Text

you don't understand I need to talk about shostakovich's antiformalist rayok because HOLY SHIT

okay. so.

I've been wanting to talk about rayok for a while because it's truly mind-blowing what rayok is. hell, it's mind-blowing, considering the circumstances, that we know about rayok. and it's even more mind-blowing what we don't know about rayok. this is probably one of the most impressive works by shostakovich when you really dig into it, just because of how ridiculously multilayered it is. there are scholarly essays and research conducted on this piece because the rabbit hole that is rayok just goes so fucking deep that in order to fully understand it, you need to know a decent bit about music, russian history, the russian language, the relationship between the soviet government and the artistic sphere, etc. I'll mainly be citing manashir yabukov's essay on it in rosamund bartlett's "shostakovich in context," because while there are many publications about this piece, this one is especially comprehensive.

so. what is rayok. WELL.

the antiformalist rayok, simply put, is a shitpost. less simply put, it's a satirical cantata by dmitri shostakovich. it lampoons stalin- and post-stalin era political officials who attempted to interfere with the artistic, particularly musical, culture of the soviet union. shostakovich essentially argues in this piece that political figures have no business policing the arts, especially when they have little to know artistic knowledge themselves.

the way "rayok" works is sort of like a soviet musical SNL skit. there are four characters at a conference on "realism and formalism in music" (sometimes played by the same singer) who are all caricatures of a specific political figure or idea, imitating these figures in a mocking, ridiculous way. the characters are the announcer, who introduces the other three, "yedinitsyn," who represents stalin, "dvoikin," who represents andrei zhdanov, head of the central committee propaganda department of the USSR, and "troikin," who represents zhdanov's successor, dmitri shepilov. shostakovich caricatures each of these figures through references to quotes or speaking patterns, musical quotations, or satirizing their ideologies. for instance, yedinitsyn's (stalin's) verse is often sung in a georgian accent (stalin was a native of georgia), the music quotes the folk song "suliko" (said to be stalin's favorite song), and the text is repetitive without saying anything, parodying stalin's manner of delivering speeches. (an example of a line- "formalist composers are formalist because they write formalist music")

nobody knows quite when rayok was written, or if shostakovich was the sole author. we know that shostakovich often performed it in private gatherings with close friends, but the authorship of the text is disputed. shostakovich wrote the music, but it's contested who wrote the words- shostakovich's friend isaak glikman claimed that shostakovich was the sole author, while another friend, lev lebedinsky, claims he had a hand in writing the text. (many of lebedinsky's other claims have come into dispute.) interestingly, rayok is referenced in "testimony," the highly controversial supposed memoir of shostakovich, which was published before the piece became known to the wider public. it's assumed that shostakovich started working on "rayok" around 1948, and continuously added onto it into the 1960s. along with the piece itself, shostakovich also wrote a hilarious preface (which I'll get into later) and a sarcastic questionnaire to go with it, perhaps as a nod to ideological exams that were required in schools.

so, what does the title "antiformalist rayok" mean? that requires some historical context. "formalism" was a term used to describe art considered unacceptable by the soviet government, and was used most often from the 30s to the early 50s. it originated from the term in academic analysis which meant interpreting a work of art by its "form," or removed from the context intended by the author. formalist analysis was popular in the late 1920s, a more liberal time in soviet history that gave rise to an avant-garde art movement. as such, by the 30s, art considered "formalist" was deemed "art for art's sake," and was derided as "bourgeois" or "western." the crackdown on the arts was part of a larger cultural campaign under stalin, in which he sought to increase the soviet union's industrial production and differentiate it from the west, both culturally and politically. "antiformalist" art, therefore, was the opposite of "formalist"- safe, patriotic, and easily digestible by the masses. such art was also referred to as "socialist realism." "formalist" artists faced increasing persecution that culminated in the "great purges" of the late 1930s, a campaign that sought to eliminate anyone who could be viewed as a threat to the soviet union through exile, arrest, or execution. people who were purged included stalin's political opponents, artists, accused german spies (often in the military), ethnic minorities, farmers who refused collectivization of their land, and civilians suspected of dissent.

still with me? good.

now, the word "rayok." this is a reference to two concepts- rayok shows, and another piece of classical music called "rayok" by modest mussorgsky, a 19th century russian composer. the original word "rayok" refers to rayok shows- a popular form of entertainment in 18th and 19th century russia, in which rotating figures of people or animals would be displayed inside a fairground box with holes that viewers could look through. a performer called a rayoshnik would rotate the figures in the box with a crank and narrate a story, usually of a satirical nature:

mussorgsky's "rayok" took its name from this form of entertainment. like shostakovich's "rayok," it was a satirical piece, focusing on the conservative musical establishment and its patrons, in which specific people were lampooned, similar to the performances by the rayoshniki. by the 1920s, rayok shows were beginning to die out, but shostakovich (b. 1906) displayed an interest in them. as a reference to these performances, he sometimes jokingly referred to his colleagues in letters with exaggerated diminutives, a common practice in rayok shows- for instance, the composer vissarion shebalin was "shebalalishki." (put a pin in that bit about diminutives. it'll be important later.) shostakovich's title "antiformalist rayok" is therefore a reference to the mussorgsky piece and rayok shows, as well as the concept of "antiformalism."

and if you think that's complicated, that's only the title.

so, let's walk through the piece. again, there are four characters- the announcer, yedinitsyn (stalin), dvoikin (zhdanov), and troikin (shepilov). the names "yedinitsyn, dvoikin, and "troikin" correspond to the words for the numbers one, two, and three in russian. some people speculate that these names do not only refer to the order the characters appear, but also the russian school grading system. in russia, students' assignments are graded on a scale of 1 to 5, with a 1 being the lowest grade, and a 5 being the highest. therefore, these names could potentially be a snide remark on the intelligence of shostakovich's subjects of ridicule. elizabeth wilson also notes that the name "troikin" could be a reference to the nkvd's "troika"- a group of three secret police members tasked with sentencing the accused to imprisonment or death, which would line up with troikin's remarks towards the end of his verse.

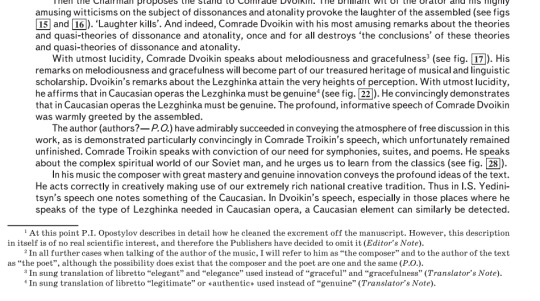

"rayok" starts out with the announcer introducing a panel on "realism and formalism in music." he introduces yedinitsyn, who sings over and over again about how "realistic music is written by the people's composers, and formalist music is written by formalist composers." that's it. that's the whole verse. as I said, there's a suliko quotation to tip us off to the fact that this is stalin (shostakovich even lists his full name in the score as I.S. Yedinitsyin- as in Iosif Stalin, removing any doubt of who yedinitsyn represents). the announcer then says, "let us thank our dearly beloved comrade yedinitsyn for his historic speech, and for his exposition, enrichment, and elucidation of complicated issues of the musical sphere." this is typical shostakovichian sarcasm- as seen in his letters, he tends to over-elaborate a statement to communicate distaste or irony. this statement is even funnier when we consider that yedinitsyn did not "elucidate complicated issues" in his verse, but rather repeated the same thing without elaborating. and of course, the ensemble thanks him for his "historic speech" and "fatherly care." the next character up to the stand is comrade dvoikin, and this requires a LOT of historical context to explain. while yedinitsyn is fairly straightforward, dvoikin and troikin are much more multilayered. so again, bear with me as I go on another tangent about soviet history.

in 1946, andrei zhdanov launched a series of denunciations and censorship against soviet writers and poets. by 1948, this expanded to scientists and musicians, in a period known as "zhdanovshchina." among the composers denounced during zhdanovshchina were big names like shostakovich, prokofiev, and khachaturian, as well as a little-known georgian composer named vano muradeli. muradeli had written an opera called "the great friendship," which had come under fire because he had written his own lezghinkas (a kind of caucasian folk dance) for the opera, instead of incorporating "authentic lezghinkas" instead. shostakovich, as one of the most prominent composers to be attacked during zhdanovshchina, was particularly targeted. many of his works were censored, he was fired from his teaching positions at the leningrad and moscow conservatories, and he was pressured into denouncing his own music, resorting to writing banal film scores and ideological pieces to make a living. while no composers were arrested during zhdanovshchina, it still took a heavy toll on many of their lives, shostakovich included. worse yet, after ww2, a wave of anti-semitism in the soviet union began to take hold around the same time, impacting many jewish artists and professionals. some were assassinated, including solomon mikhoels, the father-in-law of mieczyslaw weinberg, a composer and close friend of shostakovich's. (weinberg himself would be arrested on false accusations of zionist conspiracy, but was released from prison after stalin's death.)

so, all that being said, 1948 was a really, really bad time in the soviet union. this is likely when shostakovich began composing rayok, as well as some of his other "desk drawer" pieces that would not be performed until after stalin's death, such as the first violin concerto and the "from jewish folk poetry" song cycle (note- while shostakovich was not jewish, he took a strong stance against anti-semitism, which would be more pronounced in his later years).

as such, zhdanov comes under serious fire in "rayok." many of his speeches are referenced, if not quoted word for word, in "dvoikin's" lines, including where he refers to dissonant and atonal music as a "dental drill" and "a musical gas chamber." these criticisms were leveled by zhdanov at shostakovich's music- the second directed towards his eighth symphony. this was a serious insult considering the time period- the 8th was written in 1943, when the soviet union was at war against nazi germany. in his essay, yabukov points out something interesting- after the ensemble laughs at dvoikin's remarks, a transposed instance of the dsch motif- shostakovich's musical representation of himself- is heard, implying that while zhdanov is laughing at him, shostakovich ultimately gets the last laugh by satirizing him in "rayok." dvoikin is introduced as having the "ability to vocalize" as he sings exaggerated arpeggios, a dig at the fact that zhdanov was said to be a good singer. he stresses how music must be harmonic, beautiful, elegant, etc., until the music does a complete 180 from oversaturated, kitschy romanticism into- of all things- a georgian lezghinka, just like zhdanov denounced muradeli over. he suddenly sings obsessively about how "in caucasian operas, there must be authentic lezghinkas," the caricature exaggerating to ridiculous lengths as he sings (and in some productions, dances) the lezghinka, before the announcer gives the floor to troikin.

troikin. troikin. oh boy, troikin.

while troikin is based on dmitri shepilov, soviet minister of foreign affairs during the khrushchev era, he can be read to represent, in general, the disastrous effects of politicians in the musical sphere. troikin is portrayed as a complete idiot, singing to a simple melody about how "the soviet man is a very complex organism." in my favorite joke in the entire piece, troikin sings the names "glinka, tchaikovsky, rimsky-korsakov" three times in a row- romantic-era russian composers whom soviet composers were encouraged to imitate, in opposition to avant-garde western composers. (note- tchaikovsky is a complicated case when it comes to his legacy in the soviet union, but his music was regarded far more positively after ww2 than before it, due to the increase in russian nationalism during the war to boost morale.) during this part, troikin mispronounces "rimsky-korsakov" as "rimsky-korSAkov" each time, singing to a 3/4 time signature (for you non-music people, that's like a waltz rhythm). the mispronounced syllable falls on a downbeat, making it stand out even more. according to lebedinsky, shostakovich once heard shepilov give a speech, in which he listed off the names of classical and romanticist composers that soviet composers ought to imitate. however, he pronounced "rimsky-korsakov" as "rimsky-korSAkov," and shostakovich thought it was so hilarious that he puts it directly into the spotlight in "rayok." (remember covfefe? it's like covfefe.) and FURTHERMORE, during this "rimsky-korSAkov" bit, shostakovich is quoting a song called "we'll tell you" from a film score called "faithful friends." this film score was written by none other than tikhon khrennikov.

who's tikhon khrennikov, you may ask? khrennikov was the general secretary of the composer's union from 1948, all the way up to the fall of the soviet union in 1991. he played a role in the zhdanovshchina denunciations against shostakovich, but later stated he was pressured into it. whatever the case, shostakovich didn't forgive him, and we'll see another multilayered shot at khrennikov a bit later on.

troikin continues to be a hot mess on stage. he begins listing kinds of music that should be written, but gets stuck on "suites," before giving up entirely and switching to a parody of "kalinka," a popular folk song. this in itself is another joke- troikin knows nothing about classical music, so he switches to a folk song associated with socialist realism, but it's like, one of the most basic ones you can think of. and in these modified "kalinka" lyrics, troikin drops two names- "dzherzhinka" and "tishinka."

okay, remember what I said about rayok shows and how the rayoshniki performers liked to use exaggerated diminutive names as a part of their satirical shows? this is an example of that right here. "dzerzhinka" refers to one ivan dzerzhinsky, a socialist realist composer best known for his opera "quiet flows the don," whom shostakovich was on unfriendly terms with- shostakovich had helped dzerzhinsky with the music for "don," which was upheld as a "proper" soviet opera after the denunciation of shostakovich's own opera, "lady macbeth of the mtsensk district," in 1936.

tishinka, of course, is khrennikov once again, but there's another layer here. "tishinka," as yabukov points out, was also the nickname for the transit prison "matrosskaya tishina," or the "silence of the sailors." but shostakovich uses the words "raskhrenovaya tishinka"- yet another triple play on words. "khrenoviy" means "rotten" or "worthless," "ras," in this context, meaning "completely." and furthermore, "khren"- as in "raskhrenovaya" and "khrennikov," means "horseradish," and can be used as a euphemism for "penis." so essentially, shostakovich is saying, "khrennikov is a fucked-up dick."

so, after the kalinka segment, troikin's tone suddenly changes. he begins singing about being vigilant for the enemies, and consequences for those spreading "bourgeois lies," such as being "sent to the camps" and "extra hard labor in the snow." as the verse goes on, his mask comes off. while he may be a complete idiot, he's dangerous. this is a common theme in shostakovich's works- that stupidity breeds danger, and that the comedic and tragic exist alongside one another. as soon as troikin makes these threats, the music picks up again and becomes circuslike, trivializing the "vigilance, vigilance" theme- but also adding a threatening undertone to the humor, as shostakovich gives us a grave reminder that real people indeed suffered consequences under the ridiculous ideologies posed by the figures behind yedinitsyn, dvoikin, and troikin.

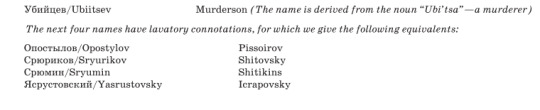

I want to close off this extremely long analysis by mentioning the written preface to rayok and questionnaire by shostakovich. these are somewhat difficult to find both of them. the questionnaire is at the bottom of this page (in russian, but you can autotranslate it) and the preface, in english and russian, can be found here, with notes by scholar elizabeth wilson. it's honestly one of the most hilarious music history tidbits I've ever read, so it's seriously worth checking out. the preface is essentially a fake article about how the script for rayok was "found," and I'm just going to share it in full here because it's just. you have to see it

like. look at these fucking translation notes. dmitri shostakovich made these names. you can't make this up

so like. here it is (in english)

also, this is the best performance of rayok I've ever seen. just. just watch it

would highly recommend reading yabukov's analysis btw. it's WAY more comprehensive than this post, which tbh is just scratching the surface.

#long post#goddamn this took a While#shostakovich#dmitri shostakovich#composers#classical music#history#soviet history#antiformalist rayok#soviet music#classical composer

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Death of Stalin reminds me a lot of Shostakovich‘s Antiformalist Rayok. But that’s quite understandable, I guess.

#the death of stalin#shostakovich#antiformalist rayok#this name is translated in a lot of different ways so#антиформалистический райок

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

obsessed with every time shostakovich writes for voice. his vocal works don’t get as much spotlight as the instrumental ones but godddd

that part in symphony 13 where the soloist’s voice seems to break when he sings “я каждый здесь расстрелянный ребёнок” (I am every child shot dead here) gives me chills every time, and is probably the most powerful part of the entire symphony. the tragedy and rage of the piece is transcending the text and music, compelling even the performer’s voice to waver.

the part in lady macbeth where katerina and sergei are in prison and katerina expresses her devotion to sergei- the man she has no choice but to convince herself to love- as he cheats with sonyetka . absolutely haunting . and then when shostakovich revisits lady macbeth and quotes it in the 8th quartet in 1960, this context is so much more heartbreaking when you consider the themes of betrayal in the opera and the circumstances under which shostakovich wrote the 8th quartet.

you have cycles like songs from jewish folk poetry, the spanish songs, six romances on verses by english poets, the michelangelo and tsvetaeva cycles, etc. where a whole other dimension is added to these texts with the music. you can almost see the scenarios described in the texts played out in your mind, just by hearing them sung and accompanied. the harmonies in “songs from jewish folk poetry” especially stick in my mind, along with the desperation in “the abandoned father” («Цирелэ, дочка!»)

and then there’s the antiformalist rayok and “preface on a complete collection of my works.” gahhhh, shostakovich is so good at satirical comedy. there is so much to these works to dissect, and they’re just so fun. and he’s a talented lyricist, too; his comedic works can be surprisingly personal and vulnerable.

even with socialist realist works he likely wrote out of desperation, like “song of the forests” (a work he allegedly regretted writing according to galina ustvolskaya), there’s no cut corners. he takes his art seriously, even when it exhausted him (as he said himself on the film scores of the 40s). there’s so much in his vocal pieces to examine and they’re some of his most fascinating works imo.

#rambles#shostakovich#dmitri shostakovich#classical music#composer#classical composer#history#music history

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

ok so I just compared shostakovich’s “antiformalist rayok” to “my immortal” in the sense that it’s a horrifyingly intricate shitpost. and I HATE the tired and overused “haha shost is wizard boy” meme but . I came across a “my immortal” joke edit once and it reminded me of this colorized picture of shostakovich, his wife nina, and ivan sollertinsky from 1932

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

I want to talk about Shostakovich’s “Antiformalist Rayok” here so bad but… do you see why I’m scared to

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

remind me to write a long-ass post on shostakovich’s antiformalist rayok after I’m done with my blogging and journal work

4 notes

·

View notes

Note

what r ur favorite shostakovich pieces

violin concerto 1, quartets 3,4,5,8,11, and 15, symphonies 4,7,9,10,13, and 15 (esp 13), antiformalist rayok, lady macbeth of mtsensk, cello sonata, piano concerto 1, and the viola sonata. but my absolute favorite has to be trio 2.

4 notes

·

View notes

Note

1, 4, 29 for soft asks :D

1- As of now, my "comfort music" changes, but it ranges from Shostakovich's "Antiformalist Rayok" to Klaus Nomi's "Rubberband Lazer." My tastes are... eclectic? 4- Diphylleia grayi, or skeleton flowers! I actually have some seeds, imported from Uzbekistan, but they're hard to grow, and I haven't had any luck. They're really cool though; they turn transparent when it rains. I'd love to see them bloom for myself!

29- Night, probably. It's when I'm most awake (like right now; it's 1:59 AM! I have work tomorrow though, so maybe I should try to sleep soon...). I want to be more active in the morning, but it can be really hard to get myself going, and I tend to be pretty sluggish and unproductive until, like, 5 PM, and then I'm usually up until 1-3 AM. Which is bad. But it's a hard habit to break!

4 notes

·

View notes

Note

What are your thoughts on Moscow Cheryomushki (the shosty operetta)?

so I haven’t actually seen cheryomushki (it’s hard to find!) but I have read quite a bit about it. it’s a satire on the housing crisis under khrushchev, and I’ve also read that shostakovich wasn’t a huge fan of it. however, what I find interesting about cheryomushki is that I’ve read it shares a lot of similarities with the antiformalist rayok, a work I’m far more familiar with. (also iirc cheryomushki quotes rayok at times?) what’s neat about this is that rayok was a work shostakovich only performed privately in front of close friends, and is believed to have started working on it around 1948, adding onto it throughout the 50s and 60s. so for a public work like cheryomushki to share some elements with “rayok” is pretty interesting, although we know shostakovich did incorporate elements of private or scrapped works in many of his published pieces. for instance, some of his scrapped opera “the gamblers” shows up in the viola sonata.

#shostakovich#dmitri shostakovich#music history#classical music history#composer#classical composer#soviet history#anyway if you want a weird scrapped shost opera check out orango

4 notes

·

View notes