at the reader or viewer. It is an uncomfortable conclusion that only invites more questions, which is a key part of its lasting appeal.

And yet…

There is a sizable hole in the construction of this book that can outweigh all other interpretations and firmly situate Dune among white savior tropes: Paul Atreides is depicted as a white man, and his followers are largely depicted as brown people.

There are ways to nitpick this idea, and people do—Paul’s father, Leto Atreides might not be white, and is described in the book as having “olive” toned skin. We get a sense of traditions from the past, as Leto’s father was killed in a bull fight, dressed in a matador cape, but it’s unclear if this is tied to their heritage in any sense. The upcoming film has cast Cuban-Guatemalan actor Oscar Isaac in the role of Duke Leto, but previous portrayals featured white men with European ancestry: U.S. actor William Hurt and German actor Jürgen Prochnow. (The Fremen characters are also often played by white actors, but that’s a more simple case of Hollywood whitewashing.) While the name Atreides is Greek, Dune takes place tens of thousands of years in the future, so there’s really no telling what ancestry the Atreides line might have, or even what “whiteness” means to humanity anymore. There’s a lot of similar melding elsewhere in the story; the ruler of this universe is known as the “Padishah Emperor” (Padishah is a Persian word that essentially translates to “great king”), but the family name of the Emperor’s house is Corrino, taken from the fictional Battle of Corrin. Emperor Shaddam has red hair, and his daughter Irulan is described as blond-haired, green-eyed, and possessing “patrician beauty,” a mishmash of words and descriptions that deliberately avoid categorization.

None of these factors detract from the fact that we are reading/watching this story in present day, when whiteness is a key component of identity and privilege. It also doesn’t negate the fact that Paul is always depicted as a white young man, and has only been played by white actors: first by Kyle MacLachlan, then by Alec Newman, and soon by Timothy Chalamet. There are many reasons for casting Paul this way, chief among them being that he is partly based on a real-life figure—T.E. Lawrence, better known to the public as “Lawrence of Arabia.” But regardless of that influence, Frank Herbert’s worldbuilding demands a closer look in order to contextualize a narrative in which a white person becomes the messiah of an entire population of people of color—after all, T.E. Lawrence was never heralded as any sort of holy figure by the people he worked alongside during the Arab Revolt.

The decision to have Paul become the Mahdi of the Fremen people is not a breezy or inconsequential plot point, and Herbert makes it clear that his arrival has been seeded by the Bene Gesserit, the shadowy matriarchal organization to which his mother, Jessica, belongs. In order to keep their operatives safe throughout the universe, the Bene Gesserit planted legends and mythologies that applied to their cohort, making it easy for them to manipulate local legends to their advantage in order to remain secure and powerful. While this handily serves to support Dune’s thematic indictment of the damage created by prophecy and religious zealotry, it still positions the Fremen as a people who easily fall prey to superstition and false idols. The entire Fremen culture (though meticulously constructed and full of excellent characters) falls into various “noble savage” stereotypes due to the narrative’s juxtaposition of their militant austerity with their susceptibility to being used by powerful people who understand their mythology well enough to exploit it. What’s more, Herbert reserves many of the non-Western philosophies that he finds particularly attractive—he was a convert to Zen Buddhism, and the Bene Gesserit are attuned to the Eastern concepts of “prana” and “bindu” as part of their physical training—for mastery by white characters like Lady Jessica.

While Fremen culture has Arab influences in its language and elsewhere, the book focuses primarily on the ferocity of their people and the discipline they require in order to be able to survive the brutal desert of Arrakis, as well as their relationship to the all-important sandworms. This speaks to Herbert’s ecological interests in writing Dune far more than his desire to imagine what an Arab-descended society or culture might look like in the far future. Even the impetus toward terraforming Arrakis into a green world is one brought about through imperialist input; Dr. Liet Kynes (father to Paul’s companion Chani) promoted the idea in his time as leader of the Fremen, after his own father, an Imperial ecologist, figured out how to change the planet. The Fremen don’t have either the ability or inclination to transform their world with their own knowledge—both are brought to them from a colonizing source.

Dune’s worldbuilding is complex, but that doesn’t make it beyond reproach. Personal bias is a difficult thing to avoid, and how you construct a universe from scratch says a lot about how you personally view the world. Author and editor Mimi Mondal breaks this concept down beautifully in her recent article about the inherently political nature of worldbuilding:

In a world where all fundamental laws can be rewritten, it is also illuminating which of them aren’t. The author’s priorities are more openly on display when a culture of non-humans is still patriarchal, there are no queer people in a far-future society, or in an alternate universe the heroes and saviours are still white. Is the villain in the story a repulsively depicted fat person? Is a disabled or disfigured character the monster? Are darker-skinned, non-Western characters either absent or irrelevant, or worse, portrayed with condescension? It’s not sufficient to say that these stereotypes still exist in the real world. In a speculative world, where it is possible to rewrite them, leaving them unchanged is also political.

The world of Dune was built that way through a myriad of choices, and choices are not neutral exercises. They require biases, thoughtfulness, and intent. They are often built from a single perspective, and perspectives are never absolute. And so, in analyzing Dune, it is impossible not to wonder about the perspective of its creator and why he built his fictional universe the way he did.

Many fans cite the fact that Frank Herbert wrote Dune over fifty years ago as an explanation for some of its more dated attitudes toward race, gender, queerness, and other aspects of identity. But the universe that Herbert created was arguably already quite dated when he wrote Dune. There’s an old-world throwback sheen to the story, as it’s built on feudal systems and warring family houses and political marriages and ruling men with concubines. The Bene Gesserit essentially sell their (all-female) trainees to powerful figures to further their own goals, and their sexuality is a huge component of their power. The odious Baron Harkonnen is obese and the only visibly queer character in the book (a fact that I’ve already addressed at length as it pertains to the upcoming film). Paul Atreides is the product of a Bene Gesserit breeding program that was created to bring about the Kwisatz Haderach—he’s literally a eugenics experiment that works.

And in this eugenics experiment, the “perfect” human turns out to be a white man—and he was always going to be a man, according to their program—who proceeds to wield his awesome power by creating a personal army made up of people of color. People, that is, who believe that he is their messiah due to legends planted on their world ages ago by the very same group who sought to create this superbeing. And Paul succeeds in his goals and is crowned Emperor of the known universe. Is that a white savior narrative? Maybe not in the traditional sense, but it has many of the same discomfiting hallmarks that we see replicated again and again in so many familiar stories. Hopefully, we’re getting better at recognizing and questioning these patterns, and the assumptions and agendas propagated through them. It gives us a greater understanding of fiction’s power, and makes for an enlightening journey.

Dune is a great work of science fiction with many pointed lessons that we can still apply to the world we live in—that’s the mark of a excellent book. But we can enjoy the world that Frank Herbert created and still understand the places where it falls down. It makes us better fans and better readers, and allows us to more fully appreciate the stories we love.

+Dune’s Paul Atreides Is the Ultimate Mighty Whitey

#white savior#white saviors#white savior trope#tropes#racism#amerikkka#burn hollywood burn#tor#tor.com#dune#arrakis#fremen#harkonnens#superhero syndrome#paul atreides#muad’dib#kwisatz haderach#david lynch#hollywood whitewashing#whitewashing#mahdi#bene gesserit#leto atreides#duke leto#lady jessica#dr. liet kynes#worldbuilding#baron harkonnen#eugenics#science fiction

1 note

·

View note

Text

Half breed. Cons: Half breed.

I, a half breed, went and watched Aquaman, and here are the results.

1. Actual half breeds: A-

There were honest-to-god half breed actors getting paid! To portray actual half breed characters! Beautiful brown babies abounded. I especially died about Aquadad and his chill as fuck native dadness. He does nothing but love and care for people the entire time, raising this kid on his own and waiting for his wife every morning AGH

2. Metaphorical half breeds: F-

Like literally every other fantasy whatever setting, half breed is used as a metaphor for racial politics that never actually fucking acknowledges racial politics or how it might intersect with the additional level of interspecies mixing. At least we didn’t have an eyenumbingly white hero struggling under the metaphoric burden of being two different but equally white things ughhhh. So while there was a visibly mixed main character with a visibly nonwhite dad and a white mother, that’s not where the “half breed” theme comes in. In the film Aquaman is called a half breed and a mongrel over and over in reference to mixed human / Atlantean heritage. Thing is, as far as I can tell, Atlantis has a race and it’s whiter than sin. Seriously, where are the native fish? A bunch of them are literal fish and they’re still coded white, which is a feat.

Here’s a tangent about Atlantis, because it’s bullshit: You get to imagine this fantastical, ancient society of non-humans that will carry your core environmental message, and it’s... what? A patriarchal, overtly eugenicist monarchy, which, far from respecting and protecting the ocean, only ever treats water as real estate or a weapon, and whose chief dude literally seeks to be the ‘Ocean Master?’ That’s lame and they can all go fuck themselves. I was rooting for the actual fish at the end (and that tentacled, primordial Mother of the Deep, oh man).

Anyway, the thing about the half breed as a trope in white media is this: the halfbreed’s entire point is to go on a ~journey~ and become white. Or whatever -- become legitimized by the same violent, exclusionary system that told them they were a problem in the first place, and thereby legitimize the system itself. The halfbreed-as-trope is an insider/outsider that critiques some aspect of dominant (white) culture. In their journey to reconciliation with the dominant culture, that critique is resolved, and whiteness affirmed as virtuous.

Parsing this out: Atlantis is an idealized white first-world utopia (literally, they are white and have superpowers). Human society is being critiqued as not-as-virtuous as Atlantis because they pollute the oceans. Aquaman is considered by Atlanteans a mongrel reject because he’s half human. Aquaman goes on a journey to prove himself Atlantean (via ancient white father-administered genetic screening / Arthurian sword-pulling), defeats the villain, becomes Uber Atlantean bc One True King, stays in ocean and everything is great. Humans are still flawed but ignorant of the larger picture and therefore innocent; Atlanteans are still superwhite superdicks but now no longer metaphorically-racist because they have absorbed the Halfbreed Outsider; Aquaman and his dad as the relateable halfbreeds get affirmed and rewarded with super virtuous white women (there’s a whole other gender critique I havnet even).

Another couple notes on racist tropes in this one: Aquaman letting the Black father die at the start, and that death becoming this deep, character-changing regret that leads the hero to preserve the life of his genocidal white brother and hence his white father’s legacy? That’s more of the same -- Black pain and Native identity being jumping off points on the way to the reaffirmation of white values.

3. Potential for alternative halfbreed reading: B+

By this I mean, if you’re a halfbreed in the audience and you’re trying to filter this (fundamentally white) media through your usual survival goggles, is there enough material to make it worth it? Yeah, I think so. Well... if you can ignore the total absence of women of color at all, and maybe just identify with the halfbreed men (as I do) or the white women (which I dont but still appreciate), then yeah.

I found Black Manta and his dad a really strong alternative to the Finding White Father narrative. That, and Native Dad, were seriously holding down the movie for me. Watching Black Manta take the Atlantean technology and literally make it black (and better) was great. Black manta / aquaman fight scenes were erotic. Aquaman being the only atlantean (?) able to talk to fish opened up possibilities for alternate endings for me. The end fight where he tells all the Atlanteans’ shark steeds to eat their riders was A++, and him riding into battle with that primordial sea titan mama was perfection. She should have destroyed literally everything.

Other than that... Willem Dafoe was fucking useless but had an A+ samurai manbun that was only slightly a pseudo-othering technique. He’s one of the characters that should have been an actual nonwhite Atlantean. Also, I fucking hated hearing the word halfbreed coming from white mouths the entire movie, and then those assholes being saved or spared. Also hated that Aquaman (no, I’m not gonna call him Arthur, that’s stupid) ISNT himself a pirate and actually kills pirates and saves missile-carrying military guys? And then is perfectly cool with sending that junk to the bottom of the ocean?

In conclusion, I like halfbreeds, pirates, and fighty guys but not the patriarchy, and this movie gave me a decent amount to work with despite also sucking a great deal in many respects. B- because of the 3D IMAX potential of Jason Momoa’s pecs.

#aquaman#jason momoa#halfbreed reads righteous#this might seem off topic for this tumblr but this shit is literally why I write fics#no i haven't read the comics and no i dont care

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Crazy Ex Girlfriend 4x01 I Want to Be Here

Stray thoughts

1) Welcome to my first recap of the last season of CEG! I Hope you enjoy this (and if enough people are interested, I might recap the previous three seasons… eventually…) This is both a recap and a first reaction. I haven’t seen the episode yet so I will be writing my thoughts as I watch the episode for the first time. Yay!!

2) Okay, first comment: I love how they’ve changed the titles from “...Josh...” (or Jeff or Nathaniel or Trent…) to “I…”. I think it’s a clear indication of where this season is heading. Rebecca will finally grasp this concept of self-love, self-esteem, and identity. Your life needs to be your own before you can share it with someone, and I hope this is the philosophy that Rebecca embraces this season.

3) I’ve grown to like Nathaniel a lot, but he still needs to continue his journey on this show. He’s made a lot of progress, but the fact that he thinks Rebecca should prioritize him/their relationship over her own mental health and responsibilities and that he may think Rebecca pleading guilty reads as her not loving him enough shows that he still has a long way to go. This whole thing – Rebecca going to prison – has nothing to do with Nathaniel or her feelings for him. Yes, she did throw Trent over the balcony in order to save Nathaniel, but that’s it. Pleading insanity would’ve meant taking the easy way out, which has been Rebecca’s M.O. when it came to facing the music. Until last season, of course. A lot of her decisions were affected by her mental illness, but she truly needed to own up to everything she’d done and take responsibility for it. I get why Nathaniel might not agree with her decision, but he still should’ve stood by her side.

4) Okay, one of the reasons I love this show…

JUDGE: Everybody, just calm down. That's why I brought you into chambers to tell you that I can't accept Miss Bunch's guilty plea. For starters, it wasn't even really a plea. It was more of a speech filled with, uh, irrelevant details that you delivered to this lady with your back to me, and then I find out that you're in a romantic relationship with your actual lawyer, who I'm guessing is also in…

EVERYONE: Real estate.

This is such a beautiful way to deconstruct a trope without taking away from how effective and pivotal that scene was. Yes, as in most movies, Rebecca delivered a speech that moved most of the people in the courtroom as she pleaded guilty. Would this be acceptable in a real courtroom in real life? Obviously not. It was a great character moment for Rebecca, who obviously couldn’t help but have her Hero moment or Grand Gesture or whatever as the protagonists of movies are bound to do so. Of course, she’s not actually in a movie, so her speech, as beautiful and poignant as it was, won’t fly. Let’s not overlook the fact that all the lawyers attempting to defend Rebecca have ZERO experience in this type of cases, which is yet another thing that wouldn’t happen in real life and the show clearly points it out.

5) And I get where Paula’s coming from. Again, Rebecca needed to make a Grand Gesture because she’s still in this movie mindset by which in order to get Redemption you need to make a Great Sacrifice. In real life, it doesn’t really work that way. We find redemption in small – yet meaningful – acts. It’s a long, arduous journey, it cannot be accomplished with one great, over-sweeping act. Yes, what Rebecca did at the end of last season was, indeed, a grand gesture. But by their very nature gestures are merely an indication of good intentions that need to be followed and validated by other actions.

6) “I want to go to jail” “Jail is what I deserve” Let’s see how long this “gesture” lasts... (I’m guessing not long…)

7) Was this… a nipple slip?

Or is that shadowy thingy her fingers/hands?

8) Now, Rebecca and Nathaniel do have a lot in common…

NATHANIEL: It's not a pansy-ass camping trip. It's an intense outdoor survivalist excursion. That's why it's called Death Wish Adventures.

GEORGE: Love that name. Sounds therapeutic.

NATHANIEL: Oh, it is, it is. And for the low, low price of $100,000, I pay this company to beat me up, drive me out to the middle of the woods, and leave me alone to fend for myself.

Isn’t this pretty much what Rebecca is doing with her prison sentence? An over-the-top, uncalled-for reaction to a situation?

9) “I’m not killing myself, George! I’m going on a Death Wish Adventure!” *stabs bag with the machete* OMG the irony!

10) “How did I miss it, Hector?” Because…

11) Josh is basically taking the opposite route…

JOSH: Yeah, maybe I also have a disorder.

HECTOR: What, dude?

JOSH: Yeah, think about it. Okay, those things about Rebecca, they're not the only things I've missed, like, in life. I didn't realize being a priest would be such a bummer. I didn't realize I was dancing at a gay bar for, like, a month. I didn't realize your mom doesn't like it when I whistle in the shower. (…)

HECTOR: Maybe. Or maybe you're a little oblivious, self-absorbed, and need to be more aware of the world around you.

JOSH: No. Disorder.

HECTOR: Or..

JOSH: Disorder. I have one. I wonder which one.

Most of the things he’s “missed” are things that only call for… very basic common sense? But Josh is choosing to take the easy way out. It’s easier to blame our all bad decisions and poor judgment on a mental disorder than to accept the fact that maybe we’re just a big fat dum-dum.

Could he really have a disorder, though? I don’t know.

12) I just love how Rebecca’s cellmate is reading Webster’s Dictionary because why the hell not, right?

13) Oh, this scene…

First, OF COURSE Rebecca took the chance to get the leading role in this number (as opposed being a backup singer like she was in camp, if I remember correctly.) Not only that, but this is actually the first time we’ve seen her sing FOR REAL. As great as EVERY single song in this show is, all of them are “performed” – so to speak – in the characters’ minds. They are not real. The characters are not really breaking into song because, well, that’s just not what happens in the real world. We know that music and songs (and storytelling, to a certain extent) are part of Rebecca’s coping mechanism. So it’s disheartening yet realistic that she’s not actually talented. How hard must have been for Rachel to sing sort of badly?

14) Uh. The phrase “The road to hell is paved with good intentions” just came to mind. How is doing musical theatre – something she’s loved her entire life – penance?

15) This killed me…

And of course, he doesn’t read the first THREE results, he just goes “Ooh! QUIZ!!”

Yes, this will surely solve all your problems, Josh. I mean, who wouldn’t trust the diagnosis offered on a website that also gives you a quiche recipe, right? Sounds legit!

16) I think that Rebecca might have mistaken “penance” with “reward”…

17) And the first musical number!

I truly loved this number, I was watching it with the biggest smile on my face because I was enjoying so much what they were doing here. I mentioned before how I loved the fact that for the first time we got to see Rebecca singing for real, in a real-life context, where everyone is aware that she’s singing and participating in her song. What’s Your Story? is a great blend of that and the typical CEG musical number. Whereas Rebecca is definitely in her own mind, the people around her are pretty much in the here and now of the real world, with very natural reactions to her actions. This is how people would react to someone breaking into song in the real world and trying to romanticize or glamorize things that shouldn’t be, like crime. This is her big Chicago number, yet the criminals in the room, including herself, hardly deserve to be called that. Two shoplifters, a girl whose boyfriend’s meth was found in her car’s glove compartment and a “murderer” who had accidentally killed a teenager while texting and driving. There’s nothing glamorous about this. It’s sad, pathetic even. But of course, that’s only because they, unlike Rebecca, are not good storytellers. And this is how Rebecca is confronted with the reality of her “grand gesture.” She thinks she’s doing this great sacrifice because she’s decided to do her “penance” and spend some time in jail even though the judge did not accept her plea. To the others, she’s just a privileged idiot who thinks this is just a game and who is wasting their time.

Side note: I love the blink-and-you-miss-it tidbit with the two shoplifters and their respective sentences for the SAME crime… the difference being their skin color. And I love how the white lady simply apologizes and walks away.

18) Bless Hector and Heather!

HEATHER: Look, Josh, I really respect your search for self, but these are actual disorders people suffer from, and you're treating it like you're just, like, identity shopping.

HECTOR: Yeah, it's kind of gross.

So much YES. I love this show.