Beenish Khan | بینش خان | ビニシ・カーン Writing Gallery | Essays | Reviews | Misc | ♛ Art Portfolio ♛

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

ESSAY: The Law vs. Justice - A Troubling Dichotomy

"...Depictions of policemen – and recently, policewomen – as flawed but essentially courageous figures whose blatant disregard of rules should be forgiven because they care too much, fails to address a grim history of due process abuses by burying them beneath the facile premise of action-packed hijinks or zany comedy.”

In text or film, police stories run parallel to a mosaic of much-loved tropes and familiar cinematics: the steely-eyed officer staring down the barrel of a gun as he confronts the perp; the ubiquitous car-chase through a glittering metropolitan mise-en-scéne to the counterpoint of screeching tires and wild jazz; the athletic detective pursuing the antagonist through an urban maze of rooftops and stairwells, guns blazing and adrenaline pumping; the hard-edged police duo pummeling a snitch to a bloody pulp in a trash-strewn alleyway until he confesses to the information they're after. Genres switch from comedy to drama; protagonists evolve from stoic sleuths with a spotless badge and an unswerving mission to wisecracking cynics whose broken moral compass belies a heart of gold. Yet, as key figures in a discursive construction of culture, each character is elevated to near-sacrosanct levels of heroism for one reason: he will unflinchingly use violence to achieve his ends – not because he disregards the law, but because he has taken it upon himself to uphold justice. The dichotomy between the two, while incontestably age-old, is remarkable because the idea that one is an obstacle to achieving the other is a recurrent theme in law enforcement fiction – and because it appears to at once enable and ennoble police violence.

A cursory glance toward contemporary entertainment reveals how saturated it is with alternately gripping or poignant portrayals of the police – be they crime dramas, infotainment or film. Yet, when perusing a majority of these media-created depictions, it is also essential to note the dark skein of violence that runs through the narrative, framed as a necessity to maintain control within a gritty backdrop of urban decay (Deflem, 2010). From television shows like Law & Order, CSI Miami, The Wire and Chicago PD, which feature hard-nosed protagonists roughing up their suspects as par for the course, to critically-acclaimed films such as The French Connection (1971), Dirty Harry (1971), and Die Hard (1988), which showcase the ideal cop as a trigger-happy maverick willing to flout both institutional and legal safeguards to catch their perp, to more recent buddy-cop comedies such as The Heat (2013), where the quirky, would-be feminist twist attempts to call attention away from flagrant police abuses, there is a pervasive message that police brutality and misconduct are the panacea to clean up a city seething with crime.

The execution of this concept is certainly exciting from a storytelling standpoint. After all, there are countless instances where the law is stymied by historical framing, its message and purview a product of its times. Neither ironclad nor teleological, laws evolve according to their own methodology, not in smooth sequences but in messy, haphazard, often incoherent increments that reflect the protean nature of society itself (Hutchinson, 2005). However, the diegesis of law vs. justice becomes fraught with complications when it is used repeatedly to promulgate fictional constructs as truth – to frame violence as the only means to fight fire with fire, with the hero cop acting in the best interests of the underdog, against antagonists who will ultimately and most deservedly be trounced in a simplistic narrative arc of Good versus Evil (Geller, 1997; Jacobson, Picart & Greek, 2017). Unfortunately, what these formulas tend to overlook – either due to disingenuity or pure carelessness – is how they function as propaganda pieces for institutions already entangled in civil rights violations. More to the point, their depictions of policemen – and recently, policewomen – as flawed but essentially courageous figures whose blatant disregard of rules should be forgiven because they care too much, fails to address a grim history of due process abuses by burying them beneath the facile premise of action-packed hijinks or zany comedy.

To be sure, crime dramas have been a popular staple of entertainment for decades. In their work, Media and Crime in the U.S, criminologists Yvonne Jewkes and Travis Linnemann remark that crime films are "arguably the most enduring of all cinematic genres..." and that their attraction is rooted in the fact that they "reassure us that criminal behaviors can be explained and serious offenses can be solved. They offer immutable definitions of 'the crime problem' and guide our emotional responses to it" (2017, p. 173). But beyond the comforts of catharsis and closure, these films provide an intimate view into worlds that exist as ciphers to the general public. Research has repeatedly shown that viewers glean knowledge of law enforcement not from direct interaction with said entities, but from mass media consumption (Surette, 1998; Skogan, 1981; Mawby, 2003). While public opinions of policemen are, on the whole, encouragingly positive (Huang and Vaughn, 1996), it is imperative to ask ourselves whether these opinions are factual or colored by the glamour and gloss of mediated representations. In their work, Media Consumption and Public Attitudes toward Crime and Justice, Kenneth Dowler and Valerie Zawilski note that,

Presentations of police are often over-dramatized and romanticized by fictional television crime dramas while the news media portray the police as heroic, professional crime fighters. In television crime dramas, the majority of crimes are solved and criminal suspects are successfully apprehended. Similarly, news accounts tend to exaggerate the proportion of offenses that result in arrest which projects an image that police are more effective than official statistics demonstrate. The favorable view of policing is partly a consequence of police’s public relations strategy. Reporting of proactive police activity creates an image of the police as effective and efficient investigators of crime (2007, p. 3).

Of course, it would be simplistic to claim that all audiences imbibe and interpret media-constructed images of police in the same fashion. As Yvonne Jewkes remarks in the work Captured by the Media, "people are not blank slates who approach a television programme without any preexisting opinions, prejudices or resources" (2013, p. 145; Kitzinger, 2004). However, it is equally impossible to believe that these sources do not feed social constructions of law and order in its myriad forms. Indeed, the media's portraits of crime and justice are often pivotal in influencing both policy and day-to-day events. A large body of research devoted to the relationship between public attitudes and criminal justice policy has shown that representations of crime news catalyze public pressure toward harsher policing and more punitive sentencing. Additionally, a close appraisal of police-related television shows and films yields disturbing trends. Not only is there an overblown emphasis on offender-based violence, i.e. murder, rape, and robbery, but the offenders themselves are portrayed as cunning to an almost, if not outright, psychopathic degree. They can play the criminal justice system like a fiddle, and can run circles around the average police officer, whose by-the-book approach only leaves him/her mired in red-tape and frustratingly stultified by Internal Affairs. Instead, it is up to a tenacious few, with the guts and grit to transcend these bureaucratic impositions, to dispense justice towards offenders (Barille, 1984; Surette, 1998).

Given that the ontological divide between fiction and fact can often risk becoming disquietingly blurred, the study of sensationalist fiction's influence on criminal justice policy becomes doubly relevant (Potter & Kappeller, 2006). An example can be taken from 24, a hugely-popular Fox Network series that ran from 2001 to 2008. The show followed the exploits of counterterroist Jack Bauer, a resourceful anti-hero willing to resort to everything from mass property destruction to torture in order to save the American public. Bauer's legacy survived well beyond the screen, to the point where he was cited by the late Supreme Court Justice, Anton Scalia, as pertinent to constitutional jurisprudence and the use of torture: "Jack Bauer saved Los Angeles. ... He saved hundreds of thousands of lives. Are you going to convict Jack Bauer?" The fact that Bauer does not exist is beside the point; rather, it is the durable imprint his heroics left on the minds of the audience. For them, the thrilling, nick-of-time rescues and terrorist intrigues exemplified by 24 were not escapist fantasies, but a dire reflection of the national state of affairs (Lattman, 2006, p. 1).

Similarly, Clint Eastwood's wild card, Harry Callahan, immortalized by the 70s cult classic Dirty Harry, is portrayed as a ruthless but ultimately effective cop whose willingness to bend – or break – the rules guarantees fast results. What makes the film particularly noteworthy is its scathing criticism of the perceived hurdles beset upon law enforcement via the enactment of the Miranda warning in 1966, in addition to would-be obstacles such as the Exclusionary Rule. Whether or not the film's legal research is rooted in accuracy is, again, beside the point: its true premise is to question whether a system that gives precedence to the rights of offenders over victims is even worth upholding. In the film's closing scene, Harry, having broken the law by shooting the rampaging sniper, Scorpio, tosses his police badge into the water – an act as politically charged as it is defiant. Through Harry, not only is the upheaval of the period's political climate reflected, but the passions of the viewers enacted (Leitch, 2007). Indeed, the Dirty Harry Syndrome – also known as Noble Cause Corruption – is a term coined by the film, although the phenomenon understandably predates it. Jack R. Greene describes it as when "police are tempted to use illegal means to obtain justice... [even though] police ethicists and lawmakers hold that any gains that might be achieved by illegal means are not worth the miscarriages of justice and negative precedents that might result" (2006, p. 601). However, the film's enduring popularity is testament as much to its directorial finesse as to the resonance of its underlying message: that in order for justice to prevail, pragmatic vigilantism is preferable to the impractical hurdle of upholding civil rights. Like his modern predecessor, Jack Bauer, Harry Callahan's actions serve to anchor him within a timeless cultural bricolage: the everyman's avenger who occupies the liminal space between saint and rebel for his steadfast pursuit of justice.

In his work Encoding & Decoding in the Television Discourse, renowned cultural theorist Stuart Hall coined the term 'Circuit of Communication' to argue that, despite the assumption of meaning as a static agent, it is in fact a socially structured process that can either edify or delimit us through its visual language and representation (1973). Indeed, the meaning of any medium can be considered a sociopolitical and cultural discourse with its own style, syntax, structure and vocabulary – all of it pivoting on the audience as both the 'receiver of the message, and the 'source.' With that in mind, police films and dramas do not exist in a vacuum, but are in fact embedded in contingent social realities, many of which serve largely to either reflect or perpetuate specific modes of thought and conduct. One need only trace the complex evolution of law enforcement on-screen to observe how they establish specific notions of law vs. justice, good vs. evil, order vs. disorder, within a specific sociopolitical milieu.

For instance, the earliest film noir classics such as Double Indemnity (1936) were pivotal in bringing to life the postwar disenchantment and murky morality of the era, while touching upon gender politics, social mores, and their shocking subversions. Similarly, the besieged and troubled characters of Hitchcock's Vertigo (1958) served almost as widgets fulfilling a critique on sexual politics and mass surveillance. The late 1960s relaunch of the genre-defining radio and television series Dragnet (1949-70) was designed to tout the impressive intricacies of LAPD procedurals, in an age characterized by anti-police sentiment and the infamous Watts Riots.

Later, the Nixonian legacy of the War on Drugs, and its subsequent Reaganite expansion, saw the rise of such Cop Booster classics as 48 Hours (1982) and Lethal Weapon (1989). More recent films such as Crash (2005), while attempting to touch thoughtfully upon racial tensions in the melting pot of LA, quickly became entangled in undercurrents of misogynoir and color-blindness by suggesting that the officer who committed digital rape on a black woman was redeemed by later saving her from a car crash, and by asserting superficial equality with the idealistic message that everyone across the racial spectrum has problems, while conveniently denying the reality of systemic racism in a white power structure (Hobson, 2008; Lott, 2006). Even the latest blockbuster, The Heat (2013), which aimed to subvert gender roles in law enforcement, unfortunately tripped over its own message by becoming not a paean to feminism but a stale, formulaic buddy-cop cliché that equated female empowerment with the same reckless disregard and gross misconduct vis-à-vis its male-centric counterparts.

At nearly every point, cop films and dramas appear to be a means to either challenge or embellish institutional authority. Yet no matter their superficial advancements, very few focus on the realities of police-work, such as preventive and proactive strategies, much less on efforts at rapport-building – or lack thereof – within the community they protect. Fewer still address blatant acts of police violence and misconduct not as effective tools, but as risky perpetuations of Hobbesian logic where good must vanquish evil by any means necessary.

However, it is imperative to understand how this rigid binarization circumvents meaningful and nuanced dialogue. By resorting to cursory labels that pit one 'side' against the other – and, indeed, create sides at all – it is dangerously easy to frame entire groups of people, policies, and phenomenon as irrational threats that can only be eradicated by extralegal and increasingly ruthless means (Parenti, 2003). Certainly, recent history has seen the expansion of law enforcement as justification to eradicate a 'newer, deadlier' breed of enemies beyond the scope of conventional legality. In the wake of the 9/11 attacks, for instance, former President George W Bush denounced the tragedy as "a new kind of evil" that had to be fought "in the shadows." Constitutional safeguards therefore had to be set aside out of necessity, in order to protect the greater good. The outcome would lead to two wars, increasing governmental opacity, the establishment of the Patriot Act, mass domestic surveillance, and the unspoken sanctioning of 'enhanced interrogation techniques' on terror suspects (Graham, 2004; Nakashima, 2007; Purdum, 2001, p. 1).

While national security – internal and external – is certainly of prime importance, it is necessary to understand the risks of being engulfed and acclimatized to an atmosphere of terror, through which the media derive profit, politicians push insidious agendas, and financial systems subjugate and surveil public activities. Furthermore, into this commodification and mass consumption of terror, recent trends towards more egregiously aggressive cop shows, and the expansion of police power they reflect, deserve critical focus. In his book, The Rise of the Warrior Cop: The Militarization of America's Police Forces, Radley Balko remarks that, "No one made a decision to militarize the police in America. The change has come slowly, the result of a generation of politicians and public officials fanning and exploiting public fears by declaring war on abstractions like crime, drug use, and terrorism. The resulting policies have made those war metaphors increasingly real" (2014, p. 42).

To decry the media as the sole instigator of fear-mongering would, of course, be unfair. But nor can it be denied that the media in all its forms plays a pivotal role in reinforcing the black-and-white paradigm of law vs. justice, with the heroes willing to achieve their goals at any cost, be it torture or deception (Rafter, 2006). While such narrative designs can be compellingly escapist and entertaining, they run the risk of becoming so entrenched into the social fabric and psyche as to seem factual. A no-holds-barred, take-no-prisoners approach to law enforcement would seem ideal for convicting the indisputably guilty – but the fact of the matter is that the deliberate disregard of procedural law will only undermine the liberty interests of the innocent. Films and television shows that continue to push this agenda merely misrepresent police misconduct as a legitimate validator of heroism, and therefore of goodness. The protagonist is elevated to near-sacrosanct levels for one reason: he will unflinchingly use violence to achieve his ends – not because he disregards the law, but because he has taken it upon himself to uphold justice. Yet regarding the two as mutually exclusive is not only pandering to teleological delusion, but masking the reality of a deeply flawed justice system by redefining criminality as the darkest shade of evil, and police misconduct as the only means to take it down.

References

Balko, R. (2014). Rise of the Warrior Cop: The Militarization of America's Police Forces. Perseus Books Group.

Barille, L. (1984). “Television and Attitudes About Crime: Do Heavy Views Distort Criminality and Support Retributive Justice?” In Ray Surette (ed.) Justice and the Media: Issues and Research. Springfield, Illinois: Charles C. Thomas.

Deflem, M. (2010). Popular Culture, Crime and Social Control. Sociology of Crime, Law and Deviance, Iii. doi:10.1108/s1521-6136(2010)0000014019

Dowler, K., & Zawilski, V. (2007). Public perceptions of police misconduct and discrimination: Examining the impact of media consumption. Journal of Criminal Justice, 35(2), 193-203. doi:10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2007.01.006

Geller, W. A., & Toch, H. (1997). Police violence: understanding and controlling police abuse of force. Choice Reviews Online, 34(08). doi:10.5860/choice.34-4799

Grahan, B (2004). As an issue, war is risky for both sides. Washington Post. Available at http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/articles/A1575-2004Oct1.html. Accessed on September 21.

Greene, J. R. (2006). Encyclopedia of Police Science. doi:10.4324/9780203943175

Hall, S. (1973). Encoding and decoding in the television discourse. Strasbourg: Council of Europe.

Hobson, J. (2008) Digital Whiteness, Primitive Blackness. Feminist Media Studies, 2 (8), 111-126. doi: 10.1080/00220380801980467

Huang, Wilson W.S. & Michael S. Vaughn. (1996). “Support and Confidence: Favorable Attitudes Toward the Police Correlates of Attitudes Toward the Police.” In T.J. Flanagan and D.R. Longmire (eds) Americans View Crime and Justice: A National Public OpinionSurvey. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage Publications.

Hutchinson, A. C. (2005). Evolution and the common law. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Jewkes, Y., & Linnemann, T. (2017). Media and crime in the U.S. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

King, N., Picart, C. S., Jacobsen, M. H., & Greek, C. (2017). Framing Law and Crime: An Interdisciplinary Anthology. Contemporary Sociology: A Journal of Reviews, 46(5), 586-587. doi:10.1177/0094306117725085ff

Kitzinger, J. (2004). Framing abuse: media influence and public understanding of sexual violence against children. London: Pluto Pr.

Lattman, P. (2007). Justice Scalia hearts Jack Bauer. Wall Street Journal. Available at http://blogs/wsj.com/law/2007/06/20/justice-scalia-hearts-jack-bauer/. Accessed on September 21, 2017.

Leitch, T. (2007). Crime films. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Lott, M. R. (2006). Police on screen: Hollywood cops, detectives, marshals, and rangers. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co.

Mason, P. (2013). Captured by the media: prison discourse in popular culture. London ; New York: Routledge.

Mawby, R.I. (2003) 'Evaluating Justice Practices', in A. Von Hirsch et al (eds) Restorative Justice and Criminal Justice: Competing or Reconcilable Programs? Oxford: Hart Publishing.

Nakashima, E. (2007) A story of surveillance: Former technician 'turning in' AT&T over NSA program. The Washington Post. Available at http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2007/11/07/AR2007110700006.html. Accessed on September 25, 2017.

Parenti, C. (2003). The Soft Cage: Surveillance in America From Slavery to the War on Terror (Reprint Edition). New York, NY: Perseus Books.

Potter, G. & Kappeler, V. (Eds). (2006). Constructing Crime: Perspective on Making News and Social Problems. Chicago: Waveland Press.

Purdum, T. S. (2001, September 16). Bush Warns of a Wrathful, Shadowy and Inventive War. Retrieved November 10, 2017, from http://www.nytimes.com/2001/09/17/us/after-attacks-white-house-bush-warns-wrathful-shadowy-inventive-war.html

Rafter, N. (2006) Shots in the mirror: Crime films and society. New York: Oxford University Press.

Roberts, J. & A. Doob. (1986). “Public Estimates of Recidivism Rates: Consequences of a Criminal Stereotype.” Canadian Journal of Criminology 28:229-241. gy 28:229-241.

Skogan, W. & M. Maxfield. (1981). Coping With Crime. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications.

Surette, R. (1998). Media, Crime, and Criminal Justice: Images and Realities 2nd Edition. New York: Wadsworth Publishing.

0 notes

Text

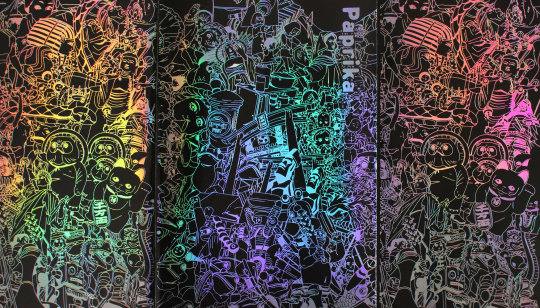

ESSAY: Globalization - Limits & Liminality as Explored in “Paprika”

Kon’s animated film Paprika, through symbolic and stylized means, serves as a critical frame for the phenomenon of globalization.

X-Posted at Pangaea Journal

Inspired by Yasutaka Tsutsui’s titular novel, Paprika begins much in the same fashion as it ends: in medias res, with a phantasmagorical montage of cultural iconography, quirky characters and surreal scenery interwoven at a frenzied pace, each scene jumping into the next with a fluidity that coalesces time and space itself into a distinctly Einsteinian continuum. Audiences are left dazed, disoriented, yet intrigued: there is no way to know whether the introductory sequence is chronicling a dream, or reality, or a freakish blend of both. This destabilizing visual narrative is fairly typical of Satoshi Kon’s craft, yet what calls for critical focus is the unique symbolism underpinning his work. Beneath its rich and densely-layered imagery, the film tackles a number of pertinent issues: from whether multimedia has warped from a benign platform into the jealous architect of our desires; to the tragic dissolution of individual ideas and complex cultures into a miasma of grotesque transnationalism; to whether the weakening friction-of-distance within a digitized world has brought us closer together, or merely distorted the very axes upon which time-space functions and is perceived. Indeed, at its crux, the film embraces a broad spectrum of issues uniquely linked to globalization, all while invoking relevant aspects of human fallacy and social degradation.

Central to Paprika, from the beginning, is its clear disdain for the linearity and two-dimensionalism of traditional narrative. Instead, like a hallucination, there appear to be no distinguishable boundaries between characters or places, no fixed destinations or rational coordinates. The most vivid example is the introductory sequence, where the eponymous protagonist, Paprika, leaps winsomely out of a man’s dreams and into the physical world: flitting from brightly-lit billboards as static eye-candy to a well-meaning sentry spying through computer screens to a godlike specter freezing busy traffic with a snap of her fingers to an ordinary girl chomping hamburgers at a diner to a stylized decal on a boy’s T-shirt to a motorcyclist careening through late-night streets (0:06:12-0:07:49).

Space and time are rendered meaningless – or, rather, are reshaped into something entirely novel and surreal. As Paprika navigates through a complex and dynamic mediascape, she effectively embodies the spilling-over of the virtual into the physical world – and, more significantly, of both the subtle and blatant permeation of media-based globalization in every step of our lives. Indeed, with its alternately fascinating and disturbing chaos of imagery, the very premise of Paprika blurs the boundaries between the inner and outer-worlds, conveying through both symbolic and subtextual allusions the phenomenon of globalization run riot – a dreamscape that unfolds with the benign promise of forging new connections, only to seep past the barriers of reality and engulf and reshape the world to the imperatives of dystopian homogeneity at best, and the subjugation and disintegration of individual autonomy at worst.

It can be argued, of course, that it is hypocritical for animation – in many ways the nexus of metamedia in its most intrinsically illusory form – to lambaste globalization. The media pivots on globalization in all its multifaceted vagaries, and vice versa. Renowned social theorist Marshall McLuhan, who coined the phrase ‘the global village’ in his groundbreaking work The Medium is the Message, was one of the first to point out that the form of a medium implants itself inextricably into whatever message it conveys in a synergistic relationship: “All media work us over completely. They are so pervasive in their personal, political, economic, aesthetic, psychological, moral, ethical, and social consequences that they leave no part of us untouched, unaffected, unaltered (26).” That the media and the phenomenon of globalization go hand-in-hand, shaping and influencing one another, therefore goes without saying. However, what the imagery of Paprika draws attention to is how the multiplicity of media leads to unpredictable consequences and vicissitudes – which are not always quantifiable or even tangible. Much in the same way technology and global interconnectivity have narrowed – at times even erased – the demarcations of time and space, so too have they led to paradigm shifts of what it means to belong to a static, physical place as a cultural and individual identifier.

Globalization is often defined as fundamentally kaleidoscopic, with a dizzying mobility of ideological, economic, physical and cultural interchanges across a rhizomatous network – but one that is increasingly powered by its own unstable energies and its own besieged and untidy logic. Of particular interest is the ‘disembodied’ component of globalization, where the flow of information and capital is increasingly encoded and abstract, and thus increasingly more likely to permeate local spaces that may not always be open to such profound transformation, imposition and redefinition. In their work, The Quantum Society, Zohar and Marshall liken the chaotic, fractal nature of the modern world to quantum reality, stating that it

…has the potential to be both particle-like and wave-like. Particles are individuals, located and measurable in space and time. Waves are ‘nonlocal,’ they are spread out across all of space and time, and their instantaneous effects are everywhere. Waves extend themselves in every direction at once, they overlap and combine with other waves to form new realities, new emergent wholes (326).

Unarguably, the focal point in Paprika is globalization as a catalyst of “new realities.” But while these can be captivating and edifying, allowing us to create or explore new identities, or to grow more closely tethered together, they can also represent the sinister infiltration of exploitative elements within our most intimate lives. This is made chillingly evident through the plot of the film, which centers on the theft of the DC Mini – a futuristic device that allows two people to share the same dream. While intended as a tool to help treat patients’ latent neuroses and deep-seated pathologies, the film makes clear that, if misused, this prototype can not only allow an intruder to access and influence another’s dreams, but can unleash the collective dream-world into the sphere of reality itself. The DC Mini, on its own, would function as a tepid metaphor for the symbiotic dance between globalization and technology. But following its theft, the resultant chaos it invokes sets the riveting, psychedelic stage upon which the inner-world of dreams erupts out into mundane reality, a fantastical convergence that not only threatens the safety of the entire city, but also denies each citizen their own private realm of dreams, within which they have the freedom to nurture a true inner-self. As Dr. Chiba – the no-nonsense alter-ego of our dreamscape superheroine Paprika – remarks: the victims of the abused DC Mini have become mere “empty shells, invaded by collective dreams… Every dream [the stolen DC Mini] came into contact with was eaten up into one huge delusion.” The scene is made particularly memorable by its vivid visual symbolism: two droplets of rainwater on a car window merging into one, highlighting the irresistible flow between not only dreams and reality, but the liminality of globalization as a fluid force that cannot be bound by temporal or spatial delineations (0:52:12-0:52:37).

It is precisely this unpredictable fluidity that runs rampant across real-life Tokyo in the film, wreaking havoc in its wake. Of particular interest is the gorgeous riot of imagery employed to represent the collective ‘delusion:’ the recurring motif of a parade, in all its clamorous splendor, that unfurls through the city streets, infusing spectators with its own peculiar brand of madness. For its eye-popping and mind-bending details alone, the sequence warrants close examination. But accompanying the visual feast is the nightmarish gamut of cultural, technological, social and historical commentary embedded within its imagery. To the cheerful proclamations of, “It’s showtime!” a procession of Japanese salarymen leap with suicidal serenity off of rooftops; below, the bodies of drunkenly-staggering bar-hoppers morph into unbalanced musical instruments, while families frolicking through the parade transform into rotund golden Maneki-neko to disturbing chants of, “The dreams will grow and grow! Let’s grow the tree that blooms money!” Here, in a scathing political lampoon, politicians wrestle one another in their eagerness to climb to the top of a parade-float; there, a row of schoolgirls in sailor uniforms, with cellphones for heads, lift their skirts for the eager gazes of equally cellphone-headed males.

Satoshi Kon does not bother with coy subtext; he announces the mind-degenerating effects of globalization on both dramatic and symbolic planes: a parade that swells into disorder and eventual destruction, headed by a clutter of sentient refrigerators, televisions, microwave ovens, vacuum cleaners, deck tapes and automobiles. Traditional Japanese kitsch competes with lurid Americana; cultural symbols like Godzilla and the Statue of Liberty waltz alongside such religious icons as the Virgin Mary, Vishnu and the Buddha, while disembodied torii arches and airplanes soar overhead to the discordant serenade of money toads and durama dolls. The effect is at once hypnotic and horrific; the vortex of collective dreams lures in countless spellbound bystanders, transforming them into just another mindless facet of the parade, from a robot to a toy to a centerpiece on a parade-palanquin. Witnessing the furor, one character dazedly asks, “Am I still dreaming?” and is informed, “Yes. The whole world is” (1:11:09-1:12:42)

In her book, Girlhood and the Plastic Image, Heather Warren-Crow remarks that Paprika “…proffers a visual theory of media convergence as not only an issue of technology, but also one of globalization… [Its] vision of media convergence is one in which boundaries between cultures, technologies, commodities and people are horrifyingly permeable… While our supergirl is eventually able to stop the parade… these multiple transgressions cause mass confusion, madness, injury and death (83).” If this seems a dark denouncement of globalization, one cannot deny that it is in many respects fitting. With the vanishing delineations between nations, cultures, ideas and people arises the phenomenon of “cultural odorlessness,” or mukokuseki. The term was first applied to rapid social transformations in Koichi Iwabuchi’s book Recentering Globalization: Popular Culture and Japanese Transnationalism, although the phenomena can just as readily be applied to postmodernity in all its miscellaneous facets (28). While globalization has engendered new intimacies and easier connections (on the surface), this overwhelming grid of interconnected information has simultaneously become a web trapping human beings inside it. Individuality – on a national, local, or personal scale – has been pushed aside in favor of a real and virtual superhighway powered by pitiless self-commodification and voracious consumership, within which the cultivation of a true self no longer holds meaning. One particular scene in the film captures this with wistful succinctness. As a weary Dr. Chiba gazes out of the window of her office, her livelier alter-ego Paprika (real or imagined) appears superimposed before her reflection. “You look tired,” Paprika says, “Want me to look in on your dreams?” to which Chiba replies, “I haven’t been seeing any of my own lately.” Against Paprika’s winsome overtones, her own demeanor strikes a chord that is dismal in its flatness. Although Chiba’s profession is to dive through the colorful welter of others’ dreams, it is her grasp of her own self that proves the ultimate fatality in this venture (0:24:10-0:24:23).

Indeed, it has often been argued that as both the physical and disembodied aspects of globalization grow increasingly more pervasive, so too do diverse organs of surveillance – from institutionalized dogmas meant to restrict personal development by branding it as outdated or subversive, to internal and external disciplinary structures meant to monitor and subjugate a person’s ‘inner-self:’ the very stuff of his or her dreams. Such themes, while hardly novel, are nonetheless relevant, tethered as they are to such iconic works as George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four, and Michel Foucault’s Discipline and Punish, both of which – through literal and metaphorical means – examine societies wherein people are subject to relentless government scrutiny, mind-policing and the absolute denial and denigration of privacy. Foucault’s work, in particular, is useful for deconstructing social mechanisms. Utilizing a genealogical historical lens, Foucault traces the slow and oppressive transformation – as opposed to ‘evolution’, a phrase often touted by proponents of liberal reform – of the Western penal system. His main focus is to illustrate how, despite our self-congratulatory complacence at moving away from the barbaric model of medieval punishment, in favor of gentler and more civilized modes of discipline, we have in fact simply transferred the imperatives of controlling human beings – be they deviants or conformists – from their bodies to their souls. As Foucault states, “Physical pain, the pain of the body itself, is no longer the constituent element of the penalty. From being an art of unbearable sensations punishment has become an economy of suspended rights,” thus intimating that the organs of institutional control have not grown less harsh or restrictive, but simply less overt (11).

Certainly, by relying on a framework of internal rather than external constraints, it has become possible to erode the very modicum of individuality, reducing human beings to what Foucault describes as “docile” bodies complicit in their own exploitation. Foucault lays the blame for this phenomenon on a capitalist system whose economic and political trajectory has led society to a place of commodification and classification (“governmentality”), where the complexities of dynamic individuals are pared down into reductionist categories of ‘acceptable’ or ‘unacceptable.’ According to Foucault, surveillance and regimentation as a means of producing compliant individuals is the crux of modern economies, to the point where society has transformed into an industrial panopticon – a nightmarish perversion of Jeremy Bentham’s original ideal. As such, whether individuals live as offenders within a prison, or as free citizens, is irrelevant. The scant difference in both their constraints is measured by mere degrees (102-128).

In Paprika, these issues are not explicitly announced, but are instead woven through the story’s fabric in an alternately lulling and disquieting fashion. Noteworthy scenes – such as where Paprika, a captive chimera with butterfly-wings, is pinned to a table while a man literally peels away her skin to paw rapaciously at the prone body of Dr. Chiba, nestled pupae-like within, to the moment where Detective Toshimi Konakawa, harried by recurring nightmares, bittersweetly comes to terms with boyhood dreams he had suppressed in order to survive by the dictum of a cold and prescriptive adult world – are all reminders that it is our inviolate inner-space that makes us uniquely human. To allow it to be invaded, subjugated and erased is to reduce ourselves to passive automatons, our every desire governed, our every choice predetermined. In Paprika, this knowledge blossoms only when each character delves deep into themselves, to find at their core the dream-child that remains untouched by reality’s smothering hold, and to discover within that dream-child both untapped softness and strength. “She’s become true to herself, hasn’t she?” Paprika playfully remarks of the somber Dr. Chiba, when the latter finally comes to terms with her repressed affection for the bumbling genius Tokita (1:15:42).

For Paprika, it is evident that social or technological transformations cannot be powered by the erosion of individual dreams. To do so is to condemn the world to an eldritch darkness sustained only by greed. The film’s penultimate scene, where the egomaniacal chairman – the true thief of the DC Mini – looms as a monstrous giant over the despoiled city, proclaiming, “I am perfect! I can control dreams and even death!” could almost serve as the critical foreshadowing of globalization taken to its bleakest conclusion: the desecration of nature and humanity alike by a self-serving force that, in its thirst for absolute control, will cancel out the very diversity of dreams that once made globalization possible. It is only when Paprika – fusing with Dr. Chiba and Tokita – reemerges in the form of a baby to battle the chairman, is equilibrium restored. “Light and dark. Reality and dreams. Life and death. Man and woman. Then you add the missing spice [Paprika],” she recites, as if listing ingredients to a recipe (1:19:50-1:20:32). Yet, in keeping with theme of liminality and indeterminacy, the key to vanquishing the chairman is not in these binary oppositions, but in their capacity to combine together and shape the world into more than one thing at once. As Paprika swallows the chairman whole, reversing the shadowy post-apocalyptic city to its original state, battle-scarred but still intact, the audience is reminded of fluidity of the quantum world. Life and death, dreams and reality, destruction and rebirth, all coalesce within an ever-transforming continuum.

So too, as the film’s open-ended yet distinctly uplifting ending makes clear, is the process of globalization inherently free-flowing and malleable in its interaction with its environment. Rather than focusing on the split between globalization as a force of cultural erasure versus a celebration of differences, the film highlights the alternately delicate or brutal negotiations between the two: a friction that is necessary to keep the phenomenon in flux. Zygmunt Bauman’s book and selfsame concept of Liquid Modernity proves especially useful here, in that in order to comprehend the mutable nature of the modern world, it is necessary to look beyond traditional models and regimented perceptions. As he makes clear:

Ours is … an individualized, privatized version of modernity, with the burden of pattern-weaving and the responsibility for failure falling primarily on the individual’s shoulders… The patterns of dependency and interaction … are now malleable… but like all fluids they do not keep their shape for long. Shaping them is easier than keeping them in shape. Solids are cast once and for all. Keeping fluids in shape requires a lot of attention, constant vigilance and perpetual effort – and even then the success of the effort is anything but a foregone conclusion (8).

Of course, the exchange of images and ideas across a would-be deterritorialized realm does not mean that the myriad components within must lose their separate identities. Rather, those identities become more essential than ever, bringing with them their own consequences and questions – all of which must be understood through the dynamic lens of globalization, until we come to understand not only the frailties of the social order, but how they can improved, in order to make connections both genuine and mutually-beneficial for a polyphonic future. The answers lie not within the inherently-shifting structure of globalization, but rather in its creative use. In the film’s final segment, where Detective Toshimi Konakawa purchases tickets to the movie, Dreaming Kids, after decades of stultifying self-repression, speaks of the capacity of globalized multitudes to enthuse as well as to ensnare the individual’s dreams. Globalization does not exist in a vacuum; even as it threatens to engulf nations, localities and persons into a bilious swamp of depersonalized shells, so too can it be transformed by the nature of the worlds it encounters. The change is double-edged and double-sided; the effect is a living, breathing bricolage that grows and alters as we do – and how we do.

That said, it is evident that Satoshi Kon’s message is not one of a facile globalized utopia. Rather, it is about the dangers of losing ourselves within such a seductive phenomenon, whose effects can too easily be maneuvered toward mass surveillance and subjugation. For Paprika, the cross-flow of cultures, ideas, commodities and people is illustrated as an unceasing process, but one that we ourselves are responsible for shaping. If done right, there is the tantalizing promise of a happier, freer life, within which globalization may enhance rather than exploit our dreams. But if done wrong, Kon’s narrative is bleakly apocalyptic – a world fallen victim to a hostile and all-pervasive force that gnaws away its very humanity. While the film’s content-driven, as opposed to structural, formula can be mystifying and overly-abstract at times, there is no denying its visual ingenuity: a multimedia extravaganza that beautifully translates the welter of dreams into reality. With its alternately fascinating and disturbing chaos of imagery, Paprika blurs the boundaries between the inner and outer-worlds, conveying through symbolic and subtextual allusions the phenomenon of globalization run riot – a dreamscape that yields both brighter possibilities and special connections if we do not allow it to diminish us, yet also a sinister agency of mass domination and dystopian homogeneity if we fail to put it in its proper place.

Works Cited

Bauman, Zygmunt. Liquid Modernity. Cambridge, UK, Polity Press, 2015.

Foucault, Michel. Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. New York, NY, Random House LLC, 1977.

Iwabuchi, Koichi. Recentering Globalization: Popular Culture and Japanese Transnationalism. Durham, Duke University Press, 2007.

Kon, Satoshi, director. Paprika. Madhouse Studios, 2006.

MacLuhan, Marshall. The Medium is the Message. Corte Madera, Gingko Pr., 2005.

Warren-Crow, Heather. Girlhood and the Plastic Image. Lebanon, University Press of New England, 2014.

Zohar, Danah, and I. N. Marshall. The Quantum Society: Mind, Physics and a New Social Vision. New York, Morrow, 1994.

1 note

·

View note

Text

ESSAY: Examining the PLRA

Cases have been recorded of inmates' grievances rejected by the prison administration for writing in the wrong color of ink, for scribbling on the back of the form, or for missing the narrow window of filing deadlines. Many argue that prisoners flung into this Kafkaesque labyrinth of mechanisms will find their cases—no matter how meritorious—consigned to oblivion.

To describe the legal system of the United States as beleaguered is an understatement. Confronted with bulging carceral populations, soaring costs, and an influx of litigation, our courts have, time and time again, fought to keep from buckling under the strain of their caseloads—often at the cost of yielding where they should uphold their commitment to the rule of law. Within the workings of this overwhelmed system, the appellate courts play the vital role of a filtering apparatus. In 1995, approximately fifteen percent of the civil suits received by federal courts were filed by prisoners. Of these suits, ninety-seven percent were dismissed, with only thirteen percent granted declarative or injunctive relief (Schlanger 2). This astonishingly low success rate reflected the presumption—whether canard or fact—that a majority of prisoner litigation was frivolous, and unworthy of courts' attention. Indeed, by the 1990s, the volume of inmate claims had reached such heights that Congress was compelled to address the crisis. In 1995, in a hearing before the Senate for the Department of Commerce, Justice, and State, it was reported:

The number of lawsuits filed by inmates has grown astronomically – From 6,600 in 1975 to more than 39,000 in 1994. These suits can involve such grievances as insufficient storage locker space, a defective haircut by a prison barber, the failure of prison officials to invite a prisoner to a pizza party for a departing prison employee, and yes, being served chunky peanut butter instead of the creamy variety (U.S. Senate. Dept. of Commerce, Justice and State 1995).

To combat the pandemic, Congress enacted the Prison Litigation Reform Act (hereafter referred to in this paper as the PLRA) in 1996. Intended as a mechanism to close the floodgates of litigation, the PLRA's provisions seek to restrict meritless inmate suits so that higher-quality cases may be allowed review on the court docket. One provision states that no inmate shall bring forward a suit under federal law, until all available "administrative remedies" are exhausted. Additionally, under a second provision, the PLRA imposes a negative penalty—a "strike"—wherein a court may dismiss a prisoner's lawsuit on the basis that it is frivolous, malicious or has failed to state its claim (Boston & Manville 564-550).

At the time of its passage, the PLRA garnered widespread bipartisan support as it was intended to ameliorate the judicial process. To be sure, following its enactment, the volume of prisoner litigation significantly dropped. Barely within four years of its passage, the total number of prisoner lawsuits in federal courts declined by 40%. More significantly, the PLRA's broad provisions were lauded for ferreting out "junk litigation" and subsequently reducing the burdensome judicial workload. However, these same features sparked fierce backlash. Many believed that, far from streamlining inmate claims, the PLRA introduced a thicket of administrative barriers intended to discourage inmates from airing serious abuses (Ostrom et al.1536).

Prior to 1996, the standard for grievance processes was set by the Justice Department, and was intended predominantly for federal prisons. The PLRA has cast this aside; as of today, there are no regulations outlined for prison grievance procedure. Critics are also concerned with the capricious nature of the regulations themselves. Cases have been recorded of inmates' grievances rejected by the prison administration for writing in the wrong color of ink, for scribbling on the back of the form, or for missing the narrow window of filing deadlines (Hearing on H.R. 4109, Prison Abuse Remedies Act of 2007). Many argue that prisoners flung into this Kafkaesque labyrinth of mechanisms will find their cases—no matter how meritorious—consigned to oblivion.

Over two decades have passed since the passage of the PLRA. However, it continues to stir contentious debate—among scholars, politicians and inmates alike. As recently as August 21, 2018, a nationwide prison strike was launched, in an attempt to expose the worrisome underbelly of prison administrations. The strike was spearheaded by the Incarcerated Workers Organizing Committee (IWOC), a prisoner-led trade group. Intended to unionize incarcerated persons, the IWOC values emancipation, equal rights and community safety. With their championing, the prison strike attracted significant media attention, as well as garnering widespread inmate solidarity. Similar strikes were reported to have spanned across prisons in California, Delaware, Washington, Texas, Indiana, Nevada, New York, and even Nova Scotia, Canada. Prisoners outlined ten demands, including improved prison conditions, more funding for the implementation of rehabilitative programming, an end to life without parole sentences, and, most pertinent to the scope of this paper, the rescission of the PLRA so that inmates would be allowed "a proper channel to address grievances and violations of their rights" (“Prisoners Demand Reforms, Better Conditions...”) Given the hermetic nature of carceral systems in the US, grievance procedures prove invaluable in maintaining fairness within the hierarchical placement. The IWOC therefore argue that the PLRA's provisions seriously impede prisoners from securing a humane redress for their issues (Lopez 1).

Conversely, proponents of the PLRA argue that, whatever its perceived shortcomings, the Act demonstrates success in eliminating procedurally weak cases from the court docket. What's more, they call attention to the fundamentally litigious nature of inmates in general—as well as the fact that not all their complaints, however valid, merit the attention of the courts. The National Association of Attorneys General (NAAG), for instance, argues that PLRA is a safety valve that restores balance to the nature of prisoner litigation. Founded in 1907, the NAAG's mission is to foster state, federal and local engagement on legal issues. Their core values are dedication, integrity, collaboration, cooperation and inclusiveness. Since the PLRA's passage, they have steadily defended it as sensible mechanism to deter inmate-based judicial abuses. Indeed, in 2005, the NAAAG estimated that inmate civil rights litigation cost taxpayers over $81 million—and that most of the costs were incurred by insubstantial lawsuits (Newman 525-27; Shay & Johanna 300).

Whatever its empirical benefits or its administrative shortcomings, the fact remains that the PLRA is extremely complex in both its interpretation and application. For its supporters, it is a valuable tool for judicial sifting, staving off a deluge of baseless inmate suits. For its critics, it is a coercive instrument of civil rights abuses, enabling the authoritarianism of prison regimes. For the sake of brevity, not all the provisions of the PLRA will be examined in this paper. Relevant to our interests are section 42 U.S.C. § 1997e (a) of the Act, which details its administrative exhaustion requirement, and 28 U.S.C. § 1915(g), which deals with its "Three-strike" provision in appeals courts (Hobart 982-994). The Constitutional legitimacy, doctrinal coherence and administrative merits of these two sections have received extensive academic debate. However, rooted in each argument are the core values of justice and equality—as well as whether the Act delivers them, or renders them cruelly illusory. Prisoners constitute an invisible—and highly vulnerable—population bloc. Denied the bargaining power available to other segments of society, it therefore becomes critical to examine the PLRA from a lens of efficacy versus equilibrium.

Accordingly, it requires us to ask: Should the "Exhaustion" and "Three-strike" provisions of the PLRA be repealed? The aim of this paper is to answer this question through a careful examination of the PLRA's history, current legislative contentions and proposed remedies, parties to the controversy, and the arguments presented for and against the PLRA's two most tendentious provisions. This paper will seek to understand the core values of each side, the moral reasoning behind, and consequences of, their particular standpoint, before concluding with a potential solution for the matter at hand.

History

Prior to the 1960s, federal courts adopted a "hands-off" approach vis-à-vis prisons. Treated as regimes unto themselves, prison and jail inmates were deemed second-class citizens at best, non-entities at worst. Accordingly, their grievances were given little standing in the courts. Ruffin v. Commonwealth (1871) best exemplifies the federal bench's attitude toward prisoners. Referring to prisoners as "slaves of the State," the Supreme Court denounced their legal identities with the statement, "The bill of rights is a declaration of general principles to govern a society of freemen, and not of convicted felons" (Dubber 123; Wright 18). Accordingly, prison conditions and resultant complaints were left for individual correctional administrations to handle as they saw fit. While cases such as Ex Parte Hull (1941) and Coffin v. Reichard (1944) augured footings for inmate claims in courts, the corrections system remained, on the whole, a "shadow world" beyond judicial oversight (Schmalleger and Atkin-Plunk 102; O‘Lone v. Estate of Shabazz 354-55).

To be fair, this hands-off doctrine was based less on malicious indifference than on the fact that correctional institutions were freed from judicial interference under the separation of powers rationale. However, the opacity also lent itself to coercive penal policy, unchecked administrative abuses, and squalid living conditions within prisons (Blackburn et al. 246-249). By the 1960s, concomitant with the Civil Rights Movement, prisoners began agitating for improvements to their station. Backed by lawyers and civil liberties organizations, they sought to challenge what they deemed to be legal barriers to fairness and equality in courts, meaningful avenues of redress, and procedural and substantive rights. The following two decades would see the Supreme Court consistently vindicate prisoners' Constitutional rights (Hawkins and Alpert 11). Under 42 U.S.C. § 1983, it was declared: "Every person who, under color of any statute... subjects, or causes to be subjected, any citizen of the United States... to the deprivation of any rights, privileges, or immunities secured by the Constitution and laws, shall be liable to the party injured in an action at law, suit in equity, or other proper proceeding for redress" (Capistrano 1).

Landmark rulings such as Monroe v. Pape (1961) and Cooper v Pate (1964) heralded the era of due process rulings for state and federal prisoners (Muraskin 150). In defiance of a longstanding tradition of judicial detachment, courts assured petitioners easier legal access, religious freedom, medical treatment and protections from racial discrimination, going so far as to state "There is no iron curtain drawn between the Constitution and the prisoners of this country" (Waltman 74). This would mark the beginning of the "Open Door Policy" that characterized judicial attitudes towards prisoners, culminating in a 1970 speech by Chief Justice Warren Burger before the National Association of Attorneys General, which called for the implementation of prison grievance procedures (Coyle 52). Manifesting in the shape of 'administrative remedies', these were intended to combat the issue of besieged courts, without curbing inmates' access to them in the event of civil rights abuses. However, these rudimentary grievance mechanisms would prove inadequate. By the 1980s, Congress enacted the Civil Rights of Institutionalized Persons Act (CRIPA) as a sweeping overhaul of prison conditions. Particularly noteworthy was CRIPA's ability to award attorneys the power to remedy lawsuits related to "egregious or flagrant conditions" in prisons (Holt 15). At the same time, CRIPA also required prisoners to exhaust administrative alternatives before accessing federal courts. This was intended as a careful counterweight to the surge of inmate litigation that would inevitably reach the courts themselves (Edelman 233-245).

While CRIPA was well-intended, and served as a predecessive blueprint for prisoner litigation, the social narrative surrounding prisoner's rights was shifting. By the mid-1990s, the amount of filings in federal district courts had risen from 42,000 to 68,000, leading the New York Times to remark: "After three decades of startling growth, civil rights lawsuits brought by inmates protesting prison conditions in New York and elsewhere across the nation have become one of the largest categories of all Federal civil filings" (Dunn 1). This was not lauded as a sign of progress, but an impediment to proper judicial functioning. The nature of inmate claims was deemed irrelevant or merely petty: dealing with melted ice cream, lack of shampoo, and an inmate's right to put on a bra (Hudson 22). The NAAG compiled "Top Ten Inmate Lawsuits" lists, which included the now-notorious case of the inmate suing over chunky peanut butter (Wright and Pens 58). Media campaigns decrying the inanity of these suits soon cultivated a public contempt for prisoner-litigants as a whole. As the tough-on-crime weltanschauung sweeping Capitol Hill reached its zenith, many began questioning the effectiveness of CRIPA's grievance model, which did not seem to address the Constitutional violations in prisons so much as clog the court systems with unnecessary chaff (Reams and Manz 58-82).

In response, Congress drafted the PLRA, aiming to remedy the disorder in the federal courts. Senator Orrin Hatch and Senator Bob Dole, key sponsors of the bill, justified its proposal by citing the low success rate of prisoner suits, arguing that only an infinitesimal amount carried enough merit to be heard in court. Senator Dole, quoting Chief Justice Rehnquist's complaint that prisoners "litigate at the drop of a hat," went on to state, "The bottom line is that prisons should be prisons, not law firms" (U.S. Senate 1995). The NAAG praised this legislation as deliverance from a crippling workload; their Inmate Litigation Task Force wrote to Senater Dole, expressing a "strong support" for the PLRA as the solution to a burgeoning crisis (Sullivan 422). Conversely, prisoner advocates criticized the touting of absurd inmate claims as political subterfuge. Judge Newman of the Second Circuit, for instance, argued that the "poster child" cases mentioned by the PLRA's proponents were anomalies, and that prisoner's suits dealt with subject matter far graver in nature than critics suggested ("Free the Courts From Frivolous Prisoner Suits" 1). Similarly, Jon O. Newman, a federal appeals judge, stated that the anecdotes of frivolous litigation were either taken out of context, or "at best highly misleading and, sometimes, simply false" (521).

Current Policies

Whatever the case, the PLRA was passed in 1996, packaged as a rider to the appropriations bill—the Omnibus Consolidated Rescission and Appropriations Act of 1996. Designed to limit non-meritorious lawsuits by imposing a structural seal, the PLRA instituted multi-pronged requirements before inmate claims reached federal court. For one, it limited judicial intervention into carceral management, previously promulgated by consent decrees (court-ordered reforms imposed via settlements) unless the least "intrusive" means were implemented to correct the issue. Other provisions included the preclusion of inmates suing for mental or emotional suffering as opposed to physical injury; and the elimination of the traditional waiver of the filing fee (then $150) for indigent petitioners. In addition, the PLRA enabled courts to dismiss suits for frivolity/maliciousness/failure to state a claim, and expected them to have exhausted all administrative remedies before pursuing legal redress in court (Sercye 475-477).

The latter two provisions are most significant for our purposes. The first, Section 42 U.S.C. § 1997e (a), modeled itself on the armature laid out by CRIPA. Similar to its antecedent's exhaustion mandate, the PLRA does not allow prisoners to bypass administrative remedies before bringing lawsuits to federal court. However, whereas CRIPA allowed courts to decree the exhaustion of administrative mechanisms at their discretion—i.e. where they deemed it "appropriate and in the interests of justice" (Weiss 3)—the PLRA's exhaustion requirement is compulsory. The strict adherence to this provision was underscored in Booth v Churner (2001), where the petitioner argued against the exhaustion requirement when administrative remedies could not suffice for the nature of relief sought. However, in a unanimous opinion, the Supreme Court stated that regardless of the nature of the administrative remedies, the prisoner is required to go through the procedure of exhausting them. Justice Souter wrote for the Court, "we think that Congress has mandated exhaustion clearly enough, regardless of the relief offered through administrative procedures" (Booth v. Churner 1; Palmer 84)

A second vital component of the PLRA, Section 28 U.S.C. § 1915(g), is meant to impose consequences of prisoners who consistently bring frivolous lawsuits to court—the "frequent filers", so to speak (Peck). Firstly, it requires judges to dismiss an inmate petition sua sponte—"of one's own will," referring to a judge's order made without request by the parties in the case—if it is deemed to be "frivolous, malicious, fail[ing] to state a claim upon which relief can be granted, or seek[ing] monetary relief from a defendant who is immune from such relief." Dismissal for one of these four reasons will incur a "strike." A prisoner with three strikes becomes ineligible from claiming filing status in forma pauperis (IFP). This status was created by Congress to allow indigent citizens—prisoners included—to forgo the payment for filing fees on a temporary basis. A prisoner who has thrice had their claims dismissed on the basis of malice, frivolity, failure to state a claim, or monetary relief sought from those immune to the action, therefore risks losing access to the courts (Cordisco 2)

Since its passage, the PLRA has garnered both praise and contention alike, with circuit courts split concerning its financial utility and its doctrinal coherence. For its proponents, the PLRA's successes are both symbolic and substantive. Not only has Congress remedied the excess litigation swamping federal courts, but it has transformed the proverbial "deluge" into a dribble—dropping over 41,000 lawsuits to about 24,400, despite a concurrent 23% swelling of the prison population (Doran 1040-1041). For its critics, however, the PLRA has further exacerbated the "outsider" status of prisoners, overcomplicating grievance processes through what amounts to little better than "a sophisticated social control mechanism serving only bureaucratic interests" (Bordt and Musheno 7). What's more, they argue that prisoner litigants, already contending with barriers in the form of undersourced counsel and blockages to generic court access, must now navigate through an additional maze of rules.

Whatever its merits and demerits, the PLRA remains a monolithic statute, untouched by trends in judicial policymaking. Indeed, it can be argued that as the United States increasingly adopts the Foucauldian hallmarks of a carceral society, the PLRA proves instrumental in shaping the Constitutional rights of prisoners, as well as their demarcations and applications. On the flipside, in amassing the largest correctional system in the world, the PLRA proves pivotal in sieving out unnecessary caseloads, and in alleviating the expenses for federal courts. As such, it is essential to more closely examine the Act from the eyes of both its beneficiaries and its naysayers, in order to assess its consequences on current and future inmate litigation.

Stakeholders: The Proponents

To be sure, while the proponents and opponents of the PLRA appear to sit on diametrically opposite sides of the argument, their goals intersect in one critical sphere: introducing structural efficacy in prisoners' access to the civil justice system. Where they differ is in their characterization of the content that the prisoners bring to the courts: problematic frivolity on one side, deprivations of constitutional rights on the other. In understanding the values that each stakeholder adheres to, their stance becomes easier to comprehend, with their approach to the PLRA extending beyond self-interest to the particular belief systems that permeate the very policies they espouse. This proves critical when deconstructing the "Administrative Exhaustion" and "Three-strike" provisions of the Act, as it highlights attitudes not only toward carceral populations, but to the institutions that house them.

Proponents of the PLRA range from prison officials to judges to attorneys. For example, the National Association of Attorneys General (NAAG) continue to be energetic supporters of the PLRA. Founded in 1907, the Association serves as a conduit between attorneys general, enhancing their job performance and efficacy. It also functions as a liaison to the federal government in areas such as criminal law, appellate advocacy and consumer protection. As mentioned earlier, their core values include dedication, integrity, collaboration, cooperation and inclusiveness (“National Association of Attorneys General.") Having championed the PLRA from its embryonic stages to its maturation, they laud it as a success for its capacity to distinguish between wasteful inmate claims versus legitimate human rights violations. Indeed, they stress that the aim of the PLRA is not to impede inmate filings, but to curtail the ballooning—and often-absurd—nature of prison litigation trends (Royal v. Kautzky 1). In establishing the "Three-strike" and "Administrative Exhaustion" dyad, they argue that the Act's purview is to maintain procedural efficiency, economization, and above all, judicial detachment (Hudson 22-29).

As stated previously, the 1960s and 70s were a pivotal era for state prisoners, with the Supreme Court recognizing their right to bring in claims under Section 1983. This led to a wave of inmate-filed federal suits highlighting issues with confinement, many of which were successfully remedied. In the wake of meaningful court access, greater protections and wide berth for procedural due process, the "hands-off" approach previously favored by courts fell to the wayside; under the aforementioned "Open Door Policy" (Coyle 52), the number of state prisoner civil rights lawsuits increased by 227%, shooting up from 12,397 in 1980 to 40,569 in 1995 (Branham 541). However, in conjunction with the swelling litigation arose complaints that prisoners were filing claims that lacked substance, that were based on malicious agendas, and that were detracting the attention of federal judges away from worthier litigants. In Scher v. Purkett (1991), a District Judge noted in the memorandum that the courts were becoming "vexed... with malcontent inmates who fill their idle time, and the Court's precious time, by filing § 1983 complaints about the petty deprivations inherent in prison life" (1). Similarly, the Indiana Law Review, in an article assessing the burdens of the federal docket, noted that "Many prisoners are interested in using the courts to achieve ends other than the adjudication of meritorious claims. Prisoners use the judicial system to harass prison and judicial officials by pursuing cases to the full limits of the law" (445).

Prior to the PLRA's passage, courts utilized a wide range of discretionary methods to handle the workload generated by such inmate suits. However, there was no overarching consensus that produced a workable solution to the issue. This was further exacerbated by the fact that inmates, with an inchoate understanding of legal procedures, were sometimes unsure of whether to label a specific issue as a Constitutional violation or simply an administrative grievance. To be sure, prison can be a restrictive and unsavory environment. However, a restrictive and unsavory environment is, in itself, not grounds for launching a dispute. Cases such as Estelle v Gamble (1976) and Brown v. Plata (2011) sought to illustrate (in an arguably contradictory fashion) what constituted cause for state action duties versus what did not (Simon 276-280). However, these rulings were not enough to establish a uniform threshold. Furthermore, the broad—and some have argued, porous—provisions of CRIPA could not filter out the meaningful inmate claims from the greater bulk of insubstantial ones. Subsequently, certain inmates with legitimate civil rights grievances would find their claims superseded by their vindictive counterparts, who filed merely for "entertainment value" (Greifinger 38-39; Hanson and Daley 3).

To that end, proponents of the PLRA argue that its "Administrative Exhaustion" stipulation proves invaluable. It allows for a standard framework to guide the otherwise convoluted mechanisms employed by courts to weed out meritless claims. In an interview, Leonard Peck, a former attorney for the TDCJ, notes that the exhaustion procedure is in place for inmates to "pin themselves down to an issue, and evaluate what its facts are." Given that a majority of inmate grievances are service-based requests, the Act allows prison administrators and inmates to be in accord about the problem, and decide whether or not it warrants action from the courts. Sarah Hart further argues that this mechanism alerts corrections managers to "problems that need to be addressed and allow[s]them to resolve disputes before they turn into Federal lawsuits" ("Subcommittee on Crime, Terrorism and Homeland..." 5). This encourages both efficacy and cost-effectiveness; inmate grievances can be promptly addressed without consuming time and money on the court docket.

In a similar vein, the PLRA's "Three-strike" standard is argued to be a safeguard against unnecessary financial expenditure. Given that meritless lawsuits impair the courts' ability to address more valid claims (prisoner-based and otherwise), the provision sets a standard intended to discourage frequent-filer inmates from wasting the courts' time. The second half of the "Three-strike" diptych is its in forma pauperis provision. This limits indigent filing after a prisoner’s claims have been dismissed three times, in which event the prisoner must pay over one hundred dollars when they re-file their claim to the courts. Proponents of the PLRA argue that there is no case-law guaranteeing prisoners the Constitutional right to be excused from payment of filing fees. More to the point, they claim that the provision is not a draconian countermeasure intended to curtail inmate rights. If anything, it offers great leeway in the choices offered to inmates, as it i) does not outright bar lawsuits, ii) does not apply to state actions, and iii) does not apply to exigent circumstances where the prisoner is in imminent danger of bodily harm. Viewed this way, the PLRA seeks to keep administrative powers with the prisons themselves, as opposed to outside parties. The benefits to this approach are twofold. Firstly, it allows prisons to understand the issues unique to their particular institutions, and to tailor penal policies accordingly. Secondly, it augurs a return to the 'hands-off' doctrine, allowing prisons to maintain their own security and order without judicial micromanagement (Hudson 22-30; "Subcommittee on Crime, Terrorism and Homeland..." 14-16).

The latter proves especially significant in examining the proponents' stance, since judicial oversight in prisons has long been considered anathema. Before the PLRA, cases such as Harris v. Fleming (1988) saw federal courts increasingly assuming the role not of impartial arbiters but of "busybodies" concerned with the day-to-day functioning of correctional institutions (Robertson 187-188). The Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals went so far as to state that, "Judges are not wardens, but we must act as wardens to the limited extent that unconstitutional prison conditions force us to intervene..." (Johnson 53). This observation made clear a troubling philosophy of judicial overreach. It called into question the role of the federal judiciary, which was accused of succumbing to "Lochnerization"—i.e. invalidating democratically enacted laws in the name of due process (Lochner v. New York n.p.). While disguised as an ennobling motive, it did not sit well with the majoritarian paradigm which cleaves law from policy. As far back as the 1930s, Associate Justice Felix Frankfurter had made clear that "courts are not representative bodies. They are not designed to be a good reflection of a democratic society ...We are to set aside the judgment of those whose duty it is to legislate only if there is no reasonable basis for it..." (Abraham 94). With that in mind, deference to the administrative state was long defined as a guiding principle in courts; their policies were not to be second-guessed via judicial meddling.

Pursuant to this principle, the PLRA seeks to limit the circumstances in which courts may intercede in prison policy on the inmates' behalf—be it through injunctions or consent decrees. In the past, both were roundly criticized for placing tiresome restrictions on the governance of prisons. Correctional managers complained that such measures interfered with their ability to use "ingenuity and initiative" in resolving issues unique to their prisons (Sullivan 430). Similarly, correctional administrations decried it as a means of undermining carceral authority and emboldening prisoners to disobey their keepers. Cases such as Cullum v. California Dep't of Corrections (1962) warned that "if every time a guard were called upon to maintain order he had to consider his possible tort liabilities it might unduly limit his actions" (Branham 482); while Golub v. Krimsky (1960) supported that "to allow such actions would be prejudicial to the proper maintenance of discipline" (Goldfarb and Singer 365). With these demerits in mind, the PLRA's enactment seeks to reassert the supremacy of federalism as a governing principle—for courts and corrections alike.

Certainly, with the passage of the PLRA, courts have resumed deferring to prison administrators. In a potent reminder of the power of institutional context, no recent legislation has been introduced to either change or repeal the Act. Indeed, it has been argued that the PLRA is the carceral "Iron triangle" writ large: a ternary rubric of prison autonomy, cost containment, and effective procedural channels for inmates (Adlerstein 1681-1685). At the same time, it stirs heated arguments among scholars and stakeholders, for whom the PLRA embodies the grim normalization of punishment and control. Far from allowing legal processes and civil liberties to keep apace one another, it widens the gap between them in a cruel rubicon against inmate rights. These critics, gaining volume as the PLRA enters its adulthood, are restarting the conversation on prison conditions, and challenging the policymaking flaws of the Act as a whole. Their stances will be summarily examined in the next section.

Stakeholders: The Opponents

Critics of the PLRA consist of judges, attorneys, academics and human rights organizations. At the helm of recent calls to dismantle the Act are the Incarcerated Workers Organizing Committee (IWOC). Forming a coalition with Jailhouse Lawyers Speak—a network of prisoner rights advocates based out of South Carolina's Lee Correctional Institution—the IWOC have steadily worked towards improving the conditions of confinement within prisons, while also initiating large-scale dialogue and social awareness. The Committee strives to spark a "mass movement - inside and out - to abolish prison slavery." Their core values include emancipation, equal rights and community safety (Incarcerated Workers Organizing Committee 1). On August 21, 2018, commemorating the death of activist George Jackson of the Black Panther party, the IWOC rallied together with inmates across 17 prisons to stage a three-week strike protesting inhumane prison conditions. The strike was spurred in part by a riot in South Carolina's Lee Correctional Institution—one of the deadliest in the past two decades. According to reports, seven inmates were killed, and twenty-two required hospitalization. Prison guards and EMTs, rather than interceding in the violence, simply looked the other way (FITSNews "Inmate On Inmate..." 1). The incident, according to the IWOC, is emblematic of deteriorating prison conditions nationwide, while its sparse media coverage marks a strategic suppression campaign by the Department of Corrections to prevent inmate narratives from reaching the public's ears.

Following the strike, inmates outlined ten demands, including better living conditions, the expansion of rehabilitative programming, and, most significantly, the rescission of the PLRA (Corbitt 1). The IWOC bolstered these demands by pointing out that however "civilly dead" prisoners may be, they are not exempt from certain Constitutional rights (Dubber 123). Most relevant are those afforded by the Eighth Amendment, which states that they must have basic needs met during their confinement—such as adequate sanitation, ventilation and medical care (Herman 1242-1245). The IWOC therefore holds the PLRA responsible for the degeneration of prison conditions, as it impedes inmates' from challenging them. Rife with "loopholes," and financially "taxing", it renders few other viable conduit for redress apart from protests. A jailhouse lawyer, under the pseudonym 'George', complains that, “You have to go through all these different steps, all these different mechanisms. By the time you hit the court, a lot of times the issue is moot... So you’ve lost your lawsuit altogether, and it’s not because your lawsuit doesn’t have merit" (Sonenstein 1).