#and it's a really good program with a low recidivism

Text

okay i fixed the antigone uquiz result! the result is different now because i hadn’t saved anything in a document (fool me once) but i think i like this one better anyway. thank you to the wonderful anon who let me know!

#also ENTIRELY unrelated to the uquiz#i started my new job this week :)#i'm working for the department of corrections at a treatment center for offenders who have drug charges/addictions#and it's a really good program with a low recidivism#and it's not like 'oh they got caught with an ounce of weed' it's more like#these fellas have been charged with violent crimes that are related to their drug addictions#but i'm not even going to be a counselor there i'm just a fancy-titled secretary#ANYWAY i'm so excited to start#but i have a week of training and two weeks of basic at the academy first

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Working List of Media to Engage with if you want to get a start in Prison reform/abolition

The Holes book/movie (especially the sequel Small Steps) - It does not really get into the heart of the prison system especially with how racism shaped it but it's a good introduction to the basics of the US prison system. I can't find this one video essay that goes into depth about its commentary on the prison industrial complex but there are a lot of other essays about it that aren't hard to find should you research the topic. Not only that but it also is a fairly accurate representation of wilderness therapy programs without intending to be.

Angela Davis - Angela Davis is probably the best person to learn about the prison industrial complex. She was formerly imprisoned so she is a primary source on what prison is like especially about being a Black woman in prison. She has many articles and books about it and she also discusses Palestinians and their struggle with Israel.

The Innocence Project - the Innocence Project is an organization about liberating people from Death Row especially Black men who were falsely accused and forced onto Death Row. It focuses on how the death penalty is used as a tool in white supremacy while also working hard to exonerate wrongfully convicted people and they provide legal representation FOR FREE.

The Meow Mates/Mutt Mates Program - I want to clarify that the prisons that employ programs like these do still require immense reform but these programs showcase what prison SHOULD be: rehabilitation. The participants in this program not only get to have a companion in prison but it displays a lot of compassion that imprisoned people have and does a good job of humanizing incarcerated people. The prison industry thrives off people assuming that prison is made up of the worst of the worst. Meanwhile, these inmates have gone the extra mile of what was expected of them. In this video that I linked, there are men who paid attention to the behavior of their cats, noticed something was wrong, and they examined the cat's feces and discovered a worm problem. Most pet owners I know would not go to the lengths these men have gone to care for these cats. Not only are incarcerated people people but they also are learning important skills. These people can take these skills when they leave prison (if they are not serving a life sentence) and apply that to jobs in the real world with something they are truly passionate about. This program sets them up for success and to make sure they don't come back which reduces recidivism which PROTECTS people.

Research prison systems that have low recidivism rate like Norway's prison system - These prisons focus on the principle that the punishment is being locked up. They don't punish people further than that and focus on why the crime happened in the first place and how to prevent that in the future. The COs aren't in a separate walled off room watching incarcerated people like they're zoo animals. Their station is out in the open like a nurse's station would be. This builds a rapport between the COs and the incarcerated people where they can trust each other and work toward rehabilitation. It treats crime like both an individual and social issue instead of this prophecy that anyone who does crime will forever be a horrible irredeemable person.

Try and understand how recidivism reduction and prison reform protects people - We can talk till we're blue in the face about what people deserve prison and what people don't. But prison reform is not merely about making prisons better but it's about preventing people from going to prison in the first place. A lot of laws in place are there to protect people whether that be traffic laws or even something like criminal negligence. Obviously you don't want people killing others. Obviously you don't want people stealing from others. Obviously you don't want people joining gangs and hurting others. But a lot of this stuff can be prevented. That means supporting former foster children. That means supporting after school programs and summer programs for children whose parents work too much to help them. That means supporting a living wage. That means supporting unions. That means affordable healthcare and stronger social welfare. If someone has enough money to afford to eat and own a home and not be one paycheck away from homelessness, they're not going to need to steal. If a child has friends and mentors and a healthy support system, they're not going to need to join a gang. If a former foster child has a safety net should they fall on hard times and need support, they're not going to be thousands of dollars in debt and selling drugs. If sex work is legalized, then sex trafficking victims aren't going to worry about getting arrested for prostitution when they ask for help.

Understand that you ARE allowed to see some people as irredeemable but understand that those people make up a very small percentage of the prison population - It's okay to admit that some crimes are unforgivable. I think rape is unforgivable. You can never justify rape. Murder can be justified such as people killing their abusers or people defending themselves. But you can't justify rape. You can't rape someone out of self defense. You can't rape someone to escape a hostage situation. It is an irredeemable crimes at least in MY eyes and it's okay to see some crimes as inherently bad. You can have that opinion. I do. But the prison system we have today does not protect people from rapists. And if you want society to protect people from rape and murder and abuse, the prison system needs to change. The US prison system is not about justice, it's about vengeance. Particularly vengeance against Black people for the audacity to deserve freedom. Vengeance against trans people for the audacity to exist as their authentic selves. Vengeance against unhoused people for the audacity to not being able to survive a capitalist hellscape. Vengeance against gay/bi/pan people for the audacity to love. Vengeance against trafficking victims for the audacity to be threatened with their life for not selling their bodies to meet the whim of a person who doesn't give a shit if they live or die, just as long as they get paid. This system isn't about protecting society or avenging victims, it's about silencing minorities and controlling the population. This system will not save us, it will kill us if we don't change it.

#prison reform#prison abolition#justice not vengeance#protect children#prison reform protects children#acab#defund the police#abolish private prisons#defund private prisons

0 notes

Text

Speech given at the “Breakfast with the Mayor” event hosted by the West Appleton Chamber of Commerce

Good morning everyone. I did not know until this morning that I would be introducing the Mayor. I had actually just last week joined this august chamber, and am honored and excited to be with you this morning, even if only because of my wildly creative and partially false LinkedIn profile. So as a newcomer to these environs, my comments perforce with be brief. Or perhaps extensive. I have no idea. I have no written comments. This will be more of an appreciation than a dissertation. I thank you for this opportunity and will therefore strive to give life to this moment with appropriate exuberance.

Well what can I say about her honor that has not already been said? I really cannot say because I have never met the mayor. Is that her there? Hello. But to be sure—when a regal presence such as Mayor Grimsby enters the pantheon of the legendary leaders of West Appleton, one is immediately cognizant of the shoulders of the giants upon which she stands, and thus upon her shoulders are we all perched. Those small, fine-boned shoulders of freedom—though small of stature, she is mighty! And we will be hearing from her later, no doubt to update us on the excellent work they’re doing to fix the overpass, and the excitement surrounding the potable water initiative. No more crying children. Such progress!

When entering West Appleton, one is immediately struck by the flowering nature of this humble berg. Children, their tiny backpacks strapped to their compact bodies, line up for the bus, to take them past the treatment plant—and I think we can all agree that the superfund was a complete success in creating several lovely acres for them to play in. Three solid feet of non-toxic topsoil. There is nothing quite like the laughter of children.

Driving past the majestic falls, just off the interstate, one is struck by the lack of garbage and the old foaming green runoff that once sluiced in from the municipal department of neighboring Newton, is now a glinting pale yellow under the morning sun. The tax money for the litigation has certainly paid off there. Soon there will be a place for the old folks to sit and watch the falling water, and think of days gone by. Bygone days when that entire landscape was a horror show of industrial waste. And we have the mayor to thank for this.

Now I know the mayor is too humble to brag of this next achievement, but by donating the old Chandler place (that big old building by the post office that was just costing so much to maintain) to the Boys of Tomorrow halfway house program, she is providing a second chance to three entire floors of young men who will no longer be violent criminals, but instead will learn to be good citizens while taking classes and nature walks all around the main byways of West Appleton. Mayor Grimsler—Grimsby! Mayor Grimsby has approved programs for them to repay society by caring for the smaller children, working part-time in the cafeteria, and some of the larger boys will be put to work clearing brush. And we are all aware--all of us here in this room--of how much brush there is still yet to clear. So much brush! So by removing the handcuffs and security bars, they will learn the value of personal responsibility, with a very low….well, with a relatively low recidivism rate. Let’s beat 50-50! That’s the West Appleton way.

As I stand before you this morning, I’m suddenly overwhelmed. I see that several of you are checking your phones—it’s an exciting itinerary and I know you’re eager to learn what’s next. And what’s next, ladies and gentlemen, are my expert celebrity impressions and animal sounds. I know, this is a serious gathering, but once you hear my imitation of Brad Pitt making the sound of a rutting baboon, ok maybe we’ll save that one for Happy Hour. I already feel I’m one of you!

Aaaah-oocha! Ha ha ha. More of this tonight at the Rotary Club’s Dance for the Blind Society. I hope to “see” you there! Ha-ha. Ha. Oooh. Ha.

Ladies and Gentlemen, it is my honor to introduce…..Mayor Glimsley—Grimsby! Grimsby. Thank you. Good morning.

0 notes

Text

Marinette did not sign up for this part 4

hey, so OG chapter 4 will now be chapter 5 as the gremlins hijacked this chapter.

part one here previous part here ao3 here

--

Damian stared in quiet horror as he looked over Ladybug’s exploits after hacking into Paris’ servers. His sister—the one he took down with little effort—had been defending the city for a month before he appeared. From the video of “Stoneheart” he could tell she was given no training. And her partner was flirting with her! When he should be focusing on the mission!

What gathered from further research was the following: his sister and her ‘partner’ were untrained. Their teammates were also untrained. A team of ten untrained teenagers—perhaps younger—were tasked with keeping a villainous coward from stealing their magic artifacts, and with stealing his in turn. A team lead by his sister. A very alone, scared girl from his one interaction with her. Smart (he saw now she knew how to save her own skin. Redirecting his attention was a good move at the time). She is smart and creative because if she isn’t, then her city and her will lose. Be under the control of some madman.

He had to get there, and he doubted he could convince Jon to help him at the moment—why are kyptonians always fighting one another when you need the assistance of one?

Father would stop him.

The League was keeping Father in Gotham and he didn’t have individual access yet…

He was stuck for the moment, and did not like it. Perhaps Grayson could prove useful? He’d ask once the man was done resting from patrol.

---------

Cass was enjoying Paris. She spotted the possible sister at the bakery with her adoptive mother. They were happy. Cass likes that.

Cass moved quickly through the crowd, managing to make it to the bakery.

Marinette ran into her.

“Ah! Sorry!” the girl managed to catch her things before they hit the ground.

Cass waved her hands, indicating there was no harm or foul. The girl was no clumsy—Shifu Cheng was ill-informed. Those reflexes and her expression before indicated nothing but an intense focus on something else. On what, Cass wasn’t sure.

Yet.

For now, Cass took a seat in the bakery, smiling at the kind woman working the front. Sabine Cheng, the woman who raised the maybe-Bat.

Cass began doing her own research, messaging Babs that she saw Soup Girl for a moment, and would be assessing her parents. She knew of cases in Gotham where things weren’t always right, and she wanted to be certain that this girl was safe, regardless of if she’s a Bat or not.

--------

Tim decided to ignore Babs offer in the end. The possibility of owing Jason was low given both him and Cass are on the Case. Jason is good, don’t get him wrong, but the chances of Jason actually talking to the girl in a real conversation before the rest of them? As Red Hood?

This is a calculated risk and the odd are in Tim’s favor. (Well, not in Jason's.)

--------

Steph hummed as she went over the designer pool she was looking over. Shockingly low given its Paris—granted 200 girls is a lot to investigate… she didn’t give the others all the information she had though.

According to Damian, she “posts a disgusting amount” which means she’s posting or tagged often. When she used some of Babs old filtering program with social media involved, it brought the candidates down to 30. She could go through thirty teenage designers social media and comb over who at least has some genes that are dominant from the Wayne side. Her natural hair had to be medium brunette at the lightest, so the natural blondes took out seven candidates right off the bat. While blue or green eyes would give them more priority on the list, eye color genes are weird. Weirdly, five of her candidates had attached earlobes, so she only had 18 left after that filter was put on… Bruce’s hair isn’t curly, so two girls with intensely curly natural hair were taken off the list. Bruce’s thin lips only knocked out two more candidates.

That left Stephanie Brown with 14 designers in Paris to find and investigate in the right age range, because she doesn’t think Bruce started having sex at 15, unlike Tim who is allowing college kids into his ‘could be Bruce’s daughter’ mix.

Stephanie is also going to need a plane ticket to meet these girls, and that means getting help from one of Wayne kids… Or stowing away on the private jet that she knows Tim can and will be using sometime today to do ground work himself.

She’s cool stowing away—Babs is covering for her on principle since Tim wouldn’t take the deal. Steph was smart enough to relinquish one piece of blackmail in total in exchange for use of Babs filtering tech—she has more than that thanks to one Supergirl spilling a number of things Babs has done over the years. Has Stephanie mentioned she’s the only one of the Bats to listen to Oracle, Queen of Technology, in this bet? She is, and she is better for it.

-----------

Marinette managed to make it to the Agrests Mansion with little issue this time. Today she was going to one of the production lines with Gabriel to learn how to reset the machines and program them to follow any simple stitch pattern she wanted. It was good.

She also noticed that during none of her times with Gabriel, was there a single akuma sighting. Not an attack—those never happened anywhere near their time together. It was an… interesting pattern. She was beginning to suspect that if Hawkmoth wasn’t Gabriel (he was akumatized, it can’t be him. Get that theory out of your head Marinette), then it had to be someone who worked for him, and high on the food chain.

She made sure to memorize each of his ‘supervising managers’ and partners’ names. One of them had to be Hawkmoth. And Gabriel had to be someone that this Hawkmoth either really respected or really didn’t want handle re-scheduling with. Which would be all of them…

She really wished she had more time to dig into their lives herself. For now, she had to trust Max and Markov to do the research… which reminded her, her name had been pinged on multiple searches in Gotham last night. From numerous devices. If the Bats were planning anything…

Marinette gripped her purse a bit tighter. Her team has her back. She just doesn’t want them caught up in this mess too. She wishes that Aquaman never showed up. If he hadn’t, then the Bats wouldn’t be looking into her civilian life, the one they already knew about but only now deemed worthy of their attention.

She wished they would just stop—she won’t look into the Great Detectives. She knows she’s not one of them. That she wouldn’t hack it in Gotham. But Damnit, in Paris? Her Territory—she does more than hack it. Sure, she may have blown herself up that one time, and yes, there is the timeline where as Princess Justice she may have sort of broke the world by forcing it to conform to that akumatized version of hers’ idea of Absolute Justice (apparently she was ruthless, made no exceptions and took out a third of the Justice League using Multimouse at the time on top of it all). Yes, she is not a perfect leader. Or hero. But Damnit, her (admittedly two) supervillians have been almost caught twice. Her re-akumatazation rate is much lower than any of the Justice League’s heroes’ normal villain or general crime recidivism rate by more than a little. By a lot. She’s not some Detective but she’s a damn good strategist, a champion at improvising and she and her team do work with the public and victims and reworked so much of Paris’ social culture to lower akuma-creating circumstances and keep the public emotionally healthy.

She’s no detective.

She’s a Guardian. That means caring about the details that shift the bigger pieces. That means adaption with what is there and creating what she needs. That means knowing her limits and getting help—to set an example and prove that not even her or Chat are an island. That even superheroes need help, need others and need to work together.

She’s no detective. Detectives work alone.

Her? She’s forged a team that (she hopes) could become the new Order of Gaurdians with her… some day. For now, they’re heroes with the same mission and different roles to play.

Marinette just wishes that she could shut up this hunch since its been disproven. Her instincts on guilt and possible baddies aren’t the best—Adrien’s job is to sense what’s wrong and take them out. Hers is to make whatever is needed to help fix things, to push someone forward and help them grow. Her job to craft a better tomorrow today… and to do that, she lost the parts of her that picked up Danger. She can still find Caution signs (and her anxiety will always invent danger) but real Danger detection went to Adrien when she agreed to become Ladybug in the first place… And until both her and Adrien renounce their roles as the pair wielding the Ladybug and Black Cat miraculouses, she’ll always be missing it.

The same way Adrien is missing his ability to think outside the box—seeing things as what they could become to help them went to her. He can only see potential threat and act on them. She can only see potential aide and act on that.

---------

Jason grinned when he managed to make it into Paris. The second there was some damn akuma attack, he was grabbing the baby Bat and hunting Hawkmoth his way—she need the jewelry? Fine. She can have it. The guy brainwashing kids? The one that slaughtered the city? He’s Jason’s.

---------

Bruce didn’t like being benched. He doesn’t like not knowing he had another child. He especially doesn’t like that this one is constantly preventing an apocalypse and his allies can’t be bothered to even send him anything about it. Not even a basic ‘she’s not living on the streets’ like Jason did. Or ‘she’s got parents here, calm down’ so he could get this stupid instinct to storm Paris and take on the bastard threatening his family that he didn’t know he had.

Apparently Barbra has a hunch, but isn’t sharing until she has “conclusive evidence” of his daughter’s identity. Damian just isn’t speaking of it. As if being someone’s father biologically gives him a built-in alarm system for when he’s had a child and the ability to track them down at birth. Damian being raised in the League of Assassins should be enough proof to the contrary there.

The others were… he wasn’t absolutely certain, but fairly certain his self-proclaimed ‘middle kid club’ were tracking his missing daughter down themselves. Possibly to claim her as part of their group, specifically.

God, she was so young, It was before he even heard of the League that she was born. In that lifetime before becoming Batman. Would she like him? He was absent her whole life—did she want to meet him, meet the family? They’re a mess, he knows it. But they’re his—he chose them and they chose him. Would she chose him too?

He watched another video of Ladybug in her early days, before she and her partner (dear god he’s cat-themed. Is it genetic? Should he test her and himself for some ‘drawn to dresses-as-a-cat’ gene?) were given any kind of training.

She blew herself up to stop her city from being taken over by ‘Animan’ and his creatures.

His daughter.

Exploded.

(She died. She died and he didn’t know. God he’s a horrible parent, and he hasn’t even parented her yet.)

She died.

To keep her city safe.

She somehow reconstituted. But her face, in that video, she was shocked.

His daughter should be dead but she’s not.

Magic, he’s so glad his daughter uses magic.

He. He’s going to need to consult someone. Raven? Raven should work. He can’t talk to the Justice League—nothing wrong with talking to the half-demon all of his Robins that lead the Titans has worked with.

Loopholes.

The Justice League is horrible at closing them.

---------

Dick wanted to be mad when Damian came clean to him about the needles. He wanted to freak out over almost losing a sister he hasn’t met.

He did.

But.

But this is Damian.

Damian who still has trouble connecting. Who still flinches at certain tones of voice and phrasing. Damian who desperately wants to do Good but… struggles.

Damian who has all of Bruce’s communication problems and then some.

So no, Dick did not scream when he found out Damian only sparred “the blood daughter” because she looked too frail and weak for her to be considered anything resembling a threat to him. He did not sigh when he found out that Bruce didn’t know when Damian assumed he did. He did not hit himself when Damian discussed the various weapons he’d gifted her as a apology with the bouquets over the years and their meanings.

He did take a deep breath, and begin explaining from this baby bat’s stance what had happened.

“Imagine for a moment that it was me before I became Robin, and I was almost killed by someone who only let me live if I never contacted a shared parent or that parent’s known family. How do you think Pre-Robin me would have responded?”

“You would have feared for your life and done whatever you could to prevent contact.”

“Now, imagine I wasn’t told who to be avoiding, only aliases.”

“You would avoid everyone with an alias that you did not help them create, and keep them from unknown aliases.”

Dick snapped his fingers. “Exactly. That’s what this sister, what are we calling her?”

“Her alias is Ladybug.”

“Yes, that is what Ladybug was going through before Aquaman made contact.”

Damian was quiet for a moment. “She must be on edge.”

Dick nodded at that. “She probably is.”

Damian furrowed his brow. “Do you think the League would allow me to contact her and end our agreement?”

Dick rubbed the back of his neck. “I’m not sure, but we can try.”

“… And if they refuse?”

“Then we find another way. We’re Bats,” Dick reassured Damian. He just hoped the missing members weren’t doing anything too rash…

-----------------

Marinette made a (painful) decision. Adrien and her would swap miraculouses—at least until there were less pings on her sites from Gotham. For added protection, she kept the Mouse miraculous on. Chatte Noire was less known, and she doubted Wonder Woman or Aquaman informed Batman about the miraculous of Creation and Destruction’s particular… refusal to let anyone but a pair chosen together to wield them at any point.

Chatte Noire would only be on call for a day or so… what’s the worst that can happen?

--------

the characters are jinxing themselves, and procrastinating the (vague) plot of Shenanigans. i swear.

if anyone can message me on how to add in a read more, that’d be great since i know these can get long to scroll past for mobile users.

@heldtogetherbysafetypins @laurcad123 @raisuke06 @chaosace @jeminiikrystal @toodaloo-kangaroo @kris-pines04 @laurcad123

#maribat#bio!dad bruce#marinette did not sign up for this#part 4#long post#my writing#i hate formatting#how do i tag

120 notes

·

View notes

Text

Happiest Place on Earth

Logan x MC (Ellie)

Summary: Logan and Ellie go to Disneyland.

Now with Epilogue

Word count: 2500

Ellie lounges in her childhood bed, already dressed in her sleep shorts and tank top despite the fact that it’s only 8 pm. She’s currently unemployed, so her sleep schedule is a little off. Ellie really wishes she could land a job. Being out of her father’s house for four years and then returning to discover he still treats her like a child makes her wish she could afford to pay rent and move. Ellie lets out an impatient sigh as she continues to wait for her Grubhub order to finally arrive. Sure, LA is notorious for its terrible traffic, but this wait is ridiculous! She regrets pre-tipping the driver in the app.

The doorbell rings. “Finally.” Ellie mutters to herself, quickly running down the stairs and flinging the door open. She freezes, eyes widening as she takes him in, just casually standing on her father’s door step.

Logan smiles sheepishly. “Hey troublemaker.”

Ellie wants to simultaneously kiss him and slap him, but she’s rooted to her spot. It’s been over 4 years since she’s heard a word from him, since he ran after promising her he was done running.

Ellie crosses her arms over her chest, feeling defensive as she drinks in his manlier frame, the light stubble on his chin, the weariness in his eyes. “What are you doing here Logan?” Ellie questions.

Logan shoves his hands in his jean pockets. “I wanted to see you.” He replies softly.

“You wanted to see me?” Ellie asks incredulously, tears welling in her eyes. “You left me Logan! You ran and stayed away for years without even so much as a letter to tell me you were okay! I loved you so much, I would have run with you if you just asked.” Ellie whimpers, wiping furiously at the tears streaming down her cheeks.

Logan takes her face in his hands and wipes her tears away with his calloused thumbs. “You had to go to school, get back on the right path. And I didn’t run. I would never run from you.” He reveals.

Ellie looks up at him with watery eyes. “What?” She questions.

Logan smiles sadly, his thumb brushing over her bottom lip. “I turned myself in Ellie.” He explains. “I served my time. I just got out two days ago. I’m in a halfway house now, it’s an anti-recidivism program I got into because of my good behavior when I was in jail. They hook you up with a job with a company run by a former felon, someone who gets it.” Logan adds.

“Why didn’t you tell me? I would have visited you, I would have written you letters every day. I would have waited for you Logan.” Ellie insists, burying her face into his chest and hugging his waist as she pictures him all alone in jail while she was out enjoying college.

His arms encircle her shoulders, returning her embrace. “I know troublemaker, that’s why I didn’t tell you. I didn’t want to imprison you too.” Logan responds. “But now I’m out, and you’re done with school, and if you’ll have me, I’d like to start fresh.” Logan offers sheepishly, loosening his hold so he can look down at her. “Assuming you’re not seeing anybody. I checked your Facebook, and it said you were single. I don’t know if that’s current though…” Logan trails off.

Ellie lets him sweat for a moment before answering his question. “You’re in luck. I recently broke up with my ex-boyfriend. He said he didn’t want to do long distance after graduation, even though he got a job in San Diego. I guess 120 miles is too much to overcome.”

“He’s an idiot to let you go. If you give me another chance, I’ll love you the way you deserve.” Logan says reverently.

“And no more secrets? You promise this time?” Ellie prompts.

“Secretly turning myself in is the last secret, I swear.” Logan responds, feeling encouraged when he starts to lean down to her lips and she doesn’t pull away.

Ellie closes the distance, pushing herself onto her tiptoes and weaving her fingers through his now shorter, but still long, hair. Both their mouths open and their tongues tangle together as he grips her waist, hauling her completely against him. It’s like all the time they’ve spent apart melts away as they kiss. He left an imprint on her, and now, back in his arms, she finally feels whole again.

Logan pulls away when he needs to breathe, but he can’t stay away for long, pressing a quick peck to her kiss swollen lips. “Is your dad home?” He questions, hands slipping under her tank top and trailing over the soft skin of her lower back.

“He’s working a night shift.” Ellie replies, watching the glint that appears in Logan’s eyes when he realizes they have the place to themselves.

Logan steps into the house, making sure to lock the door behind him before gathering Ellie into his arms and hurrying up to her room.

30 minutes later, Ellie’s food finally arrives. But she’s a little preoccupied, so the delivery driver leaves it on the porch.

…

..

6 months later

“I thought you said the lines wouldn’t be bad in February Ellie.” Logan complains, leaning against the railing as they continue to wait to board Space Mountain.

“This isn’t bad at all. In the summer, these lines can be up to 3 hours.” Ellie responds, and then she tries to soothe his slight irritation by looping her arms around his neck, leaning up to kiss him softly “I promise you it will be worth it. I wouldn’t lead you wrong on your very first trip to Disneyland.”

Ellie had insisted on getting them tickets for his birthday after finding out he had never been. Logan had tried to convince her that the money would be better spend saving up for rent for when they got an apartment together, but his girlfriend was undeterred. He only has 3 more months until he can leave the halfway house, no more curfew, no more parole, he’ll be truly free. Ellie got a job a few months ago, working as a consultant. She doesn’t love it, but it pays pretty well. Her income coupled with what he makes as a mechanic means they can afford a one bedroom in a LA suburb. To Logan, it feels like things are finally starting to fall into place.

Logan smiles when Ellie breaks the kiss, pulling her back in for another more passionate one. Ellie pulls away after a few seconds. “Watch the PDA. There are children present.” Ellie gestures to the little girl waiting in line in front of them with her mother. The little girl’s attention is firmly on the pair of them as her mother seems to be busy on the phone. Logan smiles at her and the girl blushes and looks away.

“No, that’s not what I told him. I don’t know where he got that price point, it’s way too low, it’s not going to work.” The stressed out mother mutters into the phone, massaging her temples. “I’m aware of that Charles.” She spits out, pressing her cell phone more firmly to her ear in an attempt to drown out the loud sounds of the theme park. “What? I can’t hear you. Wait, one second.” The mother turns to Ellie and Logan. “I hate to have to ask this, but can you keep an eye on her for a few minutes while I take this call? You guys look like a wholesome couple.” The mother pleads.

Ellie nods. “Of course, we’ll take good care of her.”

The mother offers an appreciative smile at the young pair before she hurries off. Ellie turns to Logan. “Did you hear that? Wholesome! We should report that back to your parole officer.” She whispers, smirking at him.

“I don’t think I’ve ever been called wholesome before. Forget my parole officer, we need to tell your dad.” Logan retorts quietly. Detective Wheeler still isn’t a fan of Logan. He’s spent quite a bit of time trying to talk Ellie out of moving in with him, to no avail.

“I bet it’s our matching Disneyland sweatshirts and the ears giving off the wholesome vibe. Isn’t that well worth the $150 you had to spend, since you insisted on buying mine for me?”

Logan winces slightly as he remembers seeing that ridiculously high number come up on the gift store cash register. “That was a little steep for the apparel, but if it makes you happy it was worth it. Your happiness is priceless.” Logan’s charm comes through, as always.

Elle grins at him, giving him a chaste kiss. Normally, a sweet comment like that would have earned him a steamy make out session, but they’re in the middle of babysitting.

Ellie squats down to the little girl’s level. “Hi, I’m Ellie. And he’s Logan.” Logan offers a wave when Ellie points at him.

The girl smiles at them. “Hi, I’m Katie.” She says shyly.

“So Katie, what’s your favorite ride?” Ellie asks.

Katie grins. “It’s A Small World. What’s your’s?”

“I can’t possibly pick just one, that’s like asking me to pick a favorite child. I love Disneyland in general.” Ellie answers.

“What’s your favorite?” Katie directs her question at Logan, who rubs behind his neck sheepishly.

“Well, so far I’ve been on the Pirates of the Caribbean one and It’s a Small World, so the Pirates one I guess.”

Katie’s jaw drops. “This is your first time at Disneyland? But you’re old!”

“22 – I mean 23” Logan corrects when he remembers that he is in fact 23 today “isn’t that old.” He says somewhat defensively, but he’s just playing at being offended. He crouches down next to Ellie to be eye level with Katie. “How old are you?” He asks.

Katie puts up 5 fingers triumphantly.

“Have you started school yet?” Ellie asks, and Katie nods excitedly. “What’s your favorite part?”

Katie has a lot to say on the subject, and the conversation flows until her mother returns. “Thank you.” She mouths at the pair as she and Katie turn away from the pair to continue waiting.

Ellie turns back to Logan, trying to decipher what the look he’s giving her means. “What?” She finally asks when she realizes she has no idea why he’s looking at her like that.

“You’re going to be a really great mom when we have babies.” He comments, pulling her into his arms.

Ellie loops her arms around his neck, playing with the hair at the nape of his neck. “When? Not if? You’re awfully confident.” Ellie teases.

“I know that you love me, you’re not going anywhere.” Logan teases back, kissing the bridge of her nose. It tickles a little, causing Ellie’s nose to wrinkle. He smiles softly, allowing his eyes to close before capturing her lips this time.

She pulls away slightly after a few moments, speaking against his lips. “How many kids will we have?” She asks.

“I don’t know, I think a lot though. Like, 8 or 9.” Logan answers.

Ellie steps back in surprise. “8 or 9? That’s easy for you to say. You don’t have to carry them around, or push them out.”

Logan smirks, gripping her hand and pulling her to him again. “Not all biologically our’s Ellie. I do want 2 or 3 biological kids though. I want them to look like you, and be smart like you.” Logan reveals, resting his head atop her’s as he hugs her to him.

He can feel her smile against his neck. “I hope they’re kind and brave like you. And I hope they get your hair.” Ellie responds, tangling her hands in his soft locks. He’s growing it out again.

“Oh, they will. My hair genes are strong.” Logan teases, dropping a kiss to the top of her head.

Ellie looks up at him. “So what about the other 6 or 7 kids? Adopted?” Ellie asks.

“I was thinking fostered, actually. So it’s not like we’d have 9 kids in the house at one time. That would be a lot. I was placed in homes with 8 other kids sometimes, and it definitely wasn’t ideal. I think we’d be great foster parents, and there are a lot of bad ones out there, trust me on that one.” Logan reminisces on his own childhood in foster care, and Ellie squeezes him comfortingly.

“How does foster care work? If they wanted to stay permanently, could we adopt them?” Ellie questions.

“Well, the hope is always that their parents get their stuff together and reunite with their kid, but that doesn’t always happen. So in that case, we could adopt them out of foster care.” Logan answers.

“This is important to you, isn’t it?” Ellie asks.

“Yeah, it is. I want to give a foster child the kind of loving home environment that I wanted.” Logan replies.

“Then I’m 100% on board. Although we have a lot of steps to go before we start seriously considering kids. We have to move in together first, make sure we don’t actually hate each other.”

“I could never hate you. I love every single thing about you Ellie Wheeler. You think I would wear these stupid Mickey Mouse ears for just anyone?”

Ellie laughs, leaning in to kiss him. “I love you too.” She promises between increasingly passionate kisses. As they kiss, Ellie starts to envision the future he’s painted. Their future family. Family trips to Disneyland. Tears prickle at the back of her eyes with the knowledge of how much she wants that with him, how much she loves him.

Ellie pulls away from him. “Let’s get out of here for a little bit. I want to be alone.” She says suggestively.

Logan gestures to Space Mountain, they’re almost to the front of the line now. “I thought you wanted to ride this.”

“I’d rather ride you.” She whispers in his ear, delighting in the way he shivers at her words.

Logan grips her hand, leading her out of the line and to his car with the dark tinted back windows.

…

..

.

An hour later, the two lay cuddled up in the backseat of Logan’s Devore GT, their clothes scattered all over the car. “You ready to go back in there?” Logan asks, idly tracing patterns over Ellie’s ribcage.

Ellie gently runs her thumb over the smudged stamp on his hand to allow them re-entry to the park. “I want to stay here for just a little bit longer.” She answers.

Logan kisses her forehead. “No complaints here.”

They lay in contented silence for a few moments before Ellie breaks the quiet. “You know, it’s funny you skipped marriage talk and went straight to kids.” She comments, gazing into his eyes.

Logan arches an eyebrow. “I thought marriage was implied. Let me clarify for you, I do in fact want to marry you Ellie Wheeler.”

Ellie blushes despite herself at hearing him admit that so earnestly. “I want to marry you too.” She returns, kissing him softly. “But don’t think that that counts as a proposal Logan. I want the whole thing, big public romantic gesture and all.”

“Like a Disneyland proposal?” Logan questions softly, smirking when she looks at him with wide eyes.

taglist: @choicesarehard @ifyouseekheart @brightpinkpeppercorn @regina-and-happiness @drakexnadira @flyawayboo

@fairydustandsarcasm @alesana45 @umiumichan @maxwellsquidsuit @lahelable @god-save-the-keen @mrsmckenziesworld @paisleylovergirl @iplaydrake @sinclaire-made-me-sin @hazah @lovehugsandcandy @desiree-0816 @cora-nova @justdani14 @lady-dianelewis @emceesynonymroll @emichelle @badchoicesposts @client-327 @riverrune @liamzigmichael4ever @princessstellaris @mrskaneko

94 notes

·

View notes

Text

Morris Hoffman, Therapeutic Jurisprudence, Neo-Rehabilitationism, and Judicial Collectivism: The Least Dangerous Branch Becomes The Most Dangerous, 29 Fordham Urb L J 2063 (2002)

Introduction

The movement that calls itself "therapeutic jurisprudence"' is both ineffective and dangerous, in almost the same way that its predecessor—the rehabilitative movement that became popular in the 1930s and was abandoned in the 1970s—was both ineffective and dangerous. Drug use, shoplifting, and graffiti are no more treatable today than juvenile delinquency was treatable in the 1930s. The renewed fiction that complex human behaviors can be dealt with as if they are simple diseases gives the judicial branch the same kind of unchecked and ineffective powers that led to the abandonment of the rehabilitative ideal in the 1970s. In fact, this new strain of rehabilitationism has produced a judiciary more intrusive, more institutionally insensitive and therefore more dangerous than the critics of the rehabilitative ideal could ever have imagined.

I. The Real Face of Therapeutic Jurisprudence

In a drug court in Washington, D.C., the judge roams around the courtroom like a daytime TV talk show host, complete with microphone in hand.' Her drug treatment methods include showing movies to the predominantly African-American defendants, including a movie called White Man's Birth.3 She often begins her drug court sessions by talking to the "clients"4 about the movies, and then focusing the discussion on topics like "racism, justice, and equality."5 The judge explains her cinemagraphic approach to jurisprudence this way:

Obviously they need to talk about their own problems and what leads to them, but I also think that it's good to have distractions in life. I've found out that if there are periods of your life when you are unhappy, sometimes going out to see an interesting movie or going out with a friend and talking about something else, or going to the gym to work out, these kinds of things can help you through a bad day.6

After the film discussion, the session begins in earnest. Defendants who are not doing well are scolded and sometimes told stories, often apocryphal, about the fates that have befallen other uncooperative defendants or the drug court judge's own friends and family members.7 Some defendants are jailed for short periods of time and/or regressed to stricter treatment regimens, and eventually some are sentenced to prison.8 The audience applauds defendants who are doing well, and the judge hands out mugs and pens to the compliant. The judge regularly gives motivational speeches that are part mantra and part pep rally. Here is a typical example:

Judge: Where is Mr. Stevens? Mr. Stevens is moving right along too. Right?

Stevens: Yep.

Judge: How come? How come it is going so great?

Stevens: I made a choice.

Judge: You made a choice. Why did you do that? Why did you make that choice? What helped you to make up your mind to do it?

Stevens: There had to be a better way than the way I was doing it.

Judge: What was wrong with the way you were living? What didn't you like about it?

Stevens: It was wild.

Judge: It was wild, like too dangerous? Is that what you mean by wild?

Stevens: Dangerous.

Judge: Too dangerous, for you personally, like a bad roller coaster ride. So, what do you think? Is this new life boring?

Stevens: No, not at all.

Judge: Not at all. What do you like about the new life? Stevens: I like it better than the old.

Judge: Even though the old one was wild, the wild was kind of not a good wild. You like this way.

Stevens: I love it.

Judge: You love it. Well, we're glad that you love it. We're very proud of you. In addition to your certificate, you're getting a pen which says, "I made it to level four, almost out the door."9

This is the real face of therapeutic jurisprudence. It is not a caricature. Except for the movie reviews, this Washington, D.C. drug court is typical of the manner in which this particular kind of therapeutic court is operating all over the country. Defendants are "clients"; judges are a bizarre amalgam of untrained psychiatrists, parental figures, storytellers, and confessors; sentencing decisions are made off-the-record by a therapeutic team10 or by "community leaders";11 and court proceedings are unabashed theater.12 Successful defendants-that is, defendants who demonstrate that they can navigate the re-education process and speak the therapeutic language13—are "graduated" from the system in festive ceremonies that typically include graduation cake, balloons, the distribution of mementos like pens, mugs, or T-shirts, parting speeches by the graduates and the judge, and often the piece de resistance—a big hug from the judge.14

Drug courts are the most visible, but by no means the only, judicial expression of the therapeutic jurisprudence movement. The idea that judges should be in the business of treating the psyches of the people who appear before them is taking hold not only in drug courts but in a host of other criminal and even civil settings. Some therapeutic jurists see bad parenting, domestic violence, petty theft, and prostitution as curable diseases, akin to drug addiction, and argue that divorcing parents, wife-beaters, thieves, and prostitutes should therefore be handled in specialized treatment-based courts.15 The objects of the treatment efforts include not only the litigants in civil cases, and the criminals and victims in criminal cases, but also the "community" that is "injured" by the miscreant. Petty criminals in many so-called "community-based courts" are in effect sentenced by panels of community members, typically to perform various community services as deemed necessary by the panels, in order to "heal" the damage done to the "community.”16

It is curious that the existing scope of the therapeutic jurisprudence movement, with the exception of drug offenses, is limited to relatively minor petty and misdemeanor criminal offenses.17 We might ask ourselves why the movement ignores the entire spectrum of violent felonies, so many of which have an apparent psychiatric component. We don't have specialized child molester courts in which "clients" are hugged and pampered and cajoled into right-thinking. Why not? My suspicion, as discussed in more detail below,18 is that what much of therapeutic jurisprudence is really about, at least in the criminal arena, is a de facto decriminalization of certain minor offenses which the mavens of the movement do not think should be punished, but which our Puritan ethos commands cannot be ignored. Supporters of the movement recognize that as a political matter they cannot go too far blurring the distinction between acts and excuses.19

True to their New Age pedigree, therapeutic courts are remarkably anti-intellectual and often proudly so. For example, the drug court variant is grounded on a wholly uncritical acceptance of the disease model of addiction, a model that is extremely controversial in the medical, psychiatric, and biological communities.20 All of the therapeutic jurisprudence variants presume that the underlying problem in virtually all kinds of cases—drug abuse, domestic violence, delinquency, dependency, divorce, petty crimes—is low self esteem, despite the fact that many psychological studies have shown that violent criminals tend to have high self esteem.21

The question asked in these new therapeutic courts is not whether the state has proved that a crime has been committed, or whether the social contract has otherwise been breached in a fashion that requires state intervention, but rather how the state can heal the psyches of criminals, victims, families, dysfunctional civil litigants, and the community. The goal is state-sponsored treatment, not adjudication, and the adjudicative process is often seen as an unnecessary and disruptive impediment to treatment.22 Because the very object is treatment, rehabilitated criminals deserve no punishment beyond what is necessary to restore them, their victims, and the community to their prior state.23

The therapeutic jurisprudence movement is not only anti-intellectual, it is wholly ineffective. The treatment is a strange combination of Freud, Alcoholics Anonymous, and Amway, whose apparent object is not really to change behaviors so much as to change feelings.24 Drug courts are a perfect example. The success of drug-court treatment programs is measured more by a defendant's professed attitude adjustment than by the sort of concrete measures one might expect of such programs, such as whether the defendant stops using drugs. As long as defendants are compliant with treatment ("buying into the program," as addiction counselors say), they are moved from treatment phase to treatment phase, often irrespective of whether the treatment is actually working. As James Nolan puts it, drug court success "is evaluated in large mea- sure by whether or not clients adopt a particular perspective.25

The particular perspective required is the disease model of addiction. Compliance is almost always measured by a defendant's willingness to admit that his or her drug use is a disease. Any resistance to the disease model is reported as "denial," a crime apparently much worse than continued drug use.26

The therapeutic jurisprudence literature is almost completely devoid of any empirical discussion of whether litigants, defendants, and victims, let alone "communities," are actually being helped by all this perspective-changing treatment, and understandably so. The imprecise words common to the therapeutic language—words like "healed," "restored," and "cured"—are simply incapable of being subjected to rigorous testing.

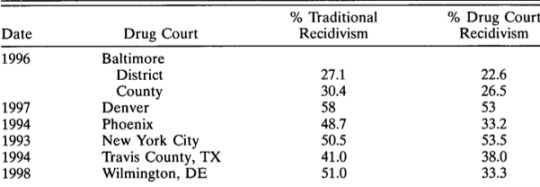

When investigators have looked at less imprecise measures of success-like recidivism rates-the therapeutic promise has proved wholly ineffective.27 For example, the very first effectiveness study performed on the very first modern drug court—in Dade County, Florida—showed that drug defendants treated in the drug court and drug defendants processed in the traditional courts suffered statistically identical rearrest rates.28 Virtually every serious study of drug court effectiveness has reached similarly sobering results,29 leading the General Accounting Office to declare in 1997 that there is simply no firm evidence that drug courts are effective in reducing either recidivism or relapse.30

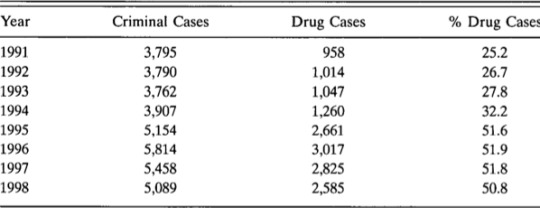

Drug courts not only do not reduce recidivism or relapse, they have the unintended consequence of dramatically increasing the number of drug defendants sent to prison. The reason is massive net-widening, that is, the phenomenon whereby new programs targeted for a limited population end up serving much wider populations and thereby losing their effectiveness. In Denver, Colorado, for example, the number of drug cases nearly tripled two years after the implementation of its drug court.31 That fact, coupled with typically dismal recidivism rates, led to the entirely predictable result that Denver judges sent more than twice the number of drug defendants to prison in 1997, two years after the implementation of the drug court, than they did in 1993, the last year before the implementation of the drug court.32

If therapeutic jurisprudence were just a trendy idea that did not work, we could let it die a natural death. But it is not just trendy and ineffective, it is profoundly dangerous. Its very axioms depend on the rejection of fundamental constitutional principles that have protected us for 200 years. Those constitutional principles, based on our founders' profound mistrust of government, and including the commands that judges must be fiercely independent, and that the three branches of government remain scrupulously separate, are being jettisoned for what we are led to believe is an entirely new approach to punishment. In fact, this new approach-state mandated treatment-turns out to be a strangely out-of-touch return to rehabilitative ideals that gained popularity in the 1930s, but were abandoned in the 1970s because they not only did not work but, in the bargain, armed the state with therapeutic powers inimical to a free society.

There are four main reasons why the new therapeutic judges are most dangerous: 1) they are amateur therapists but have the powers of real judges; 2) they act in concert with each other, their communities, prosecutors, defense lawyers, and the self-interested therapeutic cottage industry, contrary to the fundamental principle of judicial independence; 3) they impinge on the executive branch's prosecutorial and correctional functions; and 4) they impinge on the legislative function by making drug policy.

Before I address these four dangers, let me briefly review the history of punishment and the scant theoretical underpinnings of the therapeutic jurisprudence movement in the context of this history.

II. A Brief History of Punishment

The idea of punishment as moral retribution may have its roots in what some anthropologists have called "defilement," the process by which primitive societies interpreted and explained human suffering as punishment by the gods.33 Such an explanation for otherwise inexplicable suffering can be deeply comforting. It means that our suffering is not meaningless and, more practically, that if we abide by the laws of the gods we will be protected from their wrath.34

As humans began to imitate the laws of gods with the laws of men, we also imitated defilement. Punishment became one of the methods by which we not only enforced our common codes of conduct but also comforted one another with the idea that no one would have to endure man-inflicted suffering so long as the codes of conduct were honored. Indeed, in its most profound sense, the rule of law necessarily requires the tyranny of gods over man, or of the many over the few, and that tyranny in turn requires some form of theocratic or group disapproval when norms are violated.

Interestingly, imprisonment as a form of punishment is a relatively recent invention, in contrast to custodial detention pending trial. In the ancient world, most crimes were punished either by banishment, various forms of corporal punishment such as beating or mutilation, or, most often, death.36 Imprisonment was reserved as punishment only for disobedient slaves, whose execution was uneconomic; political criminals, whose execution risked martyrdom; and petty criminals, whose execution was unwarranted.37 Even as late as the 1780s, in a society as fully touched by the Enlightenment as England, death was the sanction for virtually every crime, including crimes that we would today deem misdemeanors.38

There were many precursors to the modern prison: jails for pretrial detention and short sentences; workhouses for debtors; almshouses for the poor; reformatories for minors; convict ships for banishment; and the gallows for most other crimes.39

In fact, the prison-that is, a jail for serving long sentences after conviction—is a uniquely American invention. Prisons were first used by Pennsylvania Quakers in the late 1700s, primarily as a humane alternative to corporal punishment and execution.40 The first prison was Philadelphia's Walnut Street Jail, which the Quakers opened in 1790 as a "penitentiary" for criminals convicted in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania.41 The Quaker notion of a penitentiary was the product of the fortuitous confluence of the Quakers' theological beliefs and their knowledge of Cesare Beccaria's retributionist monograph On Crimes and Punishment.42 The Quakers hoped that long periods of isolation, which provided an opportunity for reflection and solitary Bible study, would ultimately lead to repentance.43 New York adopted this system in 1796, and prisons soon flourished across America and Europe.44

The modern debate about punishment revolves around the primacy of four components: retribution, deterrence, incapacitation, and rehabilitation.45 In the late 1700s-precisely at the time when the Quakers were experimenting with prisons and, more importantly, when our founders were debating our form of government—the German philosopher Immanuel Kant constructed a philosophy of retribution, giving a rational foundation to what had been the retributional basis of all punishment since the dawn of civilization.46 He argued that the preeminent goal of criminal law must be retribution, and that punishment should be an end in itself.47 Kant's view was that to punish the criminal defendant as a means to any other utilitarian goal-deterrence or rehabilitation, for example—was to de-humanize him by reducing him to an object.48 Moreover, Kant viewed punishment as a purely retributive reaction to the crime itself, therefore, the punishment had to be proportionate to the crime.49

Georg Hegel concurred with Kant's retributionist ideal, adding the notion that punishment annulled the crime.50 In Hegel's construct, crime is the negation of moral law, and punishment is necessary to negate that negation to restore the moral right.51 Hegel continued the Kantian view that criminals themselves are moral beings, entitled to have their crimes negated by proportionate punishment. As Hegel stated:

[P]unishment is regarded as containing the criminal's right and hence by being punished he is honoured as a rational being. He does not receive this due of honour unless the concept and measure of his punishment are derived from his own act. Still less does he receive it if he is treated either as a harmful animal who has to be made harmless, or with a view to deterring and reforming him.52

Cesare Beccaria is generally credited with the first systematic exposition of proportionality.53 His version, much heralded in Western Europe and the American colonies, took a decidedly political view. Beccaria believed that requiring criminal sentences to be proportionate to the crime was an important limitation on the powers of government.54

Thus, retribution not only survived the Enlightenment, it achieved an important philosophical structure, both in its own right and as the basis for proportionality. It continued to flourish in both Europe and America and was consistent with the spread of the Quaker penitentiaries. People were sentenced to penitentiaries to be punished; there was nothing "rehabilitative" about them, except the repentance that was expected to come from enduring the punishment.

The retributionist paradigm lasted thousands of years and did not come under serious philosophical attack until the early 1800s, when a group of English utilitarians led by Jeremy Bentham began to challenge it.55 For the utilitarians, the only purpose of punishment was to prevent crime, that is, to be a deterrent.56 Bentham, and in America, Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., saw the prospective criminal as a rational bad man, who weighed the benefits of his crime against the risks of detection and the costs of punishment.57 The purpose of punishment under the deterrence model was simply to make the costs of crime so high that they outweighed the benefits.58

The utilitarians believed that morality has nothing to with punishment. Bentham argued that if he could be assured that a particular criminal would never commit another crime, any punishment of him would be unjust.59 Richard Posner has argued that aside from the problem of judgment-proof criminals, all criminal sanctions could be replaced with a system of fines.60

Naturally, if punishment is viewed as a utilitarian tool to deter future illegal behavior of potential criminals, then it can also be used, though less efficiently, to shape the behavior of the particular defendant being punished. Not only would punishment deter him from engaging in future crimes, but it could also change him. The early beginnings of what became known as the "rehabilitative ideal" thus started, on their face, as a rather simple extension of the deterrence model.

But it was hardly a simple extension. It represented a profound change in the way human behavior was viewed. Criminals were no longer ordinary people, cursed like all of us with original sin, whose own humanity demanded that their crimes against moral consensus be purged with proportionate punishment.61 Rather, they were morally diseased, quite different from us, and they needed to be cured.

By the end of World War I, this rehabilitative perspective was becoming dominant in American penology, and it remained dominant until after World War II. It is probably no coincidence that the rise and fall of the rehabilitative ideal coincided roughly with the rise and fall of the welfare state.62 Among the state's increasing New Deal responsibilities toward its citizens was the responsibility to cure all the social ills that were believed to lead to crime, and to treat criminals whose as-yet unreformed social circumstances led them to crime. There was a distinct moral fervor in the early rehabilitationists, as there is in its current devotees, similar to the tenor of the temperance movement: There is a right way and a wrong way to live, and lost souls who choose the path of crime, whether as a result of social circumstance or not, must be shown the right way.

The attacks on the rehabilitative ideal came primarily from the political left, beginning with the jewel of the rehabilitative ideal—the American juvenile court system. With its progressive origins in Chicago in 1899, the juvenile court movement was based on the belief that young offenders were not only ripe for rehabilitation, and needed a more individualized and sensitive justice system in order to maximize rehabilitative efforts, but also that, unlike adult criminals, they suffered from the curable sociological disease of "delinquency.”63 The function of juvenile courts was not to punish or to deter, but to cure delinquency. The juvenile court movement took the nation by storm, not at all unlike today's drug court movement.64 By 1920—just twenty years after their invention—juvenile courts were in place in all but three states.

But the sensitive paternalism of the juvenile court movement had an ugly statist face. Commentators began to write about a system in which gentle persuasion was giving way to unchecked judicial powers, and where an abject lack of basic due process "helped to create a system that subjected more and more juveniles to arbitrary and degrading punishments.66 Even the Supreme Court entered the fray, ruling in 1967 that juvenile defendants are entitled to the protections of the Sixth Amendment's guaranty of counsel.67

Critics of both the juvenile and adult rehabilitative ideal also began to express concerns about a governmental regime in which defendants are simultaneously treated and punished. In 1971, the American Friends Service Committee published a scathing attack on rehabilitative penology, and included in their criticisms a fundamental objection to coerced treatment: "When we punish the person and simultaneously try to treat him, we hurt the individual more profoundly and more permanently than if we merely imprison him for a specific length of time."68 The Quakers' recantation of the rehabilitative ideal was particularly influential, given their seminal role in the invention of the American penitentiary.

By 1970, forty years after its ascension, the rehabilitative ideal was in theoretical and empirical shambles.69 Uncoupled to any concept of proportionality, its primary theoretical failure was that it gave the state unchecked powers to "cure" that were unrelated to any notions of criminal responsibility and fundamental justice. If it takes ten years of prison, or any other form of state-imposed therapy or re-education, to cure Jean Valjean of shoplifting, then ten years is what must be imposed. This threat to individual liberty, acceptable to pro-government progressives of the 1930s, was decidedly unacceptable to a post-World War II, post-Nazi, cold war generation becoming increasingly wary of state power. As Norval Morris put it: "[T]he concept of just desert remains an essential link between crime and punishment. Punishment in excess of what is seen by that society at that time as a deserved punishment is tyranny.”70 He further stated: "We cage criminals for what they have done; it is an injustice to cage them also for what they are in order to change them, to attempt to cure them coercively."71

The real death knell to the rehabilitative ideal, both in general and in its juvenile incarnation, came not from the theoreticians but from the empiricists. Rehabilitation simply did not work. Crime was mysteriously immune to the entire liberal regimen, from anti-poverty programs to prison reform.72 After four decades of experimentation, the studies rather dramatically illustrated that all of our idealistic efforts to rehabilitate had virtually no effect on the propensity of juveniles or adults to commit crime.73

The fiction that imprisonment, even in its most rehabilitation- friendly form, has ever been successful in rehabilitating inmates has come to be called "the noble lie" by some critics.74 David Rothman, who coined the term, argued in 1973 that it was long past time to abandon the noble lie:

The most serious problem is that the concept of rehabilitation simply legitimates too much. The dangerous uses to which it can be put are already apparent in several court opinions, particularly those in which the judiciary has approved of indeterminate sentences . . . . Moreover, it is the rehabilitation concept that provides a backdrop for the unusual problems we are about to confront on the issues of chemotherapy and psychosurgery .... This is not the right time to expand the sanctioning power of rehabilitation.75

With a swiftness rarely seen in complex institutions, the American penal system dropped rehabilitation almost overnight. What had, as late as 1972, been described in the criminal law treatises as the central justification for punishment,76 was by 1986, being described in the past tense.77 This was much more than a theoretical rejection by academics and textbook writers. Correctional officials across America were also abandoning rehabilitation in their day-to-day operations.78

The extraordinarily sudden abandonment of the rehabilitative ideal gave way to a kind of fusion of retribution and incapacitation, dubbed by some as "neo-retributionism.”79 The modest goals of punishment as a just dessert, and prevention as the simple act of taking criminals out of society, replaced rehabilitation as the dominant penal theory.80 These ideas ultimately resulted in the abandonment of indeterminate sentencing schemes and eventually to the controversial Federal Sentencing Guidelines.81

Almost all modern criminologists acknowledge that each of the four traditional justifications for punishment—retribution, deterrence, rehabilitation, and incapacitation—must continue to play some role in the criminal justice system.82 However, integrating them into a coherent and sensible system has not been easy, in no small part because they represent incompatible goals.83 If deterrence and incapacitation were the only considerations, then perhaps all crimes should be punishable by life sentences or death.84 If rehabilitation were the only consideration, then all crime could be considered forms of social disease, treatable in hospital-like settings, never in prisons.

Only retribution connects the crime with the punishment, treats criminals as moral beings rather than diseased subjects in a utilitarian social experiment, and imposes proportionality limitations on the government's right to punish. As a result, despite all their machinations about a synthesis, most modern criminologists have found their way back to retribution as the pole star of punishment.85

In 1979, Francis Allen delivered the Storrs Lecture at Yale Law School on the topic of the demise of the rehabilitative ideal. That lecture was published in 1981, and it has become a kind of obituary for rehabilitation.86 Allen impressively documented both the theoretical and empirical failings of rehabilitation. He concluded his lectures with this prediction:

[A]ttitudes toward [the rehabilitative ideal] are likely to be wary in the closing years of this century. A statement made by Lionel Trilling over a generation ago still possesses acute relevance to the present: "Some paradox of our nature leads us, when once we have made our fellow men the object of our enlightened interest, to go on to make them the objects of our pity, then our wisdom, ultimately our coercion. ... " Given the history through which American society has recently passed, it is hardly possible that the total benevolence of governmental interventions into persons' lives will be unthinkingly assumed .... It is just as well. For modern citizens of the world have learned that the interests of individuals and society are frequently adverse and that the assumption of their identity supplies the predicate for despotism.87

Sadly, Professor Allen's prediction could not have been more wrong. Less than ten years after rehabilitation's obituary, the gurus of rehabilitation were back, this time with a vengeance, fueled by a zeal to treat the psychiatrically less fortunate, and in particular to win the war on drugs. These neo-rehabilitationists are pushing judges into unprecedented extremes that Professor Allen could not have imagined. In the flash of an eye judges have become intrusive, coercive, and unqualified state psychiatrists and behavioral policemen, charged with curing all manner of social and quasi-social diseases, from truancy to domestic violence to drug use. By forgetting the most profound lesson of the twentieth century—that the state can be a dangerous repository of collective evil—therapeutic jurisprudence poses a serious risk to the kind of individualism and libertarianism upon which our republic was founded.

III. The Theory Behind Therapeutic Jurisprudence

Although therapeutic jurisprudence descends directly from the long-rejected rehabilitative ideal, its proponents rarely talk about its theoretical heritage. The movement is almost devoid of anything resembling serious theoretical self-examination. The questions that have plagued philosophers and criminologists for a thousand years, and whose answers have come to define all major schools of criminology, are questions therapeutic jurisprudence devotees seldom ask.88 But the movement does have a short history, if not a terribly satisfying theoretical one.

It owes its beginnings to mental health law, where, by definition, the current and prospective mental states of the participants are the primary inquiry. Its initial insights were neither terribly profound nor particularly original: in a system whose very function is to judge the mental state of its subjects, we should think about the mental health effects of the actions we as judges take. Thus, for example, when we remand a criminal defendant for a competency evaluation, we should think about the effects the remand and evaluation might have on the defendant's competence.

These initial formulations about a therapeutic judicial perspective were limited in several important respects. First, they were focused on empirical questions: what effects are our rulings having on the mental health of the chronically mentally ill, insane or in- competent? Proponents, at least initially, never suggested that we should begin to change our rulings or the way we make them in anticipation of effects before we measure what those effects might actually be.

More importantly, these therapeutic ideas were originally proposed exclusively for application to mental health law, where the state has already crossed that thorny boundary of paternalism and already has its hands uncomfortably inside the heads of the unfortunate participants. Of course, many aspects of mental health law involve the judiciary's positive obligation to ensure treatment of the mental conditions of the people appearing in court as a precondition to moving into its more traditional truth-finding role. By expanding the therapeutic model into nonmental health areas, the therapeutic jurisprudence movement not only intrudes without any basis for intrusion, it profoundly changes the judicial function. Trials are no longer processes to investigate factual guilt and discover truth, they are mere opportunities to treat.

This therapeutic perspective is completely inimical to the judicial function. We should conduct trials guided by the rules of procedure and evidence that have been crafted over centuries to maximize the reliability of the result, not to ensure that the litigants have a meaningful mental health experience. We should impose sentences and assess damages guided by well-settled principles of responsibility, not by fretting about whose feelings will be hurt or how the community can be healed.

The profound and dangerous expansion of the judicial role represented by the therapeutic jurisprudence movement is just a small part of a broad therapeutic trend in all aspects of government and indeed across the entire spectrum of our culture. James Nolan has labeled this trend "the therapeutic ethos."89 Government's new role is to treat, not to enforce norms. Its success is measured by how it makes us feel, not by what it actually does. And because the couch of State needs patients, citizens are no longer individual participants in a free republic, but sets of victims with complicated diseases in dire need of state-sponsored treatment.

In this "postmodern moral order," as Nolan calls it, suffering is no longer viewed as a part of the human condition, but rather as the inevitable consequence of some disease or injury. Almost all of human behavior has become pathologized. We speak of "addictions" to all manner of behaviors that we would have called "choices" just thirty years ago.90 Today, cancer and alcoholism are both "diseases"; heroin use now shares an addictive moral equivalence with things like gambling and eating chocolate. Of course, this externalization of behavior is just a new version of our old friend defilement: once we blamed phantom gods for our suffering;91 now we blame phantom diseases.92

In the particular context of drug courts, James Nolan has called this process of pathologization the "eradication of guilt":

The drug court's eradication of guilt has been a subtle and insidious process. Guilt is not so much challenged as ignored. It is not so much disputed as it is made irrelevant. But it is the making irrelevant of something that has long been regarded as the crux of criminal justice.... The jettisoning of guilt may well represent the most important, albeit rarely reflected upon, consequence of the drug court. If, as Philip Rieff argued, culture is not possible without guilt, one wonders what will become of a criminal justice system bereft of what was once its defining quality.93

Blaming the pathogens has become the raison d'etre for the judicial system, both in criminal and civil cases. An African man who murders his wife blames his anti-divorce culture;94 a fired employee blames "chronic lateness syndrome."95 Of course, the judiciary takes its cases as it finds them, and judges cannot be blamed entirely for acting like psychiatrists when the parties insist on it. But the therapeutic jurisprudence movement requires us to act like psychiatrists even when no litigant is insisting on it, and indeed even when all the litigants object (that is, they are in "denial"). It is this aspect of mandated judicial intrusion that makes therapeutic jurisprudence so dangerous and so utterly unacceptable in our constitutional scheme.

IV. The Most Dangerous Branch

The judicial branch was specifically designed to be the least dangerous of the three branches. Hamilton coined that famous phrase in this classic description of the circumscribed powers of the federal judiciary:

[T]he judiciary, from the nature of its functions, will always be the least dangerous to the political rights of the Constitution; because it will be least in a capacity to annoy or injure them.... The judiciary ...has no influence over either the sword or the purse; no direction either of the strength or wealth of the society; and can take no active resolution whatever. It may truly be said to have neither FORCE NOR WILL, but merely judgment; and must ultimately depend upon the aid of the executive arm even for the efficacy of its judgments.96

Federal judges are not elected, but appointed for life, helping to decrease the chances they will be influenced either by corrupt forces or, often more subtly, the vagaries of popular will.97 The case or controversy requirement helps decrease the chances that judges will make abstract law (that is, policy) in the guise of deciding a case.98 The very architecture of the federal and state systems leaves the judicial branches without the power either to make or enforce laws and further dissipates federal judicial power by imbedding it in a system in which individual states continue to operate in their own spheres of sovereignty.