#armagnacs vs bourguignons

Text

Marie de Berry

The possibilities for political action were greatest when the mother succeeded in taking over as regent. Marie de Berry was married to Jean I, duke of Bourbon, in 1400. The duke was taken prisoner at the battle of Azincourt, and died in prison in 1434. Marie attempted to negotiate his release and the dauphin provided money for his ransom. However, the duke's acceptance of the treaty of Troyes and of Henry VI in 1429 precluded his return home. Their son was only aged twelve in 1415 and Marie assumed his guardianship and the rule of the duchy in order to try to safeguard its territory. Her husband gave her formal permission to exercise power only in his absence in 1417. Over the years that followed, Marie faced considerable problems arising out of the conflict of Armagnacs and Burgundians. Difficulties also arose over the duchy of Auvergne which her father, John, duke of Berry, in 1386 had declared would revert to the Crown if he died without a male heir, but which Charles VI had agreed at the time could pass to Marie and her husband. On her father's death in 1416 Marie occupied the two main strongholds of the duchy, but she was only allowed to do homage two years later, and it was not until 1425 that Auvergne was handed over by Charles VII at the time of her son's marriage to Agnes of Burgundy. Marie retired from power in 1427 when her husband gave his son the right to administer the duchy.

Jennifer C. Ward- Noblewomen, Family, and Identity in Late Medieval Europe- in Nobles and Nobility in Medieval Europe

#xiv#xv#jennifer c.ward#nobles and nobility in medieval europe#marie de berry#valois princesses#duchesses de bourbon#duchesses d'auvergne#hundred years war#jean i de bourbon#battle of azincourt#jean i de berry#armagnacs vs bourguignons#charles i de bourbon#agnès de bourgogne#charles vii

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Changing sides

The first know reference to Alain Chartier is in the household accounts of Yolande of Anjou, Queen of Jerusalem and Sicily, which run from 19 February 1409 to 19 September 1414. His name is included among the "gens et officiers de l'ostel de ladicte dame [Yolande] et ses enfans" ("the members and officers ot the household of the said lady [Yolande]") to whom money is owed, but the accounts do not tell us when he joined the household or what office he filled. In the early stages of the conflict between the Burgundians and the Orléanists, the sympathies of the court of Anjou inclined towards Burgundy; King Louis II and Queen Yolande hoped that John the Fearless would provide them with the material support they needed to make a further attempt to conquer the kingdom of Sicily. Steps towards an alliance between the two houses were taken in 1410 when Catherine of Burgundy was betrothed to the young Louis of Anjou and came to live at the Angevin court, in accordance with the custom of the time. It was not long, however, before events in Paris, particularly the Cabochian revolt in the spring and summer of 1413, led the house of Anjou to change sides.

Following the Peace of Pontoise, negotiated in August 1413, the Burgundians lost control of the capital to the Orléanists or Armagnacs, as they came to be called. Realising that their interests would be best served by severing their ties with Burgundy, Louis and Yolande cancelled the marriage agreement and Catherine of Burgundy was ceremonially returned to her parents in November 1413. The insult was public, the break complete, and years would pass before those two princely houses could be reconciled. A month later, on 18 December 1413, the process of realignment was taken further by the betrothal of Marie of Anjou to Charles, Count of Ponthieu, and third surviving son of Charles VI. In the closing months of 1413, therefore, the court of Anjou lost Catherine of Burgundy and gained Charles of France, who came to live in the house of his future bride. That news must have caused John the Fearless more irritation than alarm, for who could have predicted that less than four years later Charles would find himself Dauphin after the death of his two older brothers ?

From early in 1414, then, the queen's "children", to use the term employed in her accounts, were to include Charles, who was brought up from the age of ten under the tutelage of Queen Yolande and her servants, at a court which had small love for Burgundy, and increasingly supported the cause of the Armagnacs. The circumstances in which Charles was brought up were important, as Malcolm Vale has pointed out:

"Between [Charles' betrothal], as a child of ten, in 1413, and his accession, as a youth of nineteen, in 1422, a governing group had formed round Charles. It was to be the source of many of his most able and most trusted servants. With the future wife of the dauphin came her formidable mother and her servants."

Those servants included Alain Chartier, whose appointment as a royal secretary seems to date from the time when an independent household was formed to serve the new dauphin.

Christopher Allmand - War, Government and Power in Late Medieval France

#xv#christopher allmand#war government and power in late medieval france#alain chartier#yolande d'aragon#louis ii d'anjou#jean sans peur#catherine de bourgogne#marie d'anjou#charles vii#armagnacs vs bourguignons#hundred years war

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

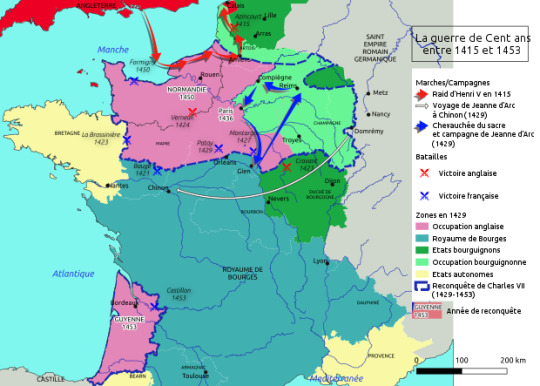

The Maid was born inside the borders of the kingdom since the Meuse river traditionally separates France from the Empire. "If you search for her nation, she is of the kingdom, if you search for her country, she is from Vaucouleurs." Domrémy is divided in two feudal obediences, part of the village being directly in the kingdom, the other, where Jeanne's house is, is attached to the Barrois mouvant. But during Jeanne's childhood the village is mostly torn between the rival ambitions of two political parties. The Valois Duke of Burgundy rules over the countries of here (the duchy) as well as over the countries of there (Flanders) and the strategic road which links them crosses the Meuse Valley. Louis of Orleans, count of Porcien and Valois, advances his pawns in the region in order to cut the States of his adversary in two, and has been trying to unite Lorraine to the kingdom. Metz or Neufchâteau go under a royal safekeeping ensured by Orleans troops.

Jeanne's father is an Armagnac notable. The Maid's childhood is scarred by lootings from Burgundian troops, which really scared her. Jeanne denies any paternal influence in her political formation, which she attributes to her voices who love the king of France. From this moment, she hates the Burgundians. It is in her village that she hears about the imprisonment of the duke of Orleans after Azincourt, about the murder in Montereau (a disaster for which she doesn't believe the dauphin to be responsible), and about the treaty of Troyes (which she doesn't know too well, it doesn't deny the legitimacy of Charles VII). In Domrémy, everybody is Armagnac, except for Gérardin d'Epinal, whose head she would have gladly cut off if they hadn't been companions. The little boys of the village often go together to confront the children of Maxey, in Burgundian land, but little girls don't go.

Her mission starts during the Lent of 1429 at the moment when Orleans, besieged for eight months by the English, risks assault or capitulation. As the actual capital and symbol of the party, Orleans is the other body of Duke Charles, prisoner in England. Can it be fathomed that the English could hold both the body and the city ? The capture of Orleans would be the end of the party, because the duke would never be able to pay the ransom. In a way, the fall of Orleans would have greater consequences for the Duke's partisans than for the kingdom. Jeanne's mission is made of two to four parts. The first is the liberation of Orleans (proving she is sent by God), the third is the liberation of Duke Charles. In other words, Jeanne's mission is equally shared between the king (two duties: the Sacre and the expulsion of the English) and the duke. Charles is the "good Duke of Orleans", a title that isn't universally acclaimed at the time […] She envisions, on various occasions, to exchange him against English lords, to have him brought back by miracle, even to wage war in England to recover him. She has good will for him and for his interests.

A medieval party is first based on the clients of a prince whom they want to bring to power in fortunate times, or else defend. Jeanne's relationships with the prince's biological family are numerous. Dunois, Charles of Orleans' bastard half-brother, is the king's lieutenant in the Loire Valley. Some chroniclers, especially in Burgundy, think Baudricourt sent Jeanne to Dunois in order to save the city. The Maid likes even more the handsome Duke of Alençon, Charles's son-in-law. She goes to Saumur to visit his young wife Jeanne (daughter of the former queen of England who was a daughter of Charles VI) and promises her the safe return of her husband. She will indeed save his life during the campaign. Finally, she enters the cities of the apanage at their side. Duke Charles had married a second time with Bonne of Armagnac in 1410. Jeanne frequented the count of Armagnac and Thibault of Armagnac lord of Termes, who was a witness of the second trial in 1456. Also, Bonne Visconti, Charles's cousin, wrote to "the devout Jeanne sent by the King of Heaven" in order to recover her Milanese lordship.

(Dunois)

Blood and alliance structure the party. But spiritual parentage also play a part. Jeanne has excellent relations with the Laval family, whose grandmother is the widow of Du Guesclin, who was godfather of Louis of Orleans. She gives her a gold ring, a link between the first saviour of the kingdom and the second one. She herself is the godmother, in the Orleans lands of Château-Thierry, of children of loyal subjects (of the king or of the duke ?) whom she names Charles. It is the name of the duke as well as that of the king.

Colette Beaune- Jeanne d'Arc

#xv#colette beaune#jeanne d'arc#armagnacs vs bourguignons#hundred years war#louis i d'orléans#charles i d'orléans#prince des poètes#dunois#robert de baudricourt#jean ii d'alençon#jeanne d'orléans#bonne d'armagnac#thibault d'armagnac#jean iv d'armagnac#bonne visconti#bertrand du guesclin#jeanne de laval

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

#xiv#xv#valentine visconti#house visconti#duchesse d'orléans#armagnacs vs bourguignons#hundred years war#louis i d'orléans#charles vi#isabeau de bavière#charles d'orléans#jean d'orléans#philippe d'orléans#marguerite d'orléans

0 notes

Text

The campaign of propaganda against Valentina Visconti

Irritated by her sister-in-law's calming effect upon the troubled king (while she was rebuffed frequently by him), it seems that Isabeau set to besmirching Valentina's good reputation. Valentina was Italian, and, "as everyone knew", Italy was a nation of poisoners and sorcerers. Charles's illness was reinterpreted; no longer a judgement upon the behavior of his uncles or the misgovernment of his advisers, the unfortunate king was recast as the victim of Valentina's sorcery and enchantment. A rumor started to circulate to the effect that Valentina had bewitched the king; she was the cause of his illness and the obstacle to its cure. As it was rumor there was no need to prove such a claim; its mysterious nature bilked direct proof or formal demonstration, and Valentina's enemies were able to condemn her without a tribunal. To this a concomitant rumor was pressed into service: the classic tale of a poisoned apple and the death of a little prince. Valentina's enemies leapt into the fray to exploit the sad death of her young son Louis in September 1395. It was whispered that she had planned to remove the young dauphin but that instead her own son, who was playing with the other royal children, ate the tainted fruit and died of poisoning. The story was picked up by Froissart, keen to deride a woman whom he believed to be ambitious with aspirations above her station.

Ambitious Valentina is a them that crops up from this time and one that Jean the Fearless of Burgundy recycled on the occasion of his Justification for the murder of Orleans. It was a "known fact" (the rumor reported) that upon Valentina's departure from Milan to marry Louis of Orleans, her father, Giangaleazzo, bid her a fond farewell with the words: "Adieu, belle fille! je ne vous vueil jamais veoir tant que vous soyez royne de France." (Good-bye, beautiful daughter! I do not expect to see you again until you are queen of France!) [..]

Initiated by the rumor of evil spells linked to and fueled by the "known" sorcery habits and nefarious aspirations of Valentina's father, Isabeau's bespoke campaign of propaganda against her sister-in-law aimed to remove Valentina's considerable potential for influence by ensuring that she would have no further personal contact with the king, the princes, the people, the conduct of the business of the kingdom, or to take any action which might be contrary to Isabeau's projects and ambitions. Valentina was to be disloged from court, distanced from Paris, and relegated far beyond the center of political decision making. With Isabeau's campaign, Valentina was reduced to powerlessness and separated from the royal family and her allies. Eugène Jarry expresses well Isabeau's strategy:

"Isabeau did not forget the duchess of Orleans' influence over the mind of the king. Her plan was mapped out: it was absolutely necessary to remove the daughter of the duke of Milan. This outcome was achieved by the most cowardly of schemes. The outburst of negative public opinion against Valentina was too precise not to have been stirred up by interested parties."

Here Jarry links public opinion to interested parties. Isabeau was not the only interest party; the house of Burgundy carried its share of responsibility even though Burgundy was content enough to allow Orleans to divert himself with his Italian dreaming. Philippe was cordial and welcoming to Valentina, but his political reality dictated that he needed to work toward removing Orleans from all participation in government. Burgundy's wife, Marguerite of Dampierre, countess of Flanders, was of a mind to assist Isabeau in blackening Valentina's reputation. In taking control of the government in the wake of Charles's first episode of insanity, Burgundy had positioned Marguerite to steer the young queen in the interests of their House. From 1392, Marguerite jealously guarded her pre-eminent position in Isabeau's court, and no one could gain access to the queen without her consent.

[..]

Collas claims that Marguerite had been greatly put out by Valentina's arival and her subsequent drop in status; she was henceforth the middle-aged sister in law of the defunct king while Valentina was the cherished younger sister-in-law of the current king.

The mud stuck and, for her own safety, Orleans removed Valentina from court. Froissart records that such were the murmurings of the public that had Valentina not withdrawn she might have been attacked and lynched by a Parisian mob that believed she meant to poison the king and his children.

Zita Eva Rohr- True Lies and Strange Mirrors: the Uses and Abuses of Rumor, Propaganda and Innuendo During the Closing Stages of the Hundred Years War, in Queenship, Gender and Reputation in the Medieval and Early Modern West

#xiv#zita eva rohr#true lies and strange mirrors#isabeau de bavière#queens of france#charles vi#valentine visconti#louis i d'orléans#giangaleazzo visconti#jean i de bourgogne#marguerite de dampierre#armagnacs vs bourguignons#hundred years war#reputation and propaganda

7 notes

·

View notes