#biography of Elizabeth Kortright Monroe

Note

You mention in a reblog that it would have been very easy for Hamilton's family-in-law and enemies to discover his real birthdate. Genuinely, though - how? Records, if they were accurate or even kept, were inaccessible to them. Hamilton's West Indies contacts were all clearly muddled about his birth year (given the many contradictory answers - and frankly, I wouldn't know off hand when many of my close friends were born either). Surely his lying about it would have been trivially easy?

I hadn't meant by records, seeing as how we struggle to this day to find any concrete records of Hamilton's true birthyear. But yeah, his contacts. A good, but small, handful of Hamilton's associates from the West Indies were also located at New York, or the Colonies in general—And others at least remained in contact with him or his family. To name a few, Hamilton's father and cousin, Anne Mitchell, remained in contact with him, and Anne even visited and wrote to Eliza after his death. We have scarce surviving correspondence between Hamilton and his father, but if he was planning to let him move to NYC to live with them; it can be speculated that Eliza may have written a few letters to him, or he sent his own to others in New York.

Or the can of worms Edward Stevens' offers, he was Hamilton's boyhood best friend from St. Croix, and attended King's College where they attended the same class club and had shared some of the same friends, Nichoals Fish, Robert Troup, etc. If there was one person who we had to trust to know Hamilton's birthyear out of the surviving relatives or friends he had at the time, it would have likely been Stevens. Stevens's brother-in-law, James Yard, knew a good amount about Hamilton and his childhood considering later he was able to provide information for Timothy Pickering, who was planning to write a biography about Hamilton. The same one that mentions the possibility of Thomas Stevens being Hamilton's real father. Additionally, there is the Kortright family; Monroe's wife, Elizabeth Kortright Monroe, was a cousin of Hester Kortright Amory, Stevens's wife. And Elizabeth K. Monroe's uncle was one of Hamilton's employers from the Island, Cornelius Kortright, who worked with Nicholas Cruger. He helped handle Hamilton's financial dealings when he first made it to the Colonies. With all this being said, I highly doubt everyone was just keeping this a secret. Especially with their close relations to James Monroe, one of Hamilton's rivals, who could have easily used it against him.

And going back to Cruger, he would have definitely known Hamilton's contrasting age considering he was his employer at the Cruger Counting house. He also moved back to New York and saw Hamilton again, even once there were rumors spreading by the press that Hamilton could become governor with him as lieutenant governor in 1795. Catharine Church, the eldest Church daughter, married Bertram Peter Cruger, Cruger's son.

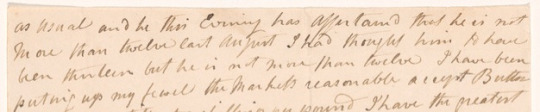

And all of Hamilton's associates from the Colonies roughly followed the 1757 belief. But you are right saying; “and frankly, I wouldn't know off hand when many of my close friends were born either.” Because as @46ten as recently added on, we are putting way too much emphasis on a birth year than what those of that day would. We value birth dates more strongly than when even as recently as a century ago, we did not. Today birth dates are now widely used for identification, but back when containing written documents was more of a hassle (As finding documents from Nevis has proven), not many were inclined to do such. In a day in age, where many families didn't even celebrate birthdays often, it wasn't much more than a passing thought for most. There is even a humorous story of Eliza forgetting JCH's birthday when he was young;

John is as industrious as usual and this Evening has ascertained that he is not more than twelve last August. I had thought him to have been thirteen but he is not more than twelve.

Elizabeth Hamilton to Philip Schuyler, [1804]

So, not only is it likely Hamilton wasn't even sure of his own birth year, but it wasn't a large deal back then. Does that mean it never would have been brought up? No, and I'm sure with all the previously mentioned close ties to Hamilton's in-laws and rivals, something would have noticeably not connected if so. And I doubt this many people were just in on Hamilton's whole facade. But it seems like a bunch of worthless mental gymnastics and risky lie for Hamilton to maintain for nearly 30+ years of his life, especially when many were out looking for anything to use against him.

#amrev#american history#historical alexander hamilton#edward stevens#james hamilton#anne mitchell#james yard#elizabeth kortright monroe#james monroe#cornelius kortright#nicholas cruger#history#birth year#queries#sincerely anonymous#cicero's history lessons#18th century#alexander hamilton

41 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello! I love your blog and find it very informative! Could you write something about AH relationship with James Monroe?

A lovely early friendship torn apart by political rivalry and misunderstandings that descended into harsh accusations, duel invitations, and never-ending Hamilton family hatred for the man? You can read the letters between them that Founders has here. I am unaware of AH ever discussing his opinion on Monroe in greater depth than what I’ve quoted below, and I’m completely unaware if Monroe ever offered a lengthy opinion on AH personally. There’s a new Monroe biography out (James Monroe: A Life by Tim McGrath) that may be more interesting than anything I write about.

But I’ll try. Things must have started out okay between them. They were both at the Battle of Trenton (Monroe was wounded). Monroe then served as aide-de-camp to William Alexander, Lord Stirling, whose brother-in-law was AH supporter William Livingston and daughter was Catherine Alexander, who would marry AH Treasury right-hand-man William Duer. They spent time at Valley Forge together, they both became good friends with Lafayette, etc. AH wrote positively of Monroe in 1779 to John Laurens:

Monroe is just setting out from Head Quarters and proposes to go in quest of adventures to the Southward. He seems to be as much of a night errant as your worship; but as he is an honest fellow, I shall be glad he may find some employment, that will enable him to get knocked in the head in an honorable way. He will relish your black scheme if any thing handsome can be done for him in that line. You know him to be a man of honor a sensible man and a soldier. This makes it unnecessary to me to say any thing to interest your friendship for him. You love your country too and he has zeal and capacity to serve it. 22May1779

With notes of recommendation from Hamilton, Lord Stirling, and Washington, Monroe became a lt. col, but with no field command available (AH certainly sympathized), he decided to resume his studies instead of continuing with the Army. He went on to become a member of the Continental Congress, etc.

In Feb 1786, Monroe (age 27) married Elizabeth Kortright at Trinity Church NY, with Rev. Benjamin Moore presiding (see here for my notes about the Hamiltons’ church affiliation). The Hamiltons may have attended; EH gave birth to Alex Jr. three months later. Elizabeth was the niece of Cornelius Kortright, who was a frequent business partner of Nicolas Cruger, AH’s old boss on St. Croix (AH worked for Kortright & Cruger 1769-1771). So Monroe - as did many others - likely had knowledge of AH’s personal background (and despite the current narrative surrounding AH, at the time almost no one seemed to care or consider AH’s background especially noteworthy; AH also freely introduced his cousins to friends, so it’s not at all clear that he ever thought he had something to hide and offered up the “blemish” of his parents’ relationship/his illegitimacy to several people).

But Monroe was a friend of Jefferson and Madison and ended up on their side politically (Monroe preceded Madison as an anti-federalist). His position in the Senate, and his authorship of articles in response to AH’s articles (written under several pseudonyms) all certainly aggravated AH.

And then there was the matter of Gouverneur Morris. In 1792, Monroe was one of the people trying to block the appointment of G. Morris as U.S. Minister Plenipotentiary to France. (Read an account of Morris’ actions in France/England here and enjoy the pettiness of his leaving Thomas Paine in jail.) In 1794, Monroe replaced Morris as Minister to France (1794 to 1796). He opposed AH as Minister to Great Britain (x) and his reasons are pretty sound and fair-minded (John Jay famously got the position and a treaty named after himself). Monroe was replaced in June 1796, both for anonymously publishing letters criticizing Washington and just not doing as the Federalists wanted, and replaced by Pinckney. Of course, AH played a part behind the scenes in encouraging his replacement and choosing Pinckney.

So by the 1790s they are political rivals, with Monroe writing in defense of Jefferson and Monroe blocking the appointment of AH’s friends/allies and AH interfering with Monroe’s business and encouraging his removal.

But in 1797, things got really personal. Rewinding to Dec 1792, Monroe was contacted by a jailed James Reynolds, who offered information about acting as AH’s agent/partner for speculation on gov’t securities. (Why Reynolds was in jail is a great deal more complicated than this, but I’m skipping all that.) Monroe investigated, got others involved, got the disclosure from AH himself that the money was actually because of blackmail over an affair with Maria Reynolds and produced letters showing this and gave letters and asked for copies of theirs, etc. (I think this part has been written about a lot, so I’m not going to go into further details). Five years later, the following was AH’s recollection of the matter (written to Muhlenberg and Monroe, 17July1797):

It is very true, that after the full and unqualified expressions which came from you together with Mr Venable, differing in terms but agreeing in substance, of your entire satisfaction with the explanation I had given, and that there was nothing in the affair of the nature suggested; accompanied with expressions of regret at the trouble and anxiety occasioned to me—and when (as I recollect it) some one of the Gentlemen expressed a hope that the manner of conducting the enquiry had appeared to me fair & liberal—I replied in substance, that though I had been displeased wtih the mode of introducing the subject to me (which you will remember I manifested at the time in very lively terms) yet that in other respects I was satisfied with and sensible to the candour with which I had been treated. And this was the sincere impression of my mind.

But actually, Monroe didn’t entirely believe AH’s account (”I hate you” point number 1) and conducted his own further interviews with Clingman and Maria Reynolds, which AH would only learn about in 1797 with the publication of pamphlet V of the History, but then Monroe pretty much left it alone, by his own account. He stated he sent all papers about this to a friend in Va (more on this below), and this is where the matter rested publicly for nearly five years.

But it’s not a real secret. By spring 1793, everyone in major political circles knows about it (and EH knew about it, it’s impossible for me to believe she didn’t). In under a week back in Dec 1792, Monroe, Wadsworth, Wolcott, Venable, Muhlenberg, Randolph, Webb, Beckley, and Jefferson all know, and Clingman talks freely. AH had permitted copies of letters to be made (and according to Monroe’s account, knew Beckley’s clerk had copied them), and on and on. BUT, no one is going to publish stuff about it - the confession of an extramarital affair would have been seen as a private family matter that would only serve to disturb “the peace of the family” - indeed, for AH naysayers then and historians since, claiming adultery was a convenient excuse if there was financial impropriety, because the matter wouldn’t be vigorously pursued further. (Philadelphia was a huge city for prostitution, and no one wanted the private sexual escapades of famous men broadcast to the world.) AH, I’m sure, knew everyone knew too, but worked from an understanding that no one was going to try to score political points on something that would expose his wife to public ridicule. But even though it was private, it was still Great Gossip! If AH was willing to taunt TJ publicly about Sally Hemings and, according to TJ, privately about his sexual pursuit/harassment 30 years ago of Elizabeth Moore Walker (wife of one of TJ’s best friend), and J. Adams is still repeating crazy gossip about AH 30 years later, you better believe there were references made to this affair at parties, gatherings, etc. EH dealt with it however she dealt with it, and I hope that AH’s “I have paid pretty severely for the folly” confession refers to some harsh treatment by EH.

And then in June 1797 Callendar began publishing pamphlets (lost to history except where AH quotes them in the Reynolds Pamphlet), some of which were gathered in some unknown order in his The History of the United States for 1796. Remember that Monroe was recalled from France in July 1796. It seemed to be a persistent belief of the Hamilton family that Monroe authorized and perhaps himself gave copies of the letters to Callendar for publication (”I hate you” point number 2).

And to be clear, because this gets muddled in some historian’s accounts - Callendar publishes AH’s account of his “particular connection” to Maria Reynolds and continues to goad him about it in published pamphlets and letters throughout June and July 1797 (the “harassment” of AH on this point in vague terms in pamphlets and newspaper letters actually started at least as early as 1795). AH’s confession in his own pamphlet was not an out-of-the-blue revelation of an affair that hadn’t already been publicly revealed.

Why would Monroe do this, in the Hamilton mind? Because he was pissed about no longer being French minister and blamed AH - he took a political dispute and decided to drag the Hamilton family into it. His delay in responding to AH, however, was likely seen as some kind of admission of guilt. On 5July1797, AH wrote to Monroe:

[Quoting from pamphlet V of the History] “When some of the Papers which are now to be laid before the world were submitted to the Secretary; when he was informed that they were to be communicated to President Washington, he entreated in the most anxious tone of deprecation, that the measure might be suspended. Mr Monroe was one of the three Gentlemen who agreed to this delay. They gave their consent to it on his express promise of a guarded behaviour in future, and because he attached to the suppression of these papers a mysterious degree of solicitude which they feeling no personal resentment against the Individual, were unwilling to augment” (Page 204 & 205). It is also suggested (Page 206) that I made “a volunteer acknowledgement of Seduction” and it must be understood from the context that this acknowlegement was made to the same three Gentlemen.

The peculiar nature of this transaction renders it impossible that you should not recollect it in all its parts and that your own declarations to me at the time contradicts absolutely the construction which the Editor of the Pamphlet puts upon the affair.

I think myself entitled to ask from your candour and justice a declaration equivalent to that which was made me at the time in the presence of Mr Wolcott by yourself and the two other Gentlemen, accompanied by a contradiction of the Representations in the comments cited above. And I shall rely upon your delicacy that the manner of doing it will be such as one Gentleman has a right to expect from another—especially as you must be sensible that the present appearance of the Papers is contrary to the course which was understood between us to be proper and includes a dishonourable infidelity somewhere.

And AH went ahead and wrote the following to editor John Fenno defending himself (6July1797):

For this purpose recourse was had to Messrs James Monroe, Senator, Frederick A. Muhlenbergh, Speaker, and Abraham Venable, a Member of the House of Representatives, two of these gentlemen my known political opponents. A full explanation took place between them and myself in the presence of Oliver Wolcott, jun. Esq. the present Secretary of the Treasury, in which by written documents I convinced them of the falshood of the accusation. They declared themselves perfectly satisfied with the explanation, and expressed their regret at the necessity which had been occasioned to me of making it.

But Monroe had just returned from France in June 1797, and he denied any prior knowledge of Callendar’s publication, and in general seemed to have had a “WTF!” reaction to AH’s sudden accusations. According to David Gelston’s account of the meeting between AH and Monroe on 11July1797:

Colo. M then began with declaring it was merely accidental his knowing any thing about the business at first he had been informed that one Reynolds from Virginia was in Gaol, he called merely to aid a man that might be in distress, but found it was a Reynolds from NYork and observed that after the meeting alluded to at Philada he sealed up his copy of the papers mentioned and sent or delivered them to his Friend in Virginia—he had no intention of publishing them & declared upon his honor that he knew nothing of their publication until he arrived in Philada from Europe and was sorry to find they were published. (my emphasis)

AH was so agitated that this conversation went downhill from there, seeing that “[AH] expected an immediate answer to so important a subject in which his character the peace & reputation of his Family were so deeply interested.” And then (”I hate you” point number 3):

Colo. M then proceeded upon a history of the business printed in the pamphlets and said that the packet of papers before alluded to he yet believed remained sealed with his friend in Virginia and after getting through Colo. H. said this as your representation is totally false (as nearly as I recollect the expression) upon which the Gentlemen both instantly rose Colo. M. rising first and saying do you say I represented falsely, you are a Scoundrel. Colo. H. said I will meet you like a Gentleman Colo. M Said I am ready get your pistols, both said we shall not or it will not be settled any other way. Mr C [John Church] & my self rising at the same moment put our selves between them Mr. C. repeating Gentlemen Gentlemen be moderate or some such word to appease them, we all sat down & the two Gentn, Colo. M. & Colo. H. soon got moderate, I observed however very clearly to my mind that Colo. H. appeared extremely agitated & Colo. M. appeared soon to get quite cool and repeated his intire ignorance of the publication & his surprize to find it published, observing to Colo. H. if he would not be so warm & intemperate he would explain everything he Knew of the business & how it appeared to him.

Monroe called him a scoundrel to his face! (After having been called a liar.)

And THEN, Monroe refused to sign a document absolving AH of any accusations of financial speculation with Reynolds (”I hate you” point number 4).

If I cod. give a stronger certificate I wod. (tho’ indeed it seems unnecessary for this with that given jointly by Muhg. & myself seems sufficient) but in truth I have doubts upon the main point & wh. he rather increased than diminishd by his conversation when here & therefore can give no other.

The above was sent to Burr on 16Aug 1797. AH had already pled his case to Monroe:

“...there appears a design at all events to drive me to the necessity of a formal defence—while you know that the extreme delicacy of its nature might be very disagreeable to me. It is my opinion that as you have been the cause, no matter how, of the business appearing in a shape which gives it an adventitious importance, and this against the intent of a confidence reposed in you by me, as contrary to what was delicate and proper, you recorded Clingman’s testimony without my privity and thereby gave it countenance, as I had given you an explanation with which you was satisfied and which could leave no doubt upon a candid mind—it was incumbent upon you as a man of honor and sensibility to have come forward in a manner that would have shielded me completely from the unpleasant effects brought upon me by your agency. This you have not done.

On the contrary by the affected reference of the matter to a defence which I am to make, and by which you profess your opinion is to be decided—you imply that your suspicions are still alive. And as nothing appears to have shaken your original conviction but the wretched tale of Clingman, which you have thought fit to record, it follows that you are pleased to attach a degree of weight to that communication which cannot be accounted for on any fair principle. The result in my mind is that you have been and are actuated by motives towards me malignant and dishonorable; nor can I doubt that this will be the universal opinion when the publication of the whole affair which I am about to make shall be seen.” 22July1797

In his mind, AH then believed he had to make a full accounting of the whole Reynolds debacle, since this jackass Monroe wasn’t going to sign-off on a denial of the whole matter of financial speculation on government securities. And back to the Hamilton family ire - it seemed that Monroe was not going to stop them from being slandered and dragged by doing what they felt he had already done - agreed that AH did not engage in financial speculation with Reynolds. Because Monroe would not acquiesce on that one matter, the Reynolds Pamphlet with all its detailed glory/humiliation where AH had to lay out his whole case was published, at least in the spin that occurred in the Hamilton family mind. (I’ve already written about the Reynolds Pamphlet here and here and briefly here and addressed a question about AH and infidelity here.)

Who was this “friend in Va?” Some historians have written this was TJ, but there are letters from decades later that Madison was the person who received the original letters and copies that Monroe had re Reynolds investigation, and they remained unopened until Monroe returned to the U.S. in 1797:

I have always understood from Mr. Monroe, that when he left this country he deposited with you, his packet of papers, relating to the investigation into the conduct &c of Genl. Hamilton—which was never opened, until it was returned by you to him, after his mission had terminated, and after the developement of its contents had been made from an other quarter. It would be very gratifying to me, if you have any facts, within your immediate reach, respecting the matter,if you would cause them at a leisure moment, to be communicated to me—The subject to which I refer, was, as you no doubt know, one of great feeling & excitement subsequently between Genl. H. & Mr. M., arising from causes of which I am aware, & particularly from the impression made on Genl. H. or the declaration by him of the belief, that the contents of the papers referred to, were made public by Mr. M—The children of Genl. H. have always indulged a feeling on this subject towards Mr. M. which renders it desirable that all the evidence in the case should be procured by his family. It has occasionally been hinted to me, that in a proposed publication of the Life of Genl. H., the subject might be touched, and it is equally my duty, as it would be my inclination, under such circumstances to have it in my power to do full justice to the character & memory of Mr. M. on this, as on all other occasions, where either might even by implication be assailed—I feel great reluctance in troubling you on the subject, but a conviction that you will appreciate my motives, impels me to do so. Samuel L. Gouverneur to James Madison, 1Feb1833

S.L. Gouverneur was the son-in-law of James Monroe (married their daughter) and nephew of Elizabeth Kortright Monroe. (Yes, he married his first cousin.) From the draft of Madison’s response (Feb 1833, Founders does not have a copy of the letter sent, if it’s still in existence):

I can only therefore express my entire confidence that the part Mr. Monroe had in the investigation alluded to, was dictated by what he deemed a public duty; and that after the investigation he was incapable of any thing that wd. justify resentful feelings on the part of the family of General Hamilton.

Of the public disclosure of the matter of the investigation, other than that from the avowed source, I know nothing; except that it could not proceed from the packet of papers deposited with me by Mr. M., which was never opened until it was returned to him, after his Mission had terminated.

Back to the main topic: the Hamiltons clearly saw Monroe playing a decisive role in the whole thing. But who was actually responsible for passing copies of letters to Callendar? Monroe was sure it was Beckley, former House clerk:

You know I presume that Beckley published the papers in question. By his clerk they were copied for us. It was his clerk who carried a copy to H. who asked (as B. says) whether others were privy to the affr. The clerk replied that B. was, upon wh. H. desired him to tell B. he considered him bound not to disclose it. B. replied by the same clerk that he considered himself under no injunction whatever—that if H. had any thing to say to him it must be in writing. This from B.—most certain however it is that after our interviews with H. I requested B. to say nothing abt. it & keep it secret—& most certain it is that I never heard of it afterwards till my arrival when it was published. Monroe to A.Burr, 2Dec 1797, in a letter that may have never gotten to him (entrusted to TJ)

Others at the time also believed it to be Beckley, though one historian suspected Tench Coxe too. Why was this ever published? Well, Callendar wrote in the History that it was because of the treatment of Monroe:

Attacks on Mr. Monroe have been frequently repeated from the stock-holding presses. They are cowardly, because he is absent. They are unjust, because his conduct will bear the strictest enquiry. They are ungrateful, because he displayed, on an occasion that will be mentioned immediately, the greatest lenity to Mr. Alexander Hamilton, the prime mover of the federal party.

Theodore Sedgewick told Rufus King it was Beckley, too and provides another motivation:

The House of Representatives did not re-elect Mr. Beckley as their Clerk. This was resented not only by himself but the whole party, and they were rendered furious by it. To revenge, Beckley has been writing a pamphlet mentioned in the enclosed advertisement. The ‘authentic papers’ there mentioned are those of which you perfectly know the history [46ten interjects: haha, some secret. So if Sedgewick and King know, Troup knows, Ames knows, G. Morris knows, etc. AH’s affair with Reynolds and the investigation was never a secret with this crowd], formerly in the possession of Messrs. Monroe, Muhlenberg & Venable. The conduct is mean, base and infamous. It may destroy the peace of a respectable family, and so gratify the diabolical malice of a detestable faction, but I trust it cannot produce the intended effect of injuring the cause of government.

So William Jackson is the second for AH, Aaron Burr the second for Monroe, and this Monroe-AH duel possibility stretched into the Winter of 1798 (x, x), having picked up again in December 1797 (Monroe replaces Burr with Dawson). TJ was still writing to Monroe about it in February 1798.

What had Monroe been doing that late summer/fall instead or figuring out how to conduct his affair of honor with AH? After an illness in August, oh, writing his own book (or having TJ ghostwrite it, depending on your views of Monroe’s intelligence) entitled A View of the Conduct of the Executive, in the Foreign Affairs of the United States, Connected with the Mission to the French Republic, During the Years 1794, 5, & 6, criticizing G. Washington and the administration every which way (published in Phila. 21Dec1797). GW, as he liked to do, made responses in the margins of Monroe’s little book; this editorial comment is hilarious: “GW’s remarks on Monroe and his book, taken together, comprise the most extended, unremitting, and pointed use of taunts and jibes, sarcasm, and scathing criticism in all of his writings.” Read that here.

So in the Hamilton mind, not only was Monroe trying to score points against Hamilton (and dragging private family matters into it), but he was criticizing GW too (and thereby AH, since even in retirement he continued to run the GW and Adams administrations, practically)! (”I hate you” point number 5.) In the first half of 1798, Monroe’s work got a lot of attention, earning the ire (and vocal and written condemnations) of Pres. Adams, of Timothy Pickering, and of many other Federalists. Monroe went back to Va. and appeared to lick his wounds and feel sorry for himself, based on his letters to TJ. I think it’s reasonable to speculate that Monroe is the “dirty fellow” alluded to in Angelica S. Church’s June 1798 letter to EH when the latter traveled to Albany - it was most likely seen that Monroe was the cause, or at least could have stopped, all the pain/attention of the public disclosure of the Reynolds affair. I don’t know if AH and Monroe ever really interacted after this. Monroe became Gov of Va, and then replaced Rufus King in 1803 as Minister to G.B.

EH and the Hamilton kids never forgot, see recollection here re. EH. Or watch a dramatization here. That Monroe remained a political rival of the Federalists and AH’s friends/allies also certainly didn’t help (Monroe & Madison and G. Morris continue at each other for many years.) On basic facts, it doesn’t quite make sense to me - I don’t think Monroe was culpable in the sharing of information, and I think he was being as fair-minded as he felt he could be - but there may have been additional encounters/statements/whatevers known to these parties that are now lost to history. There may also be fun details in JCH’s volumes on his father.

(For giggles, see this attached clipping: "the passage [in the Reynolds Pamphlet] in which Hamilton owns and laments his fault is admirably written.”

https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/imgsrv/image?id=uc2.ark:/13960/t90864f94;seq=231;size=125;rotation=0

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

First Ladies: Elizabeth Kortright Monroe

First Ladies: Elizabeth Kortright Monroe

Elizabeth Monroe was the wife of the fifth President of the United States, James Monroe.

Elizabeth Kortright Monroe

She was born as Elizabeth Jane Kortright on June 30, 1768 in New York City. She was the daughter of Lawrence and Hannah Aspinwall Kortright. Her father served as one of the founders of the New York Chamber of Commerce. She had four older siblings. Her mother died from the “child…

View On WordPress

#biography of Elizabeth Kortright Monroe#children of James Monroe#Elizabeth Kortright Monroe#family of James Monroe#First Ladies#wife of James Monroe

0 notes

Text

1755 or 1757?

[For this post, I'm heavily indebted to Newton's Alexander Hamilton: The Formative Years. Newton writes for over 12 pages and offers 109 glorious footnotes discussing the controversy over AH's birth year. I’m detailing this because it’s important to appreciate how many St. Croix ties AH had when I get into his friendships, that never-ending post.]

Until 1939, nearly everyone thought AH's birth date was January 11, 1757. 1757 is the birth year that AH used consistently throughout his life; it's the birth year his family and friends attested to. The few writers who objected to this year did so on the grounds that he was so small and delicate he likely appeared younger than he actually was, or that he could not have been employed so young.

In 1939, H.U. Ramsing published an essay on Hamilton's birth with extracts from the probate record for the estate of AH's mother. This document, completed in February 1768 by a clerk and signed by James Lytton, Sr, uncle of AH, in place of Peter Lytton, AH's cousin, states that she had "two sons, namely James Hamilton and Alexander Hamilton, one 15 and the other one 13 years old.*

This causes a flurry of re-evaluation of AH's birth year. Now I will note that 1939 is in a period of decline in AH's popularity. He gets hammered for his seeming love of banking, capitalism, aristocracy, protection of the rich, etc. That he seems to have spent his entire adult life lying about his age is just gravy.

Some historians accept the 1755 birth year, making the following Arguments:

The probate record must be correct;

AH's youthful poetry endeavors support a 1755 birth year;

AH was witnessing legal documents as early as 1766 for Beekman and Cruger, and there's no way a 9-year-old would have this responsibility or even have a job;

AH is a liar and schemer, so it makes sense that he would lie about his age for his entire adult life. Or (Chernow!) AH is so desperate to fit in he's even shaving two years off of his age, because he's such an insecure outcast in his own mind.

[Now there remains the possibility that AH may have thought he was born in 1757, when he was actually born in 1755. My grandmother did not know if she was born in 1908 or 1910. But she also knew that she didn't know - she wasn't declaring a birth year for herself the way AH did. As a contemporary of AH's, Newton offers up James McHenry as someone whose birth year is also unclear.]

Argument 1, the probate record must be the correct claim:

Records from the West Indies are highly unreliable. To quote Newton (pg 20): 'Dates and ages were recorded incorrectly, names were spelled and misspelled in every possible variation, and records were poorly kept, inaccurately transcribed, lost, damaged, or destroyed." One example of this is AH's mother. How many different ways are there to spell Rachel Fawcette Levine? Her burial registry is also incorrect on several details. [Newton produces several other examples of the inaccuracy of West Indian records.]

Refutation 1A: the clerk made an error, or the information was transcribed incorrectly.

James Lytton, Sr. was signing this document in place of his son, Peter Lytton. "Present for the two minor children and heirs was Mr. James Lytton on behalf of Peter Lytton." It's not clear why Peter was not present, only that he was designated as the person to complete the document and did not do so. Therefore, it's possible that his father, James, having to rush to finalize this document in Peter's place, simply did not know or mis-stated the ages of his nephews to the clerk. It also seems possible from the record that neither James nor Alexander were present to correct any misinformation. Flexner states that James Lytton may have deliberately lied about the ages of his nephews in order to increase their likelihood of employment, and then AH returned to his real age (the 1757 birth date) when he arrived in America. Though I don't really care what Flexner thinks because that speculation would be impossible to substantiate, Flexner's wrong about employment ages anyway, and Flexner makes stuff up all the time in The Young Hamilton.

Refutation 1B: James Lytton, Sr. made an error

In both A&B, the probate record is simply wrong.

______________________________________________________

Argument 2, AH's poetry points to a 1755 birthdate:

In April 1771, "A.H." submitted poetry for publication in The Royal Danish American Gazette, stating "I am a youth about seventeen." Hamilton's authorship of these poems can't be demonstrated. Even so, with a 1755 birth date, he would have recently turned 16, not 17. Of course, it's also possible Hamilton is the author, and lied about his age at the time of sending in the poems anonymously for publication to make himself appear older. [There's also lots of stuff in some biographies about AH's sexual precocity and what age it's more likely he would have written such poems, but those poems don't guarantee that "A.H." is sexually active - actually, they read as the opposite - a fantasy.]

In October 1772, The Royal Danish American Gazette published "The Soul Ascending into Bliss." Elizabeth Hamilton was very proud of this poem, sent stanzas of it to a friend, and stated that AH wrote it when he was 18. J.C. Hamilton wrote that AH wrote it when he was at King's College. It's likely that EH was JCH's source, so all that establishes is that EH believed her husband to have been born in 1757 and to have written this poem when he was at King's.

Refutation 2: The identity of "A.H." is unclear; EH likely mis-attributed the date of AH's poem.

______________________________________________________

Argument 3, AH was witnessing legal documents in 1766, so he was more likely 11, and anyway would have just been too young for employment if he were born in 1757:

There's zero evidence that 9 vs 11 was considered a substantial difference in maturity in young boys in the West Indies, so that an 11-year-old can serve as a witness, but a 9-year-old can't. A two-year difference in age is not that drastic.

Additionally, boys were often working by the time they were 7 in the colonies. Newton also provides the examples of Henry Knox, who started working at a bookstore at the age of 9; and Benjamin Franklin, who worked for his father at the age of 10 and by 16 was managing a paper. Also, as AH himself notes, he was still a 'lowly clerk’ in 1769, at the age of 12. He wouldn't become the de facto business manager of the firm for another couple of years, and he is without question a prodigy. The fact that it's unclear what happened to James Hamilton, Jr after his mother's death also points to both boys having to seek employment at early ages, likely at the time that James Hamilton, Sr. left.

Refutation to 3: There’s no evidence that the witnessing of a document by an 11-year-old carried more weight than that of a 9-year-old. Boys frequently worked at young ages in the colonies. It does not seem a two-year difference in age would account for such a drastic difference in responsibilities, including the ability to witness to legal documents.

______________________________________________________

Argument 4, AH lied about his age:

I could get into the number of contemporaries, even his enemies, who attest to AH's honesty and frankness throughout his life as Newton does, but I won't here. Instead, let's assume for a moment that AH did lie about his age.

Question 1: Why would AH want to make himself appear younger? According to some, because he wanted to more closely match the ages of his classmates at King's College. Students at King's College were between 12 and 19, with the average age of entrance as 15. If born in 1755, AH would have been 18 upon beginning his studies. Newton points out that one of AH's classmates, David Clarkson (enrolled in 1774), was born in 1751, so AH would not have even been the oldest person there.

Question 2: So if AH wanted to lie about his age to appear younger at King’s, when exactly did he start lying about his age? On that, historians who push the 1755 birth date can't agree, strangely. It seems obvious that because of the intertwining of people in AH's life, he really would have had to decide that he was shaving two years off of his age from the very time he enrolls at Elizabethtown Academy (the people he knows there carry through to King's), if not at the moment he arrives in America.

But wait, plenty of people who knew AH or knew of him in St Croix, also lived in NYC or traveled through there often!** His employers are based in NYC! Let's run down the people who would have had to go along with this lie:

Edward Stevens - AH's childhood St. Croix friend, who studied at King's College from 1770 to 1774. Their time at King's likely briefly overlapped, and they shared some of the same friends.

James Yard - brother-in-law of Edward Stevens and knowledgeable enough about AH and life in St. Croix to provide details of AH's background to Timothy Pickering (for Pickering's attempted biography of AH where he entertains the notion of Thomas Stevens as AH's real father).

Hugh Knox - possibly knew AH as early as fall 1771, definitely knew him spring 1772, travels to NYC intermittently also.

Ann Lytton Mitchell - AH's cousin who traveled back and forth between St. Croix and NYC and discussed AH's parentage with EH.

Nicholas Cruger and family- AH's St. Croix employer - originally from NYC and based there; Cruger's son marries the eldest John & Angelica Church daughter.

Cornelius Kortright and family - AH's St Croix employer - originally from NYC and based there; Kortright & Co handle AH's financial account when he first moves to NYC. Cornelius is the brother of Lawrence Kortright, Elizabeth Monroe's father - I think AH lying about his age would have been a fun detail to share with James Monroe, if true.

David Beekman and family - AH's St. Croix employer - originally from NYC.

Ship captains and merchants who traveled between NY and St Croix - not going to list them, except for George Codwise, NYC ship captain for Cruger who dealt with AH on St. Croix and years later hires AH as his attorney; he names his son Alexander Hamilton Codwise.

Note: AH would be employed as a lawyer for no fewer than 15 cases involving a Cruger, Kortright, or Beekman, and worked on cases dealing with merchants based in St. Croix. AH didn't cut ties to St. Croix as some may think.

AH lied about his age for 30+ years, and not one of the people above ever said anything? Maybe they didn't know that he was born in 1755? It seems highly unlikely that Stevens, Yard, Mitchell, Knox, Cruger, and Kortright would not have known AH's actual age in St. Croix.

And it's not like NO ONE knew that AH claimed to be born in 1757 until funeral orations were being delivered and his tombstone went up. For example:

Nicholas Fish wrote to EH that AH was "about eighteen" when he wrote his political pieces, and he's "certain" of this because they "compared and knew each other's ages, he being one year older than me.”

Benjamin Rush notes AH as "a young man of 21 years of age" in Oct 1777.

The Pennsylvania Gazette reports in 1781 that AH was 23 years of age in the previous year.

In AH's letter to his uncle William Hamilton (1797), he states that he was "about sixteen" (three months shy of 16) when he arrived in America (Oct 1772) and "by the age of nineteen" could earn a college degree and became an artillery captain (1776). Both point to him believing he was born in 1757.

James Kent wrote to EH in 1832 that AH died when he had not yet reached his 48th year.

So we have to believe that AH confidently went around telling people that he was an age consistent with having been born in 1757, and never gets called out on it even though there are several people around who could have done so and caught him in this lie.

_____________________________________________________

So let’s look at these options again:

The probate record is incorrect (either the clerk or Lytton made an error, or the probate record was later mis-transcribed);

The poetry authorship or dating is mis-attributed;

Historians don't know exactly how old one had to be in St. Croix in the 1760s to act as a witness on a property record;

AH and a number of co-conspirators lied about his age for to prevent him from being an older student at King’s College, and got away with it for over 150+ years, with no hint of this ever making its way into any record or correspondence, until the discovery of a 1768 probate record that has to be accurate.

As Brookhiser states, "[B]elieving that a man is more likely to know his own birthday than a clerk in a probate court, I will accept 1757." pg 16, Alexander Hamilton, American

*The date of James Hamilton, Jr.'s birth, whether he is older or younger than AH, whether he's really AH's brother, or whether he even existed at all(??!!) is also up for debate in Hamilton biographies.

**This is a huge thing to me that I'll get into in a few days, but gosh, AH was FAR from "an immigrant coming from the bottom" - he was wrapped in privilege with elite NYC/NJ people who knew him/of him from the very beginning of his American adventure.

76 notes

·

View notes

Text

Newton’s presentation on AH’s St. Croix years

Michael E. Newton, author of Alexander Hamilton: The Formative Years (2015) recently gave a presentation at Liberty Hall Museum. (See his blog for the video of his talk.)

Prior to Newton's discoveries, the earliest extant record we had of AH is the February 1768 probate record of his mother Rachel Lavien, discovered in 1939.

From the Danish National Archives (St. Croix) online, Newton has found 2 earlier documents:

1) Volume of registration and assessments for Christian settlers (April 22nd, 1767), an appraisement of the effects belonging to Master William Bond (Newton doesn't know who he is). At the bottom is the signature of an Alexander Hamilton; David Beekman, AH's boss's name is above, leaving Newton to think this is likely AH. Beekman, originally of NY, was a partner in the St. Croix firm of Beekman & Cruger, founded in 1766. We know AH worked there as a clerk as of November 1769, based on a letter to Edward Stevens, until the hurricane of 1772. [Newton hasn't found any other Alexander Hamilton living on St. Croix, though there were other Hamiltons on St. Croix, and a ship captain named Alexander Hamilton who visited St. Croix.]

2) In mortgage records of Christians in St. Croix (August 17, 1767) debt owed to David Beekman. First witness is Nicholas Cruger, second witness is Alexander Hamilton.

Implications to AH's biography - Newton is a strong believer that AH was born in 1757 (see his book for reasons why), which means AH at only 10 years old was serving as a witness to these documents. (There is a story in Papers of Alexander Hamilton that he served as a witness to a document in 1766 - this record has not been found.)

Newton believes, based on these records he has discovered, that AH started working for the Beekman & Cruger firm at least by April 1767. This would place AH’s job as clerk as the longest continuous job of AH's life

So was AH actually penniless or even financially struggling in St. Croix, as the Hamilton musical and other AH biographers state? According to Newton, no. RH had silverware and leather chairs - not living in poverty, though not rich. AH's uncle and cousin, whom he briefly lived with after the death of his mother, were the wealthiest people on the island. And AH already had a job - working as a clerk. Considering that he's single and doesn't have a family to support, he probably lives a reasonably comfortable life in St. Croix. He's not upperclass, but he's definitely middleclass, perhaps upper-middleclass by Newton's speculation. For mysely, this casts AH's self-identification in a different light - less "fake it 'til you make it" and more "this is where I've always been and belonged.”

A somewhat unrelated note: Elizabeth Monroe (James's wife) was the daughter of Lawrence Kortright, who was a business partner of Nicholas Cruger. Angelica Schuyler Church's daughter, Catharine Church, married Nicholas Cruger's son, Bertram Peter Cruger. I'm always fascinated by how much they were all in the same social circle.

5 notes

·

View notes