#bret devereaux debate blog

Text

An Extremely Tepid Defense of Luigi Cadorna

Italy’s military Chief of Staff during World War One, Luigi Cadorna, has a deserved reputation for being one of the worst commanders of the war. Bret Devereaux has a really good breakdown of all the reasons why - to summarize, if you ever find yourself fighting the 11th Battle of the Isonzo, presumably because the first ten failed, maybe you should rethink your strategy of constantly attacking mountains. Cadorna was antiquated, stubborn fool who treated his soldiers like cattle to boot.

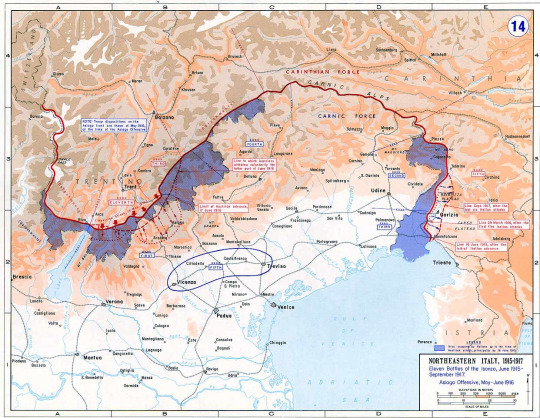

....But there is in fact a logic to his failure that I think goes underappreciated, in that Italy was in a truly *awful* strategic position in World War One. Here is a map of the Italian Front:

Ignore the battle lines, and instead focus on the terrain. The *entire* Hapsburg front for dozens of miles is mountainous, defensible terrain. There is no chance of breakthrough, no real chance of advance, just a point-by-point grind. However, this isn’t true for the Italians; once you bypass a few miles of mountains, or none at all near the east around Trieste, you are into the open fields of the Po river valley. And additionally this is very valuable land; Italy’s north is its most industrialized sector, with its economy centered around Milan just to the west of this map.

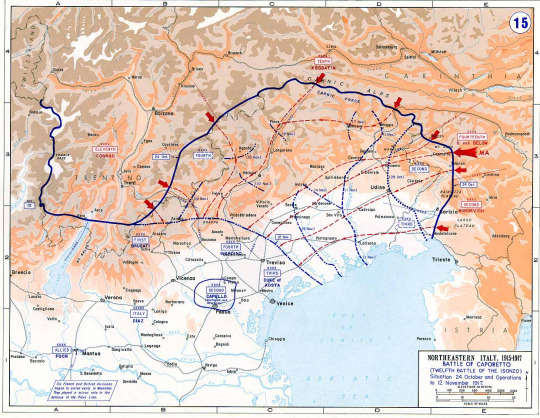

All of this terrain creates an offensive asymmetry; an Italian offensive must be sustained and will move by inches, but one Austrian offensive could achieve a breakthrough, the holy grail of military operations, and occupy valuable land - which actually happened in 1917, at the Battle of Caporetto:

Finally add to this picture the fact that Italy had one of the worst mobilization infrastructures of the war, particularly in the all-important category of rail, and as such their ability to deploy forces in *response* to enemy movements is going to be difficult.

When criticizing a military strategy, you must always answer the question “what else should have been done?” When it comes to Italy in World War One, the most common suggestion for Italy is to simply fight on another front. Send the forces to France, send them to the Middle East, operate as a supporting infantry for armies with greater offensive capabilities on better terrain. Deploy less men on this front, and be productive elsewhere. Here though is where that cursed asymmetry comes into play; it is *very* risky for Italy to deploy forces away from the Austrian front. They may only need one victory, and they can deploy forces to the front faster than Italy can. Austria can keep half the numbers Italy has for months, but if Italy draws down the numbers to match then one surprise offensive later and Venice is being shelled by artillery. Italy has to constantly keep *more* men than Austria on this front, always, to mitigate this potentiality.

So okay, Italy can’t deploy half its army to France, their forces are stuck in the Po River valley. That doesn’t mean Italy has to throw them at mountain strongholds to die by the hundreds of thousands! I mean, I agree, it doesn’t, but here is where geopolitics rears its head. Italy wasn’t attacked by the central powers; it entered the war to gain territory, specifically Austrian territory, upon victory. A victory Italy knows it can’t achieve on its own, but instead must ride on the backs of England & France. Which means Italy’s strategy is, in some ways, at the mercy of those allies.

And how do you think a strategy of “deploy our men to the Austrian border and do nothing” looks to those allies? Looks like freeloading! Austria would *love* that, due to that damned asymmetry it means it can deploy a lot of its forces away from the quiet border to more important fronts like Russia. If Italy wants to be useful, wants to ‘contribute to the war effort’, it has to attack, to make sure Austria is bleeding at least somewhat. Which the Allies understood - there was constant pressure by the Allies on Italy to do ‘something’, and 11 battles on the Isonzo was Italy’s answer to that demand. If it wanted the territories it claimed it did, it had to show its value.

Its the combination of strategic complications and political goals that tied the hands of Cadorna & the Italian military. They had no real offensive options, but had an offensive necessity, and so the worst answer emerged. None of this is a pass; Cadorna was also an awful operational commander, and there is no escaping that Italy bled its own military enough in these attacks to make them vulnerable to precisely the asymmetric breakthrough that occurred. If I was commander of Italian forces I would have bit the bullet, deployed Italian forces elsewhere to contribute, and prepared best I could defensively on the terrain, possibly building a fallback line around say Treviso where the lines are shorter and logistically better supported to make my real defense in case of a large assault. Yet such a strategy prioritizes the larger war effort over Italy’s own terrain; smart strategically, but tough politically.

So in conclusion, Cadorna was a moron, but not quite the moron one might think when you first learn about the grind on the Isonzo. There was a lot of pressure to grind.

137 notes

·

View notes

Text

“...Today, most – though by no means all – free countries (along with a number of rather unfree ones) have shifted from mass conscription based militaries to professional, all-volunteer militaries. The United States, of course, made that shift in 1973 (along lines proposed by the 1969 Gates Commission). The shift to a professional military has always been understood to have involved risks – the classic(al) example of those risks being the Roman one: the creation of a semi-professional Roman army misaligned the interests of the volunteer soldiers with the voting citizens, resulting in the end (though a complicated process) in the collapse of the Republic and the formation of the Empire in what might well be termed a shift to ‘military rule’ as the chief commander of the republic (first Julius Caesar, then Octavian) seized power from the apparatus of civilian government (the senate and citizen assemblies).

It is in that context that ‘warrior’ – despite its recent, frustrating use by the United States Army – is an unfortunate way for soldiers (regardless of branch or country) to think of themselves. Encouraging soldiers to see themselves as ‘warriors’ means encouraging them to see their role as combatants as the foundational core of their identity. A Mongol warrior was a warrior because as an adult male Mongol, being a warrior was central to his gender-identity and place in society (the Mongols being a society, as common with Steppe nomads, where all adult males were warriors); such a Mongol remained a warrior for his whole adult life.

Likewise, a medieval knight – who I’d class as a warrior (remember, the distinction is on identity more than unit fighting) – had warrior as a core part of their identity. It is striking that, apart from taking religious orders to become a monk (and thus shift to an equally totalizing vocation), knights – especially as we progress through the High Middle Ages as the knighthood becomes a more rigid and recognized institution – do not generally seem to retire. They do not lay down their arms and become civilians (and just one look at the attitude of knightly writers towards civilians quickly answers the question as to why). Being a warrior was the foundation of their identity and so could not be disposed of. We could do the same exercise with any number of ‘warrior classes’ within various societies. Those individuals were, in effect born warriors and they would die warriors. In societies with meaningful degrees of labor specialization, to be a warrior was to be, permanently, a class apart.

Creating such a class apart (especially one with lots of weapons) presents a tremendous danger to civilian government and consequently to a free society (though it is also a danger to civilian government in an unfree society). As the interests of this ‘warrior class’ diverge from the interests of the rest of society, even with the best of intentions the tendency is going to be for the warriors to seek to preserve their interests and status with the tools they have, which is to say all of the weapons (what in technical terms we’d call a ‘failure of civil-military relations,’ civ-mil being the term for the relationship between civil society and its military).

The end result of that process is generally the replacement of civilian self-government with ‘warrior rule.’ In pre-modern societies, such ‘warrior rule’ took the form of governments composed of military aristocrats (often with the chiefest military aristocrat, the king, at the pinnacle of the system); the modern variant, rule by officer corps (often with a general as the king-in-all-but-name) is of course quite common. Because of that concern, it is generally well understood that keeping the cultural gap between the civilian and military worlds as small as possible is important to a free society.

Instead, what a modern free society wants are effectively civilians, who put on the soldier’s uniform for a few years, acquire the soldier’s skills and arts, and then when their time is done take that uniform off and rejoin civil society as seamlessly as possible (the phrase ‘citizen-soldier’ is often used represent this ideal). It is clear that, at least for the United States, the current realization of this is less than ideal. The endless pressure to ‘re-up‘ (or for folks to be stop-lossed) hardly help.

But encouraging soldiers (or people in everyday civilian life; we’ll come back to that in the last post in this series) to identify as warriors – individual, self-motivated combatants whose entire identity is bound up in the practice of war – does real harm to the actual goal of keeping the cultural divide between soldiers and civilians as small as possible. Observers both within the military and without have been shouting the alarm on this point for some time now, but the heroic allure of the warrior remains strong.

...But as I noted above, we’ve discussed on this blog already a lot of different military social structures (mounted aristocrats in France and Arabia, the theme and fyrd systems, the Spartans themselves, and so on). And they are very different and produce armies – because societies cannot help but replicate their own peacetime social order on the battlefield – that are organized differently, value different things and as a consequence fight differently. But focusing on (fictitious) ‘universal warriors’ also obscures another complex set of relationships to war and warfare: all of the civilians.

When we talk about the impact of war on civilians, the mind quite naturally turns to the civilian victims of war – sacked cities, enslaved captives, murdered non-combatants – and of course their experience is part of war too. But even in a war somehow fought entirely in an empty field between two communities (which, to be clear, no actual war even slightly resembles this ‘Platonic’ ideal war; there is a tendency to romanticize certain periods of military history, particularly European military history, this way, but it wasn’t so), it would still shape the lives of all of the non-combatants in that society (this is the key insight of the ‘war and society’ school of military history).

To take just my own specialty, warfare in the Middle Roman Republic wasn’t simply a matter for the soldiery, even when the wars were fought outside of Italy (which they weren’t always kept outside!). The demand for conscripts to fill the legions bent and molded Roman family patterns, influencing marriage and child-bearing patterns for both men and women. With so many of the males of society processed through the military, the values of the army became the values of society not only for the men but also for women as well. Women in these societies did not consider themselves uninterested bystanders in these conflicts: by and large they had a side and were on that side, supporting the war effort by whatever means.

And even in late-third and early-second century (BC) Rome, with its absolutely vast military deployments, the majority of men (and all of the women) were still on the ‘homefront’ at any given time, farming the food, paying the taxes, making the armor and weapons and generally doing the tasks that allowed the war machine to function, often in situations of considerable hardship. And in the end – though the exact mechanisms remain the subject of debate – it is clear that the results of Rome’s victory induced significant economic instability, which was also a part of the experience of war.

In short, warriors were not the only people who mattered in war. The wartime social role of a warrior was not only different from that of a soldier, it was different than that of the working peasant forced to pay heavy taxes, or to provide Corvée labor to the army. It was different from the woman whose husband went off to war, or whose son did, or who had to keep up her farm and pay the taxes while they did so. It was different for the aristocrat than for the peasant, for the artisan than for the farmer. Different for the child than for the adult.

And yet for a complex society (one with significant specialization of labor) to wage war efficiently, all of these roles were necessary. To focus on only the warrior (or the soldier) as the sole interesting relationship in warfare is to erase the indispensable contributions made by all of these folks, without which the combatant could not combat.

It would be worse yet, of course, to suggest that the role of the warrior is somehow morally superior to these other roles (something Pressfield does explicitly, I might add, comparing ‘decadent’ modern society to supposedly superior ‘warrior societies’ in his opening videos). To do so with reference to our modern professional militaries is to invite disastrous civil-military failure. To suggest, more deeply, that everyone ought to be in some sense a ‘warrior’ in their own occupation sounds better, but – as we’ll see in the last essay of this series – leads to equally dark places.

A modern, free society has no need for warriors; the warrior is almost wholly inimical to a free society if that society has a significant degree of labor specialization (and thus full-time civilian specialists). It needs citizens, some of whom must be, at any time, soldiers but who must never stop being citizens both when in uniform and afterwards.”

- Bret Devereaux, “The Universal Warrior, Part I: Soldiers, Warriors, and…”

8 notes

·

View notes