#and offer a reward for any tips which lead to the discovery of captain and his sword.

Text

Combining "What if Anduin embraced shadow and Shadowreaper became canon in WoW" and "What if Anduin ran away to become a pirate under the name Jerek".

#world of warcraft#anduin wrynn#Give me Pirate Shadowreaper please#or just shadowreaper i really want him to appear in wow#or pirate anduin#Legend tells the story of a lone pirate ship#a cursed vessel with a cursed crew#their captain glows in neon colors#and wields a rather familiar sword#The Boralus Authority seeks information on the whereabouts of said ship#and offer a reward for any tips which lead to the discovery of captain and his sword.#anyway ive always wanted to write a fanfic about anduin abandoning the throne and disappears only for years later#someone finds out he became a pirate named jerek#i wrote lots of notes for the story and i should share them even if i dont write it

49 notes

·

View notes

Text

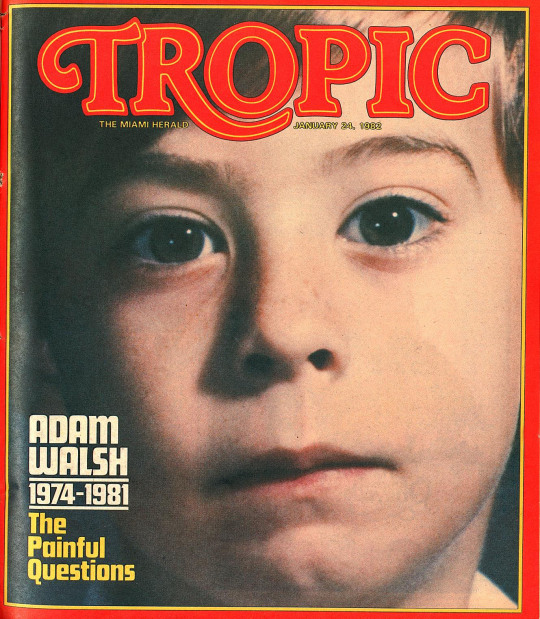

ESSAY: The Walsh Case - Background & Repurcussions

In an era marked by mounting public hysteria over 'stranger-danger' and child predators, the Walsh case is considered by many to be the tipping point, fueled by its own momentum of perceived legal and societal failures to protect children.

From Charley Ross to the Lindbergh Baby, incidents of children abducted by strangers have gripped public attention with a pervasive horror. The idea of childhood as a place of danger rather than security becomes a cruel inversion of social paradigms – particularly when children are snatched from under their parents' noses during humdrum activities. The underlying message – that it could be any child, any time, any place – threatens the very bastion of American society: the family.

Yet few cases have transformed the landscape of American culture as utterly as the kidnapping and murder of Adam Walsh. In an era marked by mounting public hysteria over 'stranger-danger' and child predators, the Walsh case is considered by many to be the tipping point, fueled by its own momentum of perceived legal and societal failures to protect children. Not only would it catalyze the creation of the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children (NCMEC), but it would lead to missing-child safety programs such as Code Adam, as well as the emergence of the Adam Walsh Child Protection and Safety Act. Adam's death would also inspire two highly acclaimed made-for-TV films: Adam (1983) and its sequel Adam: His song Continues (1986). Additionally, the tragedy would see Adam's father, John Walsh, channel his grief into activism, going on to establish the Adam Walsh Child Resource Center, as well as starring as the iconic host of America's Most Wanted.

Section I: Background

To adequately frame the phenomenon in its historical context, it is essential to return to the day of Adam's abduction. On July 27, 1981, Revé Walsh, a housewife in Hollywood, Florida – a seaside city nestled between Fort Lauderdale and Miami – was out running errands, with her six-year-old son Adam in tow. Her husband, a marketing manager for a local hotel company, had earlier called to mention that some brass barrel lamps were on sale at the Sears in the old Hollywood mall. The Walshes often frequented the store, which was a mile and a half from their home. Recalling that fateful afternoon trip with her son, Revé uses phrases such as "I parked as I always did" and "I held Adam's hand, as usual," to underscore its routine nature (Walsh, 1997, p. 112). That particular day, Adam was wearing green running shorts, a striped Izod shirt, yellow flip-flops, and an oversized captain's hat. After his disappearance, the outfit would be described down to the minutest detail in missing-child posters.

Once inside Sears, Revé and Adam took their habitual route through the toys department. At a kiosk, around which other children were flocked, was a video display with Atari 2600 games (Fig. 1.0). Adam asked his mother if he could stay behind and play. By Revé's own admission, this was a common occurrence. "That was our ritual: Going in the north door... And Adam begging me to let him play the video game." The lamp section was not far off; Revé felt comfortable with leaving Adam alone, because he did not have a tendency to wander off. In the Lamps section, Revé discovered that the brass barrel lamps were unavailable, and left her name with a request to have someone call her when they arrived. The task, according to her statement in the police report, took about ten to fifteen minutes (Donahay, 1981). However, when she returned to the toys department, Adam was gone. Her initial assumption was that he had drifted off into the adjacent aisles. However, when she called his name, and received no response, Revé confessed to getting a "strange feeling." As she explains, not only was Adam missing, but so were the gaggle of children at the video game kiosk (Walsh, 1997, p. 93-95).

Combing through the aisles, Revé came upon a boy with a captain's hat similar to the one Adam was wearing. Upon asking him if he had seen a boy with a hat like his, the child pointed outside the mall's west door. However, Revé dismissed this as impossible, since she and Adam never used that particular exit. Instead, Revé tried to enlist store employees' help in finding her son; her first efforts were met with dismissal and minimization: "No one paid any attention to me. They were acting like I didn’t exist. Invisible." This is particularly noteworthy, as it reveals the total absence of any programs or special alerts designed to locate missing children in department stores during the era. As Revé recounts, she was left to search by herself, joined later by her mother-in-law, who was coincidentally also at the mall. But even after Revé managed to flag down an employee to page Adam on the intercom, the announcement – "Adam Walsh, please come to customer service" – was not conducive to her purpose, because the average six-year-old would not know what customer service is (Standiford & Matthews, 2011; Walsh, 1997, p. 97-101).

Over forty-five minutes passed, but there was still no sign of Adam. At this point, the Hollywood Police Department (HPD) were summoned. However, their initial response was tepid at best. Apart from gathering information from Revé, and issuing a Be On the Lookout radio call, the officers seemed at a loss about what to do. As they explained to Revé, they dealt primarily with runaways; they suggested that perhaps Adam had simply wandered out of the store, become confused, and started walking home. As Revé writes, "It seemed like they were trying to get out of doing anything. There was apparently nothing in the book, no page in the manual, for what to do in this emergency. What to do if a little boy went missing"(Walsh, 1997, p. 104).

Ultimately, Revé's husband, John, was called. Together, the Walshes searched the mall, while police officers fanned out around the store in the approximate radius they believed a child in flip-flops might cover. Their search yielded no luck, and eventually, every available police officer was requested to search for Adam, with an alert sent to the Hollywood Citizens' Crime Watch. The scale of the search-party was massive, with the entire detective bureau and twenty-two patrol officers scouring everything from canals to dumpsters. By nightfall, unable to find Adam, the Walshes vacated to the police station opposite to the mall. They left Revé's unlocked car in the parking-lot, piled with blankets, toys, books, and a note visible behind the windshield, saying, "Adam, stay in the car. Mommy and Daddy are looking for you" (Standiford & Matthews, 2011, p. 56)

It was not until much later that Revé would remember being approached by a store security guard: seventeen-year-old Kathy Shaffer. She describes Shaffer as appearing upset because that same afternoon, she had broken up a scuffle between a group of boys – two white and two black – in the Toys section. She had put the black boys out of the north door, and the white boys out of the west door. While uncertain at the time about whether one of the boys was Adam, she would later state during a follow-up interview that she was eighty-five percent certain it was (Walsh, 1997; Mundy, 1996) (See Fig. 1.1). If that were the case, then Adam would have been disoriented, left outside an exit he was unfamiliar with. According to John and Revé, he may have not even have told the security guard that his mother was inside, because "he was a timid child and mindful of authority" (Reauthorization and Improvement..., 2009, p. 225).

Whatever the case, Adam's brief moments alone were enough for a drifter named Ottis Toole to lure him into his car with promises of toys and candy. Once Adam was inside, Toole took off north on i-95, heading toward his home in Jacksonville. During the initial journey, Adam appears to have been compliant; however, as the unfamiliar scenery passed by, he panicked and began to cry. Toole hit him several times to silence him, eventually "wallop[ing] him unconscious." Soon after, Toole pulled over to an empty service road north of the Radeburgh Road overpass, where he strangled Adam to death with a seatbelt. After dragging his body into a clearing between the brush and trees, Toole then decapitated him with a bayonet. He claims to have thrown the boy's head in a canal in Fort Lauderdale, and disposed of the body by incinerating it in an old refrigerator in Jacksonville (Chermak & Bailey, 2016, p. 824).

Of course, these details would not emerge until Toole's confession (among a slew of others) two years after Adam's disappearance. In the interim, a large-scale investigation was launched as the police's focus shifted from a lost child to a potential kidnapping. Jack Hoffman, the Hollywood detective leading the case, stated, "This is not the type of child to just walk off. But we don’t have any clues whatsoever what the motive would be." Flyers bearing Adam's picture – a quintessentially all-American boy with a red baseball cap and a cheerful gap-toothed grin – were distributed throughout the city (Fig. 1.2). The Walshes offered up a $5000 reward for the safe return of their son. As the days wore on, the amount was bumped up to $100000. However, despite countless tips and false leads, no one came forward with solid information about Adam's whereabouts (Walsh, 1997, p. 221).

Then, on August 10, 1981, two weeks after Adam's disappearance, a grisly discovery was made. While fishing on the banks of a drainage canal alongside the Florida Turnpike, two ranch hands glimpsed what appeared to be a doll's head floating in the water. However, when they paddled closer in a rowboat, they saw that it was human. The Florida Highway Patrol was summoned, as were the police and fire rescue from the neighboring Indian River County and St. Lucie County. Together, they attempted to search for Adam's remains, but were unsuccessful (Fig. 1.3 – 1.4). With the aid of Adam's dental records, the HPD were able to positively identify the recovered head as Adam's. The coroner, Dr. Wright, ruled the cause of the boy's death as asphyxiation. Judging by the liquefaction of the brain, Adam had been dead for approximately sixteen days after his disappearance. A machete or cleaver had been used for the decapitation itself; Wright stated it unlikely that Adam was alive when it occurred. To this day, the rest of Adam's body remains unrecovered (Standiford & Matthews, 2011).

Section II: The Victims

The primary victim of this tragedy is Adam Walsh. Described by his parents as an "introverted, sheltered, but very bright little boy," six-year-old Adam undeniably fits the criteria of the ideal victim/positive type, stirring public empathy as a "faultless innocent who has had crime visited upon them by a wicked perpetrator" (Hartman, 1981; Spencer & Walklate, 2017, p. 115). Media, volunteers and authorities alike flocked to his search; the news of his murder had manifold ripple effects, leaving not only his family but an entire nation shaken in its wake. The ramifications it would hold for both the social climate and the legal system will be touched upon later in this paper.

As mentioned, Adam was abducted from the Sears mall by Ottis Toole, chiefly because he was alone. In a number of statements made to the police, Toole would recount the different methods by which he murdered Adam – only to recant each confession. Sometimes, he stated that he had acted alone; other times he claimed he had an accomplice (his partner, Henry Lee Lucas.) His motive for kidnapping Adam would also change. Sometimes he claimed he had snatched the boy because he wanted to adopt him as a son; other times his reasoning was more predatory (Hickman & Hoffman, 1983). This would prove immensely frustrating for the investigation team, given that there was little physical evidence (largely due to mishandling on the part of the police and the crime lab) to otherwise connect him with the crime. It also meant that Toole, while incarcerated for other murders, was not specifically convicted for Adam's – causing no small amount of distress for Adam's parents, the secondary victims.

Directing our attention to John and Revé Walsh, it is essential to understand the mind-frame of these parents, who endured two weeks trapped in a limbo between hope and despair. The apprehension of Adam's would-be killer should have afforded a sense of grim closure, if nothing else. However, the HPD's mishandling of the case prolonged their ordeal over a span of decades. The department, overwhelmed by the sheer scale of Adam's case, and ill-equipped to conduct such a complex investigation, ended up withholding or overlooking key pieces of information. Chief among these was their neglecting to mention the green shorts and yellow sandals (matching Adam's outfit) that were found buried in Toole's yard, losing the vehicle which purportedly contained samples of Adam's DNA, and their failure to send the state attorney a graphic extortion letter Toole had written to John Walsh, confessing to Adam's murder (Standiford & Matthews, 2011). The Walshes were understandably appalled by the negligence; their lawyer went so far as to declare, "...[the] Hollywood police are the biggest bunch of bungling idiots since the Keystone Kops" (Walsh, 1997, p. 481).

Further contributing to the Walshes distress was the unusual nature of Adam's case itself. Studies conducted by the National Incidence Studies of Missing, Abducted, Runaway, and Thrown-away Children (NISMART-2) place Adam's disappearance in the category of "nonfamily abduction," specifically stereotypical kidnapping. These are the rarest and most dangerous types, estimated at 115 per year, with the victims at a much higher risk of death than other abducted children (O'Brien & French, 2008; Sedlak, et al., 2002) (Fig. 1.5). The rarity of the crime, coupled with systemic failures – such as the fragmented nature of statewide databases for missing children at the time, and the inadequacy or outright absence of programs to provide comprehensive services for crime victims – would leave the Walshes feeling overwhelmed and isolated as they attempted to navigate through an alien world of criminal procedure.

Given the multiple layers of trauma, the Walshes would experience a vast spectrum of emotions: sadness, anger, despair, frustration, confusion, guilt and fear. They had thrown themselves into Adam's search as a means of keeping a semblance of control: "We were trying to fill every possible vacuum, with work, with effort, and with strategic planning." Understandably, the news of Adam's death struck a devastating chord of helplessness as well as personal loss. In his autobiography, John Walsh recounts how utterly the tragedy warped his and Revé's fundamental schemas of selfhood, and of the world itself. "...the scariest thing about Adam being murdered was that the world kept going on as it had been... It was as if nothing had changed." Besieged by intrusive thoughts of Adam's last moments, the couple had difficulty sleeping, eating or engaging with the outside world. "We were like two helpless children. We were reduced to being children." Revé was particularly affected because two weeks before Adam's disappearance, she had broken off an extramarital affair with a family friend, Jimmy Campbell – a fact that needlessly diverted the focus of the police investigation, served up salacious fodder to the press, and strained her relationship with her husband for a time. Similarly, John describes moments of suicidal ideation coupled with reckless behavior – including a close call with a hang-glider that crashed into the water. "...Throughout my life, I had survived ... so many brushes with death. But now, this time ... there didn’t seem to be any point" (Walsh, 1997, p. 147-615)

In addition to grappling with Adam's loss, the Walshes were thrust into the limelight and affixed with the label of mourning parents – an inherently limiting designation that placed any reaction diverging from the 'normal' paradigm under attack. John notes that it is fortunate he and Revé were white, middle-class and telegenic; otherwise their case would never have garnered national attention. That said, the scope of the attention was oftentimes intrusive. Not only did the media infringe on the family's privacy, but it opened up John and Revé to judgement during an especially sensitive time. Revé, for instance, was criticized for appearing too aloof during press conferences – "[not] acting the way they thought a grieving mother should" (Walsh, 1997, p. 611). Consistent with a tendency toward 'mother-blaming,' her supposed carelessness in leaving Adam unsupervised at the mall was also alighted upon (Ladd-Taylor & Umansky, 1998).

Understandably, the Walshes faith in institutions – the HPD, which bungled Adam's investigation from start to finish; the FBI, which refused to investigate Adam's disappearance in favor of searching for a missing $500,000 horse; the media, which exploited their grief for profit – was fundamentally shaken (Walsh, 1997, p. 252). The failure of these agencies would constitute what Martin Symonds refers to as a "second injury," wherein victims are further betrayed as they do not receive the support they are entitled (2010). Lastly, in terms of spirituality, it is equally likely that the Walshes – who identified as Catholic – would find religion either a source of comfort, or begin to question the core tenets of their faith.

In their work, Beyond the "victim": Secondary traumatic stress, Figley and Kleber note that secondary victims, despite experiencing the event indirectly, are oftentimes equally traumatized. Described as a "secondary traumatic stressor," or vicarious victimization, this holds a number of psychological consequences, from addictive behaviors to feelings alienation in interpersonal relationships (1995). Research delineates five particular areas which undergo cognitive disintegration: safety, trust, control, esteem, intimacy (McCann, Sakheim & Abrahamson, 1988). Similarly, multiple psychological publications emphasize the loss of a child as one of the most distressing events an adult can experience, catalyzing changes in their daily interactions and redelineations of social roles (Holmes & Rahe, 1967; Klass, 1988; Conrad, 1998). Further exacerbating the Walshes ordeal would be, not the extent of social support, but its nature and effectiveness. A study conducted by Sarah K. Spilman describes social support as a buffer that can aid in successful coping when parents lose a child. However, a protraction of the stressful situation often sees a concurrent diminishing of support, usually due to impediments in maintaining social relationships. Outsiders may lack the knowledge and awareness to respond appropriately to the secondary victims' needs. Worse, the social stigma that accompanies victimization, whether primary of secondary, often contributes to an inherent discomfort among nonvictims. For reasons ranging from the "just world" hypothesis to preconceptions of safety and goodness, victims may be perceived as anomalies because they challenge others' inherent beliefs (2004). As John Walsh notes, "People couldn't stand us ... Revé and I were in a place that they didn’t know anything about, and they weren’t sure how even to be around us" (1997, p. 243).

Understandably, as the parents of a murdered child, and as multifaceted individuals in their own right, the Walshes needs are complex. In addition to requiring a continuum of consistent support through the different stages of their journey, they might benefit from counseling, as well as from a functional social support network of parents facing similar crises. A focus, not on conventional psychodrama but sociatry, might also aid their healing process. Defined by Moreno as the "healing of normal society...of inter-related individuals and of inter-related groups," this sociometric focus on broader issues within the communal fabric, with an emphasis not on linear/sequential healing, but on processing trauma as a cyclical entity with its own ebbs and flows, may be useful in allowing them to find a place within a chaotic universe, especially after such a fundamentally damaging shift in their world-view (Bloom, 2011, p. 113).

Additionally, following Toole's apprehension, the Walshes would seek access to the criminal justice system, the better to feel like active participants rather than passive bystanders in the construction of their son's case. Victim assistance professionals could bolster them in various ways: by coordinating with the family throughout the justice process, by providing them with both information and support during court proceedings, by serving as mediators between them and the press, and by encouraging them to offer input during and after the case's resolution – whether in the form of impact statements, or, on a legislative level, during the review or revision of statutes (Walklate, 2017).

The necessity of restoring both safety and agency in the Walshes day-to-day lives would also be paramount. As mentioned, the conception of trauma as absolutely random, rather than guided by latent principle of justice, can be terrifying for one's core belief-systems. Many victims, following the aftermath of a crime, find a measure of comfort in the idea – especially if denied the reality – of personal choice in how they choose to process negative outcomes. This freedom to rebuild their inner world on their own terms, at their pace, undoubtedly serves as a springboard for reshaping their roles in the external world. Whether this is via grasping a voice through advocacy/policy-making, forming local coalitions with other victims' rights groups on a local or national scale, augmenting sources of funding for other crime victims etc, such recourses are a source of empowerment, as they allow individuals to confront their experiences and reestablish a vestige of positive purpose in their lives (Laxminarayan, 2015). On a more tangible level, the local law enforcement could adopt schemes of collaborative problem-solving within the community itself, to restore essential components of safety to the Walshes' lives. A study conducted by Eileen E. Rinear revealed that of a sample of 200 parents whose children were lost to homicide, a quarter reported concerns for the safety of themselves and their surviving children (1988). Given how extensively Adam's case was mishandled by the HPD, it is imperative to cross-train law enforcement personnel on cases of missing children. Additionally, the development of an agency-wide victim assistance program may foster greater cohesion between the HPD and those it serves. For the Walshes, the aforementioned steps might be beneficial in negating, if not erasing, the negative sequelae arising from Adam's murder – particularly an inherent feeling of insecurity, since the kidnapping occurred in their hometown, under their parental aegis.

Section III - Advocates and Exposers

From the beginning, one of the most salient aspects of Adam's case is the incredible momentum behind it. Described as one of the largest missing-child searches in Florida, Adam's disappearance would see Crime Watch volunteers, the media, law enforcement, psychics, politicians, non-profit organizations, and ordinary people from different walks of life rallying to his cause. More noteworthy is the fact that, rather than enlisting support from missing-child advocacy groups, Adam's case would instead be the source-material from which prominent organizations for abducted children would spring forth. As John Walsh recalls, he was approached during the early days of Adam's disappearance by state-based groups such as Child Find – a New York organization for missing children run by Kristin Cole Brown, and by Julie Patz, whose son Etan's disappearance led to May 25th as being designated National Missing Children's Day – largely to enlist his support in championing for missing children on a national level (Walsh, 1997). Independently, these groups and individuals could wield little clout; however, John was one of the few visible white males fighting for change in this arena, with a drive and dynamism that appealed to media groups. With him as the vocal figurehead of a growing missing-children movement, it would not be long before their cause garnered legislative attention.

One of the first people to contact the Walshes in the interest of juridical change was Ivana DiNova, the president of the now-defunct Dee Schofield Awareness Program. Based in Brandon, Florida, the organization's primary goal was to aid families of missing children, in memory of Ivana's niece Delilah, who went missing in 1976 (Good, 2004). DiNova was campaigning for the passage of a bill known as the Missing Children Act, which would require that a centralized database on missing children be maintained by the FBI. Assisting in her efforts were Florida's Republican senators, Paula Hawkins and Lawton Chiles, both of whom had cosponsored the bill. Hawkins was particularly enthusiastic in enlisting the Walshes' support (Standiford & Matthews, 2011). Critics of the bill had argued that it would invade privacy and violate personal freedoms. However, with someone as well-known as John Walsh lobbying on their behalf ("their poster-person," as Walsh describes himself), the bill's proponents hoped to sway the general public alongside official policy (1997, p. 586). While it would be cynical to dismiss these overtures as strategic, it is also essential to keep in mind that such movements on the social and legislative front were emblematic of a greater paradigmatic shift in the 1980s from rehabilitation to retribution, in the wake of a violent crime surge. Unfortunately, hand-in-hand with this tough-on-crime stance was an appeal to moral authority, frequently with emotive rhetoric and the conflation of fact and fiction, as part of the claims-making process. In their work, Critical Readings: Moral Panics and the Media, Critcher notes that "The example of the missing-children problem suggests that rhetoric plays a central role in claims-making about social problems. Atrocity tales typified the missing children problem..." (2011, p. 209). Indeed, testifying before the Senate committee, John Walsh cut a tragically dignified figure. Lamenting the fragmented nature of law enforcement agencies across different jurisdictions, he would call for a more unified system, while painting a grim picture of a nation beset by child abductions. "This country is littered with mutilated, decapitated, raped and strangled children" (Jones, 2015).

The media would alight upon the dire pronouncement. Despite statistical evidence to the contrary, missing children came to be portrayed as a national epidemic, lured from their homes by psychopathic strangers to be despoiled and murdered. Walsh would go as far as to warn that 50000 American children were snatched by strangers per year – despite data from the FBI collected in 1984, which put the number firmly at 67. While there were, certainly, a large number of reports concerning missing children, a majority were runaways, with the remainder taken by non-custodial parents (Silverman, 2009; Waxman, 2016). However, based in part on what Turvey and Patherick refer to as the availability heuristic, media groups would evoke images of a society fallen to chaos, with child-abductions by strangers – once a rarity – burgeoning into a terrifying daily phenomenon. Articles on missing children would be published in the Newsweek, Times, Psychology Today, and even Penthouse. Semi-fictional works such as the television miniseries Adam would have the twofold effect of immortalizing Adam's legacy while sparking fears of serial killers prowling for innocent children in playgrounds and neighborhoods. Schools would implement educational programs for youngsters to recognize signs of "stranger-danger," and hyperintensive "helicoptor parenting" would transform the geography of childhood from one of carefree idealism to unceasing vigilance (Best, 1993; Wojcik, 2016). Paula S. Fass notes that the omnipresent threat of child-abduction became the Agony of the 80s, remarking, "...the poster children, the billboard children, and the Advo card children of all colors, both genders, and a variety of ages became everpresent, a psychic scar in American culture" (1999, p. 237; 2007).

This is not to say, of course, that the Walshes concerns were entirely ungrounded. There was, indeed, a linkage gap between law enforcement agencies across different states – not to mention a dearth of nationwide databases for missing children. The Walshes were determined to rectify this problem, the better to raise awareness and help families in similar predicaments. It was in this spirit that they founded the Adam Walsh Outreach Center for Missing Children in 1981. A nonprofit sustained on donations, the organization had three initial goals: Campaigning to assist Paula Hawkins in passing the Missing Children Act; aiding police agencies in the recovery of missing children; and offering a $100,000 reward for information on Adam's potential killer. Over time, however, the organization would receive support from numerous entities – from the American Bar Association’s Center on Children and the Law, which continues to work for advancements in children's' rights through justice, knowledge, practice and public policy, and Child Advocacy, Inc., a Florida-centered nonprofit specializing in education and training on children’s issues. These organizations, and a myriad of others, would merge with the Adam Walsh Outreach Center to become national movement (Walsh, 1997).

Finally, in 1982, Congress would enact the Missing Children Act, allowing the entry of missing child information into the FBI's National Crime Information Center database. By 1984, former President Ronald Reagan would officially establish the National Center for Missing & Exploited Children, and the Adam Walsh Outreach Center would integrate with it to become the first national clearinghouse for information on missing and exploited children. To this day, the NCMEC remains an active force in matters of child safety and prevention, as well as in victim and family support (Fig. 1.6). They have a 24-hour toll-free hotline (800-THE-LOST) as well as a website, (www.missingkids.com) that functions as a de facto database for abducted/victimized children. The organization's goals are to disseminate information on children reported missing, to assist physically and sexually abused children, offer case analysis, support and training to law enforcement, and to distribute vital safety information to families. They have a sister network, the International Center for Missing & Exploited Children, that operates in twenty-two countries in conjunction with Interpol. The organization has also created a CyberTipline to make it easier for online computer users to report information regarding child enticement, child pornography, sex tourism, and molestation (NCMEC, 2017). By 2001, the tipline received more than 38,000 reports of child exploitation to be forwarded to designated law enforcement agencies. In 2017, the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention awarded the organization up to $28.3 million in funding, as support for it continued efforts to promote child safety (Missing and Exploited Children: Background and Policies, 2017).

Section IV: The Law

Prior to Adam's abduction, the abysmal absence of any coherency or cohesion in statewide databases has been noted. Indeed, throughout his crime-fighting career, John Walsh would decry the lack of centralized databases, much less any federal mandates to trace missing children, as a national failure. This became his chief impetus for lobbying for the passage of the Missing Children Act. Testifying before the Senate in 1981, Walsh would remark that the very creation of the FBI was "to assist in the war on kidnapping," – a reference to the earliest federal kidnapping act of 1932, the Lindbergh Law (Walsh, 1997, p. 253). Created after the horrific and highly mediated abduction and murder of Charles Lindbergh's son, the law dictated it a federal offense to transport victims across state lines or utilize mail services for ransom notes. While intended to give the FBI greater authority in pursuing kidnapping cases, Les Standiford notes that the agency "... maintained a long-standing reluctance to interfere with local police in such matters. It often made for bad politics, for one thing; for another, most kidnapping cases turned out to be the result of messy, interfamilial wrangling" (2011, p. 148).

However, Walsh remained steadfast in his advocacy, enlisting support from the media. While the initial Senate hearing's publicity was eclipsed by the assassination of Egypt's president, Anwar el-Sadat, Walsh, in tandem with Julie Patz and other parents of missing children, made an appearance on the Phil Donahue show. Described by Lisa R. Cohen as highly "substantive," and "topical" during the era, the show provided Walsh with a sweeping platform (2012, p. 71). Over eight million viewers would tune in to hear the tragic stories of Adam and other missing children, and be urged to write to their state representatives for the passage of the Missing Children Act. Walsh would also make the rounds of Washington, attending summits with politicians, child advocates and law enforcement, speaking at length in news conferences and appearing on popular shows such as Good Morning America and NBC's Real People. Prominent public figures such as Dr. Frank Osanka would deliver lectures on "The Other Adams: Facts About Child Abductions in America;" Sociologists such as Michael Agopian, director of the Child Stealing Research Center, would declare that there were "tens of thousands of additional Adams that [were] not so prominently reported by the media" (Best, 1993, p. 29; Gardner 2009; Missing Children's Assistance Act, 1984; Walsh, 1997).

It would take almost a year for the legislation to be signed into law, and another two years for the establishment of the NCMEC – but media pressure would be instrumental in bringing everything to fruition. Florida representative Clay Shaw would go as far as to remark, "I have in my office received literally thousands of names on petitions and letters" – a fact he would attribute to the vast television coverage on the issue (Cohen, 2009, p. 72). Of course, to solely credit the media as spearheading the missing-child movement is simplistic. However, increased news cycles and milk carton campaigns certainly lent higher visibility to what in truth were rare occurrences (See Fig. 1.7). Popular made-for-television films such as Adam and its sequel Adam: His Song Continues would galvanize the public into demanding the enforcement of harsher laws to prevent child victimization. John Walsh would also become increasingly prominent as a bereaved parent-turned-celebrity, serving as an embodiment of the agonies of stranger-abduction while explicitly and implicitly shaping public views of the problem through activism and show-business alike (America's Most Wanted and The Hunt with John Walsh to name a few). As mentioned, a sociological shift toward punitive criminal justice policies and hardline tactics was already burgeoning during the era. However, the abductions of children such as Adam, Etan Patz, and Steven Stayer would fan the flames of moral panic to new heights (Fass, 2007; Negra, 2010). The multifaceted range of media, from local TV broadcasts to highway billboards, would saturate public consciousness and leave parents with a sense that child-abductions were snowballing beyond the control of law enforcement. Psychotherapist Nicholas Kardaras notes how the era marked "a turning point in our society. It was a beginning of a new age of worry for parents, and many of the 'kid freedoms' that people from an earlier generation remember [were] now a thing of the past" (2017, p. 190).

Whatever the case, the Missing Children Act would herald a slew of legislation from the late 1980s all the way to the 2000s, in the interests of protecting children. By 1990, the National Child Search Assistance Act would require local, state and federal law enforcement agencies to enter information concerning missing children into the National Crime Information Center (NCIC) database without a waiting period. Barely four years afterward, the Wetterling Act would be implemented with the purpose of requiring states to maintain a sex offender and crimes against children registry. 1996 would see the enactment of Megan’s Law, which demanded community notification of sex Offenders, and the Lychner Act, which implemented offender registration on the national level. By 2000, the Child Abuse Reform and Enforcement Act (CARE) would be passed to "promote the improvement of information on, and protections against, child sexual abuse." Most recently and pertinently, the Adam Walsh Child Protection and Safety Act was signed into law by then-President George W Bush in 2006. Commemorating Adam's twenty-fifth anniversary, the act boasted a number of stricter provisions, including the increase of mandatory minimum sentences for sex offenders, the upgrade of sex offender registration and tracking, the creation of a Sex Offender Management Assistance program (SOMA), under which the Attorney General may award grants to jurisdictions to alleviate the costs of implementing the Sex Offender Registration and Notification Act (SORNA), and the establishment of an Office of Sex Offender Sentencing, Monitoring, Apprehending, Registering, and Tracking Office (SMART Office). The late 1980s would also see several malls and department stores adopting a special alert known as Code Adam, when customers reported a missing child. First established by Wal-Mart and Sam's Clubs, "Code Adam" would be the precursor to the well-known "Amber Alert," which serves today as means for broadcast-based community notification (Federal Child Protection Law, n.d; Sprague, 2013; SMART Office, n.d.; Wilson, 2009).

The Walshes' home state of Florida, would also see prominent laws enacted following Adams disappearance. By 1997, under the Public Safety Information Act, Florida would became the first state to list sexual predators and offenders on the Internet, allowing the information to be available via a 24-hour hotline. A year afterward, the Jimmy Ryce Act would be passed unanimously by the Florida legislature, calling for inmates with a history of sex offenses to be reviewed by the Department of Corrections to determine their risk level for re-offending. In 2005, the Jessica Lunsford Act would call for the legal classification of sexual acts on a person under the age of 12 as a life felony, with a mandatory minimum sentence of 25 years in prison and a lifetime electronic monitoring. (ICPC State Pages, n.d.; Florida Dept. of Law Enforcement, n.d; Jessica's Law, 2010; Jimmy Ryce Act, 2017.)

By far one of the most polemical aspect of the Walsh Act and its successors has been their infringements on privacy. By resorting to what many opponents perceive as Federal coercion, the laws' broadened criteria for sex offenders burdens not only the states, but resorts to ill-begotten methods of punishment and ostracism that increase rather than decrease recidivism. Yet, when examined holistically, these ever-evolving laws are also reflective of the social anxieties and political agendas marking the era. Beginning with the fateful day of Adam's abduction, they reveal the power of the press, the general public, policymakers – and above all the victims – to transform the landscape of both American culture and official policy alike.

References

Best, J. (1993). Threatened children: rhetoric and concern about child-victims. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Bloom, S. L. (2011). Creating Sanctuary: Toward the Evolution of Sane Societies, Revised Edition. Florence: Taylor and Francis.

Catalog Record: Title IV, Missing Children's Assistance Act hearing before the Subcommittee on Human Resources of the Committee on Education and Labor, House of Representatives, Ninety-eighth Congress, second session, on H.R. 4971 ... hearing held in Chicago, IL, on April 9, 1984. (1984, April 9). Retrieved October 25, 2017, from https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/002765969

Chermak, S. M., & Bailey, F. Y. (2016). Crimes of the centuries: notorious crimes, criminals, and criminal trials in American history. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO.

Cohen, L. R. (2012). After Etan: the missing child case that held America captive. New York: Grand Central Publishing.

Conrad, B. H. (1998). When a child has been murdered: Ways you can help grieving parents. Amityville, NY: Baywood

Critcher, C. (2011). Critical readings: moral panics and the media. Maidenhead: Open University Press.

Donahay, M. (1981). Missing Person - Juvenile (Report No. 0310). Incident Number: HE-81-056073, Hollywood, Florida: HPD.

Fass, P. S. (1999). Kidnapped: child abduction in America. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Fass, P. S. (2007). Children of a new world: society, culture, and globalization. New York: New York University Press.

Federal Child Protection Law - The Adam Walsh Child Protection and Safety Act. (n.d.). Retrieved October 25, 2017, from http://www.stimmel-law.com/en/articles/federal-child-protection-law-adam-walsh-child-protection-and-safety-act

Figley, C. R., Gersons, B. P., & Kleber, R. J. (1995). Beyond trauma: cultural and societal dynamics. New York: Plenum Press.

Florida Department of Law Enforcement, (n.d.). FDLE SERVICES FOR LAW ENFORCEMENT. Retrieved October 25, 2017, from http://offender.fdle.state.fl.us/offender/About.jsp

Gardner, D. (2009). The science of fear: how the culture of fear manipulates your brain. New York, NY: Plume.

Good, M. E. (2004). Dorothy Delilah Scofield. Retrieved October 25, 2017, from http://www.charleyproject.org/cases/s/scofield_dorothy.html

Hartman, D. (Host). (1981). ABC Good Morning America Sunday. Retrieved September 12, 2017 from Electric Library database.

Hickman, R., & Hoffman, J. (1983). Interview of Otis Elwood Toole (Report No. 81-56073). Hollywood, Florida: HPD.

Holmes, T., & Rahe, R. (1967). Holmes-Rahe social readjustment rating scale. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 11, 213–218.

ICPC State Pages. (n.d.). Retrieved October 25, 2017, from http://icpcstatepages.org/florida/criminalbackground/

Jessica’s Law – The Jessica Lunsford Act. (2010, December 27). Retrieved October 25, 2017, from http://www.floridabackgroundchecks.com/jessicas-law-the-jessica-lunsford-act/

Jimmy Ryce Act: Involuntary Commitment of Sexually Violent Offenders. (2017, January 16). Retrieved October 25, 2017, from https://brandonlegalgroup.com/jimmy-ryce-act-involuntary-commitment-of-sexually-violent-offenders/

Jones, B. J. (2015). Social Capital in America Counting Buried Treasure. Florence: Taylor and Francis.

Kardaras, N. (2017). Glow kids: how screen addiction is hijacking our kids - and how to break the trance. New York: St. Martins Griffin.

Klass, D. (1988). Parental grief: Solace and resolution. New York: Springer

Ladd-Taylor, M., & Umansky, L. (1998). "Bad" mothers: the politics of blame in Twentieth-Century America. New York: Plymbridge Distributors Ltd (UK).

Laxminarayan, M. (2015). Enhancing trust in the legal system through victims’ rights mechanisms. International Review of Victimology, 21(3), 273-286. doi:10.1177/0269758015591721

McCann IL, Sakheim DK, Abrahamson DJ. (1988) Trauma and victimization: A model of psychological adaptation. The Counseling Psychologist.16:531–594.

Missing and Exploited Children: Background and Policies. (2017, March 01). Retrieved October 25, 2017, from https://www.everycrsreport.com/reports/RL34050.html

Mundy, P. J. (1996). Statement of Kathryn Jean Shaffer Barrack (Report No. 96-02-0262). Homicide Investigation of Adam Walsh, Florida: HPD.

National Center for Missing and Exploited Children. (n.d.). Retrieved October 25, 2017, from http://www.missingkids.com/

Negra, D. (2010). Old and new media after Katrina. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

O'Brien, S., & French, J. L. (2008). Child abduction and kidnapping. New York, NY: Chelsea House.

Reauthorization and improvement of DNA initiatives of the Justice for All Act of 2004: hearing before the Subcommittee on Crime, Terrorism, and Homeland Security of the Committee on the Judiciary, House of Representatives, One Hundred Tenth Congress, second session, April 10, 2008. (2009). Washington: U.S. G.P.O.

Rinear, E. E. (1988). Psychosocial aspects of parental response patterns to the death of a child by Homicide. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 1(3), 305-322. doi:10.1002/jts.2490010304

Sedlak, A. J., Finkelhor, D., & Hammer, H. (2002). National Estimates of Missing Children: An Overview. PsycEXTRA Dataset. doi:10.1037/e321232004-001

Silverman, C. (2009). Regret the error: how media mistakes pollute the press and imperil free speech. New York: Union Square Press.

SMART Office - Sex Offender Sentencing, Monitoring, Apprehending, Registering, and Tracking. (n.d.). Retrieved October 25, 2017, from https://www.smart.gov/legislation.htm

Spencer, D., & Walklate, S. (2016). Reconceptualizing critical victimology: interventions and possibilities. S.l.: Lexington Books.

Spilman, S. K. (2004). Child abduction, parents distress and social support. Iowa: University of Iowa.

Sprague, D. F. (2013). Investigating missing children cases: a guide for first responders and investigators. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press.

Standiford, L., & Matthews, J. (2012). Bringing Adam home: the abduction that changed America. New York: Ecco.

Symonds, M. (2010). The “Second Injury” to Victims of Violent Acts. The American Journal of Psychoanalysis, 70(1), 34-41. doi:10.1057/ajp.2009.38

Swait, I. (2015). Retrieved October 25, 2017, from http://www.justiceforadam.com/box1.html

Walklate, S. (2018). Handbook of victims and victimology. London: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group.

Walsh, J. (1997). Tears of rage / the untold story of the Adam Walsh Case. New York: Pocket Books.

Waxman, O. B. (2016, August 10). Adam Walsh Murder: The Missing Child Who Changed America. Retrieved October 25, 2017, from http://time.com/4437205/adam-walsh-murder/

Wilson, J. K. (2009). The Praeger handbook of victimology. Santa Barbara, CA: Praeger.

Wojcik, P. R. (2016). Fantasies of neglect: imagining the urban child in American film and fiction. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

#law#essay#academic writing#adam walsh#criminology#history#murder#kidnapping#missing children#helicoptor parenting

0 notes