#big monkey and small child is a tried and true method

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

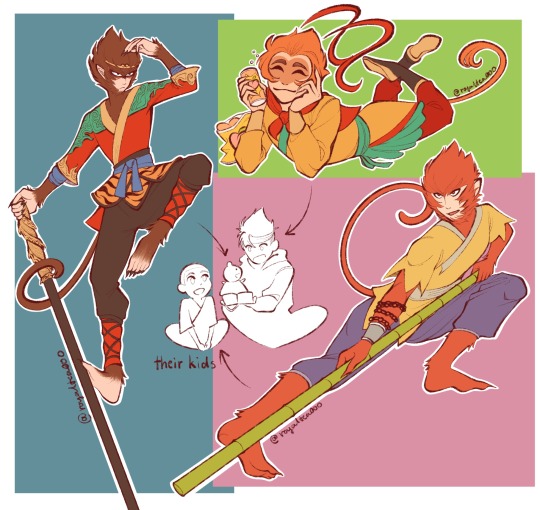

Me when I’m in a being coerced into parenthood competition and my opponent is sun wukong

#what is it with this guy and getting the gift of motherhood thrust upon him#big monkey and small child is a tried and true method#sun wukong#journey to the west#digital art#my art#jttw sun wukong#lego monkie kid#monkey king reborn#monkey king hero is back#yes let’s give the suicidally impulsive demon monkey a child#his ass does NOT wanna be a parent 😭#everytime I think I’ve seen the last swk movie more keep coming up that I’ve never heard of#animations favorite special little boy#he’s like the Chinese madonna#don’t read into that statement too much I say that about everyone#there’s so many of them#there being so many versions of sun wukong out there is lore accurate#his clone ability at work#also kinda laughing my ass off at how this dude is under 4foot but his energy is so tall people keep drawing him long#what +1000 aura does for you

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

‘UNCONSCIONABLE’: Outrage after researcher claims twin girls born in China are first ever genetically edited babies

‘UNCONSCIONABLE’: Outrage after researcher claims twin girls born in China are first ever genetically edited babies ‘UNCONSCIONABLE’: Outrage after researcher claims twin girls born in China are first ever genetically edited babies https://ift.tt/2KAMuzN

HONG KONG — A Chinese researcher claims that he helped make the world’s first genetically edited babies — twin girls born this month whose DNA he said he altered with a powerful new tool capable of rewriting the very blueprint of life.

If true, it would be a profound leap of science and ethics.

A U.S. scientist said he took part in the work in China, but this kind of gene editing is banned in the United States because the DNA changes can pass to future generations and it risks harming other genes.

Many mainstream scientists think it’s too unsafe to try, and some denounced the Chinese report as human experimentation.

More than 100 scientists have signed a petition calling for greater oversight on gene editing experiments.

The researcher, He Jiankui of Shenzhen, said he altered embryos for seven couples during fertility treatments, with one pregnancy resulting thus far. He said his goal was not to cure or prevent an inherited disease, but to try to bestow a trait that few people naturally have — an ability to resist possible future infection with HIV, the AIDS virus.

He said the parents involved declined to be identified or interviewed, and he would not say where they live or where the work was done.

There is no independent confirmation of He’s claim, and it has not been published in a journal, where it would be vetted by other experts. He revealed it Monday in Hong Kong to one of the organizers of an international conference on gene editing that is set to begin Tuesday, and earlier in exclusive interviews with The Associated Press.

“I feel a strong responsibility that it’s not just to make a first, but also make it an example,” He told the AP. “Society will decide what to do next” in terms of allowing or forbidding such science.

Some scientists were astounded to hear of the claim and strongly condemned it.

It’s “unconscionable … an experiment on human beings that is not morally or ethically defensible,” said Dr. Kiran Musunuru, a University of Pennsylvania gene editing expert and editor of a genetics journal.

“This is far too premature,” said Dr. Eric Topol, who heads the Scripps Research Translational Institute in California. “We’re dealing with the operating instructions of a human being. It’s a big deal.”

However, one famed geneticist, Harvard University’s George Church, defended attempting gene editing for HIV, which he called “a major and growing public health threat.”

“I think this is justifiable,” Church said of that goal.

In recent years scientists have discovered a relatively easy way to edit genes, the strands of DNA that govern the body. The tool, called CRISPR-cas9, makes it possible to operate on DNA to supply a needed gene or disable one that’s causing problems.

It’s only recently been tried in adults to treat deadly diseases, and the changes are confined to that person. Editing sperm, eggs or embryos is different — the changes can be inherited. In the U.S., it’s not allowed except for lab research. China outlaws human cloning but not specifically gene editing.

He Jiankui, who goes by “JK,” studied at Rice and Stanford universities in the U.S. before returning to his homeland to open a lab at Southern University of Science and Technology of China in Shenzhen, where he also has two genetics companies.

The U.S. scientist who worked with him on this project after He returned to China was physics and bioengineering professor Michael Deem, who was his adviser at Rice in Houston. Deem also holds what he called “a small stake” in — and is on the scientific advisory boards of — He’s two companies.

The Chinese researcher said he practiced editing mice, monkey and human embryos in the lab for several years and has applied for patents on his methods.

He said he chose embryo gene editing for HIV because these infections are a big problem in China. He sought to disable a gene called CCR5 that forms a protein doorway that allows HIV, the virus that causes AIDS, to enter a cell.

All of the men in the project had HIV and all of the women did not, but the gene editing was not aimed at preventing the small risk of transmission, He said. The fathers had their infections deeply suppressed by standard HIV medicines and there are simple ways to keep them from infecting offspring that do not involve altering genes.

Instead, the appeal was to offer couples affected by HIV a chance to have a child that might be protected from a similar fate.

He recruited couples through a Beijing-based AIDS advocacy group called Baihualin. Its leader, known by the pseudonym “Bai Hua,” told the AP that it’s not uncommon for people with HIV to lose jobs or have trouble getting medical care if their infections are revealed.

Here is how He described the work:

The gene editing occurred during IVF, or lab dish fertilization. First, sperm was “washed” to separate it from semen, the fluid where HIV can lurk. A single sperm was placed into a single egg to create an embryo. Then the gene editing tool was added.

youtube

When the embryos were 3 to 5 days old, a few cells were removed and checked for editing. Couples could choose whether to use edited or unedited embryos for pregnancy attempts. In all, 16 of 22 embryos were edited, and 11 embryos were used in six implant attempts before the twin pregnancy was achieved, He said.

Tests suggest that one twin had both copies of the intended gene altered and the other twin had just one altered, with no evidence of harm to other genes, He said. People with one copy of the gene can still get HIV, although some very limited research suggests their health might decline more slowly once they do.

Several scientists reviewed materials that He provided to the AP and said tests so far are insufficient to say the editing worked or to rule out harm.

They also noted evidence that the editing was incomplete and that at least one twin appears to be a patchwork of cells with various changes.

“It’s almost like not editing at all” if only some of certain cells were altered, because HIV infection can still occur, Church said.

Church and Musunuru questioned the decision to allow one of the embryos to be used in a pregnancy attempt, because the Chinese researchers said they knew in advance that both copies of the intended gene had not been altered.

“In that child, there really was almost nothing to be gained in terms of protection against HIV and yet you’re exposing that child to all the unknown safety risks,” Musunuru said.

The use of that embryo suggests that the researchers’ “main emphasis was on testing editing rather than avoiding this disease,” Church said.

Even if editing worked perfectly, people without normal CCR5 genes face higher risks of getting certain other viruses, such as West Nile, and of dying from the flu. Since there are many ways to prevent HIV infection and it’s very treatable if it occurs, those other medical risks are a concern, Musunuru said.

There also are questions about the way He said he proceeded. He gave official notice of his work long after he said he started it — on Nov. 8, on a Chinese registry of clinical trials.

It’s unclear whether participants fully understood the purpose and potential risks and benefits. For example, consent forms called the project an “AIDS vaccine development” program.

The Rice scientist, Deem, said he was present in China when potential participants gave their consent and that he “absolutely” thinks they were able to understand the risks.

Deem said he worked with He on vaccine research at Rice and considers the gene editing similar to a vaccine.

In this Oct. 9, 2018 photo, an embryo receives a small dose of Cas9 protein and PCSK9 sgRNA in a sperm injection microscope in a laboratory in Shenzhen in southern China’s Guangdong province. Chinese scientist He Jiankui claims he helped make world’s first genetically edited babies: twin girls whose DNA he said he altered. He revealed it Monday, Nov. 26, in Hong Kong to one of the organizers of an international conference on gene editing.

“That might be a layman’s way of describing it,” he said.

Both men are physics experts with no experience running human clinical trials.

The Chinese scientist, He, said he personally made the goals clear and told participants that embryo gene editing has never been tried before and carries risks. He said he also would provide insurance coverage for any children conceived through the project and plans medical follow-up until the children are 18 and longer if they agree once they’re adults.

Further pregnancy attempts are on hold until the safety of this one is analyzed and experts in the field weigh in, but participants were not told in advance that they might not have a chance to try what they signed up for once a “first” was achieved, He acknowledged. Free fertility treatment was part of the deal they were offered.

He sought and received approval for his project from Shenzhen Harmonicare Women’s and Children’s Hospital, which is not one of the four hospitals that He said provided embryos for his research or the pregnancy attempts.

Some staff at some of the other hospitals were kept in the dark about the nature of the research, which He and Deem said was done to keep some participants’ HIV infection from being disclosed.

“We think this is ethical,” said Lin Zhitong, a Harmonicare administrator who heads the ethics panel.

Any medical staff who handled samples that might contain HIV were aware, He said. An embryologist in He’s lab, Qin Jinzhou, confirmed to the AP that he did sperm washing and injected the gene editing tool in some of the pregnancy attempts.

In this Oct. 9, 2018 photo, Qin Jinzhou speaks during an interview at a laboratory in Shenzhen in southern China’s Guangdong province. Chinese scientist He Jiankui claims he helped make world’s first genetically edited babies: twin girls whose DNA he said he altered. He revealed it Monday, Nov. 26, in Hong Kong to one of the organizers of an international conference on gene editing. Qin is an embryologist in He’s lab.

The study participants are not ethicists, He said, but “are as much authorities on what is correct and what is wrong because it’s their life on the line.”

“I believe this is going to help the families and their children,” He said. If it causes unwanted side effects or harm, “I would feel the same pain as they do and it’s going to be my own responsibility.”

——

AP Science Writer Christina Larson, AP videographer Emily Wang and AP translator Fu Ting contributed to this report from Beijing and Shenzhen, China.

——

This Associated Press series was produced in partnership with the Howard Hughes Medical Institute’s Department of Science Education. The AP is solely responsible for all content.

Click for update news Bangla news https://ift.tt/2Sein3M world news

#metronews24 bangla#Latest Online Breaking Bangla News#Breaking Bangla News#prothom alo#bangla news#b

0 notes

Text

Hunters in Samalta: Chapter 5

Chapter 5: Wanderers, Soldiers, Secrets

The Hunter sat; still shaken, still a little broken, the wary fear of a frightened animal peering out from eyes, far too hard for one so young. But there was steel now, newly tempered. She was getting answers, and that meant progress. That meant the whole mess they had fallen into was going to be alright.

Probably.

Across from her, sitting on a slightly higher grime-caked brick ledge, sat the old mage. Eyes twinkled like glittering crystals from a mess of hair and ragged eyebrows. Dirty robes kept the warmth in those thin shoulders. By the twitch of his age-blanched mane, Allcre could well see he was still wearing that nostalgic grin, remembering days of glory under the command of the man she had been led to know as the Red King.

“Well,” she started, “the Red King walked out of the woods without a sword and without injury. I’m guessing whatever it was that you were setting up, it required the sword (and that spirit) as a crucial part of the end result. I’m interested, actually, in what you know about the origins of the sword, as well as some more of the power behind it.”

Balthasar leaned back some, brows scrunching up slowly. “Now, that… that’s a whole different tack. I’m not really sure I should tell you that. Or that I can. Why do you need to know? You don’t seem to be overly concerned with picking it up, or finding it like some ancient queen’s jade broach in a dead man’s barrow.”

Allcre took a deep breath - once, twice, a third time, exhaling slowly to calm herself as much as possible. She checked her light, setting it down to one side. In a quiet monotone, dulled further by the brick sewer structure, she told Balthasar as clear a recounting of the events of the previous week as possible. She began with their first survey of the Cursed Zone; spoke briefly on the encounter with Balthasar in the sewer and how it figured into the rest of the tale; described their hurried days of preparation and the razor-thin margin of victory pulled out of their encounter with the necromancer; recounted the arcanologist’s findings; described, with a voice shaking involuntarily, the visions from the horrible, horrible book.

All the while, the old man went from being a crazy old hobo under the streets of Samalta to something akin to a concerned uncle. “So you need to know about the last days of the war.”

“Yes.”

“And that means you need to know about the Red General, his sword, the Fusiliers, the whole shebang.”

“Exactly.”

The old man paused a moment, looking inward. “Your friend - this Pitt - used the power of righteous might to destroy the dog construct. His being and his sword shone. The difference is that the sword of the Red General burned. Whole legions of undead caught in its holy flame were turned to ash, liches were slapped aside like children, cackling apprentice necromancers were turned to sniveling whelps in the glare of the greatsword, and that was just in the black forest on our drive to the tower. Where the Red General strode in camp, men lifted their heads high, horses stopped panicking, sick men suffering from the Grey Plague felt comfort. He was a leader worthy of the respect, adoration, and bravery of every man under his command. I figure that whatever magic was in him, or in the sword, that would go a long way to getting the monkey off your backs. The soldiers in the ward might be too far gone.” He shrugged, an apology in a gesture. “The best we could do for the victims of the Grey Plague was keep them comfortable. The darkness took them all, in the end.”

“But how does that fit in with the sword? Or, vice versa I suppose,” asked Allcre.

“Honestly? It’s beyond me. Sure, to you I’m melting faces down here in the holes, but I was basically just a footsoldier. This was a minor outbreak, according to the veterans in the company. Apparently your Red General was a bright boy with a great idea, and like I said, I was just left here to watch over the place after the rest of the company rolled out after the big spirit worked his way in.”

“So what’s your opinion on the sword? Any chance we could, I don’t know, make another one? Find the old one? It seems like its a great tool to use against the darkness, such as it seems.”

Balthasar leaned back, scratching the back of his head. “No, no, I think wherever it is, it’s serving its purpose. On top of that, what little knowledge I have of that particular type of sword means that there’s approximately no chance and no way you could re-make it.”

“Right, alright, that’s fair… I guess.” The Hunter pondered a moment; “Who are the Fusiliers, really? The Third Hadirion Fusiliers; is that a place? Some sigil you follow? And why were you required to help out where the Utulian casters couldn’t work the right magic?”

Drawing out the word in hesitation, he answered, “Well, that’s a bit more than I can just casually reveal. Hadirion is… a land apart, you can’t get there by most conventional methods. The Fusiliers, we’re sort of your equivalent of - sappers, I think the word is - military saboteurs, and we can move unconventially. We were summoned by the Red King, so we could show up more or less at his whim.”

“Are you, or I suppose were you, part of his retinue?”

“His retinue? Soldiers in his train? Oh, no no no, we’re contractors. After a sort. We, um… this is awkward… We have a different patron deity. Your Red General was, and is, close to the White Steward, all about finding the best in people. We follow one known as the Blackguard - actually, scratch that, call him the Nightguard, too many connotations otherwise - and we’re all about overthrowing tyrants and safeguarding rebellions. Lots of business for demolition experts in that field, let me tell you.” He stopped a sentence from leaving his lips, having a thought which seemed to amuse him quite a bit. “Seems like I’ve failed in that sense; you’ve got quite the bureaucracy going, here.”

“That we do. Utulia basks in the glory of the White Steward, blessed be his name. The Red King rules by the authority granted by the White Steward and by the righteousness he carries with him.” The steel in the spine of Hunter Verily grew, and the frayed-at-the-edge look was almost pushed to the back. “Again; why were you required in lieu of Utulian casters? What did you end up doing when you made the Cursed Zone? More importantly, why in the world did you attempt to trap a necromantic incursion?”

“Because we were needed,” he immediately countered. He produced a small badge from somewhere within his tatters; a sable sircle with an embossed crescent moon of silver. As he passed the badge (cool to the touch, oddly heavy) to Allcre, a shimmering effect rippled over his features. In the dim light of the sewers, darkness gathered more strongly in the corners of the catchbasin, and Allcre’s fears rose sharply.

Where a wrinkly old man with bushy hair had sat, an entirely different creature relaxed calmly, with the same wry smile defining his features, altogether too familiar to be comfortable with. Short black horns sprouted from his temples, sweeping back over a smooth blue-skinned scalp and framing a pair of yellow-green eyes. His teeth and claws (claws!) were the same ebon as the horns, and hoofed feet terminated a pair of spry legs. He extended his hand, and numbly was given back the badge, whereupon the old man returned.

Some part of Allcre’s training said tiefling, but the shock at having actually seen a child of human (maybe) and devil in the flesh was hard to overcome. “Hold on, you have to know exactly how xenophobic this country is. Why help in the first place, why stay?”

“You think we would have been accepted looking like that? Not hardly, kid. We had to scrounge up some energy projectors to make the locals feel comfortable, using the tried-and-true flame-whip show. Sure, we roped some native elves into the venture, but the big movers were clever little devil spawn like me. Some of us lost our fathers to the darkness, to the Outside, and we wanted all kinds of vengeance. Petty human bigotry was about as interesting as a fleabite.”

As he rested back upon his hands, Allcre noted that devils, creatures of cold and darkness, would naturally be more comfortable in the sewers underneath a city than in the sun-baked streets above; a night jaunt would be comfortable, but not much more. Then, a few questions started multiplying, and then the natural result happened. “Who’s your father? Is your tail prehensile? Are your horns based on heritage?”, Allcre blurted out.

Balthasar looked moderately uncomfortable as he described his complete lack of knowledge on the matter (despite the fact his tail was, in fact, prehensile). He hadn’t grown up around other devils, just other tieflings, and was unfamiliar with the slightest facets of the cultures of hell. He cleared his throat, and asked gently, “Would you like to know about the wards?”

The technical discussion that followed helped, quite a bit, for Allcre to overcome the shock and for Balthasar to get over his temporary awkwardness. Balthasar’s scratched drawings and diagrams in the silt of the tunnel (too narrow and fine a scratch for just a finger) were familiar in nature, and Allcre delved into understanding the nature of the Cursed Zone, what Balthasar was calling the Dark Ward. They had set up a resonator, a standing wave, a magical short-circuit waiting to happen that would interact negatively with anything, magic or antimagic, crossing its line. Inside the ward, funky stuff would happen to any active magic-users, but contingencies had been established, such as the magical extraction of wounded or vulnerable from inside the line.

As far as its purpose and execution went, they had crossed the river, slapping the undead about (for this was not the greatest threat the Outside had ever offered), slagged a hole through the ground into the heart of the temple, let the big man in, and set up the resonator as quickly as they could. Once the Red General had finished his work, he walked out with his priests (clearing the area as he went), and the Fusiliers left via the unconventional path. The recruited elves had gone back west to watch their side, and Balthasar had stayed behind to watch the eastern side. The tower was probably their idea of some subterfuge, and in his esteemed opinion was just them being lazy.

“And what of the necromancer’s stone? How does that figure in?”, a much more at-ease Allcre asked.

“Probably a shard of a stone we missed on our way in or out,” Balthasar replied, though not as nonchalantly as he meant to. “Maybe it fell in the dirt and we missed it in the big damn hurry we were in, and some poor soul wandered in by accident and found it. That said,” he sighed, “it’s rarely as easy as being unlucky when it comes to the Outside.”

“How big do stones get? What are they made of?” No, there were simply more questions. That was all she could expect; more mysteries and threads the further she went into this ball of tangled knots.

“I’ve heard of building-sized chunks, even things that were recognizably buildings, even some monument-sized ones with glyphs all over them like foul graffiti. As long as it exists, and has the right properties (mineral, chemical, whatever), it acts as a beachhead for the terrible powers it acts as a focus for. Most of the identification comes from observation of corrupted processes; green fire, funky shadows, incipient madness, reality warping, and the classic aura signature. You know it when you see it.”

Allcre raised a finger; “Wait. Aura - that reminds me - what’s your opinion on the walker, the creepy figure we came across when we first got here?” She quickly described it; not particularly good woodcraft, non-detectable aura, ease of passage through the wards.

For the first time since she laid eyes on him, Balthasar was speechless for a good two beats, then started thinking. He proceeded to have far too much fun stroking his beard, thinking out loud through muttering below her hearing, amused a little bit at her impatience. After a sufficient interim, Balthasar slapped his palms down on the brick ledge. “Either it’s a soulless construct of flesh with a full cancellation spectrum, or a standing null aura with field permutations. No idea how that would be remotely possible, but that’s my thinking outside of the box. Granted, there’s quite a few things neither you or I know about the high-level workings of the magic in the Dark Ward - sorry, Cursed Zone, I like that better - so we can assume that they’re related. Coincidence is merely the universe being lazy.”

Allcre thought on it all for a moment longer. Balthasar had been a great resource, seriously an excellent reference for what was going on and an unparalleled measure for exactly how bad it could get. She rose from her seat, crossing over to where the hidden tiefling was sitting, and clasped his hands in hers. There was a moment of vertigo; she could feel the hard, cold hands and the roughness of the claws, but she could see the soft eyes that had remembered pain and strife, that knew the necessities of hiding.

“Thank you. Thank you so much. You’ve been really helpful, and you really didn’t have to be. You didn’t just bail on me halfway through my pestering. May the White Steward, blessed be his name, watch over you and keep you safe.”

Balthasar smiled to hid the grim truth behind it. “I’ll see if there’s anything more I can think of. I might be able to piece together what’s going on over in those wards. If you need me, remember; nighttime is better, if there’s work in the offing after dark.” His breath rose and fell, once and twice, as he looked to form the right kind of sentence. “The dark is rising again, no matter what anybody in this little country has to say. We will all need to be as ready as we can.”

<><><>

The archivist and the two hunters rejoined at the entrance to the crypts. Allcre had been able to run to the sewers and meet with the old tiefling (and be shocked) and then return while the rest of the book’s knowledge ripped into the minds of the two men who had remained, and then confer with the arcanologist. As such, the archivist and the Red Hunter were far more shaken than Allcre, and were vocally disturbed by the fact that the old man who had saved them was anything but human. Mostly.

Pitt’s haggard look faded slowly as Allcre relayed the results of her interview with the old mage. A knotted collection of brows and lips arrayed itself on the archivist’s face, however, as a surge of more questions (seriously, it never would end) rose in his mind. After Allcre finished her summary, the archivist cleared his throat and added to her knowledge the interpretation of the Book of the Dead by the arcanologist.

The thin little man had explained that the apparent motive behind this dark power is the the destruction and consumption of life and matter for its own sake, not for control or power, purely antithetical to the will to live of creatures and beings that are alive. The stones, it seemed, had not been produced so much as found, or (accompanied by a shudder) sent. Therein lay the problem; the stones are not foci so much as conduits.

“Apparently,” Pitt added, “the stones themselves are dangerous to speak of, so the fact that we are in a crisis already allows us to speak in guarded tones of these things. The will from Outside looks for any wayward mind to corrupt.” Pitt folded his arms contemptuously across his chest. “I admit that it is serious, but that’s just superstition.”

The archivist continued; scant records of visions given by the Book of the Dead exist, or have been written down, apart from the rites and power-usage it aims to teach. Most of the known ones were relevant to the situation at hand. In this case, and under these circumstances, the Book appeared to reveal that the Red King, in all his power, is a member of some force (or a subject thereof) explicitly oriented against the rise and appearance of necromancy, its power, and all that comes with it. Including, it seemed, the entities beyond the walls of reality.

Pitt and the archivist had grilled the arcanologist rather aggressively. Like Allcre, they had come out of the Book of the Dead’s hateful aura and been filled with a panoply of questions.

At first, the arcanologist had weathered the storm of questions like a good little stone in the path of the wave. Once he had shaken himself free of his own minor fugue, he had turned to the two men, and professed his own ignorance on much of the matter. The three of them had proceeded to put together as much as they could. The arcanologist took one of his rings off and proceeded to communicate directly with some of his peers in the Archive, in order to get up-to-date information as rapidly as possible.

Necromancers, according to the records, could be destroyed. The downside to destroying a necromancer was that such dark power was playing some twisted game that derived from a notion of guerilla warfare. Their purpose was to be destroyed, and to soak up as much energy and resource as possible while doing so. They existed for destruction’s sake, and fought for conflict’s sake, the more perverted and deranged the better. Trapping one, then, at first seemed to be a bit of a paradox for both sides, as it removed the threat and interrupted the progress without actually nipping the necromancy in the bud. Why, or how the Red King engaged in experimentation with the stones in precisely unclear. Regardless, whatever he did left at least one free-roaming shard of a stone in an otherwise successful trap.

It had been important to note, during their hurried deliberation, that necromancy did not appear to be magic per se, but an utterly corrupted reflection of it. Stones, nodes, necromantic foci, dark power, etc. could only be destroyed by using an equal or over-estimated quantity of non-necromantic material and/or energy to cancel out the dark aura. The hypothesis had been put forward that the null aura was a result of that cancellation, and the subsequent destruction had been the root cause of all failures to observe directly the power of the stones.

And what of those poor souls who are twisted by this power, as revealed by the Book of the Dead? No known manuscripts of a conversation with a necromancer or a lich existed, but it appeared that taking on the mantle of the dark power creates a twisted and perverted reflection of the former being. In some cases, it was clear that the corruption was similar to a brain-washing and subsequent re-developing of the host mind. They had become slaves to their own power. The few power-hungry madmen who went looking for the stones become the worst and most terrible tools in the claw of the entities from the Outside.

To the knowledge of the three men, going over their collective memories of battles and strife in Utulia since the fall of the Mage-Lords and the defeat of Arkadi, there had been no necromantic activity in the last 300 years, either within the bounds of the country or anywhere else. The arcanologist, who had studied this particular phenomenon, had actually seen the scrying reports; the undead population is minimal and static, no advance or growth could be determined. Somehow, the trapping of the ward did more than just trap a few stones, it thoroughly interrupted the designs of the entities of the Outside.

There had been an interesting moment when the arcanologist had gaped a moment in the middle of a sentence, scratched out a note, and stuffed it through a ring, and then waited impatiently before, three seconds later, a note came back. The arcanologist reported that he had been given permission to relay an important state secret; a huge power flux existed running through Goldspire Island, the seat of power in Utulia, the home of the Archive, and the throne of the Red King, but that it was unknown from where the power comes or to where the power goes. It might be possible that the sword was acting as a relay for that power, driving either some part of the wards or whatever was going on in the heart of the Cursed Zone.

That had led (almost at the same time as Allcre’s questions to Balthasar) to a rapid investigation of the Red King and the Dark Wars. The archive maintained the only remaining records of the Dark Wars outside the government-approved texts disseminated to the general population. The Red General had appeared at the gates of the capital out of the night, carrying a greatsword in a burlap scabbard and clad in unmarked leather armor. That sword would stay by his side, sheathed, his whole life. He spoke the language fluently, and entered the Samorian Military Academy (now defunct) graduating with honors. His first service in war was against an incursion of troglodytes from the north-west, and he was instrumental in Utulian victory. He rose like a star through the ranks; charismatic, wise, and humbly brilliant. The opening words of the Codex of the Red King were his motto from his earliest days:

Never cruel or hateful, never cowardly or fearful, for those I must protect, in the name of those I cannot save.

Along the way, he had picked up a red banner, a long cloth of scarlet dyed wool that he had embossed with the sigil of the White Steward; in those days, a popular deity for travelers and the poor, and not the center of a state religion. He had begun to amass a bit of a cult following, who became his primary officer corps in the first days of the Dark War. He had never been one to go to a temple, but on the night before he left Samor for the western front, he spent the entire time until dawn in a silent vigil by the chief altar, emerging at sunrise with a sword shining with a beautiful inner light clasped, unsheathed, in his hand. The rest is military history; a slog of death and chaos all the way to the tower, with the shining sword of the Red General leading the way. Eventually, he gave up the sword, and had begun the Arcane Prohibition.

<><><>

Their conversation had led the three of them to a secluded parlor within the temple, and as it wound down, they found themselves quieted by what they had learned, what they had discovered, what they had found. The silence stretched on, each of them with their own thoughts. The day grew long outside. The shadows held more weight of malice than before, hidden secrets in lengthening darkness.

The Archivist broke the silence with a long release of breath, exasperated and trying for calm. “Just for the sake of clarity, let me summarize here. We show up because someone, somehow, sets off a massive necromantic spell right in the middle of a town that ate a few pairs of Hunters. We find that a plague is being set by a huge skull of nastiness hidden in the sewers, deal with it, arrest an upstanding member of the community because someone, we still don’t know who apparently, made him do it. We find a similar skull in the Cursed Zone, which sets off alarm bells throughout regional governments. Now, according to Utulia’s best and brightest, we’re dealing with a necromantic outburst because, the last time this happened, the set-up the Red King put together with some tiefling friends to trap an incursion from outside reality missed a spot. That failure apparently is threatening to overwhelm the wards because, eventually, the dark power will throw off the epic-level sword that, somehow, is crucial to the whole thing because it is relaying the massive power flow coming from our country’s seat of legal and religious authority. If that happens, it’s the Dark War all over again, without the Red King to head off the necromancers killing everybody.”

Pitt chimed in. “Don’t forget the impossible man walking into and out of the wards freely on the far side of the shore.”

Allcre added, “Oh, and sneaky elves are involved somehow.”

“Right, yes, of course. Can’t forget the more inexplicable stuff.” He sighed again, more explosively. “Is it just me, or are we in over our heads? I feel like I’m punching well above my weight here.” He cast a sardonic look over at the two Hunters. “Unless, of course, it is just me, and all of this is just another day on station for you two.”

Pitt and Allcre looked at each other, eyes meeting for a brief second. Pitt’s mouth twitched in what could have become a cynical grin of his own. Allcre looked back at the Archivist and offered an apologetic shrug. The Archivist groaned, and put his face in his hands, gripping the fringes of his hair.

“We are kind of the best of the best,” Pitt said, more matter-of-factly than anything else. “We were specifically called in to deal with this by the Samor office. Those other Hunters that disappeared here were good, sure, but we’re probably in the top ten Hunters currently working in Utulia. That said,” he added with a note of worry, “there’s only so much that three people can do. More than just skill, the scale of this problem might be out of our ability to handle.”

The Archivist’s hands fell into his lap, his face carefully neutral. “My job, literally my only job, even if things go completely sideways, is to watch, to observe, to report. That’s what the Archive does. We’re the information network in Utulia. We know stuff. I have the training to stay alive, not to throw down against damn fools, crazy people, or, fates forbid, necromancers.”

Allcre sat up, brows furrowed in sudden thought. She turned to Pitt, hand on his shoulder, and nearly shouted, “Aleph Order!”

Pitt facepalmed. “Of course!” He started rooting through his kit, hands frantically searching through pockets and pouches. As he did so, he explained Allcre’s outburst, as she was scratching out a note on a piece of paper at hand. “The Aleph Order is the core of large-scale necromancy response, and rarely used, if ever. Basically, Hunters are ordered to deal with any incursion or uprising, but if things are too big for two specialists to handle, we call in the really heavy hitters. Our superiors, and theirs – five levels up, Allcre?”

Allcre looked up, eyes unfocused for a second. “Oh, at least in the short term. If it doesn’t get up to Cardinal Allavan, I’d be surprised. Level One?”

Pitt nodded. “Level One.” He turned back to the Archivist, whose shoulders had relaxed, knowing that someone, somewhere, could help. “Confirmed necromancy, multiple active constructs, high level of danger. We almost got killed and converted, so this is the next step in escalation.” He pulled a small amulet, a copper circle with a rotating outer ring, from the depths of a large pouch. “Or, at least, it was in our training. We almost forgot because you never expect to deal with this stuff.”

Allcre, having finished her short-form report, passed it to Pitt, who rotated the dial to the numeral one. A small aperture opened in the middle of the dial, and closed behind the slip of paper shoved through. The three leaned back in their chairs, a sudden tense silence rising like the tide.

“Now what?”

“Might take a while. We have plenty of work ahead of us.”

The Archivist raised a finger, cold eyes fixed on the Hunters. “We tell the townsfolk. If they ask, we must be honest. They are going to be right in the path of the hammer-blow, when it comes. They have earned the truth.”

<><><>

Pitt stood under a gray sky. Shield on his back, sword in his hand with tip just on the road, he could have been a statue if not for his sleeves and robe ruffling around his dark skin. He surveyed the small crowd in front of him, boys and young men backed by older fathers, with a few mothers and daughters worried in the back. He took a deep breath, and surveyed the troop.

A half-dozen young volunteers, glowing with pride they hadn’t yet earned, stood in front of a contingent of older guardsmen. Just looking at them, Pitt saw morale ready to break. Most of these men probably had friends currently withering away in the Plague Ward. They looked like someone they trusted, someone they believed in, was asking them to jump off the tallest building in town.

One of the old gaffers stood forward and cleared his throat. “Sir,” he asked respectfully, the way old noncoms talk to young officers, “no offense, but are there actually necromancers out there? Is that why we’re building up the walls? Is that why you – I mean – all those men ended up in the hospital?”

Pitt met his eyes, held them. "Any necromantic powers are being contained by the wards that the Red King himself erected. They are currently unable to break out from their cage, but that may not remain so. The only necromantic activity that has been found outside the containment zone is those injured in the assault, and they are being treated in the infirmary. We do not yet know the full strength of the threat. We are fortifying the town in advance of the arrival of more forces.

The Hunter looked out to the gathered troop, raising his voice. "We are not crossing the river to fight necromancers or their dark constructs. There is a camp, reported as being close to the other side of the river, may be in danger once the battle starts in earnest, so we are going to relocate them to our side of the border. There is a chance that this group may be sympathizers. We may need to subdue a threat to our security, which is why you are accompanying me.

"Let me make this clear, though. We do not know who is in that camp. Murder, even of someone not a citizen, is a crime punishable by death. I am authorized to pass judgement on all citizens of this nation. No one is to attack unless I give the order, and failure to abide by that order will meet no mercy. You are to be vigilant, though. Even if the camp is not hostile, you are still near enemy territory. Be prepared for anything that might happen. You are to protect the city, and the encampment. We will meet at the north gate at dawn.”

Pitt’s speech was a comfort to the would-be guardsmen, who started to filter out to the jobs they had been assigned earlier that day. To them, it made sense. Protection of citizens; circling the wagons; building up the walls. All the good stuff associated with the duties which they swore to follow. As speeches went, one of the better. One, still holding onto concern, raised his voice, telling his compatriots that he was going to ask a priest he knew to come anyway, “just in case.”

The younglings, on the other hand, positively swelled with pride as the speech went on. Pitt saw in them a shadow of someone he had been; full of the glory and vigor of a newly-ordained Hunter, missing the cynicism and jadedness that comes with experience. A couple of them started planning amongst themselves to bring some more friends; blacksmith's boys with arms like cord, tracker's sons with eyes and bows that could clip a hawk on a dive, carpenter's apprentices who were familiar with the woods on the far side of the Zedac. At the last, Pitt kept a chuckle to himself, thinking that the carpenter’s boys would have some sharp words for would-be heroes.

As the troop fell out, after a fashion, a worried father-looking guard came up to Pitt. “If you would be so kind, my good sir Hunter, could you keep the boys to the rear, if at all possible, where you can?” He wrung his hands nervously, and Pitt recognized one of the few guardsmen to survive the dreadful night in the Cursed Zone. “There are mothers in Samalta who would go to their grave in a week from the grief of having lost sons and husbands, sir; there are more than a few.”

He withered a bit under Pitt’s cold gaze. Pitt knew the regulations. The service required of all guards asked them to give their life for Steward, country, and King. There was room in the guard for neither weakness nor favoritism. The guard made his apologies, thanking Pitt somewhat incoherently for helping them in such a dark time, and went to join what few of his friends remained.

Pitt watched them go, eventually left alone in the open pavilion at the foot of the temple. It was all the more silent for the sounds of deconstruction happening out of sight, around corners in the town. He hoped, desperately hoped, that this would be a milk run, a simple escort mission. Samalta was a small town, made smaller by the plethora of empty houses. It might not be able to take another botched foray into the woods beyond the river. He might not be able to.

He squinted, watching the sun lower in the sky, start to dim behind the smoke still rising beyond the walls. He knew, like he could see into the quiet spaces of the night ahead, that sleep would evade him, that he would pore over maps and records for the entire night, trying to prepare as much as he could, trying to keep the nightmares away.

Pitt sighed, and slowly climbed the temple steps. Best to get started.

<><><>

Allcre walked down a narrow alley, following a middle-aged priest whose hands were dark against the sunbaked brick of the buildings to either side. They stopped at an intersection, as a wagon team took bricks and old lumber to the northern gate. The priest poked his head out, looking left, then right. He turned back to her, a smile below worried eyes on his face. “Just another block or so.”

The Hunter was led to the house of one Gaffer Harvod, a rotund man with skin midnight-black from field labor and hair cloud-white from age, who shared his house with the unofficial center of the rumor mill, his partner and the town midwife Rose Harvod. It was Rose that she wanted to talk to. The priest had made it clear that, while he wasn’t sure, just by dint of her knowing enough information about people in general, she would know some specific answers to Allcre’s questions. At the last corner, he turned to the Hunter with a bashful look on his face.

“Look,” he started, “this is actually sort of an embarrassing place to be for a priest. It would be unbecoming for someone of my position to stoop to asking a gossip such as she for help.”

Allcre raised an eyebrow at him. “Afraid of a woman?”

The priest winced, hard. “She’s vindictive and vengeful. She’s had no problem cutting ties with the religious community. I’d appreciate it if you didn’t mention to any of my superiors that I took you here.” For good measure, he looked around, checking the street. “Best to get you inside so some questions can get answered.”

The door was guarded by the eminent Gaffer Harvod, lounging on a chair made from what looks like the better parts of a wine tun, a wagon, and a floor covering. At the approach of the Hunter and the priest, the assembly groaned as he stood in greeting. “Father Myur! It’s been too long, my friend.” His voice rumbled like distant thunder, full of laughter and peace.

“Too long, indeed.” The priest offered a hand in shake, and was clearly dwarfed.

Harvod turned to the Hunter, and bowed as deep as his frame could handle. “It is an honor,” he intoned, “to be visited by one so honored as yourself.” Despite folding almost in half, his head was almost level with Allcre’s.

“A pleasure,” Allcre replied, “and I’m sure the same with your wife.”

Harvod straightened up, smiling. His massive hand pushed open a door, and a bellow for Rose was answered by an unintelligible yell from somewhere in the house. Some few children come tumbling out the door, and are kept penned by the Gaffer’s huge hands. Eventually, the town gossip herself came out. Before greeting Allcre, she glared briefly at the priest, who tried his best to ignore it.

Rose, all lean muscle and grey edges, offered a hand still wet from the washing. “Sorry about the little ones, ma’am,” she commented. “Odd kids from around the town end up here. Can’t keep track of ‘em all, so I just try to give ‘em a roof as I can.” Her eyes softened looking at the Gaffer playing with the kids, no older than eight. “Come on inside, then. Tea’s on.”

The tea came in mugs, thick raw ceramic, with a powerful scent that cleared out the head in a way Allcre was unfamiliar with. “Grow the herbs ourselves!” Rose called over, obviously proud of the handiwork. The Hunter took a draft, closing her eyes in pleasure. Rose was fussing about in the other room, talking to the Gaffer and herding the kids. The outer door clapped shut, and Rose rejoined the Hunter, nervously wiping her hands again on her apron.

“Sorry about all that,” she murmured, taking a quick sip of her own tea. “Have to make a space for company.”

“Don’t worry about it,”Allcre replied. “You said those children were wanderers, orphans in the town?”

“Something like that, but never orphans. Helped half their mothers give birth to ‘em. Feel like my responsibility doesn’t end there.” Rose took another sip of the tea, deeper this time. “Now, what did that stuck-up young priest want, bringing you all the way down here to this side of town?”

Not wanting to waste any time, and as Rose clearly was interested in getting down to business, Allcre focused on Rose, midwife, gossip, mother. “Tell me about the Wanderers. What do you know, what have you heard, what have you seen?”

Rose looked shocked. “Those old nomads? Why in the world do you want to know about them?”

Allce let a pause draw out somewhat dramatically, watching Rose’s eyes draw slightly wider. “We are all threatened by what lies across the river. Samalta may be the only safe place for anyone outside the walls. We may be safer inside if there are less people outside to be … taken.”

Rose drew in a sharp breath at the implication. She knew her history. She knew exactly what the Hunter was referring to. After a bracing drink from the mug, Rose began.

In a word, the result of Allcre’s examination of Rose’s knowledge revealed that the Wanderers are perfectly strange. They roamed all over the frontier, occasionally making it as far south as Depool, but only rarely, as their real home was the broad plains under the stars. They had never respected the hard border of the Zedac between the territories of the elves and of Utulia. Rose thought that by way of the Wanderers, agents of the Elven Kingdoms crossed the border, using their glammer and magic to pass unseen among crowds. Again, for the second time that week, the memories of a certain wary and silent gentleman in a crowded bar popped into Allcre’s mind. It made sense; using neutral-party, yet friendly, primitives to sneak into hostile nations.

“Proper pagans” is one of the less invective phrases Rose used to describe their level of primitiveness; apparently, they held to the old and more barbaric ways of worshiping the spirits of the land and the air and watching the stars for signs, dotting the plains with well-hidden shrines to local spirits. Apparently, to Rose’s own dramatic emphasis, the Wanderers were even guilty of breeding with elves, producing lamp-eyed young brats, smooth-skinned with pointy ears and penchants for things like music and history, none of which a strapping young lad should be caught studying.

That said, Rose concluded three cups of tea later, the Wanderers were mostly harmless. Occasionally, a few of the nomads would wander into town, barter a few trinkets for the odd tool, bit of supplies, or piece of news, and then dodge back into the grass with nary a coin flipped to the bartender. They never seemed hostile, just curious, almost like children gawping at things like walls and cobblestones and fountains. Rose herself had traded a few bundles of her own tea-leaves for necklaces of beads. She showed Allcre with a little shame; it was an exquisite piece, done in polished stone and bone and made of braided hair (Allcre’s guess was yak, but it had been a while). Unfortunately, Rose didn’t have any information as to the layout, population, or manners of the Wanderers. If anybody in town would have known, it would have been her, but, no dice.

Rose stopped for a minute. The Gaffer had drawn himself a stein of beer from some homebrewed stock, after offering some to the Hunter (who politely declined). She looked carefully for some sign at Allcre, who was steadily gazing back.

“Could I,” she started hesitantly, “go with you?” The Gaffer, mid-swig, frowned deeply, but said nothing. Rose flushed, almost afraid of what the answer would be.

Allcre did not immediately respond. She considered what Rose was, more than her function in this town. She was a natural gossip, already on tenterhooks with the community. She was smart, interested, curious, but clearly lacked the tact to handle what she herself had described as “dirty bastard-sons”. Speed was the essence of what needed to happen now, and having a potentially offensive guest would hamper her efforts entirely.

So, the Hunter leaned forward, placing a hand over Rose’s. “It might not be best,” Allcre said. “We need everyone to stay safe.” It was as good a lie as she could tell. The Gaffer looked enormously relieved, but said nothing.

Rose nodded, silently. Not having any more questions, the stay didn’t last too much longer, and Allcre found herself back in the street. It smelled hot, dusty, baked, so different from the herbal and fragrant coolness of Rose’s house. She had her heart in the right place, the Hunter thought. Just not her experience.

Allcre walked slowly back to the temple, having waved on the priest who accompanied her, then waited outside with the gaffer. She had so many questions. Questions about the nature of their enemies, questions about the nature of their allies, about the history of the place, about people, about things, about everything related to this inexplicable centuries-old undead-trap that seemed to be the central object of this whole damned mess. Her feet took her back to the temple, up the same steps at the same rate that Pitt had followed some time earlier. She found her quarters quiet, empty, though with the volume of thoughts rolling through her head it was barely registered. Allcre went through the motions of preparing for bed, still absorbed in the torrent of unknowns, evidence, and hunches that had started to barely precipitate out over the last few (horrible) days. Her lamp blown out, she climbed onto her cot and laid back.

Somewhere deep in her mind, she knew that sleep would not be forthcoming. There were too many questions to gnaw on, too many small pieces of information that could point one way or another, entire magical operations to consider and figure out. Perhaps it was for the best; with no sleep came no nightmares.

Night found Allcre staring at her ceiling through half-lidded eyes, watching, waiting, for answers, for the morning.

<><><>

The Archivist took a moment on the wall, looking around, looking north. The work on the walls had started in earnest. Honestly, he hadn’t expected the town to lean into their circumstance so readily, if with a grim set to their jaw. Dust hung thick in the air over places where abandoned buildings were being torn down to make Samalta safe. If it could be torn down, it was. If the walls could be built higher, they were. The Archivist scratched his beard pensively, absentmindedly. The real question was this: would it help? Would it even slow them down?

Haldaan, a shimmering mirage in the dim light of the summer evening, lay as it had for generations along the bank of the Zedac. The Archivist, in his mind’s eye, imagined the camp of the Red King’s army stretched between the walls of Samalta and that larger city beyond, river embankments piled higher to form defenses, barricades and earthworks stretching for miles. Allcre had told him about the chance encounter in a tavern en route, a strange man who pointed them towards the citadel which, even now, stood firm against time and circumstance. He dropped down onto scaffolds erected that afternoon, and disappeared from the sight of Samalta as soon as he hit the grass.

The road to Haldaan had been, and remained, an arrow-straight line from the waystation that Samalta had started out as. The sun-baked dust, every so often, didn’t quite cover the paving stones that had been carefully laid out by the Mage-Lords, and even the span of years since Haldaan had been abandoned to its ghosts had not yet erased the wagon tracks. The Archivist could also see, to his relief, no fresh or strange tracks on that path. His footsteps grew more confident, relatively; his passage might go unnoticed by wary hunters in the tall, dead grass.

His path stopped, briefly, as he came to the old canal entry. A barge-path had been laid into the plains, water diverted from the mountains and sent flowing down towards the frontier. A bridge crossed that canal just as it reached the Zedac, giving it more weight and wider banks than could be cut by the river in its current state. That bridge had been thrown down by the Red King. The path now forded the old canal, damming it entirely. At some point, the Archivist figured, there must have been a foul and stagnant lake that was a dream for irrigation, but there was only a light depression now. No tracks in the silty, open flat. More relief. He took note of a few loose stones, some larger blocks he could hide or rest under, and moved on.

Haldaan was close enough to be more easily examined now. The woods on the other side of the border had thinned out, with some of the trees even containing leaves, broad and green. They grew right up to the moat of the dusty city, and the Archivist smiled thinly, without mirth. Hiding places would need to be that much better if there was a wealth of them just around the city. He could see the thickness of the reinforced north-western walls, the broken road-gate, the fallen canal-gate. Through walls leaning precariously, he could see buildings in their last stages of total collapse. The years had not been kind to the urban center of the frontier.

The evening drew long shadows in its train. Broken foundations which had served mills, farmhouses, odd stables and taverns, stood like scattered teeth in the plain, more visible in the low light. The sun, now a dull red disc slipping towards the horizon, spent its light in the remains of the smoke from the trees had burned. The brick of the city proper took on a rusty hue, but the darker stone of the citadel went almost blood red.

In a flash, the Archivist looked back up to the top of the citadel. He had seen a flicker, a reflection perhaps, something metal. His powers of observation were excellent, and well-honed, but at this distance even he could only pick out –

Movement. Faint, and barely a guess, but his instincts (and mild paranoia) had served him well. There were people, definitely in the city, definitely in the citadel. He felt comfortable working in the dark, but so did practically anyone that could possibly be spending their summers in the wreck of a city.

Considering the angle of the light, the possible options for finding a safe refuge within Haldaan’s walls, and his general unease with the whole damn situation, the Archivist decided to stay outside the walls that night. He found a mill’s base to be suitable; from the city, he would be nearly impossible to see, but with the cracks and flaws in the old brick-work he had a vantage point on any approach to his safe spot.

Settling into a corner, where he could fail to get sleep like every other night that week, the Archivist looked out on that city. How it figured into their future, he wasn’t sure. He was going off of the word and tale of two Hunters, into a place that almost guaranteed contained enemies of the Utulian state, where safety could not be ensured.

The night fell uneasily, quickly. The stars came out, and their light was thin. A silence lay on the plains that was entirely unnatural. The Archivist waited, watching, bracing for the morning.

<><><>

A tense hour had followed the initial Aleph Level One report. Allcre and Pitt sent out some very simple orders to the effect that masons, carpenters, and any able hands available should get to work tearing down the abandoned and disused buildings that littered Samalta like sores. The walls, in such a state of disrepair as to be nearly useless, were to be repaired with the materials scavenged and recycled. The rest of the hour was spent planning between the three of them; where they should go, who they needed to pull behind the walls, further ideas and possibilities.

Messages started coming in a trickle, then a torrent. Authority was granted to Governor-Priest Hammaran to oversee the defense organization, with automatic deputization of the Hunters and station Archivist. Hundreds, perhaps thousands of troops were being drawn away from stations to Samalta; the Fourth Sappers had been mobilized, the Fifth and Eighth Infantry Divisions of the Second Legion were being re-directed off the northern front, the hitherto rumored Archivist Security Force would be brought in, all on top of fully twelve pairs of experienced Hunters. It would be a month at least for the disparate forces to arrive, so any preparations possible were ordered to happen.

The most chilling missive came late, direct from the Archive.

Based on the available information and the confirmed Aleph Level 1 situation, we have found it highly probable that the missing Hunters were lost to the powers of necromancy. Whether they have been sacrificed or converted remains unknown without further direct observation. By any means necessary, keep the situation contained until help arrives in force.

<><><>

The first suicides were found that night.

<><><>

And lo His burning sword banished night, driving back the lich and the risen and the foul necromancer. Sacrificing a great part of His power to destroy the enemy, He safeguarded all of Utulia, and by His watch we are kept safe to this day, never to see that dark foe rise out of the dark once more.

-Conclusion to the Cardinate-sanctioned account of the Dark War

0 notes