#byzantine emperors or visigoths or

Text

my favorite kind of history twitter tweet is historians being like "why isn't there a period drama about [cool events in my area of study]?!" and they then list the reasons (intrigue, drama) and conclude that it has nothing to envy game of thrones— and the thing is they are right. it's just that every single period of history everywhere on earth has these things and your niche historical period is never gonna get anything when producers can just do tudor show n23793 or 18th century french court for the 36829th time lol

#most recent one was about peter i of castille but i regularly see them about idk 15th century burgundians or habsburgs in any century or#byzantine emperors or visigoths or#my posts

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

So I know my homoiousios vs. homoousios, and my monophysite vs. dyophysite, and my monothelite vs. dyothelite, and how it all led to the Arab caliphates getting a decent navy and winning the Battle of the Masts.

I don't, and I'd love to! (If you feel like it, obviously.) I'm pretty sure the homoiousios one is about, like, the Trinity or something, but beyond that it's all Greek to me.

(At this point, I feel like I owe @apocrypals royalties or something, but I'm getting a weird kick from doing this on Saint Patrick's Day, so let's do this).

I covered the impact of the monophysite vs. dyophysite split and the Battle of the Masts here, so I'll start from the top.

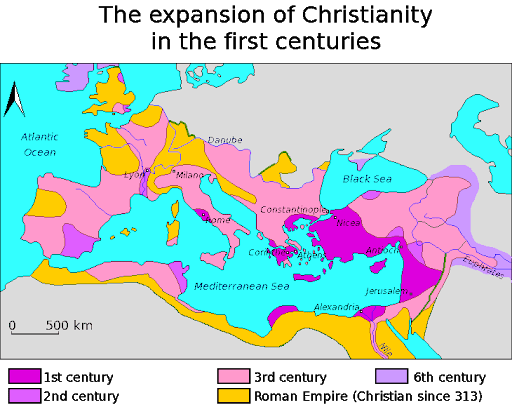

You are quite correct that the homoiousios vs. homoousios split was, like most of the heresies of the early Church, a Cristological controversy over the nature of Christ and the Trinity. This is perhaps better known as the Arian Heresy, and it's arguably the great-granddaddy of all heresies.

The Arian heresy was the subject of the very first Council of the early Church, the Council of Nicea, convoked by Emperor Constantine the Great in order to end all disputes within the Church forever. (Clearly this worked out well.) In part because the Church hadn't really sat down and attempted to establish orthodoxy before, this debate got very heated. Famously, at one point the future Saint Nicholas supposedly punched Presbyter Arius in the face.

What got a room of men devoted to the "Prince of Peace" heated to the point of physical violence was that Arius argued that, while Christ was the son of God and thus clearly divine, because he was created by God the Father and thus came after the Father, he couldn't be of the same essence (homoousios) as the Father, but rather of similar essence (homoiousios). Eustathias of Antioch and Alexander of Alexandria took the opposing position, which got formulated into the Nicean Creed. As this might suggest, Arius lost both the debate and the succeeding vote that followed, as roughly 298 of 300 bishops attending signed onto the Creed. This got very bad for Arius indeed, because Emperor Constantine enforced the new policy by ordering his writings burned, and Arius and two of his supporters were exiled to Illyricum. Game over, right?

But something odd happened: the dispute kept going, as new followers of Arius popped up and showed themselves to be much better at the Byzantine knife-fighting of Church politics. About ten years later, the ever-unpredictable Constantine turned against Athanasius of Alexandria (who had been Alexander's campaign manager, in essence) and banished him for intruiging against Arius, while Arius was allowed to return to the church (this time in Jerusalem) - although this turned out to be mostly a symbolic victory as Arius died on the journey and didn't live to see his readmission.

....and then it turned out that Constantine the Great's son Constantius II was an Arian and he reversed policy completely, adopting the Arian position and exiling anyone who disagreed with him, up to and including Pope Liberius. While the Niceans eventually triumphed during the reign of Theodosius the Great, Arianism unexpectedly became a major geopolitical issue within the Empire.

See, both during their exile and during their brief period of ascendancy within the Church, one of the major projects of the Arians was to send out missionaries into the west to preach their version of Christianity. Unexpectedly, Arianism proved to be a big hit among the formerly pagan Goths (thanks in no small part to the missionary Ulfilas translating the Bible into Gothic), who were perhaps more familiar with pantheons in which patriarchal gods were considered senior to their sons.

While they weren't particularly given to persecuting Niceans in the West, the Ostrogothic, Visigothic, Burgundian, and Vandal Kings weren't about to let themselves be pushed around by some Roman prick in Constantinople either - which added an interesting religious component to Justinian's attempt to reconquer the West.

27 notes

·

View notes

Note

So re your tags on the pope post...

Where's the menorah krindor?

So, starting at the very beginning.

70 CE: Titus sacks Jerusalem and loots the Second Temple. In his triumph (fancy war parade) he has the Menorah, as is recorded by Josephus Flavius in 71 CE and by the Arch of Titus' reliefs in 81 CE

The Menorah is displayed in the Tempulum Pacis in Rome, and 2nd century CE Rabbis claim to have seen it in Rome, as well as various other artifacts from the desroyed temple including the parochet and the choshen.

Now here's the thing. This is the last time historical texts mention the Menorah by name so everything below here needs to be taken with an increasing pile of salt

410 CE: The Visigoths sack Rome. Procipius of Ceasarea (500-560), a Byzantine Historian, writes that the Visigoths take "treasures of Solomon the King of the Hebrews." If this includes the Menorah, the trail goes cold. So that's it right? The Menorah got taken to a secondary location and was lost forever, right?

Wrong, because that's not the only time Procipius mentions Jewish Temple loot.

425 CE: The Vandals sack Rome again, to the point where the word vandalize comes from it. Procipius notes that their leader, Geiseric, takes "a huge amount of imperial treasure" with him to Carthage, which was at that time the Vandal capital.

Trust me this is relevant

534 CE: The Byzantine Emperor Justinian sacks Carthage, and they hold a triumph in Constantinople. Among the paraded items are "treasures of the Jews, which Titus, the son of Vespasian, together with certain others, had brought to Rome after the capture of Jerusalem”

That these "treasures of the Jews" include the Menorah is not a new theory, as is indicated in the 19th century painting Geiseric sacking Rome by Karl Bryullov

(Note the Menorah)

So it's in Istanbul right?

Wrong, because our boy Procipius isn't done yet: according to him, Justinian sent the "treasures of the Jews" to Christian sanctuaries in Jerusalem, since he heard that they were cursed that any city save Jerusalem that held them was doomed to be sacked.

This is the last time the "treasures of the Jews" are mentioned in historical texts.

So for our next step, lets look at major churches in Jerusalem in the 6th century, and officially enter the cork-board and string section of this rant post.

As well as the extant Church of the Holy Sepulcher, the Hagia Sion Basilica, and the Church of the Holy Apostles, Justinian built a church himself in the city, called the Nea, in 534 CE, just nine years after sacking Carthage. It would not be unreasonable that he'd send the Menorah to his own church, so we can theorize that it's in the Nea for the remainder of the 6th century (there are, of course, problems with relying on one historian's account of these things, but this is for fun, not a published article)

So that's it? It's in one of the churches of Jerusalem?

...

So in 614 CE Jerusalem gets sacked by the Sasanian/Persian Empire, who according to historical records destroy all the churches.

Now here's the thing. Recent archaeological evidence gives rise to the possibility that our Byzantine historical sources are trying to stir up outrage against the Sasanians: While mass graves dating to around 614 CE were found, the churches and Christian residential neighborhoods were barely, if at all, damaged, and the Nea itself was very possibly completely undamaged. This is, however, a recent theory, and the academics are still hashing it out.

So it may be in one of the churches of Jerusalem?

Tragically, even if the 614 siege didn't get the churches, in 1009 the Fatimid Caliph al-Hakim bi-Amr Allah destroyed all churches, synagogues, and many religious artifacts of both Christians and Jews in Jerusalem. So if by some miracle the Menorah had survived until this point, if it was in Jerusalem it was most likely destroyed.

But that's disappointing, and what's a good conspiracy theory without going a step or two beyond what is reasonable?

Apparently, while the churches, synagogues and most of the artifacts were destroyed, at least in the case of the Church of the Holy Sepulcher, objects that could be carried away were looted, rather than destroyed. And if we know anything about the Menorah at this point, that thing is certainly able to be carried away by people.

If the Menorah was looted rather than destroyed, it's not unreasonable that it would have made it's way to the Fatimid capital of Cairo. However, as the historical record dried up some 500 years beforehand, beyond this point it's unreasonable to attempt to track the Menorah.

So that's it. If the Menorah wasn't destroyed it most likely made its way to Egypt and was lost or destroyed there.

Is what I'd say if I wasn't so far down this rabbit hole I was beyond reason. Because as we all know there's one place that has all the significant treasures of Cairo and a penchant for looting:

The British Museum

#i cant in good conscience call this either archaeology or history#anyway this is very unhinged but was fun to research#pseudoarchaeology#pseudohistory#jewish stuff

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

VANDAL nobleman and MAURI mercenary in North Africa, somewhere south of the Atlas (5th century AD). The aesthetic of the Vandal is based on 5th or 6th century mosaics from Carthage (Tunisia), which was the capital of the Vandals at the time. He wears a Late Roman “Coptic” tunic, and a barbarian tartan-like cloak. Contrary to the Germanic tradition of sporting a full beard and long hair, the Roman and Asiatic influences are visible in his short hair and moustache. He carries a sword decorated with garnet cloisonné, which is based on a find from a warrior’s grave from Beja (Portugal). This sword has Asiatic influence, as a result of the Vandal’s coexistence with the nomadic Alans in Hispania. Similar swords were also used by the Huns. The clothing of the Mauri (an ancient Amazigh people of modern-day northern Morocco and Algeria, also known today as the Moors) is based on a 4th-6th century stele from Djorf Torba (Algeria), and the hairstyle is based on Roman representations of Mauretanians and Numidians. The shield, made of elephant hide, is painted with motifs based on representations of shields in Prehistoric rock art of the Moroccan Atlas. The huts in the background are based on a Roman mosaic from El Alia (Tunisia).

THE VANDALS were a Germanic tribe of Scandinavian origin that migrated from the Baltic region to Central Europe and then Roman Gaul, finally conquering part of the Iberian Peninsula alongside the Iranic-speaking Alans (who had migrated from the Caucasus). The Vandals and the Alans ruled Hispania until they were pushed to Africa by another Germanic tribe: the Visigoths. The Vandals and the Alans managed to conquer Roman Africa, and from there, they launched a fleet of ships to Italy and sacked Rome in 455 AD. The “Eternal City” had already been sacked by the Visigoths in 410 AD. The Western Roman Empire finally collapsed in 476 AD. The Vandal kingdom would last until 534 AD, when it was destroyed by the Eastern Roman general Belisarius as part of emperor Justinian’s restoration of the Roman West. The Eastern Romans, or Byzantines, retained control of the Maghreb until the Islamic conquest of the 7th century.

HQ + close-ups: https://www.artstation.com/artwork/rJEKNE

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Events 4.6 (before 1940)

46 BC – Julius Caesar defeats Caecilius Metellus Scipio and Marcus Porcius Cato (Cato the Younger) at the Battle of Thapsus.

402 – Stilicho defeats the Visigoths under Alaric in the Battle of Pollentia.

1320 – The Scots reaffirm their independence by signing the Declaration of Arbroath.

1453 – Mehmed II begins his siege of Constantinople. The city falls on May 29, and is renamed Istanbul.

1580 – One of the largest earthquakes recorded in the history of England, Flanders, or Northern France, takes place.

1652 – At the Cape of Good Hope, Dutch sailor Jan van Riebeeck establishes a resupply camp that eventually becomes Cape Town.

1712 – The New York Slave Revolt of 1712 begins near Broadway.

1776 – American Revolutionary War: Ships of the Continental Navy fail in their attempt to capture a Royal Navy dispatch boat.

1782 – King Buddha Yodfa Chulaloke (Rama I) of Siam (modern day Thailand) establishes the Chakri dynasty.

1793 – During the French Revolution, the Committee of Public Safety becomes the executive organ of the republic.

1800 – The Treaty of Constantinople establishes the Septinsular Republic, the first autonomous Greek state since the Fall of the Byzantine Empire. (Under the Old Style calendar then still in use in the Ottoman Empire, the treaty was signed on 21 March.)

1808 – John Jacob Astor incorporates the American Fur Company, that would eventually make him America's first millionaire.

1812 – British forces under the command of the Duke of Wellington assault the fortress of Badajoz. This would be the turning point in the Peninsular War against Napoleon-led France.

1814 – Nominal beginning of the Bourbon Restoration; anniversary date that Napoleon abdicates and is exiled to Elba.

1830 – Church of Christ, the original church of the Latter Day Saint movement, is organized by Joseph Smith and others at either Fayette or Manchester, New York.

1841 – U.S. President John Tyler is sworn in, two days after having become president upon William Henry Harrison's death.

1860 – The Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints, later renamed Community of Christ, is organized by Joseph Smith III and others at Amboy, Illinois.

1862 – American Civil War: The Battle of Shiloh begins: In Tennessee, forces under Union General Ulysses S. Grant meet Confederate troops led by General Albert Sidney Johnston.

1865 – American Civil War: The Battle of Sailor's Creek: Confederate General Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia fights and loses its last major battle while in retreat from Richmond, Virginia, during the Appomattox Campaign.

1866 – The Grand Army of the Republic, an American patriotic organization composed of Union veterans of the American Civil War, is founded. It lasts until 1956.

1896 – In Athens, the opening of the first modern Olympic Games is celebrated, 1,500 years after the original games are banned by Roman emperor Theodosius I.

1909 – Robert Peary and Matthew Henson become the first people to reach the North Pole; Peary's claim has been disputed because of failings in his navigational ability.

1911 – During the Battle of Deçiq, Dedë Gjon Luli Dedvukaj, leader of the Malësori Albanians, raises the Albanian flag in the town of Tuzi, Montenegro, for the first time after George Kastrioti (Skanderbeg).

1917 – World War I: The United States declares war on Germany.

1918 – Finnish Civil War: The battle of Tampere ends.

1926 – Varney Airlines makes its first commercial flight (Varney is the root company of United Airlines).

1929 – Huey P. Long, Governor of Louisiana, is impeached by the Louisiana House of Representatives.

1930 – At the end of the Salt March, Gandhi raises a lump of mud and salt and declares, "With this, I am shaking the foundations of the British Empire."

1936 – Tupelo–Gainesville tornado outbreak: Another tornado from the same storm system as the Tupelo tornado hits Gainesville, Georgia, killing 203.

0 notes

Text

Absolute Monarchs: A History of the Papacy - J. J. Norwich

2,000 Years of Popes, Sacred and Profane

By Bill Keller

July 7, 2011

John Julius Norwich makes a point of saying in the introduction to his history of the popes that he is “no scholar” and that he is “an agnostic Protestant.” The first point means that while he will be scrupulous with his copious research, he feels no obligation to unearth new revelations or concoct revisionist theories. The second means that he has “no ax to grind.” In short, his only agenda is to tell us the story.

And he has plenty of story to tell. “Absolute Monarchs” sprawls across Europe and the Levant, over two millenniums, and with an impossibly immense cast: 265 popes (plus various usurpers and antipopes), feral hordes of Vandals, Huns and Visigoths, expansionist emperors, Byzantine intriguers, Borgias and Medicis, heretic zealots, conspiring clerics, bestial inquisitors and more. Norwich manages to organize this crowded stage and produce a rollicking narrative. He keeps things moving at nearly beach-read pace by being selective about where he lingers and by adopting the tone of an enthusiastic tour guide, expert but less than reverent.

A scholar or devout Roman Catholic would probably not have had so much fun, for example, with the tale of Pope Joan, the mid-ninth-century Englishwoman who, according to lore, disguised herself as a man, became pope and was caught out only when she gave birth. Although Norwich regards this as “one of the hoariest canards in papal history,” he cannot resist giving her a chapter of her own. It is a guilty pleasure, especially his deadpan pursuit of the story that the church, determined not to be fooled again, required subsequent papal candidates to sit on a chaise percée (pierced chair) and be groped from below by a junior cleric, who would shout to the multitude, “He has testicles!” Norwich tracks down just such a piece of furniture in the Vatican Museum, dutifully reports that it may have been an obstetric chair intended to symbolize Mother Church, but adds, “It cannot be gainsaid, on the other hand, that it is admirably designed for a diaconal grope; and it is only with considerable reluctance that one turns the idea aside.”

If you were raised Catholic, you may find it disconcerting to see an institution you were taught to think of as the repository of the faith so thoroughly deconsecrated. Norwich says little about theology and treats doctrinal disputes as matters of diplomacy. As he points out, this is in keeping with many of the popes themselves, “a surprising number of whom seem to have been far more interested in their own temporal power than in their spiritual well-being.” For most of their two millenniums, the popes were rulers of a large sectarian state, managers of a civil service, military strategists, occasionally battlefield generals, sometimes patrons of the arts and humanities, and, importantly, diplomats. They were indeed monarchs. (But not, it should be said, “absolute monarchs.” Whichever editor persuaded Norwich to change his British title, “The Popes: A History,” may have done the book a marketing favor but at the cost of accuracy: the popes’ power was invariably shared with or subordinated to emperors and kings of various stripes. In more recent times, the popes have had no civil power outside the 110 acres of Vatican City, no military at all, and even their moral authority has been flouted by legions of the faithful.)

Norwich, whose works of popular history include books on Venice and Byzantium, admires the popes who were effective statesmen and stewards, including Leo I, who protected Rome from the Huns; Benedict XIV, who kept the peace and instituted financial and liturgical reforms, allowing Rome to become the religious and cultural capital of Catholic Europe; and Leo XIII, who steered the Church into the industrial age. The popes who achieved greatness, however, were outnumbered by the corrupt, the inept, the venal, the lecherous, the ruthless, the mediocre and those who didn’t last long enough to make a mark.

Sinners, as any dramatist or newsman can tell you, are more entertaining than saints, and Norwich has much to work with. If you paid attention in high school, you know something of the Borgia popes, who are covered in a chapter succinctly called “The Monsters.” But they were not the first, the last or even the most colorful of the sacred scoundrels. The bishops who recently blamed the scourge of pedophile priests on the libertine culture of the 1960s should consult Norwich for evidence that clerical abuses are not a historical aberration.

Of the minor 15th-century Pope Paul II, to pick one from the ranks of the debauched, Norwich writes: “The pope’s sexual proclivities aroused a good deal of speculation. He seems to have had two weaknesses — for good-looking young men and for melons — though the contemporary rumor that he enjoyed watching the former being tortured while he gorged himself on the latter is surely unlikely.”

Sexual misconduct figures prominently in the history of the papacy (another chapter is entitled “Nicholas I and the Pornocracy”) but is hardly the only blot on the institution. Clement VII, the disastrous second Medici pope, oversaw “the worst sack of Rome since the barbarian invasions, the establishment in Germany of Protestantism as a separate religion and the definitive breakaway of the English church over Henry VIII’s divorce.” Paul IV “opened the most savage campaign in papal history against the Jews,” forcing them into ghettos and destroying synagogues. Gregory XIII spent the papacy into penury. Urban VIII imprisoned Galileo and banned all his works.

Most of the popes, being human, were complicated; the rogues had redeeming features, the capable leaders had defects. Innocent III was the greatest of the medieval popes, a man of galvanizing self-confidence who consolidated the Papal States. But he also initiated the Fourth Crusade, which led to the wild sacking of Constantinople, “the most unspeakable of the many outrages in the whole hideous history of the Crusades.” Sixtus IV sold indulgences and church offices “on a scale previously unparalleled,” made an 8-year-old boy the archbishop of Lisbon and began the horrors of the Spanish Inquisition. But he also commissioned the Sistine Chapel.

Even the Borgia pope Alexander VI, who by the time he bribed his way into office had fathered eight children by at least three women, is credited with keeping the imperiled papacy alive by capable administration and astute diplomacy, “however questionable his means of doing so.”

By the time we reach the 20th century, about 420 pages in, our expectations are not high. We get a disheartening chapter on Pius XI and Pius XII, whose fear of Communism (along with the church’s long streak of anti-Semitism) made them compliant enablers of Mussolini, Hitler and Franco. Pius XI, in Norwich’s view, redeemed himself by his belated but unflinching hostility to the Fascists and Nazis. But his indictment of Pius XII — who resisted every entreaty to speak out against mass murder, even as the trucks were transporting the Jews of Rome to Auschwitz — is compact, evenhanded and devastating. “It is painful to have to record,” Norwich concludes, “that, on the orders of his successor, the process of his canonization has already begun. Suffice it to say here that the current fashion for canonizing all popes on principle will, if continued, make a mockery of sainthood.”

Norwich devotes exactly one chapter to the popes of my lifetime — from the avuncular modernizer John XXIII, whom he plainly loves, to the austere Benedict, off to a “shaky start.” He credits the popular Polish pope, John Paul II — another candidate for sainthood — for his global diplomacy but faults his retrograde views on matters of sex and gender. Norwich’s conclusion may remind readers that he introduced himself as a Protestant agnostic, because whatever his views on God, his views on the papacy are clearly pro-reformation.

“It is now well over half a century since progressive Catholics have longed to see their church bring itself into the modern age,” he writes. “With the accession of every succeeding pontiff they have raised their hopes that some progress might be made on the leading issues of the day — on homosexuality, on contraception, on the ordination of women priests. And each time they have been disappointed.”

0 notes

Note

I don't know anything about Medieval History, tell me things please.

Sooo, Middle Ages are that long period of time, roughly 1000 years, between antiquity and modern period. We usually refer to Medieval History meaning European Medieval Hisrory, other civilizations had their own Middle Ages in different times (for example Indian Middle Ages started in 8th century and ended in 18th, even if the start is debated).

European Middle Ages conventionally start in 476, when the last Western Roman Empire was deposed. But actually there are different dates marking the end of Rome's antiquity and the start of Middle Ages: someone believes it's 410, the year Rome was sacked by Visigoths and when the emperors became puppets controlled by barbarian generals. Others think it's 480, when another controversially deposed emperor (Nepote) died in Dalmatia. The fall of Rome and the passage to Middle Ages was probably more slow and silent than it's usually portrayed. Keep in mind also that Middle Ages is a later concept, no one was aware of living in MAs back then.

Same for the ending, some say it's 1492 ("discovery" of the Americas), others 1453 (end of the Hundred Years' War and conquest of Costantinople by Ottomans), but actually it's a symbolic date in both cases since there already were elements of modernity like corporations and gunpowder.

Middle Ages are largely known due to stereotypes that in most cases turn out to be distorted or entirely wrong. Some examples? Inquisition only appeared in the final centuries of MAs, witch hunts are a Modern period issue, knights with full armors and castles are from the last MAs centuries too. The ideas we have of Medieval times is focused on 12th to 15th centuries, forgetting the others starting in fifth or even before if we include Late Antiquity.

Middle Ages had very different times, and it's the period when modern kingdoms started to rise. The first part of Middle Ages, roughly from V to IX century, is the time of Roman-barbarian kingdoms, when Roman model was imitated, inspiration came from the past: Vandals, Franks, Lombards, Visigoths, Anglo-saxons... Eastern Roman Empire was the only element of real continuity with the Romans, it took the name of Byzantine Empire and lasted throughout all of the Middle Ages.

After Charlemagne, in IX century the process of creation of feudal kingdoms started, it was very chaotic and the outcome was a more or less stable ensamble of new kingdoms: Germany/Holy Roman Empire, Italy, England, France, Spain. Of course there's MORE than this but it'd become a long, long post. After that, in XIII century, we have the Late Middle Ages, with sacred kings, and important medieval cities: the communes.

Middle Ages were then important for the rise of kingdoms, but also the birth of power of the Church and pope, the birth of Islam, and a new unprecedented system of societies heavily based on religion as an element of unity and legitimation.

If there's anything specific you're curious about, feel free to ask ♠️⚔️♠️

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Roman Empire was one of the most powerful and influential empires in history. It was founded in 27 BCE, when the Roman Republic, which had been plagued by political instability and civil war, was transformed into an empire under the rule of Augustus, the first Roman emperor. The empire reached its peak during the 2nd century CE, when it controlled a vast territory stretching from modern-day Spain and Britain in the west, to Egypt and the Near East in the south, and as far as the Danube and Rhine rivers in the north.

However, despite its military and economic prowess, the Roman Empire eventually began to decline. There are many factors that contributed to its fall, but some of the most significant include:

Military overspending and overreaching: The empire spent a large portion of its resources on maintaining a vast army, which was necessary to defend its borders and put down rebellions. This eventually led to economic instability and financial crisis.

Political corruption and instability: The empire was plagued by political corruption, as powerful individuals and factions fought for control of the government. This instability led to a lack of strong leadership and decision-making, which hindered the empire's ability to respond to challenges.

Invasions and barbarian migrations: The empire was also under constant threat from barbarian tribes, such as the Visigoths, Huns, and Franks. These invasions put a strain on the empire's resources and weakened its borders, making it more vulnerable to attacks.

Economic troubles: The empire's economy was dependent on slave labor and the exploitation of conquered territories, which led to a lack of economic growth and prosperity. The empire also had an inflation problem, the government was heavily issuing coinage and debasing the currency, this led to an increased cost of living which further weakened the economy.

Spread of Christianity: The official religion of the Roman Empire was polytheistic, but the rise of Christianity throughout the empire, particularly among the lower classes, led to religious tensions and divided loyalties.

These factors, along with others, contributed to the decline and fall of the Roman Empire. The empire officially came to an end in 476 CE, when the barbarian Odoacer deposed the last Roman emperor, Romulus Augustus, and established the kingdom of Italy. Although the Roman Empire fell, its legacy lived on through the Eastern Roman Empire (Byzantine Empire) which lasted for another 1000 years.

It's important to note that the fall of the Roman Empire was a gradual process that took several centuries, not a sudden collapse, and it also opened the door for new civilization to rise such as the medieval Europe and the Islamic Caliphate.

0 notes

Photo

Extent of the Visigothic Kingdom, c. 500 (total extent shown in orange, territory lost after Battle of Vouillé shown in light orange: Kingdom of the Suebi was annexed in 585)

The Visigothic Kingdom, officially the Kingdom of the Goths (Latin: Regnum Gothorum), was a kingdom that occupied what is now southwestern France and the Iberian Peninsula from the 5th to the 8th centuries. One of the Germanic successor states to the Western Roman Empire, it was originally created by the settlement of the Visigoths under King Wallia in the province of Gallia Aquitania in southwest Gaul by the Roman government and then extended by conquest over all of Hispania. The Kingdom maintained independence from the Eastern Roman or Byzantine Empire, whose attempts to re-establish Roman authority in Hispania were only partially successful and short-lived.

The Visigoths were romanized central Europeans who had moved west from the Danube Valley.[4] They became foederati of Rome, and wanted to restore the Roman order against the hordes of Vandals, Alans and Suebi. The Western Roman Empire fell in 476 AD; therefore, the Visigoths believed they had the right to take the territories that Rome had promised in Hispania in exchange for restoring the Roman order.[5] Under King Euric—who eliminated the status of foederati—a triumphal advance of the Visigoths began.[citation needed] Alarmed at Visigoth expansion from Aquitania after victory over the Gallo-Roman and Breton armies[6] at Déols in 469, Western Emperor Anthemius sent a fresh army across the Alps against Euric, who was besieging Arles. The Roman army was crushed in battle nearby and Euric then captured Arles and secured much of southern Gaul.[citation needed]

Sometimes referred to as the Regnum Tolosae or Kingdom of Toulouse after its capital Toulouse in modern historiography, the kingdom lost much of its territory in Gaul to the Franks in the early 6th century, save the narrow coastal strip of Septimania.[citation needed] The kingdom of the 6th and 7th centuries is sometimes called the Regnum Toletanum or Kingdom of Toledo after the new capital of Toledo in Hispania.[citation needed] A civil war starting in 549 resulted in an invitation from the Visigoth Athanagild, who had usurped the kingship, to the Byzantine emperor Justinian I to send soldiers to his assistance.[citation needed] Athanagild won his war, but the Byzantines took over Cartagena and a good deal of southern Hispania, until 624 when Swinthila expelled the last Byzantine garrisons from the peninsula, occupying Orcelis, which the Visigoths called Aurariola (today Orihuela in the Province of Alicante).[citation needed] Starting in the 570s Athanagild's brother Liuvigild compensated for this loss by conquering the Kingdom of the Suebi in Gallaecia (corresponding roughly to present-day Galicia and the northern part of Portugal) and annexing it, and by repeated campaigns against the Basques.[citation needed]

The ethnic distinction between the Hispano-Roman population and the Visigoths had largely disappeared by this time (the Gothic language lost its last and probably already declining function as a church language when the Visigoths renounced Arianism in 589).[7] This newfound unity found expression in increasingly severe persecution of outsiders, especially the Jews. The Visigothic Code, completed in 654, abolished the old tradition of having different laws for Hispano-Romans and for Visigoths. The 7th century saw many civil wars between factions of the aristocracy. Despite good records left by contemporary bishops, such as Isidore and Leander of Seville, it becomes increasingly difficult to distinguish Goths from Hispano-Romans, as the two became inextricably intertwined. Despite these civil wars, by 625 AD the Visigoths had succeeded in expelling the Byzantines from Hispania and had established a foothold at the port of Ceuta in Africa. Most of the Visigothic Kingdom was conquered by Umayyad troops from North Africa in 711 AD, with only the northern reaches of Hispania remaining in Christian hands. These gave birth to the medieval Kingdom of Asturias when a Visigothic nobleman called Pelagius was elected princeps by the Astures, of Celtic origin, who lived in the mountains, and by the Visigothic population, who had fled from the Muslims and took refuge in Asturias, where they joined Pelagius.

The Visigoths and their early kings were Arians and came into conflict with the Catholic Church, but after they converted to Nicene Christianity, the Church exerted an enormous influence on secular affairs through the Councils of Toledo. The Visigoths also developed the highly influential law code known in Western Europe as the Visigothic Code (Liber Iudiciorum), which would become the basis for Spanish law throughout the Middle Ages.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Visigothic_Kingdom

0 notes

Text

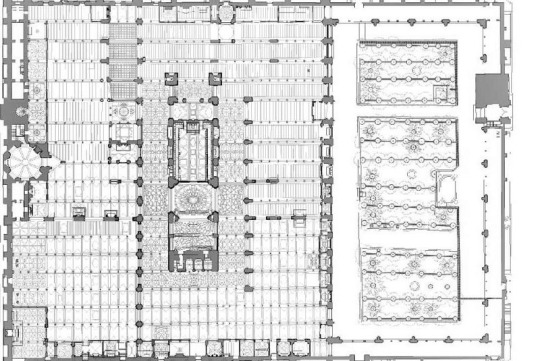

GREAT MOSQUE OF CORDOBA

The Great Mosque of Cordoba was begun by Abd al-Rahman I, the Umayyad emir of Al-Andalus, in AD 786. Prior to its construction, the Muslim conquerors of Cordoba had appropriated half of a Visigothic church for use as a mosque, leaving the local Christians in possession of the other half. The rapid growth of the Muslim community and the emir’s desire to assert his power and prestige through architectural patronage, however, quickly rendered that arrangement unsuitable. The church was therefore razed and a grand new mosque was built.

The mosque of Cordoba was modeled on the Great Mosque of Damascus, which had been built by the Umayyad caliphs in the 7th century. Through the replication of the patronage of his Syrian ancestors, Abd al-Rahman underscored to legitimacy of the new Umayyad regime in Spain.

A congregational mosque had to be large enough to accommodate the entire Muslim male population of the city for the obligatory recitation of Friday prayers (women were allowed, but not required to attend, Friday prayers). This weekly function took place in a large hypostyle prayer hall. During the rest of the week, the hall was used by smaller groups for prayers, as a schoolroom for the instruction of children, for lectures and sermons, and for the hearing of legal cases.

To meet these varied social and religious requirements, the architecture of the prayer hall usually consisted of large open space, free of fixed furnishings, covered by a timber roof supported by columns. The closely-placed columns of the hypostyle hall of the Great Mosque of Cordoba were spoliated from local Roman monuments. The innovative double arcade, which may have been based on multi-tiered Roman aqueducts, compensated for the relative shortness of the columns to raise the ceiling higher. The modularity of these architectural elements allowed for the easy and harmonious expansions of the hall, necessitated by population growth, in the 9th and 10th centuries. After the final, lateral expansion underaken by Al-Mansur, the hall comprised over 850 columns. The forest of columns of the hall was continued in by rows of orange and palm trees in the spacious courtyard. In the early 11th century, the Great Mosque of Cordoba covered 8,600 sq. meters.

In the 10th century, Abd al-Rahman III declared a new caliphate of Al-Andalus. To mark this occasion, he ordered the rebuilding and expansion of the mihrab—the niche indicating the qibla, or direction of Mecca—and masqura—the space in the hall immediately adjacent to the mirhab reserved for the ruler—and the construction of the mosque’s first minaret. The current mihrab and masqura were built by Al-Hakam II. Framed by a Moorish horse-shoe arch, the Cordoban mirhab is the largest in Spain. The decoration includes carved stucco, gilding, mosaic, and marble revetment. Koranic verses in kufic script appear on either side of the arch. The masqura is differentiated from the rest of the hall by interwoven multifoil arches with intricately-patterned voussoirs and by a series of ribbed domes. The mosaics of the domes were laid by Byzantine artisans sent to Cordoba by the emperor along with a gift of 1,600 kg of gold tesserae. The 47-meter minaret, from which the call to prayer was announced, was a symbol of the caliph’s power.

After the Christian reconquest of Cordoba , the mosque was coverted into a cathedral, with minimal changes made to the building fabric. The building was maintained by Muslim masons. In the early 16th century however, in an effort to impose the typology of a Christian basilica on to the mosque, a vaulted nave and transept of double the height were inserted into the center of the hall. Unlike earlier Christian alterations, which were carried out in the Mudéjar style, this obtrusive structure was executed in clashing late Gothic/early Renaissance styles. Approval for this project had been obtained from Emperor Charles V. The completed results, however, dismayed him, prompting his statement to the cathedral administration: “You have destroyed something unique to build something commonplace.” The baroque vaults of the transept and nave were completed in the 17th century.

The Great Mosque of Cordoba remains the cathedral of Cordoba to this day.

98 notes

·

View notes

Text

Greece: A historical essay - Part 2/4

ROMAN AND BYZANTINE GREECE:

It is often said that the Romans conquered Greece with might, but the Greeks conquered Rome with their culture. Much of Roman religion, mythology, alphabet, language, culture and philosophy were heavily based on Greek ideas and sometimes even outright taken and implemented with few differences.

In terms of Philosophy, the Roman period brings us the grand life practice of Stoicism, the advancement of Platonism and Aristotelianism, the mathematically-based philosophy of the Pythagoreans, and finally the rival of Stoic thought, Epicureanism. Platonism and Aristotelianism heavily influenced the later faiths of Christianity and Early Islam, Stoicism and Epicureanism were the main two philosophies of the educated and literate class in the late Roman Republic.

Rome itself is another large topic, so I will do my best to be brief here (although I could not help myself and included some of interesting, yet irrelevant, details).

Originally, Rome was a city-state of farmers who fought for the expansion of their civilization. Most of the early history we have of Rome is filled with righteous and defensive wars. in the absence of other, non-roman, sources, we have to take these claims with a grain of salt. But regardless of how the wars were started or who was at fault for them, we know that Rome expanded rapidly through Italy, uniting the peninsula, and then continuing into Southern France, Eastern Spain, and North Africa. At their height, they controlled all lands surrounding the Mediterranean, Babylon and most of Western Europe.

The basis and ideal of Roman society was the model of the citizen-farmer-soldier, this was referred to as “Romanitas” or “Roman-ness”. A Roman was expected to actively participate in the political life of the city (citizen), have a few acres of farmland and some cattle (farmer), to sustain their family and to maintain their weapons and armor in peacetime, so they’ll be ready to defend their country whenever it is threatened as a united army of levied militia (soldier).

Politically, The Romans were in a constant tug-of-war between aristocratic and republican governance. In the beginning of the Roman Republic, the wealthy patricians and, to a degree, the middle equestrian class, were the only people allowed in most government offices. After some years of vocal plebeian dissatisfaction with this state of affairs, the Plebs got their own office in the Tribune of the Plebs, soon after laws barring Plebeians from government offices were repealed and eventually they could hold most offices and legal privileges by class were mostly nullified. For a small number of years during the late Republican period, a silver lining was found. New problems appeared though and the Republic could not avoid being replaced by an empire. This situation lend itself to 2 broad political factions: The populists and the aristocrats.

With the Roman conquests of north Africa after the Punic wars, there was a great supply of slaves coming into Roman territories. The wealthy Romans used the absence of the soldiers from their farms to buy them out and expanded them through slave labor. Since slaves require no wages, these farms operated very cheaply and with great profit compared to the small farms of the soldier-farmers who were just returning home. Most were eventually outcompeted, had to sell their farms and flood to the city for urban work. The cities were not in a much better shape, slaves there would work in manufactories of sorts, creating urban goods at little expense. In the end, Roman citizens became a squalid underclass in the fringes of Roman society, dependent on the state or rich patronage for their sustenance and selling their only property, the vote, to the wealthy each election season.

The Populist Gracchi brothers, descendants of a rich plebeian family who had gotten into the Senate, pushed for reform, specifically land reform, in favor of these dispossessed roman citizens. The Oligarchic senators, in a paranoid frenzy, murdered both of them because of their fear that they had aspirations of becoming kings. Their laws were left unimplemented or outright repealed. The state of the common citizen did not improve.

The Late Roman Empire right before Caesar’s dictatorship.

Red: The empire’s extent at 68 B.C.

Yellow: Caesar’s conquests as military commander

Blue: Pompeii’s conquests

Green: Roman client states

Afterwards, there were the Marian reforms, named after the populist Gaius Marius, which turned the Roman army into a paid professional force and then the dictatorship of his enemy Sulla. Eventually we reach the age of Julius Caesar, who established a life-long dictatorship before being murdered, his successor, Octavian (Augustus), took over and formed the Roman Empire. Caesar’s solution to the state of the average citizen was to provide them the famous “Bread and Circuses”, he created and expanded the Roman welfare state in an effort to win over the people. While this program is often disliked as a dictatorial measure to pacify the masses, I believe it is important to judge it compared to the previous state of life. Despite that, it would still be appropriate to call it a band-aid solution at best.

Throughout all of these changes, Greeks remained mostly unaffected, only being involved in the wars, civil wars and one major failed revolt, where the Greek regions were devastated for a few years. The emperor Hadrian at one point went to Greece, where he had served as Archon of Athens before the start of his rule, and tried to organize the Greek cities into an autonomous Koinon (Commonwealth/League), which was not materialized de facto in any way unfortunately.

At this point in time, Christianity appears as a faith, first mentioned around 70 A.D., it spreads to many of the Eastern Roman provinces and Greeks are some of the first ethnic groups to convert to it, creating substantial Christian communities all over the mainland, its islands, the coasts of the Levant and Asia Minor. By the 4th century, Greece is almost completely Christianized.

The Roman empire was eventually split into two parts by Diocletian, in order to be more efficiently governed. This cut off the more wealthy eastern provinces from the western Empire, which was in great need of funds. The Western Roman empire was barely able to last 170 years after the split, whereas the East lasted, in one form or another, until the 15th century A.D.

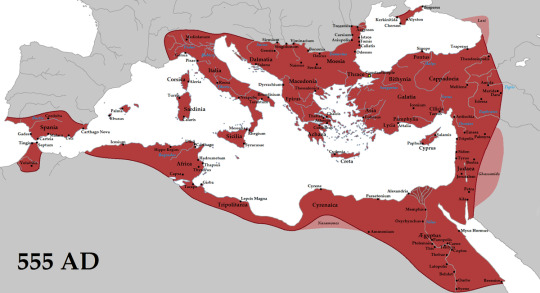

After the fall of the Western Roman Empire, we arrive at the Eastern Roman Empire, with its capital in Constantinople, where emperor Justinian takes the Throne in 527 A.D. He implements great legal and economic reforms, strengthens the army and sends it to many of the fallen parts of the former Western Roman empire to take them back. With his capable general Belisarius by his side, he conquers north-western Africa/former Carthage (modern-day Tunisia and north Algeria) from the Vandals, takes back Italy from the Ostrogoths and pushes the Visigoths of Spain to the interior, gaining back its south-eastern coast. These great conquests stretch the empire’s armies thin, greatly burden its economy and, combined with a devastating plague, lead to the rapid loss of all that land not even 50 years after it was attained.

Justinian’s Empire by 555 A.D.

This is often considered the beginning of the Byzantine Empire. With the loss of these territories, the empire is once again isolated mostly to the territories of the Greek population, with the only notable exceptions, Egypt and the Levant, being lost to the emerging Arab caliphate of the Rashidun and its new faith of Islam.

The Arabs would be the main enemies of the Hellenized Eastern Roman Empire until the arrival of the Turks in the late 11th century.

The Byzantine empire is considered to have become officially Greek with the reign of Heraclius (610 - 641 A.D.), who made Greek the official language of administration in the empire, abandoning Latin.

The powerhouse of the Byzantines was Asia-Minor for the most part and it was generally concentrated in Asia-Minor and Mainland Greece, occasionally ruling over most of the Balkans and parts of Syria but rarely having the strength to venture further.

Within the Byzantine Empire we get the formation of the Christian Orthodox dogma, traditions and structure. Even before the official split with the catholic church in 1054.

The Byzantine empire was legally an elective autocracy. The Emperor was viewed as a politically-neutral defender of justice and the Christian faith, the role was likened to the referee in a sporting event, handing warnings or punishment to bad actors and prizes to fair winners. The elective element came from the legal requirement that the successor to the emperor should be chosen through a vote of the senate, something which could be (and always was) bypassed by 2 methods: The emperor had the right to appoint a co-emperor/caesar/despot (the name of the title changed over time), who functioned as a vice-president of sorts, and that individual would become the emperor after the old Emperor’s death. So emperors chose their successors by handing them the office and made elections redundant. The other route was a palace coup or open rebellion. Byzantine politics were generally very cut-throat affairs and political ministers had to always watch their backs for rivals while also avoiding the emperor’s wrath.

In 1071, Byzantine forces are defeated at Manzikert by migratory Turks, who proceed to invade Asia Minor and conquer as far as the Aegean coast, the picture above shows the areas of control around 1081.

The Byzantine emperor Alexios I seeks aid from the Pope and Western Europe in beating back the Turks and Arabs, this call for help is utilized by the pope to start the first Crusade. The first few crusades help the Byzantines reconquer much of Asia Minor again, helping the “Komnenian restoration” period of Byzantium, even if they also lead to territorial disputes with the new Crusader states of the region.

Despite that, after only a few years Byzantium keeps declining territorially and is dealt a great blow during the 4th Crusade, which gets derailed by an exiled Emperor who promises great wealth to the Crusaders if they take Constantinople for him. long story short, they take it, he cannot pay them because the treasury is empty, they loot the city and divide the empire amongst themselves.

Some Greek Byzantine remnant states are created, with the most important among them being the Empire of Nicaea, the Despotate of Epirus and the Empire of Trebizond. These gradually kick the Latin states out of mainland Greece and Anatolia, until the empire is reunited by the Palaiologoi dynasty of the empire of Nicaea.

After some internal fracturing of their own, the Turks unite behind the relatively new Ottoman dynasty-state and start conquering the Greek mainland and Balkans during the 14th century, until finally taking the city of Constantinople itself in 1453. Ending Byzantium, the final remnant of the Roman empire.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

On this day: The Sack of Constantinople 1204, The Fourth Crusade damages Christendom and shapes history...

The Christian Crusades of the Middle Ages have a mixed legacy in the the long lens of history. In the modern age, they are reviled by some and still upheld as noble, even holy ventures by others. Depending on the particular Crusade the participants, their motivations and their outcome had varying degrees of impact long term. Perhaps none however had the long term ramifications, though unforeseen at the time of the Fourth Crusade of 1204.

The Fourth Crusade stands out because it saw not only the one time the Crusades were not directed at their original target of removing Muslim powers from the Holy Land in the Levant but instead changed their trajectory to attack a fellow Christian power, the Byzantine Empire or Eastern Roman Empire as it was known as or just Roman Empire. The Byzantine Empire was the successor to Rome, since it was the continuation of the ancient Roman Empire, albeit with its capital in Constantinople, straddling Europe and Asia between the Balkans and Anatolia between the Black and Mediterranean Seas. Overtime it had shifted its language and cultural focus from a Latin one to a Greek speaking one and a religious flavor of Christianity different from the Catholic Church of Western Europe, known as the Greek or Eastern Orthodox Church.

The Fourth Crusade came out a complex mix of ever present Byzantine internal politics and civil war, Western Crusader and Papal idealism and economic opportunism. As well as a mix of cultural and religious differences between the Western and Eastern branches of Christianity. To get a sense of how we get to the events of 1204 we need to look further back to an overview of the Byzantine Empire and the various threats they faced.

The Byzantine Empire was essentially an outgrowth of civil division within the ancient Roman Empire and the subsequent split lead to the founding a new capital in the east, by Roman Emperor Constantine, the first Roman Emperor to become nominally Christian. The city was named Constantinople though this was not initially Constantine’s planned name. It was located on the shores of the Bosporus, a channel that runs between the European continent and Asian Continent in modern day Turkey, where the Balkans and Anatolia meet. A literal crossroads of East meets West. It was located near the site of a former ancient Greek colony called Byzantium, hence the name later attached to describe the Eastern Roman Empire. The Byzantine Empire was name given centuries after its fall, it was only ever referred to by its inhabitants as the Roman Empire, because even though it evolved from Latin speaking Romans to Greek speakers, the political institutions remained very much influenced by the ancient Roman Empire and unlike the Western Roman Empire, it withstood the invasions of the various Germanic and other barbarian tribes in the 5th century and continued unbroken into the Middle Ages. The terms Byzantine Empire and Eastern Roman Empire, Roman Empire are used interchangeably hereafter in this post to mean the same polity.

The Byzantine Empire struggled as a bulwark against various barbarian tribes of differing origins over the centuries and increasingly it turned to its Christian religion as an inseparable component of its culture, which also took on a Greek flavor. The Greek language was the majority of the populace in this part of the world but the political and military elites spoke Latin until the 7th century, after which they too spoke Greek which developed from Koine Greek into Medieval Greek. Simultaneously there were serious differences between the religious authorities and the Emperors. While the Byzantine Empire did reclaim parts of Italy and Western Europe and North Africa, the differences between the Pope in Rome and religious authorities in Constantinople along with the Emperor himself was causing a rift between the East and Western Churches. As a result with these schisms lead to the development of the Eastern Orthodox Church separate from the Catholic or Roman Catholic Church. A particular break came when King of the Franks Charlemagne was crowned Holy Roman Emperor in the 9th century, giving rise to a new “claimant” to the Roman throne among the German speaking peoples of Central Europe who had also converted to Christianity. The Holy Roman Empire was never unified completely in the format of the Byzantine Empire, it was actually a collection of various kingdoms, fiefdoms and principalities among Central Europe, namely in the German, Italian, French speaking regions as well as the Low Countries. However, it too proclaimed itself the successor to the ancient Roman Empire, albeit its formation was really a form of political solidarity with the Roman Pope now at odds with the Roman Emperor in Constantinople, this lead to a break in relations between Rome and Constantinople that never really recovered completely.

In the 7th century a new threat, that of the Arabs and religion of Islam appeared on the Roman Empire’s southern borders in the Levant and North Africa. The Arabs surprisingly and quickly overran much of the Eastern Roman Empire. Taking the Levant including Syria and spreading to North Africa and eventually to Sicily, parts of Southern Italy and even the Iberian Peninsula then part of the Germanic Kingdom of the Visigoths in the coming generations. The Eastern Roman Empire was eventually able to stabilize parts of its eastern borders in Anatolia but had to withstand Arab invasions and even attempted sieges of Constantinople itself, but the city with its famously thick and high walls proved too much for the Arabs to defeat them. Additionally, they were helped by their sometimes rival the First Bulgarian Empire, a synthesis of Slavic tribes who migrated south in the 6th century from Eastern Europe along with the nomadic Turkic Bulgars who ruled over the area known as Bulgaria as the elite. Ultimately, the Islamic Caliphate which spread from Spain to the Middle East was divided by internal rivalries and new dynasties which lead to a fracturing within the Islamic world. This development provided some relief to the Byzantines as time went by, the Byzantines were able to regain parts of their strength in territories lost to the Arabs, at least partially.

The Byzantine Empire also dealt with the issue of various peoples from the north including the aforementioned Bulgarian Empire which originated with the Slavs intermingling with Byzantine citizens and later included the nomadic Turkic Bulgars. However, the Slavs south of the Danube River were the most populous group in this region and eventually the Bulgars were absorbed into their people which now called themselves Bulgarians. The Bulgarians however did adopt Christianity, namely the Orthodox branch of Christianity and spread this among their fellow South Slavs, this worked to occasionally smooth relations with the Byzantine Greeks but the rivalry remained both powers for control of the Balkans. Additionally, various other Turkic tribes and nomadic peoples over the years such as the Avars, Pechenegs, Cumans and Magyars (Hungarians) rode into the areas bordering the Byzantine Empire and variously they battled the Byzantines as well as each other. This was Constantinople’s preference, a paid for form of diplomacy, to play off the various barbarian peoples as soon as a new one showed up, the Byzantine Empire was immensely wealthy due to large amounts of gold, valuable trade routes and territories to tax. By paying off the latest arrivals, they could replace an older threat and work as vassals or allies of the Byzantine Empire at varying times.

Another, people the Byzantines had to deal with was the Kievan Rus, a combination of East Slavic tribes that due to internal strife supposedly invited a group of Vikings, known as Varangians to the Greeks to rule over them. The Vikings founded Kiev, the modern capital of Ukraine and ruled over as a political elite over these Eastern Slavs, in time they were absorbed into the Slavic majority like the Bulgars and their Slavic subjects. They formed a medieval state that served as the later basis for the modern states of Russia, Ukraine and Belarus and their Slavic peoples. The Kievan Rus, raided Byzantine lands including Constantinople but were repelled by the city’s famously impregnable walls and the secret weapon of the Byzantines, a Medieval take on the flamethrower known as Greek fire which destroyed the Rus’s navy. Greek fire’s exact method of deployment is a mystery but suffice to say it was a fearsome weapon that effectively repelled many an enemy. In time, the Rus too converted to Orthodox Christianity, becoming a sometimes ally of the Byzantines. They further assisted the Byzantines by sending Scandinavian mercenaries from Sweden, Denmark and Norway to Kiev and onto Constantinople to serve in the Byzantine army, first as mercenary infantry and later into a specialized elite personal guard of the Byzantine Emperors, the Varangian Guard which were quite fearsome in their reputation. This tradition would carry on for the remainder of the Byzantine Empire’s existence. Though the composition of the Varangian guard switched from Scandinavian Rus to Anglo-Saxons from England and others following the Norman Invasion of England.

The Normans, descendants of Viking raiders who pillaged France and were given their own duchy, Normandy, also spread to different parts of Europe. The Normans named after their Viking ancestors called the Norsemen or Northmen which became Norman. Developed their own distinct subculture of Viking influenced warfare, French dialect along with unique architecture and customs. The Normans most famously attacked and conquered England under William, Duke of Normandy or William the Conqueror. Ending Anglo-Saxon rule of England in 1066, the Normans formed a new political elite in the British Isles in union with Normandy. They also conquered Southern Italy, including Sicily, ending Arab/Islamic rule there and they attacked the Balkan possessions of the Byzantine Empire in raids. To varying degrees both sides were successful.

In the 11th century, the Byzantines can reconquered Bulgaria, ending a threat their but to the east were facing a new threat, the nomadic Turks coming from the steppes of Central Asia. The Turks had converted to Islam along with the Persians and other Iranian peoples of Central Asia and with this brought a renewed threat of Islam to the Roman Empire’s borders. In 1071, the Byzantine suffered a defeat at the Battle of Manzikert from the Seljuq Turks who established the Great Seljuq Empire, the first major nomadic Islamic Turkic Empire to threaten the Byzantines. They quickly settled into the Anatolian heartland of Byzantine lands replacing the previously Greek majority here. During the reign of Byzantine Emperor Alexios I Kommenos (1088-1118), the First Crusades were called by the Alexios working with then Pope Urban II in 1095. Promoting a reconciliation of sorts between East and West Christendom. The goal was to restore Anatolia and the Levant to the Byzantine Empire from the various Muslim rulers since the Seljuqs and their fellow Muslims in the Levant were divided. Eventually a mix of Italo-Norman, French and other Western European armies “took up the Cross” and became the Crusaders hell bent on Christian restoration of the Holy Land. The deal was they were to get help drive Muslims from these lands and restore Byzantine rule to them in exchange for spiritual clean slates from the Pope himself to satisfy their religious fervor and get monetary and military support from a reformed Byzantine army and navy that prior to Alexios had been neglected and underfunded due to corruption, civil war and decreased tax bases. The Crusaders had to swear and oath of nominal fealty to Alexios, even the Normans he previously fought. The First Crusade turned out to be successful though its intention of restoring lands to Byzantium only went so far. In Anatolia, the Crusaders with their heavy armor and weaponry decimated the light cavalry of the Turks and the Byzantines were able to partially restore control over Anatolia. In the Levant however, the Crusaders receiving limited support from the Byzantines decided to take matters into their own hands and create Crusader states in parts of modern Turkey, Syria, Lebanon, Israel and Jordan for themselves, even retaking Jerusalem. Forming the Counties of Tripoli and Edessa, the Princapality of Antioch and the Kingdom of Jerusalem, these states were nominally to become vassals of the Byzantine Empire since their Christian populace was majority Greek but they would be de-facto independent at varying times over the course of their existence.

As the 11th century gave way to the 12th century other Crusades were undertaken, the Second Crusade was more widespread trying to curtail Muslim reconquest of Anatolia and the Levant which resulted in a Crusader failure in Anatolia but a stalemate in the Levant preserving the Crusader states there. Meanwhile, Christians successfully retook the Muslim controlled parts of Portugal and Spain, known as Al-Andalus and the Crusaders in Northern Europe started to locally convert some Western Slavs who had long resisted conversion to Christianity to moderate levels of success. By the end of the 12th century, the Third Crusade was launched to revive the now reconquered parts of the Levant including Jerusalem that fell into Muslim hands of the Ayubid Sultanate, founded by an ethnic Kurd, named Saladin who became Sultan of Egypt and Syria and fought against Richard the Lionheart, King of England. The Crusaders regained partial control of the coastal regions of the Levant but not the interior and a truce was made between Richard and Saladin out of mutual respect and exhaustion.

The dawn of the 13th century saw Pope Innocent III, want to build on the successes of the Third Crusade and launch a Fourth Crusade to complete retaking Jerusalem once more. During the time of the Third Crusade though, tensions with the Byzantine Empire and Western Europeans resumed. Frederick I Barbarossa, Holy Roman Emperor and his army tried to get permission from the Byzantines to cross over into Anatolia but which was granted but saw an early end after Frederick drowned fording a river. The Germans were accused of conspiring with the resurgent Second Bulgarian Empire and Serbia both of which had broken away and reclaimed their independence from the Byzantines once more after a century and half of reconquest. Furthermore, the English took Cyprus from the Muslims but did not return to the Byzantines, instead handing it over to the Knights Templar, one of several Latin (Catholic) Christian military orders founded during the Crusades.

The Byzantines had for centuries been the most dominate city in Christendom in Constantinople, it was the largest and most cosmopolitan city in Europe reaching populations between 500,000-1,000,000 at its peak. It had long retained ancient Rome’s political machinations, as well as cultural innovations, public baths, forums, aqueducts, a racing arena for chariots and other classical Roman monuments and structures. It also housed ornate Christian churches such as the Hagia Sophia and with the Orthodox’s Church’s rich artwork of elaborate mosaics and golden icons it was awe-inspiring to anyone ,Christian or pagan who entered it’s triple set of walls for its sheer grandeur alone. A sense of bringing “Heaven on Earth” was something the Byzantines sought to do for any foreign dignitary.

The Byzantine capital was also the center of commerce in the Mediterranean, where east meets west. Its former vassal, the Italian city-state, the Republic of Venice had over the centuries become independent and became a commercial and naval power on its own and it had sought to become the Byzantine Empire’s biggest benefactor for trade. In time it sought to replace the Byzantine Empire as the commercial power of the region. The Venetians at first were granted favorable trade conditions which actually disadvantaged and further weakened the Byzantine economy and customs-tax revenues, this was the result of short-term convenience the Byzantine rulers often needed to lighten the burden on their treasury, making short term political gains at the expense of long term financial ruin. While Alexios I and his immediate descendants increased Byzantine rule and prestige over the course of the 12th century, they gradually fell back into civil war, corruption and sometimes downright oppressive violence to maintain order. Eventually they were replaced in a coup by the interrelated Angelos dynasty and reigned from 1185 until the events of 1204. Even within the dynasty there was infighting. Isaac II Angelos ruled for years, incompetently until replaced by his brother Alexios III Angelos who had Isaac, ritually blinded and sent into retirement was typical of Byzantine custom. His own reign was marred by financial mismanagement and corruption, outsourcing the navy to Venetian mercenaries and corrupt bureaucrats selling military and religious equipment to for personal gain. Once again the Byzantine Empire found itself virtually bankrupt and unable to pay its armies.

Alexios III was now being plotted against by his nephew Alexios, son of Isaac II. It was his nephew who escaped imprisonment and made his way to the Holy Roman Empire and into the court of his brother in law, the King of Germany Philip of Swabia who was married to Alexios’ sister Irene Angelina. Alexios would play a pivotal role in the events of 1204. Quite separate from his own plans, the Fourth Crusade was already being planned by Pope Innocent III with the typical goal of reclaiming Jerusalem in mind at the same time. The Venetian Republic agreed to provide the naval fleet and some ground support in exchange for a handsome sum from the mostly French and German Crusaders who were to partake in the voyage. The Crusaders were expected to pay the Venetians a large sum for their transport. In part, because the Venetians halted all other naval and commercial development for a year to build a sea worthy fleet with the expectation of being paid upon the Crusaders arrival in Venice which was expensive to a maritime power reliant on seafaring commerce. The Venetian head of state, known as the Doge was at this time a man nearly 100 years old and partially blinded by the Byzantines years before, by the name of Enrico Dandolo. Dandolo and the Venetians were surprised when the French and Germans showed up with limited funds. The Venetians had seemingly built a fleet a great personal expense and now could not expect a reimbursement. As a result the Venetians held the Crusaders hostage and demanded a negotiated payment from the Crusaders since it looked like the Crusade would no longer happen now. They received a partial payment, taking a collection from all the Crusaders but it was not enough to recoup their losses and so the stand off continued. At this point Dandolo proposed a new idea, the Venetians would partake in spoils of the Crusade, not part of the original agreement and the debt could be paid off. Additionally, Dandolo decided the Crusaders could work off their debt in part by helping Venice reclaim the Croatian city of Zara on the Adriatic Sea. This area nominally belonged to the Venetians but a group of Croatian pirates had taken over this port and disrupted Venetian commerce, if the city could be retaken with Crusader help, the Venetians would consider the debt partially restored. This had the added benefit of deescalating tensions with the Crusaders residing in Venice out of fear that their hostage ordeal may lead to violence there and at least in Croatia they could be placed elsewhere.

The planned attack on Zara reached the Pope who threatened excommunication of any Crusader French, German or Venetian or other Italian who attacked Zara since it was a fellow Christian city and already the Fourth Crusade’s purposes were being perverted. A papal sanctioned legate and entourage was sent to oversee the religious aspects of the Crusade and report back to the Pope. The Pope’s threats were intentionally withheld from the bulk of the Crusaders by the Venetians and some of the Crusader leaders who saw profiteering opportunities here. Though some Crusaders, devout in their religious convictions and sworn oaths refused to partake in an attack against fellow Christians the bulk of the army joined the Venetians in November of 1202, despite the Croats displaying the Cross as fellow Catholics, the city was taken after a few weeks. Immediately the Venetians and the Crusaders fought into a violent brawl leaving 100 dead as they disputed the spoils of the conquered city. The Pope receiving the news of the attack, excommunicated the entire army, though news of the excommunication was likewise withheld from the rank and file. However, the Pope would later grant an absolution to the army.

While wintering in the warmth of Croat coast, Alexios Angelos, who had escaped his uncle and reigning Byzantine Emperor, Alexios III to Germany made his way to Zara. He had been plotting to overthrow his uncle and take control of Byzantium for himself but in his exile abroad he needed a vehicle for his plans. The cousin of his brother in law, the German King happened to be the nominal leader of the Fourth Crusade, an Italian noble and soldier of German descent by the name and title of Boniface of Montferrat. Though by the Siege of Zara Boniface was merely a figurehead, the Venetian Doge Enrico Dandolo had more or less usurped the Crusade for his and Venice’s purposes. Nevertheless, Alexios hearing about the Crusader army, arrived at their winter camp in Zara and proposed a new alternative to their venture, instead of going to the Holy Land as planned why not detour to Constantinople and force his uncle give up the throne, in exchange Alexios would be proclaimed the new Emperor and pay off the Crusaders handsomely including the Venetians with promises to more than recoup the Venetians present losses. The timing and machinations of the various Crusaders, the Venetian Doge and the would be Byzantine pretender to the throne could not have been more perfect. Like the planned attack on Zara, Constantinople was a controversial target as a fellow Christian city, albeit one the Catholic or Latin Crusaders as they were known as, saw as still somewhat for their adherence to the Orthodox denomination which was alien and strange to the Catholics. Both denominations had sense of superiority to the other. The Doge was eager to gain riches from Constantinople to recoup his country’s losses and also to avenge an earlier massacre of Venetians and other of Italians in the Venetian Quarter of Constantinople years before by the Greek populace. Some Crusaders who were present at Zara but refused to partake in the attack, including the English noble Simon de Montfort refused to partake in the attack on Constantinople and left for the Kingdom on Hungary and eventually lead a small but unsuccessful contingent to the Holy Land, attempting to complete the original mission of the Crusade as intended.

Alexios additionally promised not only to pay off the Crusaders debts to the Venetians for the Crusade’s assistance in his coup but to resupply and reinforce the Crusade onto the Holy Land. Additionally, he promised to bring the Greek Orthodox Church (nominally subservient to the Emperor) under Papal authority. Unbeknownst to Alexios while his promises were too tempting to the Crusaders and Venetians, the practical reality of implementing them were beyond his reach. Doge Dandolo however, had spent time in Constantinople as a diplomat for Venice years before and was well aware of the complex and fluid politics of Byzantium and likely doubted the veracity of Alexios’s promises. Nevertheless by early 1203 the Crusader and Venetian flotilla were en-route to Constantinople. When Pope Innocent caught wind of this plot he warned against further attacks against Christian cities, at least nominally, but did not outright condemn this specific venture for reasons not exactly known, though probably for political reasons.

The Crusader-Venetian army arrived on the outskirts of Constantinople in June of 1203, having left Croatia in April. The city had a population of half a million and a permanent garrison of 15,000 regular troops, including 5,000 of the Varangian Guard. The sudden appearance of a fellow Christian army caught the city off guard and indeed the Byzantines could not call for reinforcements from other parts of the Empire in a timely manner. They sent an emissary to the Emperor Alexios III, stating the goals were to depose him peacefully if possible. Indeed that was the primary goal of the venture, depose Alexios III and replace him with his nephew and then be paid off rather handsomely before continuing onto the Holy Land as envisioned. The first fight between Byzantine troops and the Crusaders was an easy Crusader victory as heavily armored Frankish knights from France easy outperformed their Byzantine counterparts. Nevertheless, taking the city itself was going to be a daunting task and not something they initially thought who be necessary, though they came prepared just in case.

In July, the Crusaders began the siege proper by trying to cross the Bosporus and take the suburb Galata, the Crusaders would break into the sub channel of the Bosporus, known as the Golden Horn, which would allow the Venetian navy to park their fleet there and they could assault the sea walls of the city proper. Indeed, the Crusaders launched an amphibious landing onto Galata and took routed the Byzantine defenders, though a mercenary force of English, Danish and Italian troops held the strategic Tower of Galata. Eventually the tower fell and many attacks and bloody counterattacks. The Golden Horde itself was defending by a large chain but by taking Galata, the chain was cut and the Venetian fleet was allowed entry into the Golden Horn. At this point, Alexios Angelos was indeed paraded outside the city walls as if he were to be the Emperor, but to his and the Crusaders’ surprise they were jeered by the Greeks. Constantinople had been accustomed to coups and changing reigns in their emperors over the years and they cared little about the exiled prince or his blinded and retired father, they felt Alexios III was adequate as a ruler, he may not have been especially popular but he wasn’t so disliked that the city would depose him for his nephew, not at foreign coercion. This in turn soured the mood of the Crusaders and built resentment, thinking they would be hailed as liberators.

Now the assault on the city was absolutely necessary to achieve their goals, even if it was limited in scope. The Crusaders and Venetians made several attempts but were repulsed by the Byzantine troops. Though in July 11th, the Venetians captured some portions of the sea walls and towers before the Varangian Guard dispersed them, but the Venetians set off a fire to cover their retreat, this fire damaged a good portion of the city and left 20,000 people homeless. Finally, Alexios III personally lead a force to confront the Crusaders but before a fight could commence, he lost heart and retreated even though he outnumbered the Crusaders at that juncture. The fire and the disgraceful retreat prior to a right disheartened the city, Alexios III abandoned the city in disgrace, fearful of the implications of this, the city’s nobility actually brought back his deposed brother, the blinded former emperor, Isaac II out of retirement and declared him the Emperor once more in the hopes this would dissuade further conflict and allow them to save face.