#but some flavoring. they can pull inspiration from different eras and music and styles

Text

Monthly Reads | November 2020

Happy 28th!

Here are all the fics I read this month and the one I’m (still) currently reading - a whooping 365k fic!

And as always: all my love for all the amazingly talented authors this fandom has ♥

❖ Hang there like fruit, my soul/Till the tree die | louloubaby92 | a/b/o - past sexual abuse - angst - 111k

''You still want me?'' he asks, voice thick.

''Yes,'' Harry's answer is absolute, almost defiant.

''But my hands are empty,'' Louis shakes his head. ''I've got nothing to offer you.''

''I don't care about that. Do you see my hands?'' Harry asks before he cups Louis' face. His touch is gentle. He's always gentle when it comes to Louis. ''When I'm not holding you, I feel empty, but like this,'' he presses closer until their faces are inches apart. He caresses the apple of Louis' cheeks and that's when Louis realizes that he's spilled tears and Harry's wiping them. He didn't even notice; too busy looking into Harry's kind, kind, kind alpha eyes. ''I feel like I'm holding the world and I don't feel empty anymore,''

Louis knows he's a defective omega. He knows its also not his fault but it is what it is. He takes the world head on even when the world is unkind to him. Not Harry though; stubborn as he is, he doesn't back down, not when it comes to Louis.

❖ an island without waves | tofiveohfive | getting back together - angst - post friends with benefits - 5k

Louis feels unreasonable. Less than a month ago, his consciousness was clean, not a hitch in his step. However, since the day the smallest seed of doubt planted itself in his mind, Louis keeps second-guessing himself and his choices. Every time he turns a corner, there’s some variation of Harry’s essence waiting to haunt him. A smell, a sound, a flavor, a color. Something Harry had mindlessly left behind. Something Louis is certain Harry would love if he could show him. Harry is in everything. He’s everywhere.

An AU inspired by Niall Horan's songs: Everywhere | San Francisco | Still

❖ can't believe i captured your heart | millsx | break up - implied/referenced charcater death - domestic fluff - toxic relationship - 22k

Harry wants Louis to teach him how to ride a horse for a date.

Louis wants Harry to break up with said date.

Or, the one where Harry is in a toxic relationship and Louis is there to get him out of it.

❖ Want It Flowing Through My Streams | screwstyles | Tennis AU - a/b/o - strangers to friends to lovers - 30k

Wimbledon ABO AU: Harry has just qualified for his first Grand Slam, and he’s prepared to make the most of it – that is, until his heat unexpectedly hits him only a few days before his first match. And it’s just his luck that Louis Tomlinson, the resident bad boy of British tennis, is the only person around to help him.

❖ pull me back together again (the way you cut me in half) | 28sunflowers | post-break up strangers to lovers to exes to lovers - cheating - angst - 26k

When trying to figure out who the love of his life is, Harry’s brain brings back a specific name from his past.

That’s why, a decade after a messy divorce, Louis opens his door to find his ex-husband standing on the other side, asking for a second chance.

Or a This Is Us AU starring Harry as Kevin and Louis as Sophie, but I selectively choose to use only some parts of what's cannon on the show.

❖ Pride and Peace | BrklynVan | canon compliant - hurt/comfort - fluff - angst - The X Factor era - 4k

Louis stays off of social media and mostly out of the public eye as much as he can. So, when his publicist calls him at 7 AM to tell him that Harry Styles is releasing a Rolling Stone article in which his name appears many times he doesn't know what he is supposed to feel.

“I got an email from Harry Styles’ team today about a piece in Rolling Stone. You are mentioned a few times and Mr. Styles wants your approval.” Louis can feel his heart drop and sudden panic makes his head feel heavy. He is quick to calm himself down and realize it could just be about their time in One Direction.

“Ah, like music-related and shit?” He asks in hopes she will confirm it’s only about One Direction and he can go back to sleep.

“Some parts, yes. I have sent it over to your email. Just to get an idea, It’s a..- its dropping for Pride Month.”

❖ sunflowers, sunshine, and you | soldouthaz | enemies to lovers - slight angst - 28k

Sunshine county is small but mighty and Harry takes pride in knowing nearly each and every person that lives inside of it. For nearly eleven years now he’s been sheriff, and not one of them he’s ever regretted settling down here.

He knows the road names like the back of his hand, knows the people and the animals and the way the world works here. In all of the time he’s been here, not a thing has changed.

So, all things considered, when he starts seeing a beat up pickup truck roaming through town with plates he’s never seen before, Harry, to be frank, jumps on that like a fly on fresh dog shit.

❖ wake the morn and greet the dawn (with hearts entwined and free) | mixedfandomfics | selkies - mysthical - scottish folklore - implied/referenced homophobia - attempted kidnapping - ableist language - 21k

It was a great storm that sent Harry ashore. Grandmothers professed they had not seen its like in a generation, and fathers lost their sons to the sea.

❖ Gimme Some Sugar | nonsensedarling | mutual pining - fluff - humor - no smut - 14k

Louis is scheduled to work an overnight shift with Harry, the hot new pastry chef, to complete a special order. Into the late hours of the night, they bond over music and the ability to make each other laugh like no one else... which makes it harder and harder for Louis to hide his crush. Maybe it won't be so bad if he can't.

*

Or an AU inspired entirely by a manip of Harry with highlights.

❖ Meant To Be (Arse First) | Anonymous | soulmates - soulmate-identifying marks - fluff - meet-cute - bad jokes - humor - 5k

Zayn groans in response, and Louis can hear the slow rustle of his bed sheets in the background. “Is it another ‘you woke up in the back parking lot of a Tesco’s with no pants and I need to come get you before the cops do’ panic or more of a 'I can stay in my bed and lend you an ear’ kind of panic, because I drank a lot more than you did last night, Lou.”

“Uhh,” Louis replies eloquently, “more like an 'I have two giant, blood red handprints on my naked arse, and no, they aren't from a good shag’ kind of panic.”

------

Or the one where your soulmate mark appears on your body where they first touch you and stays there until they touch you for the first time.

Aka the one where Louis's soulmate must like bums.

♦ Hiding Place | alivingfire | friends to lovers - soulmates - soul bond - canon compliant - mutual pining - slow burn - slow build - The X Factor era - 365k

Louis never wanted a soulmate, didn’t really care for the whole Bonding thing at all, really. Enter Harry Styles, who’s wanted to be Bonded for as long as he could remember. With one fateful meeting in an X Factor bathroom, Louis gets a dagger on his arm and the realization that just because Harry is his soulmate doesn’t mean it’s mutual.

From the X Factor house to Madison Square Garden, from the Fountain Studios stage to stadiums across the world, Louis has to learn to love without losing himself completely, because someday his best friend will Bond to someone and replace Louis as the center of his universe. Meanwhile, Harry begins to think that maybe fate doesn’t actually know what it’s doing after all, because his other half has clearly been right in front of him the whole time. All he has to do now is convince Louis to give them a chance.

Or, the canon compliant Harry and Louis love story from the very beginning, where the only difference is that the love between them is literally written on their skin, and there’s only so much they can hide.

69 notes

·

View notes

Note

Why do you leave a comment on every post, but then half of them are like... “writers be inspired” ??

Because I’m an author, I have followers who are fellow writers (and friends who are artists)...and a lot of people have complained to me over the years about where to find inspiration.

Story ideas can come from anything & everything...but only if we open our minds to the possibilities of being inspired by these things.

When asked the question of “Where do you get your story ideas?” it may be personally amusing to me to jokingly reply, “I extract them from the terminus of my alimentary canal, of course!” (Aka the super-fancy way of saying “I pull ‘em outta my butt!”) ...Except it’s not genuinely helpful for those who are trying to figure out where to get their own ideas, their own inspirations.

It doesn’t have to be a grand, vast idea for an entire 100,000-word plot (which is a fairly common/standard size for romance, scifi, and/or fantasy novel lengths). It could be just something that encapsulates the feeling of a scene, a conversation, a brief action, or a visual aid for describing a location or a setting.

If you’re writing a long-form story (which I specialize in), then you’re going to want to have little things that you can sprinkle throughout your story, things that bring richness and depth to the tale you’re telling. Sometimes you’re going to need to send your characters on a side quest (sometimes to fix a plot hole, yeek!), and sometimes you’re going to need your characters to relate some humorous incident.

Having inspirational material on hand, or at least something you’ve looked at in the past, means you can come up with things to fill in the world-building, the scene-setting, the character-describing, the culture-explaining, all these gazillions of little details that most people don’t realize are vital parts of making a story--your story, her story, that story, this story--all the more enjoyable, because it makes a story more immersive.

In my First Salik War series. I included not one but several scenes of the Terrans (and even some V’Dan) eating space food. MREs/field rations that were designed for being eaten in zero gravity or microgravity circumstances.

Did you know that MREs designed for space are overseasoned? It’s because in microgravity/zero gravity conditions, the mucus in our sinuses (which helps with trying to flush viruses & bacteria out of our body)...doesn’t have gravity helping it to move anymore. That means it sits there, building up. And that means our smell-sensing receptors get covered up with natural, normal sinus gunk. That means, in order for food to have any real appeal, it needs to be heavily overseasoned so at least SOME sense of scent & flavor gets through to us!

Except in the series, there are several times where they’re having to eat food packaged for zero gravity while in a normal gravity environment. So I had to make sure that those moments were emphasized as being overly-seasoned. This gave me the chance to do a little scene-enriching, by having my characters have minor little complaints/irritations to deal with. It made those stories more realistic, and all the richer and more immersive for it.

For me, the inspiration for all of that came from my childhood, where we’d go to the Seattle Science Center, and as a treat, my parents would sometimes buy my sister and me Astronaut Ice Cream! Aka, dehydrated ice cream sandwich bars. (I preferred the Astronaut Hashbrowns, but both were a cool treat for young nerdgeek me.)

Of course, this was back in the 1980s (yeah, I’m gettin’ old, oh well), and food rations for astronauts have improved vastly since tubes of protein and carbohydrates and flavors blended into a thick paste. But it’s still my source of inspiration, to look into what MREs are, how they’re preserved, how they’re different for tropical versus temperate versus arctic conditions, and how vastly different those are from what microgravity food has to be like--no crackers or chips unless they’re small enough to fit whole in the mouth without straining, nothing that could cause crumbs that could float around and maybe even cause a short-circuit somehow...

Another source of inspiration might be using images from Assassin’s Creed: Odyssey for when you’re writing a Sword & Sandal story, set in ancient Greece, ancient Rome, etc, etc... We’ve grown up with the assumption that Roman and Greek statues were these pale pristine white things, because dozens of centuries have stripped away the paint...but in reality, they were brightly hued, as were many parts of the buildings of those eras.

AC:O did a great job of showing what the cities would have actually looked like. Just as the Assassin’s Creed series had also done a great job of recreating medieval/renaissance Italian cities, and Paris during the French Revolution, on and on and on...plus a lot of the music from the AC series is great for mood-setting in many ways. Music is, after all, another potential source of inspiration!

And it’s not just writing. Painting, sculpting, pottery-making, composing music, composing poetry, creating dance choreography...! There are so many potential sources for inspiration that it’s breathtaking. Unfortunately--if we’re honest with ourselves--by the time most of us have become adults, we’ve had our spontaneous childhood connections with creativity squeezed out of us by expectations of “proper” cultural and social behavior.

We can get it back, though.

That’s the most encouraging thing I can say to anyone.

You can get your creativity back.

Sometimes it might take a while--for whatever reason--but you can get it back.

It will, however, take exercising. Just like how a couch potato cannot become a marathon studmuffin overnight, you have to first walk a mile, then two miles, then a handful...and then jog for a quarter mile, then jog for a quarter and walk for a half, then...

Like everything, finding inspiration takes practice. It takes awareness. And if you’re going to be a creative content-creator...it takes more than pulling one or two ideas outta yer ass. There is nothing wrong in opening up your mind to all manner of sources for inspiration. Most importantly, however, is to seek out a wide range of inspiration sources...because you’ll never know when something comes in handy.

Some days it’ll be Assassin’s Creed that inspires you in your Greco-Roman style sword & sandal fantasy. Some days it’ll be Conan the Barbarian (the original Schwartzenegger version or the Momoa version). Some days you’ll be so sick of The Bat that you just completely skip any DC comics references at all, not watch any tv shows or movies. And some days you’ll be all over that Bat, drawing up fanfic story ideas for massive crossovers for various incarnations Batman...after being inspired by Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse.

And yes, I said fanfic. Anyone can write that. Good, bad, mediocre, whatever. You can write it, you can find a place online to post it, and you can discover more inspiration for that sort of thing...or just leave it be, move on to something else, and hopefully someone else will find your story and be inspired by it.

Creating stuff doesn’t spring forth from an absolute blank vacuum, after all.

Sometimes we gotta help each other out, and this is my way of doing that.

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

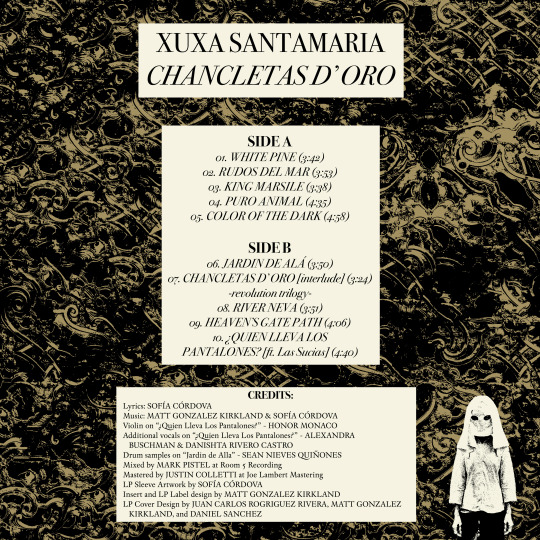

A very special fireside interview with XUXA SANTAMARIA

Check Insta for our thoughts on this landmark album from Oakland duo XUXA SANTAMARIA. Stay right where you are to read a really fun interview I scored with the band this week. They’ve just released Chancletas D’Oro on Ratskin Records out of Oakland and Michael blessed me with my very own copy. It was so good I knew I needed to tell you all about it and I wanted to pick their brains a little bit, too. Without further ado, please enjoy:

//INTERVIEW

You’re still breaking into indie world at large, but you’ve already got a huge following back in California and your home-base in Oakland. What has it been like to be featured in major outlets like The Fader?

SC: We are a funny project; we ebb and flow from being total hermits to having periods of relatively high visibility (relative to aforementioned hermit state). I wouldn’t say we have a huuuge following in CA but I do think that the ‘fandom’ we’ve developed here is really genuine because we don’t play shows out of an obligation to remain visible but instead do so because we feel super passionate about the work and the audience and I think people respond to that energy. I for one, and perhaps this is because of my background in performance, have a hard time performing the same stuff over and over without change which accounts for us being selective with our playing live. That’s also why videos are such an important part of what we’re about. The piece in The Fader was important to the launch of this album because it established some of the themes and, to an extent, the aesthetics of this album in a way that can be experienced outside of a live setting. None of this is to say we don’t like playing live, in fact we love it, we just like to make our sets pleasurable to ourselves and to our audience by constantly reworking it. We strike a weird balance for sure but we’ve made peace with it. If we ever ‘make it’ (lol) it’ll be on these terms.

Chancletas D'Oro is a pretty incredible record and while it reminds me of a few bands here or there, it’s got a really fresh and unique style that merges dance with all sorts of flavors. How would you describe your music to someone who is curious to listen?

MGK: Haha, we generally struggle to describe our music in a short, neat way (not because we make some kind of impossible-to-categorize music, but just because it’s the synthesis of a ton of different influences and it’s hard for US to perceive clearly). But with that caveat in mind - IDK, bilingual art-punk influenced dance/electronic music?

SC: Thank you for saying so, we’re pretty into it :) Like Matt says, we struggle to pin it down which I think is in part to what he says – our particular taste being all over the place, from Drexciya to The Kinks to Hector Lavoe- but I think this slipperiness has a relationship to our concept making and world building. As creative people we make and intake culture like sharks, always moving, never staying in one place too long. Maybe it’s because we’re both so severely ADHD (a boon in this instance tbh) that we don’t sit still in terms of what we consume and I think naturally that results in an output that is similarly traveling. Point is, the instance a set of words - ‘electronic’, ‘dance’, ‘punk’- feel right for the music is the same instance they are not sufficient. I propose something like: the sound of a rainforest on the edge of a city, breathy but bombastic, music made by machines to dance to, pleasurably, while also feeling some of the sensual pathos of late capitalism as seen from the bottom of the hill.

The internet tells me you’ve been making music as Xuxa Santamaria for a decade now. What has the evolution and development of your songwriting been like over those ten years?

MGK: Well, when we first started out as a band we were so new to making electronic music (Sofia’s background was in the art world and mine was in more guitar-based ‘indie rock’ I guess - lots of smoking weed and making 4 track tapes haha), so we legit forgot to put bass parts on like half the songs on our first album LOL. We’ve learned a lot since then! But in seriousness, we’ve definitely gotten better at bouncing ideas back and forth, at putting in a ton of different parts and then pulling stuff back, and the process is really dynamic and entertaining for both of us.

SC: This project started out somewhat unusually: I was in graduate school and beginning what would become a performance practice. I had hit a creative roadblock working with photography - the medium I was in school to develop- and after reading Frank Kogan’s Real Punks Don’t Wear Black felt this urge to make music as a document of experience following Kogan’s excellent essay on how punk and disco served as spatial receptacles for a wealth of experiences not present in the mainstream of the time. I extrapolated from this notion the idea that popular dance genres like Salsa, early Hip Hop, and Latin Freestyle among many others, had served a similar purpose for protagonists of a myriad Caribbean diasporas. These genres in turn served as sonic spaces to record, even if indirectly, the lived experiences of the coming and going from one’s native island to the mainland US wherein new colonial identities are placed upon you. From this I decided to create an alter ego (ChuCha Santamaria, where our band name originally stems from) to narrate a fantastical version of the history of Puerto Rico post 1492 via dance music. We had absolutely no idea what we were doing but I look back on that album (ChuCha Santamaria y Usted - on vinyl from Young Cubs Records) fondly. It’s rough and strange and we’ve come so far from that sound but it’s a key part of our trajectory. Though my songwriting has evolved to move beyond the subjective scope of this first album - I want to be more inclusive of other marginalized spaces- , it was key that we cut our teeth making it. We are proud to be in the grand tradition of making an album with limited resources and no experience :P

We’re a big community of vinyl enthusiasts and record collectors so first and foremost, thanks for making this available on vinyl. What does the vinyl medium mean to you as individuals and/or as a band?

MGK: I think for us, it’s the combination of the following: A. The experience of listening in a more considered way, a side at a time. B. Tons of real estate for graphics and design and details. C. The sound, duh!

SC: In addition to Matt’s list, I would just say that I approach making an album that will exist in record form as though we were honing a talisman. Its objecthood is very important. It contains a lot of possibility and energy meant to zap you the moment you see it/ hold it. I imagine the encounter with it as having a sequence: first, the graphics - given ample space unlike any other musical medium/substrate- begin to tell a story, vaguely at first. Then, the experience of the music being segmented into Side A and Side B dictate a use of time that is impervious to - at the risk of sounding like an oldie - our contemporary habit of hitting ‘shuffle’ or ‘skip’. Sequencing is thus super important to us (this album has very distinct dynamics at play between sides a/b ). We rarely work outside of a concept so while I take no issue with the current mode of music dissemination, that of prioritizing singles, it doesn’t really work for how we write music.

MGK: We definitely both remain in love with the ‘album as art object/cohesive work’ ideal, so I would say definitely - we care a lot about track sequencing, always think in terms of “Side A/Side B” (each one should be a distinct experience), and details like album art/inserts/LP labels etc matter a lot to us.

What records or albums were most important to you growing up? Which ones do you feel influenced your music the most?

SC: I know they’re canceled cus of that one guy but I listened to Ace of Base’s The Sign a lot as a kid and I think that sorta stuff has a way of sticking with you. I always point to the slippery role language plays in them being a Swedish band singing in English being consumed by a not-yet-English speaking Sofía in Puerto Rico in the mid 90s. Other influences from childhood include Garbage, Spice Girls, Brandy + Monica’s The Boy is Mine, Aaliyah, Gloria Trevi, Olga Tañon etc etc. In terms of who influences me now, that’s a moving target but I’d say for this album I thought a lot about the sound and style of Kate Bush, Technotronic, Black Box, Steely Dan, ‘Ray of Light’-era Madonna plus a million things I’m forgetting.

MGK: Idk, probably a mix of 70-80s art rock/punk/postpunk (Stooges, Roxy Music, John Cale, Eno, Kate Bush, Talking Heads, Wire, Buzzcocks, etc etc), disco/post-disco R&B and dance music (Prince, George Clinton, Chic, Kid Creole), 90s pop + R&B + hip hop (Missy & Timbaland, Outkast/Dungeon Family production-wise are obviously awe-inspiring, So So Def comps, Jock Jams comps, Garbage & Hole & Massive Attack & so on), and unloved pop trash of all eras and styles.

Do you have any “white whale” records that you’ve yet to find?

MGK: Ha - the truth is that we’re both much more of a “what weird shit that we’ve never heard of can we find in the bargain bin” type of record buyer than “I have a custom list of $50 plus records on my discogs account that I lust over”.

SC: Not really, I’m wary of collectorship. That sort of ownership might have an appeal in the hunt, once you have it do you really use it, enjoy it? Funnily, I have a massive collection of salsa records that has entries a lot of music nerds would cry over (though they’re far from good condition, the spines were destroyed by my Abuela’s cat, Misita lol, but some are first pressings in small runs). For me its value however, comes from its link to family, as documents from another time and as an amazing capsule of some of the best music out of the Caribbean. I’m glad I am their guardian (a lot of this stuff is hard to find elsewhere, even digitally) but I live with those records, they’re not hidden away in archival sleeves, in fact, I use some of that music in my other work. Other than that, the records I covet are either those of friends or copies of albums that hold significance but which are likely readily available, Kate Bush’s The Dreaming or Love’s Forever Changes, or The Byrds Sweetheart of The Rodeo as random examples

Finally, is there a piece of interesting band trivia you’ve never shared in another interview?

SC: haha, not really? Maybe that we just had a baby together?

//

Congrats on your new baby, and also for this wonderful new album. It was a pleasure chatting with you and I can’t wait to see what the future has in store for you and your music!

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Living With Pink

Since @seasurfacefullofclouds did a lovely review on ‘Harry Styles’ (post) after living with it for more than a year - I felt inspired to write up my own observations and opinions.

For the sake of brevity and the fact that it seems to irritate certain haters - I will refer to Harry’s album as “PINK” throughout.

Melody! There are ten good, fully developed melodies in an era where a four note hook combined with a bass loop is thought to constitute a song. Really, there are more than ten, Sign of the Times has three distinct melodies, seamlessly woven together. (On an intellectual level, I understand that some people don’t think melody is the most important element of music. On a gut level, I just don’t get it. Melody is it for me.) I’ve listened to PINK straight through hundreds of times. The beauty and quality present in every song, nearly every moment never fails to impress. I’ve never really been an album guy, because, even among my favorite artists, at least half of the songs seem there just to take up space. (I used to make mix tapes, back in the day.) With PINK, I feel that every song has real merit and is fully worthy of it’s place. Harry’s voice (which I have always really loved - even X-Factor era) and vocal technique have reached a superlative level. I think Harry is at absolutely peak performance, and it’s a beautiful thing to behold. The instrumentation and arrangements are breathtaking. Even the angry Kiwi has deep beauty and avoids shrill, unpleasant sounds, often found in hard rock. For those who are willing to look below the surface, PINK’s honesty, vulnerability and frankness are noteworthy. I feel that Harry is speaking directly to me and the album is providing a window into his soul - into his humanity. PINK grapples with internal conflicts omnipresent in the human condition, good and evil, love and hate, selfishness and sacrifice. I am very confident that PINK will sound just as good 20, or 30 years from now - it won’t ever become stale, or sound dated. Some wished for a more cohesive album, but for me, the variety makes it really hard to grow bored of PINK. I was infatuated with the album from the start. As time goes on, my love for it only deepens.

This ended up getting pretty long - track by track under the cut.

Meet Me in the Hallway was a bit dreary to me at first. Now I find myself absorbed in it. The aching and longing, the vulnerability, the pain - it all feels so close, honest and real. The repetition of “gotta get better” is slightly irritating to my ear - for that reason, I will occasionally skip the track. I do wonder, however, if that irritation was intentional - meant to provoke some unease in the listener. The guitar part on this song is achingly beautiful, as is Harry’s voice.

Sign of the Times is a masterpiece by any measure. Sea pointed out how difficult it is to sing this song in a way to do it any justice. Precious few artists could pull it off. Every time I hear it, the song transports me - it lifts me out of myself. The rich, full sound and deft combination of three distinct melodies is no small feat. Guitar slides, strings, gospel choirs - it could so easily be overblown, or too grandiose, but it strike the perfect balance. The song moves at a stately sixty beats per minute. I would imagine this is very close to Harry’s resting heart rate. There is nothing rushed - every moment is given it’s full due. Also, I am of the old fashioned belief that art should be beautiful. Every second of SotT is achingly beautiful and I love it.

Carolina is great fun and incredibly clever. May artists try to be “edgy,” or “cool” by referencing drugs. Carolina recreates in music what I imagine it would feel like to be high on coke. (I’ve been around people who were jacked up before.) The manic “la la la la la la la la’s,” the fuzzy sensation, “she feels so good!” If you listen carefully, Harry sings it as if he is in a slight haze - king of nuance, as always. The metaphor is nothing short of brilliant - “get’s into parties without invitation” - “she feels so good.” Layers of sound, particularly on the second verse, are extraordinary. This song gives you the same kind of sugar rush a hit pop song can deliver, but backs it up with plenty of vitamins and protein, so you don’t get that “sugar low” and grow tired of it.

Two Ghosts has some of the most compelling word images - “Fridge light washes this room white,” for one. It’s a deceptively simple, easy to sing song, but a lot of artist would turn out a boring rendition. The album version is lovely, but the performance he did, just Harry and his guitar, was breathtaking. Once again, we have deep vulnerability and profound honesty. I do wish he had done the vocal “ooo’s” on the album version. We’ve all seen how hyper aware Harry is of his surroundings. He stared right at the camera trying to snag a sneaky snap. He spots people, way up in the nosebleed seats, trying to leave early and gently chastises them. He’s too finely tuned of an instrument to handle fireworks easily. I believe he is much more aware of all his senses than the average person. Touch, taste, sight, sound - he sculpts and paints with his music.

Sweet Creature is a song I will often skip back and repeat as once through just isn’t enough. It’s not a sugary, or fairy tale version of love, but honest, vulnerable, real. “Runnin through the garden, oh when nothing bothered us,” paints such a beautiful picture. “Sweet Creature” is such and odd phrase and yet conveys such warmth and deep connection for Louis another person. Harry’s voice brings an incredible warmth to this song - a warmth utterly unique to his quite distinctive voice. Again, it takes great artistry to impart such feeling on a relatively simple song, like this. The guitar part is certainly inspired by the Beatles’ Blackbird, but any similarity ends there, in my opinion. For my ear, Sweet Creature is a better song - it moves me in a way Blackbird never could.

Only Angel sets up a beautiful dichotomy. The angelic, SotT inspired, into and outro envelop the hard rock interior. The contrast intentionally reinforces the song’s story. Harry’s voice doesn’t quite have the anger, or hardness one might expect at on a first listen - the warmth in his voice was very intentional. The angel (which is Harry himself) is also a devil between the sheets. Mother (authority figure) doesn’t approve of how the angel presents “herself.” Harry loves attention and the stage, but hates fame. He’s good and kind, but also has a dirty side. (I could go on and on, but I’ve written on my OA interpretation extensively, ages ago.) A plus for using a flawed angel as a metaphor for himself - brilliant. The melody is catchy as hell - it’s a “bop” and great fun to hear, but there’s so much meat it’s almost ridiculous. The sound is rich and beautiful throughout and I love that he brings back the angelic sound to close it out.

Kiwi has so little movement in the melody, yet it works beautifully - somehow, it’s still a great melody and hard to get out of your head. The instrumentation is angry and hard, yet rich, full and pleasant to the ear. Harry’s voice has just the right amount of anger and derision. “She” is Simon Cowell. She tempts the boys with fame and fortune, but she’s hollow inside. It’s an angry song, but it feels so good, joyful even, to hear it. Harry’s stage performance reveals how cathartic it is to finally tell Simon what he thinks of him - in front of a massive audience. I love Kiwi so much, I’ve made the most raucous chorus into a ringtone on my phone. “Oh I think she said, “I’m having your baby” [heyyyy] “it’s none of your business” [hoooo......] Harry has such a great, raspy rock voice - it really isn’t fair.

Ever Since New York sounds like some combination of Bruce Springsteen and the Statler Brothers. The accompaniment is beautiful and rich with a really great, solid melody. Harry’s vocalization suggests someone who is TIRED and DONE with the situation. “Tell me something, tell me something new. Don’t know nothing, just pretend you do...” is sung as a plea - a plea devoid of any hope of being answered. Harry is vulnerable, broken and through putting up a front, or playing games.

Woman has been compared to Elton John’s Bennie and the Jets a lot - way too much, in my opinion. There are similarities in the structure of the song, but Woman has a completely different sound. I like a lot of John’s music, but when he sings “B-B-B-Bennie” he squeaks like a rusty hinge. Harry sings “W-W-W-Woman” in a different key and melody (and with a deep, pleasant vocal.) “Selfish I know...” It’s one of the best jealousy songs I’ve ever heard. He knows he’s selfish - knows it’s wrong, but can’t help his feelings. I love Harry’s unflinching look at the darker side of human nature and wholly realistic view of his own failings. Woman has a very good melody and those little “la-la la-la la-la la-la’s” give it just the zest in needs.

From the Dining Table might just be too honest. While the artistry was immediately apparent, I was a little slow to warm up to this song, because it’s a bit depressing. He sings about masturbating as a distraction to his pain and loneliness (and some said the album wasn’t honest enough!) This song is pure vulnerability. It’s arranged with such simplicity and great restraint. (Harry understands the beauty of restraint, you can hear it in If I Could Fly.) This is another song which must be sung with great artistry, to prevent it being dull. The addition of strings and lovely female harmonies (”maybe one day you’ll call me...”) is a master stroke. I am perplexed as to why he didn’t have Sarah and Clair sing the harmonies on tour. Beautiful, beautiful song, but it is still a bit depressing - as it was meant to be. Harry loves angst and drama.

Speaking of restraint, Harry has a habit of doing just enough, but never too much (nuance again.) He changes vocal inflection and flavor with ease, but never adds gratuitous vocal embellishment. Harry is quite capable of singing runs and all sorts of vocal gymnastics, but chooses a simple, restrained beauty. (Sometimes, less is more.) He maintains this restrained discipline in the accompaniment, as well. PINK is a rock album, but also so much more.�� In ten, or twenty years it will still sound fresh - and I think more people will realize what a masterpiece it truly is.

24 notes

·

View notes

Photo

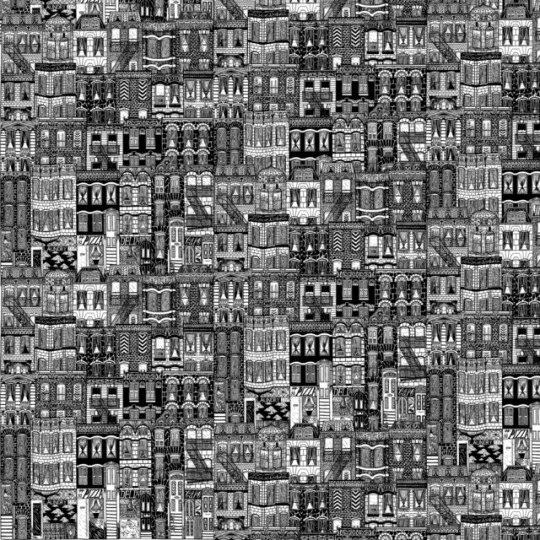

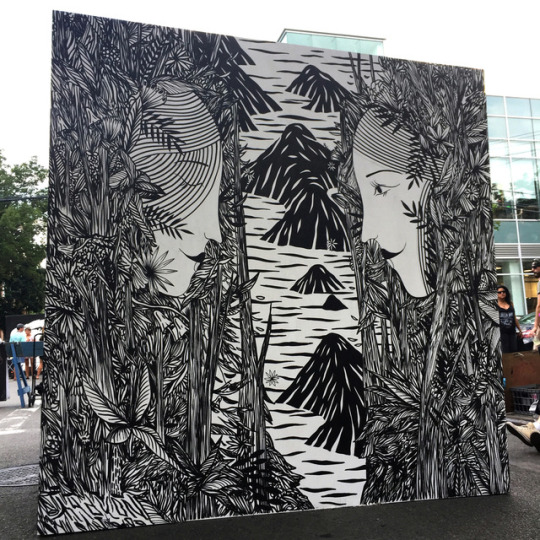

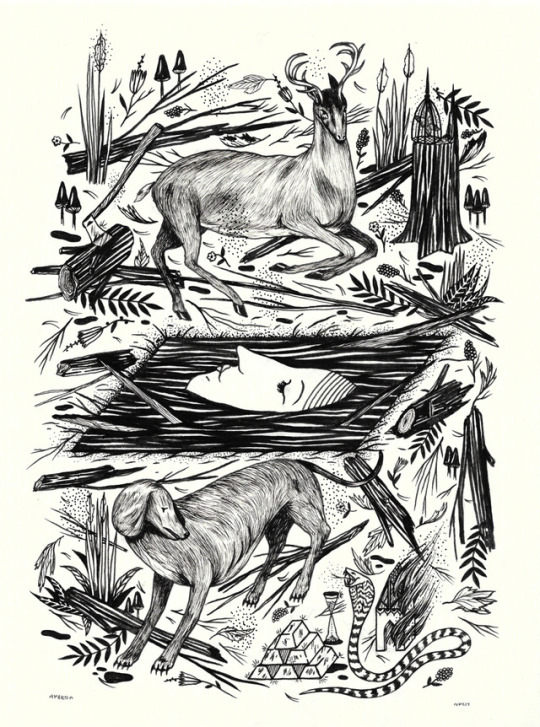

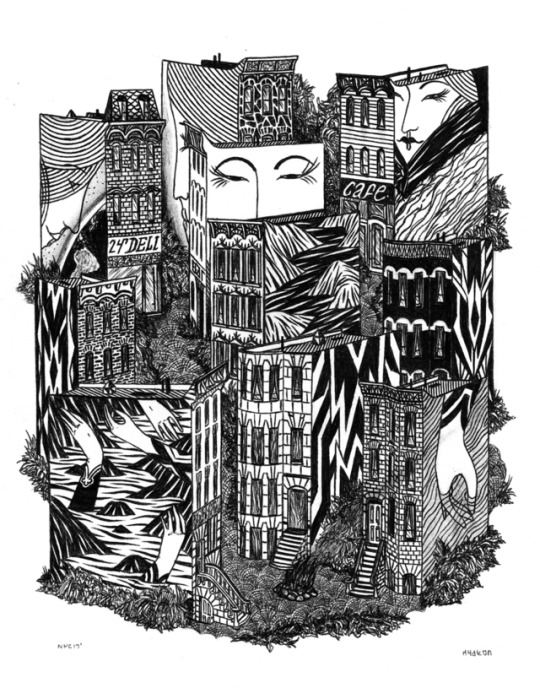

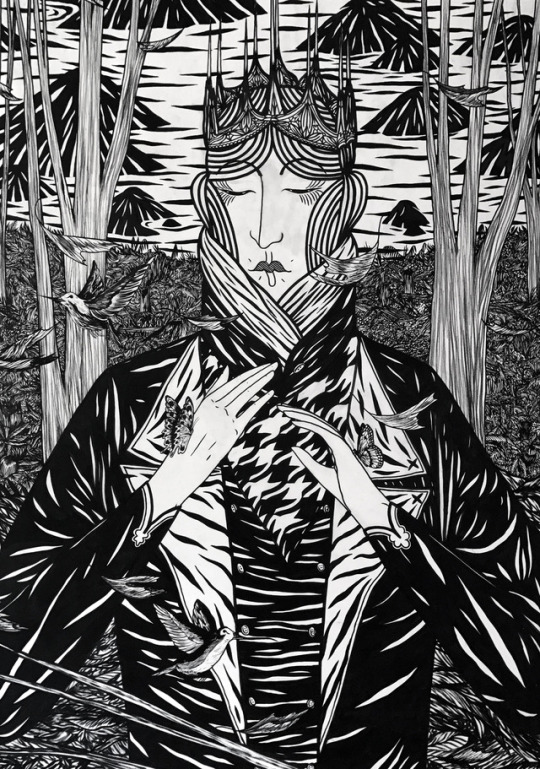

ART SCHOOL | HYDEON (Brooklyn, NY)

Visual artist and designer Ian Fergurson aka HYDEON is known for his simple monochromatic black and white works, often featuring old gothic buildings, Colonial style witches, and eye catching installations and murals. Not only one thing, Ferguson was most recently employed as a silk screen printer an wallpaper company, until his works were purchased by a private collector in the summer of 2017, launching his art career. We’re really excited to chat with Ian about his art journey, his works and processes, as well as a mural he completed on the 69th floor of 4 World Trade Building.

Photographs courtesy of the artist.

Can you tell folks a little about yourself? We’re always curious about artist handles, sometimes there is a good story behind it, just curious what’s the significance of @hydeon?

My name is Ian Ferguson. I’m a visual artist and designer living and working in Brooklyn, NY. I work out of my home studio. I’ve been publishing my work under the name Hydeon for about 15 years now. The name Hydeon is partially derived from the avant-garde animated series Æon Flux which aired on MTV in the 90’s. Eon Flux became a nickname I had in Middle School. My friends at the time would call me Flox or Eon or both. Years later when I was in college studying graphic design In the early-mid 2000’s I wanted to have an alias to sign my work under as a way to create my own unique identity and branding. I used the Eon part from my nickname in middle school and added the Hyd part in front of it. It can be pronounced two different ways, It can be like “Hid-Ian”, or “Hide-Ian”. The idea is that my own name is hidden within the alias.

When did you first get into drawing, and what were you drawn too? How did your early interest evolve into something more?

I grew up in a family of artists in San Diego, CA. I was born in 1985. My mom had me drawing very early before I could hold a pencil on my own. She would hold my hand with the pencil or brush and help me make drawings and paintings. I must have been 2 years old maybe when she started teaching me, I’m not entirely sure. My earliest memory of creative inspiration that really spoke to me was seeing the work of M.C. Escher. I was absolutely obsessed with his work as a child. One of my first ever art exhibits I ever saw was an M.C. Escher exhibit at the San Diego Museum of Art. All throughout my youth I was always making art. I was obsessed with drawing and how it would make me feel. It always seemed to calm me down and I was eventually able to discover a form of meditation through it. I grew up skateboarding as well, wearing Vans, hiking and going to the beach, classic Southern California activities. Through skateboarding my influences in art and music evolved. The drawings and paintings I grew up making would eventually evolve into designing posters for shows. I think thats where I got the initial start into my career. Everything seemed to stem from making the posters. My first ever art show was a group show on skateboard decks in 2003 at King Cassius Gallery in San Diego.

Having attended Art Institute of California, San Diego, what was your experience with art school, and what was your experience after art school as an artist? Did you find the transition difficult, challenging, easy, and/or just totally off the rails?

My experience at AI-SD overall was positive. I met some amazing friends there and that was the best part of it. I studied graphic design so almost everything I did in college involved a computer. Once I figured out the Adobe programs I just wanted to get through school and do my own thing.

My career transition after college was very textured and difficult. I had moved to Seattle in 2006 right after school to explore the mountains, forests, music, and art scene there. I was hoping to land a design job up there with my new degree, but It never really panned out and the school couldn’t really help much with jobs because I was out of state. I ended up working mostly at a thrift store and would just do art and music on the side. After several years in Seattle I had a crazy mental breakdown at the thrift store I was working at and shortly after that I got some help and was diagnosed with bi-polar disorder. I fled back to San Diego for a few months to get some sun and just chill out at home. During that period I worked at an art store in downtown San Diego for about 6 months.

After that I felt a strong magnetic pull to move to Chicago and explore the architecture, art, and music scene there. I figured I would have more opportunity in a bigger city and I knew I wanted to live outside of California. I saved up money at the art store and moved to Chicago. I tried to get a design job there, but It wasn’t working out so I quickly ended up working as a full time cashier at a grocery store. I did that for a while until I completely burned out on the register and they fired me. I was able to get unemployment, so I took advantage of it and hustled my art as hard as a could with the time I had. After that I worked a weird retail shoe stocking job, worked at a fast food chain, and did bike messaging in the loop. I basically took whatever job I could get to support myself on a basic level and then just hustled my art and design stuff as much as possible on the side. I started doing allot of shows and after a while I had built up a little success in Chicago but It wasn’t until I moved to NYC in 2014 that everything really changed and I started having significant success with my work.

Often times artists are not only ONE thing, each juggles art and or is making a real effort to hustle at it? How do you balance art and life? What is your other hustle and how does that factor into what you do?

Good question. As I mentioned in the previous question I had many different types of jobs I would do to support myself so I could do my art. When I moved to NYC in 2014 I landed a job working as a silk screen printer for Flavor Paper, an amazing wallpaper company in collaboration with the Warhol foundation. This was the first real art job I’ve ever got and the best job I have ever had. I worked there for about two and a half years full time making hand silk screen wallpaper and then hustling my art on the side.

It wasn’t until just this past summer of 2017 that I had a career breakthrough with my work. I sold a giant painting to a private collector in Washington D.C. that had discovered me on Instagram. This was the sale that changed everything for me. I was able to quit my job at Flavor Paper and work entirely for myself. I work every single day for myself now. It’s the most gratifying feeling. It feels more than a full time job, it’s a full time commitment and a lifestyle. I’m always working. Aside from doing drawings and paintings for gallery shows I do commission work involving anything from murals to branding design and illustration work. I’ve also been collaborating with Brazilian fashion brand 1994. and an NYC based fashion brand The Very Warm. Flavor Paper has also released my first wallpaper pattern “Brownstoner” which has been a great success.

How would you describe the black-and-white works you create? Amongst the various things you illustrate, buildings and old style victorian structures play a role. How did this come about?

I became fascinated with old world gothic architecture and the victorian era around 2009 when I first left the west coast and visited Chicago and New York for the first time. Seeing the brownstones and old gothic buildings in both cities really impacted me in a significant way. I fell in love with these types of buildings. They have a romantic historical quality to them that makes me feel transported back in time to another world. I feel a deep connection of energy in them and it makes me feel good, its a beautiful feeling. I had never really seen buildings like this before I came out to these cities. I have always done black and white work, but started working exclusively in black and white about a year ago. I felt like I needed a break from color for a while to just focus on the simplicity of monochromatic work. I love the quality of black and white and the versatility of it. You can put a black and white piece in almost any home or environment and it will look good. Black and white doesn’t fight any other colors, its its own thing. I’ve recently been doing color work again and loving it, but will always keep the black and white pieces going.

Do you keep a sketchbook for ideas or do you find yourself just sitting down, hitting the paper off to the races, so to speak?

Sometimes and it’s a little bit of both! I keep a few different sketchbooks of various sizes. I like to go to cafes and parks and chill and sketch out ideas when I have them. I ride my bike everywhere and find allot of inspiration while riding the bike or running. I get allot of inspiration from my environment and life experience so I like to wait for the inspiration to hit me and then act on it with the sketchbook. Often times I use basic computer printer paper to sketch out final ideas before they go to nice paper, canvas, or wood panel.

Who were some of your artistic influences?

Some of my absolute favorite artists and influencers are:

Marcel Dzama, Thomas Campbell, Tim Kinsella, Cleon Peterson, M.C. Escher, Mamma Anderson, Henry Darger, Ed Templeton, Toulouse Lautrec, Andrea Joyce Heimer, Pitseolak, Egon Schiele, Danny Fox, and More..

What are your top 5 art materials to work with?

Faber-Castell PITT artist pens

Ticonderoga HB #2 pencils

Bic Black Ballpoint Pen

Montana Paint markers OR Molotow Paint markers (both are great!)

Golden Acrylics

You recently installed your work at 4 World Trade Center as well as created a mural in the East Village? How did this project come about? What was the best part of the overall experience?

The World Trade Center mural happened through my good friend Joohee Park AKA Stickymonger. We both show at this gallery in the financial district of Manhattan called World Trade Gallery, which is a gallery affiliated with the WTC.

The gallery had access to the 69th floor of 4 World Trade and asked a number of artists to do murals on the floor. Stickymonger was really the catalyst for me getting into the tower. She’s an amazing artist and a very good friend of mine. The experience working in the tower was absolutely amazing and beautiful. There were several nights where I got to work up there entirely alone on the 69th floor. It was just me and my music and jamming away on my mural. The experience was ethereal seeing the whole city glowing from above with 360 degree views. I felt like I was on top of the world and the mural came out fantastic. I did a black and white architectural motif of New York City with the Hudson River as the floor and the Palisades on the other wall.

My mural covered an entire corridor of the Woman’s bathroom. It was one of the only spaces left for a mural and no one wanted it, so I jumped on it! I loved the whole experience and everyone took good care of me throughout the process. I met some amazing people through that project, one of which was curator Joshua B. Geyer who eventually asked me to do the mural in the East Village which was apart of the Centre-Fuge Public Art Project.

What would your dream collaboration be like?

Oh wow! I have allot of ideas for this one, but I would love to do a collaborative drawing with Marcel Dzama sometime.

What are your favorite Vans?

The Sk8-Hi all the way!

What advice would you give someone thinking about art as a career?

Really dive deep within yourself and make sure you love doing it first. Then decide if you’re willing to make the full commitment. Consider it a lifetime investment and learn to trust and believe in yourself against all odds. Be ready and willing to take big risks at any given moment. Always be prepared to take criticism of all sorts, good or bad. Know that a career in art takes allot of time, allot of hard work, and a 100% commitment and belief in yourself. Be willing to network and expose yourself to the art world. Explore as many galleries/museums as possible. Always do your absolute best work, put everything you have into it, experiment, take chances, and never give up. Celebrate every success no matter how big or small and eventually if you work hard enough and you believe in yourself, you will be able to achieve your goals. Anything is possible.

What are you looking forward to the rest of this year and beginning of next?

For the remainder of 2017 I’ll be working on large scale works in color on paper and canvas. I’m going camping soon with my family in Joshua Tree where I hope to discover some fresh insight and inspiration. I’ll be showing new work at Spoke Art NYC in March 2018 for a really amazing group show. I have a few other things lined up but thats about it for now.

Who is an artist you’d like to see on Art School one day?

Lala Abaddon !

Follow Hydeon: Instagram | Vimeo | Website

142 notes

·

View notes

Text

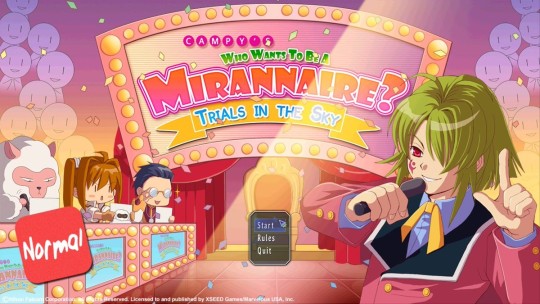

2017 End-of-the-Year Q&A Extravaganza Blog! #1

It’s time for our first 2017 End-of-the-Year Q&A Extravaganza! We’ve got a bunch of these we’ll be posting over the holiday break, so please look forward to them. Now, let’s roll right in!

We have answers from:

Ken Berry, Executive Vice President / Team Leader

John Wheeler, Assistant Localization Manager

Nick Colucci, Localization Editor

Liz Rita, QA Tester

Brittany Avery, Localization Producer

Thomas Lipschultz, Localization Producer

Question: Has selling your games on PC worked out for you so far? I know supporting the PC platform is a relatively recent choice for XSEED. - @Nate_Nyo

Ken: Being on PC has been great for us as it allows us to reach anyone anywhere in the world regardless of region or console. We were probably one of the earlier adopters in terms of bringing content from Japan to PC as we first published Ys: The Oath in Felghana on Steam almost 6 years ago in early 2012.

Brittany: I love working on PC. The work involved is greater than working on console, but I feel like it's a bigger learning experience, too. For console, the developers normally handle the graphics after we translate them, and they do all the programming and such. For PC, everything falls on us. I wasn't that experienced with Photoshop in the beginning, but I think I've gotten a lot better with it over the years. We can also receive updates instantly, and since I talk with our PC programmer through Skype, it's easier to suss out our exact needs and think of ideas to improve the game or bring it to modern standards.

Question: What non-XSEED games do you praise the localization for? - @KlausRealta

Brittany: Final Fantasy XII. I love everything about Final Fantasy XII's writing. I'm also a big fan of the personality in the Ace Attorney localizations. I'm still playing Yakuza 0, but you can feel the passion of the localization team in the writing. There are some projects where you can tell the editing was phoned in, and then there are games where it's obvious it was a labor of love. All of these games have a color I aspire to.

Tom: Probably going to be a popular answer, and not an especially surprising one, but I've got to give props to Lost Odyssey. It's hard to deny the timeless quality and absolutely masterful English writing that went into basically every line of that game's massive script, with the many short stories being of particular note. That game really does represent an inspirational high bar that I think most everyone else in the industry will forever strive to reach in their own works.

For a more unexpected answer, I've also got to give mad props to Sega for their work on Monster World IV. As a Sega Genesis game released digitally in English for the very first time less than a decade ago, I guess I was kind of expecting a fairly basic "throwaway" translation -- but instead, the game boasts a full-on professional grade localization that's easily up to all modern standards, brimming with charm and personality. It's really nice to see a legitimate retro game being given that kind of care and attention in the modern era, and it makes it very easy for me to recommend (as does the fact that the game is actually quite fun, and is sure to be enjoyed by anyone who's played through all the Shantae titles and really wants to try something else along similar lines).

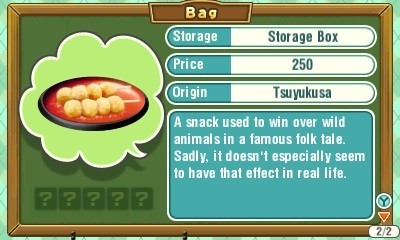

John: I played Okami on PS3 earlier this year (before the remake was announced), and I was awed by how skillfully the team handled text that is chock full of localization challenges like quirky nicknames, references to Japanese fairy tales, and regional dialects. I was especially amused to see a reference to "kibi dango," the dumplings Momotaro uses to bribe his companions in that famous story. We dealt with the same cultural reference with STORY OF SEASONS: Trio of Towns.

Nick: My go-to response is always Vagrant Story, because it’s the game I credit with getting me really interested in a career in localization. Before that point, I had enjoyed games for their story and characters, but hadn’t realized just how much the specific word choices and tone contributed to a reader’s perception of a story as a whole. The gents behind VS’s localization would go on to be industry luminaries, with Rich Amtower now calling shots in Nintendo’s Treehouse department and Alex Smith being synonymous with the highly regarded prose of Yasumi Matsuno’s games – including the cool and underappreciated Crimson Shroud for 3DS, and Final Fantasy XII, which as anyone who’s played it can tell you is a stellar localization. Having spent a lot of time with FFXII’s “The Zodiac Age” remaster this year, the care and attention to detail put into the localization still blows me away. The unique speech style of the Bhujerbans (with...Sri Lankan inflections, if memory serves correctly) sticks with me, because I knew that I myself would never have been able to pull off something like that so deftly. I guess you could say Vagrant Story started a lineage of games that’s always given me something to aspire to as an editor.

Final Fantasy XIV, which I’ve been playing this year, also has a very good localization, especially considering the reams of text that go into an MMO of its size and scope. Michael-Christopher Koji Fox and his team have done a bang-up job giving life and personality to the land of Eorzea, and I’ve enjoyed seeing how the localization has changed in subtle ways as time has gone on. The initial “A Realm Reborn” localization sort of cranks the “regional flavor” up to 11 with heavy dialects and vernacular, but in subsequent expansions, they kind of eased up on that and have found a good mix between grounded localization and the kind of flourishes that work well in high-fantasy settings.

And, while I haven’t played it in a number of years, I remember Dragon Quest VIII having a really great localization, too, with ol’ Yangus still living large in my memories. Tales of the Abyss was fantastic as well, and both DQVIII and Abyss delivered some really brilliant dub work that showed me how much richer one could make characterization when the writing and the acting really harmonized. I still consider Tales of the Abyss my general favorite game dub to date. The casting is perfect, with not a bad role among them. I also want to give mad props to Ni no Kuni’s Mr. Drippy, just as a perfect storm of great localization decisions. Tidy, mun!

Question: How hard is it to turn in game signs and words to English for Japanese? Is it as simple as going in and editing text? Or as hard as creating a whole new texture for the model? - @KesanovaSSB4

Tom: We refer to this as "graphic text" -- meaning, literally, text contained within graphic images. How it's handled differs from project to project, but the short answer is, yeah, it involves creating a whole new texture for the model. Sometimes, this is handled by the developer: they'll just send us a list of all the graphic text images that exist in-game and what each image says, we'll send that list back to them with translations, and they'll use those translations to create new graphic images on our behalf. For other games, however (particularly PC titles we're more or less spearheading), we'll have to do the graphic edits ourselves. When the original PSDs or what-not exist for the sign images, this is generally pretty easy -- but as you might expect, those aren't always available to us, meaning we'll sometimes have to go to a bit more trouble to get this done.

John: The best practice is to review graphic text very early in the localization process because it takes effort to fix and can throw a wrench in schedules if issues are discovered too late. On occasion, it is too difficult to change ubiquitous textures, especially those that might also appear in animation. This was the case with "NewTube" in SENRAN KAGURA Peach Beach Splash, which the localization team wanted to change to "NyuuTube" to make the wordplay clearer to series fans.

Question: With the Steam marketplace becoming increasingly saturated and being seen as a greater risk to publish on in recent times, what does XSEED plan on doing in order to remain prominent and relevant in the PC gaming space? - @myumute

Ken: It is indeed getting harder and harder to stand out as hundreds of new titles are releasing on Steam each month. We are working our way towards simultaneous release across all platforms to help leverage some of the coverage from the console version to get more attention to the PC release, so hopefully that's something we can accomplish soon. For PC-exclusive releases it continues to be a challenge, but at least they have a long tail and even if it's not an immediate success at launch we know it can continue to produce sales for years to come.

Question: What was your favorite film that you saw in 2017, and why? - @Crippeh

John: I'm way behind on movies this year (haven't seen Disaster Artist, Phantom Thread, or Get Out, for example), but recently I've enjoyed both Star Wars and Lady Bird. I expect I'll watch my favorite film from 2017 sometime in 2018.

Ken: Wind River. Mainly because of Jeremy Renner's performance and how many quotable lines he had.

Liz: Get Out for horror mindblowing amazingness, Spider-Man Homecoming for genuinely fun comic book movie, and The Shape of Water for Guillermo del Toro. Guillermo del Toro should always be a category.

That’s it! Stay turned for blog #2 later this week. Here’s a preview of the kinds of questions we’ll be answering:

Question: Have you ever considered selling the music CDs for your licenses stateside? - @LimitTimeGamer

Question: If possible, would you please consider researching and localizing classic Korean-made PC xRPGs? - @DragEnRegalia

Question: Do you have any interest in pursuing the localization of any of the large, beautiful Chinese RPGs that have been hitting Steam? Or are you focused exclusively on Japanese titles? - @TheDanaAddams

Question: What inspired you all to do this kind of work in the first place? Also, what’s the story behind the company name XSEED? How did you all come up with it? - @TBlock_02

Question: What was everyone's favorite game(s) to work on this year? - @ArtistofLegacy

Question: What's everyone's favorite song from the Falcom games you've released so far? - @Crippeh

81 notes

·

View notes

Text

The fraught cultural politics of Disney’s new Aladdin remake

The fraught cultural politics of Disney’s new Aladdin remake

Disney’s live-action Aladdin, a remake of its 1992 animated film, has finally arrived in theaters, and on one level, it’s something of an achievement. The production, helmed by Guy Ritchie, had a hefty amount of cultural baggage to overcome, and has been dogged by controversy and skepticism over its premise and execution since before filming even began.

All the backlash isn’t entirely the 2019 film’s fault. Although the original movie was a critically acclaimed masterpiece, it was also dripping in Orientalism and harmful racist depictions of Arabic culture. The new film has, for the most part, managed to shirk much of its inspiration’s exoticism and cultural inaccuracies, but despite Ritchie’s clear efforts to deliver a more respectful version of Aladdin, it may not be enough to satisfy many of its detractors.

The Council on American-Islamic Relations issued a press release earlier this week asking reviewers and critics to acknowledge that the “Aladdin myth is rooted by racism, Orientalism and Islamophobia” and to “address concerns about racial and religious stereotypes perpetuated by the [new] Disney film.”

Most people think that the story of Aladdin comes from the original 1001 Nights tales, which is a collection of traditional Middle Eastern and Asian folklore. But in fact, Aladdin isn’t a traditional folktale; it has a different history, and it’s one that still causing controversy today.

The tale of Aladdin is born from a hodgepodge of cultural influences — each with an Orientalist viewpoint

Aladdin had no known source before French writer Antoine Galland stuck it into his 18th-century translation of 1001 Nights. Galland claimed to have heard it firsthand from a Syrian storyteller, but claiming your original story came from an exotic faraway source is a common literary device, and it’s likely this Syrian storyteller never existed. In other words, a French guy with a European colonial view of Asia gave us the original Aladdin.

The story’s exoticism — a xenophobic view of other cultures, or people from those cultures, as being somehow strange, unfathomable, or alien — is entrenched in that framing. A specific flavor of exoticism is Orientalism, an idea famously conceptualized by Edward Said. Said was a leading figure in early postcolonial research, and in his 1978 book Orientalism, he outlined literary and narrative tropes that US and European writers used (and still use) to portray Asia and the Middle East as bizarre, regressive, and innately opaque and impossible to understand. The othering of these cultures often takes the form of romanticized depictions of these regions as mysterious or mystic fantasy lands, framed through a colonial perspective.

What’s fascinating about the origins of this tale is that, even though 1001 Nights has been traditionally translated in English as Arabian Nights, the original story was set not in the Arabic world, but in China. Early 19th and 20th-century versions of the story clearly show Aladdin as culturally Asian.

In this illustration of Aladdin, circa 1930, Aladdin and his setting are clearly Chinese

You could even still find many stage depictions of Aladdin as culturally Chinese well into the 20th century, such as in this yellowface production of a British pantomime from 1935:

Aladdin confronts his captor, who’s styled as an Imperial Chinese official

But the Aladdin myth also was a cultural hodgepodge, with many depictions of the story freely mixing Asian elements with European elements. In an 1880 musical burlesque version, Aladdin appeared to have been played by an actor in yellowface, with a contemporaneous setting that seems culturally European:

A musical score of popular songs, arranged by W. Meyer Lutz, from a production of Aladdin, at the Gaiety Theatre, London. Hulton Archive

This tendency to modernize Aladdin continued into the 20th century. As we can see from this archival photo from a 1925 stage production, the story was often presented as a hybrid tale of the exoticized Orient meeting modern English-language styles and fashions.

Truly, a whole new world of cultural appropriation

Following the rise of Hollywood, however, European and American storytellers gradually began transforming Aladdin into a Middle Eastern tale. Movie studios played up the exotic setting and emphasized cultural stereotypes.

This poster for a 1952 film version of Aladdin gives you the idea the filmmakers weren’t all that interested in authenticity

And no Hollywood production did more to solidify this change than Disney’s animated version of Aladdin.

The 1992 Aladdin codified how we think of the story — and the new film had to grapple with that legacy

Perhaps in response to its alleged roots as a Syrian story, the 1992 animated film transplanted the fictional Chinese city of Agrabah to somewhere along the Jordan River. But Disney also gave the film several architectural and cultural flourishes that seem to hail from India — like basing the Sultan’s Palace on the Taj Mahal.

The 1992 film revels in a lot of Orientalist stereotypes: Its mythos reeks of mystical exoticism, with Agrabah explicitly described as a “city of mystery.” Jasmine is a princess who longs to escape an oppressive and controlling culture; her ultimate aim is to gain enough independence to marry for love rather than political expediency, which made her strikingly evolved for the time but seems hopelessly limiting now. Meanwhile, her father, the sultan, is a babbling, easily manipulated man-child. The citizens of Agrabah are frequently depicted as barbarous sword-wielders and sexualized belly dancers. Worse, the opening song, “Arabian Nights,” originally contained the ridiculously racist line, “They cut off your ear if they don’t like your face / It’s barbaric, but hey, it’s home.”

Perhaps most crucially, the film renders its heroes, Aladdin and the Genie, as culturally American. Their wisecracking street-smarts, sheer cunning, and showy braggadocio are all coded as things that set them apart from the residents of Agrabah, and Robin Williams’s famously improvisational jokes as Genie are anachronistically drawn from contemporary American pop culture. In essence, it’s very easy to unthinkingly read Aladdin and the Genie as two Yankees in a land full of exotic Others.

This take on the story became the definitive one, so to release a new version of Aladdin in 2019 is to grapple with all of this baggage at a time when audiences are less likely to turn a blind eye toward it. Things got off to a rocky start: The choice of Ritchie as director — great when it comes to snappy street action, but less so when it comes to nuanced portrayals of race — didn’t exactly inspire a ton of confidence.

Then came one casting controversy after another. An early report that Ritchie and Disney Studios were having trouble casting the lead role, in part because of alleged difficulties finding Arabic and Asian actors who could sing, drew outrage from fans. Then the production was criticized for casting ethnically Indian British actress Naomi Scott as Jasmine, instead of a Middle Eastern or Arabic actress. And then news that the film had added a new white male character to the cast, played by Into the Woods’ Billy Magnussen, raised more eyebrows. (His role ultimately turned out to be a bit part added for comic contrast to Aladdin.)

To top it all off, reports that Disney had been “browning up” some actors on set sparked flabbergasted reactions and drew a swift response from Disney, noting that “great care was taken to put together one of the largest most diverse casts ever seen on screen” and that “diversity of our cast and background performers was a requirement and only in a handful of instances when it was a matter of specialty skills, safety and control (special effects rigs, stunt performers and handling of animals) were crew made up to blend in.”

Given all of this, skepticism over the film has run rampant. Disney and Ritchie seem to have taken pains to deliver a respectful film: They’ve written more three-dimensionality into most of the main characters, especially Jasmine and the Genie, and they’ve removed much of the exotic stereotypes of the film’s predecessor. Still, there remains a lack of confidence in their final product. The Council on American-Islamic Relations noted before the film’s US debut that “as seen through the trailer, the racist themes of the original animated cartoon seemingly reemerge in the live-action remake, despite efforts by Disney to address the concerns from 25 years ago.”

Then there’s the tense sociocultural context in which this new live-action film is appearing. At any other time, Aladdin might have been little more than a dose of multiculturalism, but it has emerged at a moment when global politics are deeply fraught, progressives have fought hard for ethnically diverse and authentic cinema, and extremists — everyone from actual radicals to media fans engaging in online review bombing — have demonized and attacked the very idea of multicultural representation. The Council on American-Islamic Relations was also wary of this, warning that releasing the film “during the Trump era of rapidly rising anti-Muslim, anti-immigrant and racist animus only serves to normalize stereotyping and to marginalize minority communities.”

All of these factors have created a rocky path for the movie, and seem to have hindered its route to finding critical success; currently, reviews are decidedly mixed. But Disney is a global powerhouse whose films can shape cultural perceptions for generations, and Aladdin will doubtless have plenty of pull at the box office. So for better or for worse, Aladdin’s crossed cultural signals and its troubling legacy will probably be with us for a very long time to come.

The post The fraught cultural politics of Disney’s new Aladdin remake appeared first on trending tee shirt.

from http://bit.ly/2W7j19z

1 note

·

View note

Text

The fraught cultural politics of Disney’s new Aladdin remake

Link Buys Now: https://kingteeshops.com/the-fraught-cultural-politics-of-disneys-new-aladdin-remake/

The fraught cultural politics of Disney’s new Aladdin remake

The fraught cultural politics of Disney’s new Aladdin remake

Disney’s live-action Aladdin, a remake of its 1992 animated film, has finally arrived in theaters, and on one level, it’s something of an achievement. The production, helmed by Guy Ritchie, had a hefty amount of cultural baggage to overcome, and has been dogged by controversy and skepticism over its premise and execution since before filming even began.

All the backlash isn’t entirely the 2019 film’s fault. Although the original movie was a critically acclaimed masterpiece, it was also dripping in Orientalism and harmful racist depictions of Arabic culture. The new film has, for the most part, managed to shirk much of its inspiration’s exoticism and cultural inaccuracies, but despite Ritchie’s clear efforts to deliver a more respectful version of Aladdin, it may not be enough to satisfy many of its detractors.

The Council on American-Islamic Relations issued a press release earlier this week asking reviewers and critics to acknowledge that the “Aladdin myth is rooted by racism, Orientalism and Islamophobia” and to “address concerns about racial and religious stereotypes perpetuated by the [new] Disney film.”

Most people think that the story of Aladdin comes from the original 1001 Nights tales, which is a collection of traditional Middle Eastern and Asian folklore. But in fact, Aladdin isn’t a traditional folktale; it has a different history, and it’s one that still causing controversy today.

The tale of Aladdin is born from a hodgepodge of cultural influences — each with an Orientalist viewpoint

Aladdin had no known source before French writer Antoine Galland stuck it into his 18th-century translation of 1001 Nights. Galland claimed to have heard it firsthand from a Syrian storyteller, but claiming your original story came from an exotic faraway source is a common literary device, and it’s likely this Syrian storyteller never existed. In other words, a French guy with a European colonial view of Asia gave us the original Aladdin.

The story’s exoticism — a xenophobic view of other cultures, or people from those cultures, as being somehow strange, unfathomable, or alien — is entrenched in that framing. A specific flavor of exoticism is Orientalism, an idea famously conceptualized by Edward Said. Said was a leading figure in early postcolonial research, and in his 1978 book Orientalism, he outlined literary and narrative tropes that US and European writers used (and still use) to portray Asia and the Middle East as bizarre, regressive, and innately opaque and impossible to understand. The othering of these cultures often takes the form of romanticized depictions of these regions as mysterious or mystic fantasy lands, framed through a colonial perspective.

What’s fascinating about the origins of this tale is that, even though 1001 Nights has been traditionally translated in English as Arabian Nights, the original story was set not in the Arabic world, but in China. Early 19th and 20th-century versions of the story clearly show Aladdin as culturally Asian.

In this illustration of Aladdin, circa 1930, Aladdin and his setting are clearly Chinese

You could even still find many stage depictions of Aladdin as culturally Chinese well into the 20th century, such as in this yellowface production of a British pantomime from 1935:

Aladdin confronts his captor, who’s styled as an Imperial Chinese official

But the Aladdin myth also was a cultural hodgepodge, with many depictions of the story freely mixing Asian elements with European elements. In an 1880 musical burlesque version, Aladdin appeared to have been played by an actor in yellowface, with a contemporaneous setting that seems culturally European:

A musical score of popular songs, arranged by W. Meyer Lutz, from a production of Aladdin, at the Gaiety Theatre, London. Hulton Archive

This tendency to modernize Aladdin continued into the 20th century. As we can see from this archival photo from a 1925 stage production, the story was often presented as a hybrid tale of the exoticized Orient meeting modern English-language styles and fashions.

Truly, a whole new world of cultural appropriation

Following the rise of Hollywood, however, European and American storytellers gradually began transforming Aladdin into a Middle Eastern tale. Movie studios played up the exotic setting and emphasized cultural stereotypes.

This poster for a 1952 film version of Aladdin gives you the idea the filmmakers weren’t all that interested in authenticity

And no Hollywood production did more to solidify this change than Disney’s animated version of Aladdin.

The 1992 Aladdin codified how we think of the story — and the new film had to grapple with that legacy

Perhaps in response to its alleged roots as a Syrian story, the 1992 animated film transplanted the fictional Chinese city of Agrabah to somewhere along the Jordan River. But Disney also gave the film several architectural and cultural flourishes that seem to hail from India — like basing the Sultan’s Palace on the Taj Mahal.

The 1992 film revels in a lot of Orientalist stereotypes: Its mythos reeks of mystical exoticism, with Agrabah explicitly described as a “city of mystery.” Jasmine is a princess who longs to escape an oppressive and controlling culture; her ultimate aim is to gain enough independence to marry for love rather than political expediency, which made her strikingly evolved for the time but seems hopelessly limiting now. Meanwhile, her father, the sultan, is a babbling, easily manipulated man-child. The citizens of Agrabah are frequently depicted as barbarous sword-wielders and sexualized belly dancers. Worse, the opening song, “Arabian Nights,” originally contained the ridiculously racist line, “They cut off your ear if they don’t like your face / It’s barbaric, but hey, it’s home.”

Perhaps most crucially, the film renders its heroes, Aladdin and the Genie, as culturally American. Their wisecracking street-smarts, sheer cunning, and showy braggadocio are all coded as things that set them apart from the residents of Agrabah, and Robin Williams’s famously improvisational jokes as Genie are anachronistically drawn from contemporary American pop culture. In essence, it’s very easy to unthinkingly read Aladdin and the Genie as two Yankees in a land full of exotic Others.

This take on the story became the definitive one, so to release a new version of Aladdin in 2019 is to grapple with all of this baggage at a time when audiences are less likely to turn a blind eye toward it. Things got off to a rocky start: The choice of Ritchie as director — great when it comes to snappy street action, but less so when it comes to nuanced portrayals of race — didn’t exactly inspire a ton of confidence.

Then came one casting controversy after another. An early report that Ritchie and Disney Studios were having trouble casting the lead role, in part because of alleged difficulties finding Arabic and Asian actors who could sing, drew outrage from fans. Then the production was criticized for casting ethnically Indian British actress Naomi Scott as Jasmine, instead of a Middle Eastern or Arabic actress. And then news that the film had added a new white male character to the cast, played by Into the Woods’ Billy Magnussen, raised more eyebrows. (His role ultimately turned out to be a bit part added for comic contrast to Aladdin.)

To top it all off, reports that Disney had been “browning up” some actors on set sparked flabbergasted reactions and drew a swift response from Disney, noting that “great care was taken to put together one of the largest most diverse casts ever seen on screen” and that “diversity of our cast and background performers was a requirement and only in a handful of instances when it was a matter of specialty skills, safety and control (special effects rigs, stunt performers and handling of animals) were crew made up to blend in.”