#and i parked in a parking garage next to the handicap area so until i started working on stuff my brain was lik: u parked in the handicap

Text

...

#i survived my drive today. it was v stressful bc there was a lot of construction going on along the highway#and i parked in a parking garage next to the handicap area so until i started working on stuff my brain was lik: u parked in the handicap#area. and it was v annoying bc literally not true. i checked at least 3 times after parking bc my brain is exhausting#but i went and handed the materials over and now its done. i only cried once lol and it wasnt that bad#wasnt that hard i mean. also i kno i swear on here all the time but i do not swear irl unless im driving#also on the way back i just started talking to myself about naruto stuff bc i have to talk while driving or im worried ill lose focus.#usually i sing but idk naruto brain rot#so now im exhausted bc of the stress plus i carried some v heavy boxes around so my body hurts#idk how this weekends gonna go. im going to see some dino tracks tomorrow bc i got invited. so thats exciting. hopefully wont be too#awkward but idk well see.#and i also gotta prep for responding to one guy for a phd position bc i think if i go to the uk im def gonna have to do scholarships for#funding so i gotta figure that out. and i have a meeting with another guy on Wednesday. so hopefully that goes well.#god. the wheels r turning. someday soon ill b a phd candidate#so we'll see how much time i have for drawing. i did make an alt account bc im currently posting from the shadow relm#i had to really think abt. like what would i name myself if i chose a username as a 25yr old and not an emo 12yr old#i went with creeping-cosmic-ooze but handful-of-fish-bones was also v tempting#no short usernames here#aye im tired. but i wanna draw DX#unrelated#god i really like the fishbones username tho

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Vintage russki camera review - Zenit-B w/ Industar 50-2 f/3.5

Intro

I have a modestly sized family and most about every in it is/has been crazy about photography at some point in their lives. My father, in particular, has been in the cozy company of cameras since, like, forever. I've got a picture of him somewhere: a cheerful little lad, no older than a year, crawling around right next to my grandpa's trusty little rangefinder...

What does this have to do with anything? Well, today I'll be reviewing one of my dad's many old cameras - his trusty Zenit-B with an Industar 50-2 50mm f/3.5. He used this one as his 35mm camera of choice after his FED rangefinder, having abandoned it much later after moving on to Japanese SLRs. I actually accidentally bumped into this camera about a year ago in my older brother's attic. Turns out, my dad gave the camera as a present to my bro, who used it for a bit but ultimately forgot about its existence, having moved on to more modern snappers.

Imagine my surprise when I unearth the leather-case-clad tank-of-a-camera with a big bold Made in USSR stamped onto it. The thing was lightly used, lens had no malices typical of a subterranean attic-dweller (haze, fungus), nothing was seriously loose or wrong... until I popped it open to check shutter operation...

Design & build quality

The thing is built like a tank. Mass produced from 1968 to 1973. Rugged and over-engineered, and that is even before I tore it down to get inside and fix it. Inside it looked like it was built to withstand a nuclear blast. A Tchaikovsky Overture of heavy duty gearing, solid steel parts, heavy gauge springs, all tightly wedged against each other with thick flat head screws.

All the more baffling why, oh WHY did they bother to use simple glue to keep together the rubber-coated cloth shutter??? The most important piece of the puzzle, the cornerstone, the heart of the system... why was it made to be so weak? And it's not like there was a large amount of redundancy built into the mechanism - a little bit of glue going undone and the whole curtain self-destructs. Just don't get it.

Anyway, I had to hunt down a spare body with a functioning shutter on eBay to kindly act as a donor. As soon as the box touched down on my front porch the organ transplant was underway and not long afterwards my neighbors probably heard me go on a creepy "it's alive" howl. Frankenzenit was ready for action.

Apart from the shutter glue drama, the camera is a brick, chiseled out of the Terminator's spare parts. And there's just something about that Soviet design aesthetic that gets me every time. Like an old friend you'd sometimes like to forget, but can't. An eclectic mix of extreme cases of forms following function and the necessity for every single object in the country to be fixable with a skeleton toolset of dull screwdriver and hammer. Heck, most of the time even just the hammer was necessary.

Tech specs

Under the covers it was all business and no frills. Barebones feature set, all manual, nothing extra. Shutter goes from 1/30 to 1/500 (the accuracy of which I can't attest to after seeing the mechanism up close and personal), has Bulb. Shutter knob has twist-proof mechanism, reminded me of something you'd find on a T-34 instead of a camera but it has a charm to it, adding an extra step to process.

Winder/shutter button combo with a built-in hand-resetable frame counter and provisions for a standard cable release. A rewind button and rewind/ISO memory wheel. Oh, and a self-timer. Mirror slap is not too obnoxious but don't expect to pull a ninja with this camera - loud and clunky. Next to zero foam in the body, the only seals are made of felt that are still going strong after 45+ years.

The lens is a copy of a Zeiss design, M42 mount, opens up to 3.5 and stops down to 16. Filter thread is, wait for it, 35mm in diameter. Good luck finding a pinch lens cap for it. More details on image quality further down the review.

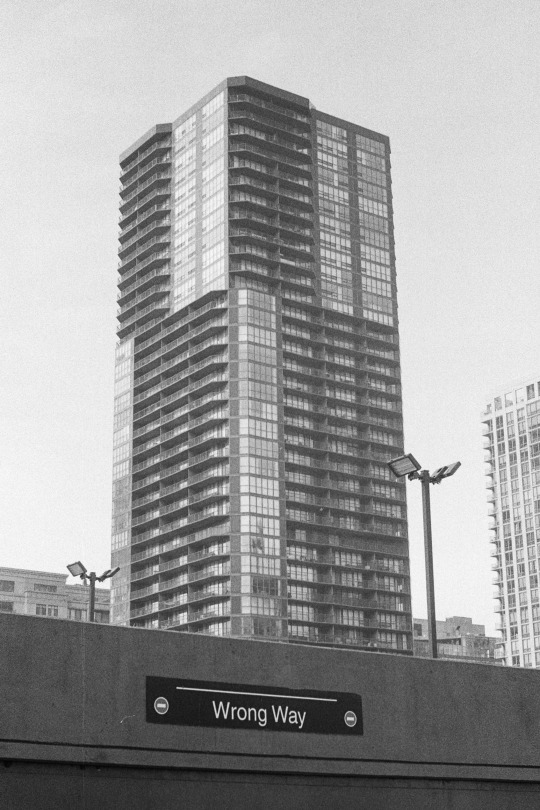

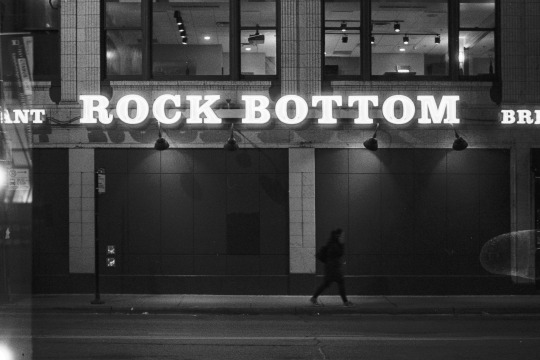

In use

Armed with a meter and a trusty roll of Ilford HP5+ @400 (I ran out of Tri-X at that moment), headed out Downtown with Kris from 43 Stories to see the sights and sounds of the Big City. From the sun-soaked vantage point of a 12-floor parking garage all the way down to chilly pale breeze of the distant skyline from the shores of Navy Pier, the 7-mile 6-hour walk took us all the way from Printer's Row, through the Loop on the L and onto River North, crossing the Magnificent Mile and into Streeterville. Crash at Navy Pier then back home.

Right from the beginning you get a sense that this will be a no-nonesense camera. Everything is roughly where you expect it. The gears are less ergonomic than its peers and the levers dig a little deeper into your skin, but the classic layout was a breather from some of the other cameras I've tested lately. Compact, easy to hold and grip, even with gloves. Aggressive knurling on the controls made fine manipulation easy. Everything clicks solidly.

In addition to the Victorian-Era steely thunderclap of a shutter, the camera has further handicaps that keep it back from being a street-smart photoninja. The shutter speed can't be set blindly, as there are no indicators of what speed you're on anywhere else but the knob. And to change speeds, you have to raise the knob, rotate it and plop it back into the correct setting. There are no physical clicks or stops when you rotate it, so unless you have super-dexterous fingers and a built-in angle meter accurate to the degree, you have to take the camera off of your eyes to readjust exposure.

Same goes for aperture, but this time it's even worse - camera needs to be focused wide open as the finder is too dim. And after you focus you'll most likely have to stop down the aperture. This cannot be done without peeling away from the camera and looking down at the aperture ring. It's clickless, so unless you have a sixth sense for degrees, you will need to look down. Forget quick turnaround time on the streets - this camera is a methodical shooter that requires planning ahead and patience, both from you and any animate object in front of you.

The viewfinder is pretty dim and features a regular ground glass - no fresnel circles in the center or any other focusing aids. With a f/3.5 lens it may not make that much of a difference, but any other lens with a larger aperture may require you to hunt quite a bit to nail that f/2 or f/1.4. Another minor (major, actually) annoyance is that the ring around the viewfinder is, just like most else on this camera, made of metal. Yours Truly Four-Eyes over here needs to first focus with glasses on, making sure not to have direct contact with the metal ring, then slide the glasses over to zoom the eye closer in to compose. The viewfinder optics are recessed deep into the body and it's impossible to see the entire viewfinder area coverage with glasses on. Haven't been able to dig up specs on viewfinder coverage but I have a hunch it's around the 80%-90% mark - I always saw extra features on the negs that I thought were long gone from the frame.

One final note about the viewfinder is that in the camera that I have, the viewfinder is misaligned horizontally, with a couple degrees of rotation to the right. Plain English: when the horizon is straight in my viewfinder, it's actually crooked in the actual photo. I haven't tested this with a bubble level yet, but people call me "human horizon" for a reason - I'm usually very, very careful with that. You hear horror stories about little irking details like this all the time with Soviet cameras, guess they've got some validity behind them, eh? Looking inside, I found no way of adjust the mirror or the ground glass. After peaking into the donor body, that one was misaligned as well, this time leaning to the opposite side.

The winder on this camera is an absolute beast. Quite literally. Be very, very gentle with it. Treat it real slow, nice and easy. The winder sprocket cams inside the body are born from a crude metal cast with razor-sharp edges on the teeth. I consider the Ilford HP5+ film base to be on the pretty durable side, yet even it has had ripped sprockets along most of the length. The winding lever has virtually zero feedback compared to modern cameras and Hulk-like leverage. The only way I was informed that I'd gotten to the end of the roll is when I heard a loud rip of the film from it's canister. Removing it required a dark changing bag. Apart from that expect to get 37-38 shots per 36 exposure roll. Film spacing is pretty consistent and film gate is at a slight angle but at least with no major light leaks (pressure plate still good after all these years).

Image quality

So what do the images look like? They're pretty good, actually. I was expecting it perform a lot worse, but it is a knock-off of a Zeiss design, so that probably helps. First, the numbers. 3.5 is predictably soft, with decent center, medium vignetting and mildly mushy corners. Modern pixel peepers would consider this atrocious, but that's not what film aficionados are after, and to my eye it actually appears pleasantly vintage looking. I found the lens sharpest in the center by f/5.6, with f/8 improving the corners but starting to lose a bit in the center. F/11 exhibits a uniform image from center to corner, that's as in "uniformly soft", and f/16 starts looking like somebody took the photo and printed it on a rug made of low-denier fabrics.

Bokeh is minimal and can get quite busy unless you get REAL close to something. Wide open the bokeh is also quite swirly (couldn't find a more technical term), reminiscent of many vintage lens, where it looks like time and space itself are being bent around your subject matter. A look I actually quite like and one that is currently being revived thanks to Lomography's efforts with lens based on ancient optical formulas.

Flaring can be an issue, but the way the lens handles it is by dissipating the flare across the entire field of view, unlike some other lens where the flare affects the image only partially. I would assume this is because minimal, if any coating was used on the elements. I actually prefer this.

I was also quite surprised by the copious amounts of barrel distortion I noticed when photographing objects close up. I mean, come on - it's a 50, not even a 35! At infinity though, distortion is gone and buildings don't look like they're binging on burgers.

Conclusion

So, what do I think about a camera that has more misalignments than a knocked over vase that was superglued back together? The camera has a lot of sides the modern snapper would find archaic, impractical and irritating. It's a menace to film rolls and close ups of straight brick walls. It's an exercise in patience and meticulousness. And it's a lottery of settings and angles plagued by inconsistency and vagueness. But despite all this it still works, and works solidly. I am still surprised by the engineered heart failure on these cameras, but at a dime a dozen, there's no reason one should stay away from these exotic relics from a bygone world order.

PS: Did I mention that it's a conversation starter?

"Hello sir! May I make a portrait of you?"

"What kind of camera is that?"

"It's almost 50 years old, shoots black and white film and was made in the USSR!"

(eyes bulging in surprise)

"No way! Sure man, take as many as you like!"

Sample pics

#film#analog#35mm#photography#vintage#camera#test#review#ussr#soviet#russian#zenit#zenit-b#industar#ilford#hp5 plus#chicago#downtown#black and white#bw#urban#street#navy pier

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

HomeSKIP TO CONTENTSKIP TO NAVIGATIONVIEW MOBILE VERSION The New York Times Share

Cover PhotoFrom left: William Tyler, Monica Valentine, George Wilson, the creative director Tom di Maria, John Martin and Dan Miller. Credit Jeff Minton for The New York Times A Training Ground for Untrained Artists An Oakland nonprofit has a startling track record for helping developmentally disabled adults become prolific — and profitable — artists.

By NATHANIEL RICHDEC. 16, 2015 The artists arrived at the Creative Growth Art Center shortly after 9 a.m. Most come on East Bay Paratransit buses, which bring them from Alameda, Castro Valley and San Francisco, but a few travel independently. William Tyler takes the orange line BART from his group home in Union City. In 37 years, he has almost never been late. Terri Bowden takes the BART from Fremont, accompanied by a life-size matboard Fred Flintstone. It is a familiar sight to commuters in Oakland’s 19th Street BART station: the legally blind woman with a mohawk and her inanimate sidekick. Bowden periodically replaces the doll’s face; before Fred Flintstone, it was Abraham Lincoln, Michael Jackson, Robert Plant and, at some point, nearly every Creative Growth staff member. John Martin, who lives with his aunt 20 blocks away, walks to work, but not in a straight line. He stops at coffee shops, which fill his empty Gatorade bottles with coffee; at churches, which hand him donated cans of food; and at trash bins, where he rummages for plastic toys, sunglasses and flip phones.

The artists gathered at long tables in the cafeteria. They hung their jackets and stored their lunches in the communal refrigerator. There was a lot of waving and hugging. ‘‘I miss Classie,’’ one of the artists said. It is a common sentiment, even four months after the death of Classie Rozier, the staff nurse for 30 years. On the wall above the tables hang two portraits of her: a framed painting by John Martin and a collage, made by several artists, with three photographs of Classie’s head glued over a red heart.

Dan Miller placed a blue hockey helmet on his head. Tyler sat alone with his head resting in his palm, half-smiling. ‘‘I don’t have any money,’’ Martin mumbled. ‘‘Nah. I don’t have any money.’’

A Creative Growth staff member overheard him. ‘‘You have a lot of money, John,’’ she said.

‘‘I don’t know nothing about that,’’ Martin answered.

‘‘Trust me,’’ she said, laughing. ‘‘You have a lot of money.’’

In June, Facebook bought 35 of Martin’s tool sculptures — cutouts of scissors, hammers and switchblades — for $8,000 and installed them in its enormous new Menlo Park headquarters. Facebook has recently commissioned Martin for 20 more. Martin was invited to the opening but declined to go. He usually doesn’t attend his own exhibitions; at one recent show, Martin ignored the work on the wall and examined the contents of a toolbox that had been left behind by the gallery staff.

Continue reading the main story RELATED COVERAGE

SIGN OF THE TIMES Outside In JUNE 1, 2015

ART REVIEW ‘Art Brut in America’ Highlights Outsider Artists, No Longer Looking In OCT. 22, 2015 Advertisement

Continue reading the main story Facebook’s acquisition is the latest but not nearly the most impressive of a recent series of market successes for Creative Growth, which was founded in Berkeley in 1974 and has since relocated to a former auto-repair shop in downtown Oakland. Creative Growth has capitalized on the surging interest for work by self-trained artists or, as The Wall Street Journal has put it, ‘‘artists who don’t know they’re artists’’: work that in less sensitive times has been referred to as outsider art, naïve art, Art Brut and art of the mentally ill. Such art has experienced a boom during the past 15 years. The work of the field’s most prominent figures — Henry Darger, William Edmondson, Martín Ramírez and Augustin Lesage — has sold in the mid- and high six figures by Christie’s and other auction houses in New York and Paris. The Guggenheim, the Museum of Modern Art and the Metropolitan Museum of Art have acquired work by these artists for their permanent collections.

A majority of the most famous self-taught artists are dead. In many cases, their work was not discovered until after their deaths. It has become difficult to find their art for sale, and what exists is expensive. Collectors and galleries, eager to satisfy the market’s demand, find themselves in an odd position. Typically dealers in search of new art stars comb M.F.A. programs and the studios of established masters. But where might they discover ‘‘artists who don’t know they’re artists’’? Increasingly, these dealers are swarming to this converted auto-repair shop in downtown Oakland.

Creative Growth was born in the garage of Florence Ludins-Katz, an artist and educator, and her husband, Elias Katz, a psychologist who had worked for years at the Sonoma State Home. The Katzes were alarmed by the mass closure of psychiatric hospitals in California, where half of all patients had been deinstitutionalized during the 1950s and 1960s. Shortly after Ronald Reagan assumed the governorship in 1967, he signed the Lanterman-Petris-Short Act, which blocked involuntary hospitalization and resulted in most of the remaining patients being turned out. Few accommodations were made for them after release, leading to an exponential rise among the mentally ill in homelessness and imprisonment.

The Katzes decided to create a center for former state-hospital patients with developmental disabilities, primarily Down syndrome and autism. Their goals, as stated in their 1990 book, ‘‘Establishing the Creative Art Center for People With Disabilities,’’ included not only therapeutic support and vocational training but also ‘‘creation of work of the highest artistic merit.’’ They wrote: ‘‘Even though a human being may be handicapped or disabled, this does not change his need to fulfill himself to the greatest of his capacity.’’

This was not an altogether iconoclastic notion; arts and crafts were offered in many state facilities. What was novel at the time, though, was the Katzes’ insistence that Creative Growth sell artwork to the public. ‘‘The students gain by feeling their art is worthy of being bought and perhaps reproduced,’’ they wrote. ‘‘The Art Center takes pride in the recognition that the art of persons with disabilities is much sought after and has value to society.’’

In 1978, after moving the studio to a storefront in Oakland and receiving a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts, the Katzes opened an adjacent gallery, the first in America dedicated to art by people with disabilities. In 1982, Creative Growth expanded further to a 12,000-square-foot, two-story brick automobile-repair shop on 24th Street. The main open space is occupied by long worktables visible from the sidewalk through a row of large plate-glass windows. There are discrete work areas for drawing and painting, woodworking, printmaking, ceramics, rug making, textiles and mosaics. Teachers assist but are under orders never to guide or instruct, unless asked to do so by an artist. Next door, connected to the studio, is the gallery, which holds seven exhibitions a year. For decades these openings were mainly attended by families and friends of the clients, and occasionally local professional artists, who might buy a painting or sculpture for a nominal price. They had the quality of a local flea market or open mike.

This began to change in the late 1980s, when the work of Dwight Mackintosh, who came to Creative Growth after spending 56 years in mental institutions, was noticed by John MacGregor, a Bay Area art historian. MacGregor was a popularizer of Art Brut, the term coined by the artist Jean Dubuffet to describe work created in solitude by untrained artists. At the time, Dubuffet’s Collection of Art Brut in Lausanne, Switzerland, founded in 1976, was the world’s only such museum; after learning of Mackintosh’s work from MacGregor, the museum gave the artist a one-man show. The few American gallerists who collected outsider art, like Phyllis Kind in New York and Judy Saslow in Chicago, began to buy Mackintosh’s drawings. A Warner Brothers executive noticed his work in Michael Stipe’s personal collection and commissioned the artist to illustrate a Lollapalooza concert poster. The sudden critical and economic success caught Creative Growth’s board by surprise. They knew how to sell work to members of the local community but were unprepared for Manhattan gallerists, rock stars and international dealers.

Photo

John Martin. Credit Jeff Minton for The New York Times Collectors began to visit the studio regularly, and work by other Creative Growth clients started to appear in group shows devoted to artists with disabilities. But it was not until 1999, when art critics began to praise the unusual, intricate sculptures of Judith Scott, a deaf and mute artist with Down syndrome, that Creative Growth’s board decided to change its mission. There was major interest in Scott’s work; there might also, it seemed, be a major market for it. If the professional art world was going to come to Creative Growth, the center needed to handle itself more professionally. It needed someone who understood the art market. It needed someone who knew how to sell.

Tom di Maria, who has been the director of Creative Growth since 2000, toured the studio at 9:30, greeting the artists as they entered the studio. Roughly 160 artists work at Creative Growth, but not everybody attends each day. Some, like William Tyler, have come every day for decades; others visit infrequently. Most are introduced to Creative Growth by the Regional Center of the East Bay, a nonprofit organization contracted by the state to provide services to people with developmental disabilities. Applicants do not need to express any artistic ability, inclination or even interest.

Di Maria often invites visitors to the gallery, and on this day he hosted an art collector and his wife, an interior designer, visiting from Santa Monica. The designer introduced herself to an artist named Monica Valentine. When the designer went to shake Valentine’s hand, she realized that Valentine was blind. Her eyes are prosthetics.

‘‘Can you see a little bit?’’ the interior designer asked.

‘‘I’m totally blind.’’

Valentine was dressed entirely in green: mint sneakers, lime socks, olive shirt, dusky green puffy jacket, emerald glass stud earrings, neon plastic sunglasses and a headband made out of interweaved strands of harlequin and laurel fabric. Around her neck hung, from chartreuse nylon, a green bicycle reflector.

Valentine covers foam packing forms with sequins and beads, held in place by sewing pins. The current piece was shaped like a cinder block. She called it ‘‘A Piece of Cake.’’ She hoped to be finished in time for her 60th birthday later that week. Before Valentine on the table were three plastic boxes, each with a half-dozen compartments. One box contained sequins, another beads, the third pins. With the dexterity of a veteran crocheter, she selected a pin, stuck it through a bead and a sequin and punched it into the foam. When a work is completed, the whiteness of the foam is almost entirely obscured beneath bright fields of color. Creative Growth’s gallery guide describes Valentine’s densely sparkling creations as ‘‘crown jewels of a lost disco civilization.’’

‘‘How can you tell the difference between colors?’’ the interior designer asked.

‘‘I feel them,’’ Valentine said.

‘‘Like ... they have different temperatures?’’

‘‘Blue is cold,’’ Valentine said. ‘‘Yellow is warm. Green is cool.’’

‘‘It’s so incredible that you can feel that. Because people who have eyesight can’t — ’’

‘‘Do you ride bicycles where you live?’’ Valentine asked.

The designer paused. ‘‘Where I live it’s really hilly, so I don’t,’’ she said. ‘‘I’m not strong enough.’’

Valentine showed the visitor her reflector necklace. ‘‘Do you like the reflector? What does it remind you of? Grass?’’

After the couple from Santa Monica left, Valentine called over one of the staff members, Kathleen Henderson.

‘‘What things are green, Kathleen? Can balloons be green?’’

‘‘Sure they can.’’

‘‘Can cars be green?’’

‘‘Yes, Monica. Cars can be green.’’

‘‘Kathleen?’’

‘‘Yes, Monica?’’

‘‘What things are red?’’

Photo

Dan Miller. Credit Jeff Minton for The New York Times ‘‘When the opportunity exists,’’ the Katzes wrote, ‘‘we have seen the creative impulse burst forth like a surge of floodwater when the dam has been removed. We have seen people cry when viewing their own work. We have seen the joy in their faces. ... We have seen, and we believe.’’

There is no better example of a dam being removed and a creative impulse bursting forth than the case of Judith Scott, who was brought to Creative Growth in 1987 by her fraternal twin sister, Joyce. The sisters were born outside of Cincinnati in 1943 and were reunited in California after 40 years apart. Judith never learned to speak, having lost her hearing in infancy from scarlet fever. Her deafness went undiagnosed for decades, so she never learned to speak or sign. Her muteness was attributed to low I.Q. Doctors advised the Scotts to institutionalize Judith and cease all contact. When the sisters were 7, their parents took Judith in the middle of the night from the bed she shared with Joyce and left her at the Columbus State Institution. Joyce, violating her mother’s wishes, visited the institution as an adult and found her sister distraught, living in near total isolation. When Judith showed an interest in creating art, her crayons were confiscated. According to Joyce, Judith was declared ‘‘too retarded to draw.’’

During her first two years at Creative Growth, Judith Scott appeared unengaged, occasionally making drawings but more often sitting blankly, or napping, at her worktable. It was not until she was placed in a textile course taught by the artist Sylvia Seventy that she began to wrap. She roamed through the center’s storeroom, gathering objects — a broom, a broken chair, a tissue box, bamboo slats — that she wrapped in twine, thread and yarn. The first sculpture she completed looked like two small human figures tied together. ‘‘I understood,’’ Joyce writes, in a forthcoming book about her sister, ‘‘that she, too, knew us as twins, together; two bodies joined as one. I wept.’’

Scott’s sculptures grew more elaborate with time. They attracted the attention of MacGregor, the art historian, who made her the subject of a 1999 monograph, ‘‘Metamorphosis.’’ The next year Creative Growth decided to hire di Maria as its new executive director. His chief duty would be to promote Scott’s work. Board members told di Maria that they thought her work might be important but didn’t know what to do with it.

They also explained that they now wanted their clients to be thought of not as artists with disabilities but as ‘‘contemporary artists.’’ Di Maria, who previously worked as assistant director of the Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive, didn’t have to be convinced. He was immediately taken by the merit of the work being produced at Creative Growth, he said. The center, he felt, also offered an escape from the pretensions of the art world. ‘‘It was pure,’’ he says. ‘‘I don’t mean to fetishize that word, but it’s true. They are using their work as a means to communicate.’’

Shortly after di Maria was hired, he received a visit from Lucienne Peiry, the director of Lausanne’s Collection of Art Brut, which had given Dwight Mackintosh his first major show. Peiry wanted to determine whether Scott fit Dubuffet’s definition of an outsider artist. After observing her closely for several days, Peiry concluded that, though Scott worked in a studio with other artists, she did not respond to them — preserving the sense of isolation and imperviousness to influence that was crucial to Dubuffet. Peiry made Scott the subject of a 2001 show, which later traveled to New York, Hong Kong and Tokyo.

With Joyce Scott’s blessing, di Maria increased the price of her sculptures from $200 apiece to $5,000, putting it in line with sculpture by other emerging contemporary artists who had appeared in a museum show. When the pieces sold quickly, he increased the price to $15,000. (Creative Growth, like most professional galleries, splits every sale evenly with the artist.) Scott’s work was the subject of a 2002 show at the Exploratorium in San Francisco and was featured at the Outsider Art Fairs in New York and Paris. Judith Scott’s heart gave out in 2005 while on a weekend retreat with her sister; she died in Joyce’s arms. Di Maria was never certain whether she understood that her work was being sold or even exhibited.

‘‘I was with her at two or three exhibitions of her work,’’ di Maria said. ‘‘She wasn’t so interested. If she’d see one of her sculptures, she would do this thing where she’d kind of pat it on the head, as if it were her little kid. She was interested when people came to the studio and watched her work. She would shake hands. I feel that she knew that people were paying increasing attention to her. I don’t know if she made the connection to the sculpture.’’

As William Tyler worked on a drawing, a touring group from a center for people with traumatic brain injuries paused to observe him. Tyler’s method is patient, glacial, precise. He pauses often to think, his head resting in his hand in a dreamy pose. He draws in black marker on white paper, creating ordered landscapes and portraits, many of them depicting him and his brother, Richard. The brothers worked at Creative Growth together until seven years ago, when, according to staff members, it was discovered that Richard was abusing William. They have not seen each other since, but in William’s drawings, Richard continues to appear as a smiling, beatific presence.

Tyler’s canvases are often dominated by lines of neat text, framed in black boxes, that reflect his obsessions: geography, crime news, dates and times, his fear of swimming, his love of magic. A storefront occupied the bottom left corner of his work in progress, beside a series of flags of his own invention. The rest of the canvas was taken up with text:

BAD MAN WAS SHOT A GOOD MAN AT LAKE MERRITT FOR GOLDEN STATE WARRIORS / PARADE IN DOWNTOWN IN OAKLAND, CA, ON FRIDAY, JUNE 19, 2015. / BAD MAN IN JAIL IN PRISON FOR RIGHT NOW FOR BAD PEOPLE. / POLICE OFFICER WAS TAKE A GUN FROM BAD MAN IN PAST FOR NOW.

Tyler is a dedicated watcher of television news. In the news that week was the mass murder at the Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, S.C., as well as a shooting during the victory parade for the Golden State Warriors’ N.B.A. championship.

‘‘You heard about the nice people in Charleston, South Carolina?’’ he asked me. ‘‘Man shot them. He’s a bad man. They put him in jail. Things happen for a reason.’’

I asked where he got his news.

‘‘Channel 11 news,’’ Tyler said. ‘‘Channel 7 news. Channel 71 news. Channel 72 news. Channel 75 news. CNN. Fox News. Weather.’’

ALL SWIMMINGS FOR BAD FUNNIES ARE AT POOLS AND BEACHES FOR RIGHT NOW. WHY! / DON’T LET HAPPEN AGAIN ABOUT SPORTS FANS AND SWIMMINGS FOR RIGHT NOW / AT ALL. / NO BUSINESS FOR BAD SPORTS FANS AND SWIMMINGS FOR RIGHT NOW AT ALL.

Tyler spoke about a trip he took with his brother to Hawaii. It was financed by money earned from his artwork. ‘‘Eight-day vacation,’’ he said. ‘‘Me and Richard went in 1988. We went to the National Memorial Cemetery. Pearl Harbor Museum. We had lunch at the pineapple field. I drank pineapple juice. At Hawaii Island we had pancakes with butter and banana syrup. We took Aloha Airlines to the Big Island, Hawaii. Ate lunch on the airplane.’’

NO NEWSPAPERS FOR RIGHT NOW WERE GOT THROW AWAY IN PAST. / DON’T FORGET A RECEIPTS FOR RIGHT NOW FOR EVERYONES. / BE HAPPIES FOR RIGHT NOW AT THIS REALITY FOR EVERYONES.

Tyler said that he was born on April 23, 1954, a Friday. He said that he grew up in Berkeley and lives in Union City. ‘‘Don’t get lost on this planet Earth,’’ he said. ‘‘Things happen for a reason.’’

Slide Show

SLIDE SHOW | 11 Photos Liberated Expression Liberated ExpressionCreditCreative Growth Art Center Writing 20 years ago in The New York Review of Books, the British critic Rosemary Dinnage described the allure of outsider art as ‘‘the fantasy that over there, on the other side of the insanity barrier, is a freedom and passion and color that were renounced in childhood.’’ Underlying 20th-century art, wrote Dinnage, was ‘‘the longing for a return to something direct and strong and primitive.’’ You can see this longing in the art of Paul Gauguin, Alberto Giacometti, Marcel Duchamp and André Breton — artists influenced by the work of indigenous tribes, children and patients of mental asylums. Max Ernst assembled a 1919 exhibition in Cologne, Germany, in which Dadaist work was set beside art by the clinically insane. The African tribal sculptures at the Musée d’Ethnographie du Trocadéro in Paris fascinated Pablo Picasso and Henri Matisse and led to transformations in their style. Paul Klee declared children, mental patients and North African tribesmen his artistic idols. ‘‘Neither childish behavior nor madness are insulting words,’’ he wrote. ‘‘All this is to be taken very seriously, more seriously than art of the public galleries, when it comes to reforming today’s art.’’ When the trappings of artistic fashion have come to be seen as restrictive, artists have sought the work of those ignorant of fashion.

Jean Dubuffet’s ‘‘Art Brut’’ designation was not an embrace of self-taught art so much as a rejection of its appropriation by conventional artists. Inspired by the Heidelberg psychiatrist Hanz Prinzhorn’s 1922 book, ‘‘Artistry of the Mentally Ill,’’ Dubuffet formulated a set of criteria to distinguish artwork made by society’s outsiders from work derivative of it: A true outsider artist had to work in total isolation, impervious to influence and unmotivated by any hunger for fame, status or profit. Over time Dubuffet saw reason to expand his criteria, however, and today no definition of ‘‘outsider art’’ withstands scrutiny; the two art worlds, outsider and insider, increasingly tend to bleed into each other. Even so, the fantasy of the notion of purity persists. It does more than persist. It sells.

The recent bull market for self-taught art has coincided with di Maria’s directorship of Creative Growth. Whether di Maria saw this market change coming or helped to bring it about, he understood that Creative Growth was poised to benefit from it. But first he had to establish the integrity of all the artists under his care — not just Judith Scott. He realized, as soon as he was made director, that major things would have to change. The studio space, for instance: After 18 years, it still looked like an auto-repair shop. ‘‘If the building doesn’t seem contemporary, the artists won’t seem contemporary,’’ he informed the board of trustees, shortly after he began. He began a $1.8 million fund-raising campaign and in 2008 hired the architect Anne Fougeron to create a more contemporary design, emphasizing natural light and clean lines. The gallery, which previously resembled an overstuffed attic, with unframed artwork covering every inch of the walls, was painted white. Exhibited works were framed and hung professionally, surrounded by plenty of blank space, as in a Chelsea gallery.

Newsletter Sign UpContinue reading the main story The New York Times Magazine The best of The New York Times Magazine delivered to your inbox every week, including exclusive feature stories, photography, columns and more.

Enter your email address Sign Up

You agree to receive occasional updates and special offers for The New York Times's products and services.

SEE SAMPLE PRIVACY POLICY OPT OUT OR CONTACT US ANYTIME The center had long been staffed by local art teachers, but state budget cuts in 2010 terminated that program. Given the opportunity to hire a new staff, di Maria selected exclusively professional artists and art administrators. ‘‘From me to the bookkeeper, we all went to art school,’’ he said. ‘‘No one has a social-services background or a psychiatric background. This is an important part of our philosophy: Artists should work with artists.’’

The final step was to gain prestigious institutional support for Creative Growth’s artists. As Scott’s work grew in renown, di Maria donated sculptures to the American Folk Art Museum, the Milwaukee Art Museum and the Collection of Art Brut, forming relationships that would benefit his other artists. He organized a widely attended conference in Oakland and pursued partnerships with collectors and galleries, like Matthew Higgs’s White Columns, which regularly includes Creative Growth artists in its exhibitions. In 2008 Creative Growth even opened a gallery in Paris, Galerie Impaire, to sell work more easily to European collectors. Di Maria also continued to raise prices. ‘‘In the contemporary art world,’’ he says, ‘‘if a work is priced too low, certain collectors won’t buy it. They assume that price is a signifier of value.’’ He learned that at his first Outsider Art Fair. The pieces on sale for $50 went unsold. Those priced at $1,000 sold out.

More recently Creative Growth entered a phase that di Maria refers to as ‘‘the Hollywood stuff.’’ The center collaborated with Marc Jacobs and Paper Magazine. Cindy Sherman and David Byrne hosted fund-raisers. T-shirts designed by Creative Growth artists have been modeled by Scarlett Johansson, Drew Barrymore and the Sports Illustrated swimsuit model Michelle Vawer. The Museum of Modern Art, after acquiring work by Scott for its permanent collection, has purchased paintings by Dan Miller and William Scott, who paints idealized portraits of African-American leaders, San Francisco and women from his church. This year Judith Scott was the subject of a major exhibition at the Brooklyn Museum. Her sculptures have now sold for as much as $45,000, and di Maria has declined offers more than three times as high.

It is not advertised, but the Creative Growth studio is open to the public. Most visitors who ask permission are allowed to observe the artists, and many of the artists welcome visitors. One recent afternoon, two white-haired collectors watched John Martin as he drew a tractor with a black Sharpie. Martin is tall and solidly built, with large hands and a friendly smile. On the table beside him, a small boombox played Ice Cube’s ‘‘It Was a Good Day.’’

‘‘Do you have a tractor like this?’’ Martin asked the couple.

The woman, supporting herself on a cane, pointed at Martin and whispered his name to her husband.

‘‘You can buy this tape,’’ Martin said, gesturing to his boombox. ‘‘You can put it in your car. I can’t tell you where you can get the tape.’’

He drew a man on the tractor, wearing a backward cap. He said it was Ice Cube.

‘‘I like his music,’’ Martin said. ‘‘I saw him on the TV set. I don’t have enough money for this man’s record.’’

Martin opened a Chinese magazine written entirely in Mandarin. It contained features on technology, business and culture. The elderly couple scrutinized his every movement, as if observing a living artwork.

‘‘It’s a book on Chinese food,’’ Martin said. ‘‘Let me see what they got on sale.’’

Photo

William Tyler. Credit Jeff Minton for The New York Times He flipped the pages. There were photographs of men giving speeches.

‘‘Where’s this restaurant? This says it’s in Chinatown. Let me see how much it costs.’’ He continued flipping until he came to images of food; a restaurant review, perhaps. ‘‘Stir-fried shrimp, $10,’’ Martin said. ‘‘I think they got shrimp, red lobster, stir-fried fish. Chicken chow mein. Meatballs, pasta, rice. Tomato sauce.’’

He returned to his drawing. He drew a single letter on each of Ice Cube’s teeth, copying the letters from a subscription form that had fallen out of Flash Art magazine. The letters were ‘‘v,’’ ‘‘d,’’ ‘‘w’’ and ‘‘f.’’ I asked what the letters stood for.

‘‘Music,’’ Martin said.

Visitors to Creative Growth, whether professional artists, collectors or curious passers-by, are invariably astonished by the amount of high-quality work being produced. ‘‘The best work made here is absolutely no different from the best work made anywhere,’’ says Lawrence Rinder, the director of the Berkeley Art Museum and the Pacific Film Archive. ‘‘I was the dean of an art school for four years. If we had the same percentage of success, we’d be the best art school in all of history.’’

What accounts for this unusual rate of success? Rinder credits ‘‘the character of these studios and the methodology that somehow inspires creativity at a consistent and high level.’’ The center does offer ideal working conditions. Stephen Beal, president of the California College of the Arts and former board president of Creative Growth, also cites them: ‘‘The flexibility they have, how they support an artist’s evolving way of working, who sits where, all those small things contribute to the quality that comes out of there. Maybe you’d get similar kinds of things out of everybody if you supported them that way.’’

Would you? Would you have the same results if you offered a Creative Growth residency to the next 160 people who walked down 24th Street? Creative Growth’s clients are not preselected for artistic talent. Many have never tried to make art before. Might it be possible that the work’s originality has something to do with the fact that those creating it have led unusual lives, under unusual pressures, which have caused them to view the world in unusual ways?

The question yields uneasy responses. Rinder rejects the idea forcefully. ‘‘Both instinctively and intellectually I try to separate that out.’’ Di Maria, however, acknowledges that a connection exists. ‘‘The culture of disability informs the voice of the work,’’ he says. ‘‘I’ll be in Japan, working with artists with Down syndrome, or I’ll be in Finland, working with artists on the autistic spectrum, and I’ll see similarities in style or form to artists with similar disabilities in other cultures. So maybe that’s its own culture, too.’’

Yet Creative Growth and its supporters tend to minimize the artists’ disabilities wherever possible. When asked to describe the center’s artists, di Maria even resists ‘‘self-trained artists.’’ ‘‘Work that doesn’t relate or respond to art history,’’ he says, ‘‘that’s how I describe what our artists do.’’ Di Maria routinely turns down invitations for exhibitions that emphasize the disabilities through artist photographs or biographical statements. Nor does Creative Growth participate in exhibitions that carry the label ‘‘Outsider Art,’’ with the notable exception of the annual Outsider Art Fair in New York, the field’s most prominent showcase. An extreme example of this approach was a recent show at the Fraenkel Gallery in San Francisco, ‘‘The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter,’’ which included no wall labels whatsoever. It was only by reading an informational pamphlet, available by request, that visitors could determine that some of the artists were from Creative Growth.

The effacement of biographical information avoids the danger of aestheticizing the disability or exploiting the disability to sell the work. But it also contravenes a dominant trend in the contemporary art scene. The artist’s biography and artist’s statement have become major marketing tools. Strong narratives sell. And Creative Growth artists tend to have profound, heartbreaking stories. Nearly every review of Judith Scott’s art, whether in The New Yorker or Artforum, leads with her life story. Di Maria is therefore put in the awkward situation of trying to de-emphasize the artist’s disability while recognizing that, for many collectors and critics, the disability is central to the work’s appeal.

Dan Miller was spending the afternoon in an action-painting class, in which the artists stood in front of upright canvases. Miller’s paintings are composed of words written on top of one another, creating dizzying palimpsests that bear some resemblance to Cy Twombly’s scrawled glyphs. He wrote the word ‘‘Grainger’’ in blank acrylic across the canvas. His uncle owned a Grainger hardware store. Words like ‘‘socket,’’ ‘‘pineboard’’ and ‘‘electrician’’ recur in his paintings.

‘‘You have character,’’ the instructor said. ‘‘That’s what’s great about your drawings. I can always tell it’s you. You have a signature style.’’

Over the black words, now a smudged nimbus, Miller painted, in green, ‘‘Home.’’

‘‘Home?’’ the instructor asked.

‘‘Home Depot,’’ Miller said.

When he finished a canvas, which took about 20 minutes, he chanted the word ‘‘paper’’ until the instructor brought him a new canvas, at which point Miller immediately began again.

Downstairs, Peter Salsman, an amiable former racecar driver who bears some resemblance to Kurt Vonnegut, was showing slides of his flowerpots on his iPad. The ceramic pots are decorated with irises, passionflowers and roses.

Photo

Monica Valentine. Credit Jeff Minton for The New York Times Salsman’s voice lowered. ‘‘I’m one of God’s angels,’’ he said. ‘‘I’ve been dead three times. I go to work at nighttime for God. I put people in the right place.’’

He paused.

‘‘God calls on me when I’m sleeping. If someone dies, I have to go collect them. Like when Classie passed away here, I went and picked her up in my ’55 Chevy.’’

Salsman pressed one hand to his temple.

‘‘I really take them to heaven and to hell. I have to go wherever I’m sent. It’s a lot of responsibility. Too much.’’

Miller appeared on the other side of the studio, accompanied by a staff member.

‘‘Costs a lot of money, right?’’ Miller said.

‘‘Yes,’’ she said. ‘‘It costs a lot of money.’’

‘‘Costs a lot of money, right?’’

‘‘Yes, Danny, it does.’’

Though some artists at Creative Growth do not understand that their work is sold at all, many know exactly how much their work is selling, or not selling. This introduces a new motivation into the studio. One artist mentioned that he had begun to paint trees because they were selling well. Another, disappointed by the quality of her ceramic sculptures, recommitted herself after she sold one. A third was so discouraged when her paintings didn’t sell that she gave up the medium. John Martin lies somewhere in the middle. He looks forward to the first of the month, when he receives his check for art sales, and complains about being broke. But the physical check itself means nothing to him. ‘‘What am I supposed to do with this?’’ he says. Sometimes he tears the check up.

What does the money do to the artists? The romantic view of a self-trained artist is one whose work, like Henry Darger’s, is not discovered until after his death. But when artists understand that their work is being appraised and sold in a marketplace, is such an arrangement still ‘‘pure’’? Does the artist’s awareness of the market compromise the value of the art itself?

To answer the question, you must first decide whether people with disabilities deserve special treatment — whether they should be shielded from the anxieties, frustrations and injustices of adult life. Disability theorists tend to agree that this sheltering impulse, while well intentioned, is a form of infantilization that denies its subjects’ humanity. The awareness of an art market that judges your work, subjectively and perhaps unfairly, can only cloud the motivations that lead Creative Growth artists to do the work they do. It leads to greed, disappointment and envy; also to affirmation, encouragement and pride. It leads, in other words, to life.

‘‘When you see a Creative Growth artist at an opening, they’re beaming because they’re accepted,’’ Beal says. ‘‘If you didn’t have that, would the engagement be as focused and sustained as it is?’’

Every artist receives a quarterly check from a common pot funded by sales of Creative Growth T-shirts and other items, an effort to counter money anxieties and to create the sense that all art has value. But some checks are bigger than others.

‘‘Money changes everything,’’ di Maria says. ‘‘But it’s also not my choice. It’s the artists’ choice, and I would never make decisions for them. If some of them want to enter the market and sign with commercial galleries or rent their own studio, it’s not my job to stand in the way. It may be that Creative Growth was a nice 40-year experiment and, in the future, it won’t need to continue.’’

It was the opening night of a new Creative Growth exhibition, ‘‘Parting Is Such Sorrow Until We Meet Again Tomorrow.’’ Included were elegiac portraits of Classie; paintings of trains and buses and bridges; a bright drawing in Prismacolor pencils by George Wilson of a crowd waving to a departing cruise ship; and several of John Martin’s flip-phone sculptures, made of wood.

Several artists had been asked to stay later than usual so that they could discuss their work. In exchange, they received envelopes containing $25. The attendees — among them professional artists, Berkeley art historians and wealthy collectors from San Mateo County in matching pastel outfits — inspected the work and chatted with di Maria. Occasionally a patron approached one of the artists (‘‘Show me which of these are yours.’’ ‘‘How did you get the idea to do that?’’), but most of the time the artists stood around uncertainly. Wilson, whether out of excitement or agitation or joy, began dancing to the music in the middle of the floor. It was a swaying, jittery kind of dance, like hula-hooping without the hoop.

Finally, it was too much. Wilson shot through the crowd, out of the gallery and into the darkened studio. A staff member followed him. Wilson sat at the nearest worktable and waited. The staffer retrieved Wilson’s current work in progress and his Prismacolor pencils and set them before him. For the next two hours, while in the adjacent room the music played, glasses of wine were poured and patrons discussed the art and the artists, Wilson drew.

0 notes

Text

Chapter 1: Cassiopeia

Chapter 1: Cassiopeia

The Showcase Special was a red brick building complex on Main and 6th in Corona, California. A concrete and metal sprawl jungle built in the mid 70’s. The shopping center the Special stood in housed a variety of Mexican botana markets selling treats, chile mangoes, pinatas and fire crackers. The Showcase Special bordered its north brick wall with a Coin-Op laundromat, next to that was a Chinese apothecary and foot massage day spa called the Jade where a 1 hour full body massages cost 20$ plus tip. The Chamber of commerce for the city was not sure what do with the plot of land, originally opening up the building area for venturing entrepreneurs and white businessmen, the shopping center became a mishmash of Central American check cashing and call centers, Chinese herb medicine women, an alcoholics anonymous coffee center, tweakers, prostitutes, punk rockers and skaters. So the city officials slowly let the line out on the potential for an upper crust shopping center and let it become the community hub of poor immigrants and transients nesting a run down strip mall with what little comforts they could establish from their former countries.

“Eso es un ‘gang bang’”

Armando, one of the taquero cooks on the flat-top grill of ‘Taco Super’ explained to Carl, the handicapped kid that frequented the strip mall daily. Armando laughed and looked over the dirty sneeze guard separating the clientele from the sweating cooks.

“How many friends you want for ‘gang bang’? Aguas Carlitos?”

Armando chuckled as he looked at Carls face trying to make out the sexual situation he described in detail.

“That’s gross Armando! Ewwwwwww!” Carl was starting to picture all the naked and perspiring bodies hovering over a taco and doing nasty things to it.

“Este pinche Carlitos ni sabe tetas!” Ener Montez, the chubby Mexican handling the boiling pots in the corner said without looking up from his slow and steady stirring.

Carl slapped his hands onto his thighs and kept a slowly burning yowl,

“How could you do that? EwwWWWWWwwwWW!”

Carl grabbed the neck of his tamarind soda and walked out the back exit of the taco shop as Armando and Ener continued cackling. The fly shield above the backdoor was old and blew loudly without providing the protection from the pestilent insects hovering above the hot pans of beef maws and tongue and carnitas and roasted serrano chiles and Carl walked out to the dumpster area where Moony was rolling a cigarette in his right hand and clasping a paper-bag wrapped bottle of whiskey in the other.

The Special was split into two businesses, by day the front foyer below the marquee served as a soda stand and record store, peddling beat up demoes in brown paper bags recorded in hot garages by shitty local teenage bands. The marquee lit up at night, blue fringe lining the white marble incandescent panels with stock black lettering displaying the weekly touring bands coming through town. The second business was a nightly affair, an all ages music venue that had no prejudice on what kind of weird and violent teenage angst was going to be screamed through the sound system. They had to constantly book acts, and the only way to pay for the overhead was to let them all play. Crust punks, smelling of plastic bottle, bottom shelf vodka would sew black and white patches to the only pair of jeans they owned around 5 o’clock in the evening, always with a dirty styrofoam cup begging for loose coin. The pyscho-billy kids walked around dripping of pomade and indifference that they had not been alive in the Greaser scene of the early 60’s, cuffed denim pants and smoothly combed hair that crested in an oily pompadour high fiving the sky and American Jesus in the clouds. The goths hated god, yuppies and nice cars, and made sure their eye-liner and black t-shirts reflected this sentiment on the off chance that a chipper ass soccer mom with a tight ass and a stroller full of impressionable toddlers crossed their paths. All the different kinds of metal kids hated being labeled a sub-genre of Metal that they were clearly not fans of. The Black Metal kids hated being associated with the drunk assholes that came to thrash metal shows, and the death metal kids never really said shit but hated all of the tools in the shed the same.

The gutter punks were friendly, usually playing a beat up guitar with 2 out of tune strings for money in front of the 99 Cent store so they could get a one of the many colorful homeless folk to buy them a 40 oz of Mad Dog or King Cobra. The homeless had their own rites and rituals and hierarchy of law on who slept in which dumpster lot and who would go to Cupids on Tuesdays to buy a bag of 99 cent hamburgers for the group, and who would suck a dealers dick for some smack and who would share the drugs, and who would keep a look out for the cops when they were using at the park or in the loading area behind the Special. The Cholos and Crazy Vatos Locos wore tight, sweat stained wife beaters and sagging baggy khakis and they were constantly seeking wandering eyes from a punk or metal kid so they could take his wallet or her purse and beat their ass. They carried around rolls of quarters they usually stole from the coin-op, they would hold the roll of quarters in their fists when they jumped some one, it was like getting hit in the face with a plank of wood, and cops couldn't confiscate it because it wasn't a gun or a blade. Most of the gangster Mexicans were kids, trying so hard to be hard, between the ages of 9 and 19, the older vatos were the scarier ones, old school cholo gangsters that got shit-faced on the weekends at a homies house, making carne asada and “pistiando” with chelas. There was an unspoken truce between the Mexican gangsters, the homeless drug addicts, the punkers and scenester kids, a mutual understanding of each others lot in this lower class social strata of suffering for scraps, they were in an accordance with one another, they hated the cops and rich yuppies.

Then there was Jay, an employee of the The Special record store and Soda stand. Working almost everyday from 10 in the morning until 5 at night, donning faded band shirts, glasses and a smoldering quiet demeanor, Jay stocked records, tapes and price tagged products and ran a paper printed cash out at the end of every shift. The Armenian owner of the Special, Rendy Smith Sami, was a kind man and a good boss, employing Jay for over 5 years and providing the only all ages venue and record store within a 100 mile radius. Jay would open the record store everyday, 4 aisles of halogen lit shiny plastic and vinyl, and everyday at 5, the daily sales button was hit on the register and the machine would buzz and chirp for 20 seconds carbon printing the haul for the day. Jay would wrap the cash out receipt around a small stack of 20 dollar bills walk up the stairs to Rendy’s office and drop it in the cash box outside his locked door. Everyday for 5 years, Jay would do this routine, with the carnival of characters and action right outside the doors of the special. Watching kids driving in from Anaheim and Los Angeles for a show that night, Jay watched them vigilantly, making sure they didn’t steal a secondhand Rick Springfield “Jesse’s Girl” single or a Donald Duck Pez dispenser.

Rendy was in the record store today, in the office, doing his weekly sales on a tattered spreadsheet, it was 4:55 in the afternoon and Jay was wiping down the soda counter and pouring a coffee for later.

Rendy came down the stairs from his office into the main aisle of records, pensively looking at the wooden display stands and holding his chubby chin with one hand, a look of frowned pondering wriggled its way onto his bushy eyebrows like a frightened caterpillar.

“We sell more CD discs than tapes Jay?”

He spoke a little louder than usual because the Addicts record that Jay had put on was still droning away on the store speakers.

“Just the older used ones, no one likes those new CDs you put out there. Shit is lame.” Jay didn’t look up from the cash register.

Rendy still had a puzzled look on his face, staring directly at the new Petunia Cooke albums he bought from his distributor. Petunia was hot, young and what little clothes she wore on the front of her Cd cover left his testosterone saturated Armenian imagination reeling.

“You no like Petunia?” Rendy asked with his eyes still fixed on the display stand and the pretty blonde pop-star on the front cover.

“She is sexy as hell, but i would rather put my head in the trash compactor than listen to that bullshit. It probably sounds the same.” Jay quickly glanced at the Petunia display stand.

“Sounds same? She sounds same as what?” Rendy was still imagining slow dancing with Ms. Cooke on a hill in the Armenian village he grew up in, under a gentle moonlight, the aroma of roast goat permeating the cool night air.

“She sounds like some one put her head in the trash compactor!” Jay held back a smirk and a giggle.

“Oh she sound like she dying, like she in the compactor.” His pronunciation of compactor sounded more like protractor, “she go ahhhhhh ahhhhh ahhhhh” partly screaming in pretend pain and trying to hit the high falsetto Petunia sings on her hit single “Candle Shade Babe”.

There was a ring of the bell above the front entrance door and a woman with slicked, crunchy hair sauntered briskly to the front counter where Jay was standing. She placed her briefcase on top of the glass counter without any regard to its flimsy and shitty craftsmanship.

“Where is your brother?” she said as she looked down into a yellow steno pad, scribbling nonsensical scratch.

Jay pushed the cash drawer of the register in until it made a click and rang a bell.

“He is out back with Moony, I mean Ronny I think…”

The staunch businesswomen slowed her writing and leered over the brims of her glasses with here piercing pupils and stared condescendingly at Jay,

“He is out back? Jaimie I need you both in here, I need to talk to Carl and his closest living relative and that is you, his sister.”

Rendy knew when the social worker for Jay and her brother Carl was here and when she meant business so he slipped out the fly trap of the back door and went to find Moony and Carl.

Ronny Maine was a 50 year old homeless man trapped in a 70 year olds’ decrepit body, resembling a leather bound book with pages hanging out the sides and corners. The years of amateur title boxing in Scotland had caught up with his rattling bones and stretched his sinewy tendons into a gelatin mush of heavy breathing and hand rolled cigarette juice. Everyone called him Moony because his big, puffy cheeks would get red and full when he drank and he looked like a smiling full moon.

“It is a pretty day when you stop blaming things and people for who you are. Stretch your arm.” Moony shook his left shoulder from the base and jiggled like a dying fish, “Your right arm as far as it can go. Go ahead. Take your right arm and stretch it out. Ain’t got a right arm?

Use your left arm.

Ain’t got arms anymore?

Use your legs and your toes.

Ain’t got legs no more?

Use your nose, or your eyebrows or your goddam tongue.”

Moony wasn't looking at anything but the sky behind the dumpster.

“I know you got a right arm, I see it right there, your right arm is right there boy!”

Moony’s own right arm pointed down ecstatically at Carl’s right arm, buried and sheltered by his black sweater and hunched right shoulder. Moony’s eyes spoke as loudly as his slow rolling mouth,

“Take your arm and shove it out straight like this

and point your finger straight at anything you want.” Moony kept pointing and building a louder voice.

“It’s not their fault, it’s not your fault, its nobodies fault, stop trying to put that weight on someone else. That weight, that shame, that pain, that twitch and tick was always there my boy. And you gonna have it until the good Lord Jesus calls you home, and you might even have it still there up in heaven.”

Carl slowly slid both of his arms from his bottom and dragged them on the concrete. He wriggled his fingers and wiggled them like it was the first time he had seen his own hands. Carl and Moony stood there by the dumpster for the better half of 3 minutes.

Carl made a maddening fist and then slowly let it go.

The red and strained skin released as veins fed to the rest of his appendages and bled into an off white color of skin he could recognize as normal. Moon took a swig off the brown bag in hist left hand and wiped 3 beads of slowly creeping sweat from his left eye brow without winking or squinting.

Carl became vocal and interjected loudly,

“This is not me and I am not me or you Moony… I am me” Carl proclaimed as he watched his hands.

Moony smiled.

“That’s exactly what Paco said to Harvey when both him and Harvey landed on the planet of Mandoloids. Tired and angry at one another. Being a bunch of assholes.”

Moony looked off at the wispy heat of clouds rising into evaporated nothing.

“Harvey and Paco had been in that junk heap of a space ship for the better half of 7 months, floating around out there in the Cassiopeia constellation system. Lots of big bright super nova’s and swirling and quiet space dust and they were stuck in this greasy sail ship of the sky.”

A wiry and subtle smile started to take shape at the right side of Carls mouth, “They were flying out there? They were flying out there in outer space huh? Moon? They were making dinners in the spaceship?”

Moony smiled with the bottle in his mouth and spilled cheap, bottom shelf whiskey on his chest.

“Hell yeah they were making all kinds of food on that spaceship, thats why it was so greasy. The both of them were on a mission, but the space council made sure they could eat all the things they liked. Plenty of helpings of canned beans and sauce and freeze dried pork bits and crispy plantain chips and banana mush. They had onions and potatoes and Paco would cook one night and Harvey would take kitchen duties, they ate really well, probably better than they would eat here on earth.”

Carls smirking mouth changed from a half built smile to him licking his lips,

“They eatin’ bananas and fried pork?”

“Not just that, they had 9 barrels of flour and oil so they could make tortillas and breads and they were eating a finer way than any of the kings and presidents and emperors here.” Harvey finished the last 2 sips of his whiskey,

“They had to eat well on the count of them searching for the Mandoloids and the bomb they were making. Harvey needed at least 8 hours of sleep and Paco couldn’t disarm a thing if he wasn’t eating good, wholesome meals.”

Rendy was standing to the left corner of the dumpster that Moony was standing and listening with a dumb smirk.

“When NASA disbanded and they became the Solar Security Agency, they were trying to protect our little rock from all the riffraff and space trash trying to hurt us. They sent these hunks of steel out from every part of the globe with two men, one was the Captain and the other was a disarmer. The Captain was older, seen some shit. The disarmer was younger, usually a Mexican, Black or Chinese and they were there to help the captain and cook and when the time came, they were there to disarm the Mandaloid planet bombs. Harvey and Paco were sent to the Cassiopeia constellation to hit every planet orbitting a star. The Mandoloids were vultures up in the desert sky but they killed planets and life before any other living thing could get to it. That was the real Space Race, that was what they were doing, they were protecting our futures.”

Rendy had a drawn out smile of a fool. He slid past the corner of Moony and gently placed his hand on Carls shoulder. Moony gave one nod, walked behind the green, beat up dumpster and Carl followed Rendy inside.

0 notes

Text

Good Friday Rambles – Warm Springs

I was visiting my brother, Houston, and his wife, Lynda. We were on a ramble across mid-Georgia, hoping to visit Warm Springs and tour the “Little White House.” We’d had several distractions along the way, and whether or not we would actually make it to Warm Springs was in question. Spoiler alert – we did make it. But not without a few more distractions, both coming and going.

We had spent some time in Madison and Monticello, but the day was getting away. We figured that without too many stops we could still arrive in Warm Springs with time to tour the site before closing. Yet, we were still following our route that avoided interstates.

Just outside the town of Griffin we had another distraction. As we entered town we passed through a very large cemetery on both sides of the road. To the right was a war memorial which featured the Spirit of the American Doughboy by E. M. Viquesney. We had seen one in Madison, and it was surprising to see this one relatively close.

I guess it stands to reason. When Viquesney started working on the sculpture he was living in Americus, Georgia. The first installation was at Furman University, but the original doughboy statue is in Nashville, Georgia.

I noticed that this memorial had been updated to include the “Global War on Terror.”

Next to the memorial was the Stonewall Confederate Cemetery. The land for the cemetery was donated by General Lewis Griffin, Confederate veteran and namesake of the town.

We continued on through the town then took the quickest route on down to Warm Springs. We started to see wide vistas, which surprised me quite a bit. It reminded me of the vistas of the High Hills of the Santee. We drove through the small town and found the Little White House. We got there in plenty of time for a tour of the site.

We started with a film narrated by Walter Cronkite, which should give you some indication of the age of the film. Regardless, it was very well done, and documented FDR’s time at Warm Springs. He had been diagnosed with polio in 1939 and had come to the area because of the purported healing qualities of the hot springs. FDR’s interactions with the local citizens shaped much of his policies for the new deal.

There was a small exhibit behind the theater with items belonging to FDR and Eleanor Roosevelt, including his blue convertible with hand controls that he drove through the countryside.

From there we walked on over to the Little White House residence. Just before getting to the small cottage there were a couple of sentry posts for Marine and Secret Service guards, as well as quarters for support staff.

As for the Little White House, its simplicity struck me. It stood in stark comparison to the ostentatious demands of the current administration. It also stood in stark comparison to the amount of history made in this humble cottage.

One thing I hadn’t spotted until just now was that the park employs many persons with handicaps.

Our last stop was to view the FDR portraits. FDR was sitting for a portrait by Elizabeth Shoumatoff on April 12, 1945 when he suffered a cerebral hemorrhage and died shortly thereafter. The portrait remained unfinished. Shoumatoff later completed another portrait of FDR from memory to honor the late president. Both paintings were on display in the Legacy Room of the park.

We stopped in the gift shop, bought a couple of expensive pecan rolls, and headed on for the next adventure.

The Little White House sits at the base of Pine Mountain. We drove to the top where there were spectacular views of the surrounding area. The road up and down the mountain was four-lane but very steep. From there we drove back into town.

Warm Springs has a weird dichotomy. The main street is lined with quaint stores, now mostly antique and curio shops. A large building houses a B&B.

However, take a stroll through Eleanor’s Alley and you wind up in a totally different world. Here you will find “Old Bullochville”, which was the original name for Warm Springs.

This is basically a faux town for bikers, with several bars and restaurants and lots of…rather strange stuff. It looks like most of this has been closed up for a long time because it’s starting to deteriorate.

There were some restaurants open, but nothing that caught our eye as far as dinner was concerned. In general, apart from the main street, the entire place looked like it was just about abandoned.

From Warm Springs we drove over to Roosevelt Warm Springs Institute for Rehabilitation. We were hoping to find the eponymous springs. However, what we found instead was a rather modern facility, and no springs. Most of the FDR era buildings were gone. There were historic cottages – some preserved, and some dilapidated. Water from the springs is now pumped into an indoor pool in the Ruzycki Center for Therapeutic Recreation, built in 1996. For whatever reason, I don’t have any photos of our drive through the institute.

We left Warm Springs for the long drive back to Watkinsville. For some reason the GPS took us on a slightly different route. We stopped for a moment in the town of Concord to take photos of some scenic buildings.

We encountered another one of Georgia’s scenic courthouses in the town of Zebulon, the county seat of Pike County. Yes, the town and county were named for Zebulon Pike, of Pike’s Peak fame, even though Pike had nothing to do with Georgia. He was hailed as a war hero after dying in the War of 1812 and towns around the country were named for him in his honor. Kind of like Washington or Lincoln, but now Pike’s exploits have faded from memory, with the exception of his peak in Colorado.

We had dinner just outside of Zebulon, then ran into a bit of a problem. A bridge was out over Lake Jackson, so we were re-routed. That turned out to be serendipitous. Our new route took us past a dramatic Rosenwald School. This one was either a five or seven teacher Nashville design, rather rare. The smaller Rosenwald Schools seem to have survived better than the larger ones. These were often torn down to free up land. So it was a pleasant surprise to find this one on Highway 36 in Butts County. We drove past it, then turned around to come back and photograph it in the setting sunlight.

Given the size of the school and some of the features such as a garage door, this may have been an African-American high school with vocational training. However, I can find no record of this school. GNIS doesn’t have a school listed at this location, and the Fisk University Rosenwald Database has no listing for Butts County. The building is far too large to have been moved from another site. This one is a mystery. Here’s a view of it from Google Earth:

By this time it was starting to get dark. Having hit one detour it was time to take the fastest route back, which involved I-20. I had been driving a LONG time and I was tired. It was a great day of exploration, but we still had a full weekend ahead of us.

from WordPress http://ift.tt/2pAWj8R

via IFTTT

0 notes