#aurenna

Text

The vowing table in the landsaint’s barracks was lopsided as Raam peaked over the lip of Aurenna outside – and not just because one of its legs was worn too short. A saintsworn was absent; Nojjeth never reported in last night. Her silver handprint, shaped to her large Dromag hand, was bare. But the Greshtal Ulashkr and the Aajakiri Fhelleid planted their palms on their silver handprints, connected by a thin silver ring to the golden print that held Imreb’s hand.

A landsaint’s vowing table was where they and their ‘sworn made their vows to their community. The ‘sworn vowed to the saint, who swore them all to Raam himself. He was represented at the center of the table by a magically lit candle upon a raised golden circle, connected by a single gilded line to the landsaint’s handprint.

Ideally, the circle of hands is complete before vows are made. But exceptions are often necessary.

“Before we begin,” whispered Imreb so as not to disturb the candleflame, “do either of you know of Nojjeth?”

“Nay, saint,” boomed Ulashkr, the candleflame vibrating with his heavy voice. “I have not seen her since yesterday’s vowing.”

“Nor have I,” admitted Fhelleid, her brow-plates still. “Perhaps she got lost.”

“No jokes at the vowing table,” chided Imreb. She pushed her hand into the golden handprint and turned to face Fhelleid. “Ser Fhelleid. Your saint requires you patrol the undermarket and keep watch for hooligans and burglars. Do you so vow?”

“So I vow, saint, by witness of Raam.”

Imreb turned to Ulashkr. “Ser UIashkr. Your saint requires you seek out absent Nojjeth and return her here by nightfall. Do you so vow?”

“So I vow, saint, by witness of Raam.”

Closing her eyes, Imreb made her own dedication: “Landsaint Imreb makes her vow to seek out the recent apprentice of jeweler Glaa’ib for interview regarding an ongoing investigation. By witness of Raam.”

“Saint,” interjected Fhelleid, “I should assist you. I am familiar with this matter.”

Imreb opened her eyes to glance at Fhelleid. Was she the one who suspected her? But the central candleflame blew itself out.

“The vowing is complete,” said Imreb sternly. “Keep your vow as promised, Raam your witness.”

Fhelleid’s brow-plates sank, but she said nothing. The three left the barracks and went to pursue their vows.

-

Thus spake Ngashiik:

The world kills emptiness on sight. Empty your mind and allow the world to murder it. Take in the world writ large, and return the favor. At the bottom of that darkness is a light: Raam.

Raam is the zenith of the heavens; Raam is the nadir of the mind.

-

The landsaint’s barracks were on the other side of the river from the bulk of the surface town. A sandstone-brick arch crossed the flowing coppery water to the sandrock formation on the other side which hid the town. Only smoke vents and tall crimson banners revealed its presence to the observant.

Imreb followed the worn road to the north gate: two enormous slabs of engraved sandstone, presently cracked wide enough for single-file trade caravans. Nodding at the guards, who bowed gently at her presence, Imreb slipped between the rear of a grain-bearing wagon and a beast of burden behind to enter the city.

Under rays of morning light slanting through cracks in the west, the huts carved from the sandstone gleamed bright. Smoke from last night’s recently-extinguished braziers filled the air, the perfume of foreign wood and ash leaving behind a thick pale haze. But through the haze one could easily see the brightly-colored murals, frescoes, and graffiti impressed upon nearly every open flat surface of the cavern.

Imreb nearly ran into a Greshtal carrying a crate of produce, but ducked just in time thanks to her saint’s reflexes. The caravan she’d followed in was being unloaded, state supplies being doled out to various warehouses and storerooms, and trade goods being delivered to the nearby elevator to the underground.

Imreb passed a Dromag laborer toting a great pot of spice as big as she was. With each step the overfull pot dashed fine ruddy powder into the air, a fair amount clinging to the Dromag’s beard. It didn’t seem to bother her, but Imreb caught a whiff and wondered how it couldn’t, unmistakable the hot, pungent smell of kezzac root. Imreb quickly zipped away from the puffs of dust and pursued a nearby passage to the right.

Imreb followed the graffiti-scrawled alley along the outer rim of the rock-cliff’s cavern, occasionally passing shafts of light from the left where the alley opened up into one of the major chambers. The rest of the way was darkness – but the eyes of a saint, blessed by Raam, saw light where it was scarce. The alley curved first west, then south, and the dim graffiti grew more and more desperate and more and more profane as Imreb neared the southside.

Finally the passage opened up into the south gate cavity, the old market. Most merchants had fled underground long ago, but a handful still stubbornly remained, like the old jeweler, Glaa’ib. He sat on a stool in front of his small shop, whistling tunelessly and stirring a kettle with a stick – both spoon and pestle. He was close enough to the gate to catch the morning breeze, but just out of the sun’s harsh light to hold onto the cool shade.

He stopped whistling and raised a great red-and-black Dromag hand to wave Imreb over. “Saint, saint!” he cried with his old raspy voice, a pitch higher than Imreb’s ears would have liked. “Come, come! Breakfast is near ready, and a good blessing is needed!”

Imreb crossed the empty old market to the elderly Dromag, his sparse shock of still-red hair glistening with condensed steam from the brass kettle. She took a look inside, but the smell told her long before what he was cooking: mashed and stewed and mashed-again silc beans, the grey flesh of the blue legumes thickening endlessly into a dense, viscous paste, popular among elderly Dromag whose teeth have lost their edge.

Indeed, Glaa’ib grinned at Imreb, his once-pointed teeth now rounded like tombstones. “A pleasure, a pleasure! Moreso when the miisilc is blessed, yes?”

Blessing food was a formality; it was nowadays known that many factors played into the safety of food, and none were spiritual. But the saints and priests allowed the faithful to still believe. Imreb held her hand over the kettle, in the cooler upper reaches of the steam, and mumbled a prayer to Raam, and to Byilo, old Saint Holy of Right Cuisine.

“A pleasure twicefold, saint!” Glaa’ib reached behind for a cracked and chipped bowl. He gave the miisilc a last good pound with the spoon-pestle and used it to tear off a steaming glob of slop into the bowl, and offered it to Imreb. “Here, here, saint! Eat, eat!”

Imreb glanced at the grey mush with barely-hidden fear. “No, thank you, Glaa’ib.”

“No, no, saint!” said Glaa’ib with a shake of his head, his red-and-white beard swaying back and forth. “No harsh spices. You are Aajakiri, I know such flavors do not favor you.” He extended the bowl further.

“Thank you, Glaa’ib, but I’m fine.” Imreb tried to push away the bowl.

“Oh, oh, of course!” Glaa’ib exclaimed, withdrawing the bowl. “The saint likes it sweet!” The Dromag reached to the side for a small pot of white powder. With his large hand he grabbed a mighty pinch of sugar and poured it into the bowl, then offered it again.

“Glaa’ib, no!” said Imreb, nearly losing her patience. “Thank you, but I’ve already eaten.” It was a lie, but she’d rather starve than try to swallow miisilc, no matter how sweet.

Glaa’ib’s smile finally fell a bit, hiding more of his teeth. “Very well, saint,” he said, taking the bowl for himself. He dipped a couple of fingers into the miisilc to scoop up a bit of the bean-paste. “How may I –” he stuck his fingers in his mouth and began chewing, “– helb you?”

Imreb sighed. “Tell me about your recent apprentice.”

Glaa’ib groaned. “Goo’ stuff,” he mumbled through his chewing.

“...Glaa’ib?”

“Sorry, sorry,” mumbled the Dromag after he swallowed. “Mrogem, you mean. Nasty brat. No eye for detail. Couldn’t tell emerald from peridot, sapphire from aquamarine, diamond from quartz – much less cut anything right. Told him so one day and he got so angry, I never saw him again.” He wielded his spoon-stick like a club. “Give the boy his dues, I would, if he dared come back!”

“No weapons,” warned Imreb.

“Oh, it’s just my stir-stick,” said Glaa’ib, returning it to his kettle. “Don’t contort yourself.”

Imreb pulled the flawed thoughtstone from her pocket; she winced at its speech, having forgotten to brace her brow-plates. She showed it to the jeweler. “Did he cut like this?”

With his cleaner hand Glaa’ib took the sapphire and gave it a brief once over. “Hm. Looks similar. Seems he’s still been practicing, but it’s still shit.” He brought the sapphire closer and squinted. “Is this thing filled?” he asked, shaking his head. “Raam above, why’d you use it?”

“I didn’t fill it,” said Imreb. “Someone else did. I’m trying to figure that out.” She held out her hand to take back the sapphire. “Do you testify this is Mrogem’s handiwork, Glaa’ib?”

“I so testify, saint,” said Glaa’ib, handing back the thoughtstone. (She wiped it quickly on her sleeve before putting it away again.)

“Do you know where I might find Mrogem?” Imreb asked.

“Cursed if I know,” Glaa’ib admitted. “Maybe ask some of the young Dromag?” he suggested. “You know the rascals, too big for their feet. Barely grown their beards in, scrawling profanities on the walls. Like, like…”

“Kheloz, perhaps?” offered Imreb, optimistic.

“Yes, yes! He’s one of their lot. He might know where to find blasted Mrogem.”

“Thank you, Glaa’ib. You’ve been very helpful. Blest day.”

“And you, saint, a blest, blest day!” returned Glaa’ib, but Imreb had already turned to leave.

-

This ancient dune overlooking the fields flanking the Heljaar river as it wound its way east to the distant coast was Imreb’s favorite place to meditate. But her eyes were open, scanning the landscape before her, discerning discrepancies. Raam was high in the sky at his apex, his light harsh upon Kolqust, but illuminating the river’s arc like the bent swords of ancient desert tenvo, a wicked streak of bronze, ending in a sharp point on the distant horizon.

Before the farmland disintegrated into sand, the fields of precious crops clung to the precious coppery water. The fingers of grain and stalks of beans danced to the tune of the wind rolling down the river’s course. She listened to that familiar sound, and her mind began to drift towards contemplation…

Wait. Her ears twitched as she focused her hearing. That wasn’t the song of the wind – not entirely. There was a distinct melody hovering over the land, almost haunting it. She slid down the dune to follow the tune.

Tracing the small irrigation rivulets separating the fields, she located the source: a young Dromag in a fallow field plucking at his tellish, a stringed instrument with three courses of two strings each, a seventh drone string, and a wide, deep body. Unnoticed, Imreb listened silently.

It was a deep-desert Kolqusto ballad Imreb didn’t know the words to. The player didn’t, either, or else didn’t want to sing for some other reason. He played soulfully, jostling the tellish on some notes for extra vibrato. His large fingers gracefully danced upon the frets, wringing from this piece of molded wood and wrought metal one of the sacred blessings of the world: music.

“Kheloz.”

The musician missed a note, spoiling the composition. He stopped and craned his neck to see Imreb. “You’re a very sneaky saint,” he observed with a sigh.

“And you’re a wonderful tellish player,” she added.

“I imagine,” Kheloz said, laying down his instrument flat on his lap, “that you’re not here to compliment me. Is it about the thoughtstone from yesterday? I don’t have it on me.”

Imreb’s listening brow-plates said he was lying, but she decided not to pursue it. “Not that,” she said. “I’m looking for someone. A friend of yours.”

Kheloz fiddled with the strings idly. “I’ve got a lot of friends. You’ll have to be more specific.”

“A Dromag,” said Imreb, “by name of Mrogem. Apprenticed under Glaa’ib the jeweler.”

“Not for very long,” Kheloz muttered. “Yeah, I know him. Deep-desert bastard. Bet the ‘prentice job was a grift. He’s always on some grift.”

Imreb squatted next to seated Kheloz. “Where could I find him?”

“And why should I tell you?”

Imreb narrowed her eyes, her brow-plates contorting in what she hoped the young Dromag would recognize as a threat-display. “Because I’m your landsaint.”

He met her eyes for a moment, but didn’t seem to take notice of her brow-plates. He stared back for a moment before relenting, looking down at his tellish. “Yeah, yeah…fine.” He nodded his head towards the main rock of the above-ground city. “Like I said, he’s deep-desert. But he lives away from his tribe, in some ruins a few miles south of town, all by himself. I’ve never been there, so that’s all I know, saint.”

Imreb stood, wiping dirt from her legs. “Do you stand by this testimony?”

Kheloz sighed, and gave his tellish a dissonant strum. “I so testify,” he groaned, as if his mother had just ordered him to bed.

“Good, good. Blest day, Kheloz.”

“Blesdy, saint.”

-

Raam hung low in the east, nearly over the lip of the world, casting the desert into bifurcate shades of bruise: the sky a deep purple, the sand a vibrant orange. The concentric azure flowers of the tall gyec cactus took their cue to bloom under the now-visible swarms of spirits above. To the distant northwest the land began to rise, first as tall dunes, then high foothills, then farthest away, the silvery cliffs and peaks of the Raamo mountains at the center of Aurenna, wherefrom the holiest of priests officiated in their sacred temples.

A sudden evening breeze came down the side of a nearby dune, casting a spray of fine sand in Imreb’s direction. She squinted her eyes, tightened the scarf covering her mouth and nose, and fluttered her brow-plates to keep their crevices clear. Heading out deep-desert was far from ideal, but it was part of her duty as landsaint of Ab’Heljaar and its surrounds.

She knew little of the desert here, save for a handful of landmarks. To the west were the relatively recent ruins of an abandoned fort, from a few centuries ago when Kolqust was first conquered and established as a temple-state. Farther south were a few more-ancient remains, long since mostly-buried by the sand. The deep-desert tenvo say this land was not always desert, and that a great empire, counter to the ancient Dromag to the north and Aajakiri to the west, once spread across the fertile plains and forests. They claim the rising of the central mountains by Raam cut them off from rain somehow, and the deep-desert tenvo descendants of that empire still curse his sacred name.

There were a couple ruins that Imreb could think of that matched Kheloz’s description, so she sought them out, following dune-valleys south.

There was a sudden rumbling of the sand beneath Imreb’s feet, and she panicked for a second. Had she wandered into a sinkhole, or quicksand? But the rumbling moved away, and a few yards to her right she saw a sandfish, larger than she was tall, its sand-dusted scales glistening in the dusklight, emerge from the ground, followed by another, and another. An entire school of them swam past, each breaching briefly in turn, reaching twice Imreb’s height into the air. They kicked up sand upwind, so she had to flutter her brow-plates again.

Imreb had heard stories of deep-desert tenvo taming these strange beasts, and riding them across the sands. But she doubted it was really possible, for more reasons than she could count. But she had also heard of the feats of the skytrout cavalries of the western swamps (difficult to imagine such a wet place, out here), how they sailed the skies from pond to pond. So maybe such things were possible.

As she watched the sandfish school swim away, she caught a glimpse of a pillar of smoke through the clouds of dust they stirred up. She changed direction and strode through the sand towards it.

Mostly buried in the side of a dune was part of an ancient edifice of worn sandstone brick, a sunshade embedded in the sand held up by pillars engraved in an unfamiliar hieroglyphic. There was a bedroll and collection of reed baskets and clay pots tucked in the covered nook, but right outside was the remains of a fire – still smoldering, so not long extinguished. A half-cooked desert rodent (Imreb guessed the long-tailed gweld) was still strung from a spit over the warm embers.

Cautiously Imreb inspected the camp, also scanning the surroundings for signs of life, but found none. But it seemed obvious to her that someone had very recently been here.

She checked out the reed baskets and clay pots, and their contents. One had the flour of the benquc tuber, seemingly for making gruel in the dirty pot nearby, or flatbreads in the filthy pan next to it. Two small pots next to it held white powders – presumably salt from a nearby salt-plain and sugar extracted from cactus sap. Another basket had foul-smelling dried sandfish steaks, a deep-desert delicacy that nearly turned Imreb’s stomach from the stench. Another held nearly spoiled gyec cactus berries – but maybe the owner planned to make gyec wine from them, it wasn’t clear.

In the darkest corner of the recess, Imreb’s saint-eyes caught a glimpse of another basket. As she neared it, her brow-plates reacted harshly, nearly recoiling completely into her head. She took a look inside: gems of every kind and shape, some filled, some not, some flawed and leaking, some not. They spoke in a horrible chorus of pain, the cacophony like listening to the entire night sky all at once, but so much worse.

She reached in to grab a thoughtstone, but her instincts kicked in as she heard a subtle shuffling of sand behind her. She whipped around, calling upon earth spirits to turn her hand to stone.

She caught the rough blade aimed at her head with a hardened palm, wrapping her fingers around it before it glanced off completely. Her attacker was a wiry-bearded Dromag with a shaved head, wielding a bronze “self-defense implement,” and clearly shocked at Imreb catching it so effortlessly.

Still holding the weapon, Imreb ducked low, sweeping a leg under the Dromag’s, knocking him flat on his back, simultaneously wrenching the blade from his hand. She tossed the sword into the air, flipping it to catch it by the hilt. Before the Dromag could catch his breath, the tip of the sword was pointed at his throat.

“Mrogem,” Imreb said, “you’ve just attacked a saint.”

Mrogem looked into her eyes to verify, and fear washed over his face, tightening the lines of his brow. But he returned, “I’ve just attacked a stranger snooping around my belongings. That’s defense of property, saint or no saint.”

“Perhaps try diplomacy next time,” Imreb suggested, “before immediately reaching for a blade.” She pointed back at the thoughtstone-filled basket. “What use does a Dromag have for so many thoughtstones?”

“What?” Mrogem glanced quickly at the basket in the shadowed corner. “Those’re just random gems I found. Honest.”

Imreb sighed and pointed at her brow-plates. “Don’t you recognize an Aajakiri when you see one? I can’t help but hear those leaking ‘stones.”

“Leaking?” Mrogem’s eyes went wide. “What do you mean? They’re cut just fi-” He shut himself up before incriminating himself further.

“‘Just fine,’ hm? You don’t cut as well as you think.” Imreb pulled out the leaking sapphire from her pocket and tossed it down to Mrogem.

He caught it in his hands – albeit clumsily – and looked it over. “Looks fine to me,” he said.

“Glaa’ib was right,” mumbled Imreb just loud enough for Mrogem to hear. “You have no eye for gemcutting.”

“Saint Imreb?”

Imreb planted a foot firmly on Mrogem’s chest before turning toward the speaker, stood at the top of the dune. It was her ‘sworn, the Greshtal Ulashkr. “Ulashkr?” Imreb called back. “What are you doing out here?”

“I was seeking out Nojjeth to honor my vow,” he said solemnly.

“Good,” said Imreb with a nod. “I’ve just honored mine. Help me bind this tenvo and I’ll help you finish honoring yours.”

“I’ve already honored it,” said Ulashkr, his face a grim mask. He pointed east.

Against the black backdrop of the newly fallen night, Imreb saw crimson carrion birds circling in the sky.

“No…”

-

Thus spake Walfa, Saint Holy of Right Burial, as she was buried:

“It is the blessing of the dead to walk no more.”

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

wait shit. i wanted to write about how this river is so wide you can't see across it. but. aurenna is flat. curvature won't be an issue. is there any other factor that would limit visibility at a distance?

8 notes

·

View notes

Note

The little red head ran up to his Atya, squealing excitedly as he pushed a pretty little box into Ara’s hands; it held a beautiful pair of earrings. “Aurenna Atya Valin!”

"Oh!" Ara knelt down, smiling as he took the box from Nelya. He gasped opening the box. He had thought perhaps something similar to the craft projects Aegnor gifted him as a child, but these were clearly made with great skill. He pulled his earrings off to replace them with the new ones. "They are beautiful Nelya." His eyes teared as he smiled again. "You sweet sunbeam~" Ara pulled him into a hug, kissing his face all over.

#Sorry I'm on mobile browser tumblr but I hope you see this#this was so cute Q u Q#preciousbabyNelya

1 note

·

View note

Text

Korleth scrambled through the tight autorat chute, richly-bejeweled ring clutched in his large Dromag fist. Even full-grown now, he was still somehow small enough – just barely – to squeeze through these tunnels meant for the small thaumechanical sweepers. Good thing, too – they made excellent escape routes, and connected most of Derthn.

He needed to crawl far enough away – to some adjacent district of an adjacent district – to evade any pursuers, as well as shake off the noses of the autohounds. They followed a different network of tunnels, more accommodating to their larger size, so he wouldn’t run into any down here.

Raam, it was scorching in here. These tunnels must run adjacent to the geothermal systems for this district. It didn’t help that the blasted autorats had a tendency to run hot.

Shit, there goes one now. Korleth arched up his back and spread his arms and legs wide to let the autorat pass under him. It barely fit, chafing his front as it went by. He’d lost too many tunics to these bastards tearing through them as they ran by like this.

A little farther along he thought, This should be far enough. He turned a corner and –

He hit his head hard, ruffling his scarlet hair. He looked up to see a welded grate blocking the tunnel. That hadn’t been there last time he’d come this way. Damn Architects. Fine. Have it your way. Korleth backed out and started crawling farther, towards the next district over.

After another few minutes in that hot, cramped tube, Korleth found another exit side-tunnel. He turned to follow it and pushed open the vent to the outside.

And his head was almost crushed by the lumbering foot of an autotrunk.

He ducked his head back just in time and hid inside as the huge thaumechanism and its entourage of thaumechanics passed the vent, his heart pounding. Once he was sure the sounds of footsteps had passed, he pushed open the vent again and crawled out.

As he dusted the metal shavings and dust off of his tunic, he glanced at the passersby across the street giving him brief notice. They had no connection to the district he’d just stolen the ring from, and besides, a tiny Dromag crawling out of an autorat tunnel was probably not the weirdest thing they’d seen today.

Keeping it shielded from the rest of the city, he opened his fist and made sure the ring was still intact. The dozen or so tiny jewels smiled at him with their sparkling facets, but the big one at the center all the more so – a perfectly-round carnelian thoughtstone, a vague light gently throbbing inside the dark red gem. This one would fetch a pretty penny – probably. He had no way of knowing what the thoughtstone said.

He looked up to see what district he was in. Judging by the address numbers he supposed it was Residential-Four. Kids swung from artificial brass trees in the miniscule gardens of these middle-class apartments. Tenvo tended to the bioluminescent fungal crops bursting from the transplanted soil. Others were hanging their laundry out to dry, tunics and cloaks and turban-cloths and undergarments. One of them, apparently a mother with an infant on her hip as she struggled to one-hand the clothespins, stopped a moment to wave at Korleth. He supposed that was good – he didn’t stand out as not belonging there, despite his rather drab attire. He waved back with his free hand.

Who was the local fence? In Res-Four it would be…Zrikr. A miserly old Dromag. But he might have Aajakiri connections who could appraise the thoughtstone. Korleth again examined the nearby address-markers, engraved into the brass lintels of the apartment’s front doors. Res-4-Hrem-15-22. Res-Four. Subdistrict Hrem. Area fifteen. Level twenty-two. Zrikr shouldn’t be far – in this subdistrict, at least. Korleth wracked his brain. Area six, level twenty-nine, if he recalled correct. It would take some walking up-town and an elevator ride, but nothing he couldn’t manage in a half-light. He stuffed his hands – ring carefully in fist – in his tunic’s front-pocket, and started up the street.

He followed an autoshell for a while, head bowed like an thaumechanic, until its six skittering legs walked it into an autoshell tube, collapsing into its carapace so that it could roll on hidden wheels through the tunnel. Then he carried on alone, seamlessly switching from slow thaumechanic piety to the lazy stride of a normal citizen. Blessedly there was an elevator in area five – there were elevators in every fifth area of a subdistrict – so it only took crossing a single area after descending to level twenty-nine to arrive in Zrikr’s area.

There were signs, if you knew what to look for, that could point you towards a clan fence. Subtle etchings in the walls of the caverns. Only clan members could interpret them. Korleth had more or less been born into the clan, he was adopted so young. So he followed the signs to the seemingly abandoned apartment they indicated.

He knocked on the door, a harsh rhythmic rap that signaled clan membership. After a minute or so the door cracked open to reveal a pair of red-flecked black eyes, Dromag eyes. The door closed for a moment, then opened all the way. A tall, stocky Dromag stood in the doorway, her beard styled like a cage around her mouth, individual braids stiffened upwards in arcs like prison bars. A Silencer – clan bruisers. Korleth took careful note of the thick, barely-tapered stone club in her hand.

“Speak,” said the Silencer, leaning against the door frame, arms crossed with club in tow.

“Here for Zrikr,” answered Korleth. “Got something for him.”

“Delivery or merchandise?”

“Merchandise.” Korleth half-revealed the ring in his pocket to the Silencer. She nodded and went back inside, closing the door behind her.

Another minute passed until the door opened again. This time the Silencer stood to the side to let Korleth in. He gave her a curt nod as he passed, but she only returned with a puff of air from her nostrils, rattling the bars of her beard-cage.

It smelled heavily of gridc smoke in here; a filmy haze of it lingered in the air. The apartment appeared inside as it did outside – abandoned. Almost all the furniture was overturned, dusty, moldy, and cobweb-stricken. And it was not even of consistent organization, seeming to have too many of some articles, and not enough of others. There were only a few relatively clean and upright pieces: a brass cushionless couch, which the Silencer sat on when she wasn’t answering the door or Silencing, and a desk in the back with a small wheeled chair, also of brass. Its occupant sat with his back turned to the door, but when Korleth approached he swiveled around to face him.

In that chair and at that desk sat a wiry old Dromag, puffing on a claypipe. As Korleth approached, he noticed that the claypipe was ornamented with intricate brass inlays – or was it gold? The room was too dim to be able to tell for sure, and Korleth was no metallurgist. Most he ever got ahold of was silver, since the damned Temple hoarded most of the gold jealously. Zrikr played a dangerous game if he decorated something so mundane as a claypipe with the precious metal. They could send Saints after him to confiscate it, or worse.

“Aye?” said Zrikr, not removing the claypipe from his lips as he did so.

“Venerable Zrikr,” began Korleth with the typical clan salute for elders, a spreading of the mustache with the index finger and thumb. “I come to offer merchandise.”

Zrikr slowly pulled the pipe from his mouth, put it out, and laid it down gently on the desk. “Very well. Come closer so I can take a look. Lay out your product.”

Korleth obeyed, stopping inches from the front of the desk. He removed the ring fully from his pocket and began to set it down on the desk –

Zrikr grabbed Korleth’s ring-bearing wrist. “Do my old eyes deceive me, tenv?” He squinted his eyes at Korleth’s face. Korleth managed to maintain his outward composure, but his tongue rolled across the back of his sharp teeth anxiously. “You the old Baron Cemming’s kid? That autorat he picked up off the street? Glorious prodigy of the clan?” He tightened his grip, but his eyes roamed in recollection. “Korleth, is it?”

“Yes, Venerable Zrikr,” said Korleth smoothly, but between his teeth. “Maybe not so many words are needed.”

“Maybe not, maybe not,” said Zrikr. “I knew old Cemming when we were lads. He was a whip of a tenv, but he knew his shit. Took good care of his people. Not like those gasbags in charge now.” He smiled, revealing teeth too sharp for a Dromag this old. He must sharpen them daily, Korleth thought idly. “I hope you’ve got the old tenv’s same measure.”

Zrikr released Korleth’s wrist. “Now, what have you here, young tenv?”

“Thoughstone ring,” said Korleth, finally able to lay the jewelry down on the desk. “Carnelian with orbital rubies and citrines.”

“Carnelian thoughtstone,” said Zrikr, picking up the ring and holding it close to his rheumy black eyes. “What ever will they think of next?” He examined the ring entire for a minute before setting it back down. “Gems are well cut. Silversmithing is of high quality. Couldn’t tell you shit about the ‘stone.”

“Do you have an Aajakiri associate who could appraise it?” asked Korleth.

“You take me for an amateur, tenv?” said Zrikr coldly. Korleth could hear the slap of the Silencer’s club on her palm. Zrikr glanced at her and shook his head. “Yes, yes. I have a damn Aaj on the payroll. Give me some time to ask her about it. Couple days maybe.”

“Advance?”

“Of course,” said Zrikr, his smile wicked. He reached into the desk, pulled out a wrapped parcel, and handed it to Korleth. Korleth opened it halfway to peek inside: it was a half-loaf of dense mushroom-and-nut bread, the nuts few and far between in a tight matrix of grey-green grain. It barely fit snug in Korleth’s palm. “That should keep you ‘til I hear back.”

Shellshit, Korleth thought, but he played it cool. Zrikr didn’t seem like the type of tenv you messed with – you didn’t get this old in the clan without a bodycount. And Korleth certainly didn’t want to get on the wrong side of that Silencer’s club. “Yes, Venerable Zrikr. Thank you.”

“Now off with you,” said Zrikr with a wave. He picked up his claypipe and used a thaumechanical sparker to light the bowl again. “Disturbing my smoke time.”

Korleth obeyed, and left. He didn’t bother nodding at the Silencer this time.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

The descending lift was claustrophobic. The landsaint was becoming an under-landsaint with every jagged tug towards the bowels of the earth. She kept her breath steady and long so as not to panic. A Dromag attendant in the opposite corner of the lift had his arms crossed, and she could feel his hot breath, and smell its pungent spiciness.

The light approached from beneath, piece-by-piece with each pull of the chains. (The bigger cities had automatic lift mechanisms, but these were still hand-cranked.) The landsaint must have begun to hold her breath when the light first appeared, because it escaped in a single burst once they reached the lift’s landing below.

The attendant opened the brass-barred door, letting in more light from the landing. “This floor,” he mumbled, well-practiced but bored, “Market. Shrine.” He stood on his tiptoes to check the landsaint’s irises. “You know this. Blest day, saint.”

The landsaint stepped out of the lift, which immediately began to ascend to pick up more visitors to the city’s belly.

She hated the air down here. Dry and stuffy. Even when the air was cool, it felt hot. She was going to finish her work here and return topside, as soon as possible.

Two half-halberd-wielding Greshtal guards let her through with a nod. The landsaint returned the gesture curtly. Beyond the guarded brass door was a deep-dug city of stone, four stories high, stone stairs winding up and down the sides of stone buildings to stone balconies giving landing for brass doors, wooden planks from surface trees filling in gaps and forming crossings where the stone streets were narrow. Blackflame lamps kept the streets and stairs lit, but the closer to the roof, the darker it became. Up there, tall shadows danced. Only Dromag were short enough for the low ceilings in these reaches, but children of all types daredeviled from ledge to ledge.

The lower two levels were purely commercial, various shops and stores and groceries and boutiques lining the streets and dazzling passersby with brightly painted signs and intricately-woven tapestries. The two levels above were for the homes of the merchants. But not all who did business in this district lived here. Many commuted with their stalls and carts from the lower residential levels via the bigger, industrial lift by the main gates of the surface town.

The landsaint scraped past pedestrians and took in some of the shops and stalls. She saw a smithy selling blades –

– but the smith couldn’t call them blades. It was illegal in this jurisdiction of Kolqust for most tenvo to carry weapons larger than a work-knife. But many smiths circumvented this restriction by selling sharp scraps of bronze that almost looked like blades, but by the precise wording of the law couldn’t be called weapons. All it took was some string, resin, and a suitable length of wood to manufacture a “self-defense implement” at home. The landsaints politely ignored these loopholes; it was their job to enforce laws, not argue them.

– a wooden sign, painted with the words “mostly-meat sausages” (in smaller script beneath: “accepting chit only”), indicated such meats were hawked at the rickety stall where it hung by a lanky Dromag –

– those words being all the butcher needed to claim to bypass a law regulating the use of mineral additives in such products. Dromag had sturdy teeth and hardy stomachs, and could handle a little clay or limestone in their mixed meats. (During ancient times of poverty, clay was a common food source for the Dromag, earning them the now rarely-used sobriquet “clay-eaters.”) Aajakiri and Greshtal, on the other hand, could not digest these things. But when the prices were this low, a chipped tooth or a little indigestion was worth it.

– in a dim corner, lit by an array of colored paper lanterns, sat the waterpipe lounge –

– where the only smoke of griidc could be found in these times, as individual possession and consumption of the narcotic by claypipe had been outlawed by the state about a decade ago, much to the dismay of the large smoking subculture of Kolqust. Begrudgingly, tenvo would pay to smoke in these lounges for an hour, taking up their hoses around the communal waterpipe and allowing the smokemaster to supply them with their fix.

– a beautifully engraved storefront advertised “Oshr’s Fine Jewelry.” Through the open arches of the facade were rows of glass-protected counters bearing precious jewels, rings, necklaces, bracelets, anklets, torques, tiaras, and more. In the back, at a counter operated by Oshr herself, a beautiful face-painted Aajakiri, were displayed the finely cut, delicately-faceted receptacle gems for spirits, future thoughtstones –

– illegal to fill without saint sanction, but not illegal to cut and sell beforehand. Only saints or temple priests are allowed to capture spirits or sell thoughtstones.

The landsaints brow-plates flexed as she listened vaguely in the direction of the jeweler’s shop. Something tickled her brow-plates, and she focused on it.

It spoke of mastery. It spoke of a job well done, a product complete. Satisfaction – of the mind and the chit-purse. A deal. A transaction. A bargain sworn.

The landsaint squinted at Oshr. Her neck gleamed with a brilliant ruby. Personal thoughtstone. Not for sale.

The landsaint’s brow-plates resumed a neutral position as she carried on down the street. Finally she reached her destination: the town shrine. Its set of concentric walls were beautifully engraved and brightly painted, the outer ring etched with the laws of the priests of Raam. The landsaint ascended the radial stairs, passing one circular gate as she did, leaving behind the first circle, representing Uodh, the Void. The next ring depicted the victories of local saints throughout history – this circle represented Uorh, the Word. She passed its gate, leaving her one more circle to pass – Eilh, the World – displaying the triumphs and tribulations of Raam before he ascended to bring the day. Its gate had a door, which she slowly pushed open to enter the outer sanctum, where only priests and saints could pass.

A fairly reverent tenvo, the landsaint closed the door tightly behind her. She had expected to be greeted by a priest as soon as she entered, but none appeared; all that welcomed her was the floral scent of welic incense smoke wafting from censers hanging from the high rafters. Taking a left, she walked the circular corridor, lined with shelves bearing sacred scrolls, tomes, and tablets, until she came back around to the Eilh gate. She doubled back, but stopped as she met the Raam gate, a tightly shut door to the inner sanctum, halfway down.

Her brow-plates widened, and she swallowed deep. The door of the Raam gate was of plain wood, ornamented only with a single sacred symbol etched in gold in the center. Hand shaking, she reached out for the handle…

The door burst open from the inside, and a priest rushed out. It was Jark, coadjutor of the shrine’s chief priest. The landsaint’s hands were safely behind her back, but she did catch a glimpse of the black velvet curtain behind Jark shifting – the last barrier between unsanctified eyes and divinity.

“Imreb!” snapped Jark as he nearly ran into her, clutching his chest with his large Dromag hand. “What are you doing here?”

“I was waiting for you, Holy,” Imreb replied.

“You’ve been waiting?” stormed Jark as he pushed Imreb from the Raam gate. “I got so tired of waiting for you that I went ahead and joined the other Holies for evening communion!” He made a show of straightening his beard. “Where have you been?”

“Capturing a fallen spirit topside,” Imreb explained in a rush, flustered. “For young Kheloz.” She patted the collection case on her belt.

“Ah, young Kheloz…” mused Jark, still stroking his beard. “I remember being as young and curious as him…”

Imreb wondered if Jark had, in a past life, been a miner, or logger, or wrestler; he had a sturdy physique, and was tall for a Dromag, coming halfway up Imreb’s chest. He was this shrine’s first Dromag priest – they usually selected for Aajakiri with keen brow-plates. But Jark had somehow formulated a roundabout mystical way of interpreting thoughtstones; his rate of success was high enough to be dependable.

“Nevermind that,” Jark said, taking a seat at a bench wedged between two shelves. “Have a seat, landsaint.”

Imreb obeyed, sitting next to Jark. “What troubles you, Holy?”

Jark reached into a pocket of his robes and retrieved a small sapphire thoughtstone. But Imreb didn’t need to attune her brow-plates to hear it speak.

It spoke of tears. It spoke of wailing, weeping. Wet eyes and running noses too pitiful to look at, but demanding attention regardless.

“It’s leaking,” said Imreb, having to fight back her own tears from sympathetic reaction.

“As I suspected,” Jark said with a nod. He extended a massive hand to show Imreb the stone. “See the facets, here? Asymmetrical. Imperfect cut.”

“Where did you get this?” Imreb asked, her brow-plates receding into their sockets, trying to distance themselves from the pained thoughtstone.

“One of your knights confiscated it from an Aajakiri thief. Not sure the original source.”

Imreb leaned forward. “Which knight?”

“Confidential, I’m afraid,” said Jark with an apologetic smile raising the corners of his whiskers. “But it’s not the only such thoughtstone I’ve been delivered. It’s a pattern, now.”

“‘Illicit manufacture and sale for profit of thoughtstones,’” quoted Imreb from the legal code. “Could likely append ‘improper treatment of a spirit’ due to the poor gem quality.”

“Precisely,” agreed Jark. “An investigation is in order. Too delicate for a knight. You’ll handle it personally.” He handed Imreb the thoughtstone, which she quickly pocketed to silence it. “Start with talking to Oshr, the jeweler.”

“You suspect her?”

“Raam, no. Her handiwork far surpasses this. Don’t even suggest that, she’ll just be offended. Be discreet with her. Don’t let on too much.”

“With all due respect, I know how to conduct an investigation, Holy.”

“Of course, Imreb, of course,” said Jark with a gracious nod. “Go. Do what you must.”

Imreb nodded and stood to leave the shrine. “Wait,” said Jark as she was halfway to the Eilh gate.

Imreb turned back. “Yes, Holy?”

“I probably shouldn’t tell you this, but…the knight who brought me that thoughtstone told me they suspected you. That’s why they brought it to me instead of you directly.”

Imreb’s eyes widened, her brow-plates spreading apart. “Holy, I-I…”

“Don’t worry,” said the Holy with a wave of his hand. “Mortals can be easily mistaken. Would I have discussed this with you if I believed you were the culprit?”

“I suppose not, Holy.”

“Relax, and do your duty, saint.”

Imreb nodded and left the shrine.

- - - - -

Imreb knocked on the arch bordering Oshr’s shop as the jeweler nearly finished shuttering it. Oshr spun around, eyes and brow-plates wide, clutching her chest. She exhaled sharply when she saw Imreb. “Saint! A pleasure. What can I do for you?”

“Evening, Oshr,” smiled Imreb. “I’d like to ask you a few questions, if you don’t mind…but first, why are you so startled? What troubles you?”

“Oh, nothing,” said the jeweler with a dismissive wave of her hand. But a flutter of her brow-plates indicated she was lying. Imreb copied the flutter to show she caught on. “Okay,” admitted Oshr. “You are my landsaint, after all…” Oshr looked around nervously before coming closer to Imreb and whispering, “Lately, I’ve noticed suspicious youths leering at my wares from a distance. I don’t see them now, but I’ve seen them the past few nights, around this time. I worry they’re planning something drastic.”

Imreb, a good, stoic landsaint, kept an even expression even at this alarming news. “Do you know these youths?”

“No, no…but…is there anything you can do?”

“I’m afraid not,” Imreb sighed, “without any hard evidence. But I’ll assign one of my knights to keep watch down here at night. Would that make you feel safer?”

“That would be wonderful, landsaint,” said Oshr, smiling wide, her hands clapping together, and her brow-plates raising. “Now, sweet landsaint, what was it you needed?”

“Let’s speak on that inside,” said Imreb, gesturing through the gap still left in the storefront’s shutters.

Oshr nodded and led Imreb inside, closing the shutter behind them. Oshr stood behind the counter at the back as Imreb leaned against it from the other side.

“Allow me to begin by showing you something,” Imreb said. From her coat pocket she retrieved the leaking sapphire thoughtstone, her brow-plates clenched so as to ignore its speech.

Oshr reacted to the thoughtstone’s wailing immediately, her brow-plates seeming to nearly pull away from her face. “Raamfire,” she moaned, “what are you showing me, saint?”

“Confiscated faulty thoughtstone, as you may have guessed.” Imreb set the sapphire on the counter between them. “What can you tell me about its manufacture?”

Oshr futilely covered her brow-plates with one slender hand and delicately plucked the sapphire between thumb and forefinger. She rolled the cut stone between her fingers, eyes scanning the facets. “Yes,” she said, squinting, “there are some obvious flaws here. Rather glaring, honestly. What novice cut this?”

“That’s what I was hoping you could tell me,” Imreb sighed. “Do you know any local…amateurs or enthusiasts?”

“Well…there’s of course the topside jeweler, Glaa’ib, but while insufficient to my skill –” she made a sour face “– he is not this bad…I believe he took on an apprentice lately, but I heard they had a falling out. Not sure what happened to him.”

“What was his name?” Imreb asked.

“Oh, I’m not sure…Something like ‘Druugam’ or ‘Mogram’ or…something. I’m sorry, saint, I only know through hearsay from customers.”

“Don’t worry, Oshr. You’ve been very helpful.” Imreb held out a hand to take back the thoughtstone. Oshr quickly thrust it forward, grateful to be rid of it. The landsaint put it back in her pocket, silencing it and pleasing the two Aajakiri’s brow-plates.

“Blest day,” concluded Imreb as she opened the shutters and passed through the gap.

“Blest day, saint,” responded Oshr, who resumed the process of closing up shop.

Outside, Imreb looked up at the shrine at the end of the street. A solemn group of the faithful gathered around the outer Uodh wall: some kneeling with small prayerbooks in hand, counting out repetitions on their rosary belts as they mumbled the words of ancient saints; some ran their fingers reverently over the gold-inscribed engraved laws of the wall’s surface; others partook in heated ritual debate over the dictates of the priests and Raam himself.

Imreb gazed down the rings of the gates and tried to imagine what lay beyond the last, the Raam gate, that she almost caught a glimpse of earlier. She offered a prayer to that vague image and made her way topside to return home for the night.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Shiaaj woke to see a great silhouette eclipsing some brilliant white glow. “Ah,” said the silhouette with Haagrul’s voice as she sat up and tried to focus her eyes. “She awakes!”

There was a general roar of clapping and hollering at this. She swallowed to wet her dry mouth and asked, “What?”

“You’ve cast your first spell,” Haagrul said. “And quite a tremendous one at that!”

Another silhouette entered the frame, pushing Haagrul aside. Shiaaj’s eyes finally came into focus, and she saw the second silhouette belonged to Dregor, the Greshtal skysaint who cast the initial speed spell. Her face was scrunched up in some mixture of exhaustion and anger as she grabbed Shiaaj’s shoulders and shook. “How did you do it, kid?”

“Do what?” asked Shiaaj, mind still muddled.

“No games. That spell, that got us away from that wyrm. So much speed. I demand you tell me!”

Shiaaj finally remembered. The abyssal maw of the Eilhwyrm – and the opal whose secret delivered her from that maw. She instinctively began to reach for it, but stopped herself, her hand hovering near her heart. “I…don’t know,” she said. It wasn’t entirely untrue.

Dregor scoffed. “Luck, then. Pure beginner’s luck. Disappointing.”

“Leave her be, Dregor,” said Haagrul, placing a firm hand on her shoulder from behind. “Strange things are known to happen to fresh wroughtsaints. It need not damage your precious ego.”

Dregor pouted, raised her upper hands in the air, then crossed all four arms before marching away.

“Don’t worry about her,” Haagrul assured Shiaaj. “She’s a velocimancer. They’re very competitive.”

Velocimancer. A sorcerer who emphasizes speed. Without a definition given to her, Shiaaj still somehow remembered what it was.

“Tremendous thing you did,” said Haagrul. “We’ll discuss it more later. First we must prepare for battle.”

Shiaaj looked around. They were still on the Eilhship, but instead of swimming in inky blackness, it was docked in some world of near-blinding light that seemed to go on forever in all directions. “Where are we?” she asked as she clambered to her feet.

“This is a Sanctuary,” answered Haagrul, gesturing all around. “A realm within a realm, forged directly from Raam’s light.” He pointed behind Shiaaj. “They’ve lowered the gangplank. Go ahead and step out into it.”

Shiaaj approached the gangplank slowly. It seemed to have landed on some invisible platform in the empty white space. She walked to the end of the plank and, having more faith in Haagrul than Raam, she took a tentative step off.

Her foot found something solid, and she let go of a breath she hadn’t known she was holding. She let her other foot fall off the gangplank into the whiteness, and walked a small circle in it. This impossible floor was perfectly stable.

“Watch out!” yelled Haagrul. “One wrong step and you might fall through!”

Shiaaj quickly lowered her stance, spreading out her arms in panic.

“Joking, joking,” laughed Haagrul. “This place is completely limitless.”

Shiaaj frowned, brow-plates swiveling up. Maybe her earlier faith in him was misplaced. She made a gesture she’d never seen, much less done herself: a crude twisting of the arms, popular non-verbal insult among Greshtal, but lacking four arms she could only perform half of it.

Haagrul’s jaw dropped in mock surprise. “How rude, to display such a symbol to your beloved mentor! Although I supposed I deserve it.” He leapt down the gangplank in a single bound, landing on the floor of light. “Raam has prepared this place for us,” he said, changing the subject. “But we must not hesitate to join the fray.”

Shiaaj looked around. There was a great gate across from the Eilhship’s landing. Several saints were crowded around it, waiting their turn to enter. Between the bodies Shiaaj could barely see what lied beyond the gate: a haze of black smoke, dotted here and there with amorphous spots of color.

“What’s on the other side?” Shiaaj asked as she followed Haagrul towards the gate.

“War,” Haagrul said, gripping his half-halberds tight.

Shiaaj’s brow-plates descended. “I mean, what is this realm like?”

Haagrul turned his head back slightly. “I don’t know. I’ve never been to this one. But we as saints must have courage – often must we wade into unknown battlefields.”

Shiaaj tightened her grip on her sword. But slowly, thought by thought, she loosened up; even the world of Aurenna was largely unknown to her, despite the imprints of memory she was born with, so why should this be any different?

The throng of saints filtered through the gate. Shiaaj and Haagrul, near the outskirts, followed. They were close to the gate when Shiaaj asked, “What’s it like to kill?”

Haagrul sighed but answered patiently. “It’s not really killing, here. We dispel phantoms. They often aren’t gone for good. But we push through regardless. We saints are the only ones in true danger. But I will protect you. No more questions.”

Shiaaj still had hundreds of questions, but she kept her mouth shut.

Finally it was their turn. Haagrul held out an empty lower hand, and Shiaaj took it. They crossed the barrier of smoke together.

Inside, it was dimmer than the Sanctuary, but the high towers of steel and glass, reaching for the smogged sky, reflected brightly into Shiaaj’s eyes. She held up an arm to shield them a bit.

The towers were tall and square, lined with rows of gleaming windows, and arranged along black streets in perfect arrays, and crowded with so many strange metal carriages. Soldiers in strange garb – white shirts buttoned down the front, short black coats and long black pants, shiny black leather shoes, and multicolored strips of cloth hanging from their necks – poured out of the towers. They wielded strange metal staves long-ways, the ends hollow. Occasionally one would stop to point the staff at a saint, wait a moment, then let fire burst forth from the hollow end.

Shiaaj turned around to look back at the Sanctuary, but it was gone.

Out of the corner of her eye, she caught one of the strange soldiers pop up from behind one of the strange metal carriages. She turned to face him, but by then it was too late: he lifted the staff, pointed, and blinded her with the flash of a flame. Instantly she felt pain, real pain, for the first time, on her chest. It pushed her, and she fell on her back, breathless.

#i haven't proofread this at all but idc#these stories are more proof of concept than anything else ig#aurenna#my worldbuilding#my setting#my writing

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

i think magic in aurenna is so common as to be unnoticeable most of the time. like saintly miracles and the spellworks of sorcerers are such everyday occurrences that it’s just seamlessly woven into the fabric of society. this gives an illusion of a relatively magic-less world, when in fact it’s a world filled with the stuff

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

hey, i know i’m probably ridiculous for asking this, but:

do i have any mutuals/followers who would be interested in drawing a few things for me for this project? i’d like a drawing of an aajakiri, a greshtal, a dromag, and a basic map with some simple labels. i’m perfectly willing to pay if required but it might be awhile before i can do that! we can just discuss my ideas and then you can start after i have the money. completely up to you!

i have a lot of ideas for what each tenvo type looks like, and i have a randomly generated reference map and the correct labels for it! would be very interested in making some of these ideas come to life with someone :3

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

i probably ought to give a bit of a primer for tenuvo pronunciation. it's the same for all dialects, they just shape words and phrases a bit differently with the same sounds. gonna put a readmore bc this got a little longer than i anticipated.

consonants:

everything is basically the same as english, with a few small changes/caveats. "c" is never pronounced like "s" or "k," always being "ch" as in the english "chat" or "batch." "g" is always hard, like "goat." "h" by itself tends to be a bit throatier than in english, but there are some other uses for "h" i'll get to in a bit. there's a separate letter for "kh," which is like the "ch" in scottish "loch" or german "ach". there's also a separate letter (in the script tenvo use) for the "ng" sound, which usually comes at the end of syllables but can also come at the beginning. "q" never makes a "kw" sound, instead being a kind of "hard k," coming from the back of your throat, very much like the sound "q" makes in arabic. "r" is usually tapped, not like the english "r" but more like the spanish "r." "sh" has its own letter in the tenuvo script, pronounced like english "shy". "th" has its own letter, pronounced usually as the hard "bath," but dialectical variation sometimes allows for "this" (try saying both words; you'll find there is a difference!). "y" is always a consonant, pronounced as in english; most consonants have a special form for when "y" follows it. also, consonants can geminate (double), and technically this produces a unique sound compared to a single consonant, but it's rarely phonemic (as in, matters for telling between similar words) anymore.

aspirated consonants:

there are also "aspirated" consonants. ("kh" is technically one, but it's the only one that gets its own character. the rest are a combination of the normal consonant and the letter "h".) aspirated consonants are kind of breathier versions of the regular consonant, kind of the same as aspirated consonants in indian (as in the subcontinent) languages. just pronounce the consonant like it has an "h" right behind it (which it kind of does lol). aspirated consonants include: bh, dh, fh, gh, jh, kh (which has its own character), lh, mh, nh, ph (never pronounced like "f"!), qh (often very similar to kh tbh), rh, sh (as in s + h, not the "shy" sound), shh (this is sh + h, the "shy" sound), th (as in t + h, not the "bath" sound), thh (this is th + h, the "bath" sound), vh, wh, xh, yh (last two are very rare), and zh.

vowels:

so vowel length, while not always like.....actually length related, does matter in tenuvo! it's just a thing of the actual vowel sound being used mostly now. short "a" as in "cat," long "a" as in "father," short "e" as in "bed," long "e" as in "hey," short "i" as in "hit," long "i" as in "seat," "o" always as in "oh" (no length differences here), short "u" as in "cut," long "u" as in "boot." some diphthongs (all are technically "long" vowels): "au" as in "ow," "ai" as in "eye," "oi" as in "boy." (all diphthongs are rather archaic, but "aurena" uses one so yeah. there's also "oe" which is a long "cut" sound, but it's extremely archaic lol. never used anymore.) vowels preceded by a "u" develop a "w" sound, as in "Uodh" and "Uorh." if a vowel would be preceded by a long "i," the "i" is replaced by a "y."

small note on how vowel length is written: there's a few rules. typically a vowel followed by a single consonant (or none at all) is considered "long," but a vowel followed by a cluster of consonants (unless the first consonant is an "r"!) or a geminated consonant is considered "short." in some cases, though, you want to force a "long" sound even when the following consonant is geminated. to do this, you write in an "h" right between the vowel and the geminated consonant/consonant cluster.

however, as you may have noticed by how i've been writing most names, there's an alternate way of denoting vowel length: doubling the vowel for a long vowel. so for "shiaaj," for example, the "i" is short, making the "hit" sound, whereas the "aa" denotes a long "a," making the "father" sound. if it was written "shiaj," the "a" would make a "cat" sound. and, of course, the "i," being short, does not turn into a "y."

consonants as vowels:

"l," "m," "n," "ng," "r," "s," "sh," and "z," as well as their aspirated counterparts, can also be used as vowels! take, for example, the "r" at the end of "olsekr," "otr," and "utstr." that "r" at the end is a vowel! it's basically like putting a short "u" in front of the "r," but it's said so quickly that the "r" sounds like it's on its own, just floating there. the "s" in the middle of "utstr" is also serving as a vowel between those "t"s! that ends up sounding kind of like a "psst!" but with a "t" at the beginning instead of a "p." i've written some words with vowels that technically don't need them, mostly for ease of reading. for example, the southern peninsula of "gurduu" would be spelled in the tenuvo script as "grduu," with the short "u" implied and wrapped up in the "r." "olsekr" could also be spelled "olskr!"

i might be forgetting some other things, but i'll leave it here for now! i'll append this if i remember

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

about currency in aurena:

first let me explain something about scarcity in this world. as i’ve mentioned before, gold and silver are relatively common, and therefore not very valuable. they’re mostly used for inexpensive jewelry and little bobbles and trinkets. copper, as well as tin and zinc, are also fairly common. iron, however, is exceedingly rare, and highly prized. but it’s rarely used for things as mundane as weaponry or tools. functionally, most of aurena is still in the bronze age, but also brass, copper, and even in some places stone are widely used for most purposes.

most of aurena still relies on the barter system of trade. but the Raam priesthood, in the lands where it holds sway, is recently attempting to establish a standardized system of currency. it is based on the priesthood’s iron stores, which are the largest in aurena, and fiercely protected. they are using representative currency in the form of small stone chits engraved with the priestly signet; these are based on an ancient northeastern dromag custom, used in the successor states to their old empire (throst, olsekr, norkhec, otr, and utstr) where similar stone chits served as markers of a debt owed. but this new currency system is having difficulty being implemented throughout priesthood lands.

greshtal tenvo, the majority of whom traditionally live in the northeastern states (ryeka, rosyev, and aaping), have a sometimes-used system of trading in glass and brass beads. the aajikiri of the south (mornet, kolqust, gurduu, and kelgib), particularly the wealthier class, are known to trade and even collect thoughtstones, small jewels imbued with a spirit. most gemstones are fairly common, and not worth much, but with a fallen or sky-caught spirit, they are intensely valuable to the aajakiri who can hear their thoughts.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

gonna make a little pinned post for a couple notes about this blog!

1.) i know the little pieces i'm writing may sometimes share characters or events, maybe even seeming to form an actual chronology or internal consistency. don't take it too seriously. none of this is set in stone. events, chronology of those events, characters, names, lore, etc. are all subject to change as i see fit, and i'm likely not going to go back to edit old stuff with new updates. i think it'll be interesting to see how things evolve this way.

2.) the actual stories (and occasionally other bits of lore as i see fit) will be crossposted to my main/tes blog @trinimac. if you're into the elder scrolls you might be interested in following me there!

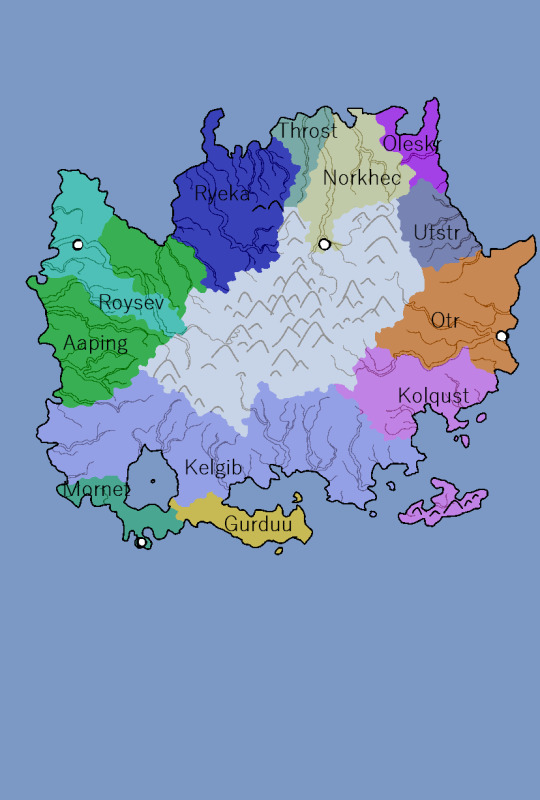

3.) here's a concept map of aurenna done by the wonderful @kixflip!

(white dots are some major cities)

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Trying to distract herself from sea-sickness, Shiaaj watched Haagrul tend to one of his half-halberds. Its shortened haft stuck between his knees, he used one pair of hands to sharpen the cutting edge of the bronze blade with a whetstone, and the other pair to polish the broad flat sides to a perfect mirror shine. He whistled an Otrian folk tune as he worked.

“I understand the edge needing to be sharp,” commented Shiaaj, “but why polish the whole thing before battle?”

Without moving his head, Haagrul glanced over his bulbous nose at Shiaaj. “The better to reflect the glory of Raam with, girl. You think this is just a weapon? It is a battle standard, more demonstrative than any banner or flag. We may use it to shed our enemies’ blood – no, these things don’t really bleed, but nevermind that – but it is first and foremost a symbol, reflecting the light of order.”

Shiaaj nodded, still a little confused. So she decided to change the subject to a question that was burning in her heart. “Haagrul…do you really think I’m ready for this?”

Haagrul lifted his head completely to look her up and down. “No,” he finally said. “But saints must often do things they are not prepared for. You will learn. Follow my lead and you’ll be fine.”

Shiaaj looked down and fiddled with the small bronze sword in her lap. “Okay,” she whispered softly, her brow-plates slanting downwards.

The sea lurched, and a burst of seaspray flung itself over the railing of the ship, soaking Shiaaj and covering her face. She gasped and covered her eyes. When it was over, she wiped salt water from her brow-plates.

“Ah!” exclaimed Haagrul. “The sea churns. We must be close.” He gestured with a spare hand. “Rise, Shiaaj. Look off the bow. You might like this part.”

Curious, Shiaaj obeyed, letting her sword clatter to the ground as she stood. She approached the railing at the tip of the bow, and looked out on the ocean. The Outer Realm Raam was Occultating was near the horizon, but all the day looked like twilight now, so the light wasn’t any different. She continued to watch the ocean foam up, almost like it was boiling. Then she noticed the horizon didn’t seem fixed anymore – it was approaching the ship. Rather, the ship was approaching it. Fast. Closer and closer. The end of the world.

She held on tight to the railing and screamed as the ocean fell away from the ship.

Haagrul guffawed behind her. “Silly girl,” he said in between catching his breath, “did you think this ship sailed water? This is an Eilhship, Shiaaj. We can travel throughout the heavens as we please.”

An Eilhship, Shiaaj thought. She seemed to have some basic knowledge of what Eilh was: the cosmic sphere containing the Outer Realms, and at its heart, the real world, Aurena. She wasn’t sure how she knew that, though. Another mystery.

“You’re a cruel tenvo, Haagrul,” she yelled, spinning around, “you know that?”

Haagrul wiped tears from his eyes. “Sorry. I thought you knew.”

Shiaaj turned back to look over the railing. The ship seemed to pierce through the inky void just like it was water, sending ripples out from the hull that she couldn’t see, but feel. She looked up at the Outer Realm, as it descended with Raam’s daily course. “We’re really going there,” she said.

“Of course,” said Haagrul solemnly. “Saints do what mortals cannot. Only Raam glides above us. You’ll see, soon enough.”

Shiaaj looked at her hands, and the concentric circles on her palms. Haagrul was right. She had much to learn.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

“It was around here somewhere, I swear it…”

The landsaint sighed as the young Dormarg tenvo scoured the field, using his large bare feet to kick the tilled dirt around the shoots of the tubers that grew underneath. “Are you certain this is where it fell, Kheloz?” she asked.

The diminutive Kheloz righted himself and bared his sharp teeth. “I’m certain this is where I saw it fall, yes ma’am.” He stroked his dense black beard with his heavy hands. He glanced around again. “Maybe it was in that corner of the plot…”

“So you don’t know where it is.” The landsaint’s brow-plates tilted downward in displeasure, shading her concentric pupils from the light and heat of Raam above.

Kheloz took a few steps away and crouched. He peered inside the massive leafy shoot of one of the crops. “Here! Here!” he announced, pulling away the leaves to reveal the small, brilliant sphere. “Give it a listen, what’s it say?”

The landsaint crouched by Kheloz and peered into the light. It was a fallen spirit, alright. Dislodged by some cruel chance from its place in the heavens. She closed her eyes, her brow-plates focusing on the sound.

The spirit spoke of fire, of flame, of conflagration. Fire to clear the underbrush from a forest. Fire to burn down a house. Fire to burn away flesh. Fire, indiscriminate.

“It’s a fire spirit,” the landsaint said. She pulled out her collection case and opened it. Within were small gemstones, each a different jewel, finely cut and faceted into neat round receptacles. She picked out a ruby of suitable shade, and closed the case.

“Yes!” Kheloz said, clapping his meaty hands. “I’ve always wanted to see this.”

“There’s not much to it, I’m afraid,” said the landsaint. She held up the ruby to the spirit, and gently coaxed it to enter with a thought. And suddenly the spirit faded from within the plant, and the ruby began to glow with all the colors of flame.

“That’s it? Really?” Kheloz crossed his black-red arms and furrowed his brow. “I was expecting a bit more of a show.”

“Before I give you this, I have to ask,” said the landsaint. “What does a Dormarg need a thoughtstone for? You can’t even listen to it yourself.”

“Oh, obvious,” Kheloz said with a wide grin, the yellow daggers of his teeth fully exposed. “I’m gonna sell it. Up in the city. Bunch of Aajakiri up there will pay handsomely for a wild-caught thoughtstone.”

“You can’t tell the difference between wild-caught and sky-caught,” the landsaint chastened. “That’s a myth.”

“Oh, since you’re a saint you know everything, huh?”

“More than you do, Kheloz.” The landsaint handed Kheloz the ruby thoughtstone and stood. “Good day,” she offered with a wave of her hand and a twist of brow-plates.

Kheloz, thoughtstone in hand, began to dance as the landsaint turned to return to the village.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

i think the mothers of bornsaints are also revered as “saintwombs,” and if you produce a saint, you’re more likely to produce more. but the children of saints themselves are very rarely also saints - although most saints are celibate and do not have children anyway.

(small reminder here: when i say “mother” literally all i mean is “person with a uterus that carries a child (either to term or not to term - mothers who miscarry or abort are usually still considered mothers)”. mothers can be of any gender, as can fathers. and most tenvo are not exclusively monogamous, and few are raised only by their two biological parents. most tenvo are raised communally.)

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

a common greeting/farewell in aurenna is “blesdy,” short for “blest day,” short for “have a blessed day.” some still say “blest day” but basically nobody says the full thing anymore

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Eilhship’s progress through the void seemed slow; Shiaaj figured they’d been traveling two or three days, and were just now almost at the Occultation. Yet she didn’t seem to grow tired, hungry, or thirsty. She asked Haagrul if this was a saint thing.

“More of an Eilh thing,” he answered. “In this sphere, these needs like ‘hunger,’ ‘exhaustion,’ and ‘thirst,’ are mere concepts that can’t affect us. Even these mortal sailors are immune.”

Shiaaj hadn’t noticed the Eilhship’s crew were mortals, not saints. But she hadn’t checked their eyes, so how could she have?

She felt her stomach. It didn’t feel full, but neutral. Her throat wasn’t parched, but neutral. Her mind seemed fresh and ready, and her eyelids didn’t risk shuttering her vision. She’d only known (by direct experience, at least) what these requisites for living felt like for a week. They had surprised her, when she was hatched, with their urgency. But now they were completely absent.

Something rocked the boat. Shiaaj threw out her arms for balance. “What was that?”

Before Haagrul could answer, the question answered itself: the great head of a massive beast, long, pale-scaled, serpentine in its movement, rose over the bow.

“An Eilhwyrm,” breathed Haagrul. His eyes taking in the wyrm, he added, “I’ve never seen one so close. How majestic! But this one seems rather small. A wyrmlet, probably.”

The Eilhwyrm turned its finned head to glance at the ship’s occupants with its huge green eye.

Then an arrow pierced the eye.

The wyrm loosed a scream, but not one of sound. It made Shiaaj’s brow-plates feel like they were being split open and torched. No concrete thoughts, only pain.

Haagrul turned to find the arrow’s source. It was a bow held by a landsaint on an upper deck.

“Fool of a landsaint!” he cried. “The wyrms are harmless!”

“It could have capsized the ship, regardless!” yelled back the landsaint.

The psychic shriek began to fade as the wounded Eilhwyrm fled into the darkness, but it never fully went away.

“Fool, fool, fool of a landsaint!” Haagrul shouted, spinning around with clear fear on his face. “It was a wyrmlet! They are never far from their mothers!”

A nearby Greshtal skysaint’s face fell. She called to a nearby sailor, “Tell the captain to make haste! We are in grave danger!”

“Aye aye,” responded the sailor, who sprinted up-ship towards the helm.

Not long after, the ship began to accelerate towards the Occultation. At the same time, Shiaaj heard a rumbling roar through her brow-plates. She grabbed Haagrul by the arm. “It’s coming.”

Haagrul took the lead, hollering across the ship at every saint who would listen: “Archers! Sorcerers! Ready your artillery! We need to slow that wyrm down!” He dropped his half-halberd and readied in his four hands balls of fire, lightning, ice, and stone. Others followed suit, archers nocking their arrows and sorcerers preparing various spells.

Soon it emerged from the void, truly colossal, its psychic voice making Shiaaj’s brow-plates numb and her brain rattle, as it approached the port side of the Eilhship. Its scales were a reflective black, only visible by how the scarce light played on it, and by its brilliant red eyes, like some malefic spirit cluster at night.

“Faster!” cried the nearby Greshtal skysaint, her four hands working in tandem to prepare some complex mysticism. “I’ll give us a boost, but it won’t last long!” After her gesturing was finished, she planted all four palms on the deck, and the Eilhship burst forward, Shiaaj almost falling over from the sudden acceleration.

The ship was fast approaching the Occultation now, but the wyrm seemed faster, gaining on them rapidly. Once in range, the saints began to assault it, loosing arrows and casting spells. Most hit true, and instead of slowing it down, they seemed to only enrage it further, quickening its pace, rampaging through the Eilh towards the ship.

“We need more speed, Dregor!” Haagrul shouted at the Greshtal who cast the accelerating spell.

“I’m giving it…all I’ve…got!” she groaned. But still she tightened her face, and somehow poured more magic into the vessel, giving it a bit more speed.

Shiaaj felt useless. She couldn’t shoot at the wyrm with either arrow or spell, and there was nothing she could do to hurry the ship along. She closed her eyes and grabbed for her Origin Stone by instinct. The opal was warm; the spirit inside seemed to be trying to tell her something. She tuned into it with her brow-plates:

It spoke of flight. It spoke of sailing the skies. It spoke of pure speed, unfettered by any obstacle. It spoke: now. Now. Now!

If the Eilh is just concepts made real, she thought suddenly, as if divinely inspired, maybe I can make concepts real, too.

She concentrated on the ideas the spirit showed her. She knelt and placed her hands on the deck and poured herself completely into making the ideas reality. Flight. Sailing. Speed.

The ship rocketed forward, knocking her and several other saints over. The last thing she saw before they entered the Occultation was the open maw of the Eilhwyrm. There were no teeth. There was no tongue. There was no throat. All was blackness.

And then her eyes faded into that same blackness.

2 notes

·

View notes