#and then had to follow that up with reading about malaria throughout history

Text

frequently what happens is I'll be drawing a comic and think, huh. I wonder what shoes a 14th/15th century cardinal would wear. I bet they had fancy rules about it, and the answer will be in a 500 page book about the early modern cardinal. I'll think, 'WELLLLLL since I'm already here, I'll check out this other chapter that sounds interesting,' and then I'll find out that the vatican is literally hazardous to your health, but from that point on I'll be locked in for the entire book. I'll start reading through all the citations while checking to see what else some of the contributors have written. the comic has been forgotten entirely because I need to know more about the hats.

#my folder on the knights templar and other military-monastic orders is MASSIVE because i keep spiralling into other areas of#research. same with the cardinals. i will Keep Going until i hit an insurmountable wall#i have like. several books about syphilis in the medieval/renaissance era because i disagreed with something someone said#and then had to follow that up with reading about malaria throughout history#i may have to actually learn latin for this one and. well! if i must. then i will#i wont be happy about it but i'll do it (<<< someone who absolutely does not have to do this in the slightest)

272 notes

·

View notes

Text

What to Remember When Your Sermon Gets No Response

If I’d titled this article, “Left at the Altar,” you’d probably think you were about to read a sob story about some poor fellow twiddling his thumbs as his bride-to-be jumps in a cab and makes a run for it.

While this isn’t that kind of post, it does involve a sob story of sorts—one that involves being lonely at the altar, when you finish up a sermon and see no response.

I’ve had the joy of serving in vocational ministry for over 18 years now. Some of those years have been filled with incalculable fruit. But other years have left me feeling ineffective and isolated in ministry.

I’m sure you’ve been there too. You preach your heart out faithfully and call for a response, but only hear crickets.

Well, I’ve got some encouragement for you. You’re not alone. Remember these two stories of faithful men who experienced long seasons of ineffectiveness by worldly standards

1. Remember Jeremiah

Before you sob too much, brothers, don’t forget the prophet Jeremiah. God told him in Jeremiah 7:2, “ Stand in the gate of the house of the Lord and there call out this word: ‘Hear the word of the Lord, all you people of Judah who enter through these gates to worship the Lord.”

Then we read in Jeremiah 7:27, “When you speak all these things to them, they will not listen to you. When you call to them, they will not answer you.”

Jeremiah is known as the weeping prophet. Why? Because although he knew what was coming, no one would listen to him for 40 years. That’s four decades of not seeing any fruit from his labor!

We’ve had Sundays at my church where I’m scrambling to find enough folks to help people fill out membership cards and to counsel those who are making decisions to follow Christ or are praying on the steps of the stage. But we’ve also had Sundays where I felt like I was preaching to a brick wall.

Jeremiah was obedient for 40 years despite no earthly success, yet to me, this prophet was extremely successful. Yes, he doubted God, but he ultimately stood firm and took an unpopular message to a people under judgment.

2. Remember Carey

Then there’s William Carey, a man many consider to be the father of modern missions. After seven years of what probably felt to him like preaching to brick walls across India, he baptized his first convert in December, 1800. Note this gospel fruit took seven years to appear!

By the time Carey passed away, he’d served as a missionary in India for over 40 years without a furlough. What did he have to show for it? In a nation with a population of millions, he had 700 converts.

One of the things I remember most about Carey is a quote from a sermon he preached in 1792: “Expect great things from God; attempt great things for God!”

And Carey’s walk matched that talk. He was faithful throughout four decades of ministry that involved combatting infanticide, battling malaria, translating the Bible into the major languages of India, losing his son to a terrible disease, fighting widow-burning, and even having his wife accuse him of awful things.

His life was a roller coaster for sure, yet he remained faithful. And because of his faithfulness, history witnessed the birth of the modern missions movement that produced missionaries like Hudson Taylor, David Livingstone, and Adoniram Judson.

Keep Your Hand to the Plow

I doubt you’re reading this as a pastor who’s spent 40 years spinning your wheels without any fruit. But if you’re currently feeling lonely at the altar, I have one word for you:

Good.

Assuming you’re preaching the Word faithfully and that your loneliness stems from a burden for lost souls in need of salvation:

Good.

Keep it up. Don’t quit. Stay faithful. Keep preaching, keep plowing, and trust the Lord with the results. Continue to evangelize throughout the week, invite folks to church, and preach your heart out week-in and week-out.

I leave you with the words of Revelation 3:10:

“Because you have kept my command to endure, I will also keep you from the hour of testing that is going to come on the whole world to test those who live on the earth.”

If you’ve been a little lonely at the altar, keep on praying, keep on preaching, and keep on pleading for a response. May the Spirit bring forth fruit in and through our faithfulness to preach the Word.

Want some encouragement? https://amzn.to/4b9rASR

0 notes

Text

Eight Causes Of Low Blood Sugar Without Diabetes

Does low blood sugar level levels run in the family? This may be significant, especially left unattended, and unfortunately several don't understand it! People typically question why they experience low blood sugar degrees also without diabetes mellitus, thinking nothing of it.Does low blood glucose degrees run in the household? This might be serious, especially left without treatment, and regrettably numerous don't recognize it! Individuals commonly question concerning why they experience reduced blood sugar degrees also without diabetes, downplaying it.

But did you recognize that very low blood sugar, understood as hypoglycemia, does not only happen in people with diabetes? It additionally takes place for those that just have low blood glucose, and for numerous factors. Wondering why reduced blood sugar occurs regardless of attempting to live healthy and balanced without diabetes? Continue reading as I reveal you the 8 different sources of reduced blood sugar without diabetes.

What Is Hypoglycemia? What Are Its Signs?

Like mentioned, hypoglycemia is very reduced blood glucose degrees, which are usual for those who have diabetes. It does take place in those without the condition, with two types:

Reactive Hypoglycemia occurring hours after consuming a meal

Fasting hypoglycemia which can be connected to medication or diseases

If ever you do suffer from hypoglycemia, you'll experience some or many of the adhering to signs:

Hunger

Anxiety

Shakiness

Paleness

Sweating

Fast or irregular heartbeat

Fatigue and sleepiness

Irritability

Dizziness

And as the condition gets worse without correct therapy, one may experience:

Blurred vision

Confusion

Loss of awareness or seizures

Non-diabetic hypoglycemia is detected through a physical exam, with clinical specialists asking concerning any medicine taken, surgical history, as well as any conditions. Blood glucose levels will likewise be examined, with a mixed-meal tolerance test being another means to diagnose.

Eight Source of Low Blood Glucose Without Diabetes

You're possibly wondering: Exactly what creates low blood glucose also without having diabetes? There are actually a variety of causes, such as:

Drinking Too Much Alcohol. When your blood sugar level is reduced, after that the pancreas launches hormones called glucagon. This assists the liver break down saved power, normalizing blood sugar level degrees. If you drink way too much alcohol, the liver is not able to function correctly, not able to release sugar back to the bloodstream. This triggers momentary hypoglycemia.

Certain Medications. If you take diabetic issues drug also without having the condition, then this can trigger hypoglycemia as a drug like these would generally reduce one's blood sugar degrees. It can additionally be a side result from various other type of medicine, like:

Malaria medication

Specific antibiotics

Certain pneumonia medicines

Anorexia. Those that have poor diet regimens or eating disorders aren't eating sufficient for their body to work well. As a result of the lack of necessary nutrients as well as calories, it will not be enough for your body to generate adequate glucose, causing hypoglycemia in the lengthy run.

Hepatitis. This is an inflammatory infection which impacts the liver, stopping it from functioning properly. It likewise impacts the way your body creates sugar. As a result of this, it does not produce enough glucose, which triggers troubles with blood glucose degree, causing hypoglycemia.

Adrenal or Pituitary Gland Disorders. Those that have troubles with the adrenal or pituitary glands may have greater danger of hypoglycemia. This is since these glands impact hormones which control sugar manufacturing. It's finest to have it examined and also dealt with immediately to stop additional symptoms.

Kidney Problems. If you have a trouble with your kidneys, then the medicine and also food yo take in accumulates in the blood stream. The accumulation modifications blood sugar level levels, thus bring about hypoglycemia as well as other symptoms if not dealt with well.

Pancreatic Tumor. This is an unusual and severe condition which can cause hypoglycemia. Growths found in the pancreas can create it to produce excessive insulin. And when insulin levels are high, the blood sugar level levels would certainly go down. Getting rid of the lump is the very best solution

An Early Sign of Diabetes. For those without diabetic issues, this can in fact be a very early indication of the condition. If you have member of the family that have or have had diabetes and also it runs in the household, after that it's finest to have on your own inspected and also take precautionary actions to stop it.

How to Treat and Take Care Of Low Blood Sugar

Now that you're familiar with what you require to learn about non-diabetic hypoglycemia, exactly how can you correctly deal with and manage it? Right here are the adhering to therapies you might be recommended for, as well as lifestyle changes to follow:

Immediate Treatment. If you experience the signs and symptoms right away, after that you must consume 15-20 grams of carbs promptly. You can stake it through juice, sweets, or glucose tablet computers. This helps the symptoms though make certain you inspect your blood sugar every 15 mins, treating it if it's still low.

For those with serious symptoms or if you still don't really feel well also after consuming carbs, then you need to call medical emergency situations as soon as possible for immediate drug as well as treatment.

Dietary Changes. Nutritional adjustments are additionally recommended, such as taking small dishes and snacks every couple of hours. Start having much healthier food selections with protein and fats, along with high-fiber food. And also as much as possible, prevent food with high-sugar levels.

Long-Term Solutions. For lasting services, this can rely on what triggers your hypoglycemia. If medicine triggers it, then an adjustment of medication is required. If ever you have a hidden problem, then treatment or surgical procedure to recover your body is required.

Preventing Hypoglycemia. You can prevent hypoglycemia by eating frequently throughout the day as well as never ever avoiding meals. Cut back on caffeine and alcohol as well.

Having normal workout likewise helps stop hypoglycemia and also maintains your blood sugar level degrees healthy.

Wrapping It Up

Hypoglycemia is a significant condition that requires therapy today. With the correct therapy as well as monitoring, you'll have the ability to decrease the symptoms and stay healthy all throughout. Everything come down to learning more about what it is, what causes it, as well as how you can treat it.

Hopefully, this article on the reasons of low blood sugar level without diabetes mellitus gave you a concept on why you struggle with hypoglycemia and the appropriate action you need to take now. So don't wait any kind of longer and also discover the best diabetes mellitus physicians for you today!

If you have any kind of questions or wish to share your experiences with hypoglycemia, then comment below. your ideas are much appreciated.

About Jenny Pattison.

Jenny has dedicated herself to developing gorgeous content, either for her or numerous customers. She likes to develop material regarding nearly anything, she is most passionate by beauty about which she additionally vlogs.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

January Reading and Reviews by Maia Kobabe

We Have Always Lived in the Castle by Shirley Jackson

I had very mixed feelings about this book. There were aspects of it I really liked and others I didn't like at all. The first 40 pages were a struggle, in which a character I didn't yet care about was forced to suffer in somewhat irritating ways, with consequences I didn't yet understand. I might have given it up at that point except so many people told me they love this book. After page 40, the middle section suddenly unfolded in a strange, whimsical, and intriguing way. I came to really appreciate the two sisters (Constance and Merricat) who have lived in the Blackwood family home with their uncle since the entire rest of their family died. Pages 40-100 were really enjoyable. Then the last 40 pages (it's a short book) were once again difficult to read, but this time because characters that I cared for were suffering.

The Hidden Witch by Molly Knox Ostertag

This is a really nice follow up to the previous book. The story is less focused on Aster and spreads out into a group of teens, some magic, some not, all trying to figure out which direction they want to go in life. The story takes place over about one week, and in this one the big battle is not against a cursed dragon, but against the bruises and wounds life deals to every misfit teen. The art is clear and effective. I want to use this book as a model for my own next comic, keeping in mind that an all ages comic does not have to be complex to be good: sometimes a sweet small story about feelings hits exactly right.

Onwards Towards Our Noble Deaths by Shigeru Mizuki

This is a beautiful book about a terrible subject. It's a fictionalized memoir of one unit of the Japanese Imperial army stationed on an island in Papua New Guinea during WWII. The soldiers, who are under-prepared, underfeed and under-informed, struggle against the unfamiliar climate and ecosystem. Before they even see the enemy many have died of fevers, malaria and freak accidents such as crocodile attacks and attempting to fish with hand grenades. But even the ones who survive these deadly mishaps are doomed, because they have a manic hotheaded commander who has his sights set on a suicide mission. The characters are drawn in a loose, cartoony style set against a hyper-realistic, gorgeously rendered background. Some of the drawings of sky and forest took my breath away. However, I struggled to tell the characters apart because of the minimal portrait style. I think I was less emotionally effected than I might have been since I was often unable to follow a character's path throughout the book.

The Essex Serpent by Sarah Perry

This book swept me away. Set in Victorian England, it tells the story of a small town on the Essex coast which is haunted by the rumor of a deadly sea serpent. It is also the story of Cora Seabourne, who's abusive husband has recently died, leaving her a happy window finally free to pursue her interests in science and natural history. She believes the Essex Serpent may be a prehistoric beast which has survived to modern times. It is also the story of Cora's circle of friends- two doctors, a union organizer for the working class, a member of government, a county parson and his wife- who are all, to some extent or another, in love which each other's minds, or bodies, or both. Feelings intersect with clashes of ideals, often argued about on long walks through a richly described landscape- bare branches against a soft grey sky, vivid green moss covering leaf mold and dark soil. Whether or not the Serpent exists, every character is tangled in it's coils.

Upgrade Soul by Ezra Claytan Daniels

This comic pulls no punches. It's a complicated and emotional story of human scientific daring and utter folly. The lead characters are Hank and Molly Nonnar, a couple who have been married for 45 years. Molly is a doctor and researcher, and Hank is an author who writes novels about the popular sci-fi character his father invented in the 1950s. A big movie deal gives him the funds to begin investing in a ground-breaking, but under-tested, experiment: a way to rejuvenate and improve the body at the cellar level. Hank and Molly sign up as the first human test subjects, and the results are stranger and more devastating than either could ever have imagined. Gorgeously drawn and luminously colored.

Mortal Engines by Philip Reeve

I was expecting a hefty sci-fi novel for adults when I put this on hold at the library, but what arrived instead was a YA steampunk fairy tale. It was very enjoyable, and surprisingly clever! Set in a loosely defined dystopian future, the action begins in London, which is now a Traction city. The Traction cities of Europe roll over hills, plains, and the dusty beds of ancient long-dried oceans on massive wheels, chasing down smaller towns and devouring them. This is Municipal Darwinism at work, and Tom, a Third Class Apprentice in London's museum, has been taught that it is right and noble that the strong should grown stronger by ingesting the weak. Only when he falls from London and has to survive in a shattered landscape of deserts, marshes, pirates, slavers, rogue towns and Anti-Traction League spies does he begin to realize that what he grew up believing in might actually be monstrous.

His Majesty's Dragon by Naomi Novik

I have read a lot of books about dragons- see my entire "dragon books" goodreads shelf- but this one has some delightful elements I've never read before. It begins with an English's Navy ship's capture of a French vessel during the Napoleonic Wars. Captain William Laurence is at first delighted when he learns that the captured ship was carrying a prized dragon egg; then he is dismayed, when he learns how near it is to hatching. To be considered "tame" a dragon must be named and harnessed by a human before it's first feeding; the human who does this will be paired with the dragon for life, and during war-time serve in the Air Corp of his majesty's army. Laurence has no desire to upend his successful Navy life for an entirely new (and less respected) branch of the military- but he is the one chosen by the dragonet, who he names Temeraire. This is the beginning of a growing friendship, a coming of age, and a deepening education for them both. They are eventually assigned to re-training at a distant Scottish dragon covet. I loved the scenes of their practices and maneuvers, and the fact that a military dragon in this world is staffed by an entire crew. Aside from the captain, each dragon has a signal-flagger, a medic, bombers, gunmen, runners, a team of harnessers and more. These dragon fights are more like high-speed tall-ship battles in the air than like two eagles clawing at each other. Well researched and very engaging, with the emotional relationship of humans and dragons at it's heart. Laurence would not have chosen Temeraire, but once Temeraire has chosen him, his life is changed forever.

FTL Y'all edited by C. Spike Trotman

I need to say up top that my review of this book is biased, because I am one of the contributors. Regardless- this book is FANTASTIC. Each story plays with the premise of a world in which faster than light speed engines exist, and can be built at a relatively low cost by a layperson. Many of the stories feature queer or POC characters. Some include contact with alien life- others with colonization, scientific exploration, families, separation and reunion, depression, joy- it's a rich feast. I can't even pick out favorites, because all of the stories were so strong!

Public Relations by Katie Heaney and Arianna Rebolini

This book is a BLATANT self-insert 1D fanfiction turned into a novel, and you know I eat that shit up with a spoon. The main character is Rose Reed, a 26 year old assistant at a PR firm in New York. The chance of a lifetime lands in her lap when she is asked to sit in on a PR strategy meeting for Archie Fox (cough*Harry Styles*cough) a former youtube singer-star who has developed a mega following of teenage girls. Unfortunately, his latest album wasn't a hit and his manager is worried his next one won't be either without some major help. Rose proposes a winning strategy- a manufactured romance with up and coming pop darling Raya. Archie accepted this plan with one condition- Rose must be his contact and head of the project at the PR firm. How much romance can Rose invent without getting caught up in it herself? Will her lesbian best friend be able to contain her feels when the opportunity comes to plan outfits for Archie/Harry? Will Rose's growing crush ruin everything and cost her her job? You can probably guess the answers to all of these questions yourself, but if you don't a bit of predictability, there's plenty to enjoy in this celebrity whirlwind romance.

Ink in Water by Lacy Davis and Jim Kettner

This book has been on my to-read list for a while, and I'm glad I finally snagged it. It's a beautifully drawn black and white comics memoir of self-esteem, eating disorders, recovery and body positivity. At the start of the book, Lacy is an art student living in Portland, Oregon. She's a punk, a zine maker, a feminist, a voracious reader, bisexual and owner of many Bikini Kill albums. But despite her politics, the seeds of a deep body anxiety are waiting in the dark to grown into an addiction to exercise and food control which ends up taking over Lacy's entire life. Her path to recovery is long and includes some painful set backs, but with art, music, and love at her side Lacy works to regain her balance and move forward.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Week Two Reading List

My second week of graduate school has come to a close. Despite being sick, for the second week in a row, I felt very content with the progress that I’ve made this week. To summarize this week, I’ll just briefly reflect on the things that I’ve read this week.

Academic Reading

What Research District Leaders Find Useful (Penuel, Farrell, Allen, Toyama, Coburn, 2018). This study examined what educational research is used by district leaders and how. The top uses of educational research are: to support district leader’s own professional learning, to provide instructional leadership, to design policies, programs, and initiatives, and to support and monitor implementation efforts. We are currently critiquing this study in small groups during class time.

Marching Forward, Marching in Circles: A History of Problems and Dilemmas in Teacher Preparation (Schneider, 2017). This essay provides a historical account of teacher preparation in the United States. The history is split into four eras: Teaching Unregulated (1800-1860), Early Bureaucracy (1860-1920), Late Bureaucracy (1920-1980), and Resurgent Deregulation (1980 - Present). Throughout the descriptions of the eras, Schneider poses problems and dilemmas of teacher preparation over time. The difference between problems and dilemmas is that problems and be solved, dilemmas can only be managed. For example, a problem in Era I was that standards for teacher preparation were null; this was fixed over time with increasing standards. But the associated dilemma is that we must balance with these standards with teaching remaining an accessible career, lest we are left with a shortage of teachers. Personally, I enjoyed the articles historical methods. It inspired me to start thinking about writing a similar piece to highlight the challenges of classical education in the United States, particularly in the university setting. I have been interested in writing a higher education piece about the state of the humanities Classics for awhile now, and I think this would be a great starting point.

The Case for Self-Care as a Core Practice for Teaching (Peercy, 2019). Peercy highlights the particular challenges of novice ESOL teachers in secondary schools. Their unique struggles include having to work with students that are emotional traumatized, prove themselves and their worth in the school system, and counteract the perceptions of other professionals, which frequently will use ESOL teachers for grunt work. Just coming out of my first year of teaching ESOL in the private sector, this article was particularly interesting to me. It encouraged me to think about the struggles that I had as a novice teacher, namely: a feeling of dispensability as a teacher, a lack of trust and support in staff, and expectations for unpaid administrative work and preparation. I’m curious to how much research has been done on other private sector teachers. In seminar on Thursday, Peercy herself spoke to us via webcam and discussed her research methods, qualitative and inclusive of self-study. The most interesting part of the conversation was that she and the participants “co-generated knowledge” involved in this study. Until the teachers involved in the study started discussing what was happening with other teachers, they didn’t necessarily realize that self-care was what they each were missing to counteract their stress.

I also read Piaget’s Theory of Development and I also have a few extra associated readings that I have not attended to yet. I will likely follow up later on these, but what I will mention now is that I was really challenged by Piaget. I have never read anything in the field of development, psychology, cognition, etc., etc.!

In terms of Greek this week, we translated an adaption of Herodotus. I fervorously studied principal parts and subjunctive forms for yesterday’s quiz...but it ended up just being more Herodotus.

Personal Reading

Empress (Shan Sa). I’m about halfway through this novel. At first I was disinterested by it, but the pace picked up pretty quickly and the dynamics of the Inner Court during the Tang Dynasty became fascinating to me. I’m pretty hooked on it now.

The Academic Self (Donald Eugene Hall). I’ve only read the introduction, but I’m also hooked on this read. So far, it’s just been a commentary on the struggles of life in academia. That’s of course relevant to me, so I’m looking forward to continuing through and posting some reflections every once in awhile.

“Gin, Sex, Malaria, and the Hunt for Academic Prestige” (Charles King). I loved this excerpt from King’s book regarding the adventures of early anthropologists and how their studies influenced not just anthropology, but social science at large. My biggest takeaway from this reading is the length of which an academic’s work is an extension of his or herself. Margaret Mead wrote in a letter: “I’m more than ever convinced that the only logical place for the anthropologist is in the field — most of the time — for the first ten years, or even fifteen years of his anthropological life.” To me, Mead’s use of “logical” indicates urgency, and this reminds me of myself; I have often felt an urgency to needing to be on campus, in classrooms, among library shelves. As anthropologists must be in the field, academics must be in the academy.

I’ve read even more this week, undoubtedly, but I’m content to wrap up here. This weekend, I want to do more than what is expected of me and meet progress towards my goals. For today, I have to complete my Piaget readings, write discussion questions, and hopefully finish two abstracts so I can review them with my advisor and submit them to their respective conferences! I’m so excited!

0 notes

Text

Little House: Revisiting a Childhood Classic

To a girl who grew up in the 90s in New Jersey, the Laura Ingalls Wilder’s America, with her family constantly and directly affected and impeded by their environment and at times struggling just to survive, is an alien one. But in another sense, it is a very appealing picture. The Ingalls family were one another’s only entertainment, often only company, and though we often picture old-fashioned families as very stern, the Ingalls’ story is one filled with song, laughter, and love. Irecently reread this series after about a decade and a half, and it was a totally new experience. I engaged with the characters in a way I didn’t think would be possible, considering differences in time and lifestyle, and while I was reading, I felt like I was a member of the Ingalls family.

The series begins with Little House in the Big Woods, which takes place in the Big Woods in Wisconsin. This book centers around the Ingalls homesteading, and is probably the ‘coziest’ of the books, as it doesn’t touch as much on the dangers and difficulties of survival as much as the other books do. Laura, her older sister Mary, (and their baby sister Carrie, included in the story though chronologically not born yet), alternate playing and helping around the house, sometimes combining the two, and spend their evenings being entertained by their Pa’s fiddle and vivid storytelling. While living in Wisconsin, the Ingalls were near their cousins and grandparents, so we also get a glimpse into what it was like visiting family and hosting social visitors in this time period.

Growing up, this was my favorite book in the series and has had a massive influence on who I am as a person. I love gardening and homesteading-related hobbies. I love to sew. I hope one day to own enough land to grow the majority of my own produce, and to preserve and store it as the Ingalls did. But more than the influence it had on me, I treasure the impressions it left me with as a child. The lively family in this story is nothing like how they appear in photographs - stern, and grayscale, their clothes restrictive and mouths tight. The young Ingalls family read just like any other family - loving, interdependent upon one another, and truly pleased with their lot in life.

Little House on the Prairie, technically the third book and the namesake of the TV series based loosely on the books, was the second book that I read during my re-read. I chose to omit the books centering around the childhood of Almanzo Wilder because when I initially read the series as a child, I had no idea they even existed. (I plan to follow up with them in future.) Little House on the Prairie chronicles the events of 1869-1870, in Kansas, where the Ingalls moved, following rumors that the nearby Indian Territory would soon be settled. Moving in a covered wagon from the Big Woods, the Ingalls suffer a number of hardships that come in as a stark contrast to those in the first book. One such is the “fever n’ ague” that the family comes down with (later identified as malaria) which puts them out of commission while a neighbor, Mrs. Scott, cares for them along with her own family. Mrs. Scott is one of a few companions of the Ingalls family in this book, another being Mr. Edwards, a bachelor from Tennessee, who later on plays “Santa Claus” for the children. At great risk to themselves, the Ingalls’ neighbors weave into the story by helping them through times that the Ingalls mightn’t have gotten through on their own. In 1870, the government announced that the land would not be open to settlers, and so the house that Pa Ingalls built on the land, and all of the work he’d done tilling the field came to nothing, and the family packed up to move East, closer to ‘civilization,’ where the girls could get educated.

I have to say, this particular re-read was the most incongruous to my memory. I may have conflated it with the following book in my mind, but the easy laughter and confidence of the Big Woods book is gone in this one. Pa Ingalls comes across as a more imposing, decisive character; moving his family from place to place on nearly no notice. Though the trek certainly was fascinating, and brings back old memories of playing Oregon Trail, I didn’t enjoy this book nearly as much as I expected to--ruined by my own memories and ideas about it, I guess. One thing I will say is that I grew an unexpected and truly fierce love for Jack the dog, though. Jack is the Ingalls family companion, and though he squares off against mountain lions and bears in the Big Woods, his protectiveness and stalwartness along the trail to Kansas is incredibly endearing, and his near loss is heartbreaking. (In real life, it wasn’t a heartbreaking near-loss, but an actual loss, and Jack didn’t journey from Kansas to Minnesota with the Ingalls.)

On the Banks of Plum Creek is what I had been expecting from Little House on the Prairie: community, family, adventure, and history, all within the setting of an untouched landscape in Minnesota. Living in a pre-“built” dugout home near the banks of Plum Creek, the Ingalls begin working on their wooden, above-ground home, while also gathering wild grass as hay for their horses and beginning again to till the land. Mary and Laura also go to school for the first time in this book, and the infamous Nellie Oleson is introduced. Nellie, I think, is a more infamous TV character than in the book, where she comes across as your average schoolyard bully, but Laura makes you hate her either way. Nellie is a shopkeeper’s daughter from New York State, and she makes sure everyone knows it and how many advantages it's given her. Rubbing her considerable wealth in everyone’s face, Nellie hosts a “town party” and invites the “farm girls” to join, almost for the purpose of flaunting her resources. Laura’s resulting jealousy inspires her to host her own, more fun party later in the year.

Unfortunately things take a turn, and a swarm of Rocky Mountain locusts literally wipe the traces of the Ingalls’ entire year's work from the earth, leaving them in debt, without food, and a little later, trapped by a snowstorm. Pa goes missing just before the blizzard, and is gone for two days before the blizzard lets up and he can make his way home--apparently having been trapped behind a hill only a few hundred yards from home.

Gosh this book was exciting, and immersive enough to get me saying “gosh.” As Laura ages and the Ingalls’ lives become more and more complicated, the story reveals more about America’s past and the private lives of citizens in the late 1800s than I could have imagined. The humanity and relatability of these characters is something I never would have applied to the early settlers of America’s farmland if I hadn’t read them.

The following book, By the Shores of Silver Lake, follows the Ingalls’ life in De Smet, South Dakota and introduces the fourth Ingalls child, Grace, as the baby. With ‘baby’ Carrie now getting a little older, she is responsible for helping around the house like Laura and Mary were, and is a more apt playmate for Laura as time goes on. However, this book opens with the surprise that Mary has gone blind from her illnesses previously mentioned in the other books, along with a bout of scarlet fever. (Mary’s blindness was later theorized to be due to a thyroid disease, and diabetes that plagued the entire Ingalls family.) Along with Mary’s sight, in this book, we lose Jack, a device Laura moved to this story to help signify the change from childhood to young adulthood. Jack’s peaceful death the day before the family’s long journey to South Dakota is sad, but they give him a wonderful last day filled with his favorite foods and games.

We gain some insight into Laura’s story-telling ability when Pa tells Laura to “be Mary’s eyes” and Laura becomes responsible for describing to Mary the many sights of their new home, and the move, and even the train that the family takes and its passengers. The train is also an exciting part of this story, and begins the relationship throughout the series between the train’s advancement, and America’s encroachments over unsettled land. Pa Ingalls even gets a job working for the railroad company as a paymaster, and the family is able to winter in the surveyor's house, making friends with the local Boast family and hosting workers and pioneers. The Ingalls home became almost an inn during that time, making the family a great deal of money by charging 25 cents for meals and board overnight, and thus begin saving to send Mary to a college for the blind that their former Reverend told them about on a visit. This story is the first to truly engage in the technological advancements and travel capabilities of America’s settlers. The Ingalls not only get visits from family, but make friends and see old ones as they travel across the country, settling in different states.

In The Long Winter, we not only get a true scope of the hardships faced by a family genuinely on their own as far as resources go, we also begin to get a sense of the small-town communities we know to be a big part of American culture today. Shops, inns, and homes begin to crop up in the area, and the Ingalls family winters in the center of town, to be closer to the train as well as the shops and fellow homesteaders. We also first meet Almanzo Wilder in this story, who in the fictionalized account was pretending to be 21 (actually 19) in order to lay a claim to unsettled land, but in reality was closer to 23 (Laura was 13.) Laura and Carrie attend school as often as possible, but are hindered and ultimately stopped entirely by successive blizzards which bury the town and make the roadsimpassable. Food dwindles and even the innovative methods of stretching their stores fail the Ingalls eventually. The blizzards continue for 7 months, and many throughout the town go without food until Almanzo Wilder shares his seed-grain with the locals, and the trains finally thaw, delivering a Christmas barrel of supplies and donated clothing to the weakened Ingalls’ home.

Despite being one of the shorter books, The Long Winter was certainly drama-packed, and at times I truly was scared while reading it, but ultimately I felt it could have been rolled into Little Town on the Prairie. Undoubtedly one of the most formative times in Laura’s life, this book was one where Laura began to really seize on adulthood and responsibility, often talking about protecting her younger sister Carrie, who’s discussed as being a sickly child (despite going on to be quite athletic in her adulthood). Little Town on the Prairie, however, is less focused on hardship and more focused on economy. Laura gets a job sewing for a shop in town in order to pay for Mary’s college education. When she’s let go, the family tries to sell crops, only to have their harvest destroyed by blackbirds. Finally, selling a cow for the money, Mary gets ready to go off to school with Pa and Ma escorting her, leaving Laura, Carrie, and Grace at home.

Again demonstrating her responsibility, Laura leads her sisters in the fall chores, leaving the house sparkling for Ma and Pa’s return. Nellie Oleson befriends the new schoolteacher, Almanzo Wilder’s sister, whose father is on the school board and who had consistently clashed with Nellie in the past, and turns her against the Ingalls girls. The younger students rally behind Laura and torment the new teacher, halting lessons essentially until Nellie joins in the bullying of Ms. Wilder and she eventually leaves. The new teacher helps Laura to achieve her teaching certificate, which Laura wants only to earn more money for Mary, and not because she wants to be a teacher (which she makes clear she does not). Around the same time, Almanzo Wilder begins walking Laura home from church, which Laura seems not to fully understand, but comes to appreciate. At the end of this book, Laura is offered a teaching position in a nearby town, and she prepares to move away from home for the first time.

I have to say, the minute Almanzo enters the story as Laura’s suitor, I began to get giddy. Laura’s narration seems almost willfully naive about his romance attempts, and I found myself rooting for their relationship hopefully, despite knowing that in reality, the couple were married until Almanzo’s death at 91. This feeling intensified in the following book, as Almanzo became Laura’s only rescue from her teaching position and boarding situation.

The book These Happy Golden Years starts out miserable, with 15-year-old Laura being driven by her Pa out to the teaching position from the previous book. Laura boards with the Brewster family, who, unlike her own family, allow animosities and arguments not only to surface, but to come to light in front of her. Mrs. Brewster begins with the silent treatment, but rapidly progresses to shouting at Laura, her husband, and anyone who will listen to her. Eventually, Laura wakes up to the sound of the Brewsters arguing because Mrs. Brewster was standing over her sleeping husband with a knife and he woke up. Almanzo Wilder, fond of Laura and having gotten permission from her Pa, appears each weekend to take Laura home. Throughout the season, Laura proves to be a good teacher; eventually gaining the respect of her students (some of whom were older than she was) and completing her school term, earning $40 for Mary’s college fund. When Laura returns to town, however, Nellie makes a move on Almanzo.

I have never hated anyone as much as I hated Nellie Oleson while reading this book. Nellie, in previous books, boasted about getting whatever she wanted from boys, often flirtily stealing their candy and gifts for other girls, and frequently mentioning that she wanted to go for a ride with Almanzo Wilder and his beautiful horses. Nellie gets her wish, and Almanzo takes her along on a few of his rides with Laura. Laura is eventually able to trick Nellie out of these rides by urging the horses to go faster and scaring Nellie out of repeat trips. Shortly afterwards, Nellie moves back to New York State due to financial hardships, and around the same time, the Ingalls are visited by a relative. Laura’s Uncle Tom, Ma’s brother, comes bearing tales of a terrifying trip to try to mine gold in the Black Hills. Laura later takes a short job helping a family with housework on their homestead, returning for a summer visit from Mary, and to attend singing classes with Almanzo. On their last day of class, Almanzo proposes to Laura, almost casually, and she accepts. On his next visit, he gives her a garnet ring with pearls, and her first kiss. A few months later, Almanzo finishes building their house, and asks if Laura would mind a quick wedding, so that his mother and sister don’t take over and host an enormous one. Laura agrees, and the two are quickly married by Reverend Brown, have a wedding dinner with Laura’s family, and settle into their marital home.

Maybe it’s the effect of having my own schoolhouse love in my life, but Almanzo and Laura’s three-year courtship took my breath away. In a time where most girls are more restrained, Almanzo admires Laura’s bravery and sense of adventure, and while she doesn’t admit much of her own admiration, Laura behaves possessively of Almanzo almost from the start. When Almanzo and Laura kiss for the first time, and Laura tells her parents about her engagement, I was just about jumping with joy, which was really embarrassing, because I was on the subway. It’s impossible not to feel caught up in their love, which is another thing that confronts expectations about old-fashioned families and courtships. Sure, there were fewer fish in Laura’s sea, but it’s obvious from the first time they walk home from church together that Laura and Almanzo were right for one another--just enough thirst for adventure and freedom, just enough seriousness and responsibility. Laura doesn’t want to be a “farm wife,” but promises Almanzo a few years of ‘trying it out,’ hence the title of the next book, The First Four Years.

The first four years of the Wilders’ marriage do not go very smoothly. Almanzo becomes briefly paralyzed, a condition which would continue to hinder him throughout his lifetime, and the environment and loans take their toll on the family’s resources. Much of the material in this book is more adult-oriented than the other books, but not by much. It was never finished by Laura, or edited by her daughter, Rose Wilder Lane (one of the founders of Libertarianism), but was found by Lane’s adopted grandson and subsequently published, and thus is less poetic and polished than the other books.

Unfortunately, the first crop of wheat the Wilders raise is destroyed by hail, and Almanzo mortgages his homestead claim. What they grow on the claim helps to pay for some of their debts and supplies, and Rose Wilder is born in December following Laura’s confusion at her own illness, which turned out to be her first pregnancy. Almanzo and Laura both get diptheria, and Almanzo subsequently struggles with physical disability. As he can no longer work all of his land, they sell their claim and move to their first home. Heat destroys their next crop, but they stay afloat with a flock of sheep Laura invests in. Hot winds destroy the harvest the following year as well, and their son is born in August, but dies a few weeks later, unnamed. At the end of the story, their house burns to the ground, but the story ends on an optimistic note, and the Wilders move to Mansfield, Missouri, where they lived out the rest of their days on a successful dairy farm.

While I was disappointed by The First Four Years because I’d hoped Laura and Almanzo lived joyfully together ever-after, it was incredible to see how the young family faced their struggles. While Laura’s family was never far off, while they lived in South Dakota, the Wilders were ultimately independent during this time, occasionally trading help with neighbors and family. I was also a little bummed to find out that the (to me) infamous Rose Wilder Lane was actually Laura Ingalls Wilder’s daughter, but even this brought some revelations. Most of the struggles that the Wilder family, and to a certain extent the Ingalls, faced were made worse by government intervention, or lack of government protection, and it’s easy to see how Lane could have gotten the impressions on which she based her ideology. As a story arc, including The First Four Years in the Little House series makes it somewhat anti-climactic, with no real solution for the problems set up by this book, and no sequel, (after Almanzo’s death, Laura stopped writing) this story, for me, is a bit of a downer. However, knowing the historical fact of the Wilders’ happy lives together and the joy which Laura expressed and received from sharing her stories with the nation brings the tail end up again. Rereading these books felt like going on Laura’s adventures with her, and particularly from the perspective of a young adult, framed the incredible courage and strength of will put forth by my peers of over a century ago. It was a unique experience capable of being shared by anyone, which in my mind, is exactly what Laura meant to do--bring the entire world into her little house--and she succeeded.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Blog No. 11

The topic of this week’s readings was environmental hazards and their effects on humans. Miller’s Chapter 17: Environmental Hazards and Human Health describes the different kinds of hazards we face and the ways in which we can assess them. Riskaccording to Miller is “the probability of suffering harm from a hazard that can cause injury, disease, death, economic loss, or damage” while a risk assessment is “the process of using statistical methods to estimate how much harm a particular hazard can cause to human health, or to the environment” and lastly, risk management “involves deciding whether or how to reduce a particular risk to a certain level and at what cost” (Miller 2012, 437). Miller makes the point that risk damage is complicated by factors like media hype that causes people to obsess over unlikely risks such as plane crashes and ignore actual common risks, such as car accidents and heart attacks (437). Another example of this is cancer, which, according to the 2009 President’s Cancer Panel Report, affects 41% of Americans (President’s Cancer Panel 2009). I had no idea that number was so high and I must admit I am very surprised because I don’t directly know anyone who has suffered from cancer, which only serves to speak to my point that cancer is another common danger that people don’t actively think about like they do plane crashes, unless of course they have a strong family history of it, know people with cancer, etc.

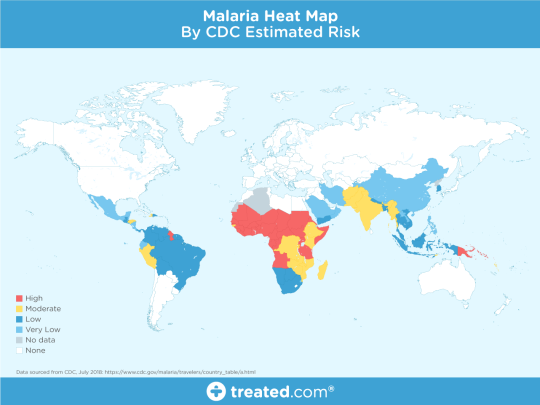

There are many different kinds of hazards. A pathogen is a biological hazard and “an organism that can cause disease in another organism,” such as bacteria and viruses (Miller 2012, 438). Infectious diseases are caused by pathogens that invade cells or tissues and multiply, e.g. malaria and measles (438). A bacterial disease “such as tuberculosis spreads as the bacteria multiple” whereas a viral disease“such as flu or HIV spreads as viruses take over a cell’s genetic mechanisms to copy themselves.” Lastly, a transmissible or contagious disease is transmitted between people such as the flu and measles whereas a non-transmissible disease is not caused by living organisms and cannot be spread, e.g. cardiovascular disease, cancer and diabetes (Miller 2012, 438). Geography has a lot to do with the prevalence, origin, and spread of diseases. Malaria, for example and as aforementioned is an infectious disease caused by a parasite and spread by a specific kind of mosquito bite effectively killing red blood cells of the and leading to fever like symptoms and the deaths of almost 3000 people per day (Miller 2012, 444). These mosquitoes reside mostly in the southern hemisphere in Africa and East Asia, as well as northern Latin America (see image below). Miller explains that “during the 1950’s and 1960’s, the spread of malaria was sharply curtailed when swamplands and marches where mosquitoes breed were drained or sprayed with insecticides;” however, it has made a comeback largely due to tropical forest clearing and development (Miller 2012, 444).

(Treated UK)

In addition to biological hazards, chemical hazards also have harmful effects such as cancer and birth defects (Miller 2012, 446). Toxic chemicals are a kind of hazard that can severely harm human and animal health, e.g. arsenic and lead. Carcinogens are cancer causing chemicals that can cause malignant, cancerous cells to multiply rapidly leading to the development of tumors (446). Another chemical hazard are PCBs which “are a class of more than 200-chlorine containing organic compounds” that can become vaporized when they enter the air and were for a long time used in products such as lubricants, paints, and pesticides (Miller 2012, 446). PCBs were banned in 1977 in response to a litany of studies showing evidence of their cancer-causing capacity. However, because PCBs are so stable, nonflammable and have slow break-down times, they will remain in the environment for a long time (447). This just goes to show how important the role of science is in informing us about how our processes and habits are affecting not only the environment but our health, as explicated by the video, “Body Pollution, Chemical Toxicity” which shows old NBC footage reporting on research that discovered evidence of chemicals known to exist in air and water that were now accumulating in human bodies, i.e. body pollution (Body Pollution, Chemical Toxicity 2007). This was shocking news at the time and likely caused quite a stir in people who up until then likely could not have conceived that chemicals from products such as perfume and hairspray could possibly harm their bodies.

Miller suggests we apply the principles of sustainability to our endeavor to eliminate environmental hazards such as by shifting to renewable energy and resources in order to reduce pollution produced by coal manufacturing (Miller 2012, 462). I realize that biomass at a large scale is environmentally adverse; however, outdoor household biomass use has so much potential and is more efficient than charcoal. I think people are skeptical of biomass because it often involves clear cutting; however, small scale biomass can be created simply from animal and wood waste. An Environmental News Network article titled “New Biomass Plant to Cut Simon Fraser University Greenhouse Gases by Two-Thirds” describes a recent project conducted by the university a few years ago to “divert wood waste from the landfill and help reduce greenhouse gasses at the University by implementing the biomass into the heating plant (ENN 2017). Biomass from wood waste not only creates no new waste, but it also reduces existing waste. In addition, it is completely reliable, renewable, and free and should be implemented more in our strive for carbon neutrality.

Miller’s Chapter 21: Solid and Hazardous Waste discusses what solid and hazardous waste are, their effects, and how we should address and manage them (Miller 2012, 558). Solid waste includes anything solid that we throw away such as industrial solid waste from mining, farming, and manufacturing processes (558). The PowerPoint explains how, despite the ways in which the “industrial, medical, and green revolutions” have vastly improved human life, they have also created new humanly caused/influenced waste pollution, environmental hazards, and public health issues through their linear-high output systems” which are highly polluting and devoid of any biomimicry methodology, to be discussed later (Prof’s PowerPoint). Another example is municipal solid waste or, general household trash. Lastly, hazardous waste such as medical waste and pesticides is harmful to health. There are two major kinds of hazardous waste, organic compounds like PCBs and pesticides and non-degradable toxic heavy metals like lead and mercury (Miller 2012, 559). The UN Environmental Program estimates that more-developed countries output approximately 85% of hazardous waste, with the United States as the greatest producer due to its military and chemical/mining industries, followed by China (Miller 2012, 559).

We essentially have two options when it comes to addressing solid waste, the first is waste management that involves the controlling of waste to reduce environmental impacts without significantly reducing the waste being produced (561). The second option is waste reduction which generally involves a significant reduction accompanied by more intense reusing, recycling, and/or composing methods (Miller 2012, 561). In response to Miller’s Critical Thinking Question #9 on page 579, if I had to select the three most important components to deal with solid waste it would be (1) Significant waste reduction accomplished through methods such as biodegradable packaging, (2) Banning all unnecessary single use products such as Styrofoam cups and plastic bags accompanied by taxation on paper bags to encourage reusable bag use, (3) Imitation of Curitiba, Brazil’s trash collecting program, Camibo Verde which compensates people for collecting and bringing trash to one of the many collection sites throughout the city in exchange for things like fresh produce and bus tokens. With respect to hazardous waste, I would implement taxes on excessive hazardous waste such as PCB’s. I would also ban pesticides that are not made out of wholesome and environmentally conscious materials and provide monetary incentives for farms that adopt natural pesticide methods such as bio-solarization which uses solar energy to manage pests by laying a tarp over soil to trap heat which effectively makes the soil inhospitable for most pests thus eliminating the need for harmful pesticides.

In Chapter 21 Miller defines biomimicry as the heart of the three principles of sustainability and “the science and art of discovering and using natural principles to help solve human problems” (Miller 2012, 581). It consists of two actions, (1) Observation of environmental changes and ”how natural systems have responded to such changing conditions over many millions of years,” (2) Mimicry of these responses and implementing them into human systems to aid us in addressing current environmental issues (581). A relevant case of this is the food web which “serves as a natural model for responding to the growing problem of these wastes” (581). Janine Benyus elaborates on this in her Ted Talk titled “biomimicry in action” where she discusses how important it is that we look to nature for answers to our design issues. She uses the example of spring and the deeply intricate timing and coordination involved in how it is designed (Benyus 2009). Another example she relies on are wasps’ nests which are so architecturally sound that they seem almost human-made. Moreover, Cradle to Cradle Design “is a biomimetic approach to the design of products and systems that models human industry on nature’s processes viewing materials as nutrients circulating in healthy, safe metabolisms” (Wikipedia 2019). This approach tasks industry with the responsibility of preserving ecosystems and simultaneously managing the circulation of organic nutrients in a productive and sustainable way. The article suggests that Cradle to Cradle design can be implemented by virtually any industrial system, big or small, such as the Chinese Government’s construction of Huangbaiyu City that was rooted in Cradle to Cradle design methodology such as by converting rooftops into locations for small, vertical farms (Wikipedia 2019).

Word Count: 1837

Discussion Question: What do you think we have yet to find a sustainable waste management system, given what we know about the effects of landfills, mostly having to do with methane emissions?

Work Cited

Miller, Tyler G., and Scott Spoolman. "Chapter 17: Environmental Hazards and Human Health." Edited by Scott Spoolman. InLiving in the Environment. 17th ed. Belmont, CA: Brooks/Cole, Cengage Learning, 2012.

Van Buren, Edward. “Prof’s PowerPoint Notes.” https://drive.google.com/file/d/0BzKbjVLpnX0RMjVGYUwwZlBXa28/view

Miller, Tyler G., and Scott Spoolman. "Chapter 21: Solid and Hazardous Waste." Edited by Scott Spoolman. In Living in the Environment. 17th ed. Belmont, CA: Brooks/Cole, Cengage Learning, 2012.

Benyus, Janine. "Biomimicry in Action." TED. July 2009. Accessed April 23, 2019. https://www.ted.com/talks/janine_benyus_biomimicry_in_action#t-29010.

"Cradle-to-Cradle Design." Wikipedia. April 03, 2019. Accessed April 02, 2019. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cradle-to-cradle_design.

Body Pollution, Chemical Toxicity. Body Pollution, Chemical Toxicity. June 12, 2007. Accessed April 2, 2019. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0JZPNmkV3zE.

United States. Executive Office. President's Cancer Panel, 2008-2009 Annual Report. 2009. Accessed April 2, 2019. https://drive.google.com/file/d/0BzKbjVLpnX0RelBIVmVUOTl2SUU/view.

"New Biomass Plant to Cut Simon Fraser University's Greenhouse Gases by Two-thirds." Environmental News Network. October 17, 2017. Accessed April 02, 2019. https://www.enn.com/component/content/article?id=52858:new-biomass-plant-to-cut-simon-fraser-university&Itemid=151#39;s-greenhouse-gases-by-two-thirds&catid=8.

"Our Malaria World Map of Estimated Risk." Treated.com UK. Accessed May 02, 2019. https://www.treated.com/malaria/world-map-risk.

0 notes

Text

Timestamp #200: The Unicorn and the Wasp

New Post has been published on https://esonetwork.com/timestamp-200-the-unicorn-and-the-wasp/

Timestamp #200: The Unicorn and the Wasp

Doctor Who: The Unicorn and the Wasp

(1 episode, s04e07, 2008)

The mystery meets the mystery writer.

The TARDIS materializes to the scent of mint and lemonade in the air. If the vintage car in the drive is any indication, it’s the 1920s and Donna’s excited to attend a party with Professor Peach, Reverend Golightly, and the butler Greeves. The Doctor produces his psychic paper, meaning that invitations are all taken care of.

Unfortunately, the party will be one short Professor Peach falls victim to the lead pipe in the library. The suspect is a giant wasp.

The Doctor and Donna are greeted at the party by Lady Clemency Eddison. They also meet Colonel Hugh Curbishley (Lady Eddison’s husband), their son Roger (who flirts with Davenport, a servant), Reverend Golightly, socialite Robina Redmond, Miss Chandrakala, and the famous mystery writer Agatha Christie.

It’s a regular game of Clue.

The Doctor notes the date of the newspaper: It’s the day of Agatha Christie’s disappearance. Her car will be found abandoned and she’ll resurface ten days later with no memory. Her husband has recently cheated on her, but she’s maintaining a stiff upper lip.

Meanwhile, Miss Chandrakala finds Professor Peach, and the Doctor stands in as a police officer with a plucky assistant to boot. The Doctor finds alien residue – Donna’s beside herself that Charles Dickens was actually surrounded by ghosts at Christmas – then teams up with Christie to question the guests while Donna looks about with a magnifying glass from the Doctor’s endless pockets.

Each of the guests has an extraordinary story of where they were at the time of the murder, but there are no alibis. Each is hiding something except for the reverend. The Doctor asks Christie about the paper she picked up from the murder scene, and together they discover the word “maiden” on it.

Upstairs, Donna finds an empty bedroom. Greeves informs her that Lady Eddison has kept the room shut for the last 40 years, after spending six months in it recovering from malaria following her return from India. Inside, Donna finds nothing but a teddy bear and a giant murderous wasp. She attacks it with the magnifying glass and the power of the sun, and the Doctor and Christie arrive to sample the stinger that it left behind.

Miss Chandrakala is murdered by a falling statue. When the Doctor, Donna, and Christie find her, the wasp attacks, but the Doctor cannot find it after it flies off. The guests convene in a sitting room and talk through the events with Christie, but she’s discouraged because she doesn’t know what’s going on. All they have is the clue in Miss Chandrakala’s dying words: “The poor little child…”

Later, she confides in Donna that she feels like the events are mocking her. They commune over lost loves before finding a box in a crushed flowerbed. The Doctor, Donna, and Christie examine the as Greeves brings refreshments, but the Doctor soon realizes that he’s been poisoned by cyanide. A short comedic scene later – complete with ginger beer, walnuts, anchovies, and a shocking kiss from Donna – and the Doctor has detoxed.

The cast gather for dinner, which the Doctor has laced with pepper to test each guest to see if they are the wasp. The lights go out, the wasp appears, and Roger is dead after being stung in the back. Greeves is cleared by being in plain sight during the murder, but Lady Eddison’s necklace (the “Firestone”, a priceless gem from India) is missing.

The Doctor encourages Christie to solve it, knowing that she has the ability. Christie works her way around the assembled guests, uncovering Robina as a thief known as the Unicorn. The Firestone is recovered, but the murderer is still at large.

Christie further (accidentally) uncovers that Colonel Curbishley has been faking his wheelchair-bound disability in order to keep his wife’s affections. She also discovers that Lady Eddison came home from India pregnant, with Miss Chandrakala as a maid and confidante, and had to seclude herself to hide the scandal and the shame.

But, as the Doctor discovers, her tryst was with a vespiform visitor from another world. The alien gave her the jewel and a child, who was taken to an orphanage, and whose identity was uncovered by Professor Peach since “maiden” led to “maiden name”. The Doctor works his way around the room, landing on the reverend who had recently thwarted a robbery in his church. He also notes that the reverend is forty years old, and pieces together that Golightly’s anger broke the genetic lock that kept him in human form. Golightly activated, and the jewel – a telepathic recorder – connected mother and son, including the works of Agatha Christie since Lady Eddison was reading her favorite, The Murder of Roger Ackroyd.

The reverend transforms in rage, and Christie leads the wasp away with the Firestone, believing that this whole thing is her fault. The Doctor and Donna pursue Christie to the nearby lake, realizing that the two are linked. Donna seizes the jewel and throws it into the lake. The wasp follows and drowns, and while the Doctor is aghast at its death, the three of them are relieved that the mystery is solved. Before the wasp dies, it releases Christie from the psychic connection, and the Doctor puts history in motion: The events of the night are erased from her mind and the mystery writer turns up ten days later Harrogate Hotel courtesy of the TARDIS.

The Doctor consoles Donna about the adventure, showing her that Agatha Christie’s memory lived on. She got married again, wrote about Miss Marple and Murder on the Orient Express (which Donna had mentioned during the night’s events), and even published a story about a giant wasp. The last one – Death in the Clouds, filed away after Cybermen and Carrionites – was reprinted in the year five billion, making Agatha Christie the most popular writer of all time.

Donna reminds the Doctor that Christie never thought that her work was any good. He replies simply:

Well, no one knows how they’re going to be remembered. All we can do is hope for the best. Maybe that’s what kept her writing. Same thing keeps me traveling.

With that, they fly onwards to the next adventure.

This story was a rapid-fire mystery, and the power of the acting mixed with the pace kept it entertaining throughout. Fenella Woolgar’s turn as Agatha Christie was well done, mixing her intellect and modesty about her craft with the pain and tragedy of her husband’s betrayal. I particularly liked Christie’s gradual awakening to the Doctor’s alien nature, best evidenced in the scenes where they interrogated the guests using each other’s strengths to unravel the mystery.

Combine that with the chemistry between Tennant and Tate bulldozing through a game of Clue and you have a rather entertaining (if not bloody) dinner party.

The final words that the Doctor uses to summarize his ethos remind me of quote from a recent episode of Outlander. While discussing last words and legacies, a certain character (whose identity I’ll not spoil for fans who haven’t seen the episode yet) said this:

I’d say let history forget my name, so long as my words and my deeds are remembered by those I love.

It doesn’t matter if anyone remembers my name so long as my life made an impact on the people who meant something to me.

Life lessons from the Doctor. Words and ideas to live by.

Rating: 4/5 – “Would you care for a jelly baby?”

UP NEXT – Doctor Who: Silence in the Library and Doctor Who: Forest of the Dead

The Timestamps Project is an adventure through the televised universe of Doctor Who, story by story, from the beginning of the franchise. For more reviews like this one, please visit the project’s page at Creative Criticality.

0 notes

Link

ISAAC BASHEVIS SINGER — the famed Yiddish writer who in 1935 moved from Warsaw to New York and in 1978 received the Nobel Prize for Literature as an American-Jewish author — made his first trip to Israel in the fall of 1955, arriving just after Yom Kippur and leaving about two months later. His relationship to Israel was complicated to say the least. He had been born into a strictly religious family of rabbis and rebetzins in Poland, for whom the land of Israel was the holiest of religious symbols. But he also lived a secular life in 1920s Warsaw, witnessing Zionism overtake Jewish Enlightenment and Bundism as a viable 20th-century political force. In more personal terms, Israel was also the place to which his son, Israel Zamir, had been brought by his mother, Runya Pontsch, in 1938, growing up in part on Kibbutz Beit Alpha and later fighting in the War of Independence. Yet Singer had always avoided every kind of -ism — from Zionism to communism — and so his perspective on the young state of Israel was largely free of the ideology and dogmatism that was prevalent during the country’s early days.

During his trip, Singer published several articles per week in the Yiddish daily Forverts, recording his visit. While these articles sometimes read like touristic travelogues, they reflect Singer’s complex relation to the land of Israel, as both an idea and a place. Israel had been in Singer’s consciousness since his youngest days as a boy growing up in religious surroundings, and it made its way into his work, including some of his earliest fiction, which was published in Hebrew. When he was still living in Warsaw, Singer wrote a novella titled The Way Back (1928) about a young man full of the Zionist dream who travels to the Land of Israel and returns five years later after suffering hunger, malaria, and poverty. In 1948, just a week before the state of Israel was declared, he ended The Family Moskat with several characters leaving Warsaw and moving to pursue the Zionist dream. In 1955, just weeks before his trip, he published an episode of In My Father’s Court (1956) titled “To the Land of Israel,” about a local tinsmith who moves his family to the Holy Land, then returns disappointed to Warsaw, but then, despite everything, goes back. In his memoirs, Singer writes that he considered moving to British Mandate Palestine in the mid-1920s, and in The Certificate (1967), he fictionalizes this in a tale that ends with the protagonist instead going back to his shtetl. As late as 1938, in a letter to Runya sent from New York, he was still fantasizing about the idea: “My plan is this: as soon as I have least resources, and I hope they come together quickly, I will travel to Palestine.” But by mid-1939, these dreams seem to pass into a different view on reality: “For me, in the meantime, getting a visa to Palestine is impossible.” For Singer, it seems, Israel remained, in both the symbolic and literal sense, the road not taken.

And yet, in late 1955, Singer made his first trip to Israel, accompanied by his wife Alma, on a ship called Artsa traveling from Marseille via Naples to the port of Haifa — not as a religious child or an idealistic young man but as a middle-aged Yiddish writer who was beginning to make his name on the American literary landscape. And his journalistic assignment was to capture the trip in short articles that would give Yiddish readers across the United States a sense of what the young state of Israel was like. His son, Zamir, was in New York working as a Shomer Ha’Tsair representative, and both letters and memoirs suggest there was no question of his meeting Runya. Singer was left to his own devices — traveling throughout Israel with Alma, but writing about it as if he were there all by himself.

¤

Singer’s peculiar perspective — with such complex personal history behind it, and such pragmatic goals before it — gives his writing from Israel its unique tone. It is always concerned with the big picture yet remains focused on the small picture. This is evident from the first moments of his trip, even while he was still on the ship. “I think about Rabbi Yehuda Halevi and the sacrifices he made to set his eyes on the Holy Land,” he writes while the ship sails from France to Italy. “I think about the first pioneers, the first builders of the New Yishuv […] How is it that there’s no trace of any of this on this ship? Are Jews no longer devoted with heart and soul to the idea of the Land of Israel?” Singer is looking for proof of the spiritual greatness that the Land of Israel represents, and he wants to see it in the people on board with him — but he soon comes to understand that Israel is not a place of imagination, it’s a place that actually exists. “No, things are not all that bad,” he writes. “The fire is there, but is hidden […] The Land of Israel has become a reality, part of everyday life.”

He begins a keen description of reality still on board the ship. Observing the younger passengers, he describes a now familiar picture: “The young men and women who sit under my window on folding lounge chairs have possibly fought in the war against the Arabs. Tomorrow they may be sent to Gaza or another strategically significant location. But at the moment they want what any other modern young people want: to have a good time.” He identifies, before even arriving on shore, the constant negotiation in Israeli society between war and freedom.

On the ship, he also identifies cultural tensions between Ashkenazim and Sephardim, religious and secular:

There’s a tiny shul here with a holy ark and a few prayer books lying around. But the only people praying there are Sephardic Jews who are traveling in third class or in the dormitories […] It will soon be Yom Kippur, but the ship’s “Chaplain” […] told me there are only three Ashkenazim who want to pray in a quorum.

Singer becomes attached to this group of Sephardi Jews from Tunisia, following them with his eyes and ears:

On Friday evening I wanted to attend prayers. It was still daytime. I went into the little shul and there I saw a kiddush cup with a little wine left inside, and a few pieces of challah laying nearby. It seemed that they had already brought in the Sabbath. The Tunisian Jews have to eat at 6 o’clock and need to pray first.

Later, he goes again, and sees a man praying in a way that moves him. “There, in that little shul, I first came upon the spirituality for which I searched. There, among those Jews, it felt like shivat tsion — the Return to Zion.” He later watches the young Tunisian Jewish women with their head coverings down on the lower deck.

I look for the commonalities between me and them. It seems to me that they, too, look at me to see what connects us. From the standpoint of our bodies, we are built as differently as two people can be […] But as far as one may be from the other, the roots are the same […] There, in Tunisia, they looked Jewish, and for this they were persecuted.

What binds Jews from different corners of the world together, it seems, is their separate but shared experience of difference, even in their native countries.

Singer reports that the mood changes in Naples, where several hundred more passengers board the ship. Now there’s also singing and yelling — the fire he was looking for. But during this part of the trip he also meets a German-Jewish couple who complain bitterly about their life in the Yishuv.

The husband said that letting the Oriental Jews in without any selection, without any inspection, had completely thrown off the moral balance of the country […] The wife went even further than the husband. She said that, no matter how much she wished, she could not stand the company of Polish and Russian Jews. She was accustomed to European (German) culture […] she could not stand the Eastern European Jews.

Singer pushes back against her snobbery. “‘You know,’ I asked her, ‘that your so-called European culture slaughtered 6 million Jews?’” And she responds: “I know everything. But…”

Before he even sets foot in Israel, Singer identifies some of the social difficulties that its citizens face. “It’s hard, very hard, to bring together and bind together a people who are as far from each other as east from west […] Holding the Modern Jew together means holding together powers that can at each moment come apart. Herein lies the problem of the Yishuv.” This observation is less a criticism than a diagnosis. No matter how much binds Jews in Israel — the roots we all share — we have to, at the same time, navigate our differences. In this, Singer acknowledges one of the greatest challenges of a Jewish state.

What seems to really strike Singer when he finally arrives in Israel is the reality that, while built on modern organizational foundations established since the mid-19th century, the country appears as if it had been constructed out of nothing. His access to this reality is, funnily enough, street signs:

Israel is a new country, there’s a mixed population, for the most part newcomers, and they need information at every step. Signs in Hebrew — and often also in English — show you everything you need to know. […] The signs don’t just offer information, they’re also full of associations. . . Every street is named for someone who played a role in Jewish history or culture. Rabbi Yehuda Halevi, Ibn Gvirol, J. L. Gordon, Mendele, Sholem Aleichem, Peretz, Bialik, Pinsker, Herzl, Frishman, Zeitlin are all part of this place’s geography. Words from the Pentateuch, from the Mishnah, from the commentaries, from the Gemara, from the Zohar, from books of the Jewish Enlightenment – are used for all kinds of commercial, industrial, and political slogans.

What Singer seems to like about this is that it makes even less sympathetic Jews have to face their connection to Jewish history and culture. “The German Jew who lives here might be, in his heart, a bit of a snob […] but his address is: Sholem Aleichem Street. And he must — ten times or a hundred times a day — repeat this very same name.” In these signs, Singer sees something that goes much deeper into the reality and paradox of Jewish identity: its apparent inescapability.

Singer quickly connects these prosaic thoughts with the very core of Jewish faith: “As it once did at Mount Sinai, Jewish culture — in the best sense of the word — has brought itself down upon the Jews of Israel and called to them: you must take me on, you can no longer ignore me, you can no longer hide me along with yourself.” In Israel, spirit and religion are not ephemeral feelings; they are viscerally present.

¤