#c: marcus steinberg

Text

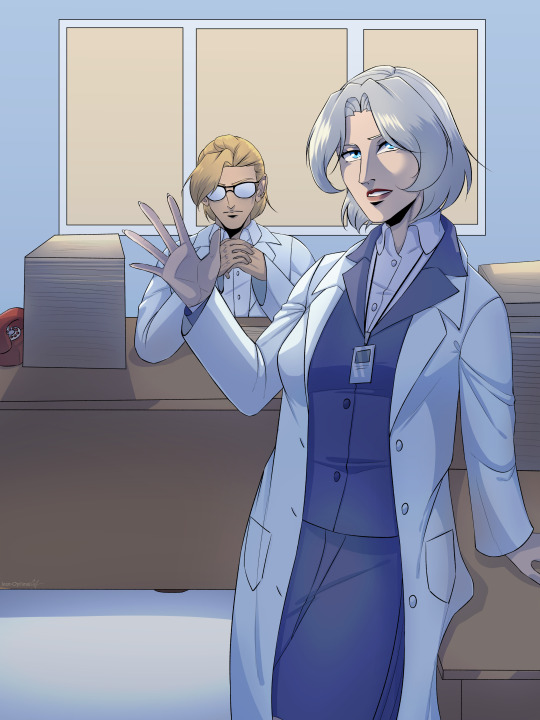

Я живое, но только наполовину. Сил на что-то новое пока нет, но есть работка, которую я тут не показывала. Мишель и Маркус на своем рабочем месте)

#art#fandom#fanart#illustration#fan character#fanfiction#miraculous fanart#miraculous ladybug#miraculous au#miraculous lb#miraculoustalesofladybugandcatnoir#c: michele lefort#c: marcus steinberg#laboratory#artists on tumblr

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Taking Notes

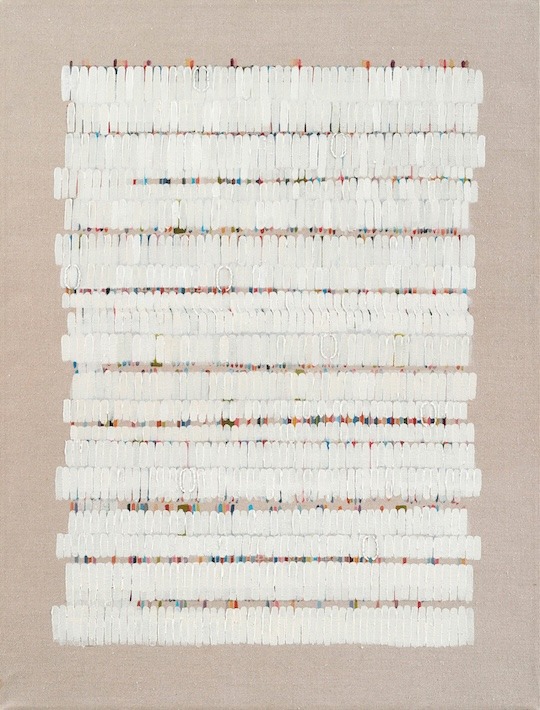

Kenneth Martin - Chance and Order

::

Claire-Louise Bennett - Checkout 19

::

Dieter Roth - bok 3a, 1961

::

Cy Twombly - Untitled

::

Raoul De Keyser - Poetry

::

Gail Tarantino - Oh, Hello

::

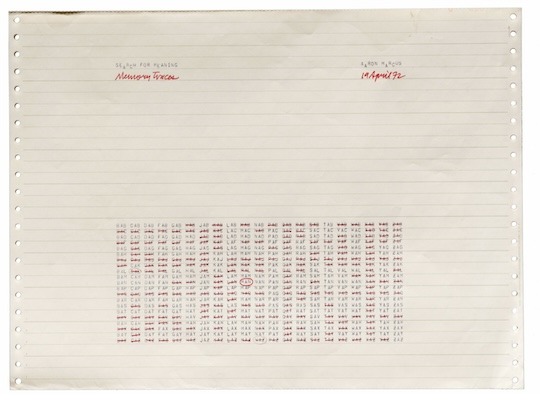

Aaron Marcus - Search For Meaning, 1972

::

Mary McDonnell - Untitled

::

Edward Hopper

::

Merce Cunningham - Notes for Roaratorio

::

Michael Krebber

::

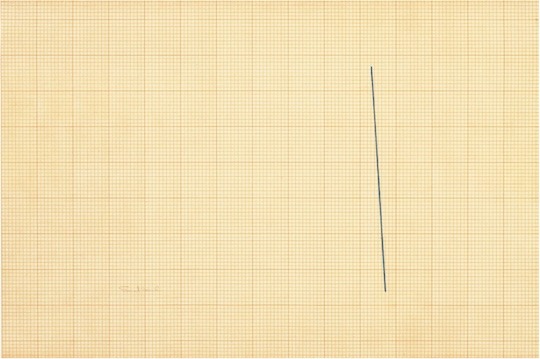

Fred Sandback - Untitled, 1973

::

Mark Rothko - Untitled, c. 1962

::

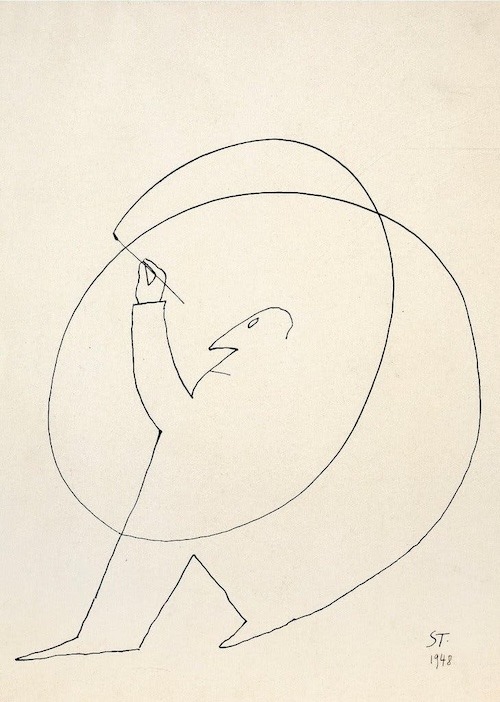

Saul Steinberg

::

unknown

::

El lissitzky - Pencil Study, 1920

::

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

by Roseann Cane

Information about the HAM4HAM Lottery

Yes: it’s every bit as good as you’ve heard.

There are many reasons why Hamilton has exceeded the ticket sales, awards, and critical acclaim of every previous Broadway show. It is unlike any musical that preceded it, combining a glorious mixture of music styles (hip hop, blues, soul, pop, jazz, and traditional show tunes). This narrative of the original immigrants to the U.S., our founding fathers and mothers, is played by a very contemporary American cast that is a glorious mixture of ethnicities, mostly non-white. Lin-Manuel Miranda has created a brilliantly sly commentary on today’s politics and racism by retelling America’s political history, the history of immigrants and outsiders.

The music is nonstop. There may be one or two spoken lines. The show is ruthlessly dynamic, moving through the story ever more quickly and thoroughly on designer David Korins’s grand, cavernous set with a revolving stage, within Howell Binkley’s dazzling light design. Andy Blankenbuehler’s choreography is as inventive and acrobatic as it is graceful, executed remarkably by the huge (and hugely talented) cast. Paul Tazewell’s costumes, authentically Colonial with an occasional soupcon of the surreal, are outstanding.

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

Visually and audibly electrifying as it is, I was caught unaware by Hamilton’s emotional impact. Alexander Hamilton (Edred Utomi), Eliza Hamilton (Hannah Cruz), Aaron Burr (Josh Tower), George Washington (Paul Oakley Stovall), Thomas Jefferson (Bryson Bruce, who also plays the Marquis de Lafayette), and King George (Peter Matthew Smith), among so many others, are fully realized characters, and while Hamilton is often hilarious, it is just as often heartwrenching. While engaging us fully in the triumphs and tragedies in individual lives, Miranda manages to simultaneously make us think about what or who, exactly, shapes national history. “Who lives, who dies, who tells your story?”

I was a bit disappointed in the acoustics: the orchestra at times seemed too loud, making it difficult to hear some lyrics. I’m not technically savvy enough to understand exactly why this happened, although I have experienced this problem before with musicals at Proctors. Perhaps some of the instrumentals are recorded rather than live, challenging the relationship between singer and orchestra. More’s the pity, because in my opinion, as remarkably good as the music is, Miranda’s way with words is phenomenal.

If it were possible, I’d seize the opportunity to see Hamilton again to try and catch the lyrics I missed, because yes, it’s every bit as good as you’ve heard.

Hamilton, book, music, and lyrics by Lin-Manuel Miranda (Inspired by the book Alexander Hamilton by Ron Chernow), directed by Thomas Kail, runs August 13-25, 2019 at Proctors Theatre, 432 State Street, Schenectady, NY. Choreography by Andy Blankenbuehler, music Supervision and orchestrations by Alex Lacamoire, scenic design by David Korins, costume design by Paul Tazewell, lighting design by Howell Binkley, sound design by Nevin Steinberg, hair and wig design by Charles G. LaPointe.

Information about tickets to Hamilton

Information about the HAM4HAM Lottery

CAST

REVIEW: “Hamilton” at Proctors by Roseann Cane Information about the HAM4HAM Lottery Yes: it’s every bit as good as you’ve heard.

#Alex Lacamoire#Andy Blankenbuehler#Bryson Bruce#C. Joan Marcus#Charles G. LaPointe#David Korins#Edred Utomi#Hamilton#Hannah Cruz#Howell Binkley#Josh Tower)#Lin-Manuel Miranda#Nevin Steinberg#Paul Oakley Stovall#Paul Tazewell#Peter Matthew Smith#Proctors#Proctors Theatre#Roseann Cane#Schenectady NY#Thomas Kail

0 notes

Text

Non-Extractive Architecture manifesto calls for buildings that are "not intrinsically dependent on exploitation"

Italian research studio Space Caviar has released a manifesto for a new type of architecture that does not deplete the earth's resources.

Called Non-Extractive Architecture, the manifesto calls on architects to design buildings that avoid exploiting the planet or people.

"Non-extractive architecture questions the assumption that building must inevitably cause some kind of irreversible damage or depletion somewhere - preferably somewhere else - and the best we can do as architects is limit the damage done," said Space Caviar co-founder Joseph Grima.

"Our goal as architects is not to limit carbon emissions," he added. "It is to come up with an idea of architecture that is not intrinsically dependent on some form of exploitation."

Top: the non-extractive architecture book. Above: Space Caviar co-founder Joseph Grima. Photo by Boudewijn Bollmann

The manifesto consists of a book and an exhibition, both titled Non-Extractive Architecture: On Designing Without Depletion.

The book was published by cultural foundation V–A–C and Steinberg Press last month while an exhibition on the same topic at V–A–C's Venetian headquarters was installed in March and will open when Covid regulations allow it to.

An exhibition was installed at V–A–C's Venetian headquarters in March. Photo by Marco Cappelletti

Running until January 2022, the exhibition will be a live research platform that will run alongside the Venice Architecture Biennale, which is due to open in May after being postponed from last year due to the pandemic.

"Both the project and the [exhibition] project are an attempt to question some of the assumptions underlying contemporary architectural production from a material and social perspective, and rethink the construction industry in the belief that better alternatives exist".

The exhibition will include the XYZ cargo publishing station by N55/Ion Sørvin and Till Wolfer. Photo by Marco Cappelletti

Taking place at V–A–C Zattere, a renovated palazzo on the Canale dell Giudecca, the project will generate research for a second book due to be published next year.

"At the most basic level, non-extractive architecture is an architecture that does not produce externalities," said Grima, who is also creative director at Design Academy Eindhoven and chief curator of design at Milan's Triennale di Milano museum as well as co-founder of Milanese design platform Alcova.

"The goal of the coming year of research and programs at V–A–C Zattere in Venice is to investigate the material, social and theoretical dimensions of this idea," Grima said.

Set to run until January 2022, the Venice show will include the XYZ cargo mobile library by N55/Ion Sørvin and Till Wolfer. Photo by Marco Cappelletti

Grima said that while ideas such as increasing energy efficiency of buildings, designing for reuse and reducing the carbon footprint of construction materials are important, "unless it is part of a larger strategy that has a clear goal there is a risk of it becoming little more than a damage-limitation exercise."

"Zero-carbon buildings aren't going to be much help, even if they're made out of carbon-capturing cross-laminated timber if their production is dependent on massive monocultural reforestation that depletes ecosystems or displaces communities and then needs to be hauled across continents by trucks that require massive infrastructural projects to make transportation cheap."

Grima added: "I think the long-term goals of the project are to propose an alternative model of what it means to be an architect, especially to young people getting into the profession now."

Based between Milan and London, Space Caviar is a research studio that explores architecture, technology, politics and the public realm. It was founded in 2013 by Grima and Tamar Shafrir.

Below is an interview with Grima about non-extractive architecture:

Marcus Fairs: What is non-extractive architecture?

Joseph Grima: At the most basic level, Non-extractive architecture is an architecture that does not produce externalities. In economics, externalities are costs that are imposed on a third party who did not agree to incur those costs. The most obvious example of an externality is pollution: if I drive from A to B by car, I pump a certain amount of NOx, CO2 and various other gases into the atmosphere. The benefit of travelling by car is mine alone, but the "cost" - in terms of the damage done - is equally shared by all of humanity, because CO2 doesn't much care about borders.

One of the key innovations of highly productive industrial economies was to become really effective at making their externalities invisible - relocating them somewhere beyond the horizon of perception of the societies or individuals benefiting from their productivity. And somewhere along the way, it somehow became accepted that there wasn't much choice: the price of modern civilisation was a certain amount of depletion and devastation, but as long as it was limited, and it happened somewhere else, the tradeoff was acceptable.

It's indisputable that technology and modernity have improved the quality of life for much of humanity, and that is true of the construction industry too. But the same construction industry is responsible for close to 40 per cent of carbon emissions, exploitative labour conditions, depletion of natural resources, and the irreversible transformation of landscapes and communities. Usually, most of this is completely invisible to those who benefit the most from it. Non-extractive architecture questions the basic assumption that this is unavoidable.

At a broader level, we believe that there can be no singular definition of Non-extractive architecture, and we realise it's an incredibly complex and nuanced question. The goal of the coming year of research and programs at V–A–C Zattere in Venice is to investigate the material, social and theoretical dimensions of this idea.

Marcus Fairs: The book comes across as a manifesto. Is that the intention?

Joseph Grima: I guess in some ways it is a manifesto. "Manifesto" is a word borrowed from Italian that literally means "billboard" or "placard", partly because manifestos have always referred to an open call to the person on the street or a broad appeal for support on a matter of vital collective importance.

We believe that the question of how we build, what we build, how we source our materials, what happens to them when a building is no longer needed, "who builds what and why" you could say, is just such a matter of vital significance. The kind of change we need, and which we advocate with Non-Extractive Architecture, is more cultural than technical.

It's an invitation to think about the long-term consequences of building, not just locally but in places usually far beyond the horizon where materials are sourced and where they'll end up. Or the consequences for individuals and communities whose labour is necessary to build in a certain way.

One of the ideas that drives this project is that in order to address the massive impact the construction industry has on the environment, the public's expectation of what architects do needs to be reframed, and this is where it's incredibly helpful and important to have the support and visibility an international foundation like V–A–C Zattere is able to offer. Specifically, it needs to be understood to stretch well beyond the currently accepted model which runs from strategic definition to handover.

So yes, I guess in a certain way this book is a manifesto, in that it attempts to bring together a wide spectrum of thought and practice, channelling the work of many others who are thinking along similar lines right now in many different fields (many of whom generously contributed to the first of the two volumes we will publish on this topic, which just came out).

As for the question of a movement, I personally prefer the idea of the network to movements - those tend to be rather dogmatic, which can lead to people feeling that they need to act as the gatekeepers of an orthodoxy. There is no orthodoxy here - our goal is not to prescribe the way things should be done.

Marcus Fairs: There are a lot of ideas circulating currently about how to lessen architecture's impact on the planet. How is non-extractive architecture different from them?

Joseph Grima: Because architecture and the construction industry are so carbon-intensive - by some measures they're estimated to account for some 40 per cent of total annual carbon emissions - there's naturally a huge amount of research going into making buildings more energy-efficient in order to cut down on emissions deriving from climate control, for example.

Others are looking into technical solutions for cutting down on emissions released by concrete as it sets. Others still are looking at "material passports" that track the full lifecycle of building components, or modular designs that allow them to be reused in other buildings once decommissioned.

All of this is incredibly important, but while each of these approaches is commendable and vital in its own way, unless it is part of a larger strategy that has a clear goal there is a risk of it becoming little more than a damage-limitation exercise. Non-extractive architecture questions the assumption that building must inevitably cause some kind of irreversible damage or depletion somewhere - preferably somewhere else - and the best we can do as architects is limit the damage done.

Zero-carbon buildings aren't going to be much help, even if they're made out of carbon-capturing cross-laminated timber, if their production is dependent on massive monocultural reforestation that depletes ecosystems or displaces communities, and then needs to be hauled across continents by trucks that require massive infrastructural projects to make transportation cheap.

Engineering for efficiency is crucial, reuse is crucial, reversibility is crucial, but unless they're all part of a strategic toolbox that operates at a much higher level - at least at an urban scale - and thinks much more ambitiously, they won't shift the needle enough.

What we're arguing is that our goal as architects is not to limit carbon emissions - it is to come up with an idea of architecture that is not intrinsically dependent on some form of exploitation (of resources, of people, of the future).

It's important to point out here that there is a broad field of contemporary discourse around the concepts of extraction and extractivity that analyse and define it at many different levels - not just material but also sociological, economic and geopolitical.

For example, one of the most extraordinary books I've read recently is Martin Arboleda's Planetary Mine: Territories of Extraction under Late Capitalism, which offers an incredible and unvarnished account of the violence of extractive practices and the ways in which mines in the Atacama Desert of Chile have become intermingled with an expanding constellation of megacities, ports, banks, and factories across East Asia and onwards towards Europe and elsewhere.

Marcus Fairs: Is the name "non-extractive architecture" and the concept new?

Joseph Grima: The idea of non-extractive architecture is absolutely not new, and it would be tempting to argue that it's always been there - there are plenty of studies into the ways in which vernacular traditions all over the world have evolved to establish a balance between the needs of a community and the equilibrium of the environment it is situated in.

In Non-Extractive Architecture: On Designing without Depletion vol. 1 there's a beautiful essay by Elsa Hoover, an amazing young Anishinaabe/Zhaaganaash architect, writer, and mapmaker who talks about architecture in terms of thousands of years of stewardship and the overlapping layers of land use, history, and governance that can be traced in the landscape around Lake Huron.

But it's important to point out that we're not advocating a return to past practices or the dimension of the vernacular. We live in a deeply technologically empowered society, and our tendency is to solve the problems we cause through bad planning and exploitative use of technology with more technology.

What we and many of the authors in this book advocate is not to step back from our identity as creatures of the post-atomic age, but to think harder and longer before resorting to technology. We might not need to adopt the specific techniques or practices of the Anishinaabe, for example, but there's a lot we could learn from their ability for long-term thinking and deep awareness of how their environment works.

Aside from that, there are many people doing amazing work that's very relevant at all sorts of levels, and which we plan to document extensively in volume 2 - from economists thinking about alternatives to GDP as a metric of prosperity, which is one of the root causes of a mindset of exploitation and waste, to companies developing 3D printers that can make buildings out of something as universally available as mud. We really see the idea of non-extractive architecture as an opportunity for exciting and ambitious new possibilities, rather than a form of renunciation.

On a more theoretical level, the project was at least in part inspired by the writing of Ivan Illich, who was a fierce advocate of the need to question modernity's pathological dependency on technology, and often argued that a more socially and environmentally equitable society could only be built if one is willing to start from first principles and embrace long-term thinking, rather that getting caught in the negative feedback loop of solving the problems caused by the thoughtless use of technology with more technology. In many, we try to intersect his ideas with one of the most technologically-driven thinkers of the 20th century, Buckminster Fuller, who was equally preoccupied with environmental issues but approached the problem from a diametrically opposite angle.

Marcus Fairs: Are there any contemporary practices or individuals doing work that could be described as non-extractive architecture?

Joseph Grima: As I mentioned before, we like to think about this project as an attempt to build a network of people, practices, companies, thinkers, activists, philosophers, designers and also members of the public who share the belief that architecture could and should liberate itself from its dependency on depletion in various forms. We don't see this so much as a standard or a badge to attach to a finished building, like Passivhaus for example - it's more an approach to design that attempts to acknowledge and pay attention to a number of things that are often not thought about.

So examples of what we might consider "non-extractive" range from the design philosophy of well-known studios like Lacaton & Vassal, who are in the press a lot these days as the recipients of this year's Pritzker prize awarded at least in part in recognition of their policy of designing only when strictly necessary and reusing whenever possible, all the way through to the work of groups such as Who Builds Your Architecture? (WBYA?), a coalition of architects, activists, scholars, and educators that examines the links between labour, architecture and the global networks that form around the industry of building buildings.

I guess our long-term goal is to build this network as a sort of repository of complementary ideas, none of which is in itself a silver bullet, but each of which can be part of the architect's toolkit as they attempt to make architecture slightly less damaging to the world around it.

Marcus Fairs: How did this project come about?

Joseph Grima: There's an amusing story told by Tim Ingold about how in his Ten Books on Architecture, Leon Battista Alberti defines the role of the architect by specifically pointing out that an architect is not a carpenter. Apparently, the reason this distinction is necessary is that in Alberti's day, carpenters had come to be known as architects due to a mistranslation in an ecclesiastical document of the year 945, in which the translator from Latin had mistaken the verb "architecture" for a compound of "arcus" (arch) and "tectum" (roof), jumping to the conclusion that an architect must be a specialist in the construction and repair of vaulted roofs.

In many ways, Alberti's urge to define the role of the architect by exclusion, by listing a series of activities they are not responsible for, is the beginning of a long trajectory of hyper-specialisation in which the purview of the architect gradually shrinks as the complexity of the final product increases.

I've personally always been fascinated by the idea of the architect as a full-spectrum designer who actually does know at least the basic principles of how to repair a roof, or pick good lumber, but is also capable of strategic thinking around multi-century material procurement strategies integrated into the urban landscape, or non-depletionary stewardship policies for production and reuse of buildings, and at the same time is driven by curiosity and the impetus to research and continually widen their horizon of knowledge.

Both Illich and Fuller were almost maniacally convinced of the need to de-specialise to survive, and this influenced the genesis of the project a lot. Non-extractive architecture is in many ways an invitation to zoom out and zoom in at the same time, and in any case to get away from screens a little more. This is something we attempt to practice ourselves at Space Caviar, where we always hang on to a certain hands-on engagement in all of our projects.

Marcus Fairs: What will happen at the Venice exhibition?

Joseph Grima: The project will be articulated through several parallel initiatives that will simultaneously activate V–A–C's Palazzo delle Zattere on multiple levels, transforming it into a research lab in which we will work together with resident researchers who we're recruiting through open calls. These parallel strands of research, residences, public programs, publishing and broadcasting will intertwine and overlap throughout the year, alternating levels of intensity, and will all be part of an exhibition that will take form and evolve over the course of the year.

We like to think of the palazzo as an open-door design studio, in which the public can enter and witness the research process firsthand (or rather, will be able to enter once the lockdown is lifted). The year's work will culminate in the publication of Non-Extractive Architecture Vol. 2, which will be focused on collecting and documenting case studies and the network of people around the world who are already working on these ideas.

Marcus Fairs: What are the long-term objectives?

Joseph Grima: I think the long-term goals of the project are to propose an alternative model of what it means to be an architect, especially to young people getting into the profession now. Architecture and design schools tend to be locked into a certain understanding of the architect's role in society and the heroic, modernist model they hold up as an example for young designers tends to be self-perpetuating, with consequences that are not always desirable (for society in general, but also for architects themselves).

Rather than addressing design challenges from a programmatic or compositional perspective, as schools tend to train students to, we want to start from the very end of the story: how can I solve this design problem in a way that will not simply shift the problem, perhaps in a different form, somewhere else?

It sounds simple, but in fact, it's incredibly difficult because much of the prosperity we have achieved as privileged Western societies is simply a function of externalities we've created elsewhere, usually in poorer countries further south. Unpicking the supply chains our daily lives depend on and rethinking these productive activities so they weigh on our own shoulders and not the shoulders of others is going to take a very long time - we literally have to unlearn what we've been taught and in some cases start over. This project will definitely evolve and take many different forms in the coming years, and it's an incredibly exciting challenge.

Non-Extractive Architecture will run at the V–A–C's Venetian headquarters until January 2021. For an up-to-date list of architecture and design events, visit Dezeen Events Guide.

The post Non-Extractive Architecture manifesto calls for buildings that are "not intrinsically dependent on exploitation" appeared first on Dezeen.

0 notes

Text

Bilderberg

Abrams, Stacey (USA), Founder and Chair, Fair Fight

Adonis, Andrew (GBR), Member, House of Lords

Albers, Isabel (BEL), Editorial Director, De Tijd / L'Echo

Altman, Roger C. (USA), Founder and Senior Chairman, Evercore

Arbour, Louise (CAN), Senior Counsel, Borden Ladner Gervais LLP

Arrimadas, Inés (ESP), Party Leader, Ciudadanos

Azoulay, Audrey (INT), Director-General, UNESCO

Baker, James H. (USA), Director, Office of Net Assessment, Office of the Secretary of Defense

Balta, Evren (TUR), Associate Professor of Political Science, Özyegin University

Barbizet, Patricia (FRA), Chairwoman and CEO, Temaris & Associés

Barbot, Estela (PRT), Member of the Board and Audit Committee, REN (Redes Energéticas Nacionais)

Barroso, José Manuel (PRT), Chairman, Goldman Sachs International; Former President, European Commission

Barton, Dominic (CAN), Senior Partner and former Global Managing Partner, McKinsey & Company

Beaune, Clément (FRA), Adviser Europe and G20, Office of the President of the Republic of France

Boos, Hans-Christian (DEU), CEO and Founder, Arago GmbH

Bostrom, Nick (GBR), Director, Future of Humanity Institute, Oxford University

Botín, Ana P. (ESP), Group Executive Chair, Banco Santander

Brandtzæg, Svein Richard (NOR), Chairman, Norwegian University of Science and Technology

Brende, Børge (NOR), President, World Economic Forum

Buberl, Thomas (FRA), CEO, AXA

Buitenweg, Kathalijne (NLD), MP, Green Party

Caine, Patrice (FRA), Chairman and CEO, Thales Group

Carney, Mark J. (GBR), Governor, Bank of England

Casado, Pablo (ESP), President, Partido Popular

Ceviköz, Ahmet Ünal (TUR), MP, Republican People's Party (CHP)

Cohen, Jared (USA), Founder and CEO, Jigsaw, Alphabet Inc.

Croiset van Uchelen, Arnold (NLD), Partner, Allen & Overy LLP

Daniels, Matthew (USA), New space and technology projects, Office of the Secretary of Defense

Demiralp, Selva (TUR), Professor of Economics, Koç University

Donohoe, Paschal (IRL), Minister for Finance, Public Expenditure and Reform

Döpfner, Mathias (DEU), Chairman and CEO, Axel Springer SE

Ellis, James O. (USA), Chairman, Users’ Advisory Group, National Space Council

Feltri, Stefano (ITA), Deputy Editor-in-Chief, Il Fatto Quotidiano

Ferguson, Niall (USA), Milbank Family Senior Fellow, Hoover Institution, Stanford University

Findsen, Lars (DNK), Director, Danish Defence Intelligence Service

Fleming, Jeremy (GBR), Director, British Government Communications Headquarters

Garton Ash, Timothy (GBR), Professor of European Studies, Oxford University

Gnodde, Richard J. (IRL), CEO, Goldman Sachs International

Godement, François (FRA), Senior Adviser for Asia, Institut Montaigne

Grant, Adam M. (USA), Saul P. Steinberg Professor of Management, The Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania

Gruber, Lilli (ITA), Editor-in-Chief and Anchor "Otto e mezzo", La7 TV

Hanappi-Egger, Edeltraud (AUT), Rector, Vienna University of Economics and Business

Hedegaard, Connie (DNK), Chair, KR Foundation; Former European Commissioner

Henry, Mary Kay (USA), International President, Service Employees International Union

Hirayama, Martina (CHE), State Secretary for Education, Research and Innovation

Hobson, Mellody (USA), President, Ariel Investments LLC

Hoffman, Reid (USA), Co-Founder, LinkedIn; Partner, Greylock Partners

Hoffmann, André (CHE), Vice-Chairman, Roche Holding Ltd.

Jordan, Jr., Vernon E. (USA), Senior Managing Director, Lazard Frères & Co. LLC

Jost, Sonja (DEU), CEO, DexLeChem

Kaag, Sigrid (NLD), Minister for Foreign Trade and Development Cooperation

Karp, Alex (USA), CEO, Palantir Technologies

Kerameus, Niki K. (GRC), MP; Partner, Kerameus & Partners

Kissinger, Henry A. (USA), Chairman, Kissinger Associates Inc.

Koç, Ömer (TUR), Chairman, Koç Holding A.S.

Kotkin, Stephen (USA), Professor in History and International Affairs, Princeton University

Krastev, Ivan (BUL), Chairman, Centre for Liberal Strategies

Kravis, Henry R. (USA), Co-Chairman and Co-CEO, Kohlberg Kravis Roberts & Co.

Kristersson, Ulf (SWE), Leader of the Moderate Party

Kudelski, André (CHE), Chairman and CEO, Kudelski Group

Kushner, Jared (USA), Senior Advisor to the President, The White House

Le Maire, Bruno (FRA), Minister of Finance

Leyen, Ursula von der (DEU), Federal Minster of Defence

Leysen, Thomas (BEL), Chairman, KBC Group and Umicore

Liikanen, Erkki (FIN), Chairman, IFRS Trustees; Helsinki Graduate School of Economics

Lund, Helge (GBR), Chairman, BP plc; Chairman, Novo Nordisk AS

Maurer, Ueli (CHE), President of the Swiss Federation and Federal Councillor of Finance

Mazur, Sara (SWE), Director, Investor AB

McArdle, Megan (USA), Columnist, The Washington Post

McCaskill, Claire (USA), Former Senator; Analyst, NBC News

Medina, Fernando (PRT), Mayor of Lisbon

Micklethwait, John (USA), Editor-in-Chief, Bloomberg LP

Minton Beddoes, Zanny (GBR), Editor-in-Chief, The Economist

Monzón, Javier (ESP), Chairman, PRISA

Mundie, Craig J. (USA), President, Mundie & Associates

Nadella, Satya (USA), CEO, Microsoft

Netherlands, His Majesty the King of the (NLD)

Nora, Dominique (FRA), Managing Editor, L'Obs

O'Leary, Michael (IRL), CEO, Ryanair D.A.C.

Pagoulatos, George (GRC), Vice-President of ELIAMEP, Professor; Athens University of Economics

Papalexopoulos, Dimitri (GRC), CEO, TITAN Cement Company S.A.

Petraeus, David H. (USA), Chairman, KKR Global Institute

Pienkowska, Jolanta (POL), Anchor woman, journalist

Pottinger, Matthew (USA), Senior Director, National Security Council

Pouyanné, Patrick (FRA), Chairman and CEO, Total S.A.

Ratas, Jüri (EST), Prime Minister

Renzi, Matteo (ITA), Former Prime Minister; Senator, Senate of the Italian Republic

Rockström, Johan (SWE), Director, Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research

Rubin, Robert E. (USA), Co-Chairman Emeritus, Council on Foreign Relations; Former Treasury Secretary

Rutte, Mark (NLD), Prime Minister

Sabia, Michael (CAN), President and CEO, Caisse de dépôt et placement du Québec

Sarts, Janis (INT), Director, NATO StratCom Centre of Excellence

Sawers, John (GBR), Executive Chairman, Newbridge Advisory

Schadlow, Nadia (USA), Senior Fellow, Hudson Institute

Schmidt, Eric E. (USA), Technical Advisor, Alphabet Inc.

Scholten, Rudolf (AUT), President, Bruno Kreisky Forum for International Dialogue

Seres, Silvija (NOR), Independent Investor

Shafik, Minouche (GBR), Director, The London School of Economics and Political Science

Sikorski, Radoslaw (POL), MP, European Parliament

Singer, Peter Warren (USA), Strategist, New America

Sitti, Metin (TUR), Professor, Koç University; Director, Max Planck Institute for Intelligent Systems

Snyder, Timothy (USA), Richard C. Levin Professor of History, Yale University

Solhjell, Bård Vegar (NOR), CEO, WWF - Norway

Stoltenberg, Jens (INT), Secretary General, NATO

Suleyman, Mustafa (GBR), Co-Founder, Deepmind

Supino, Pietro (CHE), Publisher and Chairman, Tamedia Group

Teuteberg, Linda (DEU), General Secretary, Free Democratic Party

Thiam, Tidjane (CHE), CEO, Credit Suisse Group AG

Thiel, Peter (USA), President, Thiel Capital

Trzaskowski, Rafal (POL), Mayor of Warsaw

Tucker, Mark (GBR), Group Chairman, HSBC Holding plc

Tugendhat, Tom (GBR), MP, Conservative Party

Turpin, Matthew (USA), Director for China, National Security Council

Uhl, Jessica (NLD), CFO and Exectuive Director, Royal Dutch Shell plc

Vestergaard Knudsen, Ulrik (DNK), Deputy Secretary-General, OECD

Walker, Darren (USA), President, Ford Foundation

Wallenberg, Marcus (SWE), Chairman, Skandinaviska Enskilda Banken AB

Wolf, Martin H. (GBR), Chief Economics Commentator, Financial Times

Zeiler, Gerhard (AUT), Chief Revenue Officer, WarnerMedia

Zetsche, Dieter (DEU), Former Chairman, Daimler AG

0 notes

Text

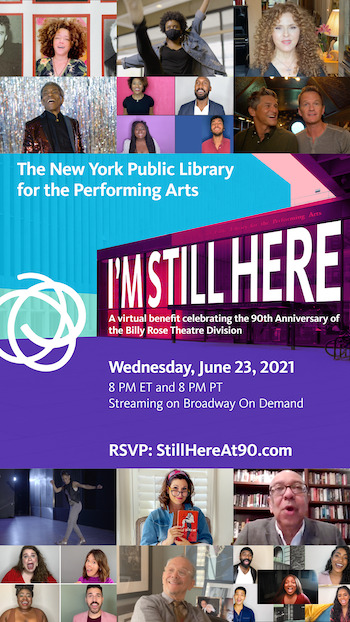

Jun. 23: Jason Robert Brown, Savion Glover, Priscilla López, Susan Stroman, Marisha Wallace, and Christopher Wheeldon Join I’M STILL HERE: A Virtual Benefit for the Billy Rose Theatre Division Honoring George C. Wolfe and the Late Harold Prince and Celebrating 90 Years of the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts; Tickets for the In-Person Viewing Party are Available Now

Jason Robert Brown, Savion Glover, Priscilla López, Susan Stroman, Marisha Wallace, and Christopher Wheeldon join the cavalcade of stars participating in The New York Public Library for the Performing Arts’ I’m Still Here: A Virtual Benefit for the Billy Rose Theatre Division, airing June 23, 2021 on Broadway On Demand at 8pm EST and 8pm PST. The fundraiser will help raise critical funds for the Library for the Performing Arts’ beloved Theatre Division as it celebrates its 90th anniversary this year.

Tickets to the online fundraiser will be donate-what-you-can, with a recommendation of at least $19.31 in honor of the year the division was founded. To purchase tickets to the one-time-only virtual event, visit StillHereAt90.com.

An in-person viewing party at the Library for the Performing Arts in Lincoln Center for donors has also just been announced, including a pre-screening reception and performance featuring Pulitzer Prize winner Michael R. Jackson (A Strange Loop), and GRAMMY and two-time Tony Award winner Duncan Sheik (Spring Awakening). For details and ticket prices for this limited capacity in- person event, please contact [email protected].

An incredibly special aspect of I’m Still Here is that it will feature clips of Broadway productions from the Theatre Division’s Theatre on Film and Tape Archive (TOFT), shown especially for this occasion with special permission from The Coalition of Broadway Unions and Guilds and the respective talent, creative teams and rights holders of each production. These archival recordings are typically only available to view onsite at the Library for the Performing Arts. The recordings shown will include the original Broadway cast of In the Heights; Angela Bassett and Samuel L. Jackson in The Mountaintop; Brian Stokes Mitchell in Ragtime; Glenn Close in Sunset Boulevard; Kelli O’Hara and Paulo Szot in South Pacific; Craig Bierko and Rebecca Luker in The Music Man; Meryl Streep, Marcia Gay Harden and Larry Pine in The Seagull; Savion Glover, Jimmy Tate, Choclattjared and Raymond King in Bring in ‘da Noise, Bring in ‘da Funk; Bette Midler in I’ll Eat You Last; Christian Borle and Tim Curry in Spamalot; and more.

I’m Still Here will also include interviews with Broadway legends and emerging creatives; and reconceived performances of musical theatre songs, including Stephanie J. Block performing “A Trip to the Library,” André De Shields performing “I’m Still Here,” original Company cast members from 1970-to-present performing “Another Hundred People,” “Wheels of a Dream,” “Love Will Find a Way,” and more. The evening’s honorees are Harold Prince and George C. Wolfe.

Featuring new performances and appearances by Troy Anthony (The River Is Me), Annaleigh Ashford (Sunday in the Park with George), Major Attaway (Aladdin), Alexander Bello (Caroline, or Change), Laura Benanti (She Loves Me), Malik Bilbrew, Susan Birkenhead (Jelly’s Last Jam), Shay Bland, Stephanie J. Block (The Cher Show), Alex Brightman (Beetlejuice), Matthew Broderick (Plaza Suite), Jason Robert Brown (The Last 5 Years), Krystal Joy Brown (Hamilton), David Burtka (“A Series of Unfortunate Events”), Sammi Cannold (Endlings), Ayodele Casel (Chasing Magic), Kirsten Childs (Bella), Antonio Cipriano (Mean Girls), Victoria Clark (The Light in the Piazza), Max Clayton (Moulin Rouge!), Calvin L. Cooper (Mrs. Doubtfire), Trip Cullman (Choir Boy), Taeler Elyse Cyrus (Hello, Dolly!), Quentin Earl Darrington (Once on This Island), André De Shields (Hadestown), Frank DiLella (NY1), Derek Ege, Amina Faye, Harvey Fierstein (La Cage aux Folles), Leslie Donna Flesner (Tootsie), Chelsea P. Freeman, Savion Glover (Bring in ‘da Noise, Bring in ‘da Funk), Joel Grey (Cabaret), Ryan J. Haddad (“The Politician”),James Harkness (Ain’t Too Proud), Sheldon Harnick (Fiddler on the Roof), Marcy Harriell (Company), Mark Harris (“Mike Nichols: A Life”), Neil Patrick Harris (Hedwig and the Angry Inch), David Henry Hwang (M. Butterfly), Arica Jackson (Caroline, or Change), Michael R. Jackson (A Strange Loop), Cassondra James (Once on This Island), Marcus Paul James (Rent), Taylor Iman Jones (Hamilton), Maya Kazzaz, Tom Kirdahy (The Inheritance), Leslie Kritzer (Beetlejuice), Michael John LaChiusa (The Wild Party), Norman Lear (Good Times), Baayork Lee (A Chorus Line), L. Morgan Lee (A Strange Loop), Robert Lee (Takeaway), Sondra Lee (Hello, Dolly!), Telly Leung (Aladdin), Priscilla Lopez (A Chorus Line),Ashley Loren (Moulin Rouge!), Allen René Louis (“Jimmy Kimmel Live!”), Brittney Mack (Six), Morgan Marcell (Hamilton), Aaron Marcellus (“American Idol”), Joan Marcus, Michael Mayer (Spring Awakening), Annie McGreevey (Company), Sarah Meahl (Kiss Me, Kate), Joanna Merlin (Fiddler on the Roof), Ruthie Ann Miles (Sunday in the Park with George), Bonnie Milligan (Head Over Heels), Rita Moreno (West Side Story), Madeline Myers (Double Helix), Pamela Myers (Company),Leilani Patao (Garden Girl), Nova Payton (Dreamgirls), Joel Perez (Kiss My Aztec), Bernadette Peters (Into the Woods), Tonya Pinkins (Jelly’s Last Jam), Jacoby Pruitt, Sam Quinn, Phylicia Rashad (A Raisin in the Sun), Jelani Remy (Ain’t Too Proud), George Salazar (Be More Chill), Marilyn Saunders (Company), Marcus Scott (Fidelio), Rashidra Scott (Company), Rona Siddiqui (Tales of a Halfghan), Ahmad Simmons (West Side Story), Susan Stroman (The Producers), Rebecca Taichman (Indecent), Jeanine Tesori (Fun Home), Bobby Conte Thornton (Company), Sergio Trujillo (On Your Feet), Kei Tsuruharatani (Jagged Little Pill), Ben Vereen (Pippin), Jack Viertel, Christopher Vo (The Cher Show), Nik Walker (Ain’t Too Proud), Marisha Wallace (Dreamgirls), Shannon Fiona Weir, Christopher Wheeldon (MJ: The Musical),Helen Marla White (Ain’t Misbehavin’), Natasha Yvette Williams (“Orange is the New Black”), and Kumiko Yoshii (Prince of Broadway).

Click here to watch New York Public Library’s Doug Reside on Backstage LIVE with Richard Ridge.

The virtual benefit is produced and conceived by co-founder of the upcoming Museum of Broadway and four-time Tony nominee Julie Boardman (Company) and Co-Executive Producer of Broadway For Biden Nolan Doran (Head Over Heels), featuring direction by Steve Broadnax (Thoughts Of A Colored Man), Sammi Cannold (Endlings), Nick Corley (Plaza Suite), GRAMMY Award Winner Ty Defoe (Straight White Men), Drama Desk winner Lorin Latarro (Waitress), Mia Walker (Jagged Little Pill) and Tony Award winnerJason Michael Webb (Choir Boy), choreography by Ayodele Casel (Chasing Magic),Lorin Latarro and Ray Mercer (The Lion King), with new music arranged by ASCAP Award winner Rachel Dean (Medusa) and Annastasia Victory (A Wonderful World), with arrangements and orchestrations by Brian Usifer (Frozen). Casting is by Peter Van Dam at Tara Rubin Casting.

Tony Marx is the president of The New York Public Library, William Kelly is the Andrew W. Mellon Director of the Research Libraries,Jennifer Schantz is the Barbara G. and Lawrence A. Fleischman Executive Director of the Library for the Performing Arts, and Doug Reside is the Lewis and Dorothy Cullman Curator of the Billy Rose Theatre Division. Patrick Hoffman is the curator of the Theatre on Film and Tape Archive. Henry Tisch serves as Associate Producer and Travis Waldschmidt is Associate Choreographer. Animation and Motion Graphics by Kate Freer, Graphic Design by Caitlin Whittington, Sean MacLaughlin is Director of Photography and Ian Johnston is B Camera Operator. Dylan Tashjian is Onsite Coordinator with COVID compliance by Lauren Class Schneider.

HOST COMMITTEE: Ted & Mary Jo Shen, Barbara Fleischman, Agnes Gund, Fiona & Eric Rudin, Lizzie & Jon Tisch, Kate Cannova, Joan Marcus, Daisy Prince, Gayfryd Steinberg, Van Horn Group

LIBRARY FOR THE PERFORMING ARTS THEATRE COMMITTEE: Emily Altman, Margot Astrachan, Ken Billington, Julie Boardman, Ted Chapin, Bonnie Comley, Van Dean, Kurt Deutsch, Scott Farthing, Barbara Fleischman, Freddie Gershon, Louise Hirschfeld, Joan Marcus, Elliott Masie, Arthur Pober, Ed Schloss, Morwin Schmookler, Jenna Segal, Ted Shen, Kara Unterberg, Abbie Van Nostrand, Kumiko Yoshii

THE NEW YORK PUBLIC LIBRARY FOR THE PERFORMING ARTS DOROTHY AND LEWIS B. CULLMAN CENTER houses one of the world’s most extensive combinations of circulating, reference, and rare archival collections in the field of dance, theatre, music and recorded sound. These materials are available free of charge, along with a wide range of special programs, including exhibitions, seminars, and performances. An essential resource for everyone with an interest in the arts — whether professional or amateur — the Library is known particularly for its prodigious collections of non-book materials such as historic recordings, videotapes, autograph manuscripts, correspondence, sheet music, stage designs, press clippings, programs, posters and photographs. The Library is part of The New York Public Library system, which has locations in the Bronx, Manhattan and Staten Island, and is a lead provider of free education for all.

BROADWAY ON DEMAND is the industry-leading livestream platform housing performance & theatre education programming, & the preferred choice of top Broadway artists, producers, educators & professionals. Broadway On Demand has streamed 2,500 events & live productions—from Broadway shows to concert series, performance venues to individual artists, & original content—in 82 countries to over 300,000 viewers. Thanks to a unique licensing interface, ShowShare, approved middle school, high school, college, community & professional theatre productions utilize the platform to stream to their audiences. Broadway on Demand is available on the web, mobile, Apple and Android app store, AppleTV, Roku, Chromecast, and Amazon Fire TV. For access to the complete and ever-expanding Broadway on Demand library, subscribe at BroadwayOnDemand.com.

youtube

#NYPL#new york public library#New York Public Library for the Performing Arts#Billy Rose Theatre Division#Marcus Scott#MarcusScott#WriteMarcus#Write Marcus#THE NEW YORK PUBLIC LIBRARY FOR THE PERFORMING ARTS DOROTHY AND LEWIS B. CULLMAN CENTER#George C. Wolfe#Harold Prince#theatre#theater#musical theater#musical theatre

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Non-Extractive Architecture manifesto calls for buildings that are "not intrinsically dependent on exploitation"

Italian research studio Space Caviar has released a manifesto for a new type of architecture that does not deplete the earth's resources.

Called Non-Extractive Architecture, the manifesto calls on architects to design buildings that avoid exploiting the planet or people.

"Non-extractive architecture questions the assumption that building must inevitably cause some kind of irreversible damage or depletion somewhere - preferably somewhere else - and the best we can do as architects is limit the damage done," said Space Caviar co-founder Joseph Grima.

"Our goal as architects is not to limit carbon emissions," he added. "It is to come up with an idea of architecture that is not intrinsically dependent on some form of exploitation."

Top: the non-extractive architecture book. Above: Space Caviar co-founder Joseph Grima. Photo by Boudewijn Bollmann

The manifesto consists of a book and an exhibition, both titled Non-Extractive Architecture: On Designing Without Depletion.

The book was published by cultural foundation V–A–C and Steinberg Press last month while an exhibition on the same topic at V–A–C's Venetian headquarters was installed in March and will open when Covid regulations allow it to.

An exhibition was installed at V–A–C's Venetian headquarters in March. Photo by Marco Cappelletti

Running until January 2022, the exhibition will be a live research platform that will run alongside the Venice Architecture Biennale, which is due to open in May after being postponed from last year due to the pandemic.

"Both the project and the [exhibition] project are an attempt to question some of the assumptions underlying contemporary architectural production from a material and social perspective, and rethink the construction industry in the belief that better alternatives exist".

The exhibition will include the XYZ cargo publishing station by N55/Ion Sørvin and Till Wolfer. Photo by Marco Cappelletti

Taking place at V–A–C Zattere, a renovated palazzo on the Canale dell Giudecca, the project will generate research for a second book due to be published next year.

"At the most basic level, non-extractive architecture is an architecture that does not produce externalities," said Grima, who is also creative director at Design Academy Eindhoven and chief curator of design at Milan's Triennale di Milano museum as well as co-founder of Milanese design platform Alcova.

"The goal of the coming year of research and programs at V–A–C Zattere in Venice is to investigate the material, social and theoretical dimensions of this idea," Grima said.

Set to run until January 2022, the Venice show will include the XYZ cargo mobile library by N55/Ion Sørvin and Till Wolfer. Photo by Marco Cappelletti

Grima said that while ideas such as increasing energy efficiency of buildings, designing for reuse and reducing the carbon footprint of construction materials are important, "unless it is part of a larger strategy that has a clear goal there is a risk of it becoming little more than a damage-limitation exercise."

"Zero-carbon buildings aren't going to be much help, even if they're made out of carbon-capturing cross-laminated timber if their production is dependent on massive monocultural reforestation that depletes ecosystems or displaces communities and then needs to be hauled across continents by trucks that require massive infrastructural projects to make transportation cheap."

Grima added: "I think the long-term goals of the project are to propose an alternative model of what it means to be an architect, especially to young people getting into the profession now."

Based between Milan and London, Space Caviar is a research studio that explores architecture, technology, politics and the public realm. It was founded in 2013 by Grima and Tamar Shafrir.

Below is an interview with Grima about non-extractive architecture:

Marcus Fairs: What is non-extractive architecture?

Joseph Grima: At the most basic level, Non-extractive architecture is an architecture that does not produce externalities. In economics, externalities are costs that are imposed on a third party who did not agree to incur those costs. The most obvious example of an externality is pollution: if I drive from A to B by car, I pump a certain amount of NOx, CO2 and various other gases into the atmosphere. The benefit of travelling by car is mine alone, but the "cost" - in terms of the damage done - is equally shared by all of humanity, because CO2 doesn't much care about borders.

One of the key innovations of highly productive industrial economies was to become really effective at making their externalities invisible - relocating them somewhere beyond the horizon of perception of the societies or individuals benefiting from their productivity. And somewhere along the way, it somehow became accepted that there wasn't much choice: the price of modern civilisation was a certain amount of depletion and devastation, but as long as it was limited, and it happened somewhere else, the tradeoff was acceptable.

It's indisputable that technology and modernity have improved the quality of life for much of humanity, and that is true of the construction industry too. But the same construction industry is responsible for close to 40 per cent of carbon emissions, exploitative labour conditions, depletion of natural resources, and the irreversible transformation of landscapes and communities. Usually, most of this is completely invisible to those who benefit the most from it. Non-extractive architecture questions the basic assumption that this is unavoidable.

At a broader level, we believe that there can be no singular definition of Non-extractive architecture, and we realise it's an incredibly complex and nuanced question. The goal of the coming year of research and programs at V–A–C Zattere in Venice is to investigate the material, social and theoretical dimensions of this idea.

Marcus Fairs: The book comes across as a manifesto. Is that the intention?

Joseph Grima: I guess in some ways it is a manifesto. "Manifesto" is a word borrowed from Italian that literally means "billboard" or "placard", partly because manifestos have always referred to an open call to the person on the street or a broad appeal for support on a matter of vital collective importance.

We believe that the question of how we build, what we build, how we source our materials, what happens to them when a building is no longer needed, "who builds what and why" you could say, is just such a matter of vital significance. The kind of change we need, and which we advocate with Non-Extractive Architecture, is more cultural than technical.

It's an invitation to think about the long-term consequences of building, not just locally but in places usually far beyond the horizon where materials are sourced and where they'll end up. Or the consequences for individuals and communities whose labour is necessary to build in a certain way.

One of the ideas that drives this project is that in order to address the massive impact the construction industry has on the environment, the public's expectation of what architects do needs to be reframed, and this is where it's incredibly helpful and important to have the support and visibility an international foundation like V–A–C Zattere is able to offer. Specifically, it needs to be understood to stretch well beyond the currently accepted model which runs from strategic definition to handover.

So yes, I guess in a certain way this book is a manifesto, in that it attempts to bring together a wide spectrum of thought and practice, channelling the work of many others who are thinking along similar lines right now in many different fields (many of whom generously contributed to the first of the two volumes we will publish on this topic, which just came out).

As for the question of a movement, I personally prefer the idea of the network to movements - those tend to be rather dogmatic, which can lead to people feeling that they need to act as the gatekeepers of an orthodoxy. There is no orthodoxy here - our goal is not to prescribe the way things should be done.

Marcus Fairs: There are a lot of ideas circulating currently about how to lessen architecture's impact on the planet. How is non-extractive architecture different from them?

Joseph Grima: Because architecture and the construction industry are so carbon-intensive - by some measures they're estimated to account for some 40 per cent of total annual carbon emissions - there's naturally a huge amount of research going into making buildings more energy-efficient in order to cut down on emissions deriving from climate control, for example.

Others are looking into technical solutions for cutting down on emissions released by concrete as it sets. Others still are looking at "material passports" that track the full lifecycle of building components, or modular designs that allow them to be reused in other buildings once decommissioned.

All of this is incredibly important, but while each of these approaches is commendable and vital in its own way, unless it is part of a larger strategy that has a clear goal there is a risk of it becoming little more than a damage-limitation exercise. Non-extractive architecture questions the assumption that building must inevitably cause some kind of irreversible damage or depletion somewhere - preferably somewhere else - and the best we can do as architects is limit the damage done.

Zero-carbon buildings aren't going to be much help, even if they're made out of carbon-capturing cross-laminated timber, if their production is dependent on massive monocultural reforestation that depletes ecosystems or displaces communities, and then needs to be hauled across continents by trucks that require massive infrastructural projects to make transportation cheap.

Engineering for efficiency is crucial, reuse is crucial, reversibility is crucial, but unless they're all part of a strategic toolbox that operates at a much higher level - at least at an urban scale - and thinks much more ambitiously, they won't shift the needle enough.

What we're arguing is that our goal as architects is not to limit carbon emissions - it is to come up with an idea of architecture that is not intrinsically dependent on some form of exploitation (of resources, of people, of the future).

It's important to point out here that there is a broad field of contemporary discourse around the concepts of extraction and extractivity that analyse and define it at many different levels - not just material but also sociological, economic and geopolitical.

For example, one of the most extraordinary books I've read recently is Martin Arboleda's Planetary Mine: Territories of Extraction under Late Capitalism, which offers an incredible and unvarnished account of the violence of extractive practices and the ways in which mines in the Atacama Desert of Chile have become intermingled with an expanding constellation of megacities, ports, banks, and factories across East Asia and onwards towards Europe and elsewhere.

Marcus Fairs: Is the name "non-extractive architecture" and the concept new?

Joseph Grima: The idea of non-extractive architecture is absolutely not new, and it would be tempting to argue that it's always been there - there are plenty of studies into the ways in which vernacular traditions all over the world have evolved to establish a balance between the needs of a community and the equilibrium of the environment it is situated in.

In Non-Extractive Architecture: On Designing without Depletion vol. 1 there's a beautiful essay by Elsa Hoover, an amazing young Anishinaabe/Zhaaganaash architect, writer, and mapmaker who talks about architecture in terms of thousands of years of stewardship and the overlapping layers of land use, history, and governance that can be traced in the landscape around Lake Huron.

But it's important to point out that we're not advocating a return to past practices or the dimension of the vernacular. We live in a deeply technologically empowered society, and our tendency is to solve the problems we cause through bad planning and exploitative use of technology with more technology.

What we and many of the authors in this book advocate is not to step back from our identity as creatures of the post-atomic age, but to think harder and longer before resorting to technology. We might not need to adopt the specific techniques or practices of the Anishinaabe, for example, but there's a lot we could learn from their ability for long-term thinking and deep awareness of how their environment works.

Aside from that, there are many people doing amazing work that's very relevant at all sorts of levels, and which we plan to document extensively in volume 2 - from economists thinking about alternatives to GDP as a metric of prosperity, which is one of the root causes of a mindset of exploitation and waste, to companies developing 3D printers that can make buildings out of something as universally available as mud. We really see the idea of non-extractive architecture as an opportunity for exciting and ambitious new possibilities, rather than a form of renunciation.

On a more theoretical level, the project was at least in part inspired by the writing of Ivan Illich, who was a fierce advocate of the need to question modernity's pathological dependency on technology, and often argued that a more socially and environmentally equitable society could only be built if one is willing to start from first principles and embrace long-term thinking, rather that getting caught in the negative feedback loop of solving the problems caused by the thoughtless use of technology with more technology. In many, we try to intersect his ideas with one of the most technologically-driven thinkers of the 20th century, Buckminster Fuller, who was equally preoccupied with environmental issues but approached the problem from a diametrically opposite angle.

Marcus Fairs: Are there any contemporary practices or individuals doing work that could be described as non-extractive architecture?

Joseph Grima: As I mentioned before, we like to think about this project as an attempt to build a network of people, practices, companies, thinkers, activists, philosophers, designers and also members of the public who share the belief that architecture could and should liberate itself from its dependency on depletion in various forms. We don't see this so much as a standard or a badge to attach to a finished building, like Passivhaus for example - it's more an approach to design that attempts to acknowledge and pay attention to a number of things that are often not thought about.

So examples of what we might consider "non-extractive" range from the design philosophy of well-known studios like Lacaton & Vassal, who are in the press a lot these days as the recipients of this year's Pritzker prize awarded at least in part in recognition of their policy of designing only when strictly necessary and reusing whenever possible, all the way through to the work of groups such as Who Builds Your Architecture? (WBYA?), a coalition of architects, activists, scholars, and educators that examines the links between labour, architecture and the global networks that form around the industry of building buildings.

I guess our long-term goal is to build this network as a sort of repository of complementary ideas, none of which is in itself a silver bullet, but each of which can be part of the architect's toolkit as they attempt to make architecture slightly less damaging to the world around it.

Marcus Fairs: How did this project come about?

Joseph Grima: There's an amusing story told by Tim Ingold about how in his Ten Books on Architecture, Leon Battista Alberti defines the role of the architect by specifically pointing out that an architect is not a carpenter. Apparently, the reason this distinction is necessary is that in Alberti's day, carpenters had come to be known as architects due to a mistranslation in an ecclesiastical document of the year 945, in which the translator from Latin had mistaken the verb "architecture" for a compound of "arcus" (arch) and "tectum" (roof), jumping to the conclusion that an architect must be a specialist in the construction and repair of vaulted roofs.

In many ways, Alberti's urge to define the role of the architect by exclusion, by listing a series of activities they are not responsible for, is the beginning of a long trajectory of hyper-specialisation in which the purview of the architect gradually shrinks as the complexity of the final product increases.

I've personally always been fascinated by the idea of the architect as a full-spectrum designer who actually does know at least the basic principles of how to repair a roof, or pick good lumber, but is also capable of strategic thinking around multi-century material procurement strategies integrated into the urban landscape, or non-depletionary stewardship policies for production and reuse of buildings, and at the same time is driven by curiosity and the impetus to research and continually widen their horizon of knowledge.

Both Illich and Fuller were almost maniacally convinced of the need to de-specialise to survive, and this influenced the genesis of the project a lot. Non-extractive architecture is in many ways an invitation to zoom out and zoom in at the same time, and in any case to get away from screens a little more. This is something we attempt to practice ourselves at Space Caviar, where we always hang on to a certain hands-on engagement in all of our projects.

Marcus Fairs: What will happen at the Venice exhibition?

Joseph Grima: The project will be articulated through several parallel initiatives that will simultaneously activate V–A–C's Palazzo delle Zattere on multiple levels, transforming it into a research lab in which we will work together with resident researchers who we're recruiting through open calls. These parallel strands of research, residences, public programs, publishing and broadcasting will intertwine and overlap throughout the year, alternating levels of intensity, and will all be part of an exhibition that will take form and evolve over the course of the year.

We like to think of the palazzo as an open-door design studio, in which the public can enter and witness the research process firsthand (or rather, will be able to enter once the lockdown is lifted). The year's work will culminate in the publication of Non-Extractive Architecture Vol. 2, which will be focused on collecting and documenting case studies and the network of people around the world who are already working on these ideas.

Marcus Fairs: What are the long-term objectives?

Joseph Grima: I think the long-term goals of the project are to propose an alternative model of what it means to be an architect, especially to young people getting into the profession now. Architecture and design schools tend to be locked into a certain understanding of the architect's role in society and the heroic, modernist model they hold up as an example for young designers tends to be self-perpetuating, with consequences that are not always desirable (for society in general, but also for architects themselves).

Rather than addressing design challenges from a programmatic or compositional perspective, as schools tend to train students to, we want to start from the very end of the story: how can I solve this design problem in a way that will not simply shift the problem, perhaps in a different form, somewhere else?

It sounds simple, but in fact, it's incredibly difficult because much of the prosperity we have achieved as privileged Western societies is simply a function of externalities we've created elsewhere, usually in poorer countries further south. Unpicking the supply chains our daily lives depend on and rethinking these productive activities so they weigh on our own shoulders and not the shoulders of others is going to take a very long time - we literally have to unlearn what we've been taught and in some cases start over. This project will definitely evolve and take many different forms in the coming years, and it's an incredibly exciting challenge.

Non-Extractive Architecture will run at the V–A–C's Venetian headquarters until January 2021. For an up-to-date list of architecture and design events, visit Dezeen Events Guide.

The post Non-Extractive Architecture manifesto calls for buildings that are "not intrinsically dependent on exploitation" appeared first on Dezeen.

0 notes

Text

Non-Extractive Architecture manifesto calls for buildings that are "not intrinsically dependent on exploitation"

Italian research studio Space Caviar has released a manifesto for a new type of architecture that does not deplete the earth's resources.

Called Non-Extractive Architecture, the manifesto calls on architects to design buildings that avoid exploiting the planet or people.

"Non-extractive architecture questions the assumption that building must inevitably cause some kind of irreversible damage or depletion somewhere - preferably somewhere else - and the best we can do as architects is limit the damage done," said Space Caviar co-founder Joseph Grima.

"Our goal as architects is not to limit carbon emissions," he added. "It is to come up with an idea of architecture that is not intrinsically dependent on some form of exploitation."

Top: the non-extractive architecture book. Above: Space Caviar co-founder Joseph Grima. Photo by Boudewijn Bollmann

The manifesto consists of a book and an exhibition, both titled Non-Extractive Architecture: On Designing Without Depletion.

The book was published by cultural foundation V–A–C and Steinberg Press last month while an exhibition on the same topic at V–A–C's Venetian headquarters was installed in March and will open when Covid regulations allow it to.

An exhibition was installed at V–A–C's Venetian headquarters in March. Photo by Marco Cappelletti

Running until January 2022, the exhibition will be a live research platform that will run alongside the Venice Architecture Biennale, which is due to open in May after being postponed from last year due to the pandemic.

"Both the project and the [exhibition] project are an attempt to question some of the assumptions underlying contemporary architectural production from a material and social perspective, and rethink the construction industry in the belief that better alternatives exist".

The exhibition will include the XYZ cargo publishing station by N55/Ion Sørvin and Till Wolfer. Photo by Marco Cappelletti

Taking place at V–A–C Zattere, a renovated palazzo on the Canale dell Giudecca, the project will generate research for a second book due to be published next year.

"At the most basic level, non-extractive architecture is an architecture that does not produce externalities," said Grima, who is also creative director at Design Academy Eindhoven and chief curator of design at Milan's Triennale di Milano museum as well as co-founder of Milanese design platform Alcova.

"The goal of the coming year of research and programs at V–A–C Zattere in Venice is to investigate the material, social and theoretical dimensions of this idea," Grima said.

Set to run until January 2022, the Venice show will include the XYZ cargo mobile library by N55/Ion Sørvin and Till Wolfer. Photo by Marco Cappelletti

Grima said that while ideas such as increasing energy efficiency of buildings, designing for reuse and reducing the carbon footprint of construction materials are important, "unless it is part of a larger strategy that has a clear goal there is a risk of it becoming little more than a damage-limitation exercise."

"Zero-carbon buildings aren't going to be much help, even if they're made out of carbon-capturing cross-laminated timber if their production is dependent on massive monocultural reforestation that depletes ecosystems or displaces communities and then needs to be hauled across continents by trucks that require massive infrastructural projects to make transportation cheap."

Grima added: "I think the long-term goals of the project are to propose an alternative model of what it means to be an architect, especially to young people getting into the profession now."

Based between Milan and London, Space Caviar is a research studio that explores architecture, technology, politics and the public realm. It was founded in 2013 by Grima and Tamar Shafrir.

Below is an interview with Grima about non-extractive architecture:

Marcus Fairs: What is non-extractive architecture?

Joseph Grima: At the most basic level, Non-extractive architecture is an architecture that does not produce externalities. In economics, externalities are costs that are imposed on a third party who did not agree to incur those costs. The most obvious example of an externality is pollution: if I drive from A to B by car, I pump a certain amount of NOx, CO2 and various other gases into the atmosphere. The benefit of travelling by car is mine alone, but the "cost" - in terms of the damage done - is equally shared by all of humanity, because CO2 doesn't much care about borders.

One of the key innovations of highly productive industrial economies was to become really effective at making their externalities invisible - relocating them somewhere beyond the horizon of perception of the societies or individuals benefiting from their productivity. And somewhere along the way, it somehow became accepted that there wasn't much choice: the price of modern civilisation was a certain amount of depletion and devastation, but as long as it was limited, and it happened somewhere else, the tradeoff was acceptable.

It's indisputable that technology and modernity have improved the quality of life for much of humanity, and that is true of the construction industry too. But the same construction industry is responsible for close to 40 per cent of carbon emissions, exploitative labour conditions, depletion of natural resources, and the irreversible transformation of landscapes and communities. Usually, most of this is completely invisible to those who benefit the most from it. Non-extractive architecture questions the basic assumption that this is unavoidable.

At a broader level, we believe that there can be no singular definition of Non-extractive architecture, and we realise it's an incredibly complex and nuanced question. The goal of the coming year of research and programs at V–A–C Zattere in Venice is to investigate the material, social and theoretical dimensions of this idea.

Marcus Fairs: The book comes across as a manifesto. Is that the intention?

Joseph Grima: I guess in some ways it is a manifesto. "Manifesto" is a word borrowed from Italian that literally means "billboard" or "placard", partly because manifestos have always referred to an open call to the person on the street or a broad appeal for support on a matter of vital collective importance.

We believe that the question of how we build, what we build, how we source our materials, what happens to them when a building is no longer needed, "who builds what and why" you could say, is just such a matter of vital significance. The kind of change we need, and which we advocate with Non-Extractive Architecture, is more cultural than technical.

It's an invitation to think about the long-term consequences of building, not just locally but in places usually far beyond the horizon where materials are sourced and where they'll end up. Or the consequences for individuals and communities whose labour is necessary to build in a certain way.

One of the ideas that drives this project is that in order to address the massive impact the construction industry has on the environment, the public's expectation of what architects do needs to be reframed, and this is where it's incredibly helpful and important to have the support and visibility an international foundation like V–A–C Zattere is able to offer. Specifically, it needs to be understood to stretch well beyond the currently accepted model which runs from strategic definition to handover.

So yes, I guess in a certain way this book is a manifesto, in that it attempts to bring together a wide spectrum of thought and practice, channelling the work of many others who are thinking along similar lines right now in many different fields (many of whom generously contributed to the first of the two volumes we will publish on this topic, which just came out).

As for the question of a movement, I personally prefer the idea of the network to movements - those tend to be rather dogmatic, which can lead to people feeling that they need to act as the gatekeepers of an orthodoxy. There is no orthodoxy here - our goal is not to prescribe the way things should be done.

Marcus Fairs: There are a lot of ideas circulating currently about how to lessen architecture's impact on the planet. How is non-extractive architecture different from them?

Joseph Grima: Because architecture and the construction industry are so carbon-intensive - by some measures they're estimated to account for some 40 per cent of total annual carbon emissions - there's naturally a huge amount of research going into making buildings more energy-efficient in order to cut down on emissions deriving from climate control, for example.

Others are looking into technical solutions for cutting down on emissions released by concrete as it sets. Others still are looking at "material passports" that track the full lifecycle of building components, or modular designs that allow them to be reused in other buildings once decommissioned.

All of this is incredibly important, but while each of these approaches is commendable and vital in its own way, unless it is part of a larger strategy that has a clear goal there is a risk of it becoming little more than a damage-limitation exercise. Non-extractive architecture questions the assumption that building must inevitably cause some kind of irreversible damage or depletion somewhere - preferably somewhere else - and the best we can do as architects is limit the damage done.

Zero-carbon buildings aren't going to be much help, even if they're made out of carbon-capturing cross-laminated timber, if their production is dependent on massive monocultural reforestation that depletes ecosystems or displaces communities, and then needs to be hauled across continents by trucks that require massive infrastructural projects to make transportation cheap.

Engineering for efficiency is crucial, reuse is crucial, reversibility is crucial, but unless they're all part of a strategic toolbox that operates at a much higher level - at least at an urban scale - and thinks much more ambitiously, they won't shift the needle enough.

What we're arguing is that our goal as architects is not to limit carbon emissions - it is to come up with an idea of architecture that is not intrinsically dependent on some form of exploitation (of resources, of people, of the future).

It's important to point out here that there is a broad field of contemporary discourse around the concepts of extraction and extractivity that analyse and define it at many different levels - not just material but also sociological, economic and geopolitical.

For example, one of the most extraordinary books I've read recently is Martin Arboleda's Planetary Mine: Territories of Extraction under Late Capitalism, which offers an incredible and unvarnished account of the violence of extractive practices and the ways in which mines in the Atacama Desert of Chile have become intermingled with an expanding constellation of megacities, ports, banks, and factories across East Asia and onwards towards Europe and elsewhere.

Marcus Fairs: Is the name "non-extractive architecture" and the concept new?

Joseph Grima: The idea of non-extractive architecture is absolutely not new, and it would be tempting to argue that it's always been there - there are plenty of studies into the ways in which vernacular traditions all over the world have evolved to establish a balance between the needs of a community and the equilibrium of the environment it is situated in.

In Non-Extractive Architecture: On Designing without Depletion vol. 1 there's a beautiful essay by Elsa Hoover, an amazing young Anishinaabe/Zhaaganaash architect, writer, and mapmaker who talks about architecture in terms of thousands of years of stewardship and the overlapping layers of land use, history, and governance that can be traced in the landscape around Lake Huron.

But it's important to point out that we're not advocating a return to past practices or the dimension of the vernacular. We live in a deeply technologically empowered society, and our tendency is to solve the problems we cause through bad planning and exploitative use of technology with more technology.

What we and many of the authors in this book advocate is not to step back from our identity as creatures of the post-atomic age, but to think harder and longer before resorting to technology. We might not need to adopt the specific techniques or practices of the Anishinaabe, for example, but there's a lot we could learn from their ability for long-term thinking and deep awareness of how their environment works.

Aside from that, there are many people doing amazing work that's very relevant at all sorts of levels, and which we plan to document extensively in volume 2 - from economists thinking about alternatives to GDP as a metric of prosperity, which is one of the root causes of a mindset of exploitation and waste, to companies developing 3D printers that can make buildings out of something as universally available as mud. We really see the idea of non-extractive architecture as an opportunity for exciting and ambitious new possibilities, rather than a form of renunciation.