#cassell’s illustrated history of england

Text

Richard III at the Battle of Bosworth in Cassell's History of England , Volume 2 (King's ed.)

by Edmund Blair Leighton

#edmund blair leighton#edmund leighton#richard iii#king of england#england#king#kingdom of england#cassell’s history of england#john cassell#cassell’s illustrated history of england#history of england#history#art#illustration#medieval#knights#knight#middle ages#wars of the roses#armour#king richard iii#english#europe#european#cassell and company#woodcut#battle of bosworth#bosworth#field

959 notes

·

View notes

Text

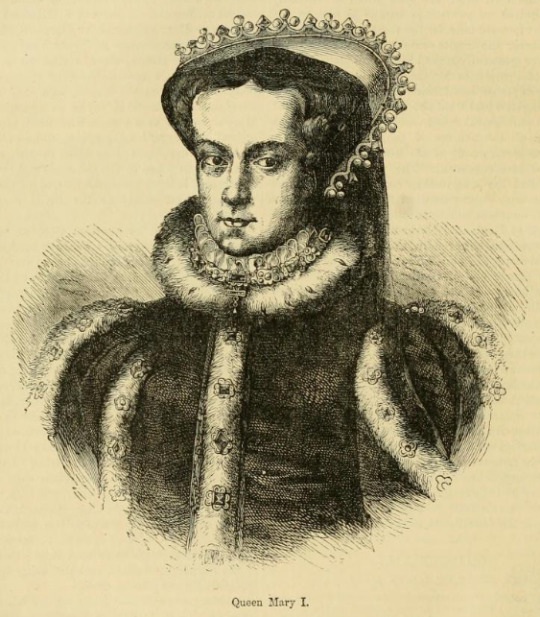

Mary I and her siblings Elizabeth I and Edward VI

"On 21 July[1536], Mary sent a letter to her father [...] she praised 'my sister, Elizabeth' as a 'child toward (forward and clever for her age)' in whom she thought Henry[VIII] would 'rejoice in time coming'" The kings pearl by Melita Thomas.

"Right dear and entirely beloved sister, We greet you well. [...] And thus we pray God to have you in his holy keeping. [...] Your loving sister, Mary the Quene" Mary in a letter to Elizabeth, 26 January 1554.

"Mary received another very sweet letter from [Edward VI] in May 1546. In it, he again apologized for not writing very often, and went on to say that he loved her just as much as if he wrote to her frequently. Although he did not wear his best clothes very often, he loved them most, so, although he rarely wrote to her, he loved her best" The kings pearl by Melita Thomas.

Edward, now twelve, rebuked Mary for hearing Mass in the chapel. [...] He demanded her obedience, she resisted, and both were reduced to tears." Mary Tudor: Princess, Bastard, Queen by Anna Whitelock.

Pictures are stills from the shows The Tudors and Becoming Elizabeth, and drawings from John Cassell's Illustrated History of England, Volume II, 1865

(For foreverinthepagesofhistory's 300 follower challenge day 1)

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mary Lightbody Gow - Interview between the Empress Matilda and Queen Maud.

Interview between the Empress Matilda and Queen Maud, illustration from Cassell's Illustrated 'History of England'.

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

On 11th* December 1748 Charles Edward Stuart was arrested in Paris after failing to leave under the terms of the treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle.

*Other source says 10th

Charlie had returned to France in 1746, he continued to be driven by his dynastic ambitions for a Stuart restoration in the years that followed he faced a series of setbacks and disappointments, the first was in 1647 when Pope Benedict XIV announced his intention to make Charles’s brother, Henry Benedict, a Cardinal – a Prince of the Catholic Church. Charles described this action as being like a dagger to his heart.

Think about the impact of this appointment: hopes of a Stuart restoration to the throne were now irrevocably dashed. Such an overt allegiance to the Catholic Church would make it difficult – if not impossible – for Charles to stake a claim. It became clear that King Louis would not finance another rising so Prince Charles, with his loyal servant, Archie Cameron, rode across the Pyrenees into Spain to try to win King Ferdinand to his cause, this again was unsuccessful.

Returning to France he was joined by his wife Jean, who had suffered badly during his absence, losing two of their children from exposure as they hid in caves and on the hills. The consolation was the king of France continued, however, to accord his visitor ‘moral support’, this was however about to change.

The dates differ slightly on this next setback, in December 1748 in accordance with the treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle, Charles was requested to leave France. Charles was told to leave forthwith for the Swiss city of Fribourg, a retreat Louis had arranged for him; but he refused to be dictated to and paraded around Paris as if he “owned the city and all of France.” He was warned that he would be arrested and bodily thrown out if necessary, but he still believed he could bluff out of existence in France.

One source tells us that things came to a head mid December when…….

“………Charles arrived by coach at the opera house. The footman who opened the doors was swiftly brushed aside by armed guards. Upon orders from his most Christian Majesty, the Prince was arrested, trussed hand and foot, and carried off to the person in Vincennes, where he was to remain until his senses were restored. On December 12th, Charles finely made his submission to the King of France by letter. After a grovelling preamble about his undying devotion to Louis’s sacred person, the Prince said he was ready to leave France as commanded. He was released with money and an escort and order to Avignon.”

An objection was raised by the English government to his stay in this city, and Charles departed of his own accord, early 1749 he was given a residence by the Pope.

For the next few years his movements are wrapped in mystery, which recent investigation has only partially unveiled. For some time he was living secretly in Paris, though not unknown to the French government, with his mistress, Clementina Walkenshaw, who had joined him soon after his return from Scotland.

It is certain that he was in London in 1750, and that at this time he declared himself a protestant, under the idea that by so doing he would greatly improve his chance of obtaining the English crown.

There is also evidence he was in London in 1752 and 1754 to rouse the English Jacobites into action, but without success.

In 1766 James VIII and III died in Rome; his son would ‘inherit’ the right to become Charles III, but this required recognition from the Pope and Europe’s Catholic monarchs, to me this was the final nail in the coffin, this recognition was not forthcoming.

By the time of Prince Charles’s death in 1788 he had been reunited with his only daughter, Charlotte and she took care of her father in his final, ailing years.

Pics are of the Prince, the drawing is “ Arrest of the Young Pretender in Paris,” illustration from 'John Cassell's Illustrated History of England', c.1858 (engraving)

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

June 21st, 1529: Catherine of Aragon’s Speech at Blackfriars as Depicted in Art:

Trial of Catherine of Aragon by Frank O. Salisbury (1906)

Katherine of Aragon Denounced Before King Henry VIII and His Council By Laslett John Potts (1837)

Trial of Queen Katherine from John Cassell’s Illustrated History of England Volume 2 (1858)

Wood Carving of the Trial of Catherine of Aragon

The Trial of Catherine of Aragon by George Henry Harlow (1817)

Henry VIII and Catherine of Aragon before Papal Legates at Blackfriars by Frank O. Salisbury

Trial of Queen Catherine of Aragon by Henry Nelson O’Neil (1846/8)

Catherine Of Aragon Kneeling Before Her Husband King Henry VIII Of England At The Trial Of Their Marriage From The National And Domestic History Of England By William Aubrey (1890)

#catherine of aragon#katherine of aragon#katharine of aragon#catalina de aragon#the tudors#henry viii#tudor history#english history#tudor era#art#victorian period#victorian painting#victorian art#tudor dynasty#the tudor period#the tudor era#the tudor dynasty#tudor#house of tudor#on this day in history#the six wives of henry viii#king henry viii#henry tudor#shakespeare’s henry viii#william shakespeare#shakespeare#cardinal wolsey#thomas wolsey#history#engraving

49 notes

·

View notes

Text

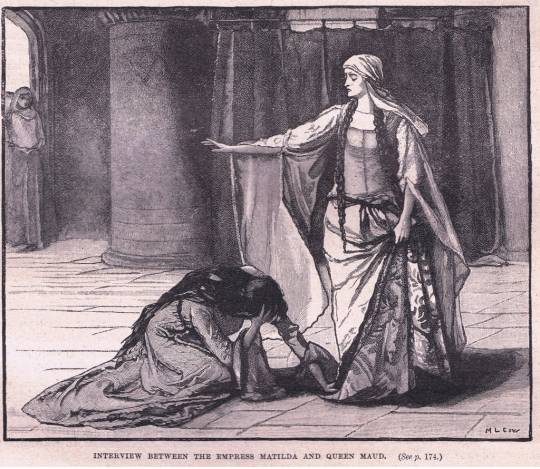

The Mutiny at Spithead: Hauling down the Red Flag on the "Royal George". Illustration from Cassell's History of England (special edition, AW Cowan, c 1890)

The Spithead and Nore mutinies of 1797 were not actually mutinies but rather a strike that lasted four weeks. The main issues to be negotiated with the Admiralty were better pay, the abolition of a levy on the purser ("purser's pound") and the replacement of some unpopular officers. Neither flogging nor pressing was brought up. The mutineers maintained their daily navy routine and discipline on their ships (mostly with their regular officers) and also allowed some ships to leave the Spithead to go on patrol, for example.

As a result of these negotiations, the worst abuses in the Royal Navy, such as bad food, brutally enforced discipline and withholding of pay, were alleviated or abolished. And an increase in pay was introduced.

66 notes

·

View notes

Photo

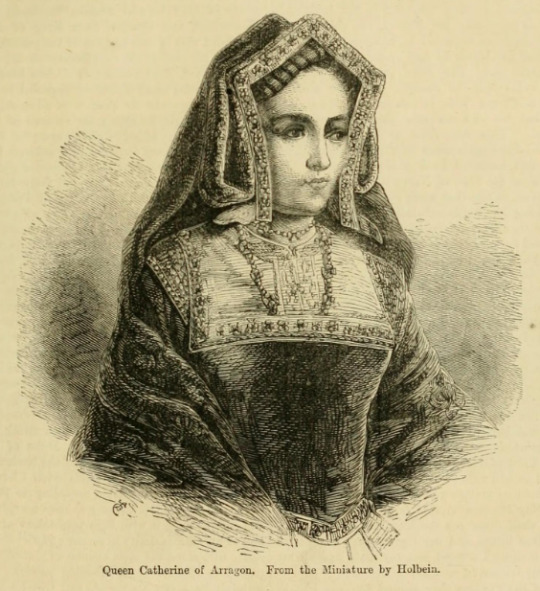

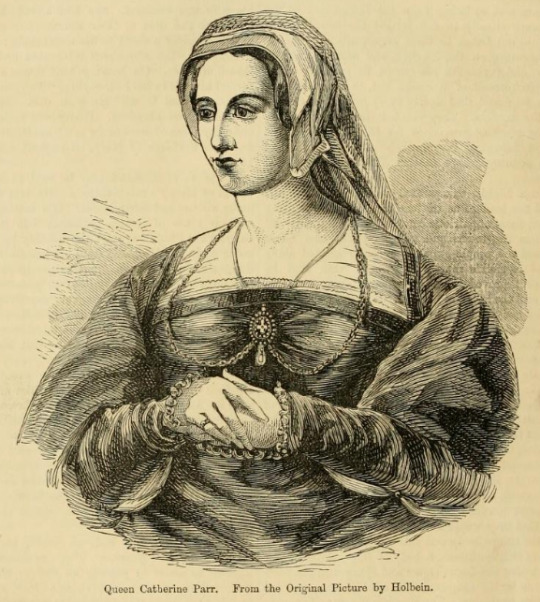

The Six Wives of Henry VIII, depicted in John Cassell's Illustrated History of England, Volume II, 1865

Catherine of Aragon 1509 - 1533

Anne Boleyn 1533 - 1536

Jane Seymour 1536 - 1537

Anne of Cleves 1540 - 1540

Catherine Howard 1540 - 1542

Catherine Parr 1543 - 1547

#catherine of aragon#anne boleyn#jane seymour#anne of cleves#catherine howard#catherine parr#they really did catherine howard dirty she looks the oldest!

245 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Building Of The Tower Of Babel. Cassell's Illustrated History of England vol 1 • via Bibliothèque Infernale on FB

48 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Druids inciting the Britons to oppose the landing of the Romans. Illustration from The People’s History of England (Cassell Petter & Galpin, c 1890).

140 notes

·

View notes

Text

a well known Engine us’d both on Land and at Sea

to land. At sea, even then 1858

Lay the Land, to lay the land, at sea,

signifies to sail out of sight of land. 1707

they appear as bluffs of land at sea 1815

distant sails or the first loom of the land.

At sea there is nothing to be seen close by 1896

Sea, see Say. 1904

the resemblance of an head land at sea. 1799

confined to the Land; at Sea, tho’ at ever so small a Distance, the Air is always free from the noxious Vapours, which alone occasion that Sickliness and Mortality. 1765

Tis well you are by land, at sea 1673

some — not all — of the pre-aeronautical instances of to land at sea (and those, mostly, proximity hits) encountered via the usual means. to land at sea, my method in nuce. sources —

1858

John Cassell's illustrated history of England *

1707

Thomas Blount (1618-1679 *). Glossographia Anglicana Nova: Or, A Dictionary, Interpreting Such Hard Words of Whatever Language, as are at present used in the English Tongue, with their etymologies, definitions, &c. *

1815

ex William Wordsworth, “To the Daisy” in Epitaphs and Elegiac Poems. *

1896

Sarah Orne Jewett (1849-1909 *). The Country of the Pointed Firs. *

1904

Joseph Wright (1855-1930 *), ed., English Dialect Dictionary (vol. 5 R–S) *

a say being 1. A bucket; a vessel having two ears, a milk-pail; a tub.

1799

Edward King (1735?-1807 *). Munimenta antiqua: or, Observations on antient castles, vol. 1. *

1765

Thomas Whately (1726-72 *). The regulations lately made concerning the colonies and the taxes imposed upon them considered. *

1673

John Dryden (1631-1700), "Amboyna, or the Cruelties of the Dutch to the English Merchants" (III.2), in Works (1808) *

on the play (1673), and on the Amboyna Massacre (1623)

epigram —

definition of Pump,

ex Edward Phillips (1630-96 *). The New World of English Words (third edn, 1720) *

—

all tagged at sea

all tagged engines

all tagged method

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

“ La Fayette Preserving the Life of the Queen”, Cassell’s Illustrated History of England (1878)

Not sure why it’s in a history of England (I’ve read it, and advise avoiding this text if you have any interest in the French Revolution), but it references Lafayette protecting/advising the royal family on 6 October 1789 during the Women’s March on Versailles

#marie-antoinette#Gilbert du Motier Marquis de Lafayette#marquis de lafayette#French Revolution#general lafayette#lafayette#interesting source#is he preserving her life from a spider on the ceiling?#I mean#if i didn't know the context...#women's march on versailles

85 notes

·

View notes

Text

John Cassell's Illustrated History of England

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Queen Opening the Royal Palace of Justice, 1882, photographed in Cassell's History of England Vol. VII

I am now part of The Cultural Negotiation of Science research group! Which is quite wonderful and terrifying. “CNoS brings together artists, academics and research students whose practices engage with expert cultures across a broad spectrum of science and technology. Based at Northumbria University, Newcastle, CNoS seeks to reach across publics and research communities to develop a performative approach to the production of knowledge that actively challenges the use of art as an instrumental or illustrative device to interpret science.”

Here is the short bio I wrote for the website, to introduce my project:

Grace Denton is an artist born in West Yorkshire, now based in Newcastle upon Tyne. She began her PhD studentship at Northumbria University in January 2021, under the guidance of Christine Borland and Clark Lawlor. The proposed title of her project is The nominally sovereign body: A practice-based exploration of the language of self-governance through the prism of AD/HD

This body of work is concerned with the notion of sovereignty, self-governance, and the slippery language of individualism. This is played out against her experience of AD/HD, and the lack of self-actualisation the disability can lead to. She will explore (1) the semantic and political history of the sovereign in the popular imagination, and (2) the point at which we put language to experience, and engage in collective mythmaking around health, wellbeing, and political influence. Crucially, she will work with the Institute of Medical Humanities, Durham, who explore ‘how symptoms come into being and are given meaning in the everyday world’.

Denton’s practice employs autofiction, performance, sculpture and video. Previous exhibitions include: Unintimacy co-presented with Caitlin Merrett-King at The NewBridge Project : Newcastle, Something Good at Outpost Norwich and union jack emoji performed as part of Kathryn Elkin’s Seminar Day at BALTIC 39.

For further information see: http://www.gracedenton.co.uk/

Contact: [email protected]

0 notes

Photo

The First Christmas Tree

Alison Barnes sets the record straight on who was really responsible for introducing this popular custom to Britain.

Alison Barnes | Published in History Today Volume 56 Issue 12 December 2006

A Christmas tree for German soldiers in a temporary hospital in 1871Prince Albert, Queen Victoria’s consort, is usually credited with having introduced the Christmas tree into England in 1840. However, the honour of establishing this tradition in the United Kingdom rightfully belongs to ‘good Queen Charlotte’, the German wife of George III, who set up the first known English tree at Queen’s Lodge, Windsor, in December, 1800.

Legend has it that Queen Charlotte’s compatriot, Martin Luther, the religious reformer, invented the Christmas tree. One winter’s night in 1536, so the story goes, Luther was walking through a pine forest near his home in Wittenberg when he suddenly looked up and saw thousands of stars glinting jewel-like among the branches of the trees. This wondrous sight inspired him to set up a candle-lit fir tree in his house that Christmas to remind his children of the starry heavens from whence their Saviour came.

Certainly by 1605 decorated Christmas trees had made their appearance in Southern Germany. For in that year an anonymous writer recorded how at Yuletide the inhabitants of Strasburg ‘set up fir trees in the parlours ... and hang thereon roses cut out of many-coloured paper, apples, wafers, gold-foil, sweets, etc.’

In other parts of Germany box trees or yews were brought indoors at Christmas instead of firs. And in the duchy of Mecklenburg-Strelitz, where Queen Charlotte grew up, it was the custom to deck out a single yew branch.

The poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge (1772-1834) visited Mecklenburg-Strelitz in December, 1798, and was much struck by the yew-branch ceremony that he witnessed there, the following account of which he wrote in a letter to his wife dated April 23rd, 1799: ‘On the evening before Christmas Day, one of the parlours is lighted up by the children, into which the parents must not go; a great yew bough is fastened on the table at a little distance from the wall, a multitude of little tapers are fixed in the bough ... and coloured paper etc. hangs and flutters from the twigs. Under this bough the children lay out the presents they mean for their parents, still concealing in their pockets what they intend for each other. Then the parents are introduced, and each presents his little gift; they then bring out the remainder one by one from their pockets, and present them with kisses and embraces’.

When young Charlotte left Mecklenburg-Strelitz in 1761, and came over to England to marry King George, she brought with her many of the customs that she had practised as a child, including the setting up of a yew branch in the house at Christmas. But at the English Court the Queen transformed the essentially private yew-branch ritual of her homeland into a more public celebration that could be enjoyed by her family, their friends and all the members of the Royal Household.

Queen Charlotte placed her yew bough not in some poky little parlour, but in one of the largest rooms at Kew Palace or Windsor Castle. Assisted by her ladies-in-waiting, she herself dressed the bough. And when all the wax tapers had been lit, the whole Court gathered round and sang carols. The festivity ended with a distribution of gifts from the branch, which included such items as clothes, jewels, plate, toys and sweets.

These royal yew boughs caused quite a stir among the nobility, who had never seen anything like them before. But it was nothing to the sensation created in 1800, when the first real English Christmas tree appeared at court.

That year Queen Charlotte planned to hold a large Christmas party for the children of all the principal families in Windsor. And casting about in her mind for a special treat to give the youngsters, she suddenly decided that instead of the customary yew bough, she would pot up an entire yew tree, cover it with baubles and fruit, load it with presents and stand it in the middle of the drawing-room floor at Queen’s Lodge. Such a tree, she considered, would make an enchanting spectacle for the little ones to gaze upon. It certainly did. When the children arrived at the house on the evening of Christmas Day and beheld that magical tree, all aglitter with tinsel and glass, they believed themselves transported straight to fairyland and their happiness knew no bounds.

Dr John Watkins, one of Queen Charlotte’s biographers, who attended the party, provides us with a vivid description of this captivating tree ‘from the branches of which hung bunches of sweetmeats, almonds and raisins in papers, fruits and toys, most tastefully arranged; the whole illuminated by small wax candles’. He adds that ‘after the company had walked round and admired the tree, each child obtained a portion of the sweets it bore, together with a toy, and then all returned home quite delighted’.

Christmas trees now became all the rage in English upper-class circles, where they formed the focal point at countless children’s gatherings. As in Germany, any handy evergreen tree might be uprooted for the purpose; yews, box trees, pines or firs. But they were invariably candle-lit, adorned with trinkets and surrounded by piles of presents. Trees placed on table tops usually also had either a Noah’s Ark or a model farm and numerous gaily-painted wooden animals set out among the presents beneath the branches to add extra allurement to the scene. From family archives we learn, for example, that in December 1802, George, 2nd Lord Kenyon, was buying ‘candles for the tree’ that he placed in his drawing room at No. 35 Lincoln’s Inn Fields, London. That in 1804 Frederick, fifth Earl of Bristol, had ‘a Christmas tree’ for his children at Ickworth Lodge, Suffolk. And that in 1807 William Cavendish-Bentinck, Duke of Portland, the then prime minister, set up a Christmas tree at Welbeck Abbey, Nottinghamshire, ‘for a juvenile party’.

By the time Queen Charlotte died in 1818, the Christmas-tree tradition was firmly established in society, and it continued to flourish throughout the 1820s and 30s. The fullest description of these early English Yuletide trees is to be found in the diary of Charles Greville, the witty, cultured Clerk of the Privy Council, who in 1829 spent his Christmas holidays at Panshanger, Hertfordshire, home to Peter, 5th Earl Cowper, and his wife Lady Emily.

Greville’s fellow house guests were Princess Dorothea von Lieven, wife of the German Ambassador, Lord John Russell, Frederick Lamb, M. de la Rochefoucauld and M. de Montrond, all of whom were brilliant conversationalists. Greville makes no mention of any of the bons mots that he must have heard at every meal, however, or of the indoor games and the riding, skating and shooting that always took place at Panshanger at Christmas. No. The only things that really seem to have impressed him were the exquisite little spruce firs that Princess Lieven set up on Christmas Day to amuse the Cowpers’ youngest children William, Charles and Frances. ‘Three trees in great pots’, he tells us, ‘were put upon a long table covered with pink linen; each tree was illuminated with three circular tiers of coloured wax candles – blue, green, red and white. Before each tree was displayed a quantity of toys, gloves, pocket handkerchiefs, workboxes, books and various other articles – presents made to the owner of the tree. It was very pretty’.

When in December, 1840, Prince Albert imported several spruce firs from his native Coburg, they were no novelty to the aristocracy, therefore. But it was not until periodicals such as the Illustrated London News, Cassell’s Magazine and The Graphic began to depict and minutely to describe the royal Christmas trees every year from 1845 until the late 1850s, that the custom of setting up such trees in their own homes caught on with the masses in England.

By 1860, however, there was scarcely a well-off family in the land that did not sport a Christmas tree in parlour or hall. And all the December parties held for pauper children at this date featured gift-laden Christmas trees as their main attraction. The spruce fir was now generally accepted as the festive tree par excellence, but the branches of these firs were no longer cut into artificial tiers or layers as in Germany, but were allowed to remain intact, with candles and ornaments arranged randomly over them, as at the present day.

Whatever their type or mode of decoration, Christmas trees have always delighted both children and adults alike. But perhaps no tree ever gave greater pleasure than that first magnificent Yuletide tree set up so thoughtfully by Queen Charlotte for the enjoyment of the infants of Windsor.

https://www.historytoday.com/archive/history-matters/first-christmas-tree

1 note

·

View note

Text

British Library digitised image from page 341 of "Old and New Paris. Its history, its people, and its places ... With numerous illustrations"

Image taken from:

Title: "Old and New Paris. Its history, its people, and its places ... With numerous illustrations"

Author(s): Edwards, H. Sutherland (Henry Sutherland), 1828-1906 [person]

British Library shelfmark: "Digital Store 10172.h.3"

Page: 341 (scanned page number - not necessarily the actual page number in the publication)

Place of publication: London (England)

Date of publication: 1894

Publisher: Cassell

Type of resource: Monograph

Language(s): English

Physical description: 2 volumes (8°)

Explore this item in the British Library’s catalogue:

001041515 (physical copy) and 014809790 (digitised copy)

(numbers are British Library identifiers)

Other links related to this image:

- View this image as a scanned publication on the British Library’s online viewer (you can download the image, selected pages or the whole book)

- Order a higher quality scanned version of this image from the British Library

Other links related to this publication:

- View all the illustrations found in this publication

- View all the illustrations in publications from the same year (1894)

- Download the Optical Character Recognised (OCR) derived text for this publication as JavaScript Object Notation (JSON)

- Explore and experiment with the British Library’s digital collections

The British Library community is able to flourish online thanks to freely available resources such as this.

You can help support our mission to continue making our collection accessible to everyone, for research, inspiration and enjoyment, by donating on the British Library supporter webpage here.

Thank you for supporting the British Library.

from BLPromptBot https://ift.tt/3c8QrJQ

0 notes

Photo

Image from 'John Cassell's Illustrated History of England. The text, to the Reign of Edward I., by J. F. Smith; and from that period by W. Howitt', 003420056

Author: Smith, J. F. (John Frederick)

Volume: 03

Page: 359

Year: 1856

Place: London

Publisher:

View this image on Flickr

View all the images from this book

Following the link above will take you to the British Library's integrated catalogue. You will be able to download a PDF of the book this image is taken from, as well as view the pages up close with the 'itemViewer'. Click on the 'related items' to search for the electronic version of this work.

#bldigital#bl_labs#britishlibrary#1856#similar_to_171917785342_bubblyness_avesize#similar_to_171917785342_bubblyness_x#similar_to_171917785342_bubblyness_y#sideways_upperbody_detected_481left_-421top_563right_-521bottom

1 note

·

View note