#as a possible point of comparison to the development of trinitarian language

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Note

Regarding other non-trinitarian groups, I would not consider Oneness Pentecostals and Arians to be theologically Christian either, though again, as far as anthropology goes, I think it makes sense to place them in the "Christian" category. Same goes for various other non-trinitarian religious groups that emerged from Christianity (Jehovah's Witnesses, La Luz del Mundo, etc.). I might not consider myself to be a sibling in Christ with y'all or these various other groups, but I don't deny we have a common history.

Regarding pre-Nicene Christianity, I feel like the question implies that the Trinity was entirely unheard of before the Council of Nicaea, which is not my understanding of Christian history. Even before Nicaea, we still have the Trinitarian formula and the word Trinity, and while a lot of the explanatory language isn't quite what we're familiar with (e. g. iirc Justin Martyr uses some slightly different wording than what most modern orthodox Christians would be accustomed to), the underlying ideas are very much there. Based on what we do have, I don't think it's too much of a stretch to say that the idea was there even if the Nicene Creed itself wasn't there yet.

I also think it's worth bearing in mind that prior to Nicaea, the Church spent a lot of energy just. trying to survive. While persecution was at times more localized, and some government officials were more tolerant than others, this was still the Church under such delightful characters as Nero. That doesn't mean Church councils didn't happen (The Book of Acts describes the Council of Jerusalem, for example), but most of the pre-Nicene councils were not on the same scale as Nicaea (which makes sense; when you're facing off-and-on persecution, gathering a significant number of your religious leaders from across the Roman world into one township is pretty dangerous).

In addition, it's also worth considering that the issues facing the Early Church in, say, the 1st century are not the same as the issues facing the Early Church in the 4th century. We see examples of the questions they were facing early on in other texts (e. g. "What is the role of the Jewish Law in the Christian life?" throughout the New Testament epistles, "Are Christians atheists and/or cannibals?" in Justin Martyr's Apology, etc.). So I'd posit another reason why we don't see the exact language we see from 325 onward is because the questions being asked (from both inside and outside the Church) looked different.

What's more, I recognize that I'm approaching this issue as a Christian with a couple thousand years' worth of biblical and theological tradition to look back on. There are God-knows-how-many theologians who have had far more time to think about the best way to word this incredibly challenging theological concept, and I have the benefit of being able to read their work. Christians living before 325 didn't have that, and with that in mind, I'm pretty humbled. I don't know that I'd do half as well as my pre-Nicene theological forebears at articulating these same ideas.

All of that is to say, yes, I would consider pre-Nicene Christians to be Christian. They may not have used the precise language a post-Nicene Christian like me would be familiar with, and they may not have written in detail or at length about trinitarianism, but I don't think that necessarily means they were automatically not orthodox in their understanding of God.

Regarding what LDS theology teaches about Christ's divinity, I genuinely appreciate that clarification, @demoisverysexy. Your clarification led me to this essay on LDS Christology from BYU professor Grant Underwood, which goes into some of the ins and outs of Christ's exaltation, the LDS perspective on His divinity, and a more LDS-inclined reading of Christian history. While I'm still not sold on the view that y'all are theologically Christian, I do want to better understand what y'all believe, even if I disagree with it.

Thanks again, God bless, and Merry Christmas!

mormons are christians

I'm going to have to respectfully disagree with you, anon. There are some key theological points historically shared by the rest of orthodox Christianity that the LDS Church does not share with the rest of Christianity.

(What I am about to say here presumes that by "Mormons", you mean "LDS", since that's commonly how the term is used. I am less familiar with trinitarian Mormon groups such as the CoC, so I don't feel comfortable getting into all that here, and I feel like that's another post anyway.)

((I am also aware that my explanation may be misconstrued as me biting your head off. That's not my intention at all, and I apologize profusely if it reads that way. I've just done a lot of digging into LDS theology and history over the years, and I wanted to give a rundown of why I understand this issue in the way that I do.))

(((This is also about to get really long and unwieldy so. Apologies for that too.)))

The LDS Church teaches a fundamentally different view of the nature of God. Little-o orthodox Christianity is trinitarian. Not going to get into any biblical defenses of the Trinity here, because I feel like other people have explored it in much more depth, but suffice it to say this is a very old and long-accepted doctrine. Protestants, Catholics, etc. are all in agreement here.

By contrast, LDS theology uses the language of three separate beings united in one purpose. This is particularly apparent in the Book of Abraham, which refers to "the Gods organiz[ing] and form[ing] the heavens and the earth" (Abraham 4:1, emphasis mine). In addition, LDS theology depicts God the Father as an exalted man (see the King Follett Discourse for more on that) and ascribes a physical body to Him (D&C 130:22), which is unheard of in orthodox Christianity.

Furthermore, LDS theology teaches a fundamentally different relationship between God and His People. In orthodox Christianity, when we speak of God as our Father, there is an understanding that we are not His literal children in a biological sense (John 1:12-13). Instead, God being described as our Father is one of various images that He uses in order to communicate His love for His people. As another example of this kind of language in action He is also described as our Husband (e. g. Isaiah 54:5, Ezekiel 16:32, Hosea). This is because God's love for us is so vast and so deep and so complete that it is impossible to use just one analogy and encapsulate all of it perfectly. (I'd argue it's also because the magnitude of God's love is what makes all these other forms of love possible. We love because He first loved us, after all.)

In LDS theology, however, this Father-Child relationship language is not an analogy. It's literal. We are the biological spirit children of a Heavenly Father and a Heavenly Mother.

The Heavenly Mother is another aspect of this that is very different from Christianity. In LDS Theology, God is held to be actually male, with a male body and a wife. In Christianity, God is neither male nor female. We may use masculine language to refer to God ("Father", "Son", "He", etc.), and Jesus chose to take the form of a human male, but Scripture also uses feminine language to describe God through the language of motherhood, childbirth and breastfeeding (e. g. Deuteronomy 32:18, Isaiah 49:15, Isaiah 66:13, Isaiah 42:14), and various orthodox Christian theologians have leaned into that language (Julian of Norwich, for example).

I say all that not out of sensationalism or because I want to showcase how "weird" I think LDS beliefs are. All religions are weird (and heck, all of human existence is weird, if we're really honest about it). All of that to say, I'm saying this because it's necessary background to the LDS conception of who Jesus is.

In LDS theology, Jesus is the eldest of Heavenly Father and Heavenly Mother's spirit children (and therefore, our elder spirit brother), who volunteered for the role of Savior in our preexistence. Satan is Jesus' younger spirit brother, who was cast out of Heaven for trying to take away humanity's free will. Jesus was later exalted to the status of godhood after His resurrection.

In the event that someone tries to claim I am making all this stuff up or misrepresenting LDS beliefs, the LDS Church is completely transparent about this aspect of their theology:

"Every person who was ever born on earth is our spirit brother or sister." (Spirit Children of Heavenly Parents)

"In harmony with the plan of happiness, the premortal Jesus Christ, the Firstborn Son of the Father in the spirit, covenanted to be the Savior. Those who followed Heavenly Father and Jesus Christ were permitted to come to the earth to experience mortality and progress toward eternal life. Lucifer, another spirit son of God, rebelled against the plan and 'sought to destroy the agency of man.' He became Satan, and he and his followers were cast out of heaven and denied the privileges of receiving a physical body and experiencing mortality." (Premortality)

"The Savior did not have a fulness at first, but after he received his body and the resurrection all power was given unto him both in heaven and in earth. Although he was a God, even the Son of God, with power and authority to create this earth and other earths, yet there were some things lacking which he did not receive until after his resurrection. In other words he had not received the fulness until he got a resurrected body" (Joseph Fielding Smith)

"And I, John, saw that he received not of the fulness at the first, but received grace for grace; And he received not of the fulness at first, but continued from grace to grace, until he received a fulness; And thus he was called the Son of God, because he received not of the fulness at the first. And I, John, bear record, and lo, the heavens were opened, and the Holy Ghost descended upon him in the form of a dove, and sat upon him, and there came a voice out of heaven saying: This is my beloved Son. And I, John, bear record that he received a fulness of the glory of the Father; And he received all power, both in heaven and on earth, and the glory of the Father was with him, for he dwelt in him." (D&C 93:12-17).

Again--and I cannot stress this enough--my problem with this is not that I think it is "weird". I don't think it is exceptionally weird, and again, all religions are weird, including my own. Something being "weird" isn't enough to make it not Christian.

My issue is that this is significantly different than orthodox Christian theology. Orthodox Christian theology holds that Jesus is fully God, and has always been fully God, even as an embryo in Mary's womb. Again, fully willing to say that the orthodox understanding of the Trinity, God's neither-male-nor-femaleness, and Jesus being eternally fully God, even as an unborn baby, is all pretty bizarre.

Now, there are absolutely places where orthodox Christian denominations and theologians have disagreements about Jesus. Some of those questions are really significant ones too, like the whole miaphysitism vs. hypostatic union debate. But whatever disagreements we have, I am of the firm belief that the question of Jesus' divinity--that He was, is, and ever shall be God--is a pretty fundamental tenet of the Christian faith. For all of our squabbling, Catholics, Lutherans, Baptists, Wesleyans, Russian Orthodox, etc. have all taken that question very, very seriously. Once a religion leaves that behind, I have a hard time accepting that a member of said religion is a Christian.

I'll concede that in anthropological contexts, it's not incorrect to categorize the LDS Church as "Christian" for historical reasons. After all, various aspects of LDS practice and teaching can only be explained through the fact that Mormonism came about as a blending of various 19th century American beliefs with Second Great Awakening-era low-church American Protestantism.

And I also recognize that there are other Christians around here that would take a much broader theological stance over who is or isn't Christian than I do. But personally, looking at LDS theology and comparing it to the rest of orthodox Christianity, I would consider the LDS Church one of several American offshoots of Christianity dating to the 19th century rather than orthodox Christianity-proper.

#((yeah i know it's not christmastide yet but we don't really have a greeting for advent to my knowledge. somebody should get on that.))#as a possible point of comparison to the development of trinitarian language#english used to not have the word 'orange' and so artists and writers used different language to describe it#that doesn't mean no one before the 16th-17th century had any idea that there was such a color as orange#they were just calling it 'saffron' and 'tawny' and 'yellow-red' because they didn't have the word 'orange' yet#i see the development of trinitarian language similarly#just because the language wasn't what we have doesn't mean the idea would have been foreign#anyhow sorry for taking a long time to reply#christianity tag#if you could hie to kolob

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

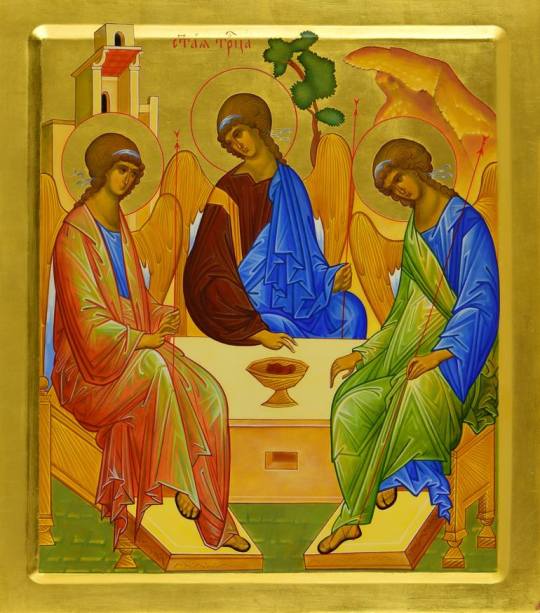

Saints&Reading: Sun., June 7, 2020

Feast of the Holy Trinity

Eastern Orthodox theology is the theology particular to the Eastern Orthodox Church. It is characterized by monotheistic Trinitarianism, belief in the Incarnation of the essentially divine Logos or only-begotten Son of God, a balancing of cataphatic theology with apophatic theology, a hermeneutic defined by a polyvalent Sacred Tradition, a concretely catholic ecclesiology, a robust theology of the person, and a principally recapitulative and therapeutic soteriology.

Ecclesiology[

The Eastern Orthodox Church considers itself to be the one, holy, catholic and apostolic church established by Christ and his apostles. For the early years of the church, much of what was conveyed to its members was in the form of oral teachings. Within a very short period of time traditions were established to reinforce these teachings. The Eastern Orthodox Church asserts to have been very careful in preserving these traditions. When questions of belief or new concepts arise, the Church always refers back to the original faith. Eastern Orthodox see the Bible as a collection of inspired texts that sprang out of this tradition, not the other way around; and the choices made in forming the New Testament as having come from comparison with already firmly established faith. The Bible has come to be a very important part of "Tradition", but not the only part.

Likewise, the Eastern Orthodox Church has always recognized the gradual development in the complexity of the articulation of the Church's teachings. It does not, however, believe that truth changes, and it therefore always supports its previous beliefs all the way back to what it holds to be the direct teachings from the Apostles. The Church also understands that not everything is perfectly clear; therefore, it has always accepted a fair amount of contention about certain issues, arguments about certain points, as something that will always be present within the Church. It is this contention which, through time, clarifies the truth. The Church sees this as the action of the Holy Spirit on history to manifest truth to man.

The Church is unwavering in upholding its dogmatic teachings, but does not insist upon those matters of faith which have not been specifically defined. The Eastern Orthodox believe that there must always be room for mystery when speaking of God. Individuals are permitted to hold theologoumena (private theological opinions) so long as they do not contradict traditional Eastern Orthodox teaching. Sometimes, various Holy Fathers may have contradictory opinions about a certain question, and where no consensus exists, the individual is free to follow his or her conscience.

Tradition also includes the Nicene Creed, the decrees of the Seven Ecumenical Councils, the writings of the Church Fathers, as well as Eastern Orthodox laws (canons), liturgical books and icons, etc. In defense of extrabiblical tradition, the Eastern Orthodox Church quotes Paul: "Therefore, brethren, stand fast, and hold the traditions which ye have been taught, whether by our spoken word, or by our epistle." (2 Thessalonians 2:15). The Eastern Orthodox Church also believes that the Holy Spirit works through history to manifest truth to the Church, and that He weeds out falsehood in order that the Truth may be recognised more fully.

Eastern Orthodoxy interprets truth based on three witnesses: the consensus of the Holy Fathers of the Church; the ongoing teaching of the Holy Spirit guiding the life of the Church through the nous, or mind of the Church (also called the "Universal Consciousness of the Church"[1]), which is believed to be the Mind of Christ (1 Corinthians 2:16); and the praxis of the church (including among other things asceticism, liturgy, hymnography and iconography).

The consensus of the Church over time defines its catholicity—that which is believed at all times by the entire Church. St. Vincent of Lerins, wrote in his Commonitoria (434 AD), that Church doctrine, like the human body, develops over time while still keeping its original identity: "[I]n the Orthodox Church itself, all possible care must be taken, that we hold that faith which has been believed everywhere, always, by all"[2] Those who disagree with that consensus are not accepted as authentic "Fathers." All theological concepts must be in agreement with that consensus. Even those considered to be authentic "Fathers" may have some theological opinions that are not universally shared, but are not thereby considered heretical. Some Holy Fathers have even made statements that were later defined as heretical, but their mistakes do not exclude them from position of authority (heresy is a sin of pride; unintended error does not make one a heretic, only the refusal to accept a dogma which has been defined by the church). Thus an Eastern Orthodox Christian is not bound to agree with every opinion of every Father, but rather with the consensus of the Fathers, and then only on those matters about which the church is dogmatic.

Some of the greatest theologians in the history of the church come from the 4th century, including the Cappadocian Fathers and the Three Hierarchs. However, the Eastern Orthodox do not consider the "Patristic era" to be a thing of the past, but that it continues in an unbroken succession of enlightened teachers (i.e., the saints, especially those who have left us theological writings) from the Apostles to the present day...keep reading

Acts 2:1-11 NKJV

Coming of the Holy Spirit

2 When the Day of Pentecost had fully come, they were all [a]with one accord in one place. 2 And suddenly there came a sound from heaven, as of a rushing mighty wind, and it filled the whole house where they were sitting. 3 Then there appeared to them [b]divided tongues, as of fire, and one sat upon each of them. 4 And they were all filled with the Holy Spirit and began to speak with other tongues, as the Spirit gave them utterance.

The Crowd’s Response

5 And there were dwelling in Jerusalem Jews, devout men, from every nation under heaven. 6 And when this sound occurred, the multitude came together, and were confused, because everyone heard them speak in his own language. 7 Then they were all amazed and marveled, saying to one another, “Look, are not all these who speak Galileans? 8 And how is it that we hear, each in our own [c]language in which we were born? 9 Parthians and Medes and Elamites, those dwelling in Mesopotamia, Judea and Cappadocia, Pontus and Asia, 10 Phrygia and Pamphylia, Egypt and the parts of Libya adjoining Cyrene, visitors from Rome, both Jews and proselytes, 11 Cretans and [d]Arabs—we hear them speaking in our own tongues the wonderful works of God.”

Read full chapter

Footnotes

Acts 2:1 NU together

Acts 2:3 Or tongues as of fire, distributed and resting on each

Acts 2:8 dialect

Acts 2:11 Arabians

John 7: -37-52; 8:12 NKJV

The Promise of the Holy Spirit

37 On the last day, that great day of the feast, Jesus stood and cried out, saying, “If anyone thirsts, let him come to Me and drink. 38 He who believes in Me, as the Scripture has said, out of his heart will flow rivers of living water.” 39 But this He spoke concerning the Spirit, whom those [a]believing in Him would receive; for the [b]Holy Spirit was not yet given, because Jesus was not yet glorified.

Who Is He?

40 Therefore [c]many from the crowd, when they heard this saying, said, “Truly this is the Prophet.” 41 Others said, “This is the Christ.”

But some said, “Will the Christ come out of Galilee? 42 Has not the Scripture said that the Christ comes from the seed of David and from the town of Bethlehem, where David was?” 43 So there was a division among the people because of Him. 44 Now some of them wanted to take Him, but no one laid hands on Him.

Rejected by the Authorities

45 Then the officers came to the chief priests and Pharisees, who said to them, “Why have you not brought Him?”

46 The officers answered, “No man ever spoke like this Man!”

47 Then the Pharisees answered them, “Are you also deceived? 48 Have any of the rulers or the Pharisees believed in Him? 49 But this crowd that does not know the law is accursed.”

50 Nicodemus (he who came to [d]Jesus [e]by night, being one of them) said to them, 51 “Does our law judge a man before it hears him and knows what he is doing?”

52 They answered and said to him, “Are you also from Galilee? Search and look, for no prophet [f]has arisen out of Galilee.”

Read full chapter

Footnotes

John 7:39 NU who believed

John 7:39 NU omits Holy

John 7:40 NU some

John 7:50 Lit. Him

John 7:50 NU before

John 7:52 NU is to rise

8:12 Then Jesus spoke to them again, saying, “I am the light of the world. He who follows Me shall not walk in darkness, but have the light of life.”

Read full chapter

New King James Version (NKJV) Scripture taken from the New King James Version®. Copyright © 1982 by Thomas Nelson. All rights reserved.

#orthodoxy#orthodoxchristian#easternchristianity#firstchristian#ancientfaith#spirituality#bible#gospel

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kimel's review of What is the Trinity - Part 1

At his blog Eclectic Orthodoxy, Fr. Al Kimel has undertaken a multi-part review of my book. He’s a smart and interesting person, and I appreciate a review which is honest and does not pull its punches. It’s a hostile review, to be sure, but I think it may be useful to interact with it. I want to respond to the first installment in this post, as I think this dialogue will bring out some interesting differences between his Orthodox assumptions and my Protestant ones.

This first installment engages very little with the content of the book. Rather it is about me, my alleged shortcomings, and how really I’m not qualified to write on this subject!

…if, on the basis of the title, one is hoping to learn why the Church of Jesus Christ formulated the doctrine of the Holy Trinity, what it means and how it functions in its corporate life, then one is going to be disappointed. This is not to say that the book does not contain helpful information and analysis; but it is to suggest that Dr Tuggy simply misses the evangelical import of the trinitarian dogma. As the proverb goes, can’t see the forest for the trees.

My book is about the origin of the traditional trinitarian formulas, and what we are supposed to think those mean. Obviously, one reason why “the Church,” i.e. the victors in the fourth century struggle, came up with these formulas, is that they thought they were thereby best expressing the theology of the Bible, or least of traditional Christian teaching. I guess Fr. Kimel also wanted to hear about its practical and spiritual values, about how this doctrine functions incorporate spiritual life.

But for me the prior question is: What is it? First we need to get clear about what it is, and then we can inquire about all of the wonderful things that it supposedly accomplishes.

The reason is easily identified. Tuggy is an analytic philosopher, and he reads the relevant literature through the eyes of an analytic philosopher. But the first-millennium theologians who contributed to the formulation and development of the doctrine of the Trinity did not understand themselves as philosophers… Their writings are marked by a terminological fluidity and imprecision that can be more than a little frustrating, as evidenced, for example, by their failure to clearly define words like ousia and hypostasis.

This diagnosis overlooks that almost all Christian analytic philosophers are trinitarians! So whatever my shortcomings are, don’t think they’re going to be explained by my being an analytic philosopher. It seems to me that he is more comfortable with traditional obfuscation than with attempts to clarify, but if truth is our aim, it looks like we need clarity. We must know what is being said, before we know why it is important, and why we should think it’s true. In his view did these ancient bishops find “appropriate conceptuality”? I’m waiting to find out what he thinks that is…

While reading through What is the Trinity? I was reminded of the fourth-century theologian Eunomius. He might be described as the Dale Tuggy of his day. He prized philosophical clarity, logical precision, and syllogistic reasoning. Like Tuggy he was convinced that biblical monotheism excludes the kind of Trinitarian theology then being developed … The Pro-Nicenes accused him of being a logic-chopper, dialectician, technologue. In their eyes Eunomius had sacrificed God’s self-revelation in Christ to the idol of bare reason.

I don’t see the point of such traditional denunciations and dismissals. Seems like the poisoning the well fallacy to essentially just mock Eunomius (or me) as Philosophy Boy. This, while taking pride in the ancient bishops’ philosophical distinctions, as applied to theology. Better to just deal with the biblical issues.

What we see here is not just two conflicting theological positions but the collision of two incompatible religious visions. The Eunomian vision is epistemologically optimistic and deductive; the patristic vision, confessional, apophatic, synthetic. Tuggy is, of course, a very different kind of philosopher than Eunomius, yet perhaps the comparison is neither completely inapt nor uncurious. The Pro-Nicene Fathers would have found Tuggy’s presentation and critique as unconvincing, rationalistic, and offensive as they found the arguments of Eunomius.

As someone who has taught philosophers like Leibniz, Spinoza, and Descartes, it pains me to be described as “rationalistic” or even is especially optimistic. My epistemic stance is more derived from Thomas Reid, and in my view is fairly skeptical. But I think just making use of logic is enough to draw this charge. But it’s just a slur, I think. As to the claim that I adhere to some “religious vision” which clashes with Christianity, of course I deny that. Perhaps the reviewer would like there to be some weird, alien epistemic or religious dogmatism on my part, but this has not been shown. I suspect that he’s just reverse engineering what he thinks my methodology must have been, given my views.

What is the Trinity? Tuggy states that he hopes that his book will equip folks to figure out what they “think about” the catholic doctrine of the Holy Trinity (p. 3). This is a curious way of putting the matter. What “I” think about the doctrine is of little consequence.

To the contrary, what you think those words mean will determine the contents of your beliefs, your actual theology. And this directly affect your actions, prayers, and so on.

What is important is what the doctrine means to those ecclesial communities that teach it as a dogma that must be respected and believed.

“It.” What is it? That’s the main issue discussed in my book: the actual content of these required sentences in the creeds.

If I am considering initiation into, say, the Orthodox Church, I will want to know what Orthodoxy means by its confession of God as Father, Son, and Holy Spirit.

Note the assumption here: that some one thing, some one set of claims, is meant. It’s not clear to me that there is some one content. Hence, all of the attempts by trinitarians to establish what that is.

What exactly am I expected to believe? If I then pose this question to the local Orthodox priest, he will provide me with a succinct summary of the doctrine, referencing creedal, conciliar, and catechetical pronouncements, as well as liturgical hymnody and the consensual teaching of Orthodox theologians, past and present. He will seek to describe the doctrine of the Orthodox Church, as he has received it, as he knows and lives it. This is how doctrine is faithfully handed on.

Here I think were getting closer to the crux of our disagreement.

Who do I think I am, anyway, to be discussing such things? My answer is: just one of these. In the fourth century, the hierarchy of bishops took for itself the privilege of arguing about the content of Christian teachings. This had never happened before. Back in the days of Justin and Origen, scholars and laypeople would engage in conversation an argument with one another, and of course the Bishop was a part of that. As a Protestant, I do not accept the one bishop system as God’s ordained system of church leadership. But even if I did, I would think they had gone too far in making themselves the Supreme Court of doctrinal disputes.

So, I don’t think much of myself, but I do think I have the right to ask what this traditional language means. If you ask an adult to publicly affirm some words, you should expect that he will ask you what they mean, if he does not understand. And here’s the thing: I’m pretty sure that if I just went to the local Orthodox priest and asked him their meaning, I would leave as puzzled as I came. And if that were to happen, I don’t think it would be my duty to just accept that I’m never going to understand these sentences that I have been told to profess.

But this is not Tuggy’s position. He writes as a philosophical and historical critic, as one who has rejected the trinitarian faith as incoherent and unbiblical and hopes to persuade his readers to his point of view.

In this book, no I am not trying to make that case, a case for unitarianism. I’m just laying out the options, ones actually proposed and other conceptual possibilities. Honestly, I think that this does help me side. But in this book I don’t, for example, get into any of this.

To be clear, I am not and have never been “a philosophical and historical critic” of Christianity. I am just a Protestant and have been a born again Christian since 1978. I am a biblical unitarian because after a long and hard investigation, I now see this as a clash between the NT and later traditions. It is now clear to me that the NT teaches that the one God just is the Father (and so, not the Trinity). The Trinity is merely inferred from the Bible, and no one actually made the inference until the fourth century, as I explain in the book. Thus, in my view, the need for Reformation. But I do not and have not ever claimed that all interpretations of trinitarian language are incoherent. Some are and some aren’t; the theories are many. You tell me what your theory is, and then we can discuss its coherence. If you just repeat the creedal formulas to me, we haven’t even started conversing about your actual theological views – we’ve only located them in a rough region, and established your loyalty to catholic authorities.

For the non-believer, as well as most Protestants, there is no Church that infallibly teaches today the faith once delivered; there are only churches and individuals existing in different parts of the world in different epochs of history. All we can do is engage in historical reconstruction.

I agree that there is no infallible church. Just look at all the churches, taking the NT as your standard, and that is where you end up. But in my view, the New Testament is meant for the Christian masses. These books were written to be read out loud to groups of people, young and old, educated and uneducated. And in some sense, they are sufficient for instruction. So no, the Christian does not need to wait around for the historians do their work, he can just get right to it with books that were designed for a person like him. Of course he needs the help of scholars to even read them, and the problem is that the scholars bring their theories with them. So it gets complicated nowadays. And yet, God’s spirit does work to bring people to faith and to new birth.

I do not believe that the diversity of interpretations poses as dire a situation as Tuggy here implies. He overlooks the regulative and grammatical function of Christian dogma. I will address this in a subsequent article in this series. At this point I simply want to point out the level of abstraction of Tuggy’s argumentation: the doctrine of the Trinity is reduced to a set of truth-claims divorced from the proclamatory, liturgical, and spiritual experience that the doctrine is intended to express and form.

“The doctrine” – again: what doctrine? I know the words, but until we nail down an interpretation of them, we cannot discuss the spiritual and practical values of that teaching. I am, yes, interested in truth claims, but I don’t see how this interest divorces theology from corporate Christian life.

Perhaps Fr. Kimel is thinking that the traditional trinitarian language actually can’t be justified by appeal to the Bible, but must be justified on some practical grounds. I’ll see if he goes there in a further installment… In any case, I don’t see how I am in any way “reducing” biblical teaching about God, his son, and his spirit to truth claims. Revealed doctrines have to involve truth claims, of course, but I believe in corporate and individual experiences relating to these matters. And I don’t think such experiences, on the whole, support belief in a triune God! But I don’t really discuss the epistemic value of religious experiences in this little book.

Nor is it possible to determine the truth or falsity of the trinitarian dogma by appeal to the “plain” meaning of the Bible, presumably read according to the criteria of the historical-critical method, for the early Christians did not read the Scriptures as historical-critical scholars. If they had, they never would have found the risen Jesus within our Old Testament. They read the Scriptures with and in the Church, employing typological and allegorical methods and hermeneutical strategies alien to the modern mindset (see “Reading the Bible Properly,” “When Scripture Becomes Scripture,” and “What Does Scripture Mean?“). Who today thinks that Proverbs 8:22-31 attests to the procession of the Son from the Father, yet this was old hat for the ante- and post-Nicene Fathers, as well as their opponents. Ecclesial meaning trumps plain meaning; or perhaps more accurately, ecclesial meaning enfolds, deepens, corrects, and transforms plain meaning.

Overall scriptural hermeneutics is a big subject which is outside the scope of this blog post and of my book. In my view, there is nothing mistaken, unreasonable, or arbitrary about Christians thinking that various Old Testament passages had more than one meaning, and that the christological meanings are only revealed in the first century. And I think it is a plausible view that while inspired apostles can do this, later imaginative people like Origen are doing a lot of mere eisegesis. To me, the New Testament is in a different boat. Apart from the last book, these books are pretty straightforward, and do not admit of esoteric interpretations. Did they read, say, Mark or Romans in a “plain” way? I think they did!

But the handicap in which Tuggy operates is even more severe. Not only does Tuggy stand outside the Christian faith (I know, I know, he will object to this statement, but as an Orthodox Christian I have to be honest about this), but his personal experience of the Christian faith is limited to an evangelical-Protestant form. He has not been shaped by the liturgical and sacramental life of the catholic Church; he has not been immersed in Eucharist nor formed by its symbolic language and graces. Forest and trees.

It is true that I have always been Protestant. The reader will have to judge if this has left me with some gaping epistemic deficiency.

Why is this important? Because the liturgy is the home and matrix of the Trinity. It was the liturgical and spiritual life of believers that ultimately drove the development of the trinitarian doctrine. The Trinity was never just a philosophical conundrum of one and three, which is too often how those in the scholastic and analytic traditions tend to think of the matter. It was always a matter of worship, praise and prayer. Lex orandi, lex credendi.

This sort of rhetoric is not to the point. Who thinks that the Trinity is just a fun little metaphysical puzzle to play around with? Honestly, I’ve met a few people with that attitude, but I have never had that attitude. To me all this stuff is deadly serious, and concerns spiritual matters of the highest importance. I don’t often pontificate about these concerns, you could call them pastoral concerns, but they’re an important motivation. Big topic, though – more than I’ll get into here.

Long before Christians formulated the doctrine of the Trinity, Christians prayed in the Trinity: to the Father, through and with Jesus the Son, in the Holy Spirit.

Yes, and in those days never, ever to a tripersonal God. Fr. Kimel here describes a unitarian-friendly practice of prayer.

Back in my seminary days in the late 70s, I read and reread Robert W. Jenson’s book The Triune Identity. After reviewing the kinds of trinitarian discourse found in the New Testament and the early tradition…

I omit his long quote from Jensen here, because it seems to me that it concerns not the Trinity, but only the triad, the trinity. This is generally what people switch to when they want to focus on the New Testament, because the New Testament never mentions or implies the Trinity. But God, his Son, and his spirit are of course all over the NT.

To “explain” the Trinity all I had to do was point to the eucharistic prayer, any extant eucharistic prayer.

I think that my reviewer here is just insisting on practical matters, and is determined to leave aside the theoretical, such as questions about the meaning and justification of trinitarian claims. “Explaining” trumps explaining (i.e. explicating or clearly conveying the meaning of traditional sentences).

Who is the God who is here addressed? The Father … but not just any Father but the Father of Jesus, his only begotten Son. The Creator is mysteriously constituted by his relation to the Nazarene.

Right! This is all unitarian compatible.

In 381 the Church definitively settled on the homoousion, applied to both the Son and Spirit.

As I explain in the book, actually emperor Theodosius I settled the dispute, and the portion of the Church which he favored (the pro-Nicene party), gladly accepted his legal strangling of the opposition through a serious of legal measures. The argument was forcibly ended.

Perhaps a book review ought to preach a little less and actually interact with historical information in the book.

Underlying, shaping, and energizing the Church’s reflection on the Trinity is its foundational doxological praxis: the Church prays to the Father, through the Son, in and by the Spirit.

I’m sorry, Fr. Kimel, but this is just rhetoric. “The Church” (i.e. mainstream Christians) did this before there was any theology of the Trinity. What you say here is what I, as a unitarian Christian do. We are talking about the Trinity (the triune God), right? Because you keep returning to the triad/trinity. The difference? It’s in the book.

Hoping for more book in part 2 of the book review. 🙂

http://trinities.org/blog/kimels-review-of-what-is-the-trinity-part-1/

0 notes