#and put the stories in context for the time period and literary landscape

Text

The BBC lady blowing my mind by pointing out the parallels between the endings of North and South and Jane Eyre (man brought low after losing his fortune, woman has gained wealth and comes to his rescue so they're now on equal footing).

She also pointed out that North and South is a continuation of issues Bronte explored in Shirley (to the point that Helstone is named after a character there), so I guess I may have to read that book one day.

#elizabeth gaskell#charlotte bronte#north and south#jane eyre#guess i may just have to give that book another chance#after my annoyance with people approaching gaskell as a lesser austen#instead of as her own writer#it's finally sunk in that maybe i need to do the same to these works#i still don't think they'll be to my taste#but maybe i could like and dislike what they are#instead of what they aren't#also i just need to say that the bbc lady restored my faith in literary criticism#reading the intros of some gaskell books lately just left me going 'shut up about gender!'#this lady talked about gender in ways that made sense#and put the stories in context for the time period and literary landscape#i didn't agree with everything but everything made sense coming from the text#instead of putting their own lens and twisting everything to fit it

71 notes

·

View notes

Text

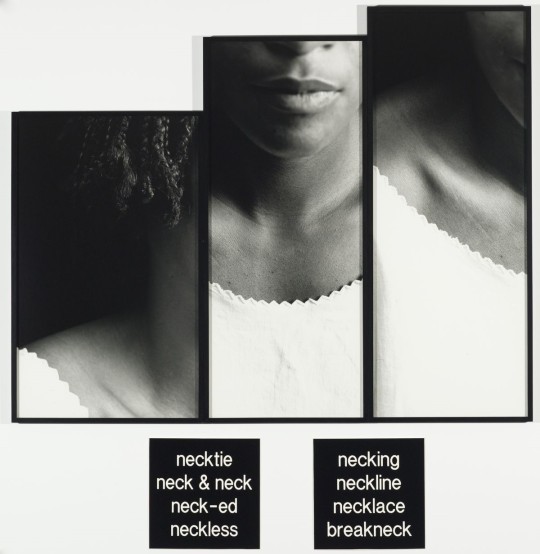

LORNA SIMPSON

Lorna Simpson, The Water Bearer (1986)

https://www.nytimes.com/2007/03/02/arts/design/02lorn.html

Lorna Simpson, Guarded Conditions (1989)

https://www.artspace.com/magazine/art_101/book_report/representing-the-black-body-lorna-simpson-in-conversation-with-thelma-golden-54624

Lorna Simpson, Necklines (1989)

https://mcachicago.org/Collection/Items/1989/Lorna-Simpson-Necklines-1989

Lorna Simpson Wigs (1994)

https://www.moma.org/learn/moma_learning/lorna-simpson-wigs-1994/

Childhood

Born in Brooklyn in 1960, Lorna Simpson was an only child to a Jamaican-Cuban father and an African American mother. Her parents were left-leaning intellectuals who immersed their daughter in group gatherings and cultural events from a young age. She attributed their influence as the sole reason she became an artist, writing, "From a young age, I was immersed in the arts. I had parents who loved living in New York and loved going to museums, and attending plays, dance performances, concerts... my artistic interests have everything to do with the fact that they took me everywhere ...."

Aspects of day-to-day life lit up Simpson's young imagination, from the jazz music of John Coltrane and Miles Davis, to magazine advertisements and overheard, hushed stories shared between adults; all of which would come to shape her future art. The artist took dance classes as a child and when she was around 11 years old, she took part in a theatrical performance at the Lincoln Center for which she donned a gold bodysuit and matching shoes. Though she remembered being incredibly self-conscious, it was a valuable learning experience, one that helped her realize she was better suited as an observer than a performer. This early coming-of-age experience was later documented in the artwork Momentum, (2010).

Simpson's creative training began as a teenager with a series of short art courses at the Art Institute of Chicago, where her grandmother lived. This was followed by attendance at New York's High School of Art and Design, which, she recalls "...introduced me to photography and graphic design."

Early Training and Work

After graduating from high school Simpson earned a place at New York's School of Visual Arts. She had initially hoped to train as a painter, but it soon became clear that her skills lay elsewhere, as she explained in an interview, "everybody (else) was so much better (at painting). I felt like, Oh God, I'm just slaving away at this." By contrast, she discovered a raw immediacy in photography, which "opened up a dialogue with the world."

When she was still a student Simpson took an internship with the Studio Museum in Harlem, which further expanded her way of thinking about the role of art in society. It was here that she first saw the work of Charles Abramson and Adrian Piper, as well as meeting the leading Conceptual artist David Hammons. Each of these artists explored their mixed racial heritage through art, encouraging Simpson to follow a similar path. Yet she is quick to point out how these artists were in a minority at the time, remembering, "When I was a student, the work of artists from varying cultural contexts was not as broad as it is now."

During her student years Simpson travelled throughout Europe and North Africa with her camera, making a series of photographs of street life inspired by the candid languages of Henri Cartier-Bresson and Roy DeCarava. But by graduation, Simpson felt she had already exhausted the documentary style. Taking a break from photography, she moved toward graphic design, producing for a travel company. Yet she remained connected to the underground art scene, mingling with likeminded spirits and fellow African Americans who felt the same rising frustrations as racism, poverty, and unemployment ran deep into the core of their communities.

At an event in New York Simpson met Carrie-Mae Weems, who was a fellow African American student at the University of California. Weems persuaded Simpson to make the move to California with her. "It was a rainy, icy New York evening," remembers Simpson, "and that sounded really good to me." After enrolling at the University of California's MFA program, Simpson found she was increasingly drawn towards a conceptual language, explaining how, "When I was in grad school, at University of California, San Diego, I focused more on performance and conceptually based art." Her earliest existing photographs of the time were made from models staged in a studio under which she put panels or excerpts of text lifted from newspapers or magazines, echoing the graphic approaches of Jenny Holzer and Martha Rosler. The words usually related to the inequalities surrounding the lives of Black Americans, particularly women. Including text immediately added a greater level of complexity to the images, while tying them to painfully difficult current events with a deftly subtle hand.

Mature Period

Simpson's tutors in California weren't convinced by her radical new slant on photography, but after moving back to New York in 1985, she found both a willing audience and a kinship with other artists who were gaining the confidence to speak out about wider cultural diversities and issues of marginalization. Simpson says, "If you are not Native American and your people haven't been here for centuries before the settlement of America, then those experiences have to be regarded as valuable, and we have to acknowledge each other."

Simpson had hit her stride by the late 1980s. Her distinctive, uncompromising ability to address racial inequalities through combinations of image and text had gained momentum and earned her a national following across the United States. She began using both her own photography and found, segregation-era images alongside passages of text that gave fair representation to her subjects. One of her most celebrated works was The Water Bearer, (1986), combining documentation of a young woman pouring water with the inscription: "She saw him disappear by the river. They asked her to tell what happened, only to discount her memory." Simpson deliberately challenged preconceived ideas about first appearances with the inclusion of texts like this one. The concept of personal memory is also one which has become a recurring theme in Simpson's practice, particularly in relation to so many who have struggled to be heard and understood. She observes, "... what one wants to voice in terms of memory doesn't always get acknowledged."

In the 1990s Simpson was one of the first African American women to be included in the Venice Biennale. It was a career-defining decade for Simpson as her status grew to new heights, including a solo exhibition at New York's Museum of Modern Art in 1990 and a series of international residencies and displays. She met and married the artist James Casebere not long after, and their daughter Zora was born in the same decade. In 1994 Simpson began working with her grandmother's old copies of 1950s magazines including Ebony and Jet, aimed at the African American community. Cutting apart these relics from another era allowed Simpson to revise and reinvent the prescribed ideals being pushed onto Black women of the time, as seen in the lithograph series Wigs (1994). The use of tableaus and repetition also became a defining feature of her work, alongside cropped body parts to emphasize the historical objectification of Black bodies.

Current Work

In more recent years Simpson has embraced a much wider pool of materials including film and performance. Her large-scale video installations such as Cloudscape (2004) and Momentum (2011) have taken on an ethereal quality, addressing themes around memory and representation with oblique yet haunting references to the past through music, staging, and lighting.

Between 2011 and 2017 Simpson reworked her Ebony and Jet collages of the 1990s by adding swirls of candy-hued, watercolour hair as a further form of liberation. She has also re-embraced painting through wild, inhospitable landscapes sometimes combined with figurative elements. The images hearken to the continual chilling racial divisions in American culture. As she explains, "American politics have, in my opinion, reverted back to a caste that none of us want to return to..."

Today, Simpson remains in her hometown of Brooklyn, New York, where in March 2020, she began a series of collages following the rise of the Covid-19 crisis. The works express a more intimate response to wider political concerns. She explains, "I'm just using my collages as a way of letting my subconscious do its thing - basically giving my imagination a quiet and peaceful space in which to flourish. Some of the pieces are really an expression of longing, like Walk with Me, (2020) which reflects that incredibly powerful desire to be with friends right now."

Despite her status as a towering figure of American art, Simpson still feels surprised by the level of her own success, particularly when she compares her work to those of her contemporaries. "I feel there are so many people - other artists who were around when I was in my twenties - who I really loved and appreciated, and who deserve the same attention and opportunity, like Howardena Pindell or Adrian Piper."

The Legacy of Lorna Simpson

Simpson's interrogation of race and gender issues with a minimal, sophisticated interplay between art and language has made her a much respected and influential figure within the realms of visual culture. American artist Glenn Ligon is a contemporary of Simpson's whose work similarly utilizes a visual relationship with text, which he calls 'intertextuality,' exploring how stencilled letters spelling out literary fragments, jokes or quotations relating to African-American culture can lead us to re-evaluate pre-conceived ideas from the past. Ligon was one of the founders of the term "Post-Blackness," formed with curator and writer Thelma Golden in the late 1990s, referring to a post-civil rights generation of African-American artists who wanted their art to not just be defined in terms of race alone. In the term Post-Black, they hoped to find "the liberating value in tossing off the immense burden of race-wide representation, the idea that everything they do must speak to or for or about the entire race."

The re-contextualization of historical inaccuracies in both Simpson and Ligon's practice is further echoed in the fearless, cut-out silhouettes of American artist Kara Walker, who walks headlong into some of the most challenging territory from American history. Arranging figures into theatrical narrative displays, she retells horrific stories from the colonial era with grossly exaggerated caricatures that force viewers into deeply uncomfortable territory.

In contrast, contemporary American artist Ellen Gallagher has tapped into the appropriation and repetition of Simpson's visual art, particularly her collages taken from African American magazine culture. Gallagher similarly lifts original source matter from vintage magazines including Ebony, Our World and Sepia, cutting apart and transforming found imagery with a range of unusual materials including plasticine and gold-leaf. Covering or masking areas of her figures' faces and hairstyles highlights the complexities of race in today's culture, which Gallagher deliberately teases out with materials relating to "mutability and shifting," emphasising the rich diversity of today's multicultural societies around the world.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

greenwitchpinkcrystals replied to your post “It turns out that every time I see “Danu” listed as an “Earth...”

Why

So, first off, let’s get this out of the way: This is not meant to affect ANYONE’S religious or spiritual practices. If you have a relationship with any of the Tuatha dé that doesn’t fit a given analysis, I’m not going to be the one who says “No, that’s wrong.” That’s YOUR relationship and your belief system, and I’m not going to touch that. That is NOT my place.

What I’m talking about is purely on an academic level, reading the original medieval texts, and I will say that what I’m about to say, while I think it LEANS towards what I believe the academic consensus is, is not holy writ either. I fully admit that, if it came down to assigning myself to EITHER anti-nativist or nativist, I would probably class myself in with the anti-nativists, AKA The Party Poopers of Celtic Studies, as you’re probably going to find out soon.

On a more simplified level, there are three figures from Irish Mythology who I do NOT like discussing simply because they tend to elicit very strong reactions from people when Commonly Accepted Truths are questioned: Bríg, the Morrigan, and Danu. All three of them tend to activate my fight or flight response when they’re brought up (and, most of the time, my option of choice is FLIGHT.)

Point 1 (AKA “In Which Rachel Rants About 99% Of The Over-Generalizations of the Tuatha dé Into a Given Function”)

it’s nearly impossible to concretely assign almost ANY of the Tuatha dé to a function. They aren’t really...a PANTHEON like that, if you look at the texts. They’re an ever-shifting cast of figures loosely tied together by a sprawling body of texts, poems, and genealogies who, while they MIGHT have had a pre-Christian past, are being primarily used as literary figures. And it’s nigh impossible to tell where the one begins and the other ends, especially since the Tuatha dé SHIFT depending on the text (and sometimes even in the same text!)

One of my favorite examples is Lugh. Generally regarded as one of the best figures of the Tuatha dé, the hero of Cath Maige Tuired, master of all skills. A GOOD GUY, right? Except...in Sons of Tuireann, he brutally manipulates the deaths of three men simply because he decided that he wanted to have his cake and eat it too. And in the Dindsenchas poem Carn Ui Neit, where he kills Bres. And in How the Dagda Got His Magical Staff, where he kills Cermait for sleeping with his wife. And the main text where he’s a Shining Hero, Cath Maige Tuired, is generally accepted by scholars these days (most notably John Carey and Mark Williams) agree that the text primarily comes out of a 9th century context and is meant to be basically a bolster for the literary elite in light of the Viking invasions (the Fomorians come from Lochlann “Land of Lakes,” which can either mean “Norway” or “Norse occupied Scotland” in a medieval Irish context). It’s not that Lugh is NOT a pre-Christian figure, because the figure Lugus with Gaul is...pretty indicative that there’s SOMETHING, but we have no idea WHAT. And, really as far as the Tuatha dé are concerned, there are probably...less than five figures I would SOLIDLY say we have any evidence for worship for and an idea of where they MAY have fit. Give or take one or two depending how I’m feeling on a given day. (Obviously, some people, even on the more skeptical side of things, can be more or less generous than me; I’m just a naturally very suspicious person. The ‘less than ten’ thing should not be taken as any indication of a consensus here.)

Basically, they couldn’t even agree on how these guys were supposed to behave, much less give them a FUNCTION. Their powers, what and who they’re associated with, etc. all is variable, and it’s impossible to tell which figures were genuine pre-Christian figures and which ones were literary figures who were invented to serve the purposes of the time. (Also, there are some figures who are highly associated with the literary elite but who...don’t pop up in any of the folktales that adapt the same stories, which leads me to suspect that their MAIN association was with the literary elite and they didn’t have any real influence out of that. See: Bres. I WANT my special boy to have been a Big Figure who was worshipped and respected, but the evidence, to ME at least, strongly suggests that he was a figure strongly associated with the literary elite who was tacked on as a villain to Cath Maige Tuired.)

So, my tl;dr here is that, really, it’s hard to assign a “mother goddess” or “Fertility goddess” to the Tuatha dé because, simply put, there is no way to assign that kind of specific function to almost ANY of the figures of the Tuatha dé. How they’re depicted really depends more on what the individual scribe wanted to convey rather than consistently associating them with ONE thing, and even in cases like Cormac’s Glossary, which DOES give a FEW of them functions, it’s....shaky at times, as we’re about to deal with. There are figures who ARE mothers, but it’s hard to really say that they’re...THAT associated with it. Generally speaking, the designation seems to be given to female figures in the text mainly because...they couldn’t think of anything else to apply to women? Ditto for “Fertility”. (See: Bríg. There is no reason to assume that Bríg had ANY association with fertility, and yet it’s a claim I see regularly trotted out.)

Point 2 (AKA “Okay, but what about DANU? Who IS said to be ‘Mother of the Gods?’”):

Even by the usually-shaky standards of Irish Mythological continuity, (D)anand (not Danu in any of the medieval texts) is...strange, as far as her background. Not in a “There are like ten layers of literary stuff lightly sautéed on top of a Pre-Christian background” way, but in a, “Holy Shit, they REALLY created a goddess out of nothing, didn’t they?” way. The tl;dr is that, INITIALLY the Tuatha dé Danann were...the Tuatha dé. Just “Tuatha dé.” Which translates out very, very roughly to “God-Tribe.” Which WORKED but also, unfortunately, was the same term used for the Israelites in the Bible, which caused Confusion understandably.

And, well. I’m going to let Mark Williams explain the rest, since he’s the man with the PhD (Also, if you have ANY interest in how our current conceptions of the Tuatha dé have been formed, I HIGHLY recommend this book. It’s a VERY solid, accessible book that doesn’t bog itself in academic jargon and instead tries to create something that can be read and enjoyed by anyone, and unlike me, he’s very open as far as the possibilities):

This tangle indicates two things: first, the origins and developments of the mysterious Donand are not fully recoverable, and secondly the idea that Irish paganism knew a divine matriarch named Danu cannot now be maintained. The compilers of ‘Cormac’s Glossary’ may have been quite correct that there had once been a goddess called Anu or Ana associated with the Paps mountains, since it beggars belief to think that the pre-Christian Irish would not have associated so impressively breasted a landscape with a female deity. On the other hand it is suspicious that so important a figure as the glossary’s ‘mother of the Irish gods’ should go unmentioned in the early sagas, teeming as they are with former gods and goddesses. This raises the possibility that Ana/Anu may have simply been a local Munster figure, less familiar or even unknown elsewhere in Ireland.

Michael Clarke foes further, and suggests that the lofty description of Anu/Anu in ‘Cormac’s Glossary’ may itself owe more to medieval learning than to pagan religion, and result from a monastic scholar musing learnedly on the goddess Cybele, mother of the classical gods...He also quotes Isidore, Irish scholars’ favourite source for the learning of Mediterranean antiquity, who describes Cybele in striking terms: “They imagine the same one as both Earth and Great Mother...She is called Mother, because she gives birth to many things. Great, because she generates food; Kindly, because she nourishes all living things through her fruits.”

This, as Clarke notes, is so close to the Irish glossary entry that it is hard to avoid the suspicion that the ‘personality’ of the goddess Ana-’who used to feed the gods well’-has been cooked up in imitation of the classical deity. That Clarke’s analysis may be right is suggested by a distinctive oddity in the ‘Ana’ entry: While traces of the activities of divine beings are constantly detected in the landscape in Irish tradition, nowhere else is a natural feature described as part of a divinity’s body. This is rare even for the better-attested gods of classical tradition, with the signal exception of the great mother-goddesses of the eastern Mediterranean, of whom Cycle, the ‘Mountain Mother’, came to be the most prominent. Ana/Anu is simply not on the same scale or plane of representation as síd beings like Midir or Óengus, and it is telling that the Paps of Ana were imagined (by the early thirteenth century at the latest) as a pair of síd-mounds, the separate and unconnected dwellings of different otherworldly rulers.

(Ireland’s Immortals, pg. 189-190)

So, just as much as it’s hard to assign a function to MOST of the Tuatha dé, it’s even harder to really....SAY whether Ana actually existed prior to a certain period of time. She definitely wasn’t called “Danu;” that form of her name is never used at that point.

Was there a figure who was “Mother to the Gods?” I don’t know. Maybe there was! Maybe she was the Great Mother Goddess of the pre-Christian Irish! I’m not going to claim to KNOW one way or another until we invent time machines and I can properly go back in time to shake an answer out of Cormac in person. But it’s impossible to know and the evidence is scant at best, definitely not worthy of the press she gets. I wish I could tell you. I really do, even if the answer was something that I personally wouldn’t like. But then, we wouldn’t have a field, either.

#greenwitchpinkcrystals#long post#irish mythology#i tried to make this as short and succinct as possible and i still failed#whoops#danu#celtic mythology

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Writing a historical novel #6 – research is intimidating (but has to be done) pt 4 of 4 – breakthrough

(image: ’Black Angels’ by George Barnard)

For the past ten years I have been working on a historical novel, Drapetomania, Or, The Narrative of Cyrus Tyler and Abednego Tyler, lovers, set in slavery times in the American Deep South, and telling of the passionate love between two men, Cyrus and Abednego, and their bid for freedom from bondage – out now! As I worked on a final edit of the 183,000 word manuscript, I began reflecting on the process. These are some of my thoughts.

Plowing through 1700pp of slavery narratives, alongside historical accounts, contextualizing information and contemporary fictions (including, belatedly, Huckleberry Finn, which I realised I had never read, and is, it turns out, a post civil war tale of pre-war slavery times and thus a curious, paradoxical exercise in recent nostalgia), was ultimately liberating, and in several ways, some obvious, some less so.

The most basic change was simply this: I had moved from knowing nothing (much) to knowing a great deal about historical representations of slavery experiences and the context in which they arose. Funny how one can internalize ‘not knowing’ as an identity, but I realised that for half a decade I had done so.

While modern history is extremely useful in framing the past, there’s nothing like reading contemporary material to give you a feel for the idiom, for the aesthetic and therefore mental landscape of a period; and allowing some sense of that to enter your writing fairly much automatically creates an authenticity of tone without a need to overdo quaint dialogue or overwork period terms or references (which is very tempting): sometimes a mule cart can just be a mule cart and need not be a barouche or phaeton, and so on.

Behind that commonsense evocation of another time is an interesting – and in its way somewhat liberating – philosophical point: what makes a historical novel feel real to any (non-academic) reader is how far it seems to embody the tone and timbre of novels that were written at the time in which it is set. Yet those novels – that is, those fictions – were and are themselves cultural constructs, informed by the personalities and perceptions, quirks and kinks of their authors, as well as by what was generally permitted at their time of writing. Did real people ever talk as Dickens’ characters talk? Or Jane Austen’s? Probably not. Or maybe yes, kind of. Did they also say shit or cunt? We can’t penetrate very far beyond that essentially literary limit of possible knowledge – we literally cannot know, as there are no other records of direct speech, (beyond court testimonials, themselves generally ‘written up’ by officials who sometimes added literary flourishes of their own, and would have at the least redacted swearing and blasphemy), how people really spoke back then – and so (I believe) the modern writer is free to permit him/herself to improvise around general impressions without being too weighed down by forensic fears about historical accuracy of register once obvious anachronisms have been tidied away.

A further level of literary reflexivity arises in consideration of slave narratives, which, being as they tend to be billed as ‘the true account of’, it’s natural for us to approach initially as if they are simple primary sources. This is to ignore the attention those who escaped slavery paid to ensuring that their autobiographies conformed both to the existing novelistic conventions of the time, and (soon enough) to the evolving (oftentimes best-selling) new genre of The Slave Narrative itself. So these historical artifacts are not simply ‘true’ – they too are literary constructs; and indeed, reading them I was struck by how often they cleaved to conventions of romance novels such as Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre – this is perhaps most strongly evident in the narrative of Harriet Jacobs (Linda Brent), one of the few women to write her story (& she was proprietorial about it too). Ironically, to a modern reader, the flourishes – the ‘Picture if you can, dear reader’ asides – that would have drawn in a nineteenth century reader are somewhat off-putting nowadays: we hope for the unvarnished truth of experience, or a truth that seems unvarnished, anyway.

Helpfully for the fiction writer, the narratives reveal that slaves endured wildly differing conditions synchronically as well as diachronically, and that plantations differed hugely in how they were run, what those enslaved could hope to get away with, what freedoms were allowed or curtailed in terms of movement, what punishments imposed; even such grimly basic matters as whether shoes were available. So as a non-academic I could write my story without too much anxiety that I was failing to capture some single, singular, detailedly true and therefore authentic monolithic account of things only accessible to scholars. There were many experiences, and those we have are only those recorded: other experiences were possible.

Another point to note as far as using slavery narratives as a resource is that the published tales – some ‘as told to’ and therefore mediated to unknown extents by their white amanuenses – were intended to be read by a white audience. Therefore there is behind them of necessity a hidden, largely unspoken version that just occasionally breaks the waterline: the account that might have been written for a black readership, had such a thing then been imaginable. This sense of things unsaid, of things left out, was liberating to me from the point of view of presuming to create a fictional tale: the realization that there was something beyond a greater level of explicitness about the facts of life that might legitimately be added to both historical records and autobiographical writing, something beyond my simple initial impulse to realistically render passionate same-sex love in such a time and place.

While the slave narratives are moving, disturbing and full of insights, they often lack contextualizing detail for the modern reader of 150-200 years later. Writing about my own life now I might say something today like, ‘I topped up my Oyster and got the tube to town’ – perfectly comprehensible to any reader in C21st London. However, in 200 years’ time every element of that statement might be wholly obscure, (‘perhaps he means he ate a heavy meal of shellfish before setting out?’) and it’s certainly lacking in evocative detail – use of money or a payment card, yellow disc on ticket machine, automatic barriers, escalators, sliding doors of carriages, name of tube line etcetera. All this kind of information tends to be absent from primary sources, the more so as their intent was campaigning and therefore contemporary in focus.

Unexpectedly liberating in this regard was the British abolitionist MP J.S. Buckingham’s 1839 Journey through the Southern Slave States. While in many ways a dry read, precisely because he was a tourist (& one critical of slavery, which the British had finally abolished in 1833, to white southern consternation) Buckingham records many details a local would omit, including potted summaries of the economic workings of many of the towns and villages and estates he passed through; competition and lack of competition in stagecoach lines; quality of rooms and food in inns and so on. This – finally – gave me greater confidence in sending my protagonist out into a wider world beyond the plantation’s bounds.

As settings fell into place, the internet was invaluable as an adjunct, of course. What type of pistols were used in 1850; what carriages ridden in; what hats worn? One academic website has assembled advertisements for runaway slaves decade by decade, and you can study the way the phrasing altered over time, and the amounts offered for recapture; and so, without ever stating the year, (because ultimately I felt it would never mean anything to my protagonists), I could embed the tale ever more densely in its period.

All this meant that Cyrus could now leave the wilderness into which he had first run, into which he had been pursued by dogs, and from which he had emerged following a sort of psychic rebirth, and find himself once more among people. And so a break in the writing that lasted nearly five years was ended, and I accelerated forwards.

Buy Drapetomania here (US) & here (UK)

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Discover Michelle Porte’s movie about the French author Annie Ernaux

In 2019, I discovered a French documentary about the author Annie Ernaux created by Michelle Porte, which came out in 2013: Les mots comme des pierres. Annie Ernaux, écrivain. Michelle Porte is a French director, scriptwriter and documentary maker who has created numerous documentaries since the seventies. In 2011, two years after the publication of Les Années, the director encourages Annie Ernaux to narrate and open up about places, stories and events which have made an impact on her life. The aim is to understand and grasp her literary work, as well as reflecting upon writing, particularly when it’s autobiographical.

Annie Ernaux was born in 1940 and is one of the principal authors of our time since 1974, when she published her first novel Les Armoires vides. She is seen as a sociological writer, addressing intimacy, love experiences, social determinism, and the difficulty of personal development and growth through separation from our roots.

From home to school, the past materialized in places of memory

During 52 minutes, the camera puts us into the author’s private life, highlights the different places which have made her life, starting with this house “which protects” in Cergy, where she has lived for thirty years. But the previous ones are not less important, from family house to school, from Lillebonne to Yvetot, we are invited to discover her childhood landscapes, those she has never forgotten. However, retracing the traces of her past is not always an easy experience, according to Annie Ernaux we would need to "be satisfied with memory, that is where it is".

Thus, this documentary is about the young girl she used to be, the adult she has become, it’s also about her mother, feminist before the word, a woman who could behave “like a man”. Annie Ernaux says about her: "I undoubtedly made myself both for her and against her".

Writing as a necessity

The author also evokes the child she was, impatient to go to school and learn to read, then upset when she learns from her mother, at the age of 10, the existence of an older sister who died a year before her birth (L’autre fille, Nil, 2011). There will also be the adolescence and the growth of desire, the hope of love, the first emotions, and the rejection of authority. She also confides on the context of writing her first novel: “a period of very great suffering”, which make Les Armoires vides a life-saving story, a way to forget her feeling of “carrying suitcases of dirty clothes”.

But how is it to write about her own life? Annie Ernaux defines her writing as "material", it’s like "writing with a knife". She expresses herself in a precise, refined, sharp writing style which makes it universal, a writing coming from the depths, which carries within it something heavy, violent and real. She writes “to take words out like stones from the bottom of a well or a river”.

Thus, Michelle Porte signs here a very beautiful film, sensitive and moving which manages to put into image the words and the silences of Annie Ernaux. This collaboration is the fruit of the same quest: an intimate one, which allowed the publication of the book Le vrai lieu. Entretiens avec Michelle Porte, published by Gallimard in 2014.

It is unfortunately difficult to view Michelle Porte's work anywhere other than at festivals or within the scope of special screenings. For those interested, stay tuned for upcoming programs because this documentary is not available on the Internet and does not exist on DVD.

0 notes

Text

Christening with Celluloid

My husband does this thing whenever we move: we don’t rest until almost everything is unpacked and put away. We usually put our space together within 24 hours of arriving in a new home. As someone who is an absolute pig, this stresses me out in the short term. (In the long term, I think he’s a genius who knows that a clean space equals a peaceful mind.) By the time we haul our movies and books and furniture into our abode, I desperately need to unwind. The last two moves we’ve made (from Sioux City to LA and back to Sioux City), I did this by watching a movie. And each movie set the tone for my aesthetic, my expectations, and my journey in that home.

Upon arrival in Glendale, a San Fernando Valley suburb located literal blocks from Los Angeles proper, I settled down in my husband’s “gaming” chair and watched my Criterion BBS Story copy of the New Hollywood classic, Easy Rider. Not a new-to-me viewing, as I saw the movie before on the big screen thanks to the now defunct Film Train series at Sioux City’s cheap seats, the Riviera. (To whoever ran the Film Train: please bring it back, I promise I’ll attend more regularly, we took you for granted and I’m sorry!) The story resonated with me, not because I related to the two free-wheelin’, drug-dealin’ motorcyclists making their way to New Orleans, but because I had recently become acquainted with the diverse scenery of the United States.

The year before moving to LA, I visited the paternal side of my family’s home in New Orleans and my mom’s cherished white beaches of Pensacola. I spent days traveling between Iowa and California, driving through the American West for the first time, and I fell in love with the land in a way I didn’t know possible. Canyons and mountains and deserts and water, I experienced all the landscapes our beautiful country has to offer those lucky enough to travel it.

During my time in (and leading up to) Los Angeles, I grew more entranced by the Californian pop art of Ed Ruscha. I felt a sense of longing for the architectural institutions of the West (gas stations, the Hollywood sign, swimming pools). I also listened to Lana Del Rey non-stop, driving along the PCH and pretending the roads weren’t packed bumper-to-bumper, like in the days when Jane Fonda and Roger Vadim threw epic parties in Malibu, and further back still, when Salka Viertel hosted literary salons in Santa Monica. Something about Easy Rider also captured that bittersweet emotion of longing for the past of the West. (Though the film’s bikers’ violent end brings me back down to earth and ugly realities.)

I started my LA experience with an outdated perspective of California, a perspective built around the desert and Joni Mitchell and independent films directed by Dennis Hopper. I learned quickly from my short time there that my beloved vision of California exists on celluloid and in my heart, but the real city of Los Angeles thrives on industry types and naive people like me, desperate for stardust and working away for minimum wage, just for the luxury of living in the footsteps of the past. The world of Easy Rider can’t be found in the cities, but on the roads that lead to them.

Once I returned with my husband to Iowa, in order to start our beautiful family with a strong support system, we did what I’ve now grown accustomed to: we moved all of our stuff into the house and unpacked it within a single day. And once we had our living room reasonably arranged , we ordered pizza and I ran to RedBox to pick up a title praised out of Sundance but shunned by audiences during its theatrical run: Patti Cake$.

Danielle Macdonald went on the star in the Netflix original Dumplin’, but she gave her first crowd-pleasing, hype-generating performance as an aspiring rapper from New Jersey in Patti Cake$. I don’t know what Sony Pictures Classics did to mess up this release, but as far as I can tell, no one outside of film-centric circles even heard about this movie pre-release. Which is ridiculous, because Patti Cake$ isn’t arthouse or slow-paced or anything difficult to sell to the masses. It’s fun and also brought me to joyful tears by the end. (I still have a hard time listening to “Tuff Love (Finale)” without tearing up at the memory of Bridgett Everett’s character’s reaction to hearing the song.)

The movie focuses our sympathies on Patti’s longing for the glamor and success represented by the lights of the big city, just across the water from her hometown in Dirty Jersey. (Her choice of descriptor, not mine. I have nothing against Jersey.) She falls for and collaborates with the noise metal performance artist Basterd (a charming performance from Mamoudou Athie of Brie Larson’s directorial debut Unicorn Store) and makes killer beats with her lovable bandmate, Jheri (Siddharth Dhananjay). I still listen to the fire soundtrack; the songs hold up outside of the film’s context.

Every actor onscreen brings their A-game, but none as much as New York’s living legend and cabaret artist, Bridget Everett, as Patti’s bitter mother, Barb. In her youth, Barb sang with a hair metal band and had the pipes to make it big. (I haven’t seen the movie in a couple years now, so I don’t remember why she didn’t.) Her past emotional injuries keep her from supporting Patti in her dream of making a living in the music industry. Everett turns in a heartbreaking performance, so even when Barb says nasty things to Patti, like “act your race [white],” we still don’t hate her for it, because we understand she’s coming from a place of deep hurt and projecting that onto her daughter.

Patti Cake$ helped me usher in a new era of my life, an era of self-discovery and self-improvement. I see a lot of myself in Patti, like most audience members probably do, longing for city lights and big dreams. My story doesn’t end like hers. In fact, I don’t consider myself having reached an ending at all. I admire the passion and creativity she puts into her art. I hope to carry that flame from the screen and into my real life. Since moving back to my hometown, I’ve achieved things I never thought possible for me: I’ve written scripts and stories and put my words out into the world, I’ve turned in performances of roles I never dreamed of playing, I achieved more at my day job than I thought possible. While I could allow myself to wallow and feel stuck in this relatively small city, I’m going to follow Patti’s lead and make the art I want.

What movies have you christened homes with? How do they reflect on that period of your life, if at all?

0 notes

Text

Pop Picks – September 7, 2018

What I’m listening to:

With a cover pointing back to the Beastie Boys’ 1986 Licensed to Ill, Eminem’s quietly released Kamikaze is not my usual taste, but I’ve always admired him for his “all out there” willingness to be personal, to call people out, and his sheer genius with language. I thought Daveed Diggs could rap fast, but Eminem is supersonic at moments, and still finds room for melody. Love that he includes Joyner Lucas, whose “I’m Not Racist” gets added to the growing list of simply amazing music videos commenting on race in America. There are endless reasons why I am the least likely Eminem fan, but when no one is around to make fun of me, I’ll put it on again.

What I’m reading:

Lesley Blume’s Everyone Behaves Badly, which is the story behind Hemingway’s The Sun Also Rises and his time in 1920s Paris (oh, what a time – see Midnight in Paris if you haven’t already). Of course, Blume disabuses my romantic ideas of that time and place and everyone is sort of (or profoundly so) a jerk, especially…no spoiler here…Hemingway. That said, it is a compelling read and coming off the Henry James inspired prose of Mrs. Osmond, it made me appreciate more how groundbreaking was Hemingway’s modern prose style. Like his contemporary Picasso, he reinvented the art and it can be easy to forget, these decades later, how profound was the change and its impact. And it has bullfights.

What I’m watching:

Chloé Zhao’s The Rider is just exceptional. It’s filmed on the Pine Ridge Reservation, which provides a stunning landscape, and it feels like a classic western reinvented for our times. The main characters are played by the real-life people who inspired this narrative (but feels like a documentary) film. Brady Jandreau, playing himself really, owns the screen. It’s about manhood, honor codes, loss, and resilience – rendered in sensitive, nuanced, and heartfelt ways. It feels like it could be about large swaths of America today. Really powerful.

Archive

August 16, 2018

What I’m listening to:

In my Spotify Daily Mix was Percy Sledge’s When A Man Loves A Woman, one of the world’s greatest love songs. Go online and read the story of how the song was discovered and recorded. There are competing accounts, but Sledge said he improvised it after a bad breakup. It has that kind of aching spontaneity. It is another hit from Muscle Shoals, Alabama, one of the GREAT music hotbeds, along with Detroit, Nashville, and Memphis. Our February Board meeting is in Alabama and I may finally have to do the pilgrimage road trip to Muscle Shoals and then Memphis, dropping in for Sunday services at the church where Rev. Al Green still preaches and sings. If the music is all like this, I will be saved.

What I’m reading:

John Banville’s Mrs. Osmond, his homage to literary idol Henry James and an imagined sequel to James’ 1881 masterpiece Portrait of a Lady. Go online and read the first paragraph of Chapter 25. He is…profoundly good. Makes me want to never write again, since anything I attempt will feel like some other, lowly activity in comparison to his mastery of language, image, syntax. This is slow reading, every sentence to be savored.

What I’m watching:

I’ve always respected Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, but we just watched the documentary RGB. It is over-the-top great and she is now one of my heroes. A superwoman in many ways and the documentary is really well done. There are lots of scenes of her speaking to crowds and the way young women, especially law students, look at her is touching. And you can’t help but fall in love with her now late husband Marty. See this movie and be reminded of how important is the Law.

July 23, 2018

What I’m listening to:

Spotify’s Summer Acoustic playlist has been on repeat quite a lot. What a fun way to listen to artists new to me, including The Paper Kites, Hollow Coves, and Fleet Foxes, as well as old favorites like Leon Bridges and Jose Gonzalez. Pretty chill when dialing back to a summer pace, dining on the screen porch or reading a book.

What I’m reading:

Bryan Stevenson’s Just Mercy. Founder of the Equal Justice Initiative, Stevenson tells of the racial injustice (and the war on the poor our judicial system perpetuates as well) that he discovered as a young graduate from Harvard Law School and his fight to address it. It is in turn heartbreaking, enraging, and inspiring. It is also about mercy and empathy and justice that reads like a novel. Brilliant.

What I’m watching:

Fauda. We watched season one of this Israeli thriller. It was much discussed in Israel because while it focuses on an ex-special agent who comes out of retirement to track down a Palestinian terrorist, it was willing to reveal the complexity, richness, and emotions of Palestinian lives. And the occasional brutality of the Israelis. Pretty controversial stuff in Israel. Lior Raz plays Doron, the main character, and is compelling and tough and often hard to like. He’s a mess. As is the world in which he has to operate. We really liked it, and also felt guilty because while it may have been brave in its treatment of Palestinians within the Israeli context, it falls back into some tired tropes and ultimately falls short on this front.

June 11, 2018

What I’m listening to:

Like everyone else, I’m listening to Pusha T drop the mic on Drake. Okay, not really, but do I get some points for even knowing that? We all walk around with songs that immediately bring us back to a time or a place. Songs are time machines. We are coming up on Father’s Day. My own dad passed away on Father’s Day back in 1994 and I remembering dutifully getting through the wake and funeral and being strong throughout. Then, sitting alone in our kitchen, Don Henley’s The End of the Innocence came on and I lost it. When you lose a parent for the first time (most of us have two after all) we lose our innocence and in that passage, we suddenly feel adult in a new way (no matter how old we are), a longing for our own childhood, and a need to forgive and be forgiven. Listen to the lyrics and you’ll understand. As Wordsworth reminds us in In Memoriam, there are seasons to our grief and, all these years later, this song no longer hits me in the gut, but does transport me back with loving memories of my father. I’ll play it Father’s Day.

What I’m reading:

The Fifth Season, by N. K. Jemisin. I am not a reader of fantasy or sci-fi, though I understand they can be powerful vehicles for addressing the very real challenges of the world in which we actually live. I’m not sure I know of a more vivid and gripping illustration of that fact than N. K. Jemisin’s Hugo Award winning novel The Fifth Season, first in her Broken Earth trilogy. It is astounding. It is the fantasy parallel to The Underground Railroad, my favorite recent read, a depiction of subjugation, power, casual violence, and a broken world in which our hero(s) struggle, suffer mightily, and still, somehow, give us hope. It is a tour de force book. How can someone be this good a writer? The first 30 pages pained me (always with this genre, one must learn a new, constructed world, and all of its operating physics and systems of order), and then I could not put it down. I panicked as I neared the end, not wanting to finish the book, and quickly ordered the Obelisk Gate, the second novel in the trilogy, and I can tell you now that I’ll be spending some goodly portion of my weekend in Jemisin’s other world.

What I’m watching:

The NBA Finals and perhaps the best basketball player of this generation. I’ve come to deeply respect LeBron James as a person, a force for social good, and now as an extraordinary player at the peak of his powers. His superhuman play during the NBA playoffs now ranks with the all-time greats, Larry Bird, Magic Johnson, MJ, Kobe, and the demi-god that was Bill Russell. That his Cavs lost in a 4-game sweep is no surprise. It was a mediocre team being carried on the wide shoulders of James (and matched against one of the greatest teams ever, the Warriors, and the Harry Potter of basketball, Steph Curry) and, in some strange way, his greatness is amplified by the contrast with the rest of his team. It was a great run.

May 24, 2018

What I’m listening to:

I’ve always liked Alicia Keys and admired her social activism, but I am hooked on her last album Here. This feels like an album finally commensurate with her anger, activism, hope, and grit. More R&B and Hip Hop than is typical for her, I think this album moves into an echelon inhabited by a Marvin Gaye’s What’s Going On or Beyonce’s Formation. Social activism and outrage rarely make great novels, but they often fuel great popular music. Here is a terrific example.

What I’m reading:

Colson Whitehead’s Underground Railroad may be close to a flawless novel. Winner of the 2017 Pulitzer, it chronicles the lives of two runaway slaves, Cora and Caeser, as they try to escape the hell of plantation life in Georgia. It is an often searing novel and Cora is one of the great heroes of American literature. I would make this mandatory reading in every high school in America, especially in light of the absurd revisionist narratives of “happy and well cared for” slaves. This is a genuinely great novel, one of the best I’ve read, the magical realism and conflating of time periods lifts it to another realm of social commentary, relevance, and a blazing indictment of America’s Original Sin, for which we remain unabsolved.

What I’m watching:

I thought I knew about The Pentagon Papers, but The Post, a real-life political thriller from Steven Spielberg taught me a lot, features some of our greatest actors, and is so timely given the assault on our democratic institutions and with a presidency out of control. It is a reminder that a free and fearless press is a powerful part of our democracy, always among the first targets of despots everywhere. The story revolves around the legendary Post owner and D.C. doyenne, Katharine Graham. I had the opportunity to see her son, Don Graham, right after he saw the film, and he raved about Meryl Streep’s portrayal of his mother. Liked it a lot more than I expected.

April 27, 2018

What I’m listening to:

I mentioned John Prine in a recent post and then on the heels of that mention, he has released a new album, The Tree of Forgiveness, his first new album in ten years. Prine is beloved by other singer songwriters and often praised by the inscrutable God that is Bob Dylan. Indeed, Prine was frequently said to be the “next Bob Dylan” in the early part of his career, though he instead carved out his own respectable career and voice, if never with the dizzying success of Dylan. The new album reflects a man in his 70s, a cancer survivor, who reflects on life and its end, but with the good humor and empathy that are hallmarks of Prine’s music. “When I Get To Heaven” is a rollicking, fun vision of what comes next and a pure delight. A charming, warm, and often terrific album.

What I’m reading:

I recently read Min Jin Lee’s Pachinko, on many people’s Top Ten lists for last year and for good reason. It is sprawling, multi-generational, and based in the world of Japanese occupied Korea and then in the Korean immigrant’s world of Oaska, so our key characters become “tweeners,” accepted in neither world. It’s often unspeakably sad, and yet there is resiliency and love. There is also intimacy, despite the time and geographic span of the novel. It’s breathtakingly good and like all good novels, transporting.

What I’m watching:

I adore Guillermo del Toro’s 2006 film, Pan’s Labyrinth, and while I’m not sure his Shape of Water is better, it is a worthy follow up to the earlier masterpiece (and more of a commercial success). Lots of critics dislike the film, but I’m okay with a simple retelling of a Beauty and the Beast love story, as predictable as it might be. The acting is terrific, it is visually stunning, and there are layers of pain as well as social and political commentary (the setting is the US during the Cold War) and, no real spoiler here, the real monsters are humans, the military officer who sees over the captured aquatic creature. It is hauntingly beautiful and its depiction of hatred to those who are different or “other” is painfully resonant with the time in which we live. Put this on your “must see” list.

March 18, 2018

What I’m listening to:

Sitting on a plane for hours (and many more to go; geez, Australia is far away) is a great opportunity to listen to new music and to revisit old favorites. This time, it is Lucy Dacus and her album Historians, the new sophomore release from a 22-year old indie artist that writes with relatable, real-life lyrics. Just on a second listen and while she insists this isn’t a break up record (as we know, 50% of all great songs are break up songs), it is full of loss and pain. Worth the listen so far. For the way back machine, it’s John Prine and In Spite of Ourselves (that title track is one of the great love songs of all time), a collection of duets with some of his “favorite girl singers” as he once described them. I have a crush on Iris Dement (for a really righteously angry song try her Wasteland of the Free), but there is also EmmyLou Harris, the incomparable Dolores Keane, and Lucinda Williams. Very different albums, both wonderful.

What I’m reading:

Jane Mayer’s New Yorker piece on Christopher Steele presents little that is new, but she pulls it together in a terrific and coherent whole that is illuminating and troubling at the same time. Not only for what is happening, but for the complicity of the far right in trying to discredit that which should be setting off alarm bells everywhere. Bob Mueller may be the most important defender of the democracy at this time. A must read.

What I’m watching:

Homeland is killing it this season and is prescient, hauntingly so. Russian election interference, a Bannon-style hate radio demagogue, alienated and gun toting militia types, and a president out of control. It’s fabulous, even if it feels awfully close to the evening news.

March 8, 2018

What I’m listening to:

We have a family challenge to compile our Top 100 songs. It is painful. Only 100? No more than three songs by one artist? Wait, why is M.I.A.’s “Paper Planes” on my list? Should it just be The Clash from whom she samples? Can I admit to guilty pleasure songs? Hey, it’s my list and I can put anything I want on it. So I’m listening to the list while I work and the song playing right now is Tom Petty’s “The Wild One, Forever,” a B-side single that was never a hit and that remains my favorite Petty song. Also, “Evangeline” by Los Lobos. It evokes a night many years ago, with friends at Pearl Street in Northampton, MA, when everyone danced well past 1AM in a hot, sweaty, packed club and the band was a revelation. Maybe the best music night of our lives and a reminder that one’s 100 Favorite Songs list is as much about what you were doing and where you were in your life when those songs were playing as it is about the music. It’s not a list. It’s a soundtrack for this journey.

What I’m reading:

Patricia Lockwood’s Priestdaddy was in the NY Times top ten books of 2017 list and it is easy to see why. Lockwood brings remarkable and often surprising imagery, metaphor, and language to her prose memoir and it actually threw me off at first. It then all became clear when someone told me she is a poet. The book is laugh aloud funny, which masks (or makes safer anyway) some pretty dark territory. Anyone who grew up Catholic, whether lapsed or not, will resonate with her story. She can’t resist a bawdy anecdote and her family provides some of the most memorable characters possible, especially her father, her sister, and her mother, who I came to adore. Best thing I’ve read in ages.

What I’m watching:

The Florida Project, a profoundly good movie on so many levels. Start with the central character, six-year old (at the time of the filming) Brooklynn Prince, who owns – I mean really owns – the screen. This is pure acting genius and at that age? Astounding. Almost as astounding is Bria Vinaite, who plays her mother. She was discovered on Instagram and had never acted before this role, which she did with just three weeks of acting lessons. She is utterly convincing and the tension between the child’s absolute wonder and joy in the world with her mother’s struggle to provide, to be a mother, is heartwarming and heartbreaking all at once. Willem Dafoe rightly received an Oscar nomination for his supporting role. This is a terrific movie.

February 12, 2018

What I’m listening to:

So, I have a lot of friends of age (I know you’re thinking 40s, but I just turned 60) who are frozen in whatever era of music they enjoyed in college or maybe even in their thirties. There are lots of times when I reach back into the catalog, since music is one of those really powerful and transporting senses that can take you through time (smell is the other one, though often underappreciated for that power). Hell, I just bought a turntable and now spending time in vintage vinyl shops. But I’m trying to take a lesson from Pat, who revels in new music and can as easily talk about North African rap music and the latest National album as Meet the Beatles, her first ever album. So, I’ve been listening to Kendrick Lamar’s Grammy winning Damn. While it may not be the first thing I’ll reach for on a winter night in Maine, by the fire, I was taken with it. It’s layered, political, and weirdly sensitive and misogynist at the same time, and it feels fresh and authentic and smart at the same time, with music that often pulled me from what I was doing. In short, everything music should do. I’m not a bit cooler for listening to Damn, but when I followed it with Steely Dan, I felt like I was listening to Lawrence Welk. A good sign, I think.

What I’m reading:

I am reading Walter Isaacson’s new biography of Leonardo da Vinci. I’m not usually a reader of biographies, but I’ve always been taken with Leonardo. Isaacson does not disappoint (does he ever?), and his subject is at once more human and accessible and more awe-inspiring in Isaacson’s capable hands. Gay, left-handed, vegetarian, incapable of finishing things, a wonderful conversationalist, kind, and perhaps the most relentlessly curious human being who has ever lived. Like his biographies of Steve Jobs and Albert Einstein, Isaacson’s project here is to show that genius lives at the intersection of science and art, of rationality and creativity. Highly recommend it.

What I’m watching:

We watched the This Is Us post-Super Bowl episode, the one where Jack finally buys the farm. I really want to hate this show. It is melodramatic and manipulative, with characters that mostly never change or grow, and it hooks me every damn time we watch it. The episode last Sunday was a tear jerker, a double whammy intended to render into a blubbering, tissue-crumbling pathetic mess anyone who has lost a parent or who is a parent. Sterling K. Brown, Ron Cephas Jones, the surprising Mandy Moore, and Milo Ventimiglia are hard not to love and last season’s episode that had only Brown and Cephas going to Memphis was the show at its best (they are by far the two best actors). Last week was the show at its best worst. In other words, I want to hate it, but I love it. If you haven’t seen it, don’t binge watch it. You’ll need therapy and insulin.

January 15, 2018

What I’m listening to:

Drive-By Truckers. Chris Stapleton has me on an unusual (for me) country theme and I discovered these guys to my great delight. They’ve been around, with some 11 albums, but the newest one is fascinating. It’s a deep dive into Southern alienation and the white working-class world often associated with our current president. I admire the willingness to lay bare, in kick ass rock songs, the complexities and pain at work among people we too quickly place into overly simple categories. These guys are brave, bold, and thoughtful as hell, while producing songs I didn’t expect to like, but that I keep playing. And they are coming to NH.

What I’m reading:

A textual analog to Drive-By Truckers by Chris Stapleton in many ways is Tony Horowitz’s 1998 Pulitzer Prize winning Confederates in the Attic. Ostensibly about the Civil War and the South’s ongoing attachment to it, it is prescient and speaks eloquently to the times in which we live (where every southern state but Virginia voted for President Trump). Often hilarious, it too surfaces complexities and nuance that escape a more recent, and widely acclaimed, book like Hillbilly Elegy. As a Civil War fan, it was also astonishing in many instances, especially when it blows apart long-held “truths” about the war, such as the degree to which Sherman burned down the south (he did not). Like D-B Truckers, Horowitz loves the South and the people he encounters, even as he grapples with its myths of victimhood and exceptionalism (and racism, which may be no more than the racism in the north, but of a different kind). Everyone should read this book and I’m embarrassed I’m so late to it.

What I’m watching:

David Letterman has a new Netflix show called “My Next Guest Needs No Introduction” and we watched the first episode, in which Letterman interviewed Barack Obama. It was extraordinary (if you don’t have Netflix, get it just to watch this show); not only because we were reminded of Obama’s smarts, grace, and humanity (and humor), but because we saw a side of Letterman we didn’t know existed. His personal reflections on Selma were raw and powerful, almost painful. He will do five more episodes with “extraordinary individuals” and if they are anything like the first, this might be the very best work of his career and one of the best things on television.

December 22, 2017

What I’m reading:

Just finished Sunjeev Sahota’s Year of the Runaways, a painful inside look at the plight of illegal Indian immigrant workers in Britain. It was shortlisted for 2015 Man Booker Prize and its transporting, often to a dark and painful universe, and it is impossible not to think about the American version of this story and the terrible way we treat the undocumented in our own country, especially now.

What I’m watching:

Season II of The Crown is even better than Season I. Elizabeth’s character is becoming more three-dimensional, the modern world is catching up with tradition-bound Britain, and Cold War politics offer more context and tension than we saw in Season I. Claire Foy, in her last season, is just terrific – one arched eye brow can send a message.

What I’m listening to:

A lot of Christmas music, but needing a break from the schmaltz, I’ve discovered Over the Rhine and their Christmas album, Snow Angels. God, these guys are good.

November 14, 2017

What I’m watching:

Guiltily, I watch the Patriots play every weekend, often building my schedule and plans around seeing the game. Why the guilt? I don’t know how morally defensible is football anymore, as we now know the severe damage it does to the players. We can’t pretend it’s all okay anymore. Is this our version of late decadent Rome, watching mostly young Black men take a terrible toll on each other for our mere entertainment?

What I’m reading:

Recently finished J.G. Ballard’s 2000 novel Super-Cannes, a powerful depiction of a corporate-tech ex-pat community taken over by a kind of psychopathology, in which all social norms and responsibilities are surrendered to residents of the new world community. Kept thinking about Silicon Valley when reading it. Pretty dark, dystopian view of the modern world and centered around a mass killing, troublingly prescient.

What I’m listening to:

Was never really a Lorde fan, only knowing her catchy (and smarter than you might first guess) pop hit “Royals” from her debut album. But her new album, Melodrama, is terrific and it doesn’t feel quite right to call this “pop.” There is something way more substantial going on with Lorde and I can see why many critics put this album at the top of their Best in 2017 list. Count me in as a huge fan.

November 3, 2017

What I’m reading:

Just finished Celeste Ng’s Little Fires Everywhere, her breathtakingly good second novel. How is someone so young so wise? Her writing is near perfection and I read the book in two days, setting my alarm for 4:30AM so I could finish it before work.

What I’m watching:

We just binge watched season two of Stranger Things and it was worth it just to watch Millie Bobbie Brown, the transcendent young actor who plays Eleven. The series is a delightful mash up of every great eighties horror genre you can imagine and while pretty dark, an absolute joy to watch.

What I’m listening to:

I’m not a lover of country music (to say the least), but I love Chris Stapleton. His “The Last Thing I Needed, First Thing This Morning” is heartbreakingly good and reminds me of the old school country that played in my house as a kid. He has a new album and I can’t wait, but his From A Room: Volume 1 is on repeat for now.

September 26, 2017

What I’m reading:

Just finished George Saunder’s Lincoln in the Bardo. It took me a while to accept its cadence and sheer weirdness, but loved it in the end. A painful meditation on loss and grief, and a genuinely beautiful exploration of the intersection of life and death, the difficulty of letting go of what was, good and bad, and what never came to be.

What I’m watching:

HBO’s The Deuce. Times Square and the beginning of the porn industry in the 1970s, the setting made me wonder if this was really something I’d want to see. But David Simon is the writer and I’d read a menu if he wrote it. It does not disappoint so far and there is nothing prurient about it.

What I’m listening to:

The National’s new album Sleep Well Beast. I love this band. The opening piano notes of the first song, “Nobody Else Will Be There,” seize me & I’m reminded that no one else in music today matches their arrangement & musicianship. I’m adding “Born to Beg,” “Slow Show,” “I Need My Girl,” and “Runaway” to my list of favorite love songs.

https://ift.tt/eA8V8J from President's Corner https://ift.tt/2NVlWtZ

via IFTTT

0 notes

Text

Picasso Museum

Located in Hôtel Salé, the Musée Picasso is something that I have also been looking forward to seeing since arriving in Paris. Growing up and learning from all of his different paintings, I was very eager to see a lot of his work in person. A man of different styles, Picasso I find is one of the most interesting artists in that although a lot of his work can sometimes look like he made it in two minutes, it is cool to understand that he found lots of purpose in every little detail contributed in his paintings.

This beautiful building consisted of a lot of exhibitions within his work. The largest and temporary exhibit that was put in place right when we walked in was the Guernica Exhibition.

Painted in 1937, this monumental artwork is both a combination of research conducted by Picasso for 40 years and is also a popular icon. Replicated all over the world, at the same time it was to be considered an anti-fascist, anti-franco, and pacific symbol for centuries.

Moving more into the exhibit, we were able to find a lot of his original sketches and drafts that went along with his creation. A lot of the different rooms expose more of the story and the posterity of Guernica. Divided into its visual, political, literary contexts, and time periods, the exhibit splits his discovered pieces into different rooms.

Something that I had noticed was that we were able to see his use of a lot of the same features in different paintings: The Horse, The Soldier, The Woman, The Bird, The Bull, The Electric Light, etc.

I find this piece personally to be a little chaotic. But to me that is exactly what I feel like Picasso was trying to portray. What I like the most about it I think is his use of color. I believe that since he only used three colors being black, white, and gray, it almost reiterates the painting’s idea of being more of a message. Everywhere there seems to be death and dying. Something that Picasso wanted to provide in order to prevent violence and despair while during his lifetime.

Another exhibit that we were able to enjoy sent us upstairs where in all the rooms there were different styles of paintings that went along with the different artistic style that Picasso had played around with.

It is simply amazing that Picasso was able to create such a large variety different paintings. This truly artistic man is an inspiration to all who considerably eat, live, breathe, art. I have no idea how this man had so much time and patience for many of these pieces. This spaniard was very courageous in immersing himself within the different pools of art. Not only did he paint, but he also was very talented in a lot of other styles of art such as, sculpture, drawing, etc.

It is almost as if this artist is himself one museum. Sparked with different ideas and reactions of the various time periods, it was cool to see how we were able to notice the time periods change in his paintings. Whether or not it was the scene, action, landscape, or the people in his paintings. If this museum is only partial in obtaining a lot of his work, I can’t imagine how many more paintings he has spread out across the world. It is true that I definitely enjoyed myself walking around this museum.

0 notes

Text

The Remnant of God in the World: Daniel

RECAP & PREPARING FOR CG Daily Reading for Week

Esther 6-10, Psalm 54

Daniel 1-3, Psalm 55

Daniel 4-6, Psalm 56

Daniel 7-9, Psalm 57

Daniel 10-12, Psalm 58

Haggai 1-2, Psalm 59

Zechariah 1-4, Psalm 60

Resources for Week

Read Scripture Video: Daniel

Read: Daniel 7

FOCUS OF TIME TOGETHER

To participate in an intense study on how to begin reading Jewish apocalyptic literature and to practice these hermeneutic skills together by taking a careful look at Daniel 7.

GROUND RULE / GOAL / VALUE FOR THE WEEK

Goal: Our goal this week is to practice intellectual humility by laying our ideas and presuppositions aside for a bit in order to explore truth in interdependent community. Participate in discussion with an intent to assist in the group’s shared exploration rather than either refusing to participate or trying to coerce the group to see things your way.

CONNECTION AND UNITY EXERCISE (MUTUAL INVITATION)

Share your highs and lows from the week.

OPENING PRAYER

Sit silently for three minutes. As you do, listen for any thoughts or pictures or ideas that go through your mind that may be inspired by the Holy Spirit. After this silent prayer, take a couple minutes to invite one another to share anything they may have heard.

Then read this prayer aloud:

Lord, grant us pure hearts and clear minds;

Direct us in discerning what is good and true and beautiful;

Guide us along the path of wisdom and lead us in the way of humility;

We are frail and fallible creatures;

Be near to us, Lord;

Amen.

INTRO TO DISCUSSION

This week’s material is an intense study on the hermeneutics of apocalyptic literature using Daniel 7 as our focus. It is perhaps the most rigorous study of the year. We chose to structure the material this way because we didn’t feel it would be faithful to the goal of YOBL or the book of Daniel to skip the hermeneutic work necessary to grow in our Bible-reading skills. Accordingly, there will be more content to digest than usual. Because of this, we’ve changed the normal structure to make the content more digestible. There will also be no structured small group time. Focus your energy on reading and understanding the ideas presented. Then, honestly process your emotional responses to your past and current interactions with apocalyptic literature and the variety of interpretations in the church.

LARGE GROUP DISCUSSION

Questions for Basic Understanding

These questions are to help us interpret and understand the text as it was intended to be interpreted and understood.

Read:

The Book of Daniel in Context

Last week, we began our final series on Old Testament books called “The Remnant of God in the World,” chronicling the final chapters in the Old Testament story about God’s plan to heal the world through His people Israel. In Ezra and Nehemiah, we read historical sketches of the first Jewish exiles who returned to Jerusalem to start over again by rebuilding the Temple, relearning the Torah, and reconstructing the city walls. We saw this exciting moment of liberation turn anticlimactic as division and turmoil broke out among those trying to be God’s renewed people in Jerusalem. Before long, the same evil and idolatry that led to the punishment of exile in the first place resurfaced, begging the questions: Is exile really over? Has this surviving remnant of the people of God truly been purged and purified of anything? Where do we go from here?

Interestingly, the book of Daniel serves as dual bookends to Ezra and Nehemiah, acting as both preface and conclusion to the return-to-Jerusalem story. In Daniel 5 and 6, we read how Daniel’s skilled and faithful work as a government official combined with his great spiritual wisdom and divine connection to the Jewish God earned him honor with the Babylonian rulers Nebuchadnezzar and Belshazzar as well as the other kings who eventually overthrew Babylon. Following the “writing on the wall” events of chapter 5, the Babylonian empire was conquered by what is called the Median-Persian Empire. King Darius the Mede, now ruling over the land, was so moved by Daniel’s divine vindication and protection in the lion’s den that he actually endorsed Judaism throughout the empire. Chapter 6 concludes with: “So Daniel prospered during the reign of Darius and the reign of Cyrus the Persian.” When Ezra 1:1 says that “The Lord moved the heart of Cyrus king of Persia to make a proclamation throughout his realm [releasing Jews to go home and build the Temple],” it is fair to say that Daniel was the primary vessel God used to do so. In other words, Daniel’s faithful witness within the Babylonian government was one of the central causes for the release of the Jews from exile. The great restart recorded in Ezra-Nehemiah was only possible because of him.

But also, the book of Daniel serves as a concluding synopsis to Ezra-Nehemiah that at least partially answers the questions raised about whether the exile was truly over and how then God’s people would live. Remember that in Jeremiah 29:10, Jeremiah recorded a promise from God to release Israel from exile after seventy years. The return to rebuild the Temple seemed to mark the end of this punishment and the beginning of the promised liberation. Daniel was hopeful for this too: “In the first year of Darius son of Xerxes (a Mede by descent), who was made ruler over the Babylonian kingdom — in the first year of his reign, I, Daniel, understood from the Scriptures, according to the word of the Lord given to Jeremiah the prophet, that the desolation of Jerusalem would last seventy years” (Dan 9:1-2). Therefore, Daniel becomes hopeful that he may indeed live to see the end of exile and goes to bring about God’s promised action by confessing on behalf of Israel. This leads to a shocking and disheartening word from God:

“While I was still in prayer, Gabriel, the man I had seen in the earlier vision, came to me… He instructed me and said to me, ‘Daniel, I have now come to give you insight and understanding. As soon as you began to pray, a word went out, which I have come to tell you, for you are highly esteemed. Therefore, consider the word and understand the vision:

“‘Seventy ‘sevens’ are decreed for your people and your holy city to restrain transgression, to put an end to sin, to atone for wickedness, to bring in everlasting righteousness, to seal up vision and prophecy and to anoint the Most Holy Place.’”

(Daniel 9:21-24, abbreviated)