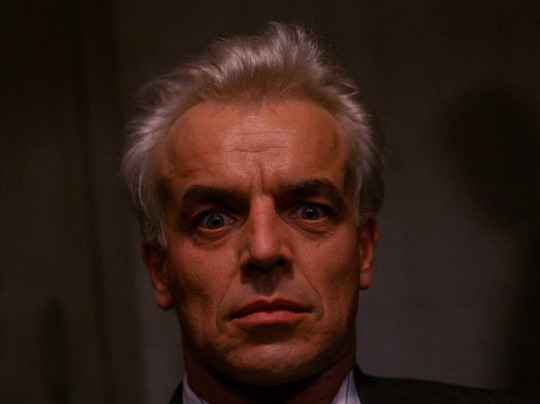

#also so many things are making me feel like this image of leland palmer but im just not. idk

Text

going into the tags of a post about character x and saying “this is so character y”

#well if i wanted it to be about them then i would have made it that way#also so many things are making me feel like this image of leland palmer but im just not. idk#i know theoretically i can speak my mind on my own blog on the opinion site#but if i end up opening a whole can of worms that causes problems for a while i would rather just. complain to my friends in private#robin rants

22 notes

·

View notes

Note

twin peaks but it happens in 2010. laura palmer have iphone etc etc

this ask has been haunting me since i saw it last night oh my god okay okay so

i wanted to lead with laura being an influencer but no one was quite influencing in 2010 yet. but the point here being that i think she posts a lot online and cultivates her online image very carefully (very soft, carefree, excited teenager) and has a LOT of followers on everything and always gets a ton of likes. bc it's laura, she's so beautiful and special and popular, of course everyone is following her, of course everyone is liking all her posts to get a piece of her

she has a twitter (laurapalmer93) where she posts a lot of pictures with little captions like.......'morning donuts at the diner!!' with a picture of the donuts and a milkshake or a Coffee To Be An Adult, 'can you believe this guy? <3' with a picture of bobby making a face (or even.........dare i say it...........doing the dougie), a picture of donna and james with '<33333333' (modern emojis were just getting really big then but i myself was not a big emoji user in 2010 yet, so neither is laura), 'don't tell ;)' with a picture of her holding a cigarette (of course everyone still smokes in the high school bathrooms).

one time she gets away with posting the lyrics to if i die young by the band perry (IF I DIE YOUNG! BURY ME IN SATIN! LAY ME DOWN ON A BED OF ROSES!) (FUNNY WHEN YOU'RE DEAD HOW PEOPLE START LISTENING!) bc it's a popular song. it raises a few eyebrows but it's a song and it's laura. how seriously do you take teen angst, even among your friends? that's just what laura does. what's there to really worry about, huh? (the song was released in may 2010 but let's say the lead up to her death is in 2010)

on facebook she posts a lot of volunteer stuff. school dance photos, which she helps organize. buy some cookies to support the french club!! she's very involved with student council, and she organizes the group halloween costume. her facebook is filled with photos of her with other people, but not really any of just her. she doesn't post a lot of statuses, but they're usually about homework or tests or 'feels like summer!' towards the end of the school year. she's friends with her parents. she definitely takes ap classes.

she has a private vent twitter (lostinthewoods) with zero followers that she uses as a diary bc she thinks it'll be safer than having it physically written down. her childhood lisa frank diary with the tiny lock and glitter gel pens that she kept in her bed post went missing, after all. her vent twitter is filled with sooooooo many tweets bc this was still the 160 character limit days and she would just post and post and post especially late at night. (she definitely has string lights in her room.) she is a MASTER of using her phone with no one seeing -- she has the layout absolutely memorized. she was only caught texting in class once and of course the teacher let it go.

bob/leland finds her passwords and breaks into the vent twitter and leaves her horrifying tweets she sees later, instead of the back and forth they have in the diary and leland ripping the pages out.

i think she has a third twitter, for sex, but i'm not sure if that tracks for the time period? (snapchat wasn't a thing until fall 2011.) or like a forum sort of thing? i think it's still super easy for laura to sneak out, even in an increased security camera world. there's still a lot of stress on the, yknow, ~secret unexposed underbelly of the world especially in a time of more eyes on everything~ in the 2010s.

meanwhile, james posts music a lot on facebook, and also acoustic covers of songs. like. yknow. HEY SOUL SISTER. donna loves the original pusheen stickers. they record the picnic video on her flip video camera. mike loves icanhascheezburger, and he jailbreaks his phone. audrey gets really into audrey hepburn quote posting, Aesthetic France, black and white photos, berets, has a photography phase and carries and actual camera bc it's Vintage. she's an early tumblr user. no one else in school has a tumblr yet, so she feels very cool but also very lonely about it.

harry has very little understanding of social media, however cooper is very into all social media, he finds it delightful. he enjoys a good cat video. he looks through all of laura's photos, her tweets, facebook videos, and i think there's, honestly even more of a feeling of tragedy bc of how much more physical evidence there is available of laura's life, lingering fingerprints, last tweets, last posts, passwords to put in and information to see, cold blue computer light, the even worse voyeurism in people expecting so much of your life to be online, in watching it play out online, in the image laura created for herself online to be the person people expected

donna rereads laura's twitter in the dead of night, just over and over again. goes back through their texts. so much of grief has become so much more public with social media and using it as a teenager, and there's this back and forth in donna of not posting anything and then posting the most miserable statuses about losing her best friend.

i know i should get deeper into the investigation but i keep thinking instead of how laura definitely gets a 20/20 special. it's probably definitely called 'the secret life of the american teenager.' (bc there was that show on at the time with the same name) elizabeth vargas visits twin peaks, is appropriately grim, there's a lot of b roll of the town and the woods but without the grace of twin peaks' cinematography. they play up the creation of a narrative big, as they always do on 20/20. the revelation of her 'double life' is at the halfway mark and simultaneously not discussed enough and overestimated. 'laura palmer was your average, everyday teenager -- she liked horses. cats. she got good grades, was homecoming queen, had a boyfriend on the football team. she volunteered on weekends. she had her whole life ahead of her. or was there more to the story than anyone knew? was there a dark side to the all-american girl?' oh, it's agonizing. the trailers play up a lot of potential spooky woods stuff that isn't followed through on in the actual episode.

now 20/20 prides itself on getting the story right, so i feel like it's.........i feel like they have to say it's leland at the end (and they definitely never get into anything about bob). but i also think, for some reason, it could easily have a 'we never found the killer' ending. especially re: s3........the thing is, i feel like laura's death particularly is the kind of thing that shows up on 20/20, but the rest of the circumstances would've ended up on like the unsolved mysteries website (the last revival ended in 2010, before the netflix reboot in 2019) (especially with WELL OUR FBI AGENT WENT MISSING). and there's so much online to put together in a website about it, there's so much for people online to dig into who have never even been to twin peaks, to think they know a town and the people in it and the girl who died even if it's just literally THE MOST DISGUSTING VOYEURISM IN THE WHOLE WORLD i just think there's such a. horror in that. people have the most, just, enraging takes when they get involved in a Murder That Happened Somewhere Else. people thinking they alone can figure out a mystery they've never seen, they can of course see something no one else has. and it's different than the people in the town ignoring it -- i think a lot of the secrets in twin peaks stay the same, no matter the time period, so of course it's still, a terrible dying town killing the people in it, maybe even quieter than it is in the original, some new infrastructure but old buildings, not all of them occupied anymore, ANYWAY -- like of course yes people in the town ignore the same amount they did in the original, all small towns bury things. but just bc the town itself isn't paying attention doesn't mean that some rando online is going to know more, no matter how much they think they will. there's like an entitlement to details of a murder, an I Must Be The Hero, The Savior, bc i'm on a fucking reddit thread about it

now i have zero (0) idea of how medical science and forensics work, but i have to assume there have been some advancements in the field between 1989/1990 and 2010/2011. the town still rushes the funeral, but would albert have been able to find anything else sooner? what is it he would have found to point to leland sooner? oh........dna testing, maybe? would he be able to find out about leland right away? there's more of a sense of urgency, maybe less of a slowness between events, even more of a shattering horror. maybe leland goes missing in an attempt to cover things up. hmmmmmm.

final note -- cooper gets called mulder as a nickname bc the x files happened as a show in this universe.

#lulu talks about twin peaks#THIS HAS CONSUMED ME. I HAVE TO PUT IT DOWN. THANK YOU SO MUCH KAM I HAVE LOVED THIS

77 notes

·

View notes

Text

Thoughts Roundup - Twin Peaks: The Return, Part 17 & 18

“It is a story of many, but begins with one - and I knew her. The one leading to the many is Laura Palmer. Laura is the one”. So said the Log Lady in her iconic introduction to the first ever Twin Peaks. Just as Laura became a conduit to the town and its people, all these people led right back to Laura Palmer. She was at the end of every road, her photograph lived in all the town’s buildings, and even decades later in The Return, her face emerges slowly from the trees during the opening credits. What was about her always will be about her, and that cannot be changed.

Everything in these two hours presents easier answers than Laura does, but that has always been true of her - she’s the one still filled with secrets. There is something of a heartbreaking, world-changing realisation in this finale, the kind of realisation that the patrons of the Roadhouse had when Maddie Palmer was killed. There was no way for them to know what had happened, but they felt it. Twin Peaks has always been about feeling rather than knowing. It feels like falling, like the world is being rocked from its axis, and it is the show at its most powerful.

There is a common idea in Television Finales that the last episode is where something concludes - where the world, for better or worse, is put to rights. And when this finale feels like it’s heading towards that, it takes a violent u-turn and reminds us that Twin Peaks has never been normal television.

The hellish final fight between Freddie and Bob is visually very Lynchian, yet there is an unusual amount of literalness and resolution to it. Just as Freddie punches Bob through the floor, the BobBall (there’s gotta to be a better word for it) rises again, a terrifying and unstoppable anthropomorphised nightmare that violates our screen, bursting from it with visceral and unknowable force. When Bob crawled over the couch in the Palmer house and came directly towards the camera, that was an invasive and affective moment, but this is that moment amplified to unbearable measures. But he still is vanquished, broken into small pieces and absorbed through the ceiling of the office. And after everything Doppelcoop had been through, after all the vicious, hardened monsters he’d come up against - it was Lucy who killed him with a single gunshot and sent him packing back to the black lodge.

Lucy gets her heroic moment (She has always been an unsung hero, a smarter-than-you’d-think character who, despite struggling with mobile phones, still gets things done when she needs to) and even though all of these moments feel suspiciously neat and tidy, it’s hard not to be delighted by them. It turns out Naido is Diane as many suspected (and we finally learned earlier that Judy is the ancient evil being referred to in The Secret History of Twin Peaks, and most likely the experiment we saw in the box in New York) and her and Coop’s embrace is satisfying but again, very convenient. And then - right on time! - here’s Gordon, Tammy and Albert! And Bobby, The Mitchum Brothers, James and Freddie! They’re all here, all your favourite characters! And at any moment it almost feels like someone is about to come in and say “Coop, this telegram came for you - your old pal Harry Truman says ‘Coop, i’ve sent you a piece of cherry pie and a coffee, and i’ll be home soon. Hee-Haw, and Merry Christmas!’”. It feels unreal and purposefully kind of artificial. But something tells us this is off.

After interacting with Naido/Diane, Dale looks as though he’s almost regressing back to who he was before waking up. But instead, he’s remembering something. He’s met her before, in another world. His moment of realisation echoes throughout the scene, as a transparent and ghostly image of Dale’s face dominates the frame and the rest of the action occurs, visually, inside his head. He remembers something, and we begin to suspect that none - or all - of these worlds are real, including the one we’re in now.

Earlier in the episode, Cooper commented that the time 2.53pm is 2+5+3 which is “10, the number of completion”. The clock in the sheriff’s office cannot move on. It is stuck between 2.52 and 2.53. Time moves strangely and completion cannot be reached. There is something missing, which the transparent Dale comments on: “We Live Inside A Dream”. He also says that past dictates the future and that things will change, and suddenly, everything does start to change. As Dale will soon change the course of history, the moments in the office begin to feel unreal. Their current existence can’t exist as it does if what happened in the past is undone. The dream will soon be shattered, and it’s already starting to fracture. Is it future or past? One and the same.

The past dictates the future, so if the past can be changed, then there are infinite ways that the story could turn out. There are versions where Laura was killed, versions where she lived, versions where she was never born in the first place. The version that we know is a dream inasmuch as it is just one version of events. It’s a version that was directly affected by Bob because he killed Laura. And so, as the sinking feeling begins again, the lights go out in the office and Dale, Gordon and Diane find themselves removed from the office and walking through darkness. Is this what it’s like to go missing in Twin Peaks? Is this what it was like for Jeffries or Desmond? And are the people in the Sheriff’s office still there, wondering just where the hell those three went? Or are they non-ex-ist-ent?

The trio find themselves in the basement of the Great Northern hotel. The door to which Dale has the key is maybe the final and most important precipice that he pushes himself through. Though he has been guided by The Fireman, this decision is what changes everything, and it’s a decision that we now know was not the right decision. It’s so painful, in hindsight, to see Dale so plucky and optimistic going into this. He so selflessly wants happiness for everyone, and not only that but wants to remove pain that exists now and has existed seemingly forever. He wants to be the ultimate hero, and once he’s in 1989 and writing himself into Laura’s history, he begins to act as a version of The Fireman. Jeffries has sent him here, after telling him where to find Judy, (”Say hello to Gordon. He’ll remember the unofficial version”), and at first Laura sees him hiding and screams. It’s an absolutely ingenious retconning of events, and visually it is seamless. The events that we see from Fire Walk With Me feel and look like a distant dream that Dale tries to wake her up from. When Laura stumbles through the woods, she sees Dale, looking tall, benevolent and completely out of place, much like The Fireman did whenever he appeared.

As Laura Palmer’s theme chimes in, and as you hear her voice again, sounding so young and so sweet, it is overwhelmingly moving. You know that he is here to save her, and it is the bittersweetness of wishing this could happen and knowing that it cannot that makes you ache. As he lead her away, her plastic-wrapped corpse disappears from the beach, and Pete Martell finally gets to go fishing. It is almost too much to fathom, but as Dale leads her through the darkest woods, through complete silence, we know that it cannot be that simple. The sound the Fireman played back in Part 1 finally triggers something, and Laura is gone again, her agonising scream shattering our hopes. Laura is gone. She hasn’t been saved, she has been entirely relocated, and Sarah Palmer - or Judy, who seems to live inside her - feels this. The smashing and stabbing of Laura’s portrait by Sarah is violently ugly, and the editing as her strikes are reversed and chopped up is masterful. Someone has stolen her Garmonbozia.

When Dale makes it out of those dark woods, he’s in the Black Lodge again, and this is where things start to look familiar. Laura’s whispered secret causes Dale some confusion, and she is ripped out of the lodge and placed in another time and another place. Her whisper is something we will never know, but it isn’t something Dale is happy to hear. “You can’t save me”. “You killed me”. “I’m in Odessa”. Who knows - it could’ve been any of these things, or none of these things. The point, really, is that we don’t know. We almost feel as if her words would somehow answer a cosmic question that’d make everything fall into place, but would they really? What could she say to make any of this okay? I think Dale’s reaction - an incredulous “huh?” - says that he is realising what we are all realising throughout this episode. Some awful, horrible truth. And even still, he listens to Leland - “find Laura”.

Outside of the Lodge at Glastonbury Grove, it’s hard to tell what is real in the darkness of the woods. Diane is there, and Dale and her confirm to each other that they are their real selves. But by this stage, we don’t know who they are anymore. This is further obfuscated by the purposeful lack of time that we spend with Dale and Diane together. They are suddenly driving somewhere far, far away from Twin Peaks - 430 miles to be exact - to the place that Doppelcoop crashed and was nearly taken back to the lodge at the top of the season. And it’s here, next to crackling electric pylons that physically resemble the owl cave symbol we’ve seen time and time again, that Dale and Diane go through the final door. (Speaking of final doors, i’m so delighted to see a version of Coop/Dougie returning home to Janey-E and Sonny Jim. It was a long time coming, but it’s nice to see that sometimes you really can go home).

They know things will be different on the other side, but don’t they already feel different? We have been entirely disconnected from the rest of the characters in the finale, and that makes wherever Dale is seem completely isolated. The last of Dale as we know him is gone after one final kiss, and the blue skies turn into the darkest of nights once again - we are in another place. In this other place, Dale and Diane are still themselves, but they’ve lost something. Dale is colder, slower and quieter. Diane seems to be in pain again. At a motel, she stares out of her car window and sees herself emerge quietly from behind a wall. Perhaps this was a warning to her to get away. That the identity of Diane would be dead by the morning if she stayed. She stayed, and the world changed.

Nothing has ever felt as wrong as their sex scene feels. Dale is emotionless and still throughout, not even reacting as Diane claws at and mashes his face; she looks towards the ceiling, desperate to be far away. It feels like they are becoming other people, they are slipping away from who they are into entirely different roles. It feels sickly and uncomfortable, as if the more they try to get closer, the further apart they drift. They aren’t themselves anymore.

She is gone when he wakes up, and in this other world they’ve passed into, she has fully accepted her identity as Linda. It is a continuing theme from Lost Highway, a nightmarish concept of finding out that you are not who you thought you were. Dale doesn’t accept that he’s Richard, and is confused by the letter he finds naming him as Richard, and signed Linda. Dale is holding on for dear life, but even he has to acknowledge that outside, the motel is not the one they entered last night, and the car he gets into is not the car they drove last night - if it even was last night. Identity is a big theme in Lynch’s work, and Dale bases his identity on being an enthusiastic, kind and hard-working man, but now he is being pushed further and further away from that until he is literally somebody else.

Dale seems to drive without direction. He’s not his usual determined self, and not a note of music is heard now. He drives through a flat, faceless but realistic looking town. The banality receives a jolt of terror, as a giant “JUDY’S” sign makes the place feel manufactured again. Inside the cafe, Dale is different. He doesn’t enjoy his coffee, he is far more violent than usual when dispatching the three men in the cafe (though gotta admit: they deserved it), and there is a spark gone from his eyes. He’s Dale minus something. He leaves Judy’s with his information on where to find “Laura” and waiting outside Laura’s - or Carrie’s, as she’s known in this reality - is that same buzzing telephone pole that was found in the fat trout trailer park. It is a symbol, a warning, a normal object repurposed as a symbol of something evil and dangerous. It is directly outside her house. Dale recognises this but continues.

There is such pain in seeing Laura not as Laura. She has disappeared from one reality to be thrown into one manufactured by Judy which sees her as Carrie, someone with a great deal of pain inside her too. Nervous and unsettled, she reacts with a stuttering dread to the name “Sarah”. She is on the verge of a realisation, even if she brushes off being told by Dale that she is a girl named Laura. He seems to have such a lack of control in this scene. He asks rambling, untidy questions that don’t get him anywhere. He has little sense of authority, and is easily confused by what he learns. He is Richard in this timeline, or at least, he was supposed to be. He’s holding onto Dale but he’s not as strong as he was. He wants to wake Laura up and to take her home, but what does he expect from that? Does he really think Laura can be saved, and Judy defeated? Would Laura really want to return home? Dale doesn’t think of this because he’s fixated on fixing things. But he ruptured something when he went back to 1989.

It’s hard to say what is more troubling in Carrie/Laura’s living room: the corpse, or the figurine on her mantle of the white horse. “Woe to the ones who behold the pale horse”, we were told by the Log Lady. Woe to Dale and woe to Carrie/Laura. We have descended fully into this netherworld with them and cut off contact with what is familiar. The focus that they get in this last episode begins to hint that this is it. As the minutes go on, we know there cannot be an encompassing closure. There are threads and stories that won’t be tied off. You can think of these last moments as a detour, but they’re a detour that close the story in an eternal, figure 8 loop. Just as the first ever episode of Twin Peaks shifted gear with Dale driving into the town, the final parts close with the same journey. The first time, he’d gone to save the memory of a girl named Laura Palmer. The second, he’s come to bring that girl back to life.

And so they drive, and drive, and drive. She is happy to be leaving Odessa, to be far away from Judy’s and White Horses. She doesn’t know exactly what to expect, but she accepts the ride. The dark night ahead of them is the longest yet. The headlights on the road linger for so long. They are leaving Odessa on an odyssey through the lost highways and into woods of Laura’s memories. The blackness becomes all encompassing, this becomes their dark night of the soul. We are going deeper into this world and deeper into Laura, and we wait for any sign that she is who she was. She looks out the window and the douglas fir trees fail to trigger anything for her. They pass the Double R diner - the lights are off and the streets are empty - and still nothing.

This isn’t home anymore. It wasn’t home when Laura was alive, either. It was a trap for her, just as Odessa was a trap. Twin Peaks was not a dream, but a nightmare for Laura. It was her dream - her nightmare - that they all lived inside. And Dale fails to recognise this and now he’s broken it. He wants for that to be erased and replaced with something better, but if she is erased, then how can it all exist? The Log Lady once said: “When this kind of fire starts, it is very hard to put out. The tender boughs of innocence burn first, and the wind rises, and then all goodness is in jeopardy.”. Dale is a hero for trying to put that fire out, but Margaret was right: goodness is in jeopardy, and it isn’t easy, or possible, to save it this way.

At the house, Dale bumbles through questions to the owner. No, there’s no Sarah Palmer here. No, we didn’t buy the house from her. The answer that we do get says so much: her name is Alice Tremond, and she bought the house from Mrs Chalfont - both names given to a woman who existed both in our world and in the black lodge. Though she was largely benevolent, this hammers home that this isn’t the Twin Peaks we know. Something is very off. We are in their house now. Is this the same woman who will one day give Laura the painting of a doorway? There is too much to comprehend in these questions, and back on the street, it all washes over Dale as he is wounded in confusion. He tries to hold onto some semblance of reality, like a dream upon waking. But he is powerless again - he hasn’t delivered Laura home, he hasn’t saved her, and home doesn’t really exist anymore.

The curtains are torn down and the realities crash into one, the dream has ended, and now we face a world where he and Laura possibly don’t exist. By taking Laura from the woods and delivering Laura back here, has he killed the memory of her? The question that strikes Dale is “What year is this?”. He staggers around in confusion; Laura looks down, beginning to tremble. She doesn’t know what year it is. She is on the cusp of a realisation, of a memory, of this dream she is in being shattered as the other one was. It is all too much to bear, until a familiar sound sends everything crashing to the ground.

The sound is the haunted, ghostly voice of Sarah Palmer calling “Laura?” from the house. It isn’t just her calling the name - but the exact clip from the first episode of Sarah calling upstairs to Laura. A memory, a fragment of who she was and what happened to her, is calling out from some deep, dark and distant world. And like Doppelcoop’s ominous “:-) ALL” text message, the sound lights a fire and and she remembers everything. She does the only thing she can do, and we hear maybe the most famous, haunting and agonising sound in all of Twin Peaks: the primal scream of Laura Palmer.

Dale looks in fear, in shock. He has got what he wanted, but he’s realising what he wanted is not what is right. A pain that has lasted forever and will last forever is reawakened in her. Dale can go back and try to change history, and he can destroy the timeline as we know it: but he cannot undo the pain and the fear. Laura was killed. He tries to kill two birds with one stone: to save her from death, and then bring her back home. But she cannot be brought back home without remembering what happened to her. This kills her all over again. It is a paradox of anguish, a full circle that is destined to loop forever. Her scream shatters the dream, and the lights in the Palmer house suddenly shut off. She has broken something. And before we see where they go next - to non-existence, back to the start, or wherever else you like to imagine - it cuts to black, the only sound lingering is the echo of her scream. It will always echo. It will always have been, and it always will be.

As the credits begin to roll, Dale and Laura are in the Lodge again, and she is whispering a secret into his ear in slow motion. Fear and confusion are written across his face. He is realising she cannot be saved. Perhaps he is realising his attempts to fix things have made them worse. He has shattered her dream, the dream of Twin Peaks, and as a result undone his reality as well as her’s. He has trapped himself between worlds. He longs to see, but he has never been able to wake up fully from his own dream. He has never been able to stare reality in the face and realise that he cannot save the world. If Twin Peaks has been Laura’s dream, it makes it no less real. It all happened, she saw it all unfold in her dreams, she saw herself sacrificed and much later, she saw Bob finally defeated. But then Dale undid this.

It is impossible to think of this all in literal terms. I don’t think any of it was invalidated, and I don’t believe that it was all as simple as a literal dream. I think instead that we’ve been privy to a version of events and everyone has played inside that. Maybe that version was Laura’s dream and that’s the one that should’ve been. The Return has asked us repeatedly to question who the dreamer is, to challenge everything we are seeing, because nothing is ever simple, and nothing is ever really finished.

Everyone believed The Return referred to Dale’s return to Twin Peaks. It didn’t. It referred to Dale trying to return the world to how he believed it should be - a place free from the abuse and murder of Laura Palmer. And he’s right, we shouldn’t live in a world where that kind of thing happens. But ultimately it did happen. Dale is powerless and misguided, because instead of learning from past trauma and building a healthy road away from that, he attempts to drive back down that dark road and delete and invalidate the existence of that trauma. That can never be done. You cannot remove it without removing everything along with it. Where he should’ve focussed on dismantling the evil going forward, he focussed on undoing the damage.

I don’t know if Laura will ever find peace in this, or any dream. I don’t know if Dale will, either. It is a painful realisation that home will never be the home you thought it was, and that you cannot go back and recapture what once existed. And the ending is certainly a bleak one that argues that we get caught in desperate cycles of trying to control and fix our pasts and futures. But what it also applauds is thorough and dedicated goodness, as well as the benefit of attentiveness and listening. Dale was goodness incarnate, but he didn’t listen as he should have. Perhaps we can make things better, perhaps we can help others and overcome evil. But we have to listen to do that. We can’t strip away the experiences of others, but we can listen and learn from them. The reason the ending was so dark was because of Dale’s flaw - that he didn’t learn this.

The Return has been about learning and about listening. It is a testament to understanding and appreciating the world around us, and loving each other enough to hear what they tell us. We shouldn’t give up. We should pay better attention. We should listen to what those in pain tell us. We should do as the log lady told us and listen to the trees blowing and the river flowing. We might never find answers that will satisfy us entirely, but we can pursue these questions, we can behold the mystery, and in this, we can try and make things better. And if we listen and look closely enough, we might just find a light shining in those darkest of nights.

#twin peaks spoilers#long post#twin peaks the return spoilers#dale cooper#david lynch#twin peaks#twin peaks the return

257 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Ep. 8 Of #TwinPeaks Is David Lynch's Purest Marriage Of Television And Video Art

Adam Lehrer , CONTRIBUTOR

It’s hard to describe how inestimable an impact David Lynch had over me when I first saw Mulholland Drive as a 14-year-old. Something I’ve been discussing with fellow artist friends of mine is the fact that the art that changed our lives the most and still carries the most weight over our own sensibilities is the art that we were exposed to very young, maybe even too young to fully understand what it is exactly that you’re viewing. I developed a taste for disturbing aesthetics at a very young age; when I was about five or six-years-old, my cinephile father would have “movie nights with dad” when my mom would go out with her girlfriends, and he would let my brother and I watch watch Ridley Scott’s Alien, James Cameron’s Terminator, and/or Paul Verhoeven’s Robocop when I still should have been reading children’s books (and boy am I thankful for that).

That early exposure to art, whether it be John Carpenter films, or Brian DePalma films, or Bret Easton Ellis novels, or my favorite music (Wu Tang, Lou Reed, or Marilyn Manson), is still the art that I think about and gravitate back towards even after decades of being exposed to just about everything contemporary art, cinema, literature, poetry, and popular music has to offer. But watching Lynch’s Mulholland Drive for the first time feels like a monumental point of epiphany in my life. A point where I thought to myself, “Maybe I want to create stuff when I grow up.” I had no idea what Mulholland Drive’s fractured plot meant, but its images left me confounded, and fascinated. I loved the dreamy, hallucinatory Los Angeles Neo-noir stylizations of its setting. I had never felt more terrified than when I first glimpsed that monster lurking behind the Winkie’s diner.

That film made me blissfully aware that cinema and art could be a simultaneously erotic, horrific, and thrilling experience. I knew how powerful art could be, but Mulholland Drive gave me my first taste of the sublime. Since then, I’ve been a David Lynch fanatic. I’ve watched all of his earlier films, binge watched Twin Peaks over and over (finding myself asking new questions each time), wrote college essays on Eraserhead and David Foster Wallace’s article that documented Lynch’s process on the set of Lost Highway, have searched out all his early forays into video art, have found merits in his more oft-overlooked output in advertising (his 2009 commercial for Dior is Lynch at his funniest), and have read countless analyses on the man himself and his cinematic language.

So, when you read what I’m about to say, know that I do so with much hesitance, consideration, and ponderousness: the eighth episode of Twin Peaks: The Return is the piece of filmmaking that Lynch has been building towards for his entire career. It is a singular cinematic and artistic achievement, and the purest distillation of the multitude of ideas and concepts that live and breathe in the Lynchian universe. I believe that years from now we will be looking upon this single episode as one of, if not the single most, defining artistic achievements of Lynch’s unimpeachable career. Bare with me.

Aesthetically, episode 8 would leave a powerful impression on even the most half-hazard of David Lynch converts. A hallucinatory, nightmarishly kaleidoscopic consortium of images of blood, flames, fluids, and demonic figures spews towards the viewer while Krystof Pendrecki’s tortuously atmospheric soundscapes underline the episode’s inescapable atmosphere of existential dread. Episode 8 is an hour long work of experimental video art, no doubt. But if you have been paying attention to this season of Twin Peaks and you know enough about the mythology of the show and know even more about Lynch’s artistic interests and visual touchstones, then you know that this episode was no mere act of meaningless artistic overindulgence. In fact, this was Lynch telling the origin story that set the entire series of Twin Peaks into place.

This was the origin story of BOB, the demonic force that forced Leland Palmer to rape his daughter for years and eventually murder her in Twin Peaks’ initial 1990s run. BOB, we learn in episode 8, was forged from the the United States' earliest forays into nuclear bomb testing. BOB was already the perfect metaphor for mankind’s capacity for cruelty, depravity and evil, and becomes an even more powerful metaphor now that we know his nuclear genesis. Any Lynchian fanatic will rave to you how delicious this notion is. What David Lynch has done, and in many ways has always been trying to do, is to create a piece of pure atmospheric video art that also works as a classic piece of narrative storytelling. In this episode, Lynch has perfectly located a zone in which vague and aesthetically menacing imagery also serve as clear and precise storytelling and, like the best cinema and storytelling, illustrates a metaphor for modern human existence. While Eraserhead, Mulholland Drive and Inland Empire, Lost Highway and Blue Velvet utilize video art aesthetics, they are also pieces of storytelling with easily identifiable stories if you look for them (well, maybe not Inland Empire). Episode 8 of the return of Twin Peaks is a mostly dialog-less piece of distorted, haunting images. It is art. But it also still tells a story. The story of a television series no less! This is all the more impressive in that television as a storytelling medium is the most reliant on expository dialog and over-crammed storyboarding.

David Lynch pays heed to the form while mainly utilizing the language of pure image. Who needs a script, and who needs dialog, when you can see that delectably menacing, fascinating and torturous world of Twin Peaks from inside the actual head of David Lynch? Episode 8 was the truest portal to the imagination of Lynch that has yet been put to screen.

I’m sure there are more casual David Lynch fans that are growing impatient with the restrained, at times glacial pace of this new season of Twin Peaks. I however have understood what he’s been doing this whole time. He hasn’t just been making a television season, he has been commenting on the current importance of television in our culture. Television has replaced cinema at the heart of cultural conversation for many reasons. Partly, this has been a result of the groundbreaking work that has been done in television over the last two decades: Twin Peaks, The Sopranos, Mad Men, The Wire, and more recently, The Leftovers have all expanded the possibilities of what people believe can be done with the form. There are also financial concerns: as major film studios continue to spend their whole wads on sure thing blockbuster action and superhero films, auteur filmmakers have had harder times getting their films properly funded. Cable and streaming television services like HBO or Amazon however have the means to give filmmakers the funds they need to realize a vision, and indie filmmakers have resultantly flocked towards the small screen.

Television’s prevalence has had connotations both positive and negative on culture. The negative, in my opinion, stems from its causing people to no longer be able to get lost in a pure, imagistic cinematic experience. Even the best shows are still mainly concerned with story and dialog, whereas cinema is about mood, atmosphere, and aesthetics. When Twin Peaks premiered in 1990, Lynch and co-creator Mark Frost (a television veteran) were very much interested in marrying the Lynchian world with the conventional tropes of television: serial drama, mystery, and even soap opera. Throughout its first season, it worked beautifully. Both Lynch aficionado cinephiles and mainstream television viewers alike were captivated, and the series was one of the year’s top-rated. But after the second season revealed Laura Palmer’s killer to be her demonic entity-inhabited father Leland far too early during its run, Lynch’s boredom with the constraints of television grew apparent. The show starts to feel like a standard nineties television show, albeit one with a quirky plot and wildly eccentric characters. Lynch mostly dropped primary showrunner duties to focus on his film Wild at Heart only to come back for Twin Peaks’ stunner of a series finale, when the show’s protagonist FBI Agent Dale Cooper travels to the mystical red velvet draped alternate universe of the Black Lodge, and eventually becomes trapped inside that Lynchian hellscape while his body is replaced with a doppelgänger inhabited by the demonic entity Killer BOB and set out into the world.

In the Black Lodge, Laura Palmer tells Cooper that she’ll see him in 25 years, and that's exactly where Twin Peaks: the Return starts off. It was apparent from the premiere episode of this new season of Twin Peaks that Lynch is benefitting from a new TV landscape in which Showtimes has awarded him full creative control over his product, and he’s directing all 16 episodes of this new season. Also, it’s quite obvious that the technological advancements over the last two decades have enabled Lynch to fulfill the fullest extent of his vision. Twin Peaks: The Return is a much purer marriage between narrative driven television melodrama and Lynch’s hallucinatory experimental video cinematic language. That first episode barely spends any time in Twin Peaks, but spends plenty of time with Cooper in The Lodge. There are some truly unforgettable images in that first episode: a demonic entity appears out of thin air in a cylindrical orb and viciously attacks a young couple having sex, a woman’s corpse is found on a hotel bed with most of her head missing, and who can forget Matthew Lilard, perhaps the newest victim to be inhabited by Killer BOB, in a jail cell accused of murder while Lynch moves the camera from cell to cell until we see the horrifying silhouette of BOB himself in high contrast red and black ghoulishly smiling? But at the same time, Lynch is able to move the plot forward in ways that should be familiar to all television viewers; through procedure, dialog, and plot device. Lynch is still working within the confines of television, but has peppered the narrative scenes with unforgettable imagery. It’s been almost as if he’s been subtly preparing us, the viewers, to not just respond to what we normally respond to in television: story, story, and story and dialog, dialog, and dialog. And to slowly reacquaint us with the thrilling experience that can be derived from watching a set of shocking, beautiful, erotic and terrifying images move along in a sequence on a screen.

And episode 8 of this new series is the pinnacle of this new body of work, and very possibly of Lynch’s career at large. The episode begins similarly enough, with evil Cooper escaping from jail only for his escape driver to attempt to murder him out in the woods. And that is when Lynch kicks it into overdrive. As evil Cooper’s body is bleeding out, a group of dirtied and horrific men called 'The Woodsmen' start picking over his body and smearing themselves in his blood, with Killer BOB himself appearing and apparently resuscitating Cooper’s lifeless body. And then, Lynch proceeds to tell BOB’s, and quite possibly Laura’s, origin stories through a 45-minute nightmarish experimental video art piece. The NY Times has called this episode “David Lynch emptying out his subconscious unabated.” That is totally accurate, and there has never been and most likely never will be an episode of television like this ever again. This episode was video art, but it was also still television, and it also served as a piece of and critique of cinematic and television languages. Allow me to explain.

Episode 8 functions in a way similar to that of the video art of Janie Geiser. Without any knowledge of the world of Twin Peaks or the themes of the Lynchian universe, one could admire this piece similarly to how they would admire the experimental video art of Janie Geiser, and in particular Episode 8 recalls Geiser’s film The Fourth Watch in which the artist superimposed horror film stills within the setting of an antique doll house. Episode 8 uses that same nightmare logic, but empowers it with the budget of a major Cable series. There are also similarities to scenes in Jonathan Glazer’s brilliant Under the Skin when the alien portrayed by Scarlet Johannson devours her male prey in a grotesque nether realm. And perhaps its greatest antecedent is Kubrick’s Big Bang sequence in 2001: A Spade Oydyssey, and in many ways Episode 8 is the hellish inverse of that epic sequence. Like the Big Bang, episode 8 tells an origin story of a world created by an explosion, but instead of a galactic explosion, Killer BOB and his world of evil were born of a nuclear explosion. Brilliantly, Lynch believes that Killer BOB was birthed by man made horrors, going back to something FBA Agent Albert Rosenfield said in the original series about BOB being a “manifestation of the evil men do.” Indeed, in Episode 8 Lynch brings us inside an atomic mushroom cloud set off during the first nuclear bomb test explosion in White Sands, New Mexico in 1945. As the camera enters the chaos and giving view to one horrid abstraction of flames and matter after another, we eventually see a humanoid creature floating in the distance. The humanoid eventually shoots tiny particles of matter out of a phallic attachment. One of those particles carries the face of none other than Killer BOB. The imagery is clear in its meaning: once humans created technology that could kill of its own planet, a new kind of evil had emerged into the world. Killer BOB is that evil imagined as a singular demonic entity.

But enough about the content, or the plot of the episode. There have already been plenty of recaps documenting its various thrilling enigmas: The Giant seemingly manifesting Laura’s spirit as a mutant bug that crawled into a young girl’s mouth via her bedroom window, or the horrific drifter walking around asking people for a light before he crushed their skulls with his bare hands and delivered a terrifying and poetic sermon over a radio airwave, or the impromptu Nine Inch Nails performance that preceded the madness. What is more important to note is the fact that there is a strong case to be made arguing that this episode was the pinnacle of all that David Lynch has ever tried to achieve. Lynch has always been a kind of pop artist. He comes from a background in abstract painting and sculpture, but he also has a deep and profound love for cinema that eventually influenced him to sit in a director’s chair. All kinds of cinema, from the kind of abstract cinematic geniuses you’d expect like Werner Herzog and Federico Fellini, to rigorously formalist filmmakers like Billy Wilder. From Eraserhead on, Lynch has tried to marry the formal conventions of cinema (plot, narrative, tension, juxtaposition, conclusion, etc..) with abstract and surrealist contemporary art. Twin Peaks was initially birthed of his interest in marrying conventional TV tropes, like soap opera and mystery, with that sense of terror art that he got famous for. But nevertheless, the constrictions of TV in the early nineties exhausted, and eventually bored, Lynch and he moved on. But now, he has been able to bend the conventions of television at will in this new season of Twin Peaks, and episode 8 was when he blew them up entirely. This hour of TV finds him drawing on all of his cinematic language and themes, from the surrealist ethos of his subconscious dream logic to origins of evil to the concept of dual identity (as this episode alludes too, Bob and Laura might be each other’s opposites, two side of one coin, if you will), while still working as a plot building episode within a contained, albeit sprawling, television narrative. There is no doubt that this episode will make the broad and at times confusing plot of the new season of Twin Peaks come into focus as it continues.

It was also the most mind-blowing cinematic experience I’ve had in years. And I watch everything. By successfully pulling off this episode, Lynch has also reminded viewers of the overwhelming potency that cinema and moving images can have that other mediums just don’t come close to. There is a lot of great stuff on TV right now, and one could even argue that something like Damon Lindelof’s The Leftovers had some jaw-dropping moments of pure cinema. But after watching Episode 8 of Twin Peaks: The Return, even the best shows feel like hour long scenes of conversation between people without much cinematic impact (on his podcast, American Psycho author and famed cinephile Bret Easton Ellis argues that television can’t do what cinema does visually because the writer is the one in charge, not the director, but that’s for another think-piece). Episode 8 is a reminder of the power of cinema, art and images. But it also still works as plot device for the over-arching narrative of the show. More than ever before, Lynch has pulled off a piece of work that indulges his wildest artistic dreams while still paying heed to the kind of formalism that television production necessitates. I don’t know about you, but when Twin Peaks: The Return returns for its second round of its 18 episode run this Saturday, I can’t wait to see what Lynch does next. We are witnessing something that will be written about by art historians as much as it will be by academics of pop culture. This is thrilling.

Link (TP)

21 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Kyle MacLachlan and David Lynch excited to collaborate again in the return of 'Twin Peaks'

For Kyle MacLachlan, it was all about the suit.

More than a quarter of a century since “Twin Peaks” ended its brief but influential run on ABC, the actor is reprising his signature role as FBI Special Agent Dale Cooper, a man whose appreciation of cherry pie and a “damn fine” cup of coffee knows no bounds, in a long-anticipated revival premiering Sunday on Showtime.

MacLachlan has been through quite a lot since the early ’90s, when the mystery of who killed beauty queen Laura Palmer captivated viewers.

The 58-year-old, his hair graying ever so slightly at the temples, has endured wild career swings, gotten married, become a father, and even started a wine business.

Dressed in head-to-toe black, he's seated in an office at Showtime's headquarters in midtown. A dozen stories below, city buses bearing sepia-tone images of him as an older, but still dashing, Cooper chug down Broadway

Luckily the suit still fit.

“The suit pretty much sets it for me — my whole being starts to transform,” says MacLachlan, moving his hands as if grasping an invisible pole to suggest Cooper’s ramrod posture. “And also just David’s presence. When David’s there, I’m Cooper.”

That would be David Lynch, who co-created the original series with Mark Frost and co-wrote and directed all 18 episodes — or “parts,” as he prefers to call them — of the revival. Announced with much fanfare in October 2014, the limited series premieres Sunday and is shrouded in a layer of secrecy that makes the NSA look like amateurs. (Even seemingly benign details about Cooper’s suit were deemed too spoiler-y for print.)

The series marks the return of not only one of the most admired cult series in television history but also the creative partnership between Lynch and MacLachlan, whose most recent collaborations were the 1992 prequel film “Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me” and a series of “Twin Peaks”-themed Japanese coffee commercials from the same era.

Their relationship dates back to the mid-1980s when MacLachlan, then an unknown actor fresh out of the University of Washington, was plucked from regional-theater obscurity to play the lead in “Dune” (1984), Lynch’s first foray into big-budget Hollywood filmmaking. The adaptation was a notorious commercial and critical failure, but it marked the beginning of a dynamic period of collaboration between the actor and director.

“Blue Velvet” (1986), was the antithesis of “Dune” but a precursor to “Twin Peaks” in its warped view of small-town life and flashes of deadpan humor. MacLachlan starred as Jeffrey Beaumont, a college student whose discovery of a severed ear in the grass leads him on an adventure that plays like “The Hardy Boys” on bad acid.

Cooper was conceived as “a grown-up Jeffrey Beaumont,” says Lynch in a phone interview.

“He’s a magical kind of detective,” explains the director, whose plainspoken quality somehow makes him more inscrutable. “He’s got way more energy than most people. He’s always wide awake and alert and he’s always happy.”

Though Cooper is first introduced a full half-hour into the pilot episode of “Twin Peaks,” he makes an immediate impression, enthusing about the local evergreen trees in the first of many tape-recorded messages to the never-seen Diane.

“That scene very much encapsulated the range of things Kyle can play,” says Showtime President David Nevins. “He’s stalwart and subversive at the same time, which is hard to do.”

MacLachlan still considers the pilot, which he rewatches from time to time, “an extraordinary piece of filmmaking.” It debuted in April 1990 to enormous ratings and ecstatic reviews, with critics praising the singular blend of horror, soapy melodrama and quirky humor. But once the central mystery was resolved, viewers fled. Despite organized protests from fans, ABC canceled the series after 29 episodes, immediately cementing its status as a cult classic.

The part earned MacLachlan two Emmy nominations, a Golden Globe Award and countless free cups of coffee from admirers over the years.

“‘Twin Peaks’ is still the [project] people respond to more than others,” he says, pausing for a beat, “certainly more than ‘The Doors.’” (In case you’d forgotten, he played keyboardist Ray Manzarek in the Oliver Stone film.)

“Twin Peaks” is a surreal puzzle of a show whose influence is evident in shows from “Stranger Things” to “True Detective.”

Wisely, though, few have attempted to imitate its eccentric yet pure-hearted protagonist. Cooper is, on one level, an old-fashioned Hollywood hero marked by boyish enthusiasm and unflagging moral rectitude, a point driven home in the series pilot when he’s mistakenly called Gary Cooper. This is a character who once proclaimed “I would very much like to make love to a beautiful woman who I had genuine affection for” while lying near death on the ground with a gunshot wound in his stomach.

And yet beneath the clean-cut G-Man exterior beats the heart of an oddball. Cooper relies on dreams and visions as much as physical evidence, communicates with dancing dwarfs from alternate dimensions and is drawn to Eastern spirituality. In the series’ second episode, he famously eliminated suspects by throwing stones at bottles from a distance of 60 feet — a technique inspired by his love of Tibet.

“He seems to be secretly listening to radio waves from the zodiac, through the fillings in his teeth,” wrote critic John Leonard in his New York Magazine review of “Twin Peaks.” “He’s a wonder, a puzzlement, a Boy Scout from Sirius the Dog Star.”

Between bites of a ham sandwich, MacLachlan puts it more simply. “You feel like he’s come through darkness, but he’s been able to keep it in place. It doesn’t drive him.”

The series concluded with one of the most heartbreaking series finales in TV history. After a harrowing journey through the mysterious Black Lodge — a.k.a. that room with the red curtains — Cooper was possessed by the malevolent spirit known as Bob. What’s happened to the agent since then — did he take to murdering young girls, like Bob-possessed Leland Palmer before him? — is easily the biggest question hanging over the revival.

MacLachlan hit a rough patch in the years that followed “Twin Peaks,” epitomized by a Razzie-nominated role in "Showgirls" that involved an unintentionally hilarious pool sex scene. But he eventually found a niche of sorts in parts that, like Agent Cooper, played in tension with his classic good looks. In “Sex and the City,” he portrayed Charlotte’s seemingly perfect first husband, Trey MacDougal, a WASPY cardiologist with deep-seated mommy issues and a pesky case of erectile dysfunction. And there was Orson Hodge, Bree’s lying, philandering, would-be plumber-murdering husband on “Desperate Housewives.”

What he didn’t do was return to work with Lynch, who made films with other dark and handsome types, like Justin Theroux (“Mulholland Drive”). MacLachlan has theories about why. “I’m Cooper for David,” he says. “That’s it. I’m Cooper and I live in Twin Peaks.” (Lynch gently disputes this: “If another role came along that he was right for, I would know it and I would be very happy for him. It just didn’t ever happen.”)

However, the pair did see each other regularly. MacLachlan has a home in the Hollywood Hills, just up the road from Lynch. When in town he’d often “just take the parking brake off the car and roll down the hill” for a cup of coffee — yes, coffee. Their conversations would inevitably turn to “Twin Peaks.”

Lynch would usually dismiss the idea of a revival, even though “it wasn’t ever dead,” he says. “The stories continue in one’s mind.”

Eventually, MacLachlan got an urgent phone call from Lynch: He had something to discuss but couldn’t talk about it on the phone. “I said, ‘I hope it’s nothing health-related,’” MacLachlan recalls.

It was not. In New York, Lynch pitched him the new “Twin Peaks” and asked if he’d be interested in reprising the role of Cooper. “I said, ‘I’ve never not been interested,’” says MacLachlan, who was “seduced by the challenge” of reviving “Twin Peaks.” The series arrives amid a wave of ’90s revivals taking over the small screen, including “Fuller House,” “The X Files” and “Will & Grace.”

But this continuation is not driven by nostalgia, insist those involved. If anything, Lynch, who was less involved in the show’s second, uneven season, seems motivated by a desire to course-correct and return to the vision laid out in the pilot. “In my mind the series drifted away from what I thought of as ‘Twin Peaks,’” he says. “It was tough to watch for me.”

Co-writing and directing 18 hours of television — after more than a decade away from full-time filmmaking — was a feat of stamina for Lynch, who also returns in a supporting role as Cooper’s boss, Gordon Cole. “I was a major stud before I started, and now I can barely walk,” he jokes.

For Showtime’s Nevins, Lynch and Frost’s hands-on involvement was essential. “I was only interested if I knew it was going to be the real thing,” he says. The executive describes the revival as Cooper’s “odyssey back to himself” and an exploration of relevant themes of national identity.

“I find Kyle such a quintessentially all-American actor, and I think that’s what David likes about him. It’s really interesting revisiting this character and this world in a moment in American history where we’re trying to figure out who we are, and what it means to ‘Make America great again.’”

MacLachlan is less inclined to elaborate, but does let it slip that — spoiler alert — his professional chemistry with Lynch returned instantly. “That’s something that came back like that,” MacLachlan says with a snap of his fingers. “We do a great dance together.”

link (TP)

16 notes

·

View notes

Photo

@Variety COVER STORY: Inside the roller-coaster journey to get @DAVID_LYNCH's #TwinPeaks back on TV

A red room. A dream version of Laura Palmer. An older Special Agent Dale Cooper, silent and pensive. The Man From Another Place, speaking cryptically: “That gum you like is going to come back in style.”

It was early 1989, and Lynch was hard at work on “Twin Peaks.” He and co-creator Mark Frost were trying to meet the deadlines of ABC, the network that had commissioned a drama about love, pie and murder in a Pacific Northwest town. Lynch was under pressure to create scenes that would allow the pilot to be released as a TV movie in case it didn’t get picked up to series. But the filmmaker didn’t have any ideas for footage that could wrap up the story neatly enough to please a movie audience.

Then he walked outside during an early-evening break from editing and folded his arms on the roof of a car.

“The roof was so warm, but not too warm,” Lynch says. “It was just a really good feeling — and into my head came the red room in Cooper’s dream. That opened up a portal in the world of ‘Twin Peaks.’”

That vision ended up in the third episode — but more importantly, it would lay the groundwork for the highly anticipated revival of the series, which returns May 21 on Showtime. It’s an older Cooper that anchors the series.

While countless reboots of numerous series have crashed and burned, it’s safe to say few have been as intensely followed by fans as this one. As Showtime CEO David Nevins put it, “‘Twin Peaks’ as a place is a proper noun, but it’s almost become an adjective.”

Since the show’s debut in April 1990, many dramas have tried to create the kind of evocative, twisted atmosphere “Twin Peaks” exuded from the first twanging notes of Angelo Badalamenti’s yearning score. And though intense dramas about murders that reverberate through tight-knit communities are now easy to find on TV, no show has come close to achieving the mix of humor, soapy drama, sincerity and corrupted purity found within the strange confines of “Twin Peaks.”

That’s because much of what’s distinctive about the drama emerges from the most unpredictable corners of Lynch’s mind — like that red room epiphany.

“It comes in a burst,” Lynch explains. “An idea comes in, and if you stop and think about it, it has sound, it has image, it has a mood, and it even has an indication of wardrobe, and knowing a character, or the way they speak, the words they say. A whole bunch of things can come in an instant.”

Frost describes a case in point: “I remember him calling me to say, ‘Mark, there’s a giant in Cooper’s room,’” he says. “I learned early on that it was always best to be very receptive to whatever might bubble up from David’s subconscious.”

The first iteration of “Twin Peaks” lasted only two seasons — 30 episodes in all — but the show left a legacy that would help define auteur TV.

“I don’t think anyone who ever saw ‘Twin Peaks’ will ever have it not ingrained in their memory and imagination for the rest of their lives,” says Laura Dern, a frequent Lynch collaborator who plays a mysterious role in the new season.

Yet getting the series back on-screen was no easy feat. At one point, the revival almost fell apart before production began. It would take delicate negotiations by all parties to rescue the project.

“I was an actual, genuine lover of ‘Twin Peaks’ and the world that [Lynch] created, and I knew his filmography really well,” Nevins notes. “[We said] we would take the ride with him, and that we would treat it well and treat it with the respect that it deserved. I think we did. We bobbed and weaved with him; we were patient when we had to be patient.”

Lynch and Frost began talking about returning to “Twin Peaks” in August 2012, in part because the show’s baked-in time jump was approaching — in that pivotal red room scene, Agent Cooper is 25 years older. The two men shared ideas over meals at Musso & Frank, and after the writing process had begun in earnest, they started to shop the revival around. They settled on Showtime fairly quickly, given their history with the executives.

Gary S. Levine, Showtime’s president of programming, has known Frost and Lynch since his days at ABC. Almost three decades ago, he was one of the execs who heard their pitch for the TV show they initially called “Northwest Passage.” (Levine still has the memo that notes the date of the first concept meeting for the pilot — Aug. 25, 1988.)

But as with everything Lynch, the agreement for the redux came down to instinct: A final piece of the puzzle, say the execs, was a painting in Nevins’ office of a little girl next to a bookcase that looks like it may fall on her. “I was making the pitch about why he should come here and why we would treat his property right, and he mostly stood there and stared at the painting,” Nevins recalls. (For his part, Lynch says the painting wasn’t the deciding factor, but he smiles at the memory of seeing it.)

The deal closed in the fall of 2014, with an order of nine episodes; the following January, Lynch hand-delivered a 400-page document.

“It was like the Manhattan phone book,” Frost says. Their plan was to shoot the entire thing — with Lynch at the helm of every episode —and then edit the resulting footage into individual episodes.

It’s hard to imagine wrestling that 400-page behemoth into a briefcase, let alone giving notes on it. When talks broke down, however, the conflict wasn’t about the script but rather the project’s budget.

In April 2015, the director went public with his growing displeasure, tweeting that “after 1 year and 4 months of negotiations, I left because not enough money was offered to do the script the way I felt it needed to be done.”

Lynch’s threatened departure generated a flurry of commentary, most of which said that a version of the TV show without him would be worse than no “Twin Peaks” at all.

“I didn’t want ‘Twin Peaks’ without Lynch either,” Nevins says drily.

The Showtime chief says he was out of the country when negotiations hit that difficult patch. Lynch wanted the flexibility to expand the length of the season, but he didn’t know exactly how many episodes he’d end up with. He hoped it would be possible to go longer than the 9 or 13 installments that had been discussed, but he ran into resistance from the network’s business affairs department.

“It didn’t fit into the box of how people are used to negotiating these kinds of deals,” Nevins says. “Once I understood what the issues were from the point of view of the filmmaker, I was like, ‘OK, we can figure that out.’ And we did — it turned out not to be very complicated to [resolve].”

Nevins and Levine went over to the director’s house. “Gary brought cookies,” Lynch recalls. And over baked goods and coffee, the three men hashed everything out.

Lynch, says Nevins, has a history of being responsible. “He said, ‘Give me the money; I will figure out how to apportion it properly.’ And he did,” Nevins says. (Levine says the cost of “Twin Peaks” is comparable to that of Showtime’s other high-end dramas.)

Asked for his side of the story, Lynch asks, “What did Showtime say?” Told their version, he signs off: “Basically, that’s it.” He says his relationship with the network ever since the cookie summit has been “solid gold.” (Treats never hurt: When he delivered cuts of the new season, he sent along doughnuts.)

The mystery of the first season of “Twin Peaks” was, famously, “Who killed Laura Palmer?” The mystery of the reboot is, well — nearly everything. None of the 18 episodes will be released in advance to critics, and very few details have leaked out.

Though cast members such as Kyle MacLachlan (Agent Cooper), Madchen Amick (Shelly Johnson), Sherilyn Fenn (Audrey Horne) and Ray Wise (Leland Palmer) are returning, others, including Joan Chen, Michael Ontkean and Lara Flynn Boyle, won’t be back. No one will say what characters are being played by new recruits Dern, Ashley Judd, Tim Roth, Naomi Watts and Robert Forster — there’s a roster of more than 200 characters in the new season. Frost’s father, Warren; Catherine Coulson, the Log Lady; and Miguel Ferrer, who played the irascible Albert Rosenfield, all filmed scenes before they died.

Nevins lets it slip that Lynch’s character, the hearing-impaired FBI Regional Bureau Chief Gordon Cole, is “pretty prominent” in the new season. “I probably said too much,” he adds.

MacLachlan says that Lynch enjoys the world of “Twin Peaks” so much that he couldn’t resist putting himself back in it. But he admits that, for his part, he finds it hard to stay in character when he’s doing scenes with his director. “Unless we’re really both firmly rooted in what we’re doing, we tend to start laughing and messing up,” the actor says. Stopping for a moment, the actor reconsiders: “David, when he works, he’s very committed to Gordon. So when I’m in there with him, he’s able to really hold it. He holds it better than I do, to be honest.”

For those expecting a similar structure to the original, which revolved around Laura’s death, Frost issues a warning: “It’s going to be very different this time around.”

The scope of the reboot is greater, says Nevins, adding that the new installments of the drama reflect Lynch’s advancement as an artist.

“I think he’s evolved to an even more extreme version of himself, but all of the [Lynch] themes are visible,” Nevins says. “He has certain ideas about the ideal of America. Not to relate it too much to the present, but he has certain ideas about Midwestern American wholesomeness. But I think he’s also incredibly aware of the flip side of it. I think David Lynch is a really relevant voice: What does it mean when we say, ‘Make America great again?’”

Given the wider scope, it’s not surprising to hear that, though “Twin Peaks” returned to Snoqualmie, Wash., for some filming, certain storylines in the new season take place outside the Pacific Northwest, and the bulk of the new season was shot in Southern California.

“There are different threads in different parts of the U.S.” that eventually converge, Nevins says. “It does not go outside the U.S., but it is in multiple locations in the U.S.”

One last clue from Lynch: The film “Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me,” he says, is very important to understanding what’s coming May 21.

Even if “Twin Peaks” travels outside its forested Pacific Northwest setting, it’s safe to assume there’s still cherry pie on the menu at the Double R Diner. Lynch and Frost’s collaborative process is also still intact; 25 years later, the two men picked up where they left off.

Lynch lives in Los Angeles and Frost resides more than an hour away, so the two men often worked together via Skype. Frost typically writes down what they come up with, and then the two trade notes and talk further to refine the story.

“Getting it the way you want it to be, that’s a beautiful high and it’s a high for everybody,” says Lynch of directing. “It’s difficult to go home and go right to sleep. And it’s murder to get up in the morning.”

Lynch directed every episode of the drama, which wrapped production a year ago. In a perfect world, he says he would have helmed every installment of the original series.

“Not that other directors didn’t do a fine job,” he says. “But when it’s passing through different people, it’s just natural that they would end up with [something] different than what I would do.”

The freedom of airing on a premium channel didn’t change his approach, Lynch says. There’s not much in the way of nudity or extreme violence in the finished product. “You don’t think, ‘Oh, I can do this now,’” he says. “The story tells you what’s going to happen.”

In fact, despite the show’s reputation for being unsettling, most of what’s dark and dangerous about “Twin Peaks” comes from its mood and soundscape, not necessarily from what’s depicted on-screen. Decades ago, ABC executives were excited about Lynch and Frost’s pitch in part because it was, in many ways, relatively conventional. It fit easily into a number of existing TV categories: the classic nighttime soap, the murder mystery, the high school drama and the small-town saga.

“There certainly weren’t Standards & Practices issues at the time,” Levine says. “[Lynch’s] imagination took you to new places, not to prurient places. That was a good thing in broadcast TV.”

But the otherworldly elements that Lynch layered in — an indefinable air of mystery, a surreal quality that evoked swooning, bittersweet loss — were among the factors that made the original “Twin Peaks” a ratings and pop-culture sensation. And despite that the second season was more uneven than the first, the show often effectively blended slapstick humor with dream logic, bittersweet romance, heightened melodrama and hints of violence and degradation.

“He’s got both really good craft and storytelling skills, and he also creates his own reality without it violating the reality you’re in,” Levine says. “I think that was one of the great things about the original — it was a really compelling plot, but it also was this acid trip. Somehow those two things coexist beautifully in David Lynch’s world.”

Lynch doesn’t question where inspirations like the red room scene come from; he simply wants to capture them with his cameras. And lest anyone think he’s overly precious about his process, Lynch doesn’t consider himself the creator of these visions.

“It's like that idea existed before you caught it, so in some strange way, we human beings, we don't really do anything,” he says. “The ideas come along and you just translate them.”

What might Lynch’s response be if an actor said, about a line, "That doesn't feel right to me”?

“I don't know if I've ever said that to him, actually,” says MacLachlan, stumped by the question. “I mean, I would never change it. It is there for a reason.”

In fact, to hear him tell it, the fact that Cooper is an iconic TV character is in many ways a tribute to the writing for the character, especially in Cooper’s debut scene.

“I brought my stuff, yeah,” MacLachlan says. “But that’s one of the greatest introductions into a story of any that I've ever had — driving up the mountain, talking into a tape recorder about some of the mundane things in life, just kind of cataloguing it. Immediately, you wonder, ‘Who is this guy and what is he about?’”

“When I first started with David in ‘Dune,’ I was full of questions. I would bother him non-stop,” MacLachlan says. “He always had a great deal of patience with me. On ‘Blue Velvet,’ I still [had questions], but less, and then with ‘Twin Peaks,’ even less. I've stopped having to know everything. I’ve just said, ‘OK, I see where we're going.’”

“For Kyle and I, we've spoken about this incredible gift that we know what [Lynch] means” when he discusses his vision for a scene or a project, Dern says. “We have gone on this journey with him, so we know his language, or what he's inventing. We don't necessarily need to understand it or need it to be logical, but we see where his brain is taking him and we can follow.”

Dern and MacLachlan both say they relish the opportunity to work with Lynch because his vision is so specific that it gives them a detailed road map to follow — and it makes the set an efficient place.

“There’s no wasted time or wasted emotions, tangents, whatever,” MacLachlan notes. “He’s very precise when we talk through the scene, and he tells me what’s going to happen. He has already thought it through, and he sees it.”

Dern marvels at the rigor and enigma of Lynch’s process. “David creates these worlds, sometimes all too real and sometimes incredibly absurd, but either way, he places humanity inside them, and his dialogue is so precise, mysterious, unusual and beautiful that you want to dive into that dialogue and hopefully make it soar,” she says.

Given Lynch’s penchant for secrecy, just about all Dern can say about her character is that she talks about birds, at least once.

“Kyle and I had several scenes, particularly in the car, when we're talking about the robins,” Dern says. “There’s this very beautiful, hopeful poetry amidst this hellish world they've entered.”

Rewatching “Twin Peaks” recently, MacLachlan was struck by how the editing of the show helps it create a series of moods, from comedic to tautly suspenseful, from romantic to terrifying.

“His timing, his rhythms,” MacLachlansays. “That's what I find so interesting about David Lynch — the way he stretches things or condenses things, or manipulates time to make something either seem more humorous or less.”

Now all that remains to be seen is how the public responds to the new adventures of Agent Cooper, that avatar of square-jawed all-American perseverance.

“I believe in intuition,” Lynch says. “I believe in optimism, and energy, and a kind of a Boy Scout attitude, and Cooper’s got all those things.”

The most important parallel between Lynch and Cooper is that their belief in their own intuition is matched by a purposeful, almost single-minded intent. What allows Lynch to put deeply felt images from his subconscious on the screen is a tenacious focus — one that’s cloaked in the kind of smiling, friendly optimism that Cooper typically exudes.

“His vision is genuine,” Dern says. “He’s not interested in creating something so others will be impacted by it. He just sees a world and has to follow it.”

Despite the passionate responses his works have created, Lynch doesn’t necessarily set out to delve into the hearts and minds of his viewers. He’s just an interpreter of something primal — a messenger for the visions that find him.

“I guess, like Mel Brooks said, ‘If you don’t laugh while you’re writing the thing, the audience isn’t going to laugh,’” Lynch explains. “If you don’t cry or feel it while you’re doing it, it’s probably not going to translate.”

Almost 30 years ago, TV viewers followed Lynch through that portal to the red room. Despite the crowded TV landscape “Twin Peaks” helped create, Nevins thinks audiences will take the journey again.

“I think he does have enormous self-confidence as an artist — that what resonates with him won’t resonate with everybody but will resonate with enough people that it’s going to make noise in the world,” Nevins says.

And if there is silence, that’s fine too.

“If nothing happens, it’s still OK,” Lynch says with a smile. “This whole trip has been enjoyable.”

Link (TP)

4 notes

·

View notes