#both as a writer and a fan of literary analysis and as a woman

Text

I’m actually really interested in how the qsmp fandom treats its female characters at large versus how the female characters’ fans treat their character of choice. Because there’s a general consensus to Not Be A Dick To Women, because women are awesome (source: I am one.) But then you get to the individual fandoms for each character and you see that either you really aren’t allowed to criticize those characters at all, or all you do is criticize.

(And keep in mind I love both these characters I’m going to talk about and I literally try and watch every stream they’re part of if I have the time.)

For the first category, let’s look at the fandom surrounding qJaiden:

She’s a silly bird girl! She loves Cucurucho, but not the Federation. She’s actively friends with the creatures that have tortured and manipulated and kidnapped her own friends, but that’s fine because she has trauma. She’s a bit of a hypocrite when it comes to keeping and telling secrets sometimes, but that’s fine because she’s just silly!

This is the general qJaiden fandom perspective. If you call her a hypocrite, you have people calling you misogynist. If you say she’s a bit Weird for being besties with the bear that tricked her into thinking her son was alive and forced her on a death march just to laugh in her face and show her that she’s dead, you’re called a misogynist.

You criticize her at all, or you point out her flaws, you’re labeled a misogynist. Because Jaiden is silly! She’s never done anything wrong, actually, you either just hate women or you don’t watch her pov because you clearly don’t understand her character, which is Just A Silly Woman. There’s no nuance to her character past that, and acknowledging the fact that she’s morally gray can be Bad for ‘outsiders’, or even ‘insiders’ if you’re loud enough about it.

On the flip side, let’s look at qBaghera’s fandom:

qBaghera is useless. She needs to stay in her lane. She needs to tell others her personal lore. She needs to give up on running for president. She needs to be president. She needs to hang out with Forever and Bad more. She needs to be more of a revolutionary. She needs to take a step back and stay in her lane.

This is the general qBaghera fandom. Deal. It’s gotten to the point where ccBaghera has asked that people stop criticizing her character because she plays her character very close to her own personality. It’s nonstop people telling her how to play her own character, but they all claim to be ‘fans’. Her character doesn’t have any agency of her own to them, so she’s criticized, or, when she’s hanging out with The Boys she’s criticized for hanging out with The Boys, or she’s not hanging out with The Boys enough. That’s the kicker: she felt the need to stop hanging out with the other two members of Dramatrio because people were demanding she hang out with The Boys while ignoring her own personal lore.

These two examples are very different, but they both show the misogyny hidden beneath a thin layer of on-the-surface feminism. Not being allowed to criticize a female character is Not feminist at all, and criticizing a female character too much is definitely Not feminist.

And the thing is? Neither fandom seems to acknowledge the fact that they’re being Weird about their favorite female characters. Neither are allowing their favs to have any agency: Jaiden is always ‘Silly’ and doesn’t get to have any consequences or criticism, and Baghera can’t do anything without being criticized. But if you say anything about either character in a remotely negative or criticizing way, the individual fandoms will hound you for “being misogynistic” or “favoring male ccs/characters” because the qsmp fandom Is Not A Dick To Women. Because the fandom at large loves its female characters and ccs, the smaller, individual fandoms can get away with some weird shit in the name of “feminism” covering up misogyny within.

#discourse ig#I’ve been thinking about this for a couple of weeks actually#since baghera made her little announcement#it’s genuinely confusing to me yk?#both as a writer and a fan of literary analysis and as a woman

155 notes

·

View notes

Text

Well. I have now read the entirety of The Beetle. An exercise in incredulity if nothing else. Would I recommend this book to anyone. Yes, of course. As an example of victorian popular literature it is a stellar example of how to gather all the popular tropes into a trenchcoat and sell it as a book, a veritable treasure chest for literary analysis from the colonial, to gender to class anxieties.

As a good piece of literature. Absolutely not. From the way the plot never seems to kick in, to the way the villains motives are never actually explained, to the way the characters have barely any agency in their own story, The Beetle somehow manages to fall on its face on every conceivable way as both mystery, horror and action story. The Beetle truly is a masterclass in how to take a genre and then not utilise the aspects that fans of that genre would enjoy. We have a detective who doesn’t do any detecting. We have a monster who is killed off-screen in a public transportation accident. We have a group of “heroes” who fail to save anyone or do anything meaningful for the entirity of the novel. We are even teased a love triangle that doesn’t affect the plot, go anywhere, or impact the characters in anyway. If there is a story buried underneath all the “look what’s happening now” I failed to see it. The Michael Bay movie of victorian novels, the Beetle feels like watching a trailer for the newest marvel movie. There is a beetle! There is a damsel in distress! There’s a foreign cult! There are heroes! Is there a plot, or themes, or any emotional hooks? Go fuck yourself!

The Beetle doesn’t bring anything new to the table, but it does use the familar tropes in an exemplary unimaginative and unnuanced way. Egyptian oriantelism is rampant in victorian literarture and there are writers who have done much more interesting things with it. Even Stoker’s frankly not great The Jewel of the Seven Stars brings much more interesting version of the “ancient egyptian dead woman hypnotising british people”, while Machens Great God Pan manages to handle the “evil woman orgies hosted by shape-shifting half-human” with much more terror by not overusing the shock value.

The Beetle has a certain...dare I say Harry Potter-esque approach to being inherently mean-spirited and leaning on caricatures in its descriptions of caharcters, simplistic in its approach to evil, and fully confident that the reader will root for the heroes because they are “the heroes”.

In conclusion, am I glad that tumblr convinced me to read the Beetle? Absolutely. I am always in process of expanding my Gothic lit knowledge and for better or worse, the Beetle was the novel that outsold Dracula for a time, and therefore valuable for learning more about victorian era sensational lit. If I would actually ever get a professorship in an university, I would absolutely make a course about popular trends in victorian literature and then assign The Beetle as one of the non-negotiable essay topics. Why?

Because it would be INCREDIBLY funny and I think everyone in higher education should suffer a little bit more.

81 notes

·

View notes

Text

Racism (or the lack thereof) in The Unnatural

This blog is written because of a discussion of this topic on twitter and because I have a difficult time talking about this topic in the limitations of a tweet. Full disclosure - I am primarily of white ancestry and I certainly present as white and have lived my life with the privilege inherent in our culture of being white. I do have an academic background with a M.A. in the study of minority group relations which only means that I have taken an interest for many decades because I’m interested in people and this country and the history of people in this country. My disciplines associated to this study are rhetorical, literary and history. Also, in full disclosure The Unnatural is my favorite episode of the X-Files.

For anyone not familiar, there was a fan analysis that The Unnatural was one of the most racist episodes (comparing it to Babylon) in The X Files Series. Someone else responded to the fact that the show should have had writers of color to tell their own story. The right to this analysis and this belief is something I do not question. I I disagree which is my right.

I want to be clear- I do not disagree at all that writers’ rooms in Hollywood need to be diverse. I concur. I do not disagree that The X-Files have some episodes which are clearly racist and problematic. It does. I disagree with the premise that the only episode in the X Files of the 90s written to address racial segregation is in fact one of the most racist of the series or that it is “racist” at all.

Because The Unnatural is my favorite episode of the X-Files and I have an interest in how race relations is portrayed in television, I have read many of the reviews written at the time and afterwards. For people interested in the subject of how race is portrayed in the X-Files as a whole I recommend: Differences: The X-Files, race and the white norm by Elspeth Kydd in the Journal of Film and Video Winter 2001-2002. I am interested in reading the negative reviews specifically about race on the Unnatural if anyone wants to send me links. The one I shared on twitter is not, in my opinion, negative. It criticizes some elements, but over-all seems to enjoy the episode. https://thinkingraceblog.wordpress.com/2017/03/21/race-the-american-pastime-and-the-x-files-twenty-years-later/ It was the most critical, however, on the subject of race and the Unnatural I have found and I wanted to share an article that did not necessarily agree with my view but was written by a woman of color. There is another review which has concerns about the “magical black man” character as a trope but shares the viewpoint that the episode itself is so sincere in its sentiment that it makes up for this trope. There are many poor reviews on the sentimentality of the episode itself. Many reviews both good and bad talk about the fairy tale nature of the episode (the alien turn man ending) .David Duchovny, himself, admits he wanted a pinocchio ending. I like the fairy tale quality of Duchovny writing. Not everyone does, that is not the issue of this blog. The issue is racism which the black reviewers I have read do not seem to have as great a concern with as the posts on twitter.

To the argument that the existence of the Klan in the episode is racist, I would say that they are missing the point. The Klan exists in society. The Klan in this episode are the bad guys. Because of the fairy tale quality of this episode, they are not as scary as they might have been, but are none the less the bad guys. We are not suppose to sympathize with them. Instead we are supposed to understand the lesson at the end that whether we are black or white we bleed red blood.

Some people might make the decision not to read or watch anything about a person unless it is written or directed by a similar person. I can see and appreciate the rationale behind that. Why watch the Unnatural when I can watch a Spike Lee movie? I’m going to say watch them both but take the Spike Lee movie as a more serious portrayal and the Unnatural as an episode of the X Files that tried to go to a different awareness than most of the other episodes did but is still fundamentally an episode of the X-Files.

I’m a writer (albeit currently unpublished) and I am not going to restrict myself to only writing white women because if I did the characters would all have to be white women. I don’t want that for my life or for my characters. I want my characters to be diverse. I want Asian Women to write characters that are white males and LGBQT black writers to write straight characters some of the time because to restrict them or tell them not to do so might limit who reads or watches them. I don’t want that, but I also want more readers and viewers interested in characters who are not white or straight. I want us all to be more accepting of diverse authors and diverse characters and it concerns me that, in some type of effort to be “woke”, we would be more polarizing than accepting. Don’t tell everyone to go their respected corners. But its, also, ok to be critical of things we love. I’m not begrudging anyone that right to their opinion even as I share my own. The posts started the discussion and that seems to me to have some value which all us should respect.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

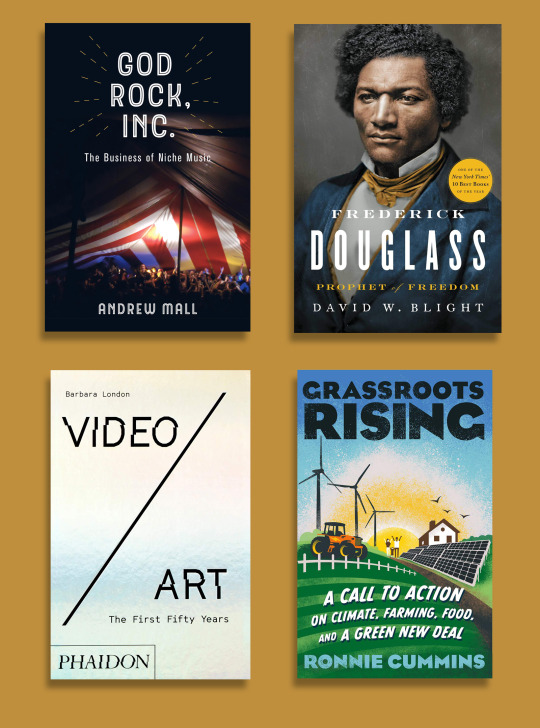

Weekend Edition: Non-Fiction

The great thing about non-fiction books is that we have lots of them in our libraries on almost any topic you can imagine. You can find one that interests you in the Main, Conservatory, Art or Science library. Here are a few recently published ones you might want to consider for your bingo box prompt, Non- Fiction.

God Rock, Inc. : the business of niche music / Andrew Mall

“Popular music in the twenty-first century is increasingly divided into niche markets. How do fans, musicians, and music industry executives define their markets' boundaries? What happens when musicians cross those boundaries? What can Christian music teach us about commercial popular music? In God Rock, Inc., Andrew Mall considers the aesthetic, commercial, ethical, and social boundaries of Christian popular music, from the late 1960s, when it emerged, through the 2010s. Drawing on ethnographic research, historical archives, interviews with music industry executives, and critical analyses of recordings, concerts, and music festival performances, Mall explores the tensions that have shaped this evolving market and frames broader questions about commerce, ethics, resistance, and crossover in music that defines itself as outside the mainstream”

Frederick Douglass : prophet of freedom / David W. Blight.

“The definitive, dramatic biography of the most important African-American of the nineteenth century: Frederick Douglass, the escaped slave who became the greatest orator of his day and one of the leading abolitionists and writers of the era. As a young man Frederick Douglass (1818-1895) escaped from slavery in Baltimore, Maryland. He was fortunate to have been taught to read by his slave owner mistress, and he would go on to become one of the major literary figures of his time. He wrote three versions of his autobiography over the course of his lifetime and published his own newspaper.” (publisher).

Video/art: the first fifty years / Barbara London

“The curator who founded MoMA's video program recounts the artists and events that defined the medium's first 50 years. Since the introduction of portable consumer electronics nearly a half century ago, artists throughout the world have adapted their latest technologies to art-making. In this book, curator Barbara London traces the history of video art as it transformed into the broader field of media art - from analog to digital, small TV monitors to wall-scale projections, and clunky hardware to user-friendly software. In doing so, she reveals how video evolved from fringe status to be seen as one of the foremost art forms of today.”

Grassroots rising : a call to action on climate, farming, food, and a green new deal / Ronnie Cummins

“A book that should be in the hands of every activist working on food and farming, climate change, and the Green New Deal."--Vandana Shiva A practical, shovel-ready plan for anyone wondering what they can do to help address the global climate crisis Grassroots Rising is a passionate call to action for the global body politic, providing practical solutions for how to survive--and thrive--in catastrophic times.”

Hot pants and spandex suits : gender representation in American superhero comic books / Esther De Dauw

"Hot Pants and Spandex Suits looks at representations of gender and its intersection with sexuality and race through the figure of the superhero. It places superheroes in their socio-historical context, particularly those published by the 'Big Two' publishers in the industry: Marvel and DC. The superheroes are: Superman, Captain America, Iron Man, Wonder Woman, Supergirl, Wiccan, Hulkling, Batwoman, Luke Cage, Falcon, Storm and Ms Marvel. Focusing on superheroes' first appearance in World War II up to their current iterations, author Esther De Dauw looks at how superheroes have changed and adapted to either match or challenge prevailing ideas about gender, including views on masculinity and femininity in the US military, attitudes towards American national identity, how gender intersects with sexuality for gay superheroes and how the lack of representation of minority communities impacts the superhero of color. What do superheroes say about and to us? Considering how gender, race and sexuality are often inextricably enmeshed in representation politics, this book offers an analysis that examines how all these different identities intersect and how that intersection itself produces ideas about gender. What is it that superheroes teach us about what it means to be a man or a woman when we're white or gay or Black? Following this analysis, it offers strategies and solutions to the question of representation within both the comic book industry and comic book scholarship. This book will be of interest to anyone interested in superheroes, including comic book scholars, gender studies' scholars, Critical Race scholars and scholars in the field of American Studies"-- Provided by publisher

Stamped : racism, antiracism, and you / written by Jason Reynolds ; adapted from Stamped from the beginning by and with an introduction from Ibram X. Kendi

"The construct of race has always been used to gain and keep power, to create dynamics that separate and silence. Racist ideas are woven into the fabric of this country, and the first step to building an antiracist America is acknowledging America's racist past and present. This book takes you on that journey, showing how racist ideas started and were spread, and how they can be discredited"--Dust jacket flap

"A history of racist and antiracist ideas in America, from their roots in Europe until today, adapted from the National Book Award winner Stamped from the Beginning"-- Provided by publisher

The undocumented Americans / Karla Cornejo Villavicencio.

"Traveling across the country, journalist Karla Cornejo Villavicencio risked arrest at every turn to report the extraordinary stories of her fellow undocumented Americans. Her subjects have every reason to be wary around reporters, but Cornejo Villavicencio has unmatched access to their stories. Her work culminates in a stunning, essential read for our times. Born in Ecuador and brought to the United States when she was five years old, Cornejo Villavicencio has lived the American Dream. Raised on her father's deliveryman income, she later became one of the first undocumented students admitted into Harvard. She is now a doctoral candidate at Yale University and has written for The New York Times. She weaves her own story among those of the eleven million undocumented who have been thrust into the national conversation today as never before. Looking well beyond the flashpoints of the border or the activism of the DREAMERS, Cornejo Villavicencio explores the lives of the undocumented as rarely seen in our daily headlines. In New York, we meet the undocumented workers who were recruited in the federally funded Ground Zero cleanup after 9/11. In Miami we enter the hidden botanicas, which offer witchcraft and homeopathy to those whose status blocks them from any other healthcare options. In Flint, Michigan, we witness how many live in fear as the government issues raids at grocery stores and demands identification before offering life-saving clean water. In her book, Undocumented America, Cornejo Villavicencio powerfully reveals the hidden corners of our nation of immigrants. She brings to light remarkable stories of hope and resilience, and through them we come to understand what it truly means to be American"-- Provided by publisher

#reading challenge#oberlin college libraries#oberlin college#reading recommendations#new books#OCL reads#nonfiction#non-fiction

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

“I heard your voice, so I came... Aoba-san.”

Hooo-boy, if that doesn’t get me emotional every single time. Call it my bias for eccentric bundles of sunshine and softness, or my crippling weakness for the secretly-handsome-and-devastatingly-earnest type, but you can’t change my mind: Clear is, hands down, DMMD’s best love interest. Character development-wise, thematically, romantically, he nails every trial thrown at him, gets his man, and proceeds to break your heart in the tenderest, sincerest way possible. I am hopping with Huge Fan Energy, so this post is gonna be unapologetically long and self-indulgent and grossly enthusiastic. Yeeeee.

————

Look, DMMD meta analysis has been done to death, I get it. This game is old. But I think it stands as testament to its excellent production that it’s still a game worth revisiting years later — especially during these times when social contact is so hard pressed to come by and we all rabidly devour digital media like a horde of screeching feral gremlins. (Have you seen Netflix’s stock value now? The exploding MMO server populations? Astonishing.) It’s pure, simple human nature to want to connect, to cling to members of our network out of biological imperative and our psychological dependency on each other. As cold and primitive at that sounds, social contact also fulfills us on a higher level: the community is always stronger than the individual; genuine trust begets a mutually supportive relationship of exchange and evolution. People learn from each other, and grow into stronger, wiser, better versions of themselves.

Yeah, I’m being deliberately obtuse about this. Of course I’m talking about Clear. Clear, who is a robot. Clear, who is nearly childlike in his insatiable curiosity regarding the human condition.

And it’s a classic literary tactic, using non-human entities to question the intangible constructs of a concept like ‘humanity’ — think Frankenstein, or Tokyo Ghoul, or Detroit: Become Human, among so, so many works in various media — all tackling that question from countless angles, all with varying measures of success. What does it mean to be human? To be good? Who are we, and where do we stand in the grand scheme of things? Is there even a scheme to follow? … Wait, what?

Jokes aside, there are so many ways that the whole approaching-human-yet-not-quite-there schtick can be abused into edgy, joyless existential griping. Nothing wrong with that if it’s what you’re looking for, except that we’re talking about a boys’ love game here. But DMMD neatly, sweetly side steps that particular wrinkle, giving us a wonderfully grounded character to work with as a result.

Character Design — a see-through secret

Let’s start small: Clear’s design and premise. Unlike so many other lost, clueless robo-lambs across media, Clear does have a small guiding presence early on in his life. It takes the form of his grandfather, who teaches Clear about the world while also sheltering him from his origins. It means he learns enough to blend sufficiently into society; it also means that Clear has even more questions that sprout from his limited understanding of the world.

Told that he must never remove his mask lest he expose his identity as a non-human, Clear’s perpetual fear of rejection for what he is drives much of his eccentricity and challenges him throughout much of his route. As for the player, the mystery of what lies underneath his mask is a carrot that the writers get to dangle until the peak moment of emotional payoff. Even if it’s not hard to guess that there’s probably a hottie of legendary proportions stuck under there, there’s still significance in waiting for that good moment to happen. And when it does, it feels great.

His upbringing contextualizes and affirms his odd choice of fashion: deliberately generic, bashfully covered from the public eye, and colored nearly in pure white - the quintessential signal of a blank slate, of innocence. Contrasted with the rest of DMMD’s flashy, colorful crew, Clear is probably the most difficult to read on a superficial scale, not falling into the fiery, bare-chest sex appeal of a womanizer, or the techno-nerd rebel aesthetic that Noiz somehow rocks. Goofy weirdo? Possibly a serial killer? Honestly, both seem plausible at the start.

And that’s the funny thing, because as damn hard as he tries to physically cover himself up from society, Clear is irrepressibly true to his name: transparent to a fault. He’s a walking, talking contradiction, and it’s not hard to realize that this mysterious, masked stranger… is really just an open book. By far the most effusive and straightforward of the entire cast, his actions are wildly unconventional and sometimes wholly inexplicable. But given time to explain himself, he is always, always sincere in his intentions — and unlike the rest of the love interests, naturally inclined to offer bits of himself to Aoba. It doesn’t take the entire character arc to figure out his big, bad secret — our main character gets an inkling about halfway through his route — and what’s even better is that he embraces it, understanding that his abilities also allow him to protect what he cherishes: Aoba.

So what if he doesn’t fit into an easily recognizable box of daydream boyfriend material? He’s contradictory, and contradiction is interesting. Dons a gas mask, but isn’t an edgelord. Blandly dressed, but ridiculously charming. Unreadable and modestly intimidating — until he opens his mouth. Even without the benefit of traversing his route, there’s already so much good stuff to work with, and sure as hell, you’re kept guessing all the way to the end.

Character Development — from reckless devotion into complaisant subservience, complaisant subservience into mutual understanding. And then, of course: free will, and true love.

At its core, DMMD is about a dude with magic mind-melding powers and his merry band of attractive men with — surprise! — crippling emotional baggage. Each route follows the same pattern, simply remixing the individual character interactions and the pace of the program: Aoba finds himself isolated with the love interest, faces various communication issues varying on the scale of frustrating to downright dangerous, wanders into a sketchy section of Platinum Jail, bonds with the love interest over shared duress, breaks into the Oval Tower, faces mental assault by the big bad — and finally, finally, destroys those internal demons plaguing the love interest, releasing the couple onto the path of a real heart-to-heart conversation. And then, you know, the lovey-dovey stuff.

Here’s the thing: as far as romantic progression goes, it’s really not a bad structure. There’s room to bump heads, but also to bond. The Scrap scene is a thematically cohesive and clever way to squeeze in the full breadth of character backstory while simultaneously advancing the plot. In this part, Aoba must become the hero to each of his love interests and save them from themselves. Having become privy to each other’s deepest thoughts and reaching a mutual understanding of each other, their feelings afterwards slide much more naturally into romantic territory. They break free of Oval Tower, make their way home, and have hot, emotionally fulfilling sex or otherwise some variation on the last few steps. The end.

That is, except for Clear.

Clear’s route is refreshing in that he needs none of these things — the climax of his emotional arc actually comes a little after the halfway point of his route. When Clear’s true origins are revealed, he comes entirely clean to Aoba, fighting against his fear of rejection but also trusting that Aoba will listen. It’s a quiet, vulnerable moment, rather than the action-packed tension we normally experience during a Scrap scene.

That doesn’t mean it’s prematurely written in — it simply means that he reaches his potential faster than the other characters. Because of that, he’s free to pursue the next level of his route’s development much, much sooner in the timeline: he overcomes his fears of his appearance, he confesses his love to Aoba, he leaves the confines of a largely dubious master-servant relationship and allows himself to be Aoba’s equal. Clear’s sprite art mirrors his emotional transformation all the way through, exposing him to the literal bone — and Aoba’s affection for him doesn’t change a single bit. Beautiful.

The whammy of incredible moments doesn’t just stop there, though. I don’t exactly recall the order the routes DMMD is ideally meant to be played in, but I believe Clear’s is meant to be last. And if you do, I can guarantee that it becomes a hugely delightful gameplay experience — in order to achieve his good ending, you must do absolutely nothing with Scrap. It doesn’t just subvert our player expectations of proactively clicking and interacting with our love interests; it grabs the story by its thematic reins and yanks it all back to the forefront of our scene.

In every route besides Clear’s, Scrap is a tool used to insert Aoba’s influence into and interfere with his target’s mind. Using his powers of destruction, Aoba is able to prune whatever maligned thoughts are harming his target; in any conventional situation, using Scrap is the right choice.

But one of the central problems in Clear’s route is his conflict between the impulses of his conditioning and his desire to live freely as a human would. Breaking free of Toue’s programming is what initially made him unique; growing beyond the rules imposed by his grandfather is what makes him human. In the final conflict scene, Clear’s decision to destroy his key-lock is an action of true autonomy, made with perfect understanding of the consequences and a sincere, selflessly selfish desire to protect someone he loves. In order to receive his good end, you have to respect his decision. It doesn’t matter which option you pick — by using Scrap, Aoba turns his back on every positive choice he made with Clear and attempts to exert his authority over him. This is Aoba becoming Toue; this is Aoba trying to reinstate himself as ‘Master’ right as he approved Clear as his equal. That’s blatant hypocrisy, and it doesn’t matter if Aoba is trying to do it for Clear’s ‘own good’ — that’s not Aoba’s call to make. If you truly wish to respect Clear’s free will, you will stand by. This is the truth of the moment: Clear has no emotional blockages that Aoba needs to fix. Believe in him, just as he believed in you.

The path to his heart is, and always has been, clear. Scrap was never needed from the start.

While Aoba might be the main character, Clear is undeniably a hero in his own route just as much. Tirelessly earnest and always curious, he leaps headlong into the unknown and emerges with his newfound enlightenment. He’s unafraid of weathering trials, even to the point of accepting death, and returns anew from oblivion to a sweet, cathartic ending. That’s about as textbook hero’s journey as it gets — if that doesn’t make him unquestionably, certifiably, unconditionally human, then I will scream.

And only finally… there is the free end. The final CG is like a throwback to our first impression of him: indistinct, purposefully obscured from proper view. But this time, we know better — and so does Aoba. Looks were never what mattered in Clear’s route. If you were patient, and you were open-minded, and you listened… well, what we realize now is that Clear was doing the exact same thing for you, too.

From a carefree, aimless robot-man with only the gimmick of “eccentric ditz” to carry him forward, we get a supremely more interesting character by the end: a man who has graduated from the well-intentioned but claustrophobic conditioning of his childhood; a weapon who has defied the imperatives placed on him by his creator’s programming; a wanderer who has, through unconditional patience and empathy, discovered love, and striven to become a better person for it. Who was it that ever doubted Clear’s character? He’s the goddamn goodest boy that ever wanted to be a real boy. Of course Clear is human. And in fact, he does it better than every single one of the actually human love interests. You can’t change my mind.

The Romance — kindness is really fucking attractive, okay.

Like I’ve said earlier, I have my Big Fan Blinds stuck on pretty tight. I might be conjuring sparks from thin air. But I think every choice was a deliberate creative decision on the writers’ part, and they deserve all the kudos for it — I’m just the lucky player who gets to enjoy it. But aside from Noiz (who I also think is a perfect darling as well — I could go on and on about him), Clear’s route is a model example for consent and healthy relationships in VN storytelling. This is reciprocated on both sides: never does Aoba infringe on Clear’s boundaries, and neither does Clear. They’re sensitive to each other’s needs and concerns; they ask for permission and stop when it isn’t granted (and when it is, boy do they get frisky — I’m not complaining!) I don’t need to say much more, because I think that consent is both fantastic and yes, incredibly hot (the scene in DMMD is tons more sad, go play Re:connect!). Good writing shows off the massive erotic potential enthusiastic consent puts into intimacy, and Aoba’s and Clear’s relationship is honestly a dream playground. The point is, I think Aoba and Clear genuinely do find equal balance in their relationship by the end of his route (and certainly through Re:connect). If you follow through Re:connect’s storyline, there’s even more thematic richness that comes through in the form of Clear’s greatest asset: communication. The couple get to discuss the long-term implications of them being together; they both offer concerns, points, and assurances to the other, and it’s just a soft, honest moment not so unlike the worries of a real relationship. Hearing is kind of Clear’s motif sense, but it’s really great to see that Aoba also subtly picks it up, really flexes his own communication skills to better engage with Clear.

Point is, Clear’s route spoke to me on a lot of little levels. Design-wise, he’s already got a ton going for him, and his story builds upon it rather than against it, enriching his development and grounding him a little more solidly in the DMMD universe (and in my heart). His route, aside from being emotionally ruinous, carries a pretty solid chunk of world-building (only beaten out by Mink’s and Ren’s, probably), and the romance feels organic, healthy, and realistic. He’s not the only one with an excellent route, but he’s my favorite. If you read through all of this, you’re a real trooper and I’m extremely impressed. Thanks for tuning in. Peace.

#dramatical murder#dmmd#aoba seragaki#clear#dmmd clear#long ass emotional screeching#lOL I FORGOT TO DRAW IN THE UMBRELLA HANDLE ahA#fixed

86 notes

·

View notes

Note

Is it just me or is all the "HER MIND!" stuff confusing, she might be smarter than the average pop star but that's not saying much, and there's definitely been many moments of "HER MIND" (derogatory)

Eh I think she’s very smart, both in terms of general intelligence and also savvy. Like idk if she’s good at literary analysis but like some of us went to school for that right like we weren’t necessarily awesome champions of literary analysis either we literally spent 4+ years reading Foucault and Baudrillard and Butler and writing treatises on repressed sexualities in Jane Eyere and Middlemarch and all sorts of other crap. Like I don’t know if it’s fair to say “she misinterpreted Rebecca” (which she very well might’ve done) and so us bitches with degrees in this are smarter than her.

But you can’t watch that recent Zane Lowe interview and tell me she’s dumb. That’s like my top proof rn.

Someone like Miley is very smart from a business sense POV - watch her Bangerz doccie if you have doubts, like not the performances the doccie on her image. Megan Thee Stallion is very smart too. Cardi has her moments (but also has some moments that are truly astounding). I don’t think Taylor is the only smart woman in music tbh and I’m not really here for implying she’s like the smartest and HER MIND (like you say) but I also do think she’s clever.

She’s also a brilliant songwriter especially as a lyricist that’s beyond a shred of doubt at this point. She’s got a real gift/natural talent for it but she has also worked on it over the years and has gotten better and more experimental. I think she’s a very good writer - her prose is also great (is it the best thing ever? No but it’s good 🤷🏻♀️) and that to me implies a pretty profound intelligence.

But we also know a lot of her fans think the sun shines out her bum which is the HER MIND I think.

Idk if I’m making sense lol but hope I did.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

All the World’s a Stage

In 1988, a socio-linguist at the university of Pennsylvania posted a note on the departmental bulletin board announcing she had moved her late husband’s personal library into an unused office. Anyone who wanted any of the books should feel free to take them. Her husband had been the chair of Penn’s sociology department. They’d married in 1981, and he died the following year at age sixty. Normally you’d expect the books and papers to be donated to some library to assist future researchers, but she’d recently remarried, so I guess she either wanted to get rid of any reminders of her previous husband, or simply needed the space.

At the time my then-wife was a grad student in Penn’s linguistics department, and told me about the announcement when she got home that afternoon.

Well, had this professor’s dead husband been any plain, boring old sociologist, I wouldn’t have thought much about it, but given her dead husband was Erving Goffman, I immediately began gathering all the boxes and bags I could find. That night around ten, when she was certain the department would be pretty empty, my then-wife and I snuck back to Penn under cover of darkness and I absconded with Erving Goffman’s personal library. Didn’t even look at titles—just grabbed up armloads of books and tossed them into boxes to carry away.

As I began sorting through them in the following days, I of course discovered the expected sociology, anthropology and psychology textbooks, anthologies and journals, as well as first editions of all of Goffman’s own books, each featuring his identifying signature (in pencil) in the upper right hand corner of the title page. But those didn’t make up the bulk of my haul.

There were Catholic marriage manuals from the Fifties, dozens of volumes (both academic and popular) about sexual deviance, a whole bunch of books about juvenile delinquency with titles like Wayward Youth and The Violent Gang, several issues of Corrections (a quarterly journal aimed at prison wardens), a lot of original crime pulps from the Forties and Fifties, avant-garde literary novels, a medical book about skin diseases, some books about religious cults (particularly Jim Jones’ Peoples Temple), a first edition of Michael Lesy’s Wisconsin Death Trip, and So many other unexpected gems. It was, as I’d hoped, an oddball collection that offered a bit of insight into Goffman’s work and thinking.

Erving Goffman was born in Alberta, Canada in 1922. After entering college as a chemistry major, he eventually got his BA in sociology in 1948, and began his graduate studies at The university of Chicago.

In 1952 he married Angelica Choate, a woman with a history of mental illness, and they had a son. The following year he received his PHD from Chicago. His thesis concerned public interactions and rituals among the residents of one of the Shetland Islands off the coast of Scotland. Afterward, he took a job with the National Institute for Mental Health in Bethesda, Maryland. His first book, The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life, which evolved out of his thesis, came out in 1956, and his second, Asylums, which resulted from his work at N.I,M.H., was released five years later. In 1958 he took a teaching position at UC-Berkeley, and was soon promoted to full professor. His wife committed suicide in 1964, and in 1968 he joined the faculty of the University of Pennsylvania as the chair of the sociology department, a post he would hold until his death in 1982.

Citing intellectual influences from anthropology and psychology as well as sociology, Goffman was nevertheless a maverick. Instead of controlled clinical studies and statistical analysis, Goffman based his work on careful close observation of real human interactions in public places,. Instead of focusing on the behaviors of large, faceless groups like sports fans, student movements or factory workers, he concentrated on the tiny details of face-to-face encounters, the gestures, language and behavior of individuals interacting with one another or within a larger institutional framework. Instead of citing previous academic papers to support his claims, he’d more often use quotes from literary sources, letters, or interviews. He created a body of work around those banal, microcosmic day-two-day experiences which had been all but ignored by sociologists up to that point. After his death he was considered one of the most important and influential sociologists of the twentieth century.

Without getting into all the complexities and interpretations of Goffman’s various theories (despite his radical subjective approach, he was still an academic after all), let me lay out simpleminded thumbnails of the two core ideas at the heart of his work.

Taking a cue from both Freud and Shakespeare, he employed theatrical terminology to argue that whenever we step out into public, we are all essentially actors on a stage. We wear masks, we take on certain behaviors and attitudes that differ wildly from the characters we are when we’re at home. All our actions in public, he claimed, are social performances designed (we hope) to present a certain image of ourselves to the world at large. The idea of course has been around in literature for centuries, but Goffman was the first to seriously apply it in broad strokes to sociology.

His other, and related, fundamental idea was termed frame analysis, the idea being that we perceive each social encounter—running into that creepy guy on the train again, say, or arguing with the checkout clerk at the supermarket about the quality of their potatoes—as something isolated and contained, a picture within a frame, or a movie still.

He used those two models to study day-to-day life in mental institutions and prisons, note the emergence of Texas businessmen adopting white cowboy hats as a standard part of their attire, analyze workplace interactions and the complicated rituals we go through when we run into someone we sort-of know on the sidewalk.

I first read Goffman in college when his 1964 book, Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity, was used in a postmodern political science course I was taking. In the slim volume, Goffman studied the conflicts and prejudices ex-cons, mental patients, cripples, the deformed and other social outcasts encountered when they stepped out into public, as well as the assorted codes and tricks they used to pass for normal. When passing was possible, anyway. At the time I was smitten with the book and these tales of outsiders, being a deliberately constructed outsider myself (though as a nihilistic cigar-smoking petty criminal punk rock kid, I had no interest in passing for normal). I was also struck to read a serious sociological study that cited Nathaniel West’s Miss Lonelyhearts—my favorite novel at the time—as supporting evidence.

Thirty-five years later, and after having read all of Goffman’s other major works, I returned to Stigma again, but with a different perspective. Although my youthful Romantic notions about social outcasts still lingered, by that time I’d become a bona-fide and inescapable social outcast myself, tapping around New York with a red and white cane.

Goffman spent a good deal of the book focused on the daily issues faced by the blind, but in 1985 those weren’t the outsiders who interested me. Now that I was one of them myself, I must say I was amazed and impressed by the accuracy of Goffman’s observations. He pointed out any number of things that have always been ignored by others who’ve written about the blind. Like those others, he notes that Normals, accepting the myth that our other senses become heightened after the loss of our sight, believe us to have superpowers of some kind. (For the record, I never dissuade people of this silly notion.) But Goffman took it one step further, noting that to Normals, a blindo accomplishing something, well, normal—like lighting a cigarette—is taken to be some kind of superhuman achievement, and evidence of powers they can barely begin to fathom.

(Ironically, he writes in Asylums that the process of socializing mental patients is a matter of turning them into dull, unobtrusive and nearly invisible individuals. Those are good citizens.)

Elsewhere in Stigma Goffman also points out—and you cannot believe how commonplace this is—that Normals, believing us to have some deep insights into life and the world, feel compelled, uninvited and without warning, to stop the blind on the street or at the supermarket to share with them their darkest secrets, medical concerns and personal problems as if we’d known them all our lives. He also observed the tendency for Normals to treat us not only like we’re blind, but deaf and lame as well, yelling in our ears and insisting on helping us out of chairs.

Ah, but one thing he brought up, which I’ve never seen anyone else mention before, is the fate awaiting those blindos (or cripples of any kind) who actually accomplish something like writing a book. It doesn’t matter if the book had absolutely nothing to do with being a cripple. I’ve published eleven books to date, and only two of them even mention blindness. It doesn’t matter. If a cripple makes something of him or herself, that cripple then becomes a lifelong representative of that entire class of stigmatized individuals, at least in mainstream eyes. From that point onward he or she will always be not only “that Blind Writer” or “that Legless Architect,” but a spokesperson on any issues pertaining to their particular disability. I was published long before I developed that creepy blind stare, but if I approach a mainstream publication nowadays, the only things they’ll let me write about are cripple issues. Every now and again if I need the check, I’ll, yes, put on the mask and play the role. But I’m bored to death with cripple issues, which is why whenever possible I neglect to mention to would-be editors that I’m blind. And I guess that only supports Goffman’s overall thesis, right?

Well, anyway, a series of four floods in my last apartment completely wiped out my prized Goffman library (as well as my prized novelization collection), so in retrospect I guess that professor at Penn probably would have been better off donating them to the special collections department of some library.

by Jim Knipfel

7 notes

·

View notes

Note

What do you think of Jon + Dany?

Well I’ve already answered what I think of the romantic pairing (Spoiler! Some pretty hot, scathing tea and a couple of fart noses sprinkled in)

So I’ll answer this question a bit differently - keep in mind my opinion is pretty much book-based (though I feel like the show is at least trying to give off this vibe, even if they fall short a bit with Jon’s characterization and are further along in portraying where I think Dany will eventually end up):

Both are grey characters straddling the line between light and dark. It’s prob why there are some interesting parallels on the surface - its when you get to the end of these parallels that they fork off a bit in their handling or their decisions. While there are better narrative examples of this i think a great metephor just to get the basic idea would be that wonderful image in the show of Dany and Jon holding out their hands in the White Walker battle, which seems a perfect parallel to when Ygritte did the same when the two were scaling the wall, but ends much differently; Jon grabbing Ygritte’s outstretched hand, and Jon rejecting Dany’s. A parallel that forks off with different, often opposite, decisions.

So Both are grey characters, however, if there is a line perfectly in the middle, I see Jon as off to the light side of that perfect 50/50 line, and Dany on the darker. Thats not to say they both haven’t had their problematic moments and what not (the show has been less effective in portraying Jon this way and tend to leave out a lot of these instances). Or their good moments either. And they’re both still firmly in the grey area. But i feel the image definitely sums the whole ‘hero of the other side’ thing. They’re foils, inverse of one another, two different sides of a coin. Which is why its so easy to mistake them as the same breed, for lack of a better term; a purposely misleading narrative that will most definitely be used to enrich and shock the story, especially toward the end. Its a plot device GRRM will surely use, considering how infamous it would make his stories, and he is definitely a good and well thought writer if nothing else.

And the further down the rabbit hole the two of them go, the further their decisions and world views cement and push them toward their roles as “hero” and “villian”. But neither term actually exemplifies their respective character because they’re still grey colored, and those terms are literally (and metephorically) black and white. And since they’re both sympathetic characters, whose POVs we see regularly, and their journeys takes place over many books and a long period of canon time, its harder and harder for the GA to not get invested (hence many’s shortsightedness) - which is less an indictment on say the audience’s intelligence or understanding of the story (esp for those that don’t see it; its only the people who purposefully refuse to respectively and openmindedly consider the theories and opinions of others that i think really merits the term ‘ignorant’), and more a mark of how compelling and amazing GRRM is as a writer to pull such a tricky thing off. I doubt many writers could do the same.

I sympathize immensely with Dany and her hard, often horrible journey. And for the most part she’s just trying to do the best she’s able under difficult circumstances. How i interpret her, however, is not as the heroine of the story, despite her good intentions, more as the anti-hero, or the tragic hero:

The tragic hero is a longstanding literary concept, a character with a Fatal Flaw (like Pride, for example)[or in Dany’s case ignorance, an easy temper, and shortsightedness] who is doomed to fail in search of their Tragic Dream [in the show its more the iron throne, for the sake of the IT, and Book!Dany is getting there for sure, but for the most part rn in the books its Westeros for the sake of this intangible dream of ‘home’] despite their best efforts or good intentions.

Concept wise, a tragic hero can be BOTH an antagonist and/or a protagonist, and even as the “villain” is usually recognized as the Tragic Hero by the audience’s sympathy toward them/their plight.

I looooove Dany’s character. She was originally my all time favorite, and though after the first book is no longer my first favorite, is still in my top five. She’s well fleshed, complicated, good, bad, and open to lots of different interpretation. I know some people absolutely hate her (more show fans I think), and while many consider me an “anti” esp. as I don’t think she’s a “hero”, or that she makes a good, effective queen, and I still believe she is doomed for darkness - that doesn’t mean I hate her. I still love her regardless of all this. I feel bad for her. And i think the story would severely suffer without her in it. I also think she’s a character right out of Homer or Shakespeare’s writing, or Tolkien’s, or a Greek tragedy.

If I had to choose which character I loved more: it would be Dany. If I had to choose a character i think will be closer to villian than a hero out of the two, it too would be Dany. The beliefs are not mutually exclusive.

And I can see how it seems I might be “picking” on Dany to some, as I dont mention or discuss Jon nearly as much, but honestly thats just because I find Dany wayyyyyyyyyyyy more interesting and thought-provoking of a character

There’s a lot of accusations that people who criticize Dany are ‘hating on her’ just because she’s a strong, powerful woman, esp. when they dont speak out about other characters as much, and Im sure that may be the case for some as this fandom does have a good amount of bad apples, but thats not why I criticize or appear to focus on her at ALL. For instance, I dislike and hate book!Tyrion (show Tyrion is fine) WAY more than I criticize Dany (who i like). Like vehemently dislike him. I just don’t feel the need to talk about it because the analysis is pretty straight-forward and doesn’t change much. But Dany always changes, at least for me, especially the more I read different theories or interpertations that either coincide or differ from my own. I never get tired of peeling her layers like an onion, or reevaluating my opinion of her. This ended up being way longer than I thought lmao.

#anti jonerys#daenerys targaryen#im a little on the fence about putting it in this tag but its not anti really ??? Still ill tag#anti daenerys#just in case and if any of you want me to take it down for some reason i will#jon snow#i dont want to be disrespectful#but its also an anlysis of her character and not like omg i hate her!! shes horrible!!#mine

75 notes

·

View notes

Text

Are You Alive?

A Literary Analysis of Jeffery Deaver’s “Afraid”

Some authors struggle to provide readers the most thrilling roller coaster ride of a suspense narrative; nevertheless, thriller writer Jeffery Deaver can build psychologically complex characters, both heroes and antagonists. “Afraid” -- his original short story mainly revolves around Marissa and Antonio. Marissa is a beautiful woman with features of the north. She had been a runway model and afterward took up fashion design which she loves. However, she is forced to take over their family business -- managing the arts and antiques operation. Antonio, on the other hand, is a man full of mystery. They first met at a gallery on the Via Maggio, where Marissa’s company occasionally consigned arts and antiques, and there they found common ground with each other. Antonio took Marissa to his house in Florence. However, the journey from Florence’s Piazza della Stazione to Antonio’s house, an ancient, two-story stone mill with small windows barred with metal rods, made Marissa uneasy. Along the way, she encountered strange events. She obtained information from a strange old woman who gave her clues on what had happened to Antonio’s “wife” -- Lucia. The story went on with Marissa and Antonio arriving at the place and with Antonio retelling a boy who drowned. Marissa later realized that Antonio was a murderer who had killed his wife and the boy based on what she saw in the basement. When she was about to fall into despair, she saw the letter Antonio left her and found out that all of this was an elaborate horror script designed by Antonio. There have been many turning points in this story. The author titled the short story "Afraid" to allow readers to think about its connection to the content. How does this title relate to the following story? Does this title relate to the main character? Then we bring these questions to Jeffery Deaver’s story.

Jeffery Deaver is an international number-one bestselling author who writes American contemporary crime/mystery fiction. He has written prolifically and published more than forty novels, a non-fiction law book and three collections of short stories. His novels have appeared on bestseller lists around the world. His books are sold in 150 countries and translated into twenty-five languages. He is also a lyricist of a country-western album, and he’s received dozens of awards. Born on May 6, 1950, Jeffery Deaver grew up in Glen Ellyn, Illinois. He studied journalism from the University of Missouri and later earned a degree in law from Fordham University. He began his professional career as a journalist then he practiced as an attorney. These career opportunities provided him with ample knowledge to embark on his writing career. His debut stand-alone novel Mistress of Justice was published in 1992. It is a mystery and legal thriller and Deaver’s law background came in handy to highlight legal issues. Subsequent to writing stand-alone thrillers, Deaver began to publish trilogy series in 1988. He wrote the Rune Trilogy (1988) and John Pellam series (1992). His successful series, Lincoln Rhyme, was published in 1997. The books in the series immediately climbed The New York Times Bestselling novels’ list. Afraid is a part of the short story compilation “More Twisted” which was published in 2006.

“My first and foremost goal is to keep readers turning the pages. Mickey Spillane said that people don't read books to get to the middle; they read to get to the end. And I've tried to embrace that philosophy in my writing,” said Jeffrey Deaver in an interview.

Jeffrey Deaver has famously thrilled and chilled fans with tales of masterful villains and the brilliant minds who bring them to justice. His style in writing allows us to feel the thrill of reading suspense short stories like Afraid. He is able to creatively write the plot and characters, and we shall be analyzing them in the next few paragraphs.

One of the main characters in the story is Antonio. Based on the author's description, Antonio is a handsome man. He is an even figure, with thick, dark hair, brown eyes, and a ready smile. He is a native Florentine and works in the computer field. However, readers will feel a sense of mystery in this man, and his identity is not as simple as he said.

Antonio and Marissa met in a gallery, and the two had a good impression of each other. Marissa shared a lot about her unhappy past experiences in life. Seeing the hopelessness in the woman's eyes, Antonio made up his mind to create a terrifying "plot" for Marissa. On their way to Antonio's house for their weekend together, Antonio stopped the car at the curb of a run-down neighborhood, and that was where his plan started to take place. An old woman who introduced herself as Olga told Marissa that she resembled Lucia who died last year and she also seemed to recognize Antonio's car. After arriving at the destination, in Antonio's old mill, Antonio retold the story of a boy who drowned. This later made Marissa suspicious because Antonio said no one knows exactly what happened. Next, she saw his wedding photos with Lucia in the basement, and then Antonio portrayed himself as a murderous murderer. All of these happenings made Marissa terrified. How Jeffery Deaver characterizes Antonio will make readers feel the suspense of the story. The mood changes, and just like Marissa, readers may also feel unsafe and unsure of the situation. Readers might feel afraid that Antonio will do something crazy or hurt Marissa. As every word coming out from both mouths intensified and pushed through the climax, it builds fear toward readers.

The story continued with Marissa feeling helpless. Fear surrounded her like a long-lasting mist. She can only run away madly. As Marissa was about to escape from this place, the secret was gradually solved. Antonio confessed his identity; he is an artist whose medium is fear. He creates stories that will make people feel afraid. At the end of the story, he allowed Marissa to choose from the three phone numbers. One was the number to take her to the train station, the other was the local police station’s number, and the last was Antonio's number. He left after leaving the choice to Marissa. Antonio leaving Marissa and giving her some space and time to choose from the three phone numbers which might also get him in trouble allows readers to see the good side of this man. By leaving the place, Antonio was able to assure Marissa that he's nowhere near her and that she's safe. This act will make readers realize that Antonio cares about Marissa's well-being. When he wrote in the note that don't she think that being so afraid has made her feel exquisitely alive and that he singled her out to help her, it might make readers wonder if Antonio also has feelings for Marissa. Even if Marissa has a high chance of hating him, Antonio still chose to carry out the plan until the end. His bravery and other distinct characteristics makes Antonio's character so great yet so complex. These characteristics might also lead readers to think that Antonio and author Jeffery Deaver have some things in common.

Marissa Carrefiglio is another one of the two main characters in the story. She is a beautiful blonde woman who manages her family's business's arts and antiques operation. It was also mentioned that she fancies fashion a lot, being a runway model as her job when she was younger. Reading further, we could see how much she disliked her current job. However, without a choice to refuse her stern father's words, she is stuck with that job, being obedient at this point. This scene will make readers think about how society was back when women were meant to obey a man's order and remain silent. It will also make readers ponder if there are still cases like those of Marissa's until now.

"Nice work but there's an obvious problem with it," whispered a handsome man as Marissa responded with a frown, "Problem?" "Yes. The most beautiful angel has escaped from the scene and landed on the floor beside me," replied the man as he turned to her and smiled. This scene was where Marissa and Antonio first met. It seemed like she felt slightly bothered when the man first mentioned a problem with the tapestry. However, as their conversation continued, her slight bitterness slowly faded away, replacing it with a little bit of sweetness instead. The man somehow flirted in this scene, and here, we could see how she may act if someone were to have a problem with something, yet how fast her mood can change if the person were to figure out how. As Antonio listened about how melancholic Marissa’s life was, he starts to plot a “horrific act” to excite the young woman and help her escape from her own unhappy experiences. Marissa’s situation could be relatable to the experiences of others who have lived through a life filled with miserable experiences. And perhaps the readers might be able to imagine Marissa’s experiences happening to themselves, feeling the unhappiness in their kopfkinos or rather a scenario that would be playing in their minds.

In the following scene, when Antonio stopped the car at the curb of a run-down neighborhood, left and took the car keys with him, it made Marissa feel trapped. The woman then spotted two twin boys staring by the sidewalk, which made her feel uncomfortable. As soon as Marissa shifted her gaze away from the twin boys, she was shocked to see an old woman staring at her. The old woman’s name is Olga. Olga asked Marissa if she has a sister named Lucia because she resembles her, Marissa politely denied. As the old woman was about to leave, Marissa asked her about who this Lucia is, showing a bit of her curious side at this point. In this scenario, readers may become curious like Marissa. The mystery of Lucia’s identity will make them intrigued and keep on reading to have their questions answered. When Marissa questioned the old woman about how she knew Lucia, Olga didn’t answer, instead she left quickly after apologizing. Antonio returned with a small, grey paper bag after Olga left momentarily. At this point, the continuation of this scene will make readers even more curious about who Lucia truly is. How Jeffery Deaver wrote the start of the suspense in this story could make the readers start thinking about what will happen next. As Antonio and Marissa continued their long drive, her curiosity rose up more. And when Antonio told her about the death of a young boy at a fast-moving stream near their destination, the suspense started to build up.

Skipping to the part where she and Antonio have arrived at their destination, she suspects nothing at first. Later, Antonio asked Marissa to light up the candles that were beside the bed. She went to grab some matches in the kitchen and noticed that the wine cellar door was left unclosed. Marissa found it a bit odd to see that the inside were organized and spotless, unlike what he had told her earlier: “messy”. She went inside and paused when she saw a half-deflated soccer ball under the nearby table. Marissa remembered what Antonio had told her about the boy’s death, questioning how he knew it took half an hour for the lad to drown. She felt fear at this point, falling for the act Antonio had set up for her. This scene may give readers chills down the spine, given that Antonio had set up a horror act on Marissa. Like he said, it felt great to feel alive once again. Here, the readers might feel the fear Marissa was feeling, having goosebumps on their skins and the thoughts of what will be happening in the following scenes.

The hair-raising plot twist Jeffery Deaver wrote has indeed delivered the suspense and horror he wanted the readers to feel. From the details of the scene to the words of the main characters, the horror he wanted to execute was a success. Without the brilliant illustration of Jeffrey Deaver’s characters, readers would miss much of the thrill of the story. Many people are feeling unhappy and hopeless; they do not feel “alive”. But Antonio, who is into horror and suspense stories, was able to help and give hope to Marissa’s unhappy life. We have our own skill and talent and this story encourages us to try and help others in our own little ways. Most of the time when we hear the word “afraid”, the first thing that comes to our mind is a negative thing. But this story shows readers the good side of it. Through this short story, Jeffery Deaver makes us ponder how being so afraid can make us feel alive, and how being so afraid can make us be more vigilant and aware of our surroundings.

0 notes

Text

Are you Alive?

A Literary Analysis of Jeffery Deaver’s “Afraid”

Some authors struggle to provide readers the most thrilling roller coaster ride of a suspense narrative; nevertheless, thriller writer Jeffery Deaver can build psychologically complex characters, both heroes and antagonists. “Afraid” -- his original short story mainly revolves around Marissa and Antonio. Marissa is a beautiful woman with features of the north. She had been a runway model and afterward took up fashion design which she loves. However, she is forced to take over their family business -- managing the arts and antiques operation. Antonio, on the other hand, is a man full of mystery. They first met at a gallery on the Via Maggio, where Marissa’s company occasionally consigned arts and antiques, and there they found common ground with each other. Antonio took Marissa to his house in Florence. However, the journey from Florence’s Piazza della Stazione to Antonio’s house, an ancient, two-story stone mill with small windows barred with metal rods, made Marissa uneasy. Along the way, she encountered strange events. She obtained information from a strange old woman who gave her clues on what had happened to Antonio’s “wife” -- Lucia. The story went on with Marissa and Antonio arriving at the place and with Antonio retelling a boy who drowned. Marissa later realized that Antonio was a murderer who had killed his wife and the boy based on what she saw in the basement. When she was about to fall into despair, she saw the letter Antonio left her and found out that all of this was an elaborate horror script designed by Antonio. There have been many turning points in this story. The author titled the short story "Afraid" to allow readers to think about its connection to the content. How does this title relate to the following story? Does this title relate to the main character? Then we bring these questions to Jeffery Deaver’s story.

Jeffery Deaver is an international number-one bestselling author who writes American contemporary crime/mystery fiction. He has written prolifically and published more than forty novels, a non-fiction law book and three collections of short stories. His novels have appeared on bestseller lists around the world. His books are sold in 150 countries and translated into twenty-five languages. He is also a lyricist of a country-western album, and he’s received dozens of awards. Born on May 6, 1950, Jeffery Deaver grew up in Glen Ellyn, Illinois. He studied journalism from the University of Missouri and later earned a degree in law from Fordham University. He began his professional career as a journalist then he practiced as an attorney. These career opportunities provided him with ample knowledge to embark on his writing career. His debut stand-alone novel Mistress of Justice was published in 1992. It is a mystery and legal thriller and Deaver’s law background came in handy to highlight legal issues. Subsequent to writing stand-alone thrillers, Deaver began to publish trilogy series in 1988. He wrote the Rune Trilogy (1988) and John Pellam series (1992). His successful series, Lincoln Rhyme, was published in 1997. The books in the series immediately climbed The New York Times Bestselling novels’ list. Afraid is a part of the short story compilation “More Twisted” which was published in 2006.

“My first and foremost goal is to keep readers turning the pages. Mickey Spillane said that people don't read books to get to the middle; they read to get to the end. And I've tried to embrace that philosophy in my writing,” said Jeffrey Deaver in an interview. Jeffrey Deaver has famously thrilled and chilled fans with tales of masterful villains and the brilliant minds who bring them to justice. His style in writing allows us to feel the thrill of reading suspense short stories like Afraid. He is able to creatively write the plot and characters, and we shall be analyzing them in the next few paragraphs.

One of the main characters in the story is Antonio. Based on the author's description, Antonio is a handsome man. He is an even figure, with thick, dark hair, brown eyes, and a ready smile. He is a native Florentine and works in the computer field. However, readers will feel a sense of mystery in this man, and his identity is not as simple as he said.

Antonio and Marissa met in a gallery, and the two had a good impression of each other. Marissa shared a lot about her unhappy past experiences in life. Seeing the hopelessness in the woman's eyes, Antonio made up his mind to create a terrifying "plot" for Marissa. On their way to Antonio's house for their weekend together, Antonio stopped the car at the curb of a run-down neighborhood, and that was where his plan started to take place. An old woman who introduced herself as Olga told Marissa that she resembled Lucia who died last year and she also seemed to recognize Antonio's car. After arriving at the destination, in Antonio's old mill, Antonio retold the story of a boy who drowned. This later made Marissa suspicious because Antonio said no one knows exactly what happened. Next, she saw his wedding photos with Lucia in the basement, and then Antonio portrayed himself as a murderous murderer. All of these happenings made Marissa terrified. How Jeffery Deaver characterizes Antonio will make readers feel the suspense of the story. The mood changes, and just like Marissa, readers may also feel unsafe and unsure of the situation. Readers might feel afraid that Antonio will do something crazy or hurt Marissa. As every word coming out from both mouths intensified and pushed through the climax, it builds fear toward readers.

The story continued with Marissa feeling helpless. Fear surrounded her like a long-lasting mist. She can only run away madly. As Marissa was about to escape from this place, the secret was gradually solved. Antonio confessed his identity; he is an artist whose medium is fear. He creates stories that will make people feel afraid. At the end of the story, he allowed Marissa to choose from the three phone numbers. One was the number to take her to the train station, the other was the local police station’s number, and the last was Antonio's number. He left after leaving the choice to Marissa. Antonio leaving Marissa and giving her some space and time to choose from the three phone numbers which might also get him in trouble allows readers to see the good side of this man. By leaving the place, Antonio was able to assure Marissa that he's nowhere near her and that she's safe. This act will make readers realize that Antonio cares about Marissa's well-being. When he wrote in the note that don't she think that being so afraid has made her feel exquisitely alive and that he singled her out to help her, it might make readers wonder if Antonio also has feelings for Marissa. Even if Marissa has a high chance of hating him, Antonio still chose to carry out the plan until the end. His bravery and other distinct characteristics makes Antonio's character so great yet so complex. These characteristics might also lead readers to think that Antonio and author Jeffery Deaver have some things in common.

Marissa Carrefiglio is another one of the two main characters in the story. She is a beautiful blonde woman who manages her family's business's arts and antiques operation. It was also mentioned that she fancies fashion a lot, being a runway model as her job when she was younger. Reading further, we could see how much she disliked her current job. However, without a choice to refuse her stern father's words, she is stuck with that job, being obedient at this point. This scene will make readers think about how society was back when women were meant to obey a man's order and remain silent. It will also make readers ponder if there are still cases like those of Marissa's until now.

"Nice work but there's an obvious problem with it," whispered a handsome man as Marissa responded with a frown, "Problem?" "Yes. The most beautiful angel has escaped from the scene and landed on the floor beside me," replied the man as he turned to her and smiled. This scene was where Marissa and Antonio first met. It seemed like she felt slightly bothered when the man first mentioned a problem with the tapestry. However, as their conversation continued, her slight bitterness slowly faded away, replacing it with a little bit of sweetness instead. The man somehow flirted in this scene, and here, we could see how she may act if someone were to have a problem with something, yet how fast her mood can change if the person were to figure out how. As Antonio listened about how melancholic Marissa’s life was, he starts to plot a “horrific act” to excite the young woman and help her escape from her own unhappy experiences. Marissa’s situation could be relatable to the experiences of others who have lived through a life filled with miserable experiences. And perhaps the readers might be able to imagine Marissa’s experiences happening to themselves, feeling the unhappiness in their kopfkinos or rather a scenario that would be playing in their minds.

In the following scene, when Antonio stopped the car at the curb of a run-down neighborhood, left and took the car keys with him, it made Marissa feel trapped. The woman then spotted two twin boys staring by the sidewalk, which made her feel uncomfortable. As soon as Marissa shifted her gaze away from the twin boys, she was shocked to see an old woman staring at her. The old woman’s name is Olga. Olga asked Marissa if she has a sister named Lucia because she resembles her, Marissa politely denied. As the old woman was about to leave, Marissa asked her about who this Lucia is, showing a bit of her curious side at this point. In this scenario, readers may become curious like Marissa. The mystery of Lucia’s identity will make them intrigued and keep on reading to have their questions answered. When Marissa questioned the old woman about how she knew Lucia, Olga didn’t answer, instead she left quickly after apologizing. Antonio returned with a small, grey paper bag after Olga left momentarily. At this point, the continuation of this scene will make readers even more curious about who Lucia truly is. How Jeffery Deaver wrote the start of the suspense in this story could make the readers start thinking about what will happen next. As Antonio and Marissa continued their long drive, her curiosity rose up more. And when Antonio told her about the death of a young boy at a fast-moving stream near their destination, the suspense started to build up.

Skipping to the part where she and Antonio have arrived at their destination, she suspects nothing at first. Later, Antonio asked Marissa to light up the candles that were beside the bed. She went to grab some matches in the kitchen and noticed that the wine cellar door was left unclosed. Marissa found it a bit odd to see that the inside were organized and spotless, unlike what he had told her earlier: “messy”. She went inside and paused when she saw a half-deflated soccer ball under the nearby table. Marissa remembered what Antonio had told her about the boy’s death, questioning how he knew it took half an hour for the lad to drown. She felt fear at this point, falling for the act Antonio had set up for her. This scene may give readers chills down the spine, given that Antonio had set up a horror act on Marissa. Like he said, it felt great to feel alive once again. Here, the readers might feel the fear Marissa was feeling, having goosebumps on their skins and the thoughts of what will be happening in the following scenes.