#american rayon institute inc.

Text

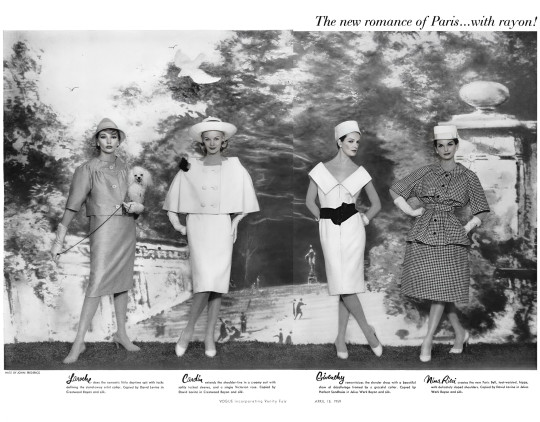

US Vogue April 15, 1959

American Rayon Institute, Inc.

Simone d'Aillencourt wears a suit by Guy Laroche, copied by David Levine in Crestwood Rayon and silk.

Sunny Harnett is wearing a Pierre Cardin suit. Copied by David Levine in Crestwood Rayon and silk.

A model wears a dress by Hubert de Givenchy. Copied by Herbert Sondheim in Julius Werk Rayon and silk.

Anne St. Marie is wearing a Nina Ricci suit. Copied by David Levine in Julius Werk Rayon and silk.

Hats by John Frederics.

Simone d'Aillencourt porte un costume Guy Laroche, copié par David Levine en Crestwood Rayonne et soie.

Sunny Harnett porte un costume Pierre Cardin. Copié par David Levine en Crestwood Rayon et soie.

Un mannequin porte une robe Hubert de Givenchy. Copié par Herbert Sondheim dans Julius Werk Rayonne et soie.

Anne St. Marie porte un costume Nina Ricci. Copié par David Levine dans Julius Werk Rayonne et soie.

Chapeaux par John Frederics.

Photo uncredited/non crédité.

vogue archive

#us vogue#april 1959#fasgion 50s#1959#copied#haute couture#french designer#french style#american rayon institute inc.#guy laroche#pierre cardin#hubert de givenchy#nina ricci#simone d'aillencourt#anne st.marie#sunny harnett#john frederics#david levine#herbert sondheim

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Importance of the use of Clothes with Solar UV Protection - Juniper Publishers

To know more about Journal of Fashion Technology-https://juniperpublishers.com/ctftte/index.phpTo know more about open access journals Publishers click on Juniper Publishers

Abstract

Normal clothes protect human body form the harmful effects of intense solar Ultraviolet (UV) radiation in a wide range of values of the UV Protection Factor (indicated as UPF). In the present review, we describe how this factor is defined, how it is related to the well-known Solar Protection Factor (SPF) of sunscreens and what kind of fabric characteristics and materials determine the protection level. We also present a typical measurement of solar transmittance, solar protection and the UPF value determined in actual conditions of fabrics exposed to solar radiation. We propose that all fabrics need to include universally the identification of its UPF.

Keywords: Solar UV Protection; Ultraviolet; Sunscreens; Solar transmittance; Solar protection; Solar radiation; Sun burning; Skin cancer; Fabric; Clothes

Abbreviation: UV: Ultraviolet; UPF: UV Protection Factor; SPF: Solar Protection Factor; ALD: Atomic Layer Deposition; ARPANSA: Australian Radiation and Protection Nuclear Safety Agency

Go to

Introduction

From thousands years ago, clothes were fundamental in the protection of persons against the adverse effects of the environment (cold and hot weathers, rain, snow, wind). Only in the last decades it has been emphasized the significance of clothes against solar adverse effects, like sun burning and many other diseases, been skin cancer the most important one [1]. Recently, a factor has been introduced in order to characterize the protection a cloth gives to the person that uses it outdoor. It is called Ultraviolet (UV) protection factor (most commonly known as UPFX) for a given fabric X and it gives the possibility to quantify the skin shielding to this harmful radiation. It was first introduced in Australia [2] and then generalized all over the world, through the CIE (Commission Internationale d‘Eclairage or International Commission on Illumination) report [3,4].

Its inverse value (multiplied by 100) corresponds to the percentage transmittance of solar UV radiation,

Consequently, it cannot be less than 1. For example, if a fabric X has an UPFX=50 (Table 1), it means that only 2% of the incident radiation will arrive on the skin, but if it has a value UPF= 5, it will permits the incidence on the skin of 20% of the solar UV radiation. The percentage solar UV protection is:

So, in the former case the protection is very high, 98% but in the latter case, only 80%.

A qualification scheme has been introduced (Table 1), in order to present in a more simple way, the protection against UV solar radiation. The qualification values varies between those lowers or equal to 14 that are considered “Not good” and those equal or higher than 40, that are “Excellent”. It must be noted that the 50+ qualification corresponds to all UPF values higher than 50.

Similarly to UPF, a Solar Protection Factor (SPFY) was previously introduced for sunscreens of type Y. In this last case, the SPF is defined as the factor that needs to multiply the maximum exposure time of a given skin phototype (ranging from I to VI following the Fitzpatrick classification [1]) exposed to the Sun, to determine the time interval before having the possibility to develop sunburn [1]. For example, as recommended by the American Academy of Dermatology, a person with Caucasian skin phototype needs to use at least a sunscreen with SPF = 30 and can stay under intense UV solar UV radiation a maximum of 15 minutes (time interval without applied sunscreen) multiplied by 30, or 450 minutes. However, due to transpiration, possible access to water in a piscine, sea, etc, dermatologists recommend to repeat the sunscreen application about each 2 hours.

According Gloster & Neal [5], skin cancer is less common in darkly pigmented persons than in Caucasians because the darkly skin has a Sun Protection Factor (SPF) of up to 13.4 in blacks. However, the skin cancer in darkly pigmented persons is often associated with increased morbidity and mortality.

We like to point out that the clothes normally do not cover all the body; consequently, these recommendations need to be taken into account in combination with clothes having a high UPF.

Fabric properties and materials

Different types of fibers are employed in the production of fabrics. For example, natural fibers are made of cotton and wool and artificial fibers are mainly of polyester, nylon, Lycra, acrylic and rayon. They have quite different behaviors against solar UV radiation. One of the first characteristics to be taking into consideration is the amount of fiber/yarn per unit of surface area who determines its porosity. The lowest this quantity, the lowest the UPF. This fact can be easily confirmed observing a fabric with a light source behind (better not the Sun, since the fabric protection could be not enough if it is very low). If the visible light traverses the fabric and the source can be seen rather well, normally its UPF is quite small and consequently with low protection. On the contrary, if the light is almost not seen, the protection is quite high. It can be easily understood that bigger holes in the fabric between the fiber/yarn, permit to pass more solar radiation through it.

Other properties are:

a. The color, with darker colors absorbing more solar UV radiation than clear colors. For a given color, brilliant (reflective) fabrics, like rayon, are better than mate ones, like linen. However, a darker color absorbs efficiently solar radiation in the infrared (thermal) range, increasing the risk of heatstroke disease. Consequently, is better to use outside clothing made with a clear color fabric, but with the highest possible UPF value. Srinivan & Gatewood [4] demonstrated that colors influence significantly the UPF value in cotton (=4.1). They obtained significant increases in the UPF value when dyes of different colors were applied (in a 0.5% concentration of weight): 20 for Yellow 28 dye, 21 for Violet 29 dye, 22 for Blue 1 and Green 26 dyes, 30 for Black 38 dye and 39 for Red 28 dye;

b. The elasticity, since if the fabric is elongated the porosity increases;

c. The density (and depth), since tight construction (and thicker fabrics) reduce the amount of UV radiation that can traverse through the fabric and

d. The water content, more quantity tends to reduce the UPF.

Besides dyes, chemicals can be added to fabrics to improve their UPF. In what follows we will analyze some treatments of this kind:

• Xiao et al [6] applied an Atomic Layer Deposition (ALD) [7] as a coating on a fabric, depositing TiO2, Al2O3, and TiO2/ Al2O3 nano-layers onto dyed polyamide/aramid blend fabric surface. This fabric showed an excellent UV resistance, suggesting that ALD technology can be used effectively to improve dyed fabrics properties.

• Gies [2] determined through laboratory tests done in the Australian Radiation and Protection Nuclear Safety Agency (ARPANSA) that Lycra fabrics normally have UPF values of 50 or 50+, higher than nylon and polyester.

• Chakraborty et al [8] investigated the addition to cotton fabrics, of two conventional absorbers: benzophenone (that absorbs mainly in the UVB, 280-320nm wavelength range) and 2.4 dihydroxybenzophenone (mainly in the UVA, 320- 400nm range) and two new absorbers: avobenzone alone and avobenzone in combination with octocrylene. They obtained the (significant) result that the new absorbers increase by a factor up to 200 the UPF with respect to the conventional ones.

• Pakdel et al [9] analyzed the significant enhancement due to antimicrobial coating on cotton fabrics; employing metalized Titanium dioxide (TiO2) with noble metals, Silver (Ag) and Gold (Au) and silica. They determined a positive impact on UV protection in the case of the use of metals in the synthesis process, but a negative one in the case of silica.

Results

Employing the high quality (double monochromator with auto calibration) Optronic 756 spectroradiometer of the Institute of Physics Rosario, we first determined in Rosario, Argentina the incident spectral solar irradiance in the UV (280-400nm) range. This irradiance, Iinc, solar(λ) , corresponds to the solar radiation incident on a unit surface and at a unit time, for a given wavelength interval centered around λ and having units of Joules/(m2second μm) or Watt/(m2μm). Then we interposed the fabric X to be analyzed and made a new measurement, that we call Itrans,X(λ), the transmitted spectral solar irradiance. The ratio:

where Tsolar,X(λ) is the spectral solar transmittance of fabric X.

In Figure 1 we represent Iinc,solar(λ) and Itrans,solar,X(λ) in the (280-400nm) UV range by continuous lines, measured in January 2012. Measurements were acquired in three different moments of the day, near noon and near the maximum of the (Southern Hemisphere) summer, in order to avoid significant changes in the intensity of solar spectral radiation (Figure 1).

Since the measurements were made outside and consequently depend on the sky conditions (absence of clouds, no modification of the atmospheric components, no arrival of contaminant clouds of particulate matter, etc.), we verify if Iinc,solar(λ) did not changed more than 5% in all the wavelength range, doing a new measurement after obtaining the transmitted spectral solar irradiance data. This condition was fulfilled, as can be seen in Figure 1 by the almost superposition of the solar radiation measured points to the continuous curve, the last one representing the incident spectral solar irradiance.

Integrating (summing over all the wavelengths) each spectral irradiance, we determined the so called: incident UV irradiance ( Iinc,UV ) and transmitted solar UV irradiance ( Itrans,UV ,X ). Consequently, we can obtain the solar UV transmittance T*UV,X= Itrans,UV ,X/ Iinc,UV. In Table 2, we present results for Lycra fabric of three different colors, with the following composition: Polyamide 85% and Elastane 15%. It can be seen that the red, yellow and blue colors have quite large UV protection factors, as expected, since the dyes of the fabric absorb a large fraction (more than 98%) of UV radiation.

We like to point out that the solar UV transmittance ( T*UV,X ) values given in Table 2 were obtained in actual conditions of exposure to solar radiation, but the standardized UPFX is obtained in laboratory, with an artificial UV source. So, the corresponding values can differ one from the others. For comparison purposes, we like to point out that Davis et al [10] analyzed the clothing protection of different types of fabrics, and found the highest values for wool (with structure of Twill woven) of 139 and acrylic (with structure of Jersey knit) of 104.

Conclusion

From the present work, we can derive the following conclusions:

a. All fabrics that are designed to be used outside, for different activities (work, recreation, etc) need to have the indication of its UPF, and if possible, the UPF values must be 50 or larger (50+), in order to have a convenient skin protection that normally do not degrades along the hours of the day as is the case of sunscreens, that need to be replaced about each two hours, as recommended by the American Academy of Dermatology.

b. Babies with ages lower than a year must be putted outside solar radiation (as indicated by the Academy previously cited) and kids need to be protected with clothes that have UPF values equal or larger than 50. In particular, authors of the present work verify, through interviews with mothers in a period of 8 years (2010- 2017), that in Rosario, Argentina, babies (Figure 2) and kids that used this type of clothes, do not reported solar burn or other complications of their fragile skins. Note the small Sun shadow projected by the baby in this image, demonstrating a high solar irradiance incident on the place. This is due to the fact that solar radiation needs to traverse a lower atmospheric depth near noon, producing a lower attenuation with respect to the rest of the day. The protection needs to be very efficient, since around noon in the Spring-Summer period, the Solar UV Index (internationally used for qualifying the importance of solar UV radiation incident on a given site, see for example the UNEP report on Environmental Effects of Ozone Depletion and its Interaction with Climate Change [11]) in Rosario city and nearby regions, is usually in the extreme range (values equal or higher than 11).

c. National, regional or city authorities need to incorporate legislation in this sense.

d. Besides the improvement in the materials and design of clothes resistant for UV degradation, the textile industry needs to consider a new circular economy (that optimize the use of natural resource, reduce pollution and recycle), in order to contribute to the global effort to mitigate climate change [12].

To know more about Journal of Fashion Technology-https://juniperpublishers.com/ctftte/index.php

To know more about open access journals Publishers click on Juniper Publishers

0 notes

Text

Hyperallergic: The Novelty and Excess of American Design During the Jazz Age

“Muse with Violin Screen” (detail) (1930) from Rose Iron Works, Inc., designed by Paul Fehér, wrought iron, brass, silver and gold plating (courtesy the Cleveland Museum of Art, on Loan from the Rose Iron Works Collections, © Rose Iron Works Collections, photo by Howard Agriesti)

The Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum’s The Jazz Age: American Style in the 1920s is billed as the “first major museum exhibition to focus on American taste in design during the exhilarating years of the 1920s.” Rather than narrow the lens on this era of rapid cultural and technological change, this concentration on the post-World War I United States is a lively, international showcase of design. “We felt very much that European exhibitions of Art Deco had tried to cover a broad swathe of things, but definitely from a European point of view, and either left out what was going on in America entirely, or dumped everything in but the kitchen sink,” Sarah Coffin, Cooper Hewitt’s curator and head of product design and decorative arts, told Hyperallergic.

“Study for Maximum Mass Permitted by the 1916 New York Zoning Law, Stage 4” (1922), designed by Hugh Ferriss, black crayon, stumped, pen and black ink, brush and black wash, varnish on illustration board; 26 5/16 x 20 1/16 inches (courtesy Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, photo by Matt Flynn, © Smithsonian Institution)

Coffin co-organized The Jazz Age with Stephen Harrison, curator of decorative art and design at the Cleveland Museum of Art. After closing at the New York museum in August, the exhibition will open in Cleveland this September. The collections of both institutions majorly informed the structure and themes of The Jazz Age. “It was when the traditionally minded Cooper Hewitt had started to acquire contemporary design,” Coffin said of the 1920s at the Manhattan museum. During the Cooper Hewitt’s recent multi-year renovation, these holdings came to light. “We began to realize how much material that we had from the 1920s that had been little exhibited, if at all,” she explained.

Meanwhile, the Cleveland Museum of Art has several pieces acquired from the influential Paris 1925 International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts. Exploring the two floors of The Jazz Age is a bombastic visual experience, and any museumgoer who attempts to read every label, to examine each of the over 400 objects, may quickly find their brain saturated. Of course, decadence, novelty, and a collision of colors, styles, and shapes are part of what made the Roaring Twenties so dynamic. As F. Scott Fitzgerald wrote in his 1931 essay “Echoes of the Jazz Age“: “It was an age of miracles, it was an age of art, it was an age of excess, and it was an age of satire.”

Installation view of The Jazz Age: American Style in the 1920s at the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum (photo by the author for Hyperallergic)

Centered on themes like “Bending the Rules” and “Abstraction and Reinvention,” The Jazz Age offers curated tableaux of furniture, flapper dresses, paintings, Prohibition-era cocktail shakers, and all manner of objects to demonstrate influences across media. Many of the featured designers were immigrating from Europe, or having their creations imported to the United States. Others were Americans who went abroad to study and train, picking up tubular metal techniques at the Bauhaus in Germany or ideas for bold hues from De Stijl in the Netherlands. For example, Ruth Reeves studied textiles with Fernand Léger in Paris before she worked on abstracted designs for Radio City Music Hall, and Viktor Schreckengost melded his sculpture studies in Vienna with Michael Powolny with his Ohio pottery background.

“What we were trying to do was show that all this innovation was very much the vibrant conversation of people from many countries coming together in the rising urban environment of New York and places across the country, and interacting across the board in every medium,” Coffin said. She added that the “overall impact of this was an extraordinary amalgamation of designers from a variety of countries who came here with an interest in bringing some of their modern design thinking to American soil.”

“Tissu Simultané no. 46 (Simultaneous Fabric no. 46)” (1924), designed by Sonia Delaunay, printed silk, 18 5/16 x 25 9/16 inches (courtesy Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, © Smithsonian Institution)

Installation view of The Jazz Age: American Style in the 1920s at the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum (photo by the author for Hyperallergic)

The installations in The Jazz Age reflect this rise of international exchange. British designer Wells Coates’s green, circular Bakelite radio, one of the manufacturing innovations being spread to the new middle class, rests on German designer Kem Weber’s sage-hued, streamlined sideboard, which was also intended for serial production. Russian-born craftsman Samuel Yellin’s curling wrought iron fire screen mingles with Lorentz Kleiser’s monumental tapestry showing Newark’s transformation from an indigenous village to an orderly town, both pieces demonstrating the endurance of historical European aesthetics. A towering “Skyscraper Bookcase” of California redwood with black lacquer, all designed by Austrian émigré Paul Frankl, incorporates the zoning-enforced architectural setbacks of the new skyscrapers, something which Erik Magnussen’s Cubic coffee service with its silver angles does on a smaller scale.

“It’s in those conversations where we hope that people can see if we put a beige and gray Jean Dunand enamel vase next to a similarly colored dress that it shows that these colors are the palette of the era,” Coffin said. “You start seeing connections, like an Edgar Brandt screen influencing the Rose Iron Works of Cleveland. It all keeps bouncing back and forth.”

Installation view of The Jazz Age at the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum (photo by the author for Hyperallergic)

“The New Yorker” (Jazz) Punch Bowl (1931), designed by Viktor Schreckengost, manufactured by Cowan Pottery Studio (Rocky River, Ohio), glazed, molded earthenware; 11 3/4 x 16 5/8 inches (courtesy Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, © Smithsonian Institution)

A portrait of Hattie Carnegie by Jean Dunand (1925) with a day dress designed by Marcel Goupy (1919-20) (photo by the author for Hyperallergic)

A trophy designed by Jean E. Puiforcat for a 1923 figure skating competition at the Palais de Glaces in Paris (photo by the author for Hyperallergic)

Paul Manship, “Actaeon (1925), bronze (photo by the author for Hyperallergic)

“Mystery Clock with Single Axle” (1921), produced by Cartier (Paris, France); owned by Anna Dodge; gold, platinum, ebonite, citrine, diamonds, enamel; 5 1/16 × 3 13/16 × 1 7/8 inches (Cartier Collection, photo by Marian Gerard, © Cartier)

Accessories and barware, including a silver owl-shaped cocktail shaker designed by Peer Smed (1931), a design that hid its function during Prohibition (photo by the author for Hyperallergic)

An evening dress and underslip designed by Gabrielle Chanel and produced by House of Chanel, made from blue silk chiffon with applied blue ombré silk fringe (1926) (photo by the author for Hyperallergic)

Pair of wrought iron and bronze gates designed by René Paul Chambellan for the entrance to the executive office suite of the Chanin Building in New York (1928) (photo by the author for Hyperallergic)

“Tourbillons Vase” (1926), designed by Suzanne Lalique for René Lalique; pressed, carved, acid-etched and enameled glass; 7 15/16 x 6 7/8 inches (courtesy Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, © Smithsonian Institution)

Installation view of The Jazz Age: American Style in the 1920s at the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum (photo by the author for Hyperallergic)

A daybed designed by Frederick Kiesler (1933-35) and Aaron Douglas’s “Painting, Go Down Death” (1934) (photo by the author for Hyperallergic)

Installation view of The Jazz Age: American Style in the 1920s at the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum (photo by the author for Hyperallergic)

Installation view of The Jazz Age: American Style in the 1920s at the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum (photo by the author for Hyperallergic)

Installation view of The Jazz Age at the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum (photo by the author for Hyperallergic)

Installation view of The Jazz Age at the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum (photo by the author for Hyperallergic)

A bergere chair designed by Paul Follot after Robert Bonfils, manufactured by Tapisserie des Gobelins and L’Ecole Boulle (1922-25), featuring an airplane (photo by the author for Hyperallergic)

Detail of a door designed by Edgar Brandt inspired by Persian manuscripts (1923) (photo by the author for Hyperallergic)

Installation view of The Jazz Age at the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum (photo by the author for Hyperallergic)

Installation view of The Jazz Age at the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum (photo by the author for Hyperallergic)

Woman’s wool knit striped bathing suit (1920s) (photo by the author for Hyperallergic)

A wrought iron and gilding firescreen designed by Edgar Brandt (1925) (photo by the author for Hyperallergic)

Installation view of The Jazz Age at the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum (photo by the author for Hyperallergic)

A ten-panel screen made of gilt and lacquered wood with patinated bronze, designed by Armand-Albert Rateau (1921-22) (photo by the author for Hyperallergic)

Installation view of The Jazz Age at the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum (photo by the author for Hyperallergic)

Detail of a linen textile designed by Thomas Lamb, manufactured by DuPont Rayon Company, with the Diana’s leaping gazelle motif that was popular at the 1925 Paris Exposition (1920-29) (photo by the author for Hyperallergic)

The Jazz Age: American Style in the 1920s continues at the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum (2 East 91st Street, Upper East Side, Manhattan) through August 20.

The post The Novelty and Excess of American Design During the Jazz Age appeared first on Hyperallergic.

from Hyperallergic http://ift.tt/2tG2g3U

via IFTTT

0 notes