#but i’m pretty impressed with the persepctive-ish

Text

This entire chase/rescue scene was amazing and has been replaying in my head forever actually

#Yes there are things i want to fix with this#like the shading and the poses#but i’m pretty impressed with the persepctive-ish#ALSO the movie is in black in white in canon i think but i forgot#anywaysss#aajfhdjd the more i look at this the more i hate/love it so i must post it#dndads#dndads s3#francis farnsworth#the peachyville horror#dndads fanart#my art#artists on tumblr

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

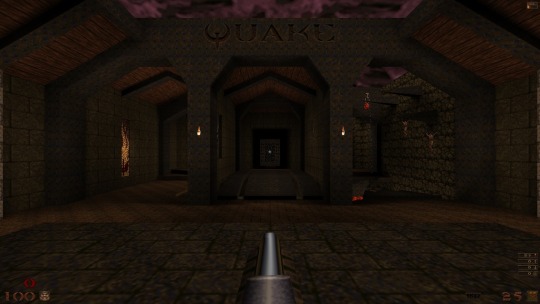

Behind the Gun: A Look at Quake

youtube

It's summer, and in summer I get nostalgic for two things, game-wise: old Playstation games, and Quake.

Back when Quake was still new-ish, we had a Pentium PC (a Compaq Presario Penium 150, to be exact). This was just good enough to run Quake without breaking a sweat... as long as we ran it at 320x240 resolution). A popular online argument at the time was whether Quake or Duke Nukem 3D was the superior game. Considering this article is about Quake, I think we can all safely assume what side of that debate I would have fallen on.

As far as first-person shooters went, I'd played a lot of Wolfenstein 3D on my parents' previous computer (a Packard Bell 386 that originally came with 2 different floppy drives and no sound card, and had the CD-ROM drive and Soundblaster added in a couple years later). And I'd sort of played the classic Doom, albeit only the shareware version, and that running like a slide-show unless we shrank the screen to postage-stamp resolution. But Quake was the first first-person shooter that really hooked me, just got under my skin and grabbed me and kept drawing me back to it again and again. I dreamed about playing it, I think.

For a while there, it was a habit during the summer to play it for hours on end. I'd retreat to my parents' basement (yeah, yeah...) to avoid the summer heat, and clock in time on Quake.

It's the first game I install on a new PC these days: Download from Steam, apply source port patches, and go. There's a lot you can do with it nowadays to make it run at ridiculous resolutions with ludicrously detailed textures on everything, but for my money, I prefer not to do more than apply the anisotropic filter and make the water transparent. It makes it clear exactly what the game is, which is to say a ferocious and fast-paced shooter from a bygone era.

As much as gaming publications of the day painted Quake as the wave of the future, that's because at the time, it looked that way. Hindsight suggests that Quake was less the vanguard of the new school of FPS design and more the beginning of the end of the old school. But the publications of the day were mostly speaking in the strictly technical sense, anyway. Unlike every other FPS then on the market, Quake was the first to be rendered completely in 3D, from the environments to the enemies to the objects in the game world.

From a design persepctive, the one thing this really changed about the usual FPS set-up was an increased element of verticality. Given that most FPSes prior to Quake essentially faked 3D by way of programming sorcery, level design options such as having one room or area atop another, or having platform jumping, were off the table. Aside from these additions, though? From the arsenal of seven or eight weapons available at all times, to the firing of weapons straight out of the ammo reserves (with no magazines or reloading), to the very game-y level design, everything in Quake was familiar to fans of older games.

Which, just to be clear, is the furthest thing in the world from a problem. It takes a measure of getting used to after coming off a Halo bender, but it's old-school design at its finest.

Speaking of old-school design: There's an interesting difference, which you pick up on pretty quickly, between how Quake handles combat compared to other games.

Most enemies in FPS titles these days tend to have behaviors and tactics particular to their type and situation. Sometimes, as in the case of a game like F.E.A.R., the enemy intelligence is capable of surprisingly clever tactics.

Quake isn't one of those cases. Enemies in Quake all basically have the same behavior programmed into them, which is to move toward the player in the straightest line possible, and attack once in range. Which was par for the course with games of this vintage, really. What was smart about the enemies was the way they were arrayed against you, with numbers, placement, combinations, and a level of aggression that kept players on their toes. It means combat frequently occurs against groups of enemies, and occasionally hits a white-knuckled, breathing-heavy level of intensity that gives you a powerful rush when you come out alive on the other side.

There is overall a very game-like feeling to Quake that's hard to shake. This may require some explanation.

More modern video games tend to occur in environments that feature at least a certain degree of realism (for a given value of "realistic"). Say, for instance, your game takes place in a zombie-infested mansion, a la Resident Evil. Modern game design (and Resident Evil is modern in this much, at least) suggests that the architecture should be at least a reasonable approximation of a mansion. The number, size, and layout of rooms and floors should fit a realistic floor plan. Helps with the verisimilitude. An older game, from a time when this was difficult to impossible due to various technical limitations, would have the idea of "zombie-infested mansion" as less a guide to the layout and architecture of the level and more strictly a matter of its visual theme.

Between its inexplicable death-trap levels – whole castles built enirely with only one observable purpose, that being to kill anyone who enters – and its generously placed stashes of ammo and power-ups floating and spinning in midair all video game-y, it's difficult to say that the game is even remotely realistic in either its presentation or its environments.

And yet...

Those environments, thematically speaking, make the game.

Doom (just to contrast for a moment) sold itself by leaning hard into its over-the-top imagery of capital-H Hell. You had fire and brimstone and demons of all descriptions with weapons cybernetically grafted to their limbs; you had pentagrams and skulls and inverted crosses and hearts on altars; you had legions of possessed soldiers; you had skeletons with shoulder-mounted rocket launchers; you had giant floating horned skulls who spat fire at you, and were themselves on fire. And then all of it was amped up to a kind of comic-book excess that ultimately made it kind of hard to take seriously. Not that this stopped it form freaking out the squares, mind you, but said out-freaking only wound up selling more copies of the game. That was Doom: the distillation of a heavy metal album cover. They went for that aesthetic, and they nailed it.

Quake tossed that aside and instead looked toward the sci-fi/horror fiction of H.P. Lovecraft. Like Doom, Quake is fast, fierce, and in your face. But its imagery, its whole aesthetic, is night-and-day from its predecessor. Quake was cold, dispassionate, quiet, unsettling, turgid with implied menace. Where Doom had Soundblaster-quality riffs on hard rock and metal songs for its soundtrack to keep you pumped, Quake gave you Nine Inch Nails. The soundtrack never quite settled into being anything recognizable as music, per se. It's perhaps better described as an ambient soundscape meant to layer a sense of dread and unease over everything. It succeeded at this task, because it turns out that Trent Reznor is the guy you turn to for that.

Aesthetically, this is the difference. Hell makes sense on a certain level, to the extent that any such mythological places and constructs do. Hell cares, after its fashion. It is a place of punishment, filled with beings who declare themselves your enemies, and who set themselves against you. Hell (we are typically informed) is very intimately concerned with your thoughts and deeds; the horror and suffering it inflicts is always personal.

H.P. Lovecraft's mythos suggests a possibility more horrifying: That beings may indeed exist who move the cosmos, but that they do not care. Not only do Lovecraft's monsters not care, they don't notice us in order to care. On the off-chance that they do, it is to casually wipe us out because we are in the way. Lovecraft's thesis, explored in much of his fiction, is that this was the true horror of existence, and that to understand exactly how little we mattered, was to be driven stark, raving mad. His eldritch monsters were mainly symbols designed to express this idea, incomprehensible in order to express the utter incomprehensibility of the universe. The main safeguard of sanity, Lovecraft contended, was human ignorance.

This is the environment in which Quake takes place. And, sure, maybe I'm overselling it a bit. It is, at its core, a game about shooting extradimensional chainsaw-wielding, grenade-throwing ogres with nailguns repeatedly in the face until they die. But these are the trappings that it uses in the service of that goal, and in that sense, they succeed.

In service to this aesthetic, the game features a dark, moody color palette that serves two purposes, I think. One, of course, is to set the mood. The other is to subtly obscure the sharp edges of the game's world.

As the first real fully 3D first-person shooter, Quake's 3D is really rudimentary. As impressive as it was for its day, it hasn't necessarily aged very well. But I suspect that the level designers at Id Software knew this going in, and they did what they could to future-proof it.

The darkness of the game's lighting and its color palette hide some of the sharp edges. For the rest, the game actually leans into is blockiness. The hulking piles of stone which comprise the castles and keeps, dungeons and mazes, the rough-cut caverns in which the game occurs loom and oppress with their size and solidity, their rough and heavy blockiness. The unnatural rigidity of the art design is actually bolstered by the simple polygonal shapes that the engine is capable of producing. It would probably have difficulty creating more naturalistic environments without visibly falling short, as was to some extent demonstrated in Hexen II, made in the same engine by Raven Software. But Id's heavy, menacing, oppressive architecture is a natural fit for the engine's capabilities.

The story, meanwhile, is almost nonexistent, partly as a result of Quake's trouble development.

The game was originally supposed to be an RPG of some variety, with the player being an axe-wielding barbarian (hence the presence of the axe as the player's melee weapon). Somewhere along the way, this changed. I've never heard an explanation as to why. Maybe Id just felt more at home making an FPS. The story I've heard most often about Quake's development is that they didn't really have a story for a long stretch of time, after they'd scrapped the idea of it being an RPG. They just kept creating assets and building levels, because they had to do something. This is part of why the level progression is so arbitrary with little narrative or thematic flow.

Eventually, it occurred to someone that they were getting close to the finish, and no one had really put together a story yet. And while Id Software had never been big on stories in their games, they realized that they had to have something to explain what the player was supposed to be doing, and why. So they wrote a story that was basically Doom all over again. Humankind is experimenting with teleportation technology (only the tech is referred to as Slipgates this time), which draws the attention of an enemy or enemies (extradimensional horrors this time instead of demons from Hell), and said enemy (code-named Quake, hence the title) sends its minions to attack. From there, the player goes on a rampage, tearing a bloody swath through the enemy's forces on the way to capture four runes which, together, will grant access to the enemy's lair. Each rune is hidden in a different dimension, and each dimension is its own episode of the game.

This is a plot that you could fit on one side of a napkin, and when you were done, you'd still have most of the napkin left.

It doesn't matter. Quake is awesome.

Playing is as easy as breathing. Winning is considerably more difficult, of course. But the act of maneuvering through the game's challenges is perhaps the easiest it has ever been in an FPS. For whatever reason, Id decided to remove every extraneous element. You no longer have to press buttons or throw levers; they activate automatically when you collide with them. Doors open on their own as you approach. Your interaction with the game world and everything in it is stripped down to the absolute essentials.

Run. Jump. Shoot. Destroy.

Quake is in a relatively unique category of games for me. I can pursue it as comfort food, but at the same time, it has real substance to it. Thin as its story is, its atmosphere is thick enough to cut. As simple as its gameplay mechanics are, its levels and enemy encounters are designed to test the player's skill. As much as it pays mere lip service to the work and ideas of H.P. Lovecraft, it nails the aesthetic of crushing, oppressive insignificance.

#games#gaming#video games#video gaming#first person shooter#id software#quake#game review#old-school games

0 notes